1. Introduction

Video games are now played by ~ 3.3 billion people worldwide [

1], generating >US

$180 billion annually. While benefits ranging from improved attention to surgical precision have been documented, the structural correlates of prolonged play—especially for

action genres that tax visuomotor circuits—remain incompletely understood.Video games have become an integral part of modern entertainment, with research showing that consistent gameplay can lead to noticeable changes in brain structure and function. [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] Studies have highlighted that video gaming can affect brain regions associated with visuospatial abilities, motor control, and attentional processes, suggesting that gaming experience may shape cognitive and neural development. [

7,

8,

9,

10] Structural neuroimaging studies have reported alterations in cortical thickness [

11] and white matter integrity [

12] in individuals who regularly play video games (VGPs), indicating that the brain undergoes adaptive modifications in response to the cognitive and sensorimotor demands of gaming activities. As a result, researchers are increasingly interested in exploring the long-term effects of video game exposure both beneficial and detrimental. [

3,

13,

14] On the one hand, gaming has been linked to cognitive, emotional, motivational, and social benefits,¹² such as improvements in reaction time, decision-making, and attention control. Conversely, concerns have been raised about potential negative effects, including exposure to violent content, gaming addiction [

15], obesity, and various cardio-metabolic health risks. [

16] Systematic reviews of video gaming’s effects on the brain have highlighted structural and functional adaptations observed through MRI studies, with changes linked to enhanced neuroplasticity, improved cognitive functions, and superior visuospatial skills. [

3,

13,

17] However, despite increasing evidence of neuroplastic adaptations, the extent to which different gaming genres influence brain structure remains uncertain.

One key structural change linked to the action video gaming experience is cortical thickness, a well-established marker of grey matter integrity, plasticity, and cognitive function. [

18] Increased cortical thickness has been associated with enhanced neural efficiency, increased dendritic complexity, and reduced synaptic pruning, all of which may contribute to superior visuospatial and sensorimotor performance [

11,

17,

19]. Given the high cognitive and perceptual demands of action video games, regions involved in spatial attention, decision-making, and motor coordination such as the parietal cortex may be particularly affected. [

2,

11,

19,

20] However, gray matter alone does not fully capture the structural changes in the brain associated with gaming. White matter connectivity plays a crucial role in facilitating communication between brain regions, with greater connectivity supporting more efficient cognitive processing and sensorimotor coordination. [

21]

Diffusion-based imaging techniques assess microstructural white matter properties, with quantitative anisotropy (QA) serving as a marker of axonal density and connectivity strength. [

22,

23] Since action video games require rapid visuomotor integration, it is essential to investigate whether changes in cortical thickness are accompanied by strengthened white matter connectivity along visuospatial processing pathways. These games predominantly engage the occipital and parietal regions within the dorsal stream—the "where" pathway—which plays a crucial role in perception-action coupling. [

24,

25] This study examines structural brain changes associated with action video gaming, with a focus on cortical thickness and white matter integrity in the dorsal stream—a key network for visuospatial processing, perceptual decision-making, and motor planning.

2. Materials and Methods

- 2.

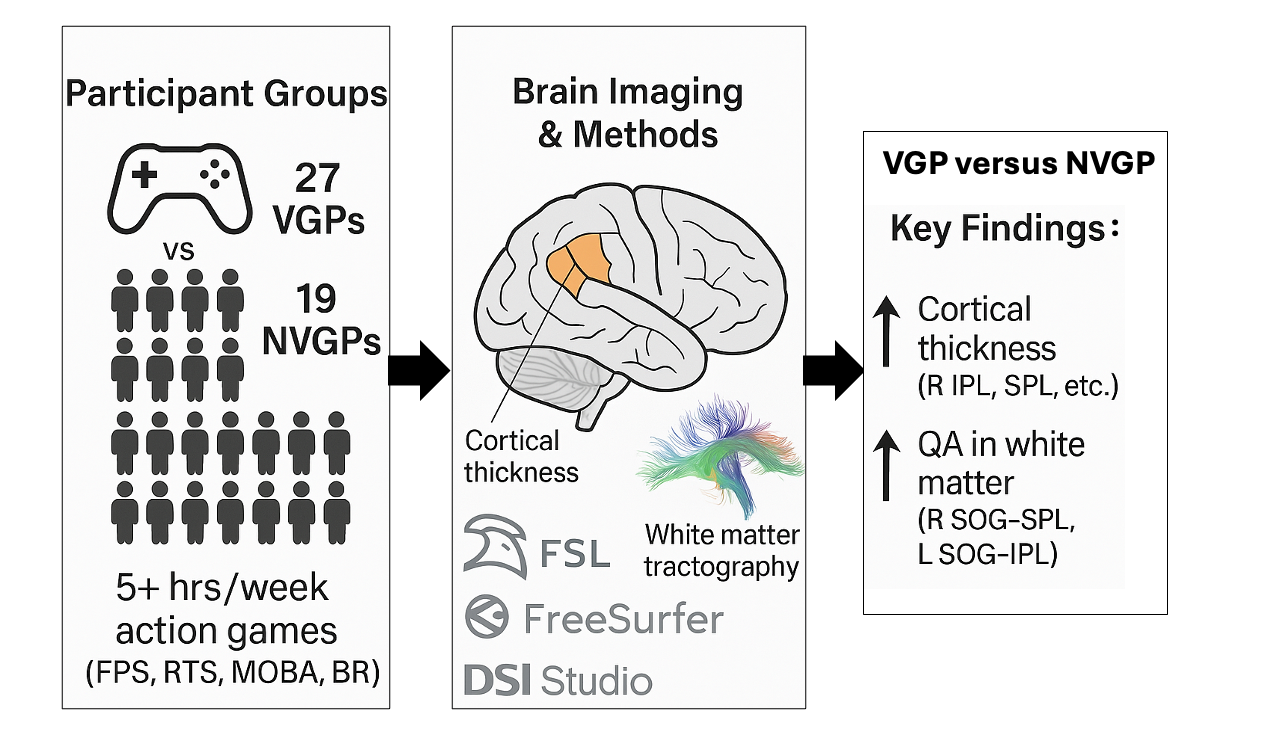

>2.1.1. Subject Data

The number of participants for the structural connectivity analysis was 46 total participants (27 video game players – gamers (20 ± 2 years of age), and 19 non-video game players, non-gamers (20 ± 2 years of age)). Participants were recruited by posting flyers physically and digitally on approved areas at Georgia State University and neighboring universities in the Atlanta areas and by advertising on regional video game group Facebook pages. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire about their video gaming habits to determine their group classification, following guidelines like those used in prior studies by Green and Bavelier [

26,

27,

28] and others (e.g., Gao et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2020). [

29,

30]

A participant was categorized as a video game player (VGP) if they reported playing video games for at least 5 hours per week over the past year, consistent with the criteria set by Green and Bavelier, who used a similar threshold of 5 hours per week over six months. Those who reported playing more than 5 hours weekly in one of four specific game genres—First-Person Shooter (FPS), Real-Time Strategy (RTS), Multiplayer Online Battle Arena (MOBA), or Battle Royale (BR)—during the previous two years were also considered VGPs. Non-video game players (NVGPs) who were recruited for this study played less than 30 minutes per week over the last two years prior to data collection. All participants passed the Ishihara test for color vision deficiency. [

31] Before participation, they provided written informed consent and completed health screenings. Compensation was provided for their involvement, and the study received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of Georgia State University and Georgia Institute of Technology, located in Atlanta, Georgia.

Whole-brain T1 and diffusion MR imaging was conducted on a 3 T Siemens Magnetom Prisma MRI scanner (Siemens, Atlanta, GA, USA) at the joint Georgia State University and Georgia Institute of Technology Center for Advanced Brain Imaging, Atlanta, GA, USA. High-resolution anatomical MR images were acquired for voxel-based morphometry and anatomical reference using a T1-MEMPRAGE scan sequence (TR = 2530 ms; TE1-4: 1.69–7.27 ms; TI = 1260 ms; flip angle = 7 deg; voxel size 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm). [

9] Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data were acquired using a multishell diffusion scheme with b-values of 300, 650, 1000, and 2000 s/mm², corresponding to 4, 17, 39, and 68 diffusion-encoding directions, respectively. One non-diffusion-weighted (b = 0) volume was also collected. The acquisition was performed using a single-shot echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with anterior-to-posterior (AP) phase encoding. Each diffusion volume consisted of 60 axial slices acquired with 2 mm isotropic resolution (slice thickness = 2 mm, in-plane resolution = 2 × 2 mm). The field of view (ReadoutFOV) was 220 mm, and the acquisition parameters were TR = 2750 ms, TE = 79 ms. The total scan duration was approximately 6.5 minutes.

Structural Data Analysis Pipeline

The anatomical data processing and morphometric parameter estimation were carried out using the ‘recon-all’ pipeline in FreeSurfer (ver. 7.4.1) available at

https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/. [

32,

33] Processing was performed on a macOS system equipped with Apple Silicon (M2 Pro chip), 32 GB RAM, and integrated GPU acceleration.

Head motion artifacts were corrected using intensity normalization and rigid-body alignment to ensure that minor movements during scanning did not compromise the results. [

34] Each brain was transformed into Talairach space and underwent cortical and subcortical segmentation based on the Desikan-Killiany atlas. [

35] Additional details can be found in earlier studies. [

32,

36,

37,

38]

Subject-specific cortical thickness (CT) for bilateral cortical regions and intracranial volume (ICV, representing head size) were assessed using the mri_surf2surf, mris_anatomical_stats, and aparcstats2table tools, as part of the FreeSurfer recon-all pipeline. [

36] The whole brain was parcellated into 70 cortical regions (35 in each hemisphere) based on Desikan’s atlas. [

35]

Quality control was rigorously performed by visually inspecting raw structural images, skull-stripped volumes, and reconstructed pial surfaces within FreeSurfer’s visual tools (e.g., Freeview). Criteria for quality control included accurate skull stripping without visible dura, consistent cortical ribbon delineation, and correct anatomical segmentation. Manual interventions such as control point edits, brain mask adjustments, and pial surface regeneration commands (

recon-all -autorecon-pial -subjid subjectID) were used to correct identified segmentation and normalization errors. [

39]

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed to examine the effects of the independent variable (group) on the dependent variables (thickness of 70 ROIs in the brain), with total intracranial volume (ICV) included as a covariate. Main effects and interactions were assessed, with statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.05, and effect sizes were reported using F-values and partial eta squared (ηp²) values.

Our study focuses on the dorsal stream because these regions are directly involved in the processing and integrating of visuomotor information, which is central to our task involving moving visual stimuli. [

40,

41] Thus, our choice of ROIs reflects the specific neural mechanisms underpinning the task we investigated, rather than those associated with higher-order, reward-based decision-making. In our investigation, we examined the structural organization of the dorsal streams using six regions of interest (ROIs) The ROI coordinates were derived from a prior study on the visual streams and are listed in

Table 1. [

42] The identified ROIs comprising the dorsal stream encompassed six regions including the bilateral inferior parietal lobule (IPL), superior parietal lobule (SPL). The nomenclature used in this classification was based on the Eickhoff–Zilles macro-labels from N27 and was implemented in AFNI. [

42]

We employed the MNI coordinate system and constructed the ROIs using the FSLeyes visualization tool within the FSL version 6.0.6 (FMRIB Software Library) environment. The functional connectivity analysis utilized 6 mm radius ROIs using the same MNI coordinates. Statistical comparison of connectivity metrics between ROIs across gamers and nongamers was carried out using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (also known as the Mann–Whitney U test). This nonparametric test was chosen because it does not assume the normality of the connectivity metrics’ distribution, making it suitable for comparing the two groups without requiring any assumptions about the underlying distribution of the data. For multiple comparison corrections in this analysis, we employed the Holm–Bonferroni method. [

43,

44] This method was selected for its ability to enhance statistical power and sensitivity to individual significant comparisons while effectively controlling for Type I errors. We applied a significance threshold of

p < 0.05, with the Holm–Bonferroni correction indicated by

p*, to ensure statistical significance while simultaneously controlling for the family-wise error rate in the dorsal stream, providing a robust framework for identifying meaningful differences in connectivity metrics.

DSI Studio version 2022.08.0 is a non-commercial software program that was utilized in this study for diffusion MR image analysis and provided functions including deterministic fiber tracking and 3D visualization [

22]. We used a multi-shell diffusion scheme with b-values of 300, 650, 1000, and 2000 s/mm². The acquisition parameters consisted of an in-plane resolution of 2 mm and a slice thickness of 2 mm. The accuracy of b-table orientation was examined by comparing fiber orientations with those of a population-averaged template [

45]. Diffusion-weighted images were preprocessed using the EDDY tool implemented via DSI Studio, which corrected for eddy current–induced distortions and motion artifacts. Reverse phase-encoding images were not acquired; therefore, susceptibility distortion correction using TOPUP was not applicable. The tensor metrics were then calculated.

The diffusion data were reconstructed in the MNI space using q-space diffeomorphic reconstruction [

23] to obtain the spin distribution function [

46]. A diffusion sampling length ratio of 1.25 was used. The resulting diffeomorphic reconstruction output had an isotopic resolution of 2 mm. The accuracy of b-table orientation was examined by comparing fiber orientations with those of a population-averaged template [

45]. Diffusion-weighted images were preprocessed using the EDDY tool implemented via DSI Studio, which corrected for eddy current–induced distortions and motion artifacts. Reverse phase-encoding images were not acquired; therefore, susceptibility distortion correction using TOPUP was not applicable. The tensor metrics were then calculated. The diffusion data were reconstructed in the MNI space using q-space diffeomorphic reconstruction [

23] to obtain the spin distribution function [

46]. A diffusion sampling length ratio of 1.25 was used. The resulting diffeomorphic reconstruction output had an isotopic resolution of 2 mm.

Seeds were randomly placed throughout the ROIs until reaching a cutoff at 50,000,000 seeds. Additionally, two pairwise spherical ROIs were also defined as ending regions. In the case between the Left Superior Occipital Gyrus (L SOG) and the Left Inferior Parietal Lobule (L IPL), for example, the ending regions were placed at (52,74,37) and (51,64,51). An angular threshold of 60 degrees was set as the maximum allowed angular deviation between steps. The step size was randomly selected from 0.5 voxels to 1.5 voxels.

Tracks with lengths shorter than 10 mm or longer than 100 mm were excluded from further analysis. The process continued until mapping each subsystem of the dorsal and ventral visual streams (DVS, VVS, VS), with an exhaustive exploration of all pairwise links in each section denoted in

Table 2. For full reproducibility, the parameter ID used in DSI Studio to configure the settings described above is provided: 0AD7233C9A99193Fba3Fdb2041bC84280F0FA02ec. This ID allows others to load the exact parameters used in our analysis, ensuring that tractography and derived metrics can be replicated using identical configurations. Parameter IDs for each pairwise link are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository accompanying this project.

3. Results

3.1. Cortical Thickness

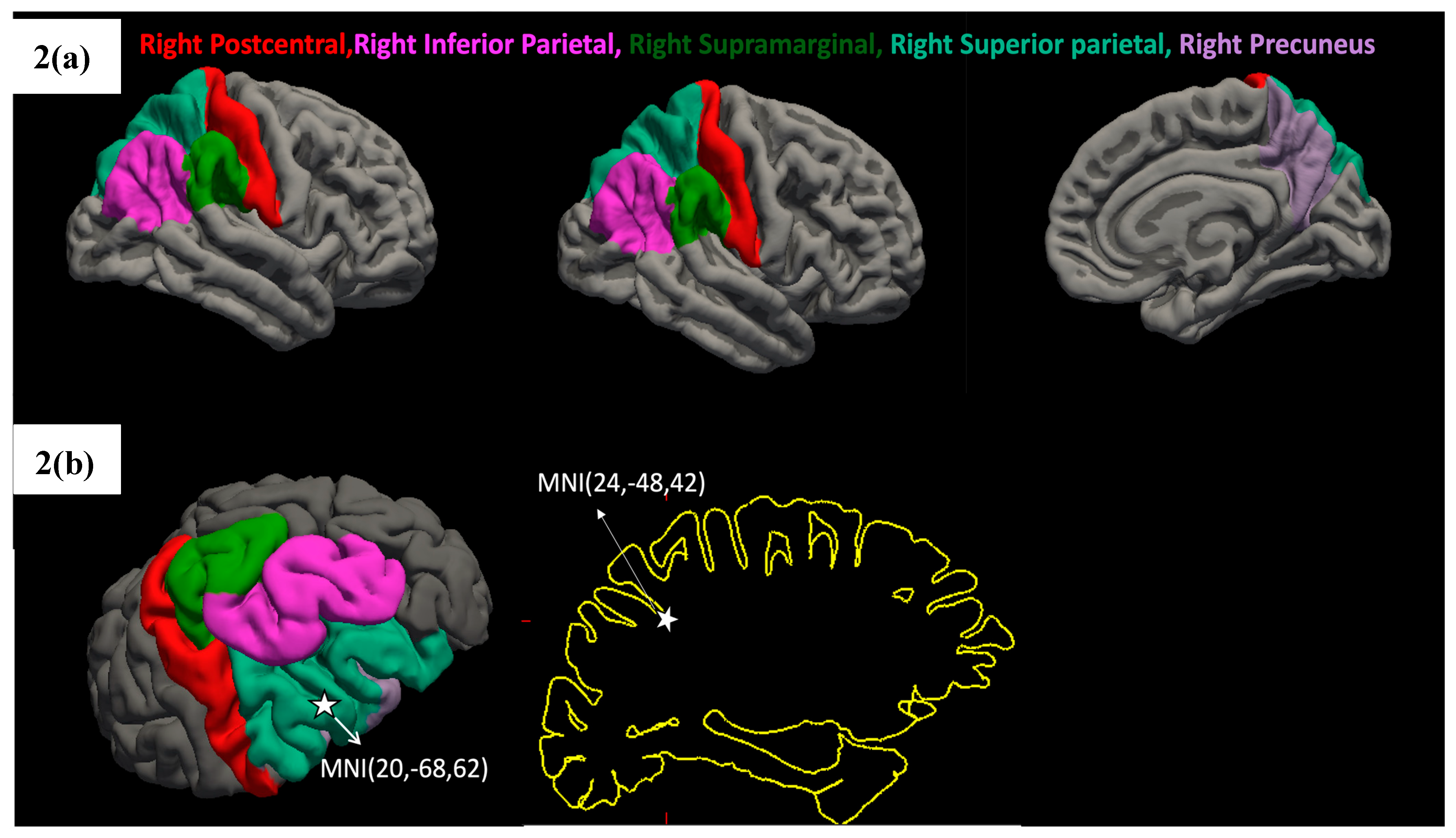

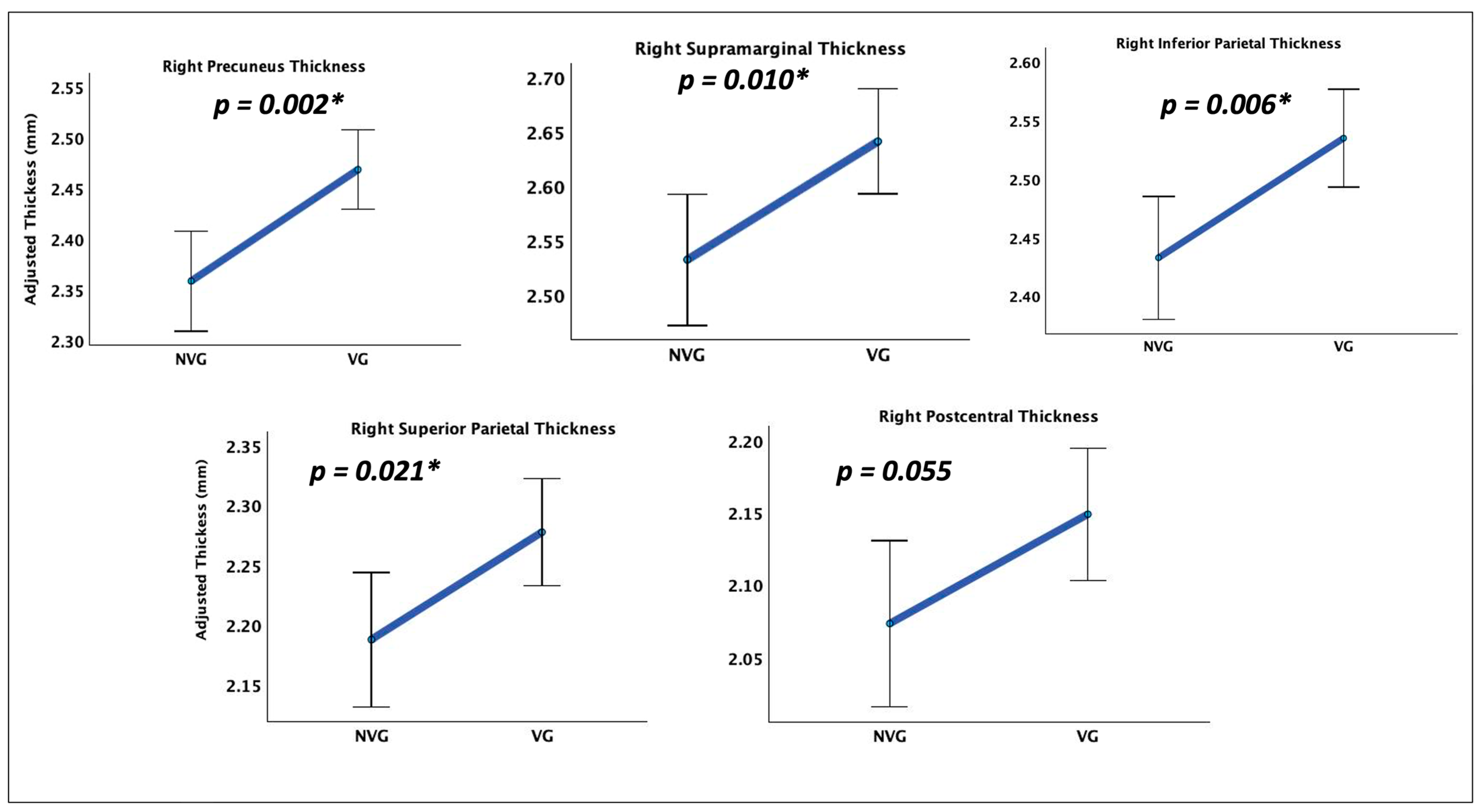

A significant difference in cortical thickness was observed between groups [F(2,41) = 19.828, p = 0.049, ηp² = 0.998]. The most significant regions are shown in

Table 3. The results depict a significant difference in cortical thickness between video game players (VGP) and non-video game players (NVGP), with all reported p-values

Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons across 70 ROIs to control for Type I error. The four regions namely Right inferior parietal, Right precuneus, Right superior parietal, and Right supramarginal show the most significance among the identified as shown in

Figure 1.

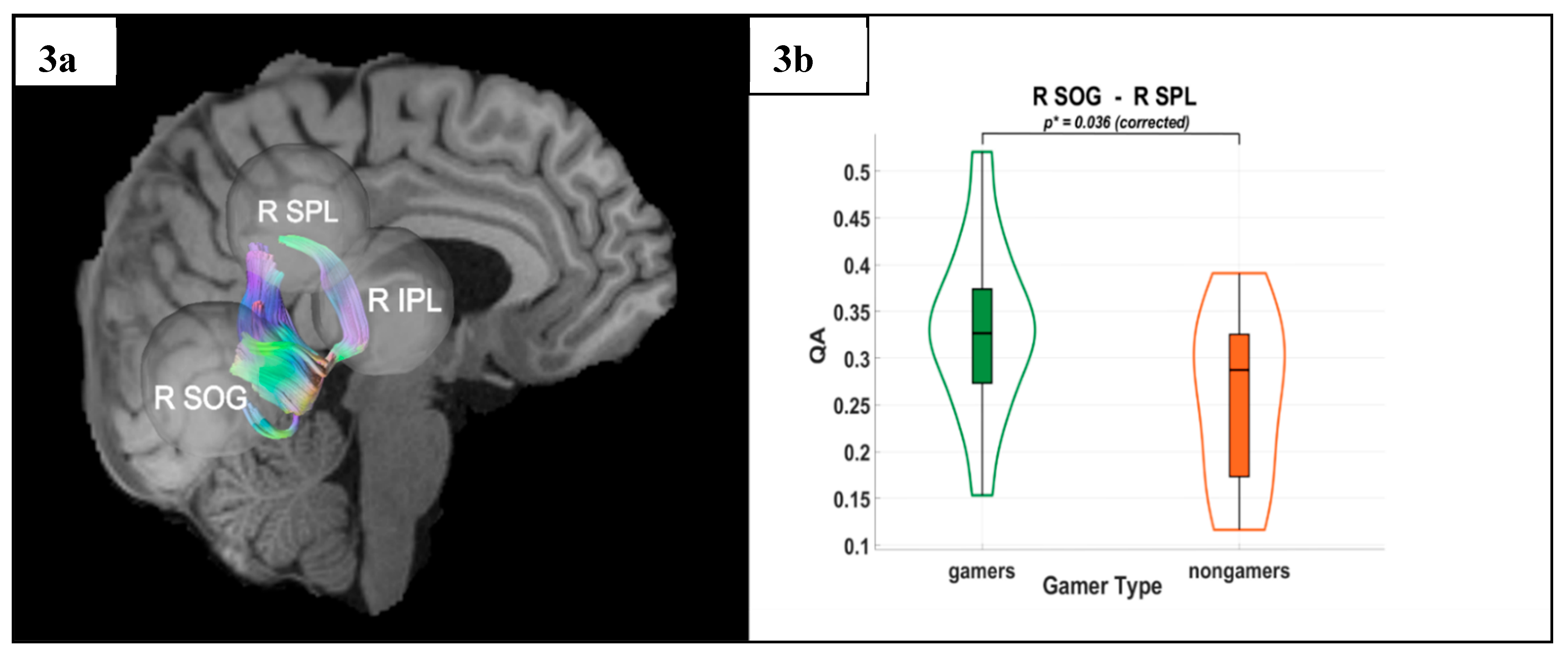

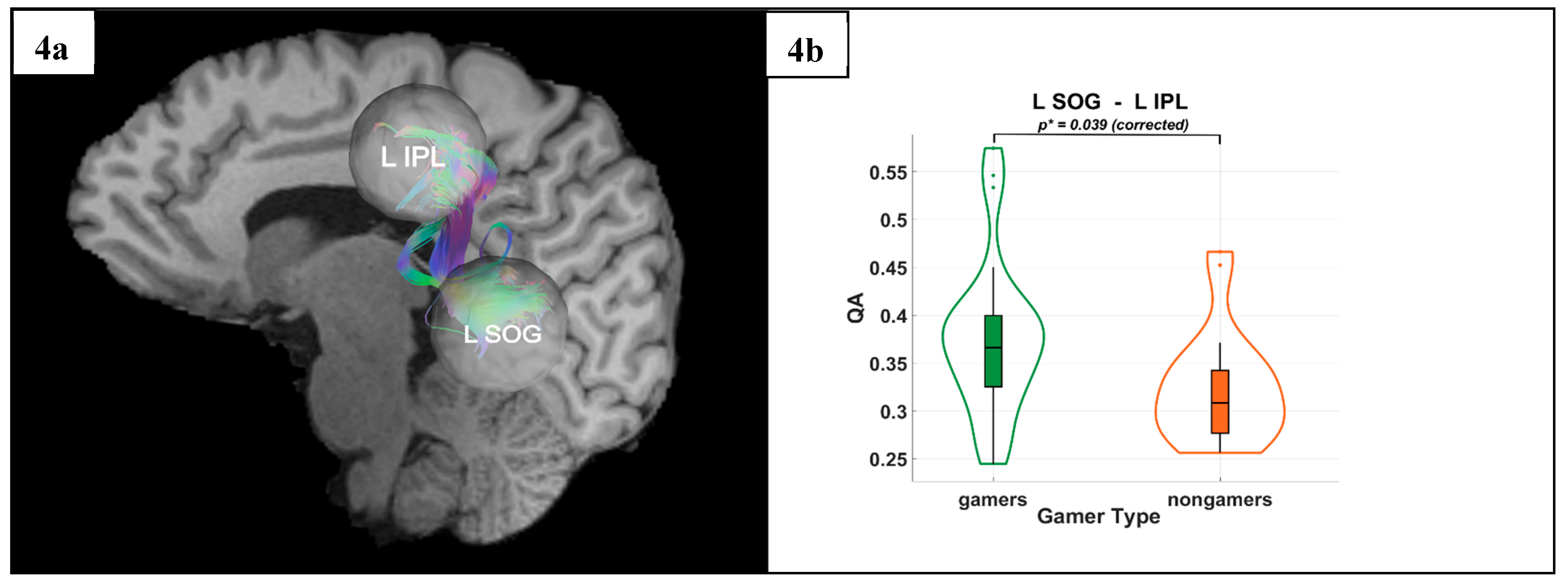

3.2. White Matter Integrity

DTI results revealed significantly higher QA values in VGPs in the dorsal stream. Specifically, gamers exhibited greater QA between the R SOG and the R SPL (p* = 0.036) and between the L SOG and the L IPL (p* = 0.039). These results were Holm-Bonferroni corrected, ensuring rigorous control for multiple comparisons, further supporting improved microstructural integrity in VGPs.

Figure 2.

(

a,

b)

Regions of Significant Grey Matter Thickness Differences Between Video Gamers and Non-Gamers.

Figure 2(a) shows the statistically significant regions, whereas

Figure 2(b) shows the MNI coordinates along the right superior parietal and right inferior parietal areas, which are a part of the dorsal visual processing stream.

Figure 2.

(

a,

b)

Regions of Significant Grey Matter Thickness Differences Between Video Gamers and Non-Gamers.

Figure 2(a) shows the statistically significant regions, whereas

Figure 2(b) shows the MNI coordinates along the right superior parietal and right inferior parietal areas, which are a part of the dorsal visual processing stream.

Figure 3.

(a) Tractography visualization in a representative subject showing white matter connections between the right superior occipital gyrus (R SOG), right superior parietal lobule (R SPL), and right inferior parietal lobule (R IPL). The X-axis is coded for red from right to left, the Y-axis is coded for green from anterior to posterior, and the Z-axis is coded for blue from superior to inferior. (b) Group differences in quantitative anisotropy (QA) for the R SOG–R SPL connection, with significantly higher QA values observed in video game players (VGPs) compared to non-video game players (NVGPs) (p* = 0.036, corrected).

Figure 3.

(a) Tractography visualization in a representative subject showing white matter connections between the right superior occipital gyrus (R SOG), right superior parietal lobule (R SPL), and right inferior parietal lobule (R IPL). The X-axis is coded for red from right to left, the Y-axis is coded for green from anterior to posterior, and the Z-axis is coded for blue from superior to inferior. (b) Group differences in quantitative anisotropy (QA) for the R SOG–R SPL connection, with significantly higher QA values observed in video game players (VGPs) compared to non-video game players (NVGPs) (p* = 0.036, corrected).

Figure 4.

(a) Tractography visualization in a representative subject showing white matter connections between the left superior occipital gyrus (L SOG), and the left inferior parietal lobule (L IPL). The X-axis is coded for red from right to left, the Y-axis is coded for green from anterior to posterior, and the Z-axis is coded for blue from superior to inferior. (b) Group differences between VGPs(gamers) and NVGPs (nongamers) in quantitative anisotropy (QA) for the L SOG–L IPL connection, with significantly higher QA values observed in vieo game players (VGPs) compared to non-video game players (NVGPs) (p* = 0.039, corrected).

Figure 4.

(a) Tractography visualization in a representative subject showing white matter connections between the left superior occipital gyrus (L SOG), and the left inferior parietal lobule (L IPL). The X-axis is coded for red from right to left, the Y-axis is coded for green from anterior to posterior, and the Z-axis is coded for blue from superior to inferior. (b) Group differences between VGPs(gamers) and NVGPs (nongamers) in quantitative anisotropy (QA) for the L SOG–L IPL connection, with significantly higher QA values observed in vieo game players (VGPs) compared to non-video game players (NVGPs) (p* = 0.039, corrected).

4. Discussion

Our findings provide evidence that long-term action video game playing is associated with structural adaptations in key visuospatial processing and attention control networks in the right parietal cortex. VGPs exhibited significantly greater cortical thickness in the right inferior parietal lobule (IPL), right superior parietal lobule (SPL), right precuneus, and right supramarginal gyrus which are regions central to spatial attention, decision-making, and sensorimotor integration. [

47,

48,

49,

50] Additionally, white matter connectivity analyses using Q-space tractography revealed enhanced quantitative anisotropy (QA) in two critical pathways: the right superior occipital gyrus (SOG) to the right SPL, and the left SOG to the left IPL. These results suggest that gaming strengthens both local cortical structure and large-scale connectivity, facilitating possibly more efficient integration of visuospatial and motor information.

The right superior parietal lobule (SPL), a hub for visuomotor coordination, showed increased cortical thickness in VGPs, aligning with previous research demonstrating gaming-induced neuroplasticity in spatial attention networks and parietal area. The SPL is known to integrate visual, proprioceptive, and motor information, allowing for rapid decision-making and goal-directed actions both of which are highly engaged during gaming. [

51] Increased cortical thickness in this region likely reflects enhanced neural efficiency and synaptic reinforcement from repeated engagement in high-speed visuospatial tasks. Similarly, the inferior parietal lobule (IPL), which plays a key role in attentional control, sensorimotor integration, and action planning, also exhibited significant cortical thickening. Prior research has demonstrated that the IPL is critical for dynamically reallocating attention, particularly in unpredictable environments a cognitive demand that is heightened in fast-paced gaming scenarios.

These structural enhancements suggest that VGPs may develop more efficient attentional networks, allowing for faster responses to visual stimuli and improved task-switching abilities. The precuneus, which exhibited significant cortical thickening, is involved in mental imagery, spatial reasoning, and self-referential processing. [

48,

52] Increased cortical thickness in this region may reflect enhanced spatial navigation abilities and strategic planning, which are fundamental components of action video gameplay. Studies have shown that expert gamers exhibit greater activation of the precuneus during spatial tasks, supporting the idea that gaming strengthens this region's role in complex visuospatial processing. The right-lateralised parietal thickening detected here dovetails with that behavioural profile, suggesting a plausible anatomical substrate for far-transfer gains. Longitudinal designs that pair structural imaging with rigorous cognitive batteries (pre-, mid- and post-training) will be essential to establish temporal precedence and dose–response relations. Older adults and patients recovering from stroke or traumatic brain injury often exhibit dorsal-stream deficits that impair navigation and visuomotor control. Pilot trials show that game-based interventions—especially when delivered in virtual or augmented reality—can boost adherence and enhance rehabilitation outcomes. [

53,

54]

Our findings suggest that video games particularly action games could be leveraged as cognitive training tools for individuals with visuospatial processing and attentional deficits. Additionally, not all video games are likely to produce the same effects. Action games, which require rapid visuospatial processing and sensorimotor coordination, may drive different neural adaptations compared to puzzle or strategy games, which likely engage executive functions and problem-solving networks. Future research should explore how different genres and subgenres influence structural connectivity, helping to refine game-based cognitive training paradigms.

Finally, while our study focused on cortical thickness and white matter integrity, future research should investigate how these structural adaptations interact with functional connectivity and real-time neural dynamics. Multimodal approaches, including resting-state and task-based fMRI, could clarify how changes in structure translate to behavioral advantages. Additionally, EEG studies have shown that video game playing induces distinct attentional and arousal-related neural signatures, suggesting that future work could explore how structural changes correspond to real-time cognitive processing efficiency. [

30]

5. Limitations

Several caveats should temper interpretation of our findings. First, we restricted our neuroplasticity assessment to structural indicators—cortical thickness and quantitative anisotropy—without complementary functional (fMRI, EEG) or metabolic measures. As a result, we cannot determine whether the observed macro- and micro-structural differences translate into altered network dynamics or behavioral performance. Second, the cross-sectional design and modest sample size, although adequately powered for medium effects, limit causal inference and generalizability. Finally, the predominance of male FPS players within the VGP cohort may constrain relevance to other genres and demographic profiles. Future longitudinal, multimodal studies that integrate structural, functional, and cognitive readouts across diverse gamer populations are needed to clarify mechanism and scope.

6. Conclusions

Our results provide strong evidence that long-term action video game playing is associated with structural neuroplasticity in visuospatial and sensorimotor networks, particularly in the dorsal stream and right parietal cortex. These findings suggest that gaming fosters experience-dependent cortical and white matter adaptations, enhancing the efficiency of visuospatial processing and attentional control. While further research incorporating video game training and brain imaging is needed to elucidate the underlying neural mechanisms and long-term effects, this study highlights the potential of gaming as a model for exploring neuroplasticity and optimizing cognitive training interventions.

Author Contributions

Chandrama Mukherjee† and Kyle Cahill† – made equal contributions: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, review & editing. Mukesh Dhamala: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, review & editing.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of the study as well as the custom analysis scripts can be found in OSF (link will be public after publication).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by two internal grant awards of Brains and Behavior Program & the Center for Advanced Brain Imaging to M.D.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- Bereczk, A.; Szilagyine Fulop, E.; Hodine Hernadi, B. Web 3 Gaming: A Sectoral Analysis and Forecast to 2033. in Proceedings of the Central and Eastern European eDem and eGov Days 2024, 2024, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Coronel-Oliveros, C.; et al. Gaming expertise induces meso-scale brain plasticity and efficiency mechanisms as revealed by whole-brain modeling. NeuroImage 2024, 293, 120633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Cheng, C. The Benefits of Video Games on Brain Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelier, D.; Achtman, R.L.; Mani, M.; Föcker, J. Neural bases of selective attention in action video game players. Vision Research 2012, 61, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Gallinat, J. Amount of lifetime video gaming is positively associated with entorhinal, hippocampal and occipital volume. Mol Psychiatry 2014, 19, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Gleich, T.; Lorenz, R.C.; Lindenberger, U.; Gallinat, J. Playing Super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: Gray matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 19, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.J.; Cregan, S.C.; Joyce, J.M.; Kowal, M.; Toth, A.J. Comparing the cognitive performance of action video game players and age-matched controls following a cognitively fatiguing task: A stage 2 registered report. British Journal of Psychology 2024, 115, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.; Dhamala, M. Enhanced Dorsal Attention Network to Salience Network Interaction in Video Gamers During Sensorimotor Decision-Making Tasks. Brain Connect 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.; Dhamala, M. Video game players have improved decision-making abilities and enhanced brain activities. Neuroimage: Reports 2022, 2, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.; Bowden, V.K.; Visser, T. Do action video games make safer drivers? The effects of video game experience on simulated driving performance. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2023, 97, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; et al. Positive association of video game playing with left frontal cortical thickness in adolescents. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, P.; et al. Association between real-time strategy video game learning outcomes and pre-training brain white matter structure: Preliminary study. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 20741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilliant, T.D.; Nouchi, R.; Kawashima, R. Does Video Gaming Have Impacts on the Brain: Evidence from a Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2019, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Turel, O.; Wei, L.; Bechara, A. Structural brain differences associated with extensive massively-multiplayer video gaming. Brain Imaging Behav 2021, 15, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Jan, R.A.; Alsaedi, S.L. Symptoms, Mechanisms, and Treatments of Video Game Addiction. Cureus 2023, 15, e36957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, M.; Anderson, M.; Åkerstedt, T.; Lindblad, F. The effect of violent and nonviolent video games on heart rate variability, sleep, and emotions in adolescents with different violent gaming habits. Psychosom Med 2013, 75, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Gallinat, J.; Mascherek, A. Effects of computer gaming on cognition, brain structure, and function: A critical reflection on existing literature

. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2019, 21, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeck, C.; Gazes, Y.; Razlighi, Q.; Stern, Y. Cortical thickness and its associations with age, total cognition and education across the adult lifespan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, A.; Voss, M.; Lee, H.; Vo, L.; Kramer, A. Parietal plasticity after training with a complex video game is associated with individual differences in improvements in an untrained working memory task. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchenhoff, S.; et al. Visual processing speed is linked to functional connectivity between right frontoparietal and visual networks. Eur J Neurosci 2021, 53, 3362–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filley, C.M.; Fields, R.D. White matter and cognition: Making the connection. J Neurophysiol 2016, 116, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, F.C.; Verstynen, T.D.; Wang, Y.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Tseng, W.Y. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, F.C.; Wedeen, V.J.; Tseng, W.Y. Generalized q-sampling imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2010, 29, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gallivan, J.P.; Chapman, C.S.; Wolpert, D.M.; Flanagan, J.R. Decision-making in sensorimotor control. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2018, 19, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; He, C.; Han, Z.; Bi, Y. Domain-specific functional coupling between dorsal and ventral systems during action perception. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 21200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. Action video game modifies visual selective attention. Nature 2003, 423, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. Action-video-game experience alters the spatial resolution of vision. Psychological science 2007, 18, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. Action video game training for cognitive enhancement. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2015, 4, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-L.; et al. Action video games influence on audiovisual integration in visual selective attention condition. in International Conference on Medicine Sciences and Bioengineering, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China (2018).

- Stewart, H.J.; Martinez, J.L.; Perdew, A.; Green, C.S.; Moore, D.R. Auditory cognition and perception of action video game players. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 14410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. The Ishihara test for color blindness. American Journal of Physiological Optics 1924.

- Dale, A.M.; Fischl, B.; Sereno, M.I. Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 1999, 9, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B.; Sereno, M.I.; Tootell, R.B.; Dale, A.M. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Human brain mapping 1999, 8, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ségonne, F.; Grimson, E.; Fischl, B. A genetic algorithm for the topology correction of cortical surfaces. in Biennial International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging 393-405 (Springer, 2005).

- Desikan, R.S.; et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006, 31, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B.; et al. Whole brain segmentation: Automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002, 33, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B.; et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cerebral cortex 2004, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iscan, Z.; et al. Test–retest reliability of freesurfer measurements within and between sites: Effects of visual approval process. Human brain mapping 2015, 36, 3472–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, S.; et al. Dorsal and Ventral Stream Function in Children With Developmental Coordination Disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 2021, 15, 703217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodale, M.A.; Milner, A.D.; Jakobson, L.S.; Carey, D.P. A neurological dissociation between perceiving objects and grasping them. Nature 1991, 349, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.-w.; et al. Effects of visual attention modulation on dynamic effective connectivity and visual fixation during own-face viewing in body dysmorphic disorder. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian journal of statistics 1979, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone, M.; Agata, Z.; Cozzucoli, P.C.; Alibrandi, A. Bonferroni-Holm and permutation tests to compare health data: Methodological and applicative issues. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, F.C.; Panesar, S.; Yoshino, M.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Vettel, J.M.; Verstynen, T. Population-averaged atlas of the macroscale human structural connectome and its network topology. Neuroimage 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, F.C.; Tseng, W.Y. NTU-90: A high angular resolution brain atlas constructed by q-space diffeomorphic reconstruction. Neuroimage 2011, 58, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numssen, O.; Bzdok, D.; Hartwigsen, G. Functional specialization within the inferior parietal lobes across cognitive domains. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blihar, D.; Delgado, E.; Buryak, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Waechter, R. A systematic review of the neuroanatomy of dissociative identity disorder. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2020, 4, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. Chapter 1 - The neuroscience of emotional disorders. in Handbook of Clinical Neurology (ed. K.M. Heilman & S.E. Nadeau) 1-26 (Elsevier, 2021).

- Moen, K.C.; et al. Strengthening spatial reasoning: Elucidating the attentional and neural mechanisms associated with mental rotation skill development. Cogn Res Princ Implic 2020, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.M.; Goodbody, S.J.; Husain, M. Maintaining internal representations: The role of the human superior parietal lobe. Nat Neurosci 1998, 1, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, B.; Ross, T.J.; Stein, E.A. Neuroanatomical dissociation between bottom–up and top–down processes of visuospatial selective attention. NeuroImage 2006, 32, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Fields, R.D.; Johansen-Berg, H. Plasticity in gray and white: Neuroimaging changes in brain structure during learning. Nature neuroscience 2012, 15, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, R.D. A new mechanism of nervous system plasticity: Activity-dependent myelination. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2015, 16, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).