1. Introduction

Pain is an important global health issue; according to the Global Burden of Disease Study, this condition affects approximately 20% of the worldwide population, with low back pain, neck pain, and migraines being the most common causes [

1]. Chronic pain not only leads to physical suffering but also contributes to psychological issues like depression and anxiety [

2]. Uncontrolled pain has also been linked to increased healthcare utilization, including hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and greater financial burden [

3]. Nevertheless, pain is not merely a physical sensation; it also involves emotional and psychological components, making it a complex and multidimensional experience [

4]. In particular, chronic pain is an experience that persists beyond the healing period, often without a clear cause. Such prolonged issues can alter how the brain processes information, leading to magnified sensitivity. Hence, it requires comprehensive detection and treatment approaches that address both the physical and psychological aspects [

5].

Pain detection and assessment are crucial for effective management, allowing healthcare professionals to understand intensity, nature, and impact [

6]. Yet, pain is subjective; thus, self-reporting is often the most reliable method of assessment by means of tools such as the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [

7]. Nevertheless, in cases where self-reporting is challenging—such as with young children, older adults with cognitive impairments, or non-verbal patients—observational scales and physiological approaches are not suitable [

6]. Significant progress has been made in pain assessment, particularly in patients unable to communicate. However, current clinical methods still predominantly depend on subjective evaluations [

7]. These tools are susceptible to external factors such as mood and lack of physiological bases, limiting their accuracy [

8].

In contrast, electrical, pressure, and thermal stimulators have been created, as well as PainMatcher, to get a more accurate picture of pain. Nevertheless, these methods are invasive as they require the application of painful stimuli to record responses [

9]. Since pain perception is deeply influenced by brain activity, as well as psychological factors such as expectations and emotions that shape conscious pain experience, neuroimaging techniques have been extensively studied for brain activity-based pain detection [

10]. These techniques are broadly classified into invasive and non-invasive methods. Invasive methods, like Electrocorticography (ECoG) and intracranial Electroencephalography (iEEG), offer high spatial and temporal resolution but involve surgical risks. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Magnetoencephalography (MEG), Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS), and Electroencephalography (EEG) are some of the non-invasive techniques that are more commonly used because they are safe, cost-effective, and simple to use [

11]. EEG, in particular, has gained popularity for studying brain connectivity and identifying dysfunctional areas [

12]. Its ability to capture specific brain activity patterns makes it a valuable tool for understanding pain and enhancing applications in neurorehabilitation, including motor imagery and brain-computer interface (BCI) systems [

13,

14].

Still, EEG-based pain detection is significantly hindered by inherent challenges, such as high noise levels and volume conduction issues [

15]. The inherent noise in scalp-recorded signals significantly obscures the underlying neural activity. Also, EEG signals are less accurate when they are affected by things outside the brain, such as electromagnetic interference from lights, AC power lines, and electronics, and noise from things going on inside the body, such as digestion, skin resistance changes, heart activity, eye movements, muscle movements, and breathing [

16]. Furthermore, functional activities detected by EEG are affected by volume conduction before being recorded in the scalp, leading to correlations between multiple EEG channels that affect competitive performance [

17,

18].

Moreover, both between- and within-subject variability pose significant challenges to developing a universal EEG-based pain detection algorithm. Genetic, cognitive, and neurodevelopmental differences contribute to variability in neural responses to pain, making it difficult to generalize across individuals. Research has shown that inter- and intra-individual neural variability significantly affects the accuracy of decoding pain-related EEG signals, complicating the identification of universal neural pain markers [

19]. Additionally, genetic variations, such as those related to serotonin regulation, have been linked to differences in pain perception and EEG-based biomarkers, further underscoring the complexity of subject-independent pain assessment [

20]. Furthermore, EEG-based functional connectivity analyses have revealed substantial differences in pain-related neural activity in newborns, emphasizing the need for adaptive, personalized models for pain detection [

21].

In the specific context of EEG-based pain assessment using Machine Learning (ML), traditional approaches such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Random Forests, and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) have been widely applied [

22]. These methods are popular due to their ability to handle high-dimensional data and provide interpretability, which is crucial to understanding the relationship between EEG signals and pain. Additionally, in [

23] the authors underscored the potential of EEG and ML models such as SVM, LDA, k-NN, and Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) in pain biomarker research. Moreover, [

24] explored the potential of EEG to detect pain in adolescents, including those with chronic musculoskeletal pain and those without it, by using SVMs and logistic regression models to classify resting and pain conditions based on EEG signal features. Recently, authors in [

8] introduce a ML strategy to distinguish between pain states and non-pain by extracting functional connectivity features and employing a combination of an SVM with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel and a decision tree. Similarly, [

25] implemented a decision tree based on average brain maps to classify pain levels. In contrast, [

26] developed a hierarchical SVM classifier to categorize pain intensities. Each node within this classifier utilized a custom subset of features, selected using the sequential forward selection method, with the SVM parameters fine-tuned through Bayesian optimization. However, ML-based strategies rely on handcrafted features and struggles with capturing complex brain activity patterns, often lacking the generalization required for robust EEG-based analysis [

27].

Deep Learning (DL)-based EEG classification algorithms have demonstrated exceptional potential in overcoming the challenges associated with EEG signal analysis. Among these, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have emerged as the most effective for feature extraction, as they can efficiently capture both spatial and temporal patterns [

28]. Notable CNN architectures widely used for EEG classification include EEGNet, ShallowConvNet, and DeepConvNet, which have shown superior performance in decoding. Beyond CNNs, various DL models have been investigated for EEG analysis. Autoencoders, for example, transform EEG data into a lower-dimensional feature space while reducing noise, enabling the generation of more refined signal representations [

29]. Meanwhile, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) leverage the sequential nature of EEG signals, effectively capturing temporal dependencies essential for understanding signal dynamics [

30]. Recently, Transformer-based models have gained prominence for their ability to capture long-range dependencies, effectively extracting both global and local features of EEG signals through attention mechanisms [

31]. Despite these advancements, applying these DL approaches in the medical field, particularly for EEG-based pain detection, remains a significant challenge. First, their black box nature hinders interpretability, making it difficult to derive meaningful insights into the neurological mechanisms specific to each individual [

32]. Second, these models frequently fail to account for the intricate interconnections between neurological, physiological, and behavioral factors [

33]. Recognizing and incorporating these influences is essential to achieve more personalized outcomes.

To face the above challenges, some approaches have been proposed to enhance the well-established EEGNet architecture. For instance, the Kernel Regularized EEGNet (KREEGNet) employs a Central Kernel Alignment (CKA) framework as a regularization strategy to optimize model performance [

34]. Besides, the Kernel Cross-Spectral Functional Connectivity Network (KCS-FCNet) applies Gaussian kernels aiming to determine functional connectivities and feeding these into a fully connected layer, that maps EEG data into a higher-dimensional feature space to enhance its representation and favors classification tasks [

35]. Nevertheless, subject-dependent approaches remain widely used, often lacking the necessary generalization for effective cross-subject pain assessment.

On the other hand, in terms of interpretability, various attribution methods have emerged. Class Activation Maps (CAMs) are widely used for image-based tasks, as they identify which parts of the input most influence the model’s decisions. Initially introduced in [

36], CAMs employ weighted activations in a given layer to compute the impact of each feature on the outcome. Grad-CAM extends this by reweighting based on gradients from the model, though it presumes uniform importance across activations [

37]. Yet, crucial spatio-frequency features remain unclear, limiting their potential for enhancing explainability in EEG-based pain detection [

38].

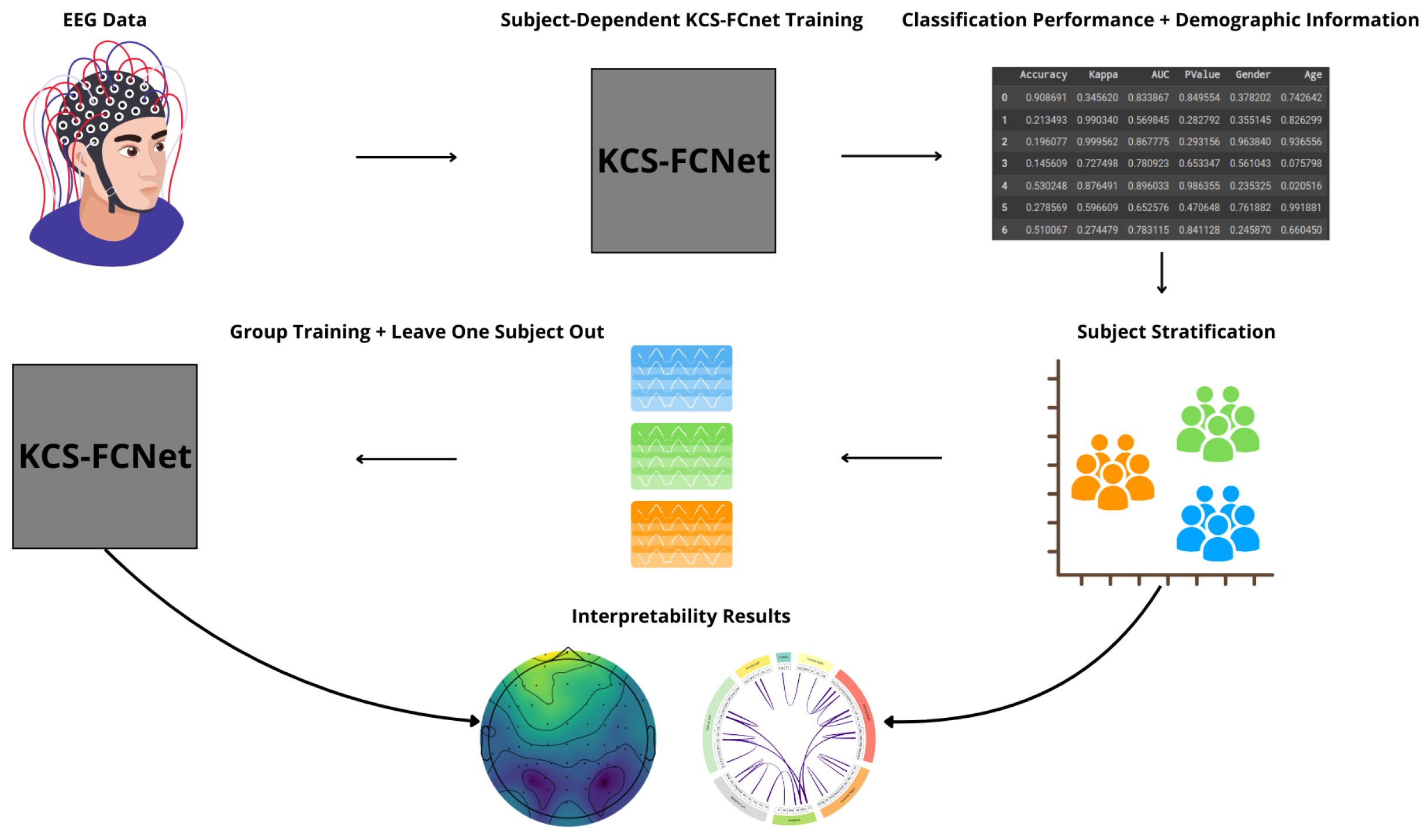

We present an EEG-based pain detection framework for non-verbal patients leveraging the KCS-FCNet model [

35]. We structure our approach into three key components:

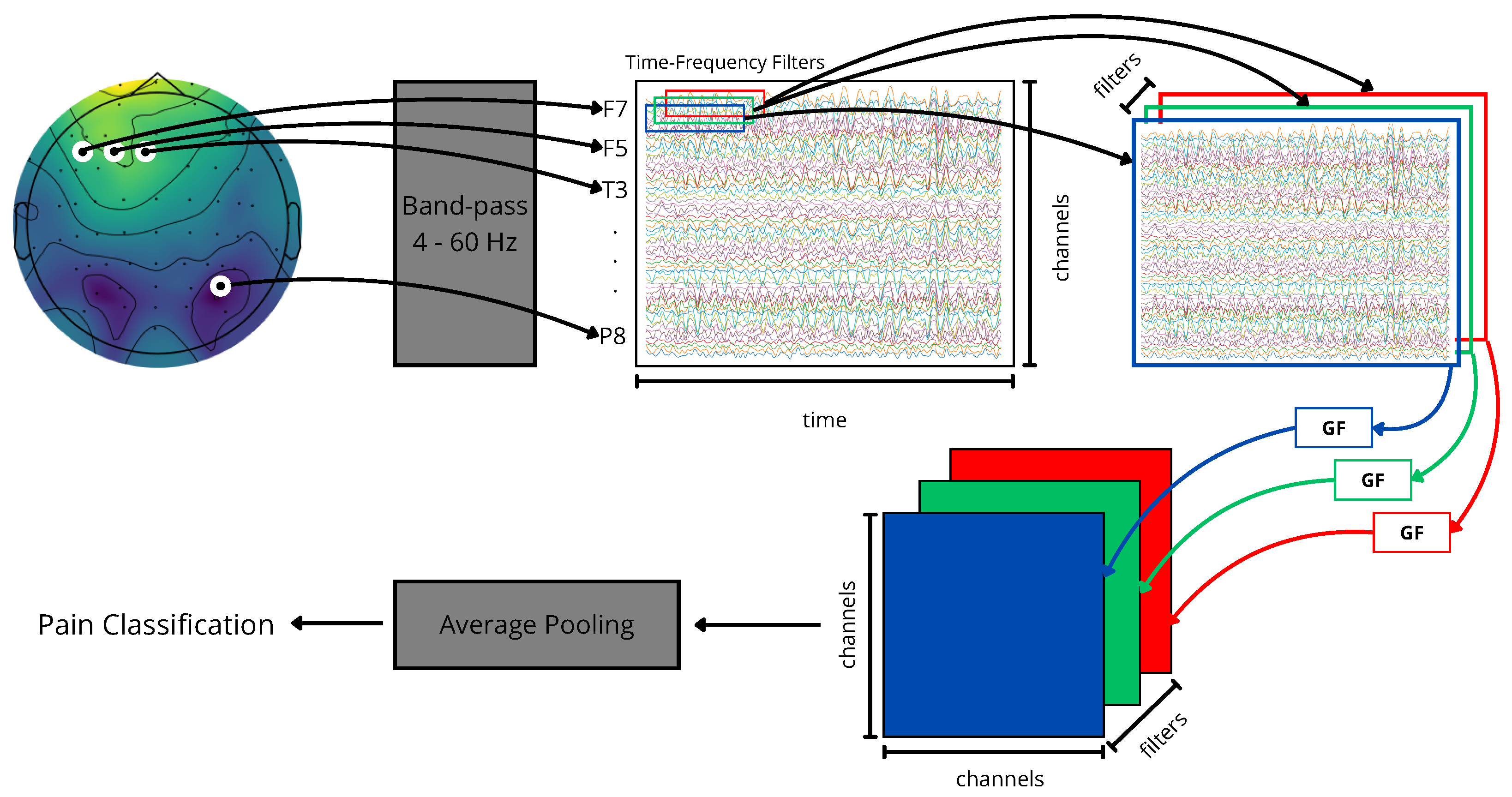

KCS-FCNet-based Pain Detection: We employ 1D convolutional layers to extract rich spatio-frequency features from EEG channels. Additionally, cross-spectral distribution estimation is utilized to capture pain-related patterns, generating functional connectivity feature maps that reveal meaningful pairwise channel relationships.

Explainability through Frequency CAM (FCAM): To enhance model interpretability, we introduce Frequency CAM (FCAM), a novel technique that provides deeper insights into the model’s decision-making by analyzing both input EEG channel importance and frequency band contributions to pain detection.

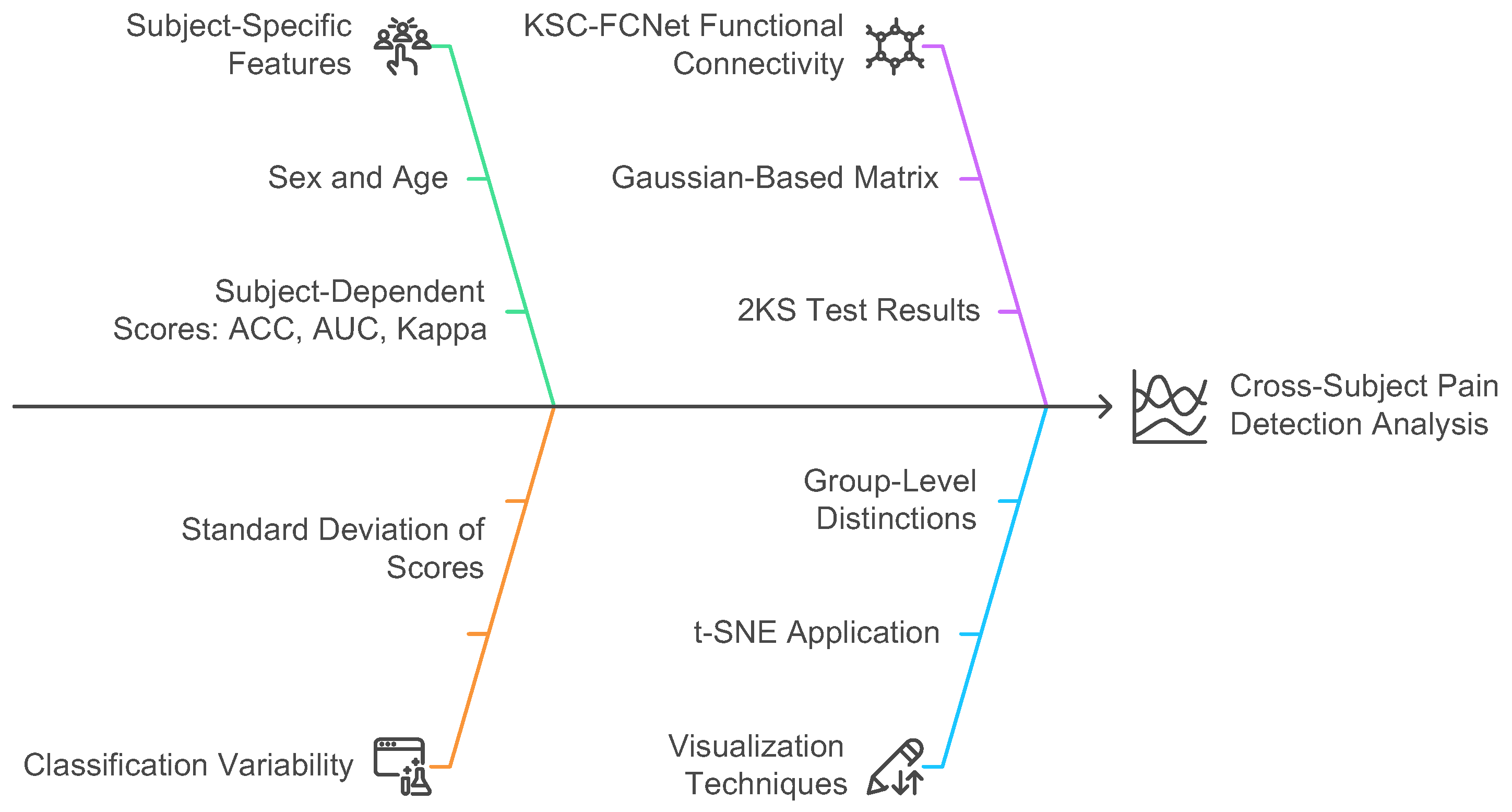

Cross-Subject Analysis: We address subject variability by performing cross-subject analysis and grouping, clustering individuals based on similar pain detection performance, functional connectivity patterns, sex, and age, thus improving generalizability across diverse populations.

For testing, we employ the Brain Mediators of Pain dataset [

39], to classify between no pain and high pain states. To assess the inter-subject generalization capabilities, we compare the performance of classical machine learning models, EEGNet, and our enhanced KCS-FCNet framework in EEG-based pain detection tasks [

39]. Furthermore, we utilize both subject-dependent training and a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation strategy to evaluate model generalizability across different individuals. Our findings demonstrate that the proposed KCS-FCNet model offers a robust, non-invasive pain detection solution with enhanced spatio-frequency interpretability, making it particularly valuable for assisting in pain assessment for non-verbal patients.

The remainder is as follows:

Section 2 describes the materials and methods.

Section 3 and

Section 4 present the experiments and discuss the results. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusions and future work.

5. Conclusions

We present a novel EEG-based pain detection framework designed to support pain assessment in non-verbal patients. Central to our approach is the Kernel Cross-Spectral Functional Connectivity Network (KCS-FCNet), which effectively captures discriminative spatio-frequency EEG patterns by modeling pairwise channel dependencies through Gaussian kernel-based connectivity. To improve interpretability, we introduce the Frequency Class Activation Mapping (FCAM) technique—an adaptation of the Grad-CAM++ method—allowing for detailed visualization of relevant EEG channels and frequency bands contributing to the model’s predictions. Furthermore, we perform a comprehensive cross-subject analysis that incorporates subject-dependent performance metrics, KCS-FCNet-derived functional connectivity patterns, as well as demographic attributes such as sex and age, enabling the grouping of individuals with similar pain-related neural responses.

Our results demonstrate that the proposed KCS-FCNet framework offers a robust and interpretable solution for EEG-based pain detection, particularly suited for non-verbal populations. By integrating kernel-based functional connectivity estimation with convolutional neural networks, our model effectively captures spatio-frequency dependencies across EEG channels, achieving superior classification performance compared to traditional machine learning methods and baseline deep learning models such as EEGNet. Also, the incorporation of Frequency Class Activation Maps (FCAMs) further enhances the model’s interpretability, providing insight into the spectral and spatial patterns associated with pain states, differentiation male and female pain detection patterns.

Additionally, the cross-subject analysis underscores the model’s generalization capability, especially when stratifying by sex and leveraging connectivity-based metrics. The improved performance within specific demographic subgroups suggests that personalized models, informed by subject-specific features, can yield more accurate and reliable pain detection. These findings reinforce the importance of considering both biological and connectivity-based heterogeneity in EEG signals when developing clinically applicable tools for objective pain assessment.

Future work will explore the extension of this approach to multimodal data, integrating EEG with other physiological or behavioral signals such as fNIRS, heart rate variability, or facial expressions to enhance pain classification performance in real-world scenarios [

52]. We also plan to validate the framework on clinical datasets involving chronic and spontaneous pain conditions, moving beyond experimental stimuli [

53]. Furthermore, the development of lightweight, real-time implementations of KCS-FCNet will be essential for deployment in bedside or wearable monitoring systems, ultimately supporting continuous and objective pain assessment in clinical environments.

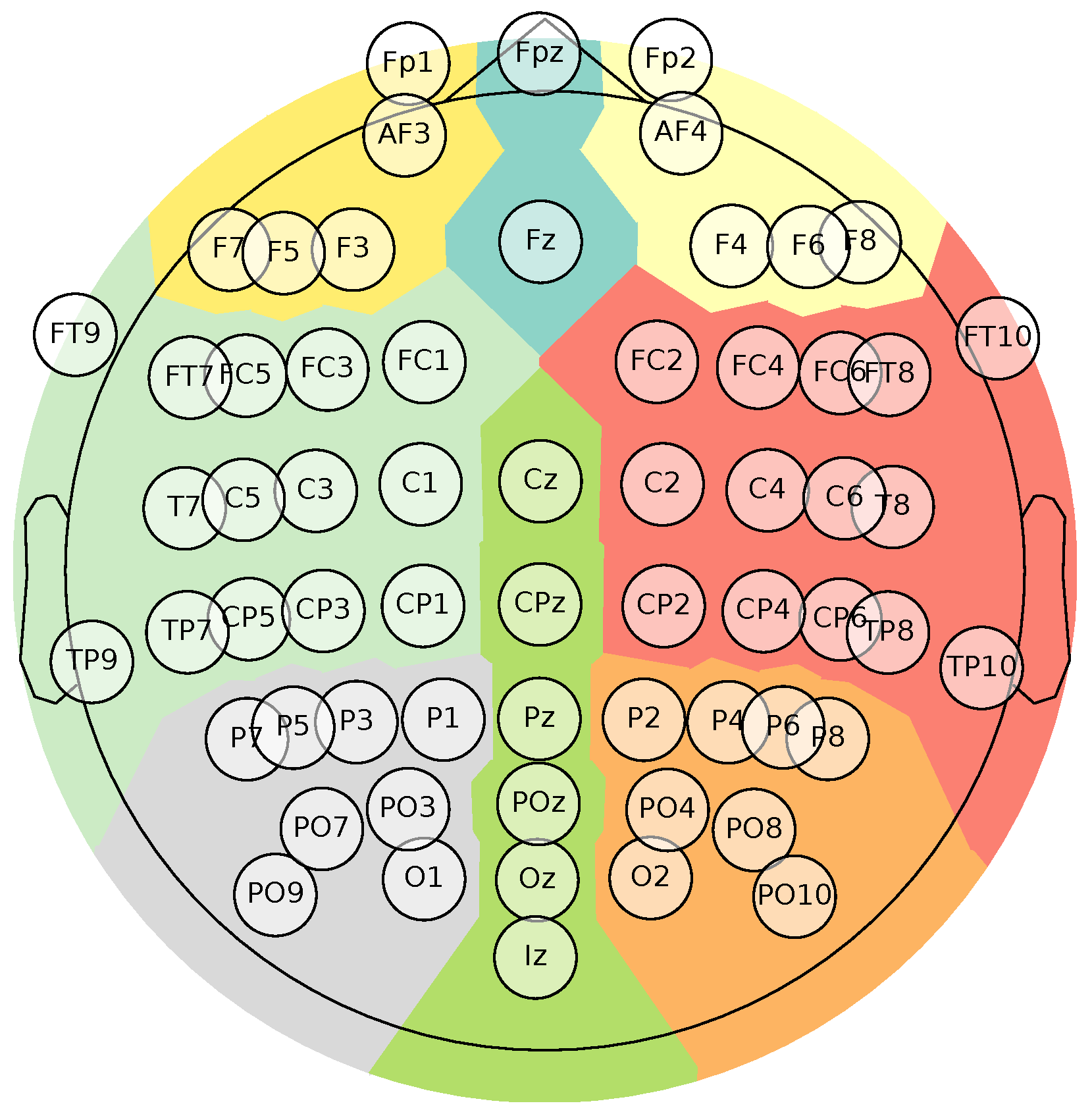

Figure 1.

Brain Mediators of Pain EEG Montage. The topoplot illustrates the sensor positions in a 10–20 placement EEG electrode system, containing 65 channels. Besides, it highlights in color the main parts of the brain ( Frontal left, Frontal, Frontal right, Central right, Posterior right, Posterior, Posterior left, Central left).

Figure 1.

Brain Mediators of Pain EEG Montage. The topoplot illustrates the sensor positions in a 10–20 placement EEG electrode system, containing 65 channels. Besides, it highlights in color the main parts of the brain ( Frontal left, Frontal, Frontal right, Central right, Posterior right, Posterior, Posterior left, Central left).

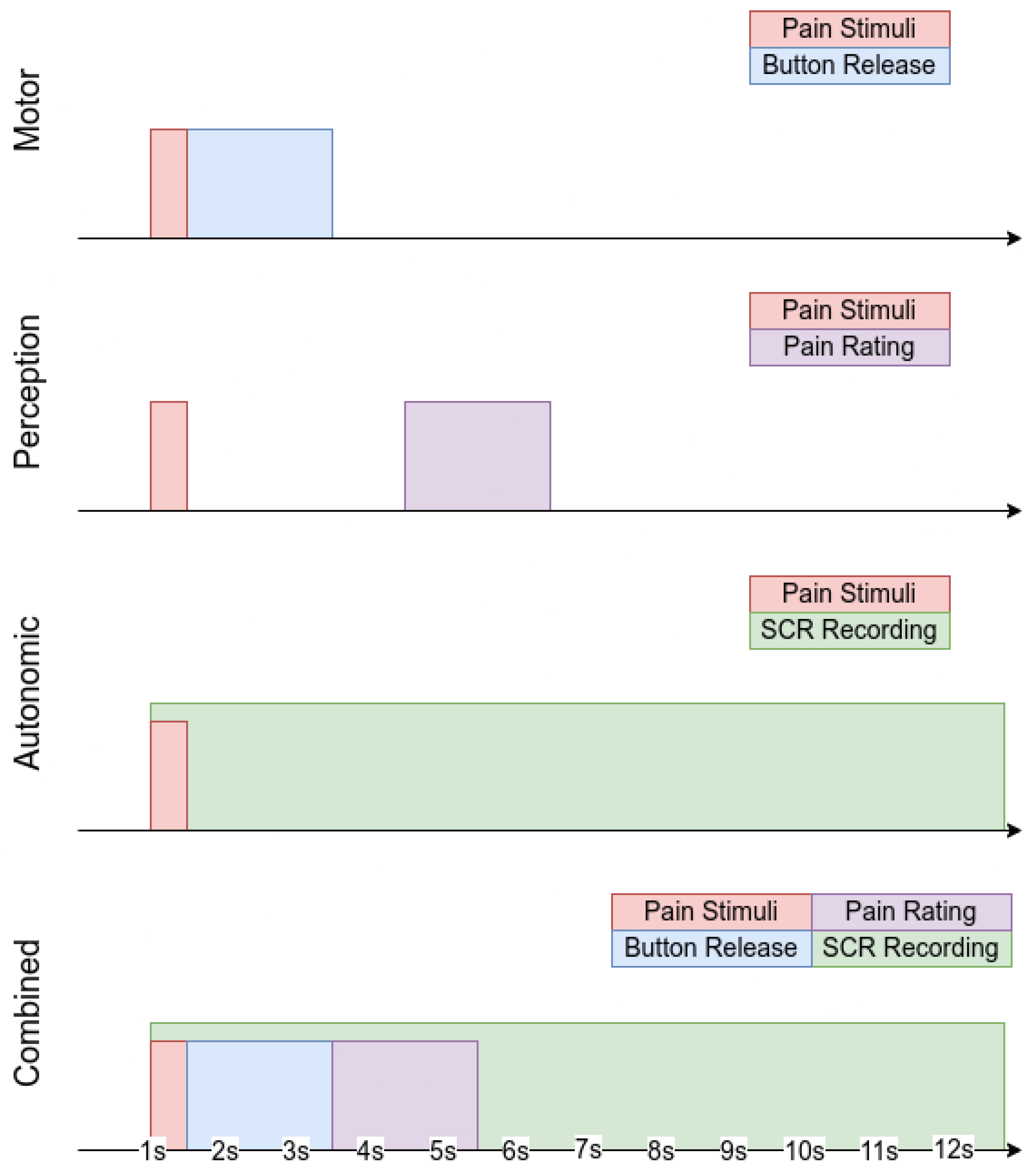

Figure 2.

Brain Mediators of Pain database experimental paradigms sketch.

Figure 2.

Brain Mediators of Pain database experimental paradigms sketch.

Figure 3.

Kernel Cross-Spectral Functional Connectivity Network-(KCS-FCNet) pipeline for EEG-based pain detection. Our proposal aims to support non-verbal patient pain detection through brain activity analysis (no-pain vs. high-pain).

Figure 3.

Kernel Cross-Spectral Functional Connectivity Network-(KCS-FCNet) pipeline for EEG-based pain detection. Our proposal aims to support non-verbal patient pain detection through brain activity analysis (no-pain vs. high-pain).

Figure 4.

Cross-Subject Pain Detection Analysis based on KCS-FCNet detection.

Figure 4.

Cross-Subject Pain Detection Analysis based on KCS-FCNet detection.

Figure 5.

Proposed pipeline for subject-dependent and cross-subject pain detection testing.

Figure 5.

Proposed pipeline for subject-dependent and cross-subject pain detection testing.

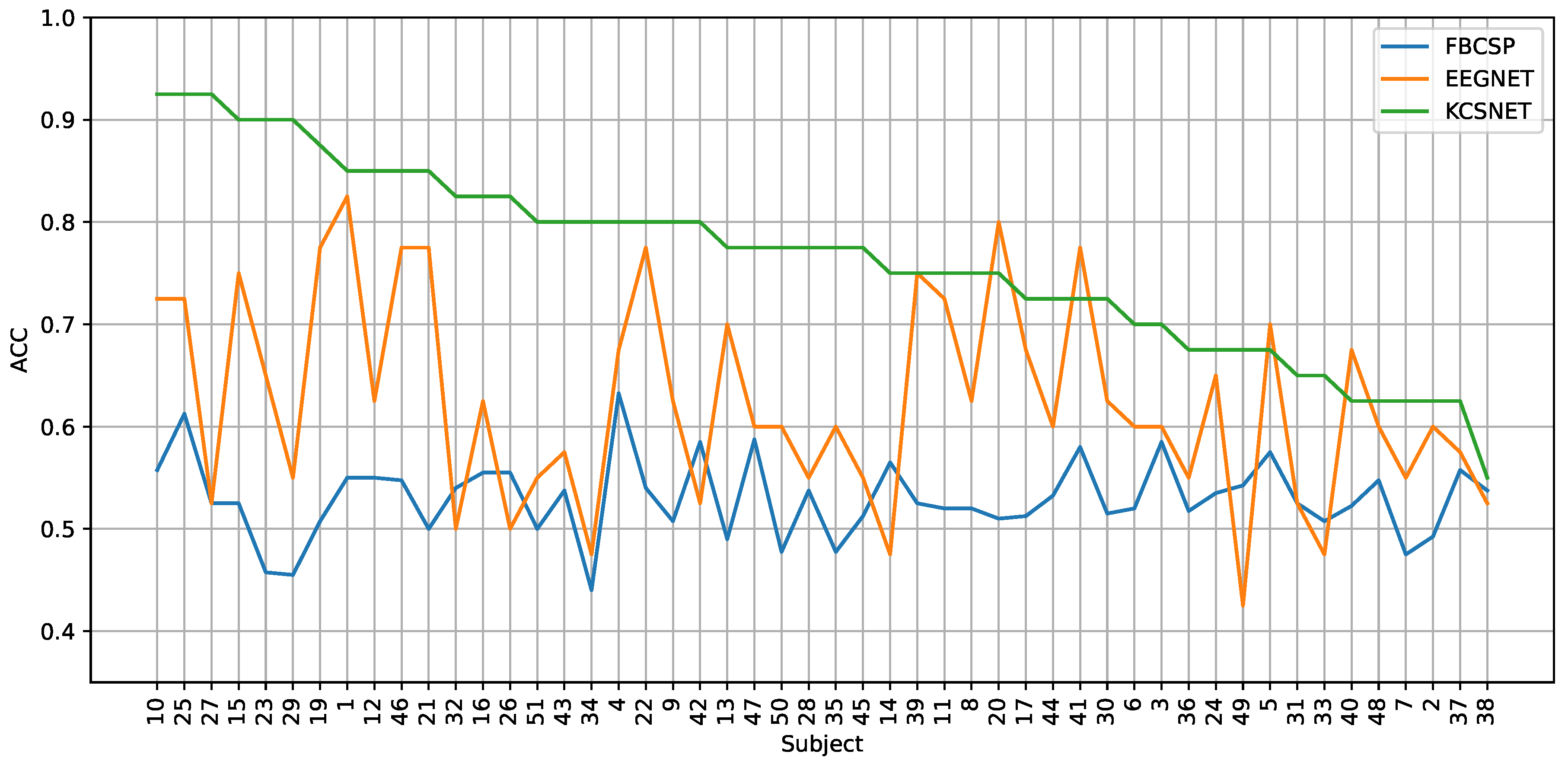

Figure 6.

Subject-dependent pain detection results. An accuracy comparison between FBCSP, EEGNet, and KCS-FCNet (ours) is presented. Subjects are sorted regarding the KCS-FCNet performance.

Figure 6.

Subject-dependent pain detection results. An accuracy comparison between FBCSP, EEGNet, and KCS-FCNet (ours) is presented. Subjects are sorted regarding the KCS-FCNet performance.

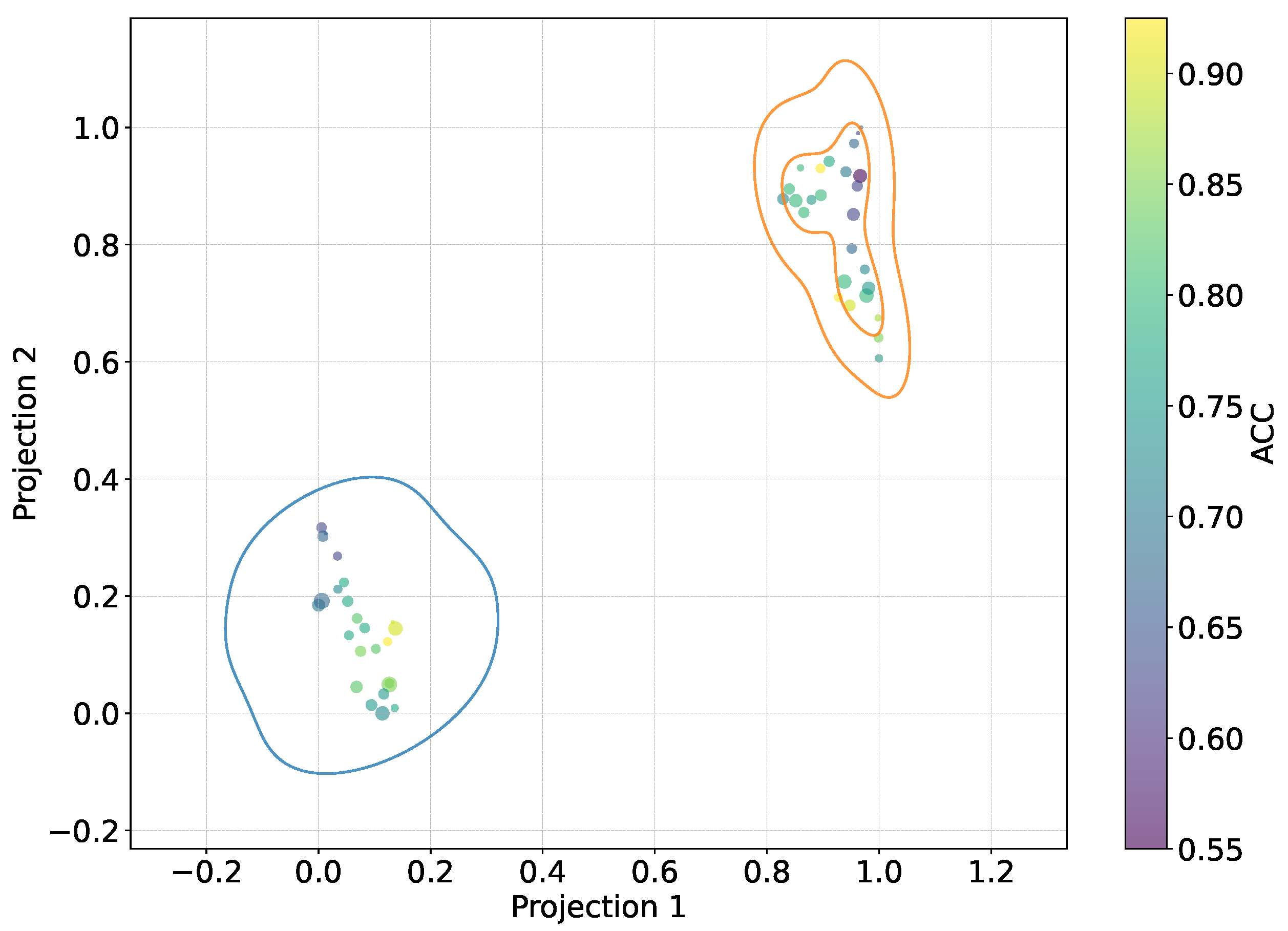

Figure 7.

2D t-SNE projection visualizing cross-subject relationships. Subject-dependent performance (ACC, AUC, and Kappa) for FBSCP, EEGNet, and KCS-FCNet. Also, KCS-FCNet functional connectivity patterns, sex, and age features are used for subject stratification. Points within the blue region represent women, while those within the orange regions represent men. The sizes correspond to the subjects’ ages, and the color point stands for subject-dependent pain detection ACC.

Figure 7.

2D t-SNE projection visualizing cross-subject relationships. Subject-dependent performance (ACC, AUC, and Kappa) for FBSCP, EEGNet, and KCS-FCNet. Also, KCS-FCNet functional connectivity patterns, sex, and age features are used for subject stratification. Points within the blue region represent women, while those within the orange regions represent men. The sizes correspond to the subjects’ ages, and the color point stands for subject-dependent pain detection ACC.

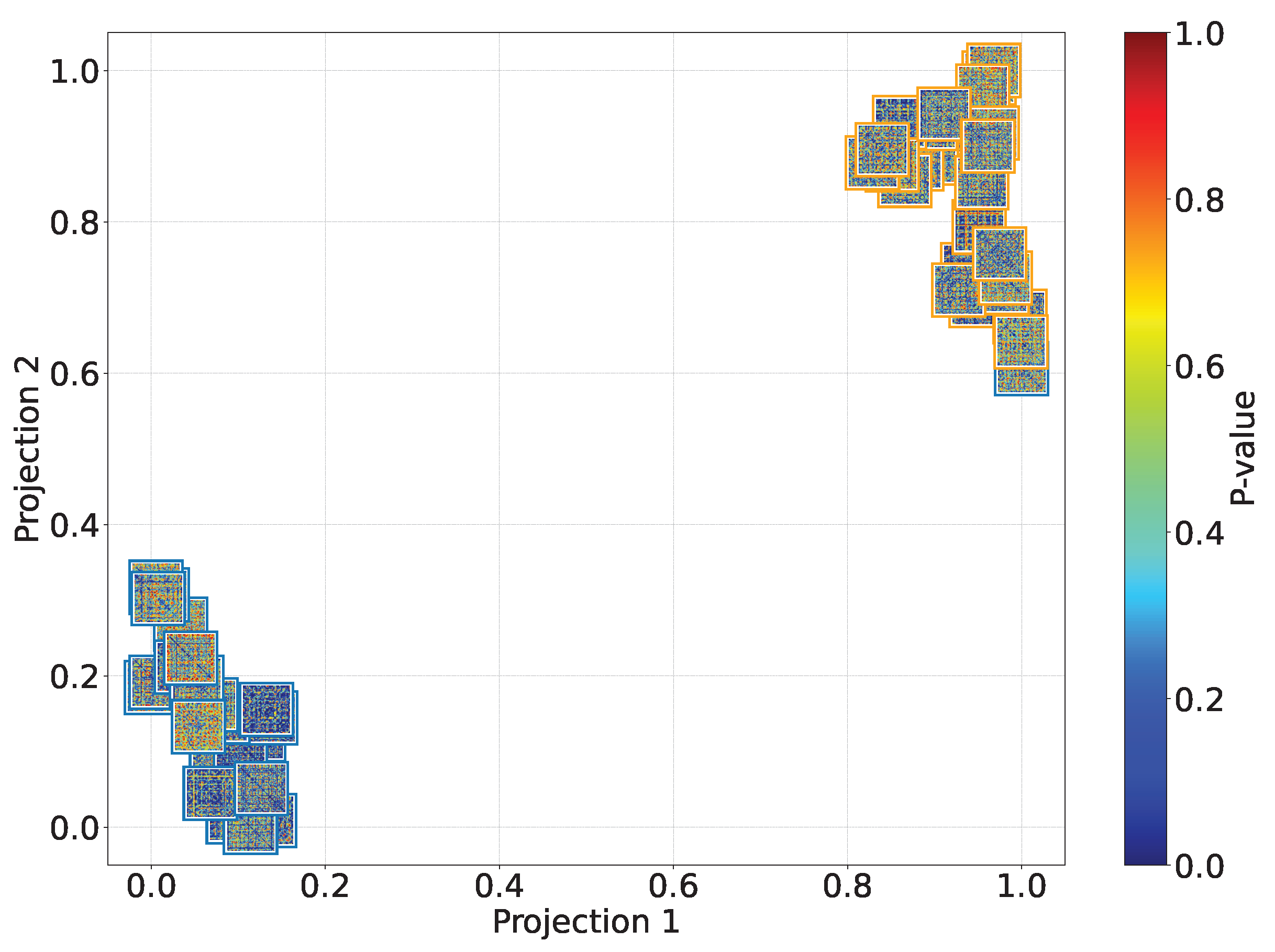

Figure 8.

2D

t-SNE projection visualizing cross-subject relationships regarding the KCS-FCNet estimated connectivity. Pruned functional connectivity matrices based on the 2KS are shown (see

Section 2.4). The color bar depicts the p-value of every connection for each subject matrix, where deep blue means more class separability. Therefore, the bluer the matrix, the better the discriminability. Outer boxes indicate subject gender: orange for male and blue for female.

Figure 8.

2D

t-SNE projection visualizing cross-subject relationships regarding the KCS-FCNet estimated connectivity. Pruned functional connectivity matrices based on the 2KS are shown (see

Section 2.4). The color bar depicts the p-value of every connection for each subject matrix, where deep blue means more class separability. Therefore, the bluer the matrix, the better the discriminability. Outer boxes indicate subject gender: orange for male and blue for female.

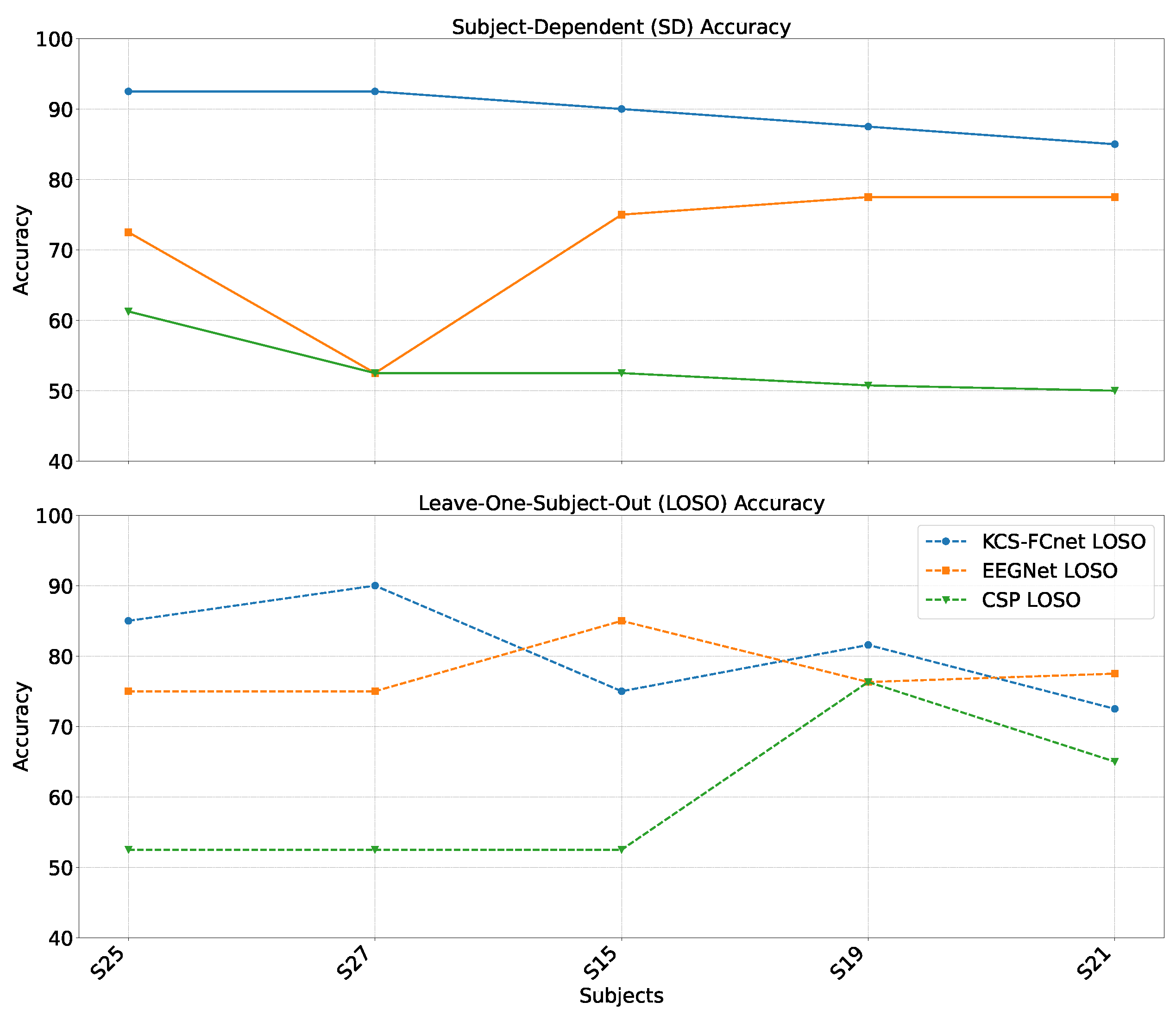

Figure 9.

Males’ group accuracy comparison within the subject-dependent and cross-subject pain detection experiments.

Figure 9.

Males’ group accuracy comparison within the subject-dependent and cross-subject pain detection experiments.

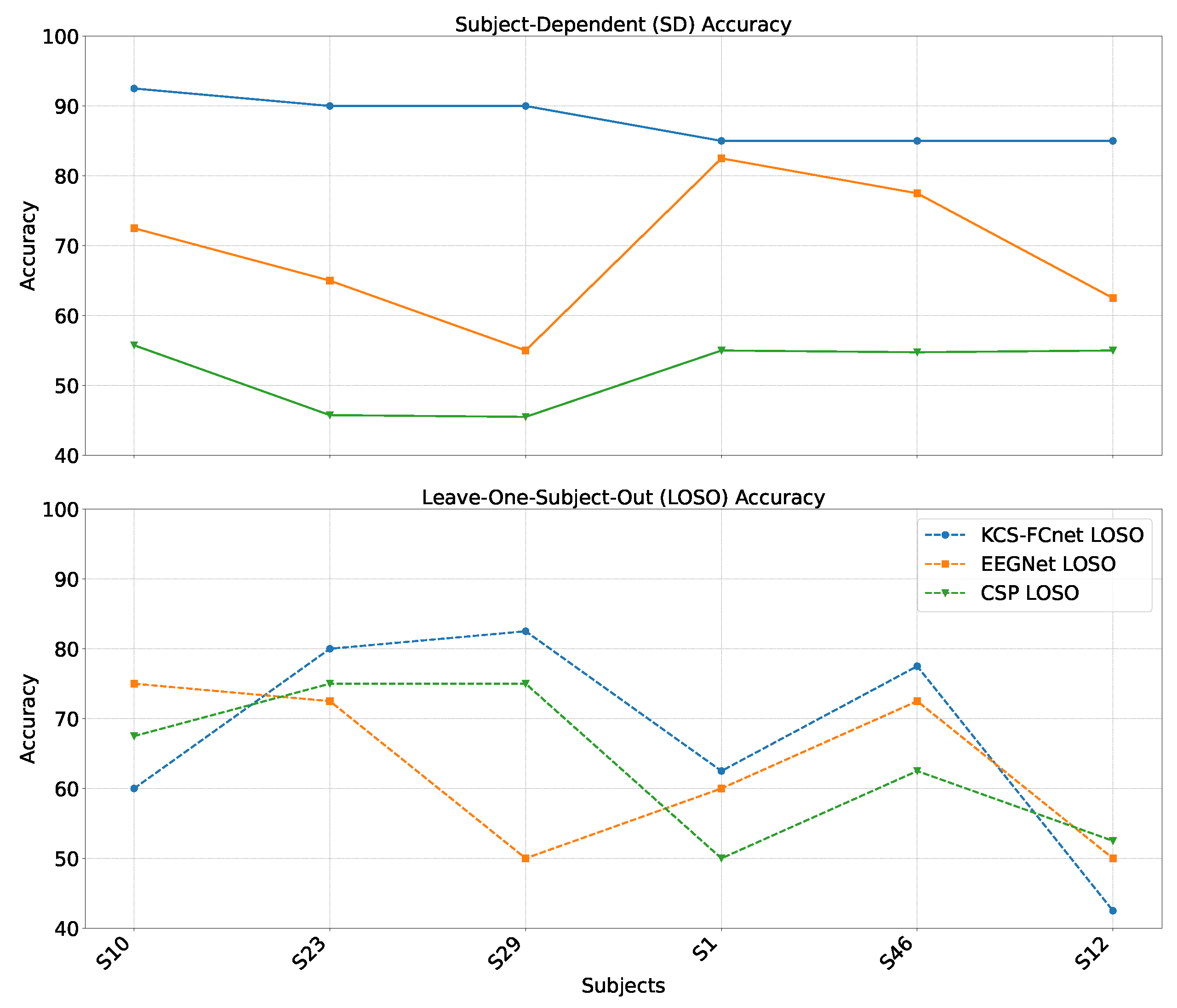

Figure 10.

Females’ group accuracy comparison within the subject-dependent and cross-subject pain detection experiments.

Figure 10.

Females’ group accuracy comparison within the subject-dependent and cross-subject pain detection experiments.

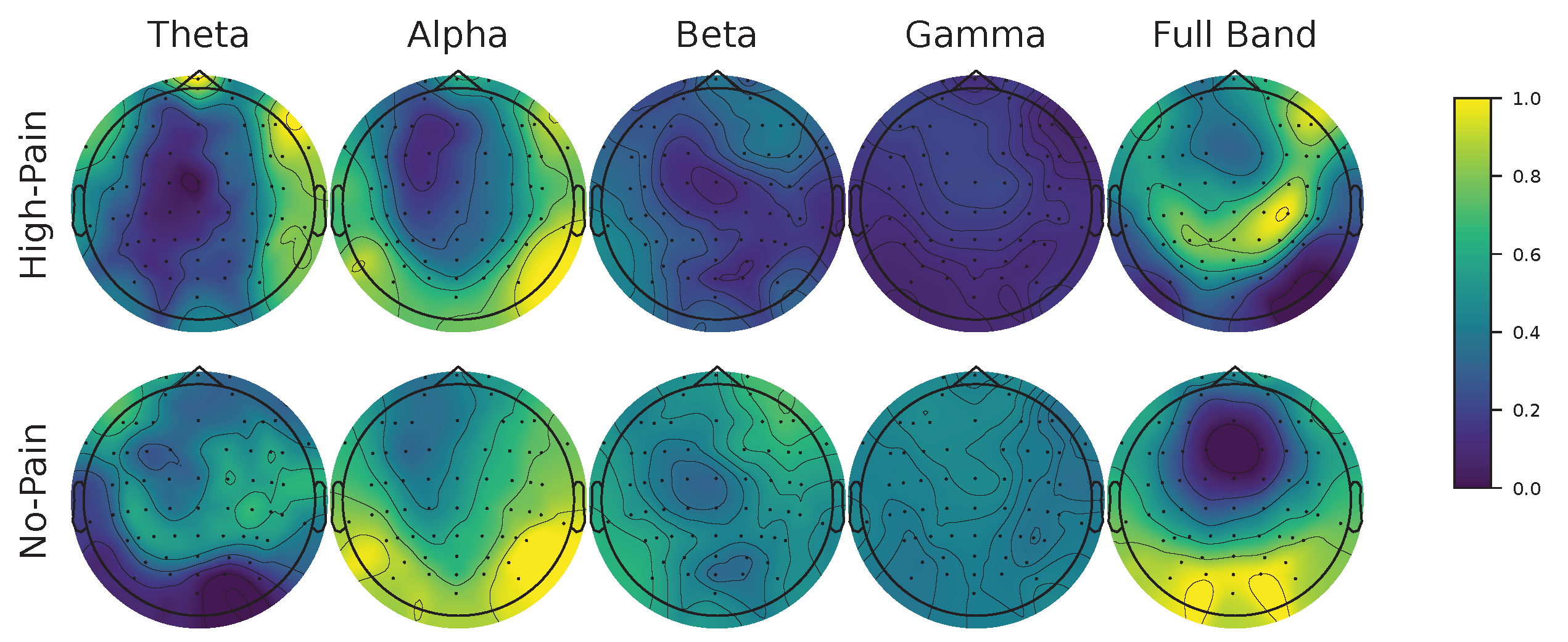

Figure 11.

FCAM-based spatio-frequency results. We present Subject 15 as a representative male subject. Theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), gamma (30-60 Hz), and full-band (4-60 Hz) are shown. FCAM relevance vector is normalized between 0 and 1, considering both no-pain and high-pain pain detection classes.

Figure 11.

FCAM-based spatio-frequency results. We present Subject 15 as a representative male subject. Theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), gamma (30-60 Hz), and full-band (4-60 Hz) are shown. FCAM relevance vector is normalized between 0 and 1, considering both no-pain and high-pain pain detection classes.

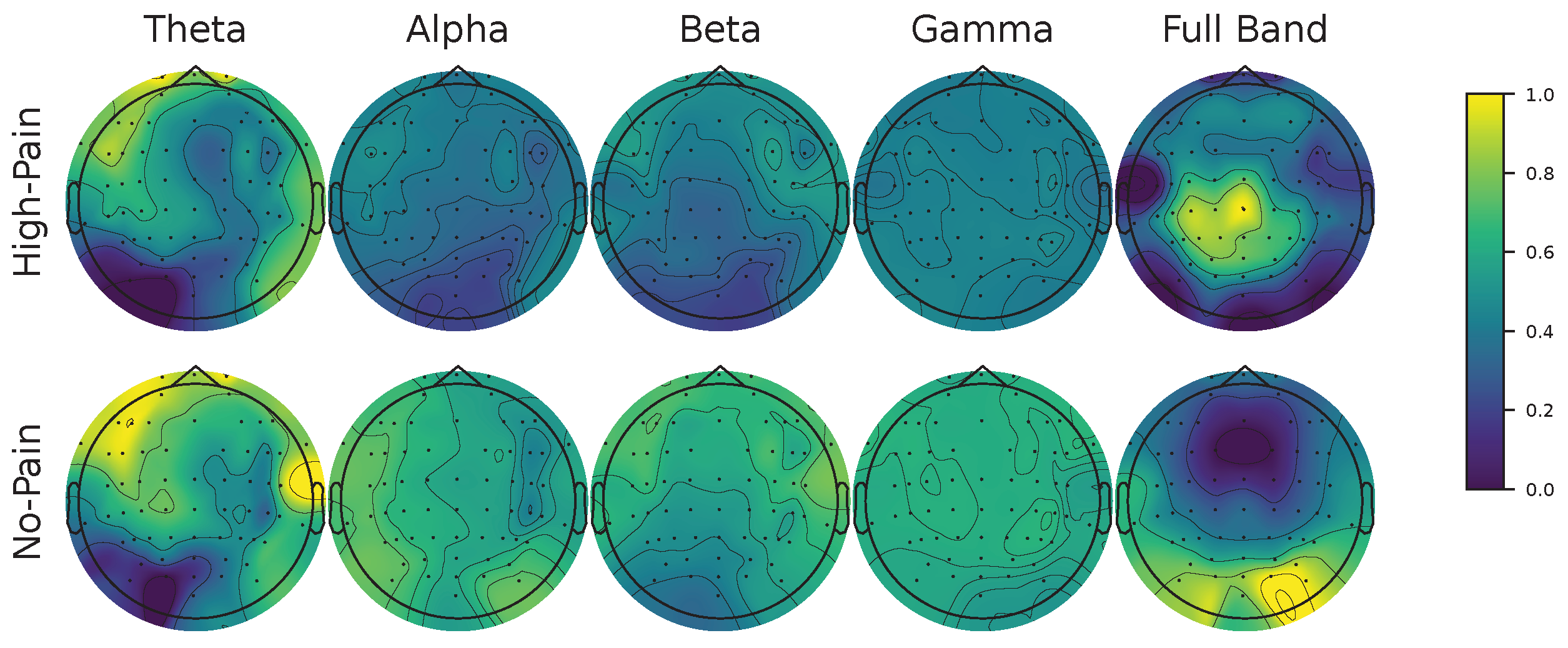

Figure 12.

FCAM-based spatio-frequency results. We present Subject 29 as a representative female subject. Theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), gamma (30-60 Hz), and full-band (4-60 Hz) are shown. FCAM relevance vector is normalized between 0 and 1, considering both no-pain and high-pain pain detection classes.

Figure 12.

FCAM-based spatio-frequency results. We present Subject 29 as a representative female subject. Theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), gamma (30-60 Hz), and full-band (4-60 Hz) are shown. FCAM relevance vector is normalized between 0 and 1, considering both no-pain and high-pain pain detection classes.

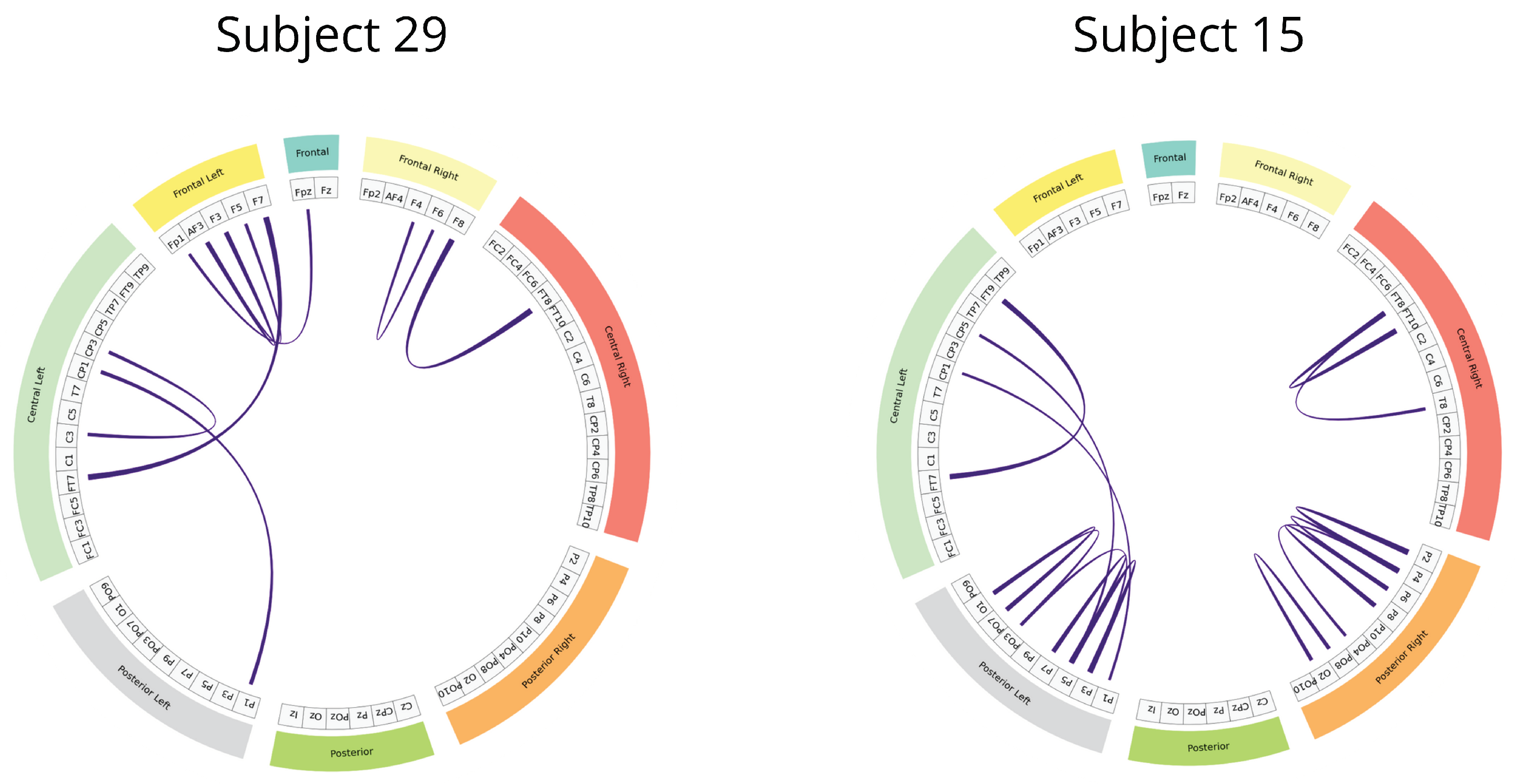

Figure 13.

KCS-FCNet-derived Gaussian functional connectivity patterns for representative subjects: female (Subject 29) and male (Subject 15). 2KS-based pruning is carried out to preserve discriminative FC with p-value

. Then, connections exceeding 97% of the maximum relevance value are retained for visualization. Colored brain regions within the graph are related to

Figure 1.

Figure 13.

KCS-FCNet-derived Gaussian functional connectivity patterns for representative subjects: female (Subject 29) and male (Subject 15). 2KS-based pruning is carried out to preserve discriminative FC with p-value

. Then, connections exceeding 97% of the maximum relevance value are retained for visualization. Colored brain regions within the graph are related to

Figure 1.

Table 1.

Brain Mediators of Pain database demographic information summary.

Table 1.

Brain Mediators of Pain database demographic information summary.

| Attribute |

Value |

| Men |

26 |

| Women |

25 |

| Min Age |

20 |

| Max Age |

37 |

| Mean Age |

|

Table 2.

Deep learning hyperparameter setting.

Table 2.

Deep learning hyperparameter setting.

| Training Hyperparameter |

Argument |

Value |

| |

Monitor |

Training Loss |

| |

Factor |

0.1 |

| Reduce learning rate on plateau |

Patience |

30 |

| |

Min Delta |

0.01 |

| |

Min Learning Rate |

0 |

| Adam |

Learning Rate |

0.1 |

| Stratified Shuffle Split |

Splits |

5 |

| |

Test size |

0.2 |

Table 3.

Detailed KCS-FCNet Architecture for pain detection.

Table 3.

Detailed KCS-FCNet Architecture for pain detection.

| Layer |

Output shape |

Params |

| Input |

(C, T, 1) |

. |

| Conv2D |

(C, , ) |

max norm=, kernel size=, Stride size=, Bias=False |

| BatchNormalization |

(C, , ) |

. |

| |

ELU Activation |

| FC Block |

(, , 1) |

. |

| AveragePooling2D |

(1, , 1) |

. |

| BatchNormalization |

(1, , 1) |

. |

| |

ELU Activation |

| Flatten |

|

. |

| Dropout |

|

Dropout rate =

|

| Dense |

|

Max Norm =

|

| |

Softmax |

Table 4.

Average subject-dependent pain detection performance. Standard deviation is also included. − stands for not provided.

Table 4.

Average subject-dependent pain detection performance. Standard deviation is also included. − stands for not provided.

| Approach |

Accuracy |

Kappa |

AUC |

| Power features + SVM [40] |

56.5 ± 7.5 |

– ± – |

– ± – |

| FBCSP [45] |

53.0 ± 3.8 |

5.9 ± 7.6 |

53.0 ± 3.8 |

| EEGNet [46] |

62.5 ± 9.9 |

24.9 ± 19.7 |

64.6 ± 14.7 |

| KCS-FCnet (ours) |

76.4 ± 9.1 |

52.8 ± 18.1 |

81.2 ± 11.5 |

Table 5.

Gender-based group distribution. Male and female subjects with subject-dependent are considered.

Table 5.

Gender-based group distribution. Male and female subjects with subject-dependent are considered.

| Group |

Subjects |

Min Age |

Max Age |

Average Age |

| Females |

1, 10, 12, 23, 29, 46 |

20 |

36 |

26.5 ± 3.9 |

| Males |

15, 19, 21, 25, 27 |

22 |

33 |

27.1 ± 3.5 |

Table 6.

Male cross-subject pain detection results. A LOSO cross-validation is carried out. Average ACC and standard deviation are presented.

Table 6.

Male cross-subject pain detection results. A LOSO cross-validation is carried out. Average ACC and standard deviation are presented.

| Approach |

Accuracy |

Kappa |

AUC |

| FBCSP [45] |

57.6 ± 7.8 |

15.3 ± 15.6 |

57.7 ± 7.8 |

| EEGNet [46] |

77.7 ± 3.7 |

55.5 ± 7.5 |

86.5 ± 3.7 |

| KCS-FCNet (ours) |

80.8 ± 6.4 |

61.6 ± 12.8 |

90.8 ± 7.7 |

Table 7.

Female cross-subject pain detection results. A LOSO cross-validation is carried out. Average ACC and standard deviation are presented.

Table 7.

Female cross-subject pain detection results. A LOSO cross-validation is carried out. Average ACC and standard deviation are presented.

| Approach |

Accuracy |

Kappa |

AUC |

| FBCSP [45] |

62.5 ± 10.1 |

25.0 ± 20.2 |

62.5 ± 10.1 |

| EEGNet [46] |

63.3 ± 10.6 |

26.6 ± 21.1 |

78.3 ± 17.9 |

| KCS-FCNet (ours) |

67.5 ± 14.0 |

35.0 ± 28.1 |

80.9 ± 18.3 |