1. Introduction

Endodontic treatment focuses on preserving natural teeth by eliminating infections and preventing periapical pathology [

1]. Various diagnostic tools, including apex locators and dental endoscopes, have been introduced to aid endodontic treatment [

2,

3]. However, intraoral digital periapical radiographs remain the most widely used imaging modality in endodontics due to their accessibility and reliability [

4]. These radiographs provide valuable insights into dentoalveolar structures, allowing clinicians to assess root morphology, canal anatomy, and treatment accuracy [

3,

4,

5]. Nevertheless, the inconvenience of conventional periapical radiographs is their two-dimensional (2D) nature, which can introduce geometric distortions and restrict the evaluation of lesion size, extent, and precise location [

3,

4,

5].

The assessment of endodontic treatment success is based on radiographic criteria. A well-sealed root canal filling and the absence of periapical radiolucency are key indicators of favorable treatment outcomes [

6,

7]. The length and density of the filling are crucial factors in preventing microbial infiltration and reinfection, and inadequate obturation has been strongly correlated with higher failure rates [

6,

7]. Furthermore, follow-up radiographic examinations provide essential information on post-treatment healing, where the absence of pathological radiolucency remains a primary marker of successful therapy [

8].

The primary drawback of conventional radiographic techniques, including PR and OPGs, is their inability to capture the dental structures' three-dimensional (3D) complexity. The limitations of 2D imaging—such as geometric distortions, magnification inconsistencies, anatomical noise, and overlapping structures—often obscure critical diagnostic details [

9,

10,

11]. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has emerged as a superior imaging modality in endodontics to overcome these challenges. Unlike traditional radiographs, CBCT offers high-resolution 3D visualization of oral structures, facilitating the precise evaluation of complex anatomical features in multiple planes. With a spatial resolution of less than 0.1 mm, CBCT significantly enhances diagnostic and treatment accuracy and measurement precision in endodontic assessments [

12,

13].

CBCT has revolutionized dental imaging by providing detailed 3D reconstructions, improving diagnostic accuracy across various dental specialties, including endodontics, periodontology, orthodontics, and maxillofacial surgery [

5,

14,

15,

16]. Widely regarded as the gold standard for dental and bone imaging, CBCT enables highly detailed visualization and measurement of hard tissues, offering unparalleled clarity in reconstructing bone and dental structures [

17,

18]. Notably, CBCT achieves exceptional image resolution within a remarkably short scan time—often under 60 seconds—while significantly reducing radiation exposure (approximately 68 µSv) compared to conventional CT scans (600 µSv) [

19]. An emerging trend in advanced imaging involves integrating CBCT data with optical scans to refine 3D reconstructions, enhancing the accuracy of treatment planning [

20].

In endodontics, high-resolution imaging is essential for accurately assessing root canal morphology and surrounding periodontal structures. However, achieving this level of detail often requires increased radiation exposure. To balance diagnostic precision with radiation safety, small field-of-view (FOV) CBCT scans are recommended for endodontic applications [

14,

15]. A smaller FOV minimizes unnecessary radiation exposure to adjacent tissues while enhancing image quality by reducing scatter. Nevertheless, even minor patient movements during scanning can degrade image clarity. Studies suggest that CBCT units designed for seated or supine positioning provide better patient stability than standing units, a critical consideration for hybrid panoramic/CBCT machines [

21]. The rising popularity of hybrid units is likely due to their cost-effectiveness and multifunctionality, though this may come at the expense of slightly reduced image quality [

22].

Bone density evaluation is a crucial aspect of endodontic and implant treatment planning. Density values are measured in Hounsfield units (HU), which provide standardized assessments of bone quality. The Misch and Kircos D1-D5 classification is commonly used to categorize bone density based on HU values [

23]. In this classification system, bone density is categorized based on Hounsfield unit (HU) values, with D1 bone exceeding 1250 HU, D2 ranging from 850 to 1250 HU, D3 falling between 350 and 850 HU, D4 spanning 150 to 350 HU, and D5 defined by values below 150 HU. In dentate individuals, D1 bone is predominantly found in the anterior mandible, D2 in the anterior maxilla and posterior mandible, D3 in the posterior maxilla and mandible, and D4 primarily in the maxillary tuberosity [

24].

In the initial stages of apical periodontitis, periapical bone destruction may be minimal or obscured by surrounding anatomical structures, rendering it undetectable on conventional radiographs [

25]. This diagnostic limitation can lead to uncertainty, particularly in cases where clinical manifestations suggest pulp necrosis or irreversible pulpitis. CBCT-based imaging for the identification of apical periodontitis (CBCT-PAI) offers a highly accurate diagnostic tool, providing high-resolution images that reduce the likelihood of false-negative findings, minimize observer variability, and enhance the reliability of epidemiological studies, particularly those assessing the prevalence and severity of apical periodontitis [

26]. The benefits of using CBCT in endodontics are more accuracy in detecting periapical lesions in the early stages, bone density determinations, and healing progression [

3,

26].

However, the influence of bone density (D1-D5) on lesion resolution and the potential advantage of laser-assisted therapy in accelerating periapical healing remain underexplored.

Effective root canal disinfection influences endodontic treatment’s success, lesion resolution, and bone regeneration. The persistence of intracanal bacteria and periapical biofilms is the primary cause of endodontic treatment failure, leading to chronic periapical lesions such as cystic granulomas and chronic apical periodontitis [

27].

The follow-up assessment of periapical lesion healing was conducted following established guidelines, utilizing three-dimensional imaging protocols. Specifically, the CBCT Periapical Index (CBCT-PAI) proposed by Estrela et al. [

3] was applied, offering a standardized and reproducible method for evaluating periapical status. This system considers the size and location of the lesion concerning surrounding anatomical structures, such as the cortical bone and maxillary sinus, allowing for a more precise evaluation of lesion progression or resolution over time. CBCT-PAI ensures a comprehensive and objective approach to monitoring healing outcomes following endodontic treatment.

For the diagnostic accuracy and consistency in the follow-up analysis, specific criteria were used to differentiate between cystic granuloma and chronic apical periodontitis. Cystic granulomas were identified based on a combination of radiographic and histopathological features [

28,

29,

30]. Radiographically, these lesions appeared as well-defined radiolucencies with sclerotic borders, while histological examination confirmed the presence of an epithelial lining accompanied by chronic inflammatory infiltrate. In contrast, chronic apical periodontitis was diagnosed in cases presenting with persistent periapical radiolucency lacking cystic characteristics. These cases often included clinical signs such as tenderness, mild swelling, or sinus tract formation [

26]. Histopathologically, they were characterized by granulation tissue without an epithelial component. These diagnostic distinctions were critical in establishing an accurate baseline and ensuring reliable outcome evaluation during the follow-ups.

Although conventional chemical irrigation with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is the gold standard for microbial control, recent advances suggest that laser-assisted disinfection may enhance periapical healing by eliminating residual bacteria, promoting osteogenesis, and stimulating host immune responses [

31].

The histopathology of periapical lesions plays a crucial role in healing dynamics. Cystic granulomas, characterized by epithelial-lined cavities, tend to heal more rapidly than chronic apical periodontitis, which consists of fibrotic connective tissue with chronic inflammatory infiltrates [

32]. Additionally, bone density is a key determinant in the speed and completeness of healing, with low-density bone (D4-D5) exhibiting slower mineralization and a higher risk of persistent inflammation [

33].

This study explores the correlation between bone density, the duration time after endodontic obturation, and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) diagnostic accuracy. It also aims to evaluate the impact of laser-assisted disinfection combined with EDTA irrigation on periapical healing, as assessed by CBCT imaging over different time intervals (6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 2.5 years) and bone densities (D1-D5). Additionally, we seek to analyze healing differences between cystic granulomas and CAP, providing a deeper understanding of how lesion type and bone quality influence treatment outcomes.

Standard irrigation protocols involve sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for its broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to remove the smear layer and enhance dentinal tubule penetration [

34]. However, persistent biofilms and intracanal bacteria may delay periapical healing, necessitating adjunctive disinfection methods such as laser therapy. The histopathology of the investigated periapical lesions includes cystic granulomas, characterized by epithelial-lined cavities with inflammatory infiltration, and chronic apical periodontitis (CAP), composed of fibrotic connective tissue with chronic inflammatory cells. These pathological differences and variations in bone density (D1-D5) significantly influence the rate and extent of periapical healing.

By integrating CBCT-based analysis, lesion classification, and bone density evaluation, this study provides a comprehensive assessment of periapical healing by investigating the stages of bone regeneration following endodontic treatment of chronic periapical lesions and exploring the potential of laser therapy as a standard adjunctive technique in modern endodontics.

The null hypothesis (H₀) states that there is no significant difference in periapical healing between laser-assisted disinfection and conventional chemical irrigation. The alternative hypothesis (H₁) proposes that laser therapy enhances healing outcomes, particularly in low-density bone and chronic apical periodontitis cases.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the longitudinal healing of periapical lesions following non-surgical endodontic therapy, using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) at multiple time intervals: baseline (pre-treatment), 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 2.5 years. The study focused on two patient groups, differentiated by the disinfection protocol employed during endodontic therapy, to assess the impact of laser-assisted disinfection on periapical healing.

120 patients diagnosed with radiographically confirmed periapical lesions requiring endodontic treatment were included. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients without systemic conditions affecting bone metabolism, no prior root canal treatment on the target tooth, and no contraindications to laser therapy. Participants were divided into two groups: the Experimental Group (n = 60), which received irrigation with 17% EDTA followed by Er,Cr:YSGG laser disinfection, and the Control Group (n = 60), which underwent conventional chemical irrigation without laser adjuncts.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp., USA), including Chi-square tests to compare categorical variables (e.g., lesion healing rates between groups) and repeated measures ANOVA to evaluate changes in lesion size and CBCT-PAI scores over time.

A significance level was set at p < 0.05, with p < 0.01 indicating a highly significant difference.

A post-hoc power analysis was performed to evaluate whether the sample size (n = 60 per group) was sufficient to detect clinically meaningful differences, particularly for the primary outcome — CBCT-PAI score at 2.5 years. Using the observed means (Experimental: 0.7 ± 0.2; Control: 1.8 ± 0.4), the pooled standard deviation was approximated as 0.316, yielding a Cohen’s d of 3.48. Based on this effect size, a two-tailed test with α = 0.05 and n = 60 per group achieved a statistical power > 0.99, confirming that the sample was more than adequate to detect the observed differences.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Târgu Mureș (Decision No. 1885, 12 October 2022), and adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Diagnostic Criteria

Specific criteria were used to differentiate between cystic granuloma and chronic apical periodontitis. Radiographically, cystic granulomas appeared as well-defined radiolucencies with sclerotic borders, while histological examination confirmed the presence of an epithelial lining accompanied by chronic inflammatory infiltrate. In contrast, chronic apical periodontitis was diagnosed in cases presenting with persistent periapical radiolucency lacking cystic characteristics. These diagnostic distinctions were critical in establishing an accurate baseline and ensuring reliable outcome evaluation during the follow-up interval.

Endodontic Treatment Protocol

All patients underwent standardized mechanical and chemical debridement using a crown-down technique with nickel-titanium rotary files (Protaper Next, Dentsply Sirona, USA). Irrigation protocols included 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (20 mL/canal) during instrumentation, 17% EDTA (5 mL/canal) as a final rinse with one-minute passive ultrasonic activation, and 2% chlorhexidine as an adjunct antimicrobial agent. Intracanal medication with calcium hydroxide paste (Ca(OH)₂) was placed for 14 days. Root canals were obturated using the cold lateral condensation technique with Endoflas (Sanlor, Columbia), and the coronal access was sealed with Ketac Molar glass ionomer (3M/ESPE), followed by composite restoration using Filtek 250 (3M/ESPE) to ensure coronal integrity and prevent reinfection.

Laser Disinfection Protocol

In the Experimental Group, additional disinfection was performed with an Er,Cr:YSGG laser (Waterlase iPlus, BIOLASE, USA) set at 2780 nm wavelength, 1.5 W power, 140 µs pulse duration, and 20 Hz frequency. Laser application followed the EDTA irrigation, utilizing a radial firing tip inserted circumferentially within the canal to enhance bacterial reduction and penetration of dentinal tubules.

CBCT Imaging and Assessment

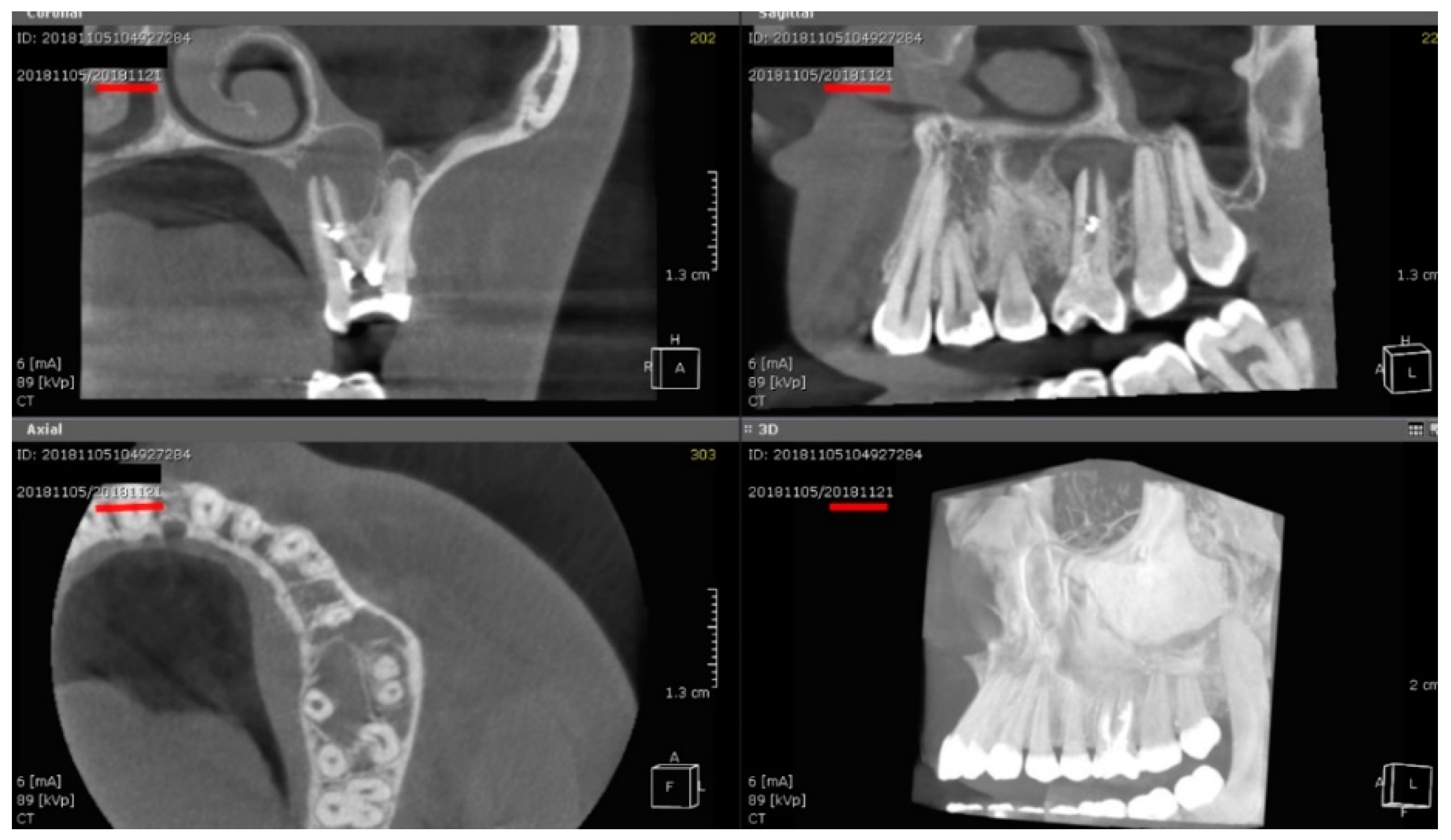

Periapical lesion healing was evaluated using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) at predefined time points: baseline (pre-treatment), 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 2.5 years post-treatment. Scans were acquired with the PaX-Uni3D CBCT system (TVAPANO04, VATECH, South Korea) using standardized parameters: 85 kV, 5 mA, and a 20-second exposure time. This setup provided high-resolution volumetric datasets optimized for the assessment of periapical pathology.

CBCT images were reconstructed and analyzed using Ez3D 2009 Plus software. For volumetric lesion measurement, semi-automated segmentation was performed in all three orthogonal planes (axial, sagittal, and coronal), followed by manual refinement of lesion boundaries to ensure anatomical accuracy. Lesion dimensions—buccolingual, mesiodistal, and apicocoronal—were recorded, and volumetric changes over time were calculated.

Two calibrated endodontists independently performed all imaging assessments, blinded to group allocation. Inter-observer agreement was quantified using Cohen’s kappa for categorical variables (CBCT-PAI scoring, κ = 0.87) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC = 0.91) for continuous volumetric measurements, indicating excellent reliability. Discrepancies exceeding 10% were resolved by consensus with a third blinded evaluator.

Primary outcome measures based on CBCT included:

- -

Volumetric lesion size: calculated from three-dimensional measurements across buccal-lingual, mesial-distal, and coronal-apical axes.

- -

CBCT Periapical Index (CBCT-PAI): scored according to Estrela et al. [

3] to assess lesion progression or regression.

- -

Bone density classification: assigned based on Misch’s D1–D5 system to evaluate healing potential relative to bone quality.

This standardized CBCT protocol allowed for accurate, reproducible, and blinded evaluation of periapical healing across all follow-up intervals.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of laser-assisted disinfection in conjunction with EDTA irrigation on periapical healing. The experimental group (laser + EDTA) demonstrated statistically significant improvements in periapical healing compared to the control group (chemical irrigation alone). The faster resolution of periapical lesions and a greater reduction in CBCT-PAI scores in the experimental group suggest that laser-assisted disinfection enhances periapical healing and bone regeneration. These findings agree with previous studies that demonstrated laser disinfection’s ability to eliminate intracanal biofilms and stimulate bone healing more effectively than conventional chemical irrigation alone [

35,

36].

The experimental group showed statistically significant improvements in lesion resolution, CBCT-PAI scores, and bone healing across all follow-up intervals. These findings align with previous research supporting laser therapy’s enhanced bactericidal and regenerative capabilities in endodontic treatment [

35,

36].

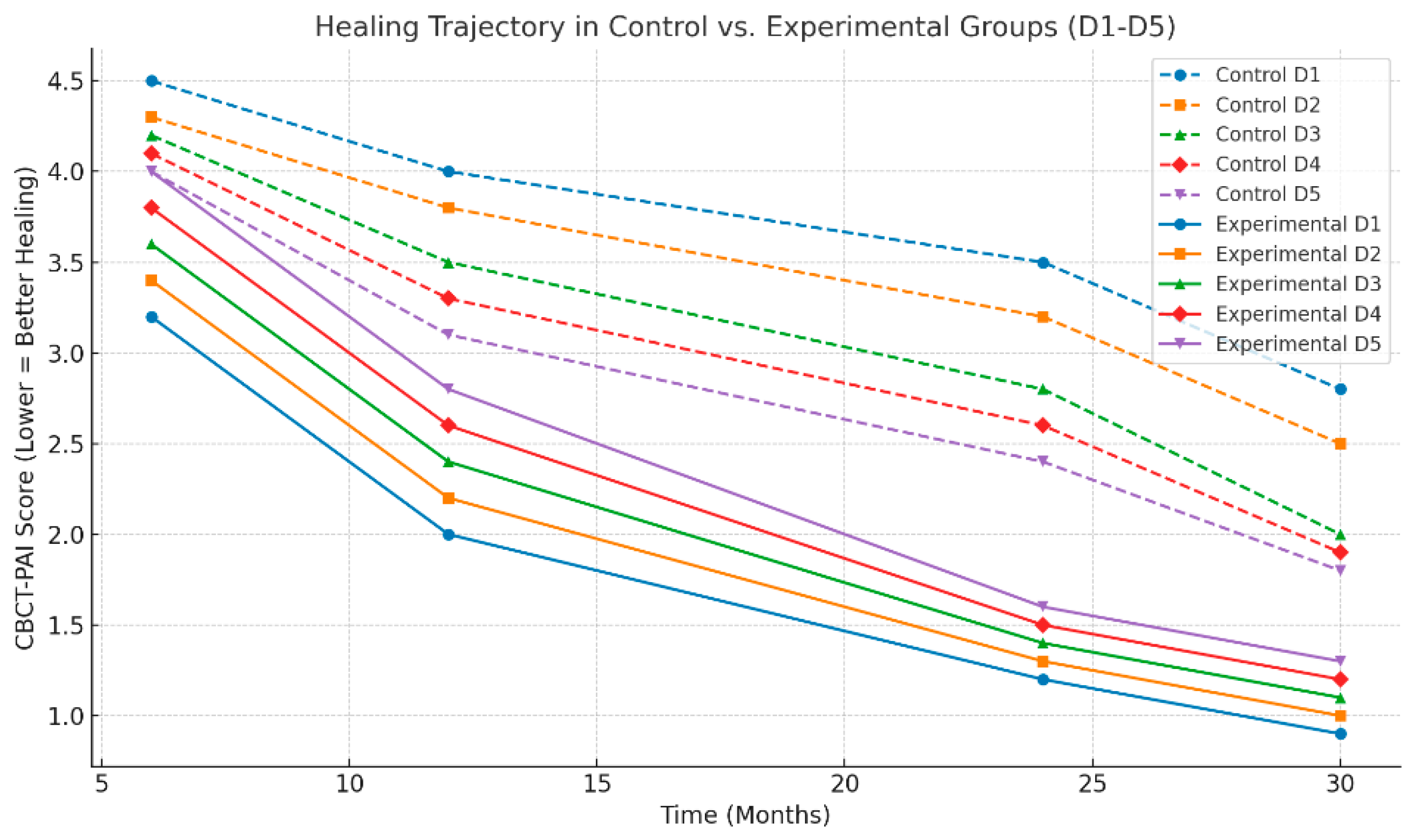

Nonetheless, both groups demonstrated progressive healing over time, reaffirming the efficacy of standard protocols utilizing NaOCl and EDTA [

37,

38]. The additional benefit observed in the laser-treated group was most pronounced in patients with chronic apical periodontitis (CAP) and those with low-density bone (D4–D5), where conventional methods are less effective. the healing trajectory in the control group was significantly slower, particularly in low-density bone (D4-D5), which suggests that the addition of laser therapy optimizes the natural healing process, particularly in challenging cases (

Figure 2).

The histological composition of periapical lesions determined the healing potential and rate following endodontic treatment. Cystic granulomas and chronic apical periodontitis (CAP) exhibit distinct tissue characteristics, which influence their response to therapeutic interventions, including laser-assisted disinfection and conventional chemical irrigation. Cystic granulomas are primarily composed of epithelial-lined cavities filled with inflammatory exudate and necrotic tissue, and they are generally more vascularized than CAP lesions [

38]. This increased vascularity enhances the immune response and facilitates faster healing [

39].

We observed that the experimental group, which received laser-assisted disinfection in conjunction with EDTA irrigation, achieved a significantly higher healing rate in cystic granulomas (89.5%) than the control group (68.4%). These findings align with previous research demonstrating that high-energy laser application enhances angiogenesis and osteogenesis, accelerating tissue regeneration and significantly improving the repair process in chronic inflammatory periapical lesions [

40].

On the other hand, chronic apical periodontitis is characterized by dense fibrotic tissue, chronic inflammatory infiltration, and persistent bacterial colonization within periapical biofilms [

40]. These characteristics render CAP lesions more resistant to resolution, as the lower vascularity and fibrotic nature of these lesions impede tissue regeneration and immune cell infiltration [

41]. Our study found that while healing in the control group was slower, the laser-treated group demonstrated a significant improvement in healing outcomes, with an 81.8% complete healing rate for CAP, compared to only 59.1% in the control group. This result supports earlier studies indicating that laser photobiomodulation can stimulate fibroblast proliferation and collagen remodeling, leading to more favorable healing outcomes in dense, fibrotic lesions [

42].

Bone density plays a pivotal role in the regenerative potential of the surrounding bone tissue and, consequently, the healing of periapical lesions [

40]. Laser-assisted disinfection also had a significant impact on healing in cases of compromised bone density.

The results showed that lesions in D1 and D2 (dense cortical and thick trabecular bone) demonstrated the highest healing rates, with little to no difference observed between the experimental and control groups. This finding aligns with the existing body of research, which suggests that structurally robust bone, with its abundant vascularity, offers an optimal environment for periapical healing [

43,

44]. In contrast, lesions in D3 and D4 bone (intermediate and sparse trabecular bone) exhibited a more pronounced difference in healing outcomes between the two groups, with the laser-treated group showing better resolution. This supports the hypothesis that laser therapy can stimulate osteoblastic activity and promote bone mineralization, even in less favorable bone types [

45].

Furthermore, the poorest healing rates were observed in D5 osteoporotic bone, consistent with the challenges of treating lesions in low-density bone, prone to prolonged periapical inflammation [

43]. These lesions tend to have slower healing trajectories due to reduced vascular supply and diminished osteogenic potential. However, even in D5 bone, the experimental group showed a statistically significant improvement in healing rates compared to the control group, suggesting that laser therapy provides a meaningful adjunct in cases of osteoporotic bone. Lower density means reduced osteoblastic activity, slower mineralization, and increased trabecular porosity, making lesion resolution more challenging.

Previous studies have indicated that lasers can enhance bone regeneration even in compromised bone structures by stimulating osteoblast differentiation, angiogenesis, and osteogenesis, which are critical for healing in osteoporotic conditions [

46].

The principles of canal disinfection are critical to endodontic success. In this study, the control group underwent conventional chemical irrigation with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and EDTA, both widely used for their antimicrobial and tissue-dissolving properties [

34]. NaOCl eliminates bacterial biofilms and necrotic tissue, while EDTA removes the smear layer, enhancing antimicrobial penetration. However, conventional irrigation has limitations, particularly in disrupting biofilms in deep-seated areas, highlighting the need for more advanced disinfection strategies [

34].

In contrast, laser-assisted disinfection offers several advantages, including deep penetration into dentinal tubules and a more effective reduction of bacterial endotoxins [

47]. Laser with EDTA can enhance the cleaning and disinfection process by creating a photoacoustic effect, which generates shockwaves that facilitate the removal of debris and bacteria from the root canal system [

48]. Laser therapy has also been shown to reduce bacterial endotoxins to levels not achievable with chemical irrigation alone, thereby reducing the risk of post-treatment flare-ups [

49]. These mechanisms are likely responsible for the superior outcomes observed in the experimental group, especially in cases of chronic apical periodontitis, which are notoriously difficult to treat with conventional methods [

47,

48,

49]. The Er,Cr:YSGG laser used in this study generates photoacoustic and photothermal effects that improve root canal disinfection. Unlike Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT), which primarily induces photobiomodulation at low intensities, the high-power Er,Cr:YSGG laser exerts direct bactericidal activity via cavitation and irrigation enhancement [

50].

While the results of this study are promising, some limitations must be acknowledged. Multicenter studies with long follow-ups would help validate the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term effects of laser therapy on periapical healing. The laser parameters (wavelength, power output, pulse duration) are critical to achieving consistent results. Further studies should explore the optimal settings for laser disinfection to maximize therapeutic outcomes. While CBCT provided valuable insights into healing trajectories, histological validation of the healing process would strengthen the conclusions of this study.

Although CBCT [

11,

13] allowed precise assessment of healing trajectories, this modality has known limitations, including increased radiation dose, high cost, and limited accessibility in certain healthcare settings. Its routine use in longitudinal endodontic monitoring may not be feasible or justified in all clinical contexts. Additionally, CBCT is contraindicated in certain populations, such as pregnant patients or those requiring strict radiation dose minimization [

17,

19].

Another critical consideration is the practicality of implementing laser-assisted therapy across diverse clinical environments. While effective, lasers—particularly high-power systems like the Er,Cr:YSGG used in this study—entail significant equipment costs, maintenance requirements, and operator training [

47,

49]. Despite the documented clinical benefits, such factors may limit widespread adoption, especially in low-resource settings [

48,

49,

50].

To address concerns of methodological transparency, this study employed blinded evaluators and demonstrated excellent inter-observer agreement (κ = 0.87, ICC = 0.91). However, we acknowledge that the study design could be further strengthened with multicenter enrollment, broader patient demographics, and direct histological confirmation of healing.

A post-hoc analysis based on the CBCT-PAI outcome at 2.5 years revealed a Cohen’s d of 3.48 and a power exceeding 0.99, strongly supporting the adequacy of the sample size. This mitigates concerns regarding type II errors and reinforces the robustness of the statistically significant findings. However, it is acknowledged that power estimates based on large effect sizes may overstate generalizability, and future studies with broader populations may help validate these outcomes under varied clinical settings.

Future research should aim to compare laser-assisted disinfection with other advanced adjuncts, such as ozone therapy, ultrasonic irrigation, and photodynamic therapy (PDT), to determine cost-effective and accessible alternatives with similar clinical outcomes [

51]. Moreover, further investigation into the molecular pathways activated by laser energy, including modulation of osteogenic markers and inflammatory mediators, will deepen our understanding of its biological mechanisms.