1. Introduction

Sir Alexander Fleming's ground-breaking discovery of penicillin in 1928 marked the beginning of the antibiotic revolution, which fundamentally altered the direction of contemporary medicine [

1]. Antibiotics have successfully increased life span and are currently most often prescribed drugs in hospitals around the world [

2]. However, the rising resistance to antibiotics is alarming. The high prevalence of infectious diseases, the absence of adequate guidelines for the therapy of infections and facilities for infection control [

3], and the irrational prescribing, dispensing, and administration of antibiotics [

4] primarily contribute towards the rapid development of antibiotic resistance worldwide. Moreover, due to the cumbersome diagnostic process, antimicrobial drugs are occasionally started empirically, which may facilitate the emergence of drug resistant strains of bacteria [

5]. For instance, in Africa, treatment recommendations for infections rely heavily on the use of empiric antibiotics without the support of culture results [

6]. Antibiotic resistance causes a rise in morbidity, mortality, hospital stay time, and medical costs [

7]. Controlling AMR requires routine observation of the pathogenic organisms and their antibiotic susceptibility profile [

8]. The AMR surveillance data will guide physicians for judicious selection of antibiotics, inform the policy resulting in improved patient care [

9]. However, the majority of healthcare providers lack current antimicrobial resistance (AMR) data [

10]. This data is needed to institutions and hospitals to formulate relevant policies and ensure best prescription practices [

11].

The Capturing Data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia (CAPTURA) initiative, funded by the Fleming Fund Regional Grants and led by the International Vaccine Institute (IVI), aimed to significantly increase the volume of available AMR (Antimicrobial Resistance), AMC (Antimicrobial Consumption), and AMU (Antimicrobial Use) data for informed decision-making as well as assess the quality of datasets and laboratories. By collaborating with local governments and both private and public healthcare facilities, the initiative identified and assessed data that were often unused, evaluating them for quality and availability. Relevant data were then shared with CAPTURA, where they were collated and analyzed to provide insights at local, regional, and interregional levels.

This study was conducted at Bangladesh Specialized Hospital (BSH), a tertiary level hospital in Dhaka, to evaluate the microbiological profile of various bacterial infections and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns with the technical support from the CAPTURA project. The findings guide future initiatives in encouraging awareness, policy, and interventions to combat the urgent global threats of spreading AMR and antimicrobial misuse.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design and place

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Bangladesh Specialized Hospital (BSH), a tertiary care hospital in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. The current study utilized a retrospective descriptive research approach where culture results of specimens of blood, genital, respiratory, soft tissue and body fluids, stool and urine at the Microbiology Department in BSH were retrieved were analysed for the period between January 2018 and February 2021 in which.

Data collection and processing

A total of 26,825 samples were included in the study. Data related to demographics (age and gender), type of specimens, type of microorganism, and antibiotic sensitivity/resistance pattern were retrieved from both paper and electronic data recording systemthe medical records. For bacterial isolation, identification and drugs susceptibility testing, samples were collected, processed, and cultured following standard techniques used in medical microbiology laboratory. For pathogen identification, colonies formed were further processed using morphology, Gram staining, and biochemical tests. Antibiotic susceptibility testing of bacterial isolates was performed using the Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method and observations were interpreted in accordance with guidelines set by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (CLSI). Due to resource limitation, fastidious bacteria and any species requiring complex nutritional components and specialized detection methods were not included in the routine clinical laboratory diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied to the collected data using WHONET and Quick Analysis of Antimicrobial Patterns and Trends (QAAPT) software. Results are expressed in frequency distributions and antibiograms.

3. Results

3.1. Demography and bacterial culture

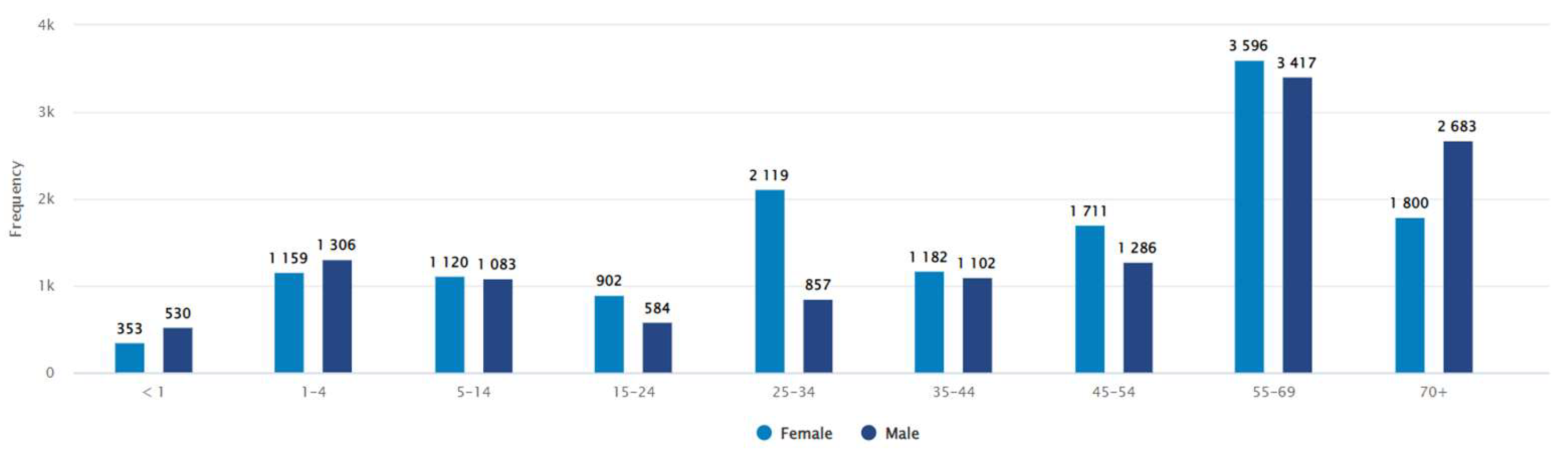

Between January 2018 - February 2021, a total of 26,825 clinical specimens were processed for culture and identification. Bacterial growth was detected in 14% (n = 3779) of the samples. The patient demography showed approximately equal distribution of bacterial infections in both sexes (female and male, 52% and 48% respectively). In term of age distribution, the median age group for male was 45-54 years, while for female this remained 35-44 years (

Figure 1).

The specimen distribution showed urine as the commonest specimen (48.7%) collected for bacterial culture followed by blood (27.1%) and soft tissue and body fluid (8.1%). The culture positivity rate for urine, blood and soft tissue and body fluid was 41%, 24% and 15% respectively (

Table 1). All sample types of

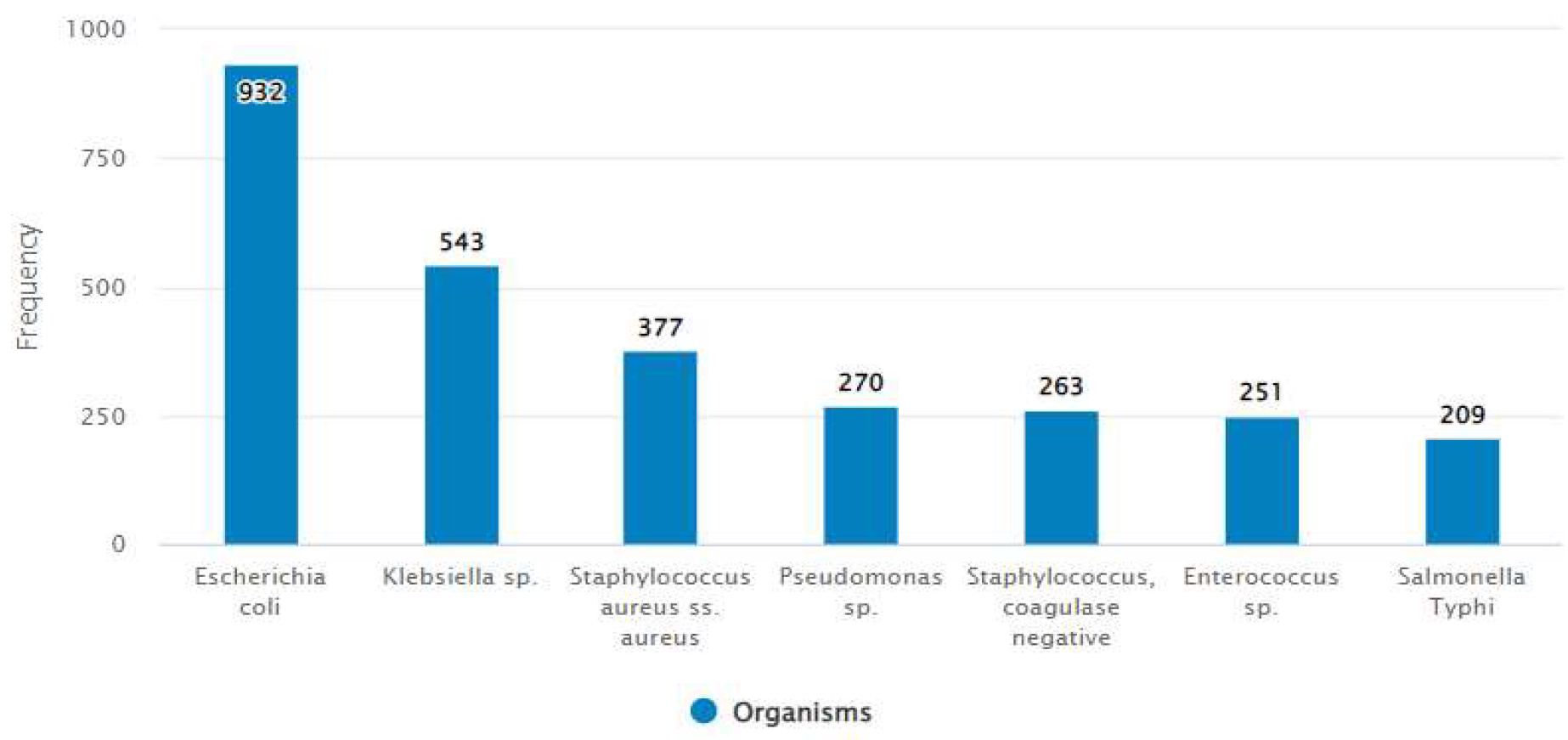

Escherichia coli,

Klebsiella sp.,

Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas sp., coagulase negative Staphylococcus, Salmonella Typhi and

Enterococcus sp. were common pathogens (

Figure 2). A detailed distribution of microorganisms in different specimens is presented in

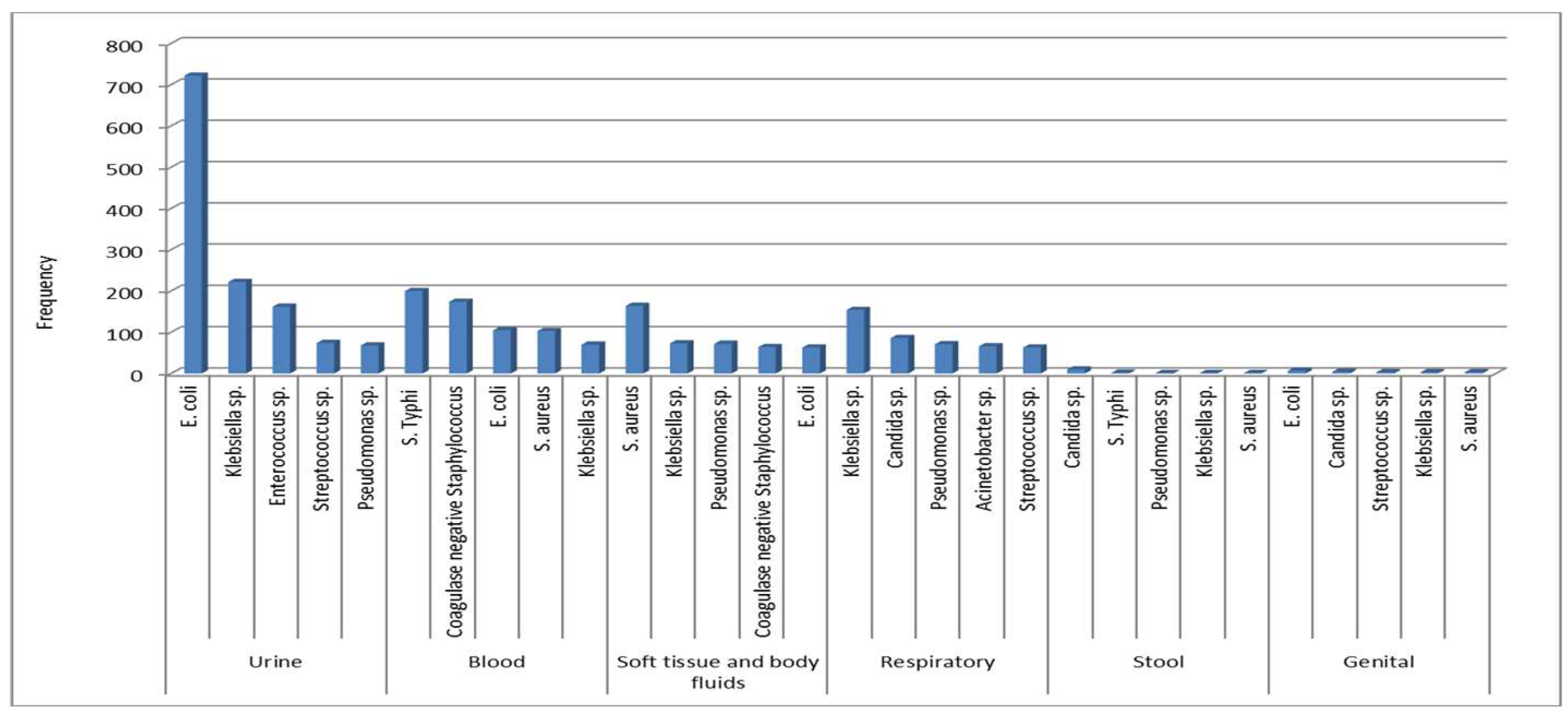

Figure 3. Overall,

E. coli was predominant in urine and genital tract samples,

Salmonella Typhi in blood,

Staphylococcus aureus from soft tissue and body fluids, and

Klebsiella sp. from the respiratory tract.

3.1.1. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern

A thorough overview of antibiotic sensitivity pattern of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are depicted in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

E. coli, the most common causative organism of Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) and genital infection, showed high resistance to co-trimoxazole (48%), ciprofloxacin (79%) and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (65%) though nitrofurantoin and mecillinam were observed highly susceptible with resistant rate of only 7% and 16% respectively. Resistance of

E. coli to third generation cephalosporin such as cefotaxime, ceftazidime and ceftriaxone was 63%, 64% and 63% respectively. However, resistance to amikacin and meropenem was 7% and 8% respectively in

E. coli. In systemic infection, the principal microorganism found was

Salmonella Typhi. High sensitivity towards amoxicillin (100%), chloramphenicol (78%), co-trimoxazole (76%), cefixime (100%) and ceftriaxone (100%) were seen in

Salmonella Typhi whereas almost all isolates were resistant to nalidixic acid (97%) and ciprofloxacin (96%).

Staphylococcus aureus, the predominant cause of soft tissue infection, was highly sensitive to recommended drugs for uncomplicated soft tissue infection such as co-trimoxazole (70%) and doxycycline (86%), and for complicated infection vancomycin (99%) and linezolid (97%). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was detected by testing susceptibility to cefoxitin, with 54% isolates found to be MRSA. The most common cause of respiratory infection was

Klebsiella sp.

Klebsiella sp. was the most commonly tested pathogen in patients with respiratory infectionThe rate of resistance of

Klebsiella pneumoniae to third generation cephalosporin such as cefixime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone and fourth generation cephalosporin like cefepime was about 65%. Though high resistance of the bacteria to ciprofloxacin (74%) and meropenem (42%) was documented, colistin was 100% sensitive to

Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Pseudomonas sp., commonly tested in urine, soft tissue and body fluids, and respiratory infections, were susceptible to ceftazidime, piperacillin/tazobactam and ciprofloxacin with resistance rate of 27%, 18% and 34% respectively. High resistance to meropenem was recorded in

Pseudomonas sp. isolates (26%) and

Acinetobacter sp. (64%).

Acinetobacter sp. showed low sensitivity (< 45%) to all of the tested antibiotics except colistin and tigecycline.

Enterococcus sp., recorded commonly from urine sample, was sensitive to amoxicillin (72%) and nitrofurantoin (74%) while low sensitivity was exhibited to ceftriaxone (30%), amikacin (25%) and ciprofloxacin (15%). Moreover, 1% vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and 2% linezolid-resistant Enterococcus sp. were observed.

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

Figure 1.

Distribution of isolates according to age and sex.

Figure 1.

Distribution of isolates according to age and sex.

Figure 2.

Percentage of organisms isolated from all samples over the reported.

Figure 2.

Percentage of organisms isolated from all samples over the reported.

Figure 3.

Most common organisms by specimen category. Urine, Blood, Soft tissue and body fluids (& BF), Respiratory, Stool, and Genital.

Figure 3.

Most common organisms by specimen category. Urine, Blood, Soft tissue and body fluids (& BF), Respiratory, Stool, and Genital.

Table 1.

The number of culture records stratified by specimen category.

Table 1.

The number of culture records stratified by specimen category.

| Specimen |

All Isolates

N (%) |

Positive culture

n (%) |

Negative culture

n (%) |

| Urine |

13059 (48.7) |

1549 (41) |

11510 (49.9) |

| Blood |

7274 (27.1) |

902 (23.9) |

6372 (27.6) |

| Soft tissue and body fluids |

2160 (8.1) |

567 (15) |

1593 (6.9) |

| Respiratory |

2012 (7.5) |

645 (17.1) |

1367 (5.9) |

| Stool |

1130 (4.2) |

17 (0.4) |

1113 (4.8) |

| Genital |

218 (0.8) |

23 (0.6) |

195 (0.8) |

| Others |

972 (3.6) |

76 (2) |

896 (3.9) |

| Total |

26825 |

3779 (14.09) |

23046 (85.91) |

Table 2.

Gram positive antibiogram. The numbers indicate % susceptible.

Table 2.

Gram positive antibiogram. The numbers indicate % susceptible.

| Organism |

Number of patients* |

AMC |

AMK |

AZM |

CIP |

CLI |

CRO |

CTX |

CXM |

DOX |

FEP |

FOX |

GEN |

LNZ |

NET |

NIT |

PEN |

SXT |

TCY |

TEC |

VAN |

Staphylococcus aureus

|

366 |

46 |

90 |

20 |

36 |

55 |

|

|

42 |

86 |

46 |

46 |

73 |

97 |

96 |

|

23 |

70 |

|

99 |

99 |

Staphylococcus epidermidis

|

260 |

39 |

91 |

16 |

46 |

61 |

|

|

38 |

92 |

39 |

39 |

68 |

96 |

97 |

|

32 |

63 |

|

100 |

100 |

Enterococcus sp.

|

247 |

72 |

25 |

9 |

15 |

11 |

30 |

31 |

|

63 |

29 |

|

68 |

98 |

61 |

74 |

66 |

10 |

38 |

90 |

99 |

Streptococcus pyogenes

|

92 |

100 |

35 |

39 |

24 |

59 |

100 |

100 |

|

92 |

100 |

|

100 |

99 |

87 |

97 |

100 |

3 |

|

96 |

100 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae |

40 |

100 |

|

49 |

28 |

|

100 |

100 |

|

90 |

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

100 |

100 |

2 |

|

|

100 |

Table 3.

Gram negative antibiogram. The numbers indicate % susceptible.

Table 3.

Gram negative antibiogram. The numbers indicate % susceptible.

| Organism |

Number of patients* |

AMC |

AMK |

ATM |

AZM |

CAZ |

CFM |

CHL |

CIP |

COL |

CRB |

CRO |

CTX |

FEP |

GEN |

MEC |

MEM |

NAL |

NET |

NIT |

PEF |

SXT |

TCY |

TGC |

TOB |

TZP |

| Escherichia coli |

922 |

35 |

93 |

35 |

|

36 |

35 |

|

21 |

100 |

|

37 |

37 |

37 |

82 |

86 |

92 |

|

92 |

93 |

|

52 |

|

87 |

70 |

78 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

489 |

36 |

59 |

38 |

|

36 |

35 |

|

26 |

100 |

|

37 |

36 |

38 |

52 |

62 |

58 |

|

57 |

29 |

|

44 |

71 |

35 |

48 |

47 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

223 |

4 |

73 |

65 |

|

74 |

|

|

65 |

99 |

34 |

|

|

75 |

72 |

|

70 |

|

77 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

68 |

81 |

|

Salmonella Typhi |

209 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

96 |

100 |

100 |

78 |

3 |

100 |

|

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

100 |

3 |

100 |

|

2 |

76 |

|

|

100 |

100 |

|

Acinetobacter sp. |

181 |

4 |

34 |

5 |

|

21 |

4 |

|

40 |

94 |

|

4 |

3 |

19 |

32 |

|

36 |

|

42 |

|

|

69 |

|

92 |

33 |

44 |

|

Enterobacter sp. |

139 |

53 |

91 |

64 |

|

66 |

51 |

|

66 |

90 |

|

66 |

65 |

69 |

85 |

80 |

96 |

|

90 |

51 |

|

77 |

|

55 |

82 |

91 |

|

Proteus sp. |

53 |

74 |

82 |

79 |

|

79 |

74 |

|

28 |

2 |

|

76 |

76 |

83 |

67 |

|

98 |

|

85 |

|

|

32 |

|

50 |

75 |

94 |

|

Citrobacter freundii |

47 |

43 |

94 |

42 |

|

44 |

44 |

|

37 |

98 |

|

43 |

43 |

45 |

83 |

74 |

87 |

|

92 |

82 |

|

50 |

|

91 |

72 |

83 |

|

Pseudomonas sp. |

35 |

|

51 |

41 |

|

62 |

|

|

72 |

46 |

|

|

|

54 |

46 |

|

74 |

|

46 |

|

|

|

|

92 |

41 |

88 |

|

Salmonella Paratyphi |

21 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

100 |

4. Discussion

The overuse of antibiotics is highly associated with increased infections and costs, drug interactions, longer hospital stays, and bacterial resistance [

12]. For successful use of empirical therapy and to prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistance, frequent investigation of the local epidemiology and the often-underestimated microorganisms' antimicrobial susceptibility pattern is necessary in developing countries [

10].

In the current analysis, 3,779 microbial growths were recovered from 26,825 samples yielding a 14.09% isolation rate. The higher proportion of female patients might be due to an enormous proportion of laboratory samples often coming from UTI in women. However, when analysing the distribution of the culture records by age group, a proportionally large number of records were in the higher age group for both males and females than might be anticipated. In the context of males, and particularly if the samples are urine samples, this observation is normal as males are more prone to urinary tract infections at later stages of life. Urine was the most common and frequently testedsample for culture. The culture positivity rate of blood cultures was low. This is because the isolation rate depends on various factors including the clinical condition, ambulatory or hospitalized state, and length of hospital stay and age of patient.

E. coli was the topmost isolated organism. This correlates well with the fact that urine was the most common sample, as

E. coli was often the most frequently reported pathogen in urine cultures.

Klebsiella sp., Pseudomonas sp. and

Enterococcus sp. were frequently isolated organisms in this setting. This could be the case if the facility is providing health care to more seriously ill patients requiring longer hospitalizations and higher amounts of antimicrobials. The number of isolates of

Salmonella Typhi was also high. This finding is consistent with the fact that typhoid is endemic in Bangladesh and a large number of cases are reported every year with frequent outbreaks [

13].

In this study,

E. coli, a common cause of genitourinary tract infection, revealed high level of resistance to co-trimoxazole, ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, while nitrofurantoin and mecillinam showed susceptibility to

E. coli. A similar situation has been observed in developing countries [

14]. About two-thirds of

E. coli isolates showed resistance to third generation cephalosporin. South India reported 92% third generation cephalosporin-resistant

E. coli in 2010 [

3]. However, only 3.3% of ceftriaxone-resistant

E. coli isolates were found in Ethiopia [

15]. Resistance to amikacin and meropenem was 7% and 8% respectively in

E. coli. In south India, 12% amikacin-resistant and 16% meropenem-resistant

E. coli were reported [

3].

In systemic infections, the most common causative agent was

Salmonella Typhi, which showed high sensitivity towards amoxicillin (100%), chloramphenicol (78%), co-trimoxazole (76%), cefixime (100%) and ceftriaxone (100%) were seen in

Salmonella Typhi whereas almost all isolates were resistant to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin. The gradual upward trend in sensitivity to co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol and amoxicillin and downward trend in sensitivity to ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid have been observed through recent years [

13,

16].

Staphylococcus aureus, causing soft tissue infection predominantly, was highly sensitive to recommended drugs for uncomplicated soft tissue infection such as co-trimoxazole (70%) and doxycycline (86%) and for complicated infection vancomycin (99%) and linezolid (97%). Global surveillance indicates > 90% susceptibility of

Staphylococcus aureus to co-trimoxazole, providing high confidence for empiric use in uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infection [

17]. In a previous study, doxycycline was reported to have 90% sensitivity against MRSA for uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infection [

18]. In this study, 54% of isolated

Staphylococcus aureus were methicillin resistant. These results is consistent with other studies [

15,

16]. Of the staphylococcal groups, MRSA is associated with a greater risk of mortality, longer duration of hospitalization and higher hospital costs compared with methicillin-susceptible

Staphylococcus aureus [

19,

20,

21]. Vancomycin is the drug of choice for MRSA and linezolid is the drug of choice for vancomycin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA). However, alarmingly 1% and 3% of isolates of

Staphylococcus aureus were found resistant to vancomycin and linezolid respectively. High resistance to meropenem was recorded in

Pseudomonas sp. isolates (26%) and

Acinetobacter sp. (64%). This observation is in agreement with the study reported by Ahmed et al[

16]. In south India, the resistance of

Acinetobacter sp. to meropenem increased from 16% in 2007 to 70% in 2008 [

3]. In this study, 1% vancomycin-resistant

Enterococcus (VRE) was observed. No isolates of VRE were reported in previous studies in Bangladesh [

16]. However, VRE is prevalent in many countries [

22,

23,

24]. More extensive research needs to be done in Bangladesh to obtain a definitive insight.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that E. coli, Klebsiella sp., S. aureus, Pseudomonas sp., coagulase negative Staphylococcus, S. Typhi and Enterococcus sp. were the most common isolates in clinical samples. The prevalence of antimicrobial resistance is very high. Moreover, third generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter sp., P. aeruginosa and E. coli, MRSA, VRSA, linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, VRE and ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella Typhi are public health alerts. Policy makers and national stakeholders should prioritize actions such as surveillance programs, audits, the creation of national antimicrobial guidelines, strong infection control procedures to control the threat of AMR. In addition, there is also a strong need for periodical training and education for healthcare professionals to abate the incidence of AMR in the country.

Author Contributions

MJS reports to lead the data collection, management, and analysis. MZA, FR, SF, SMSR, AR, ZHH, AS, HTB, SG, FM, and NP edited the primary draft. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The “Capturing Data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia (CAPTURA)” and SAG-WHONET project funded by the Department of Health and Social Care’s Fleming Fund using UK aid. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK Department of Health and Social Care or its Management Agent, Mott MacDonald.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The CAPTURA project was exempt from ethical review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the IVI because the project did not involve intervention or interaction with individuals and the information collected was not individually identifiable. This exemption is per the IVI IRB SOP D-RB-4-003. The CAPTURA project undertook the retrospective data collection and curation, and the authors used the digitized data to prepare this manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

The CAPTURA (Capturing data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia) consortium project received an official approval from the Communicable Disease Control, DGHS (Directorate General of Health Services), MoHFW (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) dated on May 17, 2020. The reference number is DGHS/DC/ARC/2020/1708. Prior to the data collection, a tri-party collaborative agreement was made among the DGHS, Bangladesh Specialized Hospital, and International Vaccine Institute- CAPTURA on 14 October 2020.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset will be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the microbiologist, data entry operators and laboratory technologists at the microbiology lab.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSH |

Bangladesh Specialized Hospital |

| CAPTURA |

Capturing Data on Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Trends in Use in Regions of Asia |

| IEDCR |

Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control & Research |

| CDC |

Communicable Disease Control |

| MoHFW |

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

| QAAPT |

Quick Analysis of Antimicrobial Patterns and Trends |

| CLSI |

Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute |

| VRSA |

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

|

| MRSA |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

References

- Rubin RP: A brief history of great discoveries in pharmacology: In celebration of the centennial anniversary of the founding of the American Society of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. Pharmacol Rev 2007, 59:289–359.

- Faryna A, Gilbert L, Wergowske, Kim G: Impact of therapeutic guidelines on antibiotic use by residents in primary care clinics. J Gen Intern Med 1987, 2:102–107.

- Subbalaxmi MV, Lakshmi V, Lavanya V. Antibiotic resistance--experience in a tertiary care hospital in south India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010 Dec;58 Suppl:18-22. PMID: 21568007.

- Ehijie FO Enato and Ifeanyi E Chima. Evaluation of drug utilization patterns and patient care practices. West African Journal of Pharmacy 2011; 22(1): 36–41.

- Puca V, Marulli RZ, Grande R, Vitale I, Niro A, Molinaro G, Prezioso S, Muraro R, Di Giovanni P. Microbial Species Isolated from Infected Wounds and Antimicrobial Resistance Analysis: Data Emerging from a Three-Years Retrospective Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021 Sep 24;10(10):1162. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lai PS, Bebell LM, Meney C, Valeri L, White MC. Epidemiology of antibiotic-resistant wound infections from six countries in Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2018 Mar 6;2(Suppl 4):e000475. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bassetti M, Di Biagio A, Rebesco B, Amalfitano ME, Topal J, Bassetti D. The effect of formulary restriction in the use of antibiotics in an Italian hospital. Eur J ClinPharmacol 2001; 57: 529-34.

- Alharbi AS. Bacteriological profile of wound swab and their antibiogram pattern in a tertiary care hospital, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2022 Dec;43(12):1373-1382. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas M, Roy DN, Tajmim A, Rajib SS, Hossain M, Farzana F, Yasmen N. Prescription antibiotics for outpatients in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional health survey conducted in three cities. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014 Apr 22;13:15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pearson M, Chandler C. Knowing antmicrobial resistance in practice: a multi-country qualitative study with human and animal healthcare professionals. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1599560. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Remesh A, Samna Salim AM, Gayathri UN, Retnavally KG: Antibiotics prescribing pattern in the in-patient departments of a tertiary care hospital. Pharma Pract 2013, 4:71–76.

- Minyahil A, Woldu, Sultan Suleman, Netsanet Workneh and Hafty barhane. Retrospective study of the pattern of Antibiotic Use in hawassa University Referral Hospital Pediartric ward, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2013; 3(02): 93-98.

- Shadia, K., Borhan, S. B., Hasin, H., Rahman, S., Sultana, S., Barai, L., Jilani, M. A., & Haq, J. A. (2012). Trends Of Antibiotic Susceptibility Of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhi And Paratyphi In An Urban Hospital Of Dhaka City Over 6 Years Period. Ibrahim Medical College Journal, 5(2), 42–45. [CrossRef]

- Kot B. Antibiotic Resistance Among Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Pol J Microbiol. 2019 Dec;68(4):403-415. Epub 2019 Dec 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mulu W, Abera B, Yimer M, Hailu T, Ayele H, Abate D. Bacterial agents and antibiotic resistance profiles of infections from different sites that occurred among patients at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Jul 6;10(1):254. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmed I, Rabbi MB, Sultana S. Antibiotic resistance in Bangladesh: A systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2019 Mar;80:54-61. Epub 2019 Jan 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekema D.J., Pfaller M.A., Shortridge D., Zervos M., Jones R.N. Twenty-Year Trends in Antimicrobial Susceptibilities Among Staphylococcus aureus from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019;6:S47–S53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Linz MS, Mattappallil A, Finkel D, Parker D. Clinical Impact of Staphylococcus aureus Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Mar 11;12(3):557. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cosgrove SE, Qi Y, Kaye KS, Harbarth S, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. The impact of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia on patient outcomes: mortality, length of stay, and hospital charges. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005;26(2):166–74.

- Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillinsusceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(1):53–9.

- Engemann JJ, Carmeli Y, Cosgrove SE, Fowler VG, Bronstein MZ, Trivette SL, et al. Adverse clinical and economic outcomes attributable to methicillin resistance among patients with Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(5):592–8.

- Cetinkaya Y, Falk P, Mayhall CG. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;13(4):686–707.

- Orsi GB, Ciorba V. Vancomycin resistant enterococci healthcare associated infections. Annali di igiene: medicina preventiva e di comunita 2013;25 (6):485–92.

- Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39 (3):309–17.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).