Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Study design and setting

- Isolation and identification of bacteria

- Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

- Data collection tools

- Data management and statistical analysis

- Sampling technique and sample size

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Quality control

3. Results

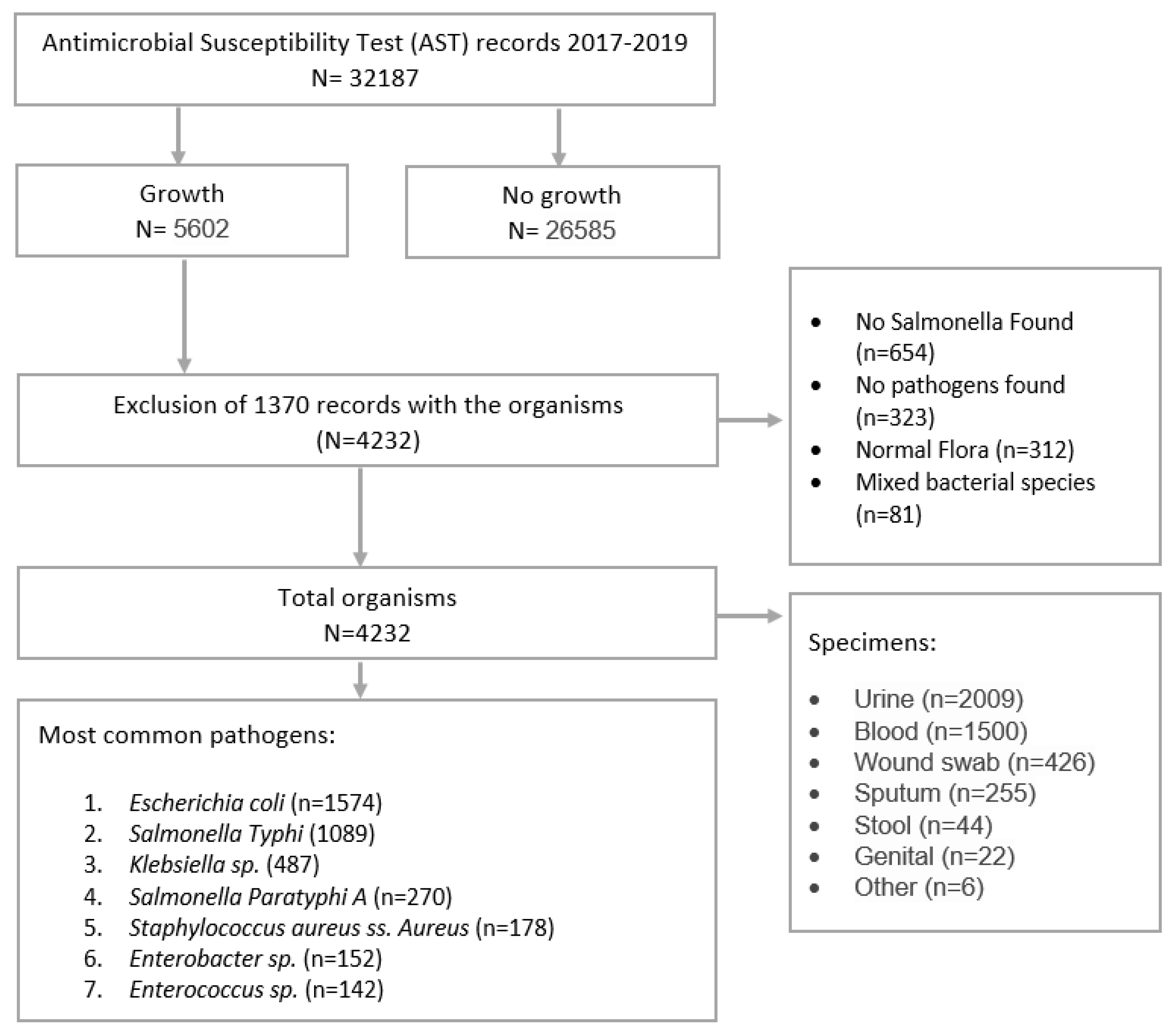

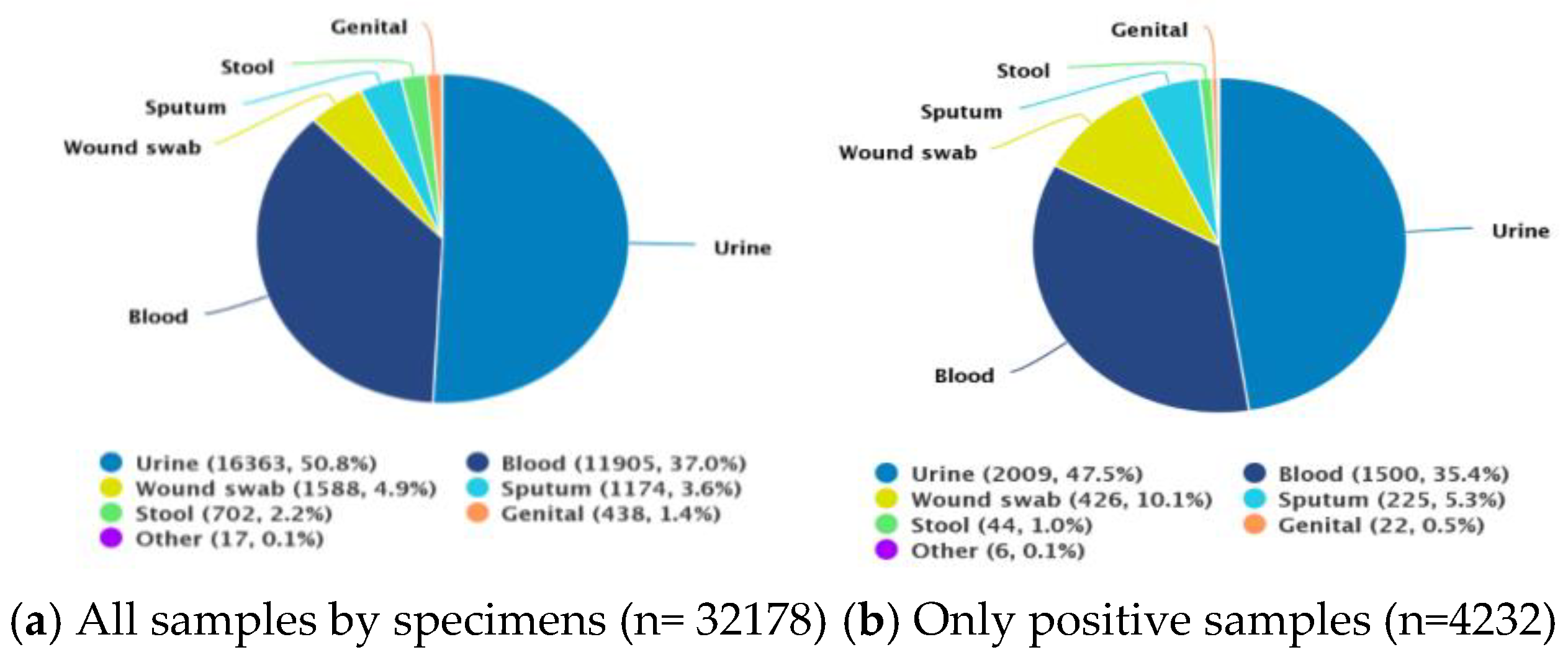

3.1. Profile of Patients, Clinical Specimens, and Bacterial Isolates

3.1.1. Bacterial Isolates and Frequency of Organisms

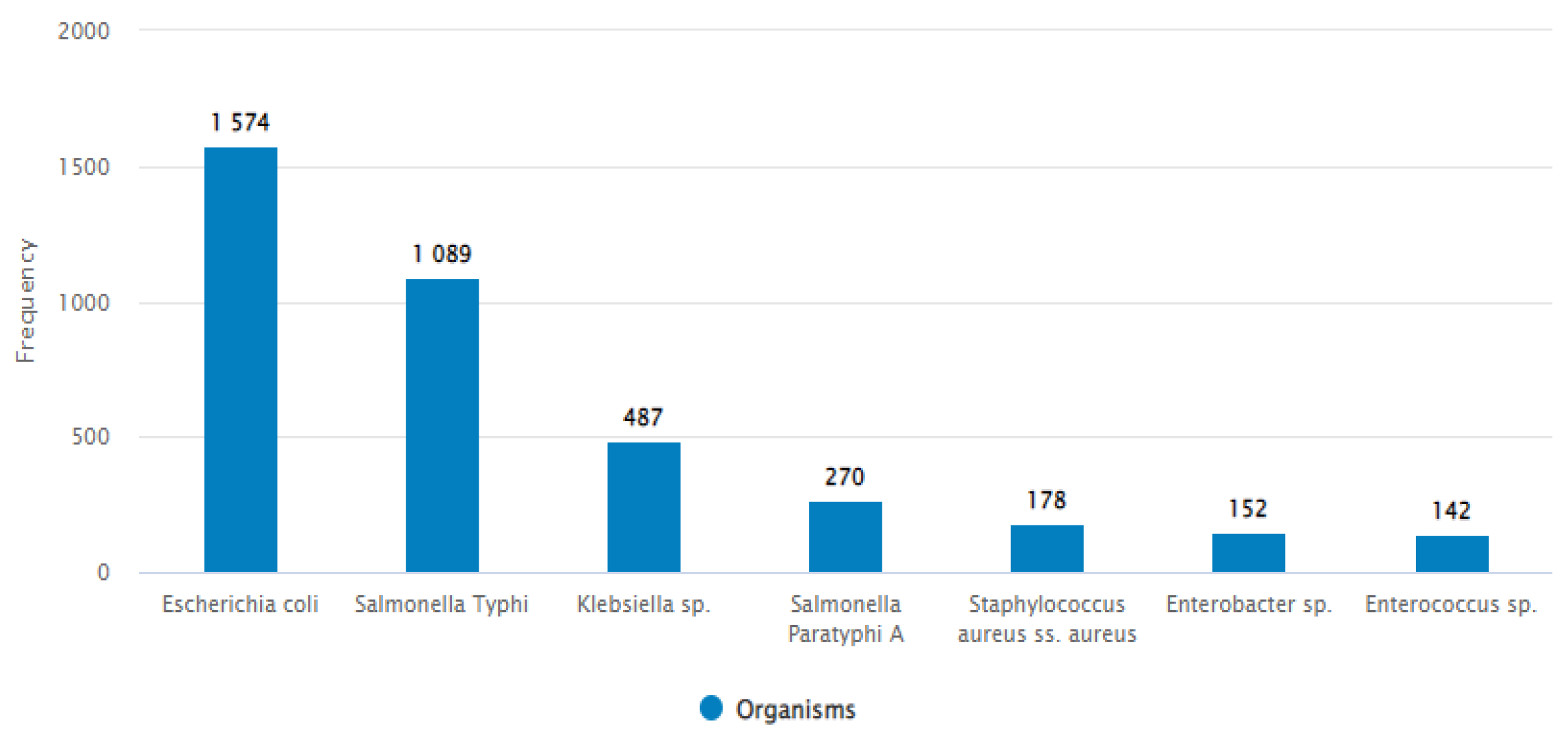

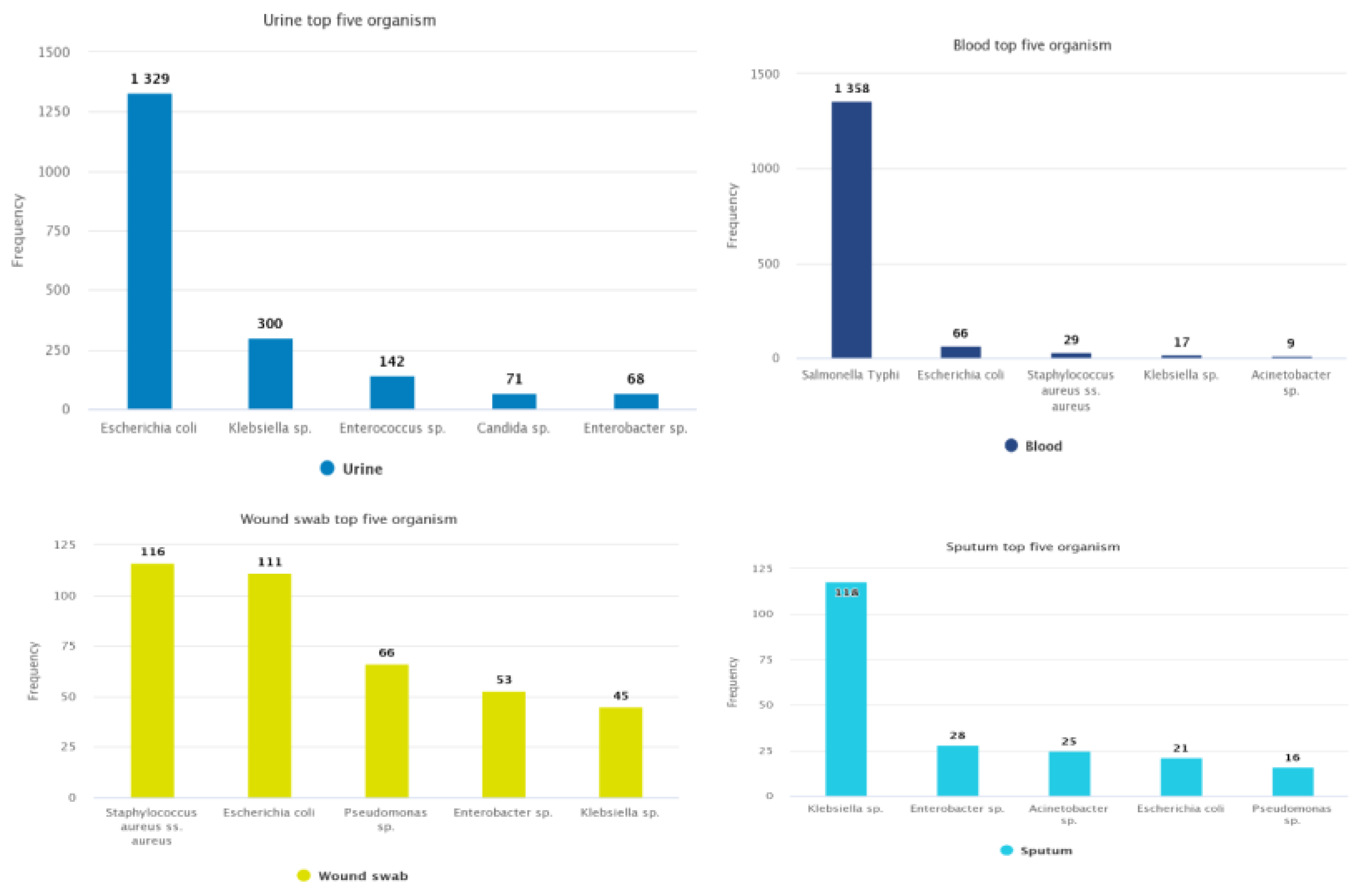

3.1.2. Most Commonly Found Pathogens

3.1.3. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of Bacterial Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAMC | Uttara Adhunik Medical College |

| CAPTURA | Capturing Data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia |

| IEDCR | Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control & Research |

| CDC | Communicable Disease Control |

| MoHFW | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

| QAAPT | Quick Analysis of Antimicrobial Patterns and Trends |

| CLSI | Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute |

| EUCAST | European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

References

- O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. London: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2016.

- Mulu, W.; Kibru, G.; Beyene, G.; Damtie, M. Postoperative nosocomial infections and antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacteria isolates among patients admitted at FelegeHiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012, 22, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Rabbi, M.B.; Sultana, S. Antibiotic resistance in Bangladesh: A systematic review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019, 80, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Rabbani, R.; Ahmed, H.S.; Sarker MA, S.; Zafrin, N.; Rahman, M.M. Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of urinary tract infection at a tertiary care hospital. Bangladesh Critical Care Journal 2014, 2, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, B.; Kibret, M.; Mulu, W. Knowledge and beliefs on antimicrobial resistance among physicians and nurses in hospitals in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, 2019. New report calls for urgent action to avert antimicrobial resistance crisis. World Health Organization website. Available online: https://www. who. int/news-room/detail/29-04-2019-new-reportcalls-for-urgent-action to avert-antimicrobial-resistance-crisis.

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; Johnson, S.C. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, D; et al. Bacterial etiology of bloodstream infections and antimicrobial resistance in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2005–2014. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control 2017, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan MJ, Hosen MS, Bachar SC. The resistance growing trend of common gram-negative bacteria to the potential antibiotics over three consecutive years: a single center experience in Bangladesh. Pharm PharmacolInt J. 2019, 7, 114–9. [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species Isolated in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Sylhet 2018 Volume 30 Number 02 Rahman MM, Chowdhury OA , Hoque MM , Hoque SA , Chowdhury SMR , Rahman MA. 2018 Volume 30 Number 02.

- Deen J, et al. Community-acquired bacterial bloodstream infections in developing countries in south and southeast Asia: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012, 12, 480–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholaus, P; et al. Antibiotic Susceptibility Patterns of Bacterial Isolates from Routine Clinical Specimens from Referral Hospitals in Tanzania: A Prospective Hospital-Based Observational Study. Infection and Drug Resistance 2021, 14, 869–878. [Google Scholar]

- Anteneh, Amsalu; et al. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacterial isolates from different clinical specimens in Southern Ethiopia. African Journal of Bacteriology Research: A three year retrospective study 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zenebe T, Kannan S, Yilma D, Beyene G Invasive bacterial pathogens and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns In Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2011, 21, 1.

- Mulu et al. Bacterial agents and antibiotic resistance profiles of infections from different sites that occurred among patients at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2017, 10, 254. [Google Scholar]

- Wafa F., S. Badulla, 1 Mohammed Alshakka,2 and Mohamed Izham Mohamed Ibrahim 3 Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles for Different Isolates in Aden, Yemen: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Resource-Poor Setting. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020, 1810290, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann-Struzek, C.; Goldfarb, D.M.; Schlattmann, P.; Schlapbach, L.J.; Reinhart, K.; Kissoon, N. +e global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review. 3e Lancet Sputum Medicine 2018, 6, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Antibiotic resistance pattern of microorganisms causing urinary tract infection: a 10-year comparative analysis in a tertiary care hospital of Bangladesh. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 2022, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashe, F.; Mulisa, E.; Mekonnen, M.; Zeleke, G. Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of Different Clinical Isolates against Third- Generation Cephalosporins. Journal of Pharmaceutics 2018, 5070742, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mhada, T.V.; Fredrick, F.; Matee, M.I.; Massawe, A. Neonatal sepsis at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; aetiology, antimicrobial sensitivity pattern and clinical outcome. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 904. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, F.; Parhiz, S.; Azimi, L. Distribution and antibiotic resistance pattern of bacteria isolated from patients with community-acquired urinary tract infections in Iran: a crosssectional study. International Journal of Health Studies 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Haque R, Akter LM, Salam AM. Prevalence and susceptibility of uropathogens: a recent report from a teaching hospital in Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes. 2015, 8, 416. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari A, Sagar V. Antibiotic resistance in pathogens causing community-acquired urinary tract infections in India: a multicenter study. [Abstract] J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008, 2, 354–358, 30. Sharifian M, Karimi A, Rafiee-Tabatabaei S, Anvaripour N. Microbial Sensitivity Pattern in Urinary Tract Infections in Children: A Single Center Experience of 1177 Urine Cultures. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006; 59: 380-2.. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifian M, Karimi A, Rafiee-Tabatabaei S, Anvaripour N. Microbial Sensitivity Pattern in Urinary Tract Infections in Children: A Single Center Experience of 1177 Urine Cultures. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006, 59, 380–2. [Google Scholar]

- R. Nikoo, A. A. Hadi, and J. Mardaneh, Systematic review of antimicrobial resistance of clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Iran: an update. Microbial Drug Resistance 2017, 23, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka et al. Susceptibility pattern of Salmonella enterica against commonly prescribed antibiotics, to febrile-pediatric cases, in low-income countries. BMC Pediatrics 2021, 21, 38.

- Sattar et al. Current trends in antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Salmonella typhi and paratyphi. Rawal Medical Journal 2020, 45.

- Sharma, P; et al. Azithromycin resistance mechanisms in typhoidal salmonellae in India: A 25 years analysis. Indian J Med Res. 2019, 149, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wangai FK, Masika MM, Maritim MC, Seaton RA. Methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in East Africa: red alert or red herring. BMC Infect Dis. 2019, 19, 596, 32. Garoy EY, Gebreab YB, Achila OO, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): prevalence and Antimicrobial Sensitivity Pattern among Patients - A Multicenter Study in Asmara, Eritrea. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2019; 10.1155/2019/8321834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abdel Rahim KA, Ali Mohamed AM. Prevalence of Extended Spectrum -lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Clinical Isolates. Jundishapur J Microboil. 2014, 7, 1-5. 26. Varaiya AY, Dogra JD, Kulkarni MH, Bhalekar PN. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in diabetic foot infections. Indian J PatholMicrobiol. 2008, 51, 370–2. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrin M, Bhuiyan M, Begum MF, Karim R, Bacteriological profile and Antimicrobial susceptibility Patterns of blood culture Isolates in a Referral Hospital. Journal of UttaraAdhunik Medical College 2018, 8, 11–12.

- Begum MF, Nasrin M, Karim R, Alam Shah, Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of wound infections at Uttara Adhunik Medical College Hospital. Bangladesh J Med Microbiol 2020, 14, 15–19.

- Karuna T, Gupta A, Vyas A, et al. Changing Trends in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Bloodstream Infection (BSI) in Secondary Care Hospitals of India. Cureus 2023, 15, e37800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewodie Haile. HylemariamMihiretieMengist,TebelayDilnessa,Bacterial isolates, their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern, and associated factors of external ocular infections among patients attending eye clinic at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0277230. [Google Scholar]

- Standard Treatment Guidelines on Antibiotic Use in Common Infectious Diseases of Bangladesh,Version1,CDC,DGHS; Website. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=stgapp.cdc.gov.bd (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Laizu, J.; Parvin, R.; Sultana, N.; Ahmed, M.; Sharmin, R.; Sharmin, Z.R. , et al. Prescribing Practice of Antibiotics for Outpatients in Bangladesh: Rationality Analysis. Am J Pharmacol. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid M et al, Pattern of Antibiotic Use among Hospitalized Patients according to WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) Classification: Findings from a Point Prevalence Survey in Bangladesh. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 810. [CrossRef]

- Saha S et al Enteric Fever and Related Contextual Factors in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018, 99 (Suppl. 3), 20–25. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency N= 4,232 | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1,937 | 45.77 |

| Female | 2,295 | 54.22 |

| Age group | ||

| <1 | 68 | 1.60 |

| 1-4 Years | 157 | 3.71 |

| 5-14 Years | 452 | 10.68 |

| 15-24 Years | 820 | 19.37 |

| 25-34 Years | 603 | 14.25 |

| 35-44 Years | 403 | 9.52 |

| 45-54 Years | 442 | 10.44 |

| 55-69 Years | 768 | 18.15 |

| 70+ Years | 519 | 12.26 |

| Age category | ||

| Adult | 3,253 | 76.86 |

| Pediatric | 979 | 23.13 |

| Yearly AST | ||

| 2017 | 1,063 | 25.12 |

| 2018 | 1,620 | 38.28 |

| 2019 | 1,549 | 36.60 |

| Location type | ||

| Inpatient | 1,971 | 46.57 |

| Outpatient | 2,261 | 53.43 |

| Department | ||

| Medicine | 3,315 | 78.33 |

| Surgery | 369 | 8.72 |

| Intensive Care Unit | 210 | 4.96 |

| Pediatrics | 153 | 3.62 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 73 | 1.72 |

| Neonatal | 67 | 1.58 |

| Coronary Care Unit | 33 | 0.78 |

| Orthopedic | 10 | 0.24 |

| Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | 2 | 0.04 |

| Specimen type | ||

| Urine | 2009 | 47.47 |

| Blood | 1500 | 35.44 |

| Wound swab/pus | 426 | 10.06 |

| Sputum | 225 | 2.36 |

| Stool | 44 | 1.04 |

| Genital | 22 | 0.52 |

| Other | 6 | 0.14 |

| Antibiotics/ Organisms | Gram Negative organism | Gram Positive organism | ||||||

| E. coli (%) | Klebsiella sp. (%) | Enterobacterus sp. (%) | Pseudomonas sp. (%) | Acinetobacter sp. (%) | Salmonella sp. (%) | S. aureus (%) | Enterococcus sp. (%) | |

| Amikacin | 5.06 (76/1501) | 19.79 (94/475) | 22.92 (33/144) | 33.33 (34/102) | 53.73 (36/67) | - | - | - |

| Amoxicillin / Clavulanic acid | 71.49 (1096/1533) | 65.91 (319/484) | - | - | - | |||

| Ampicillin | - | - | - | - | - | 26.77 (166/620) | - | - |

| Azithromycin | - | - | - | - | - | 85.21 (1158/1359) | 69.01 (118/171) | - |

| Aztreonam | 62.11 (900/1449) | 56.37 (261/463) | 62.24 (89/143) | 60.40 (61/101) | - | - | - | |

| Cefepime | 58.06 (72/124) | 61.47 (67/109) | 46.15 (18/39) | 18.03 (11/61) | 75.76 (25/33) | - | - | - |

| Cefixime | 65.08 (1014/1558) | 58.59 (283/483) | 64.90 (98/151) | 90.77 (59/65) | - | - | - | |

| Cloxacillin | - | - | - | - | 5.93(8/135) | - | ||

| Ceftazidime | - | 57.82 (85/147) | 52.04 (51/98) | 74.24 (49/66) | - | - | - | |

| Ceftriaxone | 60.25 (929/1542) | 55.46 (264/476) | 54.97 (83/151) | 80.30 (53/66) | 0.29 (4/1361) | - | - | |

| Cefuroxime | 64.17 (908/1415) | 60.26 (282/468) | 63.89 (92/144) | 81.54 (53/65) | - | - | ||

| Chloramphenicol | - | - | - | - | - | 17.2 (232/1349) | - | - |

| Ciprofloxacin | 54.37 (846/1556) | 40.75 (196/481) | 44.74 (68/152) | 39.42 (41/104) | 57.58 (38/66) | 26.59 (360/1354) | 50.87 (88/173) | 49.29 (69/140) |

| Gentamicin | 17.87 (272/1522) | 24.90 (119/478) | 33.11 (50/151) | 37.00 (37/100) |

56.06 (37/66) | - | 2.98 (5/168) | 58.91 (76/129) |

| Levofloxacin | 52.86 (803/1519) | 34.86 (167/479) | 32.88 (48/146) | 38.61 (39/101) | 51.56 (33/64) | - | - | - |

| Mecillinam (Amdinocillin) | 21.92 (294/1341) | - | 39.71 (27/68) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Meropenem | 1.47 (22/1497) | 15.43 (73/473) | 9.03 (13/144) |

21.36 (22/103) | 46.15 (30/65) | - | - | - |

| Netilmicin | 7.92 (118/1490) | 22.80 (106/465) | 24.49 (36/147) | 29.00 (29/100) | 38.81 (26/67) | - | - | - |

| Nitrofurantoin | 12.76 (168/1317) | 34.01 (100/294) | 41.18 (28/68) | - | - | - | - | 10.37 (14/135) |

| Penicillin | - | - | - | - | - | 78.79 (104/132) | - | |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 56.13 (142/253) | 70.09 (75/107) | 37.14 (13/35) | 4.35 (4/92) | - | - | - | - |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | 50.80 761/1498 |

54.76 253/462 |

42.96 58/135 |

60.94 39/64 |

18.88 (253/1340) | 20.47 (35/171) | 42.96 (58/135) | |

| Vancomycin | - | - | - | - | - | 1.18 (2/169) | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).