1. Introduction

Although heap bioleaching of secondary copper ore has been industrialized for decades, bioleaching of chalcopyrite (CuFeS

2) ore has not largely applied due to the low leaching rate [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Acidic solutions composed of sulfuric acid and ferric sulfate are particularly common in chalcopyrite leaching researches. In the sulfuric acid condition, Fe³⁺ acts as an oxidizing agent, and the variation in the redox potential, as well as microbial activity, are key factors in determining the leaching rate of chalcopyrite [

5].

Chalcopyrite can be attacked and degraded by Fe³⁺ and protons, with polysulfide and elemental sulfur being the main intermediates [

1,

6]. These bioleaching acidophilic microorganisms mainly have the ability of iron-oxidizing and sulfur-oxidizing [

7]. Such as

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and

Leptospirillum ferriphilum, as iron-oxidizing microorganisms, promote the oxidation of ferrous iron, thereby increasing the solution potential and playing a significant role in enhancing chalcopyrite leaching.

Acidithiobacillus caldus and

Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, as sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms, can remove intermediate sulfur layers, thereby increasing the leaching rate of chalcopyrite. The promoting effect of microorganisms on chalcopyrite leaching was reflected not only in their action on the mineral but also in their influence on the environment, as oxidant ferric ion regenerating and affecting to the redox potential, which together impacts the chalcopyrite leaching process [

8,

9,

10].

In 1964, Silverman and Ehrlich first proposed that mineral dissolution by acidophiles could be achieved either through the "direct mechanism" or through the "indirect mechanism" of bacteria oxidizing Fe²⁺ to regenerate Fe³⁺ [

11]. These two mechanisms provided important theoretical support for the development of biohydrometallurgy over the decades [

12]. Although, some researchers suggest that small pits on the ore surface reflect the impact of "contact leaching", chemical oxidation can also cause the pit formation [

13,

14]. Scientists later discovered that microbial mineral leaching was accompanied by complex electrochemical and biochemical behaviors, while there was no such direct leaching by enzymes [

15]. Sand and others further proposed no matter the iron and sulfur oxidation were both indirect leaching [

3,

16], and then the concepts of "contact" and "non-contact" leaching, which have been widely accepted [

17]. Contact leaching takes into account that cells attach to the surface of sulfide minerals. It means that the electrochemical processes resulting in the dissolution of sulfide minerals take place at the interface between the microbial cell and the mineral sulfide surface. This space is filled with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), a mixture of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [

16,

18]. Contact leaching can be understood as the adsorption of microorganisms on the surface of sulfide minerals, leading to faster oxidation of Fe²⁺, as well as the oxidation of the intermediate sulfur during chalcopyrite oxidation [

5]. Non-contact leaching is basically exerted by planktonic microorganisms, which oxidize iron(II) ions in solution [

3]. The regenerated iron(III) ions get into contact with a mineral surface, where they are reduced, and the sulfide moiety is oxidized.

However, the contribution of “contact leaching” has not been fully verified, as the influence of "non-contact leaching" was not excluded in researches. Redox potential is the critic factor for chalcopyrite oxidation [

2], thus the microbial influenced redox potential also significantly affect the chalcopyrite leaching rate. This challenge makes it difficult to precisely reveal the contribution of contact and non-contact microbes to the oxidation process of chalcopyrite. Therefore, it is particularly important to conduct in-depth research on microbial leaching of chalcopyrite under controlled solution redox potential, to maintain constant "non-contact leaching" when studying the mechanism of "contact leaching" on chalcopyrite. During microbial leaching, most microorganisms are adsorbed onto the mineral surface [

7]. This further emphasize the importance of the contact microbes on chalcopyrite leaching.

A novel device was established to stabilize the redox potential, as well as to separately investigate the contribution of contact and non-contact microbes. The controlled redox potential can make the constant microbial non-contact effect, allowing for the investigation of the contribution of contact microorganisms to chalcopyrite leaching. Also, importance of redox potential on chalcopyrite, also explained as non-contact leaching, can be reflected. The morphology of the mineral surface was observed through scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the valence states and distribution of different elements on the residue surface were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). By studying the surface products of residue samples as well as the microbial community composition, we can infer the role of attached microorganisms on chalcopyrite bioleaching.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Microbes Preparing

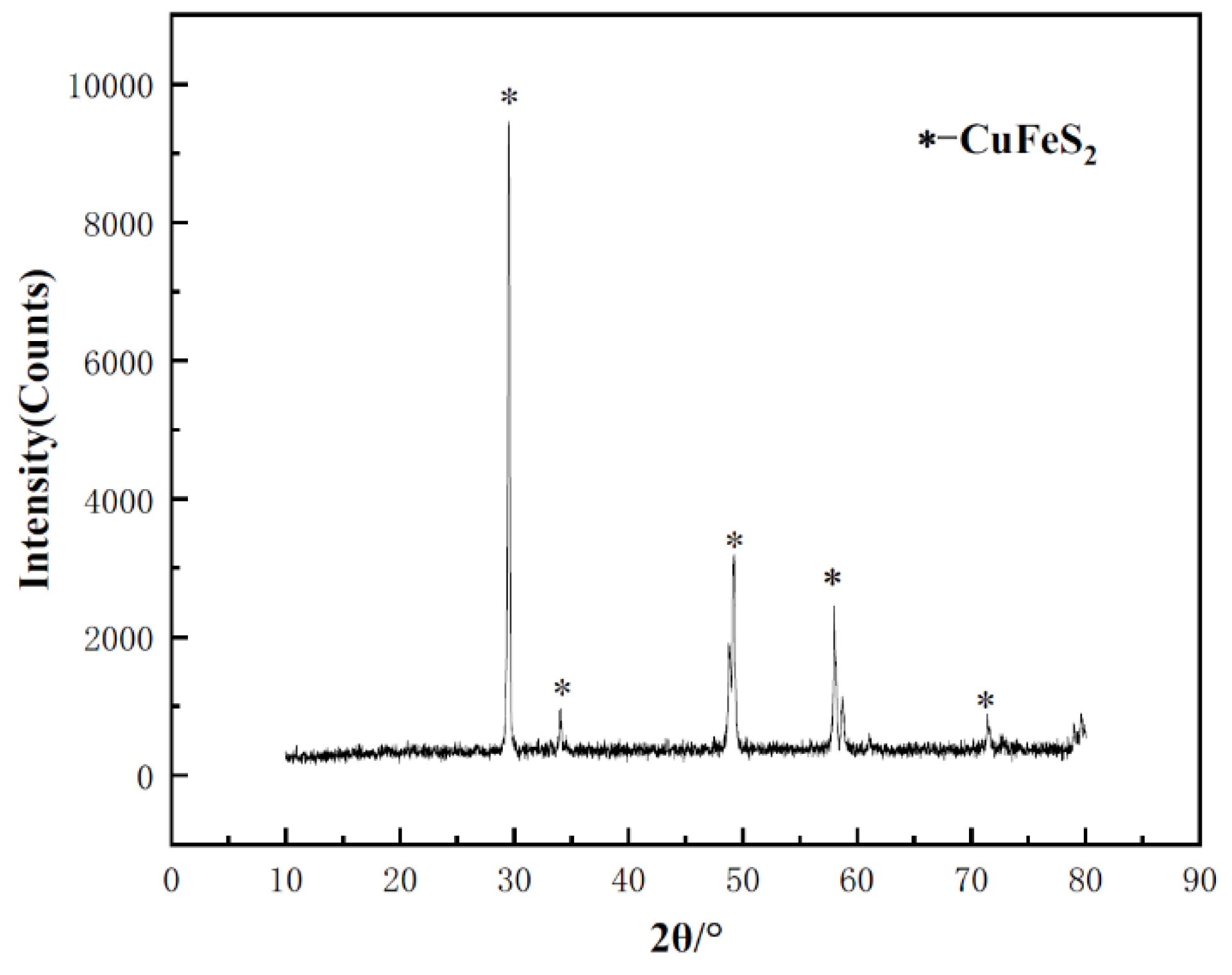

Highly pure crystal chalcopyrite sample was collected from a mine at Guilin City, Guangxi Province. Ore was crushed to about 2 mm, and the gangue impurities were removed using a plier. Then the ore was grinded to a particle size of less than 200 μm, and wet sieving was used to select the ore particles in the range of 74 μm to 105 μm for leaching tests. X-ray diffraction testing revealed no diffraction peaks from other crystals, indicating the high purity of the sample. To remove the oxide layer on the sample's surface, the powder sample was washed in a 3 mol L-1 hydrochloric acid solution at 50°C for 30 minutes. Subsequently, anhydrous ethanol was added, and the sample was cleaned multiple times using an ultrasonic cleaner. After cleaning, the sample was filtered and washed with deionized water to ensure complete removal of impurities. Finally, the cleaned samples were placed in a vacuum drying oven for drying and then uniformly mixed for subsequent experiments.

To observe the changes in the surface morphology of chalcopyrite and for the ToF-SIMS testing after leaching, the chalcopyrite was cut into cubes approximately 10 mm × 10 mm × 3 mm. After polishing of the surface, the cubes were cleaned with hydrochloric acid and ethanol to ensure surface cleanliness.

The microbial consortium used in this experiment was sourced from the industrial heap bioleaching plants of copper sulfide at Monywa mine, Myanmar [

19,

20]. To cultivate the microorganisms, an optimized 9K medium was used, with the following specific composition: (NH4)

2SO

4 3 g/L, KCl 0.1 g/L, K

2HPO

4 0.5 g/L, MgSO

4•7H

2O 0.5 g/L, and Ca(NO

3)

2 0.01 g/L, 5 g/L of FeSO

4 and 2 g/L of S, pH 1.5, at 35°C in the oscillator. When the microorganisms reached the stationary phase, they were separated from the medium by filtration with 0.22 μm filter membrane, and the microorganisms were washed with sulfuric acid solution at pH 1.5 to remove any residual iron and sulfur from the medium.

Figure 1.

XRD spectra of the chalcopyrite sample.

Figure 1.

XRD spectra of the chalcopyrite sample.

2.2. Apparatus and Batch Experiments

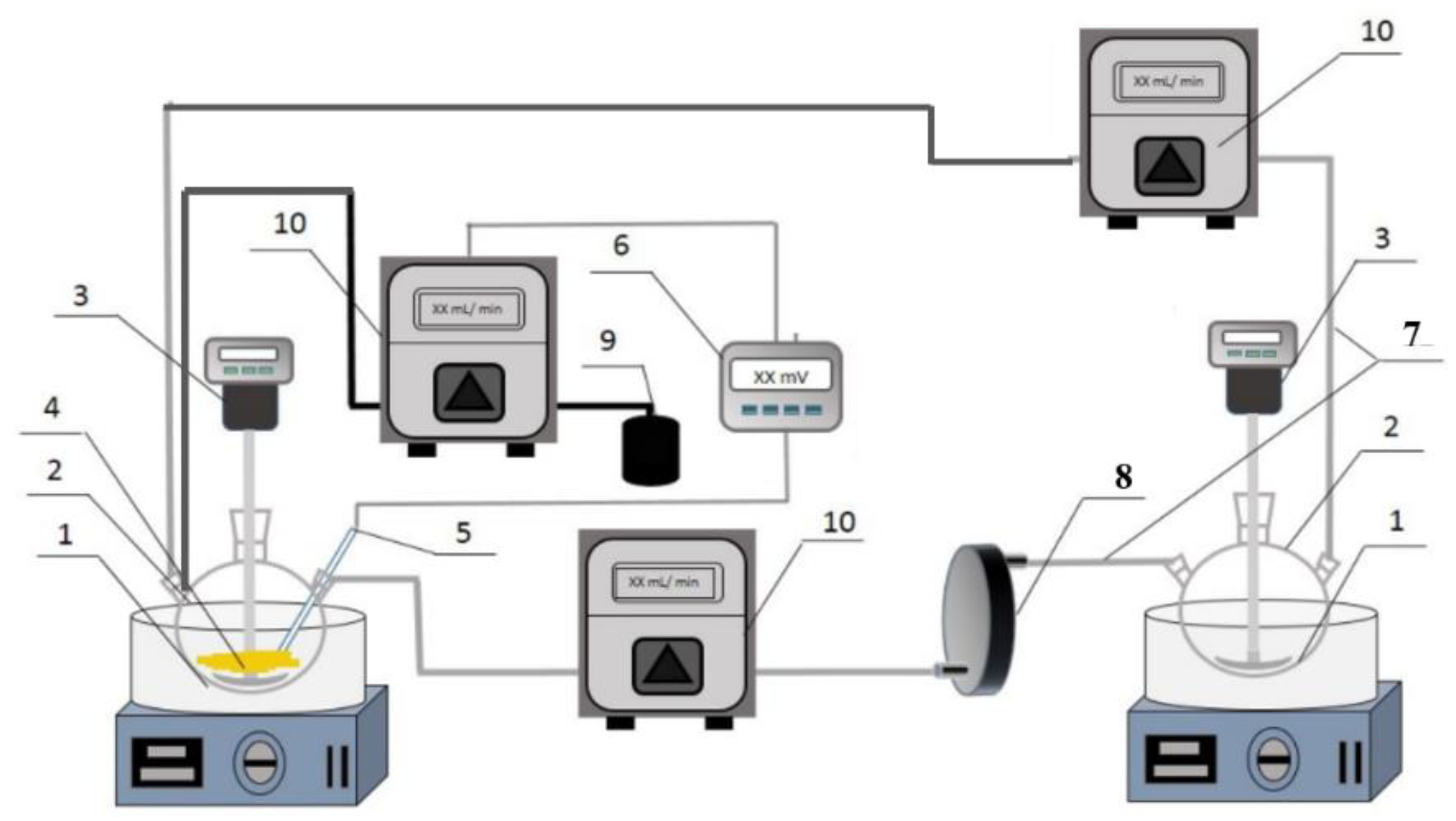

The experiment was conducted in a device which can control the redox potential and also allow or not allow microbes from contacting with the minerals. This system mainly consisted of four parts: the redox potential control unit, the leaching unit, the microbial culture unit, and the solution circulation system [

14]. The redox potential control unit uses H

2O

2 or ascorbic acid solution to control the redox potential of the solution. The redox potential of the solution in the leaching unit is measured using a platinum ring electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. A 1000 mL three-neck flask was also used as the microbial culture container, with isolation between flasks achieved through a filtration plate containing a 0.22 μm filter membrane. This design ensured that chalcopyrite did not come into direct contact with the microorganisms, but instead, the oxidation process occurred via a "non-contact" interaction. In the "contact leaching" comparison experiment, no membrane was installed in the filtration plate, allowing microorganisms to circulate with the solution, and under the circulation reaction, microorganisms could contact with the chalcopyrite. To maintain the solution balance between the two culture flasks, a peristaltic pump was used to pump the solution, ensuring the ionic concentration in both culture flasks remained consistent.

Figure 2.

Apparatus for chalcopyrite leaching under controlled redox potentials with or without microbial contacted leaching (1—thermostatic oil bath; 2—three-necked flask; 3—stirrer; 4—chalcopyrite sample; 5—ORP probe; 6—ORP controller; 7—silicon tube; 8—0.22 μm filter plate; 9—H2O2 or ascorbic acid solution; 10—peristaltic pump).

Figure 2.

Apparatus for chalcopyrite leaching under controlled redox potentials with or without microbial contacted leaching (1—thermostatic oil bath; 2—three-necked flask; 3—stirrer; 4—chalcopyrite sample; 5—ORP probe; 6—ORP controller; 7—silicon tube; 8—0.22 μm filter plate; 9—H2O2 or ascorbic acid solution; 10—peristaltic pump).

Batch experiments with fine powders or chalcopyrite cubes utilized a 9K medium, made by mixing ferrous sulfate and ferric sulfate, with a total iron concentration set to 2.5 g/L. Eight grams of chalcopyrite powder were added to the leaching flask with 1 L solution. During the experiment, an ORP controller and peristaltic pump were used to precisely adjust the solution potential, maintaining it at 650 mV, 750 mV, and 850 mV (vs. SHE) respectively at 35°C. Microorganisms were added to the microbial culture flask, and their concentration was adjusted to 1×107 cells mL-1. During the leaching, solution samples were taken every 24 hours, and Cu concentration was determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES). After the leaching, the residue was filtered, washed, and dried in a low-temperature vacuum drying oven, with the remaining material used for extracting adsorbed microorganisms. The leaching of the chalcopyrite cubes for surface morphology observation and ToF-SIMS testing was done with the similar above procedure.

2.3. Surface Mophology by SEM

The chalcopyrite samples after biological oxidation underwent a series of pre-treatment steps before scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis. The chalcopyrite residue samples were placed in a 3% glutaraldehyde solution and fixed at 4°C for 24 hours. After fixation, the chalcopyrite samples were sequentially immersed in 50%, 75%, and 99% ethanol solutions for 10 minutes each. Following dehydration, the samples were dried in a ventilated environment for 2 hours. After drying, the chalcopyrite samples underwent a gold sputtering treatment. The accelerating voltage for the SEM was set to 15 kV.

2.4. Surface Components by XPS

The surface copper, iron and sulfur species of the chalcopyrite residues under various treatments was analyzed using an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The incident radiation consisted of monochromatic Al Kα X-rays (1486.7 eV) at 150W (15 kV, 15 mA). The base pressure in the analysis chamber was 2.31 × 10⁻¹⁰ mbar, which increased to 2.31 × 10⁻⁸ mbar during sample analysis. Survey scans were conducted to identify the elements present, while high-resolution scans were performed to determine the oxidation states and composition of sulfur and iron. Data processing and fitting were carried out using the Avantage v5.938 software package and the relative sensitivity factor (RSF) library. The spectra were charge-referenced to the adventitious C 1s peak at 248.8 eV, and the smart background subtraction method was applied.

2.5. Copper, Iron, Sulfur Distribution by Tof-SIMS

The copper, iron, sulfur distribution in different depth were conducted using ToF-SIMS (TOF.SIMS5-100, ION-TOF, Germany). ToF-SIMS can analyze the compositional resolution of substances ranging from 10-6 to 10-9. By adjusting the primary ion current density, information about the surface monolayer of atoms and molecules can be determined. A Bi+ primary ion beam was used with an incident power of 30 keV at a 45° angle, and a scanning area of 100 μm × 100 μm. The secondary ion polarity and mass range are 0 to 3000. The sputtering positive ion beam is O2+, while the sputtering negative ion beam is Cs+, with an incident power of 2 keV at a 45° angle. The sputtering rate is 0.54 nm s-1.

2.6. Quantification of Elemental Sulfur by HPLC Assay

One gram of chalcopyrite residue was cleaned three times in ethanol using ultrasonic treatment. Afterward, the treated residue was subjected to centrifugal separation at high speed for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. The sulfur content in the supernatant was tested using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Hypersil-ODS-5μ chromatographic column was used as the separation medium, with pure methanol as the elution solvent, and a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min was set [

21].

2.7. Microbial Community Analysis

An optical binocular microscope and a hemocytometer counting method were used to determine the number of microorganisms in the solution. The Fast DNA Spin kit was used for efficient extraction of microbial DNA, followed by the detection of microbial communities both in the solution and adhered to the mineral surface. Using the primer F515 (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and R806 (5′-GGACTACVSGGGTATCTAAT-3′), the microbial 16S rRNA was amplified. High-throughput sequencing of the amplification products was performed using Illumina MiSeq sequencing technology, and through data filtering and merging, more accurate and comprehensive microbial community information was obtained and classified into different operational taxonomic units (OTUs). To further identify the microbial species represented by these OTUs, representative sequences of each OTU were selected and compared using BLAST against the NCBI database.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Characteristics of Oxidized Chalcopyrite Cube’s Surface

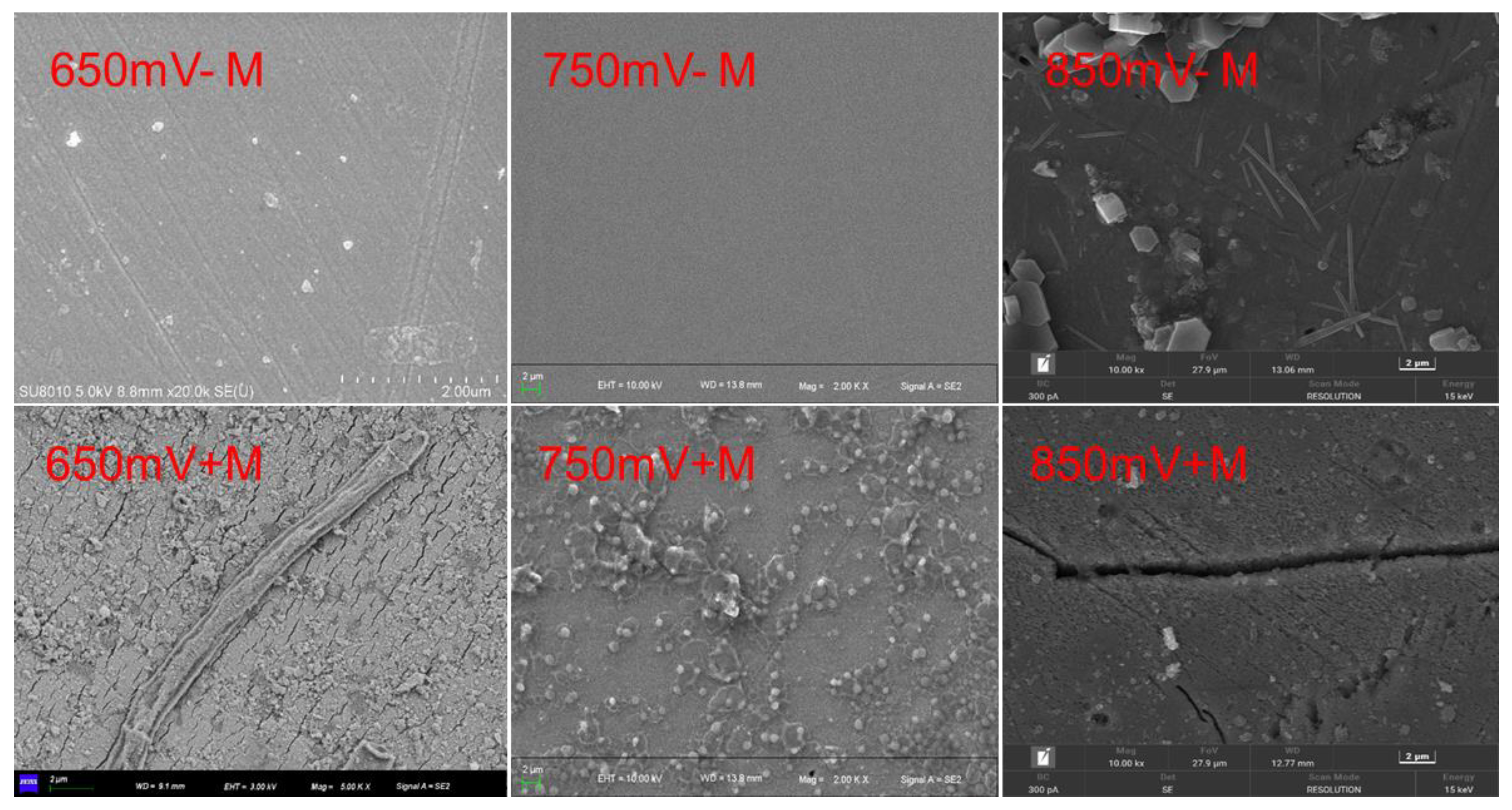

The morphology of chalcopyrite residues was imaged by SEM, as shown in

Figure 3. It was reported that two suitable redox potential range exist during chalcopyrite leaching process: the low potential leaching interval (550 mV to 680 mV, vs. SHE) and the high potential leaching interval (greater than 820 mV, vs. SHE) [

22]. And between 680 mV and 820 mV, the passive effect will decrease the chalcopyrite leaching. Morphological analysis showed that the corrosion degree of chalcopyrite in the suitable redox potentials was higher than that outside the passive redox potential. At each redox potential, regardless of whether microorganisms were sessile, the corrosion on the chalcopyrite surface was similar. Small cracks and pores were observed at 650 mV, with an average channel width of about 0.2 μm. At 850 mV, severer corrosion occurred, with an average channel width of about 0.8 μm. At 750 mV, the chalcopyrite surface was smoother than the other two redox potentials. The cracks formed when microorganisms were attached were slightly wider than when no microorganisms were present, suggesting that microorganisms can accelerate chalcopyrite leaching.

3.2. Copper Leaching Kinetics

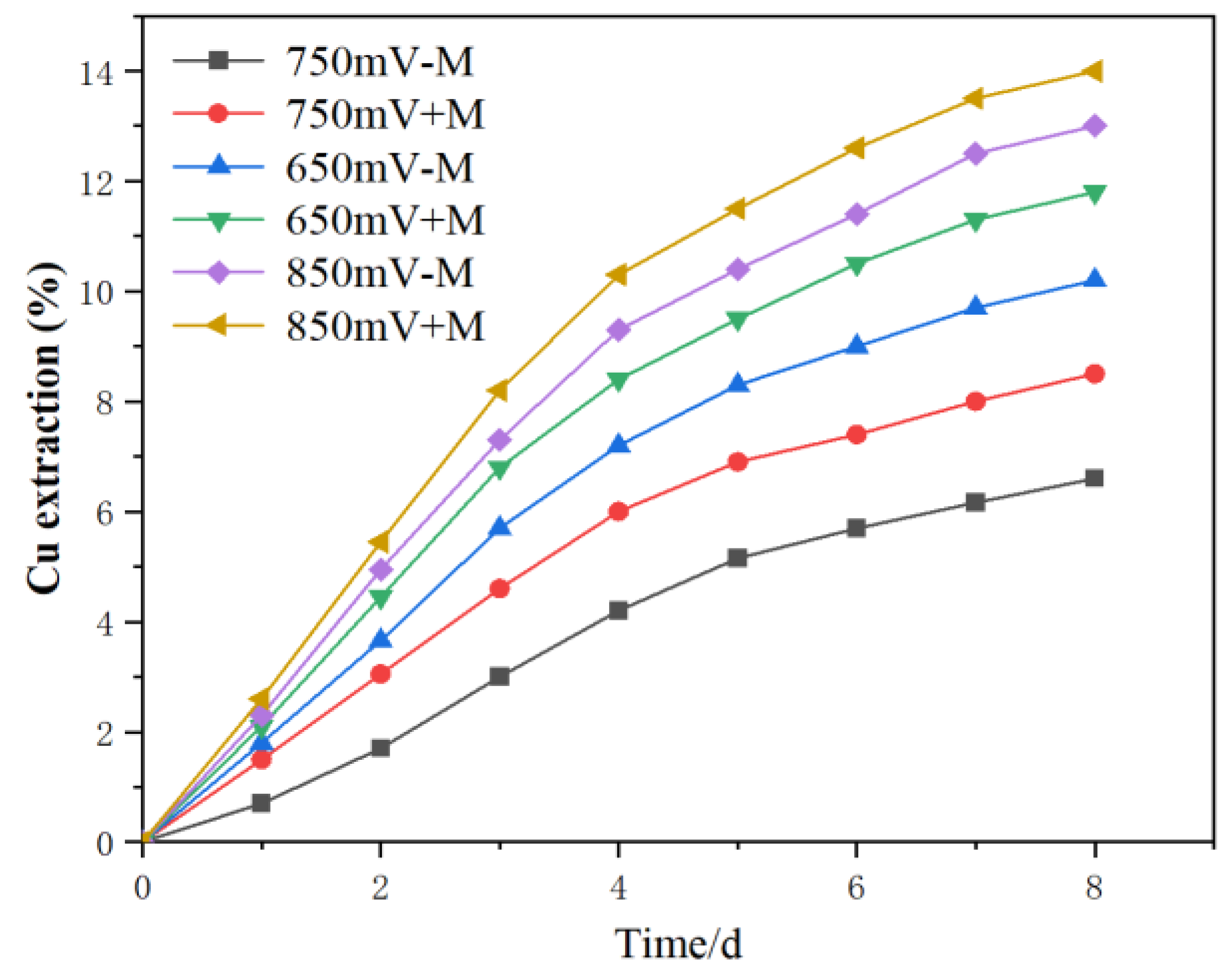

Figure 4.

Chalcopyrite leaching kinetics with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

Figure 4.

Chalcopyrite leaching kinetics with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

No matter microorganisms were attached onto chalcopyrite or not, the redox potential had a significant impact on the leaching of chalcopyrite. When the solution potential was at 850 mV and 650 mV, the chalcopyrite leaching rate was higher, while at 750 mV, the leaching rate was slower. This was in accordance with the morphology image. This results was in accordance with these previous researches that between about 680-720 mV, passive layer formed, thus decrease the chalcopyrite leaching rate [

2,

9]. This mean that the ferrous oxidizing microbes not always promote the leaching, sometimes may inhibit the leaching kinetics if the redox potential fall to the redox potential of 680-720 mV (redox potential is mainly determined by Fe

2+/Fe

3+ ratio). In the absence of sessile acidophiles, where only iron ions are acting on the surface, the leaching rate can represent the contribution of the "non-contact leaching". The kinetics obtained by subtracting the leaching rate with attached acidophiles from the rate without attached microorganisms at the same redox potential represented the contribution of the "contact leaching" of the attached microorganisms. So the extent of chalcopyrite kinetics increase in the treatment with contacted leaching than the treatments without contact leaching reflected the promoting effect of the contact microbes. Results suggested that both the contact and non-contact mechanism contributes to the chalcopyrite oxidation.

3.3. Chalcopyrite Residue Surface Component Assay

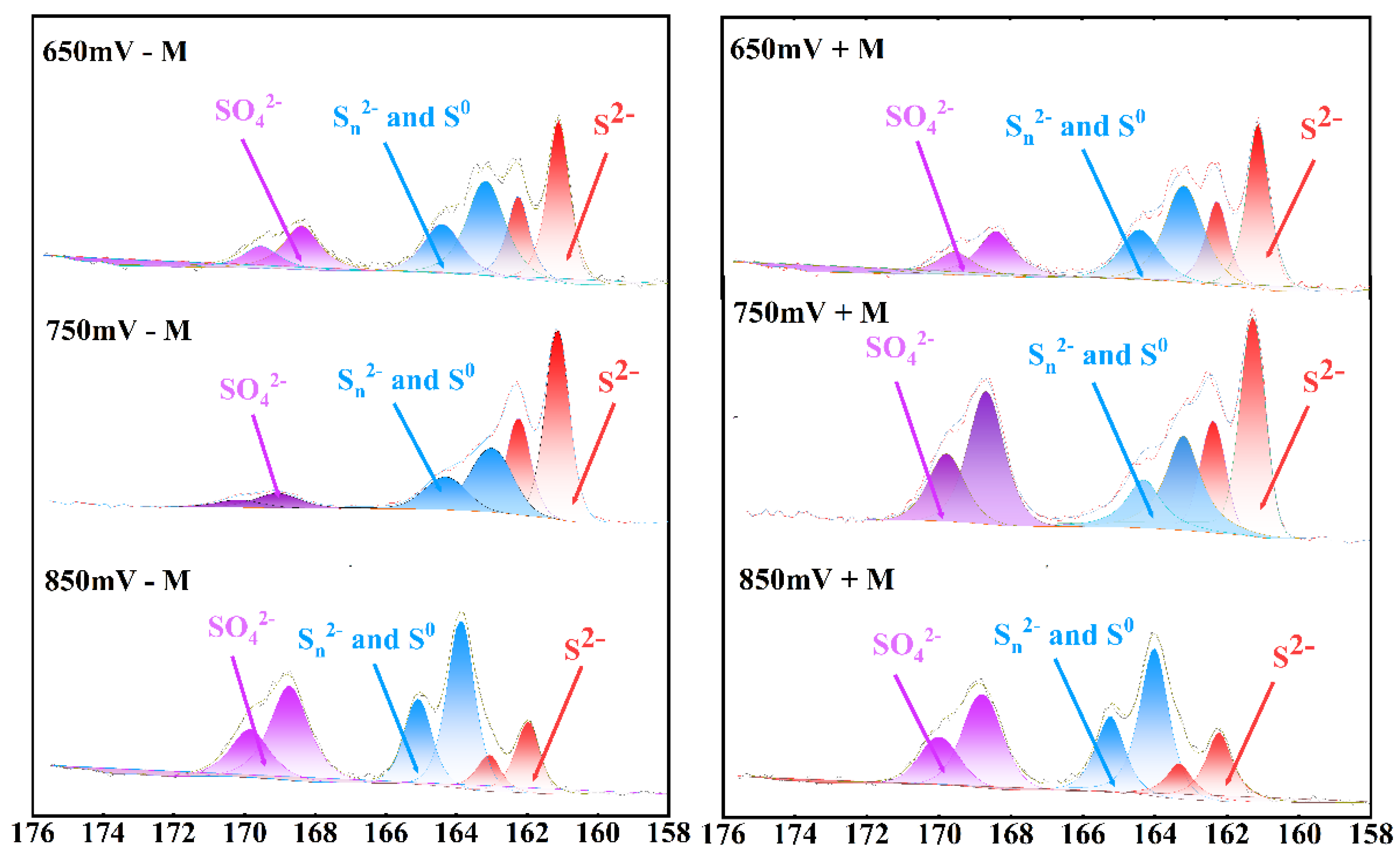

The sulfur S 2p spectra of the leach residue were shown in

Figure 5. The fitting peak with a binding energy of 161.1-161.8 eV in the S 2p3/2 region corresponds to S

2- in the surface phase of chalcopyrite, the binding energy of 163.0-164.7 eV corresponds to polysulfides and elemental sulfur in the surface phase of chalcopyrite, and the binding energy of 168.0-169.0 eV corresponds to SO

42- from the post-experiment solution [

23].

The percentage of various sulfur species under different redox potential conditions after the experiments were shown in

Table 1. When the redox potential of the solution is at 750 mV, compared to the condition with sessile microbes, the amount of elemental sulfur on the chalcopyrite residue surface was significantly higher than when there are no sessile microbes. This observation indicated that sessile microbes can metabolize elemental sulfur, thereby accelerating the leaching efficiency of chalcopyrite. Percentage of Sn

2- and S

0 were about 10 percent lower in the treatment with contact microbes than that without contact microbes.

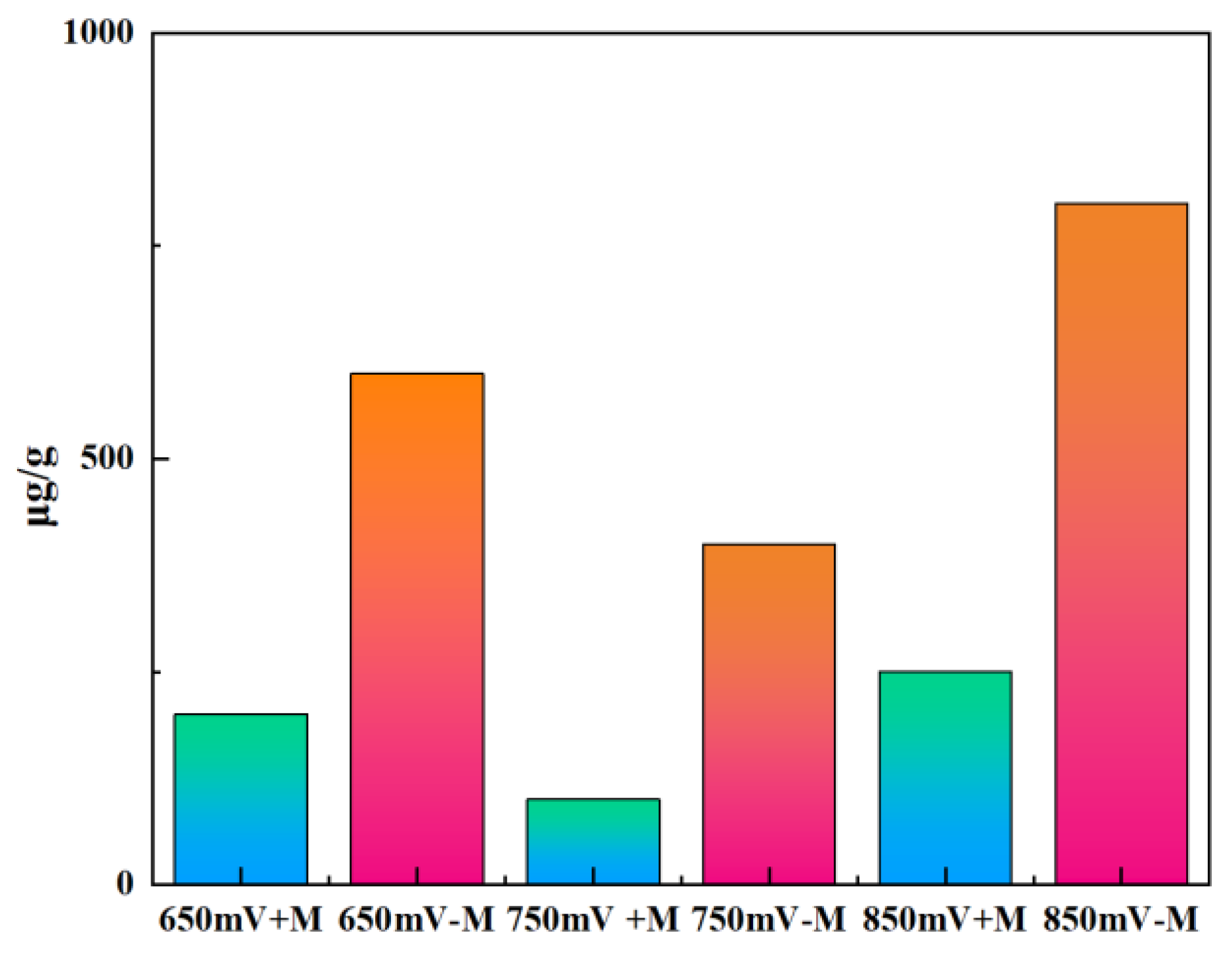

XPS has limitations in precisely measuring of elemental sulfur content, whereas high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) can more accurately quantify the amount (

Figure 6). In the oxidation process of chalcopyrite, the first sulfur-containing ion released is the thiosulfate ion (S

2O

32-). S

2O

32- then generates unstable intermediate substances during the oxidation process, but ultimately transforms into elemental sulfur (S

0) and sulfate (SO

42-) [

24,

25]. Under the redox potential at 650 mV, 750 mV and 850 mV, when no microbes sessile, each gram of chalcopyrite residue contains about 600, 400 and 800 μg of elemental sulfur, respectively. These results suggest that in the absence of adsorbed microbes, the oxidation rate at different redox potentials were positively correlated with the amount of elemental sulfur generated. Taking the 750 mV potential as an example, with the contact microbes, the elemental sulfur content on each gram of chalcopyrite residue was only about 25% than the treatment with no contact microbes. Similar situations also occur at potentials of 650 mV and 850 mV. This indicates that the elemental sulfur generated during the chalcopyrite leaching process was oxidized by the sessile microbes.

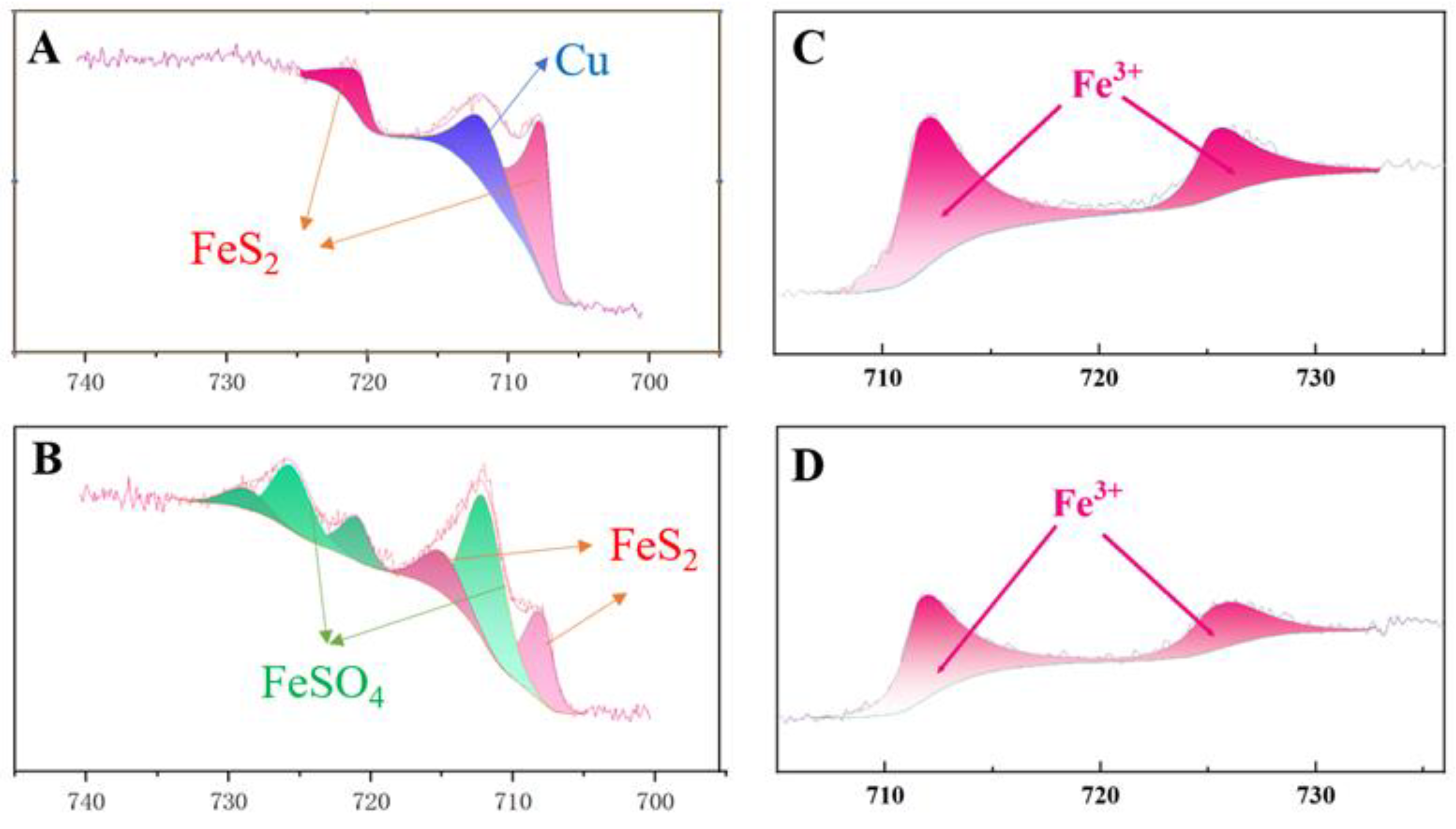

The Fe 2p3/2 spectra of the leached fine residue and ore cubes were shown in

Figure 7, and the species composition of iron in the leach residue were presented in

Table 2. The splitting peaks at 707 eV and 708.0 eV correspond to the FeS

2 phase in the chalcopyrite matrix, while the splitting peak at 712.0 eV corresponds to FeSO

4 in chalcopyrite. Additionally, the fitting peak at a binding energy of 711.0 eV indicates the presence of Fe

3+ [

26]. Under constant potential conditions, the valence state of iron on the chalcopyrite surface did not undergo significant changes, regardless of the presence of contact microbes. The iron in the leached residue existed in the form of Fe (II), while the iron in the ore cubes existed in the form of Fe (III). This was because the ore cubes have a smaller contact area compared to the leach residue, produced less secondary products and secondary products. Previous researchers had pointed out that contact microbes promoted the leaching of chalcopyrite by inhibiting the formation of jarosite on the chalcopyrite surface [

27]. While in this study the contact microbes did not significantly influence the formation of secondary minerals, may because the pH during the leaching is about 1.3, while low pH is not suitable for jarosite formation [

28,

29].

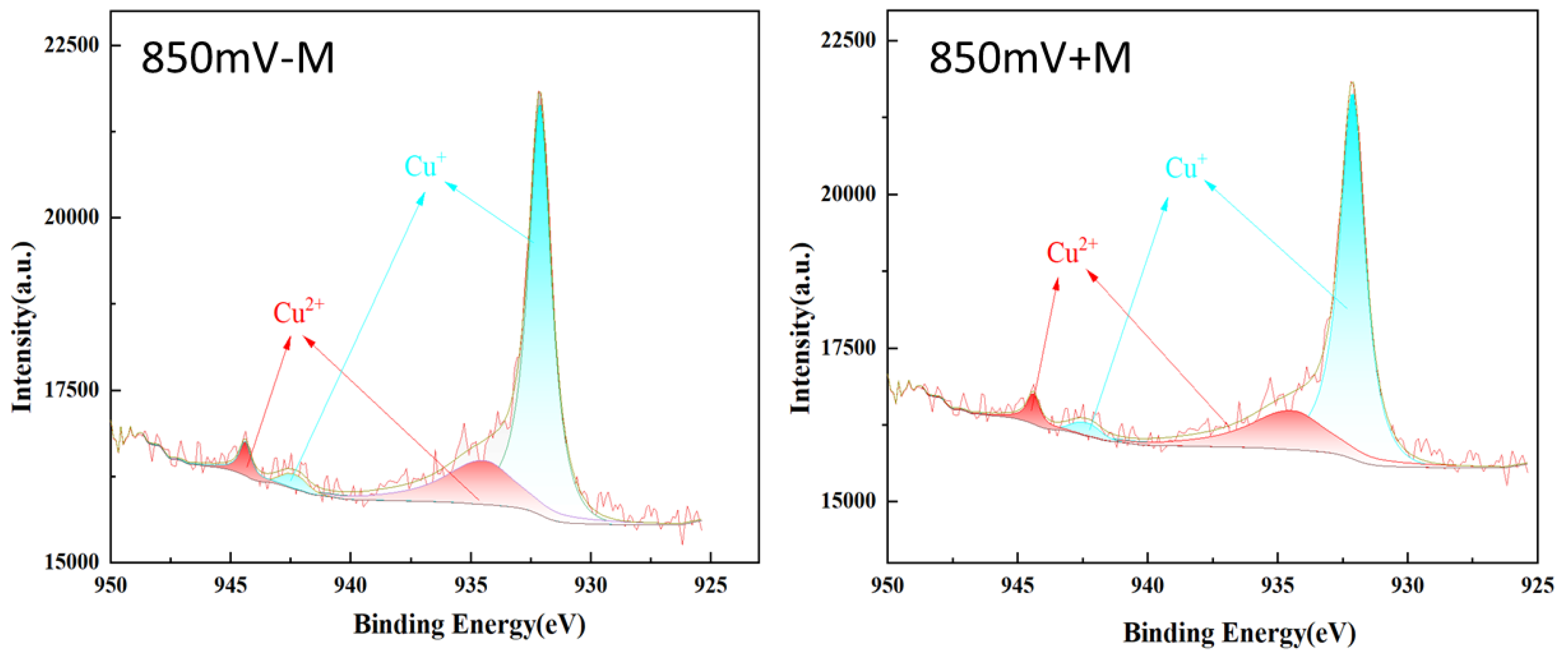

The Cu 2p spectra of the chalcopyrite cube’s surface were shown in

Figure 8. Under constant redox potential, the proportion of Cu (II) and Cu (I) in the ore pieces is stable, and the presence of microbes had little effect on the copper species and contents. It was reported that the Cu ion in chalcopyrite crystal was mainly Cu

+ [

24,

30], the Cu

2+ here may also include some oxidized Cu on the chalcopyrite surface.

It was suggested that the contact microbes did not fundamentally alter the leaching mechanism of chalcopyrite. When analyzing the leaching rate in combination with these surface testing, under constant "non-contact" conditions, microbial "contact" action promoted chalcopyrite leaching, and the microbial "contact" action mainly eliminates the intermediate sulfur at the reaction interface. It was reported that the oxidation of Fe

3+ could happen on the membranes, while the oxidation of sulfur more need the transportation of sulfur into the microbe’s membranes [

7]. Also the element sulfur was not dissolved in the solution, so it was more likely absorbed on the mineral surface, thus the contact leaching was more important for sulfur. The EPS help the sessile of the microbes to the minerals, and the contact with the sulfur compounds [

31].

Table 3.

Composition and proportion of Cu 2p valence states on the surface of chalcopyrite at 850 mV (vs. SHE) with or without contact microbes (+M, -M).

Table 3.

Composition and proportion of Cu 2p valence states on the surface of chalcopyrite at 850 mV (vs. SHE) with or without contact microbes (+M, -M).

| |

850mV + M |

850mV - M |

| Species |

At.% |

At.% |

| Cu+

|

76.05 |

77.46 |

| Cu2+

|

23.95 |

22.54 |

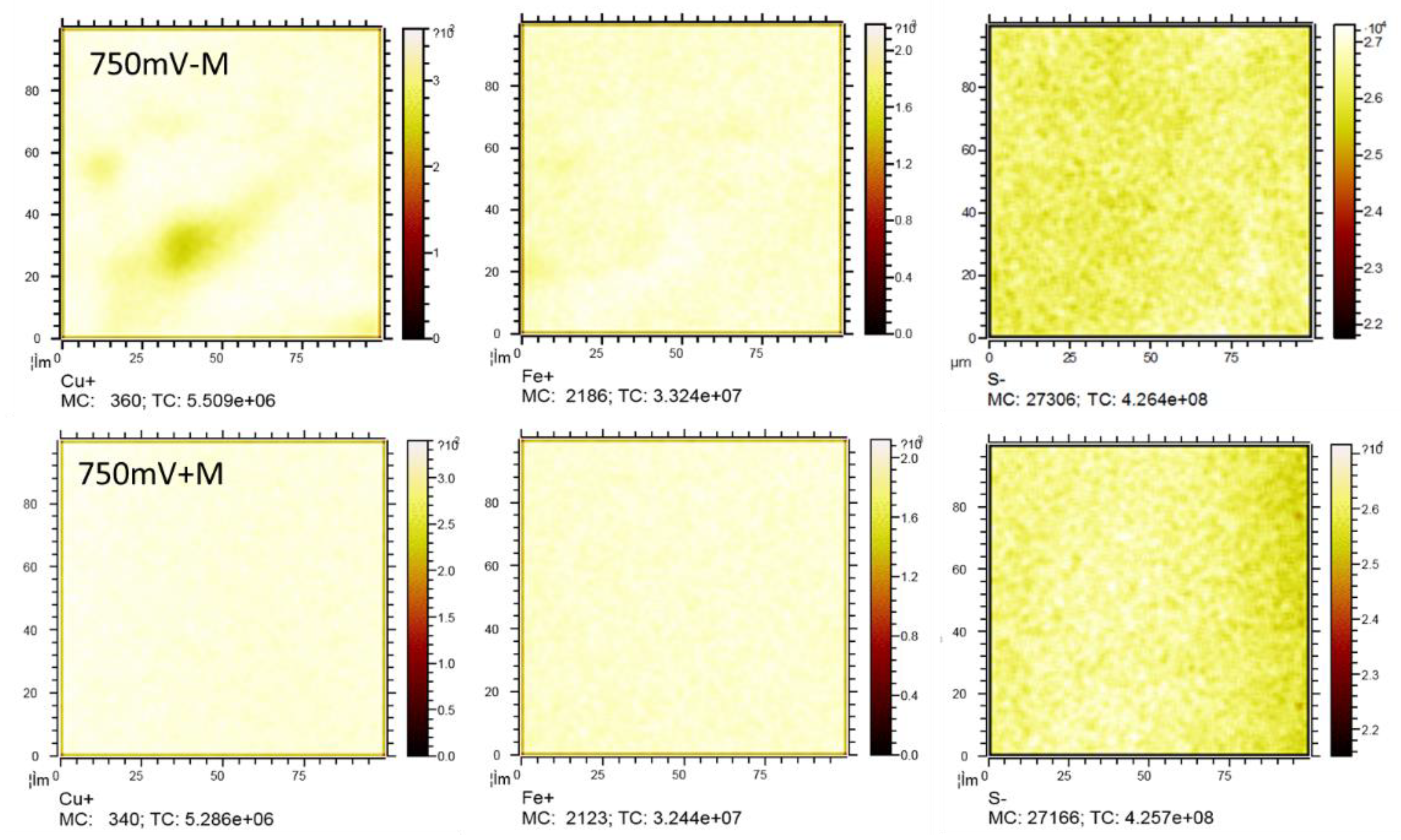

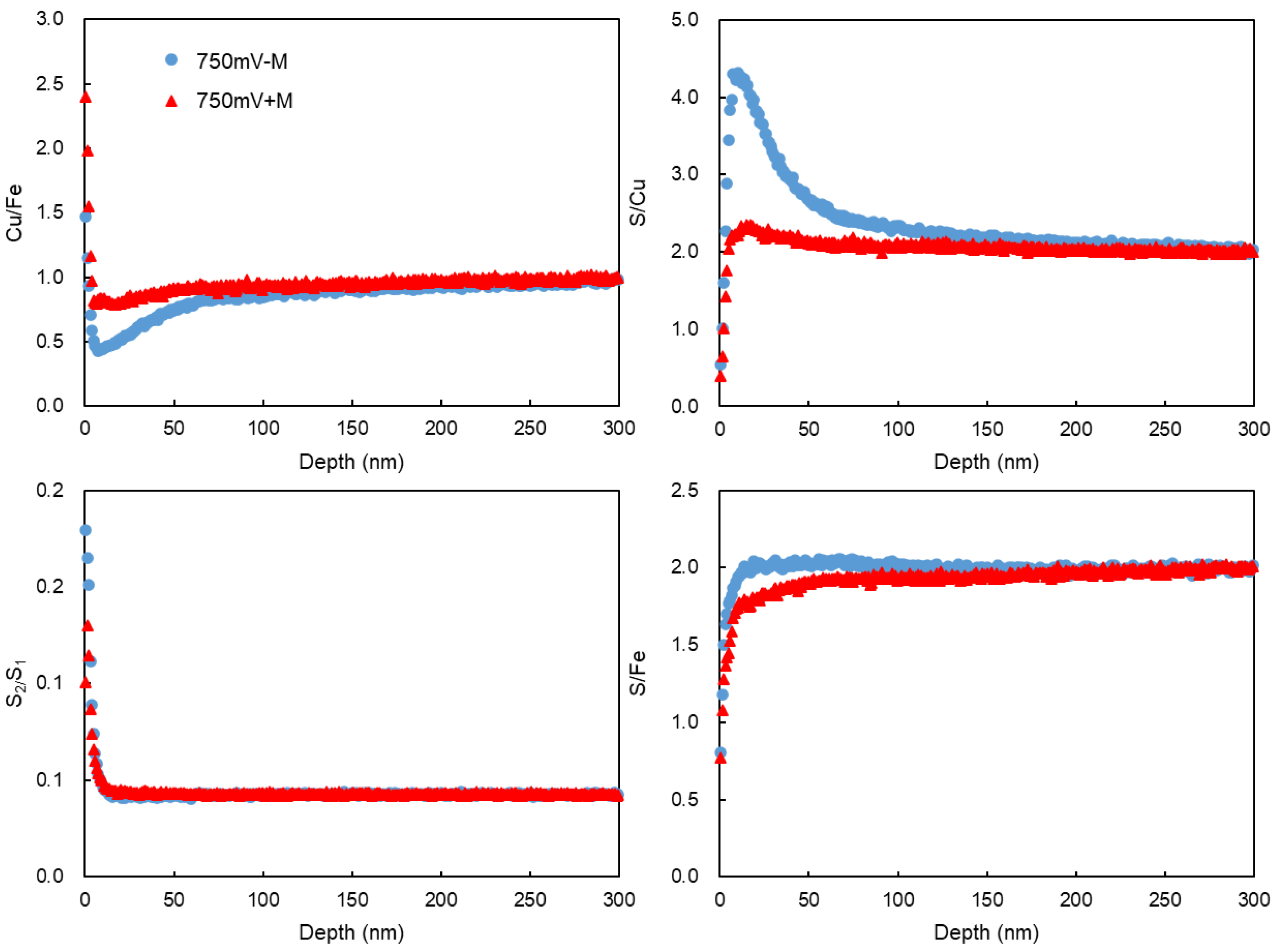

3.4. Chalcopyrite Elemetal Distribution Assay by ToF-SIMS

ToF-SIMS provided the elemental distribution of copper, iron and sulfur in different depth on the surface of the leached chalcopyrite cubes. The Cu and Fe distribution was analyzed in the positive ion mode, while the sulfur species were analyzed in the negative ion mode at a range of 100 μm × 100 μm area (

Figure 9). The Cu/Fe ration for the leached chalcopyrite were normalized against a freshly polished sample where the Cu/Fe ratio was assumed to be 1 across the entire range of depth (

Figure 10). In the very surface of few nm rage, maybe it was influenced by the absorbed Cu and Fe ion on the cubes, and below a few nm, it showed the reacted layer of the chalcopyrite cubes. At the depth < 60 nm, Cu/Fe ratio in the treatment without contact microbes was lower than that with the contact microbes. According to the S/Cu and S/Fe ratio, it showed that the treatment without sessile microbes had more sulfur than the treatment that with sessile microbes. The S/Cu and S/Fe ratio finally all showed to a final ratio of about 2, showed the crystal bulk which has not react at about > 100 nm depth.

Leached mineral samples with major peaks belonging to sulfur species at m/z = 32 and 64. Previous work had demonstrated that the intensity ratio of S2/S1 can be used to illustrate the extent of polymerization of sulfide species [

1,

32], although, few amounts of S3, S4 and S5 were also detected. With the sputter depth increasing, the S2/S1 came to a constant ratio. Unlike in positive mode where the Cu/Fe ratio can be assumed to be 1 for a fresh sample, there is no standard ratio for S2/S1 for pure chalcopyrite, thus the numerical value of the normalized S2/S1 intensity ratio does not have physical significance. A higher S2/S1 ratio was measured on the non-contact leaching chalcopyrite surface than the contact leaching, suggesting that the surface species on the non-contact leached surface have a higher degree of sulfur polymerization. This result together with previous XPS and HPLC results, proved the elimination of intermediate sulfur compounds by the contact microbes.

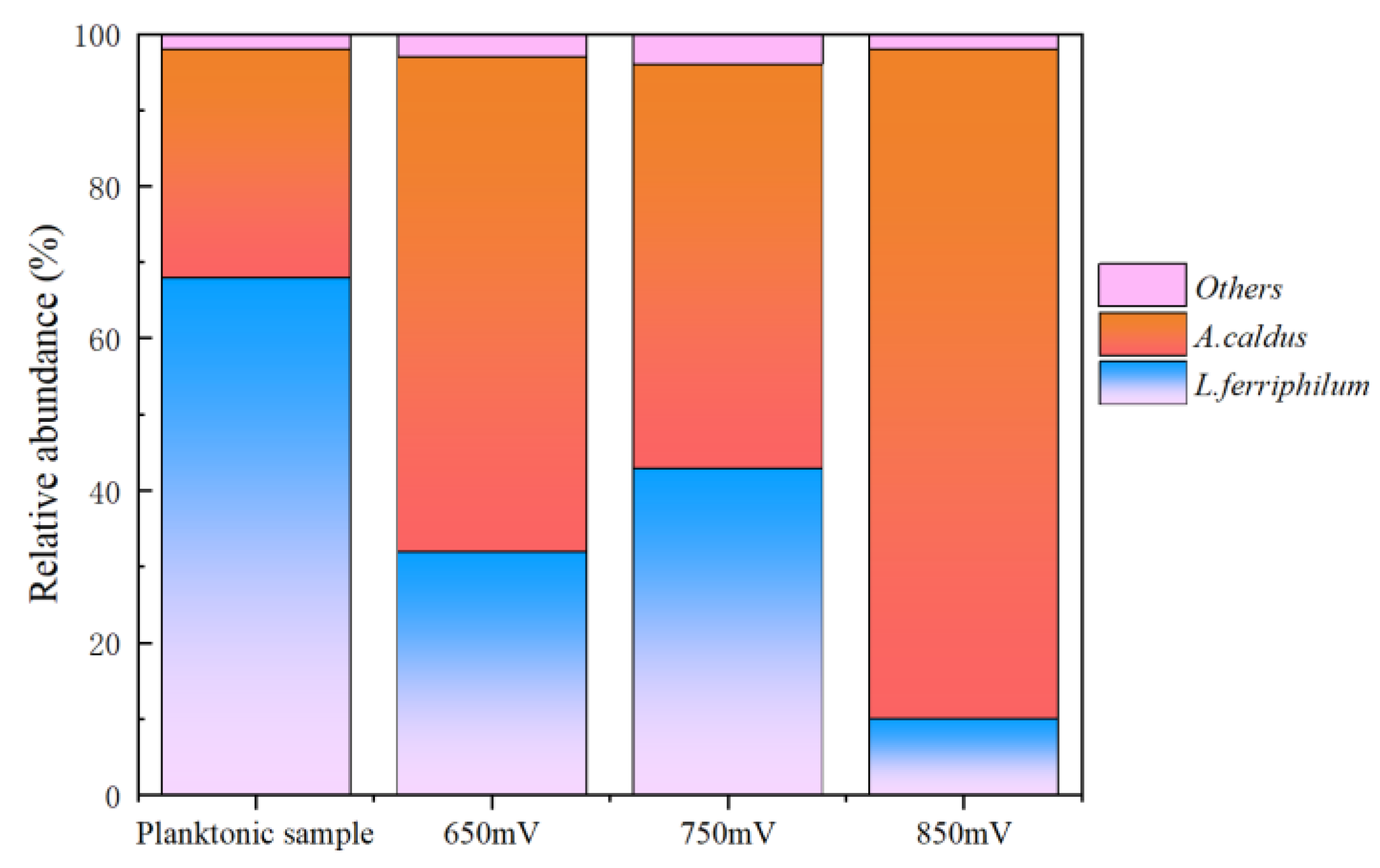

3.5. Microbial Community in Chalcopyrite Residue

Composition study of sessile microbes helped understand their role in copper sulfide ore leaching. It was found that the population mainly consisted of two types of microorganisms. The dominant microbial species in the inoculated population was the iron-oxidizing bacterium L. ferriphilum, accounting for approximately 70%. This microorganism can only use Fe2+ as an energy source. The sulfur-oxidizing bacterium was A. caldus, accounting for about 30%. This microorganism can only use reduced sulfur as an energy source and cannot utilize sulfide minerals directly as energy. Other microorganisms accounting for less than 4%.

As shown in

Figure 11, significant changes were observed in the adsorbed microbial population compared to the initial inoculated microbial population. Under these three different redox potential conditions, the abundance of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria

A. caldus on the copper sulfide ore residue surface was significantly higher than their abundance in the solution. At the solution redox potential of 650 mV, 750 mV and 850 mV, the proportion of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria on the residue surface was increased to 65%, 53% and 88% respectively, much higher than that in the solution as inoculated. This finding suggests that elemental sulfur generated during copper sulfide ore leaching can promote the abundance of sulfur-oxidizing bacterium on the residue surface.

The effects of pure and mixed microbial strains on the copper sulfide ore leaching process have been widely studied [

7]. Research showed that copper sulfide ore can be oxidized by microorganisms with iron-oxidizing ability [

33,

34], as these microorganisms can oxidize Fe

2+ to Fe

3+, and Fe

3+ acts as an important oxidizing agent in acidic solutions. The sulfur-oxidizing microorganism, such as

A. caldus, which mainly possesses sulfur-oxidizing abilities, has been confirmed not to directly participate in the oxidation of copper sulfide ore [

35,

36]. Nevertheless, the addition of sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms can significantly accelerate the oxidation rate of copper sulfide ore by mixed microorganisms, further proving that sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms play an indirect promoting role in the oxidation process of copper sulfide ore [

37,

38]. The mechanism behind this phenomenon is that

A. caldus can eliminate the passivation effect caused by the sulfur layer on the surface of copper sulfide ore [

39]. In addition, as the proportion of sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms in the microbial community increases, their overall sulfur-oxidizing ability also enhances [

40,

41].

All the microbes, no matter sessile microbes or planktonic microbes, they all act as the indirect effect on chalcopyrite leaching. In this study, the redox potential was manually controlled, which cannot reflect the actual contribution of microbial ferrous oxidation. It was assumed that the microbes on mineral surface was much higher than that in the solution during bioleaching, so the sessile microbes may also contribute a lot to the solution redox potential. These results suggest that the "non-contact mechanism", i.e., mainly the regeneration of oxidizing agents by microorganisms and their influence on the potential, also played a significant role in the leaching of chalcopyrite; the "contact mechanism" of attached microorganisms, i.e., mainly sulfur oxidation, promotes chalcopyrite oxidation. Similar mechanism has been proved in pyrite bioleaching [

13,

14]. The difference is that pyrite and chalcopyrite had different favored redox potential. For pyrite, higher redox potential resulted to higher leaching rate [

42], so microbial ferrous oxidizing activity is favorable; while for chalcopyrite, the passivation redox potential was around 680-750 mV [

24], that mean lower and higher ferrous oxidation activity was favorable, but not a medium activity.

4. Conclusion

This study using a novel device, investigated the contribution and mechanism of sessile microbes on the bioleaching of chalcopyrite, under the different controlled redox potentials (to simulate the different constant non-contact effects). It clearly separated and quantified the contact and non-contact leaching, as well as the mechanism in related to the function of ferrous and sulfur oxidizing microbes. The bioleaching rate of chalcopyrite was significantly related to the solution redox potential, followed by 850 mV > 650 mV > 750 mV, regardless of the presence of sessile microbes or not. In the bioleaching system, the redox potential is determined mainly by the ferrous oxidizing activity, mainly representing the non-contact microbes. When compared with the bioleaching with only non-contact microbes, the chalcopyrite bioleaching kinetics were higher in the treatments with the contact and non-contact microbes together, it suggested the contribution of the contact leaching. It proved by different analytic tools that the contact microbes were mainly the sulfur oxidizing microbes rather than ferrous oxidizing microbes, which helped elimination of the intermediate sulfur compounds. It also gave implications to the industrial chalcopyrite bioleaching in related to bioleaching microbial cultivation and regulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.; methodology, Q.Y.; validation, R.R. and J.Q.; formal analysis, Q.T.; investigation, Q.Y.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, Q.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.J. and J.J.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, Y.J. and C.Z; funding acquisition, Y.J. and J.Q.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA0430304) and Youth Scientist Project of the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFC2815600).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ren, Z.H.; Chao, C.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Heise, C.; Sabzehei, K.; Asselin, E.; Dixon, D.G.; Mora, N. New perspective on the depassivation mechanism of chalcopyrite by ethylene thiourea. Miner. Eng. 2023, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.Y.; Li, H.D.; Wei, Q.; Qin, W.Q.; Yang, C.R. Effects of redox potential on chalcopyrite leaching: An overview. Miner. Eng. 2021, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Schippers, A.; Hedrich, S.; Sand, W. Progress in bioleaching: fundamentals and mechanisms of microbial metal sulfide oxidation-part A. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2022, 106, 7375–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez-Yevenes, L.; Malverde, S.; Quezada, V. A Sustainable Bioleaching of a Low-Grade Chalcopyrite Ore. Minerals-Basel 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, W.; Schippers, A.; Hedrich, S.; Vera, M. Progress in bioleaching: fundamentals and mechanisms of microbial metal sulfide oxidation - part A. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2022, 106, 6933–6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Xie, L.; Han, L.B.; Wang, X.G.; Wang, J.M.; Zeng, H.B. In-situ probing of electrochemical dissolution and surface properties of chalcopyrite with implications for the dissolution kinetics and passivation mechanism. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2021, 584, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Tan, Q.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.P.; Gao, H.S.; Ruan, R. Sulfide mineral dissolution microbes: Community structure and function in industrial bioleaching heaps. Green Energy Environ. 2019, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.C.; Yang, H.Y.; Luan, Z.C.; Sun, Q.F.; Ali, A.; Tong, L.L. Leaching of chalcopyrite under bacteria-mineral contact/noncontact leaching model. Minerals-Basel 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yuan, W.B.; Jin, K.; Zhang, Y.S. Control of the redox potential by microcontroller technology: researching the leaching of chalcopyrite. Minerals-Basel 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, A.; Jozsa, P.G.; Sand, W. Sulfur chemistry in bacterial leaching of pyrite. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1996, 62, 3424–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.P.; Ehrlich, H.L. Microbial formation and degradation of minerals. In Advances in Applied Microbiology, Umbreit, W.W., Ed.; Academic Press: 1964; Volume 6, pp. 153-206.

- Attia, Y.A.; Elzeky, M.A. Bioleaching of nonferrous sulfides with adapted thiophilic bacteria. Chem Eng J Bioch Eng 1990, 44, B31–B40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jia, Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Tan, Q.Y.; Niu, X.P.; Leng, X.K.; Ruan, R.M. Limited role of sessile acidophiles in pyrite oxidation below redox potential of 650 mV. Sci Rep-Uk 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.X.; Jia, Y.; Tan, Q.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Ruan, R.M. Contributions of microbial "contact leaching" to pyrite oxidation under different controlled redox potentials. Minerals-Basel 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, W.; Gehrke, T.; Jozsa, P.G.; Schippers, A. (Bio) chemistry of bacterial leaching - direct vs. indirect bioleaching. Hydrometallurgy 2001, 59, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.X.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, H.P.; Tan, Q.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Jiang, C.Y.; Ruan, R.M. Evidence of weak interaction between ferric iron and extracellular polymeric substances of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, A.; Sand, W. Bacterial leaching of metal sulfides proceeds by two indirect mechanisms via thiosulfate or via polysulfides and sulfur. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1999, 65, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.M.; Liu, Z.R.; Liao, W.Q.; Cheng, J.J.; Wu, X.L.; Qiu, G.Z.; Shen, L. Distribution and content changes of extracellular polymeric substance and iron ions on the pyrite surface during bioleaching. J. Cent. South. Univ. 2023, 30, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Chen, D.F.; Gao, H.S.; Ruan, R.M. Characterization of microbial community in industrial bioleaching heap of copper sulfide ore at Monywa mine, Myanmar. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 164, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Tan, Q.Y.; Xu, J.Y.; Feng, X.L.; Ruan, R.M. Industrial heap bioleaching of copper sulfide ore started with only water irrigation. Minerals-Basel 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.P.; Chen, J.H.; Li, Y.Q.; Xia, L.Y.; Li, L.; Sun, H.Y.; Ruan, R. Correlation of surface oxidation with xanthate adsorption and pyrite flotation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.T.; Liao, R.; Yang, B.J.; Yu, S.C.; Wu, B.Q.; Hong, M.X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.B.; Gan, M.; Jiao, F.; et al. Role and maintenance of redox potential on chalcopyrite biohydrometallurgy: An overview. J. Cent. South. Univ. 2020, 27, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Tan, Q.Y.; Jia, Y.; Shu, R.B.; Zhong, S.P.; Ruan, R.M. Pyrite oxidation in column at controlled redox potential of 900 mV with and without bacteria. Rare Metals 2022, 41, 4279–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.B.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhang, X.; Qian, L.; Sun, M.L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.S.; Wang, J.; Kim, H.; Qiu, G.Z. The dissolution and passivation mechanism of chalcopyrite in bioleaching: An overview. Miner. Eng. 2019, 136, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrizac, J.E. Elemental sulfur formation during the ferric-chloride leaching of chalcopyrite. Hydrometallurgy 1990, 23, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.F.; Pan, Y.G.; Xue, J.Y.; Sun, Q.F.; Su, G.Z.; Li, X. Comparative XPS study between experimentally and naturally weathered pyrites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8750–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okibe, N.; Johnson, D.B. Biooxidation of pyrite by defined mixed cultures of moderately thermophilic acidophiles in pH-controlled bioreactors: significance of microbial interactions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 87, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Tao, X.X.; Cai, P. Study of formation of jarosite mediated by thiobacillus ferrooxidans in 9K medium. Proceedings of the International Conference on Mining Science & Technology (Icmst2009) 2009, 1, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.L.; Gu, G.H.; Wang, X.H.; Yan, W.; Qiu, G.Z. Study on the jarosite mediated by bioleaching of pyrrhotite using Acidthiobacillus Ferrooxidans. Biosci. J. 2017, 33, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, D.; Singru, R.M.; Biswas, A.K. Study of the roasting of chalcopyrite minerals by Fe-57 Mossbauer spectroscopy. Miner. Eng. 2000, 13, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.L.; Ou, Y.; Tan, J.X.; Wu, F.D.; Sun, J.; Miao, L.; Zhong, D.L. Effect of EPS on adhesion of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans on chalcopyrite and pyrite mineral surfaces. T Nonferr Metal Soc 2011, 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisener, C.G.; Smart, R.S.C.; Gerson, A.R. Kinetics and mechanisms of the leaching of low Fe sphalerite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2003, 67, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Wang, R.C.; Lu, X.C.; Lu, J.J.; Li, C.X.; Li, J. Bioleaching of chalcopyrite by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Miner. Eng. 2013, 53, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, X.C.; Zhang, L.J.; Xiang, W.L.; Zhu, X.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.L.; Lu, J.J.; Wang, R.C. Collaborative effects of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and ferrous ions on the oxidation of chalcopyrite. Chem. Geol. 2018, 493, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.S.; Qiu, Y.K.; Huang, Z.Z.; Yin, Y.J.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhu, D.Q.; Tong, Y.J.; Yang, H.L. The adaptation mechanisms of Acidithiobacillus caldus CCTCC M 2018054 to extreme acid stress: Bioleaching performance, physiology, and transcriptomics. Environ. Res. 2021, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuna, L.G.; Cardenas, J.P.; Covarrubias, P.C.; Haristoy, J.J.; Flores, R.; Nunez, H.; Riadi, G.; Shmaryahu, A.; Valdes, J.; Dopson, M.; et al. Architecture and gene repertoire of the flexible genome of the extreme acidophile Acidithiobacillus caldus. Plos One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.Y.; Wang, X.J.; Feng, X.; Liang, Y.L.; Xiao, Y.H.; Hao, X.D.; Yin, H.Q.; Liu, H.W.; Liu, X.D. Co-culture microorganisms with different initial proportions reveal the mechanism of chalcopyrite bioleaching coupling with microbial community succession. Bioresource Technol. 2017, 223, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, L.A.; Watling, H.R.; Watkin, E.L.J. Microbial population dynamics of inoculated low-grade chalcopyrite bioleaching columns. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 104, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.Z.; Feng, S.S.; Tong, Y.J.; Yang, H.L. Enhanced "contact mechanism" for interaction of extracellular polymeric substances with low-grade copper-bearing sulfide ore in bioleaching by moderately thermophilic Acidithiobacillus caldus. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 242, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Xia, J.L.; Yang, Y.; Nie, Z.Y.; Zheng, L.; Ma, C.Y.; Zhang, R.Y.; Peng, A.A.; Tang, L.; Qiu, G.Z. Sulfur oxidation activities of pure and mixed thermophiles and sulfur speciation in bioleaching of chalcopyrite. Bioresource Technol. 2011, 102, 3877–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, B.J.; Zhu, J.Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.K.; Zhang, R.Y.; Sand, W. Comparative analysis of attachment to chalcopyrite of three mesophilic iron and/or sulfur-oxidizing acidophiles. Minerals-Basel 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Chen, M.; Zou, L.C.; Shu, R.B.; Ruan, R.M. Study of the kinetics of pyrite oxidation under controlled redox potential. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 155, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Surface morphology by SEM detecting of chalcopyrite cubes after leaching with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

Figure 2.

Surface morphology by SEM detecting of chalcopyrite cubes after leaching with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

Figure 5.

Sulfur 2p XPS spectra on the surface of chalcopyrite residue after leaching with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

Figure 5.

Sulfur 2p XPS spectra on the surface of chalcopyrite residue after leaching with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

Figure 6.

Elemental sulfur contents of chalcopyrite residue at different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)) with or without contact microbes (+M, -M).

Figure 6.

Elemental sulfur contents of chalcopyrite residue at different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)) with or without contact microbes (+M, -M).

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of Fe 2p on the surface of chalcopyrite residue after leaching at 750 mV (vs. SHE). A: without contact microbes of the fine chalcopyrite; B: with contact microbes of the fine chalcopyrite; C: without contact microbes of the chalcopyrite cubes; D: with contact microbes of the chalcopyrite cubes.

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of Fe 2p on the surface of chalcopyrite residue after leaching at 750 mV (vs. SHE). A: without contact microbes of the fine chalcopyrite; B: with contact microbes of the fine chalcopyrite; C: without contact microbes of the chalcopyrite cubes; D: with contact microbes of the chalcopyrite cubes.

Figure 8.

Cu 2p XPS spectra of chalcopyrite after leaching at 850 mV (vs. SHE) with or without contact microbes (+M, -M).

Figure 8.

Cu 2p XPS spectra of chalcopyrite after leaching at 850 mV (vs. SHE) with or without contact microbes (+M, -M).

Figure 9.

Surface Cu, Fe and S distribution of the reacted chalcopyrite surface with or without contacted microbes under 750 mV (vs. SHE).

Figure 9.

Surface Cu, Fe and S distribution of the reacted chalcopyrite surface with or without contacted microbes under 750 mV (vs. SHE).

Figure 10.

Surface Cu, Fe and S distribution of the reacted chalcopyrite surface with or without contacted microbes under 750 mV (vs. SHE).

Figure 10.

Surface Cu, Fe and S distribution of the reacted chalcopyrite surface with or without contacted microbes under 750 mV (vs. SHE).

Figure 11.

Communities of the inoculated microbes and sessile microbes on chalcopyrite surface at different redox potentials.

Figure 11.

Communities of the inoculated microbes and sessile microbes on chalcopyrite surface at different redox potentials.

Table 1.

Species and contents of sulfur on the surface of chalcopyrite residue after leaching with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

Table 1.

Species and contents of sulfur on the surface of chalcopyrite residue after leaching with or without contact microbes (+M, -M) under different redox potentials (650, 750, 850 mV (vs. SHE)).

| |

650mV - M |

650mV + M |

750mV - M |

750mV + M |

850mV - M |

850mV + M |

| Species |

At.% |

At.% |

At.% |

At.% |

At.% |

At.% |

| S22-

|

53.88 |

52.04 |

56.85 |

52.40 |

17.27 |

21.01 |

| Sn2-/S0

|

39.12 |

28.7 |

34.66 |

25.65 |

45.76 |

34.86 |

| SO42-

|

6.98 |

19.26 |

8.49 |

21.95 |

36.97 |

44.13 |

Table 2.

Composition and proportion of Fe 2p valence states on the chalcopyrite surface after leaching at 750 mV (vs. SHE) with or without contact microbes.

Table 2.

Composition and proportion of Fe 2p valence states on the chalcopyrite surface after leaching at 750 mV (vs. SHE) with or without contact microbes.

| |

750 mV - M |

750 mV + M |

| Species |

At. % |

At. % |

| FeS2

|

100 |

28.6 |

| FeSO4

|

0 |

71.4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).