Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strains

2.2. Growth of Fungal Strains on a Medium with the Addition of Heavy Metals

2.3. EPS Isolation and Chemical Characterisation

2.4. Estimation of the Sugar Polymer Masses by a Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

2.5. Binding of Metal Ions

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

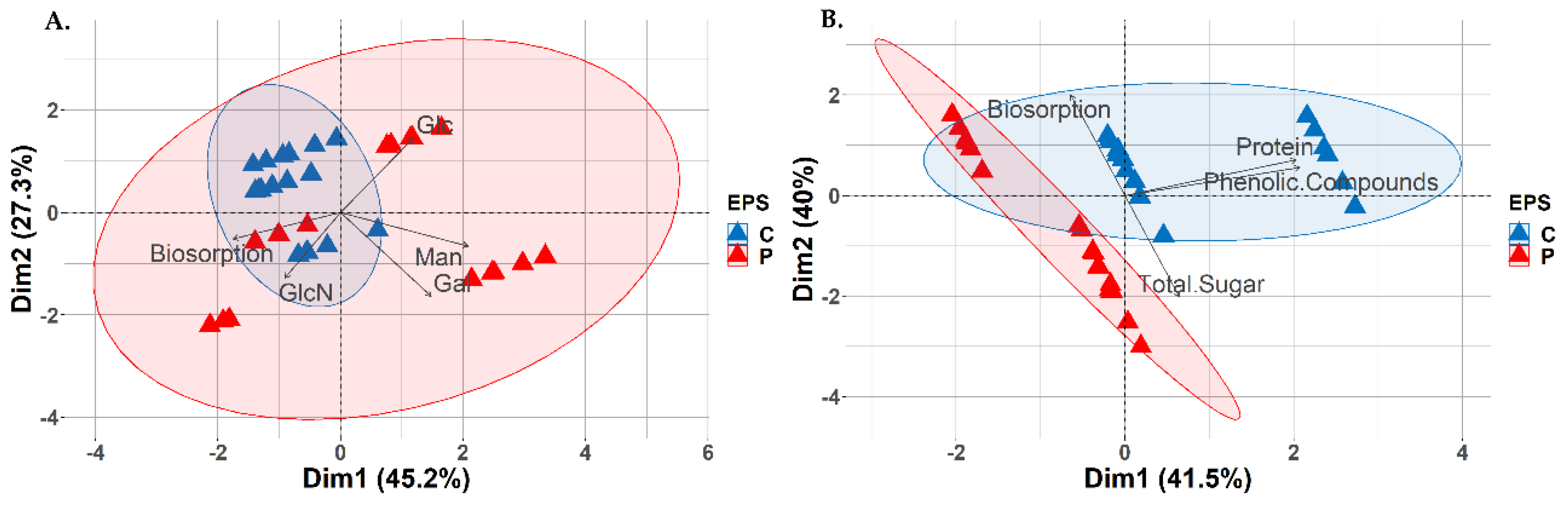

3.1. Isolation and Chemical Characterization of F. culmorum EPS Preparations

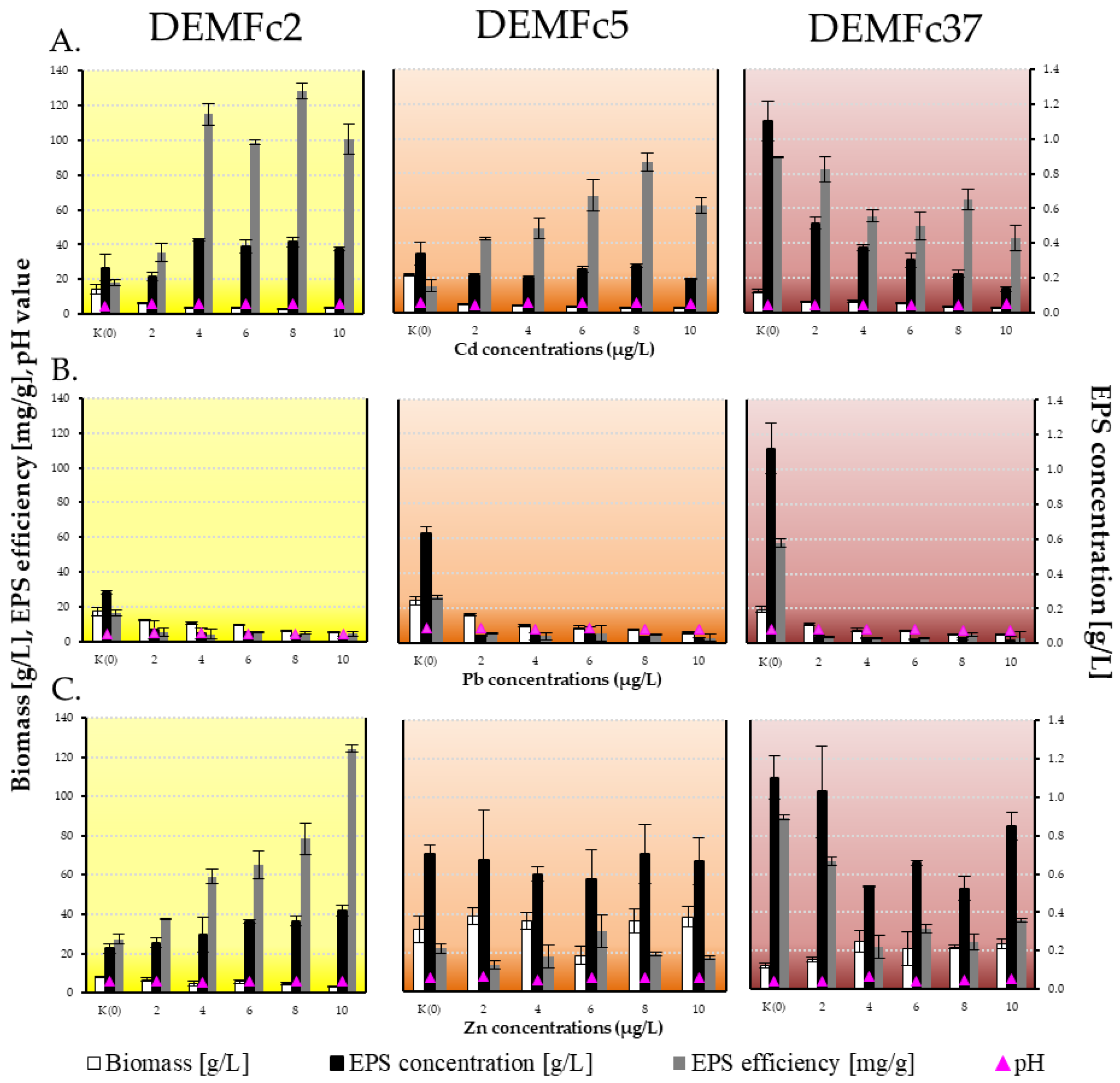

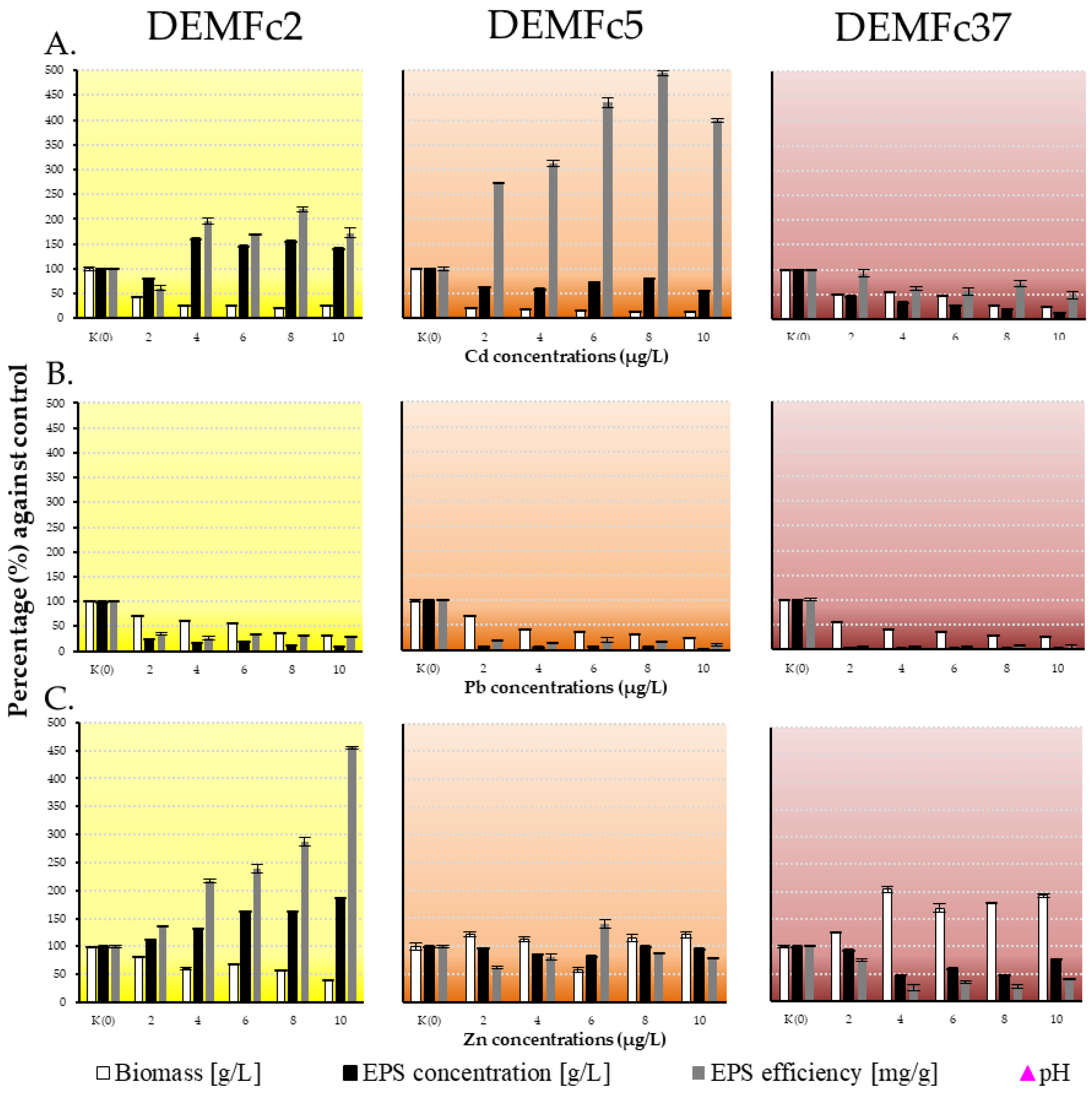

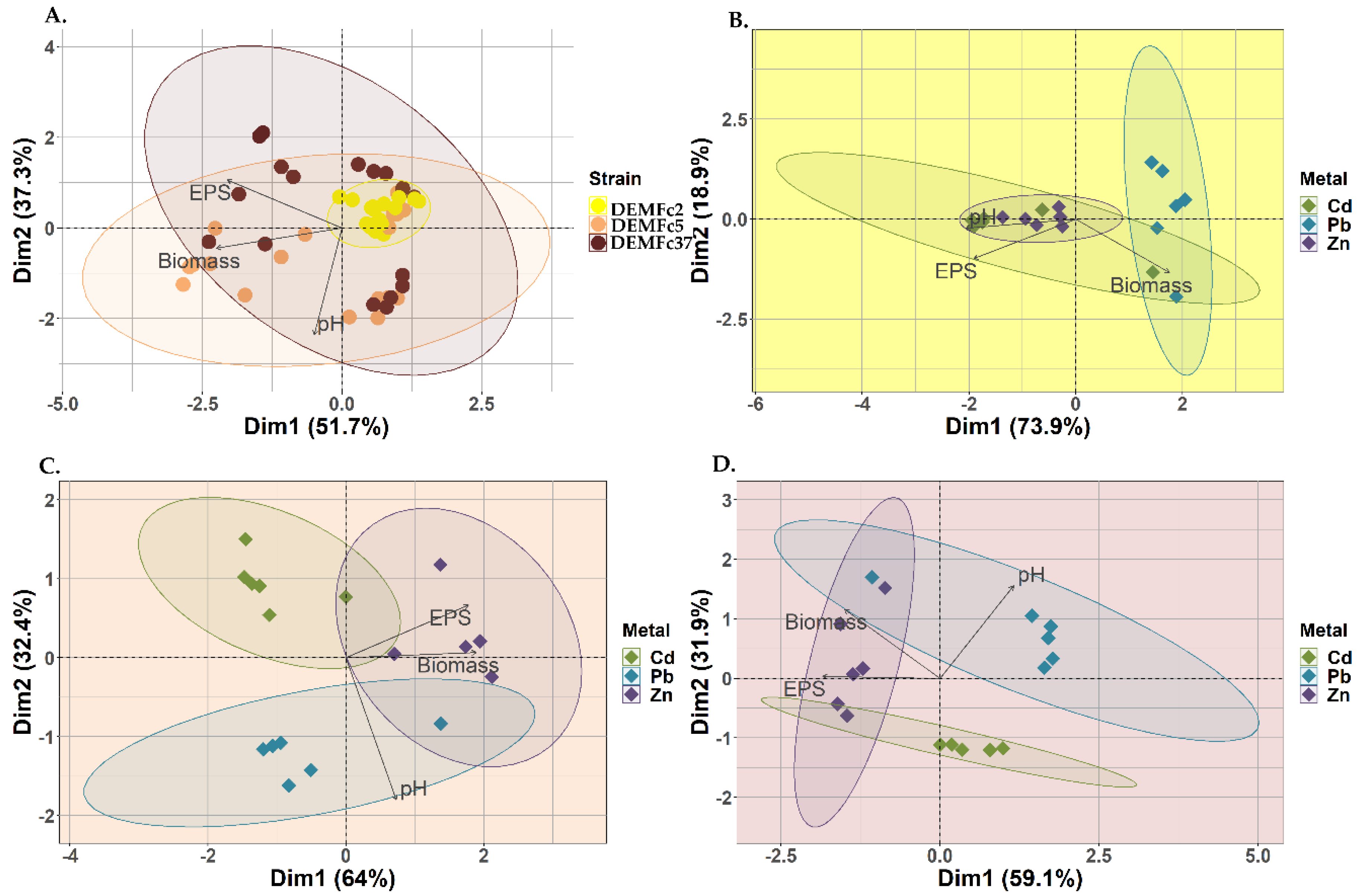

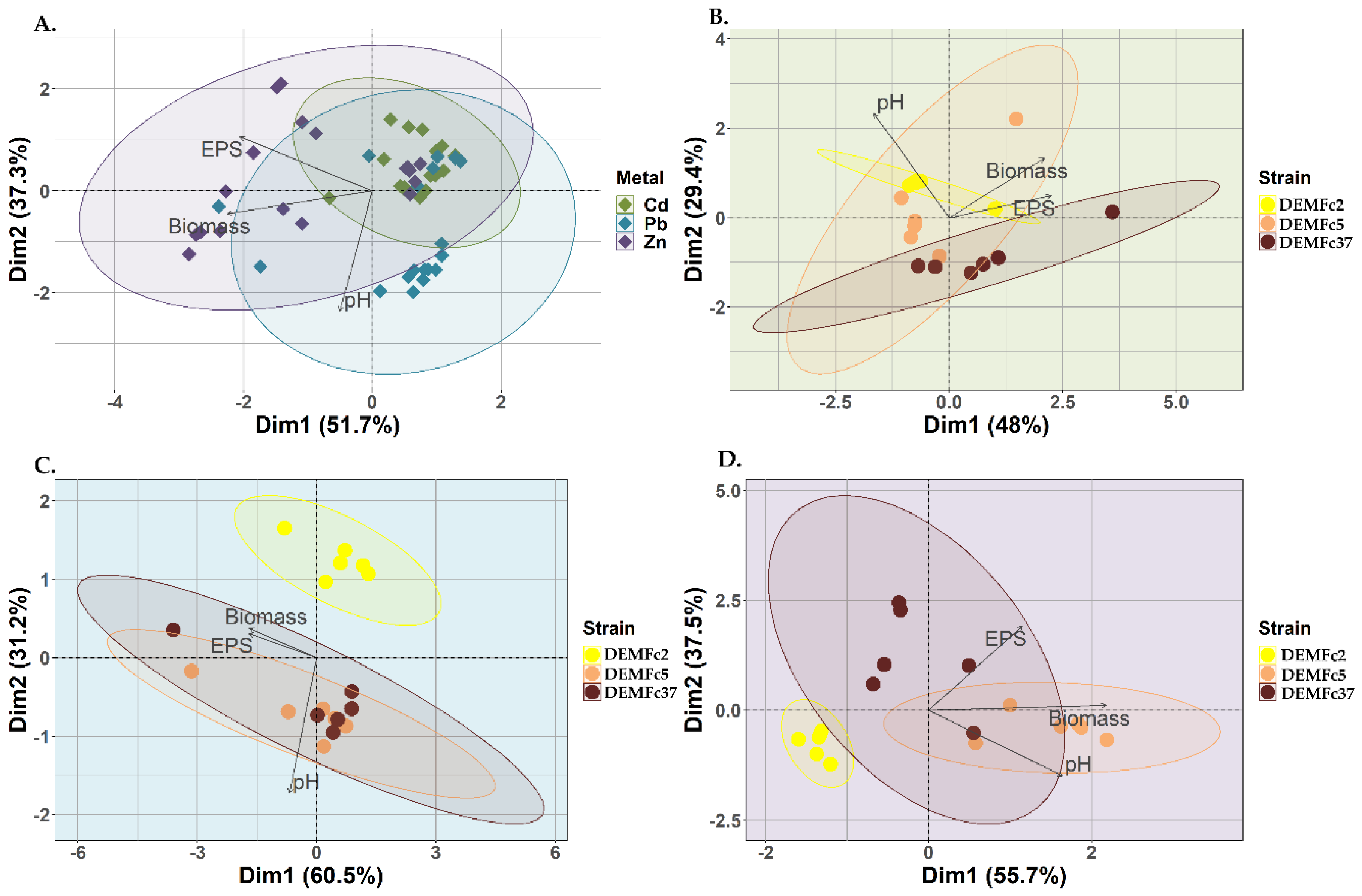

3.2. F. culmorum Strains Growth and EPS Synthesis on a Media Free of Heavy Metals and with the Addition of Heavy Metals

3.2.1. Growth of F. culmorum Strains

3.2.2. EPS Synthesis by F. culmorum Strains

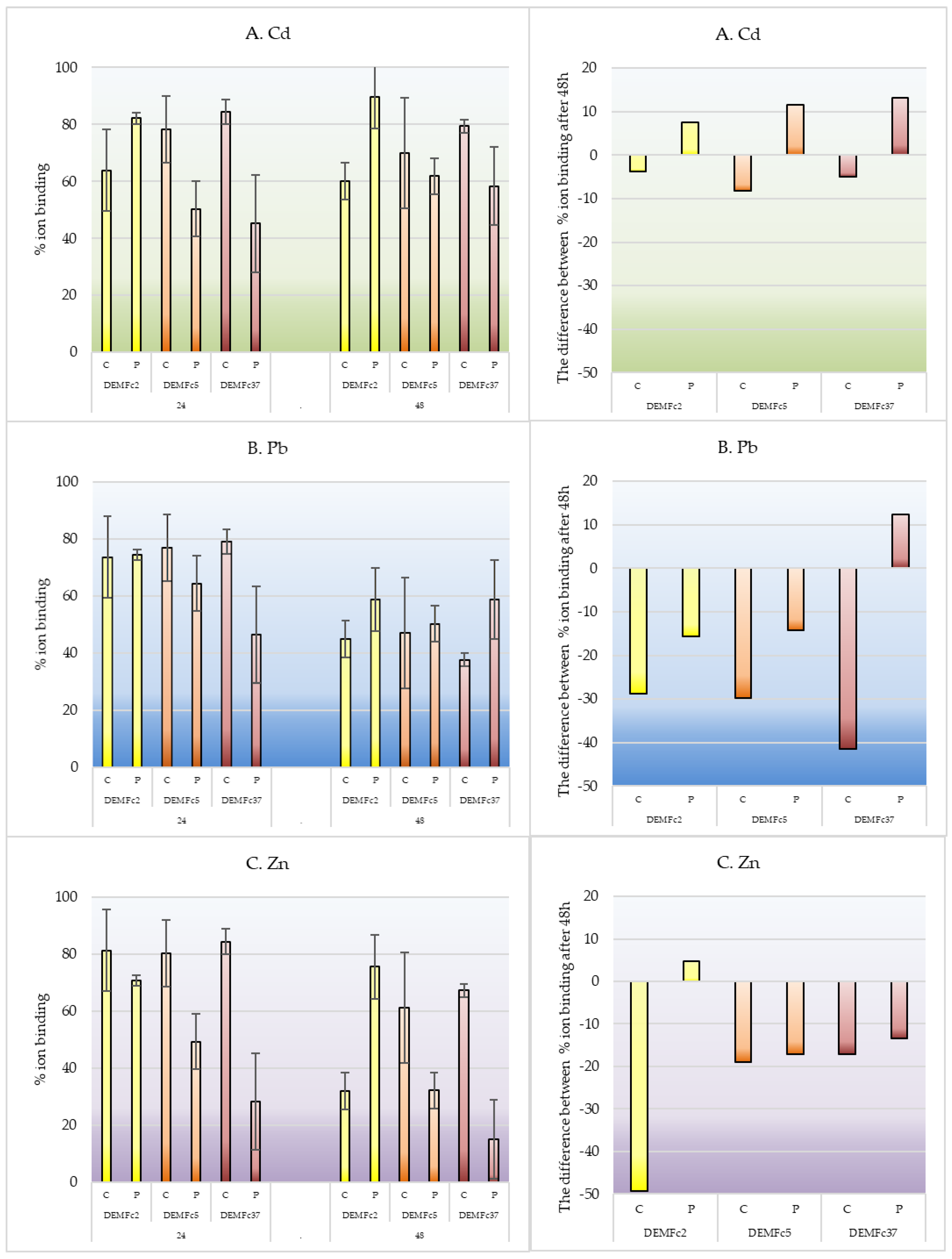

3.3. Binding of Metal Ions – Chelating Properties of F. culmorum EPS

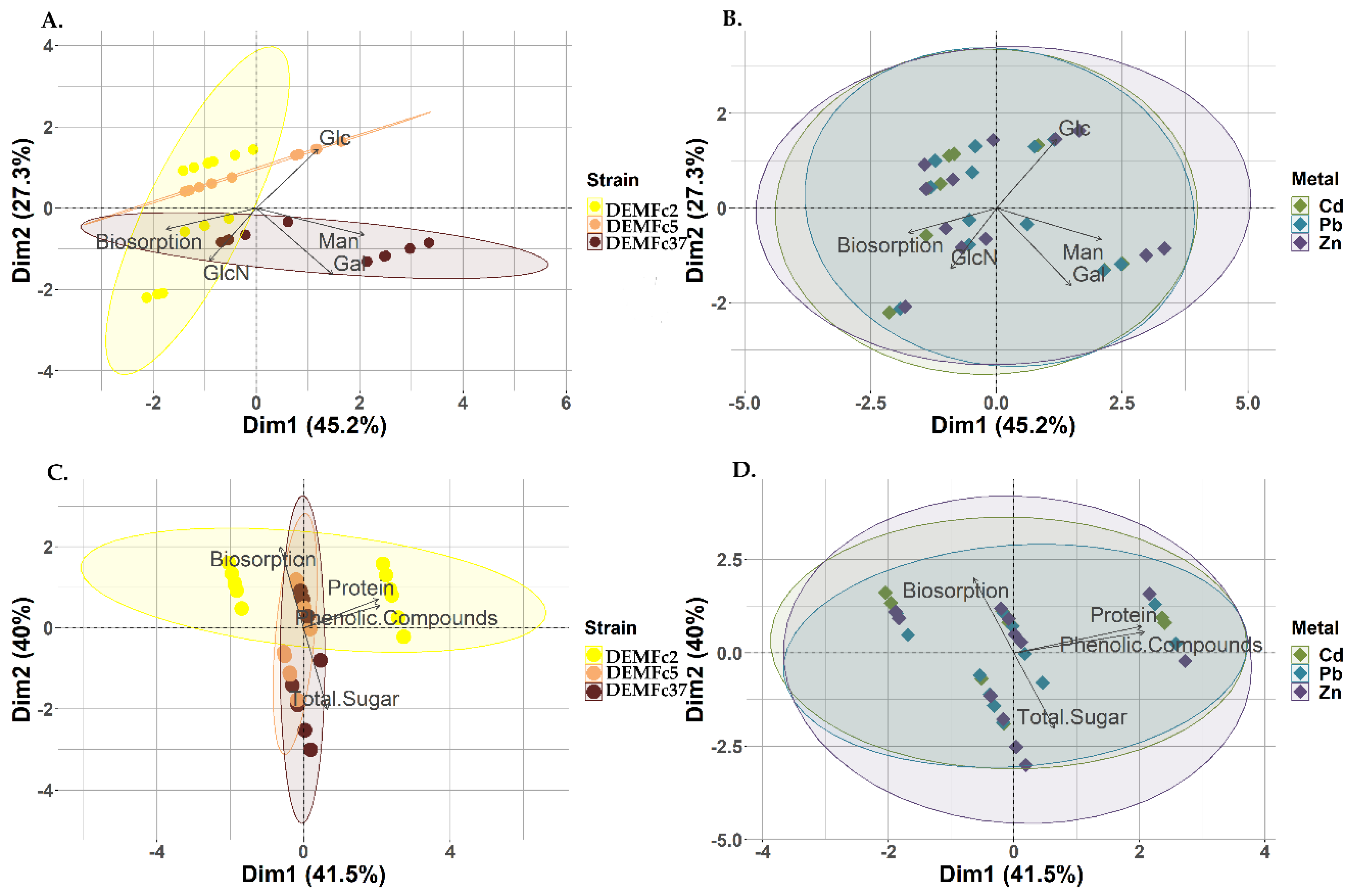

3.4. Relationship Between Metal Biosorption and Type and Composition of EPS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Awasthi, S.; Srivastava, P.; Mishra, P.K. Application of EPS in Agriculture: An Important Natural Resource for Crop Improvement. Agric. Res. Technol. Open Access J. 2017, 8, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, M.C.S.; Vespermann, K.A.C.; Pelissari, F.M.; Molina, G. Current Status of Biotechnological Production and Applications of Microbial Exopolysaccharides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1475–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, O.Y.A.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Kuramae, E.E. Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances: Ecological Function and Impact on Soil Aggregation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, J.; Floryszak-Wieczorek, J.; Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E.; Mattoo, A.; Arasimowicz-Jelonek, M. Fungal and oomycete pathogens and heavy metals: An inglorious couple in the environment. IMA Fungus 2022, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashistha, A.; Chaudhary, A. Effects of Biocontrol Agents And Heavy Metals in Controlling Soil-Borne Phytopathogens. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2019, 7(3), 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.R.; Isikhuemhen, O.S.; Anike, F.N. Fungal–Metal Interactions: A Review of Toxicity and Homeostasis. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre, L.; de Siloniz, M.I.; Valderrema, M.J.; Benito, T.; Larre, M.T.; Peinado, J.M. Occurence of Yeast in Municipal Wastes and Their Behavior in Presence Of Cadmium, Copper And Zinc. J. Basic Microbiol. 2003, 43, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzouhri, L.; Castro, E.; Moya, M.; Espinola, F.; Lairini, K. Heavy Metal Tolerance of Filamentous Fungi Isolated from Polluted Sites in Tangier, Morocco. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2009, 3, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Falandysz, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Saba, M.; Krasinska, G.; Wiejak, A.; Li, T. Evaluation of Mercury Contamination in Fungi Boletus Species from Latosols, Lateritic Red Earths, and Red and Yellow Earths in the Circum-Pacific Mercuriferous Belt of Southwestern China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choma, A.; Nowak, K.; Komaniecka, I.; Waśko, A.; Pleszczyńska, M.; Siwulski, M.; Wiater, A. Chemical Characterization of Alkali-Soluble Polysaccharides Isolated from a Boletus edulis (Bull.) Fruiting Body and Their Potential for Heavy Metal Biosorption. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širić, I.; Humar, M.; Kasap, A.; Kos, I.; Mioč, B.; Pohleven, F. Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation by Wild Edible Saprophytic and Ectomycorrhizal Mushrooms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 18239–18252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, S.D.; Payne, R.J.; Giles, K.R.; Garrill, A. Heavy Metals Have Different Effects on Mycelial Morphology of Achlya bisexualis as Determined by Fractal Geometry. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 201, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osińska-Jaroszuk, M.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Szałapata, K.; Nowak, A.; Jaszek, M.; Ozimek, E.; Majewska, M. Extracellular Polysaccharides from Ascomycota and Basidiomycota: Production Conditions, Biochemical Characteristics, and Biological Properties. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 1823–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fomina, M.; Gadd, G.M. Biosorption: Current Perspectives on Concept, Definition and Application. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volesky, B. Biosorption and me. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4017–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.H.; Ismail, I.M.; Mostafa, T.M.; Sulaymon, A.H. Biosorption of Heavy Metals: A Review. J. Chem. Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, 74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Quan, S.; Li, L.; Lei, G.; Li, S.; Gong, T.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, W. Endophytic Bacteria Improve Bio- and Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, V.; Pandit, S. Advanced Omics Approach and Sustainable Strategies for Heavy Metal Microbial Remediation in Contaminated Environments. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 29, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinakarkumar, Y.; Gnanasekaran, R.; Reddy, G.K.; Vasu, V.; Balamurugan, P.; Murali, G. Fungal Bioremediation: An Overview of the Mechanisms, Applications and Future Perspectives. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 6, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Kutyła, M.; Kaczmarek, J.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Jędryczka, M. Differences in the Production of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) and Other Metabolites of Plenodomus (Leptosphaeria) Infecting Winter Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.). Metabolites 2023, 13, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Kurek, E.; Winiarczyk, K.; Baturo, A.; Łukanowski, A. Colonization of Root Tissues and Protection Against Fusarium Wilt of Rye (Secale cereale) by Nonpathogenic Rhizosphere Strains of Fusarium culmorum. Biol. Control. 2008, 45, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Kurek, E.; Rodzik, B.; Winiarczyk, K. Interactions Between Rye (Secale cereale) Root Border Cells (RBCs) and Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Rhizosphere Strains of Fusarium culmorum. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Nowak, A.; Komaniecka, I.; Choma, A.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Osińska-Jaroszuk, M.; Tyśkiewicz, R.; Wiater, A.; Rogalski, J. Differences in Production, Composition, and Antioxidant Activities of Exopolymeric Substances (EPS) Obtained from Cultures of Endophytic Fusarium culmorum Strains with Different Effects on Cereals. Molecules 2020, 25, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Kurek, E.; Słomka, A.; Janczarek, M.; Rodzik, B. Activities of Cell Wall Degrading Enzymes in Autolyzing Cultures of Three Fusarium culmorum Isolates: Growth-promoting, Deleterious and Pathogenic to Rye (Secale cereale). Mycologia 2011, 103, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Kurek, E. Hydrolysis of Fungal and Plant Cell Walls by Enzymatic Complexes from Cultures of Fusarium Isolates with Different Aggressiveness to Rye (Secale cereale). Arch. Microbiol. 2012, 194, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Kurek, E.; Trytek, M. Efficiency of indoleacetic acid, gibberellic acid and ethylene synthesized in vitro by Fusarium culmorum strains with different effects on cereal growth. Biologia 2014, 69, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, E.; Machowicz, Z.; Kulpa, D.; Slomka, A. The Microorganisms of Rye [Secale cereal L.] Rhizosphere. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 1994, 2, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Czapek, F. Untersuchungen über die Stickstoffgewinnung. Hofmeisters Beiträge Zur Chem. Phys. U. Pathol. Bd. Ii 1902, 1, 559. [Google Scholar]

- Dox, A.W. The Intracellular Enzyms of Penicillium and Aspergillus: With Special Reference to Those of Penicillium camemberti; US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Animal Industry: Washington, DC, USA, 1910; Volume 111.

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.t.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. On tyrosine and tryptophane determinations in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1927, 73, 627–650. [Google Scholar]

- Sawardeker, J.S.; Sloneker, J.H.; Jeanes, A. Quantitative Determination of Monosaccharides as Their Alditol Acetates by Gas Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1965, 37, 1602–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Hakomori, S. A Rapid Permethylation of Glycolipid, and Polysaccharide Catalyzed by Methylsulfinyl Carbanion in Dimethyl Sulfoxide. J. Biochem. 1964, 55, 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, L.J; de Rezende Pinto, F.; do Amaral, L.A.; Gracia-Cruz, C.H. Biosorption of Cadmium (II) and Lead (II) from Aqueous Solution Using Exopolysaccharide And Biomass Produced by Colletotrichum sp. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52(40-42), 7878-7886. [CrossRef]

- Vimalnath, S.; Subramanian, S. Studies on the Biosorption of Pb(II) Ions From Aqueous Solution Using Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 172, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paria, K.; Pyne, S.; Chakraborty, S.K. Optimization of Heavy Metal (Lead) Remedial Activities of Fungi Aspergillus penicillioides (F12) Through Extra Cellular Polymeric Substances. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.H.; Park, C.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, Y. Il Biosorption Isotherms of Pb (II) and Zn (II) on Pestan, an Extracellular Polysaccharide, of Pestalotiopsis sp. KCTC 8637P. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; Hamed, H.A.; Mouafi, F.E.; Gad, A.S. Acidic pH-shock Induces the Production of an Exopolysaccharide by the Fungus Mucor rouxii: Utilization of Beet-Molasses. NY Sci. J. 2012, 5, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Radulović, M.D.; Cvetković, O.G.; Nikolić, S.D.; Dordević, D.S.; Jakovljević, D.M.; Vrvić, M.M. Simultaneous Production of Pullulan and Biosorption of Metals by Aureobasidium pullulans strain CH-1 on Peat Hydrolysate. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 6673–6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.; Stoll, A.; Starke, L.; Duncan, J. Chemical and Enzymatic Extraction of Heavy Metal Binding Polymers from Isolated Cell Walls of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1994, 44, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Wang, Y.J.; Du, H.; Cai, P.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Zhou, D.M. Influence of Bacterial Extracellular Polymeric Substances on the Sorption of Zn on γ-Alumina: A Combination of FTIR and EXAFS Studies. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nell, R.M.; Fein, J.B. Influence of Sulfhydryl Sites on Metal Binding by Bacteria. Geoch. Cosm. Act. 2017, 199, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | DEMFc2 | DEMFc5 | DEMFc37 | |||

| Component | Composition of water fraction of EPS (µg/mL) | |||||

| C | P | C | P | C | P | |

| Protein | 2.3 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.44 | 0 |

| Phenolic compounds | 31.6 | 14.4 | 26.9 | 20.7 | 27.7 | 20.5 |

| Total sugar | 143.7 | 52.4 | 103.9 | 200.8 | 147.1 | 260.2 |

| Strain | DEMFc2 | DEMFc5 | DEMFc37 | |||

| Component | Sugar composition [µg/mg] ±SD* | |||||

| C | P | C | P | C | P | |

| Mannose (Man) | 6.97 (SD=1.670) | 12.40 (SD=0.552) | 29.22 (SD=3.466) | 58.39 (SD=3.828) | 37.39 (SD=4.957) | 128.99 (SD=19.94) |

| Glucose (Glc) | 36.14 (SD=4.230) | 12.69 (SD=1.419) | 18.18 (SD=3.200) | 75.48 (SD=9.038) | 15.18 (SD=3.760) | 34.04 (SD=5.726) |

| Galactose (Gal) | 3.12 (SD=1.290) | 8.01 (SD=0.329) | 2.80 (SD=0.129) | 6.09 (SD=0,531) | 9.41 (SD=1.299) | 13.59 (SD=1.574) |

| Glucosamine (GlcN) | - | 1.09 (SD=0.155) | - | - | - | - |

| Fraction** | Molecular weights [kDa] | |||||

| P | P | P | ||||

| HMW | 1000-735 | - | 1000-735 | |||

| MMW | 15.8 | 73.5 - 34.1 | 18.5 | |||

| LMW | - | 5.4 | ||||

| Type of linkage | Glycosidic bonds [%] | |||||

| P | P | P | ||||

| tHex I (1→(Man)) | 19.5 | 21.13 | 43.56 | |||

| tHex III (1→(Gal)) | - | - | 2.46 | |||

| →2)Hex(1→ | - | 19.81 | 21.32 | |||

| →3)Hex (1→ | 26.81 | 12.67 | - | |||

| →4)Hex(1→ | 22.83 | 35.36 | 4.83 | |||

| →6)Hex (1→ | - | - | 6.38 | |||

| →3,4)Hex(1→ | 14.97 | - | 1.79 | |||

| →3,6)Hex(1→ | 15.89 | 11.03 | 11.46 | |||

| →2,3,4,6)Hex(1→ | - | - | 8.2 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).