1. Introduction

This study aligns with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7: “Affordable and Clean Energy”, emphasising the need for sustainable energy sources to support human and economic development [

1]. Access to reliable and sustainable energy is a fundamental driver of social and economic progress, influencing key sectors such as healthcare, education, and industry. In many remote communities, energy access remains a challenge, limiting opportunities for economic growth and social well-being.

The industrial revolution reached Cuba in the mid-19th century, bringing profound socioeconomic and environmental transformations. While it improved living standards for some segments of the population, it also exacerbated social inequalities and initiated large-scale environmental degradation through deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions. Today, Cuba’s energy sustainability indicators reveal critical gaps, with scores below 0.75 in key areas: energy productivity, basic needs coverage, environmental purity, renewable energy adoption, and energy autarky. Among these, the large-scale deployment of renewable energy sources (RES) presents the most significant opportunity to improve systemic performance [

2].

Integrated energy management remains underdeveloped at the local level, despite its potential to drive energy efficiency and clean energy policies—a gap highlighted by [

3]. Municipal Energy Management Systems (MEMS) could address this, leveraging local governments’ growing interest in resource management and alignment with national RES policies [

4]. This approach aligns with emerging global paradigms like Energy Communities (ECs), which prioritise collaborative, socially inclusive models for renewable energy access [

5]. For instance, in the EU, Member States are required to include Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) in their national energy and climate plans and to implement measures providing technical and financial support [

6].

The development of renewable energy sources (RES) and energy efficiency in Cuba is governed by Decree-Law No. 345 (November 2019)

1. Its Third Section outlines prioritized RES, including sugarcane biomass, solar photovoltaic, wind energy, and other biomass applications. It also highlights distributed generation and cogeneration as key strategies to maximize RES integration into the National Electric System (SEN).

Furthermore, the decree establishes that the primary economic criterion for investments will be a country-level cost-benefit analysis. Under this framework, Article 5 prioritizes investments in scientific research and technological innovation within the sector. Finally, the decree underscores the role of self-consumption and cogeneration in achieving the 24% share of RES in the energy mix by 2030 [

7].

Cuba’s current energy transition strategy, as outlined by [

8], aims to achieve "a rapid shift toward energy sovereignty, security, and sustainability at minimal economic and environmental cost". Municipal Development Strategies (MDS)—mandated under Cuban law [

9]—serve as key instruments for local implementation, while Decree 110/2024 institutionalizes five-year RES and efficiency programs [

10]. Together, these frameworks underscore Cuba’s commitment to reaching 24% RES penetration by 2030, though success hinges on decentralizing governance and empowering grassroots initiatives.

Cuba, with its dependence on imported fossil fuels, faces significant energy security issues. This dependence contributes to economic vulnerabilities and environmental degradation, highlighting the necessity for a transition toward renewable energy solutions. Hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES), which integrate multiple energy sources such as solar, wind, and biomass, offer a promising approach to address these challenges by enhancing energy reliability, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and fostering local economic development [

11]. In other hand, the intermittency of renewable energies has a particular impact on their use in isolated areas. In this sense, the incorporation of hybrid microgrids (MHES) has a high value in addressing this problem [

12].

This research aims to analyse the viability of implementing HRES in Cuba, focusing on its environmental and socioeconomic impacts, by leveraging Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and input-output modelling. The study provides a comprehensive evaluation of both direct and indirect effects associated with these systems, offering valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders interested in advancing sustainable energy solutions in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

The evaluation of environmental and socioeconomic impacts is fundamental to understanding the sustainability of HRES. In this work, the methodological approach for the sustainability assessment of the system combines two life cycle approach-based methodologies. First, environmental sustainability is assessed using the life cycle analysis method; otherwise, the socioeconomic impacts along the supply chain are calculated using an Input-Output methodology [

13]. Both of them share the same supply chain or life cycle perspective and analyse the effects along the whole supply chain. This study employs two key methodologies: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to assess environmental impacts and the Input-Output model to evaluate socioeconomic implications. These methods provide a holistic approach to analysing the feasibility and long-term benefits of the proposed system.

2.1. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

A LCA was used to evaluate the environmental impact of the hybrid system throughout its lifecycle, from raw material extraction to disposal. This method quantifies emissions, energy consumption, and resource use, allowing for a comprehensive comparison between the current fossil fuel-based energy system and the proposed hybrid system. Inventory data were gathered from databases such as Ecoinvent (

https://ecoinvent.org/) and Social Hotspot Data Base (

http://www.socialhotspot.org/), using SimaPro software (

https://simapro.com/) for impact calculations, this tool is widely used by researchers, designers, environmental departments, and innovation teams to assess the sustainability of systems and products and in this case, has been crucial for assembling the hybrid plant and obtaining the environmental impacts associated with it. The LCA framework ensures that environmental considerations, such as carbon footprint and resource efficiency, are factored into decision-making processes.

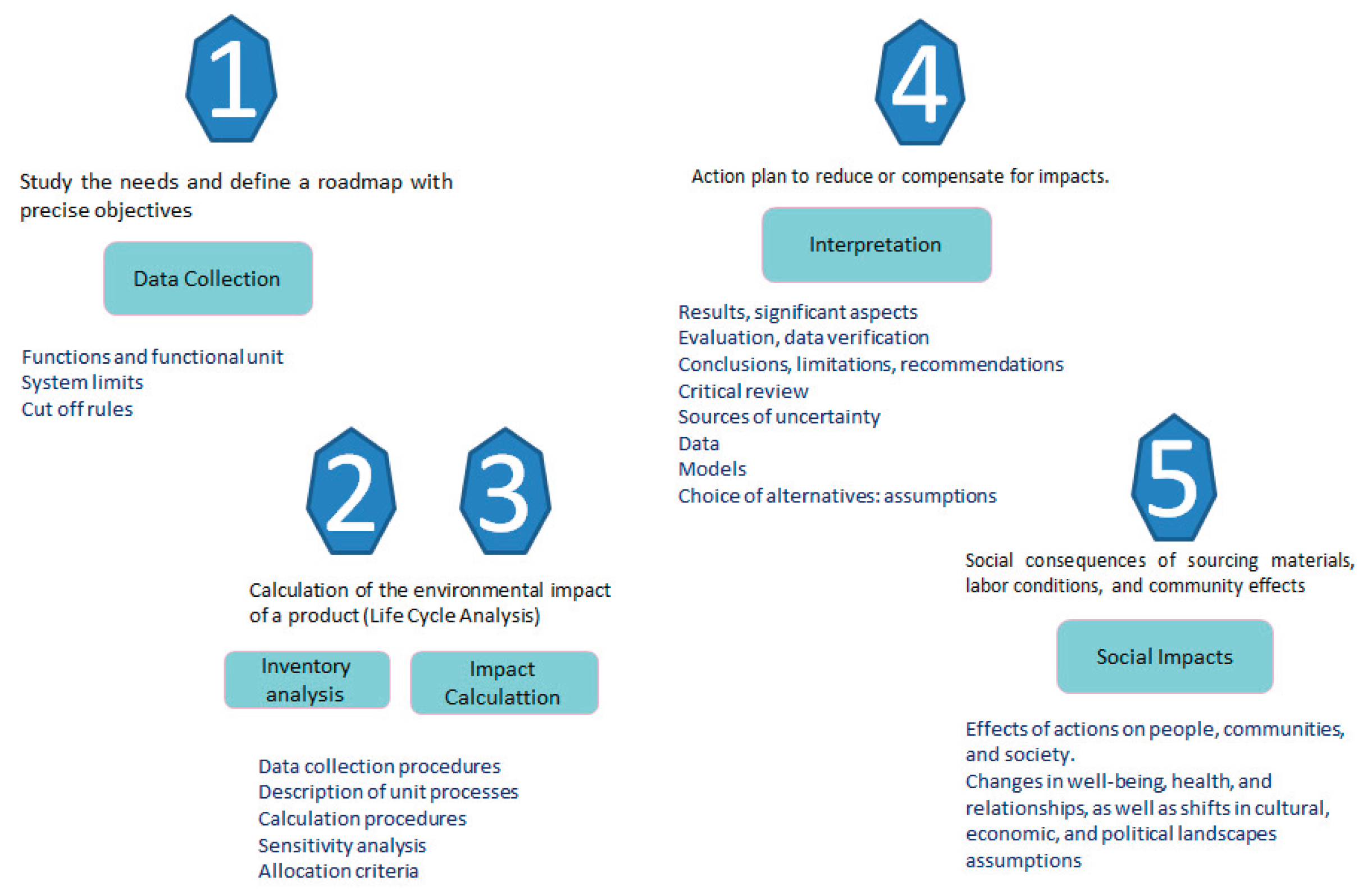

The key steps in this work are structured around the four main phases of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation. The sequence of steps followed in this study is illustrated in

Figure 1:

Data Collection: Environmental, technical, and social data were gathered from a variety of sources such as Ecoinvent [

14] and SHDB [

15], as well as national statistics and technical reports.

Inventory Assembly: The detailed data on the equipment involved in the hybrid system was incorporated into the inventory [

16].

Impact Calculation: Using SimaPro, the environmental, social, and economic impacts of the system were quantified for each life cycle phase [

17].

Impact Interpretation: The calculated impacts (e.g., carbon footprint, resource use, social effects) were used to inform decisions regarding the design, operation, and potential improvement of the hybrid plant [

18].

Social Impacts: The potential social consequences of sourcing materials, labour conditions, and community effects [

19].

2.1.1. System Description

The hybrid microgrid was designed to meet the estimated daily energy demand of 437 kWh, with a total generation capacity of 545 kWh/day. The system integrates a 40 kW photovoltaic (PV) plant, a 10 kW biomass gasification plant, a 3 kW wind turbine, and a diesel generator for backup (80 kW). Energy storage was sized at 160 kWh to ensure reliability during periods of low solar or wind generation. Data for the LCA were sourced from the Ecoinvent database and the Social Hotspot Database (SHDB), while socioeconomic analysis relied on Cuban economic data and input-output modeling.

The portion of an LCA study that is specific to the product the system being modelled is often called the foreground of the model, while the parts that reflect the industrial economy as a whole and are drawn from reference databases are the background [

20]. The various factors influencing the system's operation are outlined below and further detailed in the following items. These include: site characteristics (such as loads, topography, and available resources like biomass, solar, and wind); system components (including the biomass gasifier, generator set, photovoltaic generator, wind turbine, batteries, and electronic converter); and relevant economic parameters.

2.1.1.1. Site Characteristics

Site characteristics play a crucial role in determining the suitability and effectiveness of a hybrid energy system. Key factors include renewable energy potential in terms of site's exposure to solar radiation, wind speed and direction, and available water resources for hydropower are essential for maximising the use of renewable sources. Factors like terrain, soil type, and potential for grid connectivity influence the feasibility and cost of implementing these systems. An in depth study was carried out by Geographic Information Systems (GIS) [

21]. The study addressed all relevant aspects of the Guasasa community. This coastal community is located in the south of the country, in the municipality of Cienaga de Zapata in the province of Matanzas.

The place and capacity of distributed energy units have a positive impact on the efficiency of the microgrids (MG) [

22]. In this study, site characteristics refer to the comprehensive set of physical, social, technical, and resource-related factors that influence the design and operation of a hybrid energy microgrid. These include:

-

General Site Conditions

- ·

Geographic location: GPS coordinates, accessibility, topography, and land conditions.

- ·

Existing infrastructure: Current power systems, buildings suitable for equipment installation.

- ·

Legal and environmental constraints: Protected areas, aviation regulations, environmental impacts (e.g., wildlife concerns).

- 2

-

Socioeconomic Analysis

- ·

Demographics: Number of households, age and gender distribution.

- ·

Economic activities: Main sources of income (e.g., fishing, forestry, community services).

- ·

Community organization: Involvement of local institutions and stakeholders.

- ·

Needs and motivations: For example, the demand for 24-hour electricity supply (vs. current 12-hour service).

- 3

-

Energy Consumption Analysis

- ·

Building typology: Type and number of residential and service buildings.

- ·

Energy usage patterns: Electrical appliances, typical loads, hours of operation.

- ·

Growth projections: Expected increase in energy demand over time.

- 4

-

Available Renewable Resources

- ·

Solar: Evaluated using databases such as Meteonorm and SolarGIS.

- ·

Wind: Assessed using NASA data and the Global Wind Atlas.

- ·

Biomass: Availability and type (e.g., yarúa, soplillo, ocuje), carbon content, calorific value, and logistics for collection and supply.

- 5

-

Technical and Installation Conditions

- ·

Land evaluation: Suitability of the terrain, accessibility for equipment delivery and installation.

- ·

Grid integration options: Cable routing possibilities (overhead or underground), connection points.

- 6

-

Load characterization

- ·

The population of Guasasa is made up of a total of 214 people, distributed among 85 dwellings, a health care, a pharmacy, a school, and some other collective use dependencies.

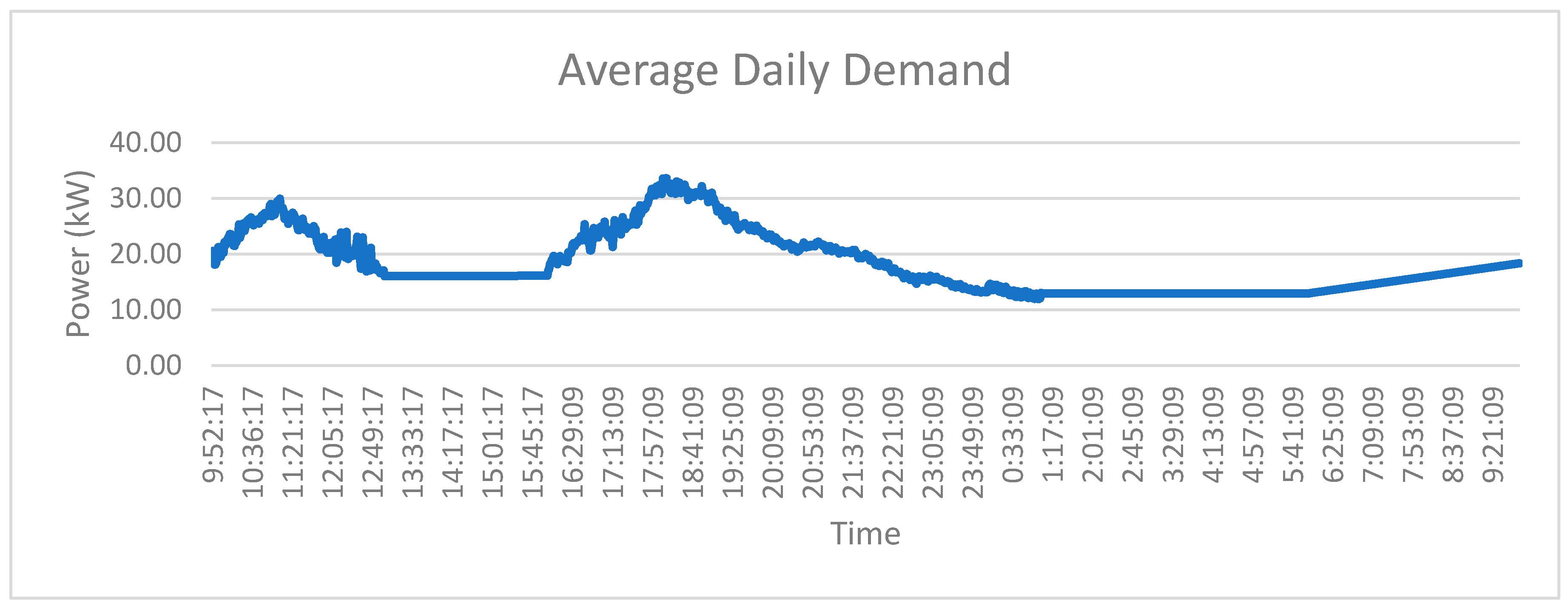

In this context, it is proposed to increase the hours of supply (currently 12 hours) to reach a situation of 24 hours a day consumption. Even though some measuring campaigns of the existing situation (12 hours supplied from the genset) were undertaken, the design load profile (24 hours supplied from the microgrid) was estimated, as shown in the

Figure 2

Characterization of Renewable Resources

The renewable resources considered in this study include solar, wind, and biomass. Their characterization is detailed below:

-

Solar Resource

The assessment of solar potential was conducted using several well-established databases, including Meteonorm, NASA’s Surface Meteorology and Solar Energy database, and the Global Solar Atlas powered by SolarGIS. These sources provide reliable data on solar irradiance and other relevant parameters for the selected location.

- 2.

-

Wind Resource

Two main data sources were used for wind characterization: NASA’s meteorological database and the Global Wind Atlas. The Global Wind Atlas offers a variety of data, including wind roses, average wind speeds, and energy density at altitudes of 50, 100, and 200 meters, along with GIS layers compatible with ArcGIS. However, since hourly average values are not provided, NASA’s database was used for time-resolved wind data.

- 3.

-

Biomass Resource

The biomass resource assessment is based on several key parameters:

- ·

Available Biomass (tons/day): Biomass is assumed to be used as feedstock for a gasifier to generate syngas, which is then converted into electricity by generators. In Guasasa, the primary biomass sources include yarúa, soplillo, and ocuje. The available biomass is considered to exceed the plant’s needs by a significant margin. The required biomass to meet the estimated electricity demand is calculated using the following formula: Biomass (kg/h) = Gas Consumption (kg/h)/Gasification Ratio (kg/kg)

The gas consumption is determined based on the generator’s power output and fuel consumption curve. A gasification ratio of 1.89 kg/kg is used, as detailed in subsequent sections.

- ·

Average Price: Estimated at 120 CUP/ton, equivalent to 5 USD/ton (using an exchange rate of 1 USD = 24 CUP).

- ·

Carbon Content (%): Based on laboratory analyses, the average carbon content of the biomass is estimated at 48%, and this value is used consistently across calculations.

2.1.1.2. System Components

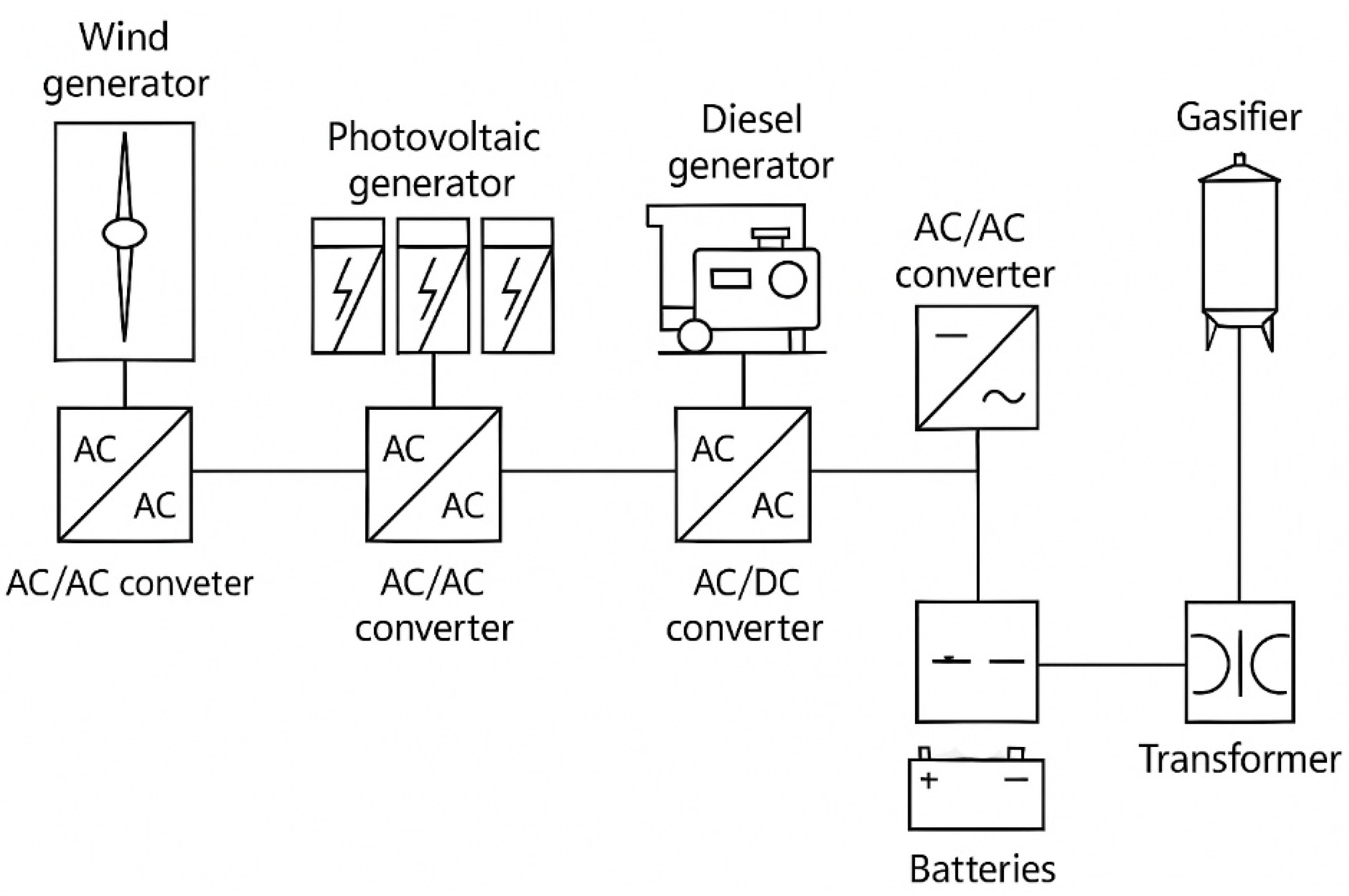

As noted above, in this work, the system is composed of a 40kWp solar PV generator, 20 kWp of which are connected to the AC bus through two solar inverters, and the other 20 kWp are connected to the DC bus through the respective two charge regulators; there is one 3 kW wind turbine, a 10 kW gasifier, 50kWh Li-Ion battery (the evolution of this technology through these years has made it possible to enter in the final configuration); there are three bidirectional converters 10 kW each, one for the gasifier and two for the microgrid; the role of the genset is performed by the grid, which is a particular bi-phase one; and includes also all the necessary equipment for the implementation of the microgrid. In

Figure 3, a single line diagram for the layout of the final microgrid is shown.

- 1.

-

Current Diesel Generator: The diesel generator will maintain the current generation level, providing a fixed amount of power (80 kW).

For this analysis, was assumed it operates at a constant output

- 2.

-

Photovoltaic (PV) Plant

Capacity: 40 kW

-

Power Distribution:

- °

50% directly to the microgrid: 40 kW * 50% = 20 kW delivered to the grid.

- °

50% to storage: 40 kW * 50% = 20 kW directed to storage for later use.

- 2.

Storage: The storage system needs to be sized to accommodate this 20 kW input, depending on the expected charging time and the capacity required to meet demand during times of low solar generation (nighttime or cloudy weather). For example, if you need 8 hours of storage, the required storage capacity would be 20 kW * 8 hours = 160 kWh.

- 3

-

Biomass Gasification Plant

Capacity: 10 kW

Operating Time: 8 hours a day (since it's a demonstration plant).

Daily Generation: 10 kW * 8 hours = 80 kWh/day.

The biomass plant will contribute 10 kW for the 8 hours it is in operation. If the system requires continuous power, the biomass plant will provide a portion of that during its operational hours, and the other power needs will need to be fulfilled by other generation sources like the diesel generator, PV, or storage.

- 4

-

Wind Turbine

Capacity: 3 kW

Voltage Output: 220 V AC, three-phase alternator with permanent neodymium magnets.

-

This turbine will generate 3 kW of power when operating at peak conditions. However, it’s important to account for variable wind conditions, so the actual output could be lower. In areas with intermittent wind, the turbine might not produce its full rated power all the time.

The system supplies 545 kWh/day, exceeding the estimated demand (437 kWh/day) by 25% [

21].

- 5.

-

Sizing Considerations:

Total Available Generation (Peak): Diesel + 40 kW (PV) + 10 kW (biomass) + 3 kW (wind).

Depending on the diesel generator's capacity, this could range from a minimum of 33 kW (if the diesel generator is not contributing additional power) to a larger total if the diesel is more powerful.

Storage: As previously mentioned, if 20 kW from the PV system is stored and you want to store it for 8 hours, you would need 160 kWh of storage. You’ll also want to factor in the wind turbine’s contribution to the storage system, especially if wind generation is intermittent.

Distribution and Load Management: The storage will likely need to be managed to balance the load during times when generation exceeds demand or when demand exceeds generation. A combination of energy management systems (EMS) and possibly power converters (like inverters for DC to AC) will be required to integrate the diverse generation sources and storage into the microgrid effectively.

Storage System:

At least 160 kWh to store the 50% output of the PV system (20 kW) for 8 hours, ensuring energy is available when solar generation is low or demand exceeds production.

Load Balancing:

Balancing the generation and storage system will ensure the microgrid can meet both peak and off-peak loads, especially considering intermittent wind and solar power. This configuration will help you provide reliable power to the microgrid, considering both renewable energy sources and traditional backup (diesel), along with storage for managing supply and demand fluctuations. In this sense, the different sources (diesel, solar, biomass, and wind) and storage are required to ensure a continuous power supply.

2.1.2. Inventory Analysis

Environmental Data:

Collected from Ecoinvent, a global database containing comprehensive and consistent life cycle data for various processes, materials, and technologies.

Social Data:

Gathered from the Social Hotspot Database (SHDB), which provides social impact data (e.g., working conditions, human rights) related to industries and materials used in the project.

National Statistics & Technical Reports:

Data from these sources were used to monitor the project's evolution and to fill in any gaps in the environmental and social impact data.

Inventory Considerations:

Equipment: The specific equipment used in the hybrid plant was cataloged and analyzed. The exact inventory details are listed in

Table 1.

2.1.3. Environmental Impact Assessment

Once the inventory of the hybrid plant system was compiled and quantified, the next step involved evaluating the most significant environmental impacts associated with the system. This process focused on assessing impact categories that are most relevant to the system and that could be characterised based on the available data. For this analysis, the environmental impacts were assessed using the following key indicators:

- ·

Environmental Footprint

This indicator measures the impact an individual, organisation, or activity has on the environment, specifically how much natural resources they consume and how much waste they produce [

23].

- ·

Climate Change (Global Warming Potential, GWP):

This indicator focuses on the greenhouse gas emissions produced throughout the life cycle of the system [

24]. It quantifies the contribution of the hybrid plant to global warming by evaluating the emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and other greenhouse gases.

This indicator measures the total energy consumption over the life cycle of the system, taking into account both the direct and indirect energy inputs required for the production, operation, and disposal of the equipment used in the system [

25]. CED includes energy from all sources (renewable and non-renewable) and helps to evaluate the overall energy intensity of the hybrid system.

2.2. Socioeconomic Analysis

A multiregional input-output method (MRIO) was employed to assess economic impacts, estimating employment generation and production multipliers based on Cuban economic data. The Input-Output methodology, originally developed by Wassily Leontief, analyses interdependencies between economic sectors, providing insights into how investments in renewable energy systems influence job creation, value-added production, and economic stimulation [

26]. By integrating cost specific data into a multi-country perspective, this study estimates both direct and indirect economic effects, both inside Cuba and abroad, considering how renewable energy investments contribute to broader economic activity. The EORA database has been used as the source of the MRIO [

27], for year 2016.

This dual-method approach (LCA and MRIO) ensures a comprehensive assessment of both environmental sustainability and socioeconomic viability, providing a solid foundation for policy recommendations and future energy planning in Cuba.

3. Results

The proposed hybrid system reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 60%, from 1.14 to 0.47 kg CO2eq/kWh, aligning with Cuba’s commitments under the Paris Agreement. Additionally, the system reduces fossil energy consumption by 50%, demonstrating its potential to enhance energy security and sustainability. Socioeconomic analysis reveals that the system generates 129.4 jobs, with the majority of initial investment benefits accruing to foreign suppliers. However, the operation and maintenance phases offer significant opportunities for local employment, highlighting the need for workforce training and capacity-building.

The results of the different components of the study are described in detail below.

3.1. Environmental Impact Assessment

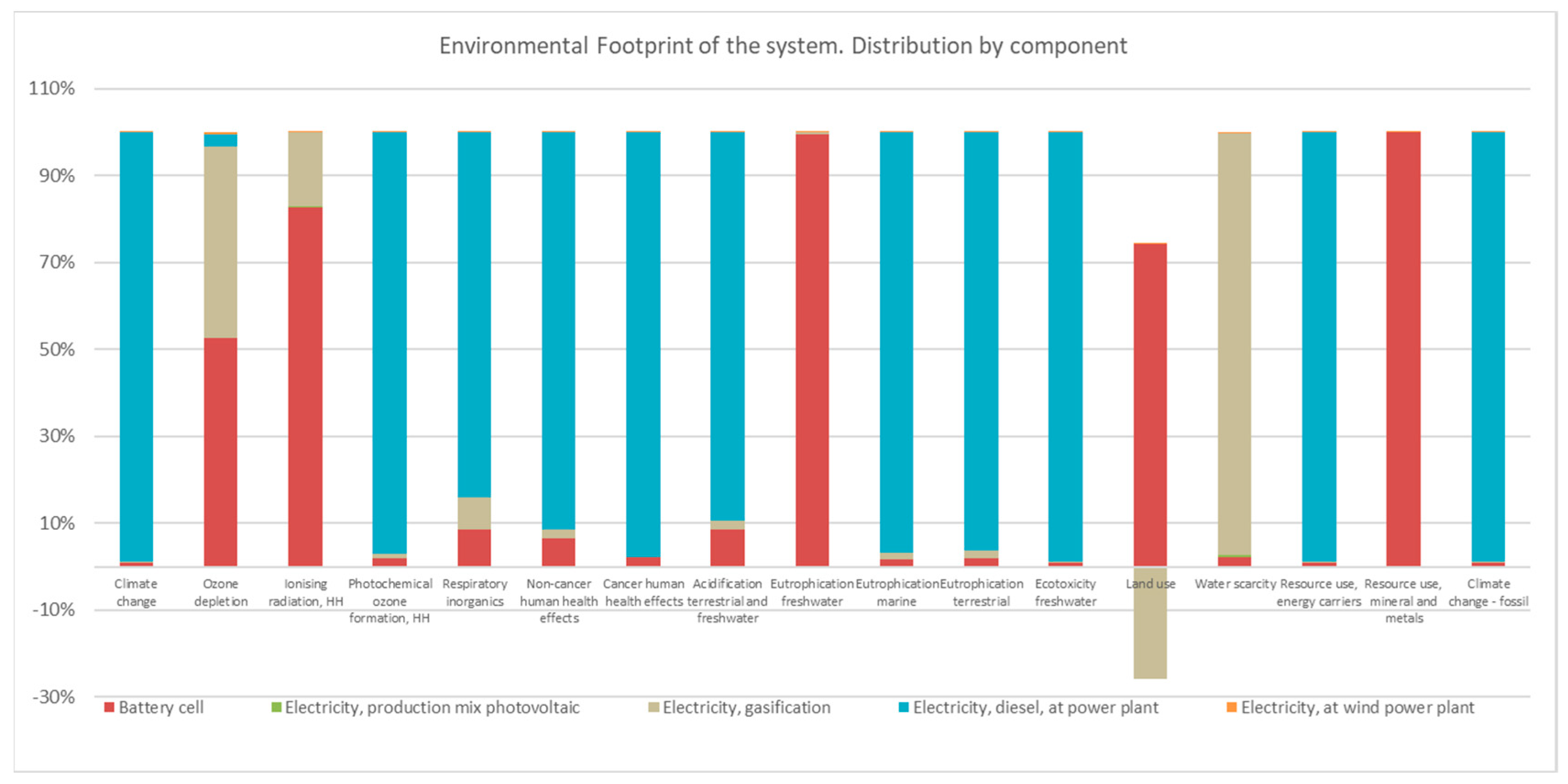

Environmental Footprint. This indicator measures the impact an individual, organisation, or activity has on the environment, specifically how much natural resources they consume and how much waste they produce. The distribution obtained by components could be see in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Environmental Footprint of the system. Distribution by component.

Figure 5.

Environmental Footprint of the system. Distribution by component.

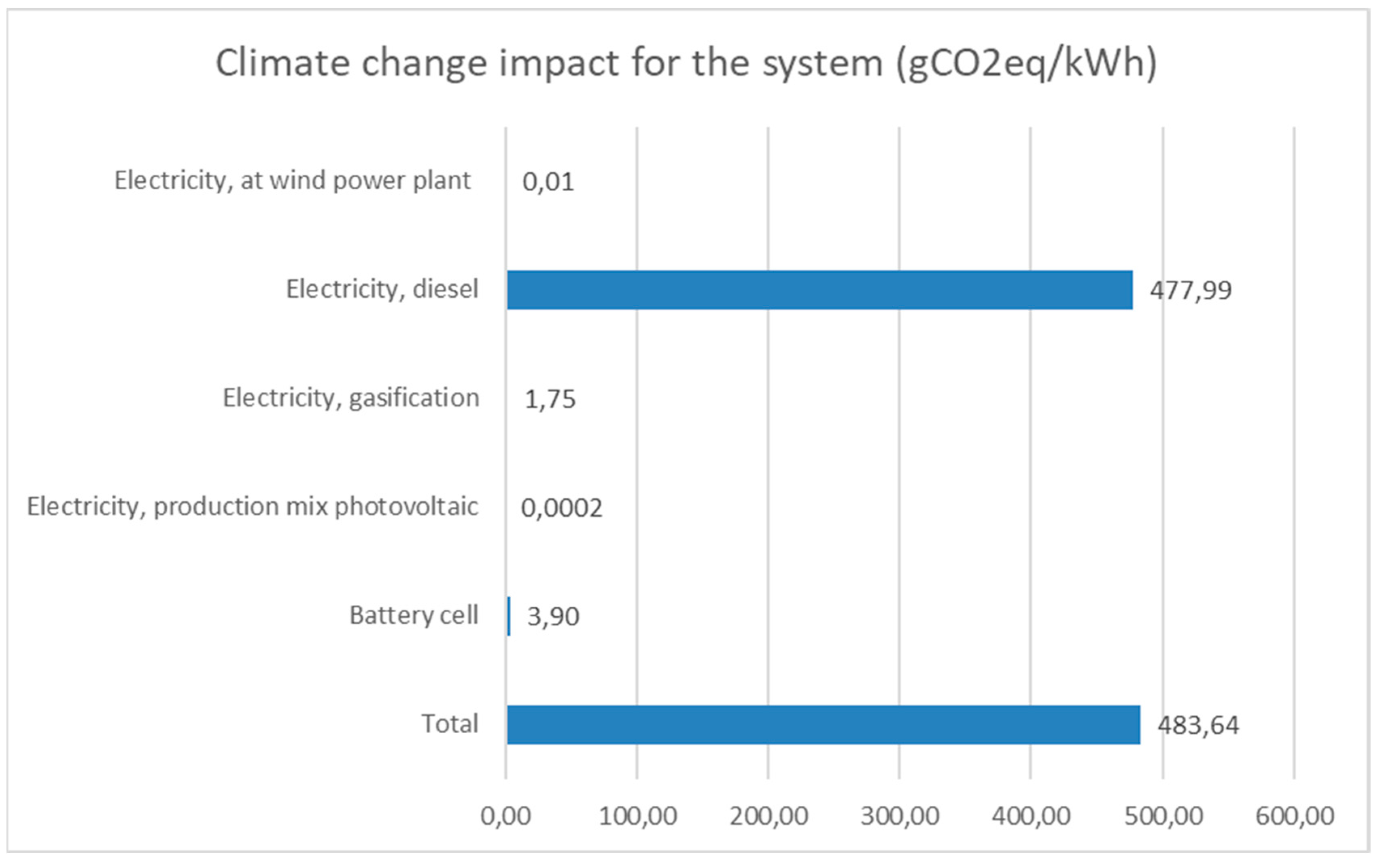

Climate Change (Global Warming Potential, GWP): The goal was to assess how the system's generation sources (e.g., diesel, PV, biomass, wind) contribute to climate change, particularly in terms of their carbon footprint. Figure 6 shows the climate change impact of the system in gCO2eq/kWh.

Figure 6.

The climate change impact of the system by component.

Figure 6.

The climate change impact of the system by component.

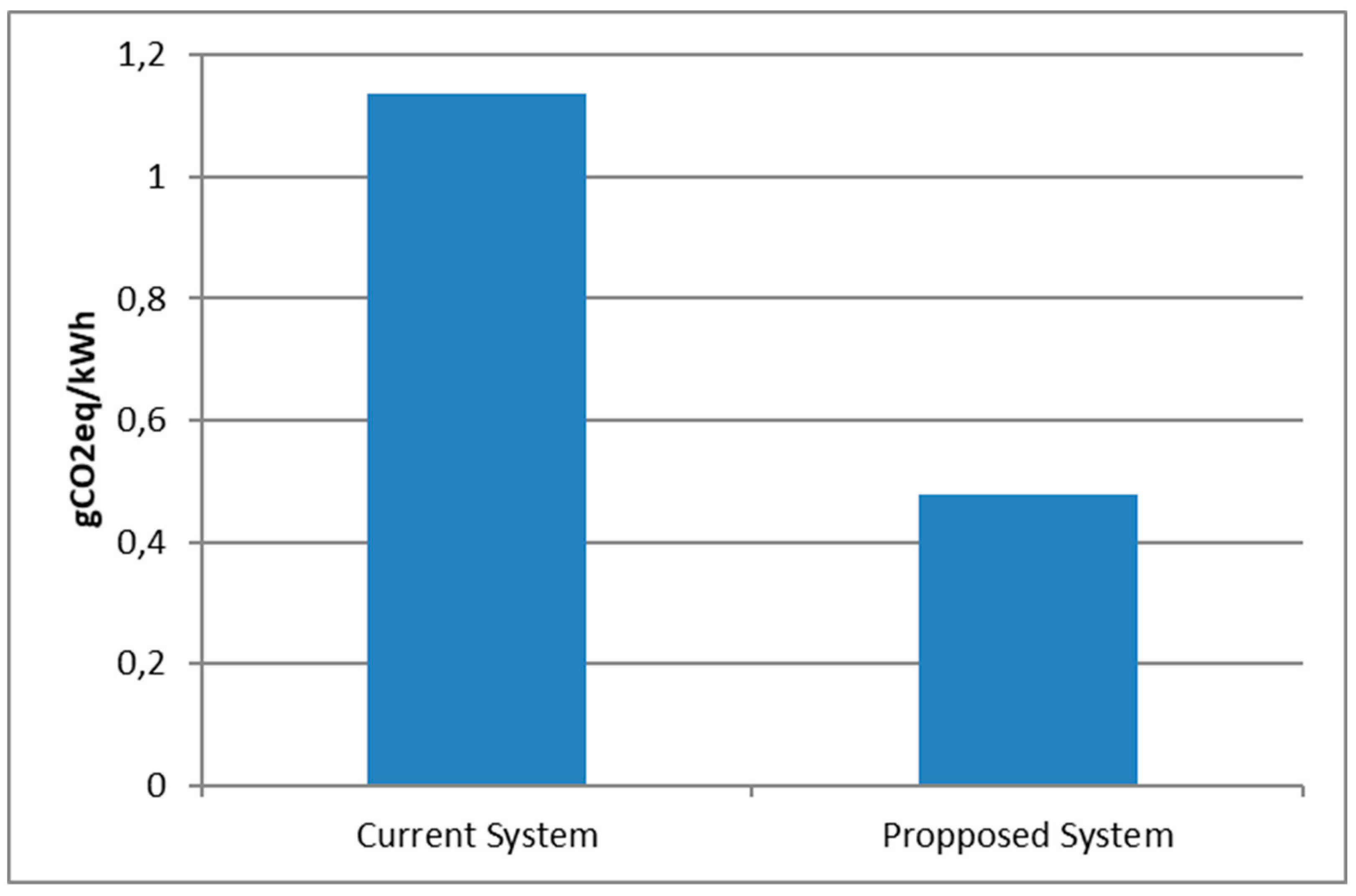

The analysis confirms that the proposed system significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions by close to 60% lowering emissions from 1.140 to 0.484 g CO2eq/kWh. This improvement requires a deep understanding of the emission sources for further improvements. (See Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis of the systems under study.

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis of the systems under study.

In this sense, potential optimisations can be identified, such as:

Increasing the share of renewable energy.

Improving system efficiency.

Reducing indirect emissions from energy storage or backup sources.

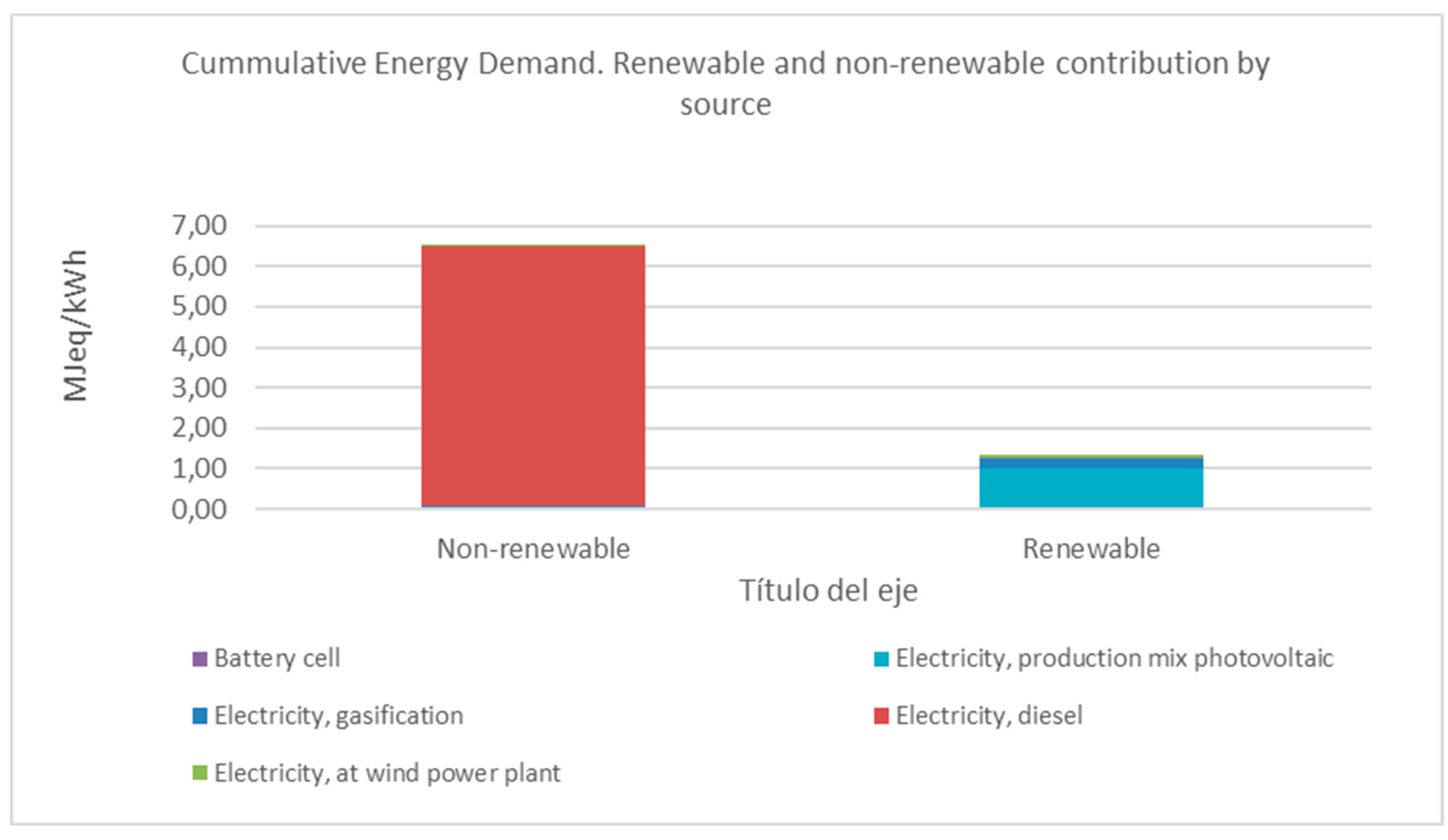

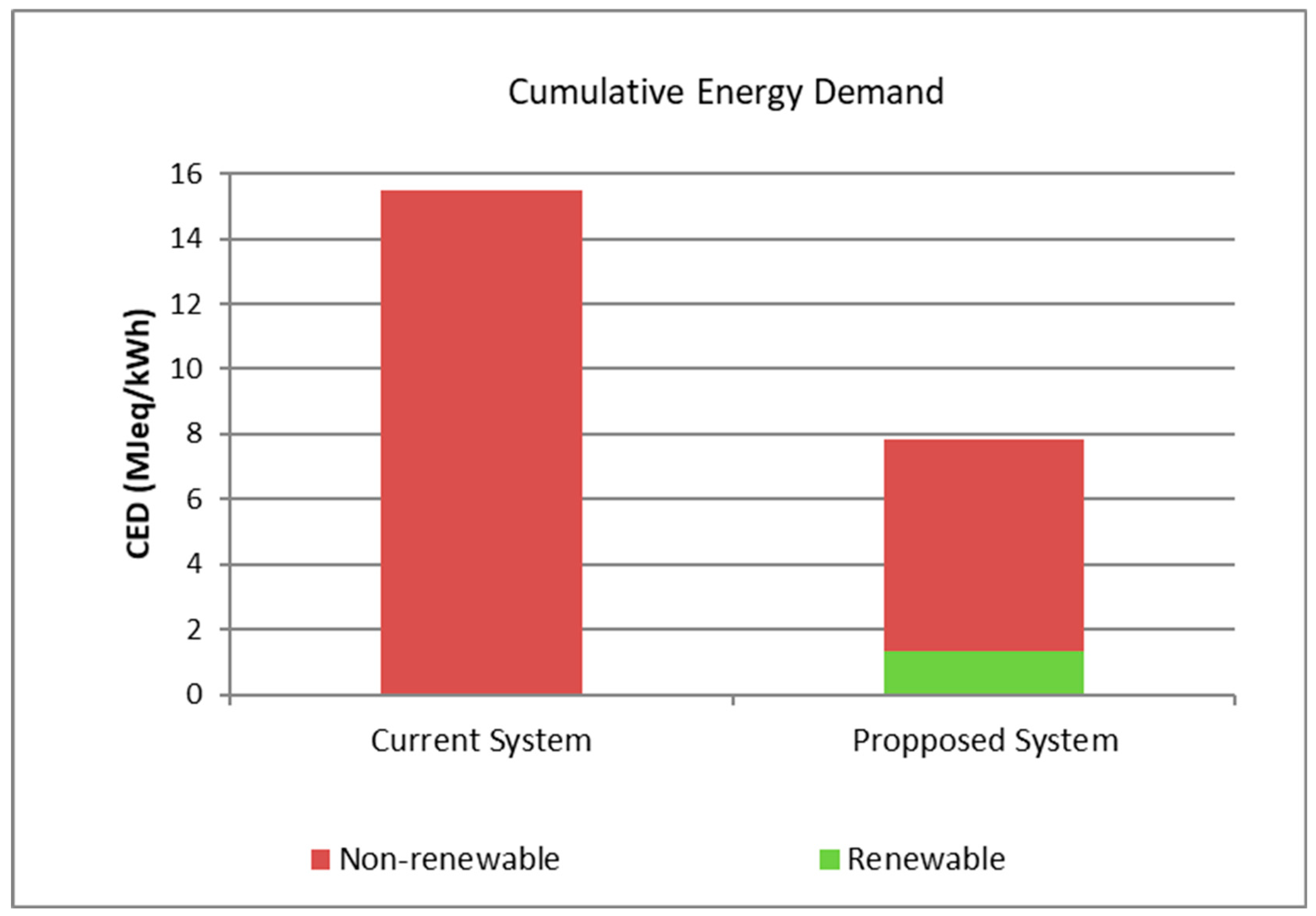

Cumulative Energy Demand (CED): The results were quantified based on the specific operations of each component in the hybrid plant, such as the diesel generator, PV system, biomass plant, wind turbine, and storage (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

CED for the proposed system.

Figure 8.

CED for the proposed system.

For this indicator, the results indicate that the proposed system reduces fossil energy consumption by approximately 50% compared to the current diesel-based system, as can be seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

CED comparative for the systems under study.

Figure 9.

CED comparative for the systems under study.

Results suggest that the proposed system relies more on renewable sources or improves efficiency in energy conversion and storage. Furthermore, the lower dependence on fossil fuels shift reduces environmental impacts beyond just greenhouse gas emissions, including resource depletion and pollution from fuel extraction and transportation.

Finally, the potential for further optimisation, considering that some fossil energy is still being used (e.g., backup generators, grid electricity), further reductions could be explored through increased renewable integration, energy storage solutions, or demand-side management

3.2. Socioeconomic Impact

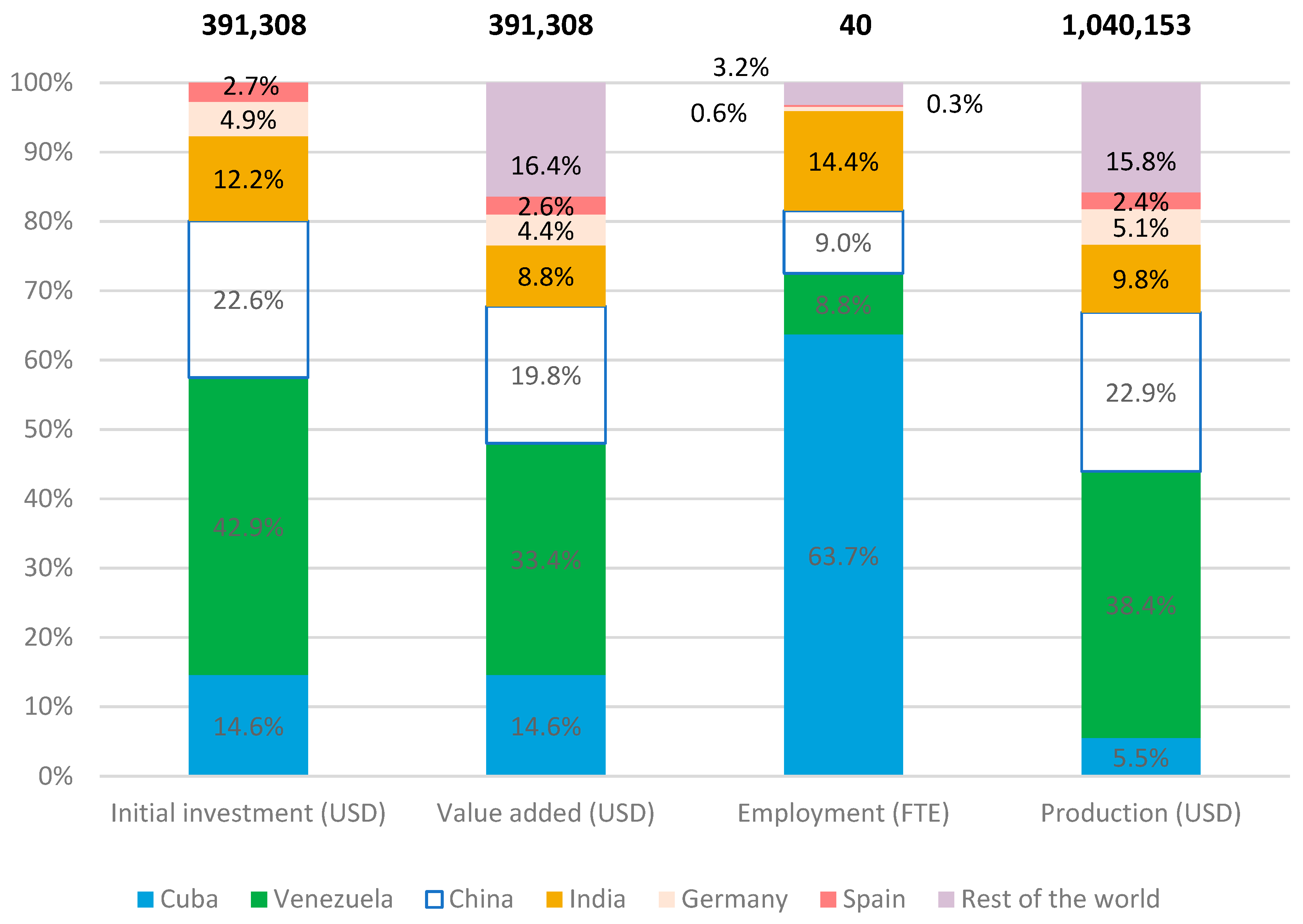

In the case of the HIBRI2 project

2, the initial investment (the investment costs, including the diesel generator already installed, and an estimate of the operating and maintenance cost streams, duly discounted to present values) amounts to USD 336,264. Cuba imports almost all of the necessary components, and spends a miniscule amount on transporting the biomass. In this sense, the countries that benefit most are Venezuela (we assume that the diesel comes from that country), followed by China (generator, batteries and transformers), India (biogas gasifier), Germany (photovoltaic generator) and Spain (wind turbine) (see Figure 10, first bar). We bring the investment to the net present value (at a discount rate of 9%) to assess the socioeconomic impacts.

Figure 10.

Socioeconomic impacts from HIBRI2 deployment. .

Figure 10.

Socioeconomic impacts from HIBRI2 deployment. .

The initial investment is made by acquiring components that have gone through a complex production process to completion. Thus, value added redistributes the initial investment by identifying the country of origin of the labour and capital payments for each of the goods and services required. The concept of global value chains, and the importance of international trade in intermediate goods from the rest of the world in the production of final goods and services, is therefore represented in terms of value added (see Figure 10, second bar).

In terms of employment, without considering in-plant jobs, almost 15 jobs expressed in terms of full time equivalents or FTE, would be generated directly and indirectly in the process and during the life cycle of the hybrid plant. These data are estimates subject to the limitations of the input-output methodology, but serve to give an idea of the employment impacts. India appears to be one of the biggest beneficiaries, due to its employment-intensive production structure. The rest of the world also generates 1.3 jobs despite not having directly stimulated final demand in this region. Overall, almost all employment is generated outside Cuba. Employment indicators such as jobs/million USD or jobs/MW installed are within the range offered by other similar studies in the literature [

28]. Specifically, almost 44 jobs/million USD and 102 jobs/MW. Recall that these data include indirect jobs.

Estimating in-plant employment for the operation and maintenance phase, there is a very sharp increase in job creation in Cuba (see Figure 10 third column). This is due to the low wages received by workers in the country. Assuming labour costs of around 55,000 USD as well as an annual salary per worker of 2,152 USD over the 20-year life of the hybrid plant, 63.7% of the employment generated would be in Cuba. This increases the two indicators previously mentioned considerably: 103 jobs/million USD, and more than 280 jobs/MW. These figures are subject to uncertainty, due to data limitations concerning Cuban compensation of employees. However, the key message remains the same: employment generation in Cuba comes hand in hand with plant employment.

Finally, we can see that the impacts on production are remarkable: this investment exerts a multiplier effect of 2.66 on production, which means that one monetary unit invested in the project triggers 2.66 times the effects on production (including indirect linkages).

The benefits in terms of value-added retention and job creation would be much greater if Cuba could develop a domestic industry in renewable energy manufacturing. Currently, dependence on foreign components negatively influences their participation in creating growth and employment, as well as the very sustainability of the facilities. However, in terms of energy security and achieving goals towards energy decarbonisation, this is a positive example for the country.

Table 2 summarises in full the results obtained.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The findings of this study align with previous research on hybrid renewable energy systems, which have demonstrated significant environmental and economic benefits in other regions [

29]. However, the unique socioeconomic context of Cuba presents both challenges and opportunities. While the majority of initial investment benefits accrue to foreign suppliers, the long-term economic benefits of local job creation and energy security are substantial. Policymakers should consider strategies to incentivize local manufacturing of renewable energy components, such as tax breaks or subsidies for domestic producers. Additionally, workforce training programs could enhance local capacity for system operation and maintenance, further maximizing the socioeconomic benefits of renewable energy investments.

Comparisons with existing literature confirm the emission reduction potential of hybrid energy systems [

30]. Previous studies highlight that the integration of renewable energy sources in microgrids can significantly decrease reliance on fossil fuels, leading to lower emissions and increased energy resilience. The findings of this study align with these conclusions, demonstrating that hybrid systems can achieve substantial environmental benefits in the Cuban context.

In addition to environmental advantages, the economic impacts of the proposed system reveal critical insights. While the majority of the initial investment benefits foreign suppliers due to Cuba’s reliance on imported components, the long-term benefits in job creation within the country are noteworthy. The operation and maintenance phase of the system provides the most significant employment opportunities, emphasizing the need for local workforce training and capacity-building to maximize the socioeconomic benefits of renewable energy investments.

Furthermore, the study suggests that Cuba could enhance its economic gains by fostering a domestic renewable energy industry. Reducing dependence on imported equipment would not only increase economic retention within the country but also contribute to technological innovation and energy security. Policymakers should consider strategies to incentivize local manufacturing, research, and development in the renewable energy sector.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential of hybrid renewable energy systems to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, enhance energy security, and stimulate economic development in Cuba. The findings underscore the importance of integrating multiple renewable energy sources to achieve these benefits, as well as the need for policy interventions to maximize long-term economic gains. Future research should explore the scalability of HRES across different regions of Cuba, considering variations in resource availability and economic conditions. Additionally, further investigation into policy frameworks and financial mechanisms could facilitate the large-scale adoption of renewable energy technologies in the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.H. and J.D.; methodology, I.H, J.D, Y.L, S.B; software, I.H. and S.B; validation, I.H, J.D, Y.L and S.B.; formal analysis, I.H and J.D.; investigation, I.H and S.B.; resources, I.H, J.D, Y.L, S.B.; data curation, I.H and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D and I.H.; writing—review and editing, J.D and I.H.; visualization, I.H, J.D, Y.L, S.B.; supervision, J.D.; project administration, J.D.; funding acquisition, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), grant number 2018/ACDE/000600, under the innovation action HIBRI2.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our recognition of the fundamental work at the HIBRI2 project of the Cuban Center for Information Management and Energy Development (CUBAENERGÍA) as well as the NGO Cuban Society for the Promotion of Renewable Energy Sources and Respect for the Environment (CUBASOLAR). Special thanks to the people of Guasasa and the municipality’s authorities. Thanks also to the Spanish NGO Sodepaz for its leadership in the development of the project and for providing key data for this paper. Thanks to the Spanish company Bornay Aerogeneradores for their invaluable collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CIEMAT |

Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (Spain) |

| HRES |

Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| RES |

Renewable Energy Sources |

| MEMS |

Municipal Eneregy Management System |

| SEN |

Electrical National System (Cuba) |

| MDS |

Municipal Development Strategies |

| MG |

MicroGrids |

| MHES |

Hybrid Microgrids |

| SHDB |

Social Hotspot Data Base |

| GPS |

Global Position System |

| NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (USA) |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

| CUP |

Cuban Peso |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| EMS |

Energy Management System |

| AC-DC |

Alternating Current/Direct Current |

| PERC |

Passivated Emitter and Rear Contact solar technology |

| GWP |

Global Warming Potential |

| CED |

Cumulative Energy Demand |

| MRIO |

Multiregional input-output method |

| HIBRI2 |

Integrated control system for energy supply through hybrid systems in isolated communities in Cuba. Phase II |

| FTE |

Full time equivalent (jobs) |

| CUBAENERGIA |

Cuban Center for Information Management and Energy Development |

| CUBASOLAR |

Cuban Society for the Promotion of Renewable Energy Sources and Respect for the Environment |

References

- NU; CEPAL. The 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals: An opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean. Goals, Targets and Global Indicators; 2019-01-07 2019.

- Gómez, W.; Wong, A.B. Cuba y la sustentabilidad energética. Energía y tú 2008.

- Erario, S. The Maine energy handbook. A Resource for Municipalities on Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Energy.; 2010.

- Correa Soto, J.; González Pérez, S.; Hernández Alonso, Á. La Gestión Energética Local: Elemento del Desarrollo Sostenible en Cuba. Revista Universidad y Sociedad 2017, 9, 59-67.

- Gavela, E. Policy Brief: InclusivEC - Comunidades Energéticas Inclusivas. Guía de Buenas Prácticas Guía de Buenas Prácticas para la inclusión y la lucha para la inclusión y la lucha contra la pobreza energética.; 2024.

- Pizzuti, I. C. (2024). Integration of photovoltaic panels and biomass-fuelled CHP in an Italian renewable energy . Energy Conversion and Management, 1-18.

- Estado, C.d. Decreto-Ley no. 345 “del desarrollo de las fuentes renovables y el uso eficiente de la energía”. 2019, 345, 17.

- (MINEN), M.d.E.y.M. La transición energética en Cuba. Situación actual y perspectivas. In Proceedings of the XVI Taller Internacional “CUBASOLAR 2024”, La Habana. Cuba., 19 al 21 de noviembre 2024, 2024.

- Cuba., M.d.J. Decreto 33/2021 Para la Gestión Estratégica del Desarrollo Territorial. 2021.

- Ministros., C.d. Decreto 110. Regulaciones para el control y uso eficiente de los portadores energéticos y las fuentes renovables de energía. . 2024.

- Domínguez, J.; Carraro, F.; Sánchez, S.; Bérriz, L.; Arencibia, A.; Zarzalejo, L.; Ciria, P.; Ramos, R.; Sánchez-Hervás, J.M.; Ortíz, I.; et al. Cogeneración de energía, eléctrica y térmica, mediante un sistema híbrido biomasa-solar para explotaciones agropecuarias en la Isla de Cuba; CIEMAT: Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Makai, L.; Popoola, O. A review of micro-hybrid energy systems for rural electrification, challenges and probable interventions. Renewable Energy Focus 2025, 53, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, I.; Rodríguez-Serrano, I.; Garrain, D.; Lechón, Y.; Oliveira, A. Sustainability assessment of a novel micro solar thermal: Biomass heat and power plant in Morocco. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2020, 24, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): overview and methodology. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NewEarth, B. (2022). End User License Agreement (EULA) for the Social Hotspots Database. York, Maine.

- Heath, G. (2019). Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Electricity Generation.

- Goedkoop, M.; Oele, M.; Leijting, J.; Ponsioen, T.; Meijer, E. Introduction to LCA with SimaPro; 2016; p. 80.

- Mahmud, M.A.P.; Huda, N.; Farjana, S.H.; Lang, C. Life-cycle impact assessment of renewable electricity generation systems in the United States. Renew Energy 2020, 151, 1028–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.; Indrane, D.; de Beer, I. Handbook for Product Social Impact Assessment 2018; 2018.

- Kuczenski, B.; Marvuglia, A.; Astudillo, M.F.; Ingwersen, W.W.; Satterfield, M.B.; Evers, D.P.; Koffler, C.; Navarrete, T.; Amor, B.; Laurin, L. LCA capability roadmap—product system model description and revision. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2018, 23, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shayeghi, H.; Alilou, M. 3 - Distributed generation and microgrids. In Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems and Microgrids, Kabalci, E., Ed.; Academic Press: 2021; pp. 73-102.

- Domínguez, J.; Bellini, C.; Arribas, L.; Amador, J.; Torres-Pérez, M.; Martín, A.M. IntiGIS-Local: A Geospatial Approach to Assessing Rural Electrification Alternatives for Sustainable Socio-Economic Development in Isolated Communities—A Case Study of Guasasa, Cuba. Energies 2024, 17, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, S. A. (2012). Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) Guide. Ispra: European Commision.

- Müller, L.; Kätelhön, A.; Bringezu, S.; McCoy, S.; Suh, S.; Edwards, R.; Sick, V.; Kaiser, S.; Cuellar-Franca, R.; Khamlichi, A.; et al. The carbon footprint of the carbon feedstock CO 2. Energy & Environmental Science 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Wyss, F.; Büsser Knöpfel, S.; Lützkendorf, T.; Balouktsi, M. Cumulative energy demand in LCA: the energy harvested approach. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2015, 20, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Blair, P.D. Input-Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions, 2 ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009.

- Lenzen, M.; Daniel, M.; Keiichiro, K.; and Geschke, A. Building Eora: A Global Multi-Region Input–Output Database At High Country And Sector Resolution. Economic Systems Research 2013, 25, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R., Heptonstall, P. & Gross, R. Job creation in a low carbon transition to renewables and energy efficiency: a review of international evidence. Sustain Sci 19, 125–150 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Seiyefa Aondo Vincent, Abubakar Tahiru, Raphael Oluwatobiloba Lawal, Chisom Emmauel Aralu, Adebule Quam Okikiola, 2024. Hybrid renewable energy systems for rural electrification in developing countries: Assessing feasibility, efficiency, and socioeconomic impact. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 24, 2190–2204. [CrossRef]

- López-González, A.; Domenech, B.; Ferrer-Martí, L. Sustainability Evaluation of Rural Electrification in Cuba: From Fossil Fuels to Modular Photovoltaic Systems: Case Studies from Sancti Spiritus Province. Energies 2021, 14, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).