Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

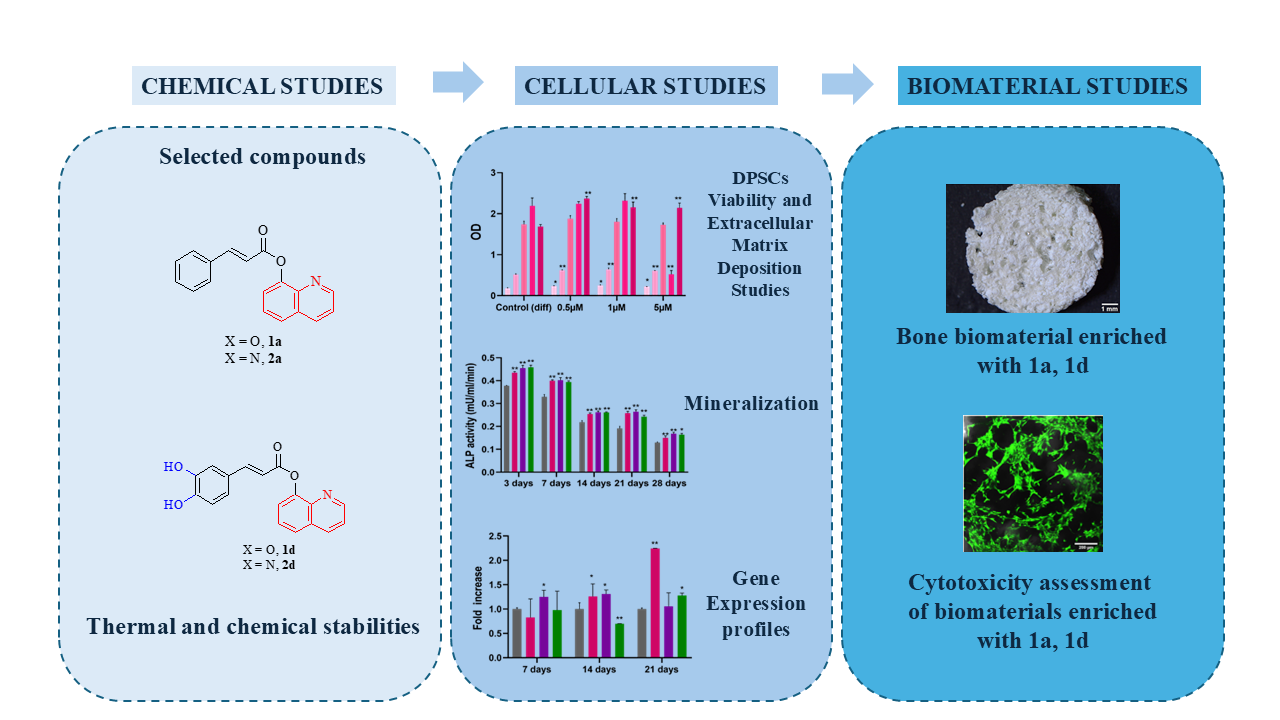

Abstract

Keywords:

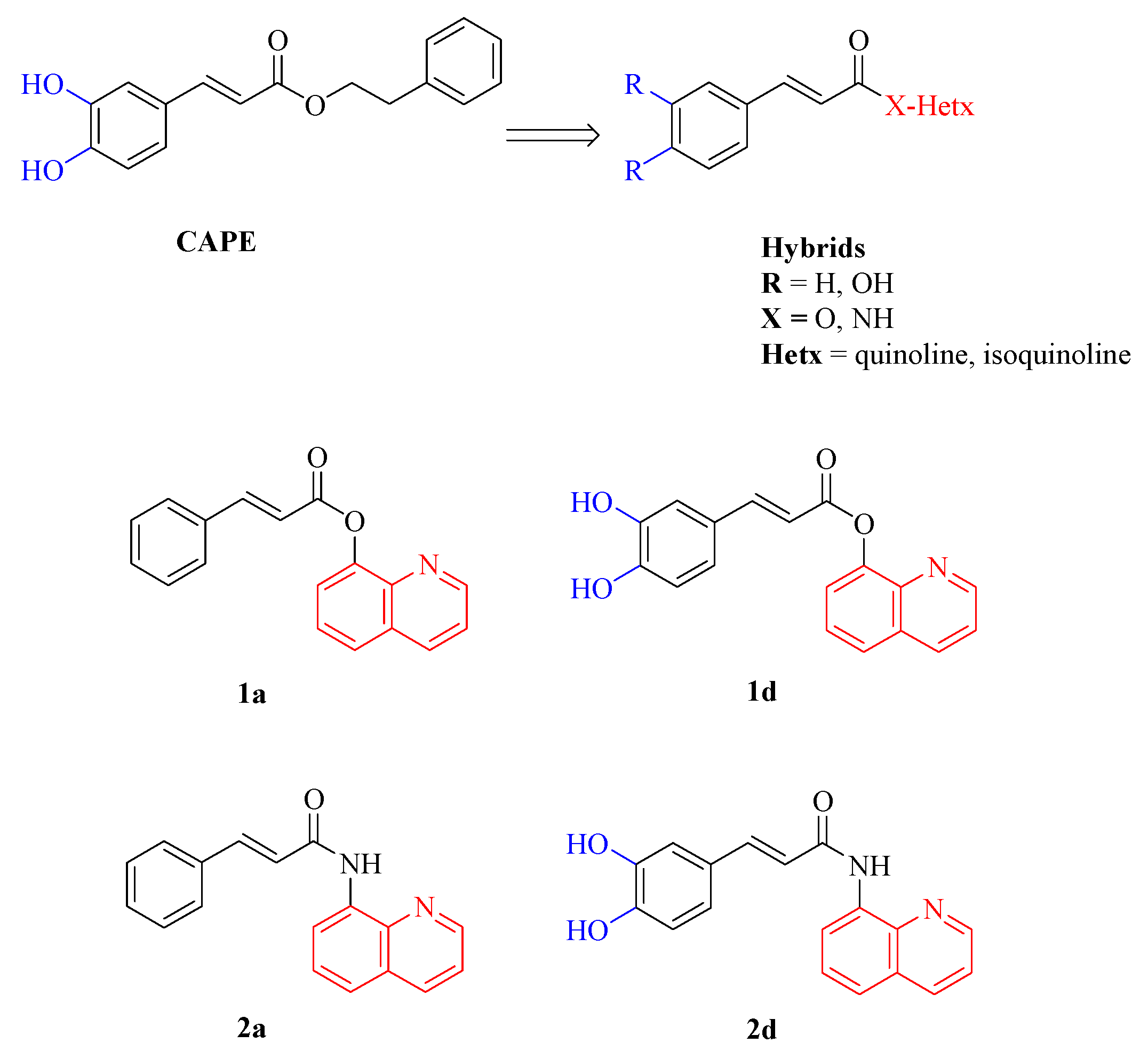

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.1.1. Culture of Dental Pulp Stem Cells

2.1.2. Human Foetal Osteoblast Cell Line

2.2. Crystal Violet Assay

2.3. Osteogenic Differentiation

2.3.1. Alizarin Red S (ARS) Staining

2.3.2. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity

2.3.3. ELISA Analysis of Collagen Type I

2.4. Real-Time RT-PCR

2.4.1. RNA Extraction

2.4.2. Reverse Transcription (RT) and Real-Time RT-Polymerase Chain Reaction (Real-Time RT-PCR)

2.5. Manufacture of Biomaterials Enriched with CAPE Derivatives

2.6. Biomaterial Cytotoxicity Assessment

2.7. Pharmacokinetics

2.7.1. Thermal Stability

2.7.2. Chemical Stability

2.7.3. Kinetic of Chemical Hydrolysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bone Regenerative Ability

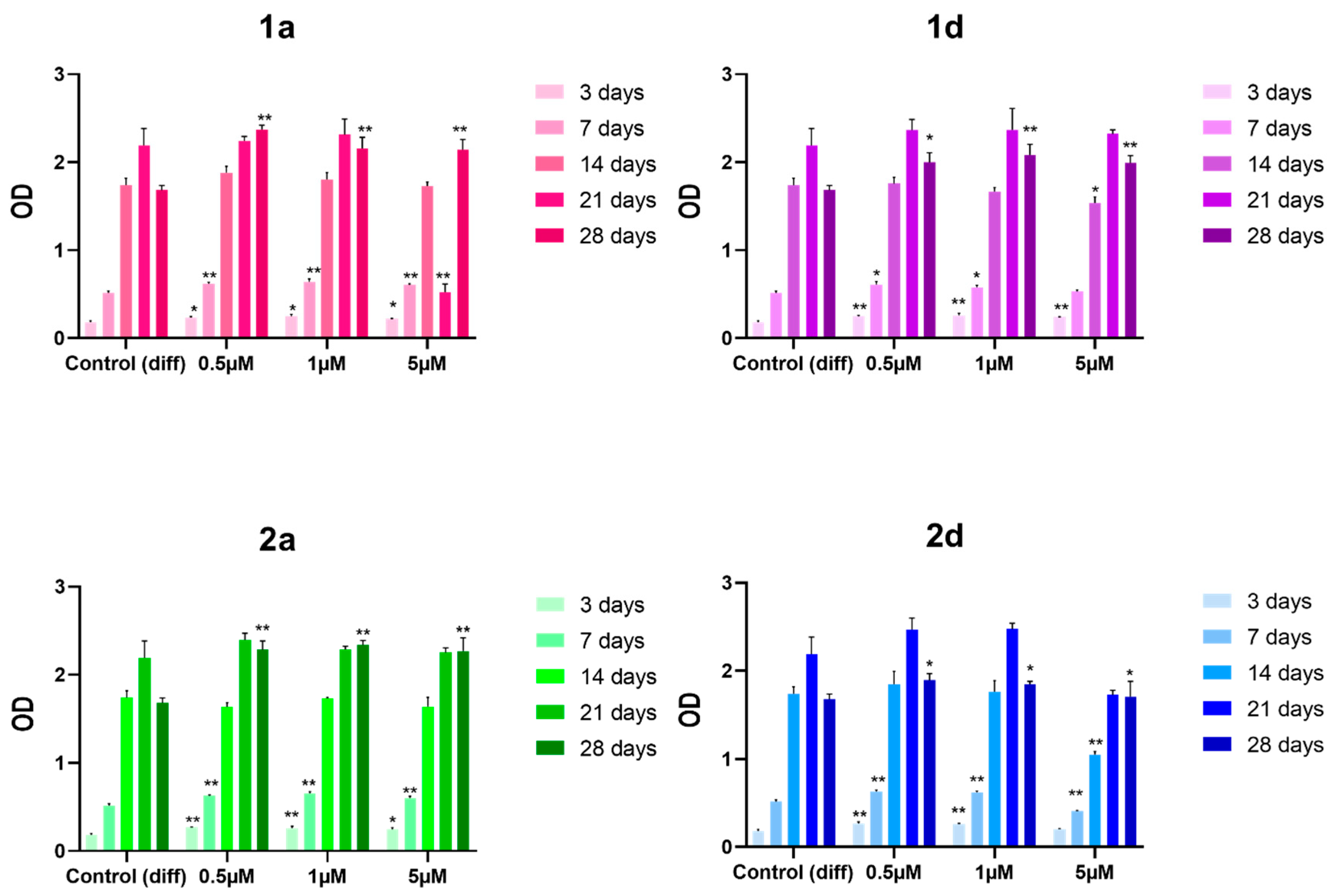

3.1.1. Cell Viability

3.1.2. Extracellular Matrix Deposition Measurement

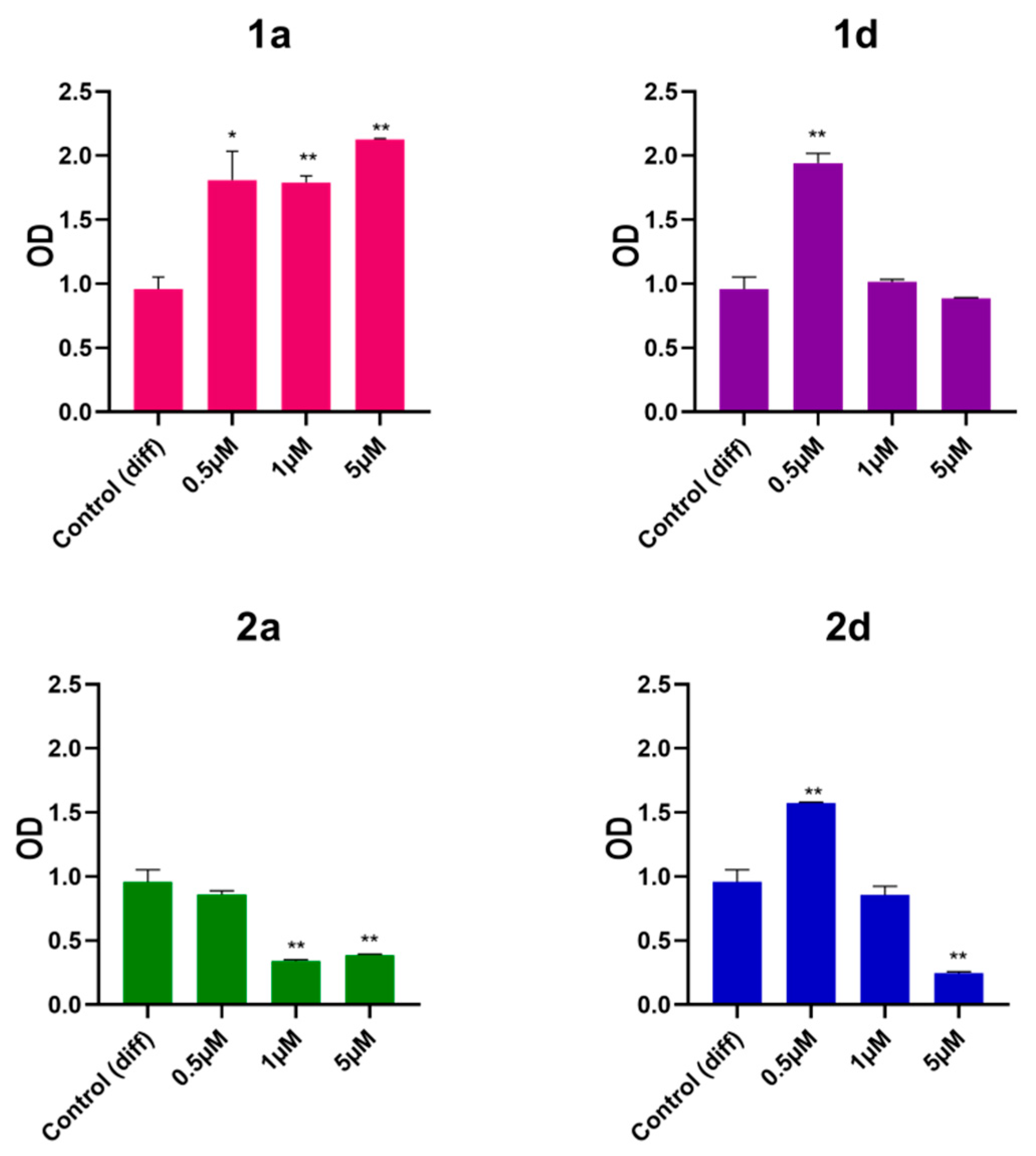

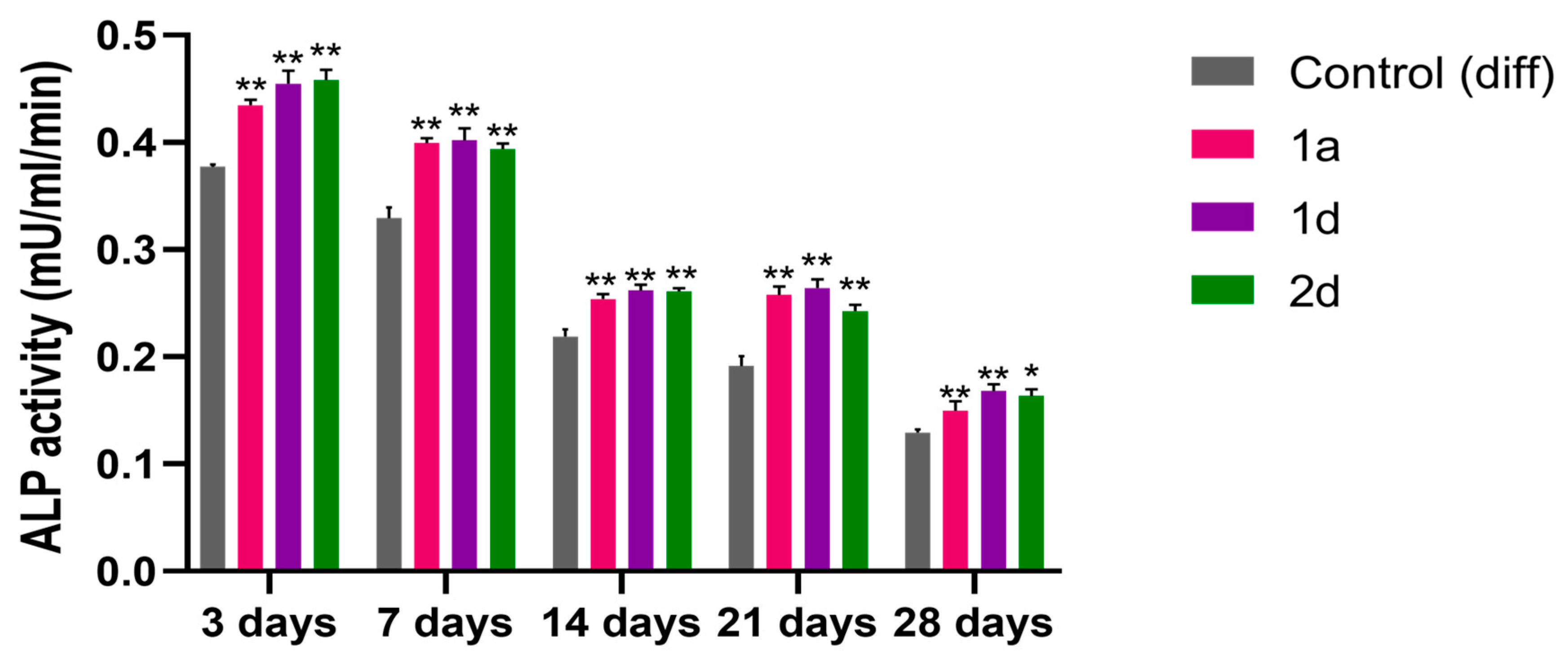

3.1.3. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity

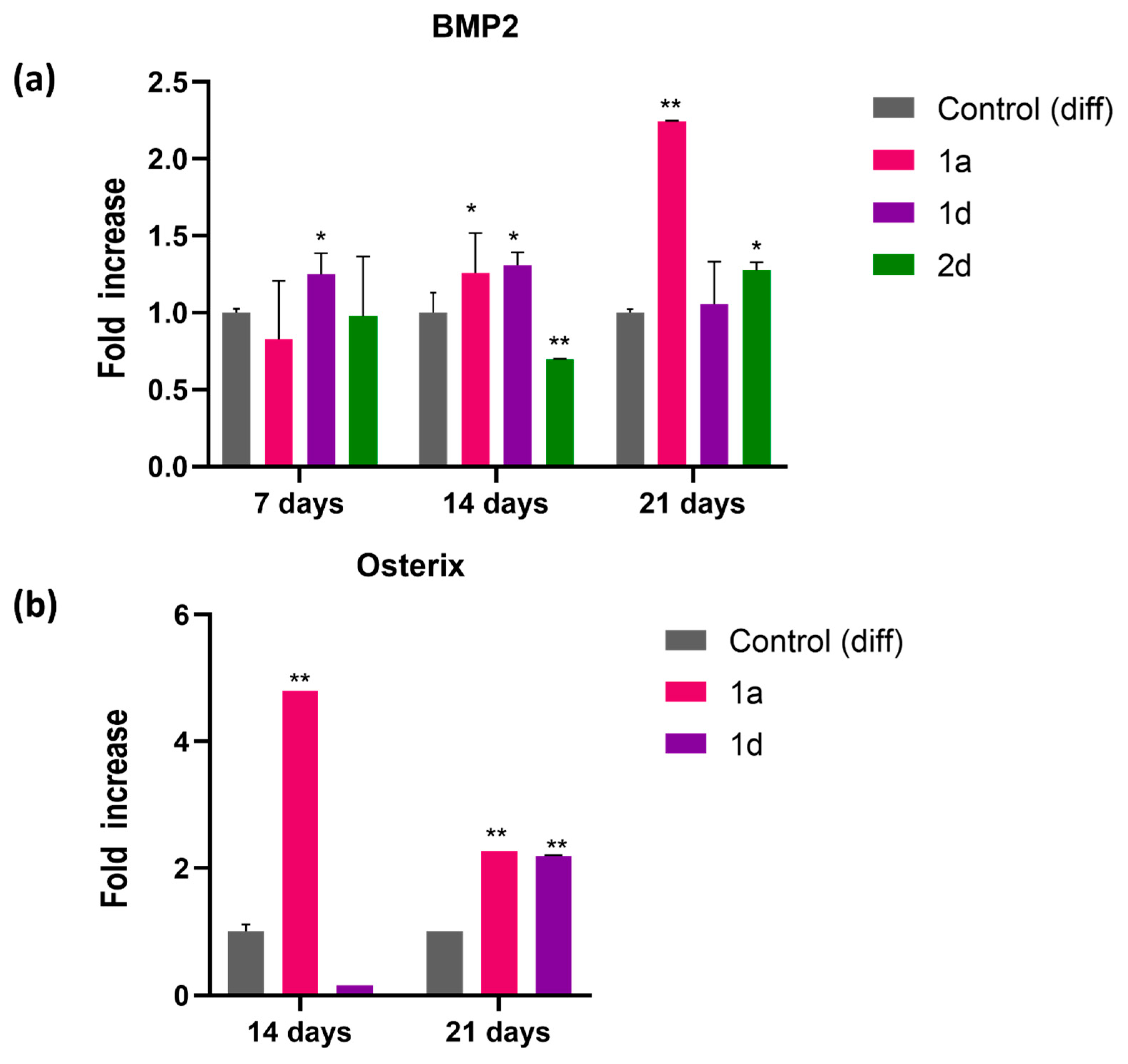

3.1.4. Gene Expression Profile of Mineralization-Related Markers

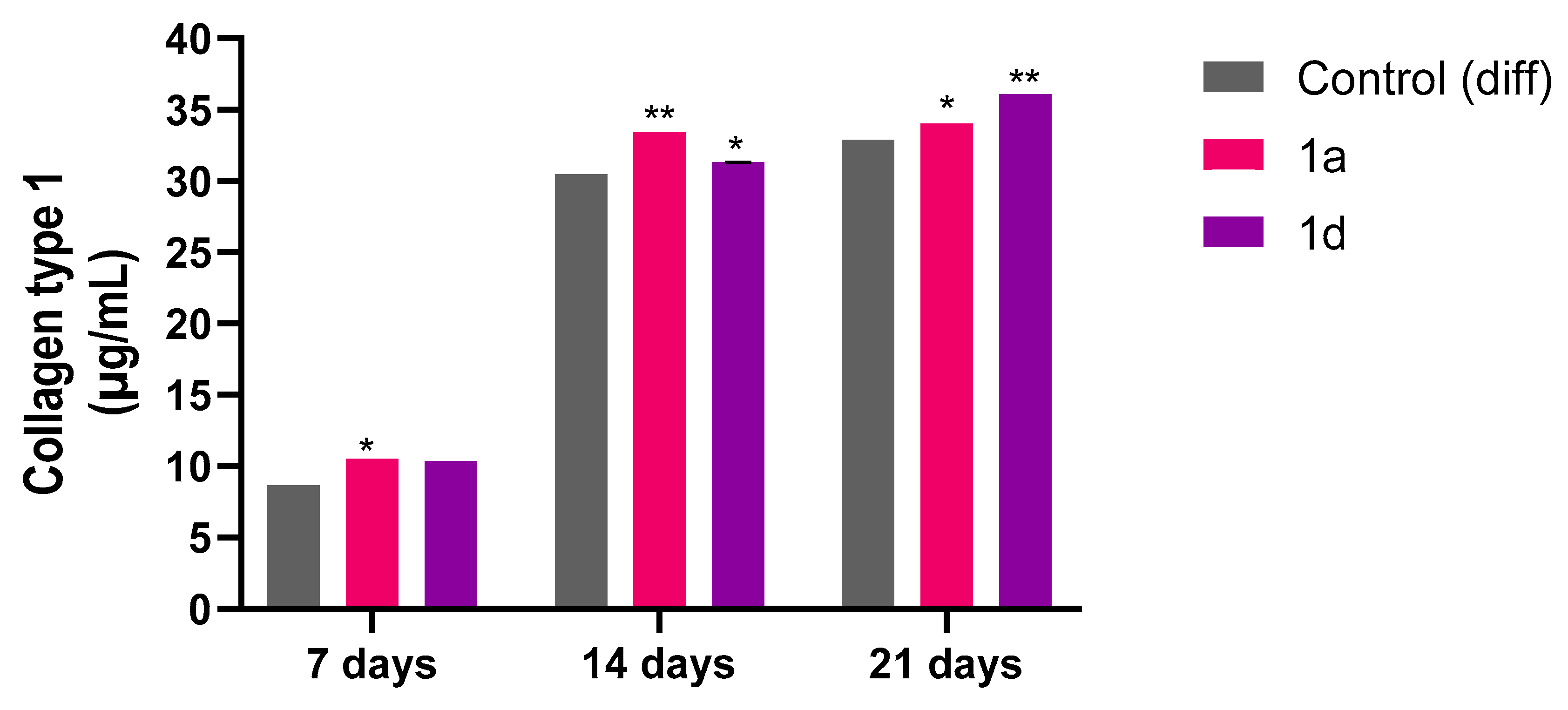

3.1.5. Collagen Type I Release in DPSC Medium

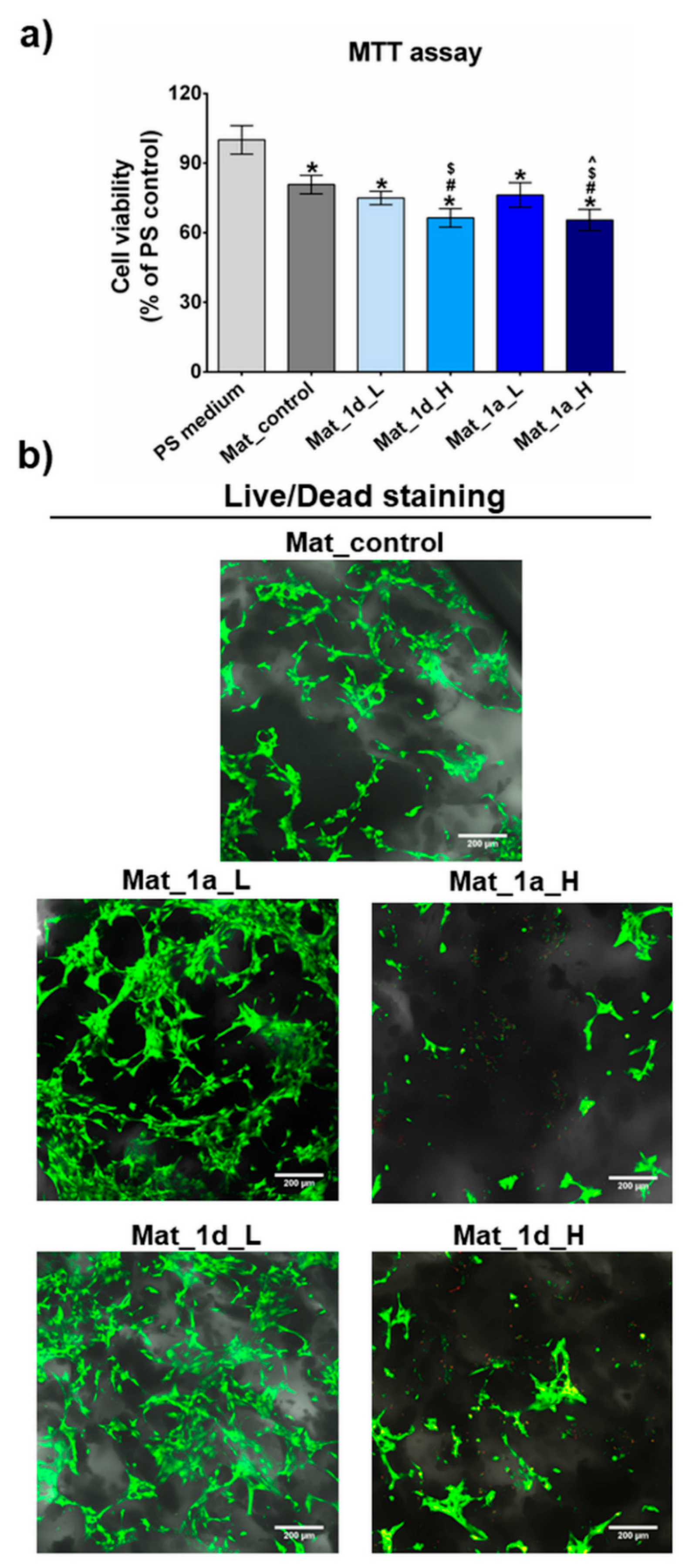

3.2. Bone Biomaterials Enriched with Compound 1a and 1d

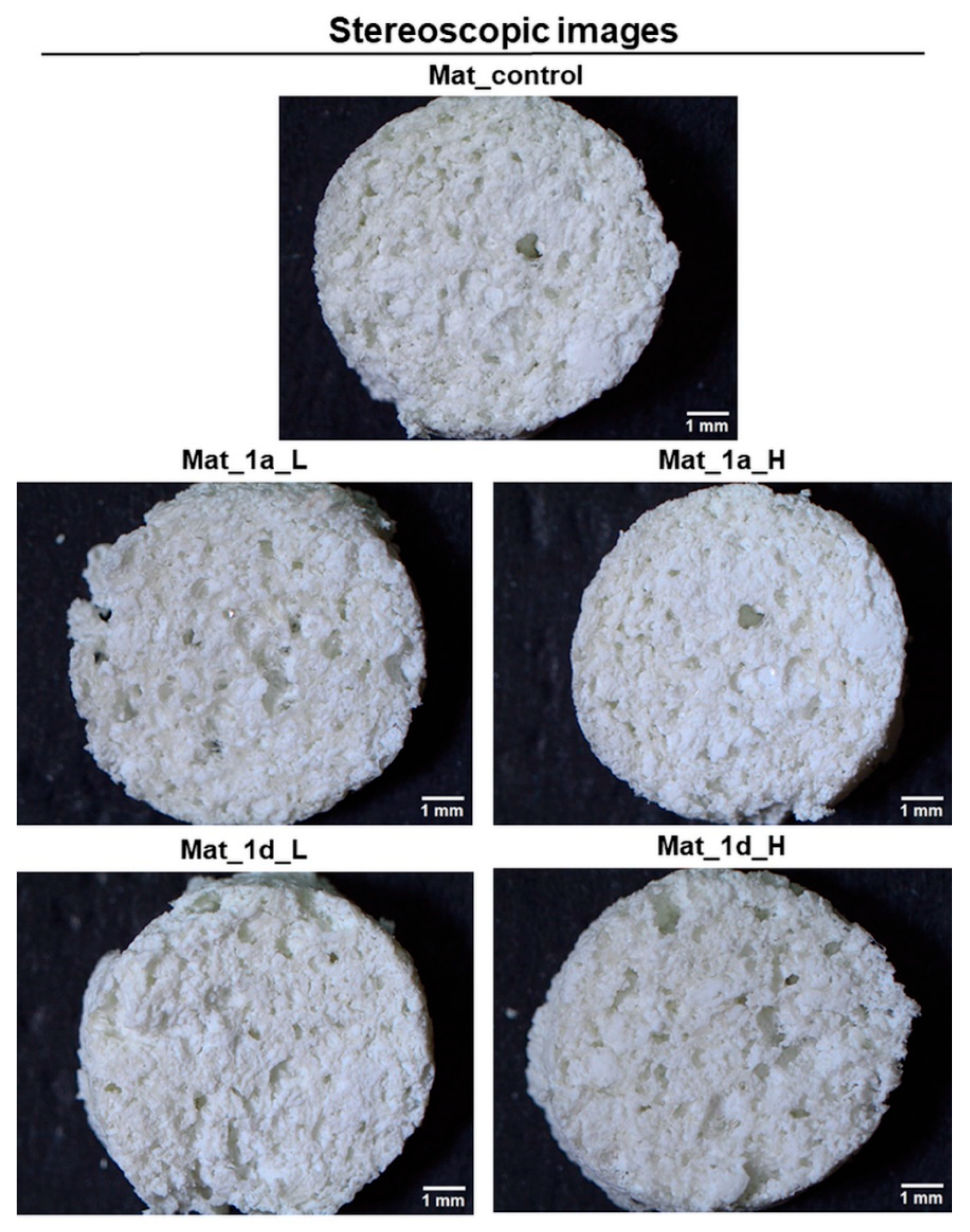

Characterization of Fabricated Bone Biomaterials

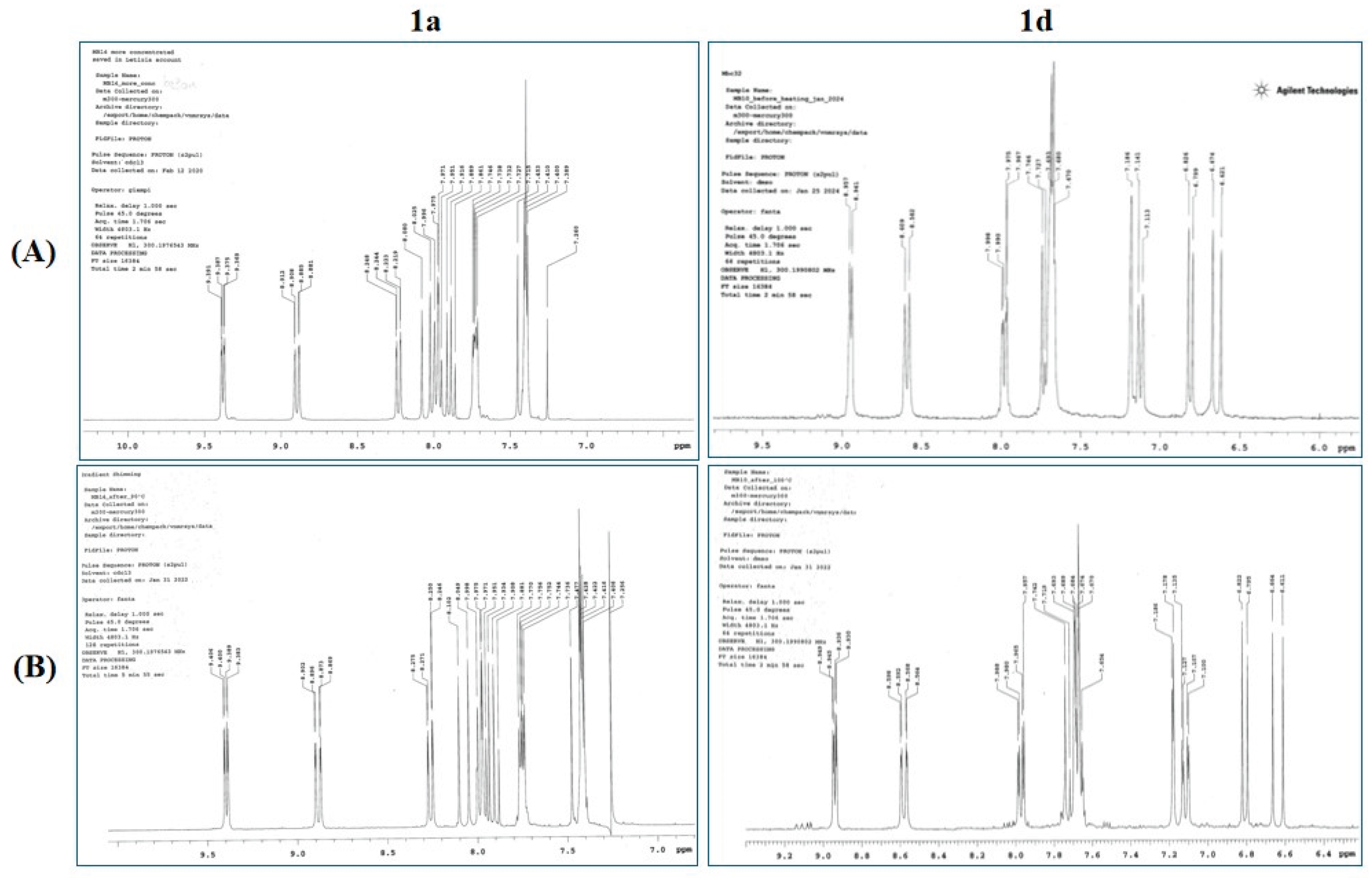

3.3. Chemical and Thermal Stability

3.3.1. Thermal Stability

3.3.2. Chemical Stability

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Chaparro, O.; Linero, I. Regenerative medicine: a new paradigm in bone regeneration. In Advanced Techniques in Bone Regeneration; Zorzi, A.R., Miranda, J.B., Eds.; IntechOpen Limited: London, 2016; pp. 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Codrea, C.I.; Croitoru, A.-M.; Baciu, C.C.; Melinescu, A.; Ficai, D.; Fruth, V.; Ficai, A. Advances in Osteoporotic Bone Tissue Engineering. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oryan, A.; Alidadi, S.; Moshiri, A.; Maffulli, N. Bone regenerative medicine: classic options, novel strategies, and future directions. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2014, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, S.; Roy, S.; Mukherjee, P.; Kundu, B.; De, D.; Basu, D. Orthopaedic applications of bone graft & graft substitutes: a review. Indian Journal of Medical Reseach 2010, 132, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivats, A.R.; Alvarez, P.; Schutte, L.; Hollinger, J.O. Bone regeneration. In Principles of Tissue Engineering; Elsevier: 2014; pp. 1201–1221.

- Elsalanty, M.E.; Genecov, D.G. Bone grafts in craniofacial surgery. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction 2009, 2, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Brydone, A.; Meek, D.; Maclaine, S. Bone grafting, orthopaedic biomaterials, and the clinical need for bone engineering. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine 2010, 224, 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, R.; Jones, E.; McGonagle, D.; Giannoudis, P.V. Bone regeneration: current concepts and future directions. BMC medicine 2011, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-S.; Baez, C.E.; Atala, A. Biomaterials for tissue engineering. World journal of urology 2000, 18, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y. Current status of regenerative medical therapy based on drug delivery technology. Reproductive biomedicine online 2008, 16, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.A.; Sampaio, L.C.; Ferdous, Z.; Gobin, A.S.; Taite, L.J. Decellularized matrices in regenerative medicine. Acta biomaterialia 2018, 74, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, S.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Marques, C.F.; Maia, F.R.; Silva, T.H.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Scaffolding strategies for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Materials 2019, 12, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadtler, K.; Singh, A.; Wolf, M.T.; Wang, X.; Pardoll, D.M.; Elisseeff, J.H. Design, clinical translation and immunological response of biomaterials in regenerative medicine. Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklenec, A.; Stamp, A.; Deweerd, E.; Sherwin, A.; Langer, R. Progress in the tissue engineering and stem cell industry “are we there yet?”. Tissue engineering. Part B, Reviews 2012, 18, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, A.S.; Mooney, D.J. Regenerative medicine: Current therapies and future directions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 112, 14452–14459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzobo, K.; Thomford, N.E.; Senthebane, D.A.; Shipanga, H.; Rowe, A.; Dandara, C.; Pillay, M.; Motaung, K. Advances in Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering: Innovation and Transformation of Medicine. Stem cells international 2018, 2018, 2495848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Atala, A. Small molecules and small molecule drugs in regenerative medicine. Drug Discovery Today 2014, 19, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goonoo, N.; Bhaw-Luximon, A. Mimicking growth factors: Role of small molecule scaffold additives in promoting tissue regeneration and repair. RSC advances 2019, 9, 18124–18146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgley, C.M.; Botero, T.M. Dental stem cells and their sources. Dental clinics of North America 2012, 56, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volponi, A.A.; Pang, Y.; Sharpe, P.T. Stem cell-based biological tooth repair and regeneration. Trends in cell biology 2010, 20, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-M.; Sun, H.-H.; Lu, H.; Yu, Q. Stem cell-delivery therapeutics for periodontal tissue regeneration. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6320–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catón, J.; Bostanci, N.; Remboutsika, E.; De Bari, C.; Mitsiadis, T.A. Future dentistry: cell therapy meets tooth and periodontal repair and regeneration. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2011, 15, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Aquino, R.; De Rosa, A.; Lanza, V.; Tirino, V.; Laino, L.; Graziano, A.; Desiderio, V.; Laino, G.; Papaccio, G. Human mandible bone defect repair by the grafting of dental pulp stem/progenitor cells and collagen sponge biocomplexes. Eur Cell Mater 2009, 18, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.; Kumar, B.M.; Lee, W.-J.; Jeon, R.-H.; Jang, S.-J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Park, B.-W.; Byun, J.-H.; Ahn, C.-S.; Kim, J.-W. Multilineage potential and proteomic profiling of human dental stem cells derived from a single donor. Experimental Cell Research 2014, 320, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadar, K.; Kiraly, M.; Porcsalmy, B.; Molnar, B.; Racz, G.Z.; Blazsek, J.; Kallo, K.; Szabo, E.L.; Gera, I.; Gerber, G.; et al. Differentiation potential of stem cells from human dental origin - promise for tissue engineering. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society 2009, 60 (Suppl. 7), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, M.; Iohara, K.; Wakita, H.; Hattori, H.; Ueda, M.; Matsushita, K.; Nakashima, M. Dental pulp-derived CD31−/CD146− side population stem/progenitor cells enhance recovery of focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Tissue Engineering Part A 2011, 17, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishkitiev, N.; Yaegaki, K.; Imai, T.; Tanaka, T.; Nakahara, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Mitev, V.; Haapasalo, M. High-purity hepatic lineage differentiated from dental pulp stem cells in serum-free medium. Journal of endodontics 2012, 38, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, K.M.; O’Carroll, D.C.; Lewis, M.D.; Rychkov, G.Y.; Koblar, S.A. Neurogenic potential of dental pulp stem cells isolated from murine incisors. Stem cell research & therapy 2014, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Spath, L.; Rotilio, V.; Alessandrini, M.; Gambara, G.; De Angelis, L.; Mancini, M.; Mitsiadis, T.; Vivarelli, E.; Naro, F.; Filippini, A. Explant-derived human dental pulp stem cells enhance differentiation and proliferation potentials. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2010, 14, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- About, I. Dentin–pulp regeneration: the primordial role of the microenvironment and its modification by traumatic injuries and bioactive materials. Endodontic Topics 2013, 28, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, M.; Azab, S.; Khalifa, A.; Abdel-Rahman, S.; Abdel-Naim, A. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, a promising component of propolis with a plethora of biological activities: A review on its anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective effects. IUBMB life 2013, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemli, H.K.; Akyol, S.; Armutcu, F.; Akyol, O. Antiviral properties of caffeic acid phenethyl ester and its potential application. Journal of intercultural ethnopharmacology 2015, 4, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyol, S.; Ozturk, G.; Ginis, Z.; Armutcu, F.; Yigitoglu, M.R.; Akyol, O. In vivo and in vitro antıneoplastic actions of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE): therapeutic perspectives. Nutrition and cancer 2013, 65, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaha, M.; De Filippis, B.; Cataldi, A.; di Giacomo, V. CAPE and Neuroprotection: A Review. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçan, M.; Koparal, M.; Ağaçayak, S.; Gunay, A.; Ozgoz, M.; Atilgan, S.; Yaman, F. Influence of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on bone healing in a rat model. Journal of International Medical Research 2013, 41, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancioglu, H.O.; Aksakalli, S.; Ezirganli, S.; Birlik, M.; Esrefoglu, M.; Acar, A.H. Effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on bone formation in the expanded inter-premaxillary suture. Drug design, development and therapy 2015, 6483-6488.

- Kazancioglu, H.O.; Bereket, M.C.; Ezirganli, S.; Aydin, M.S.; Aksakalli, S. Effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on wound healing in calvarial defects. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2015, 73, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekeuku, S.O.; Pang, K.L.; Chin, K.Y. Effects of Caffeic Acid and Its Derivatives on Bone: A Systematic Review. Drug design, development and therapy 2021, 15, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.C.; Lu, D.; Bai, J.; Zheng, H.; Ke, Z.Y.; Li, X.M.; Luo, S.Q. Oxidative stress inhibits osteoblastic differentiation of bone cells by ERK and NF-kappaB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 314, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, E.S.; Pavlos, N.J.; Chai, L.Y.; Qi, M.; Cheng, T.S.; Steer, J.H.; Joyce, D.A.; Zheng, M.H.; Xu, J. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, an active component of honeybee propolis attenuates osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption via the suppression of RANKL-induced NF-kappaB and NFAT activity. Journal of cellular physiology 2009, 221, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Choi, H.-S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, Z.H.; Kim, H.-H. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing NFκB and downregulating NFATc1 and c-Fos. International Immunopharmacology 2009, 9, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, N.; Dragani, L.K.; Murzilli, S.; Pagliani, T.; Poggi, A. In vitro and in vivo stability of caffeic acid phenethyl ester, a bioactive compound of propolis. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2007, 55, 3398–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bowman, P.D.; Kerwin, S.M.; Stavchansky, S. Stability of caffeic acid phenethyl ester and its fluorinated derivative in rat plasma. Biomedical Chromatography 2007, 21, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaha, M.; Cataldi, A.; Ammazzalorso, A.; Cacciatore, I.; De Filippis, B.; Di Stefano, A.; Maccallini, C.; Rapino, M.; Korona-Glowniak, I.; Przekora, A.; et al. CAPE derivatives: Multifaceted agents for chronic wound healing. Archiv der Pharmazie 2024, e2400165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurtner, G.C.; Chapman, M.A. Regenerative Medicine: Charting a New Course in Wound Healing. Advances in wound care 2016, 5, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S.G.; Kennewell, P.D.; Russell, A.J.; Silpa, L.; Westwood, R.; Wynne, G.M. Medicine. In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry III, Chackalamannil, S., Rotella, D., Ward, S.E., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2017; pp. 379–435. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.G.; Kennewell, P.D.; Russell, A.J.; Seden, P.T.; Westwood, R.; Wynne, G.M. Stemistry: the control of stem cells in situ using chemistry. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 58, 2863–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursu, A.; Schöler, H.R.; Waldmann, H. Small-molecule phenotypic screening with stem cells. Nature Chemical Biology 2017, 13, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przekora, A.; Czechowska, J.; Pijocha, D.; Ślósarczyk, A.; Ginalska, G. Do novel cement-type biomaterials reveal ion reactivity that affects cell viability in vitro? Open Life Sciences 2014, 9, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasegaran, N.; Govindasamy, V.; Abu Kasim, N.H. Differentiation of stem cells derived from carious teeth into dopaminergic-like cells. International endodontic journal 2016, 49, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortada, I.; Mortada, R. Dental pulp stem cells and osteogenesis: an update. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.H.N.; Silva, H.L.; Martinez, E.F.; Joly, J.C.; Demasi, A.P.D.; de Castro Raucci, L.M.S.; Teixeira, L.N. Low concentrations of caffeic acid phenethyl ester stimulate osteogenesis in vitro. Tissue and Cell 2021, 73, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kwak, H.B.; Lee, Z.H.; Seo, S.B.; Woo, K.M.; Ryoo, H.M.; Kim, G.S.; Baek, J.H. N-acetylcysteine stimulates osteoblastic differentiation of mouse calvarial cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2008, 103, 1246–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, K. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (CAPE) Effects on Dental Pulp Stem Cell (DPSC) Proliferation and Viability. EC Dental Science 2022, 21, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto, H.; Nakanishi, T.; Takegawa, D.; Mieda, K.; Hosaka, K. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Induces Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Production and Inhibits CXCL10 Production in Human Dental Pulp Cells. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2022, 44, 5691–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, A.K.; Lin, Y.H.; Chen, J.X.; Kuo, T.Y.; Shie, M.Y. Additive Manufacturing of Caffeic Acid-Inspired Mineral Trioxide Aggregate/Poly-ε-Caprolactone Scaffold for Regulating Vascular Induction and Osteogenic Regeneration of Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee-Russell, S. Histochemical methods for calcium. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 1958, 6, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, A.; Amoroso, R.; di Giacomo, V.; Zara, S.; Maccallini, C.; Gallorini, M. The Inhibition of the Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Enhances the DPSC Mineralization under LPS-Induced Inflammation. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 14560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Li, F.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Chen, S.; Li, G.; Shi, J.; Dong, N.; Xu, K. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Ameliorates Calcification by Inhibiting Activation of the AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway in Human Aortic Valve Interstitial Cells. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Matos, I.A.F.; Fernandes, N.A.R.; Cirelli, G.; de Godoi, M.A.; de Assis, L.R.; Regasini, L.O.; Rossa Junior, C.; Guimarães-Stabili, M.R. Chalcone T4 Inhibits RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis and Stimulates Osteogenesis In Vitro. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, F.Y.; Liu, W.G. Resveratrol Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Through miR-193a/SIRT7 Axis. Calcified tissue international 2022, 110, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchet, R.; Millán, J.L.; Magne, D. Multisystemic functions of alkaline phosphatases. Phosphatase modulators 2013, 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zara, S.; De Colli, M.; di Giacomo, V.; Zizzari, V.L.; Di Nisio, C.; Di Tore, U.; Salini, V.; Gallorini, M.; Tetè, S.; Cataldi, A. Zoledronic acid at subtoxic dose extends osteoblastic stage span of primary human osteoblasts. Clinical Oral Investigations 2015, 19, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalraj, S. Alkaline phosphatase: Structure, expression and its function in bone mineralization. Gene 2020, 754, 144855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siller, A.F.; Whyte, M.P. Alkaline phosphatase: discovery and naming of our favorite enzyme. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2018, 33, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; De Luna-Bertos, E.; Rivas, A.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; Ruiz, C.; García-Martínez, O. Effect of olive oil phenolic compounds on osteoblast differentiation. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2018, 48, e12904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolba, M.F.; Azab, S.S.; Khalifa, A.E.; Abdel-Rahman, S.Z.; Abdel-Naim, A.B. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, a promising component of propolis with a plethora of biological activities: A review on its anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective effects. IUBMB life 2013, 65, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiğit, U.; Kırzıoğlu, F.Y.; Özmen, Ö. Effects of low dose doxycycline and caffeic acid phenethyl ester on sclerostin and bone morphogenic protein-2 expressions in experimental periodontitis. Biotechnic & Histochemistry 2022, 97, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, C.M.; Chakravarthy, V.; Barnes, G.; Kakar, S.; Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Einhorn, T.A. Autogenous regulation of a network of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) mediates the osteogenic differentiation in murine marrow stromal cells. Bone 2007, 40, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai-Aql, Z.; Alagl, A.S.; Graves, D.T.; Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Einhorn, T.A. Molecular mechanisms controlling bone formation during fracture healing and distraction osteogenesis. Journal of dental research 2008, 87, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, H.; Harada, K.; Ikebe, T.; Shinohara, M.; Enomoto, S. Effect of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) on bone consolidation on distraction osteogenesis: a preliminary study in rabbit mandibles. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2006, 34, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-h.; Choi, S.-W.; Park, S.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Chun, H.-S.; Kim, S.H. Quinoline Compound KM11073 Enhances BMP-2-Dependent Osteogenic Differentiation of C2C12 Cells via Activation of p38 Signaling and Exhibits In Vivo Bone Forming Activity. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0120150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeuku, S.O.; Pang, K.-L.; Chin, K.-Y. Effects of caffeic acid and its derivatives on bone: A systematic review. Drug design, development and therapy 2021, 259-275.

- Hong, S.; Cha, K.H.; Park, J.h.; Jung, D.S.; Choi, J.-H.; Yoo, G.; Nho, C.W. Cinnamic acid suppresses bone loss via induction of osteoblast differentiation with alteration of gut microbiota. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2022, 101, 108900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulsamer, A.; Ortuño, M.J.; Ruiz, S.; Susperregui, A.R.; Osses, N.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. BMP-2 induces Osterix expression through up-regulation of Dlx5 and its phosphorylation by p38. The Journal of biological chemistry 2008, 283, 3816–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.M.; Zhou, X. Genetic and molecular control of osterix in skeletal formation. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2013, 114, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancilio, S.; Gallorini, M.; Di Nisio, C.; Marsich, E.; Di Pietro, R.; Schweikl, H.; Cataldi, A. Alginate/Hydroxyapatite-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering Improve Dental Pulp Biomineralization and Differentiation. Stem Cells International 2018, 2018, 9643721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, S.; Erdil, A.; Gevrek, F. Effects of systemic Anatolian propolis administration on a rat-irradiated osteoradionecrosis model. Journal of Applied Oral Science 2023, 31, e20230231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrullah, M.Z. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Loaded PEG–PLGA Nanoparticles Enhance Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, P.; Benko, A.; Palka, K.; Canal, C.; Kolodynska, D.; Przekora, A. Novel synthesis method combining a foaming agent with freeze-drying to obtain hybrid highly macroporous bone scaffolds. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2020, 43, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przekora, A. The summary of the most important cell-biomaterial interactions that need to be considered during in vitro biocompatibility testing of bone scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 97, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malafaya, P.B.; Reis, R.L. Bilayered chitosan-based scaffolds for osteochondral tissue engineering: influence of hydroxyapatite on in vitro cytotoxicity and dynamic bioactivity studies in a specific double-chamber bioreactor. Acta Biomaterialia 2009, 5, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Bao, B.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Y. Bioactive Conjugated Polymer-Based Biodegradable 3D Bionic Scaffolds for Facilitating Bone Defect Repair. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2024, 13, 2302818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kerwin, S.M.; Bowman, P.D.; Stavchansky, S. Stability of caffeic acid phenethyl amide (CAPA) in rat plasma. Biomedical Chromatography 2012, 26, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P. Bone remodelling. British journal of orthodontics 1998, 25, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takegahara, N.; Kim, H.; Choi, Y. Unraveling the intricacies of osteoclast differentiation and maturation: insight into novel therapeutic strategies for bone-destructive diseases. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024, 56, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| 18S_FOR | CATGGCCGTTCTTAGTTGGT |

| 18S_REV | CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGTAG |

| BMP2_FOR | CACTTGGCTGGGGACTTCTT |

| BMP2_REV | CGCGCAGTCTCTCTTTTCAC |

| SP7_FOR | CTCAGGCCACCCGTTG |

| SP7_REV | CATAGTGAACTTCCTCCTCAAGC |

| Time (min) | A (%) | B (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 90 | 10 |

| 6 | 10 | 90 |

| 10 | 10 | 90 |

| 12 | 90 | 10 |

| 15 | 90 | 10 |

| CAPE | 1a | 1d | ||||

| t1/2 (h)a | Kobs (h-1)a | t1/2 (h)a | Kobs (h-1)a | t1/2 (h)a | Kobs (h-1)a | |

| pH 4.5 | 117.5 (±2.10) | 0.006 (±0.0009) | 80.6 (±2.3) | 0.009 (±0.0008) | stable | - |

| pH 7.4 | 38.5 (±0.41) | 0.018 (±0.004) | stable | - | 21.19 (±0.37) | 0.033 (±0.002) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).