1. Introduction

Hypnosis is a state of focused attention and heightened suggestibility, where individuals become absorbed in internal experiences such as thoughts, emotions, and mental imagery. During hypnotic induction, concentration and imagination are engaged so intensely that imagined experiences can feel real (Williamson, 2019). Cognitive models of hypnosis suggest that it involves alterations in executive control systems, where attention may be either suppressed or overactivated, leading to a selective disconnection of mental processes (Cojan et al., 2013).

Neuroscientific research has explored the mechanisms of hypnotic induction through a three-stage model (Gruzelier, 1998):

Attention engagement – Activation of a thalamocortical network and left frontolimbic control system, facilitating sensory fixation and concentration.

Inhibitory processing – Suppression of executive functions via frontolimbic mechanisms, allowing relaxation and reduced conscious control.

Imagery activation – Increased involvement of right temporoposterior regions, supporting passive mental imagery and dream-like states.

The way cognitive processing changes during hypnosis depends on individual hypnotizability (Callara et al., 2023).

Recent neurophysiological studies have identified key neural markers of hypnosis. Farahzadi et al. (2023) found that gamma power at the sensor level and beta phase-envelope correlation (PEC) between brain networks are top predictors of hypnosis depth. Using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), they showed that decreased gamma power in the midline frontal region and increased beta PEC between interhemispheric Dorsal Attention Networks (DAN) contribute to hypnotic states. Another study by Negaraj et al. (2020) used deep learning on EEG data to classify hypnosis depth, training a model on sleep EEG data (5,723 clinical EEGs) and testing it on hypnotic EEG data (30 participants) during dexmedetomidine-induced hypnosis. Their CNN-LSTM model achieved 81% accuracy (CI: 79.2–88.3%) and an AUC of 0.89 (CI: 0.82–0.94) in predicting deep hypnotic states.

Neufeld et al. (2016) demonstrated that hypnosis can modulate attentional processing in a bottom-up manner. Their findings support the Social Relevance Hypothesis, showing that neutral hypnotic trance enhances attentional suppression in highly suggestible individuals when observing intentional actions. This suggests that hypnosis can alter social action processing by shifting attention toward relevant stimuli. Jensen et.al. (2015) suggest that the rise in theta oscillations and alterations in gamma activity associated with hypnosis may contribute to certain hypnotic effects.

While extensive research has explored the neural mechanisms of hypnosis, the relationship between the hypnotist and the hypnotized person remains unclear. Understanding how their neural representations compare could provide deeper insights into hypnotic influence, shared cognitive states, and the mechanisms of suggestibility.

In this study, we analyze EEG data from both the hypnotist and the hypnotized individual. To capture meaningful neural features, we apply an autoencoder model and extract the bottleneck layer representation. Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), we examine whether these representations reveal neural similarities or differences between the two groups. The key research question is:

Do the neural representations of the hypnotist and the hypnotized person share significant similarities, and if so, at what level of representation are these similarities most evident?

Hypnosis can modulate autonomic responses, preventing expected physiological reactions to neutral stimuli while amplifying responses to unpleasant imagery (Sebastiani et al., 2003a). Hypnosis also exerts a top-down modulatory effect on preconscious attention and pain perception (De Pascalis et al., 2015), involving both cortical and subcortical structures such as the anterior cingulate cortex, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus. In clinical settings, hypnosis has been successfully combined with local anesthesia and conscious sedation to enhance perioperative and postoperative comfort (Vanhaudenhuyse et al., 2013). Also, hypnosis can be considered as a way of seizure provocation (Khan Y. et. al., 2009).

By investigating the neural relationship between the hypnotist and the hypnotized individual, this study may provide insights that can improve hypnotic instruction techniques, optimizing their effectiveness in both clinical and experimental applications.

2. Related Research

Hypnosis is considered a state of focused attention facilitated by an external expert skilled in suggestion techniques, incorporating strong imaginative elements and involving a dissociation of executive control (Penazzi & De Pisapia, 2022). Research has shown that during hypnosis, brain activity consistently shifts toward higher theta2 and lower alpha1 frequency bands (Deivanayagi et al., 2015).

A study by Rousseaux et al. (2022) demonstrated that Virtual Reality Hypnosis (VRH) induces significant neurophysiological changes, including a decrease in N100 and P200 event-related potential (ERP) amplitudes, a reduction in EEG power between 1 and 5 Hz (from 100 to 560 ms), and an increase in EEG power between 5 and 11 Hz (from 340 to 800 ms). These effects were observed across frontal, central, and posterior brain regions. Additionally, VRH was associated with increased heart rate variability and a reduction in breathing frequency. Further analysis revealed correlations between self-reported pain levels and ERP components, suggesting that VRH influences both cerebral pain processing and physiological responses, ultimately leading to reduced pain perception. These findings provide initial evidence of the analgesic mechanisms of VRH and highlight its potential as an effective method for managing experimental pain.

Studies on neural oscillations have revealed distinct patterns of brain activity during hypnosis. Increases in theta power have been observed in the left parietal and occipital electrodes, while beta power rises in the frontal and left temporal electrodes. Additionally, slow-gamma power increases in the frontal and left parietal regions. Functional connectivity analysis using pairwise-phase consistency measures indicates a decrease in connectivity within frontal electrodes during hypnosis. Graph-based metrics, such as node strength and clustering coefficient, were lower in frontal electrodes in the slow-gamma band during hypnosis compared to the resting state (Kumar et al., 2024b). These findings align with results from other studies.

Hypnotic responsiveness has been consistently linked to increased theta-band power, with some associations also observed in gamma-band activity. However, changes in gamma activity during hypnosis appear to be bidirectional, showing both increases and decreases depending on specific conditions. EEG research on functional connectivity suggests that EEG oscillation frequency alone is not the primary determinant of hypnotic responsiveness or susceptibility. Rather, findings indicate localized disruptions in the left frontal cortex and altered long-range functional connectivity across multiple frequency bands, varying with the type of suggestion and response requirements. These connectivity patterns support the dissociated control models of hypnosis, which propose that disruptions in the integration of the executive control network underlie hypnotic states and responsiveness (De Pascalis, 2024a).

Additionally, Lee et al. (2005) propose that hypnosis results from a reorganization of neural activity across the entire brain network, rather than being confined to activity in a specific brain region.

EEG oscillations of theta (θ) activity have been positively linked to hypnosis responsiveness. Highly hypnotizable individuals exhibit higher amplitude theta waves in the left hemisphere. During hypnosis, activity is reduced in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Wolf et al., 2022).

Jesen et al. (2024) explored the slow wave hypothesis, which suggests that brain activity in slower frequency bands, such as theta and alpha, can enhance susceptibility to hypnosis. Significant interactions were observed in EEG beta coherence. The high susceptibility group (n = 7) showed decreased coherence, while the low susceptibility group (n = 10) displayed increased coherence between medial frontal and lateral left prefrontal sites (White et al., 2008).

Jamieson and Burgess (2014) found an increase in theta iCOH from pre-hypnosis to hypnosis in highly susceptible individuals, but not in those with low susceptibility. Significant connections were notably concentrated in a central-parietal hub. In contrast, a decrease in beta1 iCOH was observed in the highly susceptible group, focusing on fronto-central and occipital hubs, compared to the low susceptible group.

Hypnosis and susceptibility to hypnosis are important factors in cognitive task performance, as they affect physiological parameters. Highly susceptible individuals demonstrate greater cognitive flexibility, enabling them to easily adjust their psychophysiological state and respond to various suggestions. Results from a study by Sebastini et al. (2003b) showed that hypnotic traits influence physiological parameters, such as skin resistance, heart rate, respiratory rate, and changes in relative EEG power across theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands.

A significant increase in broadband activity during stepwise trance induction suggests a deep hypnotic state, providing evidence that physiological state changes correlate with different levels of awareness, consciousness, or cognition during hypnosis (Hinterberger et al., 2011).

De Pascalis et al. (2024b) support the notion that disruptions in the integration between different components of the executive control network during hypnosis may correspond to altered subjective appraisals of agency during the hypnotic response, in line with the dissociation and cold control theories of hypnosis. A promising avenue for further research involves investigating how neurochemical activity and aperiodic EEG components in the frontal lobes at waking-rest are linked to individual differences in hypnotizability.

Kumar et al. (2024a) conducted a multicentric study using measures of synergistic and redundant information to examine high-order interactions between five EEG electrodes during three non-ordinary states of consciousness (NSCs): Rajyoga meditation (RM), hypnosis, and auto-induced cognitive trance (AICT). Their findings revealed that during RM, synergy increased across the whole brain in the delta and theta bands, while redundancy decreased in frontal, right central, and posterior electrodes in delta, and in frontal, central, and posterior electrodes in beta1 and beta2 bands. In hypnosis, synergy decreased in mid-frontal, temporal, and mid-centro-parietal electrodes in the delta band, and also in beta2 at the left frontal and right parietal electrodes. In AICT, synergy decreased in delta and theta bands in left-frontal, right-frontocentral, and posterior electrodes, with a decrease in the alpha band across the whole brain.

Bauer et al. (2021) used a within-subject design to compare iEEG data during mind-wandering, mindfulness meditation, and hypnosis. Their data-driven connectivity analysis revealed widespread connectivity patterns that were common across all three conditions, primarily in the low-frequency bands (delta, theta, and alpha), characterized by positively correlated activity. Unique connectivity patterns for each condition predominated in the gamma band, with one-third of the correlations in these patterns being negative.

Despite the extensive research on various aspects of hypnosis, there is a noticeable gap in the literature regarding the relationship between the hypnotic state and the hypnotist’s role. Most studies focus on the physiological and neural responses of the subjects under hypnosis, but the dynamic between the hypnotist and the subject, particularly how the hypnotist influences the subject’s brain activity, remains underexplored. This study aims to address this gap by investigating the interaction between the hypnotic state and the hypnotist, exploring how the hypnotist’s expertise in suggestion techniques may modulate the subject’s brainwave activity and overall responsiveness to hypnosis.

3. Methods

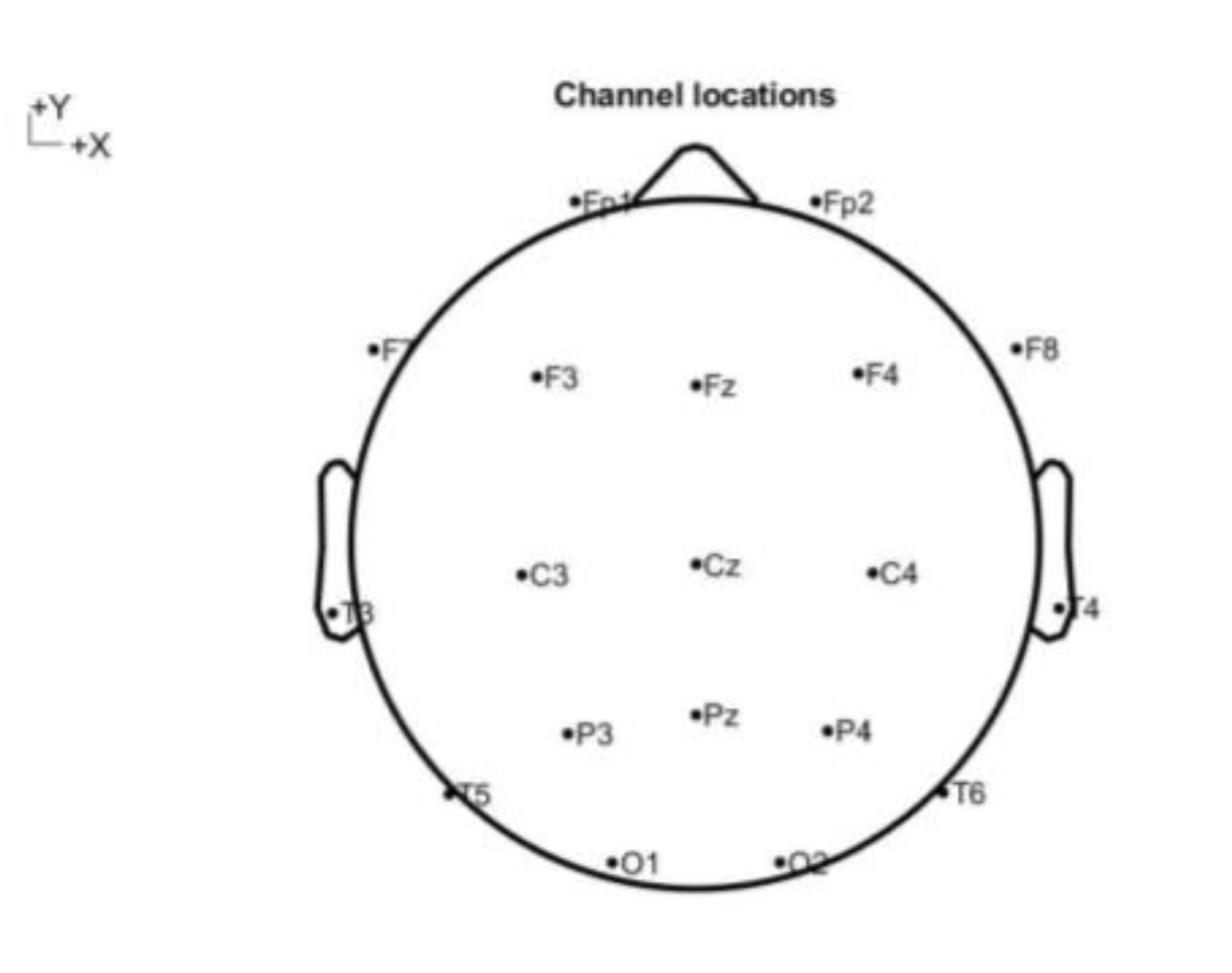

EEG channels were monitored for 20 min (for hypnotized and hypnotist) keeping the eyes closed, sitting and avoiding movements, and with the instruction to see colors, and then imagination (moving through space and time) and speaking about it. The twenty minutes of EEG recordings were captured at 250 Hz from 19 channels, with their locations shown in

Figure 1.

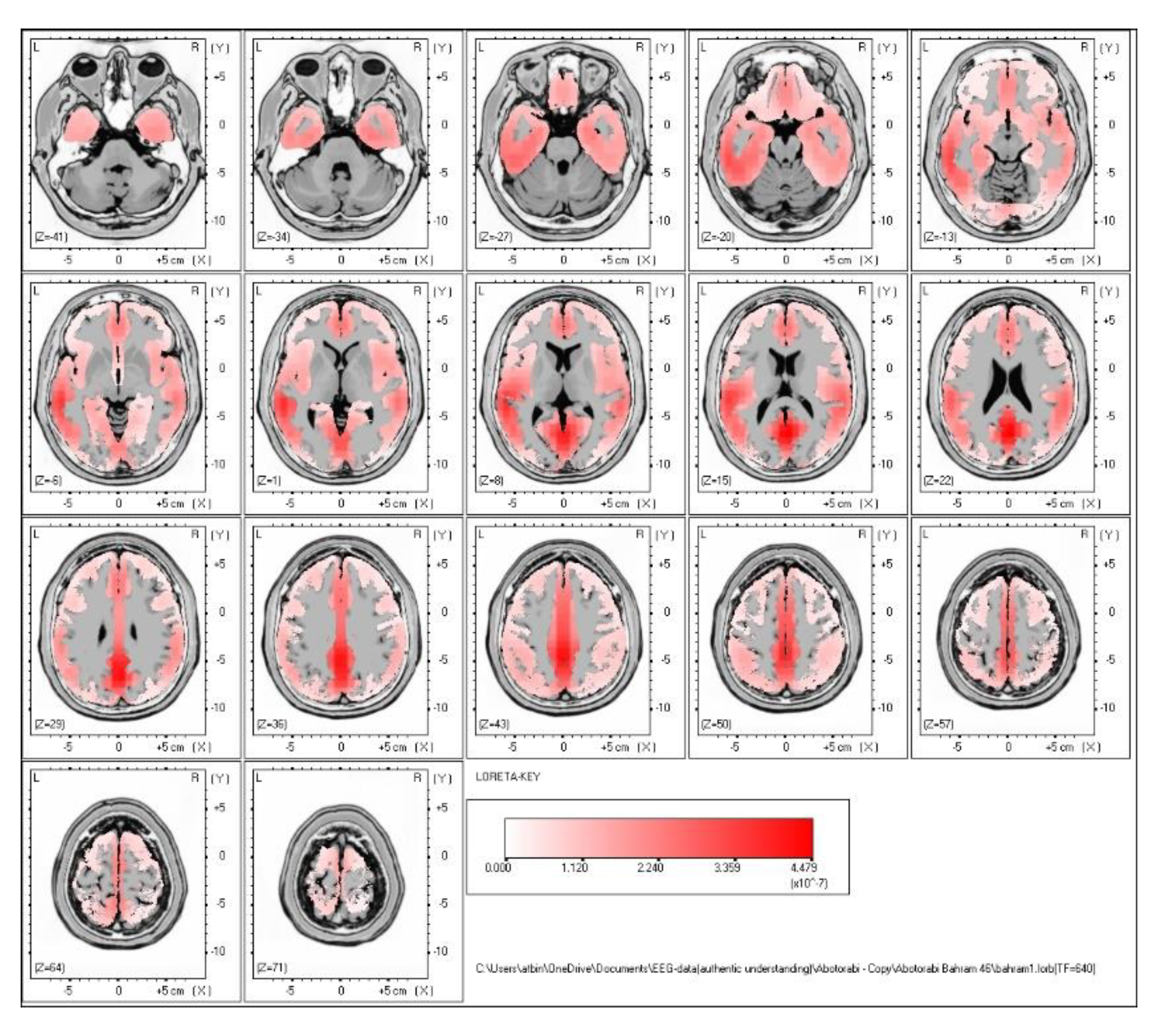

The EEG data were preprocessed using EEGLAB, where steps such as noise removal, data cleaning, and artifact rejection (ASR and ICA) were applied to ensure that the signals accurately reflected meaningful brain activity. The brain activity of hypnotist is shown in

Figure 2.

For EEG data analysis, deep learning model (U-Net) was implemented using TensorFlow and Keras in Python. The models were developed and trained in ‘Google Colab’. After preprocessing, the cleaned EEG data were transformed into images with a resolution of 128×128×3. They were randomized and classified into train and test groups (0.8 train, 0.2 test) after normalization.

Datasets: Two EEG datasets (hypnotizer & hypnotized).

Train-Test Split: 80% for training, 20% for validation in both datasets.

Normalization: Applied Min-Max normalization to scale data between [0,1].

Image Transformation: Converted EEG data into images of shape (128, 128, 3) for processing in the autoencoder.

Model Training

Autoencoder Structure: 18-layer deep network with a bottleneck layer at layer 9.

Training Strategy:

Trained the autoencoder on both datasets together.

The model learns to compress EEG data into the bottleneck layer and reconstruct it.

Validation: Used 20% of data for evaluation to check reconstruction quality.

3.1. Data Processing

EEG signals from both hypnotizer and hypnotized individuals which were preprocessed, fed into an U-Net autoencoder.

The autoencoder compressed the data into a low-dimensional bottleneck layer, capturing the most essential features.

Features extracted from the bottleneck were analyzed using PCA to explore their distribution and compare the two individuals.

3.2. Autoencoder Architecture

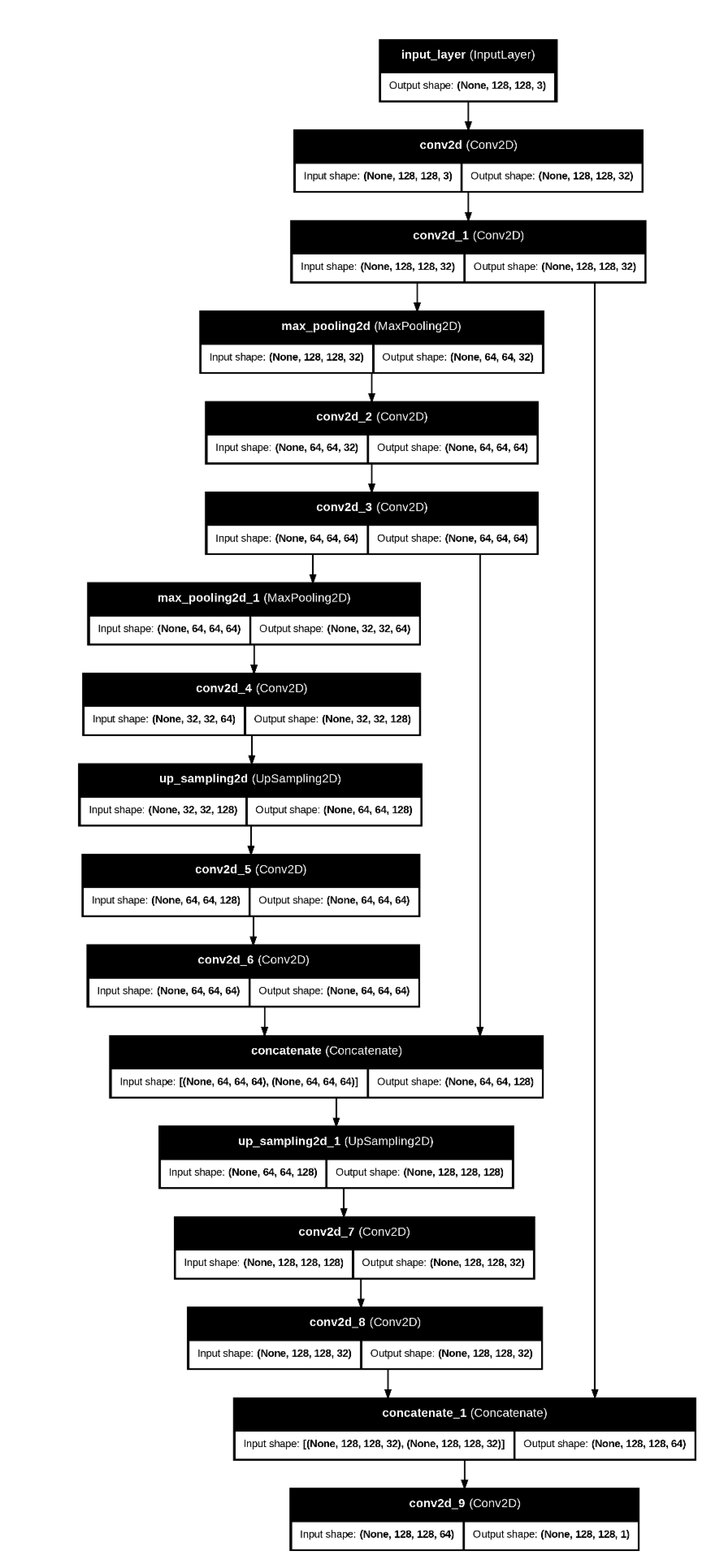

As it is shown (

Figure 3), the U-Net 17 layers model consisted of:

Encoder: A series of dense layers reducing the EEG features into a bottleneck representation.

Bottleneck Layer: The most compressed form of the data, ideally retaining only the most critical features.

Decoder: A reconstruction process to ensure the bottleneck features still capture meaningful information.

4. Results

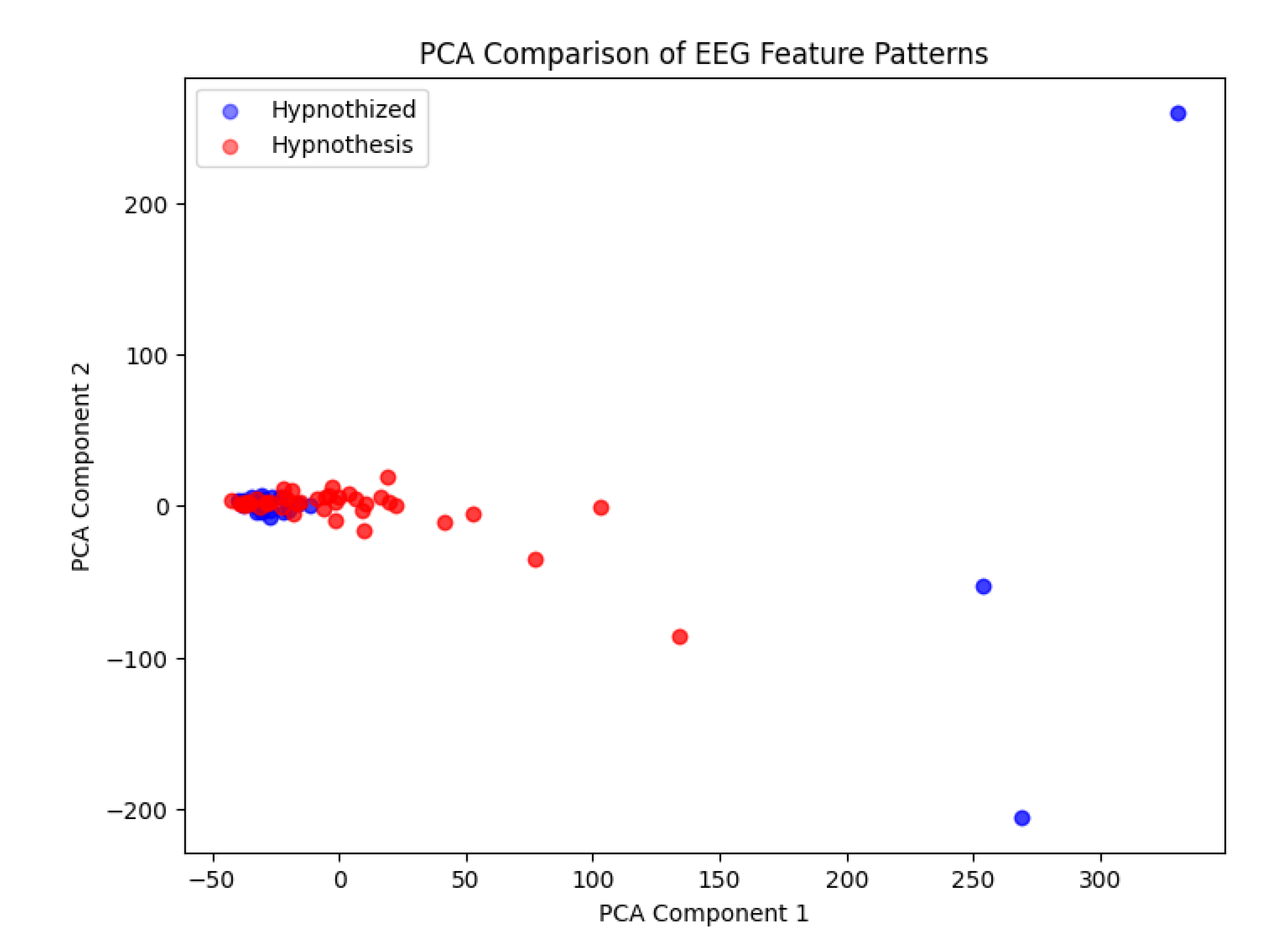

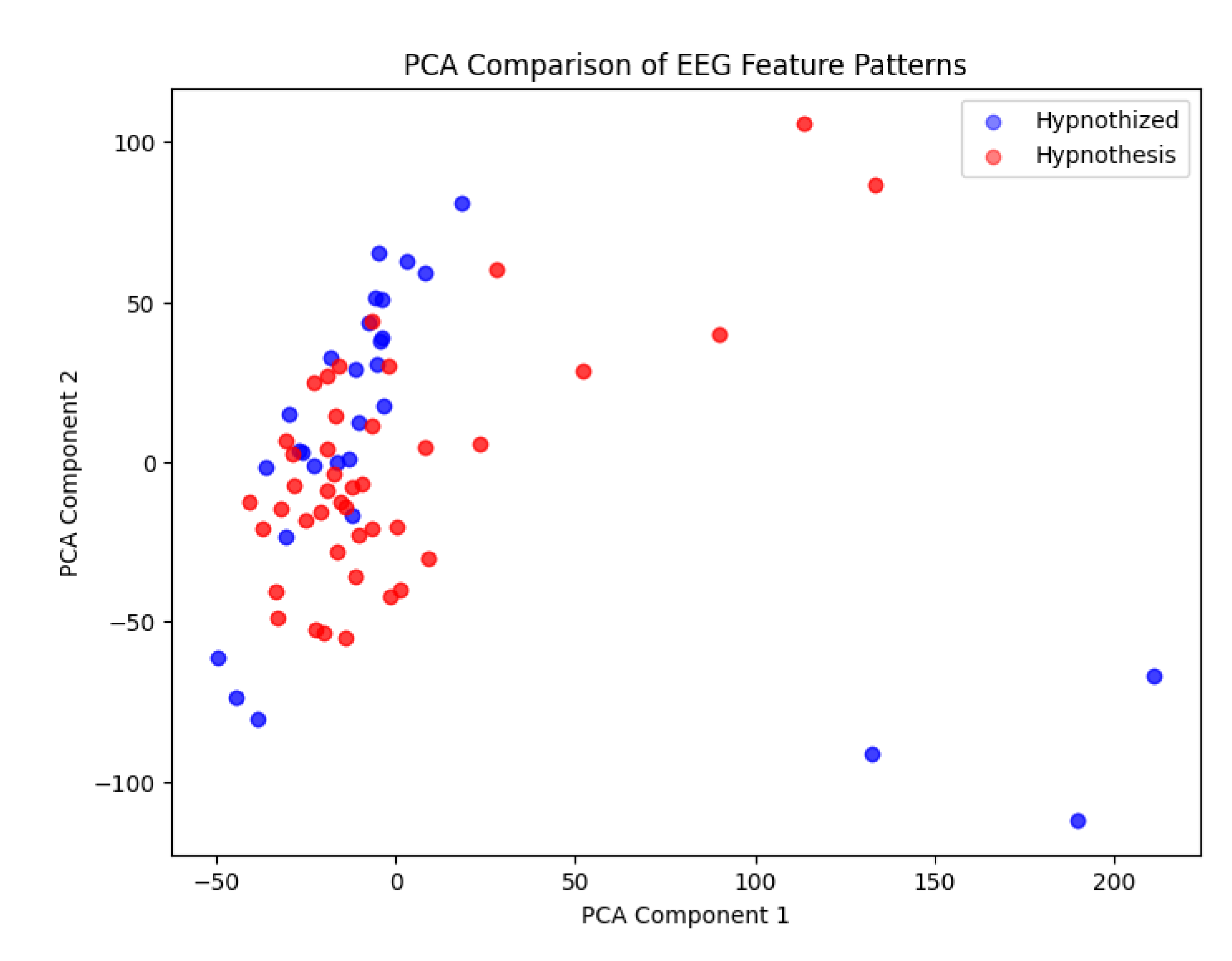

4.1. PCA Analysis of Bottleneck Features

When visualized using PCA, data points from the hypnotist and hypnotized individuals were highly overlapping, suggesting that their brain activity patterns were nearly indistinguishable at this level of compression.

Only a few data points (3-4 points) showed slight divergence, indicating minor differences in their EEG representations.

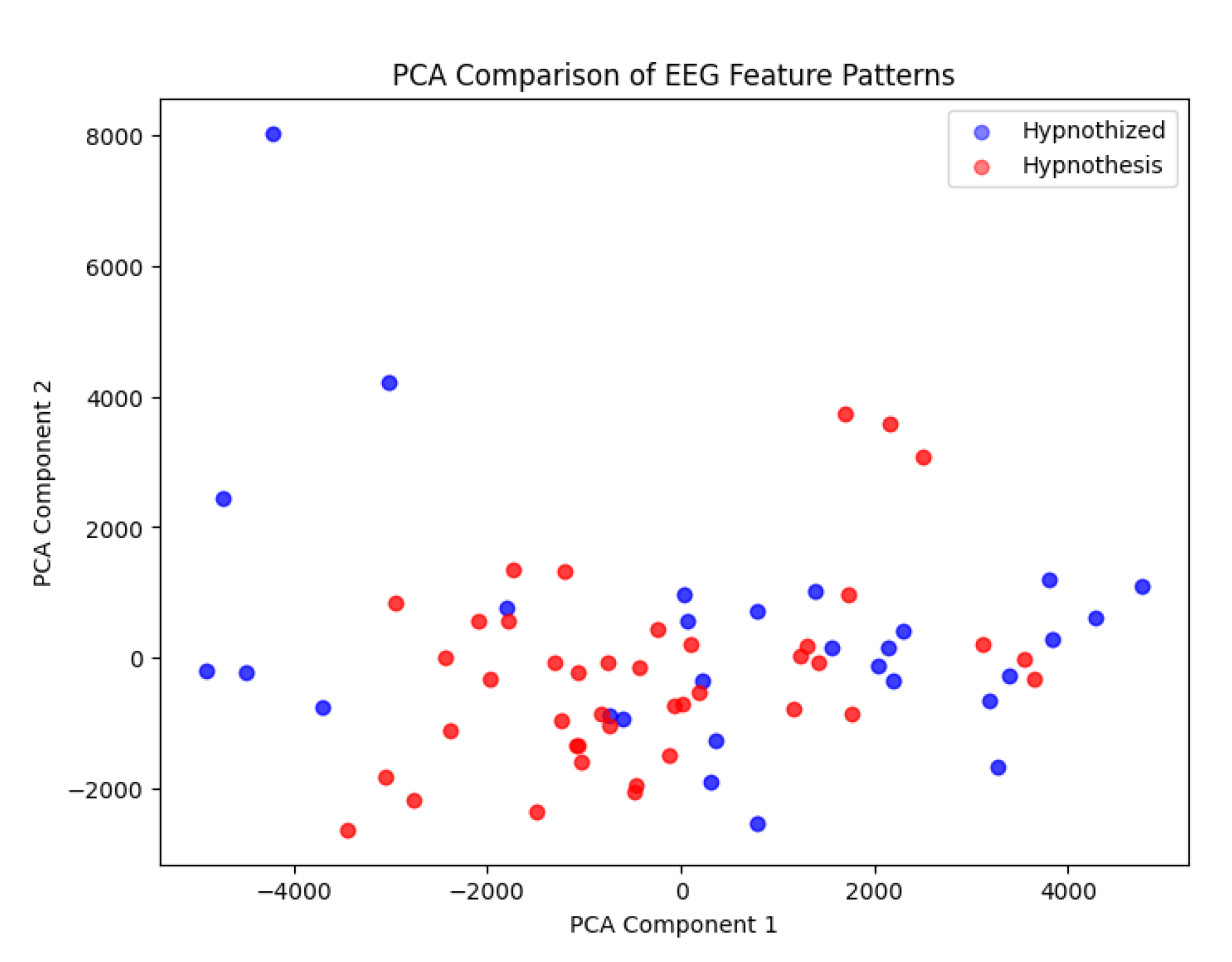

4.2. Contrast at Different Autoencoder Layers

While the

bottleneck layer showed the

highest degree of similarity, earlier and later layers in the autoencoder showed

slightly more contrast between the two individuals (

Figure 5).

5. Interpretation & Discussion

5.1. What Does the Bottleneck Similarity Mean?

The strong overlap in the PCA visualization of the bottleneck layer suggests that the hypnotist and hypnotized individual may share a common neural pattern during hypnosis.

This could imply that both participants enter a synchronized neural state, possibly due to cognitive and emotional mirroring, attentional focus, or shared intent.

5.2. Potential Explanations

Neural Synchronization Theory: Hypnosis might involve a form of neural coupling between the hypnotizer and the hypnotized individual, leading to overlapping brain activity patterns.

Shared Cognitive Processing: Both individuals may engage similar brain networks related to attention, expectation, and altered consciousness.

While numerous studies have characterized the neural signatures of hypnotized subjects—most notably the increase in delta and theta band activity—there remains a significant gap in our understanding of the hypnotist’s neural dynamics. It is intriguing to hypothesize that the hypnotist might not only exhibit similar patterns but also intentionally modulate these oscillations during the hypnotic process.

Future investigations—ideally using simultaneous neuroimaging or EEG recordings of both hypnotist and subject—are necessary to determine whether this intentional modulation indeed occurs, and if so, to what extent it differentiates the hypnotist’s brain activity from that of the hypnotized individual.

5.3. Significance of the Few Differing Points

This study opens a new avenue for investigating the differential brain function patterns between hypnotists and hypnotized subjects. The emerging evidence suggests that, while there are overlapping neural mechanisms during hypnosis, specific differences may exist that are crucial for the hypnotist’s role in the process. The 3-4 diverging points in the PCA visualization might correspond to:

Slight timing differences in brain activity synchronization.

Artifacts or noise in the EEG recordings.⸻

Intentional Modulation vs. Passive Response:

Our findings indicate that the hypnotist may actively modulate neural activity—particularly by enhancing delta and theta oscillations—to facilitate the induction of a hypnotic state in the subject. In contrast, the hypnotized individual appears to exhibit these slower oscillations as a passive response to relaxation and altered attention states.

Beta activity, commonly associated with alertness and active cognitive processing, is differentially regulated. The hypnotist maintains a controlled level of beta activity to support focused attention and effective command during the session. Conversely, the hypnotized individual typically shows a reduction in beta activity, aligning with a shift toward a more relaxed, internally focused state.

Overall, these differences suggest that the hypnotist’s brain might be uniquely equipped for intentional modulation and control, contrasting with the passive, state-dependent neural changes observed in the hypnotized individual. Future research employing simultaneous neuroimaging or EEG recordings of both parties is needed to further elucidate these mechanisms and validate the proposed models of inter-brain connectivity during hypnosis.

6. Conclusion

Hypnosis is a state of focused attention and heightened suggestibility, where individuals become deeply immersed in their internal experiences, such as thoughts, emotions, and mental imagery. Research on neural oscillations has identified distinct brain activity patterns during hypnosis, including increased theta power in the left parietal and occipital regions, elevated beta power in the frontal and left temporal areas, and enhanced slow-gamma power in the frontal and left parietal regions.

In this study, EEG data analysis was conducted using a deep learning model (U-Net) implemented with TensorFlow and Keras in Python. Features extracted from the model’s bottleneck layer were analyzed using PCA to examine their distribution and compare data from two individuals. The results indicate that hypnotists and hypnotized individuals exhibit highly similar EEG representations at the bottleneck layer of an autoencoder. This similarity is further confirmed through PCA visualization, which reveals only minor deviations.

These findings suggest that hypnosis may involve shared neural mechanisms, potentially supporting theories of neural synchronization or cognitive mirroring. While previous studies have extensively examined the neural signatures of hypnotized individuals—particularly the increase in delta and theta activity—there is limited research on the hypnotist’s brain dynamics. It is especially intriguing to consider that hypnotists may not only exhibit similar neural patterns but could also actively regulate these oscillations during hypnosis.

Future research should incorporate simultaneous neuroimaging or EEG recordings of both the hypnotist and the hypnotized individual to determine whether such intentional modulation occurs and, if so, how it differentiates the hypnotist’s neural activity. Additionally, exploring functional connectivity measures (e.g., coherence, phase-locking) could provide further insights into how these neural patterns interact.

References

- Bauer, Prisca R, Cécile Sabourdy, Benoît Chatard, Sylvain Rheims, JeanPhilippe Lachaux1, Juan R. Vidal, Ant (2021). Neural dynamics of mindfulness meditation and hypnosis explored with intracranial EEG: a feasibility study. Elsevier. https://www.elsevier.com/open-access/userlicense/1.0.

- Callara, A.L.; Zeliˇc, Ž.; Fontanelli, L.; Greco, A.; Santarcangelo, E.L.; Sebastiani, L. Is Hypnotic Induction Necessary to Experience Hypnosis and Responsible for Changes in Brain Activity? Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pascalis V, Varriale V, Cacace I (2015) Pain Modulation in Waking and Hypnosis in Women: Event-Related Potentials and Sources of Cortical Activity. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0128474. [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, V. (2024b). Brain Functional Correlates of Resting Hypnosis and Hypnotizability: A Review. Brain Sci. 14, 115. [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, Vilfredo (2024a). EEG oscillatory activity concomitant with hypnosis and hypnotizability. https://www.researchgate. 3776. [CrossRef]

- Deivanayagi, S., M. Manivannan, Peter Fernandez (2015). Spectral Analysis Of EEG Signals During Hypnosis. International Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics. ISSN 0973-4864.

- Gruzelier, John (1998). A WORKING MODEL OF THE NEUROPHYSIOLOGY OF HYPNOSIS: A REVIEW OF EVIDENCE. Contemporary Hypnosis. Vol. 15, No. I, pp.3-21.

- Hinterberger, Thilo, Julian Schöner und Ulrike Halsband (2011). Analysis of Electrophysiological State Patterns and Changes During Hypnosis Induction. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis Volume 59, Issue 2. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, A. , Graham, Adrian P. Burgess (2014). Hypnotic induction is followed by state-like changes in the organization of EEG functional connectivity in the theta and beta frequency bands in high-hypnotically susceptible individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Barrett, T.D. (2024). The Role of ElectroencephalogramAssessed Bandwidth Power in Response to Hypnotic Analgesia. Brain Sci. 14, 557. https:// doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14060557.

- Jensen, Mark P., Tomonori Adachi, Shahin Hakimian (2015). Brain Oscillations, Hypnosis, and Hypnotizability. Pages 230-253. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y. Ahsan, Lyle Baade, Elizabeth Ablah, Victor McNerney, Mazhar H. Golewale, Kore Liow (2009). Can hypnosis differentiate epileptic from nonepileptic events in the video/EEG monitoring unit? Data from a pilot study. Epilepsy & Behavior 15, 314–317. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G. , Pradeep, Rajanikant Panda, Kanishka Sharma, A. Adarsh, Jitka Annen, Charlotte Martial, Marie-Elisabeth Faymonville, Steven Laureys, Corine Sombrun, Ramakrishnan Angarai Ganesan, Audrey Vanhaudenhuys, Olivia Gosseries (2024a). Changes in high-order interaction measures of synergy and redundancy during non-ordinary states of consciousness induced by meditation, hypnosis, and auto-induced cognitive trance. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Govindaiah, P.; Adarsh, A.; Panda, R.; Gosseries, O.; Malaise, N.; Salamun, I.; Tshibanda, L.; Laureys, S.; Bonhomme, V.; Faymonville, M. (2024b). Exploring Electrophysiological Responses to Hypnosis in Patients with Fibromyalgia. Brain Sci. 14, 1047. https:// doi.org/10. 3390. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jun-Seok, Sae-Byul Kim, Byung-Hwan Yang, David Spiegel, Ju-Yeon Choi, Jun-Ho Choi, Seok-Hyeon Kim, Jang-Han Lee, Sun-Il Kim (2005). Fractal Analysis of EEG During Waking and Hypnosis: Laterality and Regional Differences. Psychiatr Invest. 2 (1): 53-60.

- Neufeld, Eleonore, Elliot C. Brown, Sie-In Lee-Grimm, Albert Newen, Martin Brüne (2016). Intentional action processing results from automatic bottom-up attention: An EEG-investigation into the Social Relevance Hypothesis using hypnosis. Consciousness and Cognition 42, 101–112.

- Penazzi G and De Pisapia N (2022) Direct comparisons between hypnosis and meditation: A mini-review. Front. Psychol. 13:958185. [CrossRef]

- Rousseaux, Floriane, Rajanikant Panda, Clémence Toussaint, Aminata Bicego, Masachika Niimi, Marie-Elisabeth Faymonville, Anne-Sophie Nyssen, Steven Laureys, Olivia Gosseries, Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse (2022). Virtual reality hypnosis in the management of pain: Self-reported and neurophysiological measures in healthy subjects. [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, L., A. Simoni, A. Gemignani, B. Ghelarducci, E.L. Santarcangelo (2003a). Human hypnosis: autonomic and electroencephalographic correlates of a guided multimodal cognitive-emotional imagery. Neuroscience Letters 338, 41–44.

- Sebastiani, L., A. Simoni, A. Gemignani, B. Ghelarducci, E.L. Santarcangelo (2003b). Autonomic and EEG correlates of emotional imagery in subjects with different hypnotic susceptibility. / Brain Research Bulletin 60 (2003) 151–160. [CrossRef]

- Vanhaudenhuyse, A., S. Laureys, M.-E. Faymonville (2014). Neurophysiology of hypnosis. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology. Volume 44, Issue 4, 14, Pages 343-353. 20 October. [CrossRef]

- White, David, Joseph Ciorciari, Colin Carbis und David Liley (2008). EEG Correlates of Virtual Reality Hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Volume 57, Issue 1. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Ann (2019). What is hypnosis and how might it work. R: Palliative Care. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.G.; Faerber, K.A.; Rummel, C.; Halsband, U.; Campus, G. (2022). Functional Changes in Brain Activity Using Hypnosis: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 12, 108. [CrossRef]

- Yann Cojan, Aurélie Archimi, Nicole Cheseaux, Lakshmi Waber, Patrik Vuilleumier (2013). Time-course of motor inhibition during hypnotic paralysis: EEG topographical and source analysis. Volume 49, Issue 2, 13, Pages 423-436. 20 February. [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh Farahzadi, Cameron Alldredge, Zoltán Kekecs (2023). Neural Correlates of Hypnosis: Insights from EEG-Based Machine Learning Models. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).