1. Introduction

Globally, renewable energy policies have become essential instruments in shaping a sustainable future. These strategies address interconnected challenges such as climate change, environmental degradation, and energy insecurity by accelerating the shift to clean energy sources (IEA 2022, IPCC 2023). Transitioning to renewables reduces greenhouse gas emissions, improves air quality, and mitigates the impacts of global warming. Moreover, it enhances national energy security by lowering dependence on imported fossil fuels and promoting domestic energy independence (REN21 2022).

Dubai South1,2, a smart and sustainable city emerging in the UAE, exemplifies how renewable energy strategies can be effectively integrated into large-scale urban developments. Strategically located near the planned Al Maktoum International Airport and operating as a free economic zone with pro-investment policies, it has attracted significant global interest. Sustainability is central to its planning vision, demonstrated by the implementation of smart grids and solar energy systems in alignment with Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) standards (DEWA 2023).

Dubai South’s integrated approach, combining infrastructure scalability, regulatory support, and technological readiness, makes it an ideal testbed for renewable energy deployment. More importantly, it serves as a replicable model for other high-growth cities, such as logistics hubs, special economic zones, and greenfield urban developments, seeking to implement clean energy strategies that are adaptive, future-ready, and sustainable.

This paper proposes a comprehensive renewable energy integration strategy designed for multi-sector urban environments, with Dubai South as a representative case. As a rapidly developing aerotropolis that encompasses aviation, logistics, commercial, and residential functions, Dubai South illustrates the complexities and opportunities that similar urban ecosystems face. The strategy aligns with global sustainability goals, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN 2015), the Dubai Clean Energy Strategy 2050 (Dubai Supreme Council of Energy 2024) and the UAE’s Net Zero by 2050 initiative (UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment 2022). It incorporates technical, financial, and regulatory dimensions to promote operational efficiency, resilience, and long-term sustainability.

To develop this strategy, this article reviews global best practices, theoretical frameworks, including Sustainable Strategic Management (SSM) and Energy Management Systems (EMS), and national policy directions, particularly those shaped by the UAE’s leadership during COP28 (Nwigwe, et al. 2024). Special attention is given to enabling technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), and smart grids, which are essential for efficient energy planning and real-time system optimization (Zhang, Han and Deng 2018, Velasquez, Moreira-Moreira and Alvarez-Alvarado 2024). This integration of global insights with local realities forms the basis of a scalable, context-specific roadmap.

To structure and evaluate the integration strategy, this study follows a comprehensive methodological framework described in

Section 2, which then informs the results presented in

Section 3

1.1. Global Practices in Renewable Energy Integration

The global implementation of renewable energy strategies provides valuable foundation of best practices that can be adopted to Dubai South’s unique energy profile and its ambitious urban goals. Among the most relevant innovations are smart grid technologies and AI-driven energy systems, which have proven effective in enhancing operational efficiency and energy resilience. For example, (Moreno Escobar, et al. 2021) and (Zhang, Han and Deng 2018) emphasized the role of AI in improving real-time responsiveness and optimizing grid performance. Such technologies are particularly important in dynamic urban environments like Dubai South, where energy demand fluctuates across residential, commercial, and logistics sectors. AI can facilitate the creation of a responsive, secure, and adaptable energy network capable of meeting variable loads with high reliability and efficiency.

In addition to digital technologies, hybrid renewable energy systems offer critical insights for maintaining supply stability. (Olatomiwa, et al. 2016) highlighted the effectiveness of combining renewable sources with backup storage systems to overcome intermittency challenges. Similarly, (Gulzar, et al. 2022) discussed how load frequency controllers (LFCs) can be used within hybrid systems to manage frequency fluctuations and prevent disruptions in energy supply. For Dubai South, the integration of such systems—featuring renewable sources, storage solutions, and real-time control mechanisms—can ensure continuous power availability for energy-intensive sectors like logistics and aviation, even during peak demand.

Case studies from diverse global regions also offer valuable lessons. In Alaska, (Holdmann, Wies and Vandermeer 2019) demonstrated how renewable microgrids can stabilize energy access in remote communities through adaptive, site-specific design. Although Dubai South presents a different urban context, the principles of distributed energy deployment are equally applicable, particularly in expanding logistics zones and new residential developments. Likewise, (Furmankiewicz , et al. 2020) examined Poland’s approach to incentivizing renewable energy adoption in rural communities. Applying comparable incentive structures in Dubai South could help balance energy investments between high-demand commercial areas and emerging residential zones, fostering equitable and widespread adoption of clean energy solutions.

Finally, policy alignment with global climate initiatives reinforces the long-term success of renewable strategies. (Ozdemir, et al. 2023) emphasized the importance of integrating local energy goals with international commitments, particularly those articulated during COP28. Dubai South stands to benefit from the UAE’s leadership in these global forums, especially through access to climate finance, carbon capture investments, and renewable energy partnerships. Aligning Dubai South’s roadmap with the UAE’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) not only advances its clean energy ambitions but also strengthens its role as a model for sustainable, future-ready urban development across the Middle East.

1.2. Theoretical and Strategic Frameworks (SSM, EMS, FSAs, COP28 Alignment)

Developing a robust renewable energy strategy for Dubai South requires the integration of both theoretical and strategic frameworks that address sustainability from operational, economic, and policy perspectives. These frameworks guide decision-making by aligning technological implementation with long-term environmental and economic goals.

Sustainable Strategic Management (SSM), as proposed by (Szymczyk 2019) provides a model that balance profitability with environmental and social values. This model supports the integration of sustainability into the core of organizational strategy rather than treating it as an external compliance factor. In the context of Dubai South, SSM provides a foundation for combining economic performance with ecological stewardship; an approach that reinforces the city’s identity as a smart, sustainable urban hub.

From a competitiveness standpoint, the concepts of Firm-Specific Advantages (FSAs) and Country-Specific Advantages (CSAs) offer additional strategic insight. (Patchell and Hayter 2021) explained regions that invest in sustainable infrastructure and supportive policy environments gain long-term economic benefits and attract sustainability-oriented businesses. For Dubai South, aligning renewable energy goals with national frameworks enhances its position as a magnet for international investment and a model for clean, innovation-driven development.

On the operational side, Energy Management Systems (EMS) are vital for ensuring that energy production, distribution, and consumption are balanced efficiently in real time. (Olatomiwa, et al. 2016) discussed EMS’s role in optimizing energy use, particularly in hybrid systems that incorporate storage. (Manjarres , et al. 2017) further developed this approach through the SUNSET model, which employs real-time forecasting and analytics to enhance system adaptability and reduce costs. Incorporating EMS and SUNSET within Dubai South’s energy planning framework supports both flexibility and resilience, especially in high-demand sectors like logistics and aviation.

Strategically, aligning Dubai South’s energy roadmap with COP28 policy directions strengthens the long-term viability and global relevance of its efforts. COP28 has emphasized accelerated decarbonization, renewable energy scaling, and increased climate finance access (Ozdemir, et al. 2023). Dubai South stands to benefit directly from the UAE’s leadership role in these global initiatives, particularly through national investments in carbon capture, smart grid modernization, and clean technology innovation. This alignment positions Dubai South not only as a local success story but also as a key contributor to the UAE’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and global net-zero commitments. Another study categorizes strategies into three tiers: Environmental Strategy, Proecological Strategy, and Green Strategy, with each level demonstrating an increasing degree of environmental commitment and complexity (Sulich and Sołoducho-Pelc 2021).

Together, these theoretical and strategic frameworks—SSM, EMS, FSAs/CSAs, and COP28 alignment—offer a comprehensive basis for building a resilient, efficient, and globally integrated renewable energy strategy for Dubai South. They ensure that energy initiatives are not only technically sound and economically feasible but also socially inclusive and future-oriented.

Figure 1.

Relationship between sustainability strategies and management approaches, adopted from Sulich, A., & Sołoducho-Pelc, L. (2021).

Figure 1.

Relationship between sustainability strategies and management approaches, adopted from Sulich, A., & Sołoducho-Pelc, L. (2021).

While many studies have addressed renewable energy in conventional urban settings, few have explored its integration within complex aerotropolis environments like Dubai South. This research fills that gap by analyzing energy needs across a multi-functional urban fabric. It also presents the Dubai South HQ Solar Project as a baseline case, offering empirical insights for scaling clean energy across the city’s districts. The roadmap developed through this study contributes not only to Dubai South’s sustainability goals but also provides a replicable framework for similar cities seeking to align infrastructure expansion with climate resilience and clean energy transitions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design and Conceptual Framework for Solar Energy Deployment in Dubai South

TheThis study adopts a case-based research design, using the Dubai South1 Headquarters (HQ) Solar Project as a representative model to inform broader renewable energy deployment strategies across the Dubai South development. Commissioned in 2020, the solar installation was monitored in 2022; a year that reflects stabilized post-pandemic operations and typical energy consumption patterns. This makes 2022 an ideal reference point for evaluating system performance, assessing operational and environmental outcomes, and supporting accurate system sizing and forecasting for future solar integration.

Dubai South1, formerly known as Dubai World Central, is a strategically planned 145-square-kilometer city centered around Al Maktoum International Airport, envisioned to become the world’s largest aviation hub. Designed as a free economic zone, Dubai South is subdivided into specialized districts for logistics, aviation, commercial activities, exhibitions (including the Dubai Airshow and Expo 2020 site), residential zones, and humanitarian operations. The city is a core component of Dubai’s 2030 vision, with ambitions to host one million residents and generate half a million jobs. Sustainability is embedded in its development blueprint, making it a suitable environment for piloting scalable clean energy solutions.

The solar project at Dubai South HQ provides a unique lens to evaluate how solar energy systems can be integrated into this multifaceted urban ecosystem. The case study supports the design of a comprehensive deployment strategy by generating insights into technical performance, environmental benefits, financial feasibility, and risk mitigation. The analysis adheres to DEWA regulations for solar integration and aligns with the city’s vision for a low-carbon, smart, and energy-resilient urban environment.

The successful deployment of solar energy in Dubai South requires a conceptual framework that integrates technical, financial, and policy considerations. As a rapidly developing aerotropolis with diverse energy needs across commercial, residential, and logistics sectors, Dubai South demands a structured, scalable approach to solar integration. This framework builds upon national and global policy momentum, especially the UAE’s leadership during COP28, which emphasized decarbonization, renewable energy scaling, and increased climate financing as key pillars of a just and inclusive energy transition (Ozdemir, et al. 2023).

The framework is grounded in three key pillars: technical feasibility, financial viability, and policy alignment. On the technical front, solar PV deployment must adapt to sector-specific load profiles and integrate with smart grid systems. Financially, the model incorporates options such as solar leasing and Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contracts, tailored to optimize cost-effectiveness for different user groups. Policy alignment is ensured through Dubai South’s adherence to national initiatives like the Dubai Clean Energy Strategy 2050 and the UAE’s Net Zero by 2050 roadmap, which together provide regulatory clarity and investment incentives for solar infrastructure.

COP28 outcomes also reinforce this strategic direction, particularly through commitments to triple global renewable capacity by 2030, double energy efficiency, and mobilize climate finance for emerging economies. These global targets support local efforts, allowing Dubai South to align its solar deployment roadmap with broader climate goals while accessing mechanisms such as concessional finance and public-private partnerships, (Rubial, et al. 2023).

The conceptual framework thus provides a blueprint for evaluating solar energy initiatives at scale. It enables the systematic assessment of system performance, return on investment, regulatory compliance, and long-term scalability.

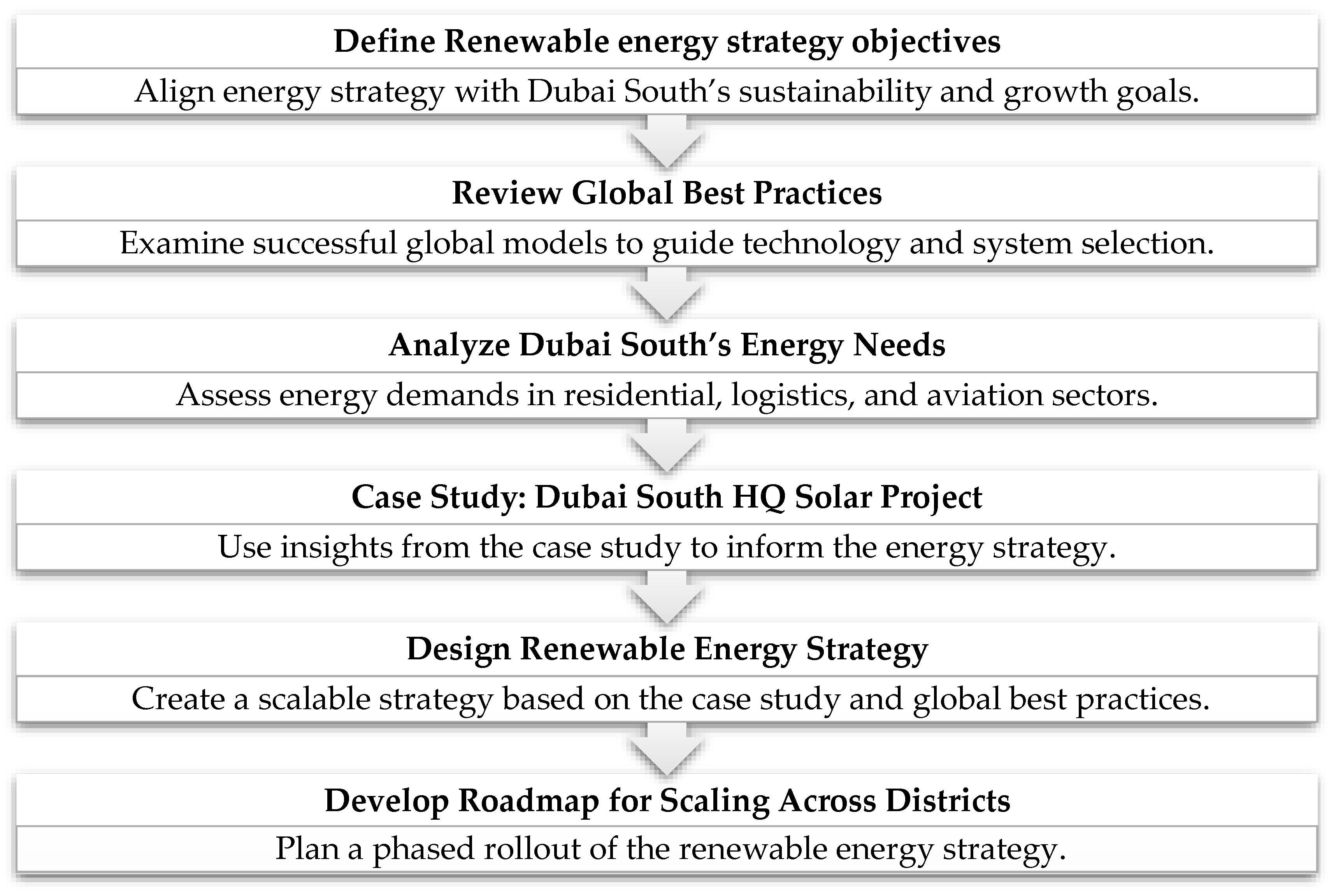

Figure 2 illustrates the core components of this framework, linking Dubai South’s sectoral energy profiles with global best practices and national policy instruments.

By anchoring the strategy in this integrated framework, the study ensures that subsequent technical analysis, financial modeling, and implementation plans are coherent, context-sensitive, and guided by both domestic priorities and international climate commitments. This approach creates a solid foundation for transitioning into the methodology section, where the framework is operationalized and evaluated in detail.

2.2. Data Sources and Collection Methods

The methodology leverages data collected from the Dubai South HQ solar plant in 2022, selected for its normalized post-pandemic operations. The data was mainly obtained from two main sources:

Meteocontrol Monitoring System: Provided hourly data (01/01/2022 - 31/12/2022) on energy generation, performance ratio, ambient/module temperatures, wind speed, solar irradiation (GHI), and inverter performance. Distribution losses were calculated as the difference between inverter output and the grid feed-in meter reading.

DEWA Consumption Records: Supplied facility electricity demand data. 2019 data served as the pre-installation baseline. 2021 data was excluded due to COVID-19 operational disruptions. 2022 data, reflecting stabilized post-pandemic operations, was the primary reference for strategy development.

These sources were selected to ensure reliable monitoring of energy generation, environmental conditions, and electricity consumption within the facility.

Data sources include:

Energy generation and environmental data collection focused on the following components,

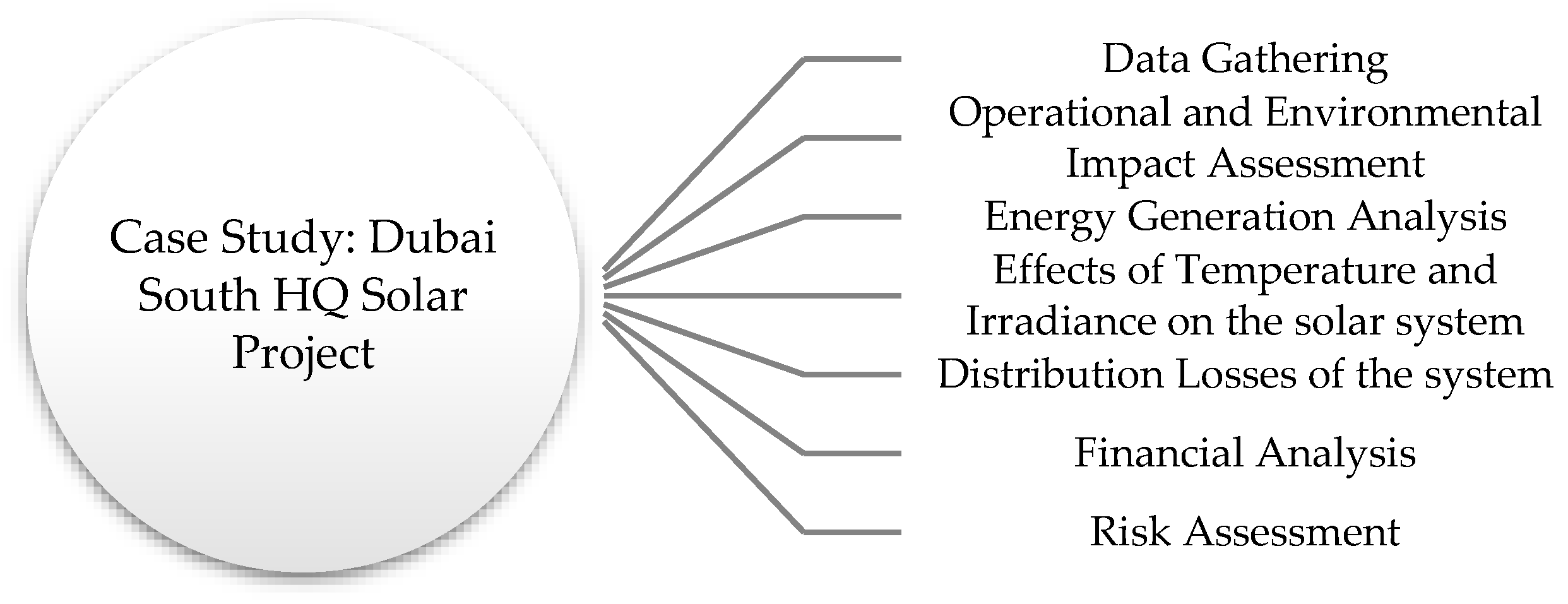

Figure 3:

Operational and Environmental Impact Assessment: Energy consumption trends, peak loads, and system output were monitored and compared against ASHRAE performance benchmarks for governmental buildings. Emission sensors and water usage trackers were used to evaluate environmental metrics such as carbon reductions and resource efficiency.

Energy Generation Analysis: Actual versus expected energy generation was analyzed to assess system reliability and alignment with projected demand. This component supports adaptive energy planning and performance optimization.

Climatic Performance Variables: Given the harsh environmental conditions in Dubai, system response to high temperatures and solar irradiance was examined. This analysis enabled design improvements for resilience and consistent output across varying weather conditions.

Distribution Losses: Energy losses between generation and delivery to the grid were measured to identify efficiency gaps and inform mitigation strategies.

Financial Evaluation: A cost-benefit analysis of multiple deployment models—including solar leasing and Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contracts—was conducted to determine economic viability and adaptability to diverse stakeholder needs across different districts (residential, logistics, and aviation).

Risk Assessment: Technical, environmental, and operational risks were identified to enhance system durability and inform contingency planning. This included evaluating potential system vulnerabilities and external threats to energy reliability.

By employing a multi-dimensional evaluation approach grounded in real-world data, the methodology enables a comprehensive understanding of the practical, economic, and strategic considerations essential for scaling solar energy systems in Dubai South and similar urban contexts.

2.3. Energy Resource Assessment (Wind and Solar Potential)

A critical step in developing a viable renewable energy strategy for Dubai South is assessing the availability and suitability of natural resources; specifically wind and solar. A comprehensive resource assessment was conducted. Given the region’s climate and urban context, both energy resources were evaluated for their technical and economic viability. This section presents the findings of resource assessments conducted in 2022, which serve to inform system design, feasibility, and energy offset projections.

2.3.1. Baseline Electricity Demand

Understanding the site's electricity consumption is essential for evaluating the scale of renewable energy capacity required.

Table 1 summarizes monthly electricity consumption data for the Dubai South Headquarters building, as recorded by the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) in 2019. These figures serve as a benchmark against which renewable generation performance, sizing, and potential offset can be evaluated.

The data was used as the baseline for sizing the system before its installation in 2020. It is worth noting that the data from 2021 was excluded since building operations had not yet returned to normal due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to irregular energy consumption that did not reflect typical usage patterns. Moreover, the data from 2022 was used as the main reference for strategy development, as it represented a stabilized period of operation post-pandemic and offered a realistic assessment of energy demand.

As shown in

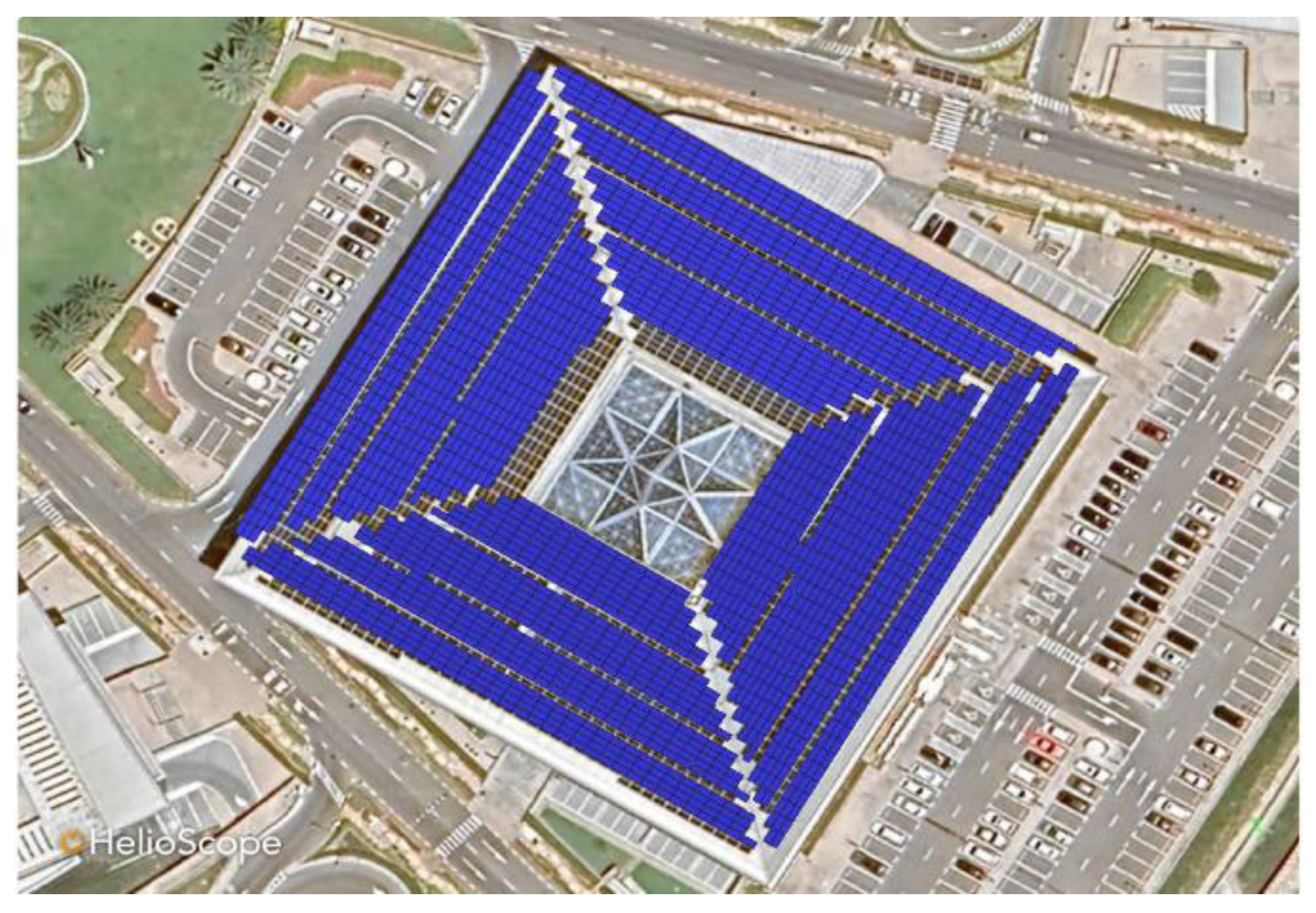

Figure 4, the data collected from the usable rooftop surface area at the Dubai South HQ facility, as modeled using Helioscope. This design supports optimal system sizing, panel orientation, and layout design based on shading constraints, panel pitch, and structural limitations.

2.3.2. Solar Energy Assessment

Given Dubai’s high solar irradiance, solar PV emerged as the primary candidate for clean energy deployment. A site-specific analysis was conducted using PVsyst software, coupled with field data from a five-sensor setup oriented at cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) and a central sensor,

Figure 4. This allowed for real-time tracking of irradiance variation by orientation and time of year. This step was essential for identifying shading obstructions, structural limitations, and orientation constraints, ensuring the system design complied with DEWA’s regulations.

The results from Helioscope provided a starting point for refining the PV system layout before moving on to detailed energy yield simulations in PVsyst.

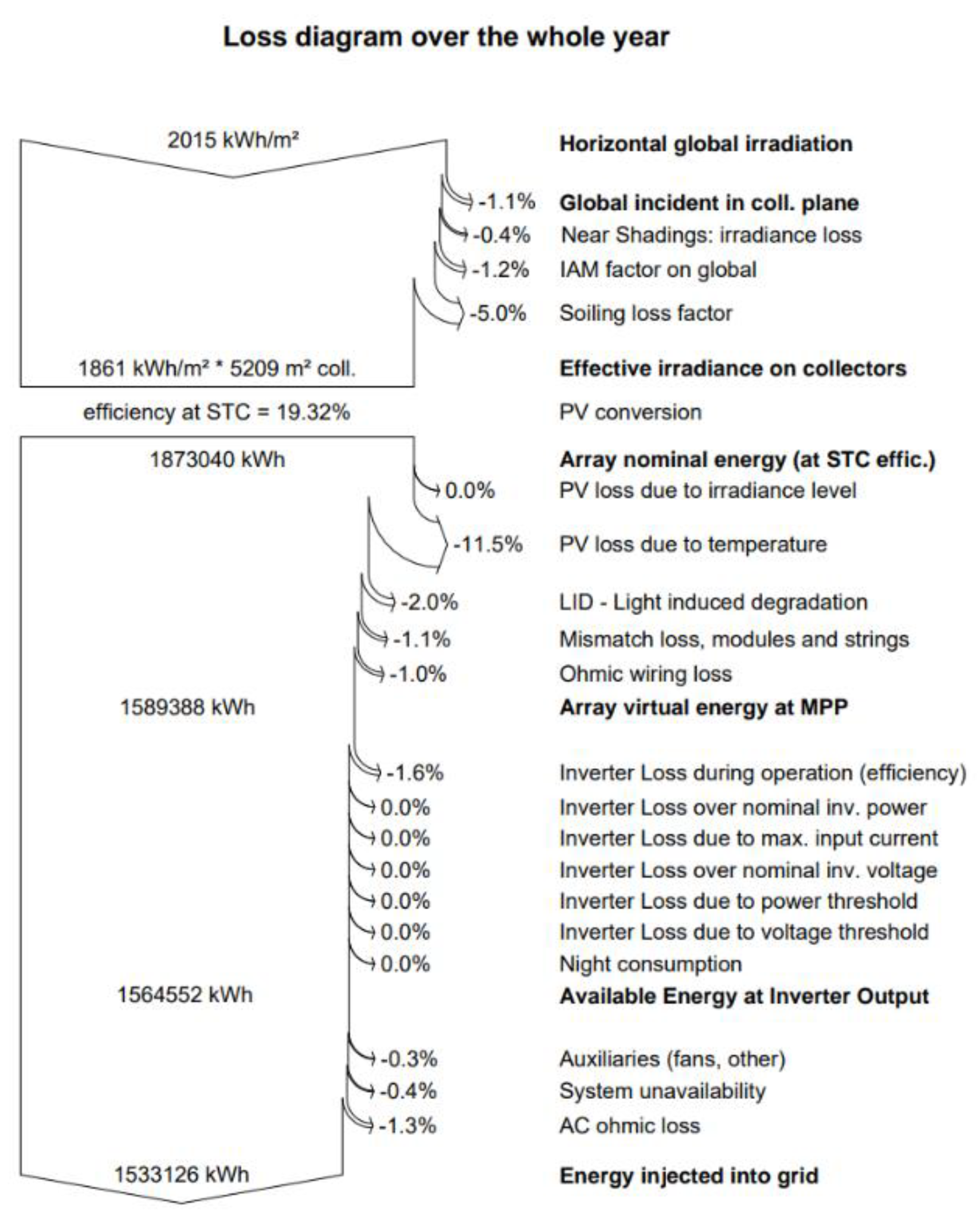

Figure 4 visually represents this assessment, illustrating how the available space was mapped and factored into the system design. Once the initial feasibility was established, PVsyst was used to simulate the system’s energy output (Mermoud & Wittmer, 2014), as shown in

Figure 5. PVsyst was chosen for its detailed analytical capabilities, allowing the integration of key factors such as irradiance, shading, temperature effects, and module performance to provide accurate energy yield estimates.

The simulation results helped fine-tune the design, optimize component selection, and ensure economic feasibility, aligning the project with DEWA’s guidelines while enhancing overall performance. Additionally, full shading analysis was performed in parallel to further estimate accurately the estimated generation.

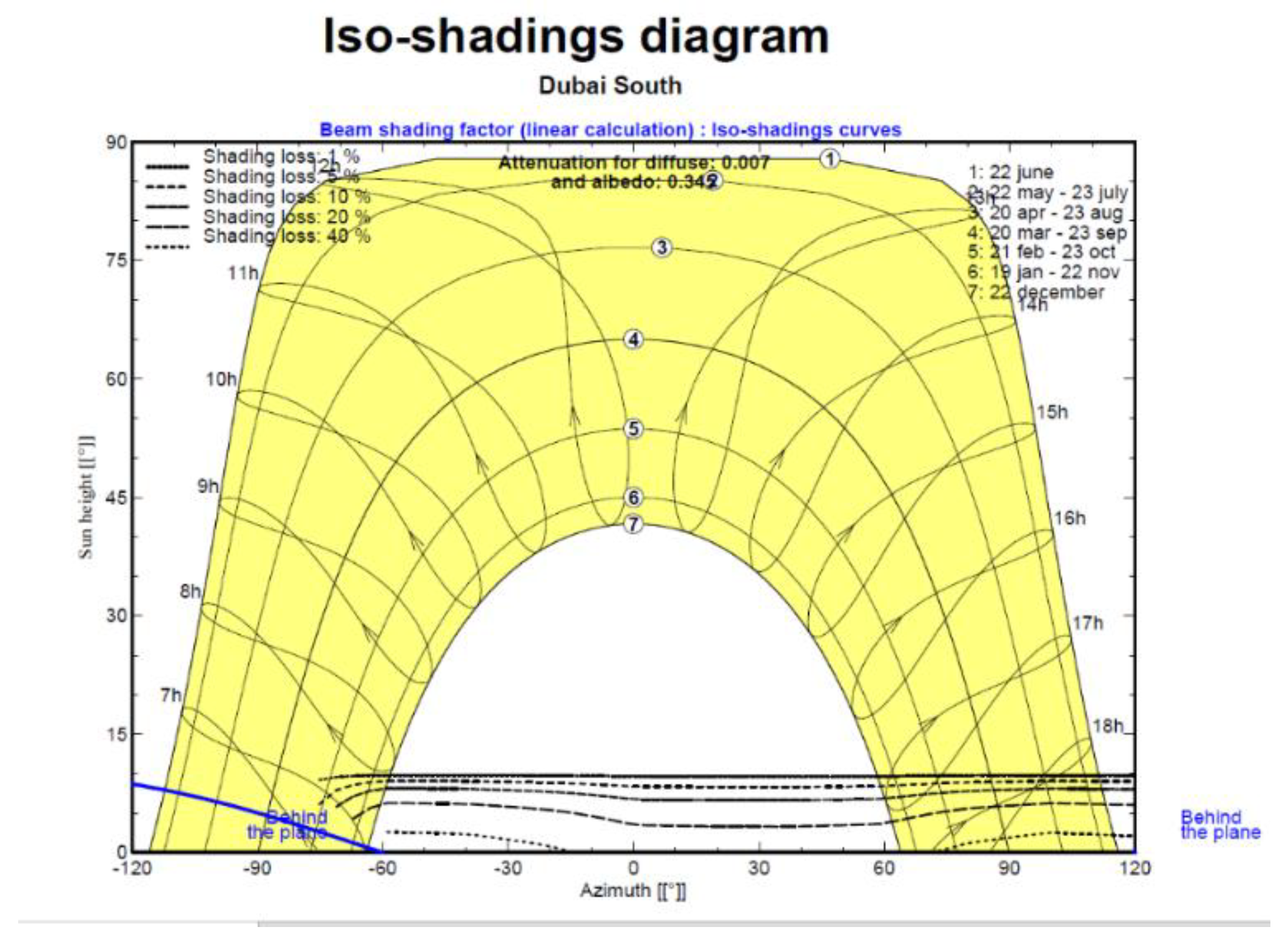

Figure 6 showcases the sun path diagram with the shading analysis of the proposed system. The Iso- shading diagram provides a year-round representation of the sun's trajectory and potential shading.

Table 2 showcases the estimated generation from the Pvsyst simulation vs the baseline in 2019 and the respective percentage of the estimated offset. The months of April and May show the highest energy generation, with outputs of 144,800 kWh and 163,600 kWh, respectively. This increase is due to the higher solar altitude and cooler temperatures during these months, resulting in longer sun exposure and improved panel efficiency, as higher temperatures typically reduce performance. Similar conditions are observed in regions like Southern Europe (e.g., Spain) and Central Asia (e.g., Kazakhstan), where springtime irradiance and moderate temperatures support strong solar performance. In contrast, Dubai South's summer months experience reduced efficiency despite high irradiance, due to higher temperatures. Offsets between March and June range from 58% to 61%, reflecting effective system performance under favorable climatic conditions.

2.3.3. Wind Energy Assessment

Although wind energy was initially considered, a year-long analysis of local wind conditions revealed limited feasibility. Wind speed data was collected using a Lufft WS501 BM: RS485-165 anemometer mounted at standard rooftop height to reflect actual deployment conditions for urban microgeneration systems.

As shown in

Table 3, the average annual wind speed was 2.23 m/s, which falls below the minimum cut-in speed for commercial wind turbines (typically 3–4 m/s). This finding renders wind energy technically unviable for Dubai South, given current turbine technology and urban wind constraints.

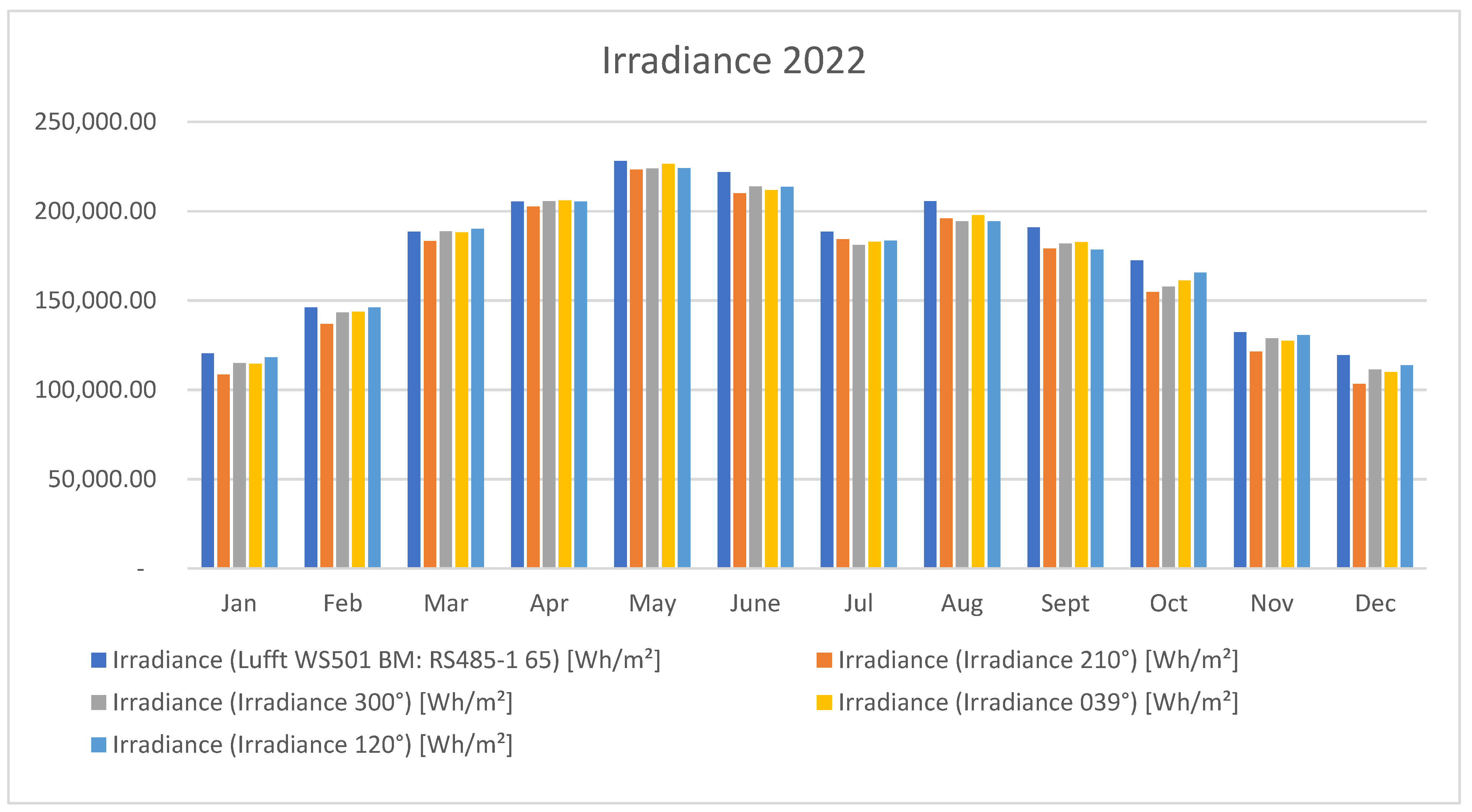

The irradiance profile for 2022,

Figure 7, reveals a consistent seasonal pattern, with peak values recorded during the summer months, particularly from May to August. A slight but unexpected drop in July's irradiance is attributed to several days of summer rainfall. In contrast, the lowest irradiance levels occurred during the winter months, November through February, due to reduced solar altitude. Directional sensor data further illustrates how the sun’s angle and position affect irradiance distribution. Notably, the Lufft WS501 BM: RS485-165 sensor, positioned at the center, recorded the highest irradiance throughout the year, highlighting the advantages of unobstructed central placement. Conversely, sensors oriented at 039° and 120° recorded the lowest values during winter, reflecting the impact of lower solar angles in the northern hemisphere.

These findings offer critical input for optimizing tilt and azimuth angles in PV system design. The assessment also reaffirms solar PV demonstrates strong technical and seasonal performance. Estimated solar offsets indicate considerable potential to reduce grid reliance, especially during high-demand summer periods. These insights inform the solar deployment strategy presented in

Section 2.4, ensuring alignment between resource availability, system design, and long-term energy planning objectives.

2.4. Solar PV system Architecture and Design Consideration

The architectural design of the solar PV system deployed at Dubai South Headquarters reflects a site-specific approach, tailored to local climatic conditions, operational constraints, and regulatory standards. Key system components, including panels, inverters, cables, mounting structures, and monitoring tools, were selected based on their performance under high-temperature conditions and long-term reliability in the region’s arid environment.

Solar panels as the first component in the PV system are very crtitical. They must be able to operate efficiently in Dubai’s climate, where temperatures frequently exceed 45°C. Since power is the product of current and voltage, any decrease in any factor will result in a lower power output, which is the case in high temperature instances. Practically, the voltage has a higher impact on the power output in comparison with the slight increase in current therefore despite having a positive coefficient of current, the efficiency of solar panels decreases with high temperatures. It is vital to have a comprehensive understanding of the coefficient of voltage, current and power prior to any decision making regarding the panel technology.

Studies show that solar irradiance levels in Dubai range from 1,384 Wh/m² to 8,888 Wh/m², making it an ideal location for solar power generation (Al Breiki, Al Hammadi and Kazim 2021). However, silicon-based PV modules efficiency declines by 0.4% to 0.5% for every degree Celsius increase in temperature ( Müller, Gambardella and Huld 2011). This means that during peak summer, when module temperatures are significantly above standard test conditions (STC), efficiency losses become unavoidable. To mitigate temperature-induced efficiency drops, various cooling strategies have been explored.

Studies have found that improving airflow around the panels, elevating their mounting structures, or integrating passive cooling techniques like aluminum heat sinks can reduce module temperatures by up to 10°C, leading to an approximate 5% increase in efficiency (Al-Naser and Al-Naser 2023). Ensuring proper heat dissipation and avoiding panel overheating is essential in optimizing performance under Dubai’s climate conditions. This study incorporates real-time temperature and energy generation data from the Meteocontrol Monitoring System to analyze the impact of high temperatures on panel performance. The findings align with climatological studies in Dubai, reinforcing the importance of designing solar installations that account for both solar potential and temperature effects to maximize system efficiency.

The solar panels are rated under standard test conditions (STC) which means all parameters are being tested under 1000W/m2 and 25 degrees Celsius which is not the case in real life projects therefore when the solar panel is exposed to high temperatures, they will experience a decrease in their efficiency and consequently causing power degradation knows as temperature-related degradation.

Table 4 presents temperature data from January to December 2022. Temperatures increased steadily through the first half of the year, peaking in July at over 41°C before declining toward winter. Monitoring these patterns helped assess potential thermal stress and the role of panel orientation in heat dissipation.

Almost all solar PV plants operate within the MPPT (maximum power point tracking) point to ensure optimum generation. The maximum power point (MPP) of a solar panel can vary with temperature. The algorithms used by MPPT optimize the solar panel's operating point to optimum power output. However, extreme temperatures can make reliable tracking difficult. Higher temperatures can increase resistive losses within solar cells and their associated circuits, known as temperature-related losses or thermal losses. The overall resistance of the electrical circuit within the solar panel increases with temperature, resulting in a decrease in electrical performance.

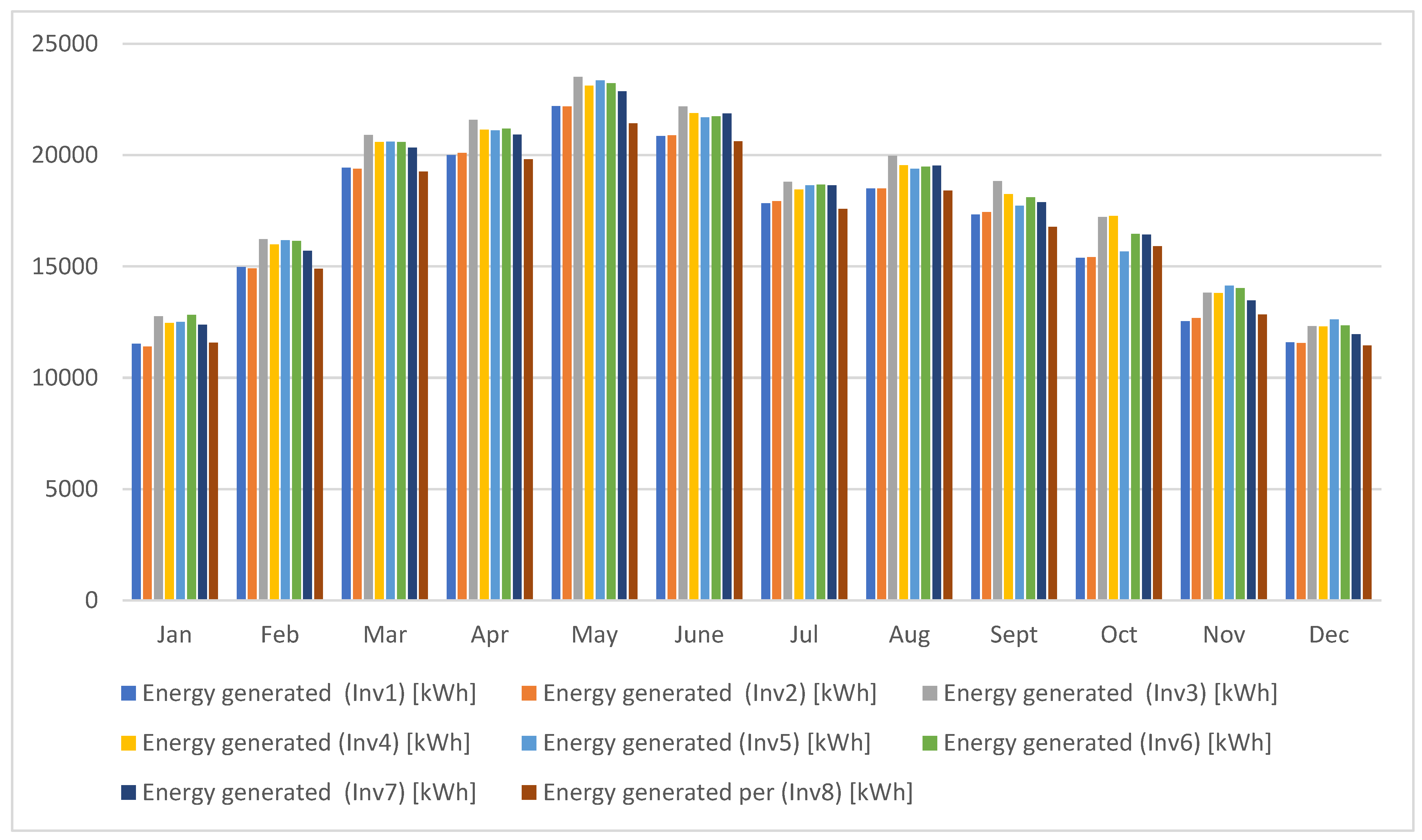

Inverter is also a component of the solar PV system. The system employs multiple inverters distributed across the PV array, enabling detailed performance tracking. Inverter-level monitoring over 12 months revealed clear seasonal patterns and inter-inverter variability. As shown in

Figure 8, energy output was highest between March and May. Inverters Inv3 and Inv5 consistently outperformed others, while Inv4 and Inv6 exhibited moderate output. A downward trend toward the end of the year reflects shorter daylight hours and reduced irradiance. These data support targeted maintenance, inverter selection for future projects, and design modifications to ensure load balancing across system strings.

Another important component to consider before any solar project is the selection of DC and AC cables. Efficient energy transmission depends on proper cable sizing and installation practices. Copper cables insulated for UV exposure were used for DC wiring, while AC cables conformed to DEWA and BS 7671 standards. Distribution losses—measured as the difference between inverter output and the utility meter reading—were monitored throughout 2022.

As shown in

Table 6, losses remained generally below 2%, though slight seasonal variation was observed. Elevated losses in summer may be attributed to cable resistance under higher temperatures and partial shading effects. Reducing conductor length, enhancing layout symmetry, and regular thermographic inspections can further reduce these inefficiencies.

The monitoring and Integration is also part of the PV system. The solar system includes a high-resolution monitoring platform integrated with the Building Management System (BMS). Using MODBUS protocol over Ethernet, the system offers 15-minute interval string-level monitoring, supported by environmental sensors for irradiance, temperature, humidity, and wind speed. Alerts are automatically issued via SMS or email, and all data are archived for a minimum of one year. This real-time oversight allows early fault detection, performance benchmarking, and operational optimization, all of which are essential in commercial PV deployment.

Mounting structures were engineered to comply with Dubai Municipality guidelines and were constructed from galvanized aluminum and stainless steel to withstand the region’s environmental stressors. Landscape orientation was chosen for panel installation to reduce dust accumulation and facilitate cleaning. The design ensures a 25-year operational life, factoring in static load resistance, seismic compliance, and aerodynamic stress. Panels are elevated a minimum of 90 mm above the rooftop to promote convective cooling, and mounting rails are integrated with waterproofing systems to protect building infrastructure.

Dust accumulation is a major performance constraint in desert climates. To address this, robotic cleaners were installed on dedicated aluminum rails. These robots use microfiber brushes and controlled wet-cleaning mechanisms to maintain panel surface clarity. Cleaning operations are automated and scheduled in alignment with weather data to reduce water usage and energy losses. The system includes a five-year warranty and complies with warranty conditions of the PV modules.

2.5. Financial Evaluation of Deployment Models

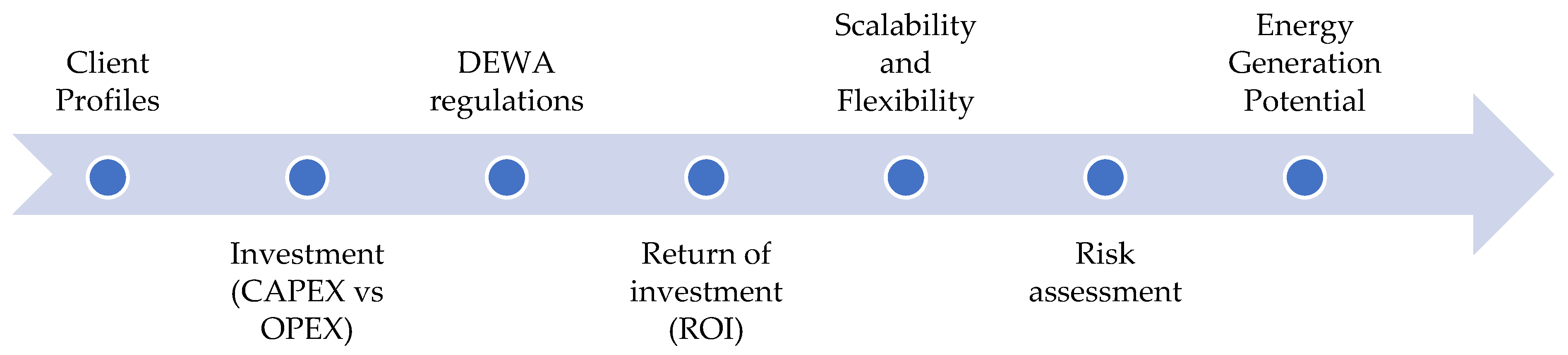

Financing solar PV systems remains a critical consideration due to their high upfront capital expenditure (CAPEX) and expertise required for installation and maintenance. In the context of Dubai South, tailored financial models are necessary to accommodate diverse operational requirements across logistics, aviation, commercial, and residential sectors.

Figure 9 outlines the key parameters used in developing these financial models, including client energy needs, risk tolerance, return on investment expectations, and regulatory incentives. A core distinction is made between models emphasizing capital ownership (CAPEX) and those leveraging operational expenditures (OPEX), allowing for flexible adoption based on the financial profile and strategic priorities of each client.

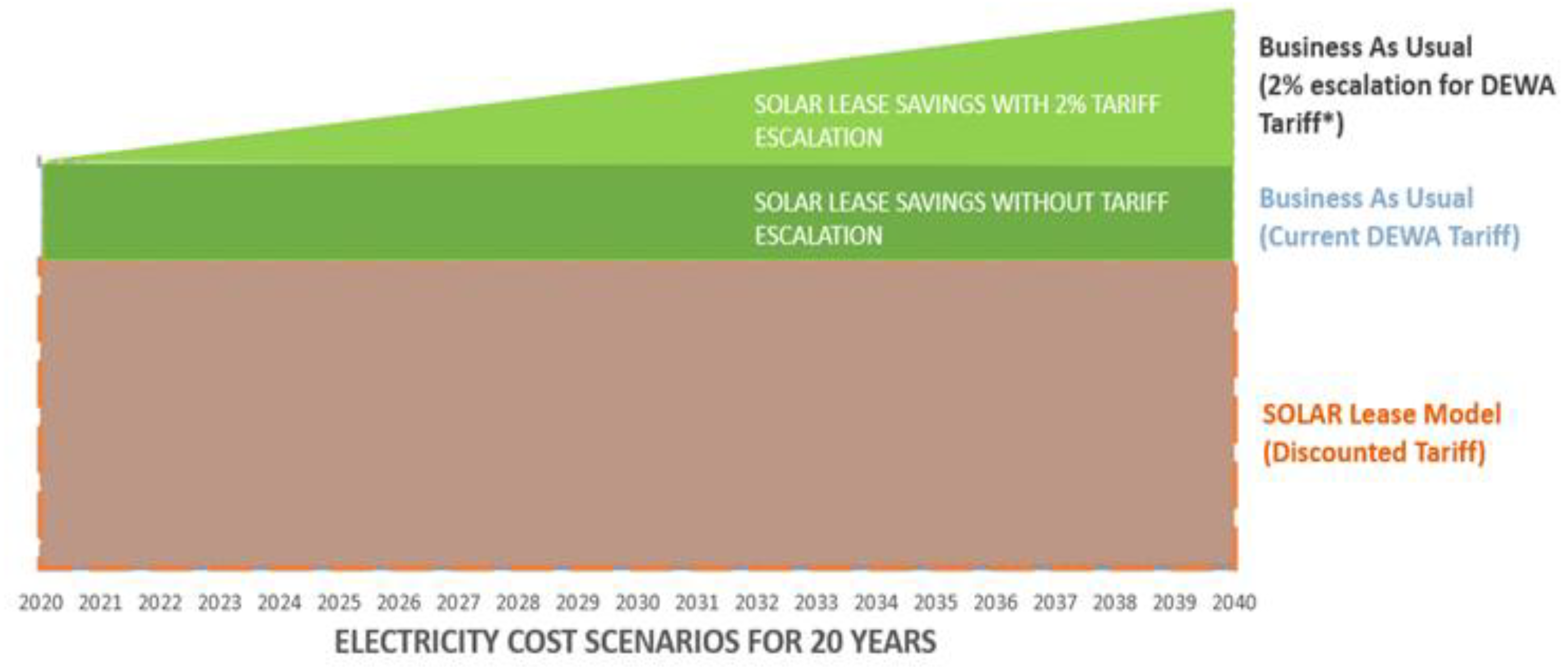

The Solar Lease Model allows clients to access solar energy without incurring upfront investment. Clients pay only for the electricity generated at a pre-agreed tariff, making this model attractive to businesses seeking to preserve capital for core operations. The lease includes maintenance services and is customized based on energy demand and site specifications.

Figure 10 compares three tariff scenarios, two based on projected DEWA electricity price trends and one under a solar lease, demonstrating the cumulative cost savings and tariff stability that leasing offers over a 20-year horizon.

In contrast, the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) Model is suitable for clients with sufficient financial resources who prefer full ownership. The client finances the system and retains all generated power, benefiting from long-term savings and energy independence. This model is most aligned with the priorities of larger institutions or aviation-sector stakeholders aiming for asset control and cost reduction over time.

A comparative analysis reveals that the Solar Lease Model is particularly beneficial for logistics clients due to its minimal upfront cost and cash flow flexibility. Meanwhile, the EPC Model aligns with aviation or government clients seeking to reduce long-term energy costs through infrastructure ownership. This dual-model approach allows Dubai South to accommodate varied stakeholder needs while advancing broader renewable energy adoption.

2.6. Operational and Environmental Performance Indicators

2.6.1. Performance Ratio (PR) Analysis

The performance ratio (PR) is a critical metric that evaluates the efficiency of a solar power plant by comparing actual output to theoretical output under standard test conditions. It reflects system losses and helps track operational consistency over time. PR is calculated using the following equation:

Where:

PRACT : Actual Performance Ratio measured in a defined time period (%)

E: Energy produced (kWh)

GTI: Global Tilted Irradiance (kWh / m2)

A: Total PV module area

Mf: Module efficiency at STC (%)

TC: Temperature coefficient

Performance Ratio provides information on a solar system's operational health. When the PR number is around 100%, it means that the system is operating at about full capacity under irradiation circumstances. However, in reality, PR values for PV systems frequently range from 75% to 90% because of several losses, including shading, system degradation, inverter losses, and temperature losses.

Table 7 reports annual PR values for 2020 to 2022, with averages consistently above 81%. This performance is within the industry’s expected range of 75–90%, indicating reliable operation. A slight increase from 81.69% (2020) to 81.97% (2021) suggests marginal operational improvements, while the minor dip to 81.83% in 2022 is within normal variation and may reflect external conditions such as weather or maintenance activities.

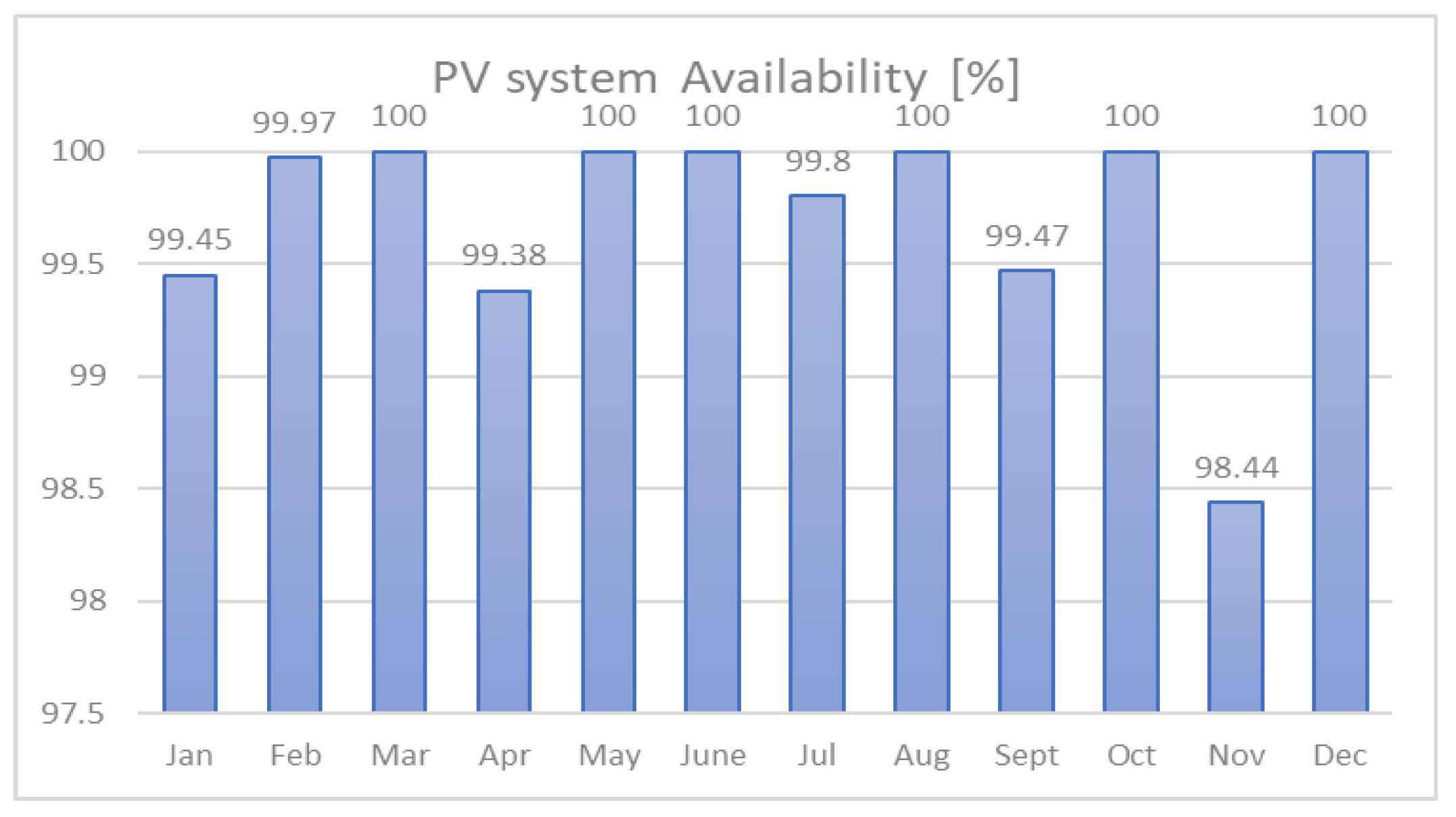

2.6.2. System Availability

System availability is another critical performance indicator, reflecting the percentage of time the system was fully operational. The Dubai South solar system maintained exceptionally high availability throughout 2022, reaching 100% in several months, including March, May, June, August, October, and December. The lowest availability (98.44%) was recorded in November due to a scheduled shutdown by DEWA.

High availability underscores effective preventive maintenance and operational planning. Even marginal dips below 100% can lead to significant energy losses over time, especially in large-scale systems. Therefore, maintaining near-perfect availability is essential for achieving energy and financial targets.

Figure 11.

PV system availability 2022 (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Figure 11.

PV system availability 2022 (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

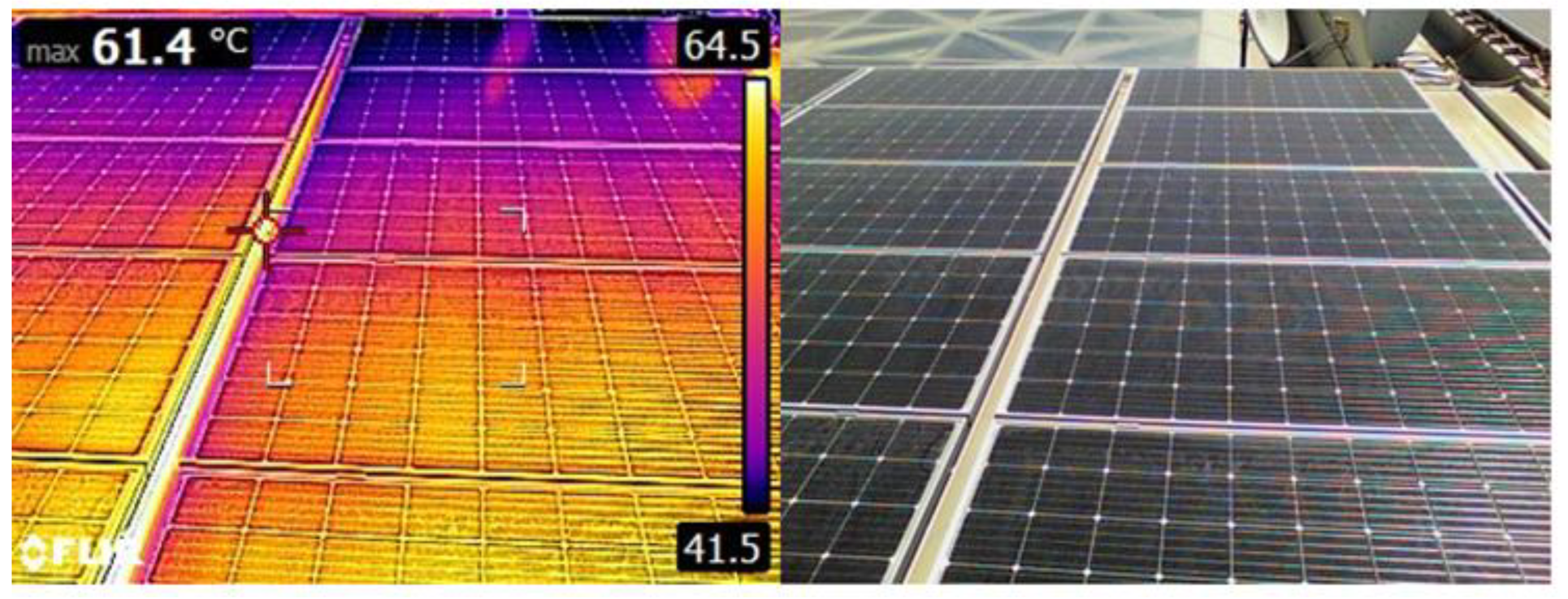

2.6.3. Thermography Testing

Thermographic imaging, as shown in

Figure 12, is employed as a non-invasive diagnostic tool to identify hotspots caused by cell degradation, shading, connection faults, or soiling. These anomalies may lead to localized heating, potentially posing fire risks or reducing output. Periodic thermography enables early detection and correction of these faults, ensuring system safety and sustained energy yield.

By mapping surface temperatures, thermography facilitates targeted maintenance, reduces downtime, and extends system lifespan. Over time, this technique also helps track degradation patterns and verify the integrity of system components post-installation or post-maintenance.

2.6.4. Generation Monitoring

It is important to continuously monitor the performance of the solar plant by comparing the actual generation to the previously estimated generation in the PVsyst simulation. The comparison shall be carried on throughout the lifetime of the project incorporating the annual degradation percentage. In practice the first year has a 2% degradation then from the second year onwards the degradation ranges from 0.6-0.7%. This is as per the manufacturer datasheets. However, the actual data has recorded a less percentage in terms of degradation which means the plant is being operated and maintained against the highest industry and best engineering practices.

2.7. Environmental Impact Aassessment

A core component of the solar energy deployment strategy in Dubai South is its contribution to environmental sustainability, measured through multiple performance indicators. These include reductions in energy use intensity (EUI), water consumption associated with system cleaning, and carbon emissions offset by solar electricity generation.

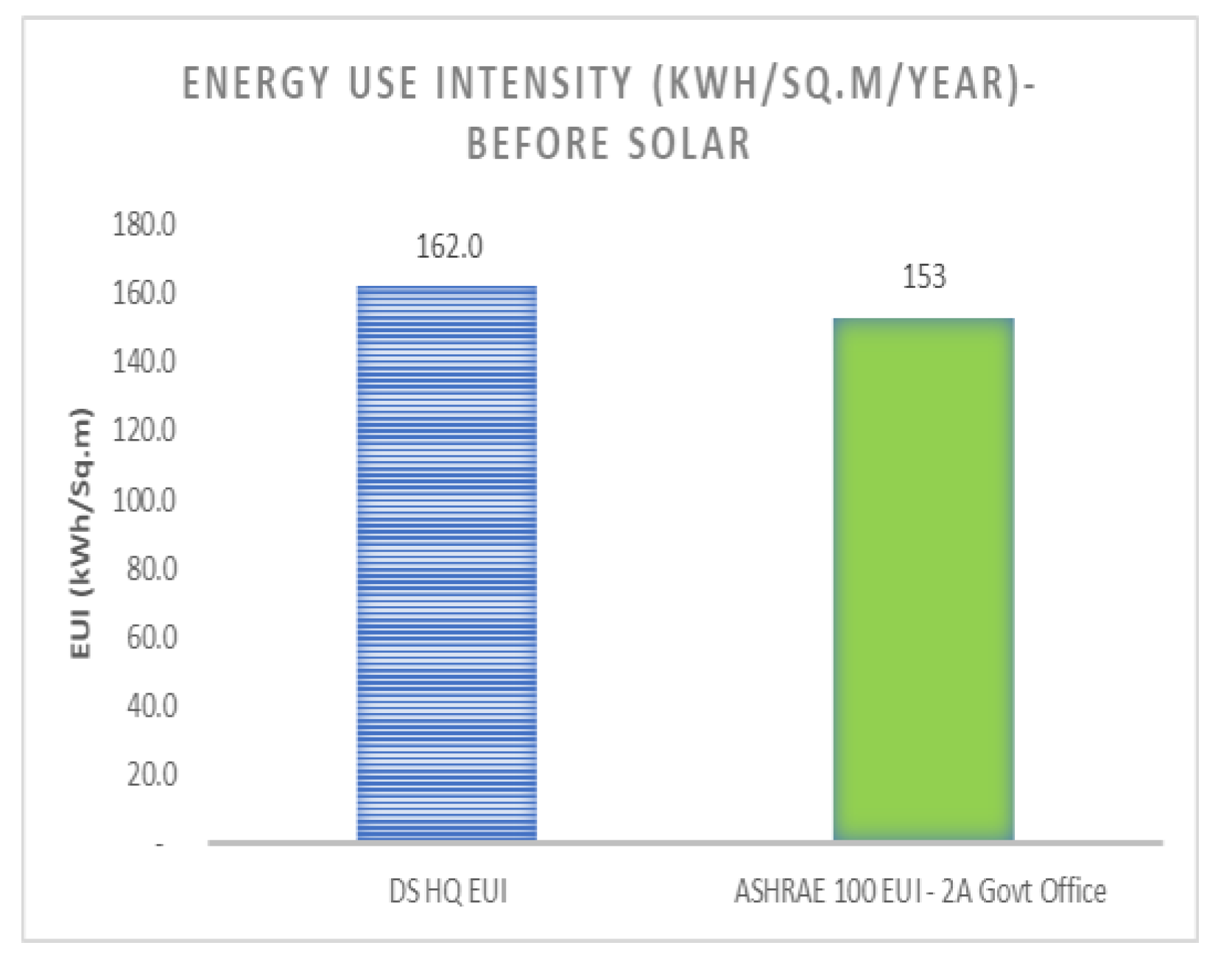

The Energy Use Intensity (EUI) metric is used to benchmark the energy performance of the Dubai South Headquarters building. EUI is defined as the total energy consumed per square meter per year and is compared to international standards such as ASHRAE for government buildings. In 2022, the building's actual EUI was 162 kWh/m²/year, exceeding the ASHRAE benchmark of 153 kWh/m²/year, indicating above-average energy consumption.

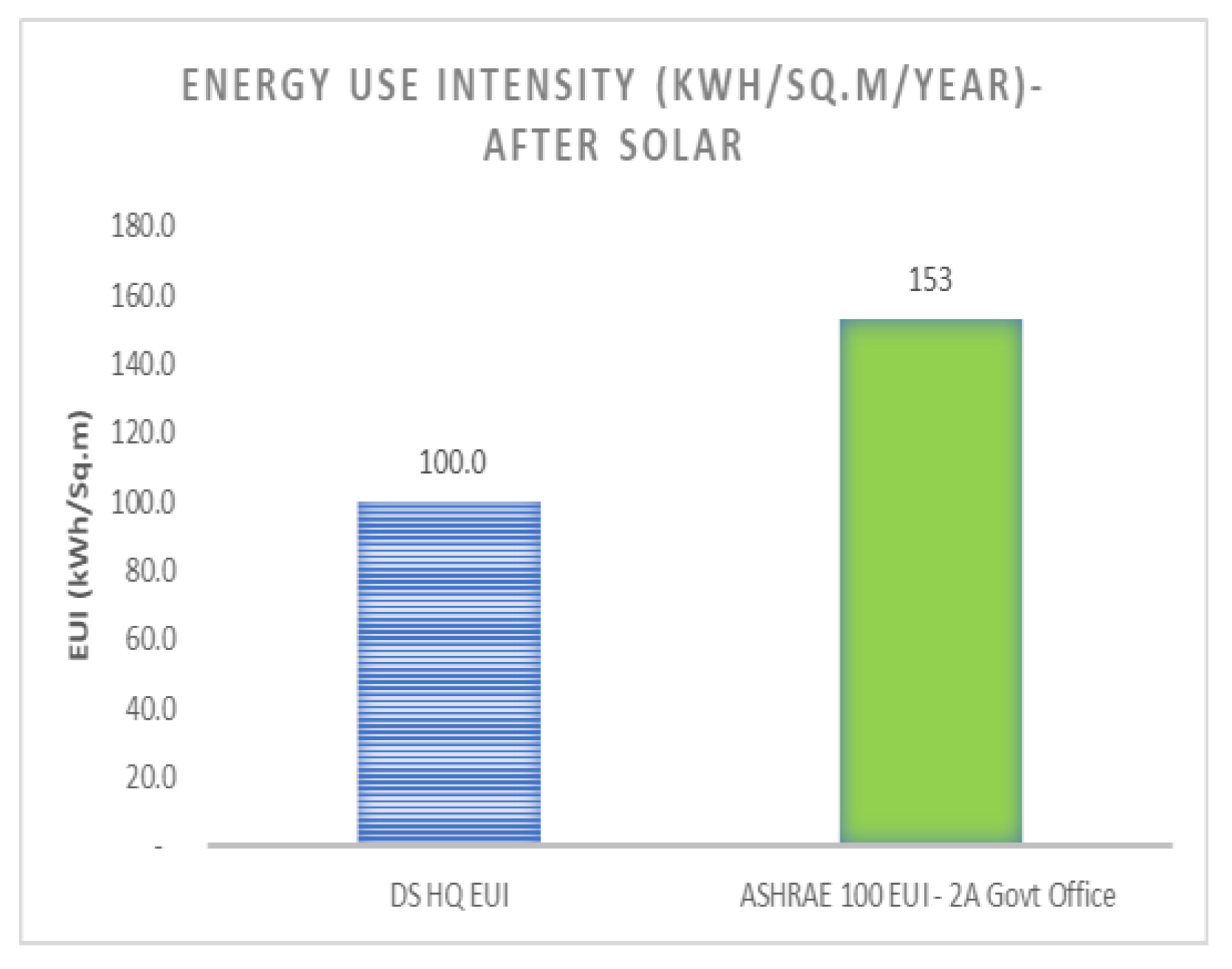

Following the installation of a 1 MWp rooftop solar PV system, the EUI dropped to 100 kWh/m²/year—a 38% improvement in energy performance. This substantial reduction illustrates the system’s effectiveness in offsetting grid electricity demand and highlights the role of on-site renewable energy in enhancing building-level efficiency.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present EUI values before and after the solar system was commissioned

The environmental impact of solar panel cleaning was also assessed in terms of water consumption. In arid regions like Dubai, water conservation is critical. The wet-cleaning process adopted at Dubai South HQ uses approximately 0.5 liters of water per panel per cleaning cycle. This value aligns with industry best practices for minimal water use while ensuring optimal panel performance. Continuous monitoring of cleaning operations ensures that resource use is efficient and environmentally responsible.

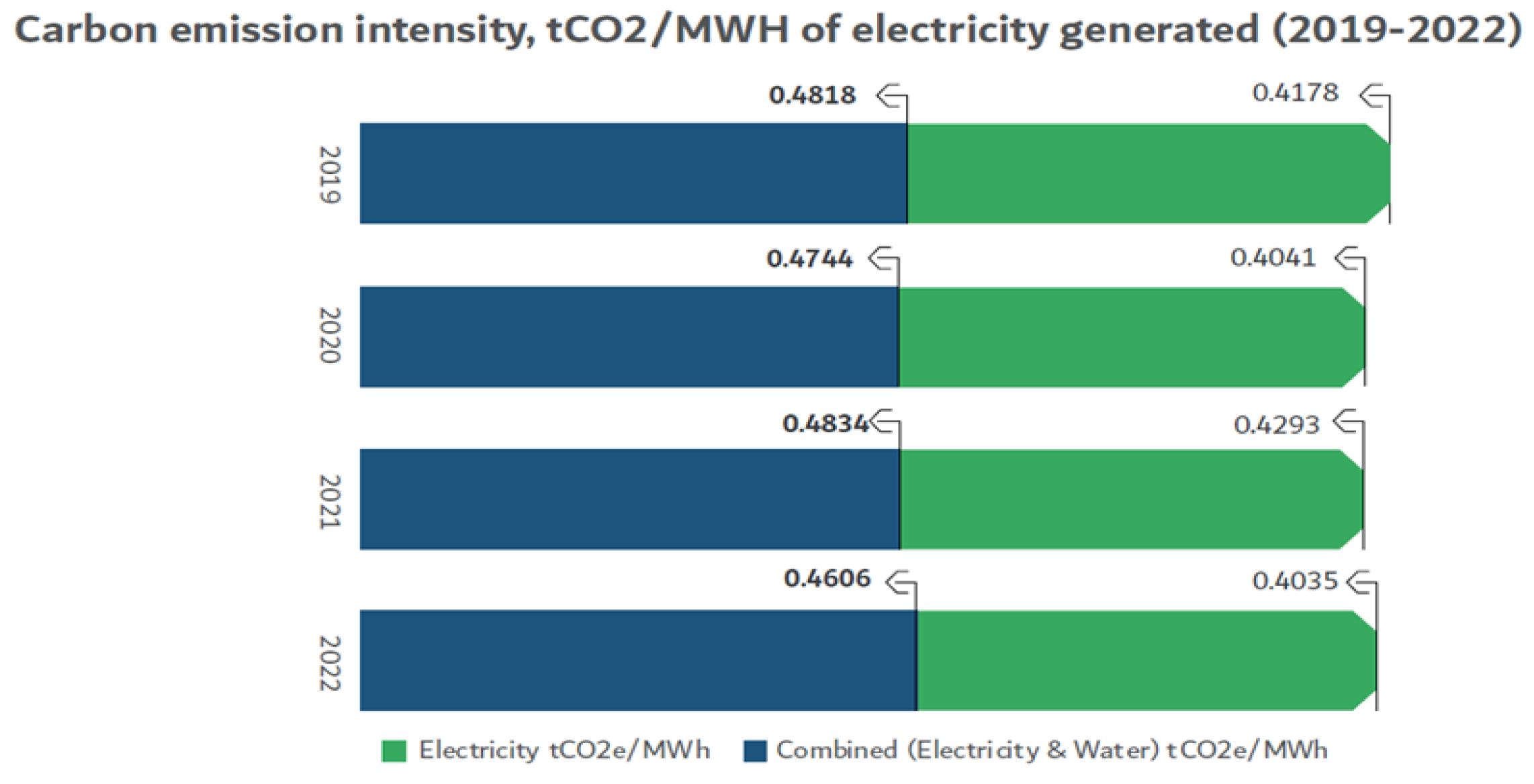

In terms of carbon reduction, the contribution of solar energy was quantified using DEWA’s carbon emission intensity benchmarks for the electricity grid.

Figure 15 illustrates the annual carbon emission intensity between 2019 and 2022. In 2020, the solar PV system generated 1,448,416 kWh, offsetting 585.30 metric tons of CO₂ at an intensity of 0.4041 tCO₂/MWh. In 2021, increased generation (1,688,672 kWh) and a slightly higher intensity (0.4293 tCO₂/MWh) resulted in an offset of 724.95 metric tons of CO₂. In 2022, generation reached 1,657,568 kWh, with an offset of 668.83 metric tons based on an intensity of 0.4035 tCO₂/MWh. These figures confirm the plant's substantial role in decarbonizing Dubai South’s energy portfolio.

2.8. Regulatory and Compliance Considerations

Given the strategic location of Dubai South adjacent to Al Maktoum International Airport, solar energy projects must comply with a wide array of regulatory requirements spanning aviation safety, electrical standards, and civil defense protocols. Projects located on or near airside zones require explicit approvals from aviation authorities to ensure that construction, operation, and maintenance activities do not interfere with airport operations.

All electrical works must comply with Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) regulations, specifically the Shams Dubai initiative for solar energy integration. Only DEWA-certified professionals are permitted to carry out design, installation, commissioning, and testing of solar PV systems. In addition to DEWA, key regulatory bodies involved include the Dubai Municipality, Trakhees, Dubai South Land Planning Department, Dubai Civil Aviation Authority, RTA, and the Dubai Civil Defense.

The remote DC disconnect requirement imposed by Dubai Civil Defense must be followed. Where DC power enters a building, a shunt trip system connected to a manual call point must allow emergency personnel to isolate the system externally. Alternatively, in cases where remote disconnects are infeasible, a fire-rated cable tray (minimum 30-minute rating) must be used to house DC cables up to the inverter, without any intermediate connectors or joints.

Additional requirement include adherence to UAE Fire & Life Safety Code of Practice, Code of Construction Safety by Dubai Municipality, and National and international standards for solar installation, including IEC and BS norms. Compliance with these multidisciplinary regulations is crucial to ensuring technical integrity, operational safety, and legal authorization across all phases of the project lifecycle.

2.9. Risk Management Plan

A proactive and structured risk management approach was implemented to identify, assess, and mitigate potential risks associated with the planning and operation of the solar PV system at Dubai South. Risks were categorized across five primary domains: technical, environmental, financial, regulatory, and operational.

Table 8 presents the identified risks, ranging from equipment failure and environmental extremes to regulatory delays and financial uncertainties. Each risk is described with clarity, ensuring comprehensive visibility into potential vulnerabilities that could affect project execution or long-term performance.

Table 9 offers a risk assessment matrix that evaluates each identified risk in terms of its probability and impact. High-impact risks—such as inverter failure or delayed permits—were prioritized for mitigation planning. The matrix enables stakeholders to focus resources effectively on the most critical issues.

Table 10 outlines response strategies for each risk. For examples, Regular thermographic inspections and scheduled maintenance to address equipment failures, Insurance mechanisms to hedge against financial and environmental risks, and regulatory pre-engagement to minimize permitting delays.

Table 11 defines roles and responsibilities across the project team, ensuring clear accountability for risk ownership, monitoring, and resolution. This governance framework is essential for aligning team actions with project objectives and institutional risk tolerance.

Altogether, this risk management framework enhances project resilience, supports compliance, and ensures that Dubai South’s solar energy deployment proceeds securely, efficiently, and sustainably.

3. Results

The implementation of renewable energy strategies across Dubai South’s diverse districts requires a context-sensitive approach. Each district—Aviation, Logistics, and Residential—presents distinct energy profiles, regulatory environments, and operational demands. The results of the strategic roadmap development process are presented in three parts: district-level integration, financial and operational analysis, and environmental performance outcomes.

3.1. District-Level Integration Roadmaps (Aviation, Logistics, Residential)

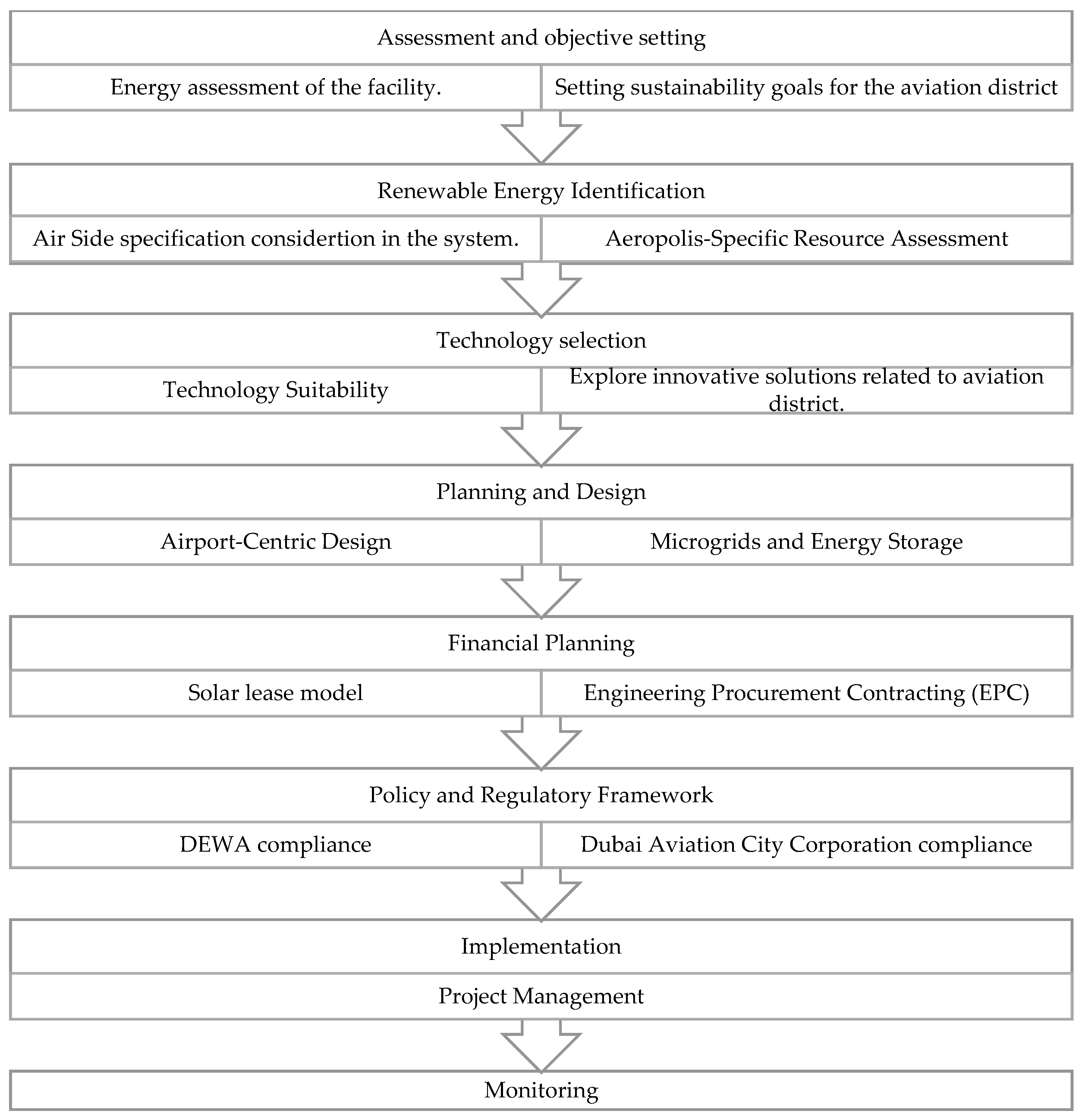

Aviation District. The renewable energy roadmap for Dubai South’s Aviation District follows a phased approach, beginning with a detailed energy audit aligned with airport sustainability goals. As illustrated in

Figure 16, the roadmap prioritizes seamless integration with existing aviation infrastructure while maintaining compliance with regulatory bodies such as DEWA and the Dubai Aviation City Corporation.

Given the high reliability and power quality requirements in aviation, the strategy emphasizes technologies like smart grids and real-time monitoring systems. Financial planning considers solar leasing as a preferred model to ensure rapid deployment without compromising capital liquidity. Careful scheduling and execution are emphasized to minimize operational disruptions in critical airport functions.

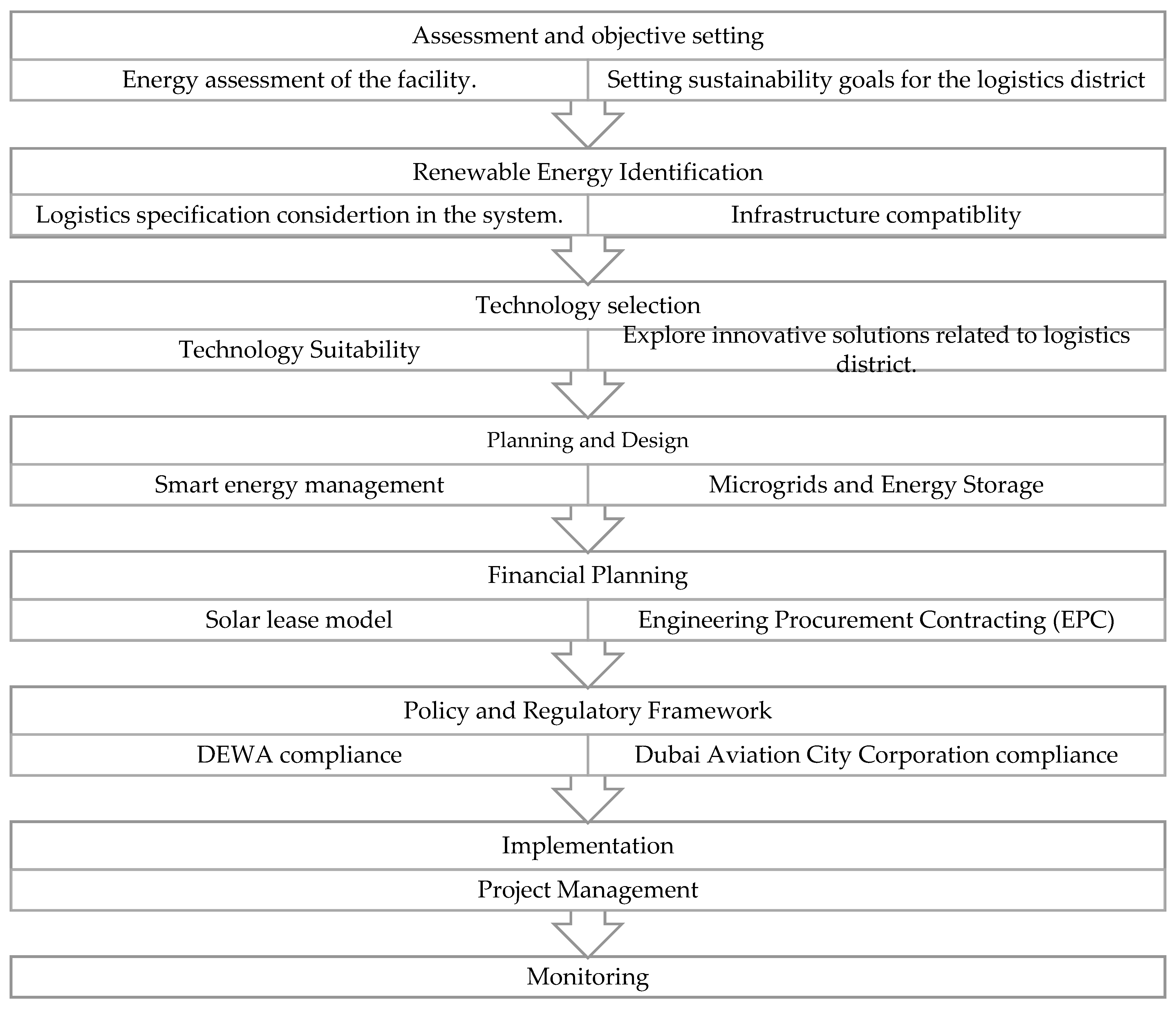

Figure 17, begins with a baseline energy needs assessment to align renewable integration with supply chain continuity and warehousing operations. The strategy introduces distributed energy systems such as microgrids and battery storage, which enhance resilience against grid instability. Integration with intelligent energy management platforms ensures load balancing and energy efficiency. Financing models are selected based on facility type and usage intensity, with solar leasing and EPC contracts tailored to meet varying client needs. Regulatory compliance with DEWA and aviation authority standards remains a core requirement throughout all deployment phases.

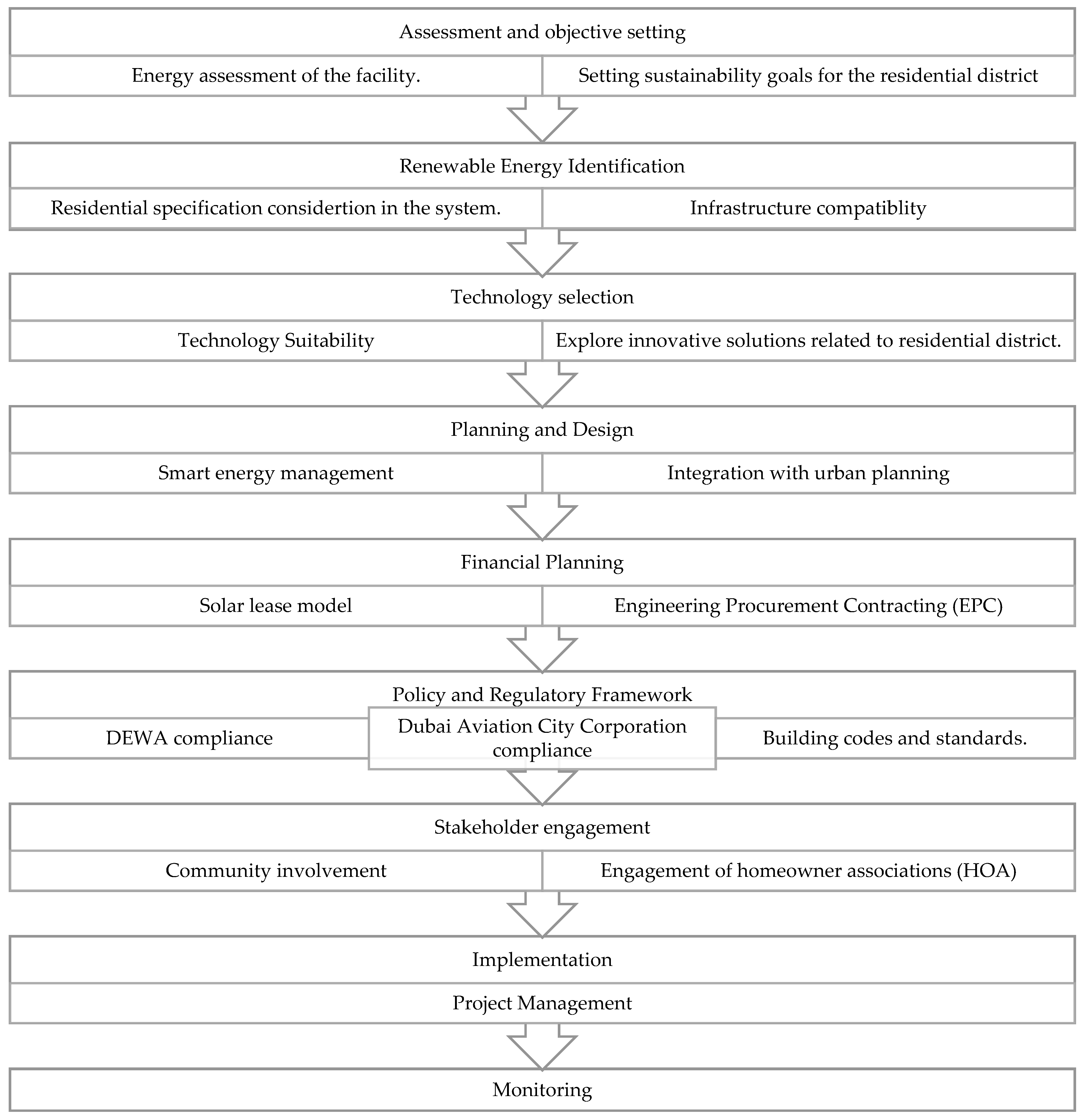

Residential District. The residential district roadmap, depicted in

Figure 18, focuses on building-level energy audits and neighborhood-scale integration planning. Smart energy management systems are embedded within the urban master plan, enabling demand-side optimization and occupant engagement. Technology selection emphasizes rooftop solar, smart meters, and modular storage systems compatible with housing infrastructure. Financing options balance cost-effectiveness with homeowner participation, exploring both EPC and lease-based frameworks. Regulatory alignment with Dubai Municipality building codes and DEWA grid standards ensures legal compliance and safety.

Across all three districts, the roadmap emphasizes phased planning, compatibility with existing infrastructure, and stakeholder-specific financing models. Monitoring, verification, and iterative improvement cycles are embedded into the strategy to ensure long-term effectiveness and alignment with Dubai South’s sustainability commitments.

3.2. Financial Viability and Operational Impact

The financial assessment confirms that both solar leasing and EPC models offer viable pathways to expand renewable energy within Dubai South. Solar leases, with minimal upfront costs, are particularly attractive for logistics clients seeking flexible operational expenditure models. EPC frameworks, by contrast, appeal to aviation or institutional stakeholders pursuing long-term energy independence through asset ownership.

From an operational perspective, energy performance improvements are measurable across all sectors. In the Dubai South HQ case study, solar deployment contributed to a 38% reduction in energy use intensity and improved annual performance ratios above 81%. System availability remained above 98%, even with scheduled maintenance events, highlighting robust operational planning. Smart energy systems and thermographic diagnostics contributed to rapid issue detection and reduced downtime, supporting continuous, high-efficiency operation.

3.3. Environmental Outcomes and Risk Mitigation

The integration of solar systems has led to measurable environmental benefits, including significant reductions in grid electricity consumption, carbon emissions, and water use for panel cleaning. Between 2020 and 2022, Dubai South’s solar plant offset over 1,978 metric tons of CO₂. Water consumption for cleaning was optimized through robotic systems, maintaining performance while minimizing waste.

From a risk perspective, district-specific risk assessments (detailed in

Section 2.7) identified and mitigated potential vulnerabilities, including equipment failure, regulatory changes, and financial exposure. Response strategies included regular maintenance, insurance, and remote monitoring capabilities. Assigning risk ownership through a structured framework (

Table 11 in

Section 2.7) has further enhanced accountability and resilience.

The results confirm that a district-specific, phased deployment model—supported by tailored financing, integrated technology, and rigorous compliance planning—is both feasible and effective. The strategic roadmaps developed for aviation, logistics, and residential districts offer a scalable framework for other aerotropolis developments seeking to integrate renewable energy while meeting operational, environmental, and financial goals.

4. Discussion: Contextualizing the Results within Dubai’s Renewable Energy Goals

This section contextualizes the findings within the broader context of Dubai’s renewable energy ambitions, highlighting their implications for large-scale solar energy deployment in urban, multi-sector environments. With the Dubai Clean Energy Strategy 2050 and Net Zero by 2050 as guiding frameworks, Dubai has committed to sourcing 75% of its energy from renewables by mid-century. The Dubai South HQ Solar Project represents a tangible step toward meeting these objectives, particularly in light of the city’s global commitments underscored during COP28.

The findings align closely with the conceptual framework introduced earlier, integrating technical performance, financial viability, and regulatory alignment. This structured approach allowed for precise evaluation of solar PV feasibility across diverse urban typologies. Notably, solar system performance in Dubai South exceeded key benchmarks, achieving a 38% improvement in energy use intensity and consistently high availability, which demonstrates both technological reliability and system resilience.

Moreover, the solar resource assessment, particularly the shading and irradiance analysis, confirmed optimal siting and design decisions based on Dubai’s high solar potential. Financially, the tailored application of solar lease and EPC models illustrates how stakeholder-specific approaches can reduce capital barriers, encourage adoption, and deliver long-term value. These models reflect Dubai’s broader strategy of enabling clean energy access through flexible financing, supporting both private and public-sector investment.

From a policy perspective, the outcomes reinforce Dubai’s proactive climate stance and highlight how regulatory compliance (with DEWA, Dubai Municipality, and Civil Aviation guidelines) can coexist with innovation in infrastructure. The integration strategy also anticipates future scalability and grid resilience, proposing pathways for sector-specific expansion and the eventual inclusion of energy storage systems and AI-driven energy management tools

In regards to implications and future considerations, the structured approach developed in this study While the results confirm the feasibility and effectiveness of solar energy integration in Dubai South, several areas require ongoing attention. Long-term system performance, climate adaptation, and storage integration remain critical to ensuring consistent energy availability and decarbonization across all districts. In this regard, the proposed roadmap offers not only immediate impact but also long-term adaptability for evolving energy demands and policy shifts.

5. Validating Solar Energy Integration: The Sakany Case Study

To validate the methodology and assess its adaptability across varying use cases, the Sakany Solar Plant in Dubai South’s Logistics District was analyzed as a comparative case study. Unlike the HQ project, which represents a commercial office environment, Sakany is a high-density residential labor camp with continuous energy demands for cooling, lighting, and utilities.

Commissioned in January 2023, Sakany generated over 361 MWh of clean energy within its first operational year, offsetting 46% of the landlord’s grid electricity consumption and avoiding over 159 metric tons of CO₂ emissions. Remarkably, the system surpassed its initial target of a 35% energy offset within the first six months, reaching 42%. These outcomes not only validate the accuracy of the design and planning methodology but also confirm the robustness of the modeling framework across diverse operational contexts.

The Sakany case affirms that the strategy is not confined to office-based installations but is scalable to residential and potentially industrial applications. The consistency between projected and actual energy generation further reinforces confidence in the framework’s predictive capabilities, supporting its broader deployment throughout Dubai South and similar urban developments.

6. Conclusion

The Renewable Energy Integration Strategy for Dubai South provides a practical and structured approach to embedding renewable energy within urban development. By integrating solar energy solutions across residential, logistics, and aviation sectors, this strategy aligns with Dubai’s broader sustainability goals while offering a replicable model for other urban districts. The Dubai South HQ Solar Project has played a critical role in shaping this strategy, offering real-world insights into energy generation, cost savings, and carbon reduction. The project’s ability to achieve an annual clean energy offset of nearly 50% and reduce 668 metric tons of CO₂ emissions demonstrates both its financial feasibility and environmental impact.

Further validation through the Sakany Solar Plant highlights the strategy’s adaptability, with the residential project achieving a 46% reduction in grid reliance and exceeding its projected performance. These findings confirm that solar integration can be effectively scaled across commercial, logistics, and residential sectors when guided by a structured, data-informed methodology.

To advance this success, future efforts should prioritize enhanced energy storage integration, grid stability, and predictive maintenance using AI and IoT technologies. Policy enhancements, such as incentive mechanisms and streamlined permitting, will be critical in driving broader private-sector engagement. Continuous monitoring, performance optimization, and stakeholder training will also be essential in maintaining efficiency and aligning with evolving regulatory and climate targets.

In summary, this study offers a validated, flexible, and forward-looking blueprint for solar energy integration in emerging aerotropolis cities. By combining rigorous technical planning with financial and regulatory foresight, Dubai South is positioned as a global exemplar in sustainable urban development, paving the way toward cleaner, more resilient, and energy-independent cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and D.W.; methodology, O.M; investigation, O.M.; resources, O.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.; writing—review and editing, O.M and D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to Dubai South for their invaluable assistance in providing all data and resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Müller, R, A Gambardella, and T Huld. 2011. "A power-rating model for silicon PV modules based on standard test conditions." Renewable Energy 36(12), 3292-3298.

- Al Breiki, M, M Al Hammadi, and A Kazim. 2021. Al Hammadi, M., Al Breiki, M., & Kazim, A. Modeling of solar radiation in the United Arab Emirates. Abu Dhabi : Khazna Research Database.

- Al-Naser, F, and N Al-Naser. 2023. "Al-Naser, F., & Al-Naser, N. (2023). Cooling techniques for roof-mounted silicon photovoltaic panels in the UAE." Energies 16(18), 6706.

- Chang, C-T, and H-C Lee. 2016. "Taiwan’s renewable energy strategy and energy-intensive industrial policy." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 64, 456–465. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y, Y Wu, N Chen, C Kang, J Du, and C Luo. 2022. "Calculation of energy consumption and carbon emissions in the construction stage of large public buildings and an analysis of influencing factors based on an improved STIRPAT model." Buildings 12(12),2211. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, J., T. Pearson , and I, Sud. 2004. Procedures for commercial building energy audits. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. America.

- DEWA. 2023. "DEWA’s Smart Grid: an effective tool to reach the smartest and happiest city in the world." DEWA’s Smart Grid: an effective tool to reach the smartest and happiest city in the world. 7 23. https://www.dewa.gov.ae/en/about-us/media-publications/latest-news/2023/07/dewas-smart-grid-an-effective.

- Dubai Supreme Council of Energy. 2024. Dubai Clean Energy Strategy 2050. 5 7.

- 2024. dubaisouth. https://www.dubaisouth.ae/en.

- Furmankiewicz , M., R.J. Hewitt, K. Janc, and J.K. Kazak. 2020. "Europeanisation of energy policy and area-based partnerships: Regional diversity of interest in renewable energy sources in local development strategies in Poland." IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Poland. 609(1), 012033.

- Gulzar, M. M., M Iqbal, S Shahzad, and H Muqeet. 2022. "Load Frequency Control (LFC) strategies in renewable energy-based Hybrid Power Systems: A Review." Energies 15(10), 3488. [CrossRef]

- Holdmann, G.P., R.W. Wies, and J.B. Vandermeer. 2019. "Renewable energy integration in Alaska’s remote islanded microgrids: Economic drivers, technical strategies, technological niche development, and policy implications." IEEE 107((9).

- IEA. 2022. "World Energy Outlook 2022." Licence: CC BY 4.0 (report); CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Annex A). Paris, 10. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022.

- IPCC. 2023. Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Climate Change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, UN.

- Málovics,, G; Csigéné,, N. N.; Kraus, S;. 2008. "Málovics, G., Csigéné, N. N., & Kraus, S. The role of corporate social responsibility in strong sustainability." The Journal of Socio-Economics, 907–918: 37(3). [CrossRef]

- Manjarres, D, R Alonso, S Gil-Lopez, and Landa-Torres I. 2017. "Solar Energy Forecasting and optimization system for efficient renewable energy integration." Data Analytics for Renewable Energy Integration: Informing the Generation and Distribution 1-12.

- Moreno Escobar, J. J, O Morales Matamoros, R Tejeida Padilla, Lina Reyes I, and Quintana Espinosa H. 2021. "A comprehensive review on Smart Grids: Challenges and opportunities." Sensors 21(21), 6978. [CrossRef]

- Mr.genus. 2023. genusnigeria. October 10. https://www.genusnigeria.com/blog/5-factors-that-affect-the-life-of-solar-inverters#:~:text=Install%20your%20solar%20inverter%20in,internal%20temperature%20stable%20and%20optimal.

- Mukeshimana, M.C. , Z-Y. Zhao, and J Nshimiyimana. 2021. "Evaluating strategies for renewable energy development in Rwanda: An integrated swot – ISM analysis." Renewable Energy, 176, 402–414. [CrossRef]

- Nwigwe, U. A., J. Gyimah, J. K. Bonzo, and J. Li. 2024. " Fintech’s role in addressing climate change: insights from the COP28 global stocktake." Environment, Development and Sustainability 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Olatomiwa, L, S Mekhilef, M.S Ismail, and Mogh. 2016. "Energy Management Strategies in hybrid renewable energy systems: A Review." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 62, 821–835. [CrossRef]

- Ordoo, S., R. Arjmandi Karbassi, and A. Mohammadi. 2022. "A managerial analysis of Iran’s renewable energy development strategies to reduce greenhouse gases and improve health.".

- Ozdemir, Ibrahim, Dato Sadja Matthew Pajares Yngson, Dayo Israel, Julius Otundo,, Nathalie Beasnael, Abdoulie Ceesay, and Ashfaq Zama. 2023. COP28 Progress or Regression?An Empirical and Historical Comparative Analysis of COP Summits. Comperative study , Uskudar University.

- Patchell,, J, and R Hayter. 2021. "The cloud’s fearsome five renewable energy strategies: Coupling Sustainable Development Goals with firm specific advantages." Journal of Cleaner Production 288, 125501. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S., M.M. Alam, L.M. Alhems , and Rafique. 2018. "Horizontal axis wind turbine blade design methodologies for efficiency enhancement—A review." Energies 11(3), 506. [CrossRef]

- REN21. 2022. Renewables 2022 Global Status Report. REN21.

- Rubial, Pilar Bueno, Anand Patwardhan, María Luz Falivene Fernández, Joel González, Victoria Laguzzi, Susana Zazzarini, and Carolina Passet . 2023. UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience: key outcomes of COP28 and pathways towards COP29 and COP30. Arg 1.5, university of Maryland.

- South, Dubai. 2023. Dubai South: The City of You. https://www.dubaisouth.ae/en.

- Sulich, A, and L Sołoducho-Pelc. 2021. "Renewable energy producers’ strategies in the Visegrád Group Countries." Energies 14(11), 3048. [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K. 2019. "Towards sustainable strategic management: A theoretical review of the evolution of management perception. ." Research in World Economy 10(4), 58. [CrossRef]

- UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment. 2022. UAE Net Zero 2050.

- UN. 2015. "Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development." Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nation. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication.

- Velasquez, Washington, Guillermo Z. Moreira-Moreira, and Manuel S. Alvarez-Alvarado. 2024. "Smart grids empowered by software-defined network: A comprehensive review of advancements and challenges." IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chun-Kai, and Chien-Ming Lee. 2024. "Power System Decarbonization Assessment: A Case Study." Energies.

- Ying, J, and L Wenbo. 2020. "Research on china’s renewable energy strategic development strategy from the perspective of sustainable development." IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 510(3), 032026.

- Zhang, D, X Han, and C Deng. 2018. "Review on the research and practice of deep learning and reinforcement learning in Smart Grids." CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, 4(3), 362–370. [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework for Solar Energy Deployment in Dubai South.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework for Solar Energy Deployment in Dubai South.

Figure 3.

Case Study Breakdown: Dubai South HQ Solar Project.

Figure 3.

Case Study Breakdown: Dubai South HQ Solar Project.

Figure 4.

Space availability on roof using Helioscope (Source: Helioscope, 2019).

Figure 4.

Space availability on roof using Helioscope (Source: Helioscope, 2019).

Figure 5.

Annual losses from the whole system using PvSyst (Source: PVsyst, 2019).

Figure 5.

Annual losses from the whole system using PvSyst (Source: PVsyst, 2019).

Figure 6.

Sun path diagram using PvSyst (Source: PVsyst, 2019).

Figure 6.

Sun path diagram using PvSyst (Source: PVsyst, 2019).

Figure 7.

Irradiance profile (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Figure 7.

Irradiance profile (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Figure 8.

Energy generated from Inverters. (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Figure 8.

Energy generated from Inverters. (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Figure 9.

Key aspects when developing the financial models.

Figure 9.

Key aspects when developing the financial models.

Figure 10.

Graphic representation of the solar lease model.

Figure 10.

Graphic representation of the solar lease model.

Figure 12.

Thermography imaging of the solar plant.

Figure 12.

Thermography imaging of the solar plant.

Figure 13.

EUI before Solar.

Figure 13.

EUI before Solar.

Figure 14.

EUI after Solar.

Figure 14.

EUI after Solar.

Figure 15.

Carbon emission intensity, tCO2/MWH of electricity generated (2019-2022) DEWA Sustainability Report 2022.

Figure 15.

Carbon emission intensity, tCO2/MWH of electricity generated (2019-2022) DEWA Sustainability Report 2022.

Figure 16.

Aviation District Renewable Energy Integration Roadmap.

Figure 16.

Aviation District Renewable Energy Integration Roadmap.

Figure 17.

Logistics District Renewable Energy Integration Roadmap.

Figure 17.

Logistics District Renewable Energy Integration Roadmap.

Figure 18.

Residential district roadmap.

Figure 18.

Residential district roadmap.

Table 1.

Electricity Consumption (Source: DEWA Utility Records).

Table 1.

Electricity Consumption (Source: DEWA Utility Records).

| Total Consumption 2019 |

|---|

| Jan |

260,518 |

| Feb |

274,984 |

| Mar |

226,179 |

| Apr |

249,506 |

| May |

268,481 |

| Jun |

272,036 |

| Jul |

307,978 |

| Aug |

307,901 |

| Sep |

314,887 |

| Oct |

307,750 |

| Nov |

298,837 |

| Dec |

229,939 |

| Total (kWh) |

3,318,996 |

Table 2.

Estimated solar OFFSET (Source: Computed using PVsyst, 2019).

Table 2.

Estimated solar OFFSET (Source: Computed using PVsyst, 2019).

| Month |

Estimated energy generation (kWh) |

Estimated OFFSET against 2019 baseline |

| Jan |

96,000 |

37% |

| Feb |

101,900 |

37% |

| Mar |

130,600 |

58% |

| Apr |

144,800 |

58% |

| May |

163,600 |

61% |

| Jun |

158,800 |

58% |

| Jul |

149,100 |

48% |

| Aug |

146,400 |

48% |

| Sep |

130,800 |

42% |

| Oct |

120,100 |

39% |

| Nov |

102,000 |

34% |

| Dec |

89,000 |

39% |

Table 3.

Wind speeds- Dubai South (m/s) (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Table 3.

Wind speeds- Dubai South (m/s) (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

| Month |

Maximum wind speed |

Average Wind speed |

| Jan |

17.5 |

2.38 |

| Feb |

14.1 |

2.13 |

| Mar |

14.1 |

2.35 |

| Apr |

13.6 |

2.05 |

| May |

14.6 |

2.73 |

| June |

15.1 |

2.49 |

| Jul |

21.1 |

2.65 |

| Aug |

12.3 |

2.2 |

| Sept |

11 |

2.21 |

| Oct |

11.2 |

1.9 |

| Nov |

10.4 |

1.85 |

| Dec |

12.4 |

1.84 |

Table 4.

Temperature measurements (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Table 4.

Temperature measurements (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

| Month |

Temperature (Lufft WS501 BM: RS485-1 65) [°C] |

Temperature 1 (Irradiance 210°) [°C] |

Temperature 1 (Irradiance 300°) [°C] |

Temperature 1 (Irradiance 039°) [°C] |

Temperature 1 (Irradiance 120°) [°C] |

Temperature 2 (Irradiance 210°) [°C] |

Temperature 2 (Irradiance 300°) [°C] |

Temperature 2 (Irradiance 039°) [°C] |

Temperature 2 (Irradiance 120°) [°C] |

| Jan |

20.26 |

23.61 |

23.73 |

23.14 |

23.83 |

21.35 |

21.4 |

21.53 |

21.29 |

| Feb |

20.96 |

26.11 |

25.72 |

25.2 |

25.96 |

23.55 |

23.39 |

23.51 |

23.28 |

| Mar. |

25.18 |

31.46 |

30.64 |

30.29 |

30.93 |

29.24 |

28.49 |

28.63 |

28.71 |

| Apr |

29.07 |

36.4 |

35.17 |

34.8 |

35.46 |

33.99 |

33.18 |

33.26 |

33.35 |

| May |

30.69 |

38.67 |

36.87 |

37.02 |

37.37 |

36.29 |

35.24 |

35.26 |

35.47] |

| June |

36.46 |

42.29 |

41.33 |

41.32 |

41.51 |

40.61 |

39.51 |

39.65 |

39.95 |

| Jul |

36.05 |

43.11 |

42.56 |

42.61 |

42.7 |

41.78 |

40.95 |

41.18 |

41.49 |

| Aug |

36.31 |

43.16 |

42.22 |

42.15 |

42.38 |

41.29 |

40.27 |

40.42 |

40.68 |

| Sept |

33.42 |

39.94 |

39.29 |

39.22 |

39.36 |

38.32 |

37.42 |

37.58 |

37.8 |

| Oct |

30.05 |

35.33 |

35.19 |

34.56 |

35.36 |

33.34 |

33.06 |

33.15 |

33.12 |

| Nov |

27.02 |

31.31 |

31.2 |

30.55 |

31.36 |

28.87 |

28.86 |

28.81 |

28.66 |

| Dec |

22.83 |

26.32 |

26.53 |

25.92 |

26.56 |

23.86 |

24.04 |

24.16 |

23.8 |

Table 5.

Starting from January, where the lowest average temperature was recorded, the generation was the lowest at 96.13 MWh. Then as the average temperature increases the generation increases consequently till it peaks in May with a generation of 179.49 MWh where the temperature is 35.88 degrees Celsius. Even though the average temperature continues to increase in June and July the generation drops due to the temperature effect degradation. As the temperature starts to drop again from August till December the generation remains stable. Other factors that could impact the generation beside the average temperature are sun hours, cloudy days, rainy days, and operational and maintenance tasks.Table 5. Energy Generation vs Average temperature (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Table 5.

Starting from January, where the lowest average temperature was recorded, the generation was the lowest at 96.13 MWh. Then as the average temperature increases the generation increases consequently till it peaks in May with a generation of 179.49 MWh where the temperature is 35.88 degrees Celsius. Even though the average temperature continues to increase in June and July the generation drops due to the temperature effect degradation. As the temperature starts to drop again from August till December the generation remains stable. Other factors that could impact the generation beside the average temperature are sun hours, cloudy days, rainy days, and operational and maintenance tasks.Table 5. Energy Generation vs Average temperature (Source: Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

| Month |

Average measured temperature [°C] |

Actual Generation (MWh) |

| Jan |

22.24 |

96.13 |

| Feb |

24.19 |

123.33 |

| Mar |

29.29 |

158.94 |

| Apr |

33.85 |

163.62 |

| May |

35.88 |

179.49 |

| June |

40.29 |

169.50 |

| Jul |

41.38 |

144.70 |

| Aug |

40.99 |

151.39 |

| Sept |

38.04 |

140.48 |

| Oct |

33.68 |

151.39 |

| Nov |

29.63 |

140.48 |

| Dec |

24.89 |

129.09 |

Table 6.

Distribution losses (Source: Computed using Meteocontrol sensor data and utility meter readings, 2022).

Table 6.

Distribution losses (Source: Computed using Meteocontrol sensor data and utility meter readings, 2022).

| Month |

Distribution Loss (%) |

| January |

1.32 |

| February |

1.36 |

| March |

1.31 |

| April |

1.64 |

| May |

1.28 |

| June |

1.29 |

| July |

1.22 |

| August |

1.24 |

| September |

1.20 |

| October |

1.25 |

| November |

1.25 |

| December |

1.29 |

Table 7.

Performance Ratio (Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

Table 7.

Performance Ratio (Meteocontrol, Author’s Data Collection, 2022).

| Year |

Performance Ratio [%] |

| 2020 |

81.69 |

| 2021 |

81.97 |

| 2022 |

81.83 |

Table 8.

Risk identification.

Table 8.

Risk identification.

| Risks |

Description of Risks |

| Technical Risks |

· Equipment failure or underperformance. |

| · Incorrect system design or component mismatch. |

| · Degradation of solar panels faster than expected. |

| Environmental Risks |

· Unexpected shading or site changes impacting solar generation. |

| · Extreme weather conditions (e.g. sand storms) damaging equipment. |

| Financial Risks |

· Fluctuating currency exchange rates affect equipment costs. |

| · Unanticipated increases in project costs. |

| · Delays leading to increased financing costs. |

| Regulatory and Compliance Risks |

· Changes in government policies and regulations affect project viability. |

| · Non-compliance with local environmental or safety regulations. |

| · Permitting and licensing delays. |

| Operational Risks |

· Inadequate maintenance leads to reduced system efficiency. |

| · Vandalism or theft of equipment. |

| · Health and safety incidents during installation or maintenance. |

Table 9.

Risk Assessment.

Table 9.

Risk Assessment.

| Risk |

Likelihood (low/medium/high) |

Potential Impact (low/medium/high) |

| Equipment failure or underperformance |

Medium |

High |

| Incorrect system design or component mismatch |

Low |

Medium |

| Degradation of solar panels faster than expected |

Low |

Medium |

| Unexpected shading or site changes |

Low |

Medium |

| Extreme weather conditions damaging equipment |

Low |

High |

| Fluctuating currency exchange rates |

Medium |

Medium |

| Unanticipated increases in project costs |

Low |

Medium |

| Delays leading to increased financing costs |

Medium |

High |

| Changes in government policies or subsidies |

Low |

High |

| Non-compliance with local regulations |

Low |

High |

| Permitting and licensing delays |

Low |

Medium |

| Poor maintenance |

Low |

Medium |

| Vandalism or theft of equipment |

Low |

Medium |

| Health and safety incidents |

Low |

High |

Table 10.

Risk response strategies.

Table 10.

Risk response strategies.

| Risk |

Strategy |

Action |

| Equipment failure or underperformance |

Mitigate |

Regularly maintain and monitor the equipment. Selection of tier 1 project components with excellent warranty and workmanship. |

| Incorrect system design or component mismatch |

Avoid |

Ensure experienced professionals design the system, and regularly review before either approval or rejection of the design. |

| Degradation of solar panels faster than expected |

Mitigate |

Selection of tier 1 solar panels as per the highest industry available products. |

| Unexpected shading or site changes |

Avoid |

Conduct thorough site assessment and choose locations with minimal likelihood of future shading if so incorporate the potential shading effect on the design. |

| Extreme weather conditions damaging equipment |

Transfer |

Invest in insurance that covers damage due to extreme weather conditions. |

| Fluctuating currency exchange rates |

Transfer |

Engage in hedging or other financial instruments to lock in current exchange rates. |

| Unanticipated increases in project costs |

Mitigate |

Have a comprehensive project scope to avoid any future variations. Continuous monitoring of the project costs |

| Delays leading to increased financing costs |

Avoid |

Have a realistic project timeline. Selection of experienced contractor for the project. Employing competent project managers. |

| Changes in government policies or subsidies |

Transfer |

Utilization of power purchase agreements or solar lease contracts that removes the liability that such policy changes may impact. |

| Non-compliance with local regulations |

Avoid |

Draft contracts with contractors that cover such non-compliances to be under the contract’s scope. Also, constant review and follow ups on the compliance status. |

| Permitting and licensing delays |

Mitigate |

Make use of previous project experiences when it comes to permitting timelines and requirements along with the respective documentations. |

| Poor maintenance |

Avoid |

Engage with reliable contractors to fulfill the AMC against the highest applicable industry standards as well as providing KPI to monitor the performance of such party. |

| Vandalism or theft of equipment |

Transfer |

Getting insurance against the whole system to provide the required protection |

| Health and safety incidents |

Avoid |

Implement health and safety awareness training and assurance of compliance against all safety standards. |

Table 11.