1. Introduction

Salmonellosis, an infection caused by

Salmonella spp., is one of the most significant foodborne zoonotic diseases [

1], accounting for an estimated 95.1 million cases of gastroenteritis each year [

2]. In humans, infection is commonly linked to the consumption of raw or undercooked meat, eggs, and other poultry-derived products [

3]. Many

Salmonella enterica strains are associated with poultry; the avian-adapted biovars

Gallinarum and

Pullorum are primarily restricted to birds and rarely infect humans [

4], the serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium are among the most prevalent in poultry and are the major cause of foodborne salmonellosis [

5]. For humans, ready-to-eat (RTE) foods are of particular concern, since they are consumed without further cooking, which would normally eliminate Salmonella, but also processed food may be contaminated after processing and cause infection [

6,

7]. While in poultry, Salmonella transmission occurs through several ways including contaminated feed, contact with infected animals, and vertical transmission from breeding stock to offspring [

8]. Therefore, implementing effective control strategies at both the farm and food production levels is crucial to ensure food safety and public health [

9].

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics in human medicine and agriculture have accelerated the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) strains among these pathogens. This limits the effectiveness of first-line antibiotics, further complicates treatment, and leads to persistent infections [

10,

11]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified AMR as one of the greatest threats to global public health, estimating that, without effective interventions, it could lead to 10 million deaths annually by 2050 [

6,

12]. In agriculture, antibiotics are often used beyond therapy, including for growth promotion and disease prevention, which fosters the development of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. As a result, resistant strains from different bacterial species, including

Salmonella enterica,

Escherichia coli, and

Staphylococcus aureus, have been detected in dairy products, RTEs, and meat, representing a serious threat to public health and highlighting the need for new hygiene practices and effective control strategies [

7,

10,

12,

13].

One of the most promising alternatives to antibiotics is bacteriophages, which are naturally occurring viruses that selectively infect and lyse bacterial pathogens, highlighting their potential role in eradicating and eliminating resistant strains [

14]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved bacteriophage products as generally recognized as safe (GRAS), permitting their application in livestock and poultry products [

15]. Numerous studies have shown promising results for using bacteriophage combinations to decrease the bacterial population extrinsically on experimentally contaminated feed [

16], raw meat, vegetables [

17], and intrinsically administered as doses after antibiotic treatment failed [

14].

This study aimed to isolate and characterize a novel MDR- Salmonella Enteritidis-targeting bacteriophage with extraordinary temperature stability. These findings provide a foundation for the development of future bacteriophage-based interventions for therapy, food safety, and biotechnology.

2. Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

The twenty MDR-

Salmonella Enterica strains used in this study are clinically isolated strains from Lebanon, and were obtained from the bacteriology lab, Department of Experimental Pathology, Immunology and Microbiology, American University of Beirut, Lebanon; SAL281 (SAMN52031898), SAL282 (SAMN52031899), SAL286 (SAMN52031900), SAL287 (SAMN52031901), SAL288 (SAMN52031902), SAL293 (SAMN52031905), SAL220 (SAMN43315390), SAL222 (SAMN43315391), SAL226 (SAMN43315395), SAL227 (SAMN43315396), SAL228 (SAMN43315397), SAL236 (SAMN43315404), SAL240 (SAMN43315408), SAL241 (SAMN43315409), SAL242 (SAMN43315410) SAL294 (SAMN52033040) SAL295 (SAMN52033041) SAL256 (SAMN43309870), SAL262 (SAMN43309873) SAL271 (SAMN43309880)

Table A1-A4. Bacteria were cultured first on SS (Salmonella-Shigella) agar, then on LB (Luria–Bertani) agar, and for storage, bacteria were stored at -20 °C in 50% glycerol.

Screening and Isolation of S01 Bacteriophage

Sewage samples were collected from twenty-three sites in Lebanon. Each sample centrifuged at 6400 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove debris, filtered through a 0.2 µm syringe filter, and pooled into eight combinations for primary screening against eight Salmonella strains. 50 µL of sewage combination was mixed with 50 µL bacterial suspension (0.5 McFarland) and 50 µL LB Broth in a 96-well round-bottom plate which was incubated in a plate reader for 8 hours at 37 °C to monitor the optical density (OD) at 600 nm every 30 minutes. The OD of each well was compared to that of the positive and negative control wells.

10 mL of the sewage combination corresponding to the well that showed decreased absorbance was enriched with 2mL 0.5 MacFarland bacterial suspension and 2 mL LB Broth overnight at 37 °C. After centrifugation at 6400 xg for 15 minutes, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 µm syringe filter, and a conventional plaque assay was done. Briefly, the lysate was diluted in LB Broth, mixed with 1mL 0.5 MacFarland bacterial suspension and 3 mL top agar (semi-solid 0.6% agar), and poured into LB agar plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

One plaque is picked and suspended in 0.5 mL SM buffer (SM buffer: 100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4.7H2O, and 50 mM Tris-HCl [1 M, pH 7.5]) centrifuged at 8000 xg for 5 minutes to pellet debris, and 100 µL of the supernatant is enriched with 10 mL LB Broth and 2 ml 0.5 MacFarland bacteria suspension overnight at 37 °C. These steps were repeated for 3 rounds to ensure the purity of the bacteriophage, which were then stored at 4 °C.

Plaque assay was performed in triplicate, and plaques were counted on the plate having 30 to 300 plaques to determine the PFU titer of the enrichment according to the following formula:

Bacteriophage Bacteriolytic Activity and Host Range

For bacteriolytic activity four multiplicity of infection (MOI) were tested: 10, 1, 0.1, and 0.01 by mixing 105 µL bacteriophage lysate (PFU/ml were adjusted for different MOIs) with 75 µL 0.5 MacFarland bacterial suspension in duplicates in a 96-well round-bottom plate, which were incubated in a plate reader for 8 hours at 37 °C to monitor the OD at 600nm every 30 minutes for 8 hours. For host range, 100 µL of bacteriophage lysate was added to 900 µL LB Broth and 1 mL 0.5 MacFarland bacterial suspension, and 3 mL LB top agar (semi-solid 0.6% agar) and poured into LB agar plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

Bacteriophage One-Step Growth Curve and Adsorption Rate Assay

One-step growth curve and adsorption rate assay was done on MOI 10: 15 mL 0.5 MacFarland bacterial suspension were prepared from which 900 µL were added to fifteen 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, which were labeled according to the sampling time points (3, 5, 10, 15 … 70 min) while 900 µL LB Broth was added to the tube labeled 0 min. Beginning at the 70-minute tube, 100 µL of the prepared bacteriophage stock was sequentially added to each tube at 5-minute intervals, proceeding in reverse order until the 3-minute tube. Finally, 100 µL of bacteriophage suspension was also added to the tube labeled 0. All tubes were centrifuged at 8000 xg for 5 min, supernatants were carefully recovered, placed on ice, and serially diluted and plated into LB agar plates after adding 1 mL 0.5 MacFarland bacterial suspension and 3 mL LB top agar (semi-solid 0.6% agar), and incubated overnight at 37 °C. PFU were counted to determine bacteriophage counts at each time point. Adsorption tests were done on resistant strains by incubating 100 µL from the bacteriophage stock with 900 µL bacterial suspension, followed by centrifugation at 8000 xg for 5 min and supernatant retention at timepoints 0 and 15 minutes, which were plated to compare the PFU count.

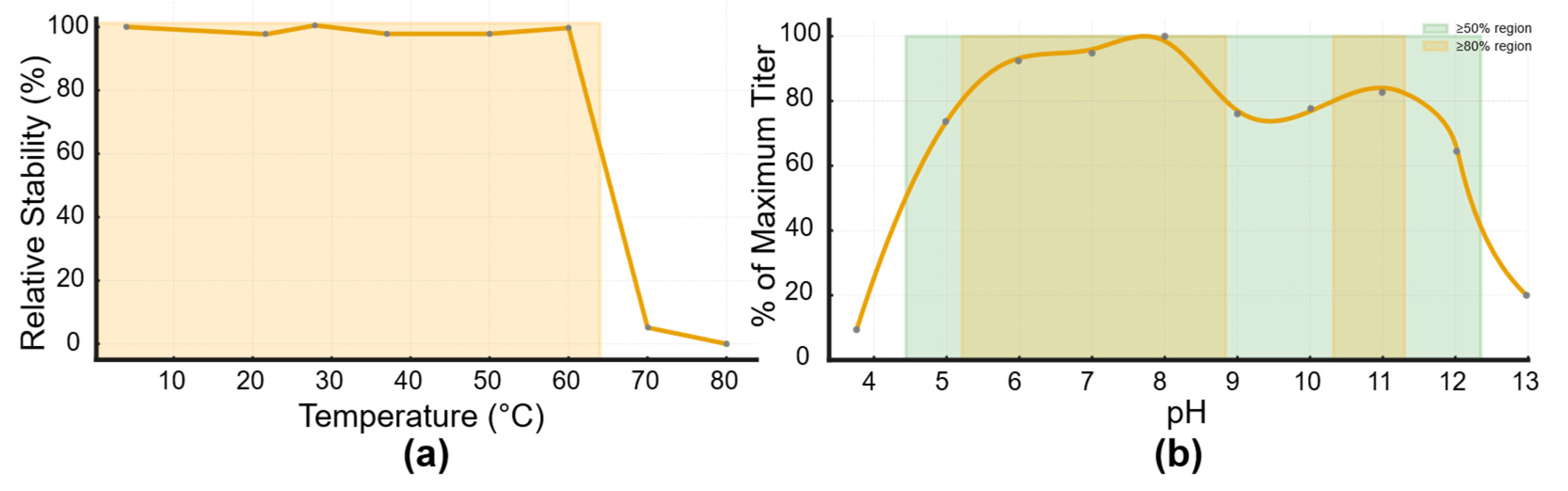

Bacteriophage Thermal and pH Stability

bacteriophage thermal stability was performed at 4, 22, 37, 50, 60, 65, 70, 75, and 80 °C by incubating 250 µL bacteriophage lysate (diluted in LB Broth) for 2 hours. The same procedure was performed to determine the stability at 65 °C and 70 °C for 5, and 4 hours respectively.

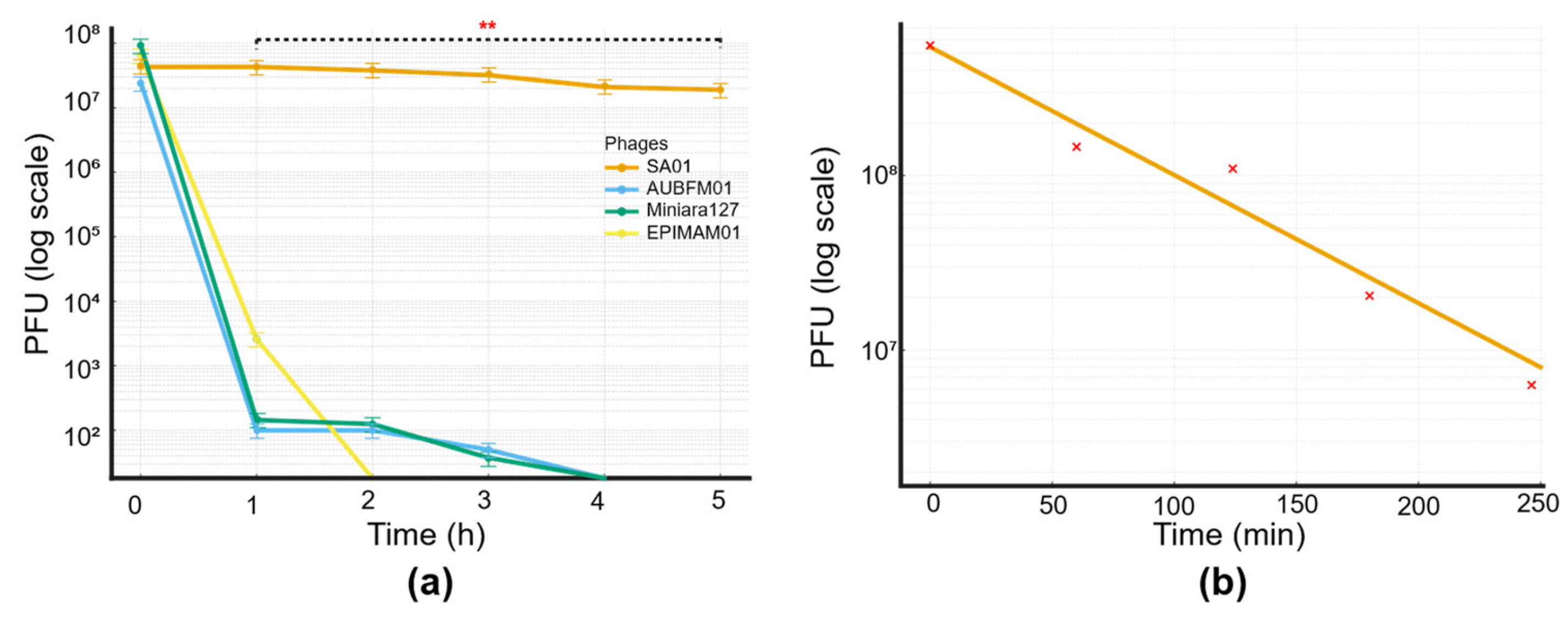

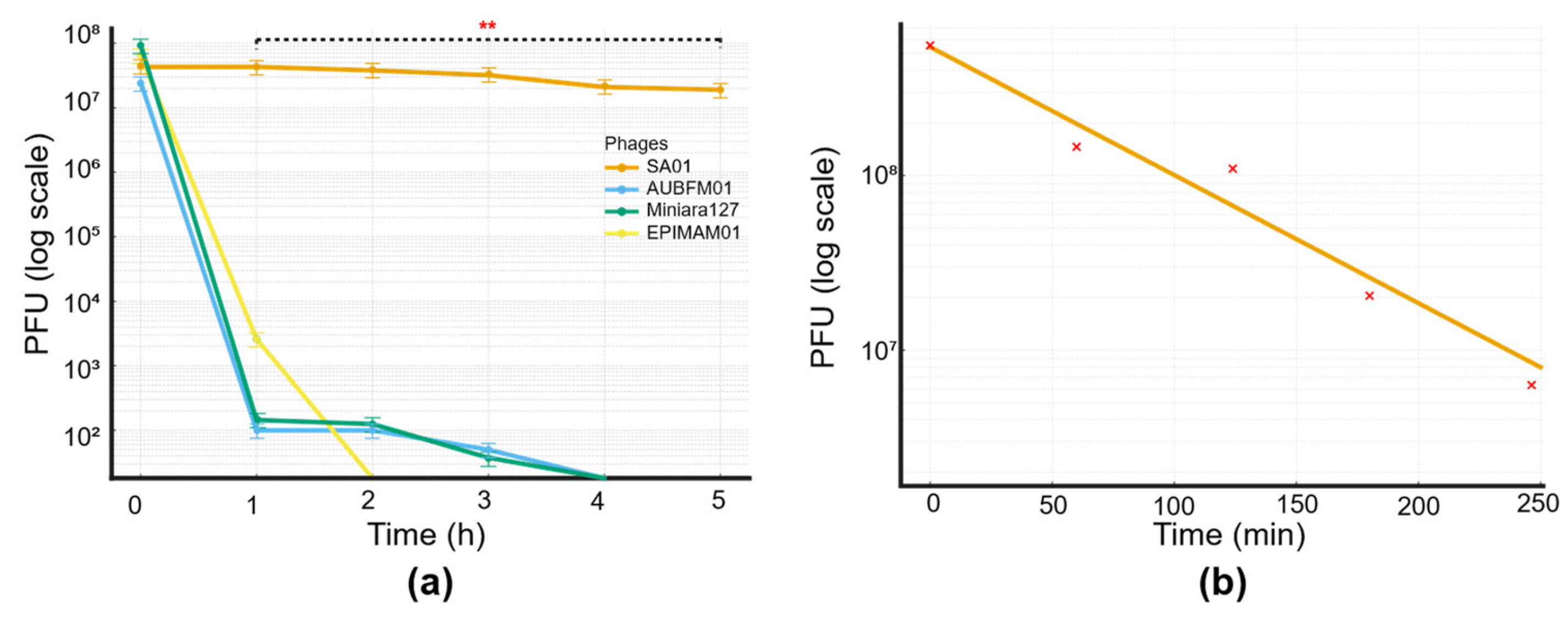

Three purified and characterized bacteriophages from our lab: EPIMAM01 (E. coli ATCC targeting bacteriophage; PQ493298), Miniara127 (Klebsiella pneumoniae targeting bacteriophage; PX094878), and AUBFM01 (Acinetobacter baumannii targeting bacteriophage; PX094877) were used for stability comparison. The bacteriophages were diluted to have approximately the same initial concentration, and then the stability test was performed as described before.

Buffered LB Broth at different PH values is used to determine the PH stability. 100 µL bacteriophage lysate was added to 900 µL buffered LB Broth and incubated for 2 hours at 37 °C.

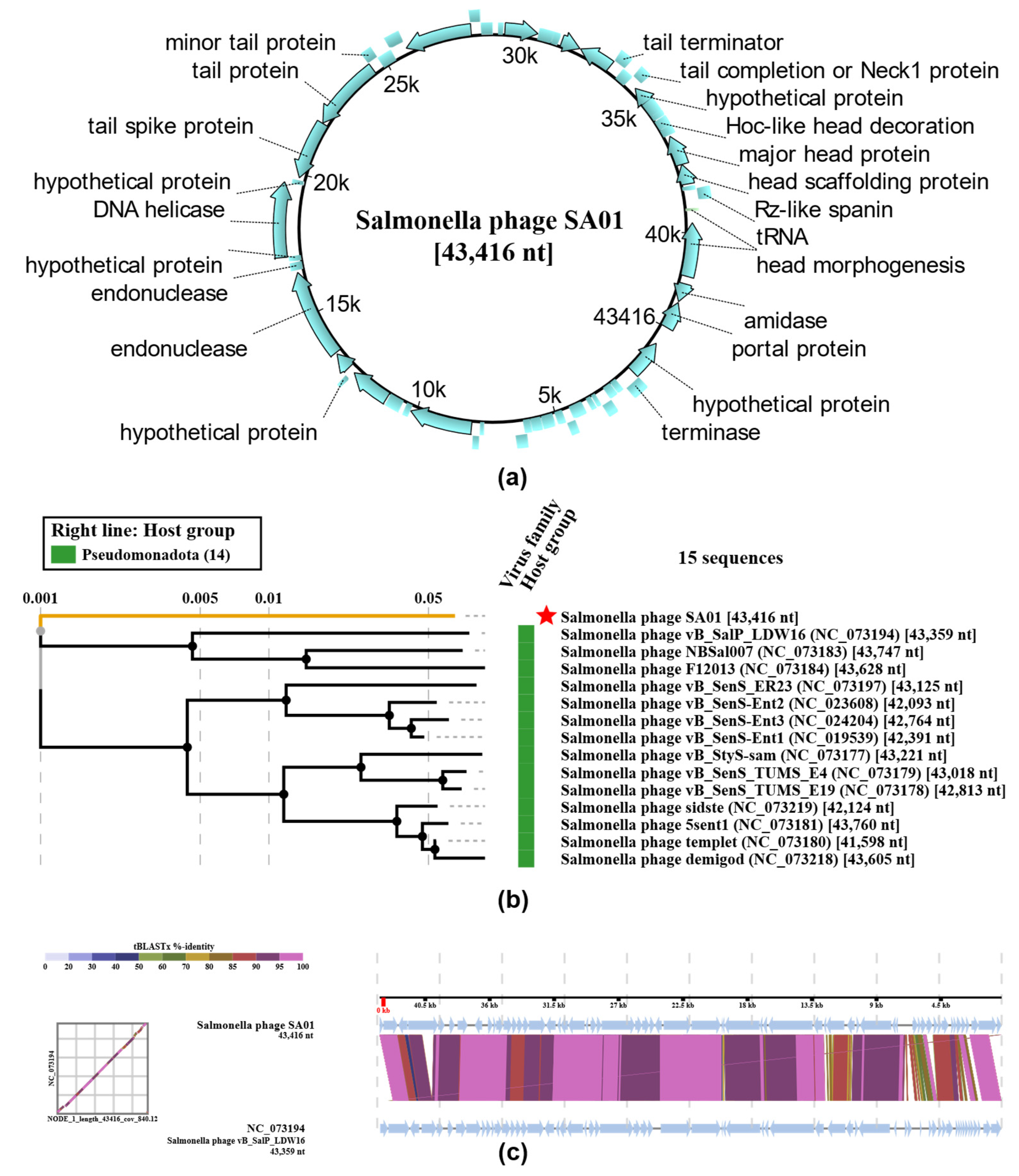

Bacteriophage Genome Sequencing and Analysis

The bacteriophage genome was extracted using a bacteriophage DNA extraction kit, NORGEN BIOTEK KIT, according to the manufacturer’s protocol and quantified by Qubit™ Fluorometer using the Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, then sequenced using using the Nextera kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced with 2 × 250 bp reads on a MiSeq system (Illumina) at the DNA Sequencing Facility of the American University of Beirut. Raw paired-end sequencing reads were quality-checked using FastQC. Low-quality bases and adapter sequences were trimmed with Trim Galore; the resulting high-quality reads were assembled de novo with SPAdes. Assembly quality was assessed using QUAST, and the main high-coverage contig was selected for downstream analyses. Genome annotation was performed using Pharokka. ViPTree (

https://www.genome.jp/viptree) was used to generate a virus proteomic tree based on the similarities of whole-genome sequences [

18]. The PhageLeads server (

https://phageleads.dk/) is used to predict toxins, virulence, or antimicrobial resistance genes [

19].

4. Discussion

It is beyond question that the antimicrobial resistance crisis has become a significant global threat. As the number of MDR strains, as well as MDR-associated mortality, continues to rise each year, experts consider that we are entering a post-antibiotic era [

21].

In this context, and as nearly 70% of foodborne infections are caused by food-transmitted pathogens, effective strategies to prevent and control these microorganisms are critical to ensure food safety and public health [

22]. A principal causative agent of these infections is

Salmonella, and according to European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Salmonella ranks as the second most frequent cause of foodborne illness in the European Union [

23]. Consistent with this global concern, an ongoing study at the Department of Experimental Pathology, Immunology & Microbiology, Center for Infectious Diseases Research and WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference & Research on Bacterial Pathogens at the American University of Beirut, has identified a significant increase in antibiotic resistance in

Salmonella Enteritidis isolates in Lebanon in the last 2 decades. As poultry meat, the primary reservoir of

Salmonella, has reached an annual consumption of 140 million tons—making it the most widely consumed meat globally—there is an urgent need to develop novel strategies to control these pathogens[

24].

In light of these challenges, bacteriophages are a promising candidate as a potential antibiotic alternative for both therapy and food safety applications. Being highly specific, self-replicating, and MDR targeting particles, bacteriophages would have minimal effect on human cells or the normal microbiota while lysing their host. Unlike major antibiotics that act broadly against bacterial populations, often disrupting microbiota, usually requiring probiotic therapy afterward, bacteriophages are highly specific, targeting their host through complex, strict, highly specific interaction with its specific host receptor before DNA injection and infection, and thus sparing every other bacterial population.

Salmonella phage SA01 targeted and lysed 12 out of 20 tested clinical MDR-Salmonella Enterica strains collected from human stool, and with its extraordinary thermal stability and strong lytic activity is a potential biological agent for therapy, food safety, and biotechnology.

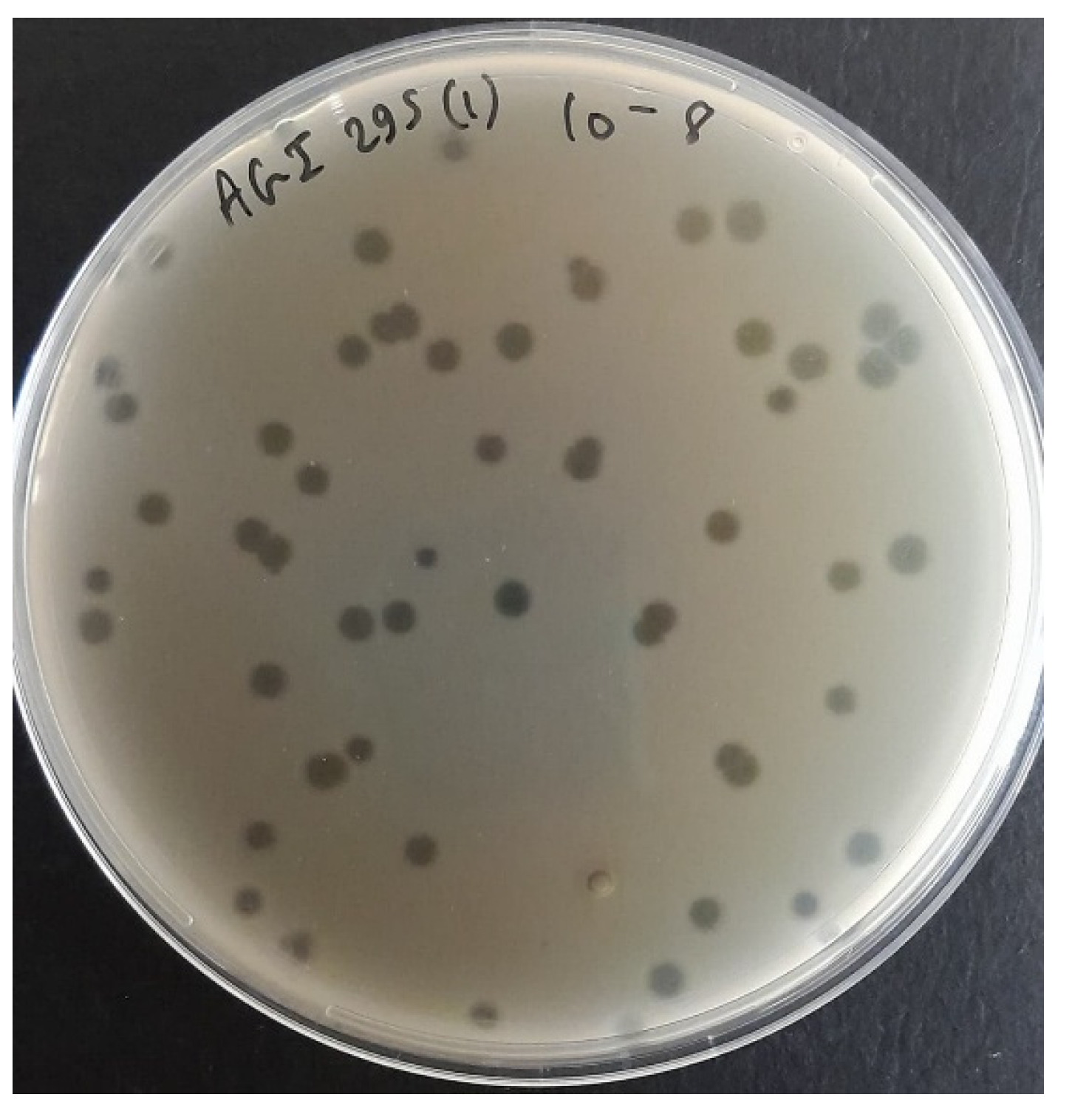

Sewage is an excellent medium for bacteriophage hunting, since it is rich in bacteria and thus rich in their corresponding parasites. Samples were screened in combinations of three to increase the chance of finding a Salmonella-targeting bacteriophage; three bacteriophages were isolated from the eight screened combinations. Salmonella phage SA01 was isolated from AGI (Ain EL-Mreiseh, Baabda, and Baalbak) sewage combination, which was enriched overnight with its host to amplify rare bacteriophages. SA01 formed large, round, clear, suggesting its lytic life cycle, which was confirmed later by genomic analysis, and indicating fast replication cycle and high diffusion rate in semi-solid agar (0.6% LB agar). A genetically homogeneous bacteriophage population is critical for downstream experiments reliability, thus the SA01 plaque were picked and enriched three times. A plaque results from the infection of a single bacterium by a single infectious bacteriophage particle. As the bacteriophage replicates and lyses host cells, it creates a zone of clearing (plaque) through sequential rounds of infection, and thus all bacteriophages in one plaque are genetically identical -despite somatic mutations- since they all originate from one initial infecting bacteriophage [

25].

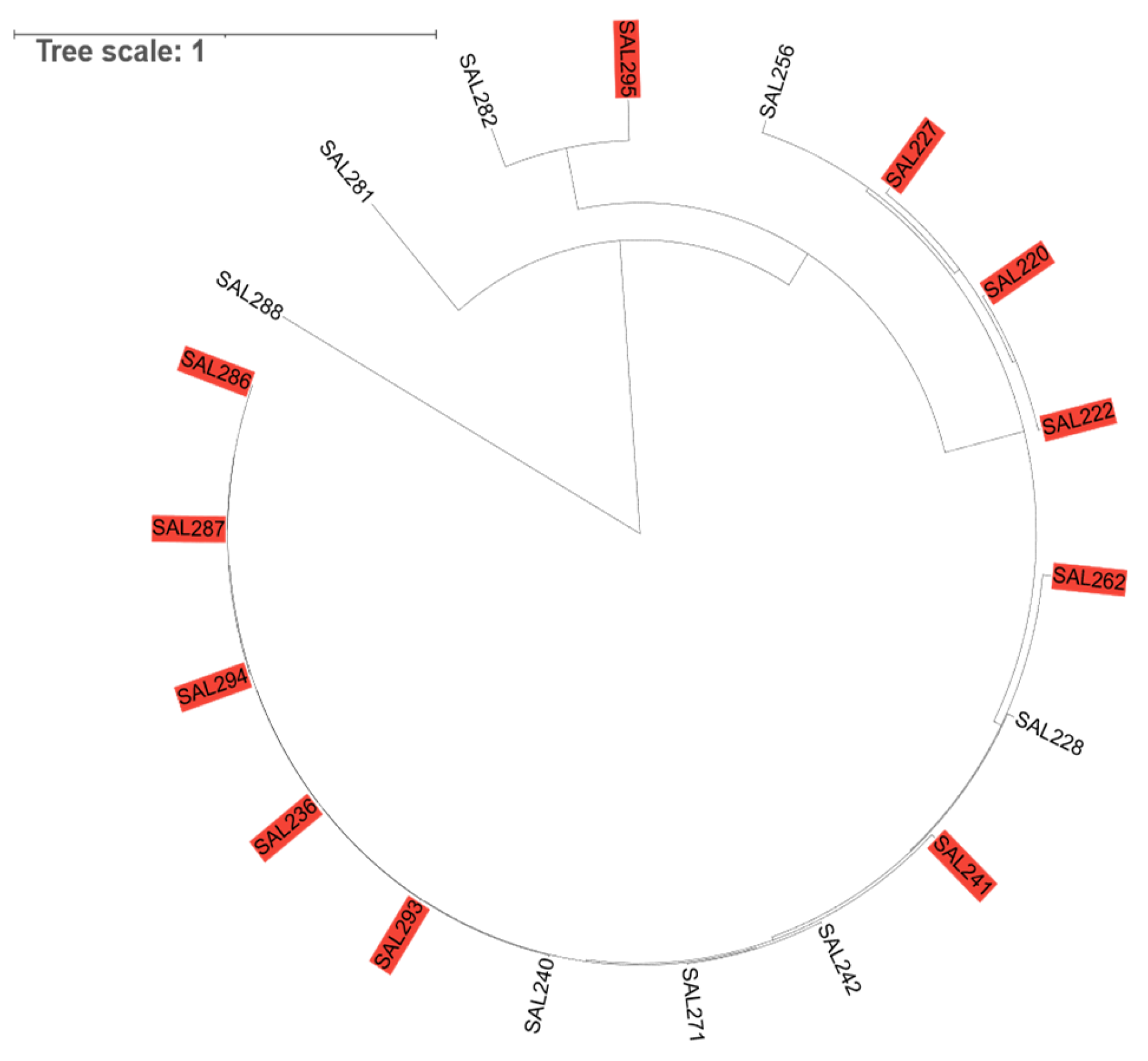

SA01 adsorbed successfully to 100% of the tested MDR-Salmonella strains and lysed 60% of them. The resistance strains are likely to possess intrinsic defense mechanisms against SA01, such as CRISPR-Cas systems or restriction–modification enzymes. The receptor of SA01 is found on all tested MDR-

Salmonella Enterica strains, with its very rapid adsorption rate at high MOI, we can say that this receptor is not restricted to rare variants but its conserved and commonly expressed on various strains, given that phylogenetic analysis revealed genetic diversity in tested

Salmonella Enterica strains while some strains are closely related

Figure 3. This broad host range makes SA01 a good candidate for biocontrol and bacteriophage therapy.

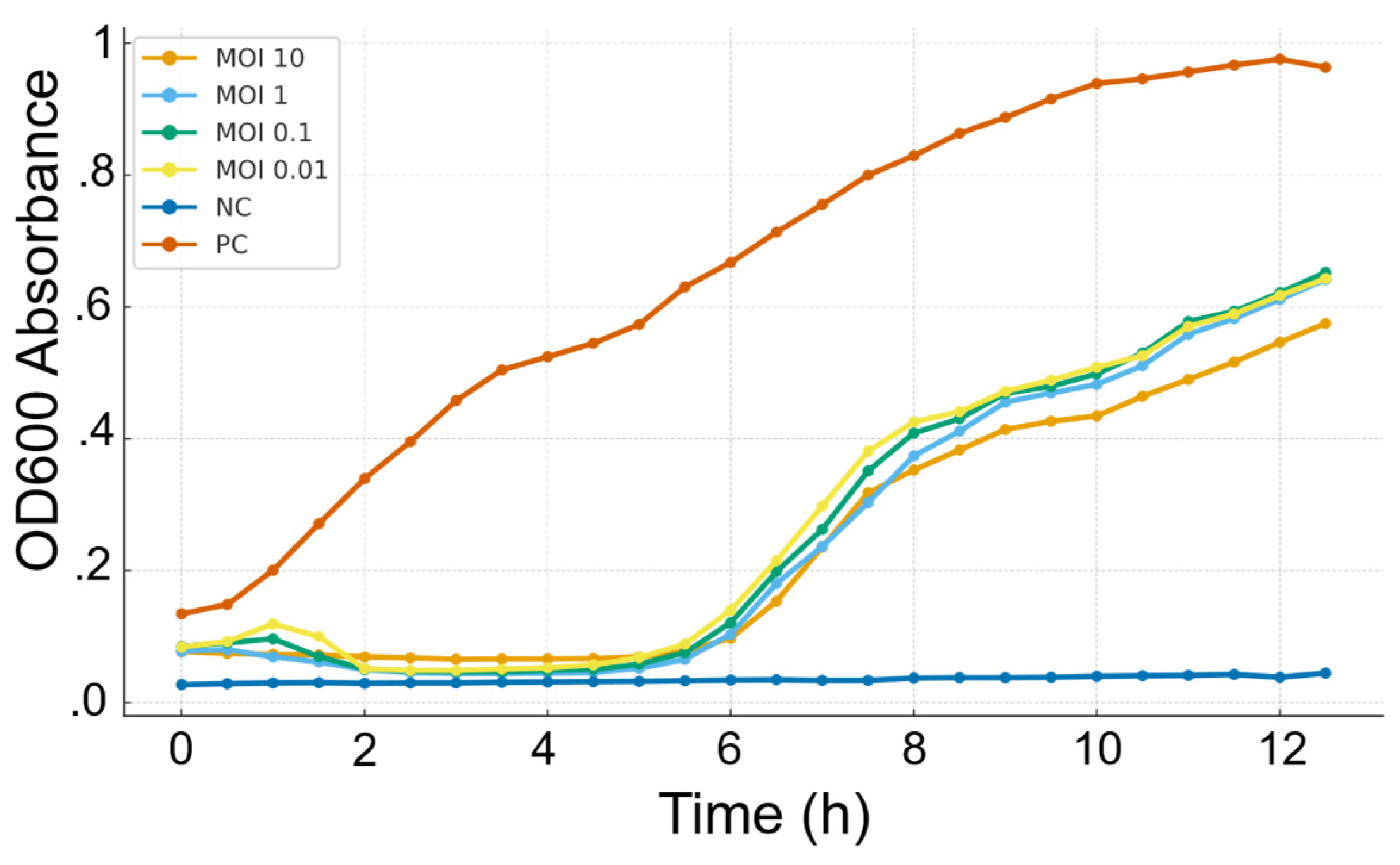

Bacteriolytic activity of SA01 showed that it strongly suppressed the bacterial growth in the first 4 hours, but regrowth of resistant variants was observed thereafter, which is common for single bacteriophage treatment and highlights the importance of bacteriophage cocktail in biocontrol. Different MOIs have the same bacterial inhibition profile, suggesting that SA01 has a rapid replication cycle outpacing the growth rate of the bacteria, even at a ratio of 1 bacteriophage for 100 bacterial cells (MOI 0.01). Such results highlight its strong lytic potential and support its applications in low concentrations.

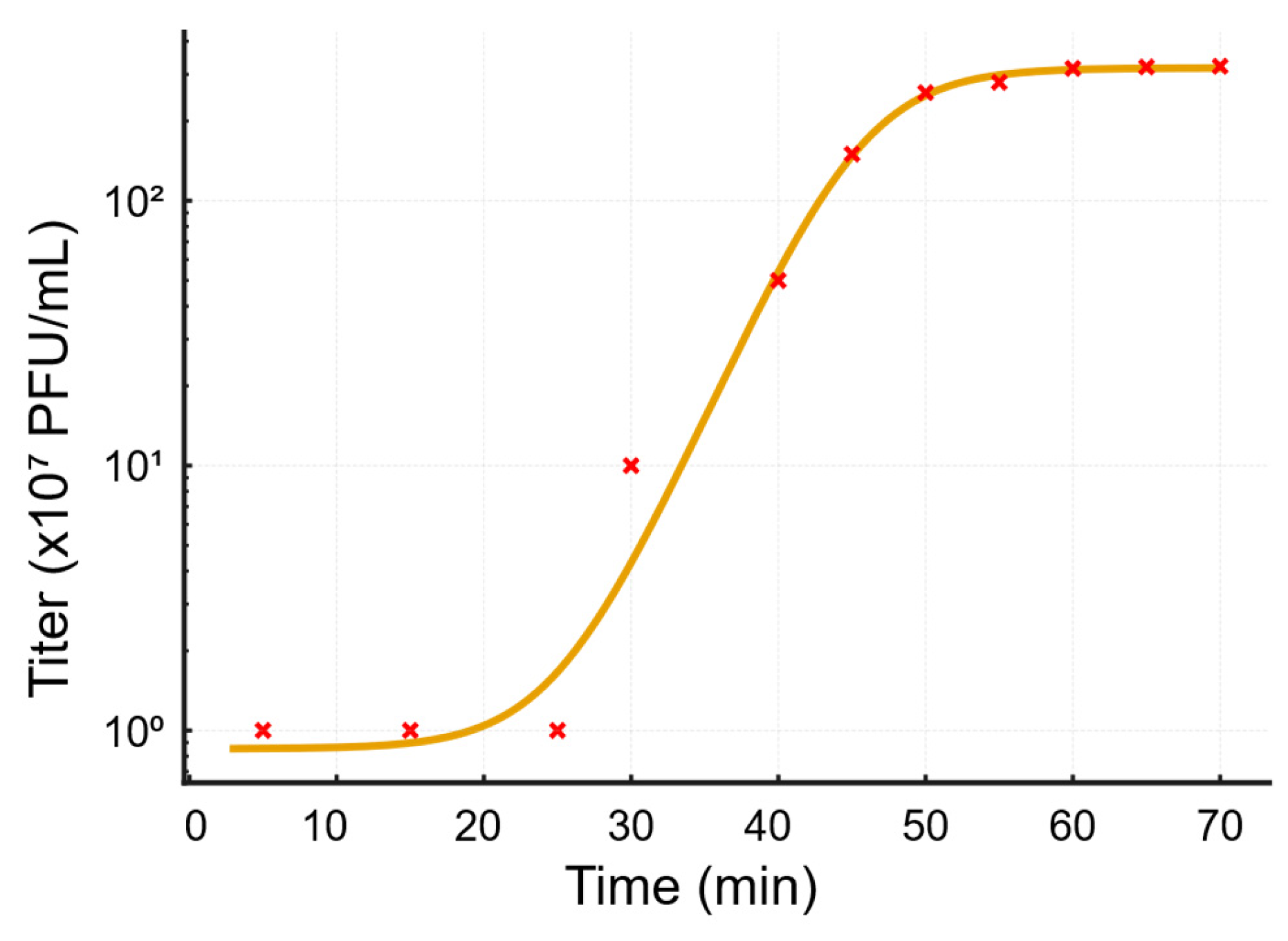

The rapid adsorption rate of SA01 indicates high affinity between the bacteriophage and its receptor, and suggests that the host expresses multiple receptors that were not saturated at MOI 10. On the other hand, a latency period of 20 minutes and a burst size of 320 per infected cell allow the bacteriophage to strongly overpass the bacterial growth rate, and would explain the high efficiency of bacterial growth inhibition at MOI 0.01 and its large plaque size. A burst size of 320 bacteriophage particles per 1 bacterial cell reflects a highly virulent lytic bacteriophage, that can shift MOI from 0.01 to 1 in one replication cycle, and higher than previously isolated bacteriophages, to mention some: PSDA-2 target Salmonella Typhimurium, which has a burst size of 120 PFU per cell [

26], and LPSE1 Salmonella enterica targeting bacteriophage have a 94 PFU per cell [

27]. This further highlights its potential applications in controlling MDR-

Salmonella strains.

While most bacteriophages become inactivated at 60-65 °C in few minutes [

28,

29,

30], SA01 withstands 65 °C with minimal decrease in viable bacteriophage particles after 2 hours and with a minimal decrease after 5 hours, moreover starting from 10^9 PFU, viable bacteriophage particles were detected after heating at 78 °C for 2 hours. This extraordinary stability shed light on its unique capsid structure, which preserves bacteriophage viability at such high temperatures, at which most bacteriophages and foodborne pathogens (mesophiles) are inactivated completely. Food processing often includes mild heating, pasteurization, and hot holding, which often inactivate bacteriophages and limit their usage in processed food. However, the strong thermal stability of SA01 enables it to withstand such conditions, supporting its potential use in food safety applications alongside with its stability over a broad range of PH (3.7 to 11.3), which covers the PH of most foods. Also, it could be utilized in raw and RTE foods, where undesirable chemicals and preservatives are used, to avoid foodborne pathogens. To address one of the major sources of Salmonella and especially MDR strains, SA01 bacteriophage could be applied to poultry production and animal feed pellets, which are often processed at 60–70 °C, to have the synergic effect between high temperature and bacteriophage lytic activity. In the near future, bacteriophage cocktails may provide an alternative to antibiotics in poultry and agriculture to control the emergence of antimicrobial resistance and to preserve the remaining efficacy of antibiotics. Besides, in the food industry and domestic kitchen, thermostable bacteriophages such as SA01 can be applied in sanitation strategies targeting food-contact surfaces and equipment, which often serve as major reservoirs and vehicles for the transmission of foodborne salmonella.

Moreover, SA01 thermostable Salmonella-specific capsid proteins can be utilized in biotechnology as a nucleic acid vector for genetic engineering applications, as bacteriophages have long been used for cloning. Even in non-heat-based applications, such as biosensors, rapid pathogen detection assays, the use of thermostable bacteriophages could prolong the shelf life of these products and reduce their inactivation under mild environmental stresses such as storage fluctuations, transportation, or light exposure.

The annotation of the SA01 genome showed that it encodes many important proteins, such as the Major capsid protein, tail sheath, tail fiber, DNA polymerase, Endolysin, Holin, and Spanins, but it should be noted that the thermostability of the bacteriophage capsid does not necessarily imply thermostability of all encoded enzymes. While the capsid protects the genome under harsh environmental conditions, bacteriophage enzymes such as endolysins are usually adapted to the physiological temperature of the host. Also, genome analysis by pharroka and phageleads showed no lysogeny, virulence, or AMR genes, which ensure the lytic life cycle of SA01 and make it a potential safe candidate, unlike temperate bacteriophages, which pose risks of gene transfer and antibiotic resistance.

Although bacteria can also develop resistance to bacteriophages, but unlike antibiotics, bacteriophages are capable of coevolution adapting to overcome bacterial defenses. If one day bacteriophages took the place of antibiotics and were used in an uncontrolled manner, local microbial dynamics in the environment would be altered.

Figure 1.

Morphological characteristics of Salmonella phage SA01: Plaque morphology on double-layer agar plate after third round purification.

Figure 1.

Morphological characteristics of Salmonella phage SA01: Plaque morphology on double-layer agar plate after third round purification.

Figure 2.

Bacteriolytic activity of Salmonella phage SA01 against its host at different multiplicities of infection (MOIs). Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring OD600 absorbance over 12 hours. In the absence of bacteriophage (control, orange), bacteria grew steadily to high densities. In contrast, bacteriophage-infected cultures showed dose-independent inhibition of bacterial growth. Bacterial regrowth occurred after an initial inhibition phase, indicating partial control by the bacteriophage.

Figure 2.

Bacteriolytic activity of Salmonella phage SA01 against its host at different multiplicities of infection (MOIs). Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring OD600 absorbance over 12 hours. In the absence of bacteriophage (control, orange), bacteria grew steadily to high densities. In contrast, bacteriophage-infected cultures showed dose-independent inhibition of bacterial growth. Bacterial regrowth occurred after an initial inhibition phase, indicating partial control by the bacteriophage.

Figure 3.

Host range analysis of Salmonella phage SA01 across diverse clinical and environmental isolates. A circular phylogenetic tree was generated based on Salmonella strains, with susceptible isolates (red labels) indicating successful bacteriophage infection and resistant isolates showing no detectable lytic activity. The distribution of susceptible strains across multiple clades highlights the broad host range of SA01 within the Salmonella genus.

Figure 3.

Host range analysis of Salmonella phage SA01 across diverse clinical and environmental isolates. A circular phylogenetic tree was generated based on Salmonella strains, with susceptible isolates (red labels) indicating successful bacteriophage infection and resistant isolates showing no detectable lytic activity. The distribution of susceptible strains across multiple clades highlights the broad host range of SA01 within the Salmonella genus.

Figure 4.

Biological characterization of Salmonella phage SA01: One-step growth curve of Salmonella phage SA01 fitted with a 4-parameter logistic model. Titers (×107 PFU/mL) were measured at multiple time points during a one-step growth experiment and plotted on a logarithmic scale. The fitted curve reveals an early latent period followed by a sharp burst beginning at ~25–45 minutes and a plateau by ~50–70 minutes.

Figure 4.

Biological characterization of Salmonella phage SA01: One-step growth curve of Salmonella phage SA01 fitted with a 4-parameter logistic model. Titers (×107 PFU/mL) were measured at multiple time points during a one-step growth experiment and plotted on a logarithmic scale. The fitted curve reveals an early latent period followed by a sharp burst beginning at ~25–45 minutes and a plateau by ~50–70 minutes.

Figure 5.

Thermal and pH Stability Profiles of the Isolated Bacteriophage. (a) Thermal stability of the bacteriophage assessed over a temperature range from 4 °C to 80 °C. Relative stability was calculated as the percentage of residual bacteriophage activity compared to baseline (100%). The bacteriophage maintained full stability up to ~60 °C, after which a sharp decline in viability was observed; (b) pH stability of the bacteriophage across a range of pH 4–12. bacteriophage titers are expressed as a percentage of the maximum titer observed. The bacteriophage showed high stability in the neutral to slightly alkaline range (pH 6–9), with decreased viability under strongly acidic or alkaline conditions.

Figure 5.

Thermal and pH Stability Profiles of the Isolated Bacteriophage. (a) Thermal stability of the bacteriophage assessed over a temperature range from 4 °C to 80 °C. Relative stability was calculated as the percentage of residual bacteriophage activity compared to baseline (100%). The bacteriophage maintained full stability up to ~60 °C, after which a sharp decline in viability was observed; (b) pH stability of the bacteriophage across a range of pH 4–12. bacteriophage titers are expressed as a percentage of the maximum titer observed. The bacteriophage showed high stability in the neutral to slightly alkaline range (pH 6–9), with decreased viability under strongly acidic or alkaline conditions.

Figure 6.

(a)Thermal stability of four bacteriophages at 65 °C. Bacteriophage titers (PFU/mL, log scale) were monitored over a 5-hour incubation period. Among the tested bacteriophages, only SA01 (orange) retained infectivity throughout the assay, demonstrating remarkable thermostability. In contrast, AUBFM01 (blue), Miniara127 (green), and EPIMAM01 (yellow) showed rapid loss of activity, with complete inactivation within 2–3 hours. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (factors: bacteriophage and time), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Results confirmed a highly significant effect of both bacteriophage identity and incubation time (**p < 0.001), with SA01 showing statistically greater stability compared to all other bacteriophages across all time points; (b) Thermal inactivation kinetics of Salmonella phage SA01 at 70 °C. Decay of bacteriophage titers (PFU/mL, log scale) were determined at different time intervals over 4 hours at 70 °C. A linear regression model was fitted to the log-transformed data, revealing a steady decline in bacteriophage infectivity over time with an inactivation slope of ~−0.55 log10/h. The bacteriophage followed first-order thermal inactivation kinetics, with an average reduction time of ~1.8 h, indicating an exponential decay in titer that was independent of the initial concentration.

Figure 6.

(a)Thermal stability of four bacteriophages at 65 °C. Bacteriophage titers (PFU/mL, log scale) were monitored over a 5-hour incubation period. Among the tested bacteriophages, only SA01 (orange) retained infectivity throughout the assay, demonstrating remarkable thermostability. In contrast, AUBFM01 (blue), Miniara127 (green), and EPIMAM01 (yellow) showed rapid loss of activity, with complete inactivation within 2–3 hours. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (factors: bacteriophage and time), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Results confirmed a highly significant effect of both bacteriophage identity and incubation time (**p < 0.001), with SA01 showing statistically greater stability compared to all other bacteriophages across all time points; (b) Thermal inactivation kinetics of Salmonella phage SA01 at 70 °C. Decay of bacteriophage titers (PFU/mL, log scale) were determined at different time intervals over 4 hours at 70 °C. A linear regression model was fitted to the log-transformed data, revealing a steady decline in bacteriophage infectivity over time with an inactivation slope of ~−0.55 log10/h. The bacteriophage followed first-order thermal inactivation kinetics, with an average reduction time of ~1.8 h, indicating an exponential decay in titer that was independent of the initial concentration.

Figure 7.

Genomic features and phylogenetic analysis of Salmonella phage SA01. (a) Circular genome map of SA01 (43,416 bp) showing predicted open reading frames (ORFs) and their annotated functions; (b) Phylogenetic tree based on whole-genome nucleotide similarity, showing SA01 (red star) clustering within a group of closely related Salmonella bacteriophages. The tree includes 15 reference sequences retrieved from GenBank, and branch lengths indicate genetic distance; (c) Whole-genome alignment of SA01 against its closest relatives using viptree. Conserved locally collinear blocks (LCBs) are represented in colored blocks, highlighting overall genome synteny with evidence of rearrangements and unique regions distinguishing SA01.

Figure 7.

Genomic features and phylogenetic analysis of Salmonella phage SA01. (a) Circular genome map of SA01 (43,416 bp) showing predicted open reading frames (ORFs) and their annotated functions; (b) Phylogenetic tree based on whole-genome nucleotide similarity, showing SA01 (red star) clustering within a group of closely related Salmonella bacteriophages. The tree includes 15 reference sequences retrieved from GenBank, and branch lengths indicate genetic distance; (c) Whole-genome alignment of SA01 against its closest relatives using viptree. Conserved locally collinear blocks (LCBs) are represented in colored blocks, highlighting overall genome synteny with evidence of rearrangements and unique regions distinguishing SA01.