Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain Preparation and Growth Conditions

2.2. Animals, Diets and Experimental Design

2.3. Serum Analysis

2.4. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.6. Quantitative Analyses of Lipids and Short-Chain Fatty Acids

2.7. Histological Analysis of Colon and Ileum

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG, Pediococcus pentosaceus K28, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RP12 and Levilactobacillus brevis RP21 on Body

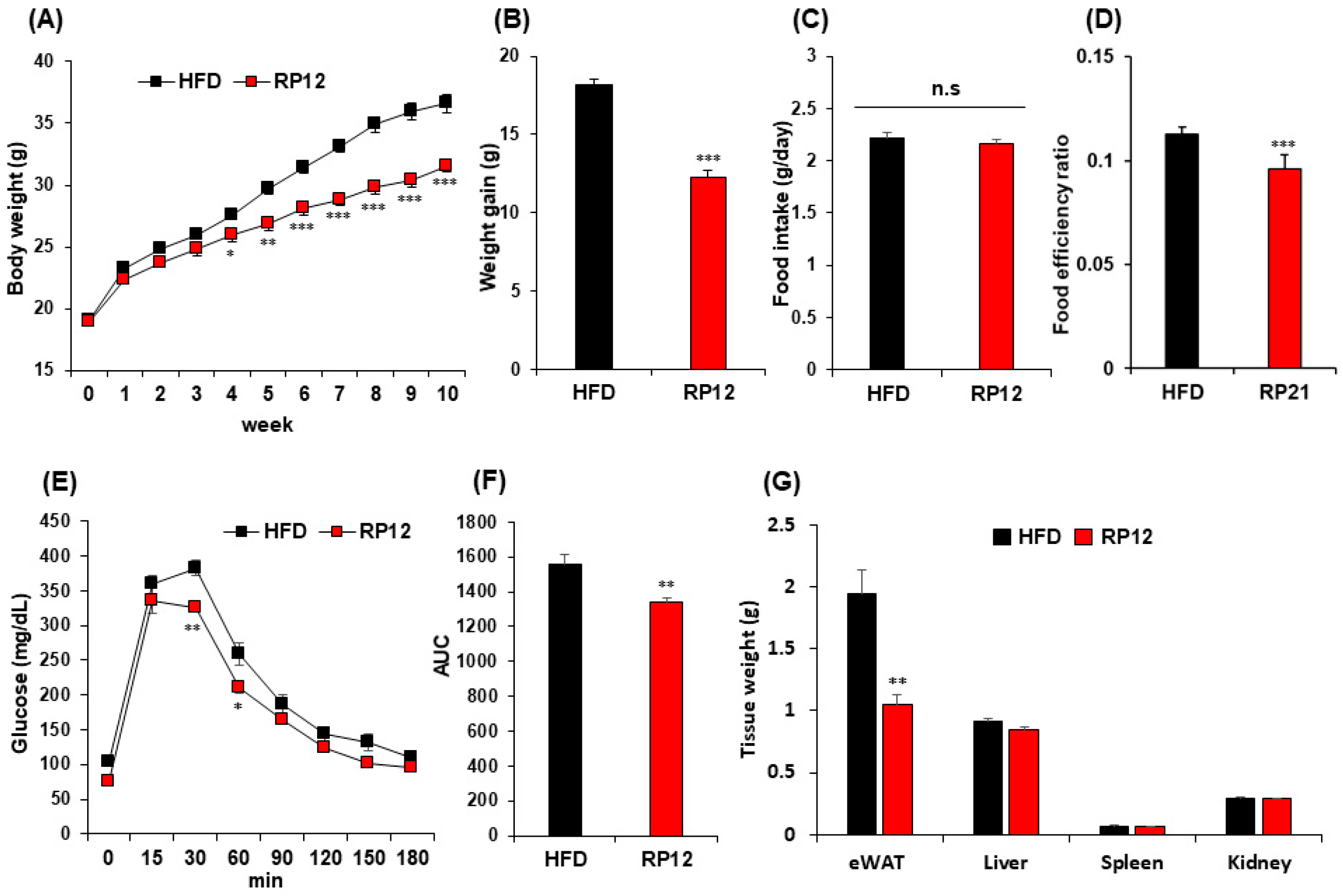

3.2. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RP12 on Body, Visceral Organs and Fat Tissue Weight

3.3. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RP12 on Serum Biochemical Parameters

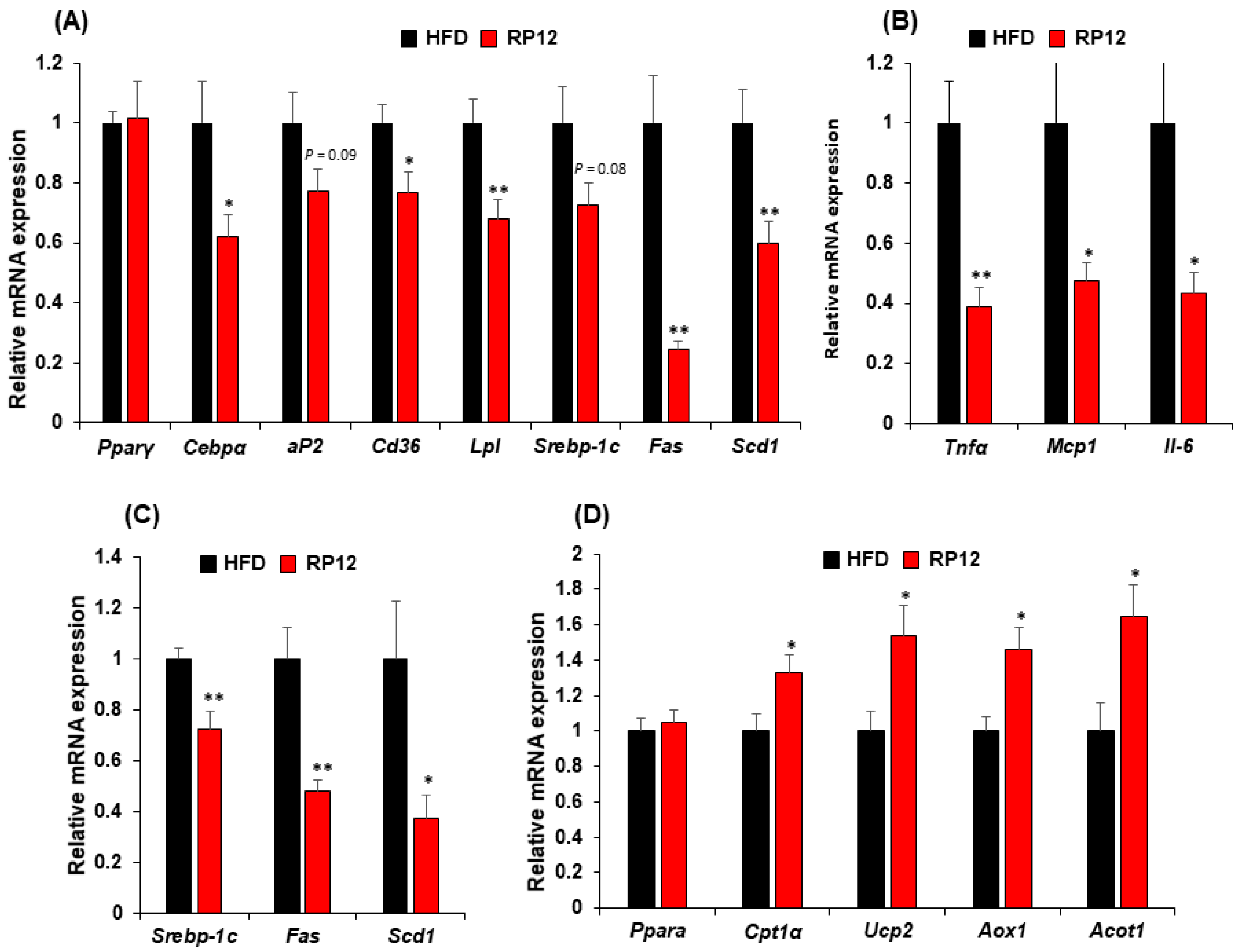

3.4. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RP12 on Genes Involved in Lipid Metabolism in Epididymal Fat Tissue and Liver

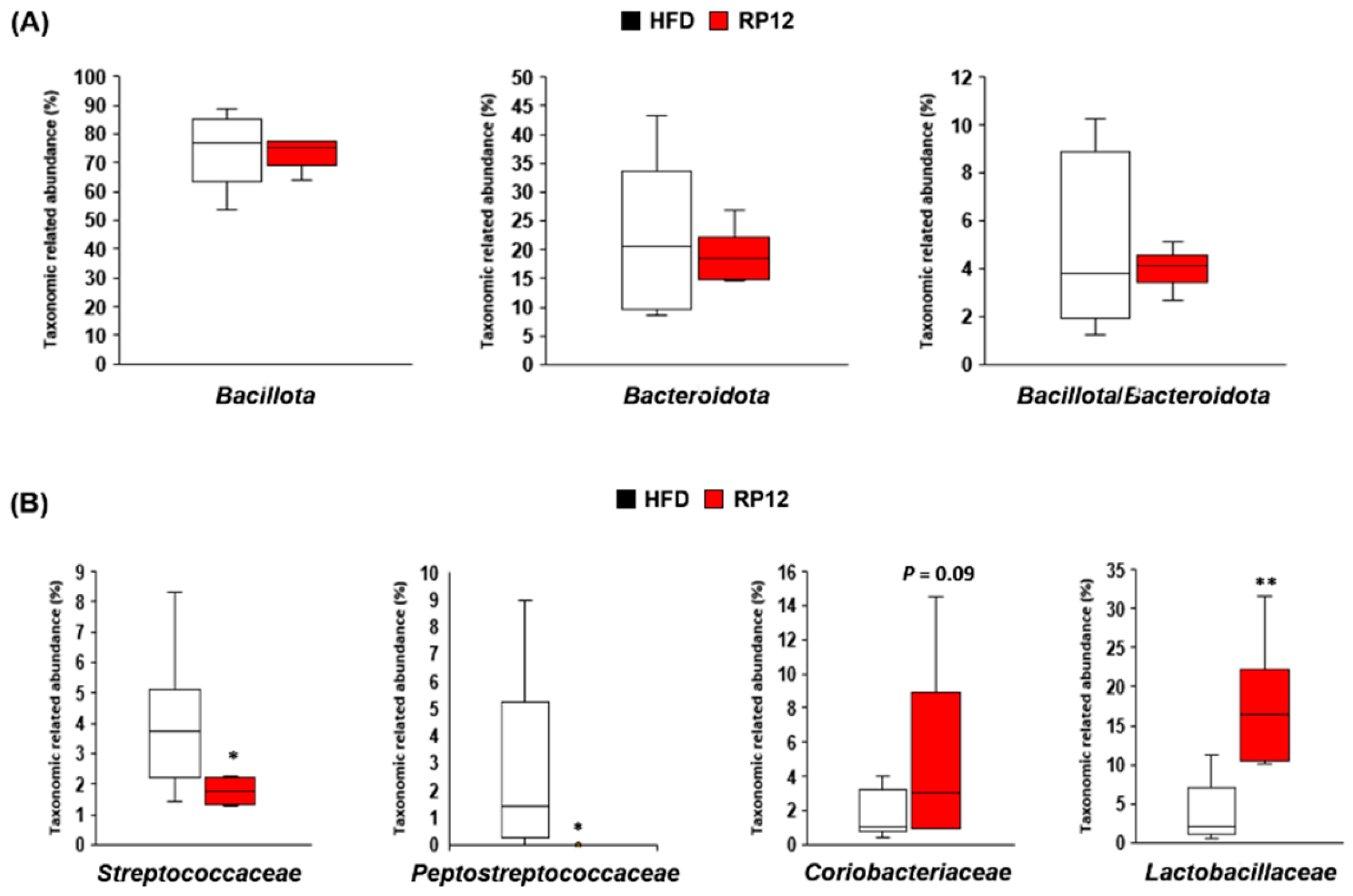

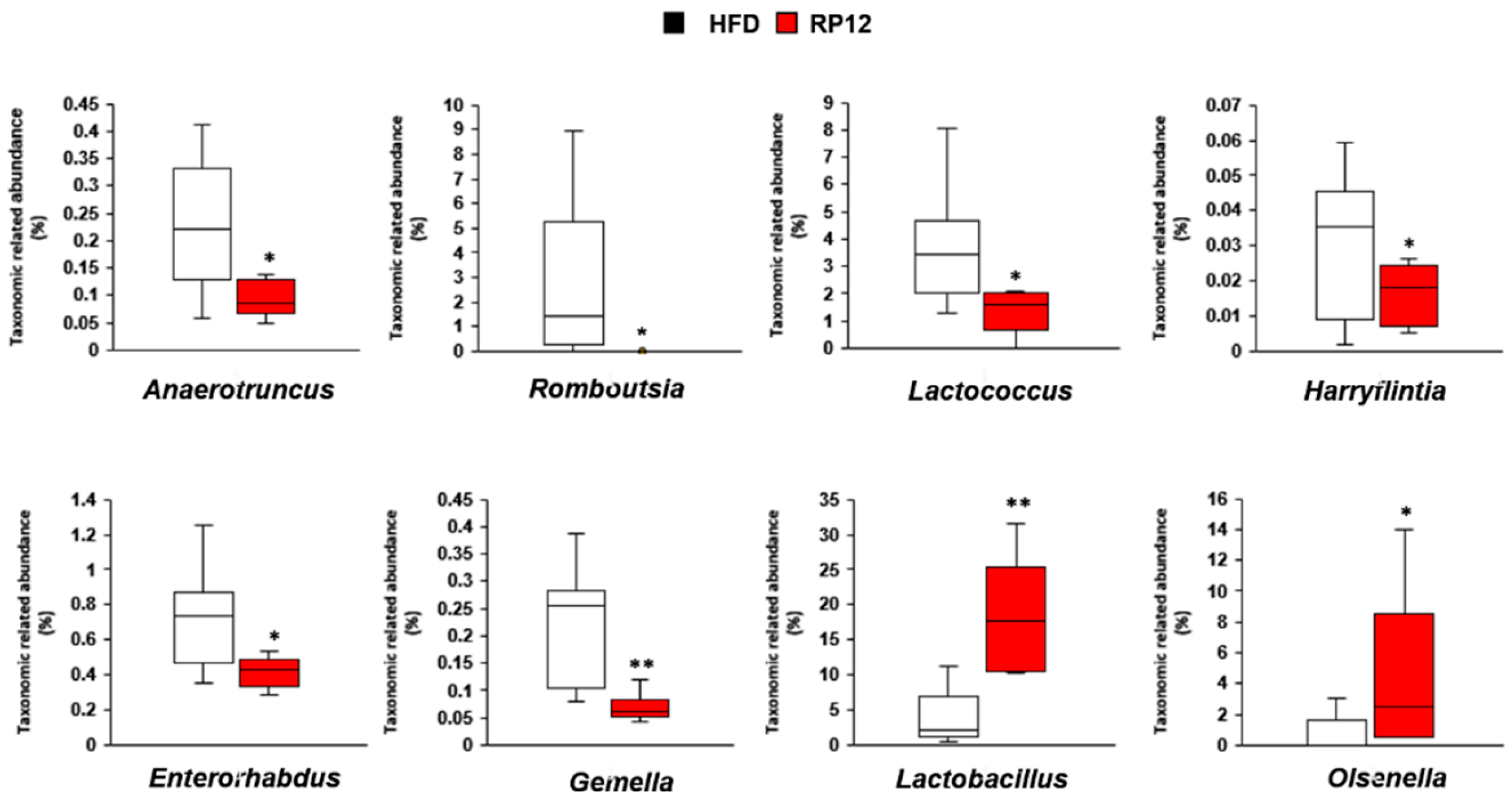

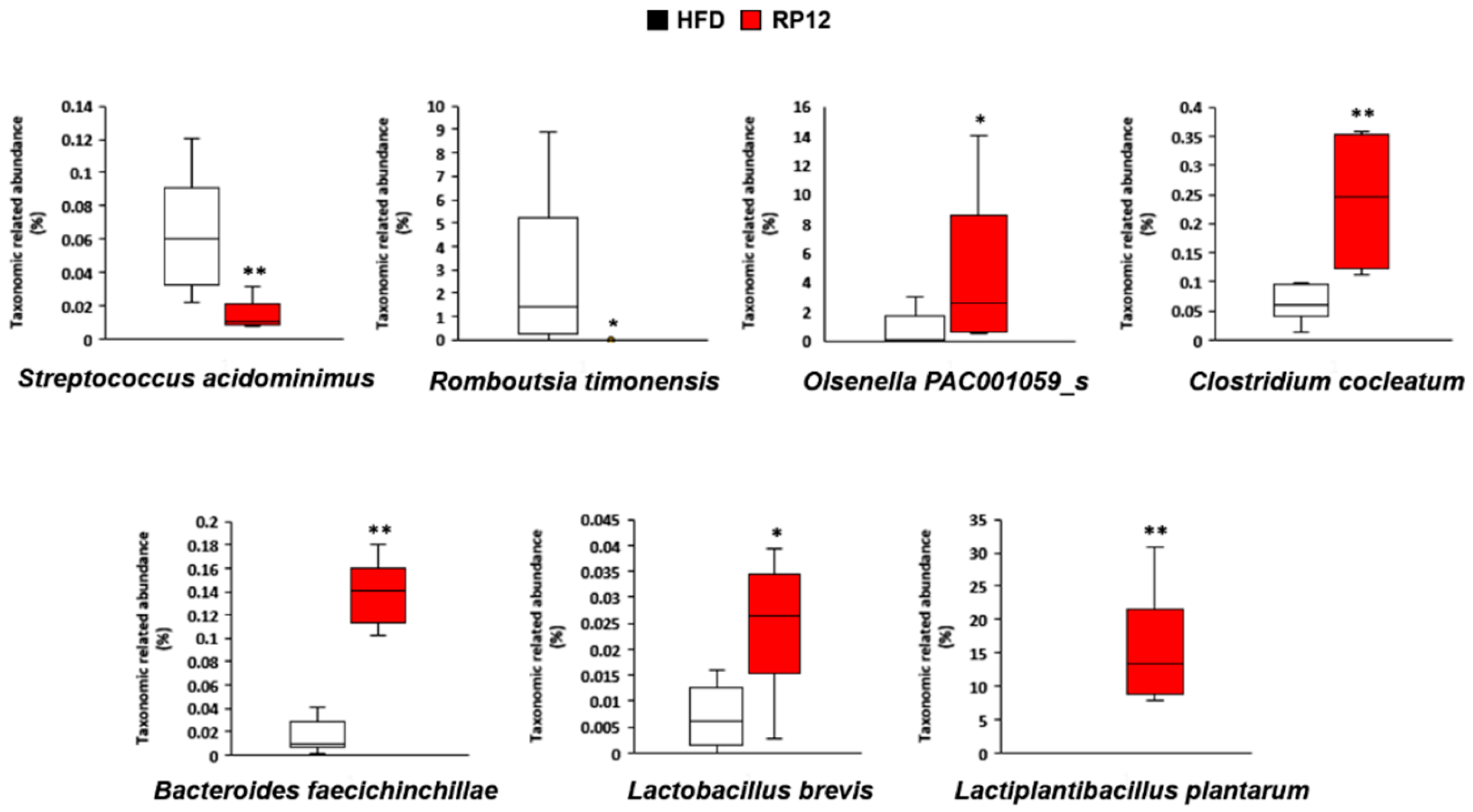

3.5. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RP12 on Changes in Ratio and Composition of Fecal Microbiota

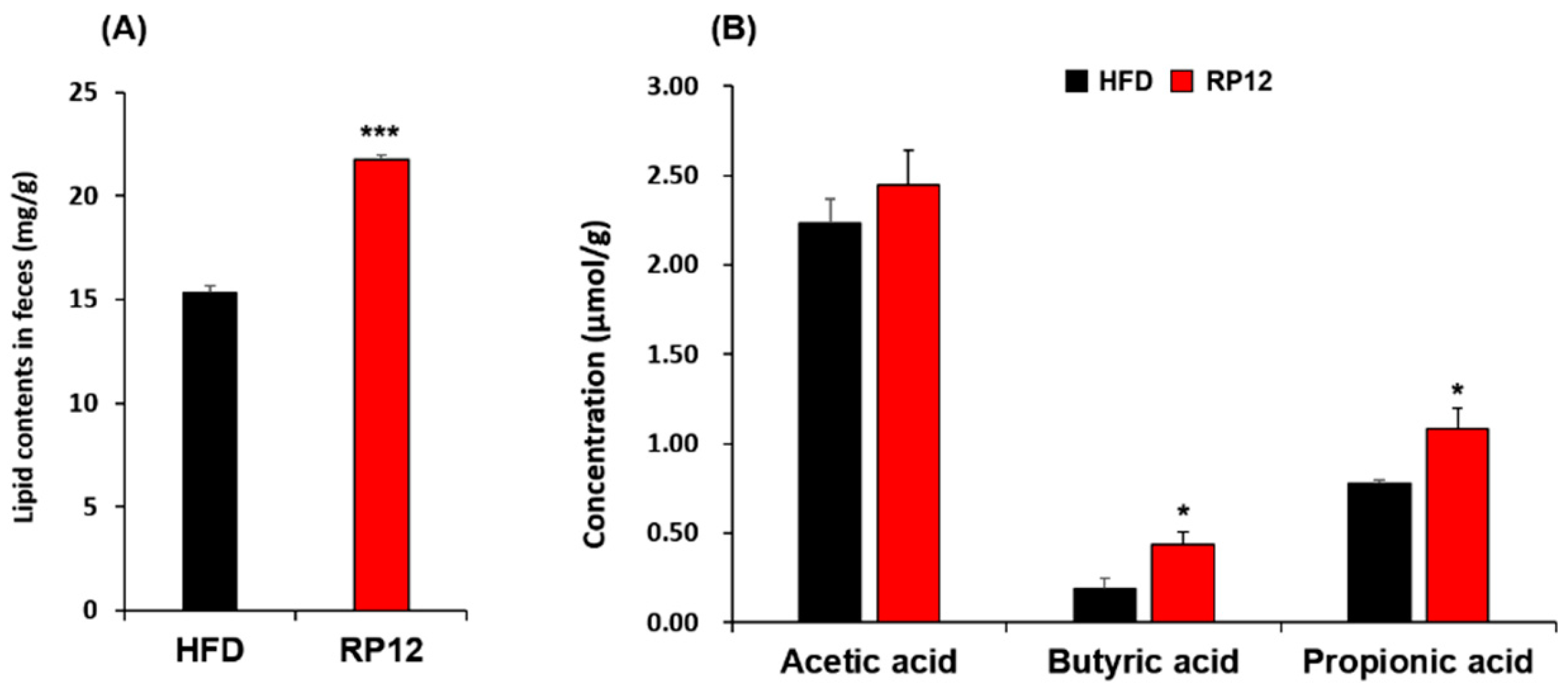

3.6. Concentrations of Lipids and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Feces

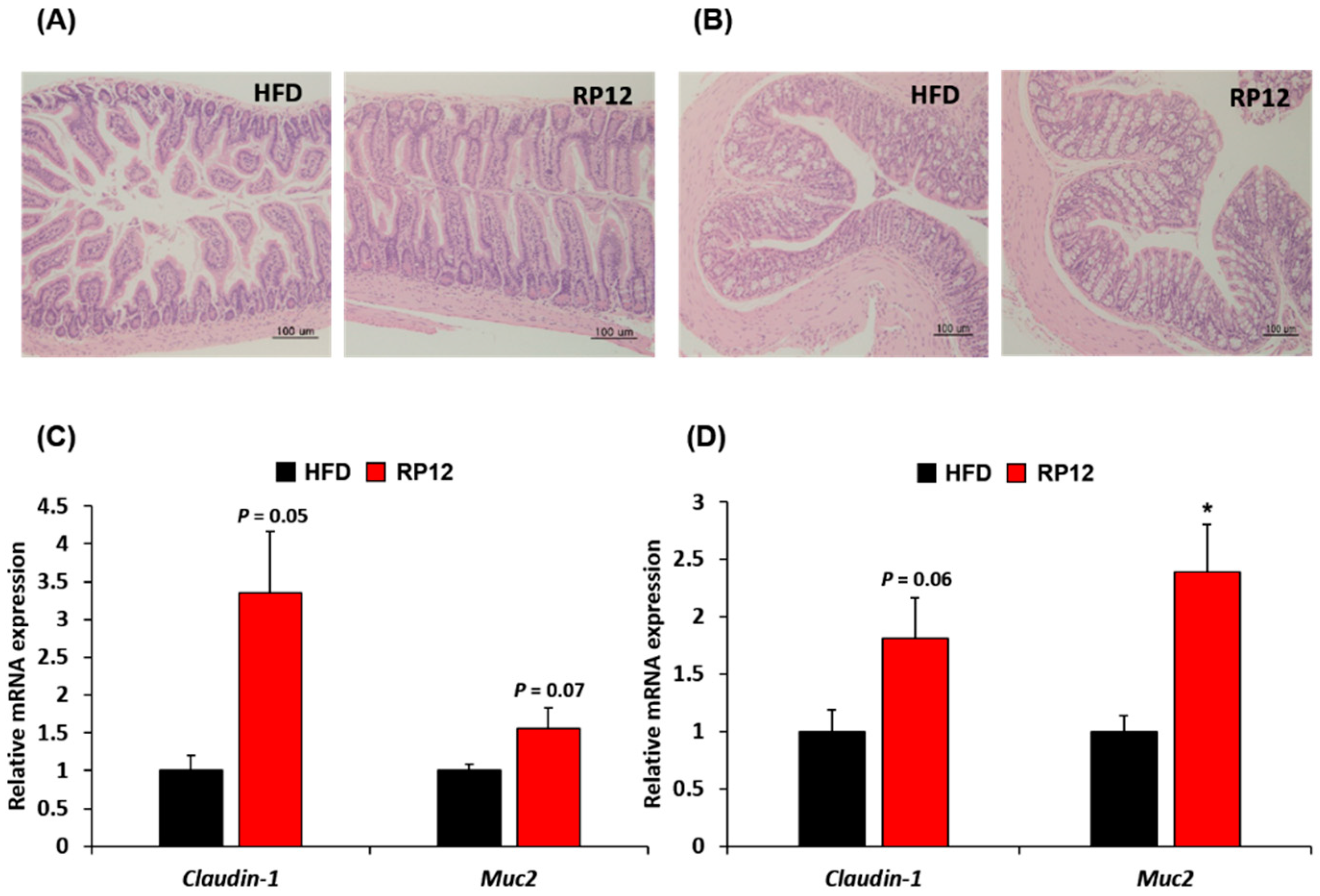

3.7. Histological Assessment of Colon and Ileum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| FER | Food efficiency ratio |

| GTT | Glucose tolerance test |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate transaminase |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| RT-PCR | Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| AUC | Area under curve |

References

- Sharma, A.M.; Padwal, R. Obesity is a sign - over-eating is a symptom: an aetiological framework for the assessment and management of obesity. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Després, J.-P.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2477–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien, M.; Poirier, P.; Lemieux, I.; Després, J.-P. Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity to cardiovascular disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 56, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.; Stoenchev, K.; Ashrafian, H.; Teare, J. Current treatments for obesity. Clin. Med. 2019, 19, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.H.; Lingvay, I.; Deanfield, J.; et al. Long-term weight loss effects of semaglutide in obesity without diabetes in the SELECT trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2049–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science 2013, 341, 1241214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Ni, Q.; Sun, W.; Li, L.; Feng, X. The links between gut microbiota and obesity and obesity related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Tsilingiris, D.; Panagopoulos, F.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. The role of next- generation probiotics in obesity and obesity-associated disorders: current knowledge and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagapudi, V.R.; Hezaveh, R.; Reigstad, C.S.; Gopalacharyulu, P.; Yetukuri, L.; Islam, S.; Felin, J.; Perkins, R.; Borén, J.; Orešič, M.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota modulates host energy and lipid metabolism in mice. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.-M.; Seo, M.J.; Kwon, M.J.; Park, K.W.; Yoon, J.-H. Oral administration of Latilactobacillus sakei ADM14 improves lipid metabolism and fecal microbiota profile associated with metabolic dysfunction in a high-fat diet mouse model. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 746601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lloyd, J.; Walter, P.; Rane, S.G. Beneficial metabolic effects of a probiotic via butyrate-induced GLP-1 hormone secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25088–25097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Sánchez, M.C.; Virto, L.; Llama-Palacios, A.; Ciudad, M.J.; Collado, L. Use of probiotics in preventing and treating excess weight and obesity. A systematic review. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2024, 10, E759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: An overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, I.; Setiarto, R.H.B.; Kahfi, J.; Giarni, R.; Muhamaludin; Ramadhaningtyas, D. P.; Randy, A. The mechanism of probiotics in preventing the risk of hypercholesterolemia. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2023, 11, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Feng, N.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Lactobacillus reuteri A9 and Lactobacillus mucosae A13 isolated from Chinese superlongevity people modulate lipid metabolism in a hypercholesterolemia rat model. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, fnz254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, D.; Mukherjee, R.; Aich, P. Effects of two potential probiotic Lactobacillus bacteria on adipogenesis in vitro. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, S. Probiotics and prebiotics: Present status and future perspectives on metabolic disorders. Nutrients 2016, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-R.; Kim, Y.-J.; Park, D.-Y.; Jung, U.-J.; Jeon, S.-M.; Ahn, Y.-T.; Huh, C.-S.; McGregor, R.; Choi, M.S. Probiotics L. plantarum and L. curvatus in combination alter hepatic lipid metabolism and suppress diet-induced obesity. Obesity 2013, 21, 2571–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Janghu, S.; Virkar, K.; Gat, Y.; Kumar, V.; Chhikara, N. Potential non-dairy probiotic products - A healthy approach. Food Biosci. 2018, 21, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.J.; Won, S.-M.; Kwon, M.J.; Song, J.H.; Lee, E.B.; Cho, J.H.; Park, K.W.; Yoon, J.-H. Screening of lactic acid bacteria with anti adipogenic efect and potential probiotic properties from grains. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Li, D.; Gou, K. Overexpression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 results in an increase of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and n-7 fatty acids in 293 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 398, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.-S.; Kim, J.-B. ; Yoon, T,-J.; Park, C.-H.; Rayner, D.V.; Trayhurn, P. Induction of pncoupling protein-2 (UCP2) gene expression on the differentiation of rat preadipocytes to adipocytes in primary culture. Mol. Cell. 1999, 9, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, M.; Weigert, J.; Schäffler, A.; Weiss, T.S.; Schmidl, C.; Büttner, R.; Bollheimer, C.; Aslanidis, C.; Schölmerich, J.; Buechler, C. Aldehyde oxidase 1 is highly abundant in hepatic steatosis and is downregulated by adiponectin and fenofibric acid in hepatocytes in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 350, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongol, B; Shah, Y. ; Kim, I.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Hunt, M.C. The acyl-CoA thioesterase I is regulated by PPARα and HNF4α via a distal response element in the promoter. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozaki, A.; Bai, X.; Shen-Tu, G.; Moodley, S.; Takeshita, H.; Fung, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Keshavjee, S.; Liu, M. Claudin 1 mediates TNFα-induced gene expression and cell migration in human lung carcinoma cells. PloS One 2012, 31, e38049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, K.; Gray, T.E.; Yoon, J.H.; Nettesheim, P. Quantitation of mucin RNA by PCR reveals induction of both MUC2 and MUC5AC mRNA levels by retinoids. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, L1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadrosh, D.W.; Ma, B.; Gajer, P.; Sengamalay, N.; Ott, S.; Brotman, R.M.; Ravel, J. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.-M.; Chen, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, K.E.; Park, K.W.; Yoon, J.-H. Lactobacillus sakei ADM14 induces anti-obesity effects and changes in gut microbiome in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, D.; Yang, Q.; Kahn, B.B. Lipid extraction from mouse feces. Bio Protoc. 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, L.; Yang, G.; Zhang, A.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Lian, L.; Pan, D.; Wu, Z. Anti-inflammation and gut microbiota regulation properties of fatty acids derived from fermented milk in mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7865–7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessesen, D.H.; Van Gaal, L.F. Progress and challenges in anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadooka, Y.; Sato, M.; Imaizumi, K.; Ogawa, A.; Ikuyama, K.; Akai, Y.; Okano, M.; Kagoshima, M.; Tsuchida, T. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Delzenne, N.M. The role of the gut microbiota in energy metabolism and metabolic disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Kaser, A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2126–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.-L.; Zhang, L.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Yin, B.-C.; Ye, B.-C.; Zhou, Y. Advances in the role and mechanism of lactic acid bacteria in treating obesity. Food Bioeng. 2022, 1, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.-M.; Chen, S.; Park, K.W.; Yoon, J.-H. Isolation of lactic acid bacteria from kimchi and screening of Lactobacillus sakei ADM14 with anti-adipogenic effect and potential probiotic properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 126, 109296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Shen, C.J.; Jia, G.; Wang, K.N. Effect of dietary Bacillus subtilis on proportion of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes in swine intestine and lipid metabolism. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 1766–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Park, K.-Y.; Ji, Y.; Park, S.; Holzapfel, W.; Hyun, C.-K. Protective effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG against dyslipidemia in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, G.-M.; Oh, H.Y.; Kwon, E.; Cho, Y.; Shin, S.; Park, H.; Jeon, S.; Kim, E.; Hur, C.; Park, T.; Sung, M.; McGregor, R.A.; Choi, M. Long-term adaptation of global transcription and metabolism in the liver of high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, S173–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.I.A.; Gibson, G.R. Effects of consumption of probiotics and prebiotics on serum lipid levels in humans. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 259-281 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Menghebilige; Bao, Q. Selection of potential probiotic lactobacilli for cholesterol-lowering properties and their effect on cholesterol metabolism in rats fed a high-lipid diet. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, N.; Xi, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Zhang, B.; Bai, X. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum MA2 isolated from Tibet kefir on lipid metabolism and intestinal microflora of rats fed on high-cholesterol diet. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérard, P.; Béguet, F.; Lepercq, P.; Rigottier-Gois, L.; Rochet, V.; Andrieux, C.; Juste, C. Gnotobiotic rats harboring human intestinal microbiota as a model for studying cholesterol-to-coprostanol conversion. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, A.N.; Chassard, C.; Lacroix, C. Gut microbial adaptation to dietary consumption of fructose, artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols: Implications for host-microbe interactions contributing to obesity. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, C.X.; Min, L.; Zhu, L.Y. Good or bad: Gut bacteria in human health and diseases. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018, 32, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, N.; Osaka, T.; Haruta, I.; Ueshiba, H.; Yanagisawa, N.; Omori-Miyake, M.; Hashimoto, E.; Shibata, N.; Tokushige, K.; Saito, K.; Tsuneda, S.; Yagi, J. Effect of lipopolysaccharide on the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high caloric diet-fed mice. Scand. J. Immunol. 2016, 83, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.D.; Atay, Ç.; Heringer, J.; Romrig, F.K.; Schwitalla, S.; Aydin, B.; Ziegler, P.K.; Varga, J.; Reindl, W.; Pommerenke, C.; Salinas-Riester, G.; Böck, A.; Alpert, C.; Blaut, M.; Polson, S.C.; Brandl, L.; Kirchner, T.; Greten, F.R.; Polson, S.W.; Arkan, M.C. High-fat-diet-mediated dysbiosis promotes intestinal carcinogenesis independently of obesity. Nature 2014, 514, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Ishaq, S.L.; Zhao, F.-Q.; Wright, A.-D.G. Colonic inflammation accompanies an increase of β-catenin signaling and Lachnospiraceae/Streptococcaceae bacteria in the hind gut of high-fat diet-fed mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 35, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, D.; Zhou, W.; Peng, Y.; Chen, C.; Shen, W.; Zeng, X.; Yuan, Q. Improvement of metabolic syndrome in high-fat diet-induced mice by yeast β-glucan is linked to inhibited proliferation of Lactobacillus and Lactococcus in gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7581–7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Chen, X.; Chu, X.; Fan, M.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Yang, X.; Yuan, J.; Zha, L.; Zhao, B.; Yang, C.-X.; Qi, X.-R.; Ning, K.; Debelius, J.; Ye, W.; Xiong, B.; Pan, X.-F.; Pan, A. Association of gut microbiota during early pregnancy with risk of incident gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4128–e4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Lu, L.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Chen, X. Gut microbiota and sunitinib-induced diarrhea in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 8663–8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Lv, L.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Shi, D.; Fang, D.; Guo, F.; Jiang, H.; Yan, R.; Ye, W.; Li, L. Butyrate protects mice against methionine-choline-deficient diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by improving gut barrier function, attenuating inflammation and reducing endotoxin levels. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-H.; Yun, K.E.; Kim, J.; Park, E.; Chang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Kim, H.-L.; Kim, H.-N. Gut microbiota and metabolic health among overweight and obese individuals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evgenia, N.; Natalia, B.; Anna, P.; Anastasia, R.; Tatyana, B.; Lyubov, R. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of adolescents with obesity. Cogn. Sci. Genome Bioinform. 2020, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.C.; Wang, Z.; Usyk, M.; et al. Gut microbiome composition in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos is shaped by geographic relocation, environmental factors, and obesity. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, W.; Li, B.; Qian, S.; Wei, B.; Gong, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Wei, M. Nuciferine modulates the gut microbiota and prevents obesity in high-fat diet-fed rats. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1959–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therdtatha, P.; Song, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Mariyatun, M.; Almunifah, M.; Manurung, N.E.P.; Indriarsih, S.; Lu, Y.; Nagata, K.; Fukami, K.; Ikeda, T.; Lee, Y.-K.; Rahayu, E.S.; Nakayama, J. Gut microbiome of indonesian adults associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study in an Asian city, Yogyakarta. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, D.; He, Y.; et al. Discrepant gut microbiota markers for the classification of obesity-related metabolic abnormalities. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Merendino, N.; Costantini, L. Polyphenols as modulators of pre-established gut microbiota dysbiosis: State-of-the-art. BioFactors 2022, 48, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, Q.; Zheng, W.; Steinwandel, M.; Blot, W.J.; Shu, X.-O.; Long, J. Oral microbiome and obesity in a large study of low-income and African-American populations. J. Oral Microbiol. 2019, 11, 1650597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Gao, R.; Yan, X.; Huang, L.; Qin, H. Probiotics improve gut microbiota dysbiosis in obese mice fed a high-fat or high-sucrose diet. Nutrition 2019, 60, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zou, G.; Li, B.; Du, X.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, X. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) alleviates experimental colitis in mice by gut microbiota regulation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Ko, G. Effect of metformin on metabolic improvement and gut microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5935–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, C.; Sugimoto, K.; Moritani, I.; Tanaka, J.; Oya, Y.; Inoue, H.; Tameda, M.; Shiraki, K.; Ito, M.; Takei, Y.; Takase, K. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Song, J.; Zaytseva, Y.; et al. An obligatory role for neurotensin in high-fat-diet-induced obesity. Nature 2016, 533, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; van der Veeken, J.; deRoos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J.; Rudensky, A.Y. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 504, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Chang, X.; Qi, K. Short chain fatty acids prevent high-fat-diet-induced obesity in mice by regulating G protein-coupled receptors and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, K.E.B. Microbial degradation of whole-grain complex carbohydrates and impact on short-chain fatty acids and health. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, A.L.; Ahern, P.P.; Griffin, N.W.; Goodman, A.L.; Gordon, J.I. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 474, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni Canani, R.; Sangwan, N.; Stefka, A.T.; Nocerino, R.; Paparo, L.; Aitoro, R.; Calignano, A.; Khan, A.A.; Gilbert, J.A.; Nagler, C.R. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-supplemented formula expands butyrate-producing bacterial strains in food allergic infants. ISME J. 2016, 10, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; Bleeker, A.; Gerding, A.; van Eunen, K.; Havinga, R.; van Dijk, T.H.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Jonker, J.W.; Groen, A.K.; Reijngoud, D.-J.; Bakker, B.M. Short-chain fatty acids protect against high-fat diet-induced obesity via a PPARγ-dependent switch from lipogenesis to fat oxidation. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2398–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Yin, J.; Zhang, J.; Ward, R.E.; Martin, R.J.; Lefevre, M.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ye, J. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes 2009, 58, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.V.; Frassetto, A.; Kowalik Jr, E.J.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Lu, M.M.; Kosinski, J.R.; Hubert, J.A.; Szeto, D.; Yao, X.; Forrest, G.; Marsh, D.J. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, H.J.; Duncan, S.H.; Scott, K.P.; Louis, P. Links between diet, gut microbiota composition and gut metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, T.F.; Collado, M.C.; Ferreira, C.L.; Bressan, J.; Peluzio Mdo. C. Potential mechanisms for the emerging link between obesity and increased intestinal permeability. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, M.B.; Konkin, T.; Routhier, J.; Sabo, E.; Pricolo, V.E. Claudin-1 is a strong prognostic indicator in stage II colonic cancer: a tissue microarray study. Mod. Pathol. 2005, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-P.; Lai, M.-D.; Lee, J.-C.; Yen, M.-C.; Weng, T.-Y.; Chen, W.-C.; Fang, J.-H.; Chen, Y.-L. Mucin 2 silencing promotes colon cancer metastasis through interleukin-6 signaling. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Yokoyama, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Benegiamo, G.; Hirayama, A.; Zhu, Q.; Kitamura, N.; Sugizaki, T.; Morimoto, K.; Itoh, H.; Fukuda, S.; Auwerx, J.; Tsubota, K.; Watanabe, M. Asperuloside improves obesity and type 2 diabetes through modulation of gut mcrobiota and metabolic signaling. iScience 2020, 23, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HFD | RP12 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 151.43 ± 10.51 | 139.40 ± 10.78* |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 196.29 ± 15.60 | 125.80 ± 13.34* |

| TG (mg/dl) | 69.29 ± 6.19 | 61.40 ± 2.22 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 95.43 ± 2.89 | 98.20 ± 2.22 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 22.71 ± 1.81 | 18.80 ± 0.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).