1. Introduction

Heavy metal pollution is a growing global problem that poses a significant threat to human and animal health as well as the environment [

1,

2,

3], as they are considered the most dangerous toxins at very low levels. These inorganic pollutants are being dumped into water, soil and atmosphere due to the rapid growth of agriculture, metallurgical industries, mining, improper waste disposal, fertilizers and pesticides [

4]. One of these metals is zinc, classified as a transition metal and considered to be one of the less abundant elements, forming part of the earth’s crust at 0.0005-0.02%. It is classified as very toxic to aquatic organisms and may cause long-term adverse effects to the environment (R50/53) [

5]. Zinc is a common contaminant found in industrial effluents, mining, phosphate fertilizers, zinc plating, landfill leachate, urban stormwater, poultry effluent, compost, waste, and galvanizing [

5,

6]. As such, it poses a significant threat to soil quality, water, plant growth, and human and animal health. [

7].

In soils, zinc is an essential micronutrient for plant growth and development, playing a critical role in photosynthesis, hormone regulation, and nutrient uptake. It is also a mineral necessary for cell stabilization and proliferation with an important role in the defense response against pathogens and pests [

8]. However, excessive levels of zinc in the soil can reduce its fertility by acting as a toxicant to both plants and microorganisms [

9]. This is observed because growth is affected and there is an overall decrease in dry matter along with damage to the leaf and root system [

10]. In addition, plants that accumulate it pose risks to human and animal health due to its bioaccumulative nature and its transfer to the food chain [

11]. The aquatic environment is another common sink for zinc and its compounds contamination, in this case from industrial plants and wastewater treatment plants, resulting in the presence of contaminated sludge on river banks and acidification of surface waters [

5]. Zinc is highly mobile in aquatic ecosystems, including macro- and microorganisms. It tends to accumulate at different levels of the trophic chain, it can modify the bacterial flora and alter the functions of some living organisms, even generating resistance to heavy metals and increasing their bioaccumulation. [

12]. Zinc is an essential metal for human health, but is toxic at high levels, leading to serious health consequences: it can induce cell death, limit the absorption of copper, iron and other essential nutrients, inhibit immune function, and alter high-density lipoprotein levels [

13,

14]. It also affects the nervous system, digestive system, child development, and numerous organs [

15].

On the other hand, zinc is a metal with excellent properties and multiple uses, so its elimination from waste water can be combined with the implementation of technological strategies aimed at its recovery and reuse. The sustainable use of heavy metals is a goal to be achieved. Physicochemical techniques have usually been used to eliminate zinc and other heavy metals, which are effective when the metals are present in high concentrations (>100 mg/L), but lose effectiveness and profitability when the metal ions are very dilute. The biosorption of heavy metals using microbial biomass is very effective in these cases and is also cheap, ecological and in line with current sustainable policies. These microorganisms also have a high potential to be used as catalysts capable of promoting the synthesis of nanomaterials from these metals, which is in line with the circular economy included in these environmental policies. The ability of microorganisms to synthesize ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) has already been demonstrated and these nanomaterials have been shown to have additional properties in numerous technological fields [

16,

17].

The aim of this work was to study the biotechnological potential of

Penicillium sp. 8L2 in the biosorption of Zn(II) from synthetic solutions and in the green synthesis of ZnO-NPs. This is a fungus isolated from urban wastewater that has already shown potential to biosorb other heavy metals and also to promote the synthesis of nanoparticles [

18,

19,

20]. Finally, the aim was to investigate whether these nanoparticles had applications in the field of biomedicine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass Preparation for Testing

A ubiquitous filamentous fungus was selected to evaluate its biotechnological potential in the field of heavy metal biosorption and metal nanoparticle synthesis.

Penicillium sp. 8L2 was isolated from urban wastewater in a previous work [

18]. The fungus was maintained at -80 °C in a glycerol solution and activated in liquid YPG (yeast, peptone, glucose) medium at 27 °C for 48 h, then maintained by periodontal reseeding on solid PDA (potato, dextrose, agar) medium at 5 °C. The fungal biomass for biosorption assays and ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) synthesis was prepared as described in Muñoz et al. 2024 [

20].

2.2. Biosorption tests

Three types of tests were performed: (1) experimental design tests aimed at obtaining the optimal pH and biomass dosage conditions (see section 2.3), (2) kinetic tests aimed at optimizing the contact time, in which a time interval between 0 and 8600 min was studied, and (3) equilibrium tests aimed at obtaining the biosorption isotherms of the Zn(II) biosorption process by Penicillium sp. 8L2 and in which metal concentrations between 20 and 450 mg/L were used. An initial metal concentration of 50 mg/L was used for the kinetic and equilibrium studies.

The biosorption tests were performed by combining the fresh biomass obtained as described in section 2.1 with a zinc sulfate solution (ZnSO

4 · 7H

2O) at different concentrations, prepared in distilled water from a 1 g/L stock solution. All tests were performed in duplicate with the appropriate controls in 100 mL flasks with a working volume of 50 mL. The assay was performed at 27°C and 200 rpm in an SI-600R orbital mixer (Lab Companion Warpsgrove Ln, Chalgrove, Ox-fordshire, UK). Solutions of 0.1 N NaOH and 0.1 M HNO3 were used to adjust the pH of the metal solution for the different test conditions. Before and after the tests, samples were taken and filtered with 0.22 µm PES filters and then measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) in a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 800 instrument (Midland, ON, Canada). Finally, the biosorption capacity (

q) of each biomass was obtained from the results obtained. This parameter was expressed in mg of metal per gram of biomass and was obtained from Equation (1), where

V is the working volume expressed in L, m is the gram of dry biomass used, and

Ci and

Cf are the initial and final metal concentrations (mg/L), respectively.

The experimental results obtained for the kinetic and equilibrium tests were fitted to different mathematical models whose equations and parameters are described in a previous work [

21]. In the case of kinetics, the Ho and Langergreen models were studied, while for equilibrium studies the well-known Freundlich and Langmuir models were chosen.

2.3. Experimental Design

Response surface methodology was applied to a rotatable composite central design, carried out in duplicate, in order to obtain the optimum operating conditions.

Table 1 shows the pH and biomass dose conditions for the experimental design tests. In this table, the replicates appear as independent data. The Design Expert 8.0.7.1 software from Stat-Ease, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to design the experiment and for the final analysis.

2.4. Biosorption Mechanisms Study

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis was used to determine the functional groups present in the initial biomass and their involvement in the Zn(II) biosorption process. For this purpose, samples of the fungal biomass were taken before and after the biosorption step and then washed repeatedly with ultrapure water. The samples were completely dried at 60 °C and, after grinding in a ceramic mortar, analyzed with an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) detector in the range of 400 to 4000 cm-1. A VERTEX 70 (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) was used. The data were analyzed using OPUS 7.0 software, which allowed the identification spectra to be obtained for each case.

Using the same sampling protocol, biomass was collected for analysis by scanning electron microscopy (FESEM-EDX) on a MERLIN instrument from Carl Zeiss (Göttingen, Germany). Samples were prepared as described in a previous paper [

20].

2.5. Nanoparticle Synthesis: Recovery and Identification

To obtain ZnO-NPs, two protocols were designed based on the previous work of other authors [

22] and optimized for this occasion. The two protocols differed only in that in one of them (protocol 2), the cell extract obtained as described in section 2.1 was filtered with 22 µm PVDF filters. In general, the synthesis protocol consisted of 6 steps described below: (1) 125 mL of the cellular extract of

Penicillium sp. 8L2 was treated dropwise with 500 mL of a 0. 1 N Zn(CH

3COO)

2 solution, (2) the mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 1 h, (3) the reaction product was repeatedly washed with ultrapure water in cycles of 5500 rpm/4 min until a concentrate free of residues was obtained, (4) the washed and drained concentrate was stored at 60°C for 48 hours until completely dry, (5) the dry residue was ground in a ceramic mortar and then calcined at 500°C for 2 hours, (6) finally the solid was ground in an agate mortar and stored in a desiccator until use. To characterize the nanoparticles, they were identified by three techniques: (1) UV-vis spectrophotometry using a Shimadzu UV-1800 High Resolution instrument (Römer-strasse 3, Reinach BL, Switzerland), (2) SEM-EDX microscopy, and (3) X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean instrument (Malvern, WR14 1XZ, UK) under the conditions described in Muñoz et al. [

21]. In the first case, the solid obtained was resuspended in ultrapure water and analyzed in the 200 to 700 nm range. In the other two cases, the solid obtained was analyzed directly with the equipment and specifically for the XRD analysis spectra were obtained at a time of 20 min. Finally, from the obtained XRD spectra, the average crystal size was calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation (Equation (2)), where

k is a constant that takes the value of 0.9,

λ is the wavelength of the incident beam (1.5406 Å),

θ is the Braag diffraction angle and

β is the width at half height of the most intense peak. Finally, the actual average size of the nanoparticles was obtained by analyzing the SEM images using ImageJ software (version 1.53e).

2.6. Biocide tests: protocols

For comparative purposes, the biocidal activity of ZnO-NPs was studied against five microorganisms previously studied [

20,

23,

24]: the yeast

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa 1S1 and the bacteria

Bacillus cereus CECT 131,

Staphylococcus epidermidis CECT 4183 (Gram-positive),

Escherichia coli CECT 101 and

Pseudomonas fluorescens CECT 378 (Gram-negative). Two types of biocidal tests were performed: (1) on solid Müller-Hinton medium contaminated with increasing concentrations of nanoparticles, and (2) on liquid medium in 96-well plates containing a 10% dispersant (polyvinyl alcohol, PVA). The procedures are described in detail in Muñoz et al. [

20]. All assays included positive and negative controls, were performed in triplicate, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined. In the second protocol, results were obtained by analyzing the growth curve at 24 h by reading the absorbance at 630 nm every 30 min in two spectrophotometric devices: BioTek Synergy HT (Santa Clara, USA) and TECAN Infinite M Plex (Männedorf, Switzerland).

3. Results and Discussion

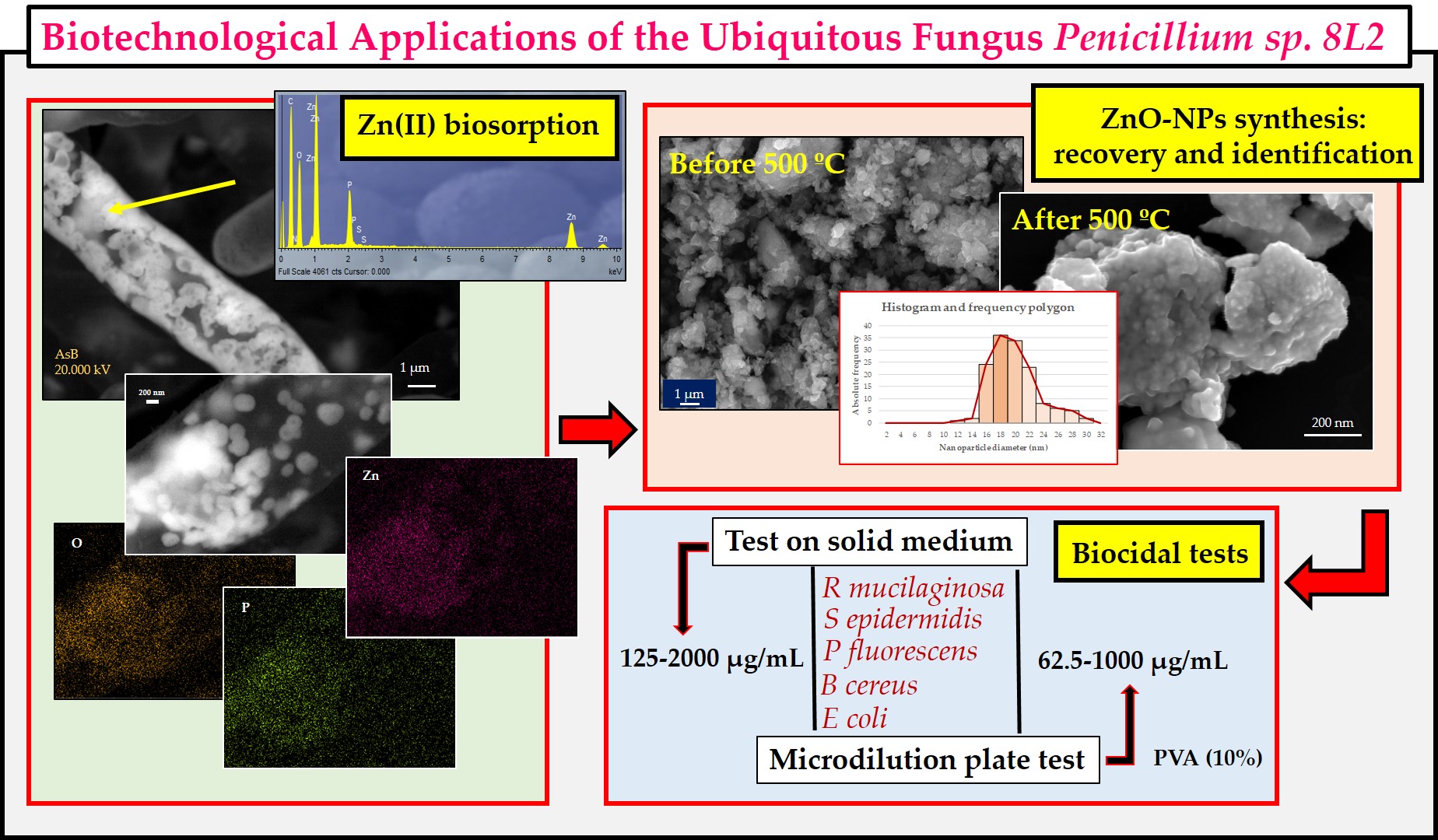

3.1. Optimal Operating Conditions for Zn(II) Biosorption

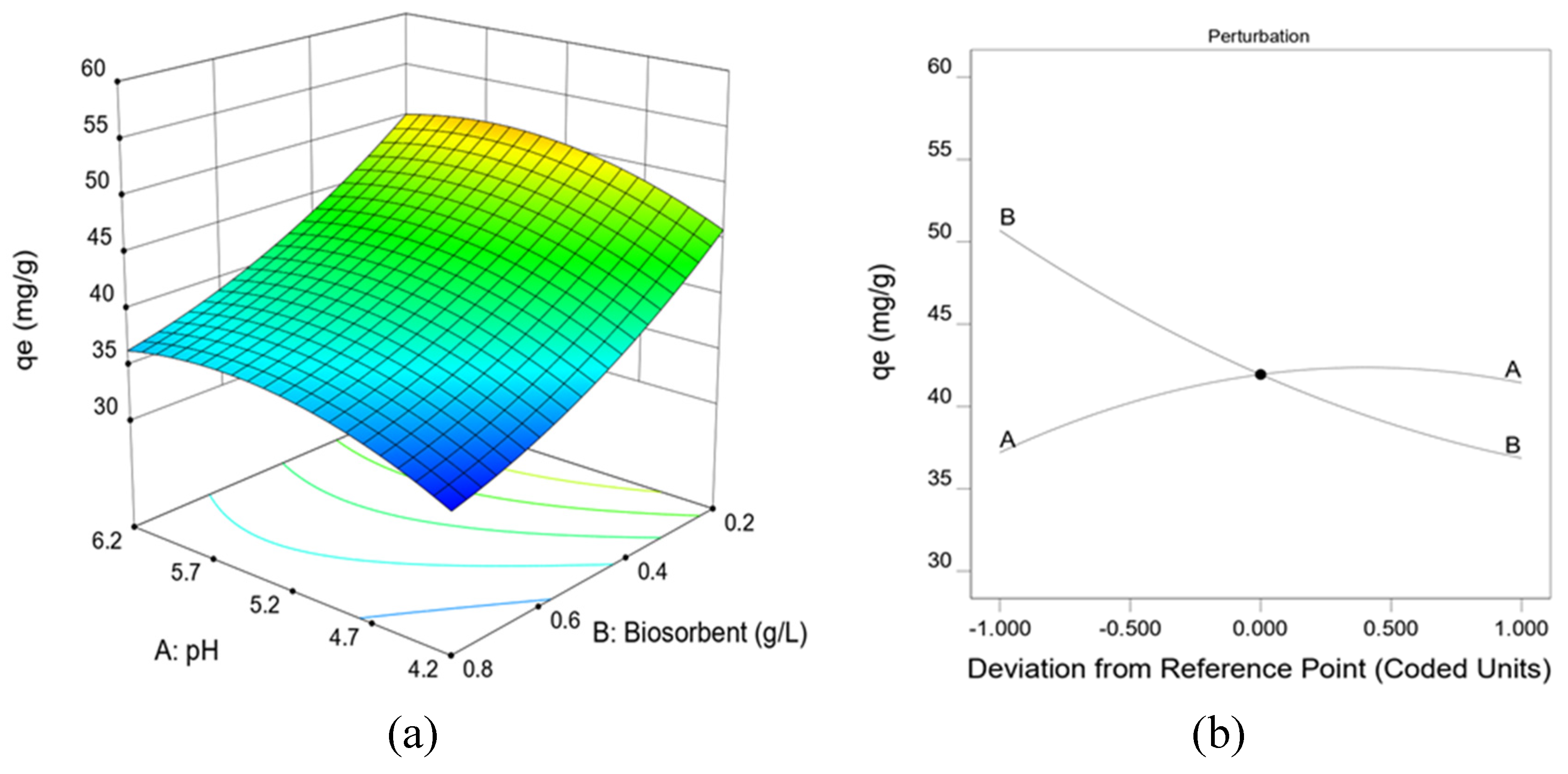

Table 1 shows the results obtained in the experimental design tests for the biosorption of Zn(II) by Penicillium sp. 8L2. Good biosorption values between 32.04 and 55.55 mg/g were obtained. The experimental data were fitted to a quadratic model represented by Equation (3) in coded factors. When the values of pH (A) and biomass dose (B) were optimized with this equation, the following optimal operating conditions were obtained: 0.2 g/L biomass dose and a pH of 5.6.

The model fit the experimental data well and presented a coefficient of determination (R

2) of 0.95 and a standard deviation of 1.68 mg/g. At the same time,

Figure 1a shows the response surface obtained from Equation (3) for the factors studied. This figure shows the biosorption capacity obtained for each combination of the two factors and, as can be seen, the best response was obtained for a pH value (A) of 5.6 and a biomass dose (B) of 0.2 g/L. In parallel,

Figure 1b shows the perturbation diagram obtained from the coded values of both factors, and in it a significant negative influence of the biomass dose is observed, while the pH shows a slight positive influence until it stabilizes.

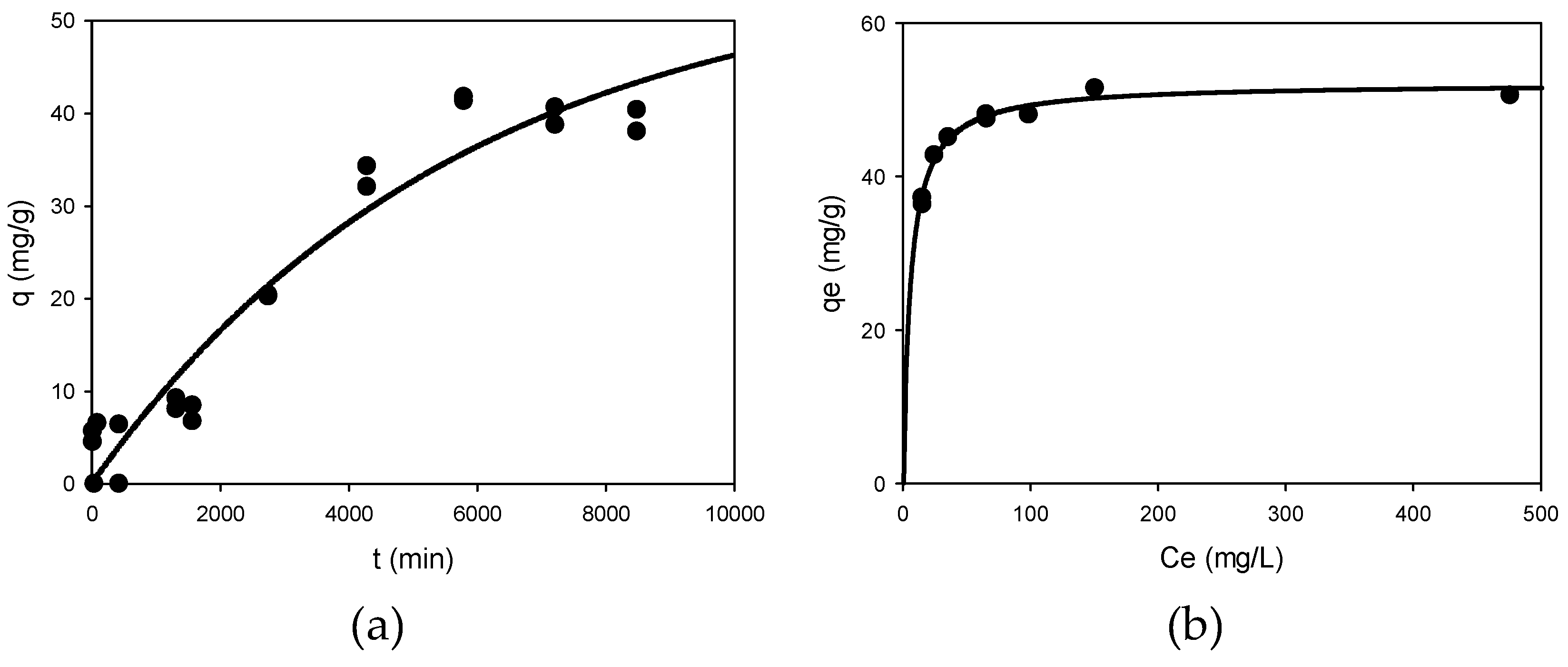

3.2. Kinetic and Equilibrium Tests

Figure 2a shows the curve obtained by fitting the experimental data obtained in the kinetic test described in section 2.2 to the Lagergren model. In this case, the two kinetic models studied fit the experimental data well, but the Lagergren or pseudo first order model fitted them better with an

R2 value of 0.93, a standard deviation of 4.29 mg/g and a p-value for the variable

qe less than 0.0001 and 0.0037 for the constant

k. The pseudo-first order model assumes that adsorption is controlled by the mass transfer of metal ions to the surface of the adsorbent, whereas in the pseudo-second order model, the adsorption phase would be controlled by the presence of chemisorption phenomena. In the case of Zn(II) biosorption by

Penicillium sp. 8L2, the data seem to indicate that physisorption and chemisorption phenomena can coexist. The kinetic curve allows the identification of two phases in the Zn(II) biosorption process: (1) a rapid phase that occurs in the first few minutes and lasts about 24 hours, and (2) a slower phase that lasts almost four days.

Figure 2b shows the isotherm of the Langmuir model after fitting the experimental data obtained in the equilibrium test. This model showed a good fit with an adjusted

R2 of 0.98, a standard deviation of 0.92 mg/g and p-values below 0.0001 for the values of

qm and

b (equilibrium constant). The model predicted a theoretical value of

qm of 52.14 mg/g, which is very close to the experimental value. Although the Langmuir model assumes a predominance of monolayer adsorption, the fitting of the data to the Freundlich model, with an adjusted

R2 of 0.80, a standard deviation of 2.69 mg/g and significant statistical parameters, indicates that the microorganism involves different mechanisms, which will be discussed in section 3.3. In general, the maximum equilibrium Zn(II) biosorption capacity of

Penicillium sp. 8L2 was higher than that reported by other authors.

Table 2 shows the values obtained in different previous studies. As can be seen, except for the values obtained by Fan et al. with a filamentous fungus of the same genus [

25], all others are much lower than those found in this work. Saravanan et al. found similar values, but worked with modified plant biomass in combination with

Aspergillus tamarii [

26].

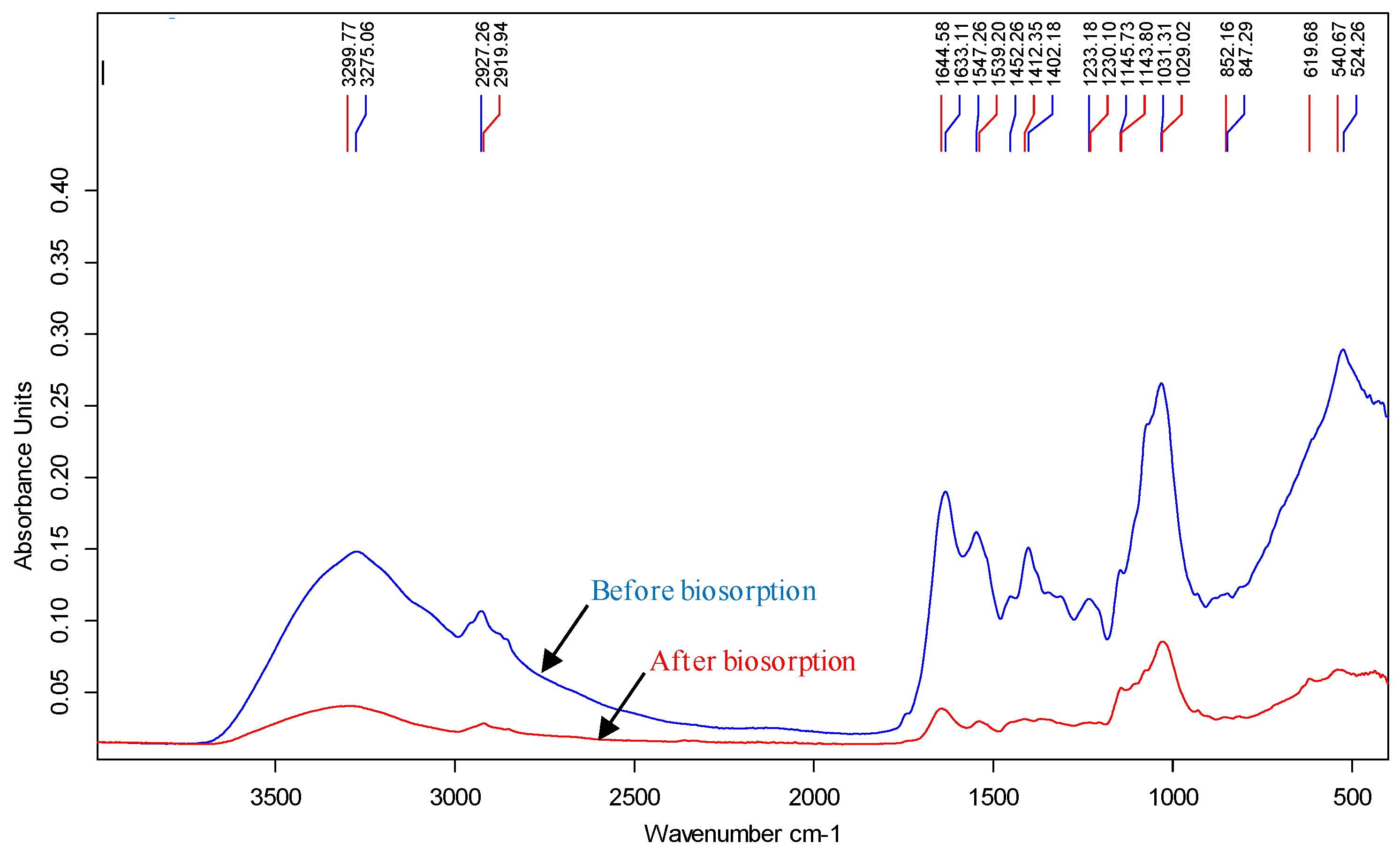

3.3. Biosorption Mechanisms

Figure 3 shows the spectra obtained from the samples of Penicillium sp. 8L2 biomass collected before and after their contact with the Zn(II) solutions. The first thing that can be observed is a notable loss of intensity in the signal, indicating a generalized involvement of the functional groups present in the biomass. Important shifts in the representative bands of the different functional groups were also observed. The band located at 3275 cm

-1 shifted to 3300 cm

-1, which identified the presence of stretching vibrations of amino (N-H) and hydroxyl (O-H) groups. In this region, the characteristic band of methylene groups (-CH

2) located at 2927 cm

-1 shifted to 2920 cm

-1. The amide I and amide II regions were also affected with strong shifts of the 1633 cm

-1 and 1644 cm

-1 bands to 1644 cm

-1 and 1539 cm

-1, respectively [

2,

31]. The changes in the amide bands indicate the involvement of C=O bond stretching (amide I), N-H bond twisting and C-N bond stretching (amide II). In parallel, a strong change was observed in the region between 1500 and 1400 cm

-1: the bands originally located at 1452 and 1402 cm

-1 shifted to 1412 cm

-1 after Zn(II) biosorption, confirming the involvement of methylene groups (-CH

2) [

32]. The involvement of carbonyl groups is also confirmed by the strong loss of intensity of the band at 1233 cm

-1, which also suffers a slight shift to 1230 cm

-1. This band is usually assigned to stretching vibrations of C-O bonds of carbohydrates and alcohols, but also to stretching of phosphorus bonds, which could indicate the additional involvement of phosphate groups (POO-). Something similar happens with the band at 1031 cm

-1, which suffers a strong loss of intensity and is also related to stretching of C-O bonds [

33]. In conclusion, the biomass of Penicillium sp. 8L2 contains amino, carbonyl, hydroxyl, methylene and possibly phosphate groups involved in the retention of Zn(II) ions.

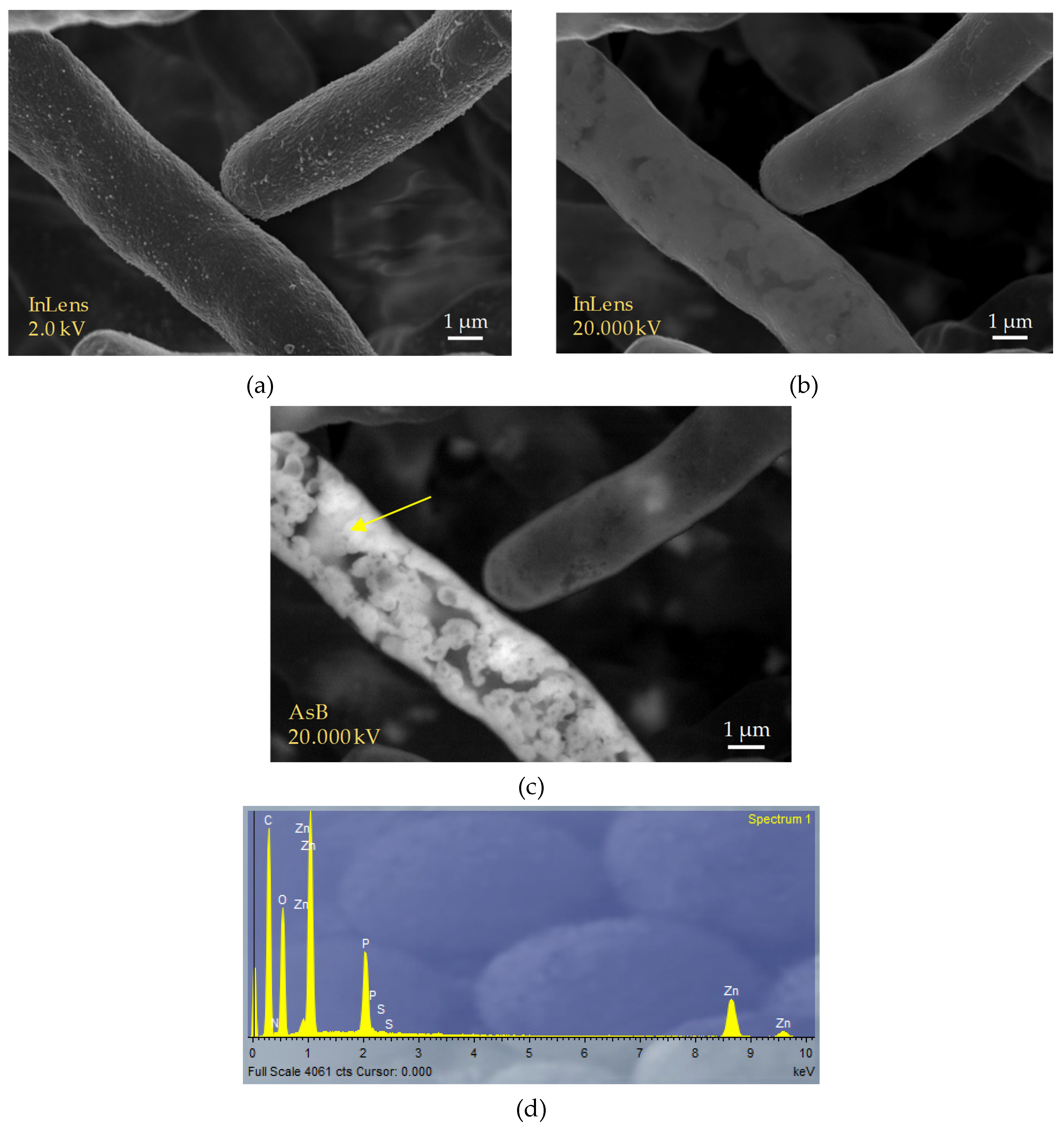

Figure 4 shows the images of the biomass of Penicillium sp. 8L2 obtained after the Zn(II) biosorption step. The image a shows the characteristic hyphae of the fungus taken with the secondary electron lens detector (InLens) at low kilovoltage. As the kilovoltage increased (

Figure 4b), it was observed that the retained metal was mostly located in a subsurface space of the fungal hyphae. To confirm this, the AsB backscattered electron detector was switched on and this allowed us to clearly identify that the location of the zinc precipitates seemed to be mainly between the membrane and the cell wall of the hyphae (

Figure 4c). EDX spectra show that zinc, although dispersed throughout the hypha, is concentrated in well-defined precipitates. In addition, intense phosphorus peaks are observed, indicating that this element is involved in the formation of these precipitates. The results of this SEM analysis are compatible with those observed in the kinetic tests, where two different phases were observed in the biosorption of Zn(II) by Penicillium sp. 8L2. The first, very fast, would be the surface biosorption dominated by physical mechanisms and would explain the homogeneous distribution of zinc on the cell surface, while the second, slower and sustained over time, would imply a bioaccumulation process that motivated the formation of zinc phosphate precipitates and possibly ZnO nanoparticles. This hypothesis would also be supported because the kinetic data fit better to a pseudo-second-order model in which the process is dominated by chemical adsorption [

34]. A recent meta-analysis of 56 previous studies evaluated the response of different suspended bacterial strains to various metals, including zinc, and found differences in biosorption efficiency depending on whether these metals were non-essential or essential. It was observed that non-essential metals required short contact times of only 2 h, while essential metals, including Cu(II) or Zn(II), required long contact times (24 h on average) to optimize the process [

35]. It is possible that the micronutrient nature of both metals prevents microbial cells from initially recognizing the risk of toxicity, and this leads them to act in a natural way aimed at incorporating these ions into the cytoplasm and then triggering metal elimination mechanisms that could involve precipitation phenomena such as those observed in the SEM images.

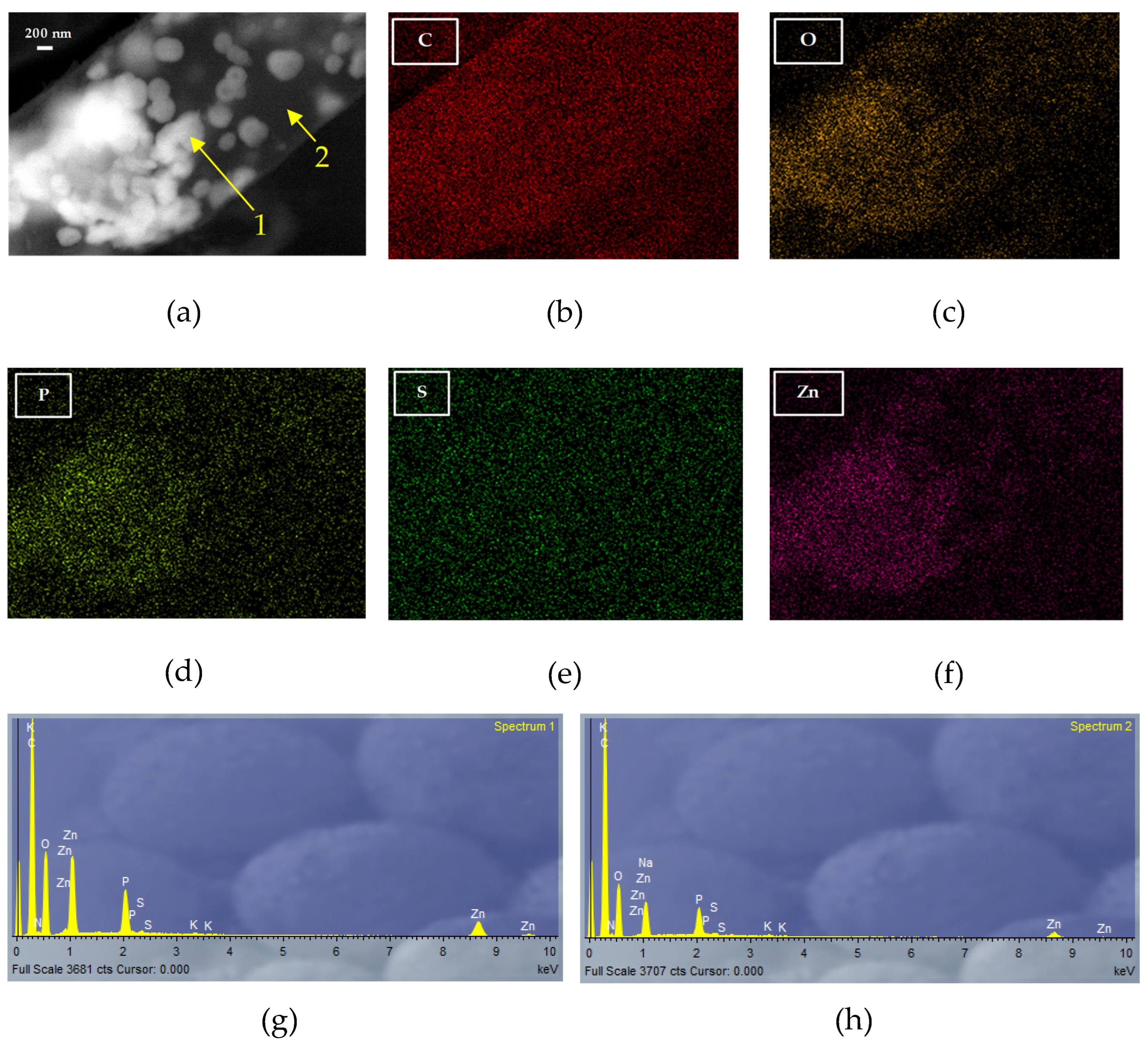

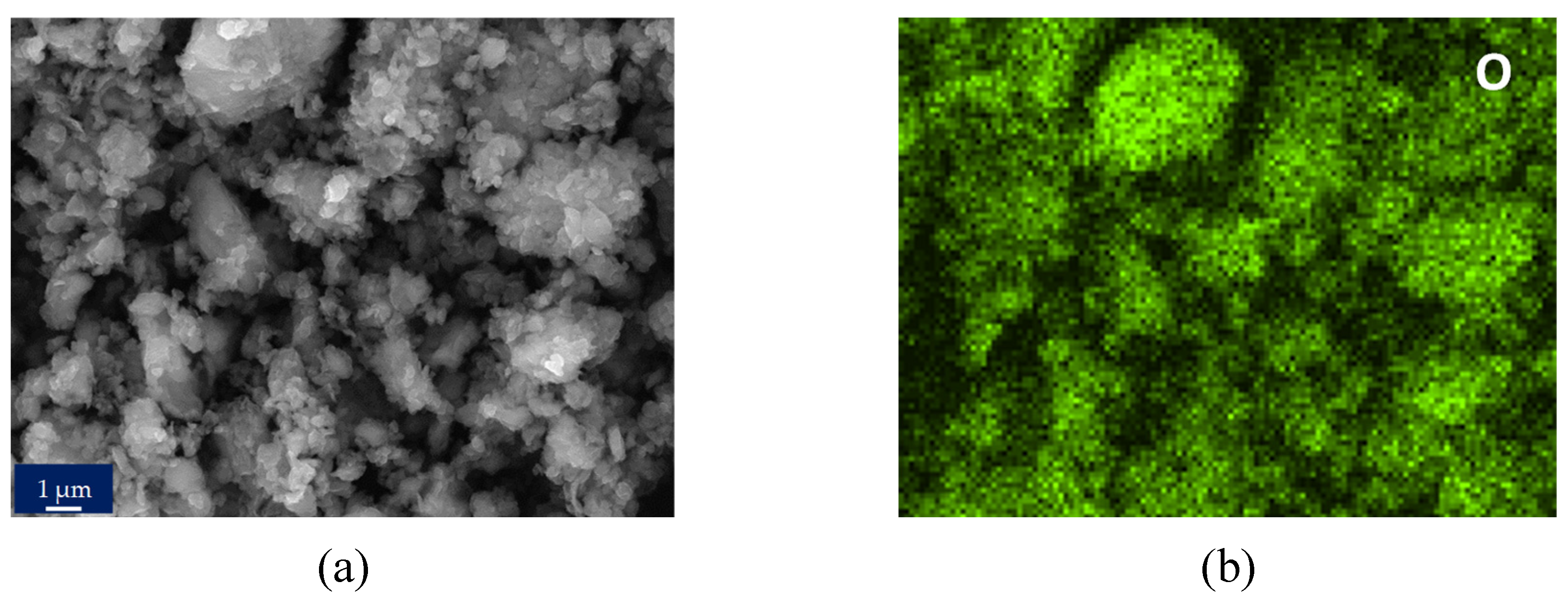

To gain a deeper understanding of the morphology and composition of the precipitates, elemental mappings were performed on some specific regions.

Figure 5 shows one of them, where these precipitates are perfectly identified (

Figure 5a). EDX spectra 1 and 2 (

Figure 5g and 5h, respectively), taken at the location indicated by the arrows, show that the metal is concentrated in nanometric aggregates of spherical shape. The different elemental maps clearly show that O and P are involved in the formation of these precipitates, which is consistent with what was shown in the FT-IR analysis, indicating that the hydroxyl and phosphate groups are involved in the biosorption of Zn(II) by Penicillium sp. 8L2. Spectra 1 and 2 are also consistent with this evidence, showing that where there is more zinc, there is also more phosphorus. In parallel, the active participation of oxygen also shows that the precipitates could contain aggregates of ZnO nanoparticles.

3.4. Characterization of Nanoparticles

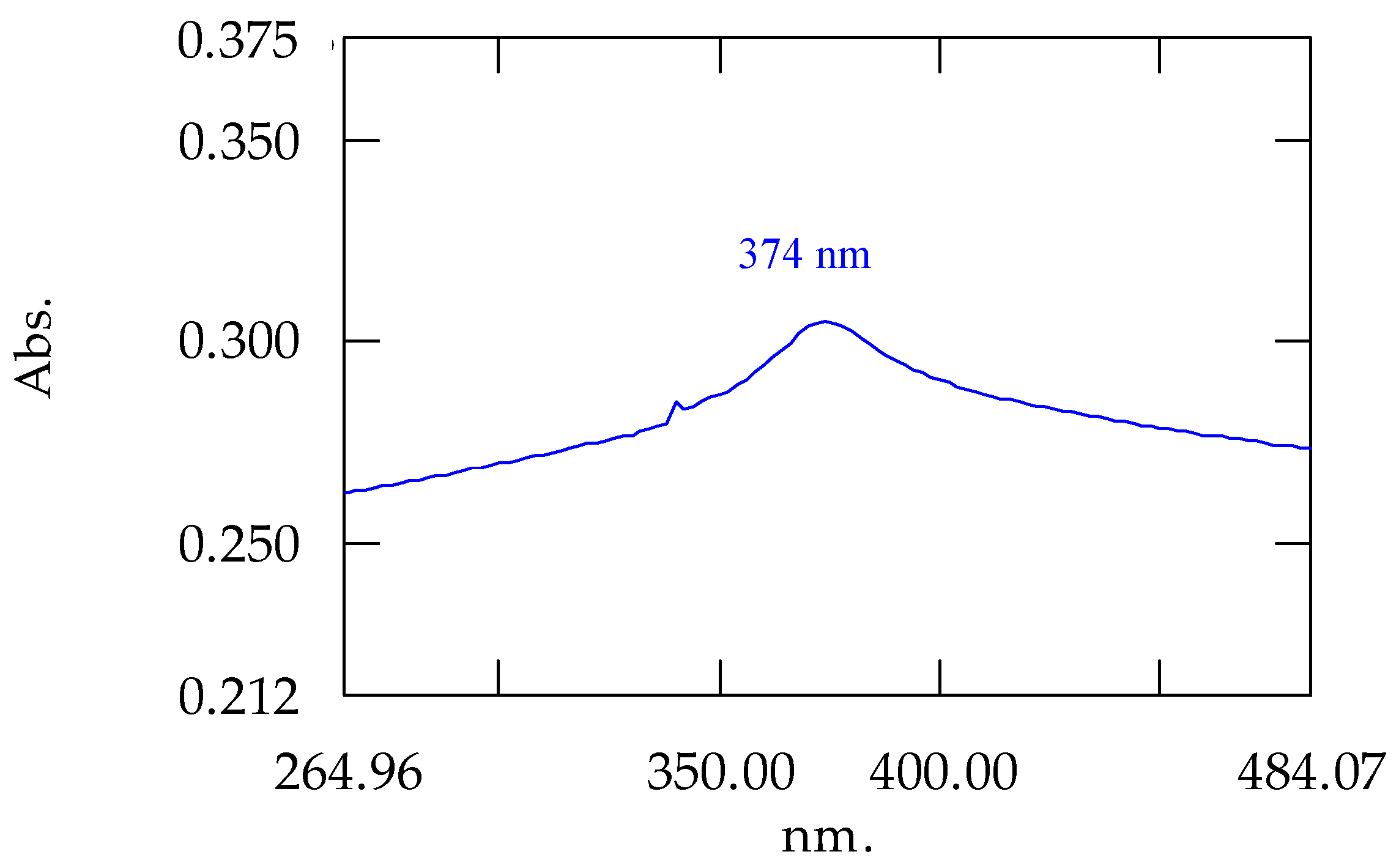

The first confirmation of the formation of ZnO-NPs was obtained during the synthesis stage itself, where a fraction of the solid obtained was resuspended in ultrapure water and analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Figure 6 shows the spectrum obtained, where a peak at 374 nm is observed. Other authors have synthesized ZnO-NPs and identified the characteristic peak of these nanoparticles in this region of the spectrum. Assefa et al. recently performed a detailed study of this type of nanoparticles obtained from a plant extract and found that pure ZnO-NPs exhibited a characteristic peak at 380 nm [

36]. Similar data were obtained by Ma et al. with nanoparticles obtained from different plant extracts with peaks between 370 and 373 nm [

37].

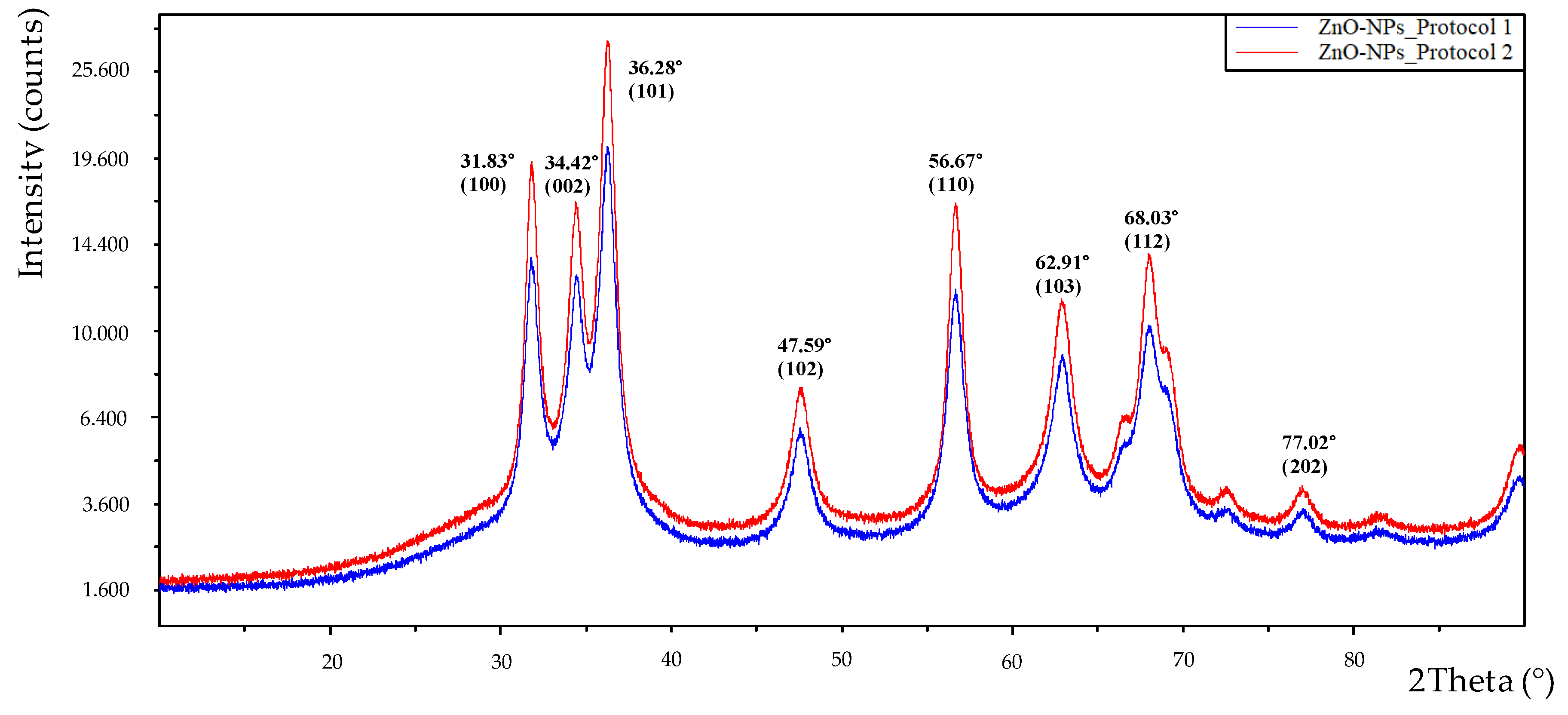

The solid obtained at the synthesis stage was also subjected to XRD analysis and

Figure 7 shows the spectra obtained with the material resulting from the two synthesis protocols. Both spectra show identical peaks, only varying in intensity. In both cases, the bands are perfectly related to what was expected and confirm that they are ZnO-NPs, although in protocol 2 (red color) more intense peaks were obtained, indicating a higher purity and crystallinity of the nanoparticles. The positions for the 2Theta angle and their respective Miller indices were as follows: 31.83° (100), 34.42° (002), 36.28° (101), 47.59° (102), 56.67° (110), 62.91° (103), 68.03° (112), 77.02° (202). These data are consistent with those obtained by other authors and confirm the success of the synthesis and the high purity of the nanoparticles obtained [

36,

38]. When the most intense peak was analyzed using the Debye-Scherrer equation, an average crystal size of 9.14 nm was obtained, which is slightly smaller than that obtained by SEM analysis. The

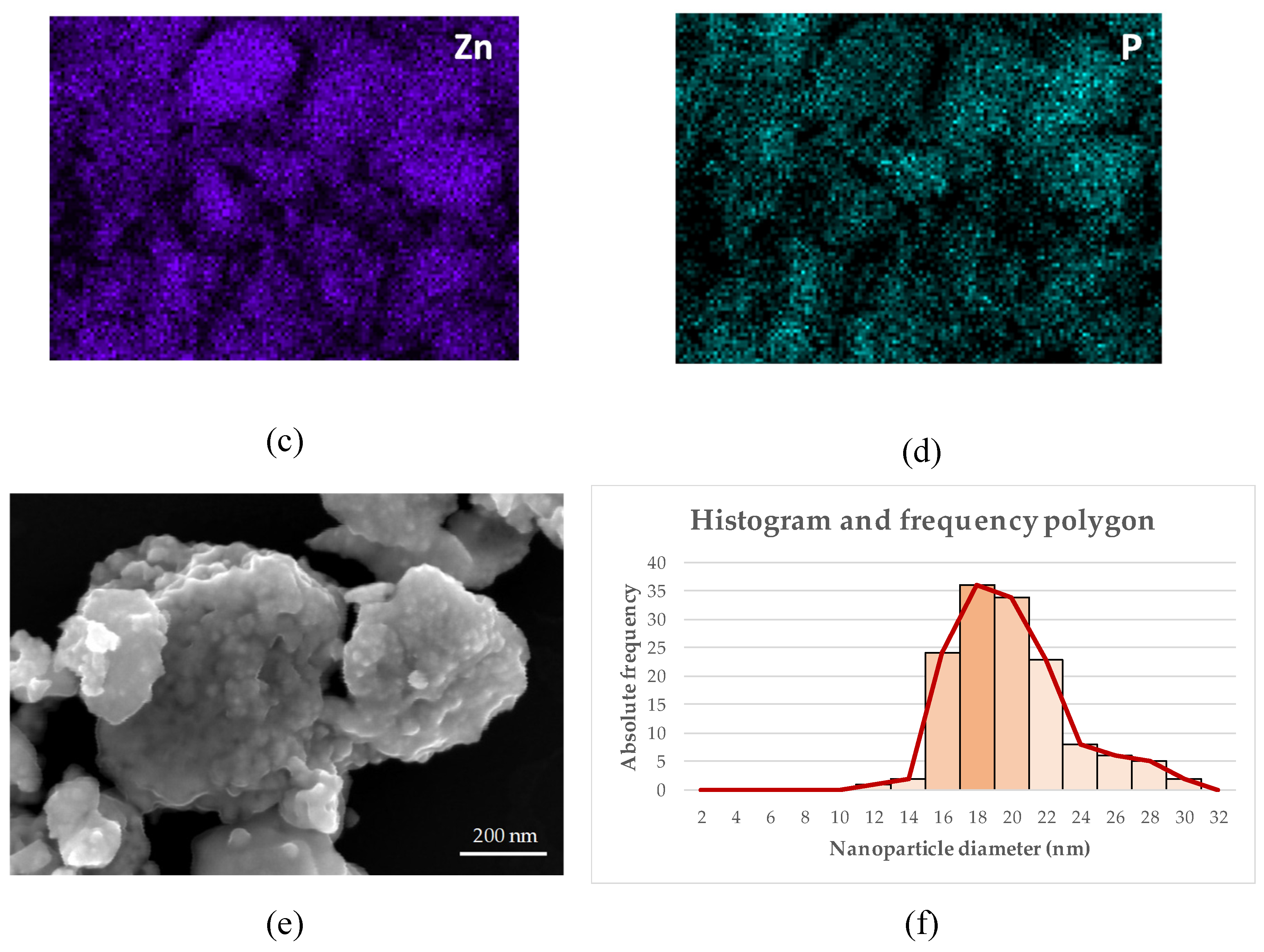

Figure 8 shows the images of the nanoparticles obtained before and after calcining at 500 °C. The

Figure 8a corresponds to the nanoparticles obtained in protocol 1 (unfiltered extract) before passing through the calcination stage. The image already shows a significant presence of nanoparticles, but very heterogeneous in size and shape. A strong presence of aggregates is also observed. The elemental map shown in the image b, c and d confirms the participation of oxygen, phosphorus and zinc in their formation. The same elements also appear in the pure nanoparticles that have undergone the calcination stage. In parallel, the

Figure 8e image shows the appearance of the nanoparticles obtained in protocol 2 (filtered extract) after the calcination step at 500 °C, in which small nanoparticles with very homogeneous spherical shapes can be observed.

The XRD spectra, images and elemental maps allow us to affirm that the nanoparticles obtained by protocol 2 have better morphological characteristics and for this reason they were selected to perform the subsequent biocidal tests (see section 3.5). In this context, the SEM-NP-e image was chosen to perform the analysis of the average particle size using the ImageJ software. Likewise, the

Figure 8f image shows the histogram and the frequency polygon that identifies an average crystal size of 18 nm. The observed difference between the theoretical and real size is within the expected range, taking into account the tendency of the obtained ZnO-NPs to aggregate. For this reason, two types of biocidal tests were carried out, in the second of which a dispersing agent was added, as described in the following section. Abdelsattar et al. found slightly larger sizes (20-25 nm) for ZnO-NPs obtained from Origanum majorana extract, with mostly spherical sizes [

39]. On the other hand, Ma et al. found similar sizes between 10 and 20 nm with nanoparticles obtained from different plant extracts [

37]. Dejene carried out extensive work on the different types of ZnO-NPs synthesized using different extracts of bacteria, fungi, algae and plants as precursors. This author found that in most cases the sizes were larger than those reported in this research. He also found that spherical shapes predominated over the rest and that changes in the precursors of the synthesis reaction affected the final result [

40]. This statement is consistent with the results of this research since, as mentioned above, it was observed that the filtering of the initial extract significantly affected the purity, crystallinity, morphology and size of the final nanoparticles. This fact indicates that small changes, which do not involve excessive additional costs, can lead to significant improvements in the nanoparticles obtained.

A final relevant fact is the presence of phosphorus in the elemental maps (

Figure 8d image) and in the EDX spectra (not shown) obtained from the ZnO-NPs. The data show that there is a residual fraction of this element involved in the synthesis of the nanoparticles, which is not reflected in the XRD spectra. As explained, these spectra show the characteristic peaks of pure ZnO-NPs. In the analysis of the mechanisms (section 3.3), the involvement of phosphate groups in the retention of Zn(II) was demonstrated, and everything indicates that they are also involved in the formation and consolidation of the nanoparticles. This is a very little studied phenomenon, but some authors have proposed biomeralization models to explain it. He et al. Working with yeast, they identified a chemical precipitation mechanism in aqueous medium that gives rise to zinc phosphate nanoparticles that aggregate to form mesoporous aggregates with a high specific surface area [

41]. In this case, the authors added Na

3PO

4 to the synthesis reaction and this conditioned the final result, in which the XRD spectra differ significantly from the characteristic spectra of ZnO-NPs, although they show some coinciding peaks. It is possible that cellular phosphorus plays a relevant role in the molecular structure of ZnO-NPs obtained from cell extracts, which should be studied in the future.

3.5. Biocidal Tests

Table MIC shows the results obtained in the biocidal tests performed with the ZnO-NPs synthesized in this work. The preliminary tests carried out on four bacteria yielded MIC values between 125 and 2000 µg/ml. Subsequently, the addition of 10% PVA resulted in a significant improvement of the biocidal response with values between 62.5 and 1000 µg/mL. The most sensitive microorganisms were the Gram-positive bacterium S. epidermidis, the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli and the yeast R. mucilaginosa, in all three cases with an MIC between 62.5 and 125 µg/mL. On the other hand, the Gram-negative bacterium P. fluorescens showed a higher resistance with a MIC between 500 and 1000 µg/mL. ZnO-NPs are known to exhibit several potential mechanisms of biocidal action, such as the release of Zn(II) ions or the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

42]. There are not many studies that directly determine the MIC of biologically synthesized ZnO-NPs, most studies use the disk diffusion technique on plates, which does not allow direct reading of this parameter. Kamaraj et al. tested two types of nanoparticles synthesized from fruit extracts against different microorganisms such as the bacteria S. aureus, S. typhi, B. cereus, S. mutans, P. aeruginosa and E. coli or the yeast Candida albicans. The results showed that at a concentration of 100 µg/mL, inhibition zones between 10 and 18 mm were obtained, indicating that the microorganisms were sensitive to the nanoparticles [

43]. Another study determined the MIC of green chemistry-derived ZnO-NPs against Bacillus cereus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Salmonella typhi and Shigella sp. and found a value of 100 µg/mL against the first two strains and 200 µg/mL for the rest [

44]. Similar values were found by Marques et al. against a battery of collection microorganisms: Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC35984, S. aureus ATCC25923, S. aureus ATCC8095, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212, Enterococcus faecium ATCC700221, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC700603, Escherichia coli ATCC25922, Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853, with values ranging from 256 to 512 μg/mL [

45]. The above confirms that the biocidal capacity of ZnO-NPs is in similar or better ranges than those obtained by other authors and reinforces the importance of continuing to study the medical applications of this type of nanoparticles in a context of increasing resistance to antibiotics by pathogenic microorganisms.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values expressed in μg/mL for the different microorganisms tested. Data obtained for ZnO-NPs in the absence and presence of PVA (10%) are shown.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values expressed in μg/mL for the different microorganisms tested. Data obtained for ZnO-NPs in the absence and presence of PVA (10%) are shown.

| Bacteria |

ZnO-NPs |

ZnO-NPs + PVA(10%) * |

| B cereus |

1000-2000 |

250-500 |

| S epidermidis |

125-250 |

62.5-125 |

| E coli |

250-500 |

62.5-125 |

| P fluorescens |

1000-2000 |

500-1000 |

| R mucilaginosa 1S1 |

- |

62.5-125 |

| * PVA: polyvinyl alcohol |

4. Conclusions

Penicillium sp. 8L2 showed good potential for biotechnological application in the field of heavy metal removal from contaminated wastewater, and also offered good potential for use in the green synthesis of ZnO-NPs. The results obtained in this work showed that the ubiquitous microorganism had a good biosorption capacity for Zn(II) (qm=52.14 mg/g) under the optimal conditions obtained by the experimental design. The novel methodology used in the FESEM-EDX analysis made it possible to identify the metal retained at the subsurface level without resorting to TEM analysis. The synthesized nanoparticles presented spherical shapes and an average size of 18 nm and exhibited high biocidal capacity against four bacteria and one yeast, with MIC values ranging from 62.5 to 1000 µg/mL. These nanoparticles were obtained by a simple method with good performance. The inclusion of a dispersing agent, PVA, improved the biocidal efficacy and indicates that the addition of different non-toxic agents can help to enhance the efficacy of the nanoparticles. In the future, this line of work should be further explored, as it may allow the reduction of nanoparticle doses while obtaining the same effect, which could be a step towards their use in in vivo applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.M. and F.E.; Methodology, A.J.M. and F.E.; Validation, A.J.M. and F.E.; Formal analysis, A.J.M., F.E. and M.M.; Investigation, A.J.M. and C.M.; Resources, F.E. and M.M.; Data curation, A.J.M., F.E. and M.M.; Writing—original draft, A.J.M., C.M., M.M. and F.E.; Writing—review & editing, A.J.M., F.E., M.M., E.R. and C.M.; Supervision, F.E., M.M. and E.R.; Project administration, F.E.; Funding acquisition, F.E.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. Plan estatal de Investigación Científica, Técnica y de Innovación 2021-2023. Ref. TED2021-129552B-100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

CICT technical staff of the University of Jaén.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Priya, A. K.; Gnanasekaran, L.; Dutta, K.; Rajendran, S.; Balakrishnan, D.; Soto-Moscoso, M. Biosorption of heavy metals by microorganisms: Evaluation of different underlying mechanisms. Chemosphere. 2022, 307, 135957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Lan, C. Q. Effects of culture pH on cell surface properties and biosorption of Pb (II), Cd (II), Zn (II) of green alga Neochloris oleoabundans. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 468, 143579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tanjil, H.; Akter, S.; Hossain, M.S; Iqbal, A. Evaluation of physical and heavy metal contamination and their distribution in waters around Maddhapara Granite Mine, Bangladesh. Water Cycle. 2024, 5, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registro estatal de emisiones y fuentes contaminantes (PRTR-España). 24/01/2025. https://prtr-es.es/.

- Chen, M.; Wang, D.; Ding, S.; Fan, X.; Jin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Zinc pollution in zones dominated by algae and submerged macrophytes in Lake Taihu. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, X.; Chi, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, N.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Wen, X. Transport, pollution, and health risk of heavy metals in “soil-medicinal and edible plant-human” system: A case study of farmland around the Beiya mining area in Yunnan, China. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 111958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. , Saqlain, L., Ma, J., Khan, Z. I., Ahmad, K., Ashfaq, A., Sultana, R., Muhammad, F.G., Magsood, A., Naeem, M., Malik, I.S.; Munir, M.; Nadeem, M.; Yang, Y. (2022). Evaluation of potential ecological risk and prediction of zinc accumulation and its transfer in soil plants and ruminants: public health implications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 3386–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, H. T.; Hoang, V. H.; Nga, L. T. Q.; Nguyen, V. Q. Effects of Zn pollution on soil: Pollution sources, impacts and solutions. Results in Surf. Interfaces. 2024, 17, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalousek, P.; Holátko, J.; Schreiber, P.; Pluháček, T.; Širůčková Lónová, K.; Radziemska, M.; Tarkowski, P.; Vyhnánek, T.; Hammerschmiedt, T.; Brtnický, M. The effect of chelating agents on the Zn-phytoextraction potential of hemp and soil microbial activity. Chem. biol. technol. agric. 2024, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, F.; Improta, G.; Triassi, M.; Cicatelli, A.; Castiglione, S. Effects of zinc pollution and compost amendment on the root microbiome of a metal tolerant poplar clone. Front. microbiol. 2020, 11, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, H.; Méndez-Fernández, L.; Martinez-Madrid, M.; Rodríguez, P.; Daam, M.A.; Espíndola, E.L.G. Bioaccumulation and chronic toxicity of arsenic and zinc in the aquatic oligochaetes Branchiura sowerbyi and Tubifex tubifex (Annelida, Clitellata). Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 239, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmanescu, M.; Alda, L. M.; Bordean, D. M.; Gogoasa, I.; Gergen, I. Heavy metals health risk assessment for population via consumption of vegetables grown in old mining area; a case study: Banat County, Romania. Chem. Cent. J. 2011, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, A.; Garg, R.; Garg, R.; Gupta, D.; Eddy, N. O. Efficient sequestration of zinc and copper from aqueous media: exploring strategies, mechanisms, and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, M. M.; Nodeh, Z. P.; Dehkordi, K. S.; Salmanvandi, H.; Khorjestan, R. R.; Ghaffarzadeh, M. Soil, air, and water pollution from mining and industrial activities: Sources of pollution, environmental impacts, and prevention and control methods. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, E. R.; Ramsdorf, W. A.; Domingos, L. M. L.; de Souza Miranda, L. P.; Mattoso Filho, N. P.; Cestari, M. M. Ecotoxicological effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) on aquatic organisms: Current research and emerging trends. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zango, Z.U.; Garba, A.; Shittu, F.B.; Iman, S.S.; Haruna, A.; Zango, M.U.; Wadi, I.A.; Bello, U.; Adamu, H,; Keshta, B.E.; Bokov, D.O.; Baigenzhenov, O.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. A state-of-the-art review on green synthesis and modifications of ZnO nanoparticles for organic pollutants decomposition and CO2 conversion. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100588. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Ruiz, E.; Abriouel, H.; Gálvez, A.; Ezzouhri, L.; Lairini, k.; Espínola, F. Heavy metal tolerance of microorganisms isolated from wastewaters: Identification and evaluation of its potential for biosorption. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 210, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Ruiz, E.; Cuartero, M.; Castro, E. Biotechnological use of the ubiquitous fungus Penicillium sp. 8L2: biosorption of Ag(I) and synthesis of silver nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Moya, M.; Martín, C.; Ruiz, E. Biosorption, Recovery and Reuse of Cu(II) by Penicillium sp. 8L2: A Proposal Framed Within Environmental Regeneration and the Sustainability of Mineral Resources. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 11001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Ruiz, E.; Moya, M.; Castro, E. Ag(I) Biosorption and Green Synthesis of Silver/Silver Chloride Nanoparticles by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa 1S1. Nanomater. 2023, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.V.; Vinoth, S.; Baskar, V.; Arun, M.; Gurusaravanan, P. Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles mediated by Dictyota dichotoma endophytic fungi and its photocatalytic degradation of fast green dye and antibacterial applications. S. African J. Bot. 2022, 151, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espínola, F.; Ruiz, E.; Moya, M.; Castro, E. Biocidal and synergistic effect of three types of biologically synthesised silver/silver chloride nanoparticles. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, A.J.; Espinola, F.; Moya, M.; Martín, C.; Ruiz, E. Cu(II) Biosorption and Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles by Staphylococcus epidermidis CECT 4183: Evaluation of the Biocidal Effect. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Liu, Y.; Feng, B.; Zeng, G; Yang, Ch.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, H.; Tan, Zh.; Wang, X. Biosorption of cadmium(II), zinc(II) and lead(II) by Penicillium simplicissimum: Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 160, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Jeevanantham, S.; Kumar, P.S.; Varjani, S.; Yaashikaa, P.R.; Karishma, S. Enhanced Zn(II) ion adsorption on surface modified mixed biomass –Borassus flabellifer and Aspergillus tamarii: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics study. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2020, 153, 112613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunali, S.; Akar, T. Zn(II) biosorption properties of Botrytis cinerea biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 131, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areco, M.M.; Hanela, S.; Duran, J.; Afonso, M.S. Biosorption of Cu(II), Zn(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) by dead biomasses of green alga Ulva lactuca and the development of a sustainable matrix for adsorption implementation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 213-214, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.P.; King, P.; Prasad, V.S.R.K. Zinc biosorption on Tectona grandis L.f. leaves biomass: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. J. Chem. Eng. 2006, 124, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, JL. Zn biosorption by Rhizopus arrhizus and other fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin-quin, T.; Zhi-rong, L.; Ying, D.; Xin-xing, Zn. Biosorption properties of extracellular polymeric substances towards Zn(II) and Cu(II). Desalin.Water Treat. 2012, 45, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garip, S.; Bozoglu, F.; Servercan, F. Differentiation of Mesophilic and Thermophilic Bacteria with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2007, 61, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Ye, Zn. Biosorption of Pb(II) and Zn(II) from aqueous solutions by living B350 biomass. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 55, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.K.; Vishwakarma, M.Ch.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, H; Bhandari, N.S.; Joshi, S.K. The biosorption of Zn2+ by various biomasses from wastewater: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, A.; Khasteganan, N.; Coupe, S.J.; Newman, A.P. A meta-analysis of metal biosorption by suspended bacteria from three phyla. Chemosphere. 2021, 268, 129290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, A.G.; Demeke, T.; Tefera, M.; Mulu, M.; Tesfaye, S. Biosynthesis and characterization of ZnO NPs using aqueous extract of Zehneria scabra L. leaf for comparing antibacterial activities and the efficacies of antioxidant activities. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025. In press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J. Green synthesis of ZnO NPs with long-lasting and ultra-high antimicrobial activity. Surf. Interfaces. 2024, 50, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, B.; Rai, G.B.; Bhandary, R.; Parajuli, P.; Thapa, N.; Kandel, Dh.R.; Mulmi, S.; Shrestha, S.; Malla, S. Antifungal activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) on Fusarium equiseti phytopathogen isolated from tomato plant in Nepal. Heliyon, 2024, 10, e40198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, A.S.; Kamel, A.G.; Eita, M.A.; Elbermawy, Y.; El-Shibiny, A. The cytotoxic potency of green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) using Origanum majorana. Mater. Lett. 2024, 367, 136654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, B.K. Biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticle-functionalized fabrics for antibacterial and biocompatibility evaluations in medical applications: A critical review. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 42, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Yan, Sh.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, W.; Tian, X.; Sol, X.; Han, X. Biomimetic synthesis of mesoporous zinc phosphate nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 477, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, M.; Viswanathan, Dh.; Pandiaraj, S.; Govindasamy, R.; Gomathi, Th.; Vijayakumar, S. Review on phyto-extract methodologies for procuring ZnO NPs and its pharmacological functionalities. Process Biochem. 2024, 147, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaraj, Ch.; Naveenkumar, S.; Kumar, R.Ch.S.; Al-Ghanim, Kh.A.; Natesan, K.; Priyadharsan, A. Ice apple fruit peel assisted bio-synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs): An anticancer, antimicrobial, and larvicidal applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 105, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elankathirselvan, K.; Fathima H, A.; K,P.; Al-Ansari, M.M. Synthesis and characterization of Pyrus communis fruit extract synthesized ZnO NPs and assessed their anti-diabetic and anti-microbial potential. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119450. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, G.L.; Moreira, A.J.; Nóbrega, E.T.D.; Braga, S.; Argentin, M.N.; Da Cunha Camargo, I.L.B.; Azevedo, E.; Pereira, E.C.; Bernardi, M.I.B.; Mascaro, L.H. Selective inhibitory activity of multidrug-resistant bacteria by zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).