Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Biodentine, a tricalcium silicate cement, has emerged as a retrograde root-end filling material to promote periapical lesion (PL) healing after apicoectomy. However, its underlying mechanisms remain unclear. This study tested the hypothesis that Biodentine stimulates the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) derived from PLs. The Biodentine extract (B-Ex) was prepared following ISO 10993-12 by incubating polymerized Biodentine in RPMI medium (0.2 g/mL) for three days at 37 °C. B-Ex, containing both released microparticles and soluble components, was incubated with PL-MSCs cultured in either basal MSC medium or suboptimal osteogenic medium. Osteogenic differentiation was assessed by Alizarin Red staining and the expression of 20 osteoblastogenesis-related genes, including transcription factors, signaling molecules, extracellular matrix proteins, bone hormones, cytokines/cytokine receptors, and bone remodeling factors. Non-cytotoxic concentrations of B-Ex stimulated the proliferation of PL-MSCs and induced their osteogenic differentiation in a dose-dependent manner, with a significantly enhanced effect in suboptimal osteogenic medium. The differentiation process was prolonged relative to optimal osteogenic conditions. The stimulatory effect of B-Ex was primarily calcium-dependent, as it was reduced by 85% when B-Ex was treated with the calcium-chelating agent EGTA. In conclusion, Biodentine promotes the osteogenic differentiation of PL-MSCs in a calcium-dependent manner, supporting its stimulatory role in periapical healing.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Establishment and Characterization of PL-MSCs

2.2. Cytotoxicity of the Biodentine Extract

2.3. The Effect of Biodentine Extract on Osteogenic Differentiation of PL-MSCs

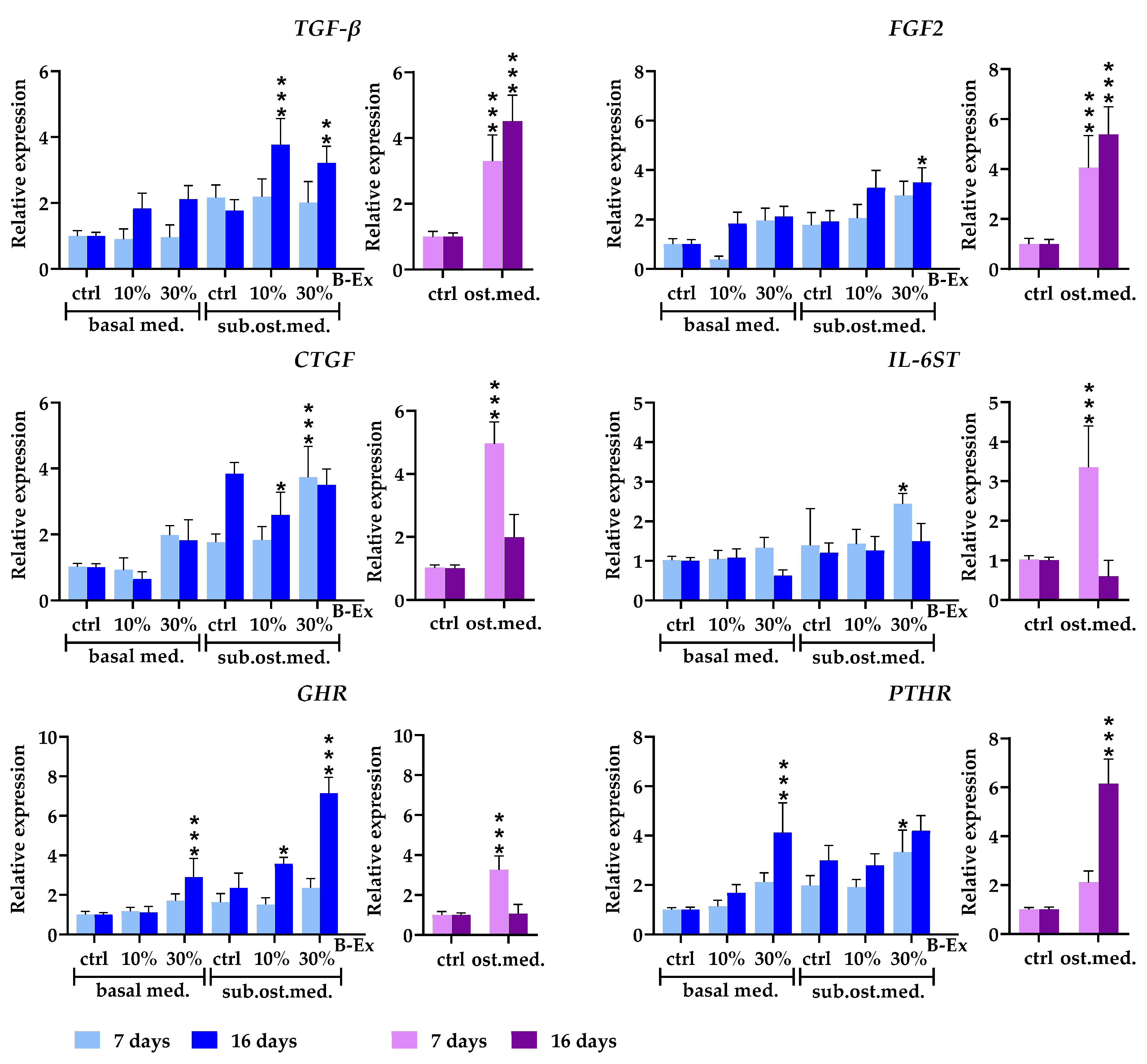

2.4. The Biotine Extract Significantly Modulates the Expression of Osteoblastic Genes

2.5. Genes Expressed in Early and Late Phases of Osteogenic Differentiation

2.6. Cytokine/Cytokine Receptor Genes and Hormone Receptor Genes

2.7. Genes Modeling Bone and Extracellular Matrix

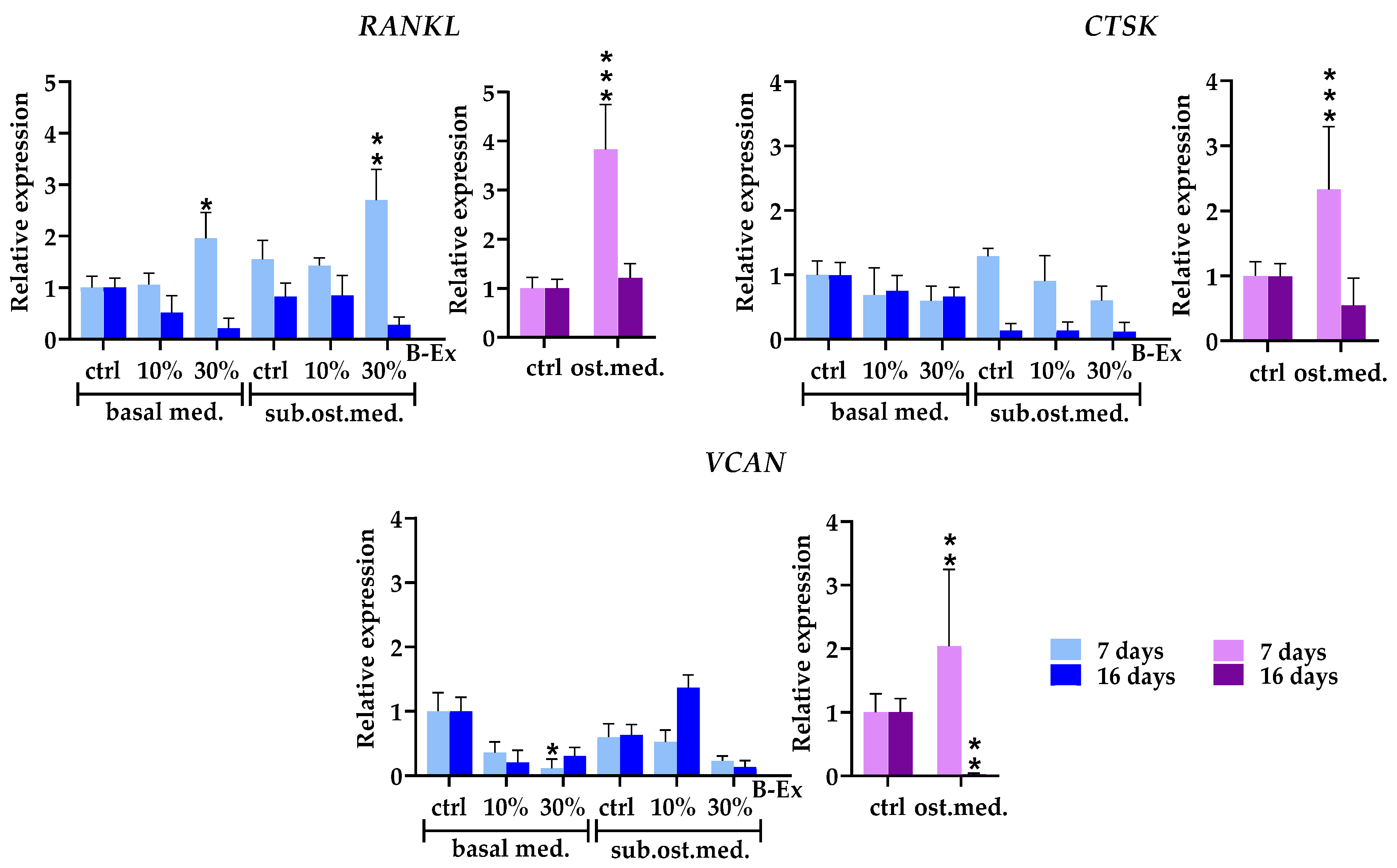

2.8. Genes Modulating Osteoblast Signaling

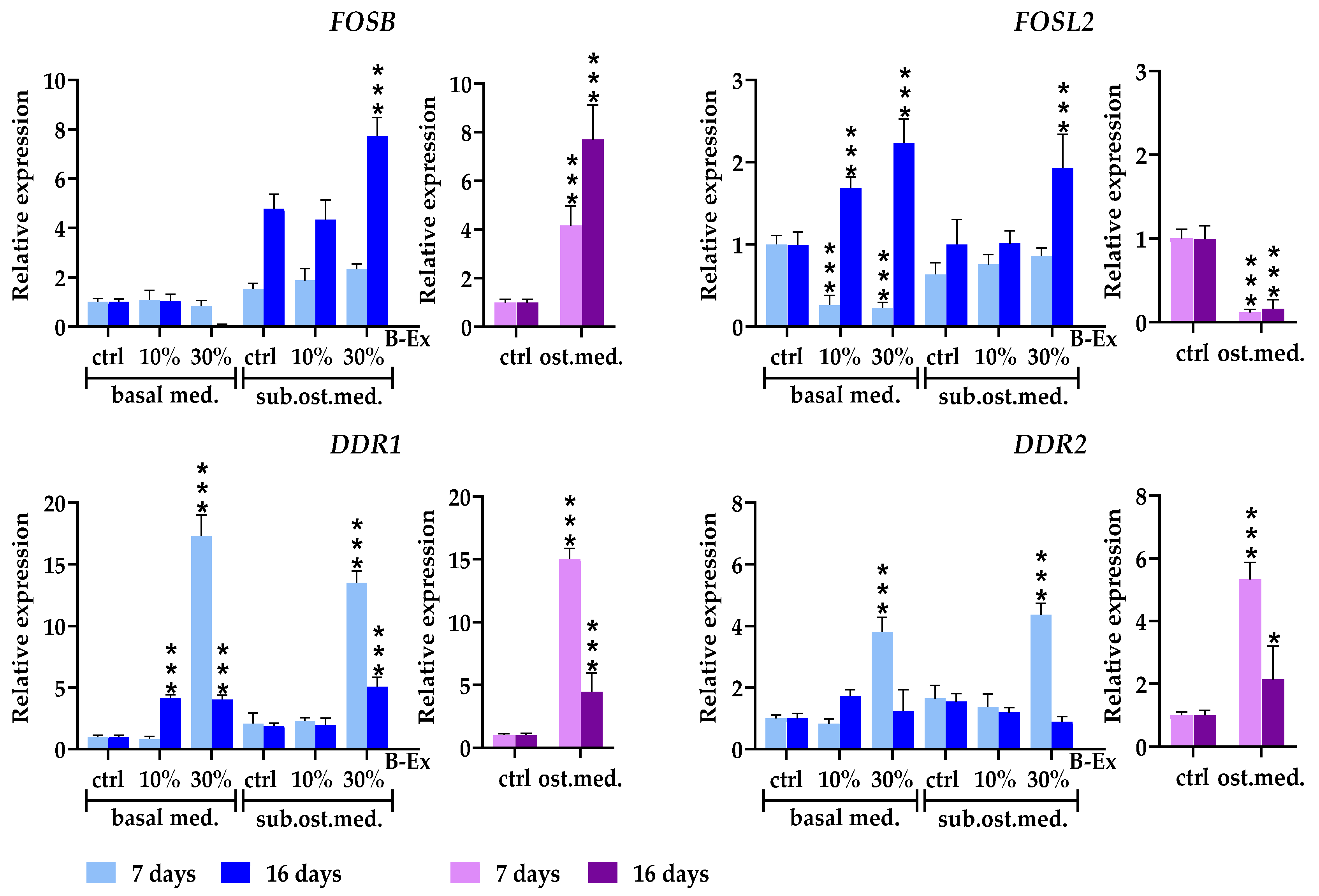

2.9. The Role of Calcium in PL-MSC Proliferation and Osteoblastic Differentiation Induced by Biodentine Extract

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Periapical Tissue

4.2. Preparation of Conditioned Medium from Biodentine

4.3. Establishment of PL-MSCs

4.4. Phenotypic Analysis of PL-MSCs

4.5. Differentiation of PL-MSCs

4.6. Cytotoxicity Tests

4.7. Modulatory Effect of Biodentine Extract on Osteoblast Differentiation of PL-MSCs

4.8. Gene Expression Determination by Real-Time PCR

4.9. Proliferation Tests

4.10. The Role of Ca in the Proliferation and Osteoblastogenic Activity of Biodentine Extract

4.11. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahmoud, S.; El-Negoly, S.; Zaeneldin, A.; El-Zekrid, M.; Grawish, L.; Grawish, H.; Grawish, M. Biodentine versus mineral trioxide aggregate as a direct pulp capping material for human mature permanent teeth – A systematic review. J. Conserv. Dent. 2018, 21, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, H.; Mahendran, K.; Velusamy, V.; Babu, S. BIODENTINE- A review on its properties and clinical applications. J. Biomed. Pharm. Res. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérard, M.; Le Clerc, J.; Watrin, T.; Meary, F.; Pérez, F.; Tricot-Doleux, S.; Pellen-Mussi, P. Spheroid model study comparing the biocompatibility of Biodentine and MTA. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, L.B.; Cosme-Silva, L.; Fernandes, A.P.; Oliveira, T.M.; Cavalcanti, B.D.N.; Gomes Filho, J.E.; Sakai, V.T. Effects of mineral trioxide aggregate, Biodentine™ and calcium hydroxide on viability, proliferation, migration and differentiation of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 26, e20160629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuarqoub, D.; Aslam, N.; Jafar, H.; Abu Harfil, Z.; Awidi, A. Biocompatibility of Biodentine™ with periodontal ligament stem cells: In vitro study. Dent. J. (Basel) 2020, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.M.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Li, L.; Zheng, Y.F.; Häkkinen, L.; Haapasalo, M. In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of a novel root repair material. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, R.; Elhennawy, K.; Schwendicke, F. Effects of calcium silicate cements on dental pulp cells: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2018, 77, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, A.; Erber, R.; Frese, C.; Gehrig, H.; Saure, D.; Mente, J. In vitro evaluation of different dental materials used for the treatment of extensive cervical root defects using human periodontal cells. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.R.; Emara, R.; Taher, M.M.; Al-Allaf, F.A.; Almalki, M.; Almasri, M.A.; Siddiqui, S.S. Effects of mineral trioxide aggregate, calcium hydroxide, biodentine, and Emdogain on osteogenesis, odontogenesis, angiogenesis, and cell viability of dental pulp stem cells. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, T.S.; Silva, G.F.; Guerreiro-Tanomaru, J.M.; Delfino, M.M.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Tanomaru-Filho, M.; Cerri, P.S. Biodentine and MTA modulate immunoinflammatory response favoring bone formation in sealing of furcation perforations in rat molars. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wairooy, V.W.; Bagio, D.A.; Margono, A.; Amelia, I. In vitro Analysis of DSPP and BSP Expression: Comparing the Odontogenic Influence of Bio-C Repair and Biodentine in hDPSCs. Eur. J. Dent. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalan, A.L.; Warhadpande, M.M.; Dakshindas, D.M. A comparison of human dental pulp response to calcium hydroxide and Biodentine as direct pulp-capping agents. J. Conserv. Dent. 2017, 20, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolibah, Y.A.; Kouchaji, C.; Lazkani, T.; Ahmad, I.A.; Baghdadi, Z.D. Comparison of MTA versus Biodentine in Apexification Procedure for Nonvital Immature First Permanent Molars: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Children 2022, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, G.; Azérad, J.; Faure, M.-O.; Machtou, P.; Boucher, Y. Use of a new retrograde filling material (Biodentine) for endodontic surgery: two case reports. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2014, 6, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.M.; Kokate, S.R.; Shah, R.A. Management of a large periapical lesion using Biodentine™ as retrograde restoration with eighteen months evident follow-up. J. Conserv. Dent. 2013, 16, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraković, M.; Duka, M.; Bekić, M.; Tomić, S.; Ismaili, B.; Vučević, D.; Čolić, M. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Biodentine on human periapical lesion cells in culture. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 1398–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đokić, J.; Tomić, S.; Cerović, S.; Todorović, V.; Rudolf, R.; Čolić, M. Characterization and immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells from periapical lesions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, T.; Jeanneau, C.; Bergmann, M.; Laurent, P.; About, I. Tricalcium silicate capping materials modulate pulp healing and inflammatory activity in vitro. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjkesh, B.; Isidor, F.; Kraft, D.C.E.; Løvschall, H. In vitro cytotoxic evaluation of novel fast-setting calcium silicate cement compositions and dental materials using colorimetric methyl-thiazolyl-tetrazolium assay. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 60, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, F.; Beyer, K.; König, A.; Hofmann, M.; Butting, M.; Valesky, E.; Kippenberger, S.; Kaufmann, R.; Heidemann, D.; Bernd, A.; Zöller, N.N. Influence of Biodentine® A Dentine Substitute On Collagen Type I Synthesis in Pulp Fibroblasts In Vitro. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggio, C.; Ceci, M.; Dagna, A.; Beltrami, R.; Colombo, M.; Chiesa, M. In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of different pulp capping materials: a comparative study. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2015, 66, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attik, G.N.; Villat, C.; Hallay, F.; Pradelle-Plasse, N.; Bonnet, H.; Moreau, K.; Colon, P.; Grosgogeat, B. In vitro biocompatibility of a dentine substitute cement on human MG63 osteoblasts cells: Biodentine™ versus MTA®. Int. Endod. J. 2014, 47, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009. Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization, 2009.

- Hanna, H.; Mir, L.M.; Andre, F.M. In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells generates cell layers with distinct properties. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Shang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Massey, P.A.; Barton, S.R.; Kevil, C.G.; Dong, Y. Notch Signaling in Osteogenesis, Osteoclastogenesis, and Angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawane, T.; Qin, X.; Jiang, Q.; Miyazaki, T.; Komori, H.; Yoshida, C.A.; Matsuura-Kawata, V.K.D.S.; Sakane, C.; Matsuo, Y.; Nagai, K.; Maeno, T.; Date, Y.; Nishimura, R.; Komori, T. Runx2 is required for the proliferation of osteoblast progenitors and induces proliferation by regulating Fgfr2 and Fgfr3. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, H. Transcriptional Programming in Arteriosclerotic Disease: A Multifaceted Function of the Runx2 (Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chen, W.; Qian, A.; et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling components and mechanisms in bone formation, homeostasis, and disease. Bone Res. 2024, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoch, M.L.; Clemens, T.L.; Riddle, R.C. New insights into the biology of osteocalcin. Bone 2016, 82, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; van der Eerden, B.C.J. Osteocalcin: A Versatile Bone-Derived Hormone. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2019, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Liu, J.; Hoff, S.E.; Zhu, C.; Heinz, H. Osteocalcin: Promoter or Inhibitor of Hydroxyapatite Growth? Langmuir 2024, 40, 1747–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Sanskrita, D.; Sourabh, G. Regulation of Human Osteoblast-to-Osteocyte Differentiation by Direct-Write 3D Microperiodic Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdelli, C.; Tavanti, G.S.; Forno, I.; Vaira, V.; Maggiore, R.; Vicentini, L.; Dalino Ciaramella, P.; Perticone, F.; Lombardi, G.; Corbetta, S. Osteocalcin Modulates Parathyroid Cell Function in Human Parathyroid Tumors. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1129930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cupp, M.; Adem, A.; Nayak, S.; Thomsen, W. Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and PTH-Related Peptide Domains Contributing to Activation of Different PTH Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathways. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.; Poudel, S.B.; Yakar, S. Effects of GH/IGF Axis on Bone and Cartilage. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2021, 519, 111052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boraschi-Diaz, I.; Wang, J.; Mort, J.S.; Komarova, S.V. Collagen Type I as a Ligand for Receptor-Mediated Signaling. Front. Phys. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalraj, S. Alkaline Phosphatase: Structure, Expression and Its Function in Bone Mineralization. Gene 2020, 754, 144855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marupanthorn, K.; Tantrawatpan, C.; Kheolamai, P.; Tantikanlayaporn, D.; Manochantr, S. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 enhances the osteogenic differentiation capacity of mesenchymal stromal cells derived from human bone marrow and umbilical cord. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Deng, C.; Li, Y.P. TGFβ and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Pan, W.; Li, H.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; et al. TGF-β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, I.; Selvamurugan, N. Regulation of TGF-β/BMP signaling during osteoblast development by non-coding RNAs: Potential therapeutic applications. Life Sci. 2024, 355, 122969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddaluno, L.; Urwyler, C.; Werner, S. Fibroblast growth factors: Key players in regeneration and tissue repair. Development 2017, 144, 4047–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoenlarp, P.; Rajendran, A.K.; Iseki, S. Role of fibroblast growth factors in bone regeneration. Inflamm. Regen. 2017, 37, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, N.; Jin, M.; Chen, L. Role of FGF/FGFR signaling in skeletal development and homeostasis: Learning from mouse models. Bone Res. 2014, 2, 14003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, J.A.; Lambi, A.G.; Mundy, C.; Hendesi, H.; Pixley, R.A.; Owen, T.A.; Safadi, F.F.; Popoff, S.N. The role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in skeletogenesis. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2011, 21, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, T.N.; Kang, I.; Evanko, S.P.; Harten, I.A.; Chang, M.Y.; Pearce, O.M.T.; Allen, C.E.; Frevert, C.W. Versican—a critical extracellular matrix regulator of immunity and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Wu, Z.; Chu, H.Y.; Lu, J.; Lyu, A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G. Cathepsin K: The action in and beyond bone. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon-Oliva, D.; Barrena-Blázquez, S.; Jiménez-Álvarez, L.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; García-Montero, C.; López-González, L.; Torres-Carranza, D.; García-Puente, L.M.; Carranza, S.T.; Álvarez-Mon, M.Á.; et al. The RANK-RANKL-OPG system: A multifaceted regulator of homeostasis, immunity, and cancer. Medicina 2023, 59, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellin, M.L.; Klinder, A.; Bergschmidt, P.; Bader, R.; Jonitz-Heincke, A. IL-6-induced response of human osteoblasts from patients with rheumatoid arthritis after inhibition of the signaling pathway. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 3479–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, L.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Chuang, S.C.; Cheng, T.L.; Lin, Y.H.; Chou, H.C.; Fu, Y.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, C.Z. Discoidin domain receptor 1 regulates Runx2 during osteogenesis of osteoblasts and promotes bone ossification via phosphorylation of p38. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ge, C.; Pan, H.; Han, Y.; Mishina, Y.; Kaartinen, V.; Franceschi, R.T. Discoidin domain receptor 2 is an important modulator of BMP signaling during heterotopic bone formation. Bone Res. 2025, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croissant, C.; Tuariihionoa, A.; Bacou, M.; Souleyreau, W.; Sala, M.; Henriet, E.; Bikfalvi, A.; Saltel, F.; Auguste, P. DDR1 and DDR2 physical interaction leads to signaling interconnection but with possible distinct functions. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2018, 12, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.; Eferl, R.; Hoebertz, A.; et al. Bone cell differentiation and the role of Fos/AP-1 proteins. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2003, 5 (Suppl 3), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, A.; Bakiri, L.; Jimenez, M.; Schinke, T.; Amling, M.; Wagner, E.F. Fra-2/AP-1 controls bone formation by regulating osteoblast differentiation and collagen production. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Chai, C.Y.; Loh, H.S. In vitro evaluation of osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation on chitosan-TiO2 nanotubes scaffolds with Ca²⁺ ions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 76, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.N.; Hwang, H.S.; Oh, S.H.; Roshanzadeh, A.; Kim, J.W.; Song, J.H.; Kim, E.S.; Koh, J.T. Elevated extracellular calcium ions promote proliferation and migration of mesenchymal stem cells via increasing osteopontin expression. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarem, M.; Heizmann, M.; Barbero, A.; Martin, I.; Shastri, V.P. Hyperstimulation of CaSR in human MSCs by biomimetic apatite inhibits endochondral ossification via temporal downregulation of PTH1R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6135–E6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vázquez, A.; Planell, J.A.; Engel, E. Extracellular calcium and CaSR drive osteoinduction in mesenchymal stromal cells. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2824–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Markers | % positive cells |

|---|---|

| CD73 | 99.43 ± 0.34 |

| CD90 | 99.52 ± 0.30 |

| CD105 | 91.23 ± 3.24 |

| CD166 | 99.02 ± 0.28 |

| CD39 | 90.50 ± 3.64 |

| CD146 | 28.18 ± 6.25 |

| CD56 | 20.04 ± 4.88 |

| SRTRO-1 | 8.06 ± 4.60 |

| SSEA4 | 12.12 ± 5.56 |

| CD45 | 1.12 ± 0.46 |

| CD34 | 1.24 ± 0.37 |

| CD14 | 1.50 ± 0.24 |

| CD3 | 0.54 ± 0.14 |

| CD19 | 0.48 ± 0.22 |

| Culture conditions | Proliferation (cpm) | RUNX2 expression |

|---|---|---|

| Negative control | 642 ± 88 | 1.00 ± 0.12 |

| Ca | 1864 ± 198*** | 16.34 ± 1.92*** |

| Ca + EGTA | 706 ± 102●● | 0.92 ± 0.04●●● |

| 30% B-Ex | 2122 ± 170*** | 22.6 ± 3.90*** # |

| 30% B-Ex + EGTA | 734 ± 102●●● | 3.70 ± 0.86*** ●●● |

| Primers | Sequences (5,-3,) |

|---|---|

| WNT2 | TTCCAGAGCTAACTCGTGCC ACTGGGCTTGAAGGGTGATG |

| COL1A1 | TCGGAGGAGAGTCAGGAAGG AACAGAACAGTCTCTCCCGC |

| SP7 | TTCTGCGGCAAGAGGTTCACTC GTGTTTGCTCAGGTGGTCGCTT |

| BMP-2 | GGGGTGGGGGAAAGGTAATG TCGGGTTATCCAGGTTTTGCT |

| RUNX2 | GCGGTGCAAACTTTCTCCAG TCACTGTGCTGAAGAGGCTG |

| BGLAP | GACTGTGACGAGTTGGCTGA CACATCCATAGGGCTGGGAG |

| TGF-β1 | GGACACCAACTATTGCTTCAGCTCC AGGCTCCAAATGTAGGGGCAGGGCC |

| FGF 2 | GGGTGCCAGATTAGCGGAC GTTCACGGATGGGTGTCTCC |

| ALP |

GGGCATTGTGACTACCACTC AGTCAGGTTGTTCCGATTCA |

| FOSB | TCTGTCTTCGGTGGACTCCTTC GTTGCACAAGCCACTGGAGGTC |

| FOSL2 | AAGAGGAGGAGAAGCGTCGCAT GCTCAGCAATCTCCTTCTGCAG |

| DDR1 | GCGTCTGTCTGCGGGTAGAG ACGGCCTCAGATAAATACATTGTCT |

| DDR2 | TGTTCCTGCTGCTGCCTATCTT AGGATAGCGGCATATAGCTGGAT |

| CTGF | GTTTGGCCCAGACCCAACT GGAACAGGCGCTCCACTCT |

| VCAN | TTGGACCTCAGGCGCTTTCTAC GGATGACCAATTACACTCAAATCAC |

| RANKL | GCCTTTCAAGGAGCTGTGCAAAA GAGCAAAAGGCTGAGCTTCAAGC |

| CTSK | GAGGCTTCTCTTGGTGTCCATAC TTACTGCGGGAATGAGACAGGG |

| IL-6ST | CACCCTGTATCACAGACTGGCA TTCAGGGCTTCCTGGTCCATCA |

| PTHR | CATCTTTTGGTCCATCTGTCCATC CTGGAGACCCTCGAGACCACA |

| GHR | TGCTTTTTCTGGAAGTGAGGA GGTTCTTTGTACCATGATGAACCT |

| GAPDH | GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).