Submitted:

08 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

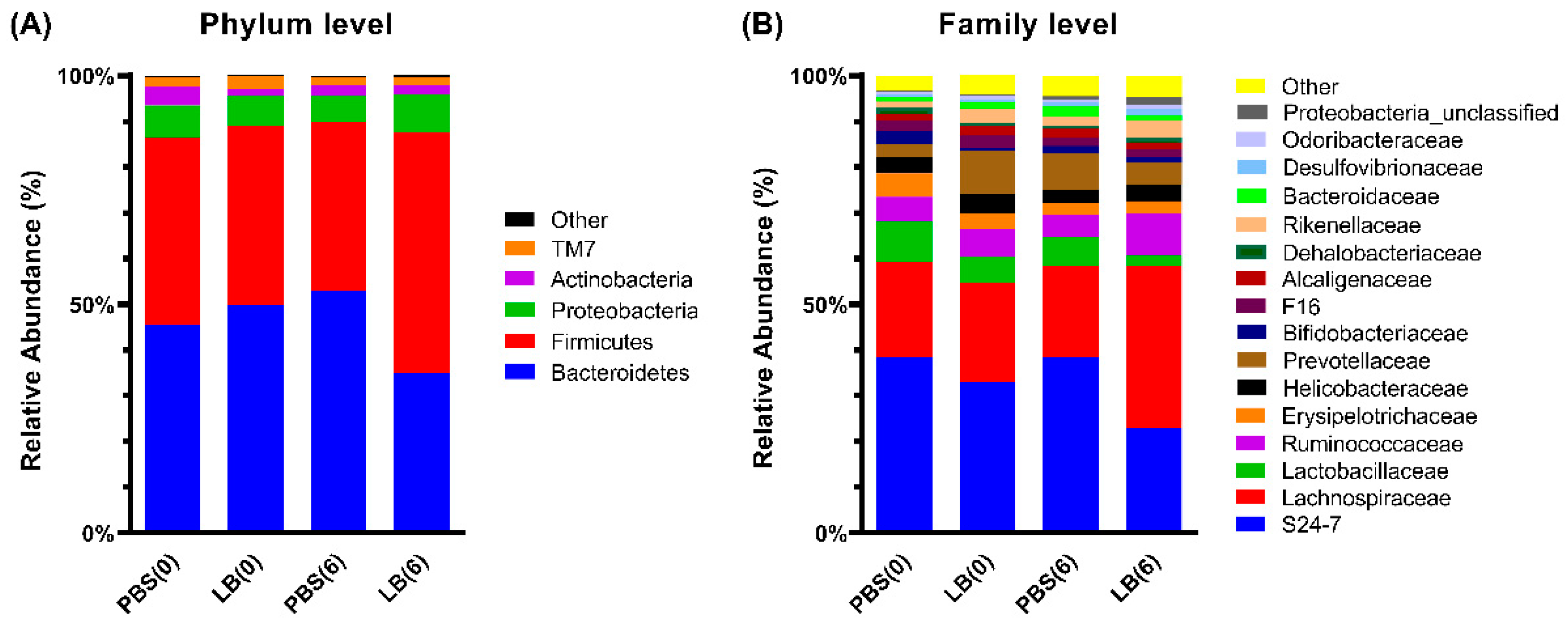

Over the past decade, probiotics have gained increasing recognition for their health benefits to the host. While most research has focused on the therapeutic effects of probiotics in the treatment of various diseases, recent years have seen a shift towards exploring their role in enhancing and supporting overall health. In this work, we have studied the effects of a novel potential probiotic strain, Lactiplantibacillus pentosus PE11, in healthy mice following a six-week dietary intervention. The assessment included monitoring the general health of the animals, biochemical analyses, profiling of the gut and fecal microbial communities and gene expression analysis. Our results showed that the administration of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus PE11 led to significant changes in the composition of the fecal microbiome, specifically an increase in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and in the relative abundance of the Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae and Rikenellaceae families. Additionally, a significant reduction in triglyceride and alanine aminotransferase levels was observed, along with a trend toward decreased total cholesterol levels. Our results suggest that in healthy mice Lactiplantibacillus pentosus PE11 has the potential to positively influence gut microbiome structure and metabolism, thereby supporting improved overall health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Bacterial Cultures

2.2. Animals

2.3. Serum Biochemical Analyses

2.4. Histology

2.5. Gene Expression Analysis

2.6. Analysis of the Microbial Communities

2.6.1. DNA Extraction

2.6.2. Amplicon-Based Next Generation Sequencing

2.6.3. Data Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1.Β. Ody Weight

3.2. Histological Analysis

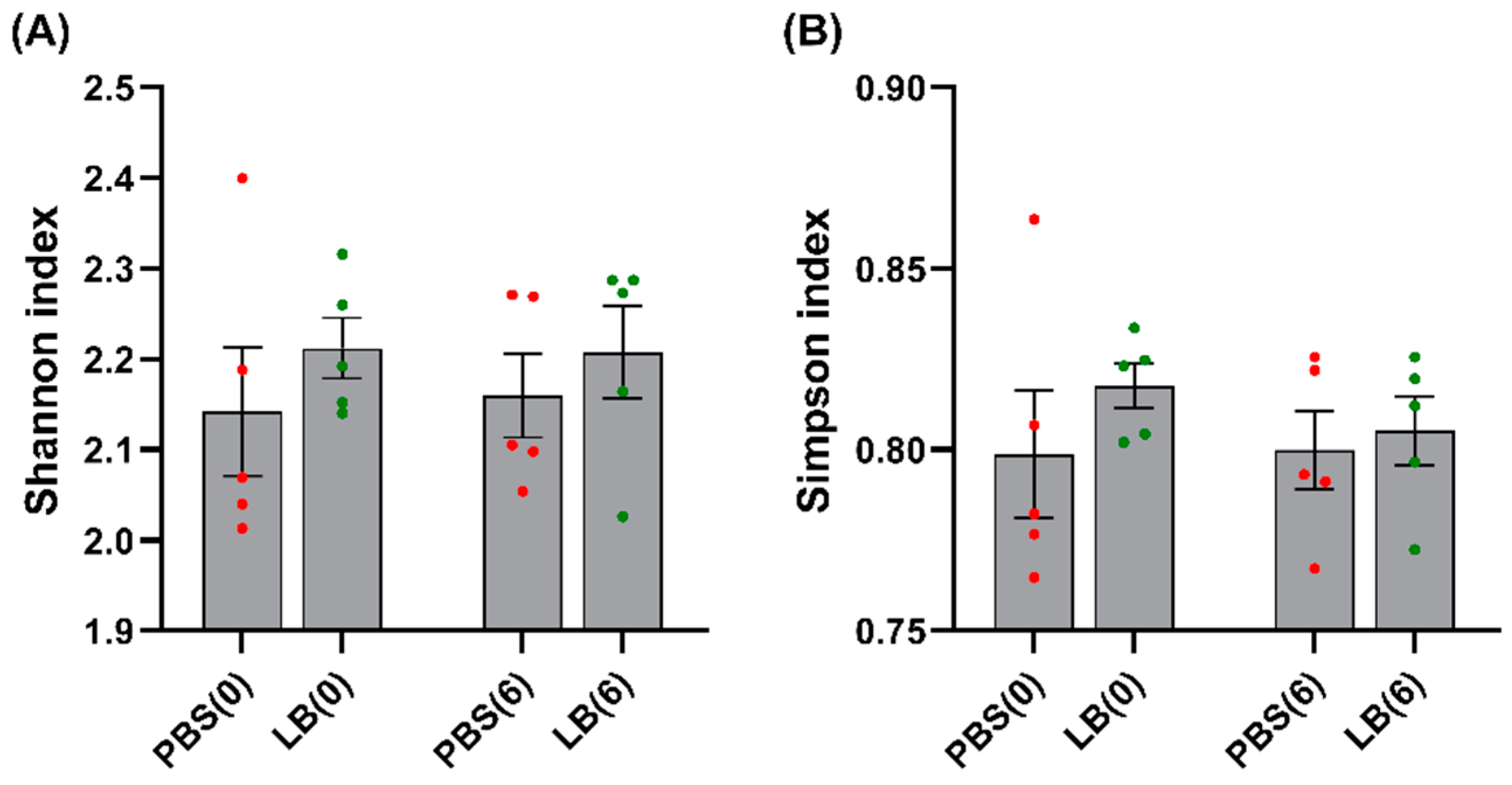

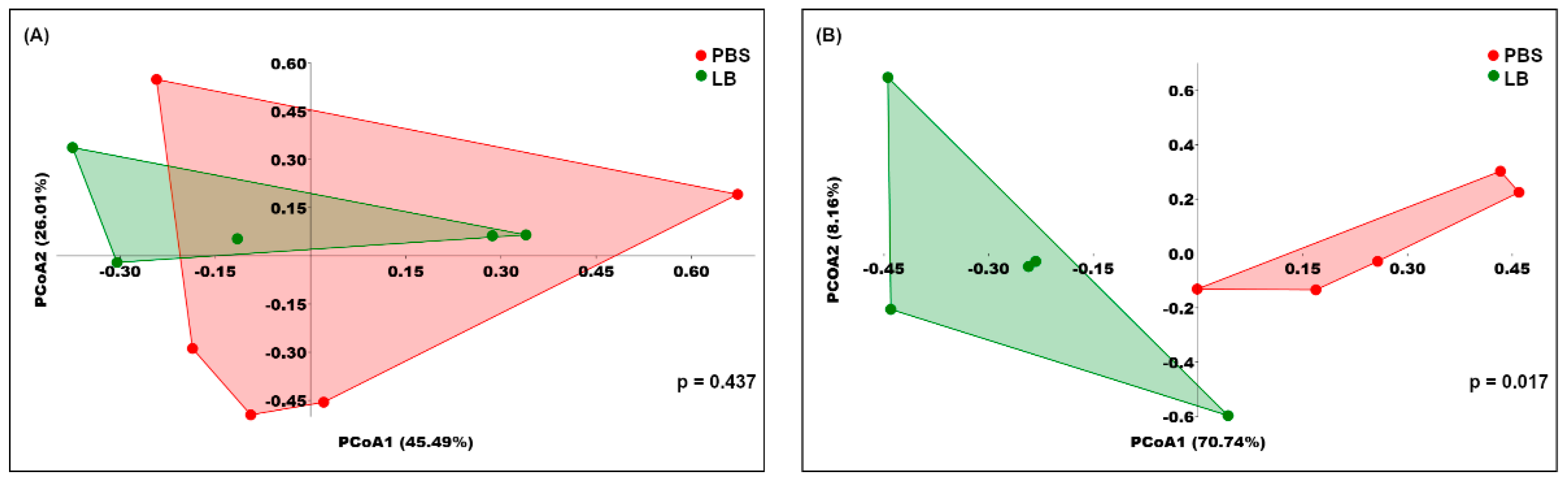

3.3. Analysis of the Fecal Microbial Community

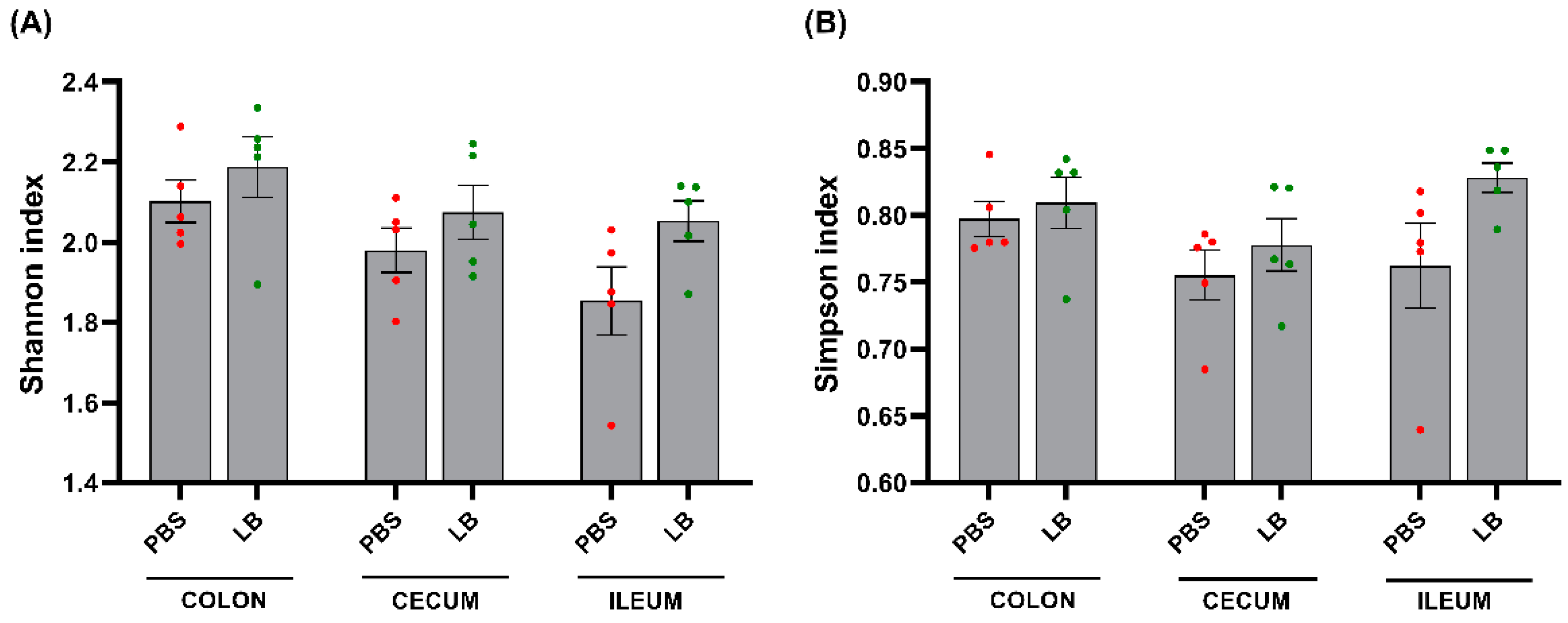

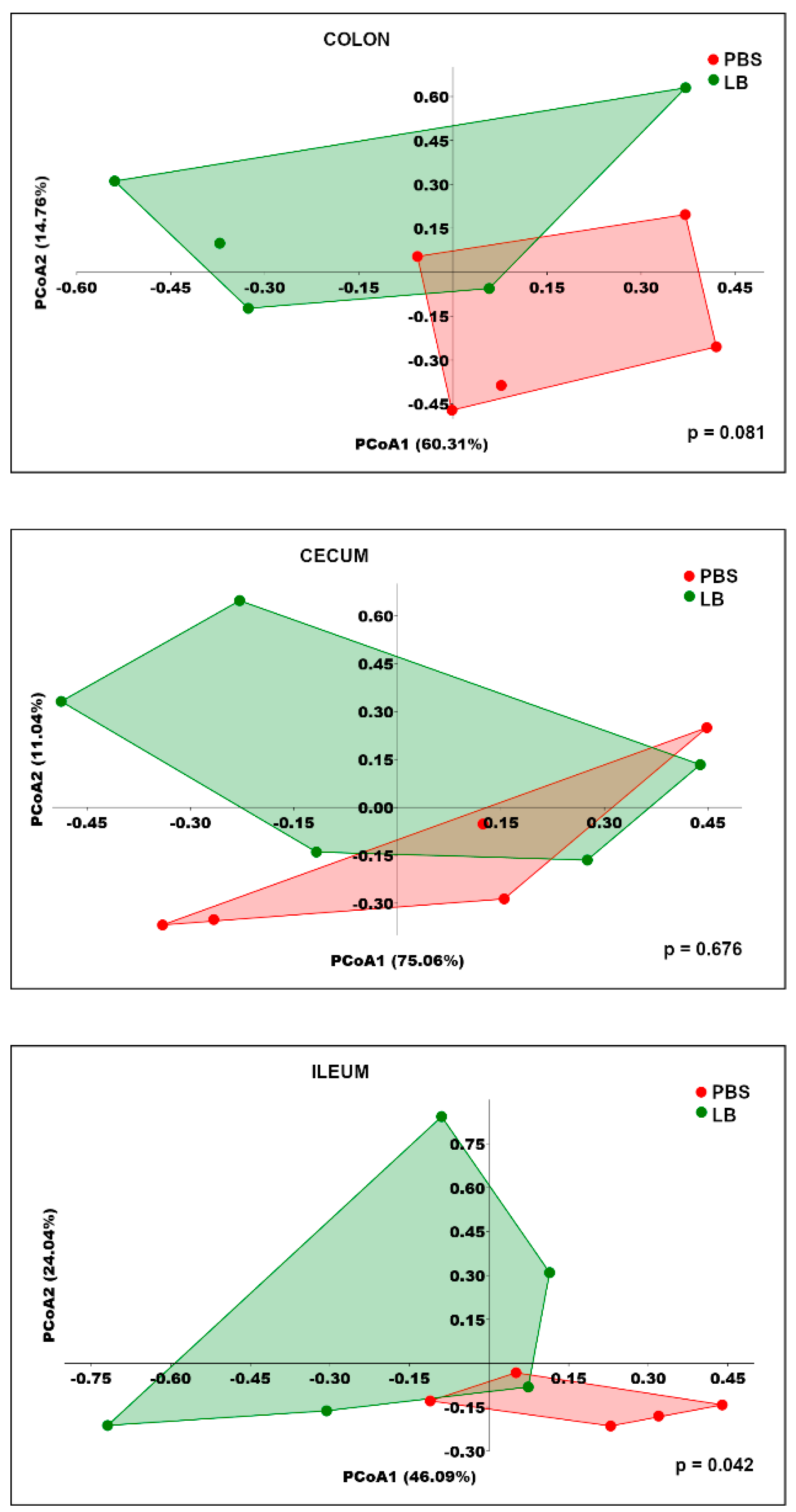

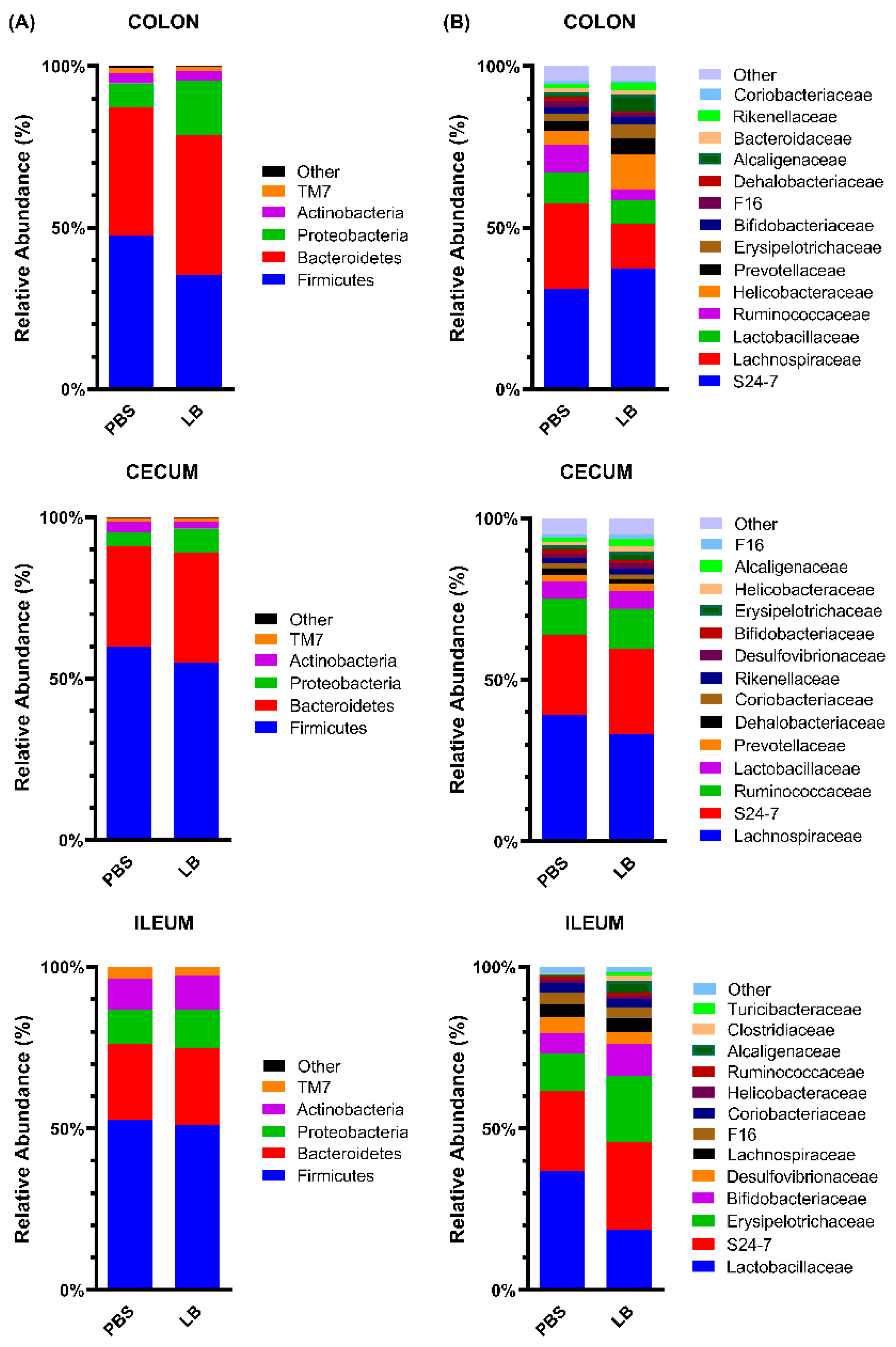

3.4. Analysis of the GI Microbial Communities

3.5. Serum Biochemical Parameters

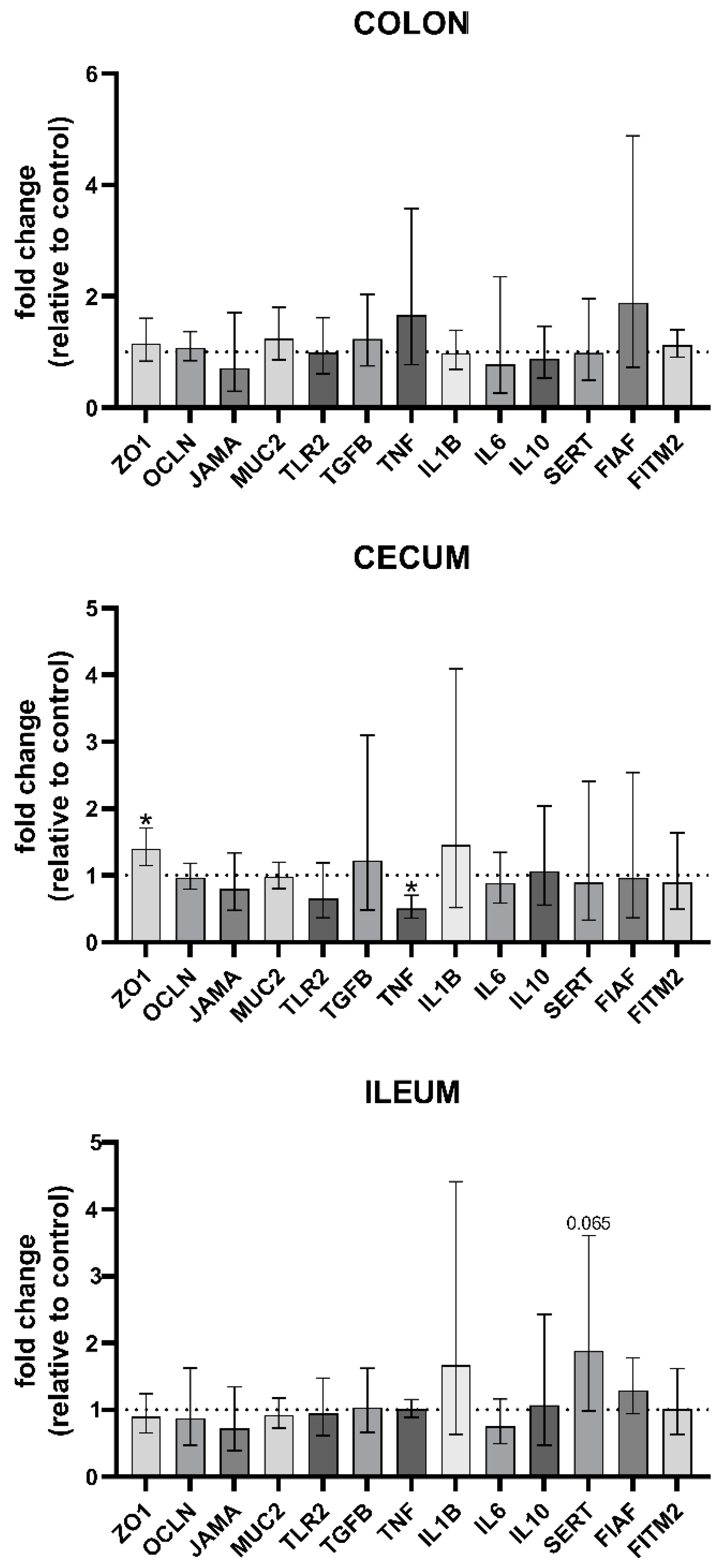

3.6. Gene Expression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maciel-Fiuza, M.F.; Muller, G.C.; Campos, D.M.S.; do Socorro Silva Costa, P.; Peruzzo, J.; Bonamigo, R.R.; Veit, T.; Vianna, F.S.L. Role of Gut Microbiota in Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1098386. [CrossRef]

- Maftei, N.-M.; Raileanu, C.R.; Balta, A.A.; Ambrose, L.; Boev, M.; Marin, D.B.; Lisa, E.L. The Potential Impact of Probiotics on Human Health: An Update on Their Health-Promoting Properties. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 234. [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, W.; Schink, M.; Zopf, Y. Microbiota in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 116. [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. Role of the Normal Gut Microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Asha; Sharma, K.K. Gut–Organ Axis: A Microbial Outreach and Networking. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 72, 636–668. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L. Role and Mechanism of Gut Microbiota in Human Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease: Unveiling the Relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [CrossRef]

- Rau, S.; Gregg, A.; Yaceczko, S.; Limketkai, B. Prebiotics and Probiotics for Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16, 778. [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Shehzad, A.; Niazi, S.; Zahid, A.; Ashraf, W.; Iqbal, M.W.; Rehman, A.; Riaz, T.; Aadil, R.M.; Khan, I.M.; et al. Probiotics: Mechanism of Action, Health Benefits and Their Application in Food Industries. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1216674. [CrossRef]

- Merenstein, D.J.; Tancredi, D.J.; Karl, J.P.; Krist, A.H.; Lenoir-Wijnkoop, I.; Reid, G.; Roos, S.; Szajewska, H.; Sanders, M.E. Is There Evidence to Support Probiotic Use for Healthy People? Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100265. [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V.; Evans, C.T.; Goldstein, E.J.C. Strain-Specificity and Disease-Specificity of Probiotic Efficacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 124. [CrossRef]

- Piquer-Esteban, S.; Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Arnau, V.; Diaz, W.; Moya, A. Exploring the Universal Healthy Human Gut Microbiota around the World. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 20, 421–433. [CrossRef]

- Somalou, P.; Ieronymaki, E.; Feidaki, K.; Prapa, I.; Stylianopoulou, E.; Spyridopoulou, K.; Skavdis, G.; Grigoriou, M.E.; Panas, P.; Argiriou, A.; et al. Novel Wild-Type Pediococcus and Lactiplantibacillus Strains as Probiotic Candidates to Manage Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 231. [CrossRef]

- Ramakers, C.; Ruijter, J.M.; Deprez, R.H.L.; Moorman, A.F.M. Assumption-Free Analysis of Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Data. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 339, 62–66. [CrossRef]

- Ganger, M.T.; Dietz, G.D.; Ewing, S.J. A Common Base Method for Analysis of qPCR Data and the Application of Simple Blocking in qPCR Experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 534. [CrossRef]

- Tegopoulos, K.; Tsirka, T.; Stekas, C.; Gerasimidi, E.; Skavdis, G.; Kolovos, P.; Grigoriou, M.E. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Assyrtiko Grape Microbiota. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 577. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing Mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Ewald, J.; Pang, Z.; Shiri, T.; Xia, J. MicrobiomeAnalyst 2.0: Comprehensive Statistical, Functional and Integrative Analysis of Microbiome Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W310–W318. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, O.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis.

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [CrossRef]

- Zaplana, T.; Miele, S.; Tolonen, A.C. Lachnospiraceae Are Emerging Industrial Biocatalysts and Biotherapeutics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 1324396. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xu, C.; Kan, S.; Chen, D. Disturbances of the Gut Microbiota and Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5140. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Davis, B.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, N.; Meng, D.; Walker, W.A. Epithelial Biology and Secretion: Short-Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate, a Breast Milk Metabolite, Enhances Immature Intestinal Barrier Function Genes in Response to Inflammation in Vitro and in Vivo. Am. J. Physiol. - Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021, 320, G521. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lv, L.; Zheng, B.; Yan, R.; Jiang, H.; Shen, J.; Wang, S.; et al. The Impact of Dietary Fibers on Clostridioides Difficile Infection in a Mouse Model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1028267. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.; Taminiau, B.; Rodriguez, C.; Daube, G. Gut Microbiota Composition Associated with Clostridioides Difficile Colonization and Infection. Pathogens 2022, 11, 781. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.; Donde, H.; Ghare, S.; Stocke, K.; Zhang, J.; Vadhanam, M.; Reddy, S.; Gobejishvili, L.; Chilton, P.; Joshi-Barve, S.; et al. Decrease in Acetyl-CoA Pathway Utilizing Butyrate-Producing Bacteria Is a Key Pathogenic Feature of Alcohol-Induced Functional Gut Microbial Dysbiosis and Development of Liver Disease in Mice. Gut Microbes 13, 1946367. [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; He, X.; Chen, H.; He, Q.; Yao, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Simpson, S. Oil Tea Improves Glucose and Lipid Levels and Alters Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Nutr. Res. N. Y. N 2018, 57, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Koontanatechanon, A.; Wongphatcharachai, M.; Nonthabenjawan, N.; Jariyahatthakij, P.; Khorporn, T.; Parnsen, W.; Keattisin, B.; Leksrisompong, P.; Srichana, P.; Prasopdee, S.; et al. Effects of Omega-3-Rich Pork Lard on Serum Lipid Profile and Gut Microbiome in C57BL/6NJ Mice. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 9269968. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Siddiqui, W.J. Cholesterol Levels. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Karanchi, H.; Muppidi, V.; Wyne, K. Hypertriglyceridemia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Lim, P.S.; Loke, C.F.; Ho, Y.W.; Tan, H.Y. Cholesterol Homeostasis Associated with Probiotic Supplementation in Vivo. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1374–1388. [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Cui, Y.; Yin, Y.-N.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J.-W.; Wang, Z.-G.; Fu, N.; Tang, Y.; Wang, X.-H.; Liu, X.-W.; et al. Effects of Two Lactobacillus Strains on Lipid Metabolism and Intestinal Microflora in Rats Fed a High-Cholesterol Diet. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 53. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, F.; Sui, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z. Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains as Potential Probiotic Cultures with Cholesterol-Lowering Activity. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2746–2753. [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.J.; Yu, H.; Kim, J.I.; Seo, H.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, S.-K.; Lee, H.S.; Cheon, H.G. Anti-Obesity Effects of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum SKO-001 in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1611–1622. [CrossRef]

- Damodharan, K.; Lee, Y.S.; Palaniyandi, S.A.; Yang, S.H.; Suh, J.-W. Preliminary Probiotic and Technological Characterization of Pediococcus Pentosaceus Strain KID7 and in Vivo Assessment of Its Cholesterol-Lowering Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 768. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Hemeda, S.A.; Albadrani, G.M.; Fadl, S.E.; Elgendey, F. Ameliorating Effect of Probiotic on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Lipolytic Gene Expression in Rabbits. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6312. [CrossRef]

- Melia, S.; Juliyarsi, I.; Kurnia, Y.F.; Aritonang, S.N.; Purwati, E.; Sukma, A.; Fitria, N.; Susmiati, S.; Meinapuri, M.; Pratama, Y.E.; et al. Effect of Fermented Milk Pediococcus Acidilactici BK01 on Cholesterol and Microbiota in Wistar Mice Intestine. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2023, 10, 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Moriles, K.E.; Zubair, M.; Azer, S.A. Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) Test. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Kim, S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.; Seo, Y.; Lee, H.; Ha, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Oh, H.; Yoon, Y. Akkermansia Muciniphila Prevents Fatty Liver Disease, Decreases Serum Triglycerides, and Maintains Gut Homeostasis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e03004-19. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Yan, J.; Wu, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Z.; He, B. Probiotics Alleviated Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats via Gut Microbiota/FXR/FGF15 Signaling Pathway. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 2264737. [CrossRef]

- Al-muzafar, H.M.; Amin, K.A. Probiotic Mixture Improves Fatty Liver Disease by Virtue of Its Action on Lipid Profiles, Leptin, and Inflammatory Biomarkers. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 43. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G. Probiotic Bifidobacterium Lactis V9 Attenuates Hepatic Steatosis and Inflammation in Rats with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. AMB Express 2020, 10, 101. [CrossRef]

- Bellés, A.; Abad, I.; Sánchez, L.; Grasa, L. Whey and Buttermilk-Based Formulas Modulate Gut Microbiota in Mice with Antibiotic-Induced Dysbiosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, e2300248. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhai, S.; Qin, S.; Du, Z. Effects of Phycocyanin in Modulating the Intestinal Microbiota of Mice. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e00825. [CrossRef]

- Lkhagva, E.; Chung, H.-J.; Hong, J.; Tang, W.H.W.; Lee, S.-I.; Hong, S.-T.; Lee, S. The Regional Diversity of Gut Microbiome along the GI Tract of Male C57BL/6 Mice. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 44. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.-S.; Lkhagva, E.; Jung, S.; Kim, H.-J.; Chung, H.-J.; Hong, S.-T. Fecal Microbiome Does Not Represent Whole Gut Microbiome. Cell. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 6868417. [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chen, D.; Zhang, J.-N.; Lv, X.; Wang, K.; Duan, L.-P.; Nie, Y.; Wu, X.-L. Bacterial Community Mapping of the Mouse Gastrointestinal Tract. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e74957. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadi, R.; Guo, S.; Ye, D.; Rawat, M.; Ma, T.Y. TNF-α Modulation of Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability Is Mediated by NIK/IKK-α Axis Activation of the Canonical NF-κB Pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 1151–1165. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jian, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, S.; Niu, Y.; Xie, S.; Hayer, K.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. Alleviation of DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice by a New-Isolated Lactobacillus Acidophilus C4. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ji, Y.; Jung, H.-Y.; Park, H.; Kang, J.; Choi, S.-H.; Shin, H.; Hyun, C.-K.; Kim, K.-T.; Holzapfel, W.H. Lactobacillus Plantarum HAC01 Regulates Gut Microbiota and Adipose Tissue Accumulation in a Diet-Induced Obesity Murine Model. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 1605–1614. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.S.; Kim, H.N.; Park, H.J.; Lee, J.E.; Yeo, S.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Park, S.Y.; Yoon, H.S.; Cho, G.S.; Franz, C.M. a. P.; et al. Modulation of the Murine Microbiome with a Concomitant Anti-Obesity Effect by Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus Sakei NR28. Benef. Microbes 2012, 3, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Taverniti, V.; Cesari, V.; Gargari, G.; Rossi, U.; Biddau, C.; Lecchi, C.; Fiore, W.; Arioli, S.; Toschi, I.; Guglielmetti, S. Probiotics Modulate Mouse Gut Microbiota and Influence Intestinal Immune and Serotonergic Gene Expression in a Site-Specific Fashion. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 706135. [CrossRef]

- Guzel, T.; Mirowska-Guzel, D. The Role of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Gastrointestinal Tract and Pharmacotherapy. Mol. Basel Switz. 2022, 27, 1680. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, P.P.; Bertrand, R.L. Serotonin Release and Uptake in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2010, 153, 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, C.; Qin, X.; Zhou, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Xie, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Saccharomyces Boulardii, a Yeast Probiotic, Inhibits Gut Motility through Upregulating Intestinal Serotonin Transporter and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 181, 106291. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, A.; Clemente, C.; D’Attoma, B.; Russo, F. Effects of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG on the Serotonergic Pathway in a Gliadin-Induced Enteropathy Animal Model. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104077. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-J.; Jin, Y.-J.; Ganesan, R.; Park, H.J.; Min, B.H.; Jeong, M.K.; Yoon, S.J.; Choi, M.R.; Sharma, S.P.; Jang, Y.J.; et al. Multistrain Probiotics Alleviate Diarrhea by Modulating Microbiome-Derived Metabolites and Serotonin Pathway. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024. [CrossRef]

| Biochemical parameter | PBS group control |

LB group Lb. pentosus PE11 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 75 (53-145) | 33 (17-43) | 0.008 |

| ALP (U/L | 76 (60-96) | 87 (78-93) | 0.286 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 43 (39-92) | 42 (37-47) | 0.413 |

| CRE (mg/dL) | 0.31 (0.27-0.39) | 0.29 (0.28-0.31) | 0.460 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 54 (33-66) | 40 (39-57) | 0.278 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 5 (4-8) | 5 (4-6) | 0.762 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 81 (72-100) | 67 (65-94) | 0.056 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 91 (79-101) | 57 (37-67) | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).