1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization and the continued reliance on fossil fuels pose significant structural and environmental challenges for contemporary cities. The exponential growth in energy demand, combined with the intensification of climate change effects, highlights the vulnerability of urban infrastructure to extreme events such as heatwaves, floods, and energy crises. In this context, adopting innovative solutions becomes essential to enhance urban resilience, sustainability, and climate adaptation.

The integration of photovoltaic energy into the built environment stands out as a key strategy to optimize urban energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The development of solar neighborhoods represents an innovative approach to decentralizing electricity generation, fostering greater energy autonomy, and reducing dependence on conventional power grids. By incorporating photovoltaic systems into residential, commercial, and public buildings, these communities drive the energy transition while strengthening the security of electricity supply. Currently, the global installed capacity of photovoltaic energy exceeds 1,000 gigawatts (GW), a direct reflection of the growing importance of this technology for the energy sector and urban sustainability (IRENA, 2024) [

1].

This paper examines the role of photovoltaic energy in promoting urban resilience and climate adaptation, with a particular focus on the implementation of solar neighborhoods. Public policies, financial incentives, and strategic partnerships will be analyzed as essential mechanisms to facilitate the energy transition and expand the penetration of distributed generation in cities. The study seeks to understand the interactions between photovoltaic technology, urban planning, and sustainability, providing guidelines for the development of more efficient and resilient communities.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: (1) a review of international examples of solar neighborhoods and their key characteristics; (2) an investigation into the role of photovoltaic energy in energy security and urban efficiency; (3) an assessment of the impacts of photovoltaic technology on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating adverse climate effects; and (4) an analysis of the socioeconomic benefits resulting from the expansion of solar energy use, including job creation and reduced energy costs.

2. Methodology

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative techniques to assess the impacts of photovoltaic energy integration in urban planning. Initially, a literature review was conducted to identify international experiences with solar neighborhoods and their environmental, economic, and social impacts. The review considered academic studies, institutional reports, and government documents discussing the role of distributed generation and best practices for implementing photovoltaic solutions in various urban contexts.

For the quantitative analysis, data on the installed capacity of photovoltaic systems, their contribution to the energy matrix, and their impact on reducing greenhouse gas emissions were collected. These data were sourced from official databases, such as the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), as well as technical studies evaluating the efficiency and feasibility of urban solar systems. Comparative techniques were then applied to correlate the expansion of solar energy with energy security and urban resilience across different regions worldwide.

From a qualitative perspective, case studies of solar neighborhoods implemented in various countries were analyzed to identify challenges, opportunities, and successful strategies. This approach provided insight into the key factors influencing the adoption of photovoltaic energy as a structural solution for more sustainable cities. Additionally, public policies and government incentives that have driven the energy transition were evaluated, assessing their effectiveness in expanding the use of renewable sources in urban environments.

The combination of these approaches enabled a comprehensive analysis of the benefits and challenges of photovoltaic integration in urban planning. The findings may serve as a foundation for recommendations aimed at developing strategies and policies that promote more efficient, resilient cities aligned with the transition to a sustainable energy future.

3. Solar Neighborhoods and Photovoltaic Energy: Strategies for Energy Efficiency, Urban Resilience, and Climate Adaptation

Photovoltaic energy, by converting sunlight into electricity in a clean and silent manner, plays a central role in the transition toward more sustainable urban systems. Its integration into the built environment, particularly through solar neighborhoods, enhances urban resilience by reducing dependence on fossil fuels and minimizing energy vulnerabilities in the face of extreme climate events. Beyond emission reductions, this approach contributes to energy efficiency and the development of cities that are more adaptable to climate change.

3.1. Solar Neighborhoods: Energy Efficiency and Urban Resilience

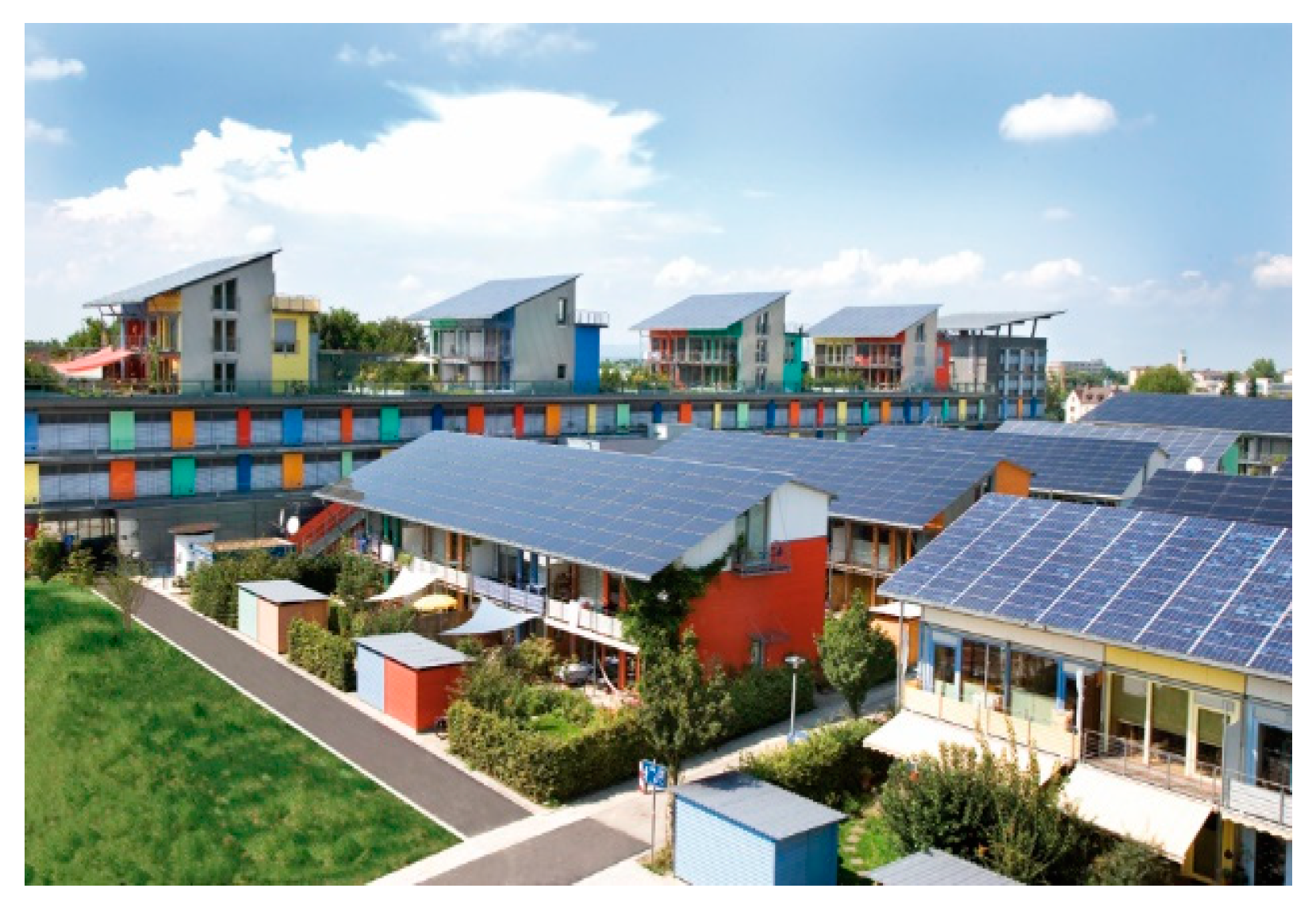

Solar neighborhoods represent an innovative urban planning strategy that combines climate adaptation, energy efficiency, and sustainability. The integration of photovoltaic energy into residential, commercial, and public infrastructure enables energy self-sufficiency in dense urban areas, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and strengthening urban resilience. Examples such as Vauban [

2] in Freiburg, Germany (see

Figure 1), and BedZED [

3] in London, United Kingdom (see

Figure 2), demonstrate how distributed generation can transform the built environment, reducing environmental impacts and promoting greater energy security.

The key feature of these neighborhoods is the strategic use of urban surfaces—rooftops, facades, and parking lots—for the installation of photovoltaic panels, maximizing solar capture and promoting distributed clean electricity generation. The incorporation of storage systems, such as batteries, enhances local grid stability, ensuring a continuous power supply even during periods of low solar irradiation. In addition to improving energy resilience, this approach contributes to the decarbonization of the urban sector and the global energy transition.

The integration of photovoltaic energy in solar neighborhoods not only reduces greenhouse gas emissions but also strengthens urban resilience by diversifying electricity sources and minimizing vulnerability to energy crises and extreme weather events. Distributed generation reduces dependence on centralized power grids, decreasing transmission losses and increasing energy efficiency. The Daiwa House solar neighborhood [

4] in Sakai, Japan (see

Figure 3), exemplifies this integrated approach, combining energy efficiency with climate adaptation strategies.

Other exemplary cases, such as the solar neighborhoods in Sünching [

5], Bavaria, Germany (see

Figure 4), and the Grow Community [

6] in Bainbridge Island, USA (see

Figure 5), demonstrate how the combination of solar generation, energy storage, and sustainable urban planning can transform urban infrastructure, enhancing energy security and climate mitigation.

The adoption of solar neighborhoods represents a strategic advancement for global urban sustainability, enhancing cities’ resilience and climate adaptation. For this transition to occur on a large scale, it is essential to implement public policies that encourage investments in sustainable energy infrastructure, alongside innovative urban planning models that integrate photovoltaic energy as a central pillar of energy efficiency and decarbonization.

3.2. Solar Neighborhoods and the Energy Transition: Strategies for Sustainability, Urban Resilience, and Energy Efficiency

The European Commission’s Mission for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030 defines a “smart city” as an urban area that integrates digital innovation and green technologies to enhance sustainability, improve quality of life, and achieve climate neutrality. These cities rely on interconnected systems to optimize resource use and reduce environmental impact, with photovoltaic energy being a central element in the transformation of urban environments (European Commission, 2020) [

7].

Around the world, various countries have been developing solar neighborhoods as part of their climate adaptation and urban resilience strategies. These projects combine energy efficiency, distributed generation, and sustainable urban planning, demonstrating the potential of solar energy in energy efficiency, resilience, and decarbonization of cities. The following are examples that illustrate this global trend.

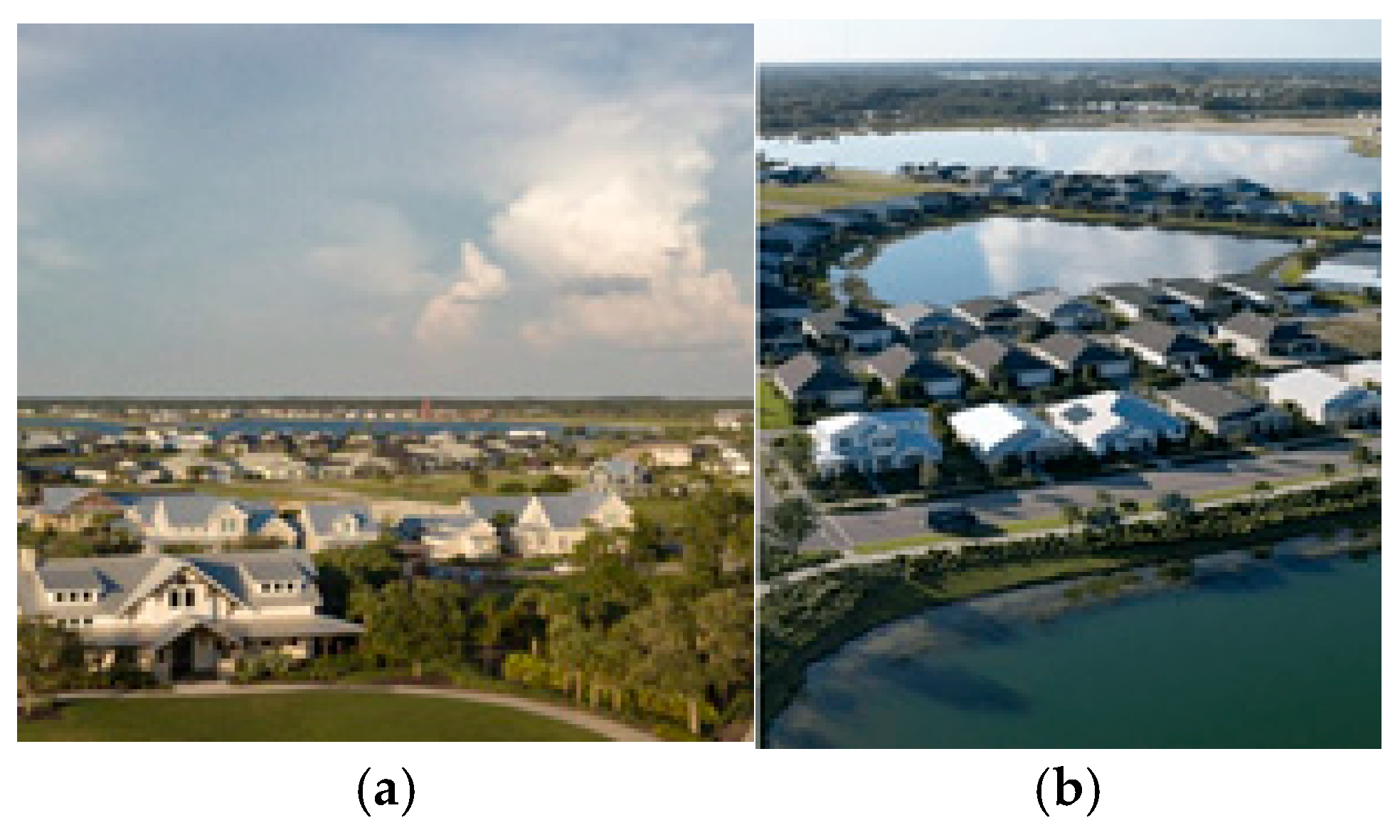

3.2.1. Babcock Ranch, USA: Sustainability and Energy Resilience

Babcock Ranch, in Florida, was designed to be the first fully solar-powered city in the USA. With 74.5 MW of installed capacity and over 300,000 photovoltaic panels, the city powers approximately 15,000 homes, avoiding emissions equivalent to those of 12,000 vehicles annually (Babcock, 2020) [

8].

In September 2022, Babcock Ranch demonstrated its resilience during Hurricane Ian, maintaining power supply and suffering minimal damage. This case reinforces the role of solar infrastructure in energy security and mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events (see

Figure 6).

3.2.2. Dubai Sustainable City, United Arab Emirates: Integration of Photovoltaic Energy and Sustainable Planning

Dubai Sustainable City exemplifies an urban model that prioritizes energy efficiency and sustainability. With 11,000 solar panels distributed across residential, commercial, and public spaces, the city generates a significant portion of its energy demand internally, reducing its carbon footprint (Dubai Sustainable City, 2021) [

9].

In addition to photovoltaic energy, the project incorporates advanced waste management strategies, water recycling, and expanded green areas, promoting an urban environment with a low environmental impact. This approach aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly regarding access to clean and affordable energy (see

Figure 7).

3.2.3. Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City, Japan: Infrastructure and Energy Self-Sufficiency

Fujisawa, located 50 km from Tokyo, represents an example of climate adaptation and energy efficiency. Developed with a

$1.3 billion investment, the city has implemented a system of distributed solar microgeneration and energy storage, covering residences, transportation, and public infrastructure. With 1,000 residences equipped with solar panels and smart energy management systems, Fujisawa strengthens its urban resilience and reduces dependence on fossil sources (Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City, 2020) [

10]. The project demonstrates the positive impact of policies promoting renewable energy in urban planning (

Figure 8).

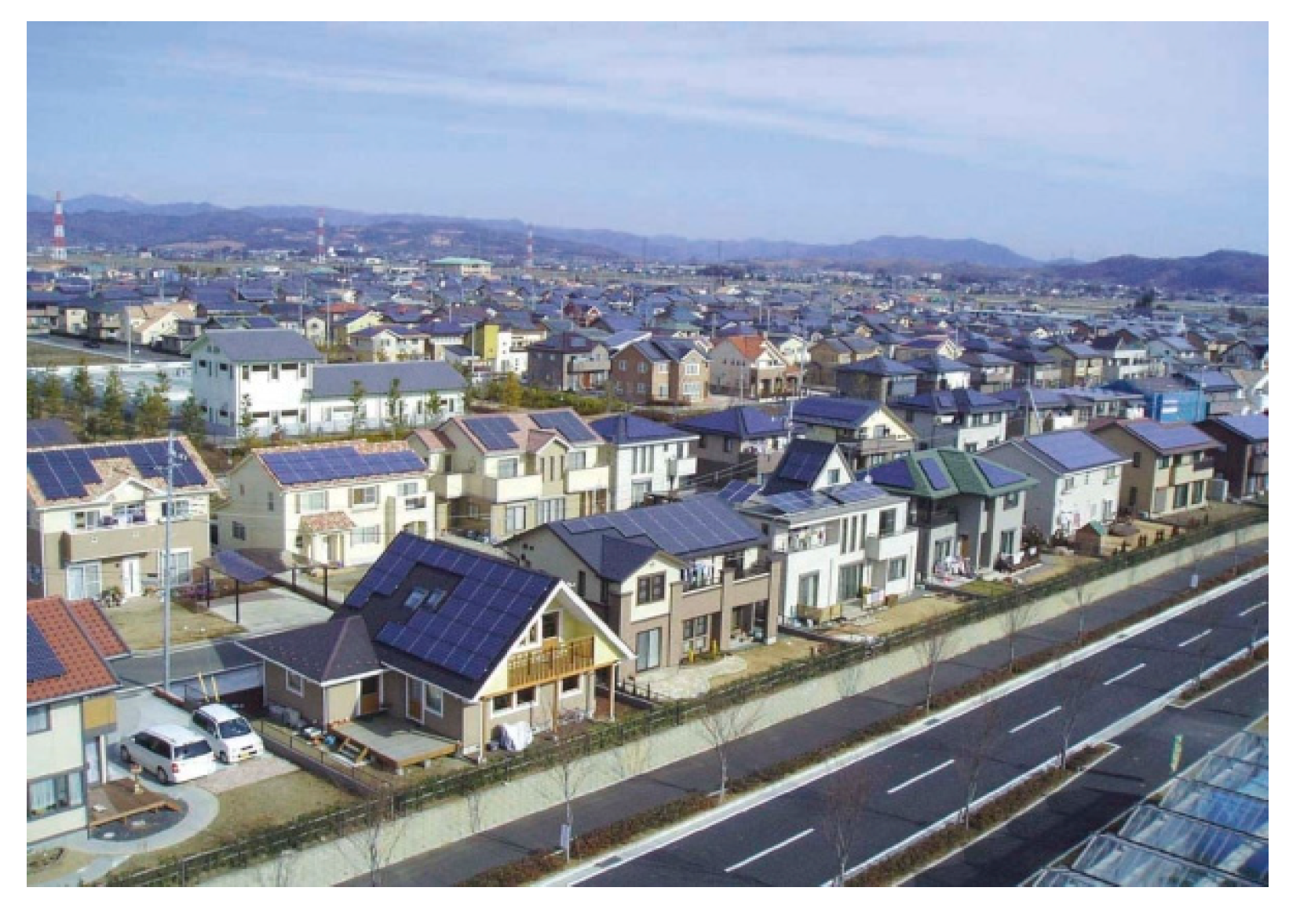

3.2.4. Ota Solar City, Japan: Urban Planning and Renewable Energy

Ota Solar City illustrates the application of public policies for the energy transition and urban sustainability. The city encourages the installation of solar panels on residential and commercial buildings, as well as integrating smart grids to optimize electrical distribution. Ota also invests in electric mobility and solar infrastructure in public spaces, establishing itself as a model for decarbonization and energy efficiency (Ota Solar City, 2021) [

11]. The initiative highlights how cooperation between governments and the private sector accelerates the implementation of sustainable energy solutions (see

Figure 9).

3.2.5. Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, Austria: Resilient Cities and Smart Infrastructure

Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, in Vienna, is one of Europe’s largest sustainable urban projects. The neighborhood integrates photovoltaic energy from the planning phase, promoting energy efficiency and connecting infrastructure to smart grid systems. The buildings were designed to maximize solar capture, while sustainable mobility is encouraged through public transport powered by renewable sources and infrastructure for electric vehicles (Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, 2021) [

12]. The project reinforces how well-structured urban policies can drive climate resilience and sustainability (see

Figure 10).

3.3. Lessons Learned and Perspectives for Urban Sustainability

The integration of photovoltaic energy into urban planning is essential for promoting urban resilience, energy efficiency, and mitigating climate impacts. Below, the key features, benefits, and lessons learned from the implementation of solar neighborhoods are analyzed, illustrating best practices in sustainability and energy transition.

3.3.1. Characteristics of Photovoltaic Energy Integration

• Decentralized Energy Generation: Photovoltaic panels are integrated into residential, commercial buildings, and urban infrastructures, optimizing energy capture and distribution.

• Energy Self-Sufficiency: Solar neighborhoods meet the local demand for electricity, reducing reliance on conventional sources and enhancing energy security.

3.3.2. Benefits of Photovoltaic Energy in Urban Planning

• Environmental Sustainability: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint contributes to more sustainable urban development.

• Energy Efficiency: Advanced technologies and optimized urban design promote lower electricity consumption and reduced operational costs.

• Urban Resilience: Diversifying the energy matrix and decentralizing energy generation strengthens cities’ ability to withstand energy crises and extreme weather events.

• Improved Quality of Life: Expanding access to clean energy and reducing air pollution foster healthier urban environments, positively impacting public health.

3.3.3. Lessons Learned from the Implementation of Solar Neighborhoods

• Integrated Planning: The viability of solar neighborhoods depends on comprehensive planning, considering regulatory, technical, and social aspects.

• Cross-Sector Collaboration: The successful implementation of photovoltaic energy requires partnerships between governments, the private sector, academia, and local communities.

• Awareness and Social Engagement: Educational campaigns about the benefits of solar energy are essential to encourage the adoption of renewable technologies and ensure the success of initiatives.

3.3.4. International Experiences in Photovoltaic Energy Integration

Case studies such as Babcock Ranch (USA), Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City (Japan), Ota Solar City (Japan), Dubai Sustainable City (UAE), and Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens (Austria) demonstrate that photovoltaic energy is a key element in the transition to more sustainable and resilient cities. The adoption of these strategies highlights the potential of solar energy to transform urban planning and contribute to resilient, low-impact infrastructure.

The integration of photovoltaic energy in urban contexts reinforces the need for effective policies, adequate financing, and technological innovation. These factors are essential to drive climate adaptation, strengthen urban resilience, and promote energy efficiency on a global scale.

The analysis of international experiences shows that the integration of photovoltaic energy in urban planning plays a crucial role in climate adaptation, urban resilience, and energy efficiency. The success of these projects reinforces the importance of public policies and technological innovations to enable sustainable and self-sufficient solar neighborhoods capable of facing climate challenges and the growing demand for clean energy.

3.3.5. Challenges and Strategies for Implementation

Although solar neighborhoods are an efficient solution for urban sustainability, their implementation faces technical, economic, and regulatory challenges. Despite the reduction in photovoltaic system costs over the past decades, the initial investment still represents a barrier to large-scale adoption. To enable this transition, public policies and financial incentives, such as subsidies and accessible credit lines, are crucial to expand access to solar energy and accelerate the decarbonization of the built environment.

In addition to financial aspects, collaboration between different sectors and societal engagement are essential for the success of these projects. Creating solar neighborhoods requires cooperation between architects, urban planners, energy companies, governments, and citizens. Raising awareness of the environmental, social, and economic benefits of photovoltaic energy strengthens the culture of sustainability and encourages the adoption of innovative solutions.

3.4. Photovoltaic Energy and Urban Resilience in Remote Areas: The Limeira Village Model

The transition to renewable energy sources plays a key role in promoting climate adaptation, resilience, and energy efficiency not only in urbanized areas but also in remote regions. The solar microgrid in Limeira Village [

13] represents the implementation of photovoltaic energy as a sustainable solution, standing out as a model for the development of solar neighborhoods and resilient infrastructure (

Figure 11).

Located in the Médio Purus Extractive Reserve, in the state of Amazonas, Vila Limeira was founded in the 1950s during the rubber boom. For decades, the community faced energy limitations, with electricity provided for only three hours a day by a diesel generator. The high operational costs made it difficult to adopt sustainable energy solutions and hindered local development.

In 2018, the community, in partnership with Apavil (Association of Agroextractivist Producers of the Assembly of God of Vila Limeira), WWF-Brazil, and the Mott Foundation, launched the “Vila Limeira 100% Solar” project with the aim of replacing the diesel matrix with an efficient and low environmental impact photovoltaic system. The solar power plant installation was completed in August 2022, following delays caused by the pandemic.

The implemented system consists of an off-grid microgrid (Isolated Microgeneration and Energy Distribution System - MIGDI) with a capacity of 30 kWp, incorporating lithium batteries and individual meters. This infrastructure ensures a continuous power supply for homes, the school, and the community center. Additionally, the active participation of residents in its construction and maintenance strengthens community autonomy and promotes long-term sustainability.

The adoption of photovoltaic energy brought significant impacts to Vila Limeira, including improved quality of life, expanded access to nighttime education, use of information technologies, and support for local productive activities. It became the first community in southern Amazonas to operate with uninterrupted solar electricity, consolidating itself as a reference for clean energy projects, energy efficiency, and resilience in remote areas.

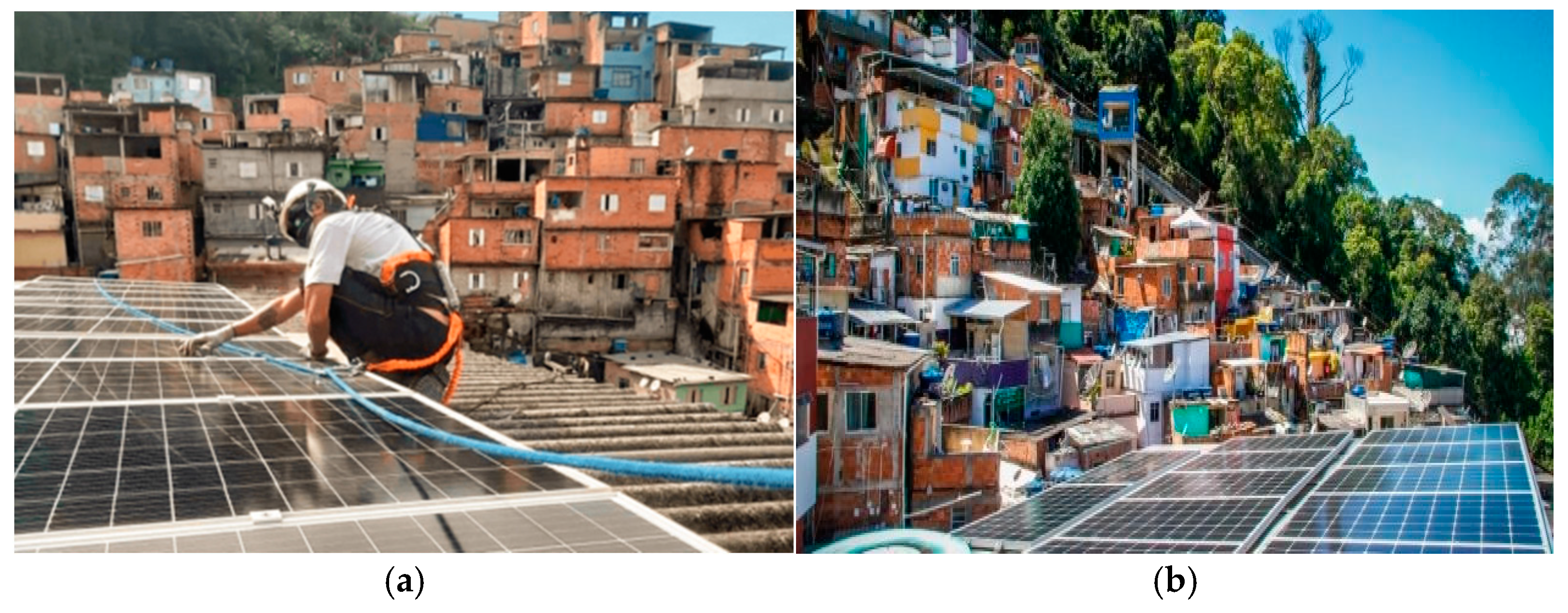

3.5. Solar Neighborhoods and Urban Resilience: The Case of Favela Marte

Favela Marte [

14], also known as Vila Itália, located in São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, could become a reference for urban adaptation and resilience through the integration of photovoltaic energy. A large project is underway to supply the community with solar energy, promoting energy efficiency, sustainability, and social development (

Figure 12).

Since its founding in 2014, the community has faced challenges related to land regularization and urban infrastructure. However, its selection as a pilot site for the “Favela 3D” project marks a new phase, promoting dignified housing and energy efficiency through the adoption of solar energy.

This initiative, led by the NGO Gerando Falcões, is supported by public and private partnerships. Banco BV and the fintech Meu Financiamento Solar are financing the installation of photovoltaic systems in 240 homes in the community.

By June 2024, over 1,000 solar panels will be installed in residences and community spaces. To enable this project, the Companhia de Desenvolvimento Habitacional e Urbano (CDHU) is building social housing designed for integration with solar systems.

The impacts for residents are significant. It is estimated that each family will save between R$ 4,000 and R$ 6,000 annually in electricity costs. As a result, residents will only pay the minimum tariff set by the distributor, promoting financial relief and greater economic stability.

The Director of Social Technologies at Gerando Falcões highlights the essential role of this project in reducing poverty: “Initiatives like this, which provide access to renewable energy in vulnerable communities, are crucial to strengthening urban resilience and fostering social inclusion.”

In addition to the installation of photovoltaic systems, funders are offering technical training so that residents can participate in the installation and maintenance of the solar structures. This training professionalizes the local workforce, creating job opportunities and economic autonomy.

Public sector involvement is essential to the success of this solar neighborhood model. Measures such as land regularization and improvements in urban infrastructure—including water supply, sewage systems, electricity, and paving—are crucial for consolidating a sustainable and resilient urban environment.

The solar neighborhood project in Favela Marte demonstrates how photovoltaic energy can contribute as a driver of urban transformation, promoting energy efficiency, sustainability, and improved quality of life. This action model can inspire similar initiatives in diverse urban contexts, expanding the reach of sustainable solutions to address climate change and build more resilient cities.

3.6. Comparative Analysis: Solar Microgrids and Individual Systems in Promoting Urban Resilience and Energy Efficiency

The decision between implementing a solar microgrid for collective supply, as applied in Vila Limeira, or the individualized installation of photovoltaic panels in housing units, as in Favela Marte, requires a detailed analysis of their advantages and challenges. Examples such as the Larch Park Solar Community [

15] in Canada (

Figure 13) and the Solar Townhouse project [

16] in the Philippines (

Figure 14) illustrate different approaches to integrating solar energy into urban environments.

3.6.1. Solar Microgrids for Collective Supply

Advantages:

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability: Concentrating photovoltaic generation in a single infrastructure enables greater efficiency in distribution and reduces energy losses.

Centralized Management and Urban Resilience: A unified system facilitates monitoring, maintenance, and the implementation of technologies to optimize urban resilience in the face of extreme weather events.

Space Optimization: The microgrid can be designed to use common areas, such as shared rooftops, without compromising the individual structure of housing units.

Challenges:

Infrastructure and Distribution: The need for a reliable transmission infrastructure involves additional costs and detailed planning.

Operational Complexity: Centralized management requires technical knowledge for system maintenance and operation.

Dependence on a Single System: Any failures can impact all units, compromising residents’ energy autonomy.

3.6.2. Individual Photovoltaic Systems in Housing Units

Advantages:

Energy Autonomy and Adaptation: Each housing unit can operate independently, adjusting to variations and individual consumption demands.

Efficiency and Reduction of Losses: Decentralized generation minimizes energy transmission losses, increasing system efficiency.

Flexibility in Implementation: Each unit can customize its photovoltaic capacity based on need and resource availability.

Challenges:

High Initial Cost: Individual installations can represent a significant initial investment, making it difficult to expand access to the technology.

Decentralized Management: Maintenance and operation become individual responsibilities, potentially leading to inefficiency in collective energy management.

Structural and Aesthetic Limitations: Not all units have adequate space for the efficient installation of solar panels, compromising generation capacity.

The choice between solar microgrids and individual systems should consider factors such as public policies, regulation, climate conditions, and availability of funding. Both solutions contribute to urban sustainability, energy efficiency, and resilience of built environments. The final decision should be based on a thorough technical analysis, considering the benefits and challenges inherent to each approach.

3.7. Photovoltaic Energy as a Strategy for Urban Resilience and Climate Adaptation in Crisis Contexts

The increasing occurrence of extreme weather events has exposed the vulnerability of urban infrastructures and highlighted the need for resilient energy solutions. The recent floods in Rio Grande do Sul [

17] emphasized the urgency of alternatives to ensure the continuity of electricity supply during emergencies. During this crisis, approximately 470,000 consumer units faced power interruptions, and nearly half of the cities in the region remained without electricity for 20 days after the event (

Figure 15).

In this context, photovoltaic energy emerges as a strategic solution to increase urban resilience and ensure energy efficiency in emergency scenarios. In addition to being a renewable and economically viable source, distributed solar energy generation enables a rapid response to natural disasters. Among the technological innovations, solar containers [

18] appear as an effective alternative for providing temporary electricity in affected regions. These modular systems allow for the rapid installation of micro solar plants, ensuring the operation of essential services in critical situations.

The solar container is a mobile photovoltaic system, designed for transport via different modes such as ships, trains, and trucks. Equipped with solar rails and an automated assembly mechanism, it can be installed in about five hours. Each unit contains 240 solar panels and has a capacity of 140 kW, allowing it to generate approximately 15,000 kWh per month at strategic locations. This production is enough to power around 100 homes with an average consumption of 150 kWh per month (

Figure 16).

The application of solar containers is extensive and can address various scenarios. In emergencies, they provide electricity for field hospitals, rescue centers, and temporary shelters. Additionally, in off-grid contexts, they represent a viable solution for isolated communities without access to the conventional power grid. This versatility positions the technology as a crucial element for strengthening urban resilience and enabling climate adaptation in an increasingly climate-vulnerable world.

The advancement of photovoltaic energy is a global phenomenon, driven by the reduction in solar system costs and the strengthening of policies promoting sustainability. In January 2023, the prices of photovoltaic systems experienced an average drop of 30% compared to the previous year, favoring their expansion on different scales. The growth of solar energy, both on-grid and off-grid, reinforces its potential to enhance energy efficiency and urban infrastructure resilience.

The integration of solar energy into urban planning is a critical step toward consolidating sustainable solar neighborhoods, promoting energy autonomy and reducing environmental impacts. The implementation of solutions like solar containers can play an important role in energy security and the maintenance of essential services during crises, significantly contributing to the transition toward more resilient cities adapted to climate change.

4. Trends And Advancements In Urban Energy Transition

Although some regions are still in the early stages of developing photovoltaic energy projects compared to internationally recognized initiatives like Babcock Ranch, Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City, Ota Solar City, Dubai Sustainable City, and Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, significant progress has been made in the opportunities for adopting sustainable solutions, with a focus on the implementation of solar neighborhoods and energy efficiency in urban infrastructures.

In 2024, solar capacity expansion reached significant milestones, adding over 9 GW of photovoltaic energy, representing more than 80% growth compared to the previous year, according to data from the National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) [

19]. Distributed generation showed considerable progress, with cities like Florianópolis [

20] leading the integration of photovoltaic systems, installing 314 MW of solar capacity. States such as São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio Grande do Sul also showed remarkable growth in the adoption of decentralized energy generation systems (see

Figure 17). According to ANEEL, more than 50% of the installed capacity in 2024 corresponds to residential photovoltaic systems.

These advancements highlight the crucial role of photovoltaic energy in promoting urban resilience and transitioning to a more sustainable energy model. The implementation of solar systems is an essential strategy for mitigating climate impacts and improving energy efficiency in cities. Aligning with international best practices, the growth of solar energy contributes to climate adaptation and can serve as a reference for other regions interested in expanding distributed generation and consolidating solar neighborhoods.

The future of solar energy presents promising prospects, with vast potential for expansion. The continued growth of the sector, coupled with increased awareness of the benefits of photovoltaic technologies and the development of new energy solutions, is essential to strengthen sustainability and the resilience of cities in the face of global climate challenges.

5. Results

The findings of this study emphasize that photovoltaic energy plays a key role in urban resilience and sustainability, highlighting the implementation of solar neighborhoods as a critical strategy for climate adaptation. The analysis of international experiences shows that these neighborhoods not only improve energy efficiency but also significantly reduce the carbon footprint of cities.

Case studies demonstrate that solar neighborhoods can achieve high levels of energy self-sufficiency, providing enough electricity for residential and commercial buildings. This model reduces reliance on conventional energy sources and strengthens energy security, mitigating vulnerabilities in the energy supply.

In addition to the positive environmental impact, the transition to solar neighborhoods drives local economic growth, creating direct and indirect jobs in the renewable energy sector. The reduction in electricity costs also results in financial benefits for residents and productive sectors.

However, the implementation of these neighborhoods faces structural and regulatory challenges. Effective public policies, government incentives, and modernization of electrical infrastructure are crucial to making this transition feasible. Innovative financing models and public-private partnerships play a vital role in scaling these initiatives.

The key benefits observed include:

Reduction in carbon footprint and improvement in urban environmental quality;

Strengthening of urban resilience and energy security;

Increase in energy self-sufficiency and reduction in dependence on fossil fuels;

Stimulus for economic development and technological innovation;

Improvement in quality of life, promoting access to clean energy and healthier urban environments.

6. Conclusion

In light of the increasing frequency of extreme climate events and threats to urban security, integrating photovoltaic energy into urban planning stands as a strategic solution for enhancing urban resilience. The implementation of solar neighborhoods presents itself as an innovative and effective model for addressing challenges related to climate adaptation, energy efficiency, and decarbonization.

For this transition to occur effectively, a coordinated commitment from governments, the private sector, and local communities is necessary. Solid public policies, attractive financial incentives, and investments in infrastructure are crucial to accelerating the expansion of this model. Additionally, raising awareness of the benefits of sustainable practices and training professionals are determining factors in maximizing the positive impacts of this urban transformation.

The evolution of solar neighborhoods represents a significant opportunity to promote more sustainable and equitable urban development, aligned with global climate mitigation goals. By prioritizing renewable energy-based solutions, cities can become more resilient, efficient, and prepared for future environmental and energy challenges.

References

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/.

- Vauban, Freiburg, Germany. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.rolfdisch.de/projekte/die-solarsiedlung/.

- BedZED, London, United Kingdom. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/nZEB-community-Zero-carbon-homes-United-Kingdom-Source-Photograph-taken-from-the_fig10_348695218.

- Daiwa House Solar Neighborhood, Sakai City, Japan. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.daiwahouse.com/English/about/community/case/harumidai/.

- Solar Neighborhood, Sünching, Bavaria, Germany. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.cesf.com.au/projects/green-grid-energy-systems.

- Solar Neighborhood, Grow Community, Bainbridge Island, USA. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://growbainbridge.com/.

- European Commission. Europe 2020. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf.

- Babcock Ranch, USA. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://babcockranch.com/.

- Dubai Sustainable City, United Arab Emirates. Accessed on November 10, 2024. Available online: https://thesustainablecity.com/.

- Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City, Japan. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://fujisawasst.com/EN/project/.

- Japan Ota Solar City, Japan. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Layout-of-the-Pal-Town-neighborhood-in-Ota-City-Black-dots-show-casas-com-telhado-PV_fig1_255250099.

- Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, Austria. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.aspern-seestadt.at/en.

- Vila Limeira, 100% Solar Community in Southern Amazonas, Brazil. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.br/?79869/conheca-a-primeira-comunidade-100-porcento-solar-do-sul-do-amazonas.

- Favela Marte, Brazil. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/979022/favela-em-sao-paulo-sera-totalmente-abastecida-por-energia-solar.

- Larch Park Solar Community, Edmonton, Canada. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://skyfireenergy.com/case-study-home/larch-park-solar-community-edmonton-alberta/.

- Bicolandia Solar Townhouse, Iriga City, Philippines. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://edgebuildings.com/project-studies/victoria-highlands-subdivision-vhs/.

- Impact of Power Outage during the Tragedy in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/economia/macroeconomia/ao-menos-534-mil-casas-ficaram-sem-luz-na-tragedia-do-rs-150-mil-foram-religadas-diz-ministerio/.

- Solar Container System. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.solarcontainer.one/english/product-information.

- National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL). Installed Capacity by Federation Unit. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://dadosabertos.aneel.gov.br/dataset/capacidade-instalada-por-unidade-da-federacao/resource/6fbee0f8-2617-4879-a69a-6b7892f12dad.

- Solar Energy in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Accessed on February 10, 2025. Available online: https://www.portalsolar.com.br/energia-solar-em-santa-catarina-sc.

Figure 1.

Vauban, Freiburg, Germany.

Figure 1.

Vauban, Freiburg, Germany.

Figure 2.

BedZED, London, United Kingdom.

Figure 2.

BedZED, London, United Kingdom.

Figure 3.

Daiwa House, Solar Neighborhood, Sakai, Japan.

Figure 3.

Daiwa House, Solar Neighborhood, Sakai, Japan.

Figure 4.

Solar Neighborhood, Sünching, Bavaria, Germany.

Figure 4.

Solar Neighborhood, Sünching, Bavaria, Germany.

Figure 5.

Solar Neighborhood, Grow Community, Bainbridge Island, USA.

Figure 5.

Solar Neighborhood, Grow Community, Bainbridge Island, USA.

Figure 6.

(a) and (b): Babcock Ranch, USA.

Figure 6.

(a) and (b): Babcock Ranch, USA.

Figure 7.

Dubai Sustainable City, United Arab Emirates.

Figure 7.

Dubai Sustainable City, United Arab Emirates.

Figure 8.

Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City, Japan.

Figure 8.

Fujisawa Sustainable Smart City, Japan.

Figure 9.

Japan Ota Solar City, Japan.

Figure 9.

Japan Ota Solar City, Japan.

Figure 10.

(a–d): Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, Austria.

Figure 10.

(a–d): Aspern-Die-Seestadt-Wiens, Austria.

Figure 11.

(a,b): Vila Limeira, 100% Solar Community in Southern Amazonas, Brazil.

Figure 11.

(a,b): Vila Limeira, 100% Solar Community in Southern Amazonas, Brazil.

Figure 12.

(a,b): Solar Energy in Favela Marte, Brazil.

Figure 12.

(a,b): Solar Energy in Favela Marte, Brazil.

Figure 13.

Larch Park Solar Community, Edmonton, Canada.

Figure 13.

Larch Park Solar Community, Edmonton, Canada.

Figure 14.

Bicolandia Solar Townhouse, Iriga City, Philippines.

Figure 14.

Bicolandia Solar Townhouse, Iriga City, Philippines.

Figure 15.

(a,b): Impact of Power Outages During the Tragedy in Rio Grande do Sul - Aerial images illustrating the extent of the blackout and the number of affected homes.

Figure 15.

(a,b): Impact of Power Outages During the Tragedy in Rio Grande do Sul - Aerial images illustrating the extent of the blackout and the number of affected homes.

Figure 16.

(a,b): Solar Container System - Schematic representation of the Solar Container, highlighting its design and features for temporary energy generation in emergency situations.

Figure 16.

(a,b): Solar Container System - Schematic representation of the Solar Container, highlighting its design and features for temporary energy generation in emergency situations.

Figure 17.

(a–c): Solar Energy and its Geographical Distribution.

Figure 17.

(a–c): Solar Energy and its Geographical Distribution.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).