1. Introduction

Reward processing is a key neurocognitive function essential for survival in most species. Understanding the mechanisms of reward processing is crucial as they are fundamental to human cognition and behavior, including motivation, learning, and decision-making [

1]. Further, dysfunction in reward processing is linked to several psychiatric disorders such as addiction, depression, and obesity [

2,

3,

4], making it critical to elucidate neural substrates and behavioral correlates of reward processing. While primary rewards (e.g., food, sex) and secondary rewards (e.g., money, tokens, and verbal reinforcements, such as appreciation) [

5] are important, in humans the utmost importance is placed on monetary rewards, as they can buy most of the other rewards [

6]. Most human studies investigating reward processing have often used monetary incentives as a proxy for primary rewards [

7]. Further, neuroimaging studies have indicated that primary rewards may evoke similar neural responses in humans in response to more abstract, or secondary rewards such as monetary incentives [

8,

9]. Studies have also shown that gambling tasks are better suited to examine the neural substrates of monetary reward processing in humans than other paradigms [

10].

Over the decades, studies on animals and humans have employed various neuroimaging methods to elucidate neural substrates of reward processing. In particular, many studies have used functional MRI (fMRI) to elucidate brain structures that are related to aspects of reward processing [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These studies have identified a set of subcortical (i.e., ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, putamen, caudate, pallidum, amygdala, thalamus, and hippocampus) and cortical regions (i.e., insula, parahippocampal gyrus, cingulum, orbitofrontal cortex, angular gyrus, superior parietal lobule, inferior parietal lobule, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) that are activated during reward processing [

18]. Studies have also found that individual variability in behavioral characteristics can affect reward processing and its neural substrates [

6,

10,

19,

20]. More specifically, psychological characteristics (e.g., impulsivity) [

20,

21], task performance (e.g., opting for risky vs. safer choices in tasks assessing reward processing) [

20,

22], and neuropsychological variables (e.g., executive functions, memory, etc.) [

20,

22] can modulate monetary reward processing. However, only a few studies have examined associations of psychological, behavioral, and neuropsychological characteristics with neural substrates of reward processing.

Impulsivity, a key factor known to modulate the reward processing mechanism [

23,

24], has three core aspects: 1) acting on the spur of the moment (motor impulsivity), 2) not focusing on the task at hand (attentional or cognitive impulsivity), and 3) lack of planning without adequate thinking (non-planning impulsivity) [

25,

26]. A previous fMRI study reported that individual differences in impulsivity accounted for variations in the reward-related blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) response in the ventral striatum and the orbitofrontal cortex [

27]. Further, decreased activation of the ventral striatum and anterior cingulate during reward processing was shown to correlate with high impulsivity in those with alcohol use disorder [

23]. These findings emphasize the need to confirm the association between impulsivity and BOLD activation of specific brain structures during reward processing, particularly while evaluating monetary outcomes.

fMRI studies have identified specific brain regions associated with task-related behaviors. For example, putamen activity was shown to be associated with the stimulus-action-reward association [

28] and with reward sensitivity [

29], while the midbrain activation was linked to efficiency in task performance [

30]. However, the association between brain activation and participants’ performance style or strategies during monetary reward processing, such as choosing risky bets against safer options after previous losses, has not been adequately studied. Therefore, one of the aims of the current fMRI study is to examine this association during a monetary gambling task.

Lastly, studies have reported associations between cognitive abilities measured with neuropsychological tests and neural activation in specific brain structures during reward processing. For example, the basal ganglia structures, particularly the putamen, were found to modulate working memory in a delayed-response task of a reward paradigm [

31], while putamen activity was associated with cognitive functions in general [

32] and learning and memory in particular [

33,

34]. Further, executive functions such as planning and problem-solving may also be inherently associated with reward processing and related neural activation [

35]. Although brain-behavior associations in the context of reward processing have been examined by some studies in an isolated fashion, no study has investigated multiple behavioral and neuropsychological domains on the same participants.

Therefore, the current study aims to understand associations among brain regions involved in reward processing networks and elucidate neural substrates underlying the evaluation of win versus loss outcomes using a monetary gambling task in a group of healthy participants. Furthermore, the current study will investigate possible associations of activations of brain reward structures with key aspects of behavior and cognitive function (impulsivity, task performance, and neuropsychological measures).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The sample consisted of 30 healthy, young male participants (ages 19-38, mean = 27.4 years) who were recruited from the community. The exclusion criteria were (i) diagnosis of major psychiatric disorder or substance use disorders, (ii) hearing/visual impairment, (iii) history of head injury, and (iv) cognitive deficits or a score of <24 on the mini-mental state examination (MMSE). Most of the participants (28 out of 30) in the study were right-handed, and their education ranged from 12 to 20 years with a mean of 15.8 years. Behavioral and neuropsychological data were collected at the SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University. The structural and functional MRI data were acquired at the Nathan Kline Institute (NKI) for Psychiatric Research. Informed consent was obtained from the participants, and the research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both centers (IRB approval ID: SUNY–266893; NKI–212263).

2.2. The Monetary Gambling Task (MGT)

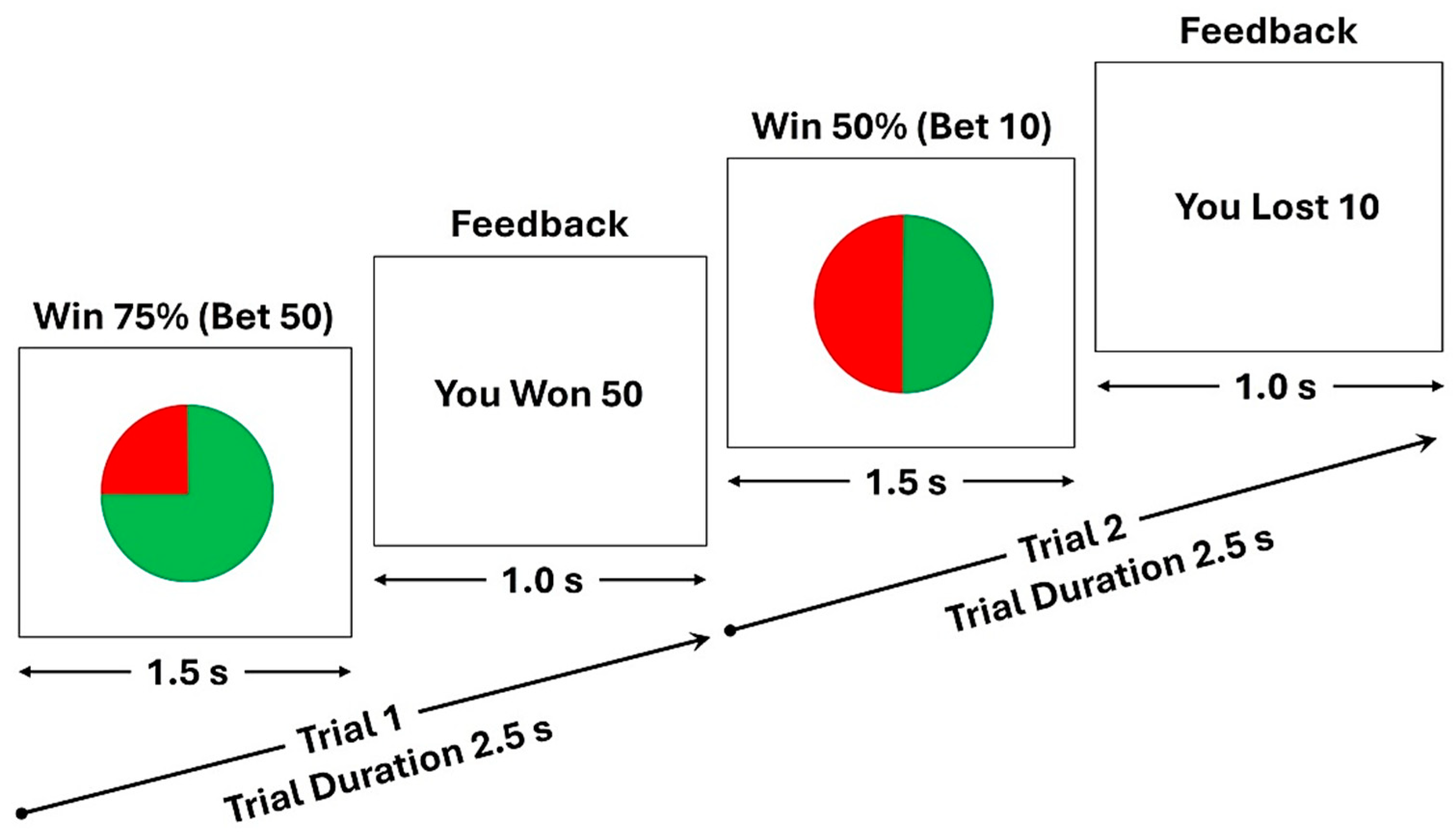

The Monetary Gambling Task (MGT), as illustrated in

Figure 1, consisted of 240 trials. The duration of each trial was 2.5 seconds, and it took about 10 minutes to complete the task. Each trial consisted of two stimulus presentations: (a) a pie stimulus presenting the chance of winning (75%, 50%, or 25%) for the duration of 1.5 s, during which the participant was instructed to select a bet amount of either 10 tokens, by pressing button 1, or 50 tokens, by pressing button 2, on a button response unit with their right hand; and (b) a feedback stimulus for the duration of 1.0 s with a text indicating whether the participant won or lost the bet amount. Thus, six types of trials were presented randomly, irrespective of the bet amount (see

Table 1): (1) chance of winning = 50%; outcome = win; number of trials = 40; (2) chance of winning = 50%; outcome = loss; number of trials = 40; (3) chance of winning = 75%; outcome = win; number of trials = 60; (4) chance of winning = 75%; outcome = loss; number of trials = 20; (5) chance of winning = 25%; outcome = win; number of trials = 20; and (6) chance of winning = 25%; outcome = loss; number of trials = 60. The participants were not made aware of the trial types and sequence. If the participant failed to make a bet within 1.5 s after the presentation of the pie stimulus, a feedback stimulus “No bet made!” would appear on the screen. The total amount won or lost by the participant was displayed at the end of the task.

2.3. Behavioral Scores Extracted from Task Performance

The list of behavioral scores that were computed for the participants based on their performance of the monetary gambling task is shown in

Table 2. These scores included: (i) total number of tokens won or lost at the end of the task; (ii) number of trials with bet amount 50 when the outcome/feedback was "Loss" for the previous one, two, and three trials, respectively, suggesting potential risky behavior; (iii) number of trials with bet amount 10 when the outcome/feedback was "Loss" for the previous one, two, and three trials, respectively, suggesting potential safe behavior; (iv) number of trials with bet amount 50 when the net outcome was "Loss" for the previous two and three trials, respectively, indicating risky behavior; and (v) number of trials with bet amount 10 when the net outcome was "Loss" for the previous two and three trials, respectively, indicating safe behavior. The term "net outcome" for two or more consecutive trials refers to the resulting number of tokens lost or won during those trials. For instance, if the outcomes during the previous two trials were a win of 10 and a loss of 50, the net outcome for those two trials would be a loss of 40 tokens.

2.4. Neuroimaging Protocol

2.4.1. Structural and Functional MRI Data Collection

Both structural and functional MRI data were collected using a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Trio scanner (Erlangen, Germany). BOLD fMRI scans were acquired using a T2*-weighted gradient echo single-shot echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with these acquisition parameters: number of slices=36; voxel size=(2.5×2.5×3.5) mm3; FOV=240 mm; TR=2500 ms; TE=30 ms; flip angle=80°; parallelization factor=2; acquisition time=2.5 s per volume; and number of volumes=240. The sequence was carefully optimized to minimize the effects of magnetic susceptibility inhomogeneities (such as distortions and signal dropouts), as well as the effects of mechanical vibrations, which elevate Nyquist ghosting levels. In addition, a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) high-resolution three-dimensional T1-weighted structural sequence was collected to be used as an anatomical reference for the fMRI data as well as for the non-linear registration of imaging data between subjects. The sequence parameters for the MPRAGE were: TR = 2500 ms; TE = 3.5 ms; TI = 1200 ms; flip angle = 8°; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3; matrix size = 256 × 256 × 192; FOV = 256 mm; and number of averages = 1.

2.4.2. Image Processing of the fMRI Data

Processing of the imaging data included the following stages. Within each subject, the MPRAGE and fMRI volumes were registered using the intra-subject inter-modality linear registration module [

36] of the Automatic Registration Toolbox (ART;

www.nitrc.org/projects/art). The

brainwash program within the ART toolbox was used for skull-stripping the MPRAGE volumes. To correct for small subject motion during fMRI acquisitions, motion detection and correction was performed using the

3dvolreg module of the AFNI software package [

37]. To correct for the geometric distortions of the fMRI images due to magnetic susceptibility differences in the head, particularly at brain/air interfaces, we used the non-linear registration module of the ART [

38]. The skull-stripped MPRAGE images from all subjects were non-linearly registered to a study-specific population template using ART's non-linear registration algorithm

3dwarper, which is one of the most accurate inter-subject registration methods available [

39]. The population template was formed using an iterative method [

40]. The motion-corrected fMRI time series were detrended using PCA [

41]. Finally, fMRI data from all subjects were normalized to a standard space using the image registration steps outlined above, which were mathematically combined into a single transformation and used in re-sampling the fMRI data.

2.4.3. Extraction of BOLD Activation Clusters for the Win-Loss Contrast

We used a Sparse Principal Component Analysis (sPCA) method [

42] to identify activation clusters from the data matrix containing 7050 voxels that were detected to be activated during the task conditions. The sPCA is a novel and efficient method to identify activation clusters. While the components from the sPCA have a natural ordering according to their variance similar to the regular PCA, the sPCA performed better in separating the noise from the signal and was found to be more flexible, less committed, and easier to interpret [

42,

43]. The sPCA extracts a relatively minimal number of non-zero components by using the LASSO regression technique, which by driving some loadings to exactly zero and adjusting the other components to approximate the properties of the PCA [

42]. We used the top clusters with a size of 100 voxels or more for statistical analyses (see

Table 3). The activation value for each cluster was determined by taking the mean from all of its voxels. The anatomical labels for the clusters, based on the MNI coordinates of their centroids, were extracted using the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) method [

44], as provided by the R-package

label4MRI (

https://github.com/yunshiuan/label4MRI) (see

Table 3 and

Figure 2).

2.5. Assessment of Impulsivity

The participants were administered the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale—Version 11 (BIS-11) [

26], a 30-item self-administered tool that assessed motor impulsivity (BIS_MI), non-planning (BIS_NP), attentional impulsivity (BIS_AI), and total score (BIS_Tot). BIS-11 has been widely used to assess impulsivity and its biological, psychological, and behavioral correlates [

45]. Attentional impulsivity refers to an inability to focus attention or concentrate on the job at hand, motor impulsivity is the tendency to act on the spur of the moment without thinking, while non-planning impulsivity is conceptualized as a lack of forethought or planning for executing a task [

46].

2.6. Neuropsychological Assessment

Computerized adaptations of the Tower of London Test (TOL) [

47] and the Visual Span Test (VST) [

48,

49] were administered using the Colorado assessment tests for cognitive and neuropsychological assessment [

50], as described previously [

51]. Details of these tests are summarized below.

2.6.1. Tower of London Test (TOL)

The planning and problem-solving ability of the executive functions were assessed using the TOL in which participants solved a set of puzzles with graded difficulty levels by arranging the color beads one at a time from a starting position to a desired goal position in as few moves as possible. The test consisted of 3 puzzle types with 3, 4, and 5 colored beads placed on the same number of pegs, with 7 problems/trials per type and a total of 21 trials. Five performance measures from the summation of all puzzle types were used in the analysis: (i) excess moves (additional moves beyond the minimum moves required to solve the puzzle); (ii) average pickup time (initial thinking/planning time spent until picking up the first bead to solve the puzzle); (iii) average total time (total thinking/planning time to solve the problem in each puzzle type); (iv) total trial time (total performance/execution time spent on all trials within each puzzle type); and (v) average trial time (mean performance/execution time across trials per puzzle type).

2.6.2. Visual Span Test (VST)

The VST was used to assess visuospatial memory span from the forward condition and working memory from the backward condition. In this test, 8 randomly arranged squares were displayed on the screen, and 2–8 squares flashed in a predetermined sequence depending on the span level being assessed. Each span level was administered twice, with a total of 14 trials in each condition. During the forward condition, subjects were required to repeat the sequence in the same order via mouse clicks on the squares. In the backward condition, subjects were required to repeat the sequence in reverse order (starting from the last square). Four performance measures were collected during forward and backward conditions (with a total of 8 scores): (i) total correct scores (total number of correctly performed trials); (ii) span (maximum sequence length achieved); (iii) total average time (sum of the mean time taken across all trials performed); and (iv) total correct average time (sum of the mean time taken across all trials correctly performed).

2.7. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the R packages [

52]. Pearson bivariate correlations were performed to identify significant relationships across the fMRI activation clusters. We also performed an explorative correlational analysis to test the associations between the fMRI activation clusters and the behavioral/cognitive variables. To avoid the Type 2 error [

53,

54] due to the small sample size, multiple testing corrections were not performed for the explorative correlational analysis, and the strength of association was determined based on the magnitude of the correlation coefficient as a metric of effect size [

55].

3. Results

3.1. The fMRI Activation Clusters for the Win-Loss Contrast

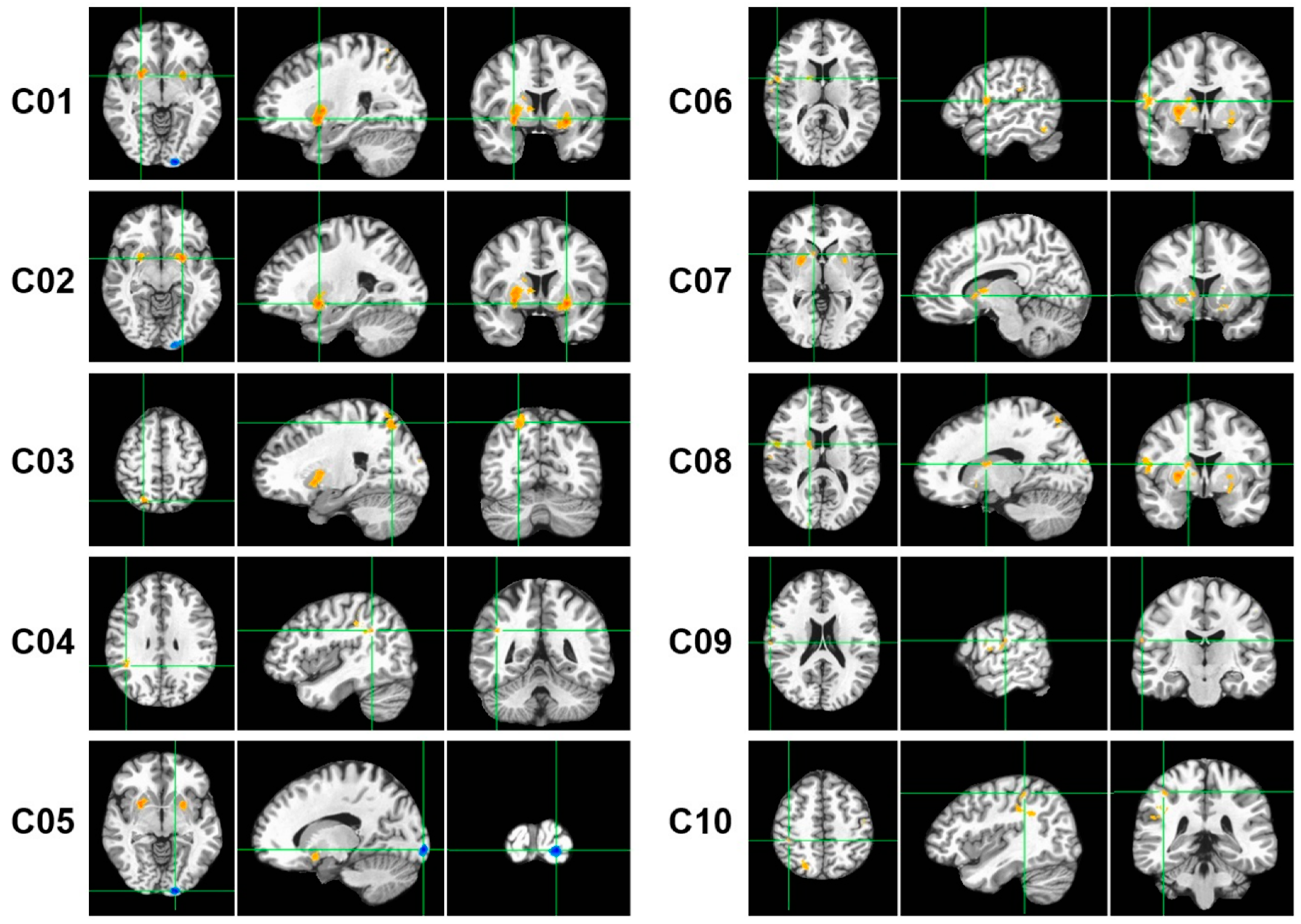

As shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2, the BOLD activation difference between the gambling outcomes (Win-Loss) elicited 10 regions (i.e., clusters) with 100 or more voxels showing activations: (i) Right Putamen, (ii) Left Putamen, (iii) Right Superior Parietal Lobule, (iv) Right Angular Gyrus, (v) Left Inferior Occipital Cortex, (vi) Right Rolandic Operculum, (vii) Right Caudate (anterior-inferior), (viii) Right Caudate (posterior-superior), (ix) Right Supramarginal Gyrus, and (x) Right Inferior Parietal Lobule. Eight of the ten clusters were on the right side, with only two clusters on the left, namely, the left putamen and left inferior occipital cortex. Nine of the ten clusters showed higher activation during win relative to loss (orange/red blobs in

Figure 2), with only the left inferior occipital cortex (cluster # 5) showing higher activation during loss (cyan/blue blobs in

Figure 2). Overall, eight clusters represented the right hemisphere, and two clusters were of the left hemisphere. Putamen showed bilateral activations represented by clusters 1 & 2. The right Caudate was represented by two separate clusters in different locations (i.e., cluster 7 was at the anterior-inferior location, and cluster 8 was at the posterior-superior location. Interestingly, three of the cortical clusters (i.e., clusters 4, 9, and 10) represented inferior parietal lobule, and two of them (clusters 9 & 10) represented the same Brodmann area (BA 40) although cluster 10 (R. IPL) was more medial, posterior, and superior to the anatomical location of cluster 9 (R. SMG).

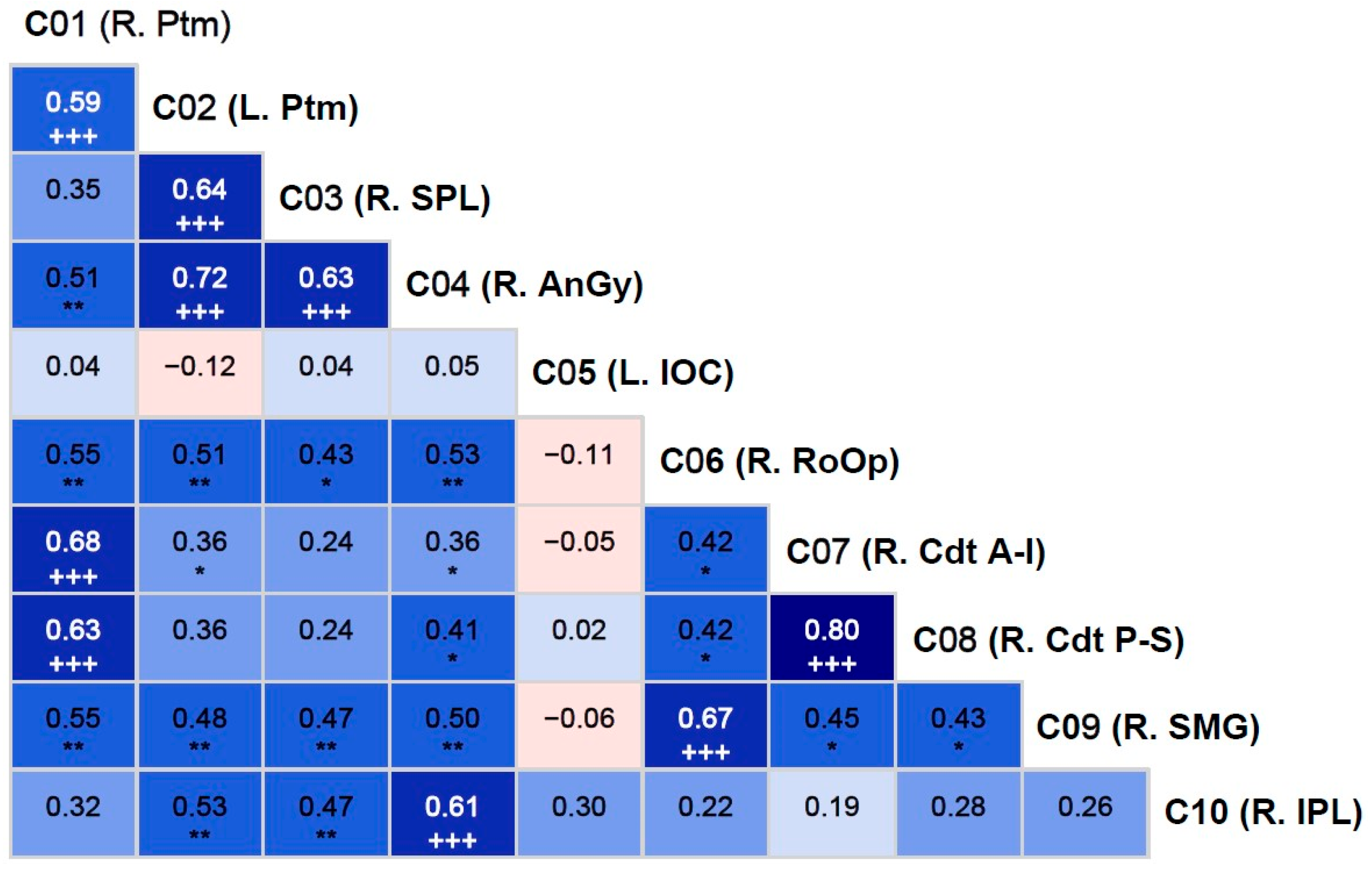

Correlations among the fMRI activation clusters are shown in

Figure 3. All clusters except cluster 5 (L. IOC) showed significant positive correlations with other clusters, even after correcting for multiple testing. Bonferroni-adjusted significant correlations were between (i) cluster 1 (R. Ptm) and cluster 2 (L. Ptm); (ii) cluster 1 (R. Ptm) and cluster 7 (R. Cdt A-I); (iii) cluster 1 (R. Ptm) and cluster 8 (R. Cdt P-S); (iv) cluster 2 (L. Ptm) and cluster 3 (R. SPL); (v) cluster 2 (L. Ptm) and cluster 4 (R. AnGy); (vi) cluster 3 (R. SPL) and cluster 4 (R. AnGy); (vii) cluster 4 (R. AnGy) and cluster 10 (R. IPL); (viii) cluster 6 (R. RoOp) and cluster 9 (R. SMG); and (ix) cluster 7 (R. Cdt A-I) and cluster 8 (R. Cdt P-S). Overall, clusters 1, 2, and 4 had three significant correlations each, followed by clusters 3, 7, and 8 had two correlations each, and clusters 6 and 9 had a single correlation with each other.

3.2. Correlations Between the fMRI Activation Clusters and Other Variables

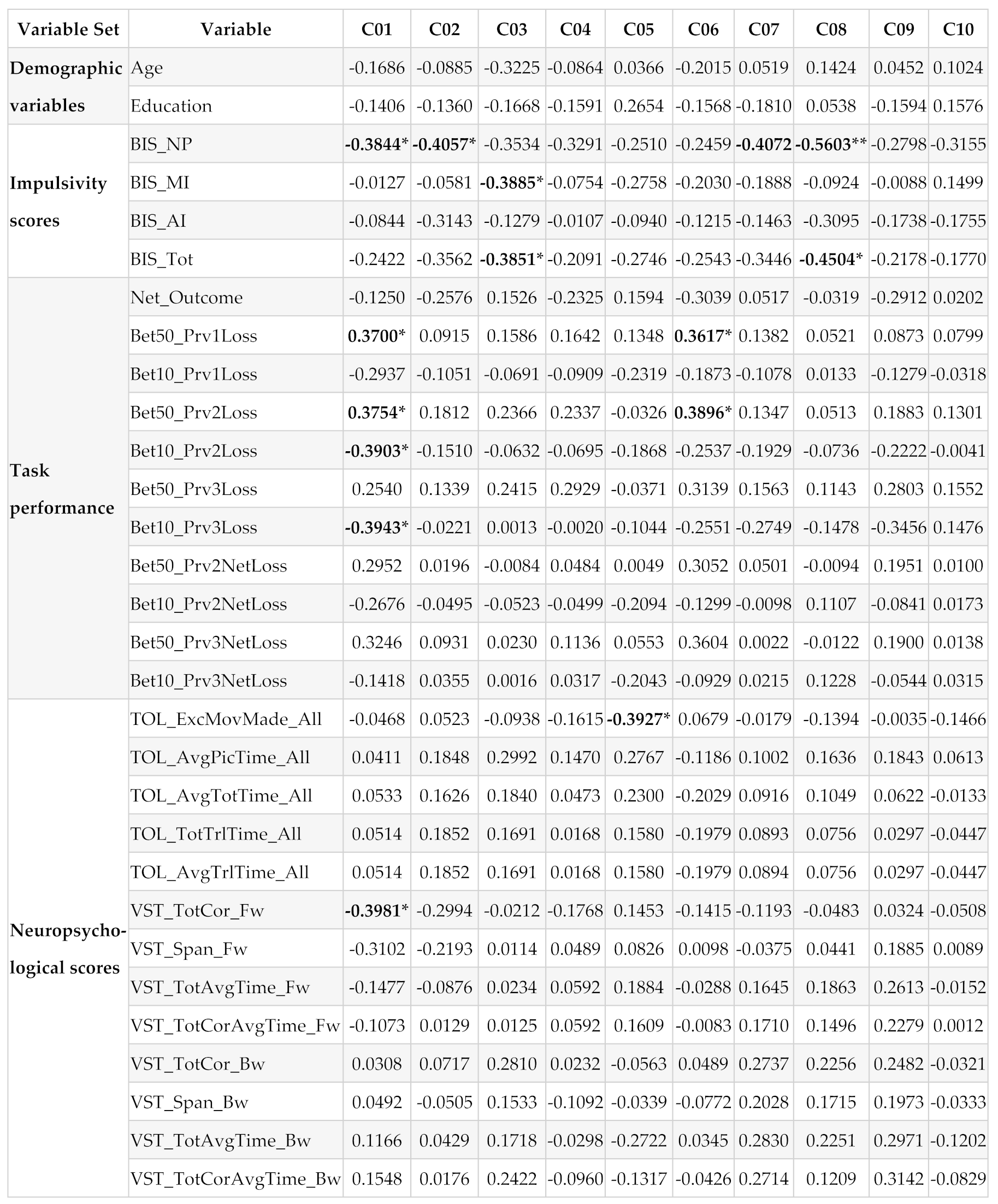

Pearson bivariate correlations between the fMRI clusters (C01-C10) and other variable sets (demographic variables, impulsivity scores, task performance measures, and neuropsychological performance) are shown in

Table 4. While some correlations in each variable set (except in the demographic set) were significant and with moderate-high effect sizes ranging from 0.3617 to 0.5603 [

55], none of these correlations survived multiple testing corrections due to small sample size. When the sample size is small, as in our case, it may be better to rely on the effect size of the correlations rather than on multiple testing corrections on the significant correlations [

53,

54]. Therefore, we have opted to identify significant correlations based on their effect sizes in order to avoid Type 2 error (see

Section 2.7). These significant correlations within each variable set are listed below:

Impulsivity:

- (i)

Negative correlation of BIS non-planning with fMRI activation cluster 1 (R. Ptm; r=-0.3844, p<0.05), cluster 2 (L. Ptm; r=-0.4057, p<0.05), cluster 7 (R. Cdt A-I; r=-0.4073, p<0.05), and cluster 8 (R. Cdt P-S; r=-0.5603, p<0.01); and

- (ii)

Negative correlation of BIS motor impulsivity with cluster 3 (R. SPL; r=-0.3885, p<0.05);

- (iii)

Negative correlation of BIS total impulsivity with cluster 3 (R. SPL; r=-0.3851, p<0.05) and cluster 8 (R. Cdt P-S; r=-0.4504).

Task Performance:

- (i)

Positive correlations between the number of bets with 50 after a loss during the previous trial with the fMRI activation cluster 1 (R. Ptm; r=0.3700, p<0.05) and cluster 6 (R. RoOp; r=0.3617, p<0.05);

- (ii)

Positive correlations between the number of bets with 50 after two consecutive losses during the previous trials with the fMRI activation cluster 1 (R. Ptm; r=0.3754, p<0.05) and cluster 6 (R. RoOp; r=0.3896, p<0.05); and

- (iii)

Negative correlations of the fMRI activation cluster 1 (R. Ptm) with the number of bets with 10 tokens after consecutively losing during the previous two trials (r=-0.3903, p<0.05) as well as with the number of bets with 10 tokens after consecutively losing during the previous three trials (r=-0.3943, p<0.05).

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to elucidate neural substrates of monetary reward outcomes and their association with behavioral and cognitive features. Ten BOLD activation clusters were identified for the win-loss contrast (see

Table 3 and

Figure 2), which included bilateral putamen, right caudate nucleus, right superior and inferior parietal lobule, right angular gyrus, and right rolandic operculum. These anatomical regions showed greater activation during the win condition relative to the loss condition. It was found that all clusters except cluster 5 (left inferior occipital cortex) showed significant positive correlations with other clusters, suggesting that these brain regions were activated together during reward processing. Further, exploratory bivariate correlations with moderate effect sizes suggested possible associations between these reward regions and some behavioral and cognitive characteristics, including: (i) negative correlations between non-planning impulsivity and activations in putamen and caudate regions, (ii) positive correlations between risky bets and right putamen activation, (iii) negative correlations between safer bets and right putamen activation, (iv) a negative correlation between short-term memory capacity and right putamen activity, and (v) a negative correlation between poor planning skills and left inferior occipital cortex activation.

4.1. Neural Substrates of the Win-Loss Contrast

4.1.1. The regions Activated During Reward Processing

The current study identified ten BOLD activation clusters for the win-loss contrast (see

Table 3 and

Figure 2), which include (i) Right Putamen, (ii) Left Putamen, (iii) Right Superior Parietal Lobule, (iv) Right Angular Gyrus, (v) Left Inferior Occipital Cortex, (vi) Right Rolandic Operculum, (vii) Right Caudate (anterior-inferior), (viii) Right Caudate (posterior-superior), (ix) Right Supramarginal Gyrus, and (x) Right Inferior Parietal Lobule. It is worth noting that most of these regions were part of the reward network, as reported by the previous studies [

13,

14]. Our study has identified brain structures of the dorsal striatum, such as putamen (clusters 1 and 2) and caudate nucleus (clusters 7 and 8), which are the core structures of the reward network [

13]. According to Arsalidou et al. [

14], a common reward processing circuit is composed of basal ganglia nuclei such as the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus, and these nuclei represent a basic subcortical structure that subserve reward processes irrespective of the reward outcome type or contextual factors associated with the rewards. Anatomically, both Putamen and caudate project to the globus pallidus, which in turn has projections with the thalamus (Ikemoto et al. 2015). Broadly, the mesocorticolimbic reward system includes dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area to both nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum (i.e., caudate and putamen) as well as orbital frontal cortex (OFC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and amygdala [

56]. Although our study did not implicate the ventral striatum (i.e., nucleus accumbens), putamen and caudate structures are more involved in the monetary reward processing than other basal ganglia structures [

14].

In terms of laterality, eight of the 10 clusters represented the right hemisphere, except the two left-hemisphere clusters. A meta-analysis of fMRI studies on reward processing indicated that monetary rewards activated all the basal ganglia nuclei bilaterally with the exception of the lateral globus pallidus [

14]. In our study, while the putamen was involved bilaterally, only the right caudate was implicated for the win-loss contrast, along with other right hemisphere regions, such as the superior parietal lobule, angular gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and rolandic operculum. The superior parietal lobule is involved in visual attention, spatial perception, visuomotor functions, spatial reasoning, and visual working memory [

57], which are important elements during the evaluation of rewards and risk while performing the visual monetary gambling task as used in our study. On the other hand, regions of the inferior parietal lobule (cluster 10), such as angular gyrus (cluster 4) and supramarginal gyrus (cluster 9), are known to be involved in language ability, future planning, problem-solving, calculations, and other complex mental operations [

58], some of which are essential while processing monetary reward stimuli. Besides, other neuroimaging studies have implicated the inferior parietal lobule to evaluate the possible motor significance of sensory stimuli [

59] and perceptually based decisions and prospective action judgment [

60], the functions that are also essential during the performance of gambling task. The right rolandic operculum (cluster 6) was found to be associated with affective evaluation and depression [

61], possibly with loss outcomes during the performance of a gambling task. Lastly, the left inferior occipital cortex (cluster 5; Brodmann area 18) showed higher activation during loss compared to win outcomes. This secondary visual association cortex is known to be involved in visual processing of color, motion, and depth perception [

62], functions that are practically imperative to perform the gambling task that contains the processing of visual stimuli presented on a computer screen. Overall, most of the brain regions activated for the win-loss contrast in our study are key regions of the reward circuitry and are consistent with the previous findings on monetary reward processing.

4.1.2. Correlations Across the fMRI Activation Clusters

One of the sub-aims of the study is to determine if the reward-related activation clusters are correlated or connected with one another. As shown in

Figure 3, all clusters except cluster 5 (L. IOC) showed significant positive correlations with one or more other regions. Specifically, both the right and left putamen were correlated with each other, which is expected during monetary reward processing [

14]. Further, both clusters of the right caudate (clusters 7 and 8) were highly correlated with each other and with the right putamen (cluster 1), which is supported by the previous findings of bidirectional anatomical connectivity between the putamen and caudate nuclei [

14,

63], suggesting a dynamic interplay between the caudate nucleus and putamen in reward-related, instrumental behaviors [

64]. Further, the right superior parietal lobule (cluster 3) activation is correlated with that of left putamen (cluster 2) and right angular gyrus (cluster 4), possibly suggesting functional connectivity across these regions while processing potential monetary rewards [

65]. Similarly, the right angular gyrus (cluster 4; BA 39) was correlated with the right inferior parietal lobule (cluster 10; BA 40), indicating a strong functional link across these areas of multimodal regions responsible for visuospatial attention and other higher cognitive functions during visual tasks involving stimulus evaluation [

58]. Lastly, the correlation between the right rolandic operculum (cluster 6) and right supramarginal gyrus (cluster 9), which may represent an evaluation of the subjective emotional state associated with gambling outcomes, as these adjacent cortical regions are often related to subjective evaluation of emotions [

61] and the affective states [

66], respectively.

4.2. Associations Between the Reward Regions and Behavioral Features

Exploratory bivariate correlations identified a few important and meaningful associations across the individual variables, with the r-values ranging from 0.3617 to 0.5603, suggesting moderate effect sizes (

Table 4). Further, these associations are relevant and meaningful and may guide future studies to examine them systematically. Therefore, it is worth discussing these associations in a broader context.

4.2.1. Associations Between the Reward Regions and Impulsivity

Exploratory bivariate correlations identified a few negative correlations between impulsivity and fMRI activation clusters (

Table 4), which include (i) non-planning impulsivity with all four striatal structures such as the bilateral putamen and right caudate (clusters 1, 2, 7, and 8), (ii) motor impulsivity with right superior parietal lobule (cluster 3), and (iii) total impulsivity with right superior parietal lobule (cluster 3) and with right caudate (cluster 8). These findings indicate that higher impulsivity was associated with lower activation in those regions for the contrast of win-loss. In other words, those with heightened impulsivity showed either lower activation during the win processing or higher activation during the loss condition, and vice-versa may be true for those with lower impulsivity. While the theories of choice and decision-making posit that loss looms larger than gain in most individuals [

67], our findings indicate that sensitivity to loss is reflected more in those with higher impulsivity. Specifically, all four clusters representing core reward structures of the striatum were correlated with this non-planning impulsivity, a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences [

25], suggesting that impulsive people manifest an urge for immediate gratification, regardless of whether the immediate reward is certain or uncertain [

21]. On the other hand, motor impulsivity and total impulsivity showed a negative association with the right superior parietal lobule, a region that is modulated by the reward amount and its probability while performing decision-making tasks [

68]. Although the total impulsivity score was also correlated with the right caudate (cluster 8), this was mostly contributed by the non-planning score. Interestingly, there were no significant correlations of age and education with any of the fMRI activation clusters.

4.2.2. Associations Between the Reward Regions and Gambling Performance

With regard to associations between performance variables of the gambling task and the fMRI activation clusters, the exploratory analysis identified a few meaningful correlations (

Table 4). Interestingly, the right putamen (cluster 1) showed (i) positive correlations with risky choice such as betting with 50 (bigger amount) following a loss during previous trial and previous two trials of the gambling task and (ii) negative correlations with safer choice such as betting with 10 (smaller amount) following a loss during previous two and three trials. This finding of higher activation of the right putamen for risky bets and lower activation for safer or less risky bets suggests that the right putamen is modulated by how much is at stake and how much risk or loss is anticipated (i.e., loss sensitivity) during each trial. This finding is consistent with that of other studies that putamen was associated with the stimulus-action-reward association [

28] and low putamen activity was associated with poor reward sensitivity [

29]. Further, the risky choices (i.e., higher bets in the face of previous loss) were also positively correlated with the right rolandic operculum (cluster 6), a cortical region associated with negative affective states such as apathy, depression, anxiety, and perceived stress [

61], possibly representing a stressful state of anticipating a potential negative outcome during the gambling task. While our findings are very meaningful in the context of neural correlates underlying reward processing during a monetary gambling task, more studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further confirm and explain these preliminary findings.

4.2.3. Associations Between the Reward Regions and Neuropsychological Scores

The results from the current study also pointed at a couple of associations between neuropsychological variables and the fMRI activation clusters (

Table 4). First, a negative correlation was observed between right putamen activation and the total correct score of the total items correctly remembered during the visual span test, representing short-term memory capacity. This may indicate that individuals who had poor short-term memory capacity showed relatively higher activation during the win condition (compared to the loss condition), or conversely, those with higher short-term memory capacity showed lower activation for the win condition (relative to the loss condition). In other words, putamen activation during reward processing varied based on the short-term memory capacity of the individuals. A previous study reported that putamen may modulate working memory [

31] during a delayed-response task that required memory updating. Putamen was also found to modulate cognitive functions in general [

32] and learning and memory in particular [

33,

34]. It is possible that basal ganglia and medial temporal lobe memory systems work together in a complementary manner based on the task at hand [

69]. However, more studies are needed to confirm the exact role of putamen under specific task conditions.

Further, one of the fMRI activation clusters, the left inferior occipital cortex, was negatively correlated with the number of excess moves made (i.e., poor planning) during the Tower of London Test, suggesting that higher activation of this brain region was associated with better cognitive planning. Although the inferior occipital cortex (Brodmann area 18), which is the secondary visual association cortex, does not have a specific role in reward processing per se, it is shown to be activated during visual-spatial tasks requiring visual attention to process and integrate various features of visual stimuli including color, shape, texture, and brightness [

70] and to identify objects representing specific contexts [

71]. While it is understandable that the Tower of London test, a visual task presented with initial and target positions of beads in different colors, would require a strong involvement of the inferior occipital cortex during task performance, the association of its activation level with cognitive planning ability is a novel finding, which may require further empirical support and interpretation.

4.2.4. Clinical Implications

Empirical evidence supports reward-network dysfunction in substance-use disorders [

72] and other psychiatric disorders [

73]. Problems with both impulsivity and reward processing underlie several psychiatric disorders [

74], including substance use disorders [

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80], attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [

81,

82], antisocial personality [

83,

84], conduct disorder [

85,

86], borderline personality disorder [

87,

88], eating disorder [

89,

90], and gambling addiction [

91,

92]. Therefore, elucidating specific brain regions activated during various aspects of reward processing is essential to understanding, diagnosing, and treating these disorders [

4,

7,

93], as specific abnormalities in reward processing can be observed in different forms of psychopathology [

4]. Further, elucidation of reward dysfunction across a range of diagnostic categories may help to refine the phenotypes of brain structure and function and thus improve the prediction of onset and recovery of these disorders [

94]. Furthermore, a better understanding of disorder-specific and/or symptoms-specific neural correlates of reward processing will help refine brain-based treatment techniques, such as brain stimulation and neurofeedback, in the management of substance use disorders and other related psychiatric disorders [

95,

96,

97]. Lastly, elucidation of individualized brain connectome-based individual’s symptom profile will help optimize personalized medicine approaches to treating a range of reward-related disorders [

98].

4.2.5. Limitations and Suggestions

While our study has produced some interesting findings, it has a few limitations. First of all, the sample size is relatively small, limiting the power needed to elicit associations between the clusters and the behavioral features. Second, the sample consisted of only males, and therefore, the results are not generalizable to both genders. Third, the age range (19-38) is wide, and brain development and behavioral characteristics may vary between those in their 20s and 30s. Finally, the current study has only analyzed the win-loss contrast; other relevant contrasts (e.g., larger vs. smaller rewards, risky vs. safe bets, etc.) may also be important aspects of reward processing. We suggest conducting future studies with larger sample sizes consisting of both males and females to enhance the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Future studies of a similar gambling task should analyze different age cohorts to examine reward processing across different developmental stages. Future studies may also consider examining other contrasts and paradigms of reward processing while also examining different measures (e.g., functional connectivity).

5. Conclusions

The current study was designed to elicit neural substrates underlying reward evaluations of win versus loss outcomes in a monetary gambling paradigm as well as to understand possible associations of these brain regions with behavioral characteristics such as impulsivity, task performance, and neuropsychological measures. Findings revealed that a set of key brain structures, such as putamen, caudate nucleus, superior and inferior parietal lobule, angular gyrus, and Rolandic operculum, showed greater activation during win relative to loss condition, and most of them were highly correlated with each other. Although the multivariate canonical correlation analyses failed to elicit associations between the anatomical regions and behavioral characteristics, exploratory bivariate correlations were significant with moderate effect sizes. Additionally, some of these reward-related regions showed meaningful associations with specific features of impulsivity, task performance, and neuropsychological measures. Further studies with larger samples are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.K., B.P., B.A.A., A.K.P.; Methodology: C.K., B.P., B.A.A., A.K.P., S.K.; Data Collection: B.A.A.; Data Curation: B.A.A., C.K.; Formal Analysis: C.K.; Manuscript Preparation: C.K., B.A.A., B.P.; Review and Editing: B.P., B.A.A., A.K.P., S.K., G.P., J.L.M., W.K.; Funding Acquisition: B.P., C.K., J.L.M., A.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the grants (R01 AA002686 to Bernice Porjesz (PI) and R01 AA028848 to Bernice Porjesz (PI), Chella Kamarajan (MPI), Jacquelyn Meyers (MPI), Ashwini Pandey (MPI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University and Nathan Kline Institute (IRB approval ID: SUNY–266893; NKI–212263).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will be made available to the researchers upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In memory of Henri Begleiter, founder and longtime mentor of the Neurodynamics Laboratory, we acknowledge with great admiration his seminal scientific contributions to the field. We are sincerely indebted to his charismatic leadership and luminous guidance, truly inspired by his scientific mission and vision, and highly motivated to carry forward the work he fondly cherished. We are grateful for the valuable technical assistance of Carlene Haynes, Joyce Alonzia, Chamion Thomas, Alec Musial, Kristina Horne, Talia Stern, and Abigail Freeman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MGT |

Monetary Gambling Task |

| BOLD |

Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| BIS |

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale |

| TOL |

Tower of London Test |

| VST |

Visual Span Test |

| MPRAGE |

Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo |

| ART |

Automatic Registration Toolbox |

| sPCA |

Sparse Principal Component Analysis |

References

- O'Doherty, J.P.; Cockburn, J.; Pauli, W.M. Learning, Reward, and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Garcia, I.; Horstmann, A.; Jurado, M.A.; Garolera, M.; Chaudhry, S.J.; Margulies, D.S.; Villringer, A.; Neumann, J. Reward processing in obesity, substance addiction and non-substance addiction. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Admon, R.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Dysfunctional Reward Processing in Depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 4, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zald, D.H.; Treadway, M.T. Reward Processing, Neuroeconomics, and Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

OpenStax; Lumen Learning. Reinforcement and Punishment. In General Psychology, Pressbooks: Montreal, Canada, 2024.

- Medvedev, D.; Davenport, D.; Talhelm, T.; Li, Y. The motivating effect of monetary over psychological incentives is stronger in WEIRD cultures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, G.S.; Damiano, C.A.; Allen, J.A. Reward circuitry dysfunction in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and genetic syndromes: animal models and clinical findings. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2012, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; Nelson, E.E.; McClure, E.B.; Monk, C.S.; Munson, S.; Eshel, N.; Zarahn, E.; Leibenluft, E.; Zametkin, A.; Towbin, K.; et al. Choice selection and reward anticipation: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 2004, 42, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zald, D.H.; Boileau, I.; El-Dearedy, W.; Gunn, R.; McGlone, F.; Dichter, G.S.; Dagher, A. Dopamine transmission in the human striatum during monetary reward tasks. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 4105–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivegna, F.; Papachristou, E.; Flouri, E. A scoping review on self-regulation and reward processing measured with gambling tasks: Evidence from the general youth population. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0301539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, S.M.; York, M.K.; Montague, P.R. The neural substrates of reward processing in humans: the modern role of FMRI. Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.M.; Plate, R.C.; Ernst, M. A systematic review of fMRI reward paradigms used in studies of adolescents vs. adults: The impact of task design and implications for understanding neurodevelopment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.S.; Smith, D.V.; Delgado, M.R. Using fMRI to study reward processing in humans: past, present, and future. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 115, 1664–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsalidou, M.; Vijayarajah, S.; Sharaev, M. Basal ganglia lateralization in different types of reward. Brain Imaging Behav 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hairston, J.; Schrier, M.; Fan, J. Common and distinct networks underlying reward valence and processing stages: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011, 35, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, D.; Volkow, N.D. Functional connectivity of substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area: maturation during adolescence and effects of ADHD. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, J.S.; Riedel, M.C.; Bottenhorn, K.L.; Poudel, R.; Salo, T.; Hill-Bowen, L.D.; Laird, A.R.; Sutherland, M.T. Meta-analytic clustering dissociates brain activity and behavior profiles across reward processing paradigms. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 20, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarajan, C.; Ardekani, B.A.; Pandey, A.K.; Kinreich, S.; Pandey, G.; Chorlian, D.B.; Meyers, J.L.; Zhang, J.; Bermudez, E.; Kuang, W. , et al. Differentiating Individuals with and without Alcohol Use Disorder Using Resting-State fMRI Functional Connectivity of Reward Network, Neuropsychological Performance, and Impulsivity Measures. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2022, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhao, G.; Feng, Q.; Guan, S.; Im, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, P.; Jia, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, Y. , et al. The computational and neural substrates of individual differences in impulsivity under loss framework. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e26808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarajan, C.; Rangaswamy, M.; Tang, Y.; Chorlian, D.B.; Pandey, A.K.; Roopesh, B.N.; Manz, N.; Saunders, R.; Stimus, A.T.; Porjesz, B. Dysfunctional reward processing in male alcoholics: an ERP study during a gambling task. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialaszek, W.; Gaik, M.; McGoun, E.; Zielonka, P. Impulsive people have a compulsion for immediate gratification-certain or uncertain. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarajan, C.; Ardekani, B.A.; Pandey, A.K.; Kinreich, S.; Pandey, G.; Chorlian, D.B.; Meyers, J.L.; Zhang, J.; Bermudez, E.; Stimus, A.T. , et al. Random Forest Classification of Alcohol Use Disorder Using fMRI Functional Connectivity, Neuropsychological Functioning, and Impulsivity Measures. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2020, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Schlagenhauf, F.; Wustenberg, T.; Hein, J.; Kienast, T.; Kahnt, T.; Schmack, K.; Hagele, C.; Knutson, B.; Heinz, A. , et al. Ventral striatal activation during reward anticipation correlates with impulsivity in alcoholics. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekhof, E.K.; Nerenberg, L.; Falkai, P.; Dechent, P.; Baudewig, J.; Gruber, O. Impulsive personality and the ability to resist immediate reward: an fMRI study examining interindividual differences in the neural mechanisms underlying self-control. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2012, 33, 2768–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, F.G.; Barratt, E.S.; Dougherty, D.M.; Schmitz, J.M.; Swann, A.C. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, J.H.; Stanford, M.S.; Barratt, E.S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 51, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Dresler, T.; Ehlis, A.C.; Plichta, M.M.; Heinzel, S.; Polak, T.; Lesch, K.P.; Breuer, F.; Jakob, P.M.; Fallgatter, A.J. Neural response to reward anticipation is modulated by Gray's impulsivity. Neuroimage 2009, 46, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruno, M.; Kawato, M. Different neural correlates of reward expectation and reward expectation error in the putamen and caudate nucleus during stimulus-action-reward association learning. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, K.; Kawatani, J.; Tajima, K.; Sasaki, A.T.; Yoneda, T.; Komi, M.; Hirai, T.; Tomoda, A.; Joudoi, T.; Watanabe, Y. Low putamen activity associated with poor reward sensitivity in childhood chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuroimage Clin 2016, 12, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, R.M.; Boehler, C.N.; Roberts, K.C.; Song, A.W.; Woldorff, M.G. The involvement of the dopaminergic midbrain and cortico-striatal-thalamic circuits in the integration of reward prospect and attentional task demands. Cereb. Cortex 2012, 22, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; FitzGerald, T.H.; Friston, K.J. Working memory and anticipatory set modulate midbrain and putamen activity. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 14040–14047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefcsik, T.; Nemeth, D.; Janacsek, K.; Hoffmann, I.; Scialabba, J.; Klivenyi, P.; Ambrus, G.G.; Haden, G.; Vecsei, L. The role of the putamen in cognitive functions — A case study. Learning & Perception 2009, 1, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.Y.; Song, C.; Wu, Y.; Mo, L.; Guo, Z.; Liu, S.H.; Bao, X. Learning and memory deficits caused by a lesion in the medial area of the left putamen in the human brain. CNS Spectr 2009, 14, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlberg, C.; Goerg, S.; Rullmann, M.; Hesse, S.; Sabri, O.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Classen, J.; Fricke, C.; Rumpf, J.J. Motor learning is modulated by dopamine availability in the sensorimotor putamen. Brain Commun 2024, 6, fcae409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovelli, K.; Allegretta, R.A. Framing decision-making: the role of executive functions, cognitive bias and reward. Neuropsychological Trends 2023, 33, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, B.A.; Braun, M.; Hutton, B.F.; Kanno, I.; Iida, H. A fully automatic multimodality image registration algorithm. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1995, 19, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.W. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput. Biomed. Res. 1996, 29, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, B.A.; Bappal, A.; D'Angelo, D.; Ashtari, M.; Lencz, T.; Szeszko, P.R.; Butler, P.D.; Javitt, D.C.; Lim, K.O.; Hrabe, J. , et al. Brain morphometry using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: application to schizophrenia. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Andersson, J.; Ardekani, B.A.; Ashburner, J.; Avants, B.; Chiang, M.C.; Christensen, G.E.; Collins, D.L.; Gee, J.; Hellier, P. , et al. Evaluation of 14 nonlinear deformation algorithms applied to human brain MRI registration. Neuroimage 2009, 46, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Davis, B.; Jomier, M.; Gerig, G. Unbiased diffeomorphic atlas construction for computational anatomy. Neuroimage 2004, 23 Suppl 1, S151–S160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, C.G.; Carew, J.D.; Alexander, A.L.; Basser, P.J.; Meyerand, M.E. Investigation of anomalous estimates of tensor-derived quantities in diffusion tensor imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 55, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstrand, K.; Lund, T.E.; Madsen, K.H.; Larsen, R. Sparse PCA, a new method for unsupervised analyses of fMRI data. In Proc. International Society of Magnetic Resonance In Medicine-ISMRM; pp. 1-1.

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T.; Huang, C.C.; Lin, C.P.; Feng, J.; Joliot, M. Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage 2020, 206, 116189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reise, S.P.; Moore, T.M.; Sabb, F.W.; Brown, A.K.; London, E.D. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11: reassessment of its structure in a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, M.S.; Mathias, C.W.; Dougherty, D.M.; Lake, S.L.; Anderson, N.E.; Patton, J.H. Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2009, 47, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallice, T. Specific impairments of planning. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1982, 298, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berch, D.B.; Krikorian, R.; Huha, E.M. The Corsi block-tapping task: methodological and theoretical considerations. Brain Cogn. 1998, 38, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, B. Interhemispheric differences in the localization of psychological processes in man. Br. Med. Bull. 1971, 27, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.P.; Keller, F. Colorado Assessment Tests (CATs), Version 1.2; Colorado Springs, Colorado, 2002.

- Pandey, A.K.; Ardekani, B.A.; Kamarajan, C.; Zhang, J.; Chorlian, D.B.; Byrne, K.N.; Pandey, G.; Meyers, J.L.; Kinreich, S.; Stimus, A. , et al. Lower Prefrontal and Hippocampal Volume and Diffusion Tensor Imaging Differences Reflect Structural and Functional Abnormalities in Abstinent Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 1883–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R. Correction for multiple testing: is there a resolution? Chest 2011, 140, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using Effect Size-or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.F. Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestler, E.J.; Carlezon, W.A., Jr. The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Fan, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Fox, P.T.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Yu, C.; Jiang, T. Convergent functional architecture of the superior parietal lobule unraveled with multimodal neuroimaging approaches. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 36, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numssen, O.; Bzdok, D.; Hartwigsen, G. Functional specialization within the inferior parietal lobes across cognitive domains. Elife 2021, 10, e63591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, I.; Thoenissen, D.; Zilles, K. Movement preparation and motor intention. Neuroimage 2001, 14, S110–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L.M.; Fox, P.T.; Downs, J.H.; Glass, T.; Hirsch, T.B.; Martin, C.C.; Jerabek, P.A.; Lancaster, J.L. Use of implicit motor imagery for visual shape discrimination as revealed by PET. Nature 1995, 375, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutoko, S.; Atsumori, H.; Obata, A.; Funane, T.; Kandori, A.; Shimonaga, K.; Hama, S.; Yamawaki, S.; Tsuji, T. Lesions in the right Rolandic operculum are associated with self-rating affective and apathetic depressive symptoms for post-stroke patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaas, J.H. Evolution of Visual Cortex in Primates. In Evolution of Nervous Systems, Kaas, J.H., Ed. Academic Press: Oxford, 2017; pp. 187-201. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-804042-3.00080-4.

- Parent, A.; Hazrati, L.N. Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. I. The cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1995, 20, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brovelli, A.; Nazarian, B.; Meunier, M.; Boussaoud, D. Differential roles of caudate nucleus and putamen during instrumental learning. Neuroimage 2011, 57, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarbo, K.; Verstynen, T.D. Converging structural and functional connectivity of orbitofrontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, and posterior parietal cortex in the human striatum. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 3865–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silani, G.; Lamm, C.; Ruff, C.C.; Singer, T. Right supramarginal gyrus is crucial to overcome emotional egocentricity bias in social judgments. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 15466–15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, S.; Deng, K.; Zhang, B.; Im, H.; Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, G.; He, Q. , et al. Distributed attribute representation in the superior parietal lobe during probabilistic decision-making. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 5693–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packard, M.G.; Knowlton, B.J. Learning and memory functions of the Basal Ganglia. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 25, 563–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavina-Pratesi, C.; Kentridge, R.W.; Heywood, C.A.; Milner, A.D. Separate processing of texture and form in the ventral stream: evidence from FMRI and visual agnosia. Cereb. Cortex 2010, 20, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, K.L.; Amsalem, O.; Sugden, A.U.; Ramesh, R.N.; Fernando, J.; Burgess, C.R.; Andermann, M.L. Visual association cortex links cues with conjunctions of reward and locomotor contexts. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 1563–1576.e1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalivas, P.W.; Volkow, N.D. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujara, M.; Koenigs, M. Mechanisms of reward circuit dysfunction in psychiatric illness: prefrontal-striatal interactions. Neuroscientist 2014, 20, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, A.C.; Bjork, J.M.; Moeller, F.G.; Dougherty, D.M. Two models of impulsivity: relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 988–994. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.J.; Moeller, F.G.; Rhoades, H.M.; Cherek, D.R. Impulsivity and history of drug dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998, 50, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Petry, N.M. Substance abuse, pathological gambling, and impulsiveness. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001, 63, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dawe, S.; Gullo, M.J.; Loxton, N.J. Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: implications for substance misuse. Addict. Behav. 2004, 29, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict. Biol. 2009, 14, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, S.F.; Gudleski, G.D.; Saladin, M.E.; Brady, K.T. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, G.; Jimenez, M.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Martinez, I.; Iribarren, M.M.; Jimenez-Arriero, M.A.; Ponce, G.; Avila, C. Varieties of impulsivity in males with alcohol dependence: the role of Cluster-B personality disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007, 31, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R. Underlying processes in the poor response inhibition of children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Atten Disord 2003, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, C.; Kleinert, J.; Steinmann, S.; Fuger, U.; Leicht, G.; Mulert, C. Oscillatory responses to reward processing in borderline personality disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselbrock, M.N.; Hesselbrock, V.M. Relationship of family history, antisocial personality disorder and personality traits in young men at risk for alcoholism. J. Stud. Alcohol 1992, 53, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, A.C.; Lijffijt, M.; Lane, S.D.; Steinberg, J.L.; Moeller, F.G. Trait impulsivity and response inhibition in antisocial personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherek, D.R.; Lane, S.D. Effects of d,l-fenfluramine on aggressive and impulsive responding in adult males with a history of conduct disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1999, 146, 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan, N.; Rubia, K.; Conrod, P.J. Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, K.A.; Allen, J.S.; Chanen, A.M. Impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: reward-based decision-making and its relationship to emotional distress. J Pers Disord 2010, 24, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reekum, R.; Links, P.S.; Fedorov, C. Impulsivity in borderline personality disorder. In Biological and neurobehavioral studies of borderline personality disorder., Silk, K.R., Ed. Washington, DC, US: American Psychiatric Association: 1994; pp. 1-22.

- Hege, M.A.; Stingl, K.T.; Kullmann, S.; Schag, K.; Giel, K.E.; Zipfel, S.; Preissl, H. Attentional impulsivity in binge eating disorder modulates response inhibition performance and frontal brain networks. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2015, 39, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawe, S.; Loxton, N.J. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2004, 28, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.A.; Potenza, M.N. Neurodevelopment, impulsivity, and adolescent gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 2003, 19, 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski, A.; Steel, Z.; McConaghy, N. Impulsivity in pathological gambling: the antisocial impulsivist. Addiction 1997, 92, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, D.T.; Roth, R.M.; Green, A.I. The neural circuitry of reward and its relevance to psychiatric disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2004, 6, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin-Sommers, A.R.; Foti, D. Abnormal reward functioning across substance use disorders and major depressive disorder: Considering reward as a transdiagnostic mechanism. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015, 98, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrossy, M.D.; Ramanathan, C.; Ashouri Vajari, D.; Tong, Y.; Schlaepfer, T.; Coenen, V.A. Neuromodulation in Psychiatric disorders: Experimental and Clinical evidence for reward and motivation network Deep Brain Stimulation: Focus on the medial forebrain bundle. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.J., 3rd; Hanlon, C.A.; Marshalek, P.J.; Rezai, A.R.; Krinke, L. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and other forms of neuromodulation for substance use disorders: Review of modalities and implications for treatment. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 418, 117149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.K.; Dunlop, K.; Downar, J. Cortico-Striatal-Thalamic Loop Circuits of the Salience Network: A Central Pathway in Psychiatric Disease and Treatment. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollunder, B.; Rajamani, N.; Siddiqi, S.H.; Finke, C.; Kuhn, A.A.; Mayberg, H.S.; Fox, M.D.; Neudorfer, C.; Horn, A. Toward personalized medicine in connectomic deep brain stimulation. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 210, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).