1. Introduction

Shigella spp. are foodborne and waterborne pathogens [

1,

2] that have been isolated from different foods [

3] such as vegetables, chicken, produce and dairy products [

4,

5]. Developing countries have a high incidence of Shigellosis [

6] that specially affect children under five years of age [

7]. Specifically,

Shigella flexneri is the most prevalent pathogen responsible for Shigellosis in Argentina [

8]. These bacteria are accountable for food poisoning outbreaks worldwide [

9] and are an important cause of infant mortality in our country [

10].

Treatment of foods with additives such as organic acids is an effective approach to reduce populations of pathogens [

11]. However,

Shigella can survive for significant periods of time under conditions such as high concentration of organic acid [

12,

13]. Also, biocides like hypochlorite and ethanol are commonly used in the food industry to decontaminate and sanitize food related surfaces such as equipment and tools. Bacteriophages are biocontrol tools that may be used as an economic and more natural technology to improve food safety. Unlike additives, phages are very specific agents that attack only the targeted bacteria without affecting organoleptic properties of foods. Therefore, a technological characterization of phages active against

Shigella flexneri in different food environments to fight foodborne pathogens may allow us to select phages for more effective biocontrol treatments.

In our previous studies, ten phages lytic against

S.

flexneri strains were isolated and characterized by their host range, challenge assays, adsorption assays, and stability tests under various stress conditions [

14,

15]. Thus, the aim of the present work was to evaluate the influence of additives present in food and biocides present in food-related environments on phage viability. Although studies of

Shigella phages have been conducted in several foods [

16,

17,

18], those focused on evaluate the viability of

S.

flexneri phages challenged against daily used additives and biocides have not been documented.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Phages

The

Shigella flexneri strain ATCC12022 (serotype 2b) was used to propagate (phage stocks, Tris-magnesium gelatin, TMG, 4°C) and to enumerate (plaque forming unit per milliliter; PFU mL

-1) phages in viability studies. Bacterial stocks (Triptein soy broth, TSB, 15% v/v glycerol, -80°C) were reactivated (TSB, 37°C) overnight for viability assays with phages. Ten (10) phages (AShi, Shi3, Shi22, Shi30, Shi33, Shi34, Shi40, Shi88, Shi93, Shi113) previously isolated from 114 stool samples [

14], were used to evaluate their viability against several concentrations of various biocides and preservatives.

2.2. Phage Viability Against Food Additives

The viability of ten

Shigella phages was evaluated against food grade preservatives. Phage suspensions (TMG buffer with 10

5 - 10

6 PFU mL

-1) were challenged against weak organic acids and their salts. Assays were conducted at 25 °C with a final volume of 1 mL. Treatments (preservative concentration; time of incubation): Acetic acid: 2% and 4%; 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 60 min and 24 h. Lactic and citric acids: 2% and 4%; 5 min, 15 min, 30 min and 60 min. Acetate (sodium), lactate (sodium) and citrate (sodium): 2% and 4%; 60 min, 120 min and 24 h. Benzoate (sodium): 0.1%; 60 min, 120 min and 24 h. Sorbate (potassium): 0.3%; 60 min, 120 min and 24 h. Propionate (sodium): 0.32%; 60 min, 120 min and 24 h. The concentrations used are the maximum allowed (or lower) for each preservative in foods (Argentinian food code). After incubation with each preservative, phages were enumerated by the double-layer plate titration method [

19]. Results were expressed as PFU mL

-1. Controls were performed in sterile distilled water without preservatives.

2.3. Phage Viability Against Food Additives in Food

To evaluate the phage viability of food preservatives in a food matrix, pieces (1 cm

2; pH 5.7) of beef were cut aseptically, placed in petri dishes and pre-equilibrated to 25°C. Next, 20 μL of each phage (~10

5–10

6 PFU mL

-1) and 20 μL of each organic acid (4%) (acetic, lactic and citric) were pipetted onto the surface of the meat sample and allowed to dry (10 min at 25°C) after the addition of each volume. To set the 100% of phage viability, samples with phages were also inoculated with 20 μL of TMG buffer instead of the organic acids. Controls and treatments were incubated at 25°C. After each incubation time (30 min, 60 min), meat pieces were transferred to a sterile bag, 1 mL of TMG buffer was added and samples processed for 2 min in a Stomacher (Seward, London, UK). Then, all the stomacher fluid (1 mL) was transferred to a sterile eppendorf tube, centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 min), and 0.1 mL of the supernatant was plated for phage enumeration as previously described [

19].

2.4. Phage Viability Against Biocides

Studies of phage viability against several concentrations of different biocides were also conducted. Phage suspensions in TMG buffer containing ~10

5–10

6 PFU mL

-1 were incubated with biocide solutions. All the biocides were diluted using sterile distilled water. Assays were conducted at 25 °C with a final volume of 1 mL. Treatments (biocide concentration; time of incubation): sodium hypochlorite (50 ppm, 100 ppm and 500 ppm; 1 min and 10 min). Ethanol: (10%, 70% and 96%; 15 min, 30 min, 60 min and 24 h). Quaternary ammonium chloride (QAC): (2%, 3% and 4%; 15 min, 30 min, 60 min and 24 h). Hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2): (2%, 3% and 4%; 15 min, 30 min and 60 min). After each incubation time, phages were enumerated [

19]. Plaques (Triptein soy agar, TSA, 1.5%) were incubated for 18 h at 37°C and the PFU were counted to evaluate the viability of each phage. Phage incubated in sterile distilled water without biocides was used as controls.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The mean values of two samples (treatment and control) were compared using the student's t test at p < 0.05 with n = 3 observations (three independent experiments) in each group.

3. Results

3.1. Phage Viability Against Food Additives

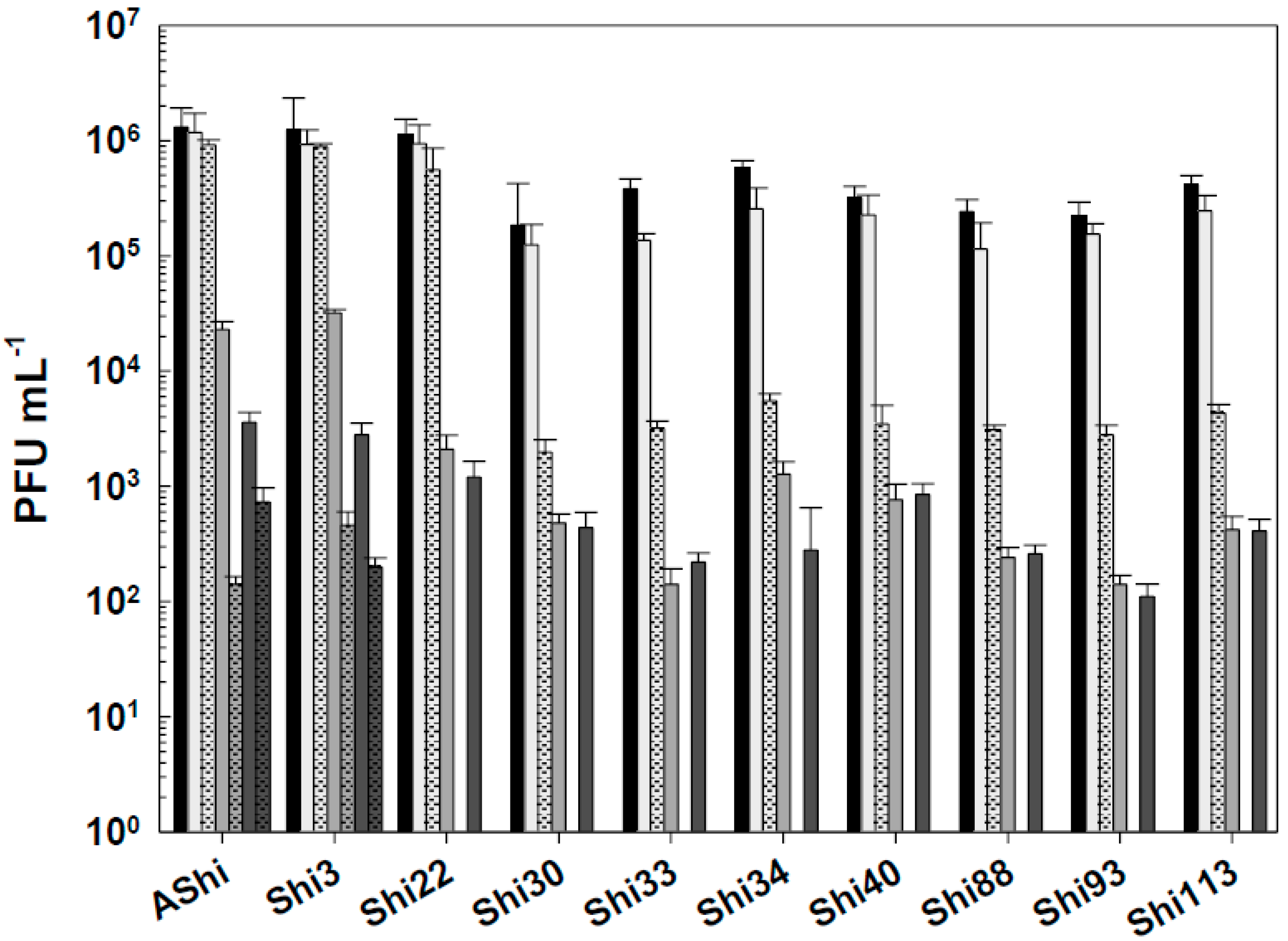

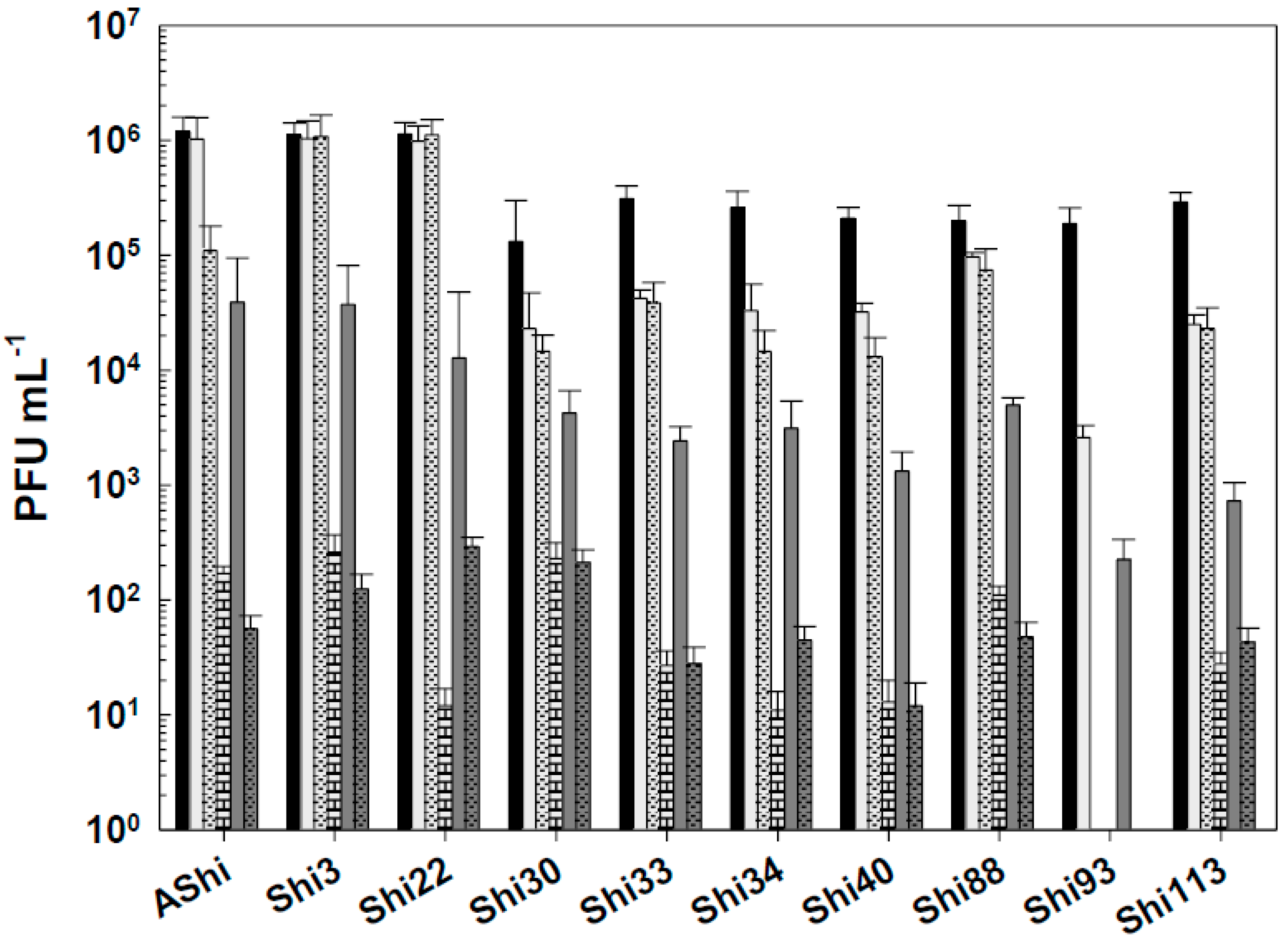

The effect of acetic acid in phage viability is shown in

Figure 1. Three phages, AShi, Shi3 and Shi22, showed a high resistance to this preservative since their viabilities resulted slightly affected only at the higher concentration (4%) tested after long incubation (30 and 60 min) times. AShi was the only phage that was detected (70 PFU mL

-1) after 24 h of incubation at the lower concentration (2%) assayed (data not shown). Regarding the other seven phages, Shi30, Shi33, Shi34, Shi40, Shi88, Shi93 and Shi113, a significant decrease in PFU mL

-1 was observed at low concentration (2%) of acetic acid after 30 and 60 min of incubation, although a significant number of phages particles (10

2 - 10

3 PFU mL

-1) remained viable. In addition, at high concentration of acetic acid (4%), phages (10

3 - 10

4 PFU mL

-1) endured up to 15 min of incubation and a complete inactivation occurred after longer incubation times. No viability was detected when these seven phages were evaluated after a 24 h-incubation period.

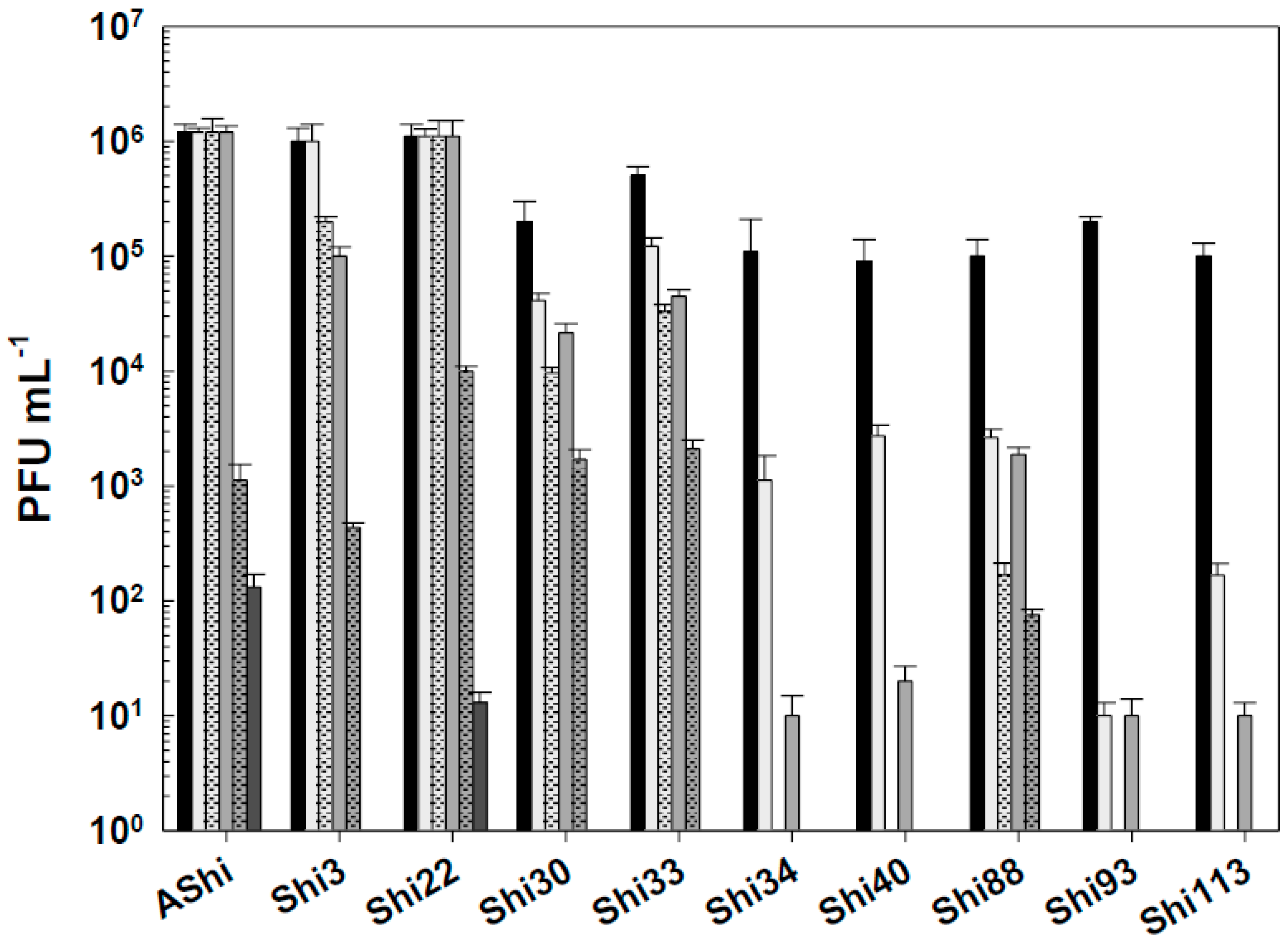

Figure 2 shows the viability of phages evaluated against two concentrations (2 and 4%) of lactic acid. AShi and Shi3 proved to be the more resistant phages to this particular weak organic acid. Although a significant decrease was observed for these two phages at 2% of lactic acid, 10

2 (PFU mL

-1; Shi3) and 10

4 (PFU mL

-1; AShi) particles were detected at the end of the experiments (60 min). Moreover, at high concentration of lactic acid (4%), the complete inactivation was produced only after 30 min of incubation. The remaining eight phages (Shi22, Shi30, Shi33, Shi34, Shi40, Shi88, Shi93, Shi113) were found to be significantly more sensitive than AShi and Shi3. Namely, phage particles of Shi33, Shi88 and Shi93 were detected after a 5-min incubation, then a complete inactivation was observed at both concentrations assayed, whereas for phages Shi22, Shi30, Shi34, Shi40 and Shi113, particles could be detected after a longer incubation time (15 min) only at the low concentration (2%) evaluated.

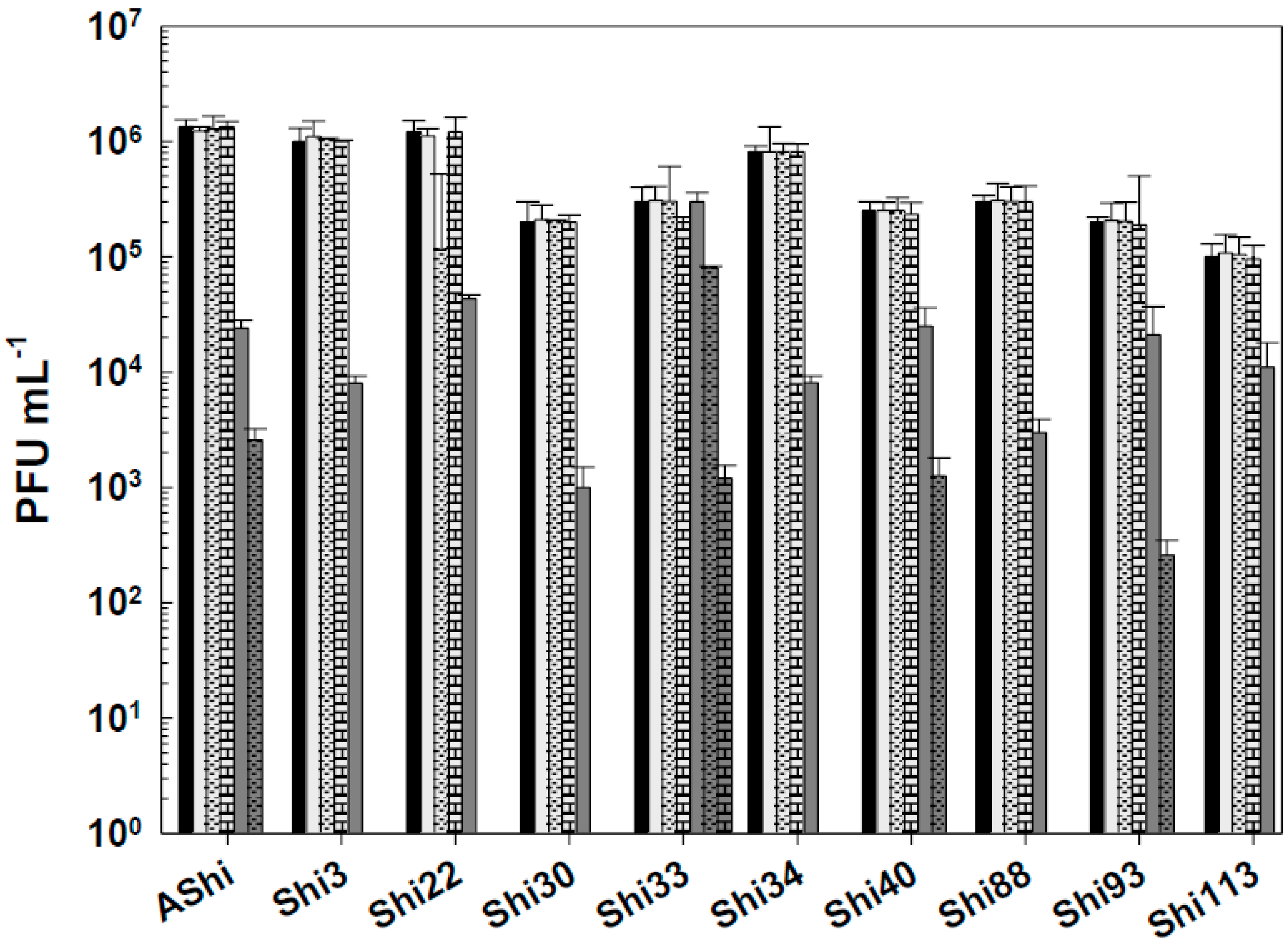

Regarding viability against citric acid, all the phages evaluated showed a moderate resistance at 2% of this preservative since 10

2 PFU mL

-1 or more particles remained viable up to 30 min of incubation (

Figure 3). At 4%, a significant number of particles were detected after 30 min (AShi and Shi3), 15 min (Shi22) and 5 min (Shi30, Shi33, Shi34, Shi40, Shi88, Shi93, Shi113) of incubation. However, longer incubation times resulted in a complete inactivation of all the phages tested.

The most effective acid to inactivate phages was the lactic followed in effectiveness by the citric. The acetic acid was the most phage-friendly treatment evaluated. Furthermore, preservatives such as acetate (sodium), lactate (sodium), citrate (sodium), benzoate (sodium), sorbate (potassium) and propionate (sodium) were also evaluated and no significant differences were observed in the viability of the ten phages tested regarding to the control conditions (data not shown).

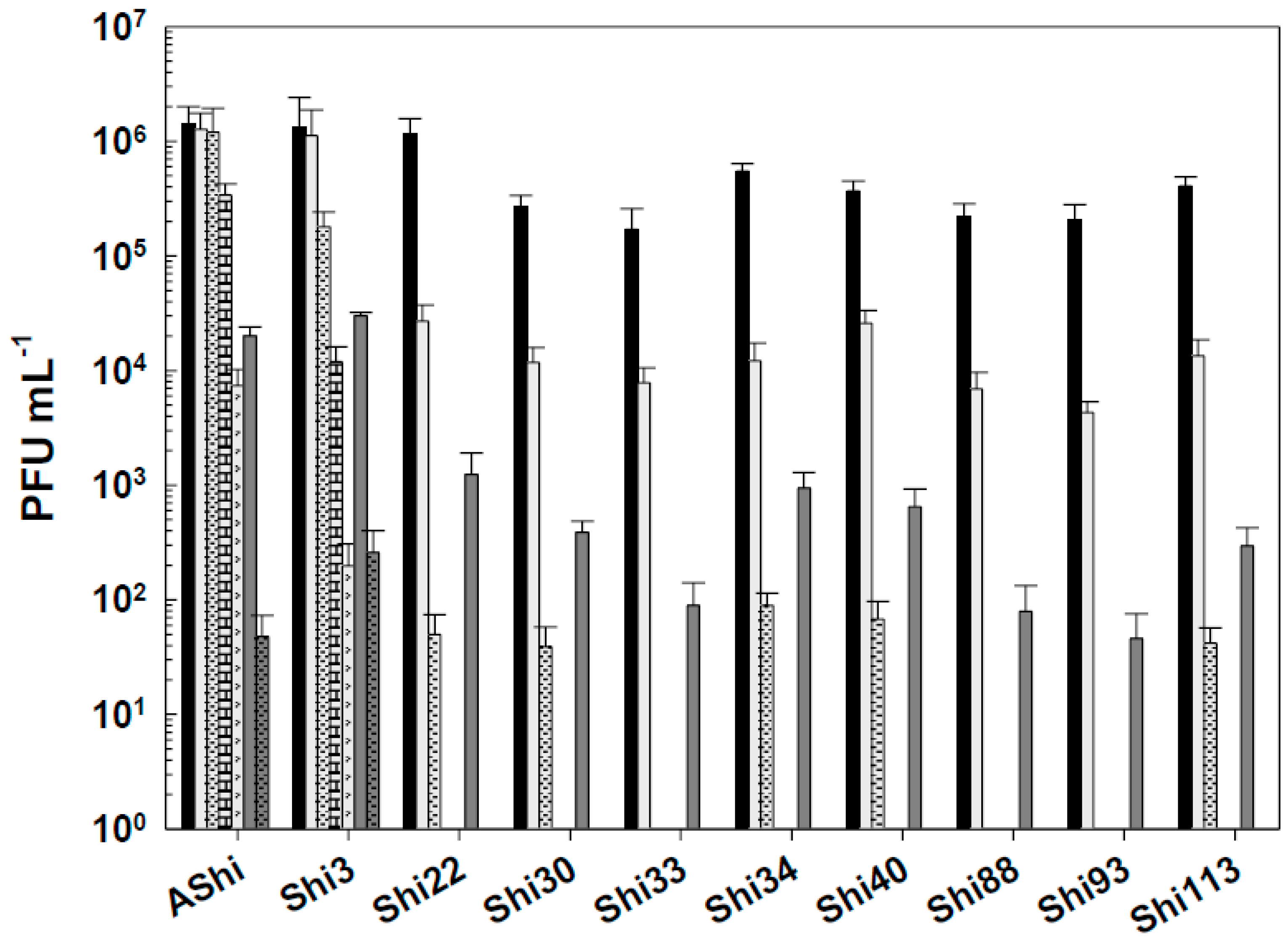

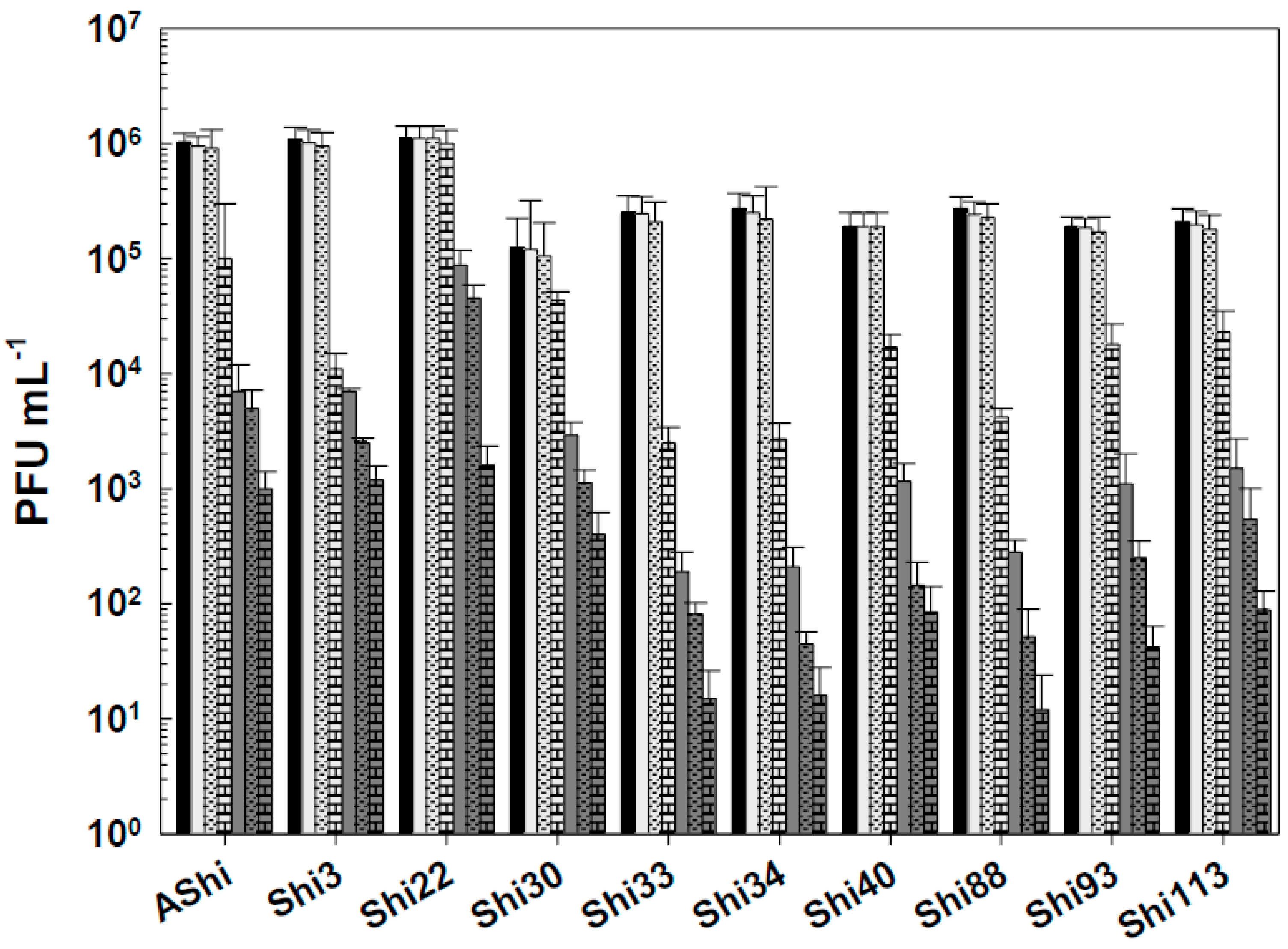

3.2. Phage Viability Against Food Additives in Food

When phages were challenged against acetic acid in a food matrix such as meat, AShi, Shi3 and Shi22 were not affected since their viabilities were not significantly reduced at both incubation times evaluated. A similar behavior was observed for the remaining phages only after 30 min of incubation, where phage count remained in the same order of magnitude of the controls. On the other hand, when the viability of these phages (Shi30, Shi33, Shi34, Shi40, Shi88, Shi93 and Shi113) was assessed after 60 min, a significant reduction (2 log10 CFU mL-1) was observed for all of them, however, a significant amount of particles (103 - 104 PFU mL-1) could still be detected.

Lactic acid produced a significant reduction in phage viabilities after 30 min of incubation, although half of the particles (103 - 104 PFU mL-1) remained viable for each phage evaluated. After a 60-min incubation, only AShi and Shi3 could be detected (102 - 103 PFU mL-1) since the other eight phages were completely inactivated.

Likewise, citric acid had a similar effect on phage viability than lactic acid. Namely, AShi and Shi3 were the most resistant phages to both organic acids. Treatments with citric acid at 4 % resulted in the detection of ~ 10

3 PFU mL

-1 (30 min) and ~ 10

2 PFU mL

-1 (60 min) of these two phages. Regarding the other viruses (Shi22, Shi30, Shi33, Shi34, Shi40, Shi88, Shi93 and Shi113), ~ 10

2 PFU mL

-1 particles survived only after a 30-min incubation period, while after 60 min all of them were completely inactivated. In addition, when the viability was compared between the treatments with the different organic acids evaluated, results indicated that phages were highly resistant to acetic acid (pKa = 4.7) and equally resistant to lactic (pKa = 3.8) and citric (pKa = 3.1) acids. Only AShi and Shi3 showed a differential resistance to lactic and citric acid (

Figure 4).

3.3. Phage Viability Against Biocides

Figure 5 shows the viability of

Shigella-phages against several concentrations of sodium hypochlorite. Six (AShi, Shi3, Shi22, Shi30, Shi33 and Shi88) out of the ten phages tested showed a high resistance to this biocide since they endured at concentrations up to 100 ppm for 10 min. Furthermore, particles of AShi (10

2 PFU mL

-1) and Shi22 (10

1 PFU mL

-1) were detected at the highest concentration of hypochlorite assayed after 1 min of incubation. On the other hand, Shi34, Shi40, Shi93 and Shi113 were the most sensitive ones to this biocide. Their viabilities were significantly affected after the shorter period of incubation (1 min) at the lowest concentration (50 ppm) assessed, and almost completely inactivated (10

1 PFU mL

-1) after 1 min at 100 ppm.

Next, phage viability against ethanol was evaluated (

Figure 6). At 10 % of ethanol, phages proved to be highly resistant since no significant reduction in PFU mL

-1 counts was observed. At a higher concentration of ethanol (70%), the most resistant phages were AShi, Shi40, Shi93 and Shi33. Namely, AShi, Shi40 and Shi93 particles were detected after 30 min, however, after 60 min of incubation these phages were completely inactivated. On the contrary, phage Shi33 showed the highest resistance against this particular biocide since a great number of particles (10

3 PFU mL

-1) remained viable up to 60 min. The rest of the phages tested (Shi3, Shi22, Shi30, Shi34, Shi88 and Shi113) showed a high sensitivity to this biocide and only 10

3 PFU mL

-1 particles were detected after 15 min. At longer incubation times all of them resulted completely inactivated. Furthermore, at the highest concentration of ethanol (96%) the ten phages were completely inactivated within 15 min, as also was observed after 24 h of incubation at 10 and 70% of ethanol (data not shown).

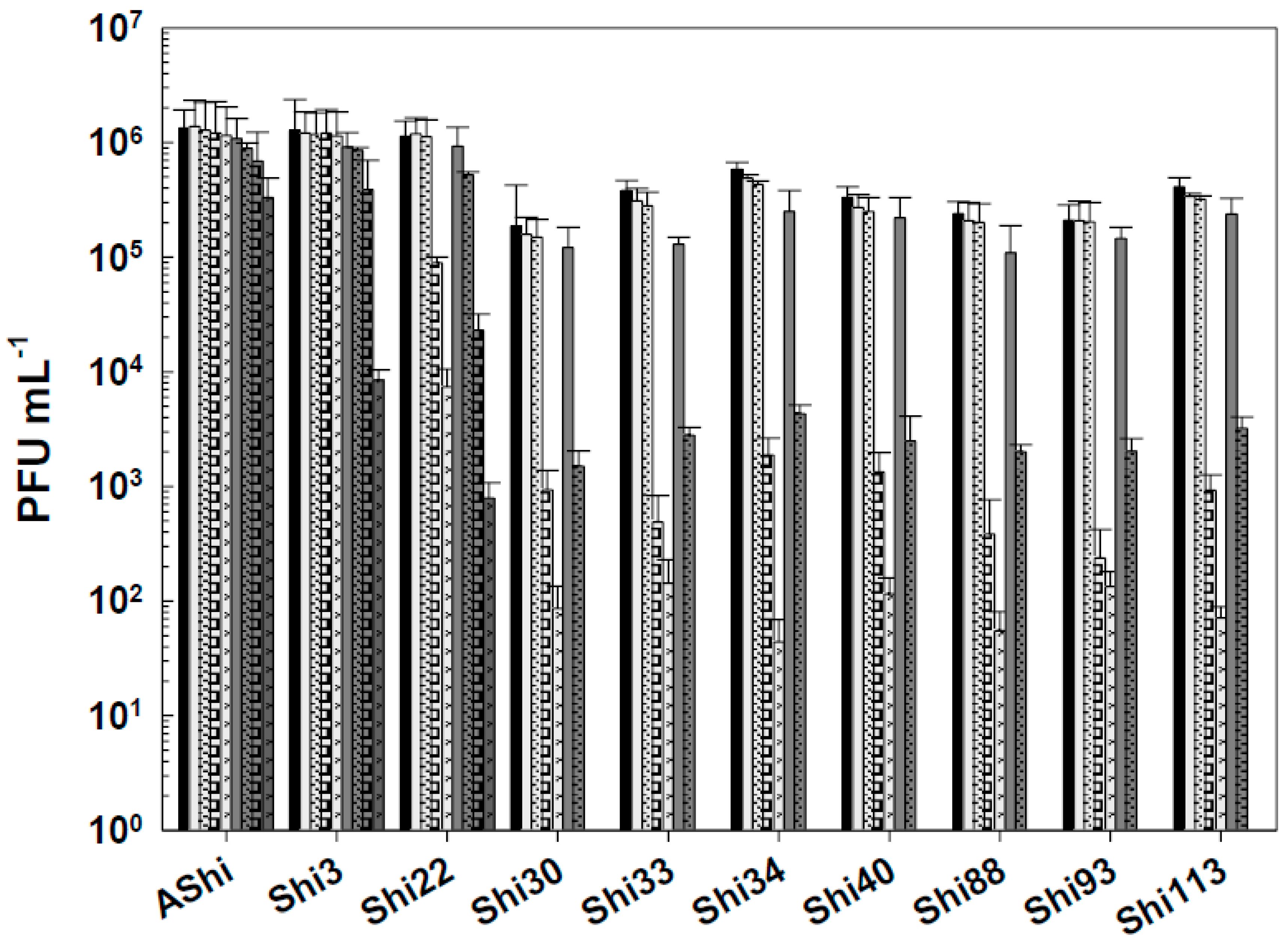

All the phages of

Shigella showed a high resistance to QAC (

Figure 7). The viability of the ten phages was essentially unaffected at 2% after a 30-min period. This was also true only for Shi22 after 60 min, for the other nine phages, significant reductions were observed after the same period of time (60 min). At 3% of QAC, ~ 10

3 – 10

4 PFU mL

-1 remained viable for most phage evaluated within 15 min. As the exposure time increases, the phage counts decreased up to 10

1 (Shi33, Shi34, Shi88), 10

2 (Shi40, Shi93, Shi113) and 10

3 (AShi, Shi3, Shi22, Shi30) PFU mL

-1, an acceptable level of survival of phages when challenged against biocides. QAC at the concentration of 4% reduced phage counts below the detection limit within 15 min, as also was observed at the last time of incubation (24 h) for all the concentrations of QAC tested (data not shown).

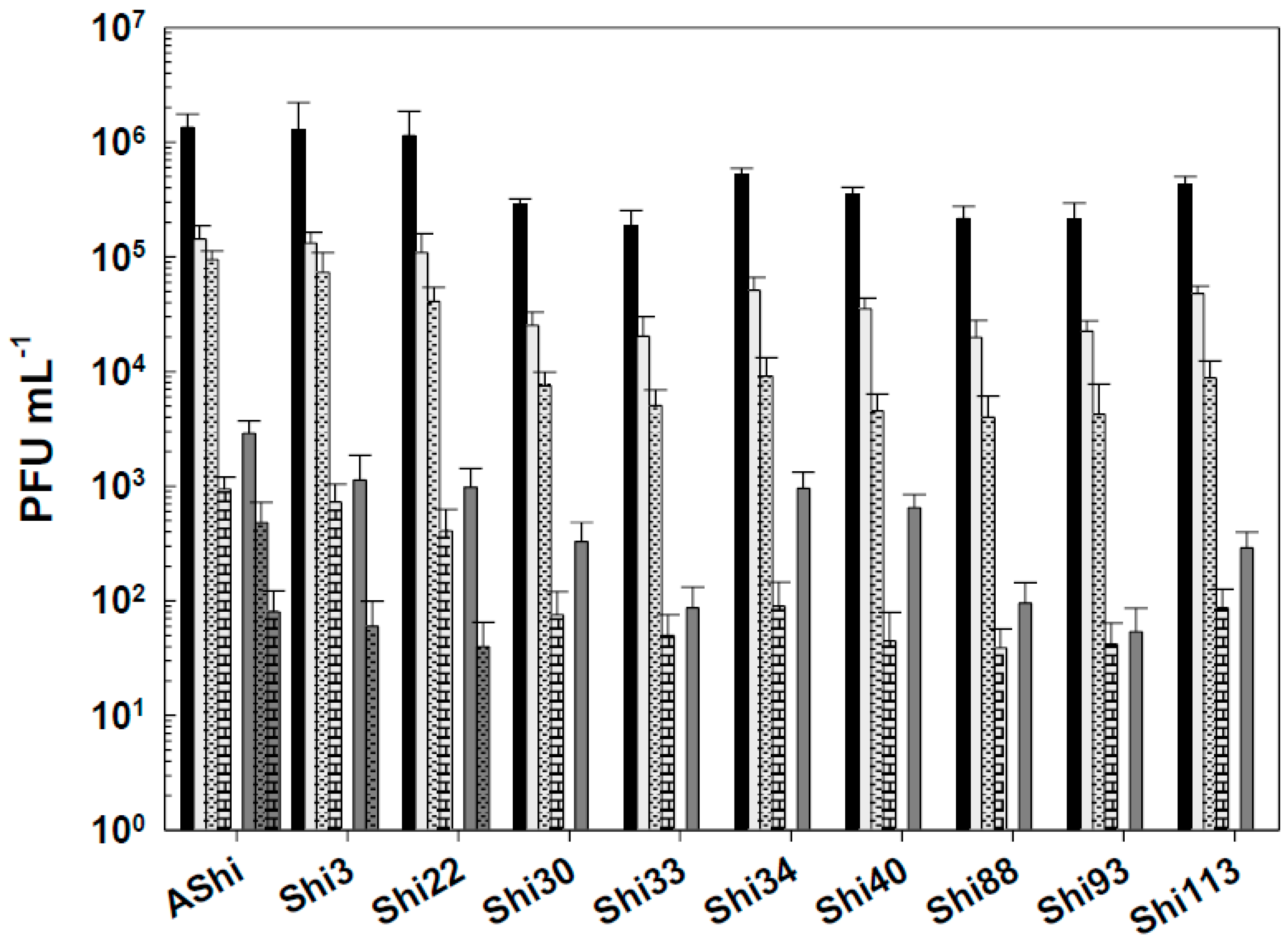

Figure 8 shows the viability of

Shigella-phages against several concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. A similar behavior was found for most viruses evaluated when they were challenged against H

2O

2. At the concentration of 2%, reductions ranged from 1 to 4 log

10 PFU, while 10

4-10

5 and 10

1-10

2 particles remained viable after 30 min and 60 min, respectively. At 3%, a higher viability reduction was observed for the ten phages, however, counts only dropped from ~10

4 PFU mL

-1 (15 min) to 10

1–10

2 PFU mL

-1 after a 30-min exposure. After 60 min, a complete phage inactivation was achieved since no viable particles could be detected. Phage Shi93 proved to have the highest sensitivity to this biocide. Only 10

3 and 10

2 particles were detected after 15 min against 2% and 3% of H

2O

2, respectively, while at longer exposure times, a complete inactivation was observed. At 4%, complete inactivation of

Shigella-phages occurred within 15 min of incubation.

4. Discussion

To determine if the ten

Shigella phages that are being studied can withstand the conditions found in a food matrix and be useful as a biocontrol tool in Agriculture, their viability against different preservatives was assessed. A complete inactivation was observed at low (2%) and high (4%) concentrations of lactic acid, whereas phage particles could be detected after 15 min only at 2%. Regarding acetic and citric acids, all the phages tested showed a high and a moderate resistance, respectively. However, longer incubation times produced a complete inactivation of phages. In accordance with our results, Lee and coworkers found that phage HY01 active against

S. flexneri resulted highly resistant to acid conditions [

9], suggesting that this phage is suitable for food applications. Moreover, others authors found that phages of

Salmonella enteritidis can increase their acid tolerance when they are stressed previously [

20], thus further studies should be carried out in order to evaluate if resistance of the eight phages can be improved. To summarize, when we compared the three different treatments, namely acetic (

Figure 1), lactic (

Figure 2) and citric (

Figure 3) acid, the most effective acid to inactivate phages was the lactic followed in effectiveness by the citric. Therefore,

Shigella-phages evaluated could be employed in combination with chemical preservatives as suggested against other pathogens such as

Listeria [

18] and

Escherichia coli [

21].

Next, to evaluate if our phages can withstand the action of organic acids in a food matrix, their viability was assessed in meat against the preservatives previously assayed. As is already known,

Shigella cells can increase their acid tolerance when they are previously exposed to acidic environments [

12,

22], therefore it is necessary to find phages resistant to organic acids and acidic conditions. In general, when we compared the resistance to preservatives, phages seem significantly more affected by the acids in the solution than by the same acid in the matrix of the meat. This may be due to the pH values of organic acids in solution (pH ~ 2.20 to 2.72) are lower than the pH values achieved on the surface of meat (pH ~ 4.5 to 5.0) after acid application [

23]. Our previous results indicated that phage viability was not significantly affected from pH 5 to pH 11, yet at pH 3, a significant reduction in viability was observed [

14]. Although several biocontrol studies were conducted with phages of

Shigella on different food matrices [

17,

18,

24], assays in which phages were challenged against food-grade additives could not be found. Similarly, other authors found that a phage cocktail was effective to eliminate

S.

flexneri cells from various food [

16]. However, those phages were not challenged against food additives.

Phages can be used in several applications such as decontamination of surfaces and food processing equipment. Commonly used chemical sanitizers are capable of inactivating phages [

25]. Thus, those viruses used in the food industry must be exhaustively evaluated to determine if they can withstand the conditions found in food environments. Most of the phages tested proved to be highly resistant to sodium hypochlorite, ethanol, QAC and hydrogen peroxide since they endured at concentrations up to 100 ppm, 70%, 3% and 3%, respectively. Although, at higher concentration of biocides and for extended periods of incubation phages resulted completely inactivated. Similarly, simultaneous application of bacteriophages active against

Salmonella spp. and chemical preservatives (biocides) resulted in phage inactivation [

26]. Findings presented in this work demonstrated that the use of phages and different biocides against

Shigella strains in food applications is compatible at several biocide concentrations and exposure times. Namely, phages of

Shigella tested can be used in combination with 50 and 100 ppm (1 min) of sodium hypochlorite, 10 and 70% (15, 30 and 60 min) of ethanol, and 2 and 3% (15, 30 and 60 min) of QAC and H

2O

2. In accordance, several authors found a variable resistance among other phages when treated with different biocides [

27,

28], although viability of

S.

flexneri phages had never been previously tested against biocides evaluated in this work.

5. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that at least 103 PFU of the initial number of phages survive in the presence of additives applied in foods. Furthermore, the level of phages that survived was higher in the food matrix suggesting that they can be used in combination with the additives evaluated as an additional hurdle to improve food safety. On the other hand, results indicate that these phages were highly compatible with the biocides evaluated. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate viability of phages active against S. flexneri under the conditions described. In addition, assays in foods with phages had never been previously carried out against S. flexneri strains circulating in our region.

Author Contributions

D.T. Conceptualization; investigation; funding acquisition; methodology; writing—original draft; project administration; writing—review and editing. C.C. methodology. V.A. methodology. A.Q. Conceptualization; methodology, resources; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Agencia Santafesina de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (ASaCTeI, Project IO-2019-008) of Argentina.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this paper are available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff from the English Department of the Facultad de Ciencias Bioquímicas y Farmacéuticas (UNR) for the language correction of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maurelli, A. T. Chapter 7 - Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli: Paradigms for pathogen evolution and host–parasite interactions. In M. S. Donnenberg (Ed.), Escherichia coli 2013, (2nd ed., pp. 215–245). Boston: Academic Press.

- Tack, D.M.; Marder, E.P.; Griffin, P.M.; Cieslak, P.R.; Dunn, J.; Hurd, S.; Scallan, E.; Lathrop, S.; Alison Muse, M.; Ryan, P.; Smith, K.; Tobin-D’Angelo, M.; Vugia, D.; Holt, K.G.; Wolpert, B.J.; Tauxe, R.; Geissler, A.L. Preliminary incidence and trends of infections with pathogens transmitted commonly through food - foodborne diseases active Surveillance network, 10 U.S. sites, 2015–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 369-372.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the control of shigellosis, including epidemics due to Shigella dysenteriae type 1. 2005. WHO Document Production Services, Geneva.

- Ahmed, A.M.; Shimamoto, T. Isolation and molecular characterization of Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shigella spp. from meat and dairy products in Egypt. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 168, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, B.-M.; Wu, S.-F.; Huang, S.-W.; Tseng, Y.-J.; Ji, D.-D.; Chen, J.-S.; Shih, F.-C. Differentiation and identification of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli in environmental waters by a molecular method and biochemical test. Water Res. 2010, 44 (3), 949–955. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Sabir, N.; Bhutta, Z.A. Frequency of isolation of Shigella serogroups/serotypes and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in children from slum areas in Karachi. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2005, 55, 184–188.

- Havelaar, A.H.; Kirk, M.D.; Torgerson, P.R.; Gibb, H.J.; Hald, T.; Lake, R.J.; Praet, N.; Bellinger, D.C.; de Silva, N.R.; Gargouri, N.; Speybroeck, N.; Cawthorne, A.; Mathers, C.; Stein, C.; Angulo, F.J.; Devleesschauwer, B. World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Med, 2015, 12, e1001923. [CrossRef]

- Torrez Lamberti, M.F.; Lopez, F.E.; Valdez, P.; Bianchi, A.; Barrionuevo Medina, E.; Pescaretti, M.L.M.; Delgado, M.A. Epidemiological study of prevalent pathogens in the Northwest region of Argentina (NWA). PLoS One 2020, 15 (10), e0240404. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Ku, H-J.; Lee, D-H.; Kim, Y-T.; Shin, H.; Ryu, S.; Lee, J-H. Characterization and genomic study of the novel bacteriophage HY01 infecting both Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shigella flexneri: Potential as a biocontrol agent in food. PLoS ONE 2016, 11 (12): e0168985. [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, A.; Aruachan, D.; Burgos, M.; Angeleri, P.I. Direccion Nacional de Epidemiologia y Analisis de la Situacion de Salud Ministerio de Salud de la Nacion Argentina. Boletın Integrado de Vigilancia 2018, 1-90.

- Tetteh, G.L.; Beuchat, L.R. Exposure of Shigella flexneri to acid stress and heat shock enhances acid tolerance. Food Microbiol. 2003, 20, 179–185. [CrossRef]

- Small, P.; Blankenhorn, D.; Welty, D.; Zinser, E.; Slonczewski, J.L. Acid and base resistance in Escherichia coli and Shigella flexneri: role of rpoS and growth pH. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 1729–1737. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lee, I.; Frey, J.; Slonczewski, J.L.; Foster, J.W. Comparative analysis of extreme acid survival in Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 4097–4104. [CrossRef]

- Tomat, D.; Gonzales, A.; Aquili, V.; Casabonne, C.; Quiberoni, A. Characterization of ten newly isolated phages against the foodborne pathogen Shigella flexneri. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022a, 46 (6), e15676.

- Tomat, D.; Aquili, V.; Casabonne, C.; Quiberoni, A. Influence of physicochemical factors on adsorption of ten Shigella flexneri phages. Viruses 2022b, 14, 2815. [CrossRef]

- Magnone, J.P.; Marek, P.J.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Senecal, A.G. Additive approach for inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella spp. on contaminated fresh fruits and vegetables using bacteriophage cocktail and produce wash. J. Food Protect. 2013, 76, 1336-1341. [CrossRef]

- Soffer N.; Woolston, J.; Li, M.; Das, C.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage preparation lytic for Shigella significantly reduces Shigella sonnei contamination in various foods. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175256. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Bao, H.D. Phage inactivation of foodborne Shigella on ready-to-eat spiced chicken. Poul. Sci. 2013, 92, 211-217. [CrossRef]

- Tomat, D.; Mercanti, D.; Balague, C.; Quiberoni, A. Phage biocontrol of enteropathogenic and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli during milk fermentation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 57, 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, T.J.; Richardson, N.P.; Statton, K.M.; Rowbury, R.J. Effects of temperature shift onacid and heat tolerance in Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 3120–3122.

- Tomat, D.; Casabonne, C.; Aquili, V.; Balague, C.; Quiberoni, A. Evaluation of a novel cocktail of six lytic bacteriophages against Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli in broth, milk and meat. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 434–442. [CrossRef]

- Gorden, J.; Small, P.L.C. Acid resistance in enteric bacteria. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 364–367. [CrossRef]

- Tomat, D.; Balague, C.; Casabonne, C.; Verdini, R.; Quiberoni, A. Resistance of foodborne pathogen coliphages to additives applied in food manufacture. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 50-54. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, K.; Zhang, L.; Soleimani Delfan, A.; Komijani, M.; Hedayatkhah, A.; Bao, H.; Barazandeh, M.; Mansoorianfar, M.; Pang, M.; He, T.; Bouzari, M.; Wang, R. Effective control of Shigella contamination in different foods using a novel six-phage cocktail. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 144, 111137. [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, A.T.; Nannapaneni, R.; Kiess, A.; Sharma, C.S. Reduction of Salmonella on chicken meat and chicken skin by combined or sequential application of lytic bacteriophage with chemical antimicrobials. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 207, 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.; Seguer, J.; Rocabayera, X.; Manresa, A. Cellular effects of monohydrochloride of L-arginine, Nα-lauroyl ethylester (LAE) on exposure to Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 96, 903-912.

- Mercanti, D. J.; Guglielmotti, D. M.; Patrignani, F.; Reinheimer, J. A.; Quiberoni, A. Resistance of two temperate Lactobacillus paracasei bacteriophages to high pressure homogenization, thermal treatments and chemical biocides of industrial application. Food Microbiol. 2012, 29, 99e104. [CrossRef]

- Tomat, D.; Balague, C.; Aquili, V.; Verdini, R.; Quiberoni, A. Resistance of phages lytic to pathogenic Escherichia coli to sanitisers used by the food industry and in home settings. Int. J. Food Sci, Technol. 2017, 53 (2), 533-540. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).