1. Introduction

The United Nations General Assembly set a goal for sustainable development in 2015 to fight against hunger, which includes ensuring food security [

1,

2]. However, one of the major problems that threaten food safety is the formation of biofilms and the spread of pathogenic bacteria in the premises for the production and storage of food products, as well as on equipment for its transportation [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Biocide coatings are coatings that are designed to inhibit the growth of or kill bacteria microorganisms [

8,

9]. The use of biocide coatings on food contact surfaces, equipment, and packaging is an effective way to prevent the growth and spread of harmful microorganisms [

8]. These coatings contain antimicrobial agents, such as silver ions, organic antibiotics like chlorohexidine etc which work by attacking the cell walls of microorganisms and preventing their growth [

8,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Biocide coatings have been shown to be effective against a wide range of foodborne pathogens, including Salmonella, Listeria, and Escherichia coli [

14,

15]. Overall, the use of biocide coatings in the food industry is an effective and important measure to reduce the risk of foodborne infections. It can help protect the health and well-being of consumers and also reduce the economic impact of foodborne illnesses.

Although processing of production shops with formulations based on low molecular weight antibiotics is a common practice, it may not always lead to the desired result due to the low adhesion of the biocides to the surfaces being treated, and the rapid development of bacterial resistance [

16,

17]. Therefore, there is a need for a new affordable and cheap antibacterial compositions that can be effectively used in food factories and shops. To tackle this issue, polymers have been used as new antibacterial functional coatings. In general, polymers are usually the matrix for low molecular weight biocides, which provide durability but do not have an antibacterial effect by themselves [

18,

19]. Specific class of polymers that have a potential to be used as biocide coatings is so called biocide polymers- macromolecules with functional groups that provide antibacterial action in each monomer unit [

20,

21,

22]. Among this class of polymers, polycations are of particular interest. Polymers with quaternized amino-groups were reported to be effective non-specific biocides with serious benefit in compare to conventional low molecular weight antibacterial agents. Polycations do not cause development of induced tolerance of the bacteria and give no rise to mutant species [

23]. Among commercially available polycations polydiallyldimethylammonium chloride (PDADMAC) is of great potential [

24,

25]. Notable advantage of using PDADMAC as a biocide is its relatively low toxicity to humans and the environment. Quaternized polyethyleneimine (q-PEI) is the product of alkylation of wide spread polymer - polyetheleneimine (PEI) was also admitted as effective biocide [

26]. These both polymers are completely charged in wide range of pH that supports their high antibacterial activity independent on the pH of surrounding media. Nevertheless the initial PEI with primary and ternary aminogroups was also reported to demonstrate antimicrobial activity [

27,

28]. The mechanism of the biocide action of the polycations is still under discussion. The antibacterial activity of polycations is primarily due to their ability to disrupt the bacterial cell membrane and cause cell death [

29]. Polycations are believed to interact with bacterial membranes through electrostatic interactions, forming a complex with the bacterial cell wall or membrane, leading to membrane destabilization. Once the bacterial membrane is disrupted, polycations can enter the bacterial cell and bind to intracellular molecules such as DNA and proteins, leading to further cell damage and eventually cell death.

PEI and PDADMAC have been shown to be effective against a range of bacterial pathogens including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacillus subtilis. They have also been found to be effective against antibiotic-resistant strains of these bacteria.

Overall, the antibacterial activity of PDADMAC and PEI makes them promising candidates for use in a variety of applications including food processing and packaging.

The average molecular weight and molecular weight distributions of polymers are key parameters that determine the physical and mechanical properties of the materials, so the molecular weight of the polymer used in the coatings is an important factor that can affect the antibacterial and physicochemical properties of the coatings [

30,

31,

32]. Commercial samples of PEI and PDADMAC, in particular, have broad polydispersity due to the polymerization process used to manufacture them. Additional control of the molecular weights and their distribution can be achieved using more precise and controlled polymerization procedures [

33]. However, this can complicate the process of obtaining PDADMAC on an industrial scale and make it less commercially available.

Therefore, the key task is to establish the role of the molecular weight of polycations to determine the optimal degrees of polymerization required to create stable and effective antibacterial coatings. In the first part of this paper, we focus on exploring of the main properties of coatings based on PDADMAC and PEI with different molecular weights and make a recommendation on the choice of the degree of polymerization for creating stable coatings. The second part is dedicated to the study of the biocide efficiency against foodborne Gram-positive bacteria of the coatings from the optimal samples of the polycations.

2.1. Materials

The samples of polyethyleneimine (PEI) with weight average molecular mass Mw= 750 kDA (PEI-750); Mw = 70 kDa (PEI-70); Mw = 40 kDa (PEI-40); Mw = 25 kDa (PEI-25); Mw = 3 kDA (PEI – 3) M w = 1.3 kDa (PEI-1.3) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as received without additional purification. The three samples of polydiallyldimethylammonium chloride (PDADMAC) with weight average molecular mass Mw = 500 kDa (PDADMAC-500), Mw = 300 kDa (PDADMAC-300) and Mw < 100 kDa (PDADMAC-100) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as received without additional purification. Structure formulas of polycations are presented on

Figure 1.

To study the interaction of coatings with model bacteria particles the biomimetic lipid membranes were prepared by the procedure described elsewhere [

34]. Briefly, 2 microns latex microspheres were covered with lipid bilayer composed of mixture of anionic and electroneutral lipids to simulate anionic cell surface of the bacteria. Thus, the latexes with supported lipid membrane were obtained.

Glass cover slips with an area of 3.24 cm2 were used in the experiments on washing-off polymeric coatings. Glass slides with an area of 19.76 cm2 were used to study the moisture saturation and adhesive properties of films. Before all the experiments, glass substrates were subjected to the sample preparation stage. Cleaning and degreasing of glass surfaces were carried out as follows: the substrate was dipped in methanol and vigorously shaken for a minute. After that, the glass substrate was activated: the coverslip was treated with 1 M KOH solution, then washed with bidistilled water and dried in an air atmosphere. Bidistilled water with a conductivity of 0.05 μS/cm was used in all the experiments.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

The diffusion coefficients for the polycations were obtained by dynamic light-scattering measurements were carried using a Complex laser light goniometer by Photocor Instruments (Moscow, Russia) equipped with a He−Ne laser and data processing was performed using DynaLS software version 2.7.1 [

24].

2.2.2. Polycation Coatings Wash-Off Procedure.

The freshly cleaned substrate (square glass cover slip) with 3.24 cm2 area was weighed. The 200 μL aliquot of the 20 mg/mL polymer solution was applied to the substrate so that the entire glass surface was covered with the solution. The sample was left to dry overnight in air atmosphere. The prepared sample was once again weighed and the mass of the film was calculated as the difference between the masses of substrate with film and substrate without the coating. Each cycle of wash-off was as follows: 200 μL of water was applied to the glass with coating, so that it completely covered the surface of the film. After two minutes of incubation the liquid was removed and the sample was left to dry. The sample was weighed and the mass loss was calculated. The experiments were carried out at a relative humidity of 15%–20%.

2.2.3. Polycation Coatings Moisture Saturation Analysis.

Freshly cleaned substrate (glass slide) with 19.76 cm2 area was weighed. The 1220 μL aliquot of the 20 mg/mL solution of polymer was applied to the substrate so that all the area was covered with the solution. The sample was left to dry overnight in an oven with 5% relative humidity. The prepared sample was weighed again, the mass of the film was calculated as the difference between the masses of substrate with film and the substrate without coating, and this value was used as a reference. Then the samples were kept for a day in a chamber in which a certain relative humidity was maintained. After that, the samples were weighed again. In total, several intervals of relative humidity values were obtained: 5–6%, 13%, 19%, 41–44%, 61%, 68%, 88–90% (to set the humidity in chamber the saturated solutions of simple salts were used). The weight gain of the coating after incubation in a controlled humidity environment was used to evaluate the ability of the polymer coating to absorb water from the air. The control of the humidity was performed using ASTM standardized Temperature and Humidity Datalogger DT-172 by CEM Test Instrument (Moscow, Russia).

In addition to gravimetry, the moisture content of the samples was controlled by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using synchronous thermal analysis instrument STA 449 F3 Jupiter by Netzsch (Selb, Germany). Lyophilized samples of PDADMAC100, PDADMAC-300 and PDADMAC-500 were used for the experiment, the sample weighed was 1–5 mg. The heating rate was 10 K/min. The sample was heated in a controlled atmosphere chamber (relative humidity 40 %) and the change in mass was simultaneously recorded [

35]. The thermal analysis was performed using the equipment purchased in the scope of the Program for Development of Lomonosov Moscow State University.

The gravimetry analyses were made using precise balances VLA-120 M by Gosmetr (Saint Petersburg, Russia).

2.2.4. Polycation Coatings Adhesive Properties Analysis.

Freshly cleaned substrate (glass slide) with 19.76 cm2 area was weighed. The aliquot of the 20 mg/mL polymer solution was applied to the substrate so that the entire surface was covered with the solution. Two minutes later, the polymer solution was removed and the substrate was washed with bidistilled water. Then, the glass slide was covered from above with previously cleaned glass and dried for 24 h. After drying, the adhesive properties of the polycations were evaluated by the stress required to separate the two glass substrates. The experiments were carried out at room temperature and relative humidity of 15%–20%. The adhesive properties were evaluated by dynamometry on a tensile testing machine by Metrotest (Moscow, Russia). The experiments were carried out at constant rate of the traverse 5 mm/min. The resulted data was collected using the software supplied by manufacturer.

2.2.5. Estimation of antibacterial action of Polycations.

The estimation of MIC values was made for Gram-positive bacteria

B. subtilis in in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) medium that is favorable for biofilm formation. The MICs in TSB medium were determined using a broth microdilution assay [

36]. The cell concentration was adjusted to approximately 5 × 10

5 cells/mL. The solutions of polycations with an initial concentration of 20 mg/mL were used as the test compound. The polycations solutions were serially diluted two-fold in a 96-well microplate (100 µl per well). The microplates were covered and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. The OD600 of each well was measured, and the MIC was assigned as the lowest concentration of the tested compound that resulted in no growth after 16–20 h. Bacterial cell growth was measured at 590 nm using a microplate reader (VICTOR X5 Light Plate Reader, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

For the cytometric experiments, Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria were stained using LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability and Counting Kit (Thermo, USA). 987 µL of 0.9 wt% aqueous sodium chloride solution was mixed with 1.5 µL of a ready-made SYTO 9 solution, 1.5 µL of a ready-made propidium iodide solution and 10 µL of the bacterial culture. The mixture was thoroughly stirred and incubated in light-protective Eppendorf tubes for 15 minutes. Quantification of live and dead cell populations was done with a Guava EasyCyte flow cytometer (Merk Millipore, Germany), while living cells turned green and dead cells turned red.

For the microbiological assessment of bacterial survival in solution, the daily broth cell culture was diluted 100 times with a nutrient medium, and the polymers were added at a 1:1 ratio. The mixtures were incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C, then diluted 10 times with sterile distilled water and used for determination of colony-forming units (CFU) using a standard protocol. Bacterial samples without polymers were used as controls.

In order to prepare polymer films, glass slides were washed successively with potassium bichromate/sulfuric acid mixture, potassium hydroxide/methanol mixture and bidistilled water and finally was air fried at RT. Then 200 μL of a 2 wt% aqueous cationic polymer solution was applied to a freshly cleaned glass slide; the sample was air dried at RT that resulted in a polymer film with a thickness of 0.15 mm. The glasses with deposited polymer films were put into the broth cell culture and incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C. After that the glasses were washed three times with distilled water and transferred to test tubes with saline solution and shaken intensively. In the resulting washes, CFU were determined using a standard protocol.

2.2.6. Measurements of Morphology of coatings

Atomic-force microscopy (AFM) imaging was performed using a scanning probe microscope Nanoscope IIIa (Nanoscope, USA) operating in a tapping mode in air. Cantilevers from silicon with resonance frequencies were of 140-150 KHz from TipsNano (Estonia) were used. A 15 mm x 15 mm cover glass was put in a 1 wt% polycation solution for 5 minutes. After that, the glass was transferred in DI water and rinsed for 1 minute that resulted in a removal of a polymer excess, and the sample was left to dry in air.

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was defined as the lowest concentration of each of the tested polymers that results in the destruction of 99.9% of the tested bacteria [

37].

In the statistical analyses, the average results of at least five experiments are presented as mean values.

3. Results

3.1. Samples characterization

The diffusion coefficients of the samples of PDADMAC and PEI were studied by means of DLS. The dependences of the diffusion coefficients (D) of polycations upon their concentration were measured in 0.15 M of NaCl solution in Tris buffer with pH 7 to avoid a polyelectrolyte swelling effect. Extrapolation of the concentration dependences of D to zero concentration allowed us to estimate the resulting D

0 values, which are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of Polycations

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) (the minimum concentration of polycations of different molecular weights at which bacterial growth of

B.subtilis is completely inhibited) was measured for several samples for brief screening . The results are presented in

Table 2. It has been established that the polycations of the presented degrees of polymerization exhibit the same antibacterial activity. No difference in biocidal activity between PEI and PDADMAC was observed.

3.3. Estimation of Moisture Saturation of Coatings

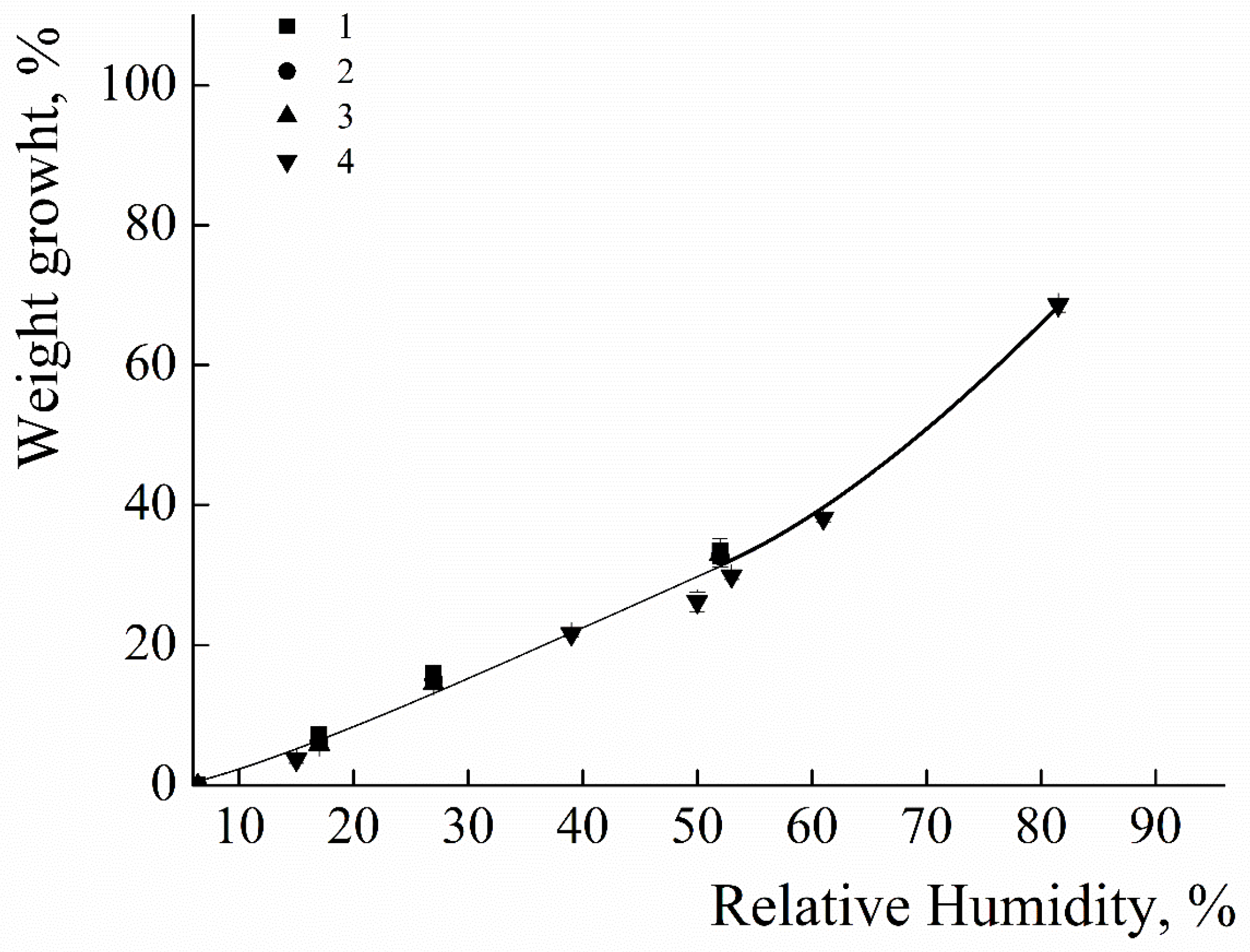

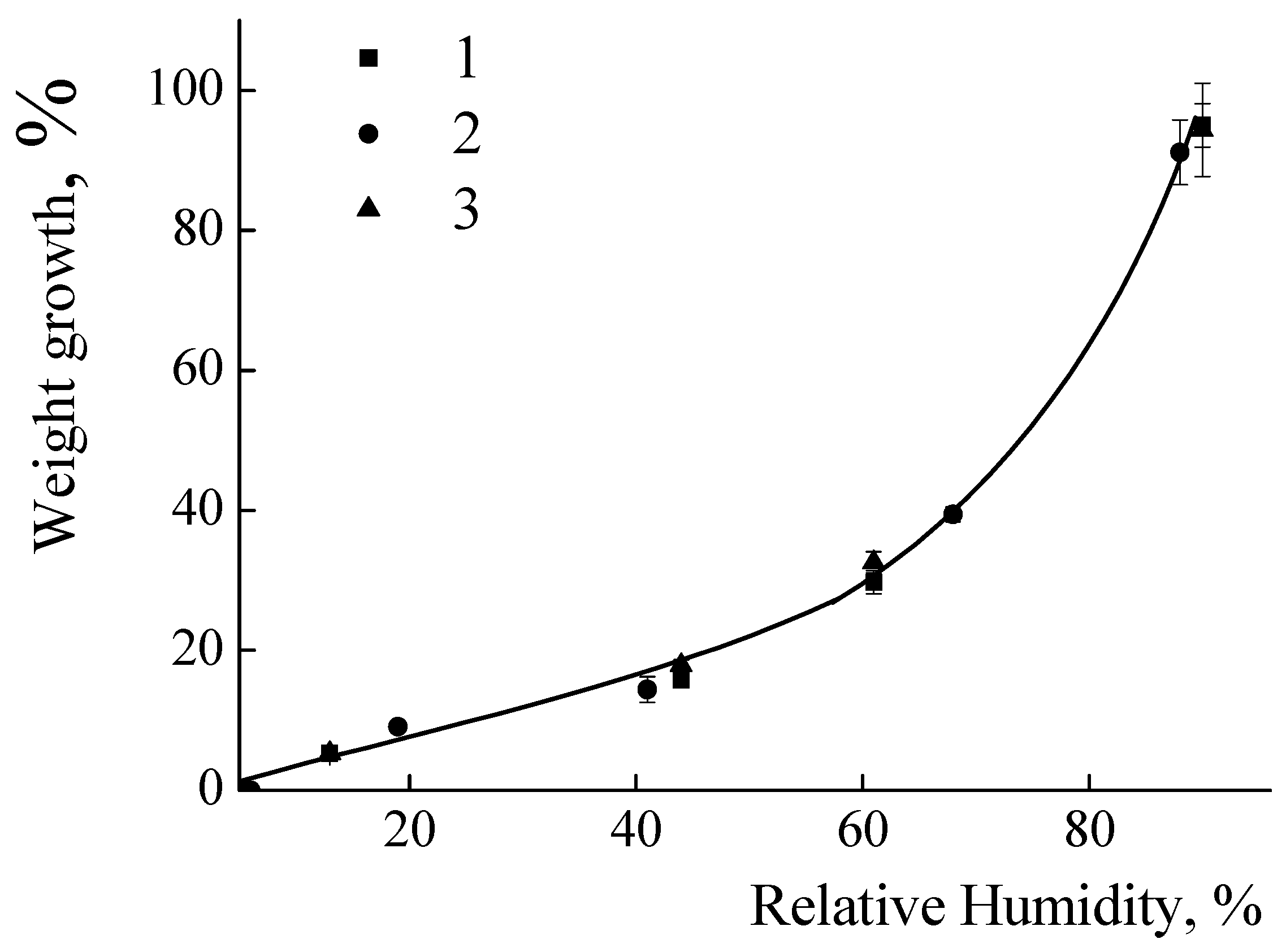

The ability of the polycationic coatings to absorb water from the surrounding environment was tested. The results for PEI and PDADMAC coatings are presented in Figure 2 as dependence of the relative growth of the weights of the films upon the relative humidity of the environment. For the PEI coatings an increase in humidity from 15% to 60% leads to a gradual increase in the weight of the coating from 3% to 35% (see Figure 2a). No influence of the molecular weight of the PEI molecules upon the ability of the films to absorb water was detected - the curves completely coincided for the all PEI samples. The similar dependences were observed for coatings made from PDADMAC. It has been established that an increase in humidity from 15% to 70% leads to a gradual increase in the weight of the coating from 5% to 40% (see Figure 2b). No influence of the molecular weight of the PDADMACs upon the ability of the films to absorb water was detected - the curves completely coincided for the PDADMAC-100, PDADMAC-300 and PDADMAC-500. It is important to stress that the polymer films adsorbed on the glass surfaces did not change their visually observed shapes during the experiment at the values of humidity less than 65%. Further increase of the humidity resulted in formation of water droplets on the film surfaces.

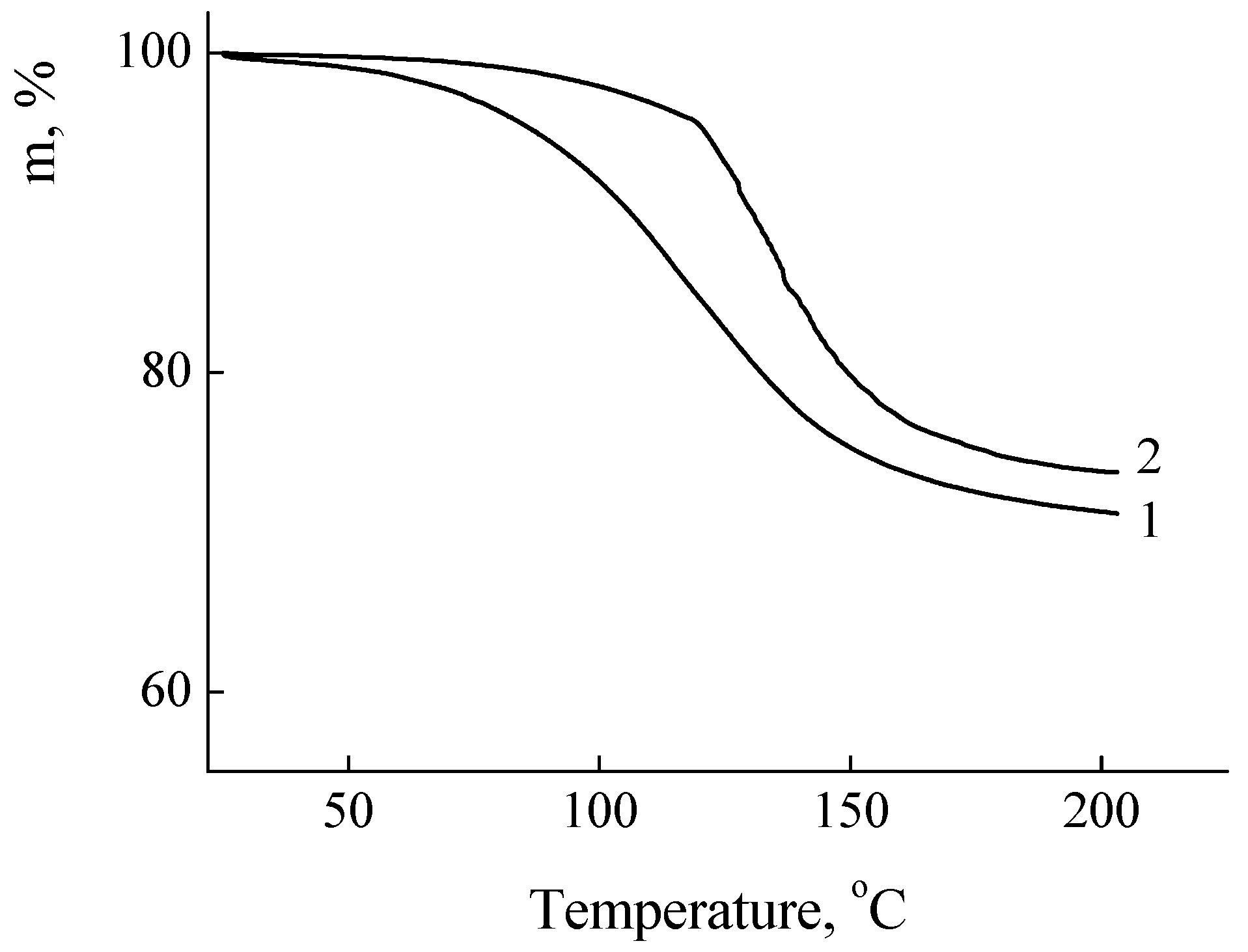

The saturation of the polycationic films with water was controlled by TGA in atmosphere with relative humidity 40%. The TGA curves of lyophilized samples of PDADMAC-500 and PEI-750 are presented on the

Figure 3. The samples weight loss corresponding to the loss of absorbed water was in interval 26-28% of their initial weight.

Figure 2.

a. Relative mass of the films of PEI upon the environmental humidity. PEI-1.3 (1); PEI-25 (2); PEI-70 (3); PEI-750 (4);.

Figure 2.

a. Relative mass of the films of PEI upon the environmental humidity. PEI-1.3 (1); PEI-25 (2); PEI-70 (3); PEI-750 (4);.

Figure 2.

b. Relative mass of the films of PDADMAC upon the environmental humidity. PDADMAC-100 (1); PDADMAC-300 (2); PDADMAC-500 (3).

Figure 2.

b. Relative mass of the films of PDADMAC upon the environmental humidity. PDADMAC-100 (1); PDADMAC-300 (2); PDADMAC-500 (3).

Figure 3.

TGA curves of polycation powders. PDADMAC-500 (1); PEI-750 (2), scanning rate 200 K/min; relative humidity of the environment 40%.

Figure 3.

TGA curves of polycation powders. PDADMAC-500 (1); PEI-750 (2), scanning rate 200 K/min; relative humidity of the environment 40%.

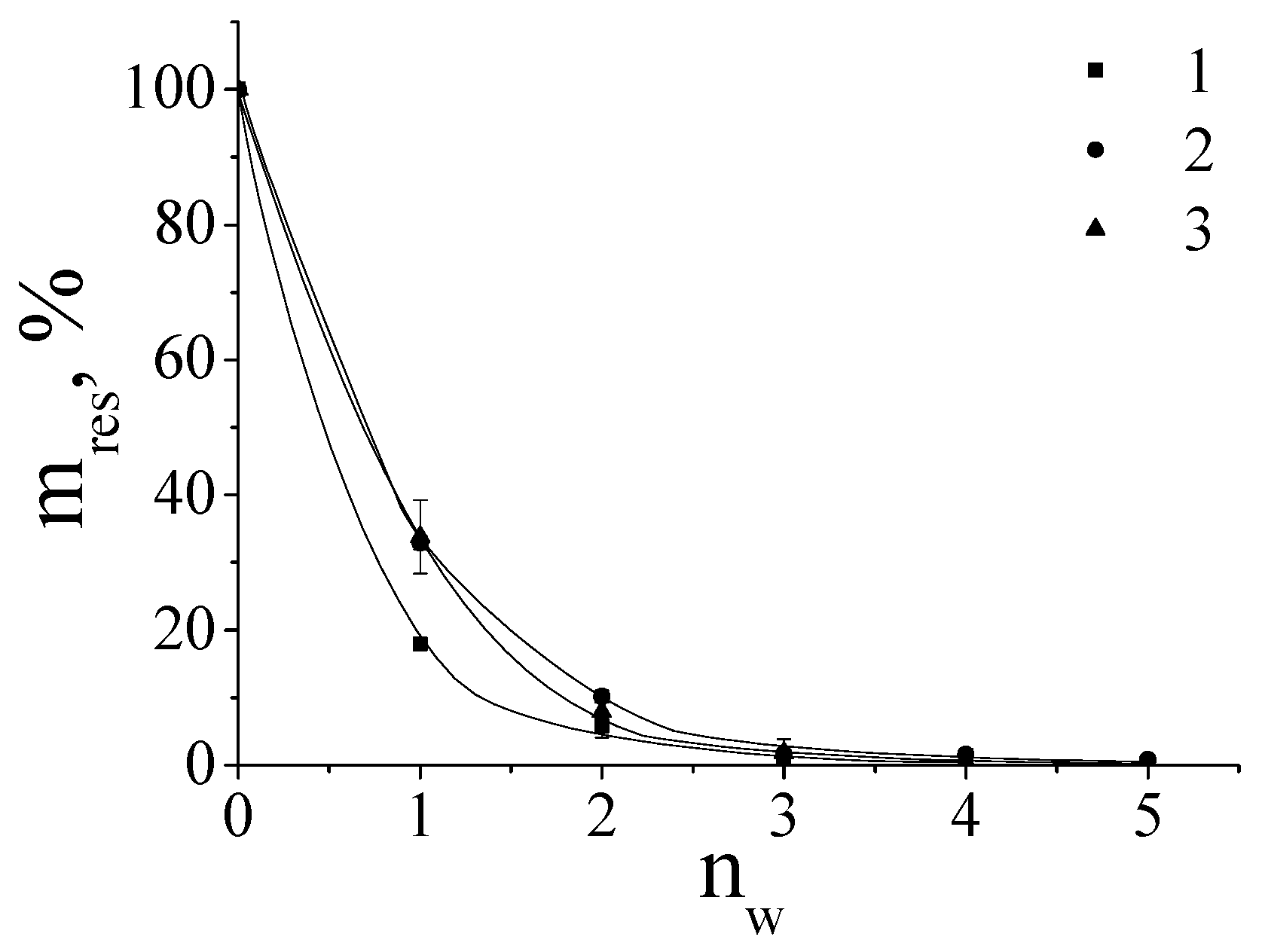

3.4. Wash-Off Resistance Study

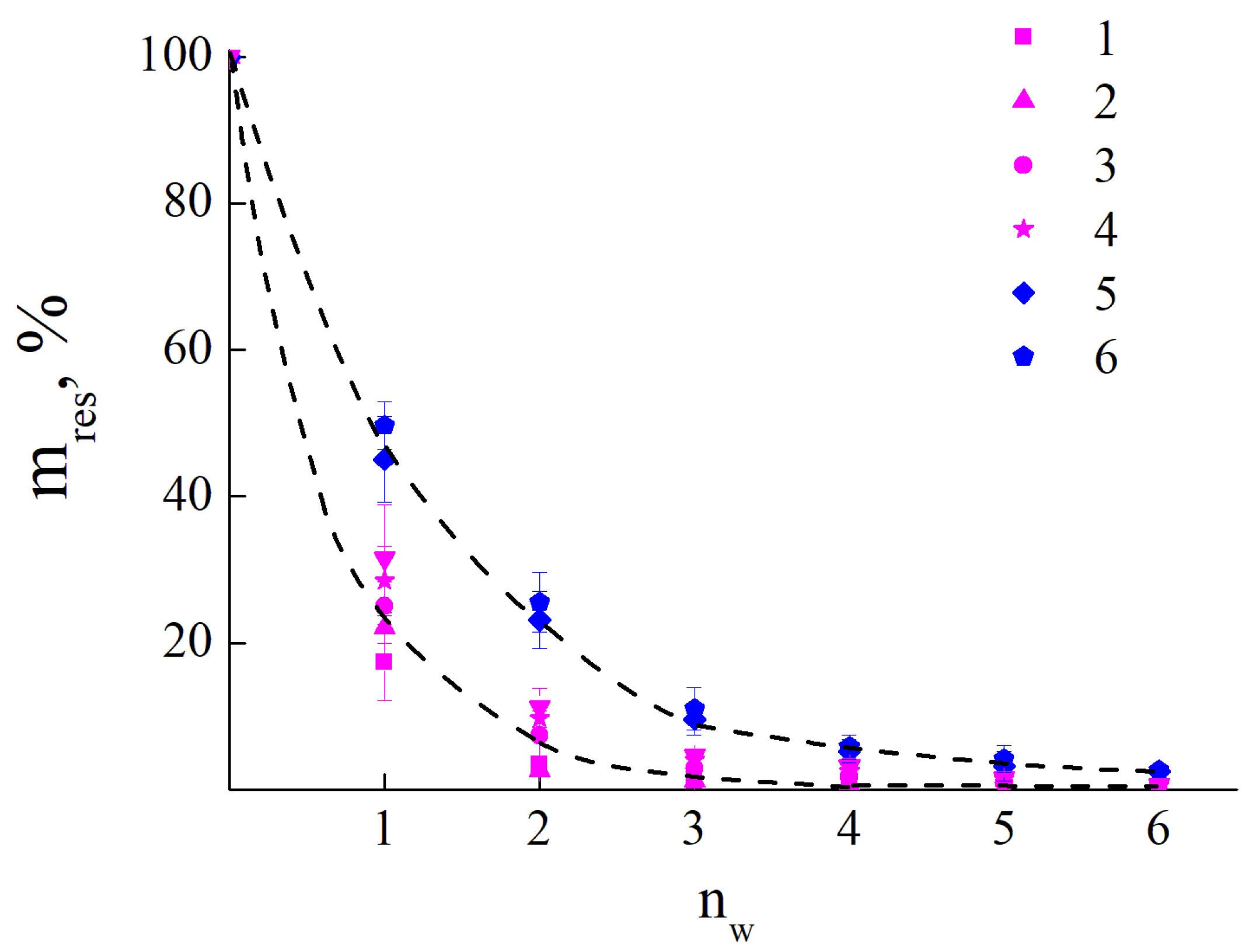

The resistance of the polymer films towards wash-off with water was controlled by the weight loss of the sample. The results are presented in Figure 4 as the dependences of the residual mass of the film upon the number of the wash-off cycle. For PEI-750 and PEI-70 the about 50% of weight loss was observed after the first wash-off cycle while for the samples of PEI-40, PEI-25, PEI-3 and PEI-1.3 the observed weigh loss was from 72% to 83% corresponding decrease of molecular weight (see Figure 4a). With the increase of the number of wash-off cycles the straight tendency could be observed- coatings from PEI with high molecular weight- PEI-70 and PEI-750- have similar high tolerance towards wash-off. While for the molecules with weights of PEI-40 and lower the process of the film weight loss goes faster with lowering of the number of cationic units in macromolecule. Almost all PEI coatings were removed after six cycles of the wash-off. The alike behavior of the coatings was observed for PDADMAC molecules (see Figure 4b). For PDADMAC-500 and PDADMAC-300, about 65% of weight loss was observed after the first wash-off cycle and almost all of the polycation was removed after four cycles of the wash-off. At the same time, PDADMAC100 lost about 80% of its coating mass after the first wash-off cycle.

Figure 4.

a. Dependence of the percentage of residual mass of coatings (mres) formed from PEI on the number of wash-off cycles (nw); PEI-1.3 (1); PEI-3 (2); PEI-25 (3); PEI-40 (4); PEI-70 (5); PEI -750 (6).

Figure 4.

a. Dependence of the percentage of residual mass of coatings (mres) formed from PEI on the number of wash-off cycles (nw); PEI-1.3 (1); PEI-3 (2); PEI-25 (3); PEI-40 (4); PEI-70 (5); PEI -750 (6).

Figure 4.

b. Dependence of the percentage of residual mass of coatings (mres) formed from PDADMAC on the number of wash-off cycles (nw); PDADMAC-100 (1); PDADMAC-300 (2); PDADMAC-500 (3).

Figure 4.

b. Dependence of the percentage of residual mass of coatings (mres) formed from PDADMAC on the number of wash-off cycles (nw); PDADMAC-100 (1); PDADMAC-300 (2); PDADMAC-500 (3).

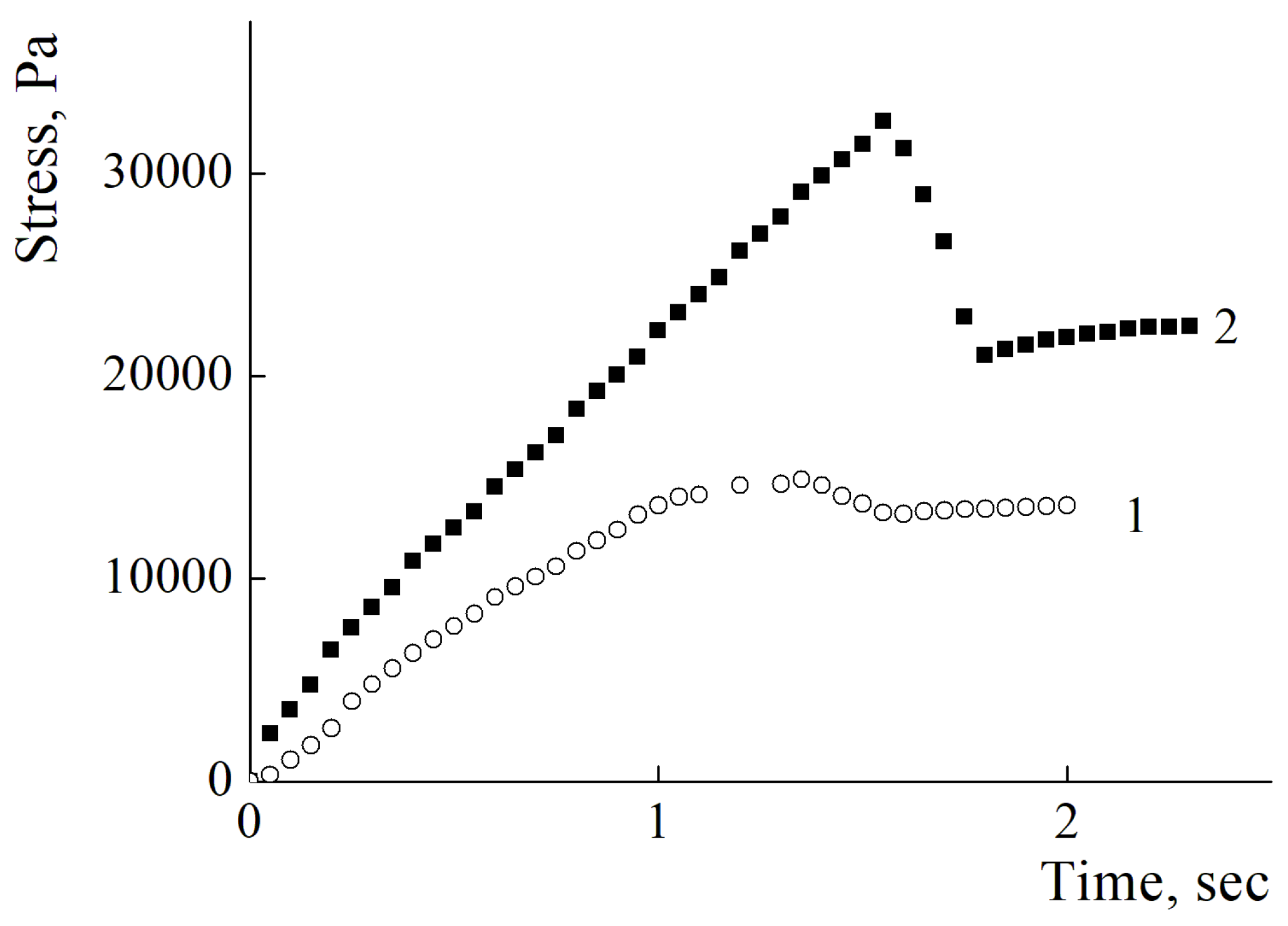

3.4. Study of Adhesive Properties

To evaluate the adhesive properties of coatings formed from PEI and PDADMAC of different molecular weights, the dynamometry method was used.

Figure 5 shows a typical stress versus time curved for the polycations under study. The maximum value of the applied stress (peak value) was taken as the characteristics of the adhesive properties of the polymer film.

It was found that no significant difference in adhesive properties could be detected for coatings prepared from all the studied polycations.

Table 3.

Maximal stress values of the polycationic films.

Table 3.

Maximal stress values of the polycationic films.

| Polycation |

Stress, MPa |

| PDADMAC-100 |

26600 |

| PDADMAC-300 |

30900 |

| PDADMAC-500 |

31500 |

| PEI-1.3 |

11600 |

| PEI-70 |

18000 |

| PEI-750 |

19000 |

Further experiments were performed with PEI-750 and PDADMAC-500.

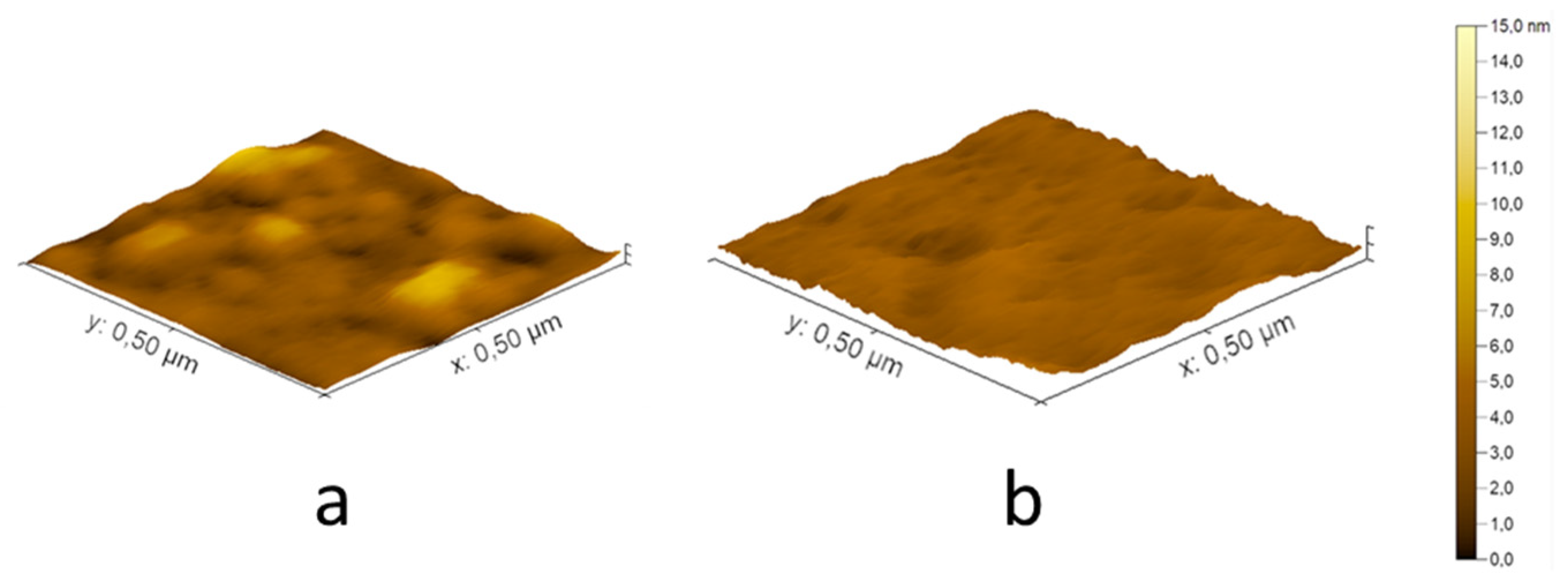

3.5. The structure of the polycationic coatings.

The

Figure 6 demonstrates AFM images of the coatings from PEI-750 and PDADMAC-500 on the glass surface. Almost smooth continuous films were obtained for each studied polycation.

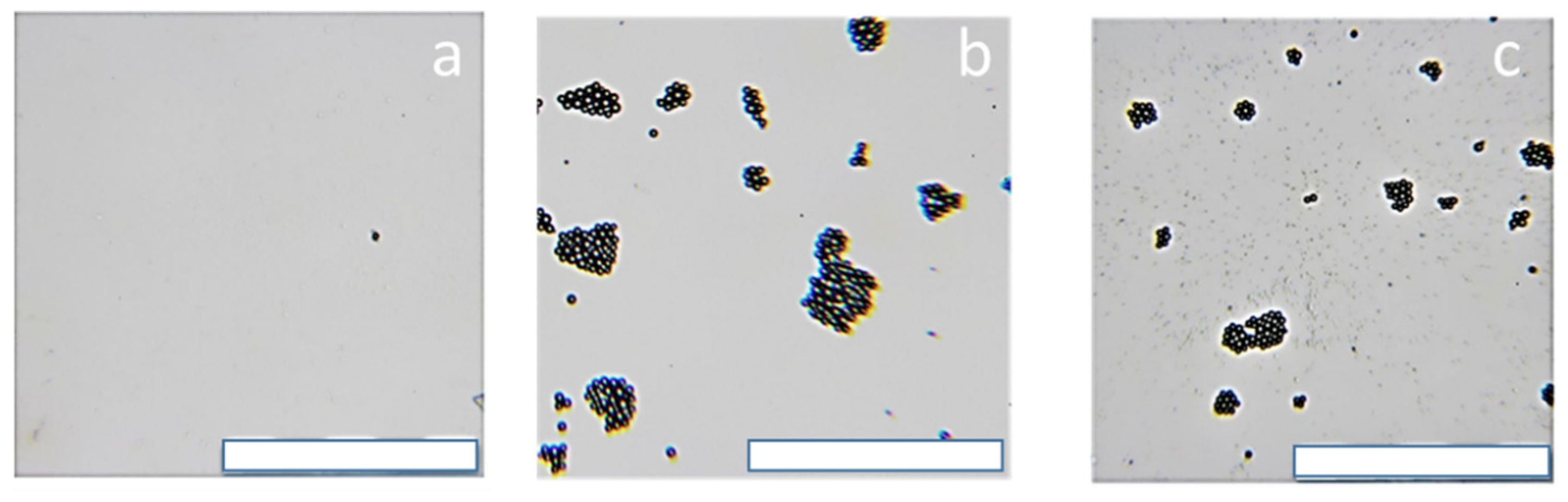

3.6. Interaction of the polycationic coatings with model cell membranes.

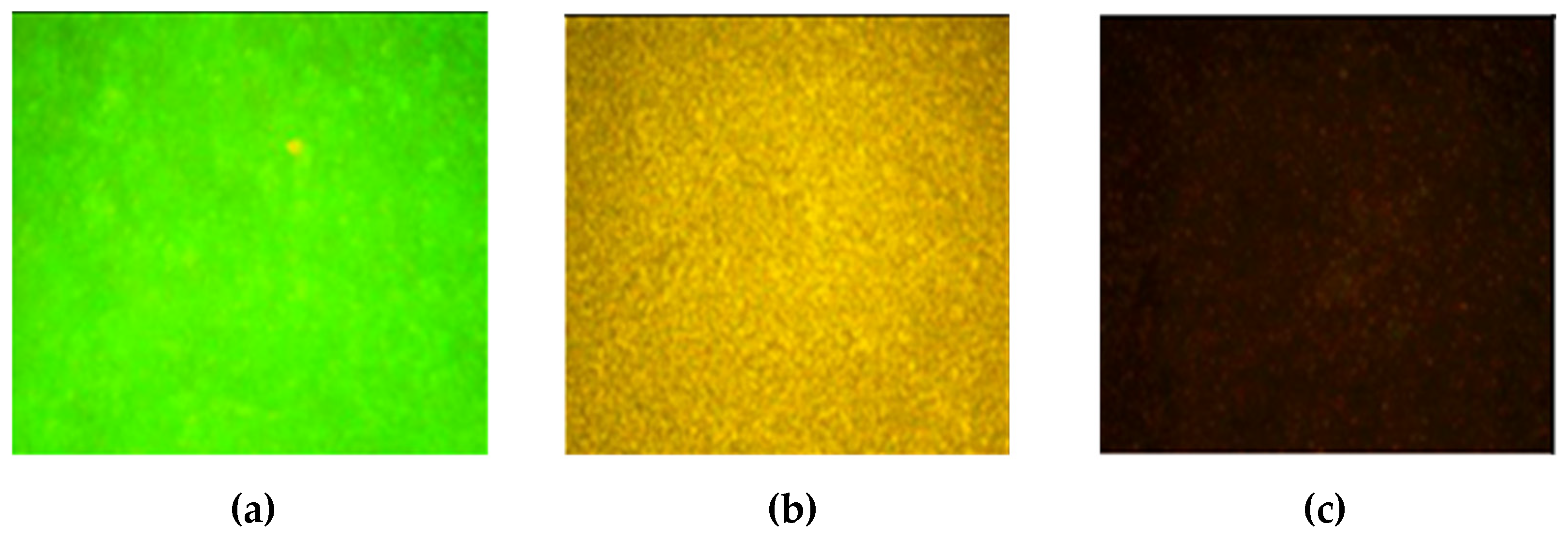

To evaluate the ability of the coatings from the PEI and PDADMAC to immobilize the bacteria the experiment with model latex decorated with lipid bilayer simulating bacteria membrane was performed. The optical images of the pure glass; glass coated with PEI and glass coated with PDADMAC after contact with suspension of latex are presented on

Figure 7. Almost no adsorption of latex on the pure glass surface was observed. Several latex particles per significant large area of the glass could be attributed to van-der-Waals interactions driven adsorption. For the coatings of polycations numerous latex particles could be found on the surface reflecting electrostatic adsorption of anionic microparticles on the surface with cationic groups.

3.6. Biocide properties of the polycationic coatings against food-born bacteria.

At first, the biocidal activity of polycations is the microbiological assessment of bacterial survival of food-borne bacteria

L. monocytogenes. The results are presented in in

Table 4.

Both PEI and PDADMAC showed the absolute antibacterial effect killing 100% of L. monocytogenes.

The growth inhibitory effect at the lowest exposure concentration was PDADMAC-500. The concentrations of 2.5 mg/ml turned out to be the minimum inhibitory, at which visual growth was not detected on the liquid medium, and the concentration of 5 mg/ml was the minimum bactericidal, at which less than 99.9% of cells grew on agar plates. For the PEI-750 the value of MIC of 5 mg/ml did not differ significant reflecting high antibacterial activity.

Table 5.

MIC and MBC method for testing activity of polymers towards L. monocytogenes solutions.

Table 5.

MIC and MBC method for testing activity of polymers towards L. monocytogenes solutions.

| Polymers |

L. monocytogenes |

| MIC, mg/ml |

MBC, mg/ml |

| PEI-750 |

5 |

5 |

| PDADMAC-500 |

2.5 |

5 |

Then, antibacterial properties of films, prepared via drying of the polycation aqueous solutions, were examined. Polymer layers were formed on glass slide pieces, which were then inoculated with

L. monocytogenes. As follows from the data of

Table 6, all polymers quantitatively suppressed the growth of bacterial cells.

The cells on the glass surfaces were visualized using the Live/Dead Kit.

Figure 8 reflects fluorescence of cells treated with the Live/Dead Kit and observed through a fluorescent microscope. SYTO-9 from the kit only stained living bacteria green, while propidium iodide entered dead bacteria through defects in the cell walls and colored the bacteria from light yellow to dark brown. A control glass with no polymer covered by the

L. monocytogenes cells (photo 1) demonstrates bright green color which definitely indicated the intact structure of the adsorbed cells. Contrastingly, photos 2-3 for cells on the glasses, covered with the cationic polymers, have a colors from yellow to very brown which proves the death of cells after their deposition over films from the cationic polymers.

4. Discussion

Both polycations- PDADMAC and PEI were shown to possess antimicrobial activity towards

B. subtilis in solutions. Two important observations should be pointed out. The nature of amino-group in polycation and the degree of polymerization do not play essential role in antibacterial activity of the studied polymers in solutions. Taking into account previously reported data on MIC of hyperbranched copolymer of epichlorohydrin and ethylenediamine towards

B. subtilis with values of similar order, we may state that linear or hyperbranched structure of the macromolecule can`t be considered as key parameter affecting on biocide activity of polycations [

38].

The application of an aqueous solutions of polycations to the surface of a hydrophilic glass with further drying in the air leads to the formation of a polymer coating. The adhesion of the macromolecules on the glass is driven by electrostatic forces between negatively charged silanol groups and aminogroups. The most of macromolecules in adsorbed layer form film of interpenetrated chains. Polycations are known to be hygroscopic. So, it is reasonable to expect that polycation films will absorb water from the environment. In solutions, solvatation of the ammonia salts depend on the nature of the aminogroups but for the studied films of polyelectrolytes no significant influence of the primary, ternary and quaternary aminogroups on swelling in environment with controlled humidity was found.

It is obvious that degree of polymerization of macromolecule should affect on strength of the adhesion on glass surface. The dynamomentric experiments have shown that the mechanical break of the polyelectrolyte films is predominantly governed by cohesion forces. The shape of the stress curves on the

Figure 5 reflects corresponds to cohesion break mechanism. For the PEI samples with high molecular weights the peak stresses were almost identical with mean value 18500 Pa and the decrease in mechanical properties of films was observed for oligomer fraction with mean value of peak stress 11600 Pa. The same behavior of the mechanical properties of the films from different samples of PDADMACs was observed. For the samples with high molecular weights the peak stresses were almost identical with mean value 30800 Pa and the decrease in mechanical properties of films was observed for oligomer fraction with mean value of peak stress 26600 Pa. These results are in good agreement with the cohesion-governed mechanism of the film break. Moreover, the differences in absolute values of peak stresses between PEI and PDADMAC macromolecules could be attributed to differences in macromolecules architectures. Linear PDADMAC macromolecules could penetrate between many lateral layers inside the film while for the branched PEI molecules this possibility is restricted.

The vanishing of the polyelectrolyte coating with water depends on two major parameters. First, the nature of the aminogroup – for the quaternary aminogroups in PDADMAC the process of the dissolving of the film takes place faster than for the PEI with primary and ternary groups. Second, the molecular weight of macromolecules. With the reaching of critical values of molecular weights of polycations the films either undergo fast mass loss with wash-off procedure. For the PDADMAC molecules this critical weight was 100kDa while for the PEI this value was 40kDa. Both polycations have different mass of monomer unit and different architectures. So, such parameters as “degree of polymerization” and “average molecular weight” could not be used for direct compare of the results for these polycations. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated that it is the diffusion coefficient of polycation is the parameter that allows us to describe the behavior of the films in wash-off procedure correct. The critical value of the D0 = 1×10-7 cm2/s determines the resistance of the polyelectrolyte film towards fast wash-off for both PEI and PDADMAC.

Despite it was reported that increase of molecular weight of the polymers of the same structure could decrease or increase their biocidal activity [

39,

40,

41], we have demonstrated that molecular weight of the polycation more affect on mechanical properties of the films and their behavior under watering conditions. So, polycations with high molecular weights have higher potential for the preparation of effective biocide coatings.

Thus, the analysis of the efficiency of polycationic coatings towards foodborne bacteria L. monocytogenes was studied with the samples with higher values of Mw – PEI-750 and PDADMAC-500. The morphology of the coatings obtained by AFM were confirmed to be above the coating. Hence, bacteria with negatively charged membranes will adsorb on the film and undergo action of the polycations. At the same time the macromolecules that leave the surface of the film during the watering process could act as biocides in suspension of the bacterias that were not adsorbed on the film. Both PEI and PDADMAC were demonstraded to have antibacterial activity in solution and on the surface of the film against L. monocytogenes. So, the choice of the polycation and its molecular weight for the formation of the biocide coatings should be determined more by requirements to mechanical properties of the supposed coating.

5. Conclusions

Branched PEI and linear PDADMAC of different molecular weights were studied to estimate the role of chemical nature of charged groups, architecture and the degree of polymerization of macromolecules upon physico-mechanical and antibacterial properties of the coatings from these polymers on the glass surface. Surprisingly, the values of MIC for polyelectrolytes did not depend on molecular weights of the polymer samples in wide range of the masses. The significant impact of the chemical nature of aminogroup (primary, ternary or quaternary) on biocidal properties of macromolecules was not found to possess. For the coatings from the different samples of PEI and PDADMAC it was demonstrated that saturation of the films with water depends on the humidity of the surrounding media but not on the structural and chemical characteristics of polycations. The mechanical properties of the coatings from polycations were demonstrated to have determining cohesion nature between macromolecules over adhesion forces between surface and polymer film. Linear PDADMAC ensures higher cohesion strength due to possibility to penetrate between more layers in film than branched PEI. With the decrease of molecular weight, the mechanical stress required to break the coating reduces for the both series of PEI and PDADMAC. The ability of the polyelectrolyte film to resist to wash-off with water strongly depend on diffusion coefficient of the macromolecules that form the coatings. This parameter is more suitable to describe the decisive characteristic of macromolecules that allows one to compare polyelectrolytes with different architectures and chemical structures. Thus, the polycations with high molecular weighs have higher potential for the utilization in formation of coatings. Concerning the biocide activity of the polycationic films the antibacterial effect towards L. monocytogenes. was demonstrated for both PEI and PDADMAC without significant difference.

Therefore, the choice of the polycation for the effective biocide coatings should be determined by the requirements to the mechanical properties of the films. This properties are affected by the diffusion coefficients, architectures and chemistry of macromolecules. At the same time the antimicrobial activity of the coatings are determined by the polycationic nature of the coatings without significant respect to nature of the aminogroup.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.S.; methodology, Yu.K.Yu., V.A.P.; validation, V.A.P. and A.V.S.; formal analysis, V.A.P. and A.V.S.; investigation, V.A.P., V.I.M., A.V.B., A.K.B., O.A.K., D.S.B., M.A.G., A.V.S.; resources, A.A.S. and A.V.S.; data curation, V.A.P. and A.V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.S.; writing—review and editing, A.A.S. and A.V.S.; visualization, V.A.P.; supervision, A.V.S.; project administration, A.A.S.; funding acquisition, A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (project № 075-15-2020-775).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The thermal analysis was performed using the equipment purchased in the scope of the Program for Development of Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food Security and the 2015–2030 Sustainable Development Goals: From Human to Planetary Health: Perspectives and Opinions, Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 7, e000513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gálvez, F.; Gómez, P.A.; Artés, F.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Aguayo, E. Interactions between Microbial Food Safety and Environmental Sustainability in the Fresh Produce Supply Chain. Foods 2021, 10, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, K.; Verran, J. Formation, architecture and functionality of microbial biofilms in the food industry Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, M.A.; Gupta, K.; Bardhan, P.; Borah, M.; Sarkar, A.; Eldiehy, K.S.H.; Bhuyan, S.; Mandal, M. Microbial biofilm: A matter of grave concern for human health and food industry. J. Basic Microbiol. 2021, 61, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.M. The Role of Bacterial Biofilm in Antibiotic Resistance and Food Contamination. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 1705814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mevo, S.I.U.; Ashrafudoulla, M.; Mizan, M.F.R.; Park, S.H.; Ha, S.D. Promising strategies to control persistent enemies: Some new technologies to combat biofilm in the food industry-A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 5938–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toushik, S.H.; Roy, A.; Alam, M.; Rahman, U.H.; Nath, N.K.; Nahar, S.; Matubber, B.; Uddin, M.J.; Roy, P.K. Pernicious Attitude of Microbial Biofilms in Agri-Farm Industries: Acquisitions and Challenges of Existing Antibiofilm Approaches. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.X.; Calautit, J.K. A Comprehensive Review on the Integration of Antimicrobial Technologies onto Various Surfaces of the Built Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Ghosh, S.; Patra, D.; Haldar, J. Advancements in release-active antimicrobial biomaterials: A journey from release to relief. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2022, 14, e1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, M.; Tolouei, R.; Lesage, O.; Lévesque, L.; Turgeon, S.; Tatoulian, M.; Mantovani, D. On the long term antibacterial features of silver-doped diamondlike carbon coatings deposited via a hybrid plasma process. Biointerphases. 2014, 9, 029013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmatullayeva, D.; Ospanova, A.; Bekissanova, Z.; Jumagaziyeva, A.; Savdenbekova, B.; Seidulayeva, A.; Sailau, A. Development and characterization of antibacterial coatings on surgical sutures based on sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/chitosan/chlorhexidine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 236, 124024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohmann, S.; Menne, M.; Hesse, D.; Bischoff, S.; Schiffner, R.; Diefenbeck, M.; Liefeith, K. Biomimetic multilayer coatings deliver gentamicin and reduce implant-related osteomyelitis in rats. Biomed. Tech. 2019, 64, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salta, M.; Dennington, S.P.; Wharton, J.A. Biofilm Inhibition by Novel Natural Product- and Biocide-Containing Coatings Using High-Throughput Screening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, M.; Hu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhu, M.; Ni, Y.; Wang, J. Advanced Coatings with Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity for Kumquat Preservation. Foods 2022, 11, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, M. S.; Moghaddam, S. T.; Shang, M.; Niu, J. A Flexible Anti-Biofilm Hygiene Coating for Water Devices. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3991–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Brito, F.A.E.; de Freitas, A.P.P.; Nascimento, M.S. Multidrug-Resistant Biofilms (MDR): Main Mechanisms of Tolerance and Resistance in the Food Supply Chain. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.; Junaid, K.; Yasmeen, H.; Naseer, A.; Alam, H.; Younas, S.; Qamar, M.U.; Abdalla, A.E.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; Ahmad, N.; Bukhari, S.N.A. Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance and Heavy Metal Tolerance of Biofilm-Producing Bacteria Isolated from Dairy and Non-Dairy Food Products. Foods 2022, 11, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakellis, P.; Kaprou, G.D.; Papavieros, G.; Mastellos, D.C.; Constantoudis, V.; Tserepi, A.; Gogolides, E. Enhanced antibacterial activity of ZnO-PMMA nanocomposites by selective plasma etching in atmospheric pressure. Micro Nano Eng 2021, 13, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- des Ligneris, E.; Dumée, L.F.; Al-Attabi, R.; Castanet, E.; Schütz, J.; Kong, L. Mixed Matrix Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)-Copper Nanofibrous Anti-Microbial Air-Microfilters. Membranes 2019, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isopencu, G.; Mocanu, A. Recent Advances in Antibacterial Composite Coatings. Coatings 2022, 12, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashki, S.; Asgarpour, K.; Tarrahimofrad, H.; Hashemipour, M.; Ebrahimi, M. S.; Fathizadeh, H.; Khorshidi, A.; Khan, H.; Marzhoseyni, Z.; Salavati-Niasari, M.; Mirzaei, H. Chitosan-based nanoparticles against bacterial infections. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopiasz, R. J.; Tomaszewski, W.; Kuźmińska, A.; Chreptowicz, K.; Mierzejewska, J.; Ciach, T.; Jańczewski, D. Hydrophilic Quaternary Ammonium Ionenes-Is There an Influence of Backbone Flexibility and Topology on Antibacterial Properties? Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, e2000063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; You, W.; Wang, H.L.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, X.; Wang, F.; You, Y.Z. Cyclic topology enhances the killing activity of polycations against planktonic and biofilm bacteria. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2022, 10, 4823–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigareva, V.A.; Senchikhin, I.N.; Bolshakova, A.V.; Sybachin, A.V. Modification of Polydiallyldimethylammonium Chloride with Sodium Polystyrenesulfonate Dramatically Changes the Resistance of Polymer-Based Coatings towards Wash-Off from Both Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Surfaces. Polymers 2022, 14, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misin, V.M.; Zezin, A.A.; Klimov, D.I.; Sybachin, A.V.; Yaroslavov, A.A. Biocidal Polymer Formulations and Coatings. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2021, 63, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Jolly, L.; Mukherjee, R.; Haldar, J. An easy-to-use antimicrobial hydrogel effectively kills bacteria, fungi, and influenza virus. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 2014–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, S.K.R.; Reghu, S.; Vikhe, Y.; Zheng, H.; Koh, C.H.; Chan-Park, M.B. Novel Antimicrobial Coating on Silicone Contact Lens Using Glycidyl Methacrylate and Polyethyleneimine Based Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 41, e2000175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkrtchyan, K.V.; Pigareva, V.A.; Zezina, E.A.; Kuznetsova, O.A.; Semenova, A.A.; Yushina, Y.K.; Tolordava, E.R.; Grudistova, M.A.; Sybachin, A.V.; Klimov, D.I.; Abramchuk, S.S.; Yaroslavov, A.A.; Zezin, A.A. Preparation of Biocidal Nanocomposites in X-ray Irradiated Interpolyelectolyte Complexes of Polyacrylic Acid and Polyethylenimine with Ag-Ions. Polymers 2022, 14, 4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, J.; Akkapeddi, P.; Ghosh, C.; Uppu, D.S.; Haldar, J. A Biodegradable Polycationic Paint that Kills Bacteria in Vitro and in Vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016, 8, 29298–29309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Duvvuri, L.S.; Farah, S.; Beyth, N.; Domb, A.J.; Khan, W. Antimicrobial polymers. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3(12), 1969–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuber, S.; Sill, A.; Efthimiopoulos, I.; Nestler, P.; Fricke, K.; Helm, Ch.A. Influence of molecular weight of polycation polydimethyldiallylammonium and carbon nanotube content on electric conductivity of layer-by-layer films. Thin Solid Films 2022, 745, 139103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougier, V.; Cellier, J.; Duchemin, B.; Gomina, M.; Bréard, J. Influence of the molecular weight and physical properties of a thermoplastic polymer on its dynamic wetting behavior. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 269, 118442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assem, Y.; Chaffey-Millar, H.; Barner-Kowollik, Ch.; Wegner, G.; Agarwal, S. Controlled/Living Ring-Closing Cyclopolymerization of Diallyldimethylammonium Chloride via the Reversible Addition Fragmentation Chain Transfer Process. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 3907–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigareva, V.A.; Sybachin, A.V. BBA or stepanova.

- Panova, T.V.; Efimova, A.A.; Berkovich, A.K.; Efimov, A.V. Plasticity control of poly(vinyl alcohol)–graphene oxide nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 24027–24036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc. 2008, 3(2), 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.D.; Steigbigel, R.T.; Davis, H.T.; Chapman, S.W. Method for reliable determination of minimal lethal antibiotic concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1980, 18, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigareva, V.; Stepanova, D.; Bolshakova, A.; Marina, V.; Osterman, I.; Sybachin, A. Hyperbranched Kaustamin as an antibacterial for surface treatment. Mendeleev Communications 2022, 32, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahit, A.; Yildirim, M. Molecular weight dependent antistaphylococcal activities of oligomers/polymers synthesized from 3-aminopyridi. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2010, 75, 104-104. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, T.; Hirayama, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Tazuke, S. , Watanabe, M. Polycationic biocides with pendant active groups: molecular weight dependence of antibacterial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986, 30, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hae Cho, C.A.; Liang, C.; Perera, J.; Liu, J.; Varnava, K.G.; Sarojini, V.; Cooney, R.P.; McGillivray, D.J.; Brimble, M.A.; Swift, S.; Jin, J. Molecular Weight and Charge Density Effects of Guanidinylated Biodegradable Polycarbonates on Antimicrobial Activity and Selectivity. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).