Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

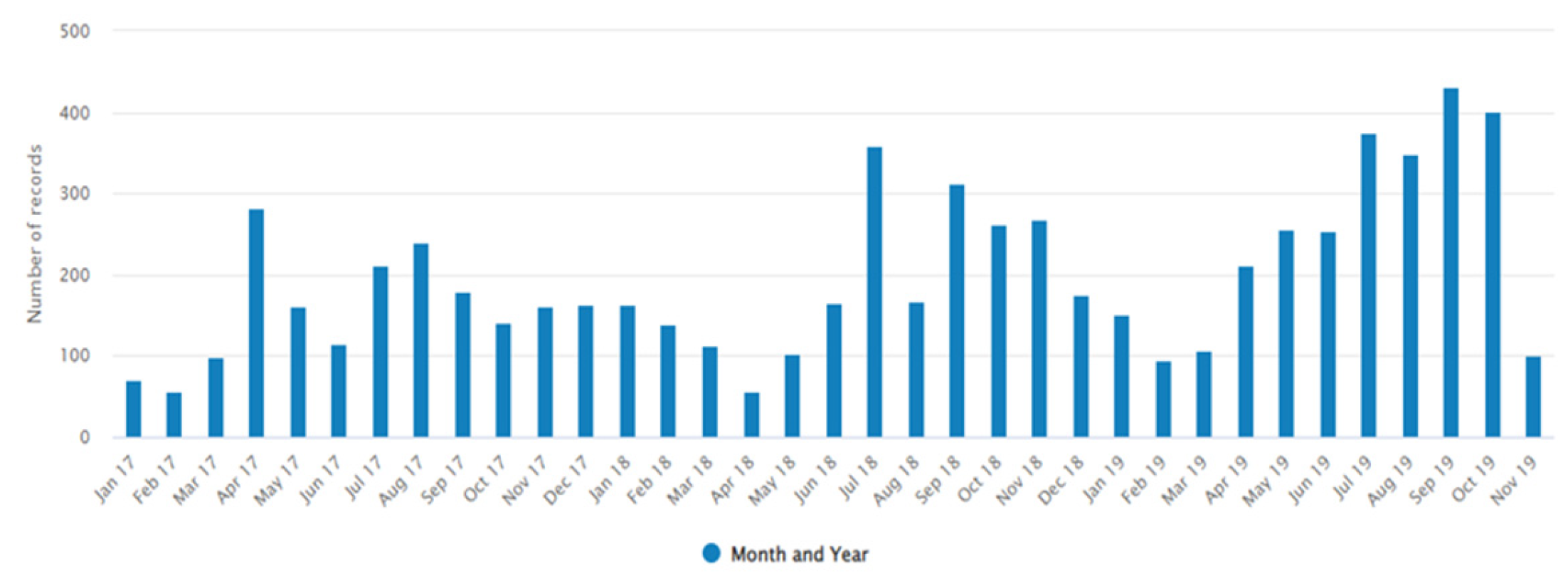

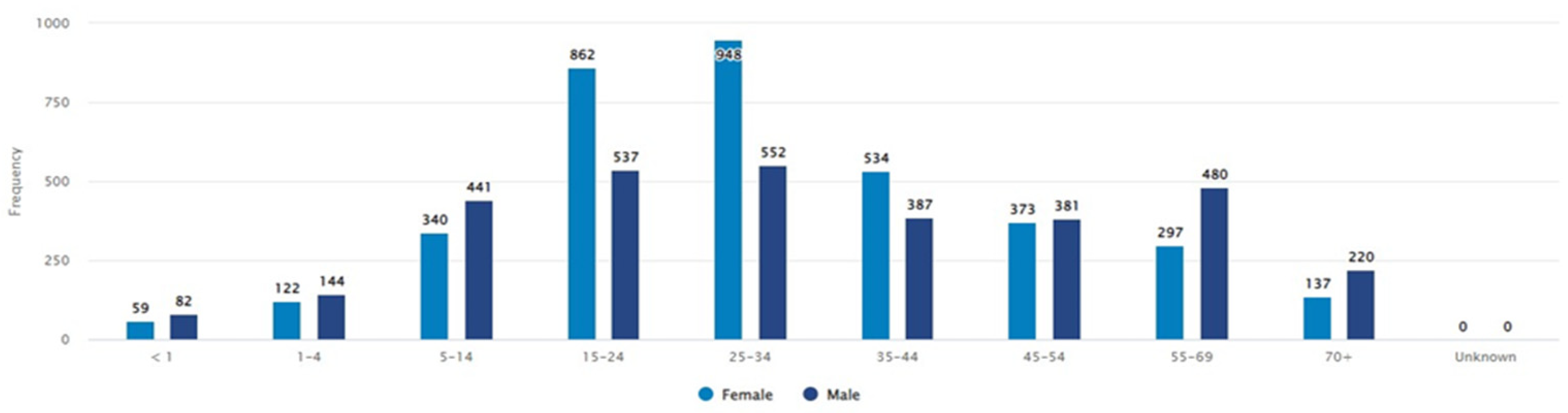

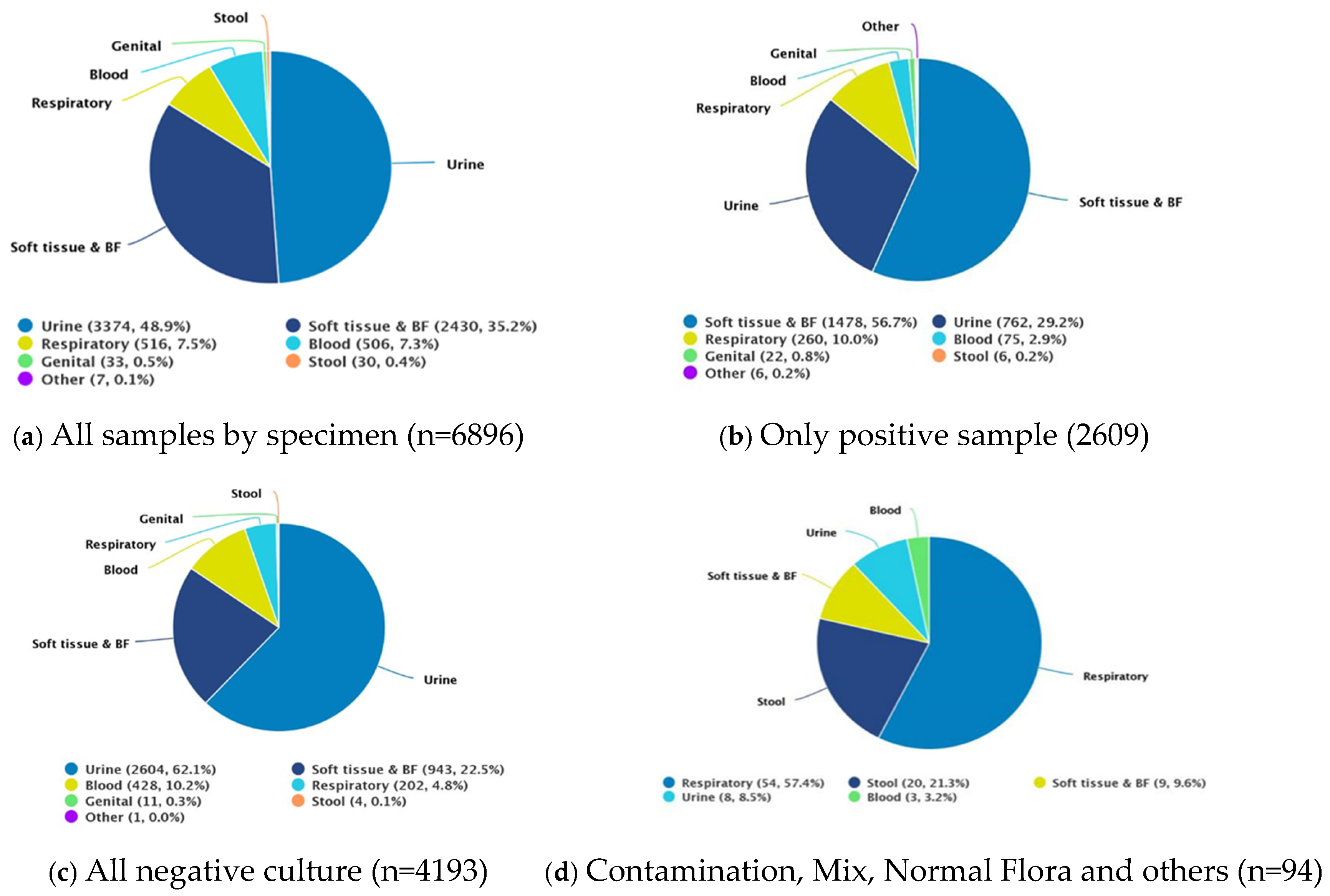

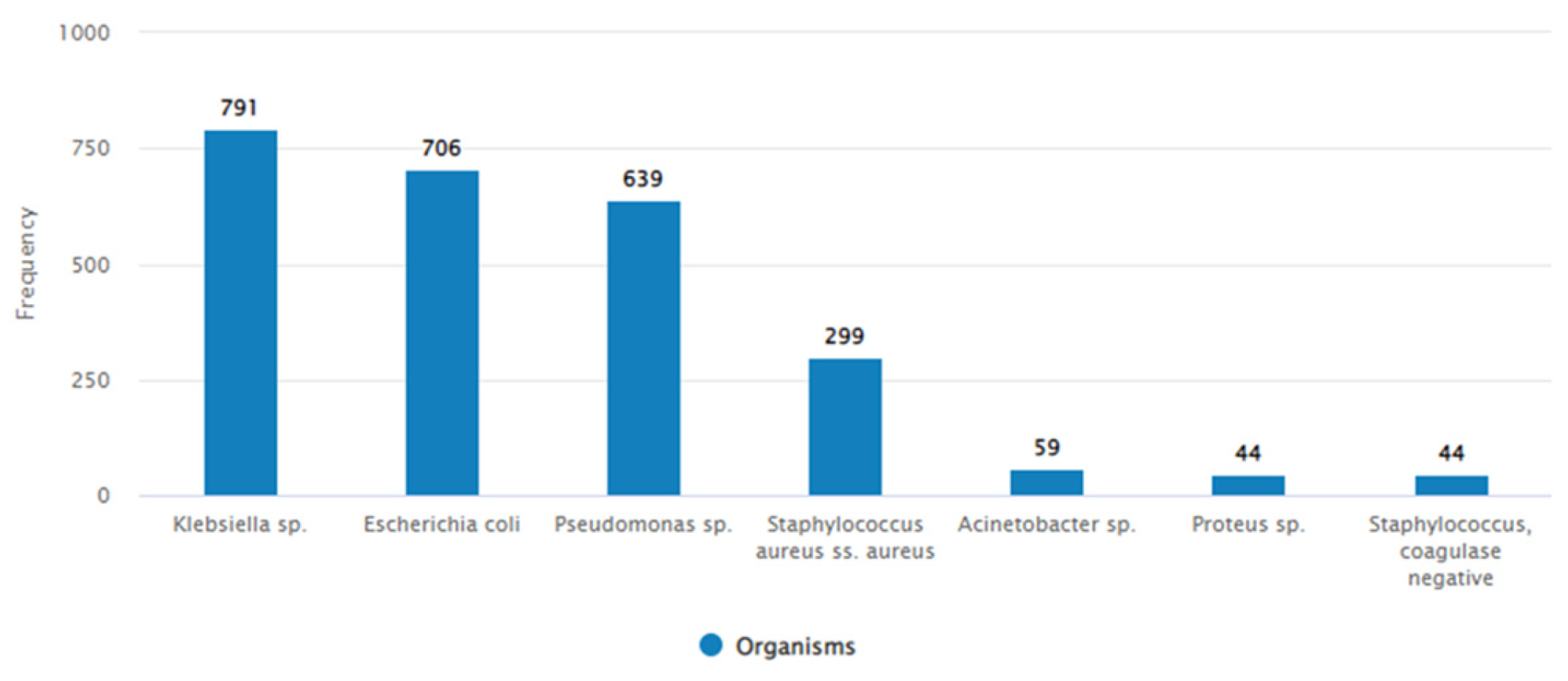

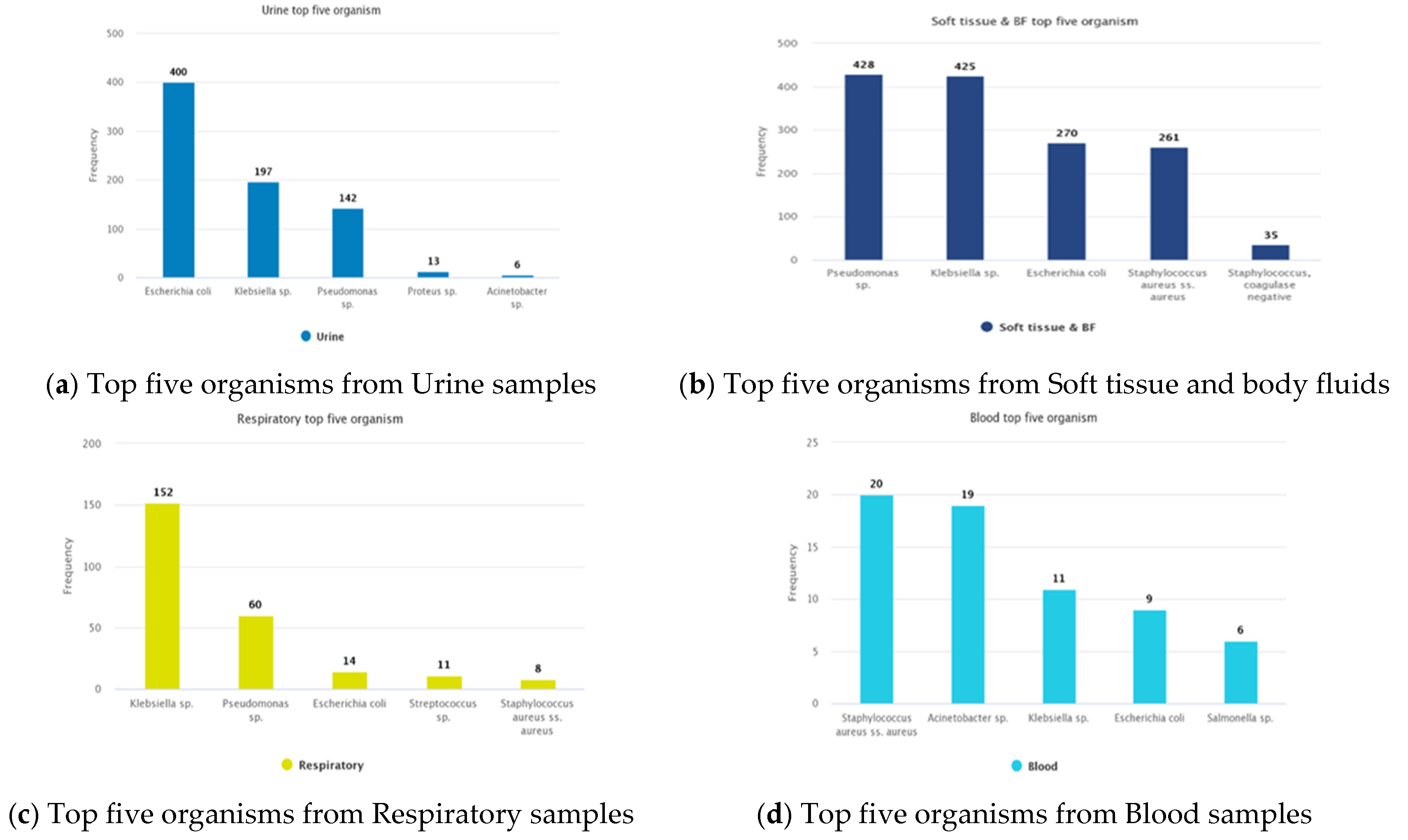

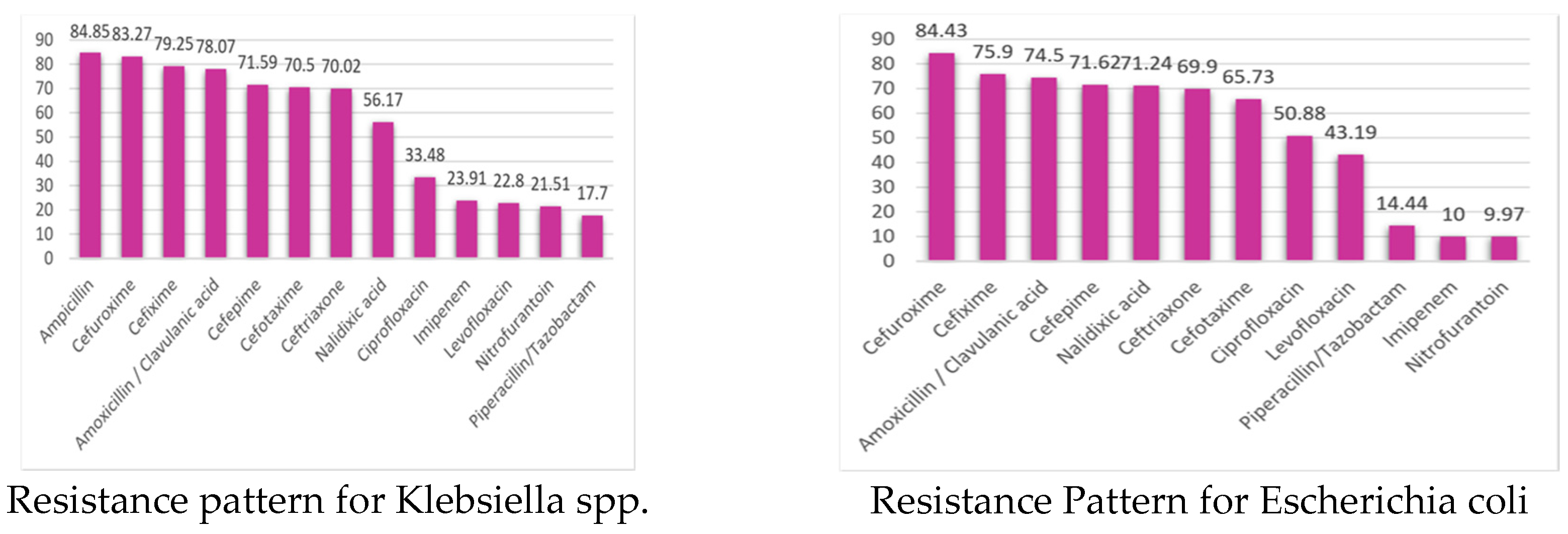

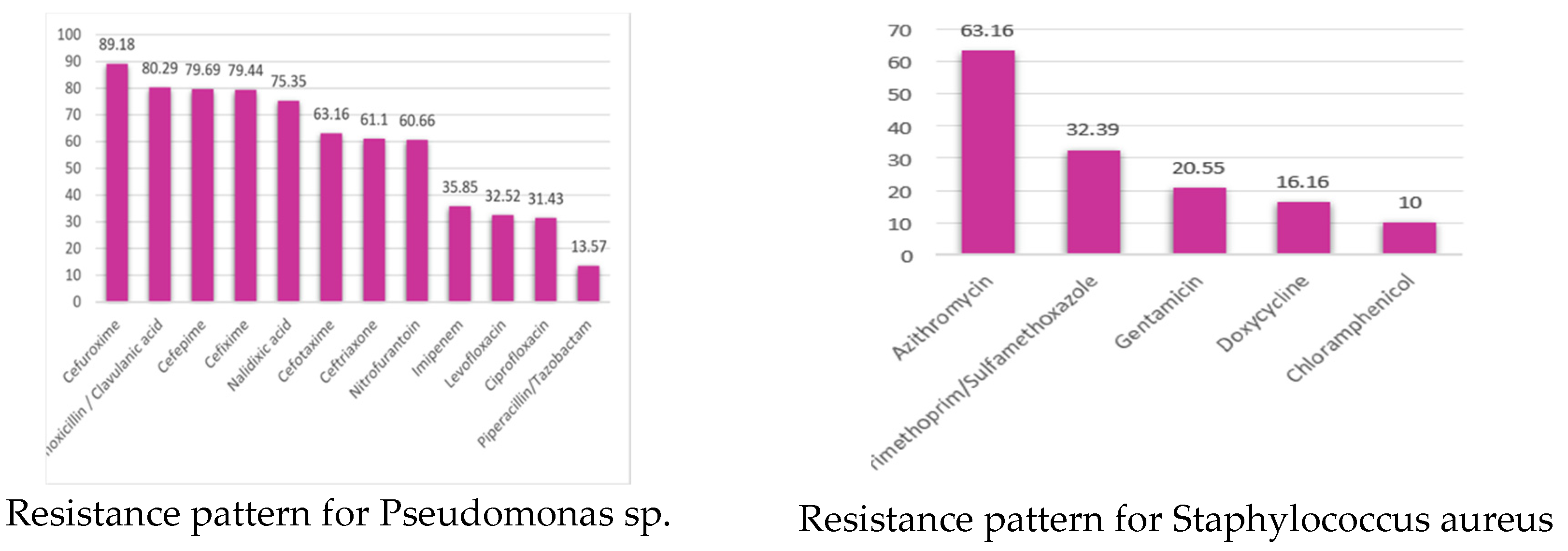

Background: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a pressing global health concern, leading to increased treatment costs, prolonged hospital stays, and higher mortality rates. This study analyzes the prevalence and trends of AMR in pathogenic bacteria isolated from various clinical specimens from Chattogram Medical College Hospital (CMCH) in Chittagong, Bangladesh. The objective is to track AMR over an extended period and provide comparative analytics for local and global surveillance efforts. Methods: Retrospective data from June 2017 to November 2019 were collected from a tertiary care hospital, en-compassing both inpatients and outpatients. Bacterial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing followed standard methods. WHONET and Quick Analysis of AMR Patterns and Trends (QAAPT) software were utilized for data management and analysis. Results: The analysis included 6,896 records, with an average bacterial growth positivity rate of 39%. The most common specimen type was urine, accounting for 48.9% of all specimens. Among the bacterial isolates, variations in AMR prevalence were observed, particularly with E. coli displaying high resistance to commonly used antibiotics. Soft tissue and blood fluid samples exhibited a high positivity rate for bacterial growth. The study underscores the urgent need for AMR surveillance and evidence-based treatment guidelines tailored to local antibiotic susceptibility patterns. Conclusion: This study highlights the significance of monitoring AMR trends in Chittagong, Bangladesh. By understanding and addressing AMR patterns, policymakers, and stakeholders can develop informed national policies and strategies to combat AMR effectively. Sharing these findings with relevant parties is crucial for creating awareness and promoting evidence-based practices. The study emphasizes the importance of ongoing surveillance efforts and the development of targeted interventions to mitigate the impact of AMR and improve patient outcomes in the region.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

Data Collection

Microbiological Testing

Statistical Analysis

Ethical and Project Approval

3. Results

3.1. Demography and Bacterial Culture

3.1.1. Isolated Bacteria and Their Resistance Pattern

3.1.2. Resistant Pattern of Isolated Bacteria

3.1.3. Drug Resistance Pattern (MDR, XDR, and PDR Categorization of Clinical Isolates)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMCH | Chittagong Medical College Hospital, Chattogram |

| CAPTURA | Capturing Data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia |

| IEDCR | Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control & Research |

| CDC | Communicable Disease Control |

| MoHFW | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

| QAAPT | Quick Analysis of Antimicrobial Patterns and Trends |

| CLSI | Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute |

| EUCAST | European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| PDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- WHO Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance Date: 2021 Date accessed: April 19, 2023.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022; 399(10325):P629-655. Epub 2022 Jan 19. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 1;400(10358):1102. PMID: 35065702; PMCID: PMC8841637. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, London 2016 Available at:https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf. Accessed on 20 January 2021.

- Laxminarayan, R; Heymann, DL (2012) Challenges of drug resistance in the developing world. BMJ (Clinical research ed), 344. e1567. ISSN 0959-8138. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad et al. (2016), ′ Public Health problems in Bangladesh’ South East Asia Journal of Public Health 2016;6(2):11-16. [CrossRef]

- Hossain MM, Barman AA, Rahim MM, Hassan MT, Begum M, Bhattacharjee D.(2018) Oxytetracycline residues in Thai pangas Pangasianodon hypophthalmus sampled from Sylhet sadar upazila, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Zoology. 2018. July 26;46(1):81–90. [CrossRef]

- Islam A, Saifuddin A, Al Faruq A, Islam S, Shano S, Alam M, et al. Antimicrobial residues in tissues and eggs of laying hens at Chittagong, Bangladesh. Int J One Health. 2016;2(11):75–80. [CrossRef]

- Rana MM, Karim MR, Islam MR, Mondal MNI, Wadood MA, Bakar SMA et al. Knowledge and Practice about the Rational Use of Antibiotic among the Rural Adults in Rajshahi District, Bangladesh: A Community Clinic Based Study. Human Biology Review 2018;7 (3):259–271.

- Saha T, Saha T. Awareness Level of Patients Regarding usage of Antibiotics in a Slum Area of Dhaka City, Bangladesh. SSRG Int J Med Science 2018;5(9):10–16.

- Haque MU, Kumar A, Barik SMA and Islam MAU. Prevalence, practice and irrationality of self-medicated antibiotics among people in northern and southern region of Bangladesh. Int J Res Pharm Biosciences 2017;4(10): 17–24.

- Shamsuddin AK, Rahman MS, Sultana N, Islam MS, Shaha AK, Karim MR, et al. Current Trend of Antibiotic Practice in Paediatric Surgery in Bangladesh. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) 2019;18(4):28–32.

- Al Rasel Bin Mahabub Zaman M, Hasan M, Rashid HA. Indication-based use of antibiotic in the treatment of patients attending at the primary health care facility. Cough. 2018;44:22–0.

- Biswas M, Roy DN, Rahman MM, Islam M, Parvez GM, Haque MU et al. Doctor’s prescribing trends of antibiotics for out-patients in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional health survey conducted in three districts. Int J Pharma Sciences Res. 2015;6(2):669–75. [CrossRef]

- Nahar A, Hasnat S, Akhter H, Begum N. (2017) Evaluation of antimicrobial resistance pattern of uropathogens in a tertiary care hospital in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. South East Asia J Public Health. 2017;7(2):12–8. [CrossRef]

- Begum N, Shamsuzzaman S. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing urinary isolates at a tertiary care hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Tzu Chi Medical Journal. 2016; 28(3):94–8. 10.1016/j.tcmj.2016.04.005. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury S., Parial R. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of bacteria among urinary tract infection patients in Chittagong, Bangladesh. SMU Med J, 2 (1) (2015), pp. 114-127.

- Nusrat, Tanzina and Akter, Nasima and Rahman, Nor Azlina A and Godman, Brian and Rozario, Diana Thecla D. and Haque, Mainul (2020) Antibiotic resistance and sensitivity pattern of Metallo-β-Lactamase producing gram-negative Bacilli in ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit of a public medical school hospital in Bangladesh. Hospital Practice, 48 (3). pp. 128-136. ISSN 2377-1003. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad , A. K., Nasir, M., Paul, S., Rahman, H., Abul, K., & Ahmed, F. U. (2020). Common Pathogens and Their Resistance to Antimicrobials in Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP): A Single Center Study in Bangladesh. International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Invention, 7(12), 5144–5153. [CrossRef]

- Tanni AA, Hasan MM, Sultana N, Ahmed W, Mannan A (2021) Prevalence and molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance and associated genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: A clinical observational study in different hospitals in Chattogram, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0257419. [CrossRef]

- Capturing Data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia (CAPTURA). https://captura.ivi.int.

- WHONET. Boston, MA, USA. https://whonet.org.

- Sujan MJ, Gautam S, Aboushady AT, Clark A, Kwon S, Joh HS, Holm M, Stelling J, Marks F and Poudyal N (2025) QAAPT: an interoperable web-based open-source tool for antimicrobial resistance data analysis and visualisation. Front. Microbiol. 16:1513454. [CrossRef]

- Rahman MS, Huda S. Antimicrobial resistance and related issues: An overview of Bangladesh situation. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. 2014; 9 (2):218–24. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed I, Rabbi MB, Sultana S. Antibiotic resistance in Bangladesh: A systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;80:54-61. [CrossRef]

- Barai, L., Saha, M. R., Rahman, T., Khandaker, T., Dutta, S., Hasan, R., & Haq, J. A. (2018). Antibiotic Resistance: Situation Analysis In a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Microbiology, 34(1), 15–19. Retrieved from https://www.banglajol.info/index.php/BJM/article/view/39226.

- Santajit S, Indrawattana N. (2016) Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. BioMed research international.; 2016:2475067 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Healthcare Settings available at https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/pseudomonas.html; Last Reviewed: November 13, 2019 ; Last date of accession: 24th august, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threatsreport/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Annual report of Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network, Division of Epidemiology communicable Disease, Indian Council of Medical Research, January 2021-December 2021 [Internet] [cited 2023 May 105]. Available from: https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/upload_documents/AMR_Annual_Report_2021.pdf.

- Haque MU, Kumar A, Barik SMA and Islam MAU. Prevalence, practice and irrationality of self-medicated antibiotics among people in northern and southern region of Bangladesh. Int J Res Pharm Biosciences 2017;4(10): 17–24.

- Nishat C, Rashedul M. Prevalence of self-medication of antibiotics among people in Bangladesh. Ind J Pharma Prac. 2012;5(4):65–72.

- Paul TR, Hamid MR, Alam MS, Nishuty NL, Hossain MM, Sarker T et al. Prescription Pattern and Use of Antibiotics Among Pediatric Out Patients in Rajshahi City of Bangladesh. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2018;9(9):3964–70.

- Chouduri AU, Biswas M, Haque MU, Arman MS, Uddin N, Kona N, et al. Cephalosporin-3G, Highly Prescribed Antibiotic to Outpatients in Rajshahi, Bangladesh: Prescription Errors, Carelessness, Irrational Uses are the Triggering Causes of Antibiotic Resistance. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2018;8(06):105–12. [CrossRef]

- Sayeed MA, Iqbal N, Ali MS, Rahman MM, Islam MR, Jakaria M.2015 Survey on Antibiotic Practices in Chittagong City of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015;18(2):174–8. [CrossRef]

- Begum MM, Uddin MS, Rahman MS, Nure MA, Saha RR, Begum T, et al. (2017) Analysis of prescription pattern of antibiotic drugs on patients suffering from ENT infection within Dhaka Metropolis, Bangladesh. Int J Basic Clinic Pharmacology. 2017;6(2):257–64. [CrossRef]

- Deepti Rawat,Deepthi Nair, 2010.Extended-spectrum-lactamases in Gram negative bacteria. J. Global Infect. Dis., 2010 Sep-Dec; 2(3): 263274. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S., Fatima, J., Shakil, S., Rizvi, S.M.D. and Kamal, M.A. (2015) Antibiotic Resistance and Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamases: Types, Epidemiology and Treatment. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 22, 90-101. [CrossRef]

- Rawat D, Nair D. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in gram negative bacteria. J Glob Infect Dis.2010; 2(3): 263–74. [CrossRef]

- Rahman MM, Haq JA, Hossain MA, Sultana R, Islam F and Islam AHMS. 2004. Prevalence of extended-spectrum- b lactamase-producing Escherechia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in an urban hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int J Antimic Agents. 24:508-510. [CrossRef]

- Lutgring J. D. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging bacterial threat. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology . 2019;36(3):182–186. [CrossRef]

- Begum N, Shamsuzzaman S. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing urinary isolates at a tertiary care hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Tzu Chi MedJ. 2016;28(3):94–98. [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, D., Panda, S. S., Singh, N., Sahoo, S., Mohapatra, I., & Jena, J. (2019). Multidrug resistant, extensively drug resistant and pan drug resistant gram negative bacteria at a tertiary care centre in Bhubaneswar. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health, 6(2), 567–572. [CrossRef]

- Hadeel Alkofide, Abdullah M Alhammad, Alya Alruwaili, Ahmed Aldemerdash, Thamer A Almangour, Aseel Alsuwayegh, Daad Almoqbel, Aljohara Albati, Aljohara Alsaud & Mushira Enani (2020) Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Prevalence, Treatments, and Outcomes—A Retrospective Cohort Study, Infection and Drug Resistance, , 4653-4662. [CrossRef]

- Gupta V., Gang Yea , Melanie Oleskyb , Kenneth Lawrenceb , John Murraya , Kalvin Yua (2019) National prevalence estimates for resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter species in hospitalized patients in the United States, International Journal of Infectious Diseases 85 (2019) 203–211. [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, K., Saha, A., Huda, N. H., & Uddin, R. (2014). Irrational Use of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Southern Rural Bangladesh: Perspectives from Both the Physicians and Patients. Annual Research & Review in Biology, 4(9), 1421-1430. [CrossRef]

- Musa K, Okoliegbe I, Abdalaziz T, Aboushady AT, Stelling J, Gould IM. Laboratory Surveillance, Quality Management, and Its Role in Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance in Africa: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Aug 14;12(8):1313. [CrossRef]

| Organism | Number of isolates | MDR | Possible XDR | Possible PDR |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 299 | 187 (63%) | 70 (23%) | - |

| Escherichia coli | 706 | 432 (61%) | 398 (56%) | 80 (11%) |

| Acinetobacter sp. | 59 | 26 (44%) | 26 (44%) | 1 (2%) |

| Klebsiella sp. | 791 | 496 (63%) | 450 (57%) | 54 (7%) |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 369 | 93 (25%) | 93 (25%) | 38 (!0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).