1. Introduction

Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) R.M.King & H.Rob. [Synonym:

Eupatorium adenophorum (Spreng.) R.M.King & H.Rob.], is a perennial herbaceous plant that can grow up to 1–3 meters tall, belongs to the family Asteraceae. The species exhibits facultative clonal propagation through adventitious root formation at nodal meristems upon soil contact, facilitating rapid colonization and the establishment of dense mono-cultural thickets that competitively displace native vegetation. Each plant can produce approximately ten thousand seeds per season, which usually dispersed by wind, water and animals [

1]. Seeds or rooted branches grow relatively fast in a variety of environments under different site-specific scenarios, such as roadsides, steep slopes, farmlands, grassland, wetland along streams, railway embankments, forests, and plantations [

2]. This invasive species leads the displacement of native plant communities through the emission of allelopathic volatile organic compounds (VOCs), thereby promoting the establishment of ecologically destabilizing mono-cultural stands [

3].

Ageratina adenophora originally endemic to Mexico and Costa Rica, has emerged as a globally invasive species, establishing naturalized populations in over 40 countries spanning Asia, Australia, Africa, and Europe, with significant ecological and economic consequences [

2,

4,

5]. The introduction of this invasive species into Yunnan province of China, during the 1940’s is attributed to its translocation from Myanmar [

6,

7]. Since then, It has spread rapidly throughout the western China, including Guizhou, Sichuan, and Guangxi provinces [

8], and still continuing to expand its range in north and east of China at a rate of 60 kilometers per year [

7,

9]. This species has been considered as seriously invasive weed in many countries [

2].

Herbicides are engineered for the selective suppression of competitive flora to address escalating global agricultural demands for sustainable crop yields. Among these, benzoic acid derivatives constitute a critical class of phytochemical agents, demonstrating targeted efficacy in monocot-dominated agro-ecosystems by selectively controlling dicotyledonous weeds in staple crops such as

Triticum aestivum (wheat) and

Zea mays (maize) [

10]. At present, there are six main herbicides in this category including sethoxydim, quizalofop, fluazifop, clethodim, chlorpyrifos methyl ester, and imazethapyr; however, all of these are relatively low-toxic herbicides [

11]. Shen et al. (2013) demonstrated that 2-(4-hydroxybenzoyl) quinazoline-4(3H)-one and methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate exhibit potent antiviral activity through the inhibition of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) replication [

12]. Subsequent investigations have further revealed that methyl 2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoate demonstrated significant phytotoxic activity, suppressing root elongation in radish and rice paddy weeds with efficacy comparable to the widely utilized herbicide glyphosate, likely mediated via ROS accumulation and auxin signaling disruption [

13].

Pesticides may have an impact on the stomata of plant leaves. Stomata are essential channels through which plants exchange substances between and with their environment. Carbon dioxide directly enters the plant through stomata, participating in the dark reactions of photosynthesis, while oxygen produced by photosynthesis is also released through the stomata [

14,

15]. Some plant pesticides may cause the complete stomata closure or partial closure. For instance, certain plant growth regulators, if applied at high concentrations, can disrupt the plant's hormonal balance, which plays a crucial role in regulating the stomatal opening and closing [

16,

17]. Once the stomata are closed, the supply of carbon dioxide becomes insufficient, which prevents the Calvin cycle in the dark reactions from proceeding smoothly due to a lack of raw materials. The dark reactions primarily involve steps such as the fixation of carbon dioxide, reduction, and regeneration of RuBP (ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate) [

18]. A reduction in carbon dioxide supply will lower the rate of carbon fixation, affecting the entire dark reaction process and ultimately reducing the efficiency of photosynthesis [

19,

20]. At the same time, the release of oxygen is also hindered, leading to a relative increase in oxygen concentration within the leaves, which could trigger enhanced photorespiration process. Photorespiration consumes the energy and organic compounds produced by photosynthesis, further damaging the plant's photosynthesis efficiency [

21].

This study profoundly evaluates the herbicidal potential of hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives against A. adenophora, employing a phytochemical screening approach to identify lead compounds with selective inhibitory activity for invasive weed management. By applying different concentrations of these compounds, this study systematically evaluates their impact on the growth status of A. adenophora and examines the effects of effective compounds on cell viability, CO₂ assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, and plant hormone levels. Here, we aimed to address the following key questions: (1) which compound can effectively inhibit the growth of A. adenophora, and does its effect exhibit a dose-dependent relationship? (2) what is the effect of this compound on the photosynthesis and stomatal regulation of A. adenophora? (3) what changes have occurred in the levels of plant hormones? This study will establish a foundational framework for the development of targeted biochemical strategies to mitigate the proliferation of A. adenophora, offering critical insights into novel phytotoxic mechanisms for sustainable invasive species management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compound Screening

The compound screening experiment was conducted between 2021 to 2024 in Kunming, Yunnan province (102.739° E, 25.139° N), China by using wild adult

A. adenophora plants. Seeds of wild

A. adenophora were collected and sown in the greenhouse of the Germplasm Bank at the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Seven phenyl compounds including ethylparaben, methylparaben, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, ethyl benzoate and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethanol were screened (purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Reagent Co., Shanghai, China), as shown in

Figure 1.

The compounds exhibit limited aqueous solubility, necessitating the utilization of organic solvents—including ethanol, methanol, diethyl ether, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and petroleum ether—for effective dissolution and subsequent experimental applications. Due to relatively low environmental impacts, ethanol was chosen as the solvent to minimize environmental pollution, in the present experiment. Different phenyl compounds require different concentrations of ethanol for dissolution. While we are searching for effective compounds to control A. adenophora, we are also mindful of testing whether ethanol is harmful to the plants or any other negative impacts. The compound was administered exclusively through foliar application to the entire leaf surface under controlled experimental conditions, with rigorous measures implemented to minimize soil infiltration and prevent cross-contamination.

Each compound was sprayed on the leaves of mature A. adenophora plants at concentrations of 50 mM, 100 mM, 150 mM, and 200 mM. The reaction of plants was check at 24 hours after spraying.

Since only methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate significantly inhibited the growth of A. adenophora (see Results), we then only further screened its function on 2-month-old and 3-month-old seedlings using different concentrations. For 2-month-old seedlings were sprayed with methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate at concentrations of 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, and 30 mM. For 3-month-old seedlings were sprayed with concentrations of 40 mM, 60 mM, 80 mM, and 100 mM. For 6-month-old plants, the applied concentrations were 50 mM, 100 mM, 150 mM, and 200 mM. All treatments were repeated using 5–16 plants. For 6-month-old plants, 200 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate can effectively kill the whole plant by 48 hours, then was used in subsequent physiological index detection experiments.

2.2. Cell Viability and Apoptosis Detection

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) can be used to detect plant cell structure, dynamics, and the process of cell death [

22]. This microscope generates three-dimensional images of cells using fluorescence signals [

23]. Since only young leaves are suitable for observation using CLSM, we used the top-most fully expanded leaves of 4-month-old A. adenophora plants for the experiment. One leaf was sprayed with 200 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, while another leaf was left untreated as a control. We observed the changes in the treated and control leaves at 0 minute, 10 minutes, 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 120 minutes, and 240 minutes.

The selected leaves were cut with scissors and placed into petri dishes containing double-distilled water (ddH₂O), gently rinsed, and removed water. The excess water was blotted off with filter paper. Next, the leaves were immersed in a 1:1 mixture of FDA (fluorescein diacetate) and PI (propidium iodide) in the dark for 2–3 minutes. Afterward, the leaves were taken out and cut into small pieces about 0.5 cm wide and 1 cm long with the help of a scalpel. These pieces were placed on a microscope slide, covered with a coverslip, and observed under a laser confocal microscope, Olympus FV1000, Tokyo, Olympus (Tokyo, Japan). Under blue light excitation at approximately 490 nm, living cells in the leaf were appeared green and we clearly visible. Under green light excitation at 550–590 nm, dead cells appeared red. This method allowed us to observe the timing of cell death in the leaf.

2.3. Stomatal Conductance and CO2 assimilability Measurement

Twelve A. adenophora plants at 6-month-old were randomly selected. The 200mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate was sprayed on six of the plants, while the other six plants were left untreated as a control group. Gas exchange data of the leaves were measured, with one fully expanded upper leaf chosen from each plant to record the leaf gas exchange readings. Before the measurements, the leaves were allowed to acclimate to the surrounding environmental conditions, and care was taken not to touch the leaf surface to avoid stomatal closure. Ambient temperature was regulated at 18–25°C between 11:00 and 15:00 hours throughout the experimental protocol to ensure consistency in environmental conditions.

Gas exchange was measured using a portable open-path infrared gas analyzer system (LI-6400XT; Li-Cor Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA), with an added leaf chamber fluorometer (Li-Cor Part No. 6400-40, closed leaf area: 2 cm²). The system’s gas flow was set at 300 mmol min⁻¹, and the light intensity was set to saturation (1000 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹, with 10% blue light and 90% red light). After a 5-minute light adaptation period, the net CO₂ assimilation rate and stomatal conductance were measured under the conditions of 1500 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ light intensity and 400 μmol mol⁻¹ CO₂ concentration, respectively. These measurements were used to check the stomatal conductance of the plant leaves.

2.4. Hormone Detection

After spraying 200 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, the above-ground parts of 4-month-old

A. adenophora plants were collected to extract six plant hormones: indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellins (GA1 and GA3), and cytokinins (trans-zeatin (TZeatin) and trans-zeatin riboside (TZR)), with measurements taken at 0 minute, 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 120 minutes, and 240 minutes post-treatment. The average data from three replicate experiments were recorded. Additionally, the hormone levels were also examined following the spraying of 20% alcohol as a control group. The extraction and determination of the six hormones were conducted by Nanjing Weibo Technology Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China), using previously described methodology of Kojima et al., 2009 and Liu et al., 2010 [

24,

25].

3. Results

3.1. Compound Screening Results

The effects of ethylparaben, methylparaben, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, ethyl benzoate and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethanol on wild adult A. adenophora plants at different concentrations are as follows: when the compound concentration is 50mM or 100 mM or lower, plant growth remains normal within 48 hours, with no abnormal reactions being observed. However, when the concentration increases to 150 mM, the buds of A. adenophora sprayed with methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate died at 48 hours after treatment, while no significant reactions were observed in plants sprayed with other six compounds. At a concentration of 200 mM, the young leaves and stems of A. adenophora sprayed with methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate wilted at 48 hours, whereas only a few buds on plants sprayed with the other six compounds wilted (Figure 2.1, 2.2).

Figure 2.1.

The comparison chart of A. adenophora before and after 24 hours of spraying with four compounds at a concentration of 200 mM. 1: ethylparaben; 2: methylparaben; 3: 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid; 4: 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid; A: Before spraying; B: 24 hours after spraying; a, b, c, d, e represent five replicates for the same treatment.

Figure 2.1.

The comparison chart of A. adenophora before and after 24 hours of spraying with four compounds at a concentration of 200 mM. 1: ethylparaben; 2: methylparaben; 3: 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid; 4: 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid; A: Before spraying; B: 24 hours after spraying; a, b, c, d, e represent five replicates for the same treatment.

Figure 2.2.

The comparison chart of A. adenophora before and after 24 hours of spraying with three compounds at a concentration of 200 mM. 5: methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate; 6: ethyl benzoate; 7: 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) ethanol; A: Before spraying; B: 24 hours after spraying; a, b, c, d, e represent five replicates for the same treatment.

Figure 2.2.

The comparison chart of A. adenophora before and after 24 hours of spraying with three compounds at a concentration of 200 mM. 5: methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate; 6: ethyl benzoate; 7: 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) ethanol; A: Before spraying; B: 24 hours after spraying; a, b, c, d, e represent five replicates for the same treatment.

For 2-month-old

A. adenophora seedlings, when 5 mM, 10 mM and 20 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate were sprayed, plants grew largely normal within 48 hours. After spraying with 30 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, a few of leaves began to wilt by 5 hours, a large amount of leaves wilted after 24 hours, and most leaves of the plants or whole plants wilted after 48 hours (

Figure 3).

For 3-month-old seedlings, when 40 mM, 60 mM and 80 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate were sprayed, plants grew largely normal within 48 hours. However, when treated with an 100 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, a few of leaves began to wilt after 5 hours, a large amount of leaves wilted after 24 hours, and all seedlings died within 48 hours (

Figure 4).

For 6-month-old seedlings, when 50 mM and 100 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate were sprayed, plants grew largely normal within 48 hours. At a concentration of 150 mM, the topmost two pairs of leaves died within 48 hours. At a concentration of 200 mM, all plants began to wilt within 1 hour, and were completely dead within 48 hours (

Figure 5).

In the control experiment, alcohol at concentrations of 20% showed no significant effect on the growth of A. adenophora (

Figure 3, 4).

3.2. Cell Vitality and Apoptosis Time

The topmost, fully expanded leaves sprayed with a 200 mM solution of methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate began to turn dark green within 30 minutes, and completely wilted within 240 minutes (

Figure 6 A1-A6).

Regarding cell vitality, no changes were observed within 10 minutes after spraying with methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate (

Figure 6 B2, C2). Within 30 minutes, the number of green, viable cells decreased (

Figure 6 B3, C3). After 1 hour, red and dead cells appeared (

Figure 6 B4, C4). After 2 hours, the number of red and dead cells significantly increased (

Figure 6 B5, C5). After 4 hours, all green and viable cells were not visible, and only red and dead cells were observed (

Figure 6B,C).

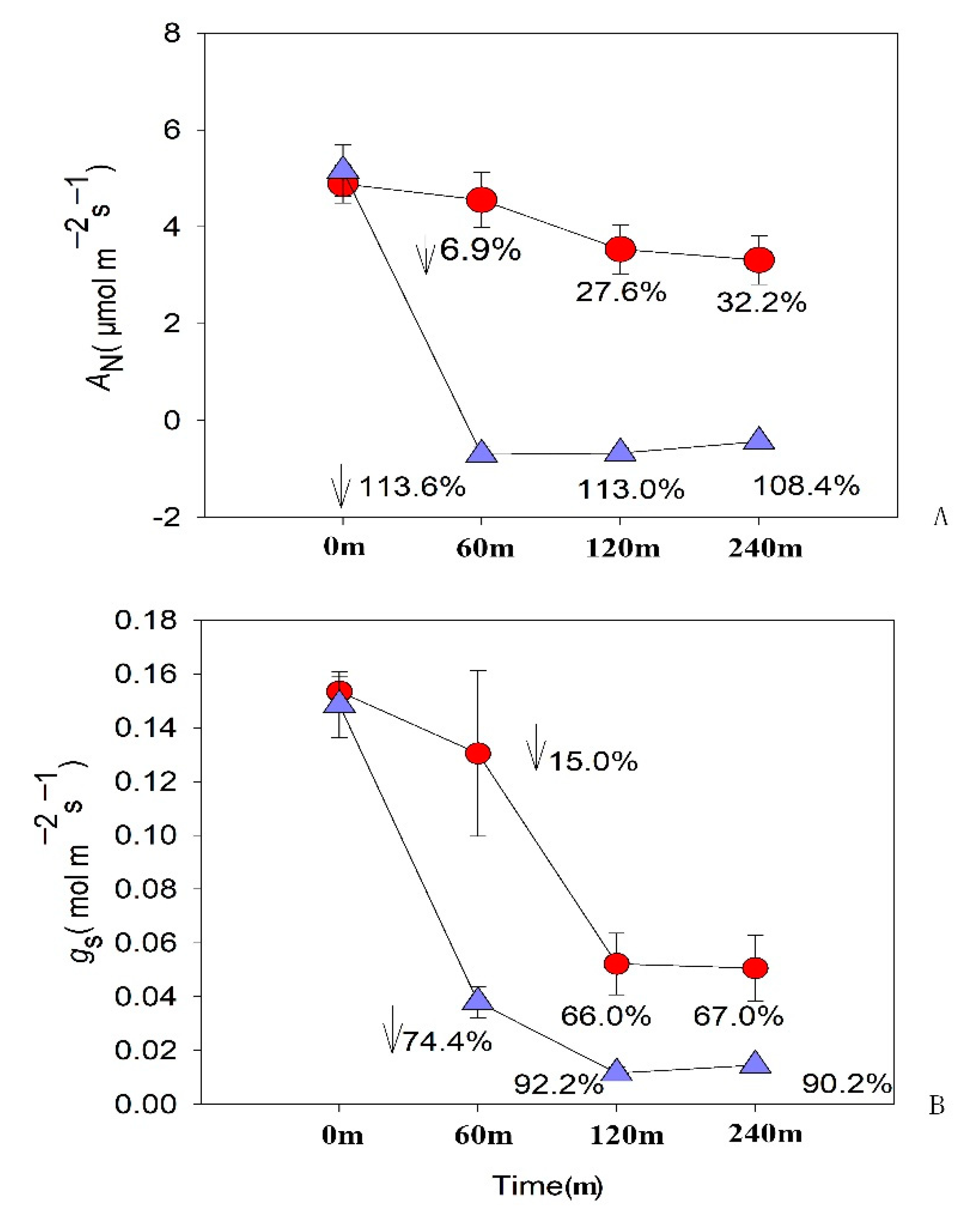

3.3. CO₂ Assimilation Rate and Stomatal Conductance

Before spraying 200 mM methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate on 6-month-old

A. adenophora, the leaf CO₂ assimilation rate of the control group and the treatment group were almost identical, at 4.886 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 5.159 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹, respectively (

Figure 7, 7-A,

Table S1). One hour after spraying, the CO₂ assimilation rate of the control group slightly decreased to 4.551 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹, while the treatment group sharply dropped to a negative value of -0.701 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. Two and four hours after spraying, the control group showed a slight reduction to 3.537 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 3.314 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹, while the treatment group remained negative at -0.672 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ and -0.433 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. At the 4th hour of the experiment, the CO₂ assimilation rate of the control group decreased by a maximum of 32.2%, while at the 1st hour, the CO₂ assimilation rate of the treatment group decreased by a maximum of 113.6%. This finding demonstrates that the pesticide exerted a significant inhibitory effect on the CO₂ assimilation rate in

A. adenophora foliage within one hour post-application, suggesting rapid physiological disruption of photosynthetic machinery.

The stomatal conductance of

A. adenophora leaves before and after spraying with methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate is shown in

Figure 7 and

Table S2. Before spraying, the stomatal conductance of the control group and the treatment group were almost identical, at 0.153 mol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 0.149 mol m⁻² s⁻¹, respectively. One hour after spraying, both groups showed a decreasing trend, with the control group dropping to 0.130 mol m⁻² s⁻¹, while the treatment group sharply declined to 0.038 mol m⁻² s⁻¹. Two and four hours after spraying, the control group showed stomatal conductance of 0.052 mol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 0.051 mol m⁻² s⁻¹, while the treatment group exhibited a more severe decline at 0.012 mol m⁻² s⁻¹ and 0.015 mol m⁻² s⁻¹, as shown in

Figure 7; 7-B. At the 4th hour of the experiment, the stomatal conductance of the control group decreased by a maximum of 67.0%, while at the 2nd hour, the stomatal conductance of the treatment group decreased by a maximum of 92.2%.

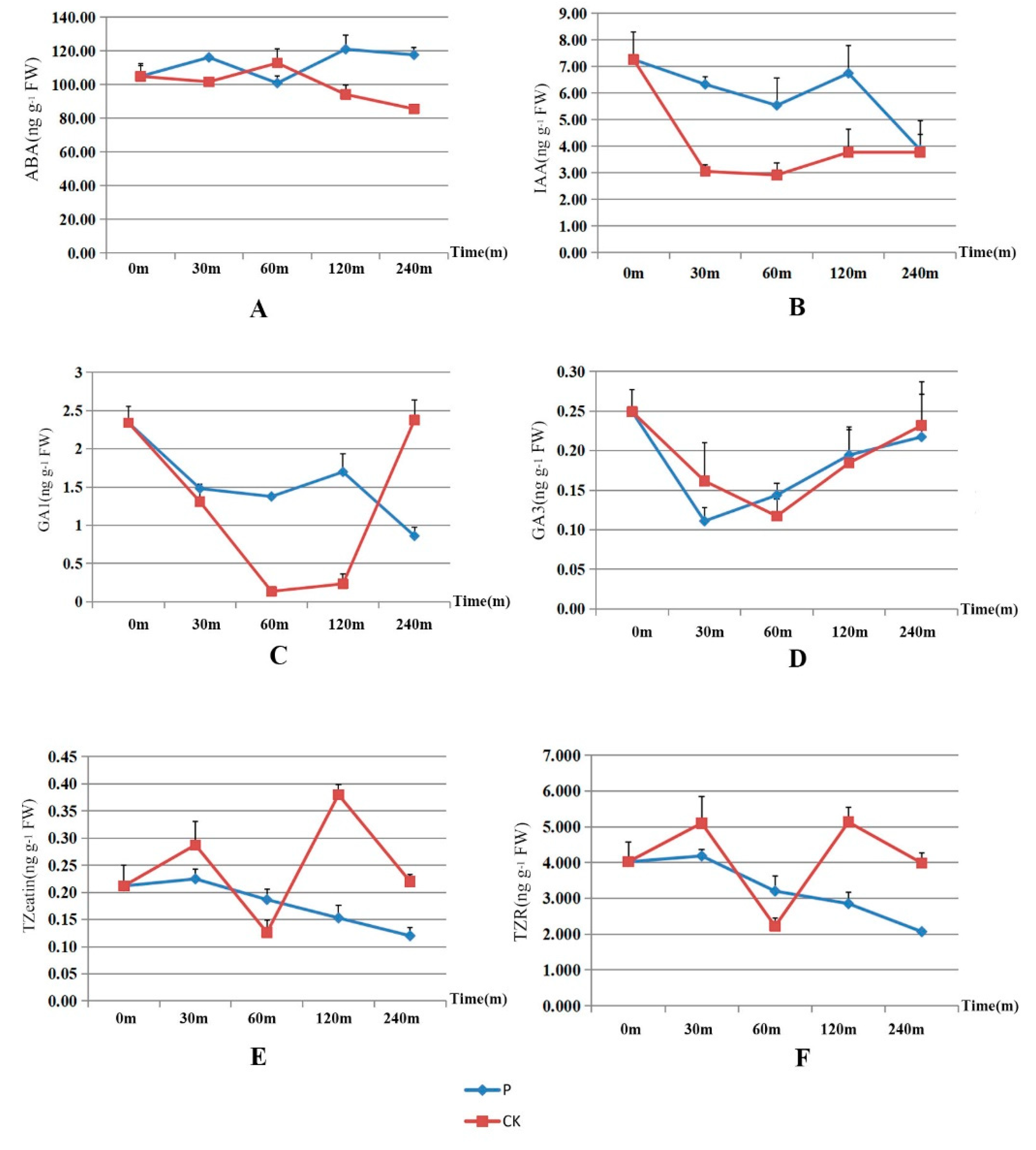

3.4. Hormonal Changes

Changes of six hormones were shown in

Figure 8 and

Table S3. For whole plants of 4-months-old without sprayed alcohol and methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, the average content of ABA, IAA, GA1, GA3, TZeatin and TZR per gram of fresh weight (FW) was 104.890 ng, 7.262 ng, 2.341 ng, 0.249 ng, 0.212 ng and 4.023 ng, respectively. Thirty minutes after sprayed methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, the plant hormones were 112.810 ng, 6.327 ng, 1.480 ng, 0.111 ng, 0.218 ng and 4.186 ng, respectively. Thirty minutes after spraying with 20% alcohol, the plant hormones were 101.657 ng, 3.054 ng, 1.309 ng, 0.162 ng, 0.287 ng and 5.102 ng, respectively. One hour after spraying with methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, the values were 134.220 ng, 5.538 ng, 1.376 ng, 0.110 ng, 0.187 ng and 3.203 ng, respectively. One hour after spraying 20% alcohol, the values were 112.767 ng, 2.917 ng, 1.137 ng, 0.117 ng, 0.133 ng and 2.224 ng, respectively. Two hours after spraying sprayed methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, the values were 124.313 ng, 6.744 ng, 1.698 ng, 0.228 ng 0.120 ng and 2.853 ng, respectively. Two hours after spraying 20% alcohol, the values were 94.180 ng, 3.773 ng, 0.234 ng, 0.185 ng, 0.380 ng and 5.131 ng, respectively. Four hours after spraying sprayed methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, the values were 120.983 ng, 3.866 ng, 0.861 ng, 0.217 ng, 0.149 ng and 2.070 ng, respectively. Four hours after spraying alcohol, the values were 85.540 ng, 3.777 ng, 2.375 ng, 0.232 ng, 0.225 ng and 3.989 ng, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the inhibitory effects of seven phenyl compounds on the growth of

A. adenophora, and the results showed that the methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate exhibited a significant inhibitory effect on the growth of this species. Methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate is widely present in the extracts of various plants, fungi, and actinomycetes [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], and has been used as an intermediate in chemical synthesis for a long time [

31,

32,

33]. However, studies on its biological function on plant growth are relatively limited in context of biochemical control. While Shen et al. (2013) previously demonstrated the inhibitory activity of methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate against tobacco mosaic virus [

12], this study provides the first empirical evidence of its phytotoxic efficacy in suppressing

A. adenophora growth, underscoring its potential as a dual-function agent for targeted plant growth regulation and sustainable invasive weed management.

The experimental results indicated that the CO₂ assimilation rate of

A. adenophora leaves rapidly dropped to a negative value 60 minutes after the compound application, suggesting that the pesticide had already caused damage to the leaves. The phenomenon of negative CO₂ assimilation rate following compound application is typically due to the compound interfering with the plant's physiological processes, thereby hindering photosynthesis [

34]. The phytotoxic effects observed are likely attributable to herbicidal-induced cellular degradation and necrosis in foliar tissues, which disrupt chloroplast ultrastructure and consequently impair photosynthetic efficiency [

34]. On the other hand, in some cases, this may even lead to a situation where the consumption of photosynthetic products exceeds the CO₂ absorption, ultimately resulting in a negative CO₂ assimilation rate [

34,

35,

36].

Stomata play a crucial role in plant photosynthesis, serving as the primary channels for carbon dioxide (CO₂) absorption and water vapor transpiration [

37]. When plants face external stressors, they need to regulate the balance between carbon dioxide absorption and water evaporation through stomatal movement control [

38]. In our study, the control group also showed a decrease in stomatal conductance after 120 minutes, mainly due to intense sunlight potentially causing an increase in leaf temperature, which intensified water evaporation. The plant then regulates stomatal conductance and closes some stomata to reduce excessive water loss [

39]. In the treatment group, stomatal conductance sharply decreased 60 minutes after spraying, primarily because, after the compound application, the plant might experience oxidative stress, root or leaf damage, and other phenomena, which in turn trigger defense responses. By regulating the synthesis of plant hormones such as auxins, the plant closes the stomata to reduce water loss and prevent harmful substances from continuing to enter the plant [

40,

41]. The dynamic modulation of stomatal guard cell aperture represents a critical adaptive mechanism by which plants mitigate environmental stressors, mediated through phytohormone-regulated ion channel gating that governs transmembrane solute flux. Stomatal closure is mainly due to anion release and/or Ca²⁺ uptake, which leads to plasma membrane depolarization (the membrane potential moves toward a more positive value) [

42]. This depolarization phenomenon drives the reduction of K⁺ and malate, promoting the release of water from guard cells and their contraction, thus closing the stomata [

42,

43,

44]. These processes are regulated by hormones within the plant, with abscisic acid (ABA), auxin (IAA), and gibberellin (GA) playing key roles [

45,

46,

47].

Among the six phytohormones assayed, abscisic acid (ABA) exhibited a singular significant increase in concentration. ABA accumulation serves a dual physiological role: it induces stomatal closure to minimize transpirational water loss and fortifies the plant’s defense by restricting the influx of deleterious exogenous agents through compromised epidermal barriers. In the ABA-induced stomatal closure process, the open stomata 1 kinase increases, and the levels of reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, and Ca²⁺ rise, which in turn activate Ca²⁺-dependent CDPKs, promoting ion efflux in guard cells and forcing the stomata to close [

48,

49]. Stomatal closure and the influence of hormones may be one of the earlier steps in the defense response and an essential component of the plant’s innate immune response [

50,

51].

The levels of the other five hormones decreased sharply or fluctuated after spraying. The herbicide can inhibit the synthesis or transport of IAA, leading to a decrease in IAA levels, which in turn affects the normal opening and closing of stomata. IAA usually promotes stomatal opening, while ABA promotes stomatal closure. When plants encounter oxidative stress or water stress caused by herbicides, the increase in IAA may interact with the increase in ABA. Although indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) has been reported to promote stomatal opening under specific conditions, the antagonistic role of abscisic acid (ABA) dominates stomatal closure, particularly under abiotic stress [

52]. The decrease in IAA content may be due to its interaction with ethylene concentration, which inhibits the plant's transpiration and stomatal conductance, leading to stomatal closure [

52]. The level of gibberellin (GA) activity significantly affects plant transpiration and related physiological processes. Low GA activity influences transpiration through several mechanisms: first, by inhibiting cell division and elongation, thus reducing leaf area; second, by increasing the response to ABA in guard cells, directly promoting stomatal closure; and third, by reducing xylem proliferation and expansion, lowering the hydraulic conductance of the xylem. In tomatoes, reduced GA activity also promotes stomatal closure, thereby reducing water loss under conditions of water deficit [

53]. An increase in cytokinin levels can induce the expression of photoreceptors related to stomatal opening, while inhibiting the biosynthesis and signaling of abscisic acid (ABA), thereby enhancing plant stomatal conductance. In addition, cytokinins strictly regulate the biosynthesis of chlorophyll and the expression of key proteins involved in the assembly and activation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), helping plants maintain an appropriate photosynthetic rate under drought stress conditions [

54]. Herbicide-induced phytotoxicity in plants is modulated through complex phytohormonal crosstalk, yet the multifactorial mechanisms governing these interactions remain poorly characterized, necessitating comprehensive investigation to elucidate underlying regulatory networks.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate exhibits significant phytotoxic activity against A. adenophora seedlings, positioning it as a viable candidate for sustainable management of this invasive species. Further analysis revealed its disruptive effects on stomatal dynamics and phytohormonal profiles in mature A. adenophora plants. This compound significantly affected the plant's physiological functions by damaging leaf photosynthesis and stomatal conductance. This compound also significantly increased the concentration of hormones as ABA and decreased hormones as IAA, GA1, GA3, TZeatin and TZR. Future studies could further explore the mechanism of action of this compound and assess its potential in plant protection and pest control. Compared to other chemical herbicides, methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate may become a herbicide with lower environmental impacts. However, before applying this compound, its impact on other plants and the environment should be evaluated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1,S2,S3 are supplementary materials for this article.

Author Contributions

Z.Y.Y., J.B.Y. and G.X. conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; X.D. collected the data; Z.Y.Y. analysed the data; M.H., Y.R., Z.Y.Y. and G.X.W. led manuscript writing. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Funding

This research was supported financially by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32060639, 32060640, 32260704); Reserve Talents Project for Yunnan Young and Middle-aged Academic and Technical Leaders (202105AC160037, 202205AC160077); Yunnan Province Agricultural Joint Special Key Project (202301BD070001-141) .

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be found in supplementary materials or can be obtained from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Germplasm Bank of Wild Species in Southwest China for providing the greenhouse and the Molecular Biology Experiment Center, Germplasm Bank of Wild Species in Southwest China, for their technical support. Special thanks are extended to Associate Researcher Wei Huang for his guidance in photosynthesis detection, and to Senior Engineer Yanxia Jia for her guidance in using the laser confocal microscopy.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Bess, H.A.; Haramoto, F.H. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Entomology, Ottawa, Canada, 1958; Becker, E.C., Ed.; Mortimer: Ottawa, Canada, 1958; Volume 4, pp. 543–548.

- Poudel, A.S.; Jha, P.K.; Shrestha, B.B.; et al. Biology and management of the invasive weed Ageratina adenophora (Asteraceae): Current state of knowledge and future research needs. Weed Res. 2019, 59, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Dong, M.; Yu, L. Compositional and functional profiling of the rhizosphere microbiomes of the invasive weed Ageratina adenophora and native plants. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heystek, F.; Wood, A.R.; Neser, S. Biological control of two Ageratina species (Asteraceae: Eupatorieae) in South Africa. Afr. Entomol. 2011, 19, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniappan, R.; Raman, A.; Reddy, G.V.P. Ageratina adenophora (Sprengel) King and Robinson (Asteraceae). In Biological Control of Tropical Weeds using Arthropods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.K.; Cui, B.S.; Yang, Z.F. The role of road disturbance in the dispersal and spread of Ageratina adenophora along the Dian–Myanmar International Road. Weed Res. 2010, 48, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.Z. Invasion dynamics and potential spread of the invasive alien plant species Ageratina adenophora (Asteraceae) in China. Divers. Distrib. 2006, 12, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.H.; Liu, W.X.; Guo, J.Y.; et al. Invasive mechanism and control strategy of Ageratina adenophora (Sprengel). Life Sci. 2010, 11, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, F.R.; Wan, F.H.; Guo, J.Y. Determination of the population genetic structure of the invasive weed Ageratina adenophora using ISSR-PCR markers. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 56, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Kang, Z.H. Advances in pyrimidiny (oxy) thiobenzoic acid herbicides. Plant Protect. 2018, 44, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Chen, Y.; Shu, G. Biological function of Benzoic acid and advances of its application in livestock and poultry production. Siliao Gongye 2023, 44, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Li, W.; Wang, J. A novel and other bioactive secondary metabolites from a marine fungus Penicillium oxalicum 0312F1. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 22, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Pimjuk, P.; Noppawan, P.; Katrun, P. New furan derivatives from Annulohypoxylon spougei fungus. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 24, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Effects of plant protection chemicals on leaf gas exchange. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 901–905. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, N.; Ledent, J.F. Effects of pesticide treatments on photosynthesis in maize. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1998, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, L. Effects of pesticides on stomatal behavior and plant growth. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2011, 9, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Q. Interaction of plant growth regulators and environmental stress factors in plant growth and productivity. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes, G.; Ogren, W.L.; Hageman, R.H. Photosynthesis in plants: A review of the Calvin cycle. Plant Physiol. 1971, 48, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G.D.; Sharkey, T.D. Stomatal control of photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1982, 33, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Rogers, A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO₂]: Implications for climate change. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y. The effects of environmental factors on photorespiration and photosynthetic efficiency in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 105, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hepler, P.K.; Gunning, B.E.S. Confocal fluorescence microscopy of plant cells. Protoplasma 1998, 201, 121–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, W.B.; White, J.G. How the confocal laser scanning microscope entered biological research. Biology Cell 2003, 95, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, M.; Kamada-Nobusada, T.; Komatsu, H. Highly sensitive and high-throughput analysis of plant hormones using MS-probe modification and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: an application for hormone profiling in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, F.; Feng, Y.Q. Determination of cytokinins in plant samples by polymer monolith microextraction coupled with hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Methods 2010, 2, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, R.Q.; Nong, X.H.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.P.; Huang, G.L.; Luo, Y.P.; Zheng, C.J.; Chen, G.Y. A new phenol derivative isolated from mangrove-derived fungus Eupenicillium sp. HJ002. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettit, G.R.; Du, J.; Pettit, R.K.; Knight, J.C.; Doubek, D.L. Antineoplastic agents. 575. The fungus Aspergillus phoenicis. Heterocycles 2009, 79, 909–916. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, T.A.N.; Sliva, L.R.; Junior, P.T.S.; Castro, R.N.; Carvalho, M.G. A new cyclopeptide and other constituents from the leaves of Zanthoxylum rigidum Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. (Rutaceae). Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 935–939. [Google Scholar]

- Winiewski, V.; Serain, A.F.; de Sá, E.L.; et al. Chemical constituents of Sinningia mauroana and screening of its extracts for antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. Quím. Nova 2020, 43, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösecke, J.; König, W. Odorous compounds from the fungus Gloeophyllum odoratum. Flavour Fragrance J. 2000, 15, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, B.A.; Ciufolini, M.A. Approach to tetrodotoxin via the oxidative amidation of a phenol. Org. Lett. 2009, 20, 4736–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Reindl, H.; Breu, K. Antipsoriatic anthrones with modulated redox properties. 5. Potent inhibition of human keratinocyte growth, induction of keratinocyte differentiation, and reduced membrane damage by novel 10-arylacetyl-1,8-dihydroxy-9(10H)-anthracenones. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 44, 814–821. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Xing, S.T.; Yuan, W.; Wu, L.M.; Chen, X.; Zhan, C.G. Regioselective synthesis of 2- and 4-diarylpyridine ethers and their inhibitory activities against phosphodiesterase 4B. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1196, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.D.; Sultana, N. Effects of herbicides on plant growth and photosynthesis. Weed Sci. 1983, 31, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.; Mudge, D. Herbicide-induced damage to the photosynthetic apparatus. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2002, 73, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A. Effects of chemical treatments on photosynthetic activity and CO₂ assimilation rate in leaves of Eupatorium adenophorum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 88, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, T. , & Blatt, M. R. ( 164(4), 1556–1570. [CrossRef]

- Munemasa, S.; Shimoishi, Y.; Uozumi, N. Regulation of stomatal closure and opening under environmental stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, I.R.; Farquhar, G.D. Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1977, 28, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Murch, S.J.; Saxena, P.K. Role of plant hormones in regulating the development of in vitro cultures of plants. Plant Growth Regulation 2000, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Bressan, R.A. Signal transduction pathways in response to stress. Plant Cell Reports 2009, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, E.V.; Assmann, S.M. The guard cell-environment connection. Plant Physiol. 1993, 102, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, S.M. Signal transduction in guard cells, Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1993, 9, 345–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatt, M.R.; Thiel, G. Hormonal control of ion channel gating. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 1993, 44, 543–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haswell, E.S.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Stomatal development and patterning. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Role of plant hormones in the regulation of water stress tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, R.R.; Rock, C.D. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and response. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montillet, J. L.; Leonhardt, N.; Mondy, S.; Tranchimand, S.; Rumeau, D.; Boudsocq, M. An abscisic acid-independent oxylipin pathway controls stomatal closure and immune defense in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Adachi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Mori, I. C.; Murata, Y. Open stomata 1 kinase is essential for yeast elicitor-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, P.; Gahir, S.; Raghavendra, A.S. Abscisic Acid-Induced Stomatal Closure: An Important Component of Plant Defense Against Abiotic and Biotic Stress. Fronties in Plant Science 2021, 12, 615144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.W.; Baek, W.; Jung, J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.C. Function of ABA in stomatal defense against biotic and drought stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 15251–15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daszkowska-Golec, A. , & Szarejko, I. (2013). Open or close the gate – stomata action under the control of phytohormones in drought stress conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 4, 138. [CrossRef]

- Nir, I.; Shohat, H.; Panizel, I.; Olszewski, N.; Aharoni, A.; Weiss, D. The tomato DELLA protein PROCERA acts in guard cells to promote stomatal closure and reduce water loss under water deficiency. The Plant Cell 2017, 29, 3186–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjar, R.S.; Sharma, S.; Yadav, V. Cytokinin-mediated regulation of abscisic acid biosynthesis and stomatal function in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 174, 104020. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).