1. Introduction

Contemporary dentistry increasingly seeks minimally invasive procedures to reduce morbidity and accelerate patient recovery. Periapical surgery poses significant challenges due to the proximity of critical anatomical structures and the confined surgical field [

1,

2]. Technological advances such as magnification systems, microsurgical instruments, and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) have improved surgical precision [

3]. However, for less experienced operators, simultaneous interpretation of CBCT images during freehand execution remains challenging [

4]. Guided endodontics (GE), introduced in 2016, integrates CBCT, intraoral scanning, and Three-Dimensional (3D) modeling to digitally plan treatment and design computer-assisted surgical guides [

5,

6,

7]. The introduction of 3D printing technologies has further enhanced the precision and customization of these guides, enabling reproducible and patient-specific designs [

8]. Initially developed for calcified canals, GE quickly expanded to endodontic microsurgery, enhancing preoperative planning, accuracy, and safety [

9,

10]. Recent studies have further demonstrated improvements in precision and efficiency when using digital guides in apical microsurgery [

11,

12]. In addition, case reports and systematic reviews have highlighted their applicability in complex scenarios such as pulp canal obliteration [

13], traumatic injuries [

8], and overall clinical limitations [

10], reinforcing the potential of guided endodontics in contemporary practice. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the stability, accuracy, and operative time of apical trephinations performed with Exoplan, Blue Sky Plan, and the conventional technique in an in vitro model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This investigation was conducted as an experimental, comparative, in vitro study aimed at assessing the stability, accuracy, and operative time of trephinations in apical surgery using computer-assisted surgical guides. The experimental protocol was designed to ensure standardization and reproducibility of measurements while simulating clinical conditions as closely as possible.

2.2. Sample Selection

A total of 12 stereolithographic mandibular models were fabricated from anonymized cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) data provided for research purposes. Each model contained a complete permanent dentition, with anatomically correct morphology and dimensions.

Inclusion criteria: models with complete dentition, absence of periapical lesions, and adequate anatomical representation for guide seating. Exclusion criteria: models with structural defects, edentulism, or evidence of manufacturing inconsistencies that could compromise guide fit.

In total, 72 roots were available for trephination and distributed evenly into three experimental groups (n = 24 per group).

2.3. Imaging and Digital Workflow

Preoperative CBCT scans were acquired using a Hyperion X9 (Myray, Italy) at 120 kV, 8 mA, exposure time 15 s, 360° rotation, field of view (Ø11 × 5 cm), and voxel size of 75 μm. Digital impressions of the mandibular arches were obtained with an intraoral scanner PrimeScan (Dentsply Sirona, Germany) and exported as STL files.

The DICOM (CBCT) and STL (surface scan) files were superimposed using anatomical reference points (mesiobuccal cusp of molars, cusp tip of canines, and incisal edge of central incisors) to ensure accurate alignment.

2.4. Surgical Guide Design and Fabrication

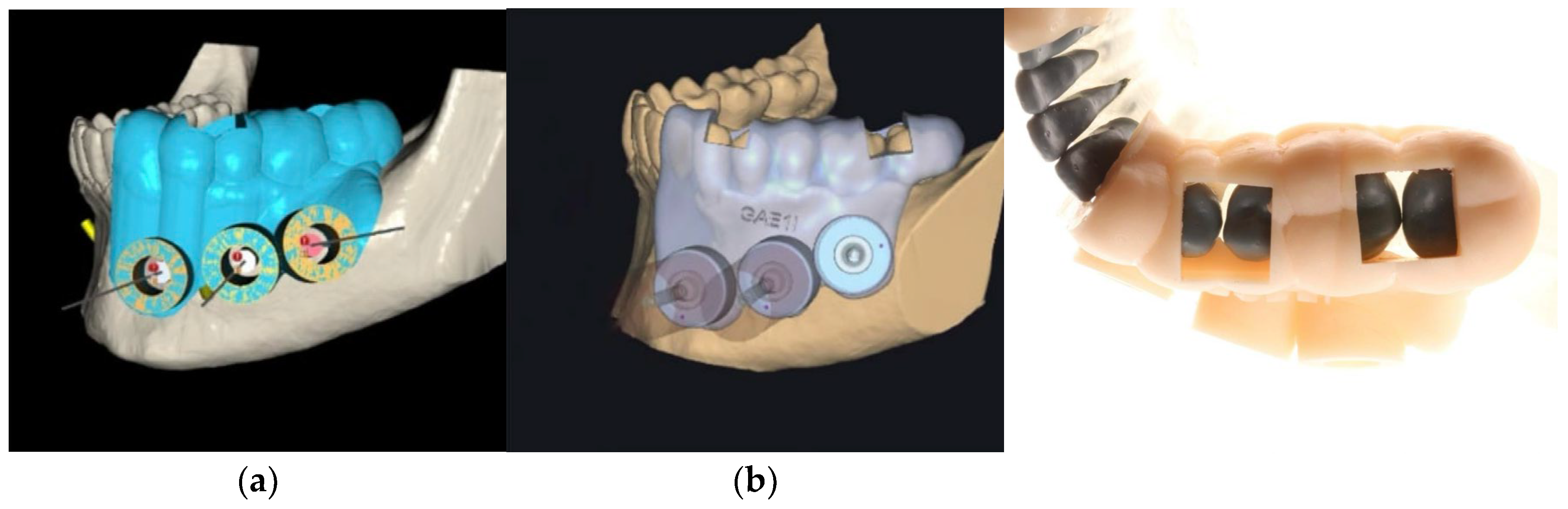

Two planning software systems were evaluated: Blue Sky Plan (Blue Sky Bio, USA) (

Figure 1 – a) and Exoplan (Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) (

Figure 1 - b). Each program was used to design guides incorporating:

Occlusal and buccal support zones for stability.

Verification windows (3 × 6 mm) on proximal ridges of premolars and molars.

A circular access window with a stainless-steel sleeve (inner diameter 4.25 mm), adapted to trephine burs of 4.20 mm (

Figure 1 – c).

A total of 16 guides were manufactured using a SprintRay Pro 3D printer (SprintRay Inc., USA) with UV-cured resin (Cmprodemaq, USA). The metallic sleeves were milled using CNC technology to ensure intimate adaptation to the trephine burs.

2.5. Experimental Groups

G1 (Control group): Conventional apical trephination without surgical guides.

G2 (Blue Sky Plan): Trephination with guides designed in Blue Sky Plan.

G3 (Exoplan): Trephination with guides designed in Exoplan.

Each group was tested on four mandibular models, resulting in 24 resections per group.

2.6. Trephination Procedure

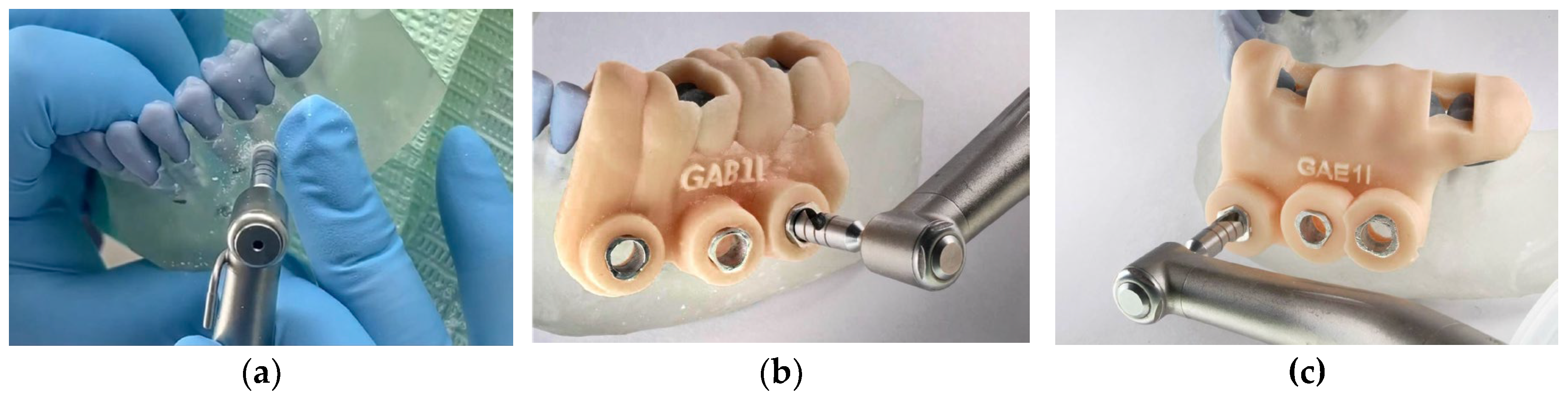

All procedures were carried out by three calibrated operators using a surgical motor NSK Surgic Pro (Japan) with trephine burs of 3.5 mm diameter, operated at 800 rpm and 40 N/cm torque under copious irrigation.

In the control group, osteotomies were performed manually based on preoperative CBCT measurements, calculating 3 mm above the apical third of the roots (

Figure 2 – a). In guided groups, sleeves directed the trephine path according to the pre-planned trajectory (

Figure 2 – b and c).

2.7. Outcome Measures

Stability: assessed by manual pressure in four directions (mesial, distal, buccal, posterior). Any displacement ≥0.5 mm was classified as failure.

Accuracy: measured as the linear deviation between the planned resection depth (3 mm) and postoperative CBCT superimposition, recorded in millimetres.

Operative time: defined as the interval (in seconds) from initial trephine contact to completion of resection.

2.8. Data Collection and Analysis

CBCT scans were acquired postoperatively and superimposed with preoperative data using Exocad software (Exocad GmbH, Germany). Two independent examiners performed duplicate measurements at one-week intervals to calculate intra-examiner reliability via intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results were tabulated in Excel and exported for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, confidence intervals) were calculated for each variable. Normality of distribution was tested using Shapiro–Wilk. Intergroup comparisons were made using Kruskal–Wallis for non-parametric data, ANOVA for parametric variables, and chi-square test for categorical outcomes. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Stability

In the control group (G1), no failures were observed. In the Blue Sky Plan group (G2), four out of eight guides exhibited mobility greater than 0.5 mm, corresponding to a failure rate of 50.0%. By contrast, only one guide in the Exoplan group (G3) showed instability (12.5%). Although chi-square analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences between groups (p > 0.05), the confidence intervals suggest a clear trend toward improved stability with Exoplan (

Table 1).

3.2. Accuracy

Deviation from the planned 3 mm apical resection was highest in the control group (mean = 1.16 ± 0.82 mm), followed by Blue Sky Plan (0.83 ± 0.58 mm). Exoplan demonstrated the greatest precision, with a mean deviation of only 0.17 ± 0.20 mm. The Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed significant differences between groups (p = 0.000). Overall, Exoplan not only reduced variability but also maintained resection lengths closer to the digital planning (

Table 2).

3.3. Operative Time

Trephination times were longest in the control group (mean = 154.6 ± 38.6 s), intermediate with Blue Sky Plan (127.5 ± 34.0 s), and shortest with Exoplan (106.5 ± 22.8 s). Statistical analysis (Kruskal–Wallis, p = 0.000) confirmed significant differences among all groups, indicating that higher precision did not translate into longer operative times; rather, the most accurate guides also yielded the fastest procedures (

Table 3).

3.4. Correlation Analysis

No significant correlation was found between the degree of deviation and operative time (p > 0.05), suggesting that improvements in accuracy are independent of procedural duration.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the stability, accuracy, and operative time of trephinations in guided apical surgery using Blue Sky Plan and Exoplan software compared with conventional freehand technique. The main findings were that Exoplan achieved superior performance across all evaluated parameters, while Blue Sky Plan showed intermediate results and freehand surgery was the least precise and most time-consuming.

4.1. Stability of Surgical Guides

Although statistical significance was not reached (p > 0.05), Exoplan demonstrated fewer failures compared with Blue Sky Plan (12.5% vs. 50.0%), indicating enhanced guide seating and adaptation (

Table 1). This finding aligns with Strbac et al. [

14] and Giacomino et al. [

4], who reported that guide design features, such as verification windows and optimized support surfaces, contribute to better clinical stability. The observed failures with Blue Sky Plan may be attributed to its less sophisticated interface for sleeve positioning, resulting in increased tolerance during trephination.

4.2. Accuracy of Apical Resection

Exoplan guides showed significantly greater accuracy (mean deviation 0.17 mm) compared with Blue Sky Plan (0.83 mm) and freehand control (1.16 mm) (

Table 2). These values are consistent with recent cadaveric and in vitro studies, which reported deviations between 0.1 and 0.3 mm using digitally designed guides [

5,

11,

15]. In contrast, freehand apical resections frequently exceeded 1 mm deviation, corroborating previous observations by Connert et al. [

16], Peng et al. [

15] and Huth et al. [

17], who confirmed the reproducibility of these outcomes in a multicenter in vitro setting. Importantly, the reduced variability in the Exoplan group highlights the role of advanced software in integrating DICOM and STL data with minimal registration error.

4.3. Operative Time Efficiency

Procedural time was shortest in the Exoplan group (106.5 s) compared with Blue Sky Plan (127.5 s) and freehand control (154.6 s) (

Table 3). These results indicate that improved accuracy does not compromise efficiency; rather, optimized guide design accelerates surgical steps. Similar reductions in operative time were described by Zhao et al. [

12] and Cabezón et al. [

18], while recent reports emphasize the complementary role of dynamic navigation systems [

11,

19,

20], which may provide additional flexibility though with higher training requirements. Zubizarreta-Macho et al. [

21] also demonstrated comparable accuracy between dynamic and static navigation, reinforcing that clinical choice often depends on operator expertise and available infrastructure.

4.4. Correlation Between Accuracy and Time

Interestingly, no significant correlation was observed between deviation and operative time, suggesting that the accuracy of Exoplan guides is independent of procedural speed. This contrasts with the common assumption that greater precision requires longer operating times, and reinforces the clinical applicability of digital workflows.

4.5. Clinical Implications and Limitations

The findings highlight the clinical potential of Exoplan in improving safety and predictability in apical surgery, particularly for less experienced clinicians. However, the study was conducted in vitro, without the influence of biological variables such as bleeding, soft tissue interference, or patient movement, which could affect guide seating and visibility. Moreover, the relatively small sample size limits the statistical power, especially for categorical variables such as stability. Furthermore, recent advances in open-frame guide concepts and hybrid navigation techniques [

12] [

18] suggest that ongoing innovation may overcome some of the limitations encountered in static workflows.

Future research should focus on clinical validation with larger samples, and comparative trials between static and dynamic navigation to further define their respective advantages. Hybrid workflows, integrating static precision with dynamic flexibility, may represent the next step in guided microsurgery.

5. Conclusions

Exoplan surgical guides demonstrated superior stability, accuracy, and efficiency compared with Blue Sky Plan and conventional freehand techniques in guided apical surgery. These findings support the clinical adoption of digitally designed guides to enhance safety and predictability. Further clinical trials with larger samples are required to validate these results under real operative conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Romero.S. and Peñaherrera.MS.; methodology, Peñaherrera.MS.; software, Romero.S; validation, Romero.S, Peñaherrera.MS and Valverde.H.; formal analysis, Romero.S. Valverde H; investigation, Romero.S; resources, Romero.S and Valverde H; data curation, Romero.S and Peñaherrera MS.; writing—original draft preparation, Valverde. H.; writing—review and editing, Peñaherrera. MS, Valverde. H; visualization, Romero. S and Valverde. H; supervision, Valverde. H.; project administration, Peñaherrera. MS.; funding acquisition, Romero.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for the Approval of Thesis Proposals of the Postgraduate Program in Dentistry at Universidad de los Hemisferios, Quito, Ecuador (protocol code CEUHE25-40, approval date: 5 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

CBCT = Cone-Beam Computed Tomography

GE = Guided Endodontics

SGE = Static Guided Endodontics

DGE = Dynamic Guided Endodontics

ICC = Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

SD = Standard Deviation

CI = Confidence Interval

ANOVA = Analysis of Variance

3D = Three-Dimensional

References

- Jain, S.D.; Saunders, M.W.; Carrico, C.K.; Jadhav, A.; Deeb, J.G.; Myers, G.L. Dynamically Navigated versus Freehand Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using Simulated Calcified Canals. J Endod 2020, 46, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Wealleans, J.; Ray, J. Endodontic applications of 3D printing. Int Endod J 2018, 51, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, F.C.; Kratchman, S.I. Present status and future directions: Surgical endodontics. Int Endod J 2022, 55 Suppl 4, 1020–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomino, C.M.; Ray, J.J.; Wealleans, J.A. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Novel Approach to Anatomically Challenging Scenarios Using 3-dimensional-printed Guides and Trephine Burs-A Report of 3 Cases. J Endod 2018, 44, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehnder, M.S.; Connert, T.; Weiger, R.; Krastl, G.; Kuhl, S. Guided endodontics: accuracy of a novel method for guided access cavity preparation and root canal location. Int Endod J 2016, 49, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connert, T.; Zehnder, M.S.; Amato, M.; Weiger, R.; Kuhl, S.; Krastl, G. Microguided Endodontics: a method to achieve minimally invasive access cavity preparation and root canal location in mandibular incisors using a novel computer-guided technique. Int Endod J 2018, 51, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde Haro, H.P.; Quille Punina, L.G.; Erazo Conde, A.D. Guided Endodontic Treatment of Mandibular Incisor with Pulp Canal Obliteration following Dental Trauma: A Case Report. Iran Endod J 2024, 19, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambarini, G.; Ropini, P.; Piasecki, L.; Costantini, R.; Carneiro, E.; Testarelli, L.; Dummer, P.M.H. A preliminary assessment of a new dedicated endodontic software for use with CBCT images to evaluate the canal complexity of mandibular molars. Int Endod J 2018, 51, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krastl, G.; Weiger, R.; Ebeleseder, K.; Galler, K. Present status and future directions: Endodontic management of traumatic injuries to permanent teeth. Int Endod J 2022, 55 Suppl 4, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rabie, C.; Torres, A.; Lambrechts, P.; Jacobs, R. Clinical applications, accuracy and limitations of guided endodontics: a systematic review. Int Endod J 2020, 53, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.W.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Hu, K.S.; Kim, E. Accuracy of 3-dimensional surgical guide for endodontic microsurgery with a new design concept: A cadaver study. Int Endod J 2025, 58, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xie, W.; Li, T.; Wang, A.; Wu, L.; Kang, W.; Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Tang, X.; Xie, S. New-designed 3D printed surgical guide promotes the accuracy of endodontic microsurgery: a study of 14 upper anterior teeth. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 15512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudevan, A.; Santosh, S.S.; Selvakumar, R.J.; Sampath, D.T.; Natanasabapathy, V. Dynamic Navigation in Guided Endodontics - A Systematic Review. Eur Endod J 2022, 7, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strbac, G.D.; Schnappauf, A.; Giannis, K.; Moritz, A.; Ulm, C. Guided Modern Endodontic Surgery: A Novel Approach for Guided Osteotomy and Root Resection. J Endod 2017, 43, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Sun, Y.C.; Liang, Y.H. Accuracy of root-end resection using a digital guide in endodontic surgery: An in vitro study. J Dent Sci 2021, 16, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connert, T.; Krug, R.; Eggmann, F.; Emsermann, I.; ElAyouti, A.; Weiger, R.; Kuhl, S.; Krastl, G. Guided Endodontics versus Conventional Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using 3-dimensional-printed Teeth. J Endod 2019, 45, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, K.C.; Borkowski, L.; Liebermann, A.; Berlinghoff, F.; Hickel, R.; Schwendicke, F.; Reymus, M. Comparing accuracy in guided endodontics: dynamic real-time navigation, static guides, and manual approaches for access cavity preparation - an in vitro study using 3D printed teeth. Clin Oral Investig 2024, 28, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabezon, C.; Aubeux, D.; Pérez, F.; Gaudin, A. 3D-Printed Metal Surgical Guide for Endodontic Microsurgery (a Proof of Concept). Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D, G.T.; Saxena, P.; Gupta, S. Static vs. dynamic navigation for endodontic microsurgery - A comparative review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2022, 12, 410–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Reis, E.; Marques, J.A.; Falacho, R.I.; Palma, P.J. Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques-A Literature Review. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta-Macho, A.; Munoz, A.P.; Deglow, E.R.; Agustin-Panadero, R.; Alvarez, J.M. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation Compared to Computer-Aided Static Procedure for Endodontic Access Cavities: An in Vitro Study. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).