Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

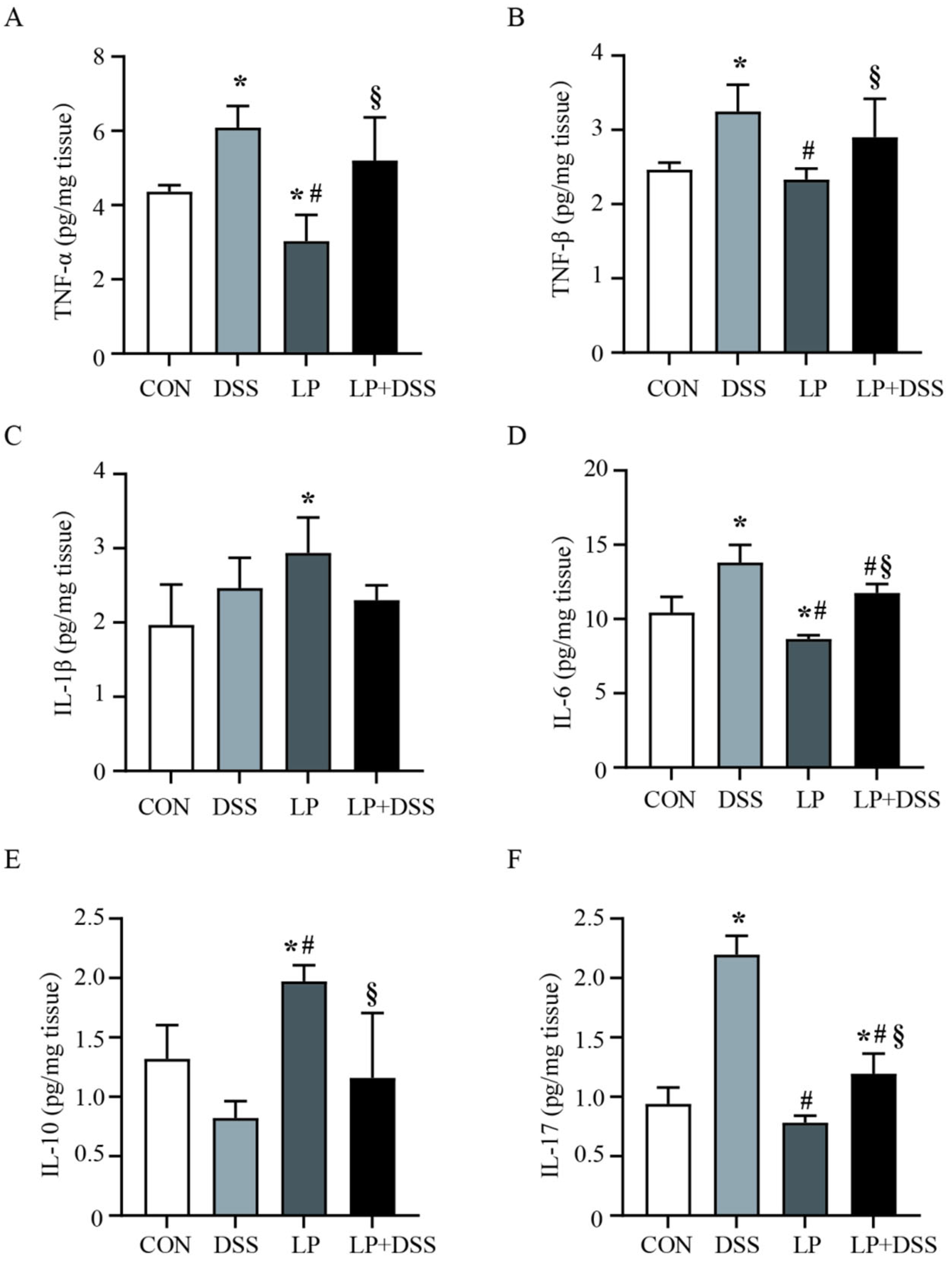

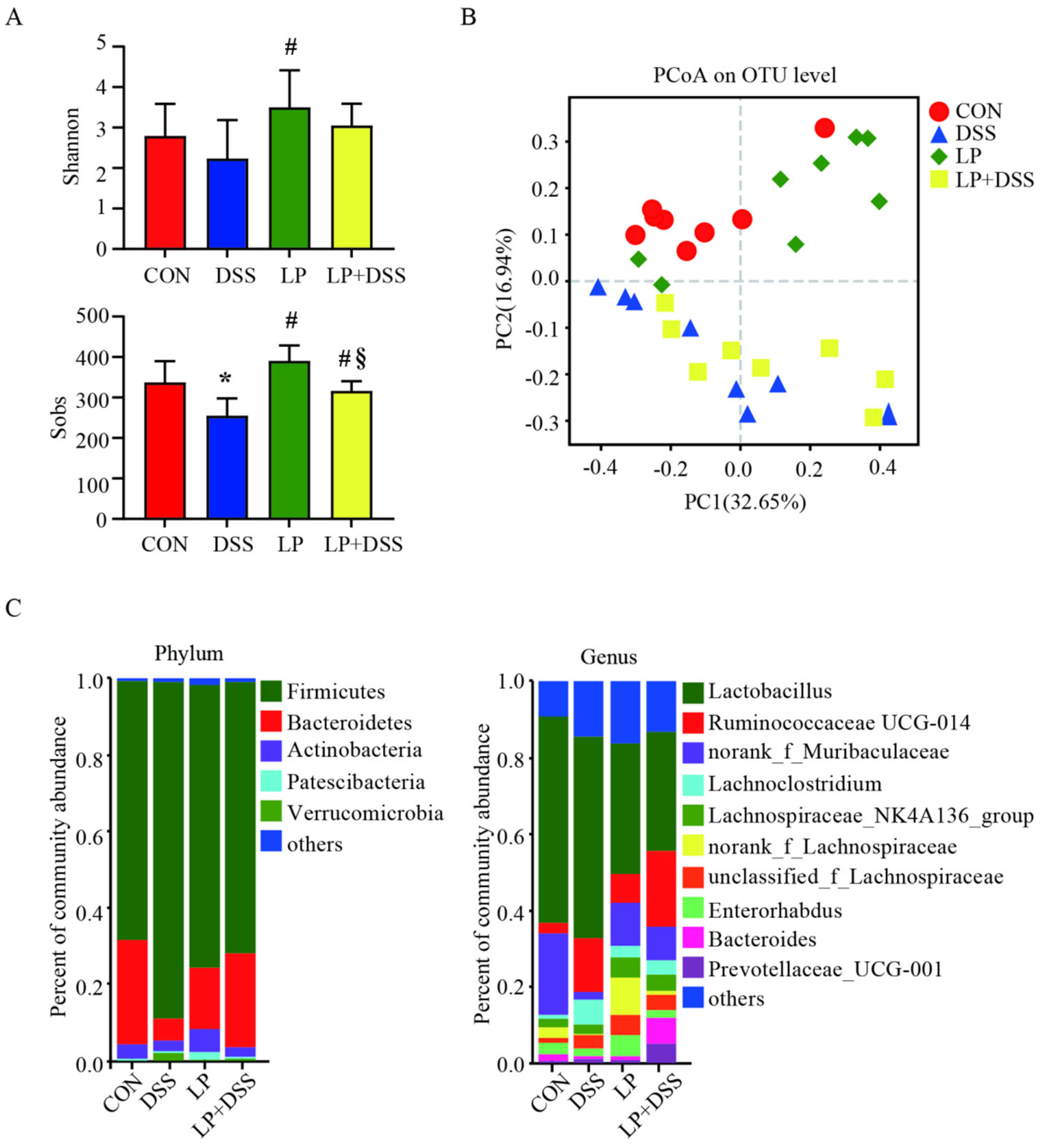

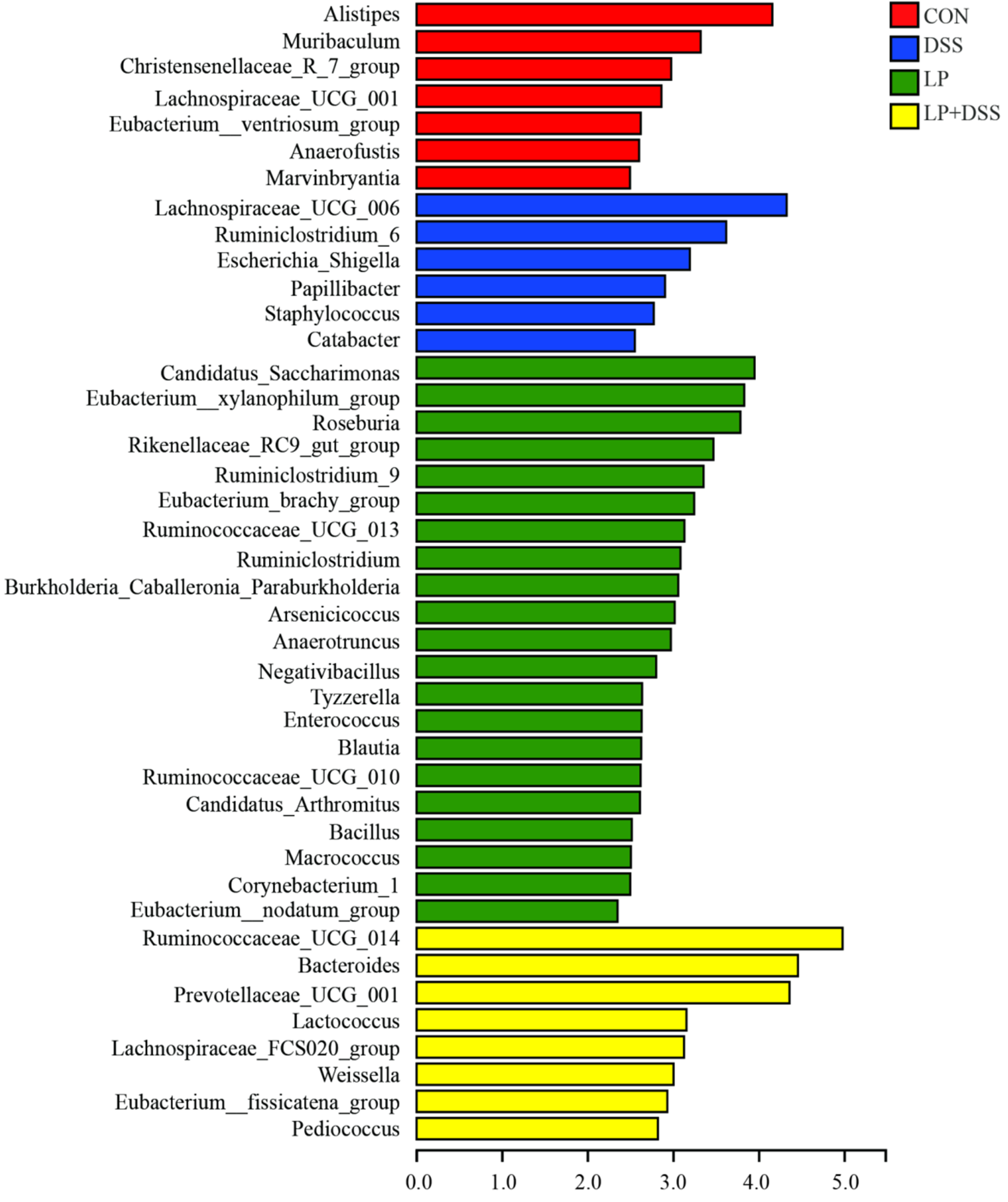

Background/Objectives: Lactobacillus strains are widely used as probiotics in the functional food industry and show potential for treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of dietary supplementation with microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum 17-1 on the intestinal immune response and gut microbiota in mice with colitis. Methods: Mice were pre-fed a diet containing microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum 17-1 for three weeks, followed by colitis induction using 2.5% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water for 8 days. Results: Lactobacillus plantarum 17-1 significantly improved clinical symptoms and histopathological features in colitis-affected mice. Additionally, it effectively suppressed the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-17 in the colon tissue of the mice. The probiotic administration increased the linear discriminant analysis score for several beneficial bacterial taxa, including Ruminococcaceae_UCG_014, Bacteroides, Prevotellaceae_UCG_001, Lactococcus, Weissella, Pediococcus, and so on. Also, Lactobacillus plantarum 17-1 regulated the abundance of inflammation-related metabolites which involved in linolenic acid metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism, primary bile acid biosynthesis and tyrosine metabolism. Conclusions: These findings indicate that microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum 17-1 has a significant anti-inflammatory effect in the DSS-induced colitis model and may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for IBD.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Animal Treatments

2.3. Evaluation of the Disease Activity Index and Histopathology

2.4. Measurement of Colon Cytokines

2.5. DNA Extraction, 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Microbial Analysis

2.6. Untargeted Metabolome Profiling Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

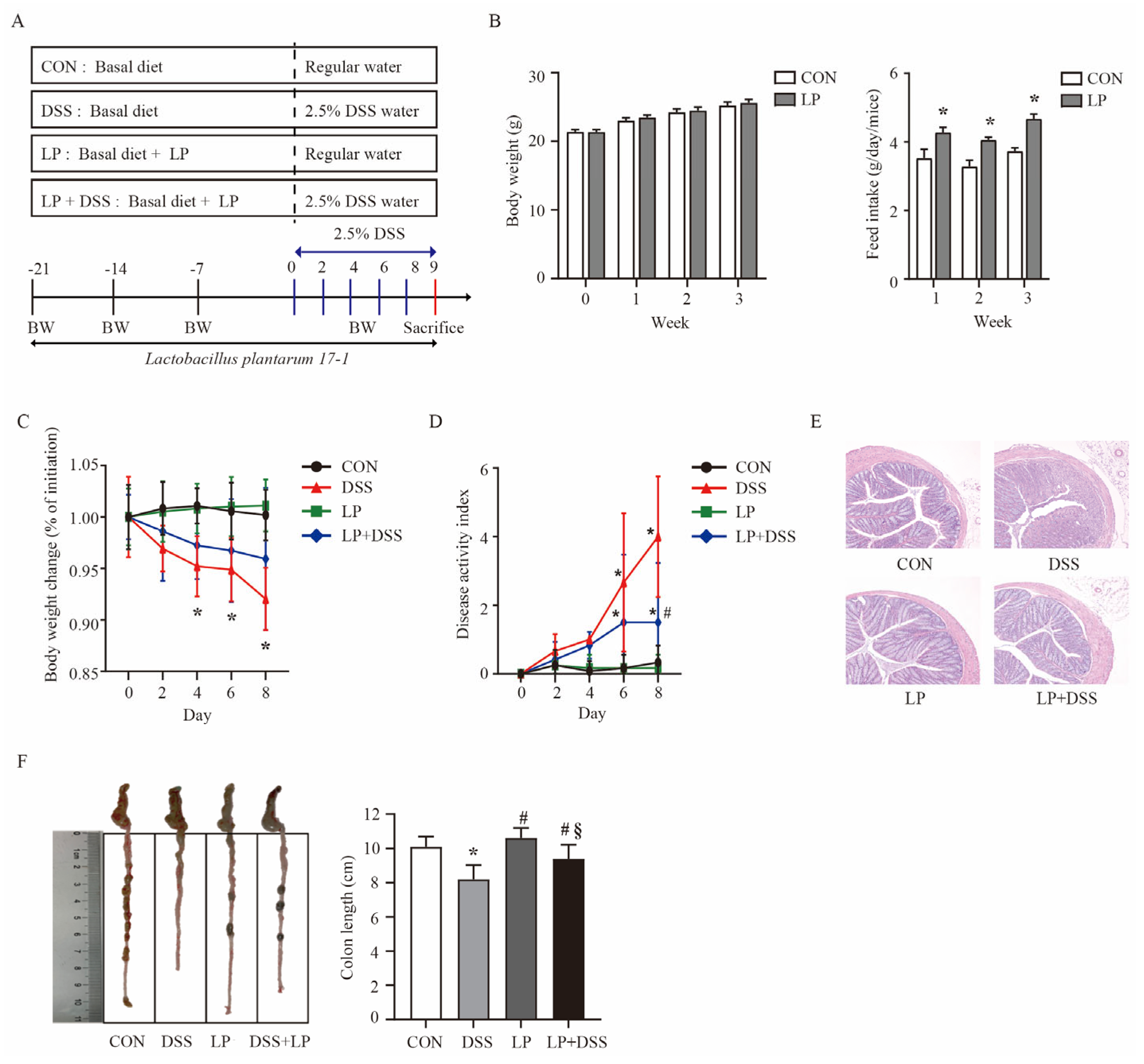

3.1. L. Plantarum 17-1 Ameliorated Clinical Features and Intestinal Injury in DSS-Induced Colitis Mice

3.2. L. Plantarum 17-1 Regulated the Production of Cytokines in DSS-Induced Colitis Mice

3.3. L. Plantarum 17-1 Changed Caecal Microbiota Diversity in DSS-Induced Colitis Mice

3.4. L. Plantarum 17-1 Induced Shift in Gut Microbiota Composition in DSS-Induced Colitis Mice

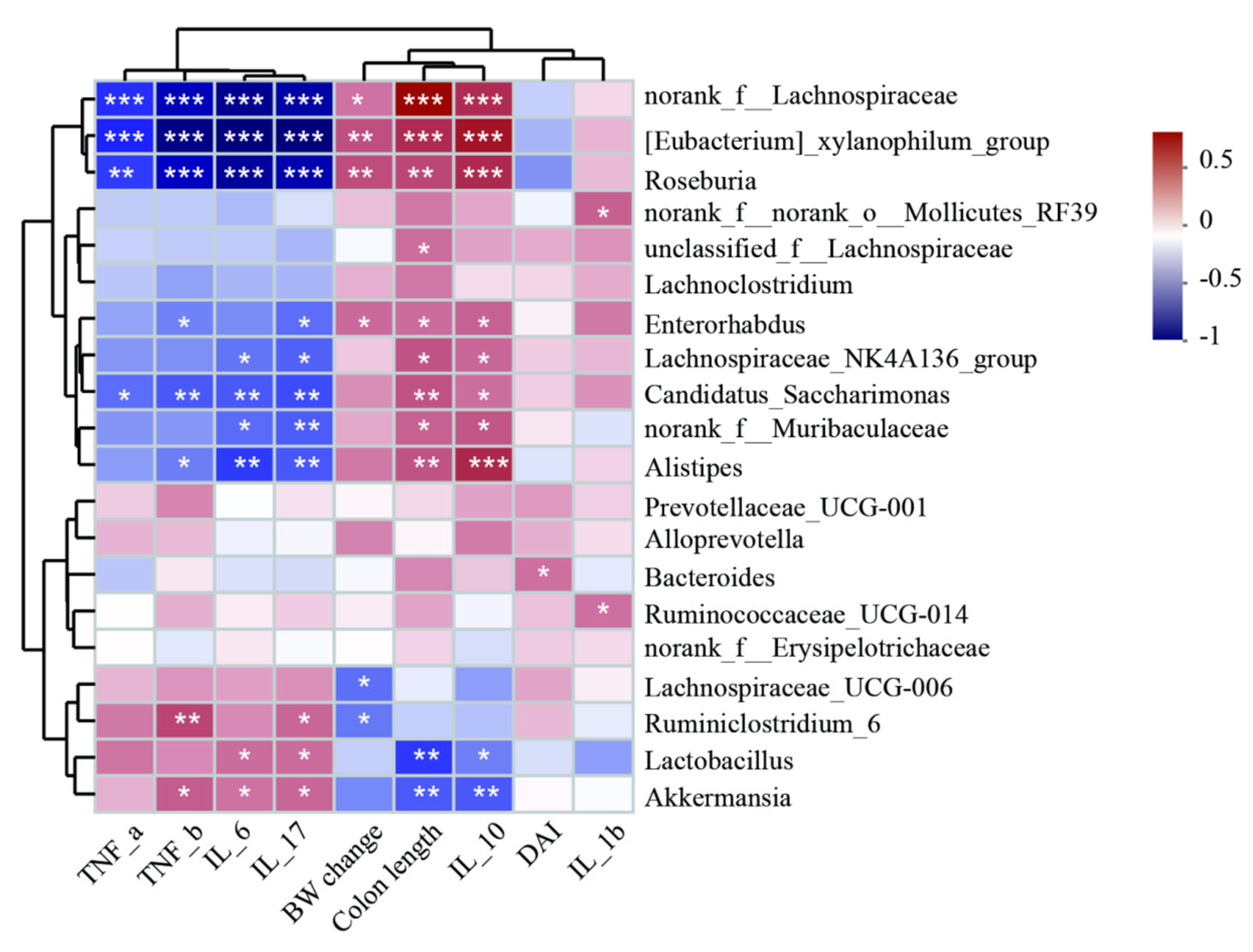

3.5. Spearman Correlation Analysis of Different Abundant Genera and Colitis Injury Indices

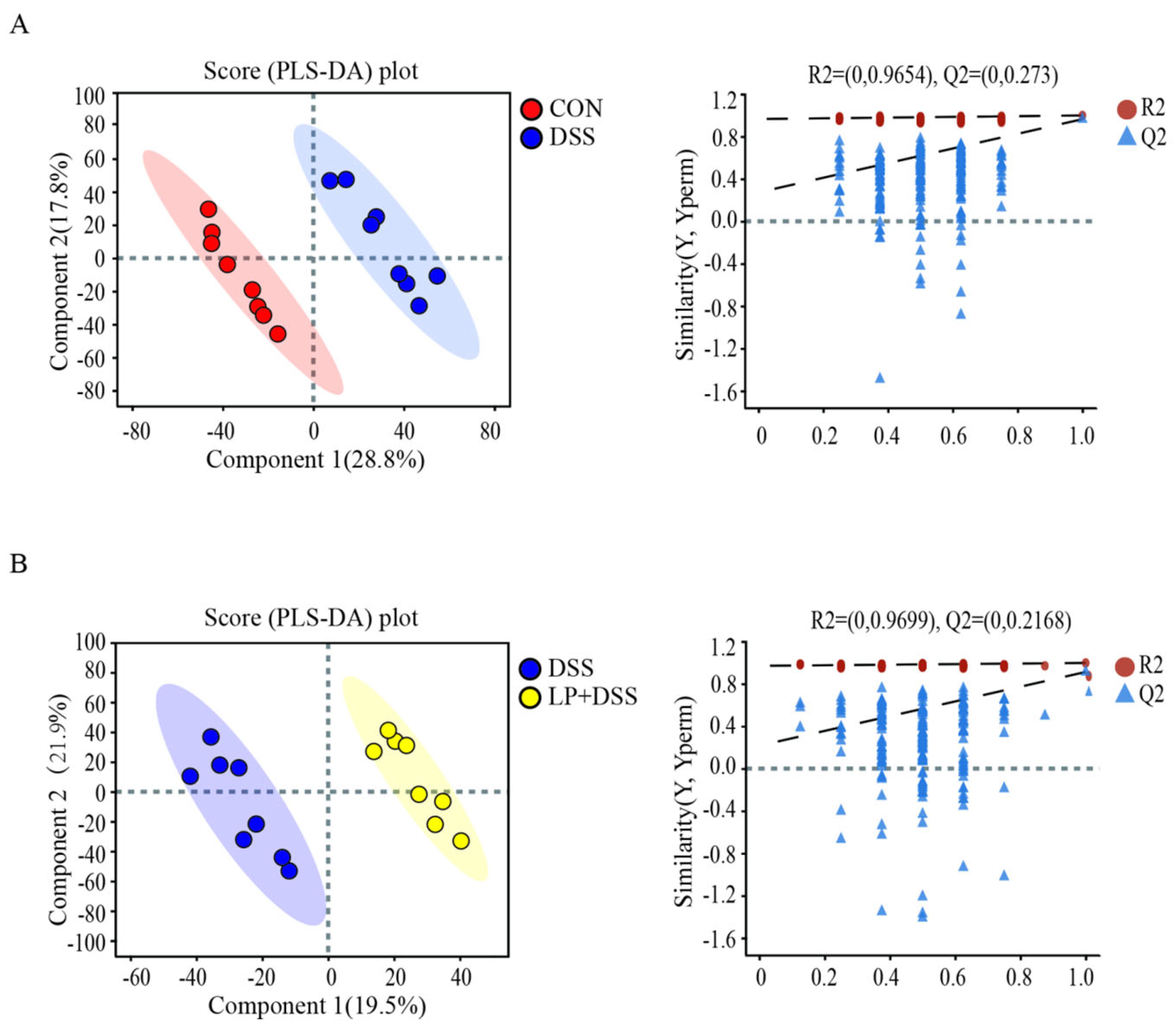

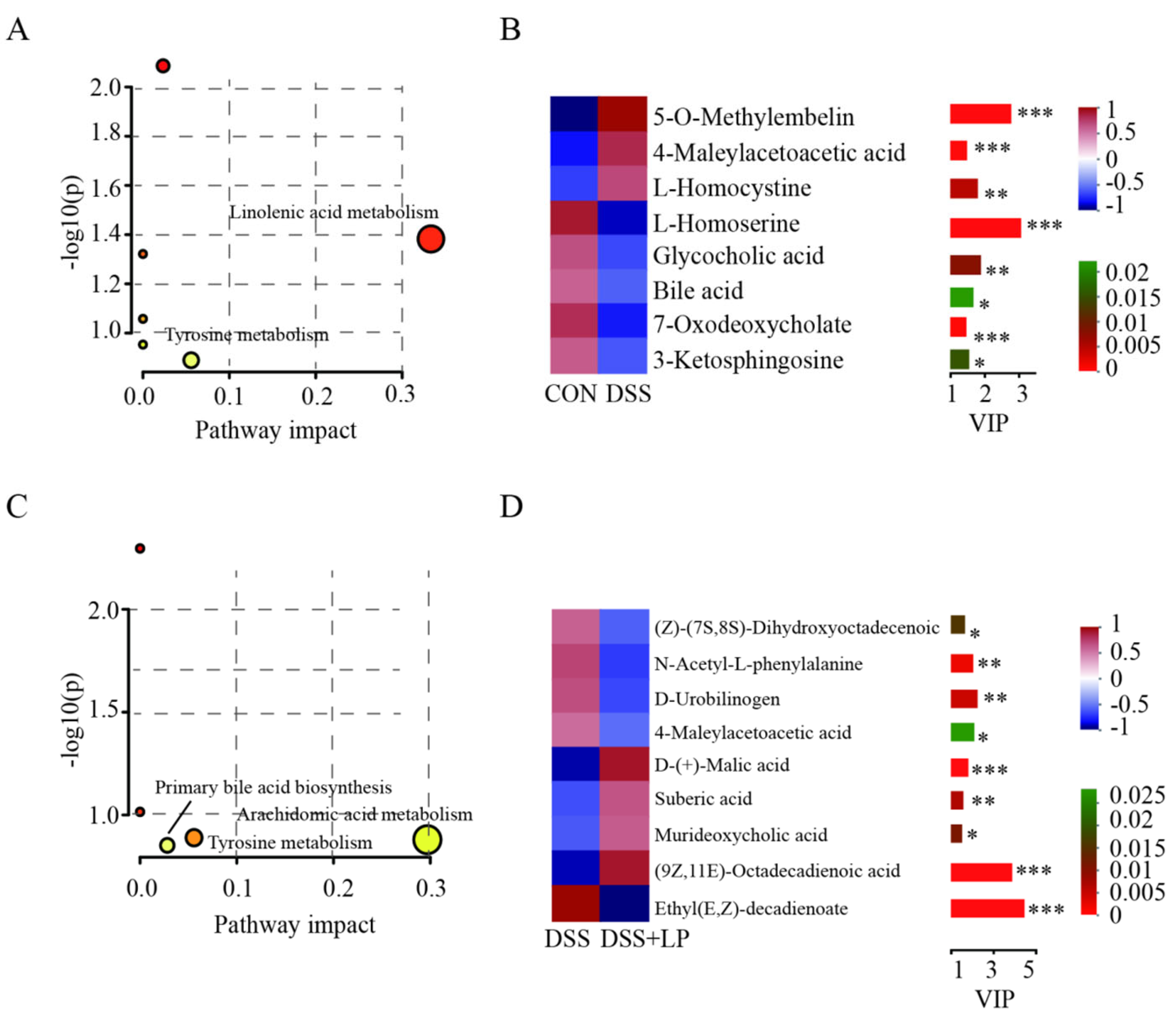

3.6. L. Plantarum 17-1 Altered Gut Metabolic Profiles in DSS-Induced Colitis Mice

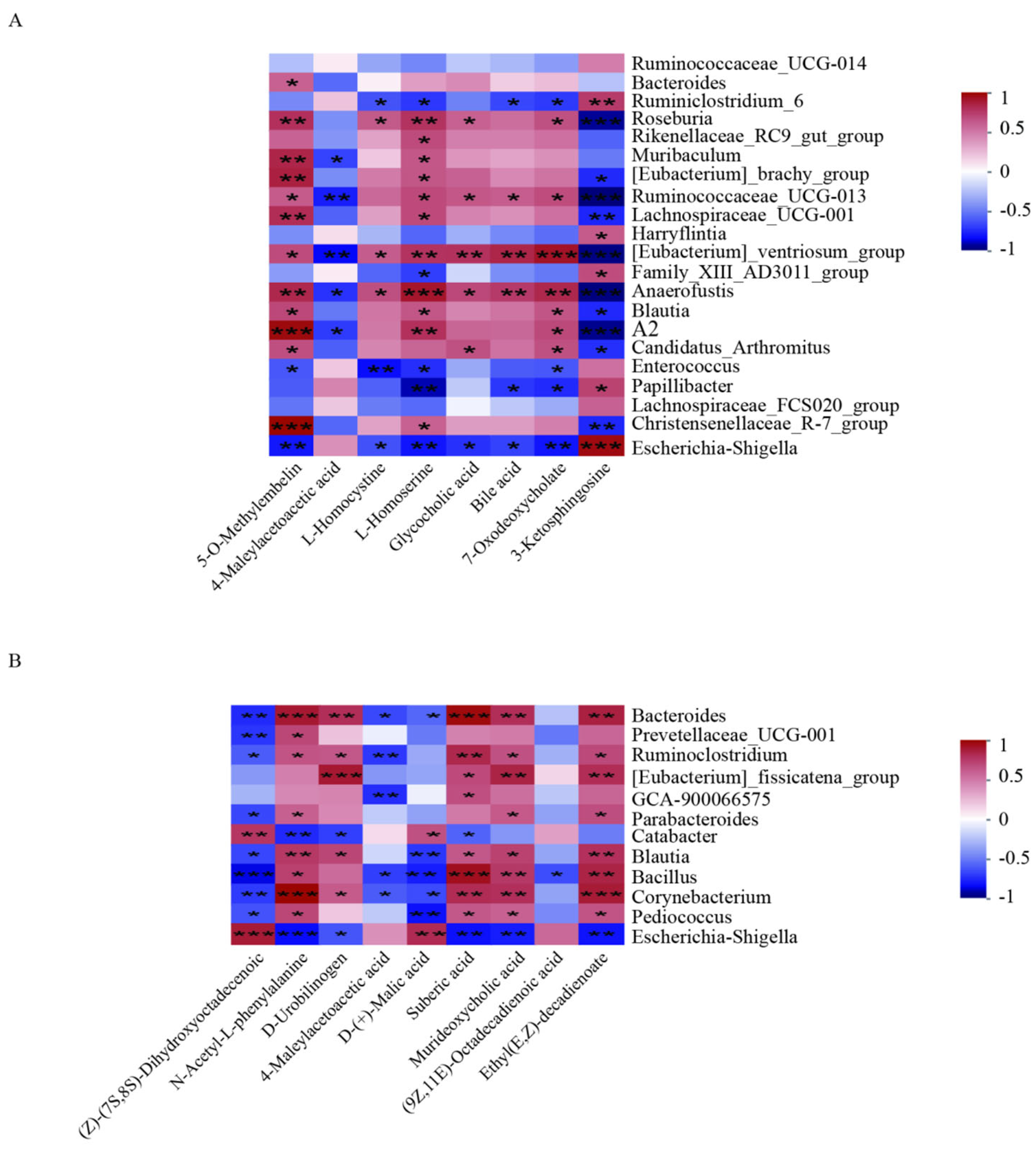

3.7. Spearman Correlation Analysis of Different Abundant Genera and Metabolites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BW | body weight |

| DSS | dextran sulfate sodium |

| DAI | disease activity index |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ESI | electrospray ionization |

| LEfSe | linear discriminant analysis effect size |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| IL | interleukin |

| OTU | operational taxonomic unit |

| SD | standard deviation |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

| UHPLC-MS | ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PLS-DA | partial least-squares discrimination analysis |

| QC | quality control |

| VIP | variable importance in the projection |

References

- Ungaro, R.; Mehandru, S.; Allen, P. B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. and Colombel, J. F. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1756-1770.

- Baumgart, D. C. and Sandborn, W. J. Crohn's disease. Lancet 2012, 380, 1590-1605.

- Kostic, A.D.; Xavier, R.J.; Gevers, D. The Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Status and the Future Ahead. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1489–1499. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G. P. and Papadakis, K. A. Mechanisms of disease: Inflammatory bowel diseases. Mayo Clin Proc 2019, 94, 155-165.

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.J.; Goethel, A.; Girardin, S.E.; Philpott, D.J. Innate Immune Influences on the Gut Microbiome: Lessons from Mouse Models. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 992–1004. [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.L.; Flint, H.J. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–672. [CrossRef]

- Nusbaum, D.J.; Sun, F.; Ren, J.; Zhu, Z.; Ramsy, N.; Pervolarakis, N.; Kunde, S.; England, W.; Gao, B.; Fiehn, O.; et al. Gut microbial and metabolomic profiles after fecal microbiota transplantation in pediatric ulcerative colitis patients. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Thomas, A.; Croft, N.; Newby, E.; Akobeng, A.; Sawczenko, A.; Fell, J.; Murphy, M.S.; Beattie, R.; Sandhu, B.; et al. Systematic Review of the Evidence Base for the Medical Treatment of Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 50, S14–34. [CrossRef]

- Troncone, E.; Monteleone, G. The safety of non-biological treatments in Ulcerative Colitis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2017, 16, 779–789. [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, W.; Lv, L.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J. J.; Li, Y. T.; Ye, J. Z. et al. Pediococcus pentosaceus LI05 alleviates DSS-induced colitis by modulating immunological profiles, the gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid levels in a mouse model. Microb Biotechnol 2020, 13, 1228-1244.

- Chen, P.; Xu, H.; Tang, H.; Zhao, F.; Yang, C.; Kwok, L.; Cong, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; et al. Modulation of gut mucosal microbiota as a mechanism of probiotics-based adjunctive therapy for ulcerative colitis. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 2032–2043. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. W.; Kang, H. O.; Seo, M. J.; Park, S. H. and Lee, D. H. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum K159 using alginate and gellan gum mixture: Optimization of formulation variables using response surface methodology. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 25, 10-18.

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.; Ahn, J.B.; Kim, J.H.; Ma, H.W.; Seo, D.H.; Che, X.; Park, K.C.; Jeon, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum CBT LP3 ameliorates colitis via modulating T cells in mice. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 2020, 310, 151391. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Shin, J.-S.; Chung, K.-S.; Han, H.-S.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Ji, Y.W.; Ha, Y.; Kang, J.; et al. Immunostimulatory Effects of Live Lactobacillus sakei K040706 on the CYP-Induced Immunosuppression Mouse Model. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3573. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Luo, Y.; Qian, F.; Mu, G.; Tuo, Y. The ameliorative effect ofLactobacillus plantarum-12 on DSS-induced murine colitis. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5205–5222. [CrossRef]

- Campana, R.; van Hemert, S.; Baffone, W. Strain-specific probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria and their interference with human intestinal pathogens invasion. Gut Pathog. 2017, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Liang, X.; Yun, T.; Guo, W. Growth and survival of microencapsulated probiotics prepared by emulsion and internal gelation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1398–1404. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Song, X.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lai, P.; Wang, S.; Ai, L. Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 alleviates DSS-induced colitis by regulating the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway and gut microbiota composition. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 67. [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560.

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Fang, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Gao, R. A sensitive method for the determination of the gender difference of neuroactive metabolites in tryptophan and dopamine pathways in mouse serum and brain by UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1093-1094, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Fang, J. Progress on the mechanisms of Lactobacillus plantarum to improve intestinal barrier function in ulcerative colitis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 124, 109505. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Hao, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Lin, Q. Probiotics for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a review of experimental research from 2018 to 2022. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1211271. [CrossRef]

- Ouwehand, A.C.; Forssten, S.; Hibberd, A.A.; Lyra, A.; Stahl, B. Probiotic approach to prevent antibiotic resistance. Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 246–255. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Jia, H.; Feng, Q.; Wang, D.; Liang, D.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, L.; Li, Y.; et al. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 895–905. [CrossRef]

- Haneishi, Y.; Furuya, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Picarelli, A.; Rossi, M.; Miyamoto, J. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3817. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yue, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ding, M.; Li, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Zhao, J.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM1143 Alleviates Chronic Diarrhea via Inflammation Regulation and Gut Microbiota Modulation: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.; Guarner, F.; Pérez-Arribas, L. V.; Sánchez, B.; Borruel, N. and Manichanh, C. Probiotics as anti-inflammatory agents in IBD: Mechanisms of action and clinical evidence. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 2832.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Strain-specific regulative effects of Lactobacillus plantarum on intestinal barrier dysfunction are associated with their capsular polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1343–1352. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Q.; Feng, J.; Zhao, X. Lactobacillus plantarum Restores Intestinal Permeability Disrupted by Salmonella Infection in Newly-hatched Chicks. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2229. [CrossRef]

- Keubler, L. M.; Buettner, M.; Häger, C. and Bleich, A. A. A multihit model: Colitis lessons from the interleukin-10-deficient mouse. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015, 21, 1967-1975.

- Yuan, Y.; Li, N.; Fu, M.; Ye, M. Identification of Critical Modules and Biomarkers of Ulcerative Colitis by Using WGCNA. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, ume 16, 1611–1628. [CrossRef]

- Papoutsopoulou, S.; Pollock, L.; Walker, C.; Tench, W.; Samad, S.S.; Bergey, F.; Lenzi, L.; Sheibani-Tezerji, R.; Rosenstiel, P.; Alam, M.T.; et al. Impact of Interleukin 10 Deficiency on Intestinal Epithelium Responses to Inflammatory Signals. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.N.; St Amand, A.L.; Feldman, R.A.; Boedeker, E.C.; Harpaz, N.; Pace, N.R. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13780–13785. [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Xia, Y.; Wang, G.; Xiong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Ai, L. The bsh1 gene of Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 ameliorates liver injury in colitis mice. npj Sci. Food 2025, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Palmela, C.; Chevarin, C.; Xu, Z.; Torres, J.; Sevrin, G.; Hirten, R.; Barnich, N.; Ng, S.C.; Colombel, J.-F. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2017, 67, 574–587. [CrossRef]

- Chingwaru, W.; Vidmar, J. Potential of Zimbabwean commercial probiotic products and strains of Lactobacillus plantarum as prophylaxis and therapy against diarrhoea caused by Escherichia coli in children. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. and Li, J. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: A trigger for gut inflammation and barrier dysfunction. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1234567.

- Han, Y.; Teng, T.M.; Han, J.; Kim, H.S. Antibiotic-associated changes in Akkermansia muciniphila alter its effects on host metabolic health. Microbiome 2025, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Depommier, C.; Derrien, M.; Everard, A.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila: paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 625–637. [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; Van Der Veeken, J.; DeRoos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J.; et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013, 504, 451–455. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. M.; Howitt, M. R.; Panikov, N.; Michaud, M.; Gallini, C. A.; Bohlooly-Y, M.; Glickman, J. N. and Garrett, W. S. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 2013, 341, 569-573.

- Tian, B.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Q.; Liu, H.; Nie, C.; Zhang, Z.; An, W.; Li, J. Lycium ruthenicum Anthocyanins Attenuate High-Fat Diet-Induced Colonic Barrier Dysfunction and Inflammation in Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiota. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 2000745. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Xie, Y.; Shi, Y.; Le, G. Dietary methionine restriction improves gut microbiota composition and prevents cognitive impairment ind-galactose-induced aging mice. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12896–12914. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, R.; Xu, T.; Cai, M.; Mao, R.; Huang, L.; Yang, K.; Zeng, X.; Peilong, S. Modulating effects of Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides on the immune response by regulating gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 3050–3064. [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhu, M.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.; Hu, L.; Jing, W.; Lu, H.; Wang, S. Dihydromyricetin improves DSS-induced colitis in mice via modulation of fecal-bacteria-related bile acid metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 171, 105767. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Cao, X.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, S.; Xu, Z.; Liao, Q.; Hong, Y.; et al. Integrated microbiome-metabolomics analysis reveals the potential therapeutic mechanism of Zuo-Jin-Wan in ulcerative colitis. Phytomedicine 2022, 98, 153914. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H.; Saier, M.H. Gut Bacteroides species in health and disease. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.L.; Lemos, L.; Rodrigues, N.M.; Pereira, V.B.; Barros, P.A.V.; Canesso, M.C.C.; Guimarães, M.A.F.; Cara, D.C.; Miyoshi, A.; Azevedo, V.A.; et al. Immunomodulatory effects of different strains of Lactococcus lactis in DSS-induced colitis. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 1203–1215. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.M.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.K.K.; Shen, J.; Chan, R.L.Y.; Lu, L.; Hu, W.; Li, M.X.; Li, L.F.; Ren, S.X.; et al. Cathelicidin-encoding Lactococcus lactis promotes mucosal repair in murine experimental colitis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 609–619. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Weissella paramesenteroides NRIC1542 inhibits dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice through regulating gut microbiota and SIRT1/NF-κB signaling pathway. FASEB Journal 2024, 38, e23791.

- Lee, J.-H.; Chung, K.-S.; Shin, J.-S.; Jung, S.-H.; Lee, S.; Lee, M.-K.; Hong, H.-D.; Rhee, Y.K.; Lee, K.-T. Anti-Colitic Effect of an Exopolysaccharide Fraction from Pediococcus pentosaceus KFT-18 on Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis through Suppression of Inflammatory Mediators. Polymers 2022, 14, 3594. [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Newhart, S.L.; Brotto, L.; Brotto, M. Lipidomics profiling of the linoleic acid metabolites after whole-body vibration in humans. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2816, 241-252.

- Li, X.; Duan, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, R.; Feng, K.; Kathuria, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yu, Y.; Cao, Y. Transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal the alleviation effect of pectic polysaccharide on dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 288, 138755. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ahn, M.; Choi, Y.; Kang, T.; Kim, J.; Lee, N.H.; Kim, G.O.; Shin, T. Alpha-Linolenic Acid Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1876–1883. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hou, B.-L.; Cheng, W.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Y.-N. [Mechanism of tryptanthrin in treatment of ulcerative colitis in mice based on serum metabolomics].. 2023, 48, 2193–2202. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, B.-R.; Li, D.-H.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Jiang, Z.-M.; Ning, S.-B.; Sun, T. WKB ameliorates DSS-induced colitis through inhibiting enteric glial cells activation and altering the intestinal microbiota. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Shang, J.; Liu, L.; Tang, Z.; Meng, X. Strains producing different short-chain fatty acids alleviate DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by regulating intestinal microecology. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12156–12169. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Fan, S.; Meng, P.; Ma, M.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Su, X.; Lu, C. Dietary Dihydroquercetin Alleviated Colitis via the Short-Chain Fatty Acids/miR-10a-5p/PI3K-Akt Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 23211–23223. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ye, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Yu, M.; Han, J.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Lv, Y.; et al. Gut bacteria Prevotellaceae related lithocholic acid metabolism promotes colonic inflammation. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.l Ran, X.; Gu, Z.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Wen, L.; Ji, G.; Wang, R. Bile acid-gut microbiota imbalance in cholestasis and its long-term effect in mice. mSystems 2024, 9, e0012724.

- Tang, J.; Xu, W.; Yu, Y.; Yin, S.; Ye, B.-C.; Zhou, Y. The role of the gut microbial metabolism of sterols and bile acids in human health. Biochimie 2024, 230, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, M.-Y.; Liu, Y.-X.; Yu, J.-Y.; Wang, Y.-B.; Zhang, X.-J.; Sun, H.-P. Branched-chain amino acids promote hepatic Cyp7a1 expression and bile acid synthesis via suppressing FGF21-ERK pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 46, 662–671. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).