1. Introduction

Simulation is often the only viable tool to study many-particle systems driven away from equilibrium, especially where external mechanical and thermal forces are strong. Molecular dynamics is the most natural approach, but may be computationally expensive. Since one is often interested in large-scale properties, details of microscopic interactions may not be essential, since only the basic conservation laws should matter. It is thus sensible to look for methods based on stochastic processes that may effectively account for molecular interactions. One popular approach is the Multi-Particle Collision (MPC) dynamics, a mesoscale description where individual particles undergo stochastic collisions, rather than genuine Newtonian forces. The implementation was originally proposed by Malevanets and Kapral [

1,

2] and consists of two distinct stages: a free streaming and a collision one. Collisions occur at fixed discrete time intervals, and space is discretized into cells that define the collision range. The method captures both thermal fluctuations and hydrodynamic interactions.

The MPC dynamics is a useful tool to investigate concrete systems and indeed has been used in the simulation of a variety of problems, like polymers in solution [

1], colloidal fluids [

3], plasmas and even dense stellar systems [

4] etc. Besides its computational convenience it is also a useful approach to address fundamental problems in statistical physics [

5,

6,

7,

8] and in particular the effect of external sources.

In this work, we focus on the application of the MPC method to study heat transfer in a simple fluid both at equilibrium and in the presence of external reservoirs. In particular, we analyze the dimensionality effects on thermal transport in mesoscopic and confined fluids. Energy transport in low-dimensional systems has been thoroughly studied in recent decades and is crucial for achieving an understanding of macroscopic irreversible heat transfer on the nanoscale [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Also, it serves as a theoretical foundation for thermal energy control and management [

13,

14,

15]. This is even more relevant at the nano- and microscale, where novel effects caused by reduced dimensionality, disorder, and nano-structuring affect natural and artificial materials [

16]. One remarkable property is that in low-dimensional many-particle systems, energy propagates super-diffusively, implying a breakdown of classical Fourier’s law. This has been well studied, mostly in lattice systems but much less in fluids. We will show that the MPC dynamics is particularly effective and allows for a very accurate test of existing theories of anomalous transport.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 we recall the basic definitions of the MPC dynamics and the thermal-wall method used to enforce the interaction with external heat baths. We then present results of both equilibrium and nonequilibrium for the one- (1D), two- (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) mesoscopic fluids,

Section 3 to

Section 5 respectively. In

Section 6 we illustrate how, upon changing the aspect ratio of the simulation box, one can observe crossover behavior in size dependence of the transport coefficient. In

Section 7, we briefly discuss the case 2D fluids with magnetic field to clarify that pseudomomentum conservation is not the necessary condition for the anomalous heat conduction behavior.

2. Mesoscopic Fluid and Thermal Walls

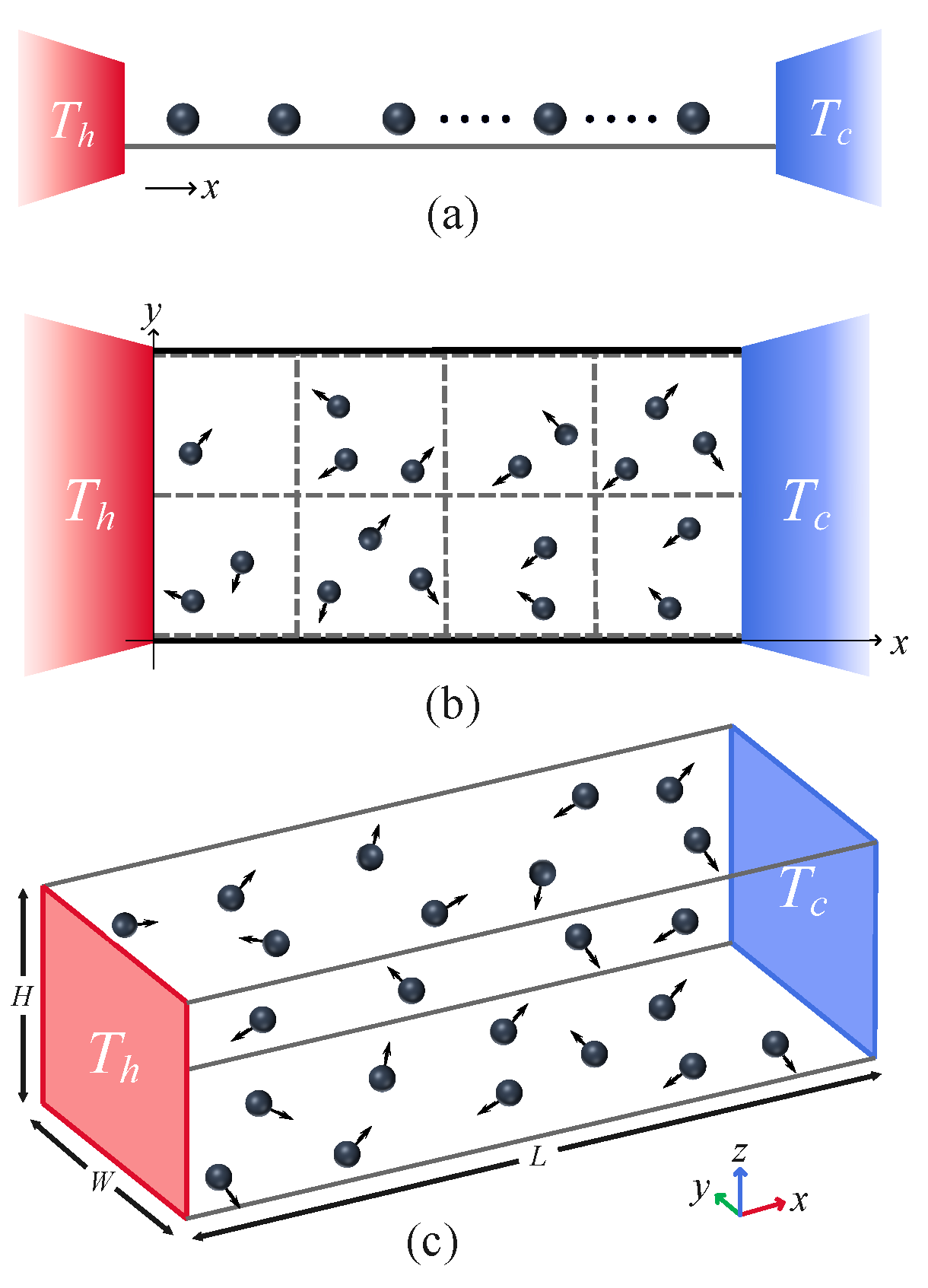

The 1D, 2D, and 3D mesoscopic fluid models we cosider in this study are shown in

Figure 1. The fluid consists of

N interacting point particles with equal mass

m, confined in a system volume. As is shown: In 1D system, its volume has a length of

L in the

x direction; in 2D system, its volume also has a width of

W in the

y direction; in 3D system, its volume has an additional height of

H in the

z direction.

At the boundaries

and

, the particles interact with a heat bath of temperature

or

; the heat baths are modeled as thermal-walls [

17,

18]. When a particle crosses the

(or

) boundary, it is reflected back with a new random velocity (

,

, and

in the

x,

y, and

z directions) assigned by sampling from a given distribution [

17,

18]:

where

(

) is the temperature of the heat bath in dimensionless units and

is the Boltzmann constant. The particles are subject to periodic boundary conditions in the

y and

z directions. We point out that the numerical results also apply to fixed boundary conditions since, in both cases,

and

with equal probability

.

Interaction among particles as prescribed by the MPC method [

1,

3,

19], amounts to first partition the simulation box into many cells of linear size

a (as is shown in

Figure 1 (b) for 2D case). The dynamics evolves in discrete time steps, each step consisting of a free propagation during a time interval

followed by an instantaneous collision event. During propagation, the velocity

of a particle is unchanged, and its position is updated as

For all particles in a given cell, their velocities are updated according to the following collision rules:

The resulting motion conserves the total momentum and energy of the fluid. Note that the angle for 2D and 3D cases corresponds to the most efficient mixing of the particle momenta. Note also that the probability of collision between particles increases as decreases. Thus the time interval can be changed to tune the strength of the interactions that, in turn, will affect the transport properties.

In the nonequilibrium setup, we set to be slightly biased from the nominal temperature T, i.e., , to investigate the dependence of the thermal conductivity on the system length L. In our simulations, each particle is initially given by a random position uniformly distribution and a random velocity generated from the Maxwellian distribution at the temperature T. After the system reaches the steady state, we compute the thermal current J that crosses the system according to its definition (i.e., the average energy exchanged in the unit time and unit area between particles and heat bath) and taking it into Fourier’s law, , to compute . We thus examine the dependence of on L, to assess whether the heat conduction behavior of the system is anomalous or normal.

In the integrable case (i.e., when

, each particle maintains unchanged velocity as it crosses the system from one heat bath to the other), we can obtain an analytical expression for the thermal conductivity:

where

d is the spatial dimension and

is the particle density. It is shown that in the integrable case, transport is ballistic and the thermal conductivity is a linear function of the system length. This analytical result will be used to compare with our simulations as a numerical verification.

In the nonequilibrium setting, the difference between normal and abnormal heat conduction behaviors can be also appreciated upon examining the steady-state kinetic temperature profiles

. In our simulations,

is measured as described in [

21]. For systems with normal heat conduction,

is determined by solving the stationary heat equation assuming that the thermal conductivity is proportional to

as prescribed by standard kinetic theory, yielding [

22]

this prediction will be used to compare with our simulation results for normal heat conduction. On the other hand, for systems with abnormal heat conduction,

is expected to be qualitatively different, being solution of a fractional diffusion equation as demonstrated in several examples [

23,

24]. A typical feature is that the temperature profile is concave upwards in part of the system and concave downwards elsewhere, and this is true even for small temperature differences [

25,

26,

27]. This will be used also to check our numerical simulations for abnormal heat conduction.

To check the results obtained in the nonequilibrium modeling, we will further turn to the comparison with linear-response results obtained in equilibrium modeling. Based on the celebrated Green-Kubo formula, which relates transport coefficients to the current time-correlation functions

, the thermal conductivity can be expressed as [

9,

10,

28]

In this formula,

and

represents the total heat current along the

x coordinate in the equilibrium state. In the simulations, we consider an isolated fluid with periodic boundary conditions also in the

x direction. The initial condition is randomly assigned with the constraints that the total momentum is zero and the total energy corresponds to

T. The system is then evolved and after the equilibrium state is attained, we compute

and the integral in Eq. (

7). Usually, the integral is truncated up to

(

is the sound speed) [

9,

10]. This results the superdiffusive heat transport

as long as

decays as

with

.

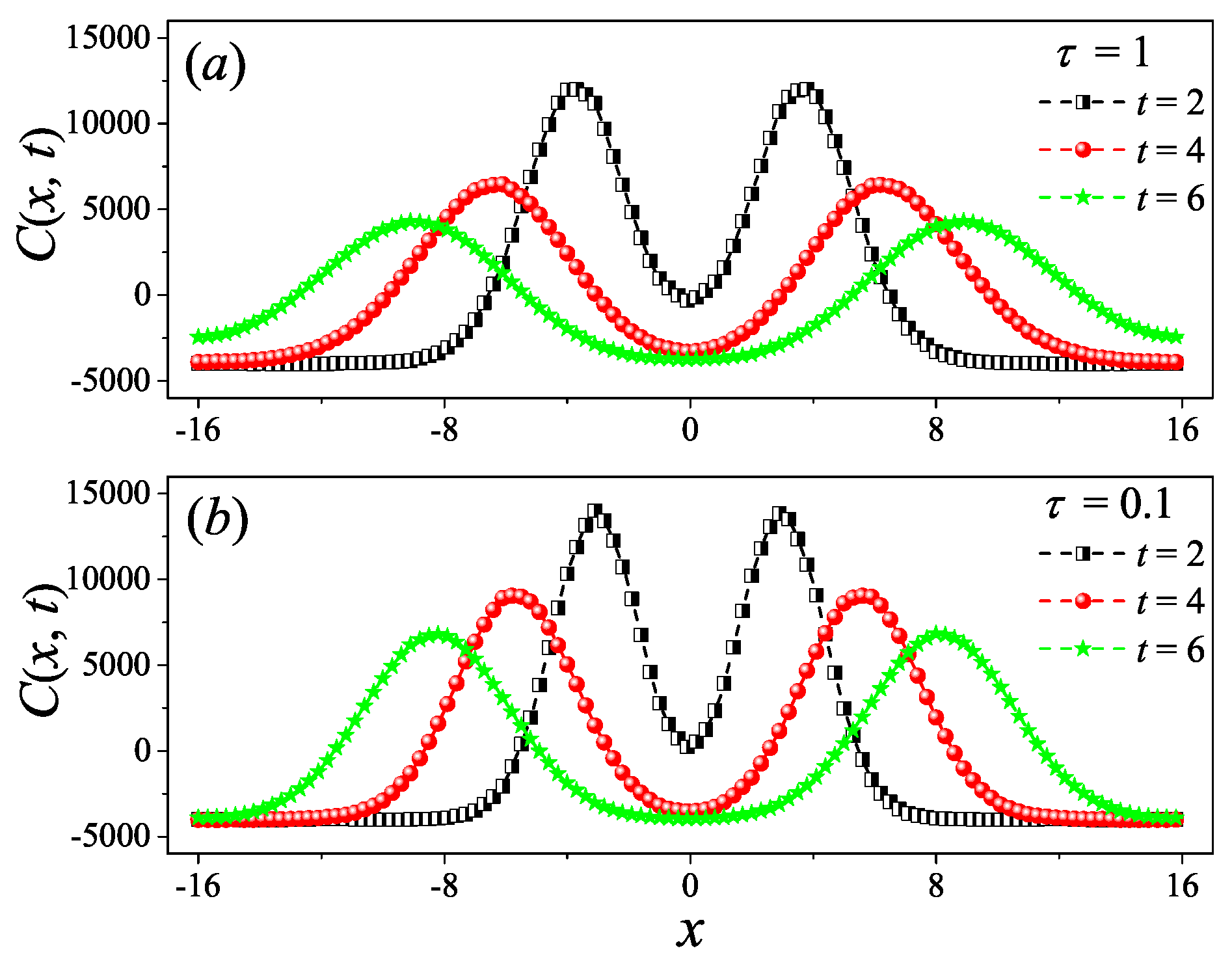

In order to compare

and

more accurately, we can resort to the spatiotemporal correlation function of local heat currents to compute the sound speed

of the system in Eq. (

7). The spatiotemporal correlation function of local heat currents is defined as [

29,

30,

31]

Numerically, we compute

as performed in [

32]: the system is divided into

bins in space of equal width

; the local heat current in the

kth bin and at time

t is defined as

, where

and the summation is taken over all particles that reside in the

kth bin. It is found that

features a pair of pulses moving oppositely away from

at the sound speed [

33,

34], which are recognized to be the hydrodynamic sound modes. Their moving speeds of the two pulses allows to estimate the sound speed

within the fluid.

As for the choice of parameters, in both nonequilibrium and equilibrium settings, we set , , , , and throughout the paper. In addition, for all data points shown in the figures, the errors are .

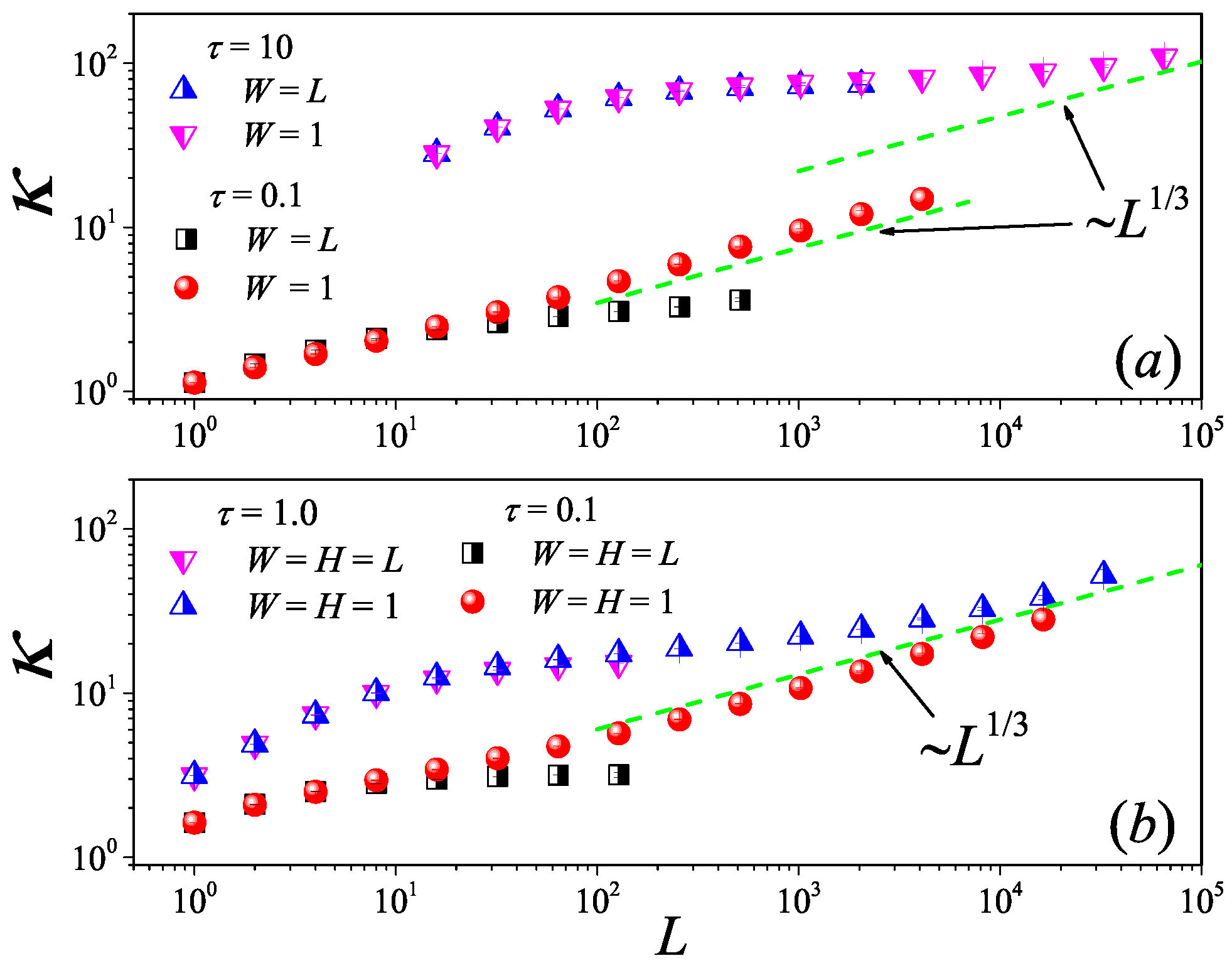

6. Dimensional Crossovers

Dimensional-crossover is a relevant topic for thermal transport in low-dimensional materials [

14]. Indeed, in 2014 it has been experimentally observed in the suspended single-layer graphene [

46]. In this experimental setup, the width of the samples is kept fixed and the thermal conductivity changes upon increasing their length is measured. As the length increases, it is natural to expect that a dimensional-crossover behavior from two dimensions to quasi-one dimension will occur. These research results have greatly enriched our understanding of heat conduction in lattice systems.

We show that the MPC approach can be used successfully to investigate this issue, considering 2D and 3D mesoscopic fluid models with fixed transverse sizes (

in 2D and

in 3D) and study how

changes with

L. It can be seen from

Figure 14 (a) that in 2D fluid models, upon increasing the aspect ratio of the system, for both

and

,

eventually follows the 1D divergence law

as

L increases. This means that both in the case where dominated by the kinetic (

) or hydrodynamic effect (

), there exists dimensional-crossover above a given aspect ratio. As is shown in

Figure 14 (b), in 3D fluid models, there is also a similar phenomenology. Altogether, these results confirm that the theories developed for the strictly 1D case effectively extend also quasi-1D, provided that the transverse extent of the sample is small enough.

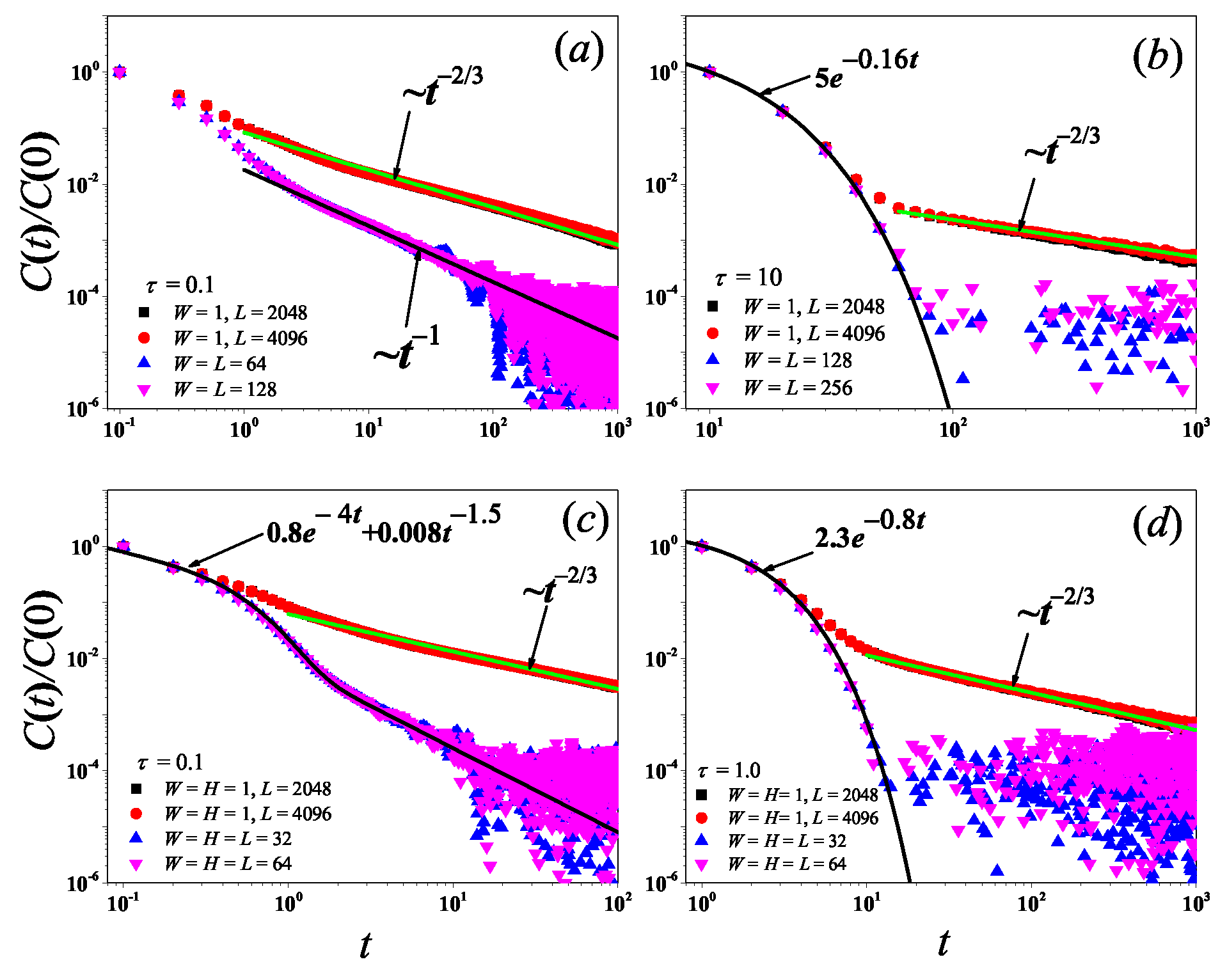

To further support the dimensional-crossover behavior of heat conduction observed above, we perform the equilibrium simulations of

in 2D and 3D fluid models. The results for

with different

values are presented in

Figure 15. We can see from

Figure 15 (a) and (b) that in 2D fluid models, under the condition of increasing the aspect ratio of the system, for heat conduction dominated by the hydrodynamic effect (

) or dominated by the kinetic effect (

),

will eventually change to a power-law decay

. As is shown in

Figure 15 (c) and (d), in 3D fluid models, there is also a similar phenomenon that

will eventually change to a power-law divergence for the hydrodynamic effect (

) and the kinetic effect (

).

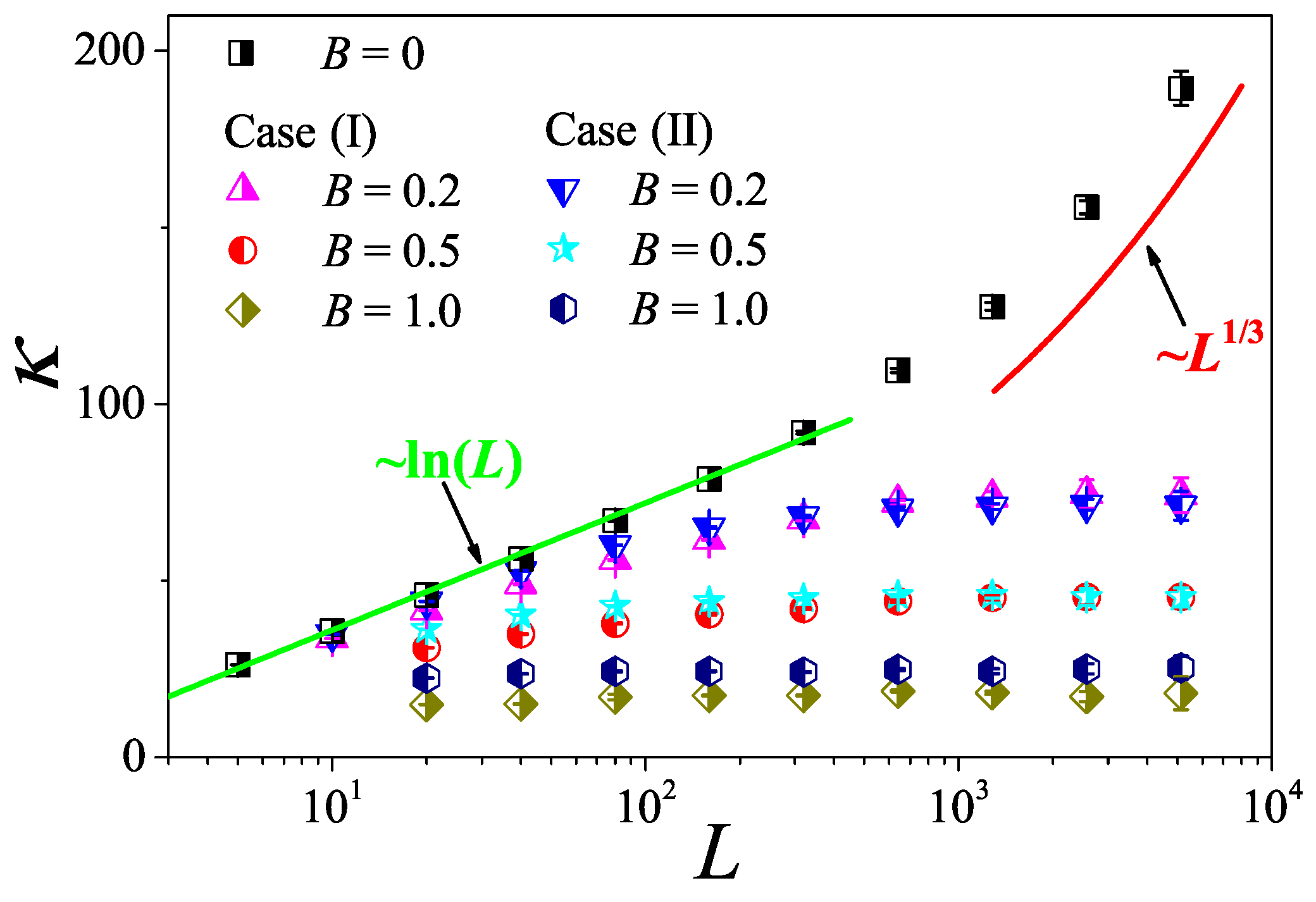

7. Heat Transfer with Magnetic Field

Another issue that can be studied through the MPC dynamics concerns the influence of a magnetic field on transport [

47,

48,

49,

50]. It is generally believed that heat conduction behavior is normal in low-dimensional systems where momentum is not conserved [

10,

11]. However, there is a counterexample in a low-dimensional system with magnetic field. Specifically, heat transport via the one-dimensional charged particle systems with transverse motions is studied in [

47], where researchers studied two cases: case (I) with uniform charge and case (II) with alternate charge. An intriguing finding of this study is that in both cases involving non-zero magnetic fields, the heat conduction behaviors exhibit anomalies, similar to the case where momentum is conserved under the zero magnetic field condition. Remarkably, the abnormal behavior in case (I) is different from the case without magnetic field, suggesting a novel dynamical universality class. Due to the presence of the magnetic field, the standard momentum conservation in such a system is no longer satisfied but is replaced by the pseudomomentum conservation [

51]. Thus, there are two relevant questions: (1) Does the pseudomomentum conservation of a system lead to abnormal heat conduction? (2) Can the abnormal behaviors in both cases also be observed in low-dimensional fluids under the same pseudomomentum conservation?

The above two questions have been well answered only recently in our research [

52], where it is shown that under the same pseudomomentum conservation, the 2D fluid system with magnetic field can exhibit normal heat conduction behavior. Specifically, we consider a 2D system of charged particles as depicted in

Figure 1 (b). In this system, a constant magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of motion,

, is imposed. The particles interact via the modified MPC dynamics to maintain the pseudomomentum conservation of the system (see [

52] for details). To compare with the results obtained in [

47], we also consider two cases: case (I) with uniform charges

and case (II) with opposite charges on each half of particles, say

. In

Figure 16, we plot the relation of

vs

L for various

B obtained by nonequilibrium thermal-wall method. It is shown that for

, the system with momentum conservation exhibits the crossover from 2D to 1D behavior of the thermal conductivity under the condition of increasing the aspect ratio of the system. However, for

, heat conduction behaviors in both cases with pseudomomentum conservation are normal because as

L increases,

approaches a finite value.

Obviously, our above results are at variance with the findings in [

47]. There, heat conduction in presence of pseudomomentum conservation in two cases are abnormal. This observation, together with our results, thus clarify that pseudomomentum conservation is not related to the normal and anomalous behaviors of heat conduction and provide an example of the difference in heat conduction between fluids and lattices in the presence of the magnetic field condition.

For completeness, we also mention that the MPC scheme can be extended to the case of charged particles that yields a self-consistent electric field. This situation is relevant for plasma physics and can be treated by coupling the MPC dynamics with a Poisson solver (see [

53] and references therein for details). The effect of the electric field on heat transport can be studied by this method: simulations reveal that the field does not affect significantly the hydrodynamics of the model, at least for not too large amplitude fluctuations [

53].

Figure 1.

(Color online) Schematic illustration of 1D (a) , 2D (b) and 3D (c) fluid of interacting particles in a system volume described by the MPC dynamics. The system is coupled at its left and right ends to one of two heat baths at fixed temperature and (See text for more details).

Figure 1.

(Color online) Schematic illustration of 1D (a) , 2D (b) and 3D (c) fluid of interacting particles in a system volume described by the MPC dynamics. The system is coupled at its left and right ends to one of two heat baths at fixed temperature and (See text for more details).

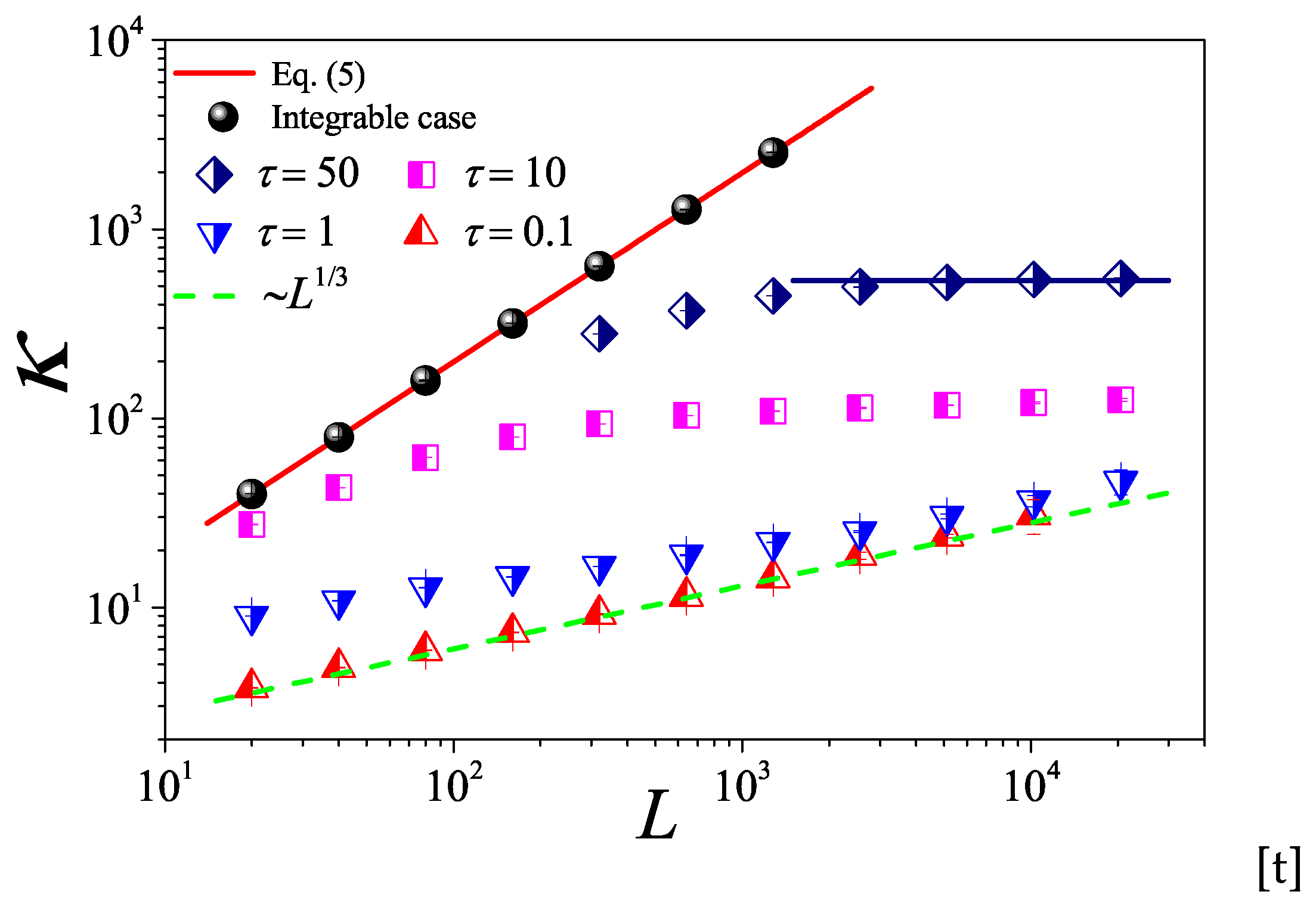

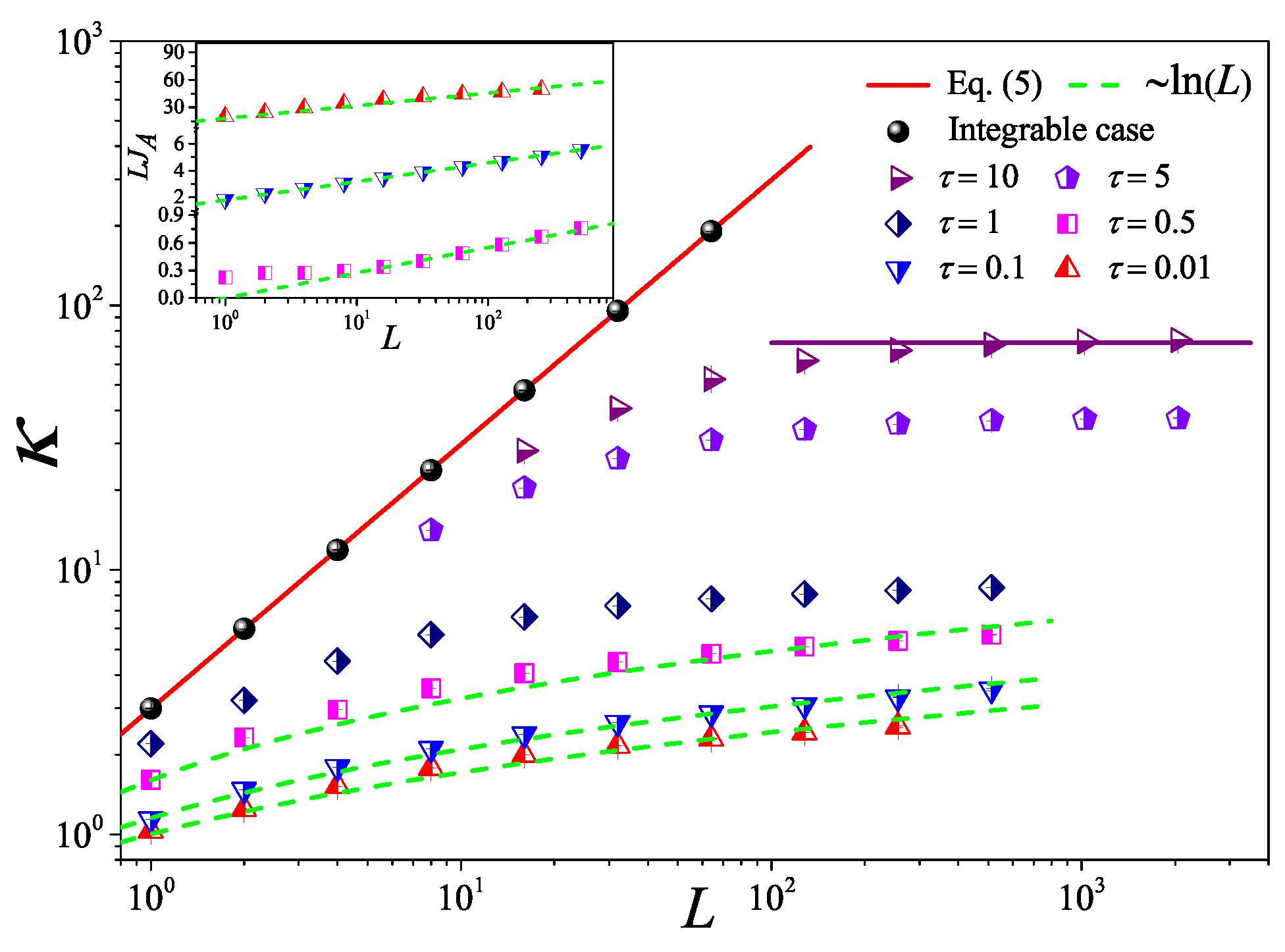

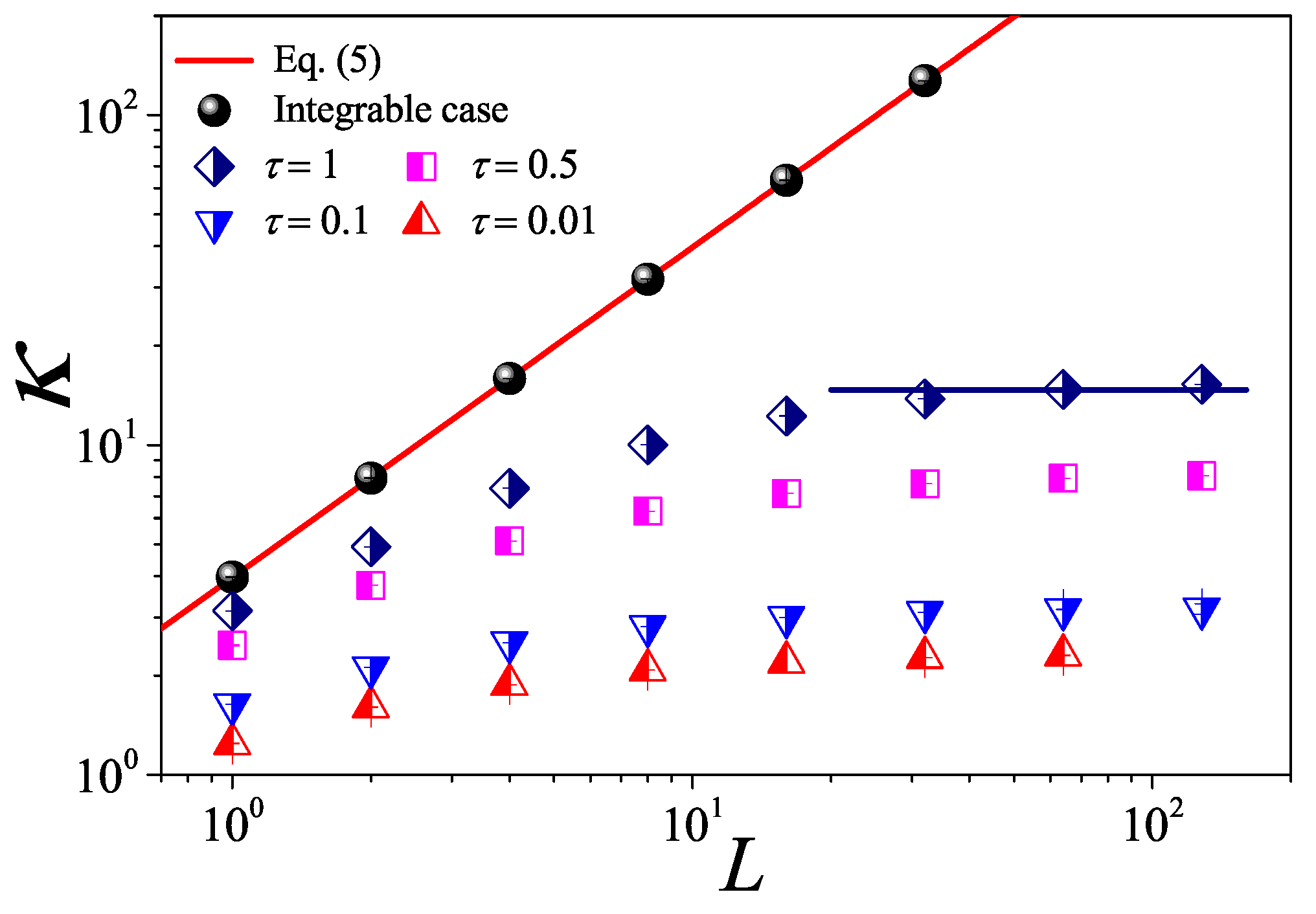

Figure 2.

(Color online) The thermal conductivity

as a function of the system length

L for the 1D fluid system with different

values. The symbols are for the numerical results, and for reference the green dashed line indicates the divergence with

L as

. For

, the horizontal line denotes the saturation value of

obtained by Eq. (

7), where the integration is up a time

with

measured in Figure 5.

Figure 2.

(Color online) The thermal conductivity

as a function of the system length

L for the 1D fluid system with different

values. The symbols are for the numerical results, and for reference the green dashed line indicates the divergence with

L as

. For

, the horizontal line denotes the saturation value of

obtained by Eq. (

7), where the integration is up a time

with

measured in Figure 5.

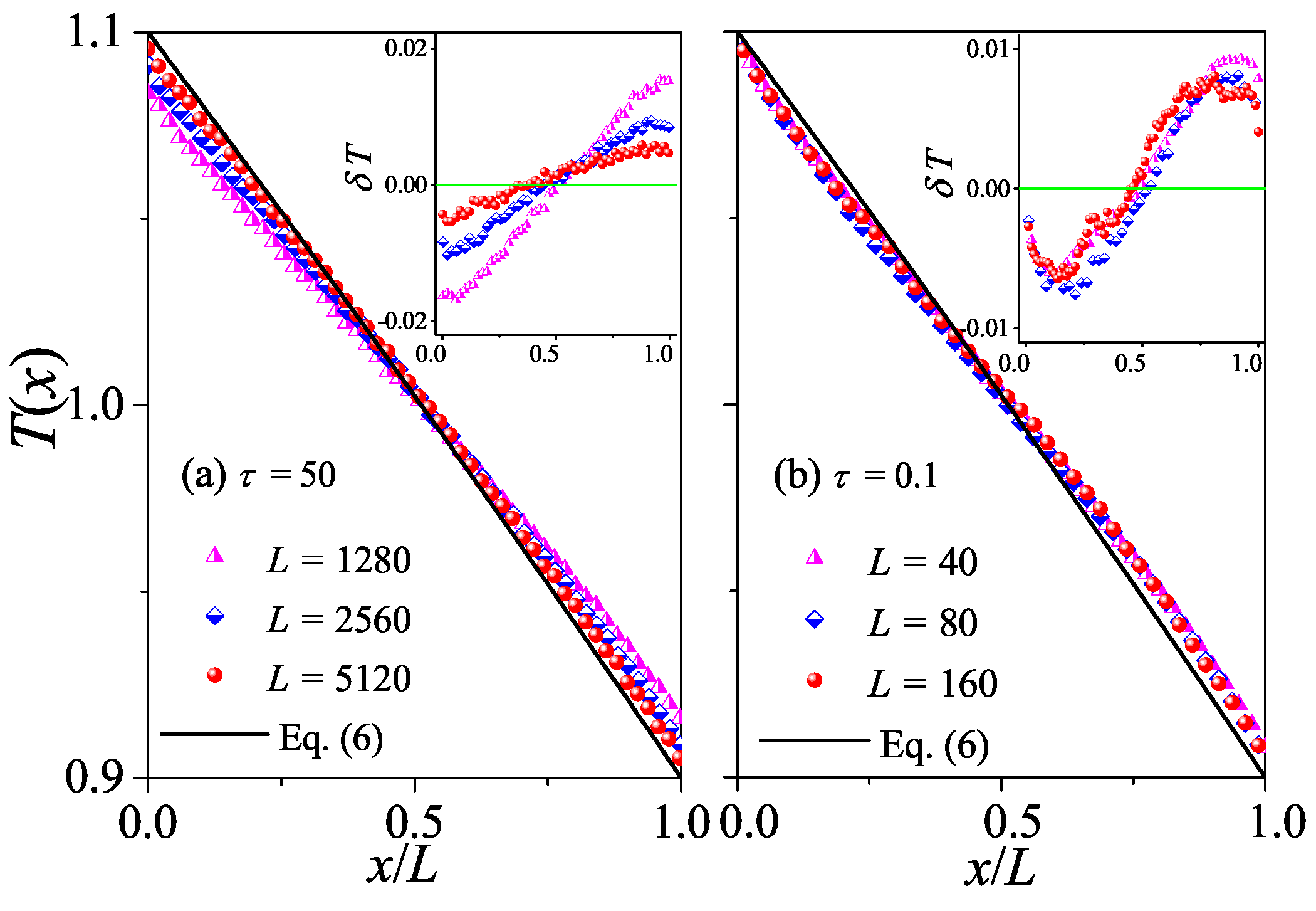

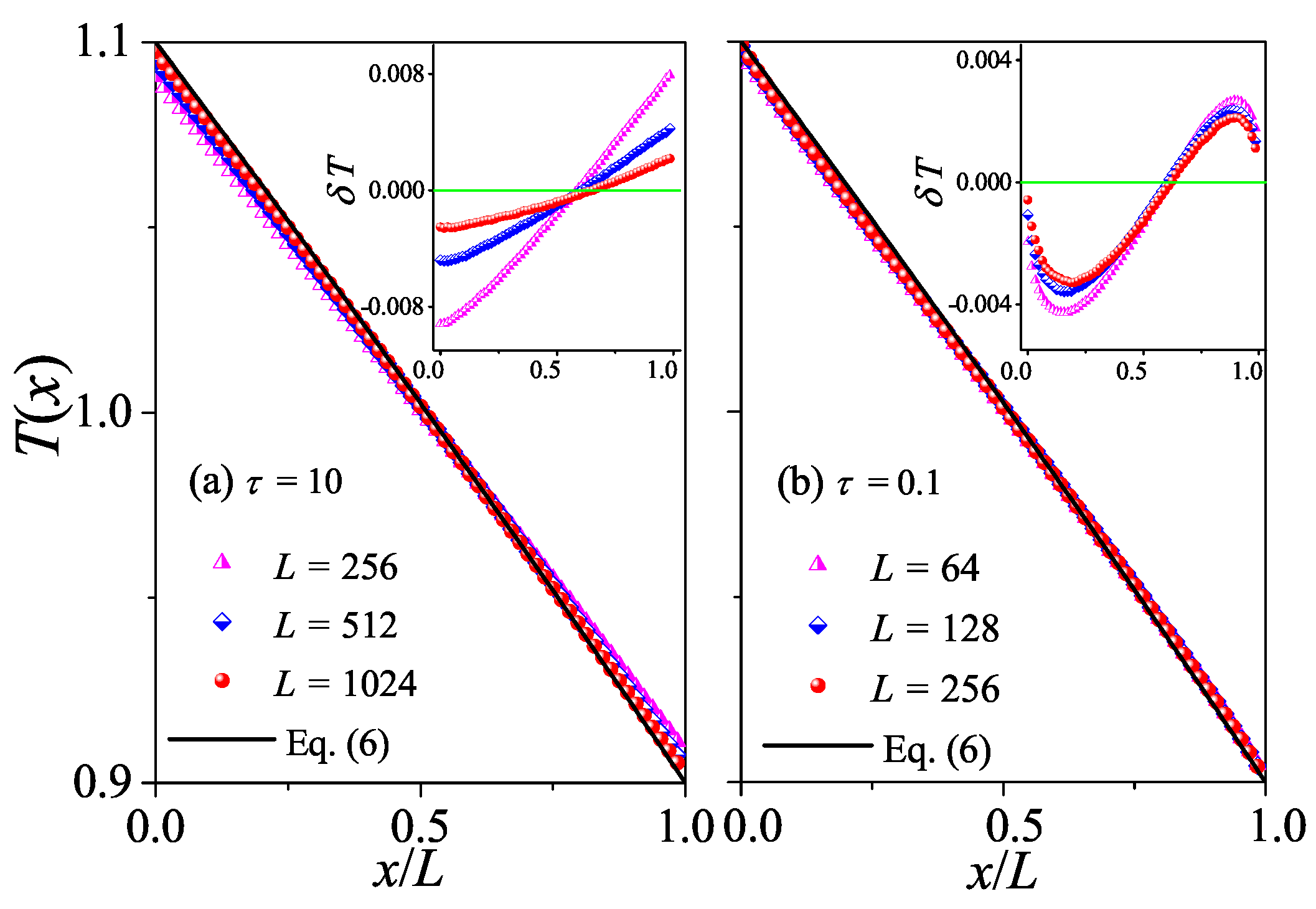

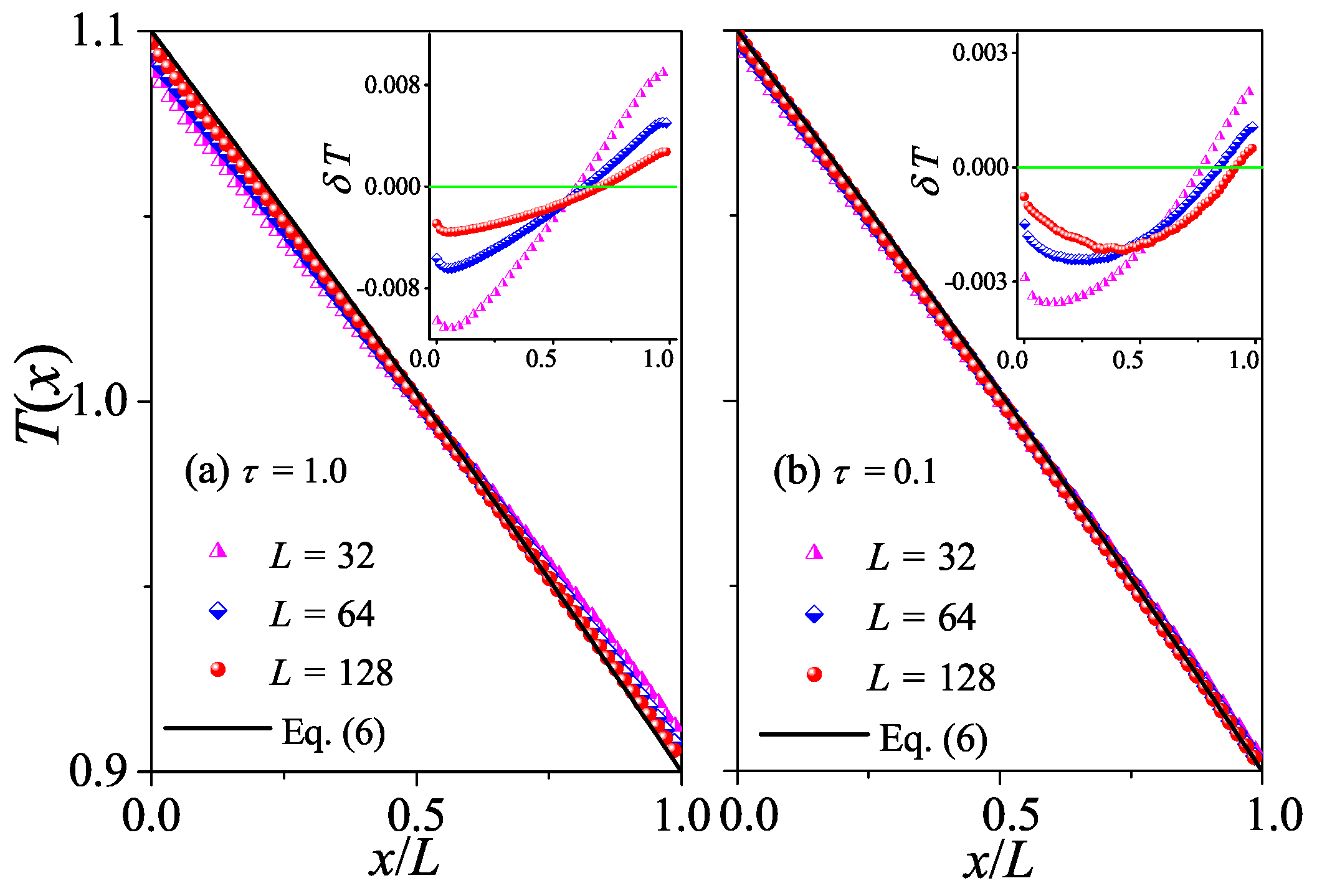

Figure 3.

(Color online) Plot of temperature profiles

for the 1D fluid system with different

L values. Here our numerical results are compared with the analytical Eq. (

6). In (a) and (b) we fix

and

, respectively. Inset: Plot of the differences

between the data and the black line, and the green line at

are for reference.

Figure 3.

(Color online) Plot of temperature profiles

for the 1D fluid system with different

L values. Here our numerical results are compared with the analytical Eq. (

6). In (a) and (b) we fix

and

, respectively. Inset: Plot of the differences

between the data and the black line, and the green line at

are for reference.

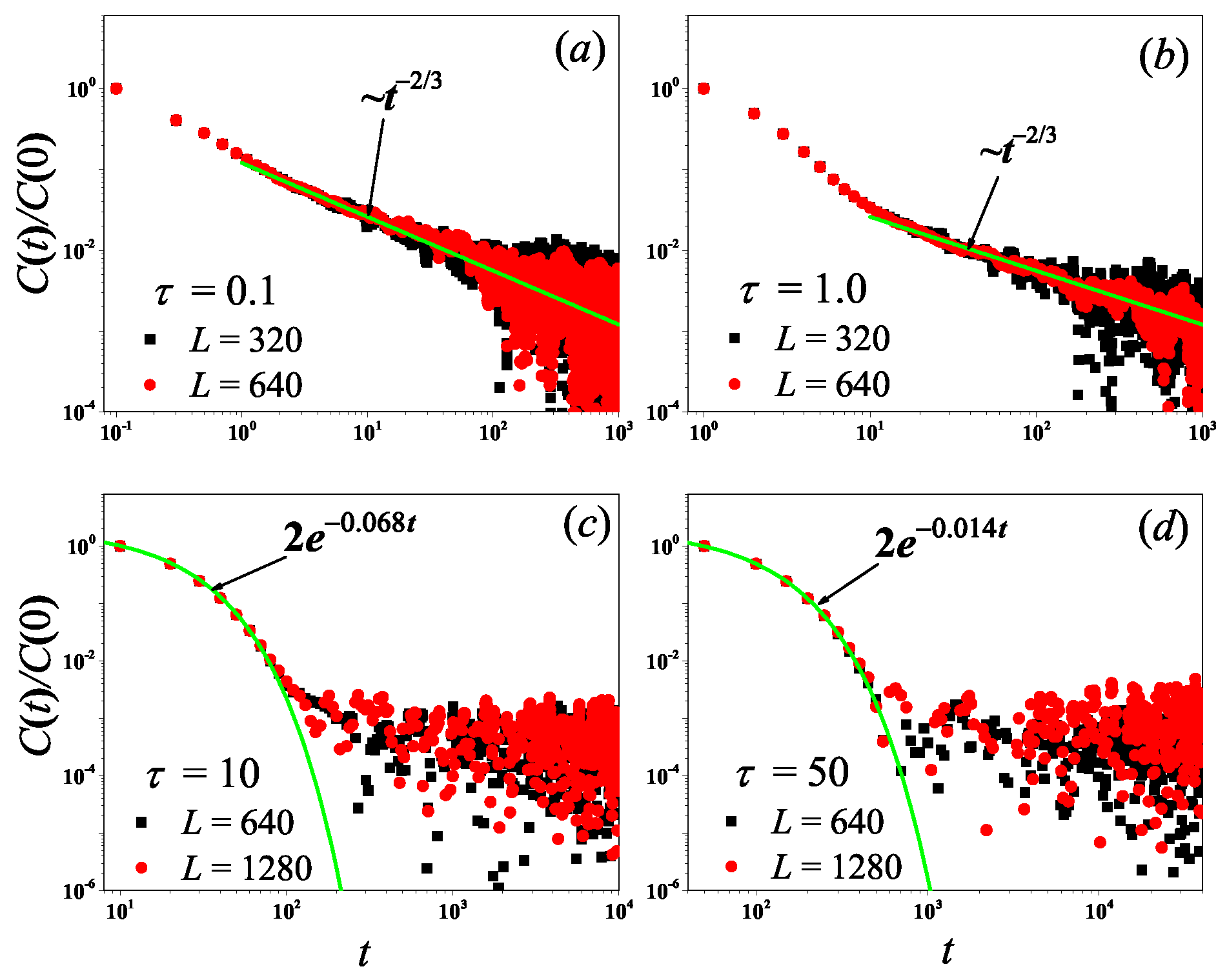

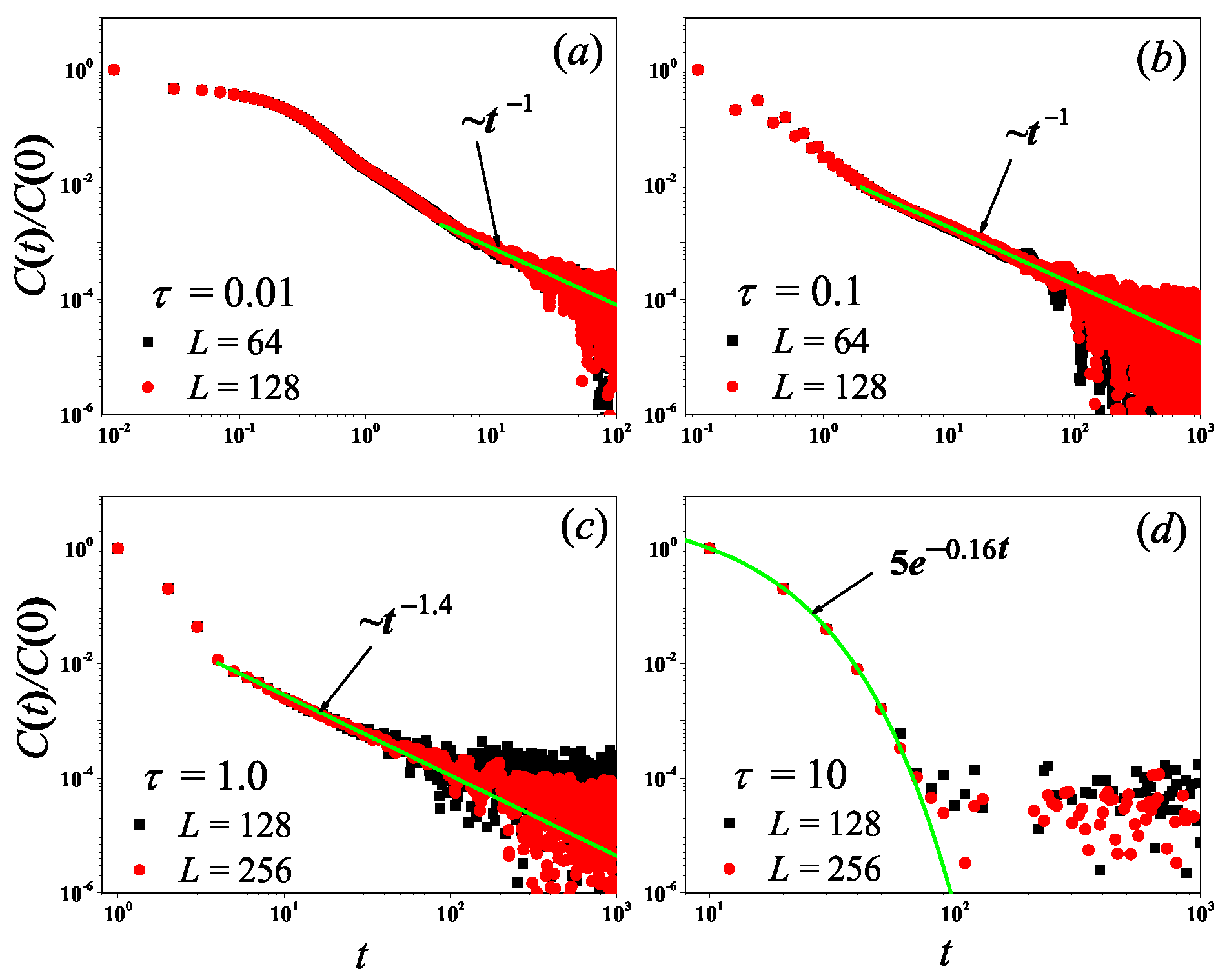

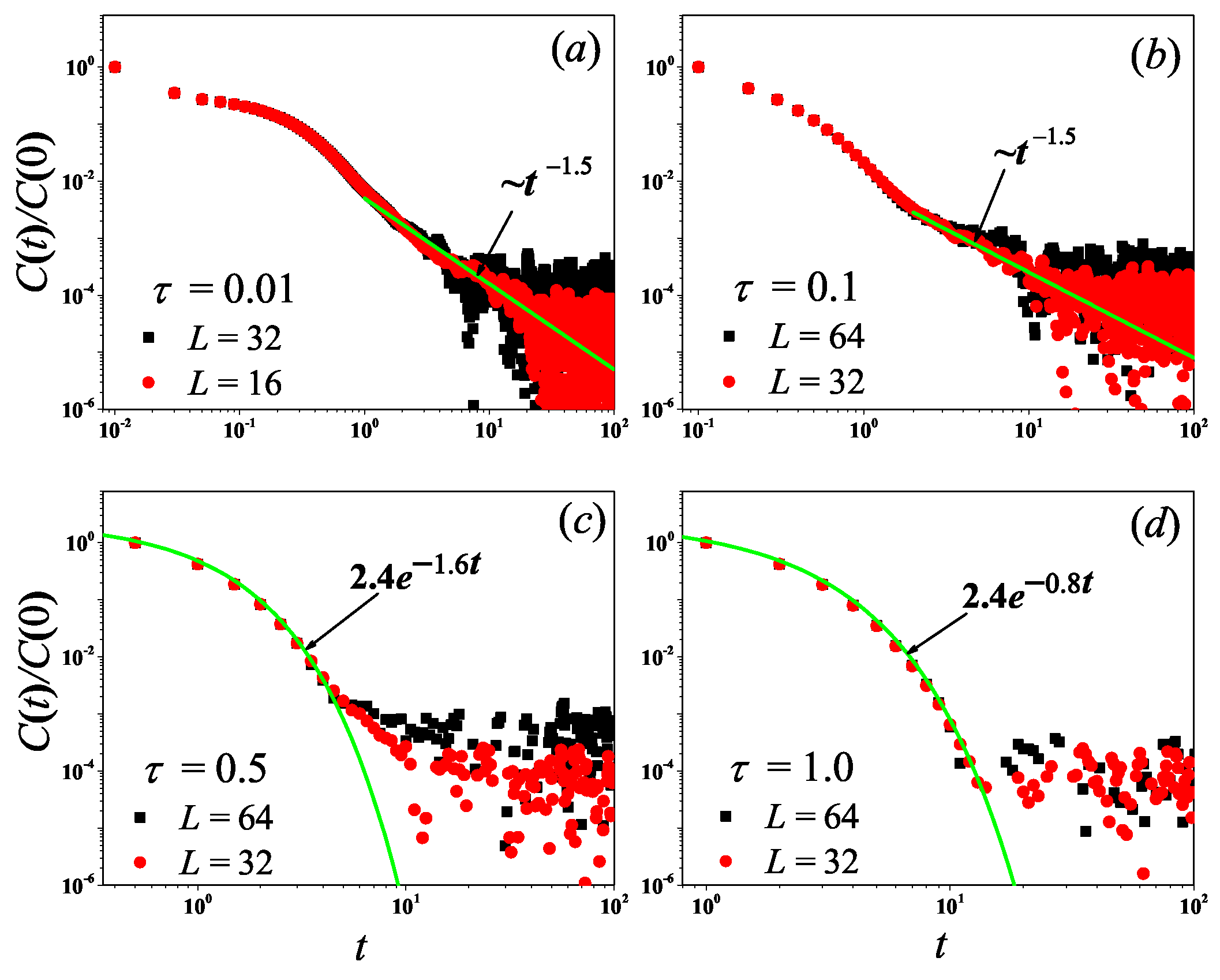

Figure 4.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 1D fluid system with different values. For reference the green solid line is the best fitting function for the data.

Figure 4.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 1D fluid system with different values. For reference the green solid line is the best fitting function for the data.

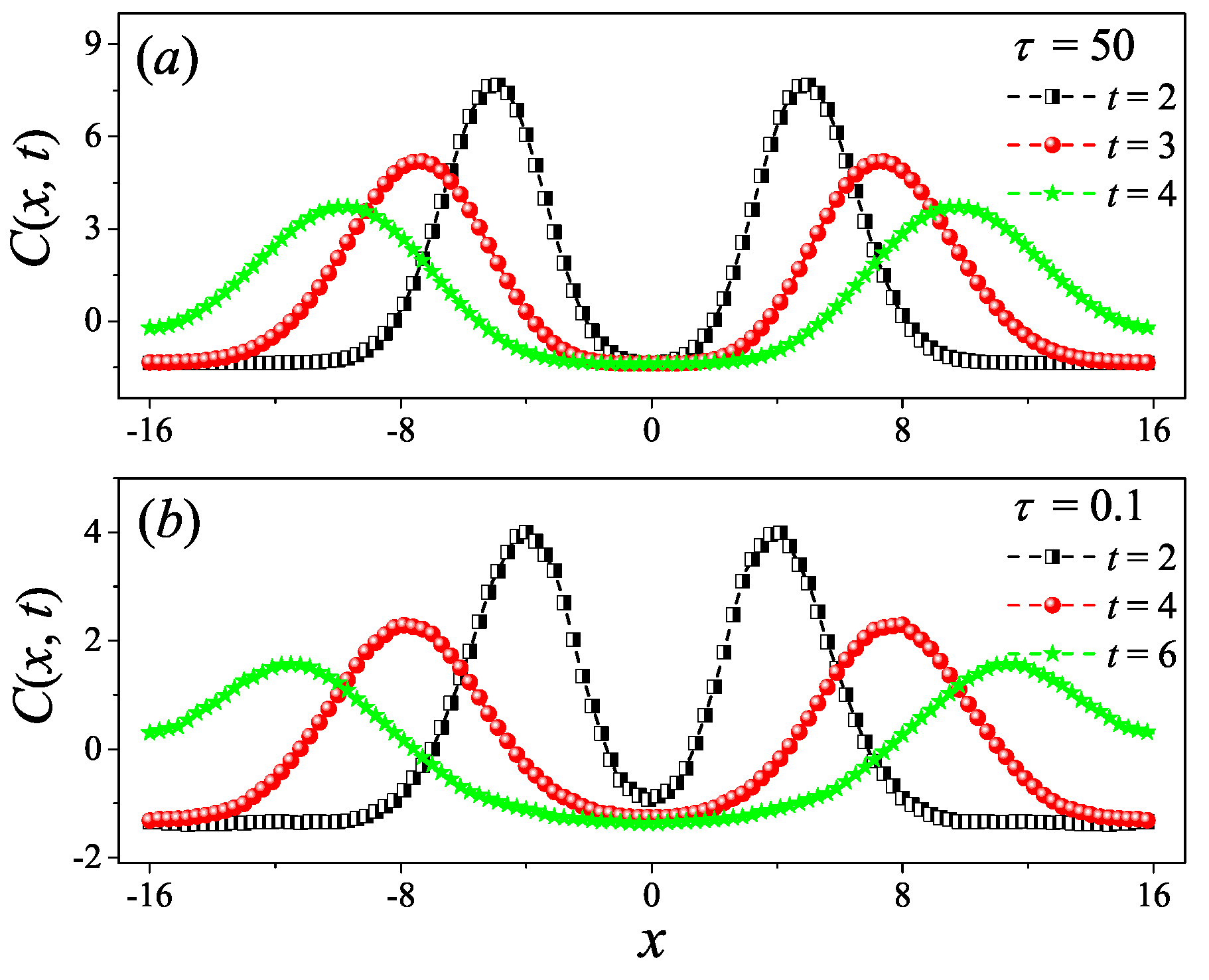

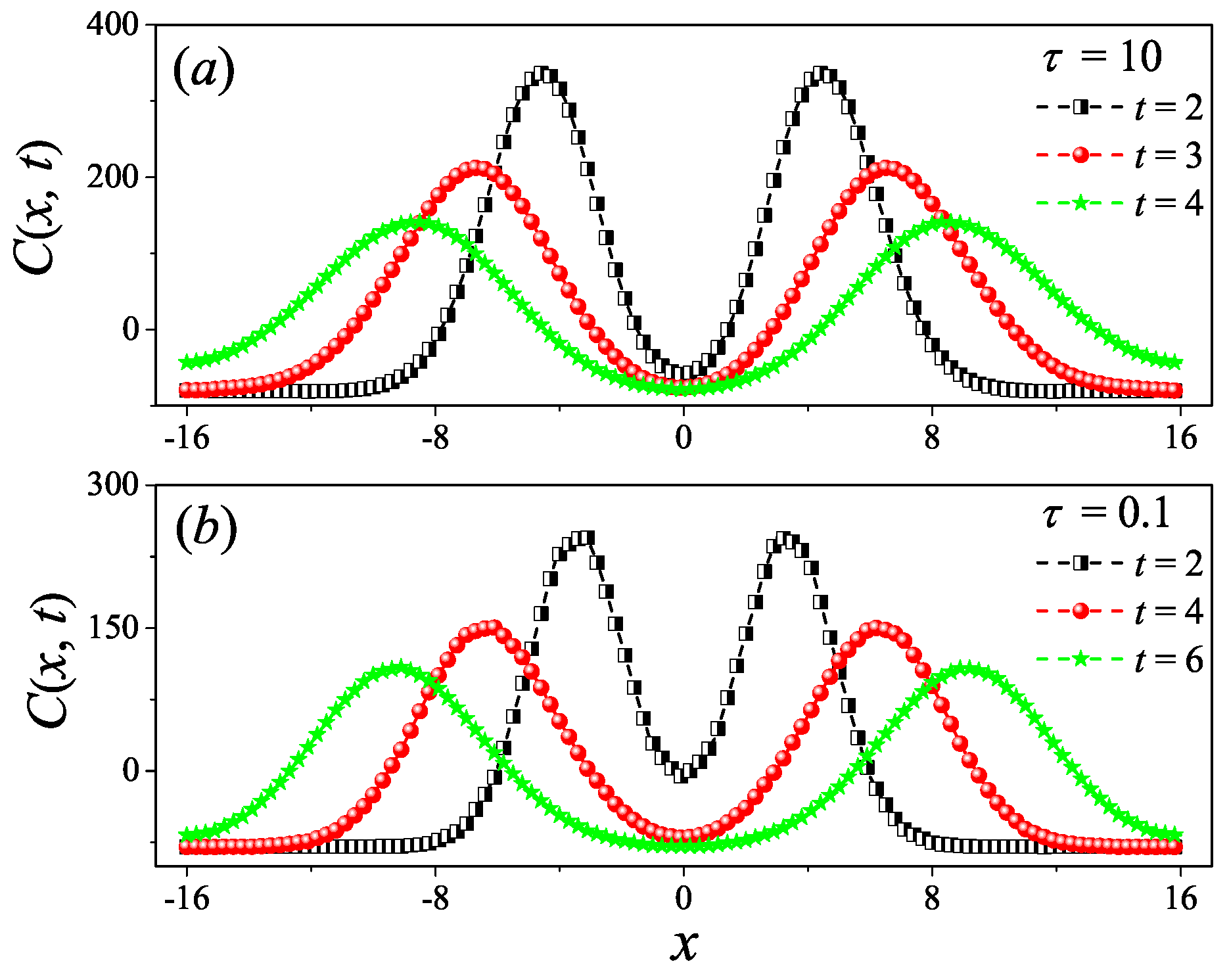

Figure 5.

Numerical calculation of the spatiotemporal correlation function for the 1D fluid system with (a) and (b). Here the system length is set to be . One can clearly see the two peaks (the hydrodynamic mode of sound) moving oppositely away from in (a) and (b).

Figure 5.

Numerical calculation of the spatiotemporal correlation function for the 1D fluid system with (a) and (b). Here the system length is set to be . One can clearly see the two peaks (the hydrodynamic mode of sound) moving oppositely away from in (a) and (b).

Figure 6.

(Color online) The thermal conductivity

as a function of the system length

L for the 2D square fluid system with different

values. The symbols are for the numerical results, and for reference the green dashed line indicates the divergence with

L as

. For

, the horizontal line denotes the saturation value of

obtained by Eq. (

7), where the integration is up a time

with

measured in Figure 9. The inset: the log-linear scale is plotted to appreciate the relationship between the product of the anomalous flux

and

L and

L. Here we set

.

Figure 6.

(Color online) The thermal conductivity

as a function of the system length

L for the 2D square fluid system with different

values. The symbols are for the numerical results, and for reference the green dashed line indicates the divergence with

L as

. For

, the horizontal line denotes the saturation value of

obtained by Eq. (

7), where the integration is up a time

with

measured in Figure 9. The inset: the log-linear scale is plotted to appreciate the relationship between the product of the anomalous flux

and

L and

L. Here we set

.

Figure 7.

(Color online) Plot of temperature profiles

for the 2D square fluid system with different

L values. Here our numerical results are compared with the analytical Eq. (

6). In (a) and (b) we fix

and

, respectively. Inset: Plot of the differences

between the data and the black line, and the green line at

are for reference.

Figure 7.

(Color online) Plot of temperature profiles

for the 2D square fluid system with different

L values. Here our numerical results are compared with the analytical Eq. (

6). In (a) and (b) we fix

and

, respectively. Inset: Plot of the differences

between the data and the black line, and the green line at

are for reference.

Figure 8.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 2D square fluid system with different values. For reference the green solid line is the best fitting function for the data. Here we set .

Figure 8.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 2D square fluid system with different values. For reference the green solid line is the best fitting function for the data. Here we set .

Figure 9.

Numerical calculation of the spatiotemporal correlation function for the 2D square fluid system with (a) and (b). Here we set . One can clearly see the two peaks (the hydrodynamic mode of sound) moving oppositely away from in (a) and (b).

Figure 9.

Numerical calculation of the spatiotemporal correlation function for the 2D square fluid system with (a) and (b). Here we set . One can clearly see the two peaks (the hydrodynamic mode of sound) moving oppositely away from in (a) and (b).

Figure 10.

(Color online) The thermal conductivity as a function of the system length L for the 3D cubic fluid system with different values. Here we set .

Figure 10.

(Color online) The thermal conductivity as a function of the system length L for the 3D cubic fluid system with different values. Here we set .

Figure 11.

(Color online) Plot of temperature profiles

for the 3D cubic fluid system with different

L values. Here our numerical results are compared with the analytical Eq. (

6). In (a) and (b) we fix

and

, respectively. Inset: Plot of the differences

between the data and the black line, and the green line at

are for reference.

Figure 11.

(Color online) Plot of temperature profiles

for the 3D cubic fluid system with different

L values. Here our numerical results are compared with the analytical Eq. (

6). In (a) and (b) we fix

and

, respectively. Inset: Plot of the differences

between the data and the black line, and the green line at

are for reference.

Figure 12.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 3D cubic fluid system with different values. For reference the green solid line is the best fitting function for the data. Here we set .

Figure 12.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 3D cubic fluid system with different values. For reference the green solid line is the best fitting function for the data. Here we set .

Figure 13.

Numerical calculation of the spatiotemporal correlation function for the 3D cubic fluid system with (a) and (b). Here we set . One can clearly see the two peaks (the hydrodynamic mode of sound) moving oppositely away from in (a) and (b).

Figure 13.

Numerical calculation of the spatiotemporal correlation function for the 3D cubic fluid system with (a) and (b). Here we set . One can clearly see the two peaks (the hydrodynamic mode of sound) moving oppositely away from in (a) and (b).

Figure 14.

(Color online) The dimensional crossover behavior of heat conduction for the 2D (a) and 3D (b) fluid system with different values.

Figure 14.

(Color online) The dimensional crossover behavior of heat conduction for the 2D (a) and 3D (b) fluid system with different values.

Figure 15.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 2D and 3D fluid system with different values. For reference, the green and black solid lines are the best fitting functions for the data.

Figure 15.

(Color online) Correlation functions of the total heat current for the 2D and 3D fluid system with different values. For reference, the green and black solid lines are the best fitting functions for the data.

Figure 16.

The heat conductivity as a function of the system length L for the 2D fluid system without and with a magnetic field. The symbols are for the numerical results. For reference the green straight line is the best logarithmic fit, and the red curve line indicates the divergence with L as . Except for and , other parameters are consistent with those adopted in this paper.

Figure 16.

The heat conductivity as a function of the system length L for the 2D fluid system without and with a magnetic field. The symbols are for the numerical results. For reference the green straight line is the best logarithmic fit, and the red curve line indicates the divergence with L as . Except for and , other parameters are consistent with those adopted in this paper.