Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PMMA Coupons

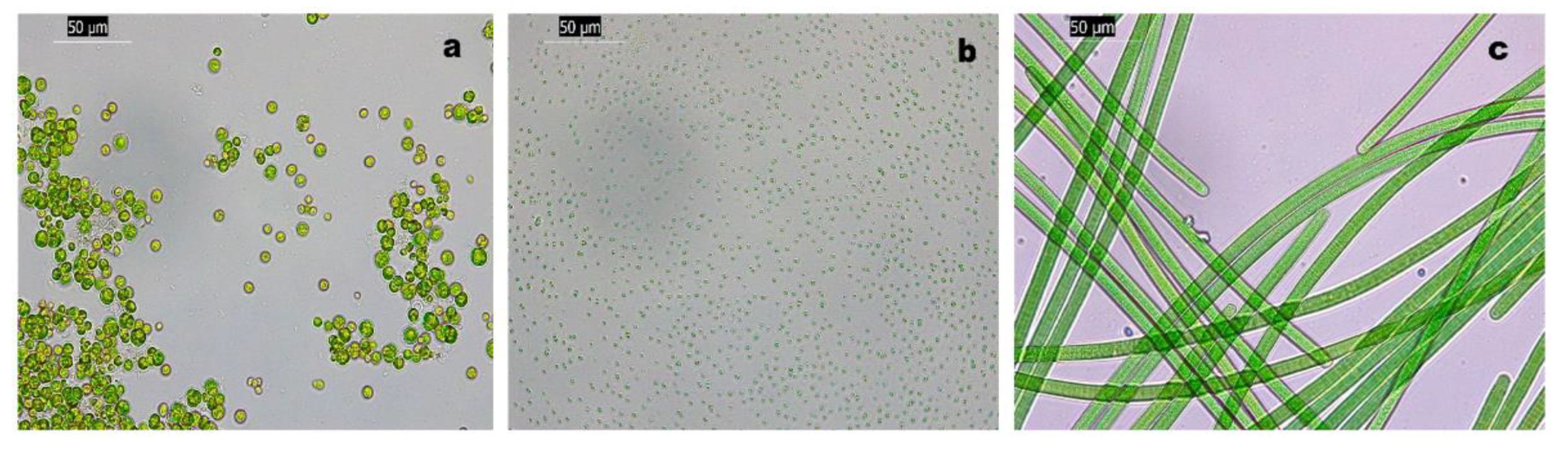

2.2. Photosynthetic Strains

2.3. Antifouling Assays

2.4. Tribological Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biomass Production

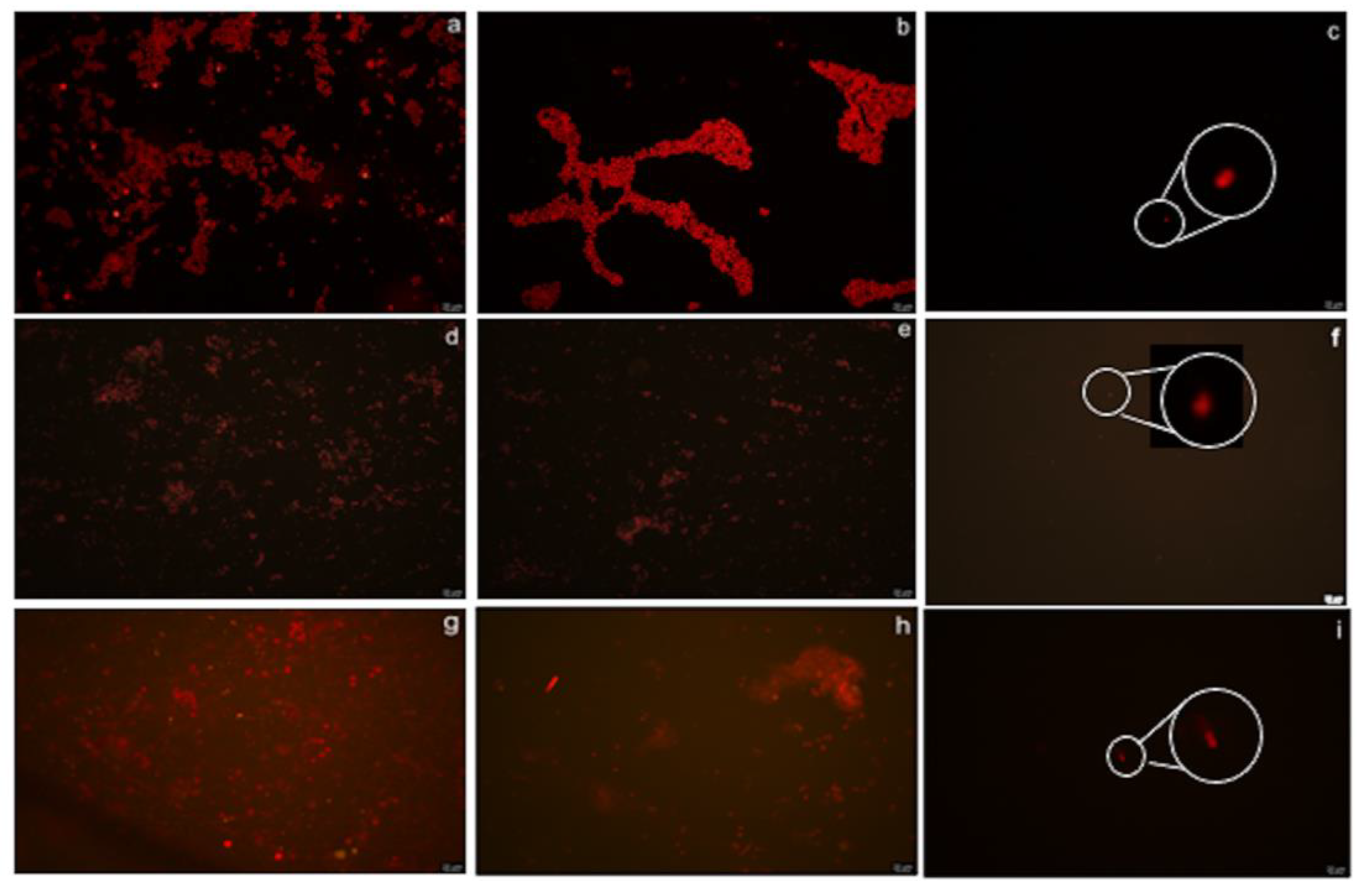

3.2. Antifouling Performance

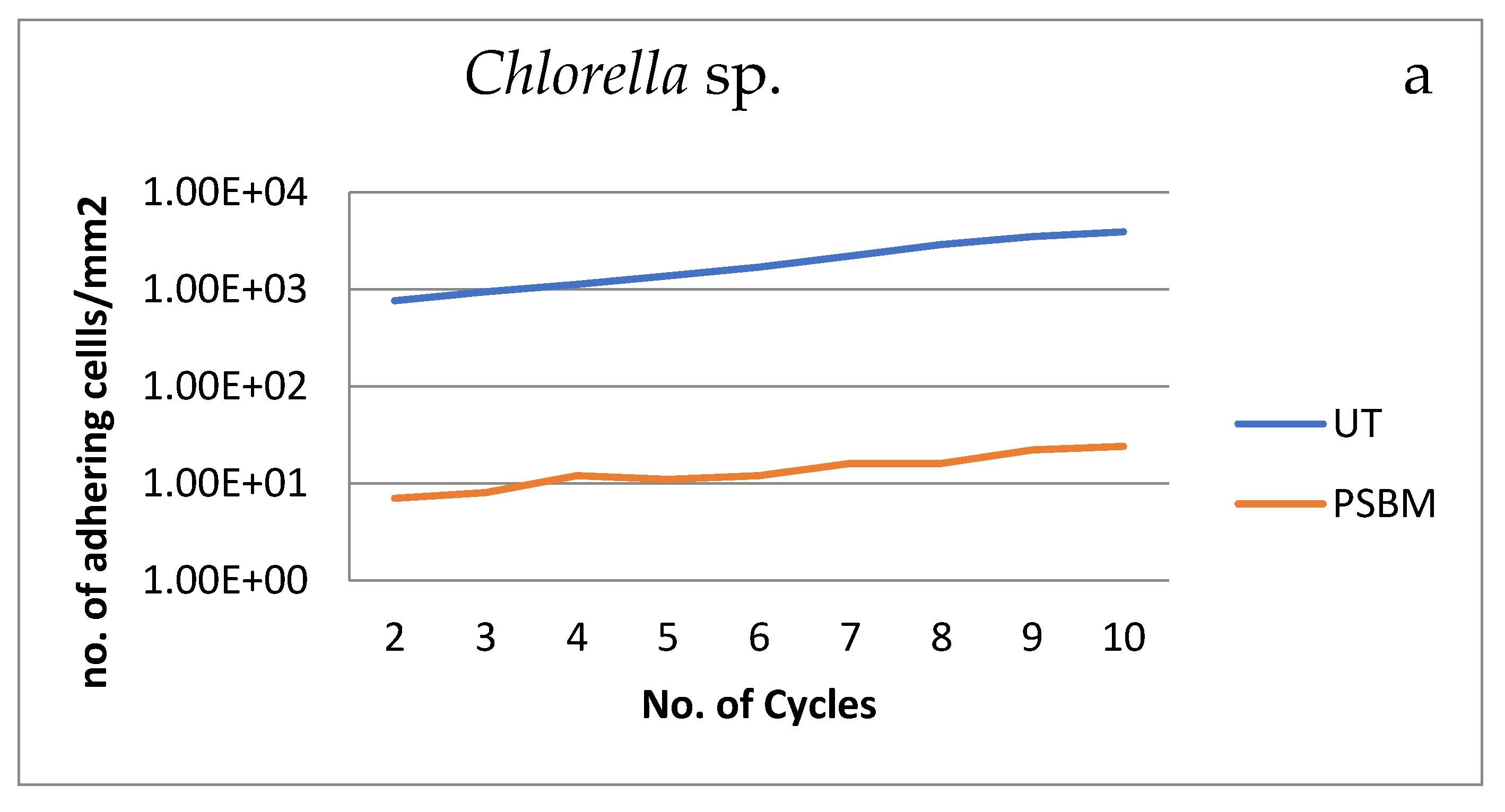

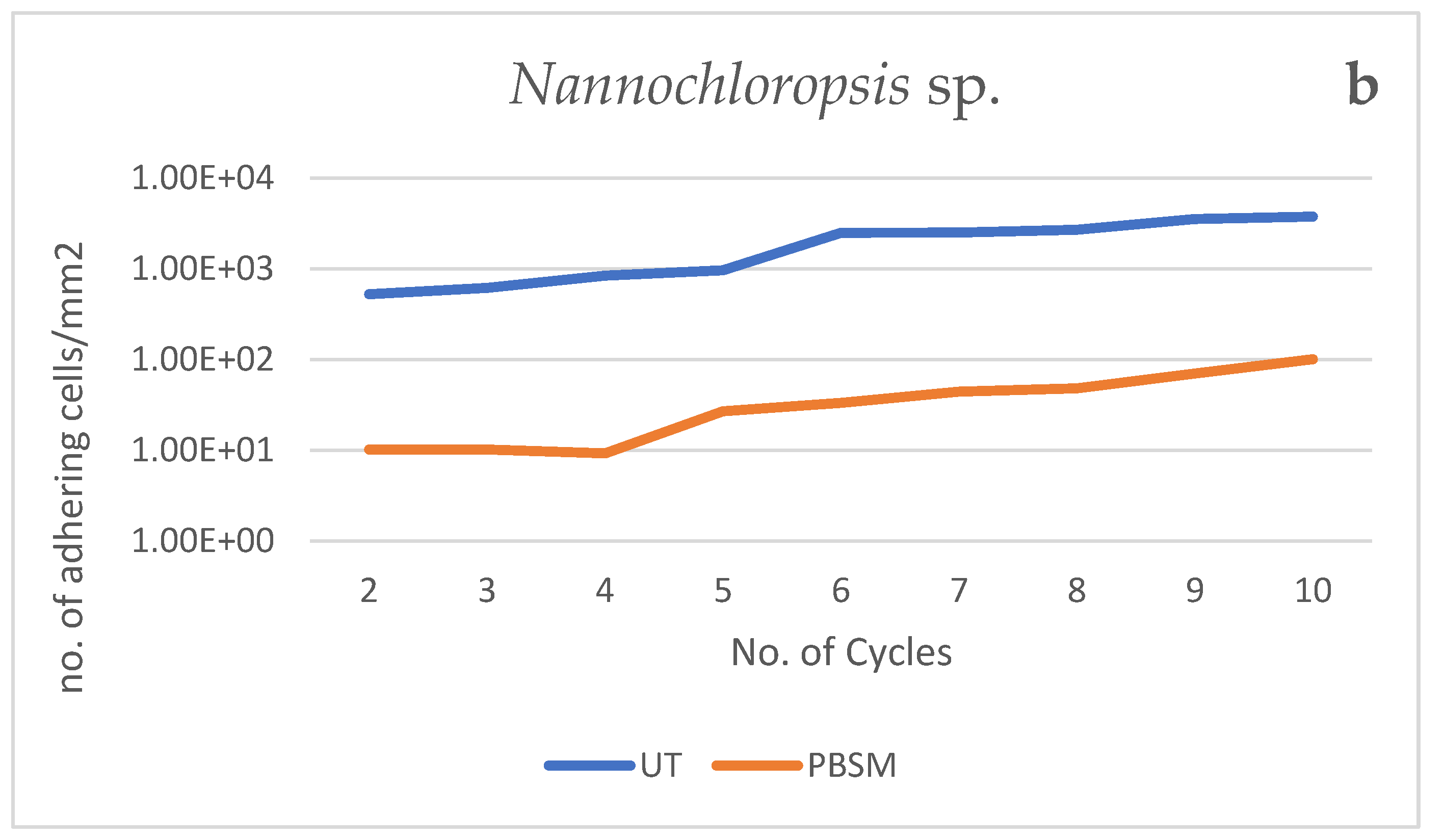

3.3. Long Term Effectiveness of the PSBM

3.3.1. Biomass Production over Cycles

3.3.2. Antifouling Performance of Strains Through Tribological Approach

4. Conclusions

- (a)

- mitigate the biofouling due to the three photosynthetic strains considered as model: Chlorella sp., Nannochloropsis sp. and A. maxima,

- (b)

- maintenance of optical transparency

- (c)

- surface protection against wear.

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMMA | Polymethylmethacrylate |

| PSBM | Poly sulfobetaine methacrylate / Zwitterionic Sulfobetaine-Hydroxyethyl containing-Polymethylmethacrylate ter-co-polymer |

| AF | Antifouling |

| UT | Untreated |

| R | Rough |

References

- Joy, S.R. , Anju, T.R. (2023). Microalgal Biomass: Introduction and Production Methods. In: Thomas, S., Hosur, M., Pasquini, D., Jose Chirayil, C. (eds) Handbook of Biomass. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, J.-F.; Kean-Meng, T.; Asencio-Alcudia, G.-G.; Asyraf-Kassim, M.; Alvarez-González, C.-A.; Márquez-Rocha, F.-J. Sustainable Microalgae and Cyanobacteria Biotechnology. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobin SM, A.; Chowdhury, H.; Alam, F. Commercially important bioproducts from microalgae and their current applications–A review. Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Mujtaba, G.; Memon, S.A.; Lee, K.; Rashid, N. Exploring the potential of microalgae for new biotechnology applications and beyond: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 92, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.D. The promising future of microalgae: current status, challenges, and optimization of a sustainable and renewable industry for biofuels, feed, and other products. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.N.; Onyejiaka, C.K.; Ihim, S.A.; Ayoka, T.O.; Aduba, C.C.; Ndukwe, J.K.; Nwaiwu, O.; Onyeaka, H. Bioactive compounds by microalgae and potentials for the management of some human disease conditions. AIMS Microbiol. 2023, 7, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, X. Enhancement of microalgae production by embedding hollow light guides to a flat-plate photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 207, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Bhatia, S.; Gupta, U.; Decker, E.; Tak, Y.; Bali, M.; Gupta, V.K.; Dar, R.A.; Bala, S. Microalgal bioactive metabolites as promising implements in nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals: inspiring therapy for health benefits. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 903–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanquia, S.N.; Vernet, G.; Kara, S. Photobioreactors for cultivation and synthesis: Specifications, challenges, and perspectives. Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 12, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Chen, Zhiwu Yu * 2024 Low-melting mixture solvents: extension of deep eutectic solvents and ionic liquids for broadening green solvents and green chemistry. Green Chemical Engineering Perspective. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Jerez, Y.; Macías-de la Rosa, A.; García-Abad, L.; López-Rosales, L.; Maza-Márquez, P.; García-Camacho, F.; Bressy, C.; Cerón-García, M.C.; Molina-Grima, E. Transparent antibiofouling coating to improve the efficiency of Nannochloropsis gaditana and Chlorella sorokiniana culture photobioreactors at the pilot-plant scale. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeriouh, O.; Reinoso-Moreno, J.V.; López-Rosales, L.; Cerón-García, M.C.; Sánchez-Mirón, A.; García-Camacho, F.; Molina-Grima, E. Biofouling in photobioreactors for marine microalgae. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2017, 37, 1006–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talluri, S.N.L.; Winter, R.M.; Salem, D.R. Conditioning film formation and its influence on the initial adhesion and biofilm formation by a cyanobacterium on photobioreactor materials. Biofouling 2020, 36, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damodaran, V.B.; Murthy, N.S. Bio-inspired strategies for designing antifouling biomaterials. Biomater. Res. 2016, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Abad, L.; López-Rosales, L.; Cerón-García, M.D.C.; Fernández-García, M.; García-Camacho, F.; Molina-Grima, E. Influence of abiotic conditions on the biofouling formation of flagellated microalgae culture. Biofouling 2022, 38, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magin, C.M.; Cooper, S.P.; Brennan, A.B. Non-toxic antifouling strategies. Materials Today 2010, 13, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, A.M.C.; Hofman, A.H.; de Vos, W.M.; Kamperman, M. Recent developments and practical feasibility of polymer-based antifouling coatings. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I.; Pangule, R.C.; Kane, R.S. Antifouling coatings: recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 690–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Jerez, Y.; López-Rosales, L.; Cerón-García, M.C.; Sánchez-Mirón, A.; Gallardo-Rodríguez, J.J.; García-Camacho, F.; Molina-Grima, E. Long-term biofouling formation mediated by extracellular proteins in Nannochloropsis gaditana microalga cultures at different medium N/P ratios. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucinska, E.; Zamojski, P.; Grodzki, W.; Blaszczak, U.; Zglobicka, I.; Zielinski, M.; Kurzydlowski, K.J. Degradation of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bioreactors used for algal cultivation. Materials 2023, 16, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, B.; Gao, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, T.; Su, G. Impacts of surface wettability and roughness of styrene-acrylic resin films on adhesion behavior of microalgae Chlorella sp. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 199, 111522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.Y.; Derek CJ, C. Membrane surface roughness promotes rapid initial cell adhesion and long-term microalgal biofilm stability. Environmental Research 2022, 206, 112602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeriouh; Ouassim; Reinoso-Moreno, J. V.; López-Rosales, L.; del Carmen Cerón-García, M.; Mirón, A.S.; García-Camacho, F.; Molina-Grima, E. Assessment of a photobioreactor-coupled modified Robbins device to compare the adhesion of Nannochloropsis gaditana on different materials. Algal Research 2019, 37, 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Guo, Z. The antifouling mechanism and application of bio-inspired superwetting surfaces with effective antifouling performance. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 325, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Sundaram, H.S.; Wei, Z.; Li, C.; Yuan, Z. Applications of zwitterionic polymers, reactive and functional polymers 2017, 118, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhuang, B.; Yu, J. Functional zwitterionic polymers on surface: structures and applications. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 2060–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, K.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Gong, X.; Zhao, Y.; Mu, Q.; Zhan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, L. Structures, properties, and applications of zwitterionic polymers. ChemPhysMater. 2022, 1, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Ren, B.; Huang, L.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, M.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J. Salt-responsive zwitterionic polymer brushes with anti-polyelectrolyte property. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2018, 19, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higaki, Y.; Nishida, J.; Takenaka, A.; Yoshimatsu, R.; Kobayash, M.; Takahara, A.A. Versatile inhibition of marine organism settlement by zwitterionic polymer brushes. Polym. 2015, 47, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, X.; Long, L.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, S.; Wen, S.; Yan, C.; Wange, J.; Cong, W. Improved antifouling properties of photobioreactors by surface grafted sulfobetaine polymers. Biofouling 2017, 33, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wen, S.; Yu, J.; Yan, C.; Cong, W. Improved antibiofouling properties of photobioreactor with amphiphilic sulfobetaine copolymer coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings 2020, 144, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhaia, S.; Wadhwa, A.S. Recent advances in bio-tribology from joint lubrication to medical implants: A review. Journal of Materials and Engineering 2024, 2, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simson, D. , & Subbu, S. K. (2024). Investigating the tribological performance of bioimplants. In Bioimplants Manufacturing (pp. 258–283). CRC Press. eBook ISBN 9781003509943.

- Prabhu, A.; Raghavan, S.; Kumar, S. Recent review of tribology, rheology of biodegradable and FDM compatible polymers. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 12345–12367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Song, Z.; Yang, X.; Song, Z.; Luo, X. Antifouling strategies for protecting bioelectronic devices. APL Materials 2021, 9, 020701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, J. , Rakić, D., & Vuković, M. Special issue: Tribological coatings—Properties, mechanisms, and applications in surface engineering. Materials 2023, 16, 1234–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Schiavo, S. , Gulino, A., Fragalà, M. E., Mineo, P., Nicosia, A., Ali, R. H.,... & Urzì, C. A sulfobetaine containing-polymethylmethacrylate surface coating as an excellent antifouling agent against Chlorella sp. Progress in Organic Coatings 2025, 199, 108940. [Google Scholar]

- Stanier, R.Y.; Kunisawa, R.; Mandel MC, B.G.; Cohen-Bazire, G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriological Reviews 1971, 35, 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, F.F.; Kamil, A.E.-W.; Nasr, H.S. Production and nutritive value of Spirulina platensis in reduced-cost media. The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research 2012, 38, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, A. , Gonçalves, A. L., Gomes, I. B., Simões, L. C., & Simões, M. (2015). Methods to study microbial adhesion on abiotic surfaces.

- Liao, Y.; Fatehi, P.; Liao, B. Microalgae cell adhesions on hydrophobic membrane substrates using quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2023, 230, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sapagh, S.; El-Shenody, R.; Pereira, L.; Elshobary, M. Unveiling the potential of algal extracts as promising antibacterial and antibiofilm agents against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vitro and in silico studies including molecular docking. Plants 2023, 12, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Ma, A. Advancing strategies of biofouling control in water-treated polymeric membranes. Polymers 2022, 14, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, L.F.; Berneira, L.M.; Poletti, T.; Mariotti KD, C.; Carreño, N.L.; Hartwig, C.A.; Pereira, C.M. Evaluation and characterization of algal biomass applied to the development of fingermarks on glass surfaces. Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 2021, 53, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Gao, K.; Zhou, L.; Jiao, Z.; Wu, M.; Cao, J.; You, X.; Cai, Z.; Su, Y.; Jiang, Z. Zwitterionic materials for antifouling membrane surface construction. Acta Biomaterialia 2016, 40, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.; Agirre, A.; Arrizabalaga, J.; Rafaniello, I.; Schäfer, T.; Tomovska, R. Zwitterionic stabilized water-borne polymer colloids for antifouling coatings. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2024, 196, 105843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.Z. Surface coatings in tribological and wear-resistant applications. International Heat Treatment and Surface Engineering 2009, 3, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, S.P.; Hu, X.; Fleming, P.; Forrester, S. Tribological investigation into achieving skin-friendly artificial turf surfaces. Materials & Design 2016, 89, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, M.; Kamps, T.; Woolliams, P.; Nunn, J.; Mingard, K. In situ real-time observation of tribological behaviour of coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2022, 442, 128233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

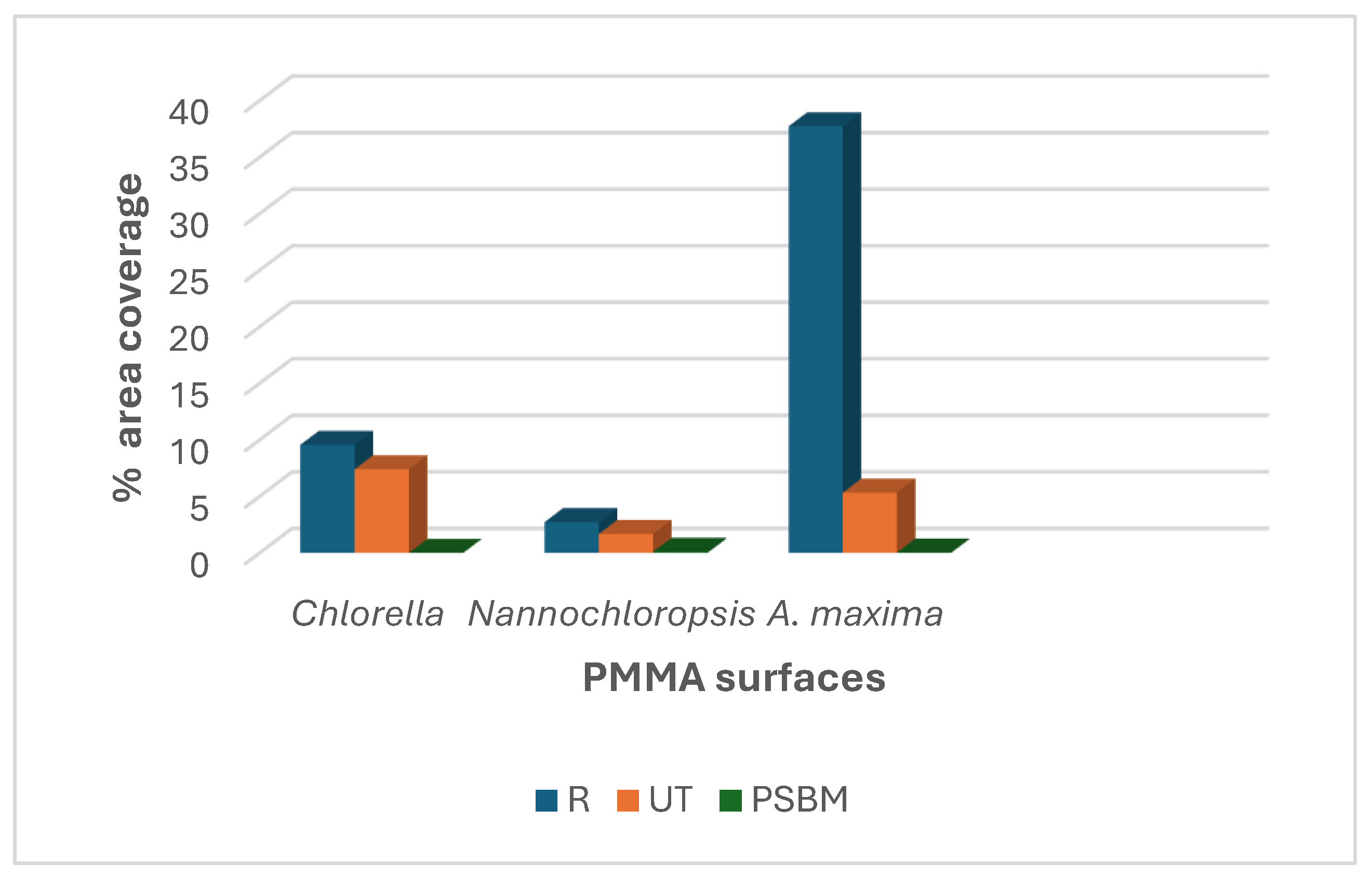

| Strains | Average cells/mm2 | % Area coverage/mm2 | ||||

| R | UT | PSBM | R | UT | PSBM | |

| Chlorella | 4500 | 3705 | 2 | 9 | 7,5 | 0.004 |

| Nannochloropsis | 6063 | 4044 | 222 | 3 | 2 | 0.1 |

| A. maxima | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 37,72 | 5,33 | 0.037 |

| UT | PSBM | |||

| Cell/mm2 | ||||

| No.Cycles | Chlorella | Nannochloropsis | Chlorella | Nannochloropsis |

| 2 | 763 | 525.93 | 7 | 10.19 |

| 3 | 970 | 618.52 | 8 | 10.19 |

| 4 | 1118 | 840.74 | 12 | 9.26 |

| 5 | 1370 | 963.89 | 11 | 26.85 |

| 6 | 1677 | 2495.37 | 12 | 33.33 |

| 7 | 2196 | 2515.74 | 16 | 44.42 |

| 8 | 2885 | 2700.93 | 16 | 48.15 |

| 9 | 3481 | 3554.57 | 22 | 70.37 |

| 10 | 3861 | 3768.52 | 23 | 100.93 |

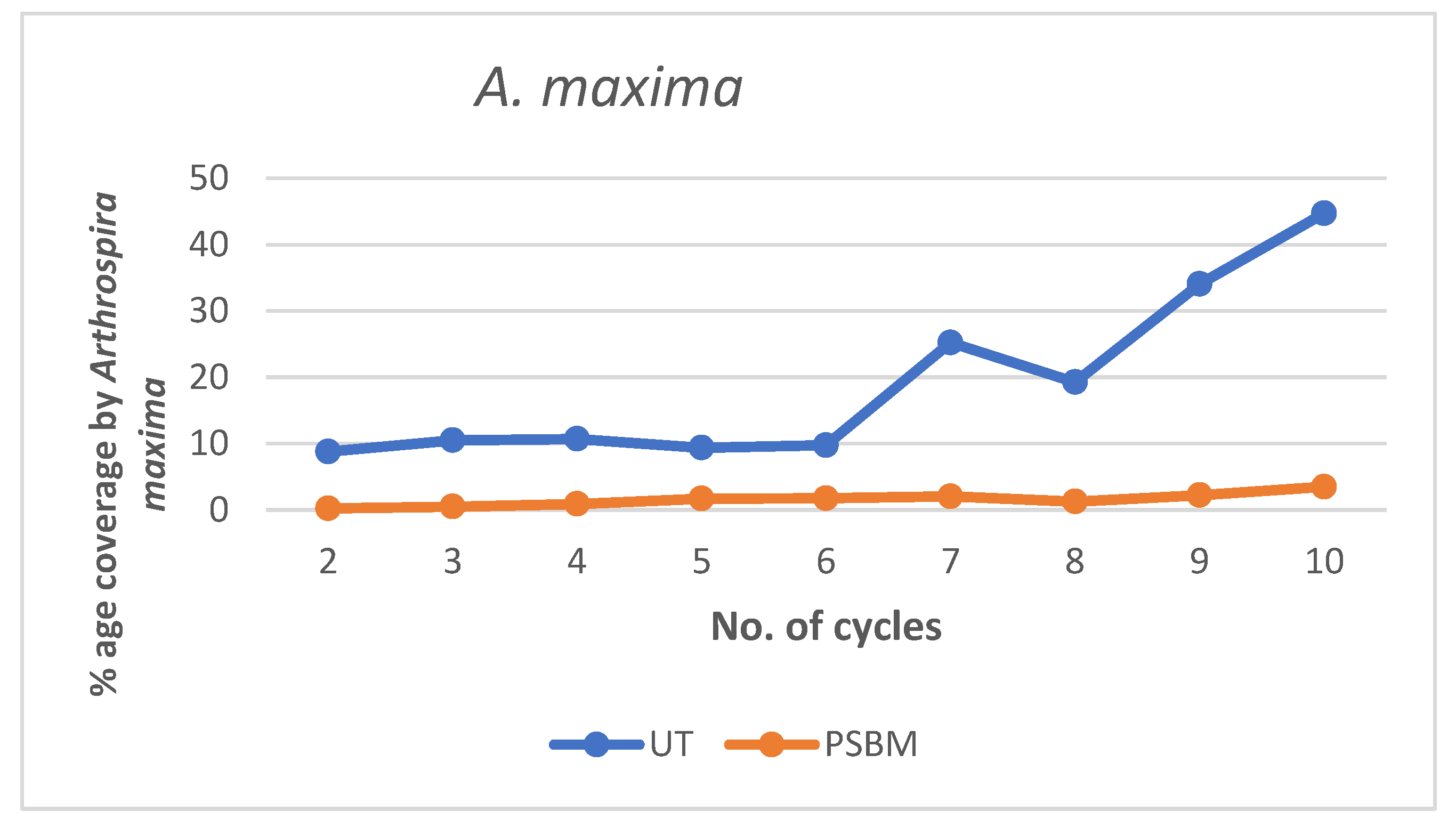

| Chlorella | Nannochloropsis | A. maxima | ||||

| No. cycles | UT | PSBM | UT | PSBM | UT | PSBM |

| 2 | 1.52 | 0.014 | 0.17 | 0.0032 | 8.78 | 0.218 |

| 3 | 1.94 | 0.016 | 0.19 | 0.0032 | 10.48 | 0.489 |

| 4 | 2.23 | 0.024 | 0.26 | 0.0029 | 10.68 | 0.885 |

| 5 | 2.74 | 0.026 | 0.30 | 0.0084 | 9.37 | 1.685 |

| 6 | 3.35 | 0.024 | 0.78 | 0.0105 | 9.74 | 1.244 |

| 7 | 4.39 | 0.032 | 0.79 | 0.0140 | 25.22 | 2.026 |

| 8 | 5.77 | 0.032 | 0.85 | 0.0151 | 19.26 | 1.752 |

| 9 | 6.69 | 0.044 | 1.11 | 0.0221 | 34.04 | 2.204 |

| 10 | 7.72 | 0.046 | 1.18 | 0.0317 | 44.70 | 3.481 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).