Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

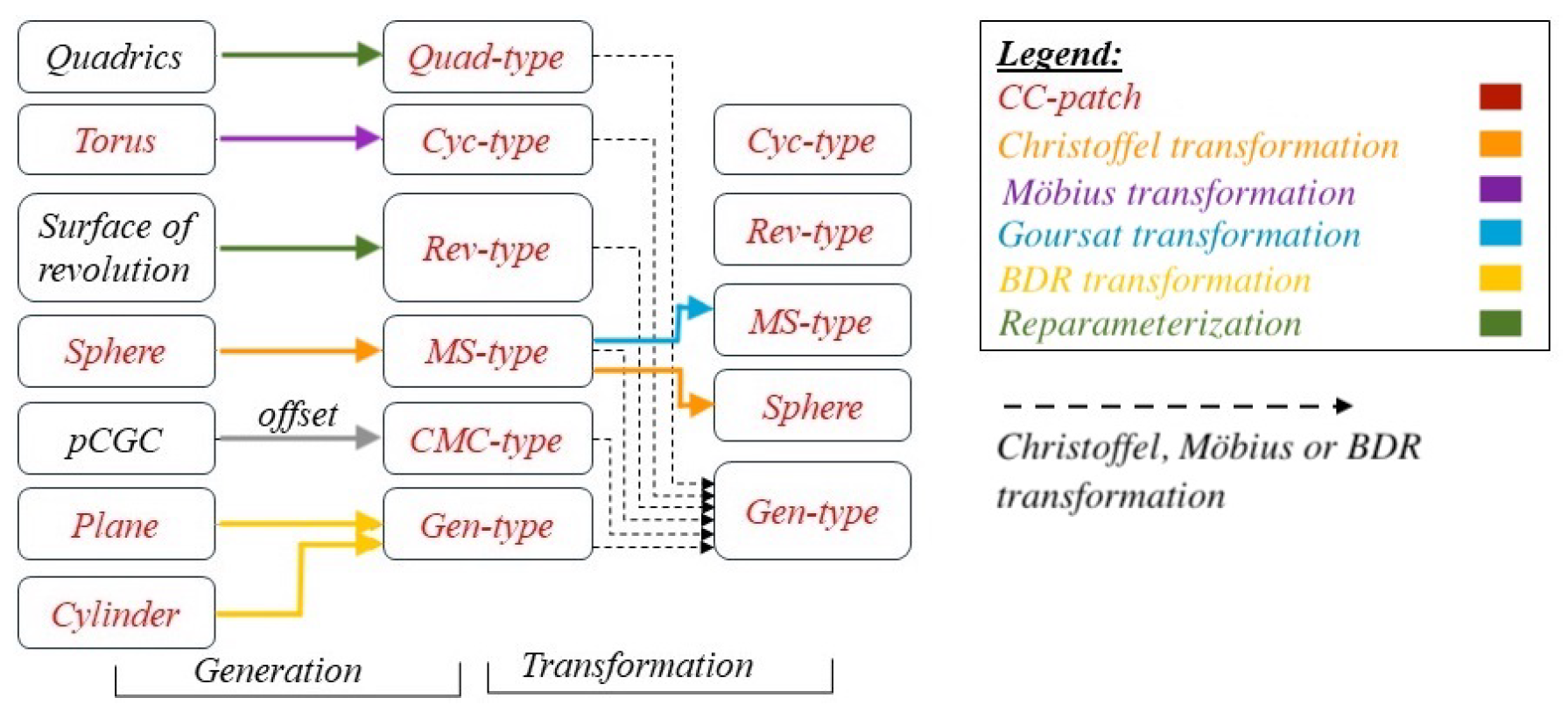

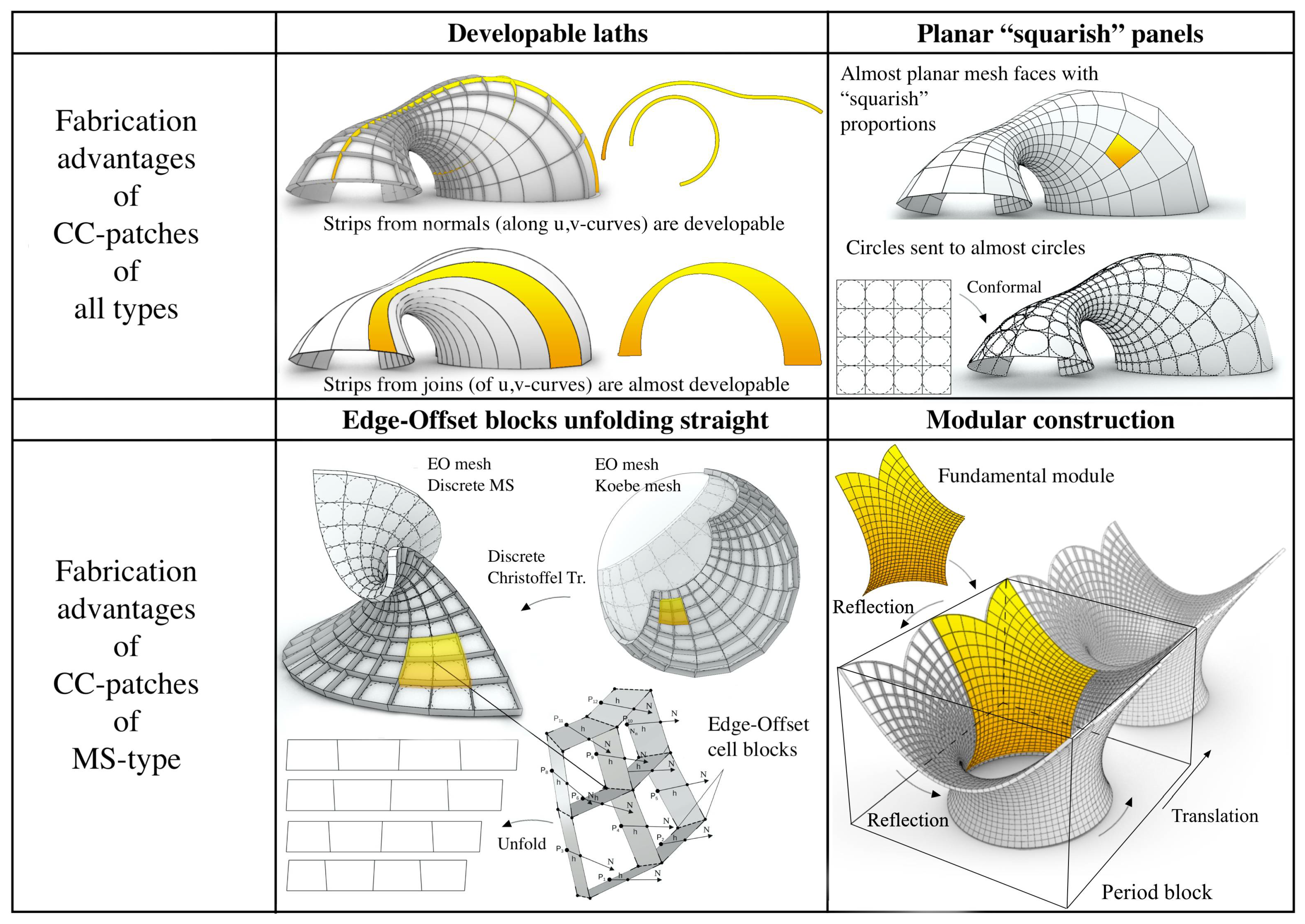

2. Geometry

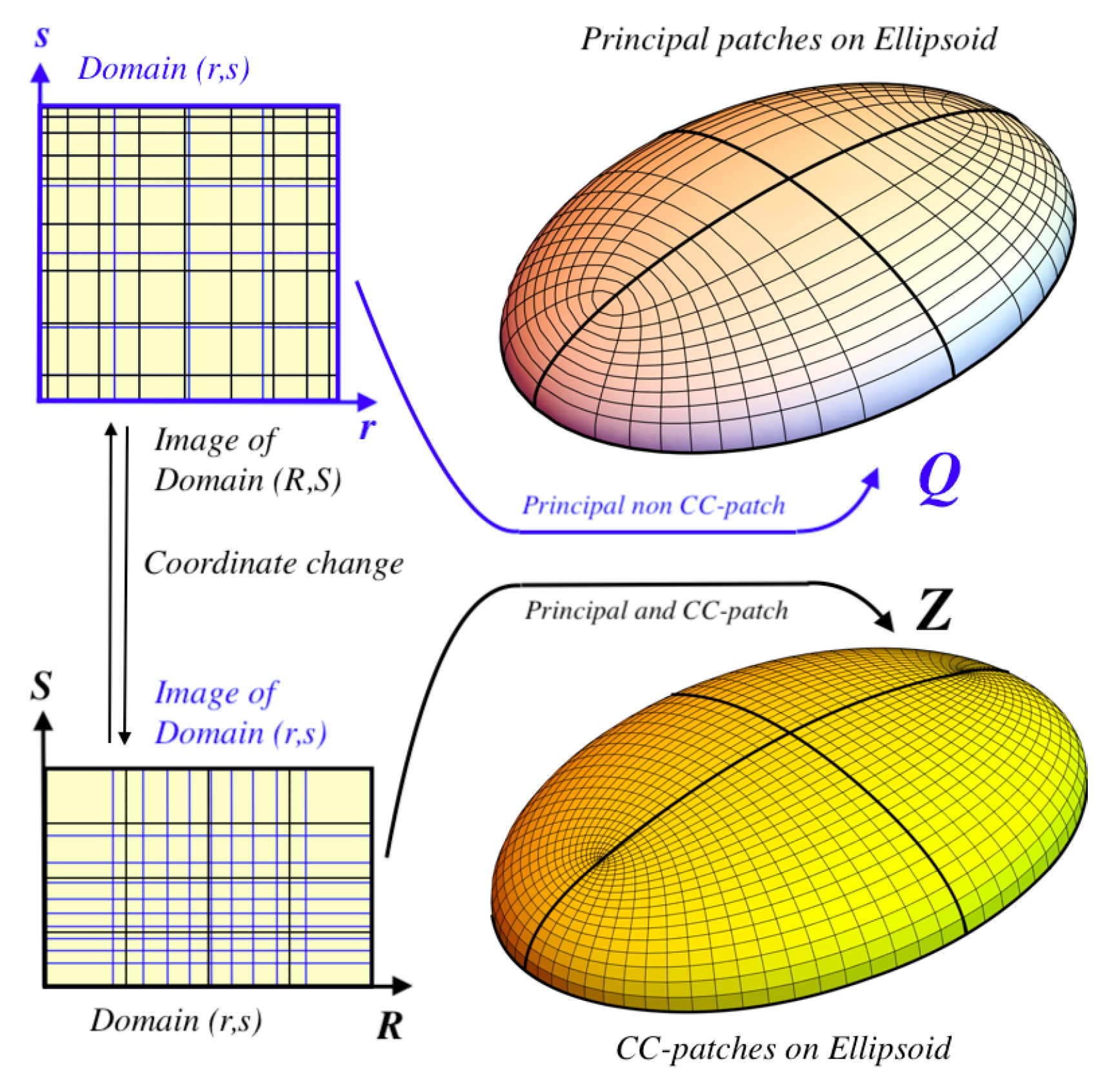

2.1. Isothermic Patches (CC-Patch)

2.2. Quad-Type

2.2.1. Quad-Type from Reparameterization

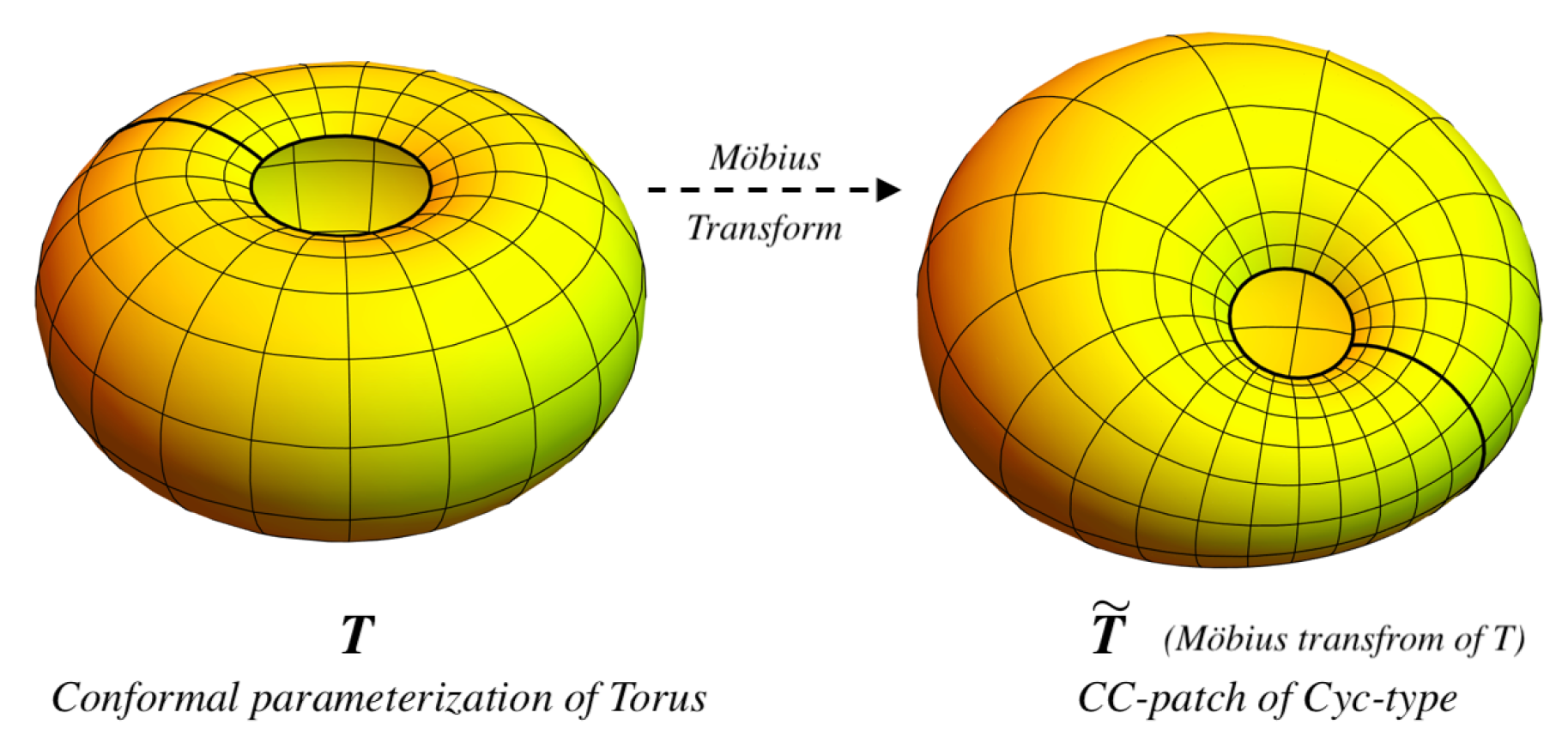

2.3. Cyc-Type

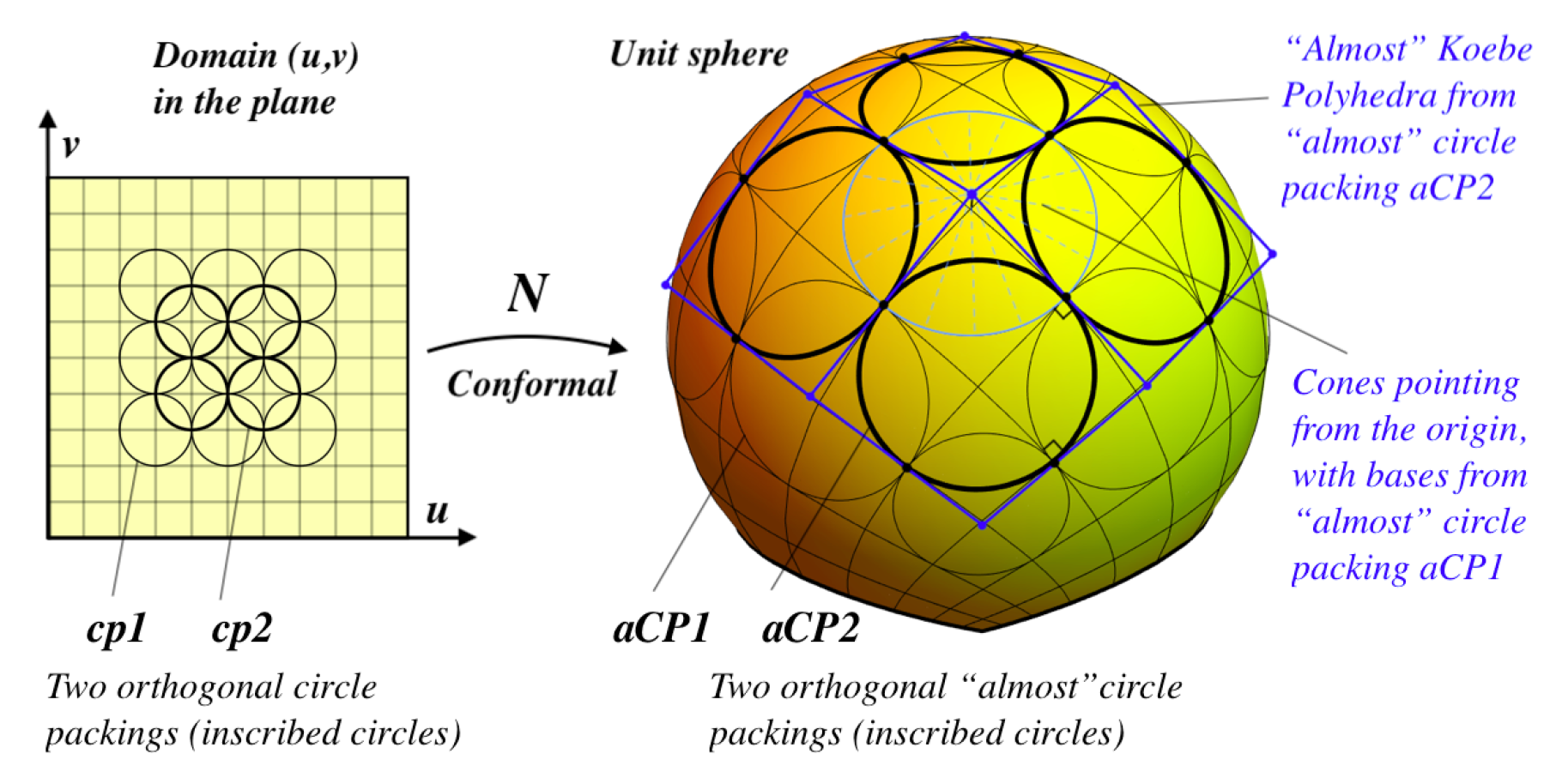

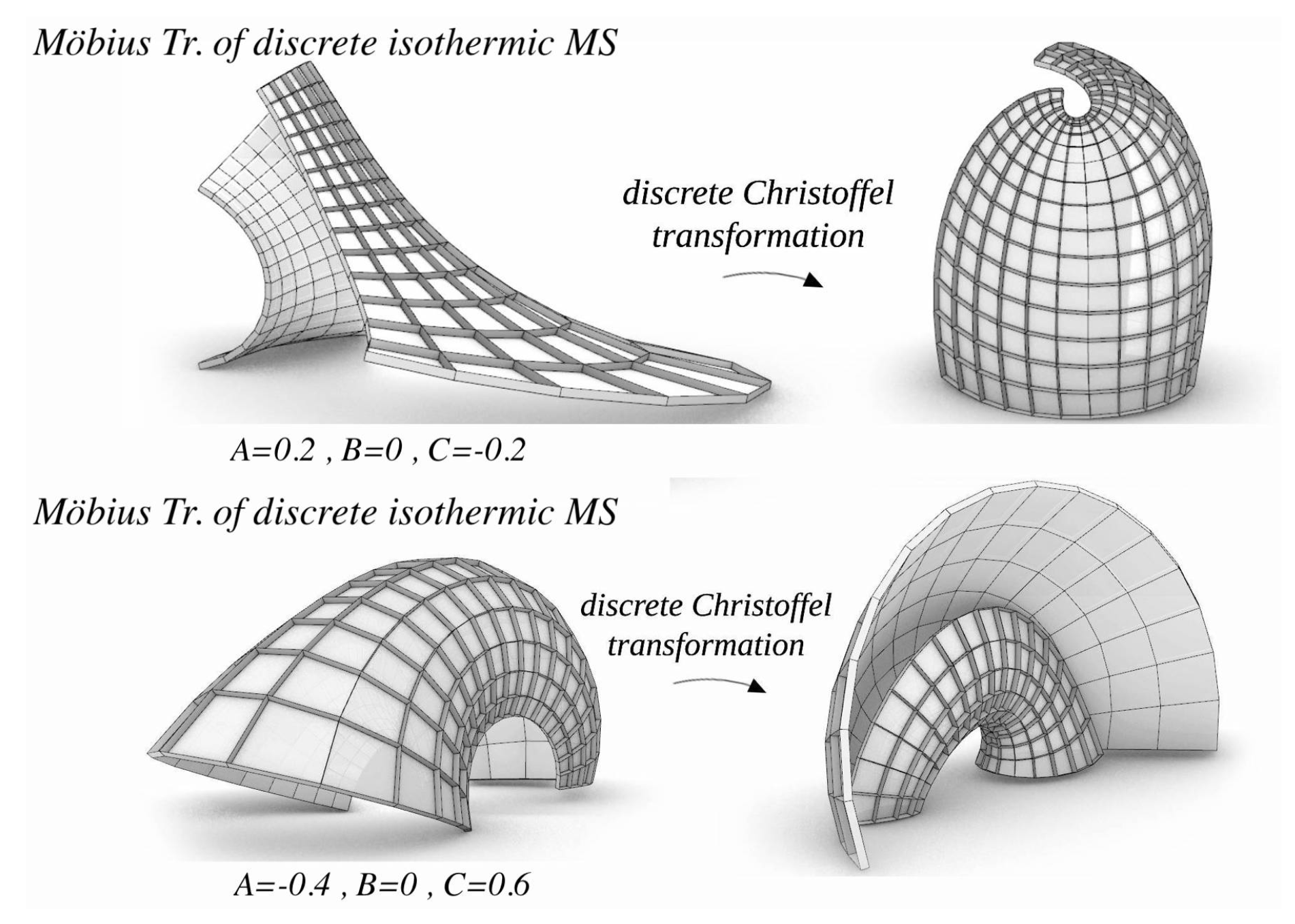

2.3.1. Cyc-Type from Möbius Transform

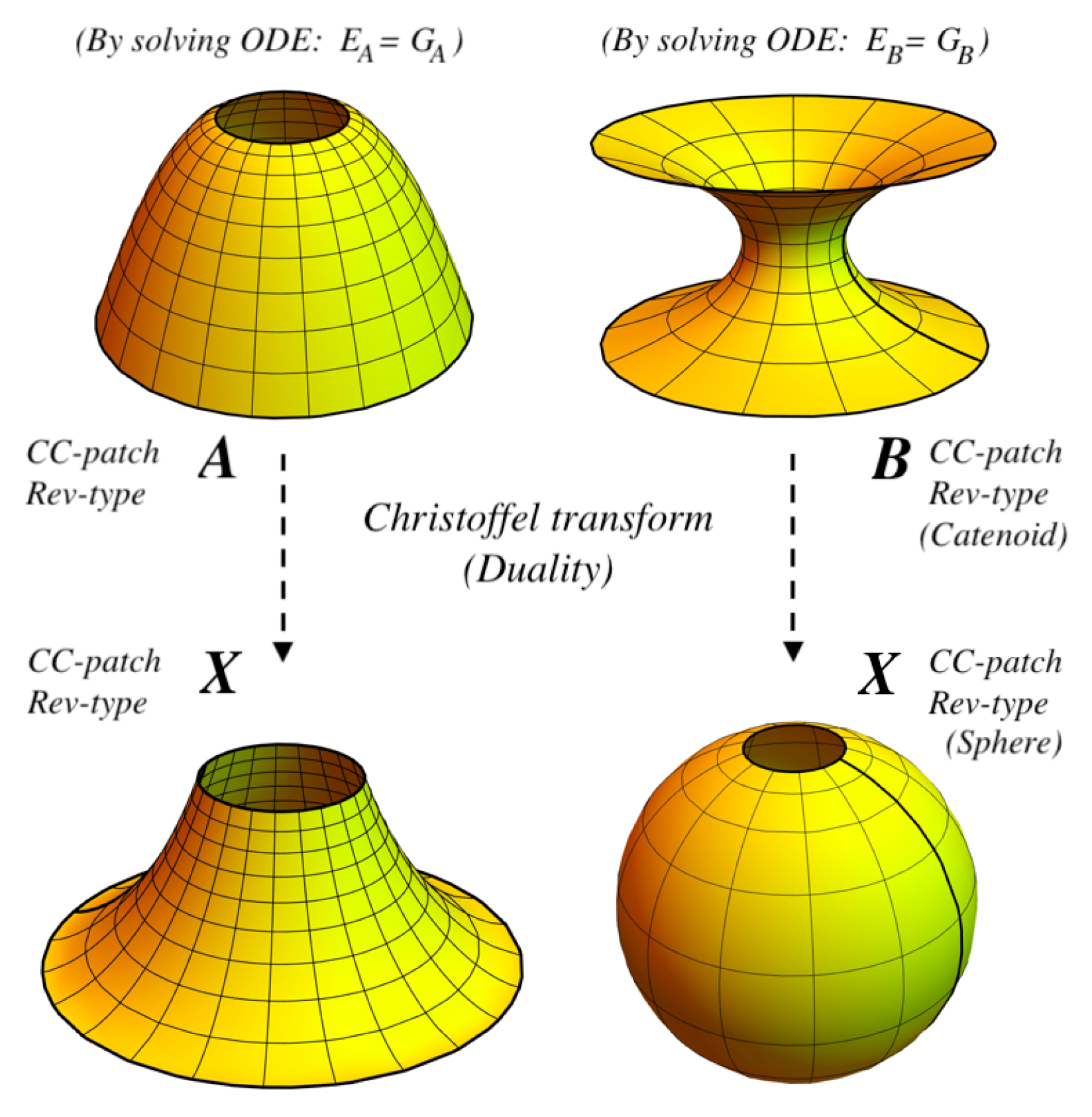

2.4. Rev-Type

2.4.1. Rev-type from Reparameterization

2.4.2. Rev-Type from Christoffel Transform

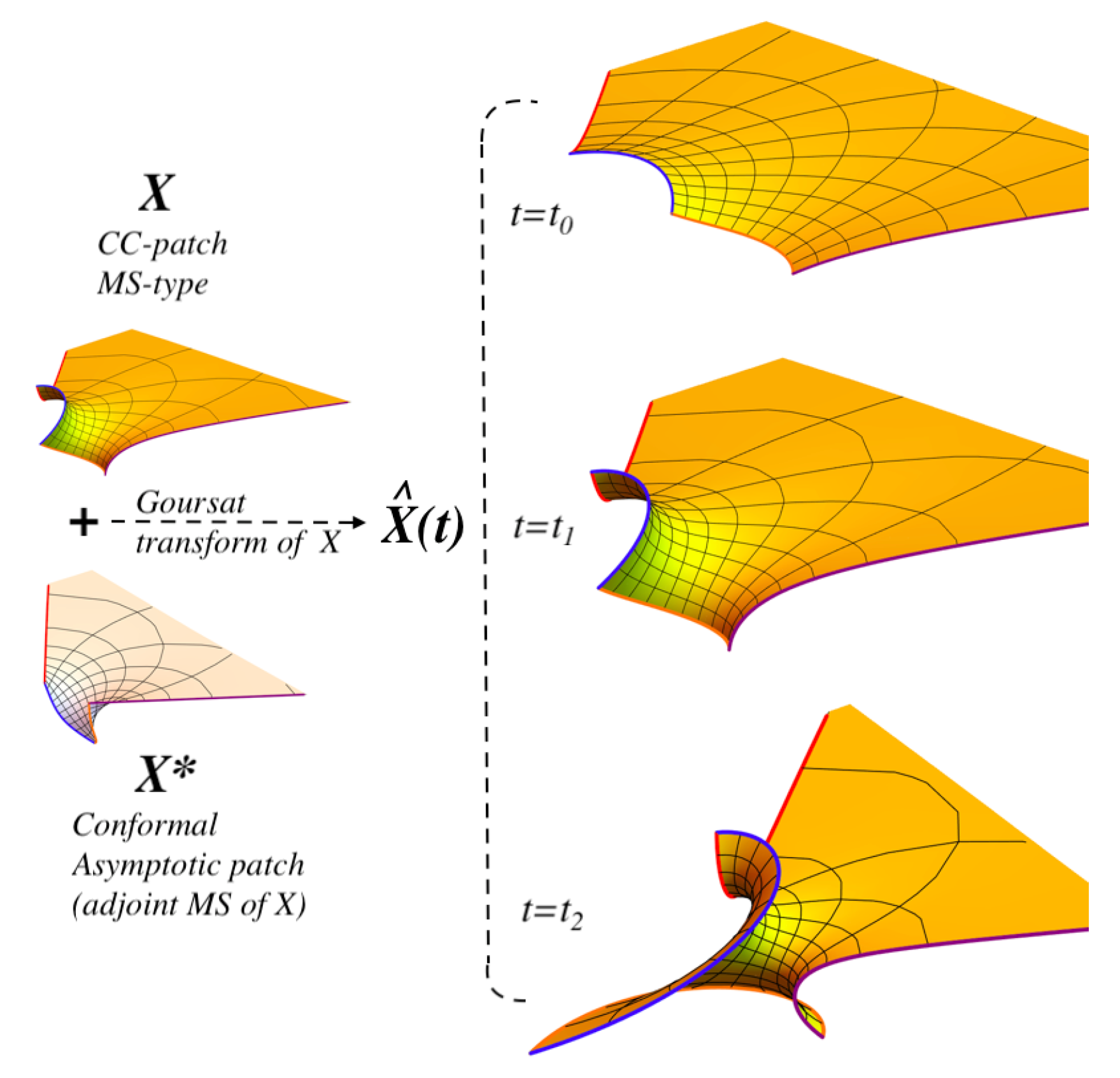

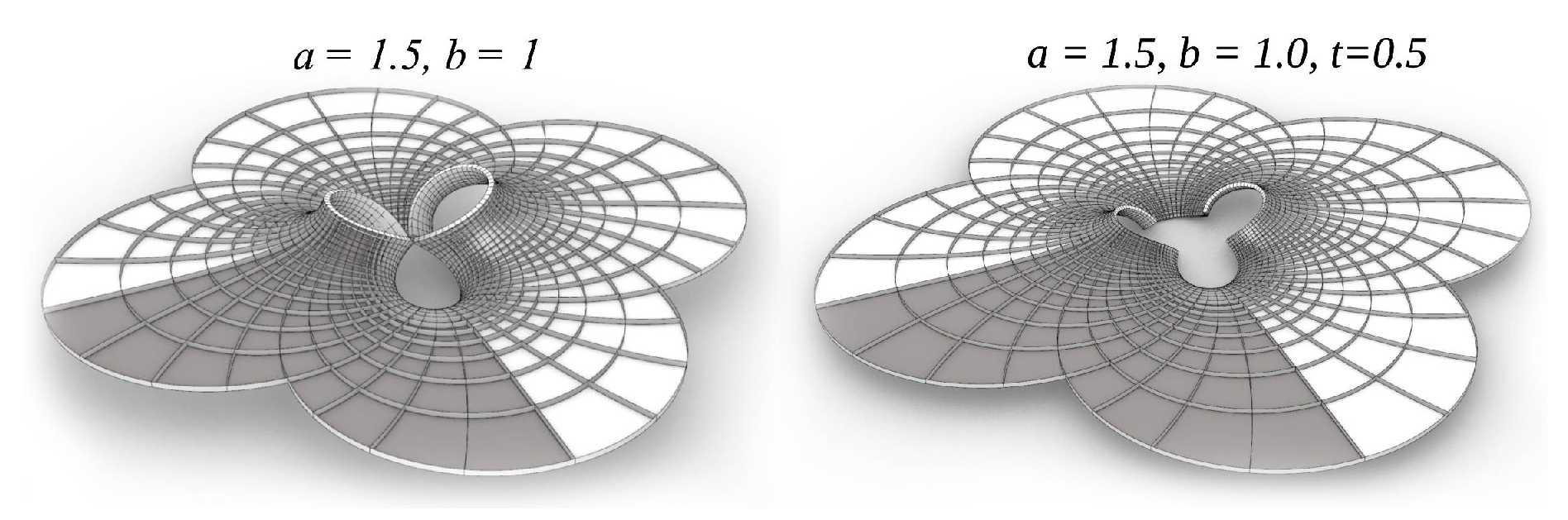

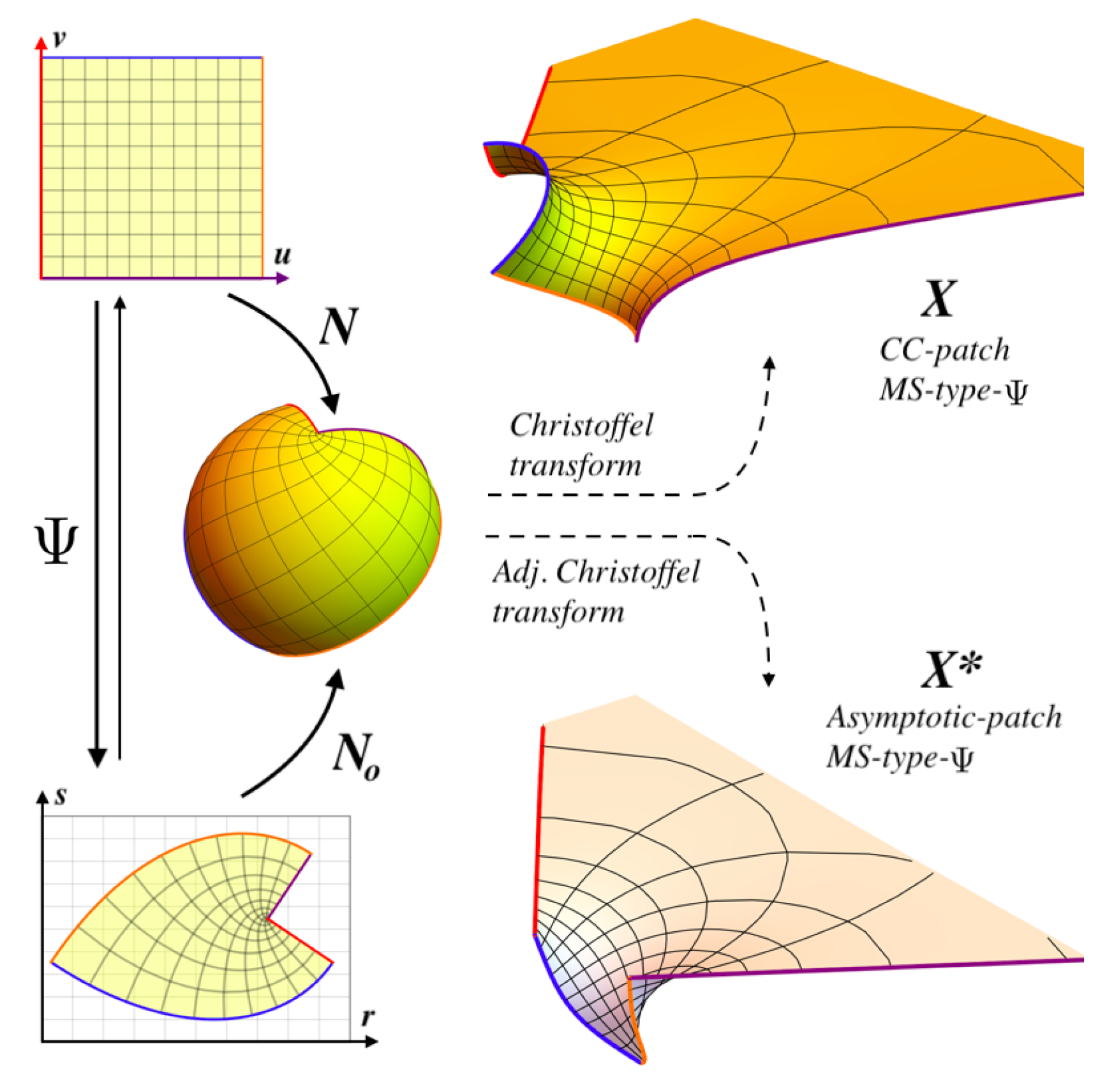

2.5. MS-Type

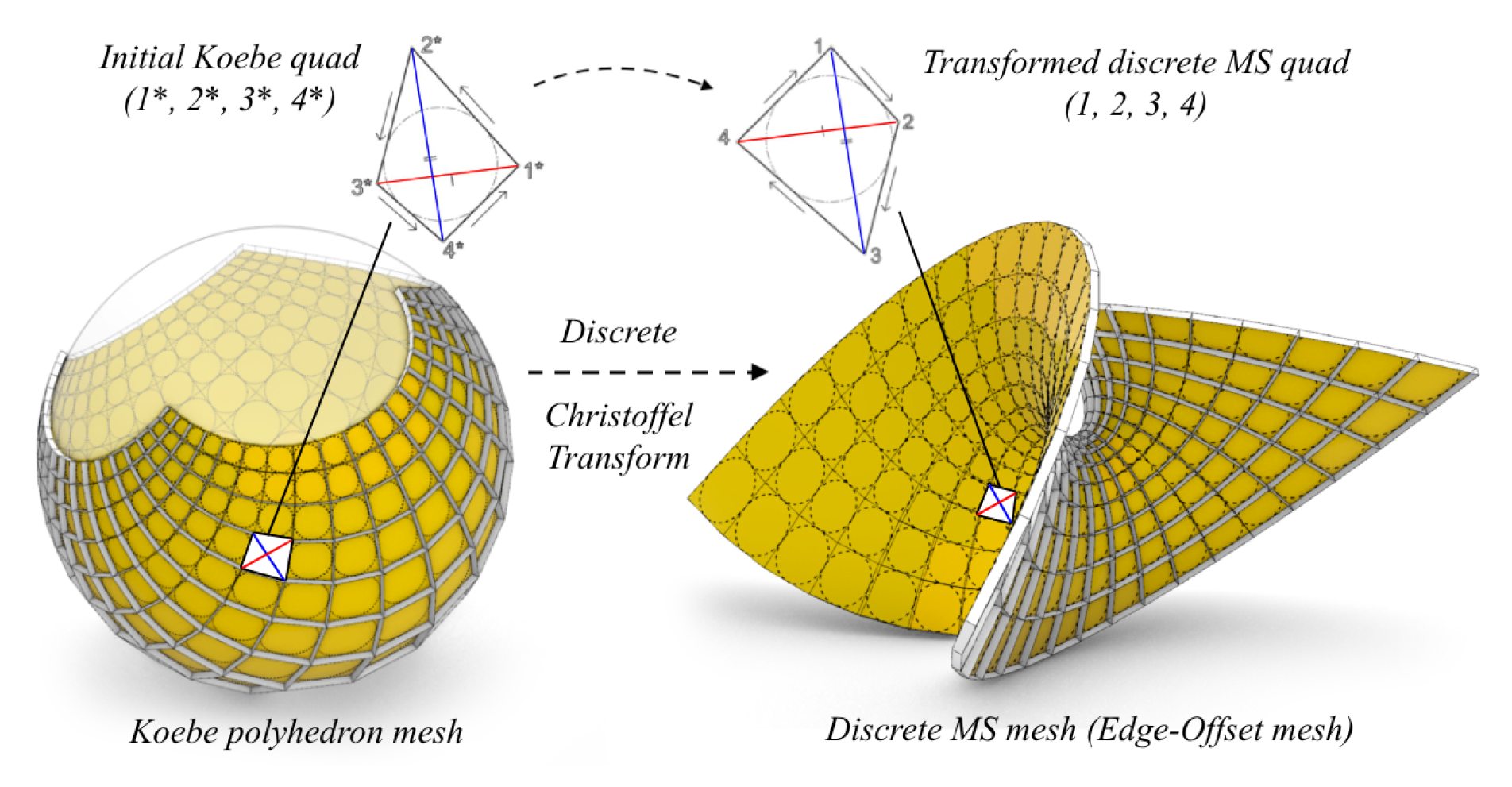

2.5.1. MS-Type from Christoffel Transform

2.5.2. MS-Type from Goursat Transform

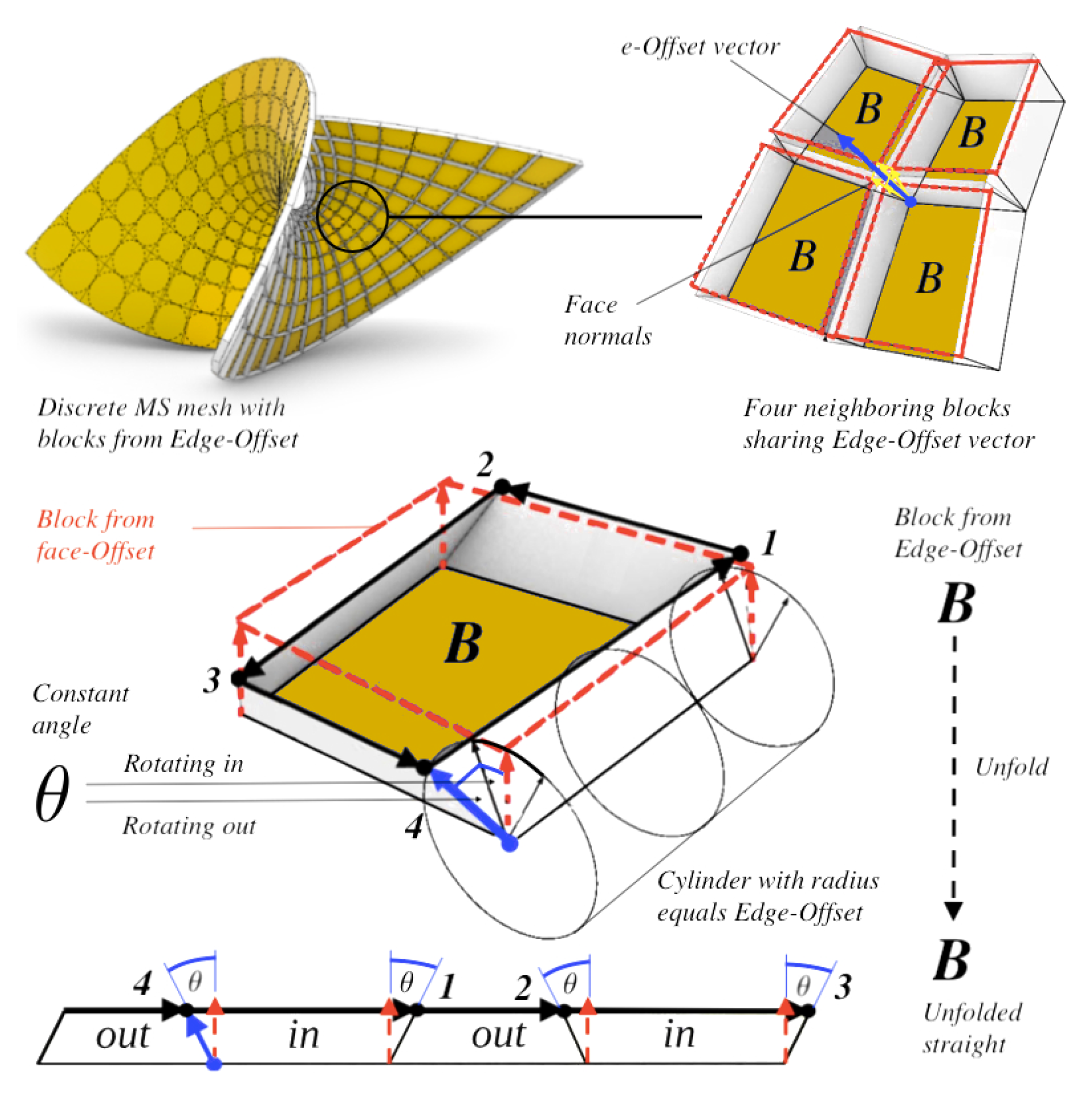

2.5.3. MS-Type Special Properties

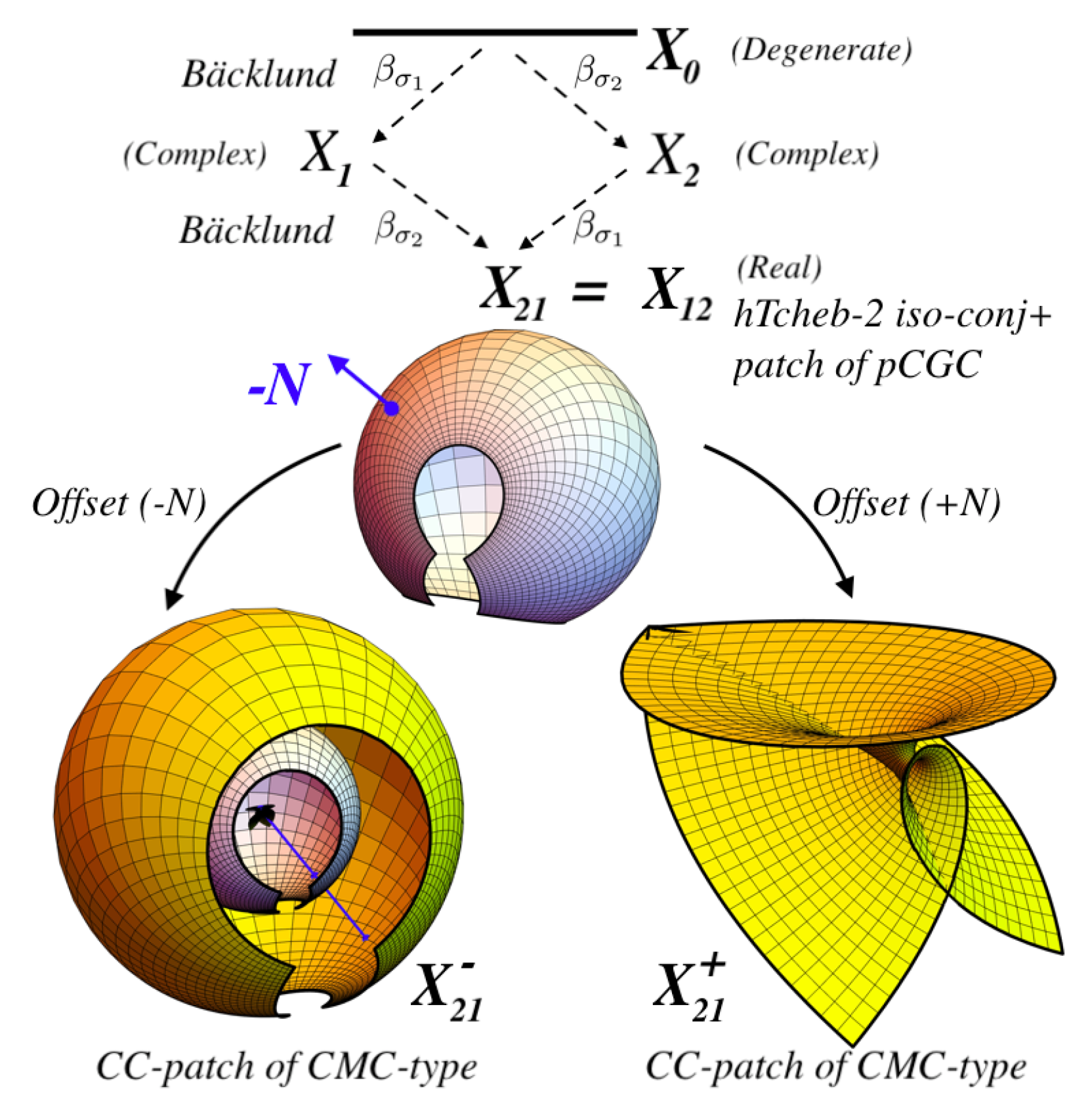

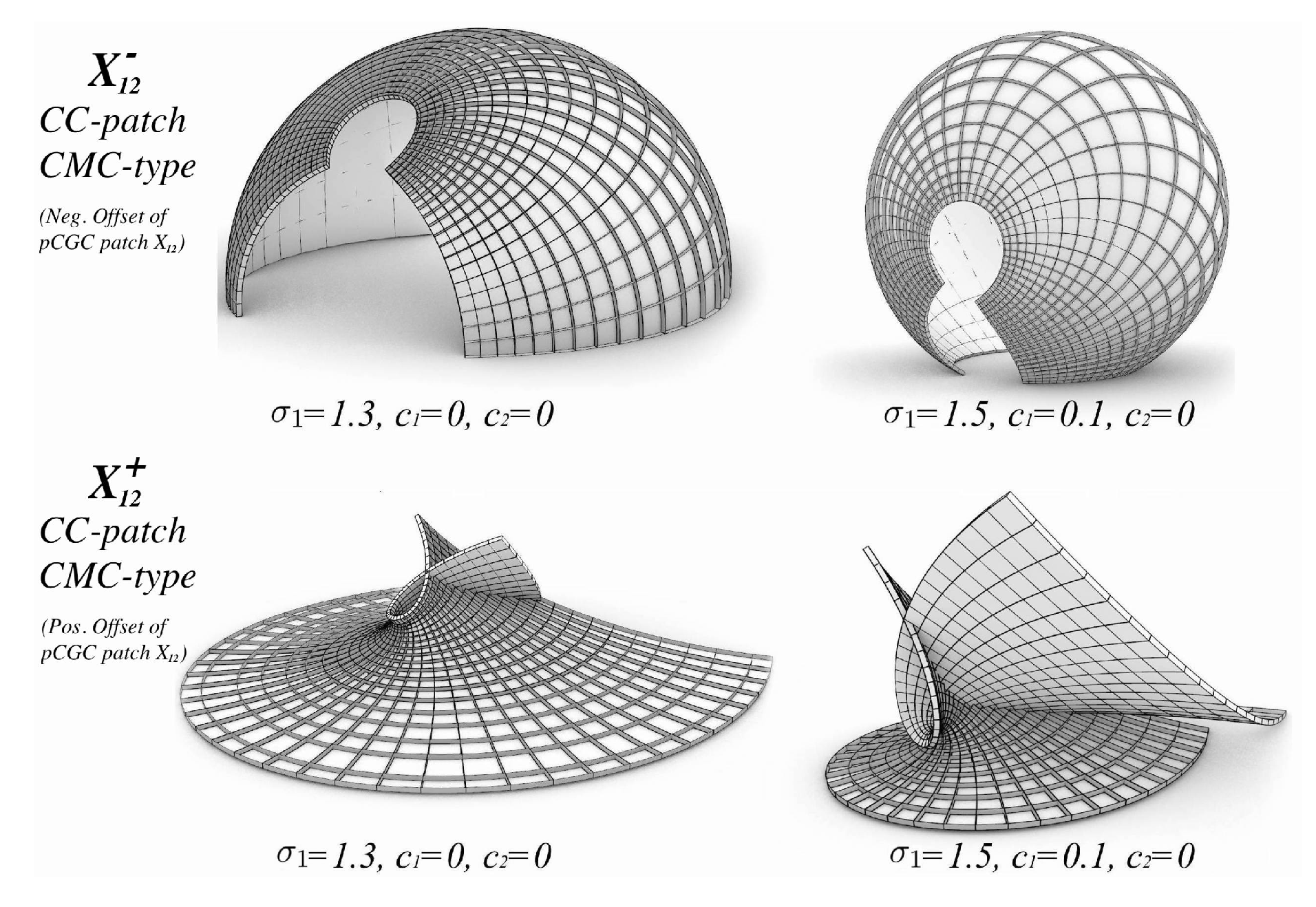

2.6. CMC-Type

2.6.1. Connection pCGC - CMC Patches

2.6.2. CMC-Type from Bäcklund tr. of pCGC

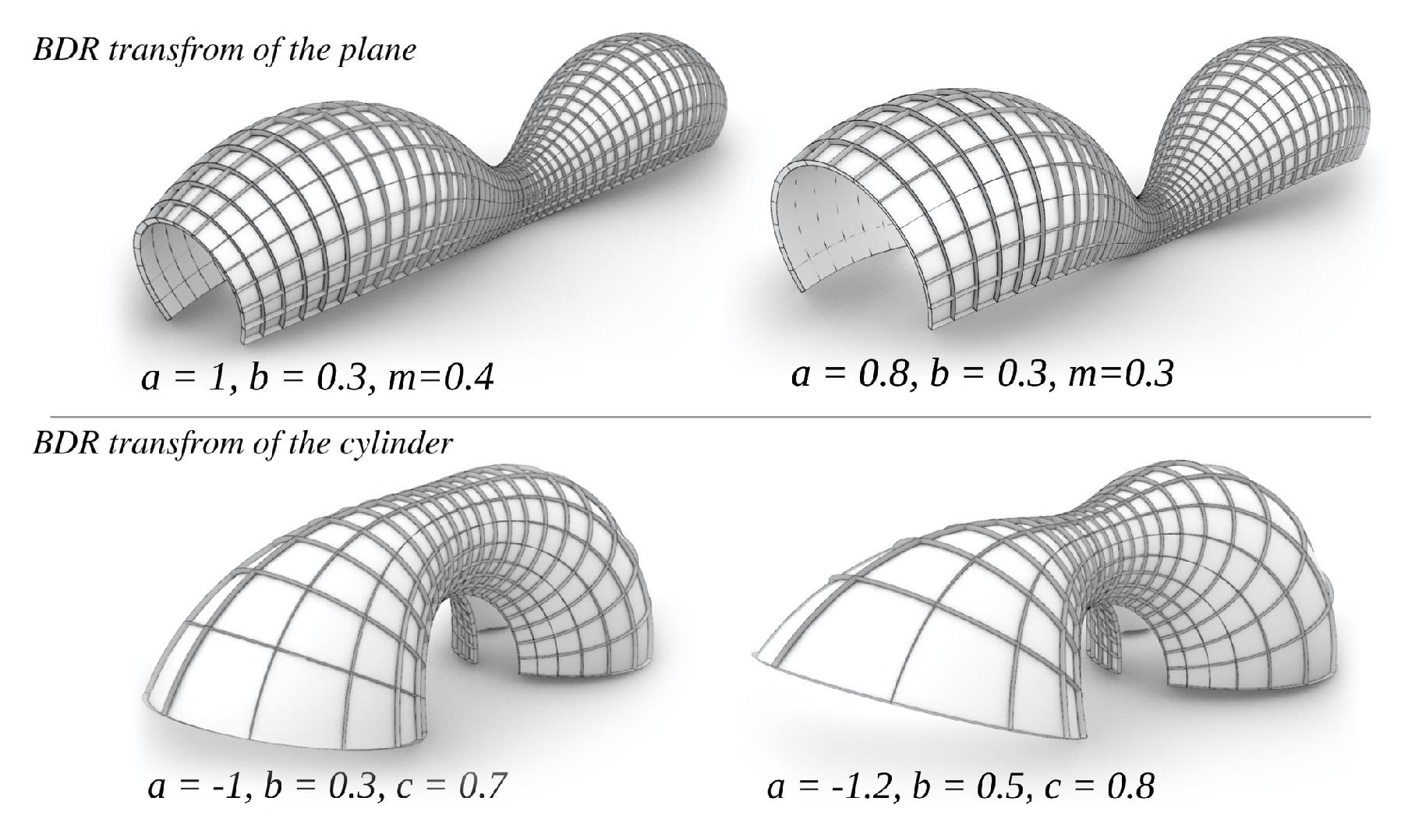

2.7. Gen-Type

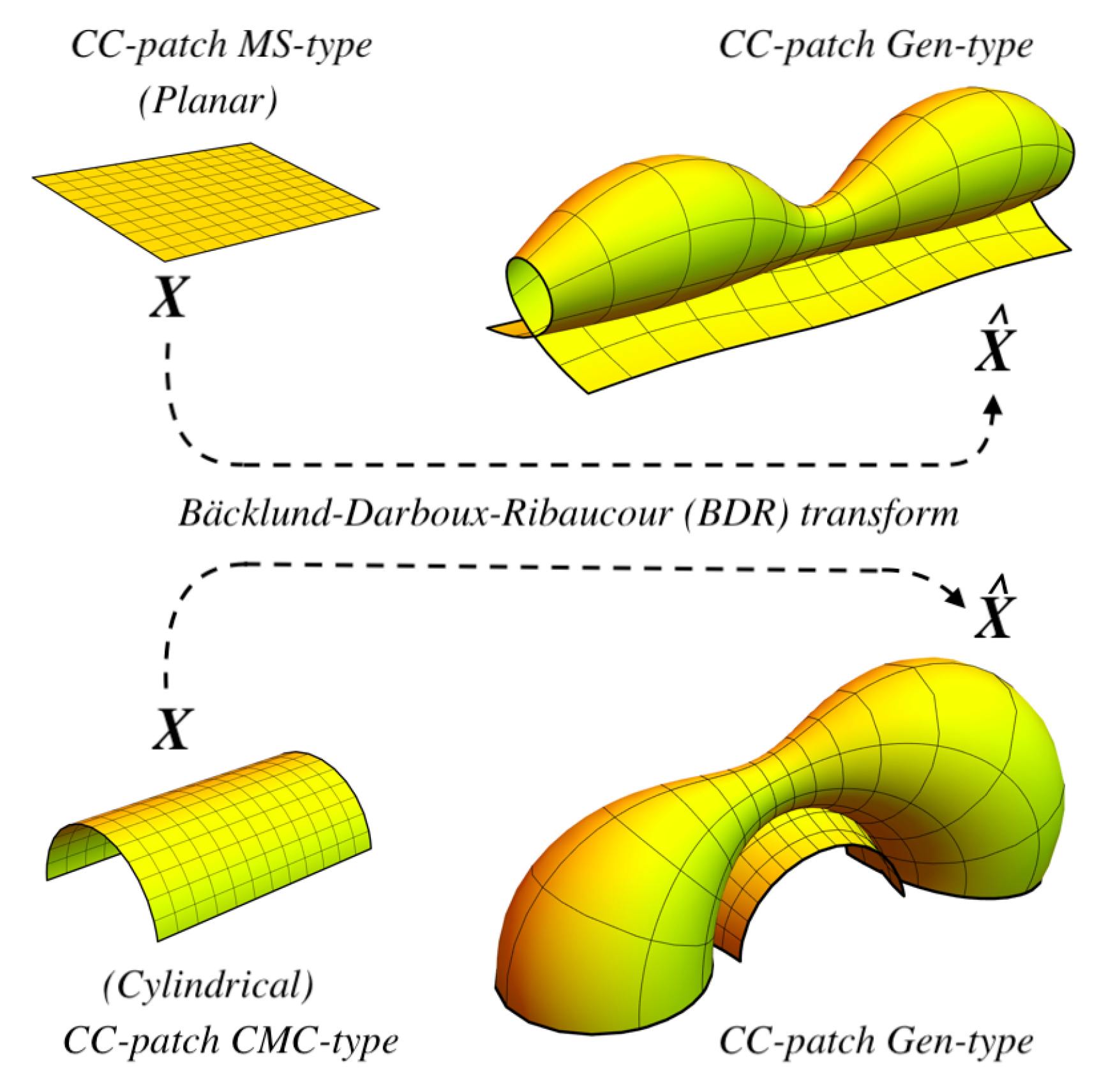

2.7.1. Gen-Type from BDR Transform

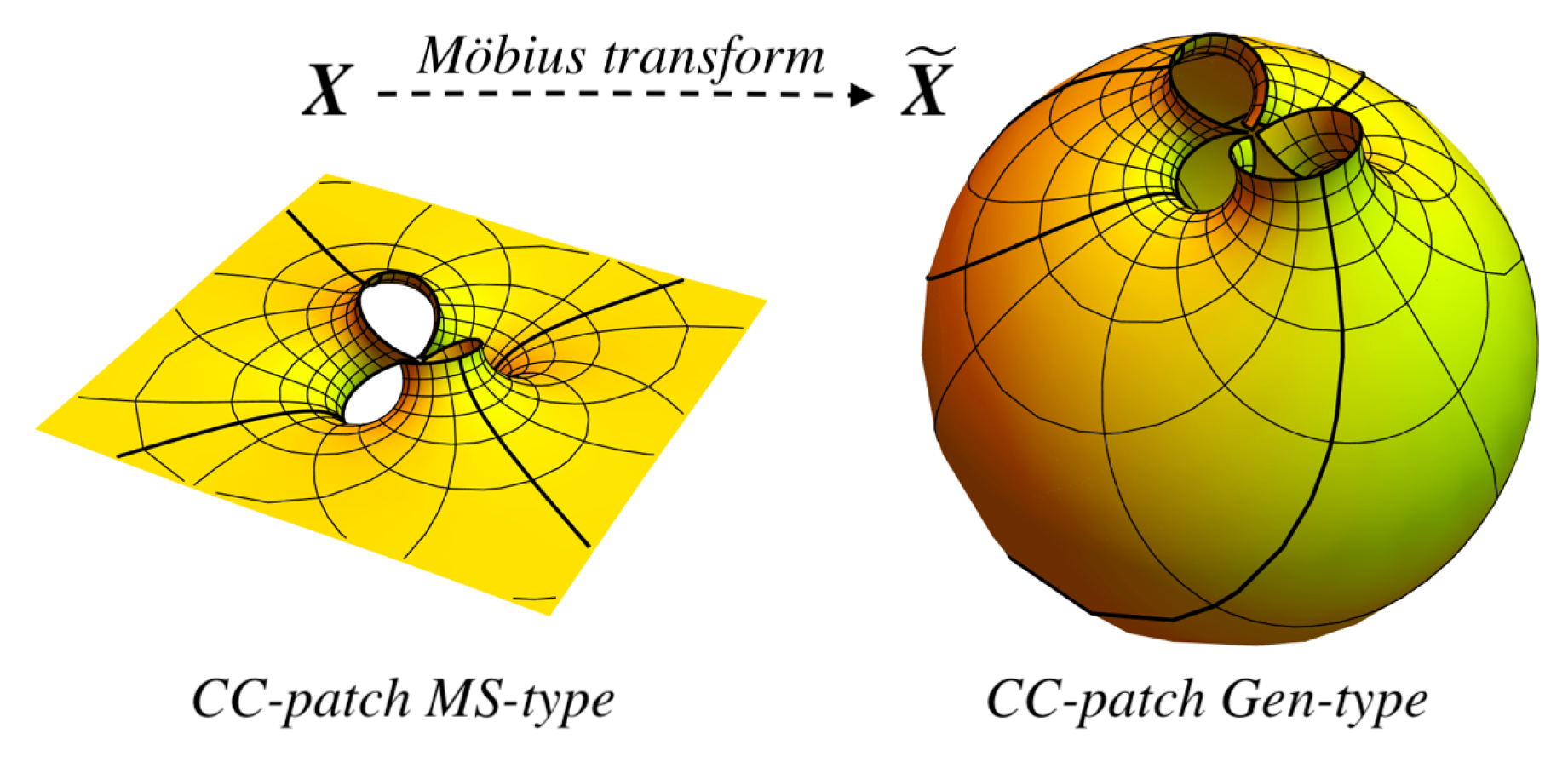

2.7.2. Gen-Type from Möbius Transform

3. Design Explorations

3.1. Design with Quad, Rev and Cyc-Types

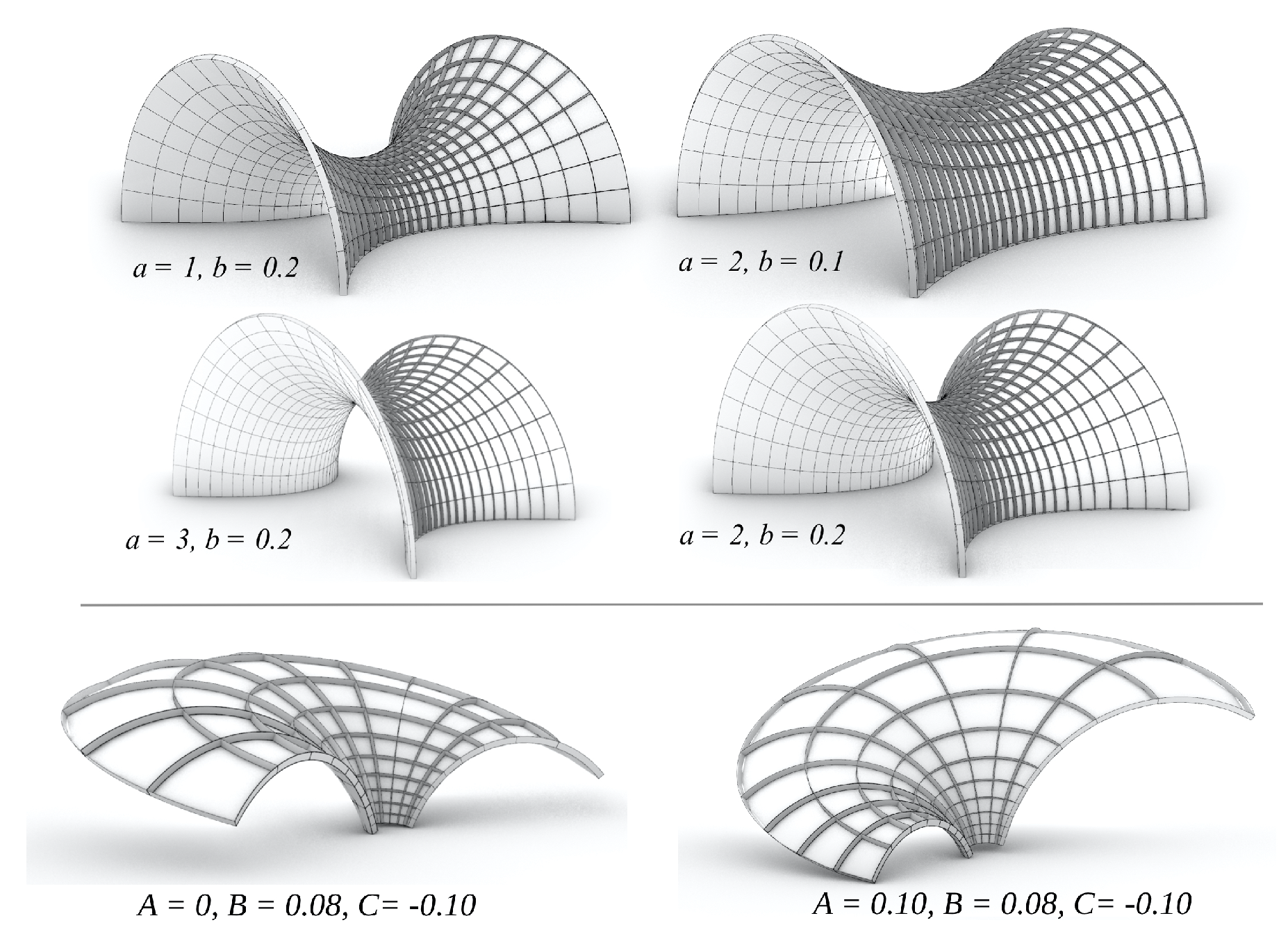

3.2. Design with MS-Type

3.3. Design with CMC-Type

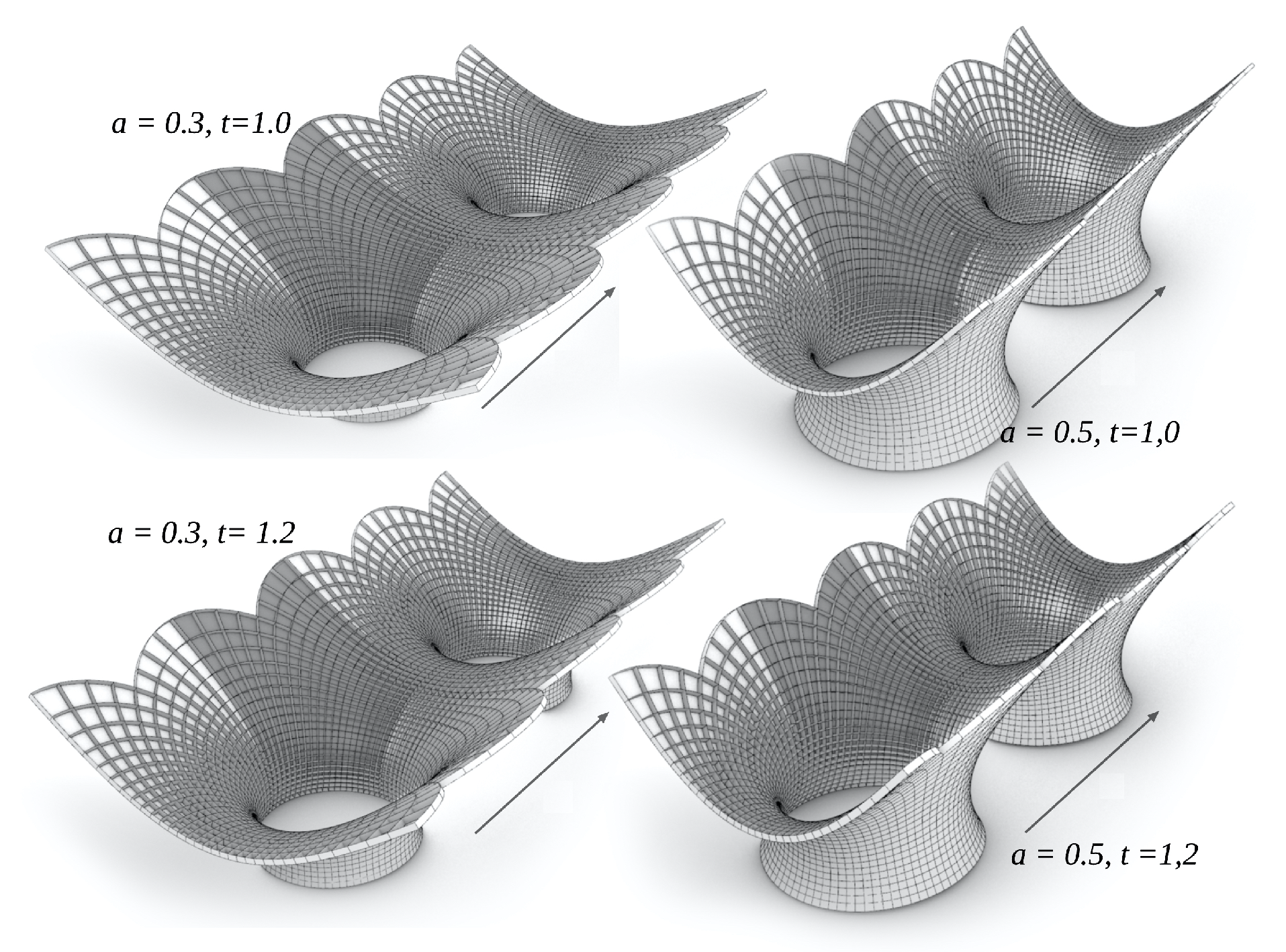

3.4. Design with Gen-Type

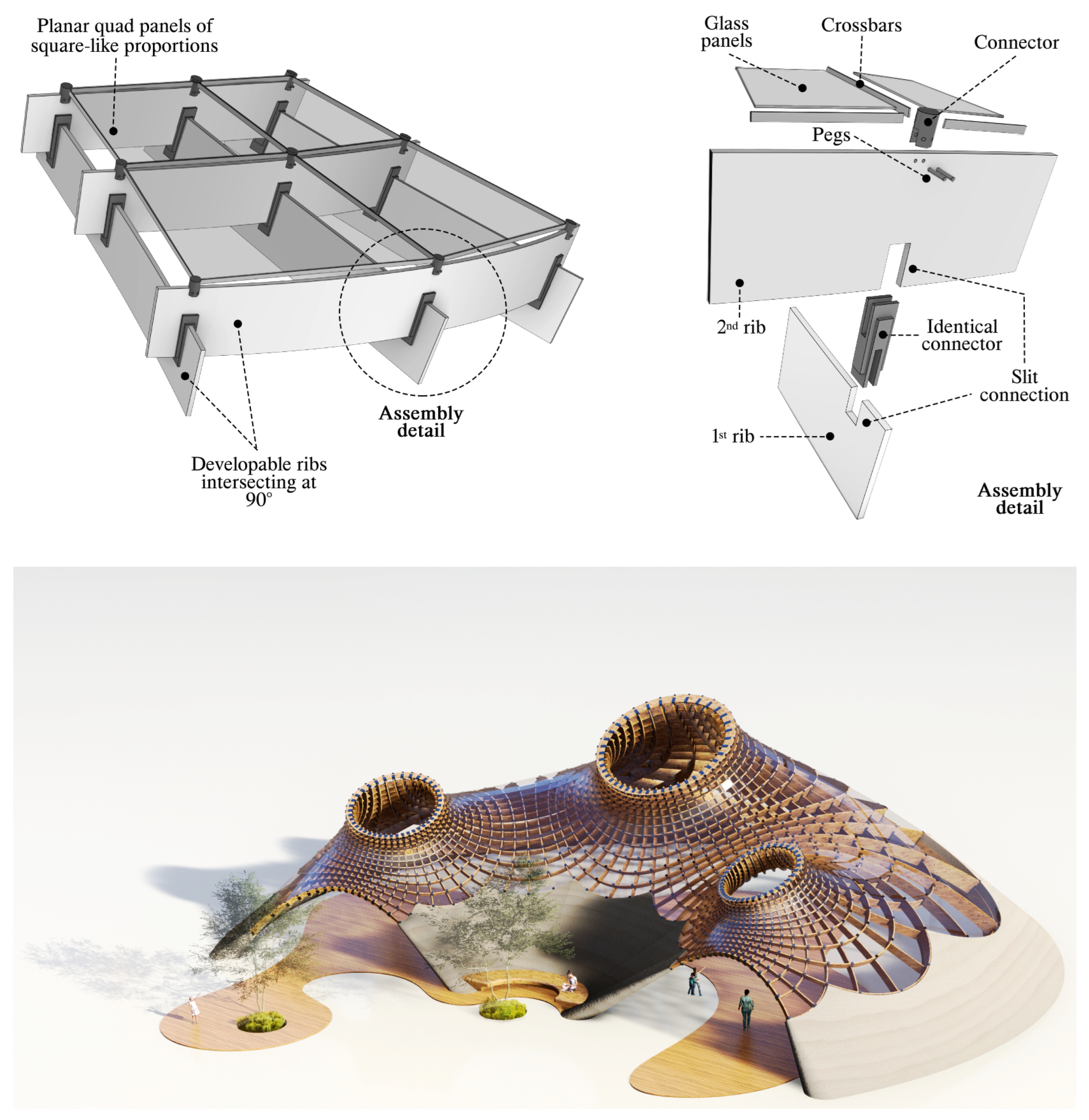

4. Prototyping

5. Conclusions

References

- Eisenhart, .L. A Treatise on Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces; Ginn and Company, 1909.

- Rogers, .C.; Schief, W.K. Bäcklund and Darboux transformations: Geometry and modern applications in soliton theory; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, 2002.

- Bobenko, .A.; Pinkall, U. Discrete isothermic surfaces. J. reine angew. Math. 1996, 475, 187 – 208. [CrossRef]

- Christoffel, .E. Ueber einige allgemeine Eigenschaften der Minimumsflächen. Crelle’s J. 1867, 67, 218 – 228. [CrossRef]

- Li, .X.; Mansouri, M.; Elshafei, A. Conformal principal-asymptotic elastic gridshells: parametric design and modular construction.

- Goursat, .E. Sur un mode de transformation des surfaces minima (1,2). Acta Math. 1887, 11, (135–186), (257–264).

- Dierkes, .U.; Hildebrandt, S.; Sauvigny, F. Minimal surfaces; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1992.

- Weber, .M. Classical Minimal Surfaces in Euclidean Space by Examples. Lec. Notes Clay Mathematical SummerSchool MSRI, Berkeley 2001.

- Bobenko, .A.; Hoffmann, T.; Springborn, B. Minimal surfaces from circle patterns: Geometry from combinatorics. Ann. of Math. 2006, 164, 231 – 264.

- Pottmann, .H.; Liu, Y.; Bobenko, A.; Wallner, J.; Wang, W. Geometry of multi-layer freeform structures for architecture. ACM Tr., Proc. SIGGRAPH 2007, 26, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Pottmann, .H.; Asperl, A.; Hofer, M.; Kilian, A. Architectural Geometry; Bentley Institute Press, 2007.

- Gray, .A.; Abbena, E.; Salamon, S. Modern differential geometry of curves and surfaces with Mathematica. 3rd Edition; Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006.

- Tošić, .Z.; Abdelmagid, A.; Lordick, D.; Baverel, O.; Elshafei, A. Pre-rationalization approach for the low-tech construction of doubly curved surfaces part-1.

- Sterling, .I.; Wente, H. Existence and classification of constant mean curvature multibubbletons of finite and infinite type. Indiana Univ. Math. Jour. 1993, 42, 1239–1266.

- Bianchi, .L. Lezioni di geometria differenziale; Pisa, 1903.

- Eisenhart, .L. Transformations of Surfaces; Princeton university press, 1923.

- Tošić, .Z. Isothermic Surfaces Python for Grasshopper, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).