1. Introduction

Multidrug resistance bacteria is one of the major public health problems in the 21

st century. The most comprehensive and newest published data regarding wold-wide resistances and outcomes showed that more than 5 million people died in 2019 related to antimicrobial resistance and more than 1.25 million people had a death directly due to the multidrug resistant bacteria [

1]. Many other studies proved that multidrug resistant bacteria increase mortality and morbidity [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Lungs and thorax, followed by blood stream and abdominal ones, represent the most common site of infection that generates the highest mortality [

1]. Urinary tract infections represent the fourth cause of mortality regarding the antimicrobial resistance [

1]. Escherichia coli was the leading pathogen accounting for more than 0.25 million deaths in 2019 [

1].

Bacterial resistance present high variability regarding the geographic area. For instance, third generation cephalosporin resistant Escherichia coli incidence varies from less than 5% in Mongolia to more than 80% in Afghanistan [

1]. In Est-European countries, this resistance varies from 20-60% with an estimation of 20-30% for Romania [

1].

Real data regarding Romania on the resistances of positive urine culture are scarce and most of the studies included only female patients [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. All of these studies reported that Escherichia coli is the leading bacteria to generate a urinary tract infection followed by Klebsiella and Proteus. On the other hand, only one study evaluated urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes mellitus from the Western part of Romania [

13].

To fill this gap, we performed a cross-sectional analysis in the largest hospital from the Western part of Romania of the positive urine cultures identified during the year 2021 in mixed adult population.

2. Results

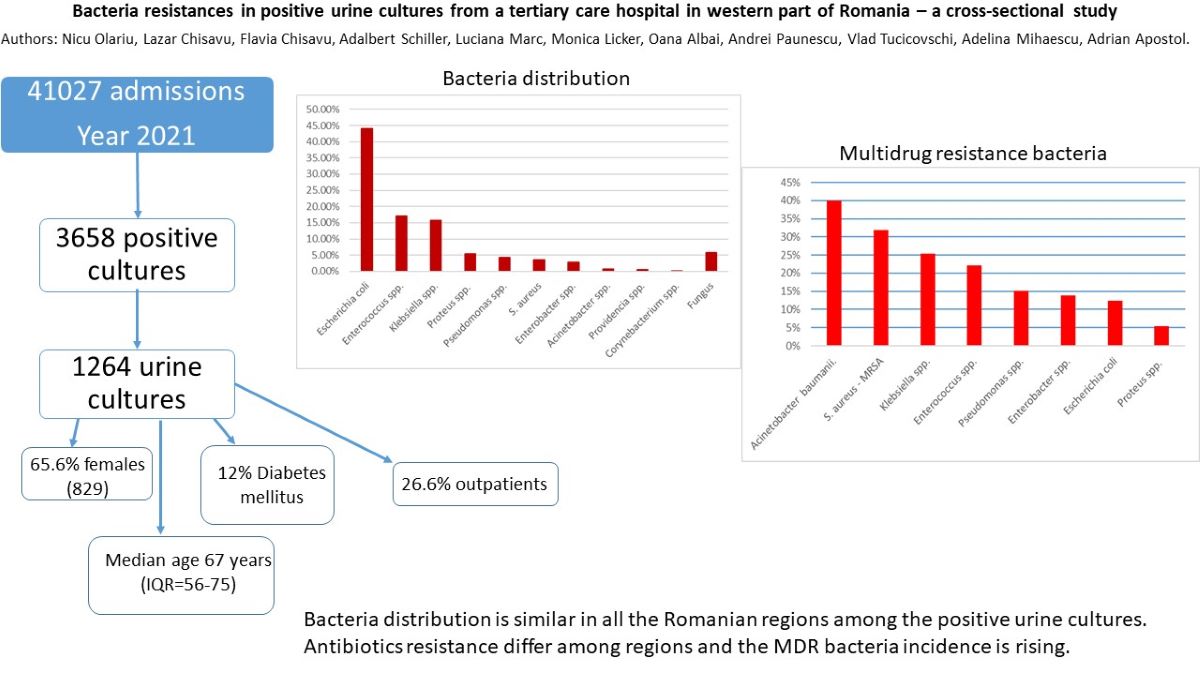

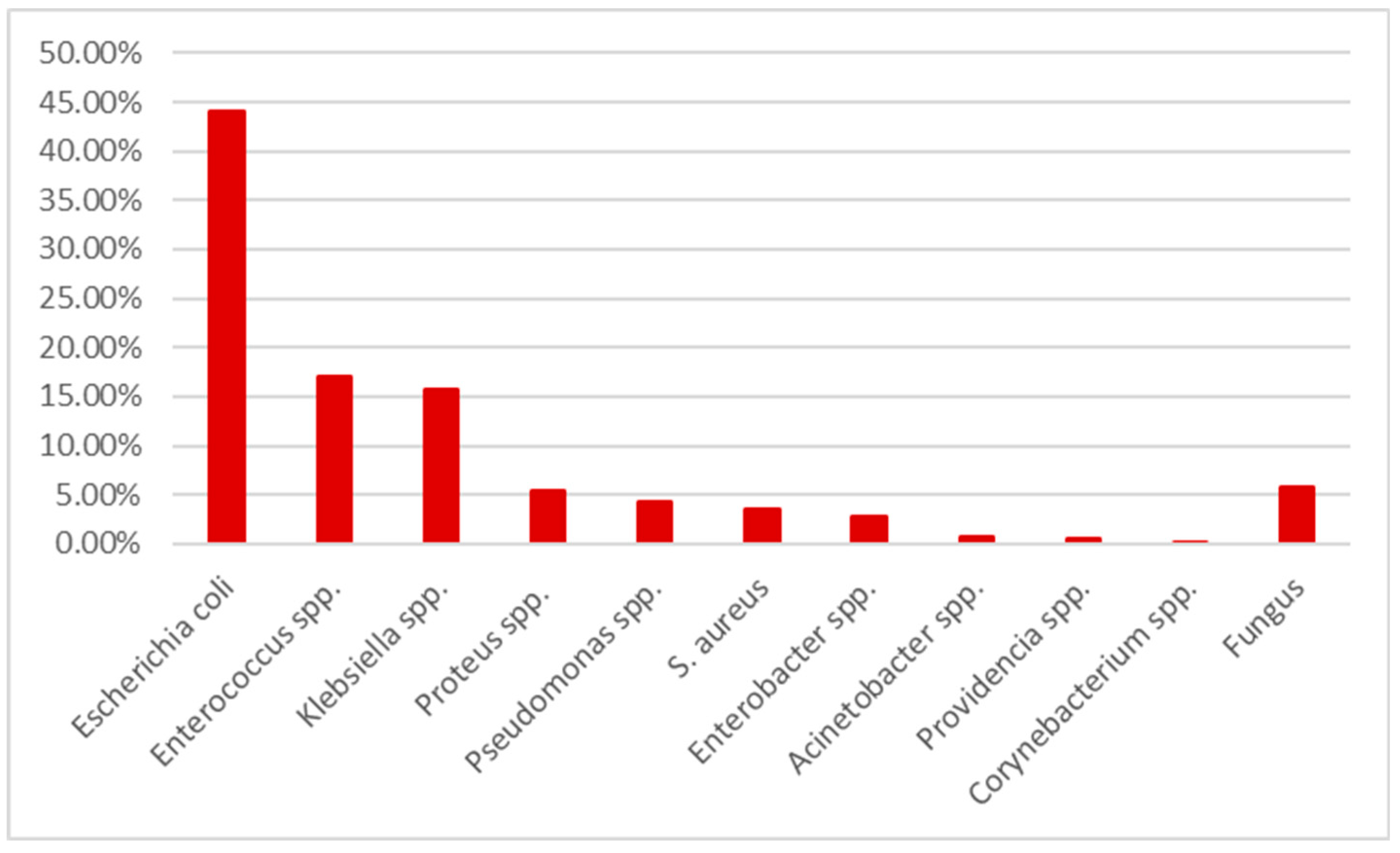

During the year 2021, in “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency County Hospital from Timisoara there were 41027 admissions with 3658 positive cultures. 1343 represented positive urine cultures. After excluding pediatric patients, the remaining cohort consisted in 1264 positive cultures. The germs distribution is presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1.

Escherichia coli was the most common one, followed by

Enterococcus spp, Klebsiella spp and

Proteus spp.

The median age was 67 years (IQR=56-75), with 829 (65.6%) females.

E. coli presented a higher incidence among females (78.2%) and

Acinetobacter baumanii and

Providencia spp. among males (90% and 100%). There were no statistical differences regarding the median age stratified by sex (67 years for both groups, p=0.084) or bacteria (p=0.651). We present in Supplemental

Table S1 the distribution regarding the department of the positive urine cultures. We note that most of the patients were outpatients (26.6%) followed by urology department with 18.8% and neurology – 13.1%. 12% (151) of the patients presented diabetes mellitus.

In order to evaluate the sensibilities of bacteria regarding the tested antibiotics, we performed a stratified analysis by germ. In the analysis we included only the strains tested for a specific antibiotic to have non-biased results. The presented percentages will represent the sensibility; the difference to 100 will be the resistant rate. Next, we will present the results stratified by bacteria. All the data are present in Supplemental

Table S2.

Escherichia coli presented the highest resistances to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid – 50% followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole – 27.5%, quinolones (22.4% to ciprofloxacin and 20.7% to levofloxacin) and cephalosporin (15.6% to cefuroxime, 11.7% to ceftriaxone and 11.6% to cefepime). On the other hand, the resistance rate to aminoglycosides was low (6.8% to gentamycin and 1.5% to amikacin).

Enterococcus spp. presented extremely high resistances to quinolones (81.3% to ciprofloxacin and 59.1% to levofloxacin), 32% to gentamycin and only 10% to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

On the other hand, Klebsiella spp. presented 40% resistance rate to penicillin, more than 30% to cephalosporins, almost 30% to quinolones and between 7 and 9% to penems (9.3% to meropenem and 7% to imipenem).

Proteus spp. presented the highest resistant rates to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (33%), 2nd and 3rd generation cephalosporins (17.4% to cefuroxime and 16.7% to ceftazidime), 25% to quinolones and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and 23.4% to gentamycin. One should mention that none of the strains presented resistance to penems and only 2.7% to 4th generation cephalosporins.

Pseudomonas spp. presented high resistance rates to quinolones (30% to ciprofloxacin and 33.3% to levofloxacin), cephalosporins (18.9% to 3rd generation and 17.9% to 4th generation), 23.4% to gentamycin and almost 20% to penems (16.7% to meropenem and 18.5% to imipenem).

S. aureus presented high resistance rates to quinolones (25% to ciprofloxacin and 33.3% to levofloxacin), 13.9% to gentamycin.

Enterobacter spp. presented high resistance rates to cephalosporins – around 25%, quinolones (32% to levofloxacin and 28.6% to ciprofloxacin) and 26.1% to piperacillin-tazobactam. Aminoglycosides resistance was 19.4% to gentamycin and 9.9% to amikacin.

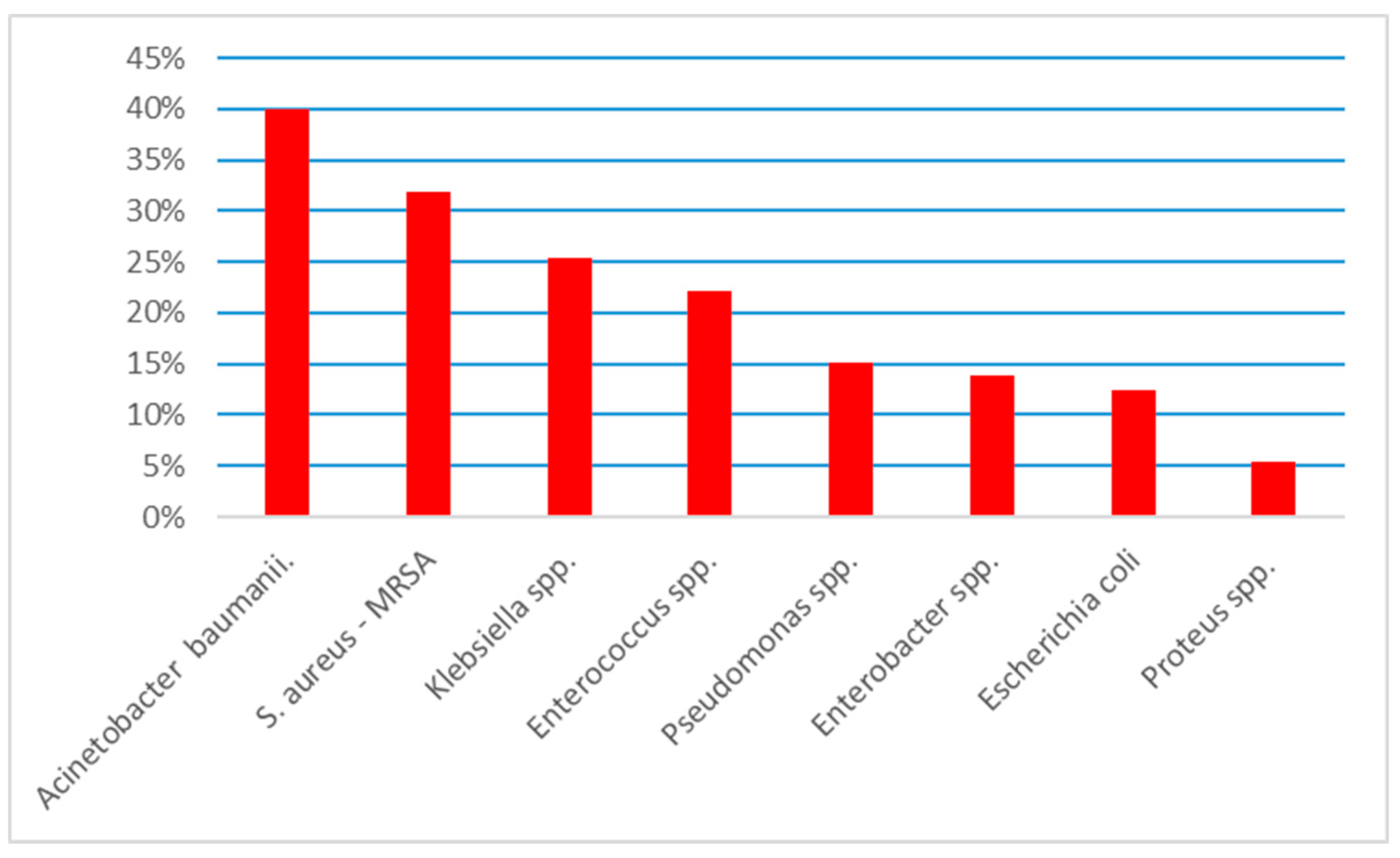

The next step was to identify the multidrug resistant rate (MDR). We used the international accepted multidrug resistance definition established back in 2011 [

15]. The data are presented in

Figure 2.

Overall, 198 (16.6%) strains presented MDR. Acinetobacter baumanii presented the highest MDR rate – 40% (N=4), followed by MRSA – 31.8% (N=14), Klebsiella spp. – 25.3% (N=50) and Enterococcus spp. – 22.2% (N=48). Pseudomonas spp. with 15.1% (N=8), E. coli with 12.5% (N=70) and Proteus spp. with 5.4% (N=4) presented lower incidences of MDR.

3. Discussions

Our study is the first study that evaluates bacteria and the antibiotics resistance rate identified in a mixed adult population from the Western part of Romania. The most common identified bacteria is E. coli followed by Enterococcus spp., Klebsiella spp. and Proteus spp. E. coli presented the highest resistance rate to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (50%), Enterococcus spp. to ciprofloxacin (71.3%), Klebsiella spp. to piperacillin-tazobactam (43.3%) and Proteus spp. to trimetroprime-sulfometoxazole (33%). The highest incidence of MDR bacteria was among Acinetobacter baumanii (40%), followed by MRSA (31.8%) and Klebsiella spp. (25.3%).

There is a known fact that female gender present a higher risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) especially before the age of 50 years old [

16]. In elderly, it seems that this gap is reduced, and both females and males present the same risk of UTI, especially due to the urological pathology in males [

17]. In our cohort with a relatively advance age (67), there is a slight predominance in females (65.6%), but with no difference regarding the age between sex. Previous published data from Romania that included both males and females, showed an increased prevalence of UTIs among elders [

11,

12,

13,

18]. Regarding the bacteria distribution, the results from our study are similar with previous published data, with

E. coli being the leading pathogen, followed by

Enterococcus spp. and

Klebsiella spp [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

18].

There are several mechanisms involved in bacterial resistance development [

19]. Besides the increased use of antibiotics in both people and animals, there is a link between the resistance rates to different antibiotics regarding the most common prescribed antibacterial agents within different regions [

19]. As we identified in our study, there are differences regarding the resistance rates identified by us when compared to other regions of Romania or other East-European countries [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

18,

20].

Previously published data from Romania presents different sensibilities in both males and females. For

E. coli, Petca reported the highest resistance rate to ciprofloxacin (30%) and only 14% to amoxillin-clavulanic acid in females [

8] and Chibelean up to 72% to quinolones and 66% to penicillines-amines in males [

10]. In an analysis of six East-European countries,

E. coli presented the highest resistant rate to ampicillin (39.6%) and trimethoprim (23.8%), and around 15% to ciprofloxacin [

20]. We report a higher resistance rate to levofloxacin and similar to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for

Enterococcus spp. compared with current Romanian data - 32% resistance to levofloxacin and 10% to amikacin in females [

8] and 25% to levofloxacin and 15% to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in males [

10]. Petca report a resistance rate of 28% to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and 15% to levofloxacin for

Klebsiella spp. in females [

8], while Chibelean 59% to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, 44% to levofloxacin and 38% to ceftazidime in males [

10], results different from ours. On the other hand, all of the aforementioned studies reported low resistances to penems, similar to our results [

8,

10]. Regarding

Proteus spp. and

S. aureus, current literature report results similar to ours[

8,

10].

Pseudomonas spp. is reported to have different resistances to levofloxacin (31-44%), amikacin (14-32%), ceftazidime (24-26%) in the reported studies from Romania [

8,

10]. One should mention that both our study and previous data report an increasing incidence of penems resistance between 15 and 20% [

8,

10].

The mixed adult population explains the differences from our study with different uropathogens. On the other hand, one should keep in mind the associated comorbidities.

The antibiotics resistance represents a major world health problem. The reported mortality associated to MDR bacteria is rising with an estimated mortality of 5 million people in 2019 and presumed to double by 2030 [

1,

2,

6]. On the other hand, the estimated costs in treating MDR bacteria represent 12.61 billion dollars in 2024, with an increase of 6.5% per year, up to 16.22 billion dollars in 2028 [

21]. The published data regarding MDR bacteria and even the resistance to several antibiotics are not uniform, with most of the studies performed in the developed countries [

1]. Nevertheless, due to the regional pattern of antibiotics resistances, one could not properly estimate a bacteria resistance to a specific antibiotic not even in the same country. The aim of our study is to present the real-life data regarding the bacterial distribution and the antibiotic resistance in the most common encountered germs for positive urine cultures.

As we previously mentioned, there is a similar pattern regarding the bacteria distribution among patients with UTI. On the other hand, one should notice the increasing incidence of hospital acquired infections (HAI), with UTI representing almost 13% of them [

22]. This pattern is partially proved in our analysis, due to the increasing incidence of “hospital bacteria” like

Klebsiella, Proteus,

Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter and MRSA.

E. coli was the leading pathogen regarding the absolute number of MDR strains identified in our study (N=70), but only 12.5% of

E.coli were MDR. The leading MDR pathogen reported by us is

Acinetobacter baumanii – 40%, followed by MRSA – 31.8% and

Klebsiella spp. – 25.3%. A recent analysis of Petca regarding the MDR uropathogens in Romania, showed an incidence of 4.5% of MDR bacteria, mush lower compared to ours (16.6%) [

9]. Nevertheless, in both Petca’s study and ours,

E. coli and

Klebsiella spp. represented the most common MDR germs. On the other hand, the overall MDR incidence can be even higher in our study, due to the fact that the bacteria testing was not uniform and we did not included all the possible antibiotics to whom a germ might be sensible.

Overall, our study was performed in a mixed adult population. Most of the evaluated positive cultures were from admitted patients, some of which presented urine catheters and many of them presented comorbidities. For instance, we reported a 12% incidence of diabetes mellitus. A previously study from the same hospital showed a 12% incidence of UTI in diabetic patients [

13]. On the other hand, some of the patients presented multiple UTI, multiple hospital admissions, surgical interventions, while others had some invasive interventions on the urinary tract. In addition, the immunosuppressed status is more common among older patients. All of these factors increases prone to multiple infections, increased number of antibiotics doses and in the end, a higher risk of a MDR bacteria development.

With this study, we aimed to bring more light regarding the antibiotic resistances in positive urine cultures from the west part of Romania. As expected, our study present some limitations. The cross-sectional type, without data regarding hospital stay, mortality and other comorbidities could limit the impact of our results. On the other hand, a relatively high number of evaluated positive urine cultured doubled by the evaluation of the MDR incidence represent the strong points.

4. Material and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional retrospective analysis of all the positive urine cultures from the Emergency County Hospital “Pius Brinzeu” from Timisoara, Romania identified in the year 2021. The “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency County Hospital from Timisoara Ethics Committee approved the study (466/17.05.2024) and it was performed in accordance with the Ethics Code of the World Medical Association. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki recommendations. The patients signed an informed consent at the admission to the hospital. We used the electronic data system in order to extract all the positive urine cultures. We recorded the gender, age, the culture type and the identified bacteria. In addition, we extracted the sensibilities and resistances to several antibiotics. Out of 41027 admissions during the year 2021, 1268 were urine cultures out of 3658 positive cultures.

Sample Collection

The samples were collected over a 1-year period, comprising all of the positive urine cultures from the admitted patients used to confirm the clinical suspicion of infection.

Bacterial Identification and Antibiotic Testing

Cultures were performed according to the working protocol of the Microbiology Laboratory of Emergency County Hospital “Pius Brinzeu” from Timisoara. All isolates were first identified using the VITEK® 2 GN and VITEK® 2 GP ID cards (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Antimicrobial susceptibility tests (AST) were performed using the VITEK 2 GN AST-N222 and VITEK 2 AST GP 67 cards (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) by the determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method [

14,

15]. Classification into resistance phenotypes was performed according to the Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria [

14]. We used the following reference strains:

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922,

Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC1705,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923. For the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method, antibiotics from Thermo Fischer Scientific were used. The concentrations of the antibiotic disks were chosen according to the CLSI 2021 standard [

15]

Identified Bacteria

The germs that we identified and evaluated are: Escherichia Coli, Klebsiella spp, Proteus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Enteroccocus spp., Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter baumanii, Providencia spp., Corynebacterium spp..

The outcomes of our study are the bacteria distribution and the incidence of certain antibiotics resistance and sensibilities. In addition, we evaluated the multidrug resistance of the most common identified bacteria.

The antibiotics we recorded are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Recorded antibiotics.

Table 1.

Recorded antibiotics.

| Antibiotic class |

Antibiotic |

| Aminoglycozides |

Gentamycin |

| Amikacin |

| Carbapenems |

Meropenem |

| Imipenem |

| Fluoroqinolones |

Ciprofloxacin |

| Levofloxacin |

| Cephalosporins |

Cefepim |

| Ceftriaxone |

| Ceftazidime |

| Cefuroxime |

| Penicilines |

Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid |

| Ampicillin |

| Oxacillin |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam |

| Polimixines |

Colistin |

| Sulfonamides |

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Glycopeptides |

Vancomycin |

| Oxazolidinone |

Linezolid |

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. The age distribution was non-Gaussian (evaluation performed using the Shapiro-Wilk test) and is presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistical significant. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test to evaluate the differences between the ages stratified by bacteria type and Mann-Whitney test to evaluate the age stratified by sex. The analysis was performed using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 22.021 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium;

https://www.medcalc.org; 2024).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, bacteria distribution in positive urine cultures seems to follow a similar pattern, regarding the region of recorded data. The antibiotic resistances are different between countries and even in the same country. Our study could be a foundation for a possible future protocol used in our hospital in order to initiate an appropriate empiric treatment in patients with UTIs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.O., L.C., F.C. and A.M.; Methodology, A.S, L.M., M.L. and A.M.; Software, L.C., A.P. and V.T.; Validation, A.M, A.A. and A.S.; Formal Analysis, L.C., A.P. and V.T.; Investigation, L.C. and F.C.; Resources, L.M., O.A., A.P. and A.M.; Data Curation, L.C., F.C., A.P. and V.T; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, N.O., L.C. and F.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, all authors; Visualization, L.M. and A.M.; Supervision, M.L., A.S. and A.A.; Project Administration, M.L. and A.M.; Funding Acquisition, L.M., A.P. and O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency County Hospital from Timisoara Ethics Committee approved the study (466/17.05.2024) and it was performed in accordance with the Ethics Code of the World Medical Association. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki recommendations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author at the e-mail address chisavu.lazar@umft.ro. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request. All of the data are presented in the current form of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Victor Babes” in Timisoara for providing support for the article processing charges.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022 Feb 12;399(10325):629-655. [CrossRef]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Takahashi, E.; Hongsuwan, M.; Wuthiekanun, V.; Thamlikitkul, V.; Hinjoy, S.; Day, N.P.; Peacock, S.J.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Hospital, A.; et al. Epidemiology and burden of multidrug-resistant bacterial infection in a developing country. eLife 2016, 5, e18082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalimet, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, S.I.; Rao, P.C.; Dolecek, C.; Day, N.P.J.; Stergachis, A.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.L. Measuring and mapping the global burden of antimicrobial resistance. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, J. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; London: 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- de Kraker, M.E.A.; Stewardson, A.J.; Harbarth, S. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016;13. [CrossRef]

- Petca, R.-C.; Mareș, C.; Petca, A.; Negoiță, S.; Popescu, R.-I.; Boț, M.; Barabás, E.; Chibelean, C.B. Spectrum and Antibiotic Resistance of Uropathogens in Romanian Females. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petca, R.-C.; Negoiță, S.; Mareș, C.; Petca, A.; Popescu, R.-I.; Chibelean, C.B. Heterogeneity of Antibiotics Multidrug-Resistance Profile of Uropathogens in Romanian Population. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(5):523. [CrossRef]

- Chibelean, C.B.; Petca, R.-C.; Mareș, C.; Popescu, R.-I.; Enikő, B.; Mehedințu, C.; Petca, A. A Clinical Perspective on the Antimicrobial Resistance Spectrum of Uropathogens in a Romanian Male Population. Microorganisms. 2020; 8(6):848. [CrossRef]

- Arbune, M. , Gurau, G., Niculet, E., Iancu, A. V., Lupasteanu, G., Fotea, S., Vasile, M.C.; Tatu, A.L. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance of ESKAPE pathogens over five years in an infectious diseases hospital from South-East of Romania. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 2369–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, A.; Tarco, E.; Butiuc-Keul, A. Antibiotic resistance profiling of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae from Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Germs 2019, 9, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiţă, T.; Timar, B.; Muntean, D.; Bădiţoiu, L.; Horhat, F.; Hogea, E.; Moldovan, R.; Timar, R.; Licker, M. Urinary tract infections in Romanian patients with diabetes: prevalence, etiology, and risk factors. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 1: 16;13. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; Paterson, D.L.; Rice, L.B.; Stelling, J.; Struelens, M.J.; Vatopoulos, A.; Weber, J.T.; Monnet, D.L. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwin, M.S.; Saigal, C.S.; Yano, E.M.; Avila, C.; Geschwind, S.A.; Hanleym, J.M.; Joycem, G.F.; Madison, R.; Pace, J.; Polich, S.M.; Wang, M. Urologic diseases in America project: analytical methods and principal findings. Journal of Urology 2005, 3, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of General Practitioners, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, Department of Health, Morbidity Statistics from General Practice: Fourth National Study 1991-1992, 1995, HMSO, London, UK, Series MB5, no. 3.

- Cuiban, E.; Radulescu, D.; David, C.; Turcu, F.L.; Bogeanu, C.; Feier, L.F.; Onofrei, S.D.; Vacaroiu, I.A. Wcn23-0468 urinary tract infections in chronic kidney disease patients - a Romanian centre experience. Kidney International Reports, Volume 8, Issue 3, S272. [CrossRef]

- Khameneh, B.; Diab, R.; Ghazvini, K.; Bazzaz, B.S.F. Breakthroughs in bacterial resistance mechanisms and the potential ways to combat them. Microbial pathogenesis, 2016, 95, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ny, S.; Edquist, P.; Dumpis, U.; Gröndahl-Yli-Hannuksela, K.; Hermes, J.; Kling, A.M.; Klingeberg, A.; Kozlov, R.; Källman, O.; Lis, D.O.; Pomorska-Wesołowska, M.; Saule, M.; Wisell, K.T.; Vuopio, J.; Palagin, I. NoDARS UTIStudy Group. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli isolates from outpatient urinary tract infections in women in six European countries including Russia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2019, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/multidrug-resistant-bacteria-global-market-report (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Magill, S.S.; Edwards, J.R.; Bamberg, W.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Dumyati, G.; Kainer, M.A.; Lynfield, R.; Maloney, M.; McAllister-Hollod, L.; Nadle, J.; Ray, S.M.; Thompson, D.L.; Wilson, L.E.; Fridkin, S.K. Emerging Infections Program Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Survey Team. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 1198–1208, Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun 16;386(24):2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).