1. Introduction

Apicoectomy is a well-established procedure in oral and maxillofacial surgery for treating persistent periapical infections, particularly when conventional endodontic therapy or endodontic retreatment fails[

1,

2]. The number of resections performed has remained consistent over the last few years. In Germany, approximately 521,000 root canal resections were reported to state health insurance funds in 2022[

3]. Traditionally, this procedure is typically performed under direct visualization, ideally with optical magnification aids, which can increase precision and reduce the risk of damage to adjacent anatomical structures4. Potentially damaged structures include the inferior alveolar nerve, neighboring roots, and the maxillary sinus; damage to these can cause altered sensation, numbness, sinus infections, and necessitate further treatments of neighboring teeth[

5,

6].

Conventional two-dimensional radiology is the standard for diagnosing and planning the therapy of endodontic lesions but is limited, especially in complex cases, due to visualization constraints [

7,

8] The introduction of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) in the early 1970s revolutionized preoperative planning by providing three-dimensional imaging of the surgical site

9. In the context of endodontic treatment, this allowed for improved localization of the apex, better preoperative visualization, enhanced diagnosis, and more accurate assessment of surrounding anatomical structures, such as the maxillary sinus or inferior alveolar nerve, compared to conventional 2D imaging[

7,

8].

This development has opened a new approach to endodontic microsurgery with static and dynamic navigation systems that have been successfully used in implant dentistry. Static navigation, by utilizing preoperatively fabricated surgical guides, offers enhanced precision in osteotomy and root resection but lacks intraoperative flexibility[

10]. Furthermore, dynamic navigation systems provide real-time tracking of surgical instruments based on CBCT data with optical tracking, which can improve intraoperative accuracy and flexibility.

Recent studies have demonstrated that dynamic navigation systems (DNS) reduce access cavity volume, minimize bone removal, and enhance resection accuracy, thereby preserving more healthy tissue while ensuring complete removal of the infected apex[

11,

12,

13]. Despite these advantages, dynamic navigation is not yet fully implemented in routine clinical practice, primarily due to its demanding preoperative planning, the need for specialized equipment, and the associated learning curve for surgeons[

14].

This study aims to evaluate whether the use of dynamic navigation, compared to a conventionally performed apicoectomy, can lead to improvements in accuracy, operation time, bone loss, and incision guidance. The apicoectomy was performed in a split-mouth design, either conventionally freehand or with the support of a dynamic navigation system, and was carried out by trained oral, maxillofacial, and facial surgeons. The hypothesis is that dynamic navigation allows for a minimized surgical approach, less damage to surrounding critical structures, and a better surgical outcome in terms of resected root length.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Ten experienced oral and maxillofacial surgeons from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, participated in the study. Each performed both conventional and navigated apicoectomies on standardized models. Every surgeon performed two apicoectomies on the mesial root of the first molar per jaw, one using conventional techniques and one using dynamic navigation. The order of procedures was randomized to minimize learning bias. In the conventional group, the surgical procedure followed standard microsurgical principles. A semilunar flap was raised to expose the apical region, followed by an osteotomy using a high-speed handpiece with diamond burs. The root apex had to be resected at a 90° angle, and the simulated cavity with granulation tissue had to be removed. In the navigated group, the procedure incorporated real-time tracking, where the patient-specific surgical plan was loaded into the DENACAM® system (mininavident AG, Basel, Switzerland). An optical tracking system registered the instruments with a registration tool and displayed the instrument on the computer screen relative to the CBCT-derived three-dimensional coordinates. Surgeons performed the osteotomy and root-end resection following real-time guidance displayed on the monitor. The remaining procedural steps were identical to the conventional method.

The model depicted the roots of upper and lower first molar teeth and the roots of the second premolar embedded in a realistic bone model that replicated human maxillary and mandibular anatomy. The model was 3D printed by MedNerva GmbH (Limburg, Germany) (

Figure 1). The selection criteria for the model ensured homogeneity in tooth positioning, root morphology, and surrounding bone density to eliminate potential confounding variables.

Preoperative imaging was performed using the CBCT OP 3D Vision (KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach, Germany) to obtain high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging of the surgical site. The CBCT scans provided important anatomical details, including the position of the root apex, adjacent structures, and bone thickness, allowing precise planning of the apicoectomy procedure. Furthermore, the surface of the model was scanned with the object scanner Dental Wings® 7SERIES (Dental Wings GmbH, Chemnitz, Germany). For the dynamic navigation group, the CBCT and model scan data were imported into the coDiagnostiX® software (Dental Wings GmbH, Chemnitz, Germany), where a virtual surgical plan was created simulating an implantation. This plan included the optimal osteotomy trajectory and targeted resection depth. The marker for the DENACAM® system (mininavident AG, Basel, Switzerland) was virtually positioned, and a custom tray was fabricated using a resin printing process with a Formlabs 2 3D printer (Formlabs GmbH, Berlin, Germany) to serve as a marker holder (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

A positive ethics vote from the Ethics Committee of Kiel University (D 564/20) was received. All participating surgeons provided informed consent regarding data collection and analysis.

2.2. Variables and Data Collection Methods

Several parameters were assessed to evaluate the accuracy and efficiency of both techniques. Postoperative CBCT scans were acquired to compare the conventional versus guided resection in terms of resected root length and osteotomized volume, measured using the image analysis software 3D Slicer (

https://www.slicer.org/, Version 5.6.1 [Computer Software] [

15,

16]). The total operation time was recorded from flap incision to completed resection. The surgical incision was measured in vertical and horizontal length, as were damaged neighboring structures like the inferior alveolar nerve, neighboring roots, or the maxillary sinus. It was considered whether there was a non-bone-supported incision or if there was a total resection of the planned root or damage to the root surface above the planned resection.

2.3. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using Jamovi (The jamovi project (2024), jamovi, Version 2.6.2 [Computer Software], Australia, Sydney[

17]). For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were reported as the mean ± standard deviation and as frequencies for categorical variables. Group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test for normally distributed parameters with homogeneity of variances. If the assumption of variance homogeneity was violated, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data, and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The evaluated parameters were: operation time from incision to successful apicoectomy, vertical and horizontal incision length, whether the suture was bone-supported, resected root length, resected bone volume, and damaged root surface above the planned resection or damaged neighboring structures.

3. Results

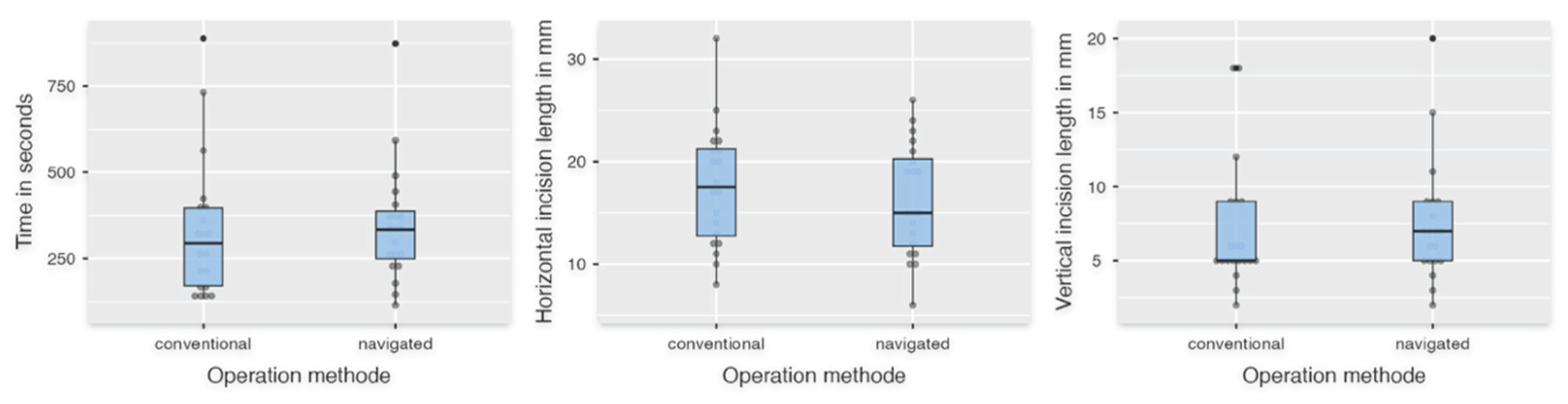

Forty apicoectomies were performed by ten surgeons (nnavigated = 20, nconventional = 20). For the descriptive statistics, mean values and standard deviations are shown in

Table 1. Student’s t-test was used to analyze the parameters "Resected bone volume" (

Figure 4) and "Horizontal incision length" (

Figure 5). The resected bone volume with the navigated operation method was statistically significantly less than with the conventional method (p < 0.001) and showed a strong effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.342) (

Table 2). For "Horizontal incision length," there was no significant difference between FH and DNS (p = 0.442). The parameters "Time in seconds," "Length of removed apex," and "Vertical incision length" did not show a normal distribution and were therefore evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. The descriptive statistics showed fulfillment of the specification for the variable "Length of removed apex" of 2-3 mm of the root apex with 2.63 mm ± 0.44 mm compared to the conventional group with 3.21 mm ± 1.11 mm (

Table 1, 2;

Figure 4). However, no significant difference was evaluated for "Time in seconds," "Length of removed apex," and "Vertical incision length" (pTime in seconds = 0.499; pLength of removed apex = 0.054; pVertical incision lengdth = 0.442) (

Figure 5).

The nominal scaled parameters "Completely removed root apex," "Bone-supported incision," and "Damaged root surface above" were evaluated with the Chi-square test with continuity correction and showed no statistical significance between the operation methods (pCompletely removed root apex = 0.730; pBone supported incision = 0.514; pDamaged root surface above = 0.405).

4. Discussion

Apicoectomy, a well-established surgical procedure following unsuccessful conservative endodontic treatment, has evolved into a minimally invasive technique utilizing magnification aids and microscopes [

4]. Visualization and preoperative planning have been enabled by the subsequent development of guided surgery using 3D imaging[

18]. As a result, it is now possible to choose between static and dynamic navigation. Navigation systems – developed for the oral cavity – have been used for dental implantation, with results comparable to, and in some cases better than, those achieved with conventional surgical methods[

10,

19,

20]. For the implementation of a dynamically navigated digital workflow, the frame structures, corresponding devices, and 3D datasets must be created using CBCT and intraoral scanners. The primary objective was to facilitate navigation during dental implantation surgery. However, its applications extended to biopsies in cases of complex surgical anatomy or endodontic surgery[

14,

19,

21,

22,

23].

For apicoectomy, both surgical approaches are described. For static navigation, Hawkins et al. described that individually planned and printed surgical guides reduced surgical time, resected less volume, and improved angulation, and Buniang et al. showed similar results to conventional root-end resection in a retrospective study[

24,

25]. Limitations in intraoperative adaptation were described, and the template had to be adequately supported dentally for high precision, but it has proven to work well in clinical cases[

26,

27,

28].

The present study demonstrated the advantages of navigated apicoectomy using the DENACAM® system (mininavident AG, Basel, Switzerland) in a patient-like setting with a difficult-to-view surgical site. The access volume was significantly reduced, and the required removal of 2-3 mm of the root apex could be demonstrated with greater precision than with the conventional method. These results were comparable to the current state of research. Aldahmash et al. compared 24 apicoectomies utilizing DNS and 24 conventional apicoectomies in a cadaver study and showed significantly fewer deviations, angular deflection, reduced cavity volume, and shorter operating duration[

11]. Similar results were found in the study by Dianat et al. for angular deflection, operating time, and linear deviation. Noteworthy was the subgroup with a thicker buccal cortical plate of more than 5 mm, which showed significantly lower accuracy and longer operating time in the conventional cohort, but not in the DNS cohort[

12]. An advantage of our study was that the same approach was used for both resection procedures, with conventional surgical drills rather than pilot drills and then conical bone drills with a diameter of 3.5 mm or 4.2 mm, as in the studies described above.

Obligatory for navigated surgery is 3D imaging. The need for 3D imaging increases the patient's exposure to radiation and must be critically scrutinized, even if studies showed that CBCT enabled better diagnosis of apical infections[

7,

8,

29]. Antony et al. described in a systematic review that CBCT had the highest accuracy in detecting osteolysis of the bone due to periapical lesions[

30]. In the study by Chugal et al., 442 scans evaluated 526 teeth, and CBCT led to a changed diagnosis of periapical lesions in 21% and a changed treatment plan in 69%[

7]. Guided apicoectomy can assist with the limited field of view and more complicated handling situations in the molar region. To establish dynamic guidance systems, it is necessary to evaluate the practicality of the systems in a simulated clinical setting. Actual studies with human cadaver heads have shown good applicability as described above. In this study, we attempted to simulate a clinical environment. The designed and printed model allowed for a highly patient-like setup due to its design with patient-like jaw and dental anatomy, hard and soft tissues, fitting in a simulation dummy, and printed anatomical structures such as the maxillary sinus and adjacent roots. However, because it was produced from a plastic material, and due to the higher temperature at the tip of the bur, it was sometimes difficult to visually distinguish between the printed root and the bone material. Von Arx et al. showed that minimally invasive surgery is favorable for patient and tooth outcomes[

4]. However, their focus was more on the development of tools like piezoelectric surgery and optical magnifiers. We need further prospective in vivo studies to investigate if a smaller volume defect and precise root resection influence the survival rate of treated teeth and the postoperative situation, such as pain and swelling. Important for the survival of teeth after apical surgery is the retrograde filling[

31]. In this study, we focused primarily on the handling and outcome of dynamic navigated surgery. However, a smaller cavity can cause problems for curettage, hemostasis, and retrograde filling. Only the study from Aldahmash et al. (2022) showed the full operation with retrograde filling[

11]. Due to the tapered 3.5 mm bur used, the cavity was always the same size and was suitable for retrograde treatment. Furthermore, artificial intelligence represents a new development. It can assist with the diagnosis of periapical lesions, tooth cracks, and locating critical structures like the mandibular nerve[

32,

33,

34]. The development of robot-assisted surgery, higher computer processing power, and artificial intelligence leads to the first fully automated dental surgeries[

35,

36]. Liu et al. showed in a study that a robotic system was significantly more accurate during apicoectomy than dynamic navigation in terms of platform and global apex deviation and angular deflection, and the compared operative time was longer with the robotic procedure than with the DNS procedure [

37]. However, one problem with the robotic system is that it can only perform a resection. It is not possible to perform the entire procedure from incision to suturing. So, even though artificial intelligence and robotics in surgery are promising, we need more research and development. In summary, navigated surgery offers a more predictable outcome, a lower risk of complications, and greater safety, particularly for less experienced surgeons, but these benefits come at the cost of more planning compared to conventional surgery[

13,

14,

18,

23].

5. Conclusions

Dynamic navigation for apicoectomy can offer an alternative to conventional techniques, particularly in cases requiring high precision. The improved accuracy and reduced bone loss suggest potential clinical benefits. However, the routine clinical implementation of dynamic navigation remains limited due to the extensive preoperative planning required. The necessity for additional imaging, software-based planning, and intraoperative calibration increases complexity and cost, restricting its widespread use in daily clinical practice. Further studies are needed to assess the clinical workflow, optimize its efficiency, and evaluate clinical outcomes to enhance its feasibility for broader application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K. and J.S..; methodology, P.K..; software, C.H..; validation, P.K. J.S. and J.Wa.; formal analysis, P.K., C.H..; investigation, P.K., J.S,C.H..; resources, C.H. .; data curation, P.K..; writing—original draft preparation, P.K., J.S., .; writing—review and editing, P.K., J.Wi, J.S.,A.G..; visualization, P.K..; supervision, J. Wi..; project administration, J.S., J.Wa.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

A positive ethics vote from the Ethics Committee of Kiel University (D 564/20) was received. All participating surgeons provided informed consent regarding data collection and analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBCT |

Cone-beam computed tomography |

| DNS |

Dynamic navigation systems |

| FH |

Free-handed |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Dioguardi M, Stellacci C, La Femina L, et al. Comparison of Endodontic Failures between Nonsurgical Retreatment and Endodontic Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. Medicina. 2022;58(7):894. [CrossRef]

- Setzer FC, Shah SB, Kohli MR, Karabucak B, Kim S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature--part 1: Comparison of traditional root-end surgery and endodontic microsurgery. J Endod. 2010;36(11):1757-1765. [CrossRef]

- Kassenzahnärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KZBV). Statistische Basisdaten Zur Vertragszahnärztlichen Versorgung 2023.; 2023. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.kzbv.de/kzbv2023-jahrbuch-web-ohnegoz.media.9083f41ba25e0a1dfbdf6b349f333c2b.pdf.

- von Arx T. Apical surgery: A review of current techniques and outcome. Saudi Dent J. 2011;23(1):9-15. [CrossRef]

- Minji Kang, Euiseong Kim. Healing Outcome after Maxillary Sinus Perforation in Endodontic Microsurgery. ResearchGate. Published online October 22, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Von Arx T, Bolt S, Bornstein MM. Neurosensory Disturbances After Apical Surgery of Mandibular Premolars and Molars: A Retrospective Analysis and Case-Control Study. Eur Endod J. 2021;6(3):247-253. [CrossRef]

- Chugal N, Assad H, Markovic D, Mallya SM. Applying the American Association of Endodontists and American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology guidelines for cone-beam computed tomography prescription: Impact on endodontic clinical decisions. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2024;155(1):48-58. [CrossRef]

- Surya S, Barua AND, Magar SP, Magar SS, Rela R, Chhabada AK. Comparative Assessment of the Efficacy of Two-Dimensional Digital Intraoral Radiography to Three-Dimensional Cone Beam Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Periapical Pathologies. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2022;14(Suppl 1):S1009-S1013. [CrossRef]

- D’haese J, Ackhurst J, Wismeijer D, De Bruyn H, Tahmaseb A. Current state of the art of computer-guided implant surgery. Periodontology 2000. 2017;73(1):121-133. [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Albiol J, Barootchi S, Salomó-Coll O, Wang HL. Advantages and disadvantages of implant navigation surgery. A systematic review. Ann Anat. 2019;225:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Aldahmash SA, Price JB, Mostoufi B, et al. Real-time 3-dimensional Dynamic Navigation System in Endodontic Microsurgery: A Cadaver Study. J Endod. 2022;48(7):922-929. [CrossRef]

- Dianat O, Nosrat A, Mostoufi B, Price JB, Gupta S, Martinho FC. Accuracy and efficiency of guided root-end resection using a dynamic navigation system: a human cadaver study. Int Endod J. 2021;54(5):793-801. [CrossRef]

- Gambarini G, Galli M, Stefanelli LV, et al. Endodontic Microsurgery Using Dynamic Navigation System: A Case Report. J Endod. Published online September 9, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Spille J, Bube N, Wagner J, et al. Navigational exploration of bony defect mimicking a solid lesion of the mandible compared to conventional surgery by young professionals. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. Published online August 3, 2023:101588. [CrossRef]

- 3D Slicer (Version 5.6.1) [Computer Software]. https://www.slicer.org/.

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an Image Computing Platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1323-1341. [CrossRef]

- The jamovi project. The jamovi (Version 2.6) [Computer Software]. Accessed June 10, 2024. https://www.jamovi.org/.

- Mezger U, Jendrewski C, Bartels M. Navigation in surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(4):501-514. [CrossRef]

- Spille J, Jin F, Behrens E, et al. Comparison of implant placement accuracy in two different preoperative digital workflows: navigated vs. pilot-drill-guided surgery. Int J Implant Dent. 2021;7:45. [CrossRef]

- Varga Jr. E, Antal M, Major L, Kiscsatári R, Braunitzer G, Piffkó J. Guidance means accuracy: A randomized clinical trial on freehand versus guided dental implantation. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2020;31(5):417-430. [CrossRef]

- Block MS, Emery RW, Cullum DR, Sheikh A. Implant Placement Is More Accurate Using Dynamic Navigation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(7):1377-1386. [CrossRef]

- Somogyi-Ganss E, Holmes HI, Jokstad A. Accuracy of a novel prototype dynamic computer-assisted surgery system. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015;26(8):882-890. [CrossRef]

- Spille J, Helmstetter E, Kübel P, et al. Learning Curve and Comparison of Dynamic Implant Placement Accuracy Using a Navigation System in Young Professionals. Dent J (Basel). 2022;10(10):187. [CrossRef]

- Buniag AG, Pratt AM, Ray JJ. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Retrospective Outcomes Assessment of 24 Cases. J Endod. 2021;47(5):762-769. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins TK, Wealleans JA, Pratt AM, Ray JJ. Targeted endodontic microsurgery and endodontic microsurgery: a surgical simulation comparison. International Endodontic Journal. 2020;53(5):715-722. [CrossRef]

- Ahn SY, Kim NH, Kim S, Karabucak B, Kim E. Computer-aided Design/Computer-aided Manufacturing-guided Endodontic Surgery: Guided Osteotomy and Apex Localization in a Mandibular Molar with a Thick Buccal Bone Plate. J Endod. 2018;44(4):665-670. [CrossRef]

- Giacomino CM, Ray JJ, Wealleans JA. Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Novel Approach to Anatomically Challenging Scenarios Using 3-dimensional-printed Guides and Trephine Burs-A Report of 3 Cases. J Endod. 2018;44(4):671-677. [CrossRef]

- Martinho FC, Rollor C, Westbrook K, et al. A Cadaver-based Comparison of Sleeve-guided Implant-drill and Dynamic Navigation Osteotomy and Root-end Resections. Journal of Endodontics. 2023;49(8):1004-1011. [CrossRef]

- Kunzendorf B, Naujokat H, Wiltfang J. Indications for 3-D diagnostics and navigation in dental implantology with the focus on radiation exposure: a systematic review. International Journal of Implant Dentistry. 2021;7(1):52. [CrossRef]

- Antony DP, Thomas T, Nivedhitha M. Two-dimensional Periapical, Panoramic Radiography Versus Three-dimensional Cone-beam Computed Tomography in the Detection of Periapical Lesion After Endodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7736. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen R, Kirkevang LL, Hørsted-Bindslev P, Wenzel A. Randomized clinical trial of root-end resection followed by root-end filling with mineral trioxide aggregate or smoothing of the orthograde gutta-percha root filling--1-year follow-up. Int Endod J. 2009;42(2):105-114. [CrossRef]

- Kwak GH, Kwak EJ, Song JM, et al. Automatic mandibular canal detection using a deep convolutional neural network. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5711. [CrossRef]

- Setzer FC, Shi KJ, Zhang Z, et al. Artificial Intelligence for the Computer-aided Detection of Periapical Lesions in Cone-beam Computed Tomographic Images. Journal of Endodontics. 2020;46(7):987-993. [CrossRef]

- Shah H, Hernandez P, Budin F, et al. Automatic quantification framework to detect cracks in teeth. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2018;10578:105781K. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Wang F, Fan S, Chow JKF. Robotics in Dental Implantology. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 2019;31(3):513-518. [CrossRef]

- Xi S, Hu J, Yue G, Wang S. Accuracy of an autonomous dental implant robotic system in placing tilted implants for edentulous arches. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. Published online September 19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Wang X, Liu Y, et al. Comparing the accuracy and treatment time of a robotic and dynamic navigation system in osteotomy and root-end resection: An in vitro study. International Endodontic Journal. 2025;58(3):529-540. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Depicted in (A) is the 3D-printed maxillary model, and in (C) the corresponding mandibular model. The simulated gingival mask is clearly illustrated. In (B), the model planning for the maxillary molar and second premolar, including the respective roots and the maxillary sinus, is shown. The target structure is marked, representing a simulated periapical radiolucency. (D) illustrates the corresponding planning for the mandible, with the inferior alveolar nerve identified as an adjacent anatomical structure at risk.

Figure 1.

Depicted in (A) is the 3D-printed maxillary model, and in (C) the corresponding mandibular model. The simulated gingival mask is clearly illustrated. In (B), the model planning for the maxillary molar and second premolar, including the respective roots and the maxillary sinus, is shown. The target structure is marked, representing a simulated periapical radiolucency. (D) illustrates the corresponding planning for the mandible, with the inferior alveolar nerve identified as an adjacent anatomical structure at risk.

Figure 2.

The figure illustrates the digital planning workflow. Firstly, acquisition of the cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan and object scan of the model are made. Then surgical planning, digital placement of the reference marker, and design of the customized registration tray are followed. After 3D printing, the tray’s fit is verified on the model before being positioned within the simulation dummy. Prior to initiating navigated surgery, the surgical burr must be registered using a dedicated registration tool. On the navigation screen, the left side displays the real-time position of the burr overlaid on axial and coronal CBCT slices, while the right side of the display shows the target marker, the planned entry point, and the current drilling depth. In the center picture, the drilling procedure using a 2.3 mm surgical round burr is shown. On the right picture, the arc-shaped incision following apicoectomy is depicted.

Figure 2.

The figure illustrates the digital planning workflow. Firstly, acquisition of the cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan and object scan of the model are made. Then surgical planning, digital placement of the reference marker, and design of the customized registration tray are followed. After 3D printing, the tray’s fit is verified on the model before being positioned within the simulation dummy. Prior to initiating navigated surgery, the surgical burr must be registered using a dedicated registration tool. On the navigation screen, the left side displays the real-time position of the burr overlaid on axial and coronal CBCT slices, while the right side of the display shows the target marker, the planned entry point, and the current drilling depth. In the center picture, the drilling procedure using a 2.3 mm surgical round burr is shown. On the right picture, the arc-shaped incision following apicoectomy is depicted.

Figure 3.

Illustrated workflow. In (A), the mandibular with the mounted individual printed tray with the marker is shown and (B) shows the operation with the help of the real-time navigation (C) is visualizing the stereo triangulation of the DENACAM® system (mininavident AG, Basel, Switzerland).

Figure 3.

Illustrated workflow. In (A), the mandibular with the mounted individual printed tray with the marker is shown and (B) shows the operation with the help of the real-time navigation (C) is visualizing the stereo triangulation of the DENACAM® system (mininavident AG, Basel, Switzerland).

Figure 4.

The left boxplot shows the data of osteotomized volume in the navigated and conventional groups. On the right the data of the resected root apex is shown.

Figure 4.

The left boxplot shows the data of osteotomized volume in the navigated and conventional groups. On the right the data of the resected root apex is shown.

Figure 5.

The left box plot shows the time in seconds. The middle plot shows the length of the cut in horizontal diameter, and the right plot shows the vertical height in millimeters.

Figure 5.

The left box plot shows the time in seconds. The middle plot shows the length of the cut in horizontal diameter, and the right plot shows the vertical height in millimeters.

Table 1.

Descreptive statistics for the operation method. Displayed are the number of attempts, means, and standard deviations.

Table 1.

Descreptive statistics for the operation method. Displayed are the number of attempts, means, and standard deviations.

| Table 1 |

Operation method |

N |

Mean value |

Standard deviation |

| Horizontal incision length in mm |

Conventional |

20 |

17.65 |

5.91 |

| Navigated |

20 |

16.25 |

5.48 |

| Resected bone volume in mm3

|

Conventional |

20 |

67.23 |

21.57 |

| Navigated |

20 |

37.32 |

22.97 |

| Length of removed apex in mm |

Conventional |

18 |

3.21 |

1.11 |

| Navigated |

18 |

2.63 |

0.44 |

| Time in seconds |

Conventional |

20 |

329.65 |

201.98 |

| Navigated |

20 |

345.5 |

170.01 |

| Vertical incision length in mm |

Conventional |

20 |

7.1 |

4.38 |

| Navigated |

20 |

7.5 |

4.14 |

Table 2.

Evaluation of the examined data using the appropriate statistical tests and effect strength.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the examined data using the appropriate statistical tests and effect strength.

| Table 2 |

Test |

p |

Effect strength |

| Horizontal incision length |

Student's t |

0.442 |

Cohens d |

0.246 |

| Resected bone volume |

Student's t |

< 0.001 |

Cohens d |

1.342 |

| Length of removed apex |

Mann-Whitney U |

0,054 |

Biserial rank correlation |

0,380 |

| Time in seconds |

Mann-Whitney U |

0.499 |

Biserial rank correlation |

0.128 |

| Vertical incision length |

Mann-Whitney U |

0.433 |

Biserial rank correlation |

0.145 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).