1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among the top 10 priorities for global public health. This phenomenon has developed and spread due to the selection pressure resulting from the excessive or incorrect use of antibiotics [

1].

The number of deaths caused by antimicrobial resistance (AMR) could exceed 10 million annually by the year 2050 without active measures promoting the prudent use of antibiotics, improving hand hygiene in hospitals and environmental healthcare hygiene, as well as enhancing food biosecurity [

2].

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria poses as a concerning issue for public health due to the increased risk of healthcare-associated infections and limited treatment options. "ESKAPE" is an acronym for six bacteria of major interest in AMR surveillance systems, namely: (E) Enterococcus faecium, (S) Staphylococcus aureus, (K) Klebsiella pneumoniae, (A) Acinetobacter baumannii, (P) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and (E) Enterobacter species [3, 4].

The "ESKAPE" pathogens are frequently implicated in severe infections, ranking high among the causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a list of priorities within this group. Gram-negative bacilli are considered "critical": carbapenem-resistant CBR Acinetobacter baumannii, CBR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (C3R) Klebsiella pneumoniae, and C3R Enterobacter spp. In the second line of priority are Gram-positive cocci, namely vancomycin-resistant (VAN-R) Enterococcus faecium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [

5,

6].

Antibiotics are frequently used to treat COVID-19-related bacterial infections. The excessive use of antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic can accelerate the emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [

7].

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, although many E.U. countries experienced a general decrease in antibiotic consumption both in the community and in healthcare facilities, certain antibiotics, such as azithromycin and ceftriaxone, saw an increase in usage. The reduction in prescriptions was induced by isolation, decreased mobility, and a decline in elective surgical interventions, but the impact of reduced antibiotic use on AMR, especially concerning the ESKAPE group, is insufficiently understood. In a survey conducted in 26 E.U. countries, monitoring antibiotic prescribing behaviors in healthcare facilities was halted in 9 countries, and antibiotic prescriber education programs were interrupted in 11 countries [

8,

9].

Understanding the link between COVID-19 and antibiotic use can contribute to the development of strategies to limit the impact of infections on vulnerable populations, thereby aiding the global effort to combat infectious diseases.

The study aims to assess the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of ESKAPE microorganisms during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2022) in a multidisciplinary emergency hospital.

2. Results

2.1. Microbial Profile of the Isolates from Hospital

During the pandemic 2020-2022, the microbiology laboratory obtained 1117 bacterial isolates, with the lowest annual frequency of positive cultures recorded in 2020 (266 strains), when the specific activity of the hospital's departments was most restricted. The average length of hospitalization per year varied over the three years, ranging between 4.32 and 4.96 days.

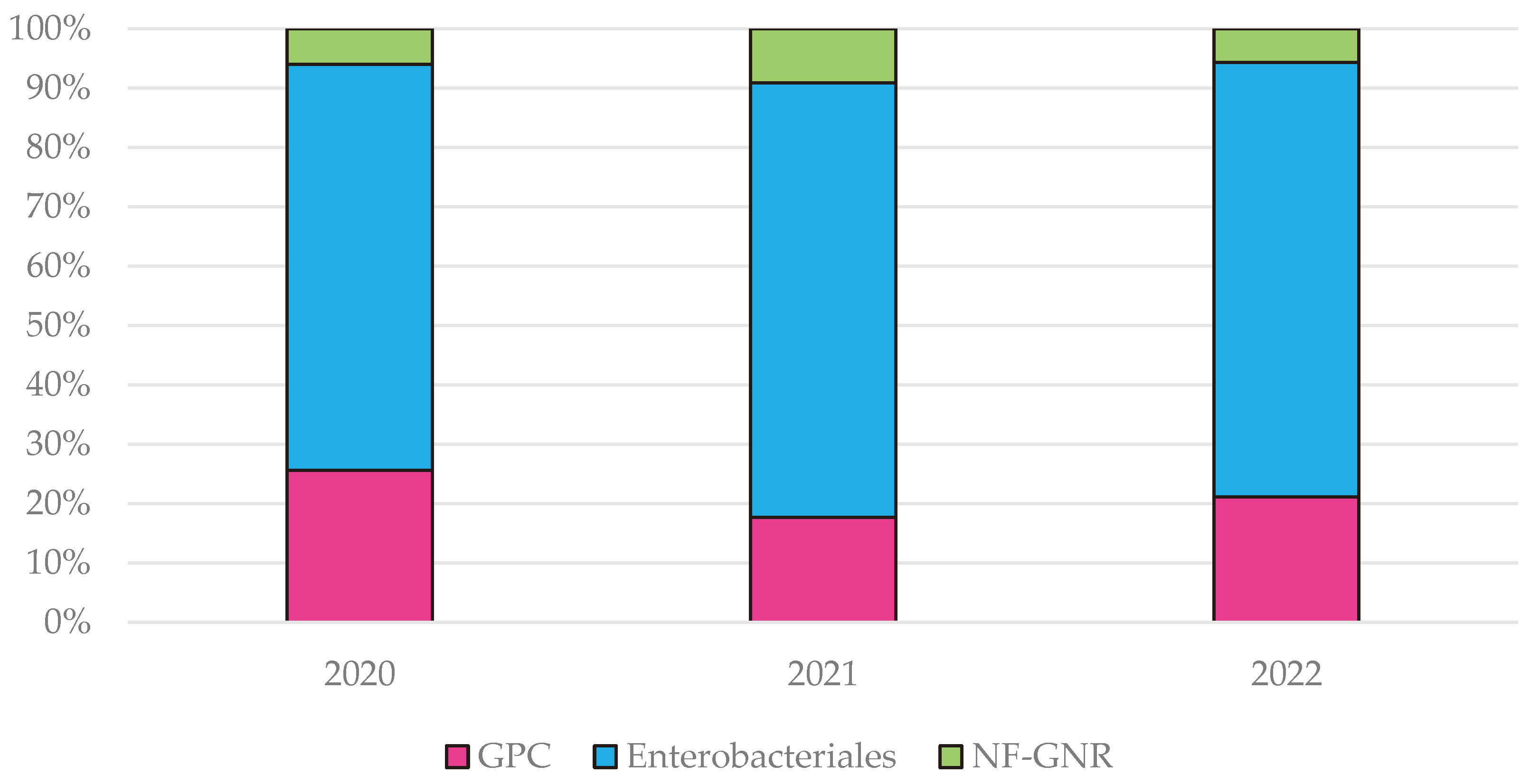

The isolated bacteria were grouped into Gram-positive cocci (GPC), Gram-negative bacilli from the

Enterobacterales order, and Gram-negative non-fermentative roads (NF-GNR). The highest frequency of GPC was recorded during the first pandemic year, 25.5% compared to 17% in 2021 and 21.1% in 2022, while NF-GNR were identified more frequently in the second pandemic year, representing 9.1% compared to 6% in 2020 and 5.6% in 2022 (

Figure A1).

The distribution according to the antibiotic susceptibility testing method highlights 50,22% disk diffusion tests and 47% tests using the MIC method. Both methods were applied to 2.77% of the isolated strains.

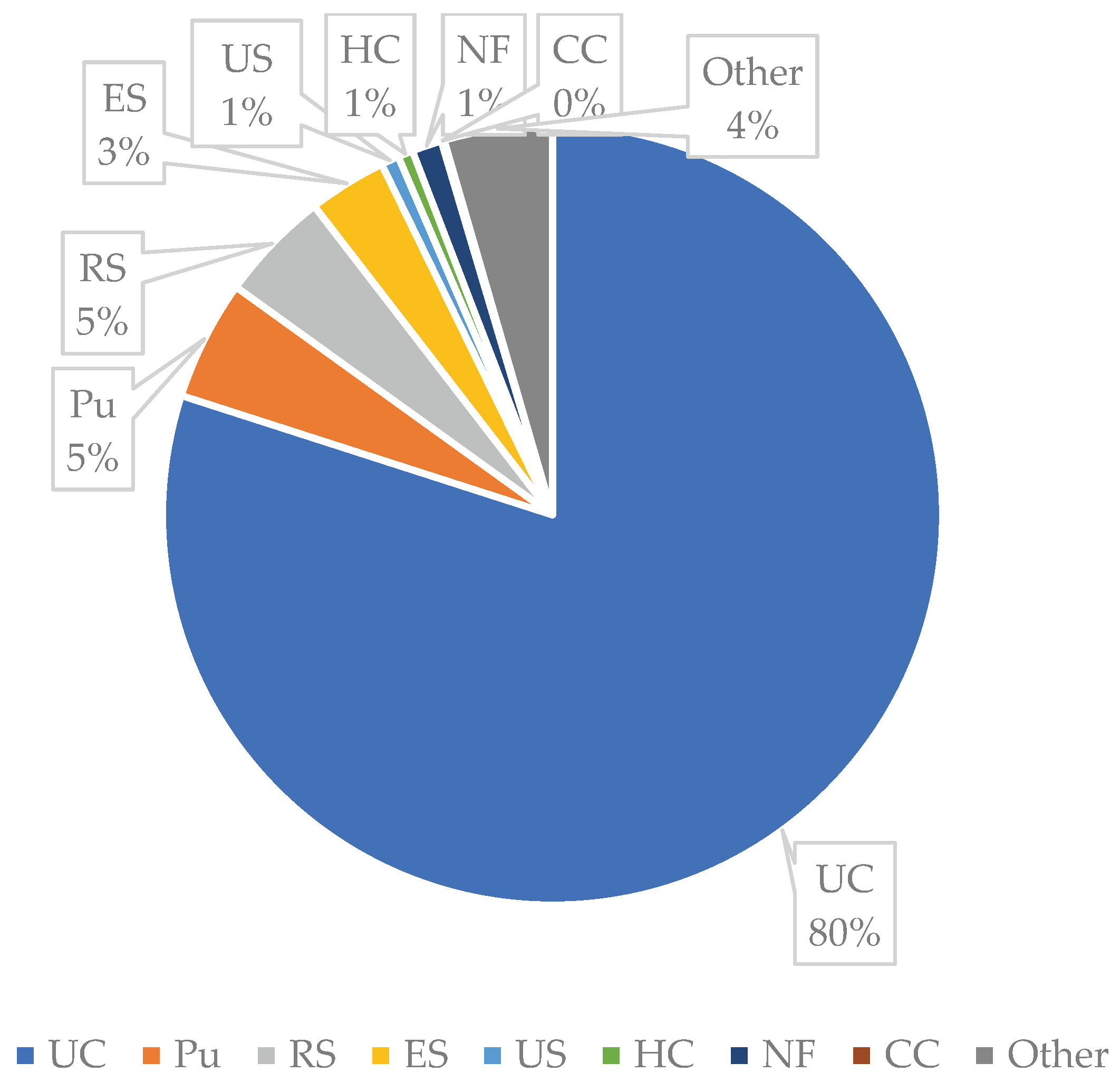

Urine cultures were the most requested microbiological investigations, constituting 80% of bacterial cultures. Much fewer analyses were performed on other biological samples such as: 5% purulent secretions, 5% respiratory secretions, 3% ear secretions, and 1% nasal and pharyngeal exudates. Blood cultures represented only 0.45% of the tested biological samples (

Figure A2).

The highest microbial load is found in the urology department, representing 38.76% of bacterial isolates. The Internal Medicine department accounts for -12.71%, the Intensive Care Unit for 12.17%, and Neurology for 10.29%. Bacterial strains were obtained from between 4.9% and 2.68% of the identified isolates from the ENT, Pulmonology, Rheumatology, Surgery, and Cardiology departments. Each other hospitals departments were associated with <1% of bacterial isolates (

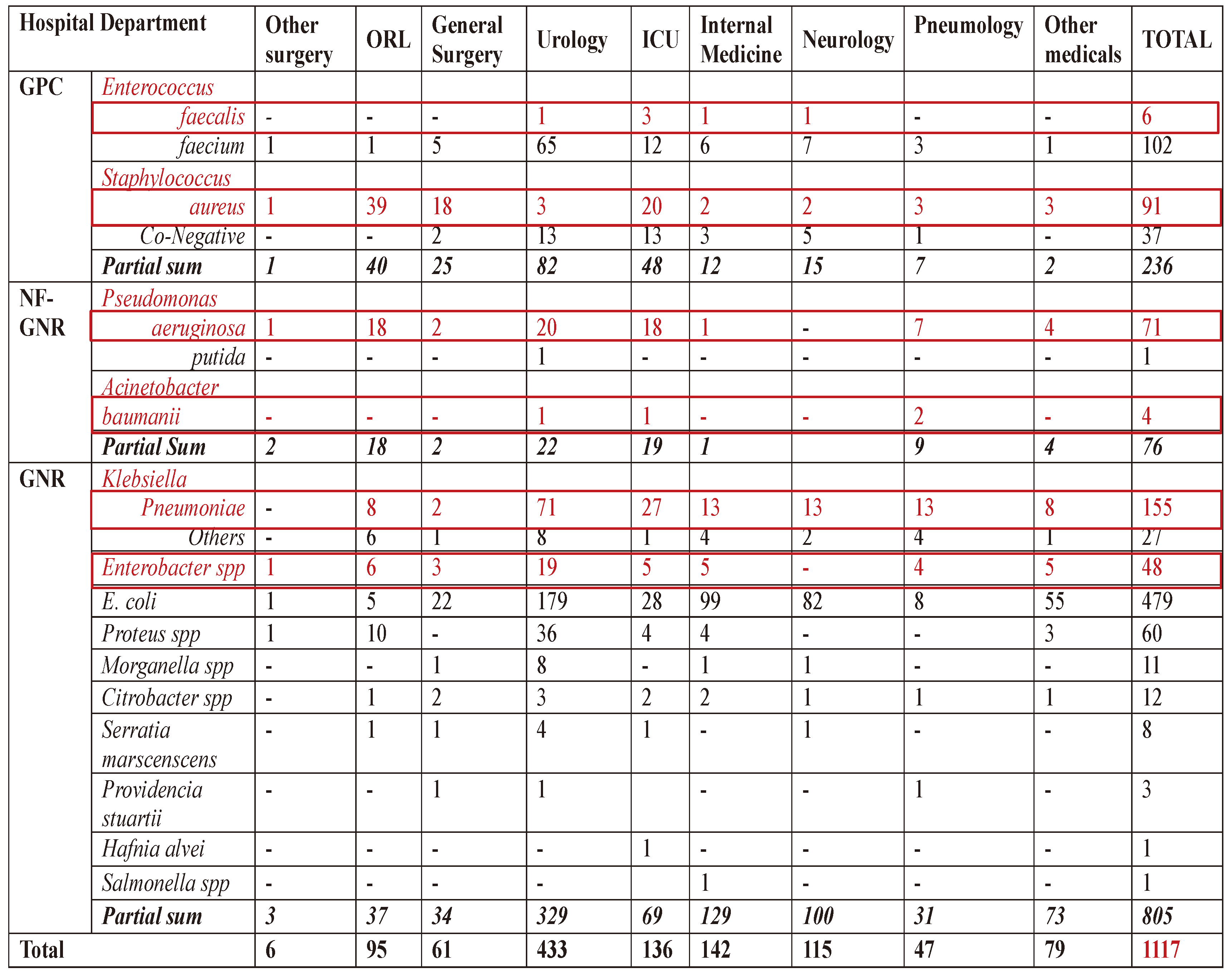

Table 1).

E. coli was isolated with the highest frequency, of 42.8% of species, potentially influencing antibiotic resistance in other Enterobacteriaceae. At the same time, ESKAPE group account 33.5% of the bacterial strains.

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of the ESKAPE Bacterial Group

2.2.1. Enterococcus spp

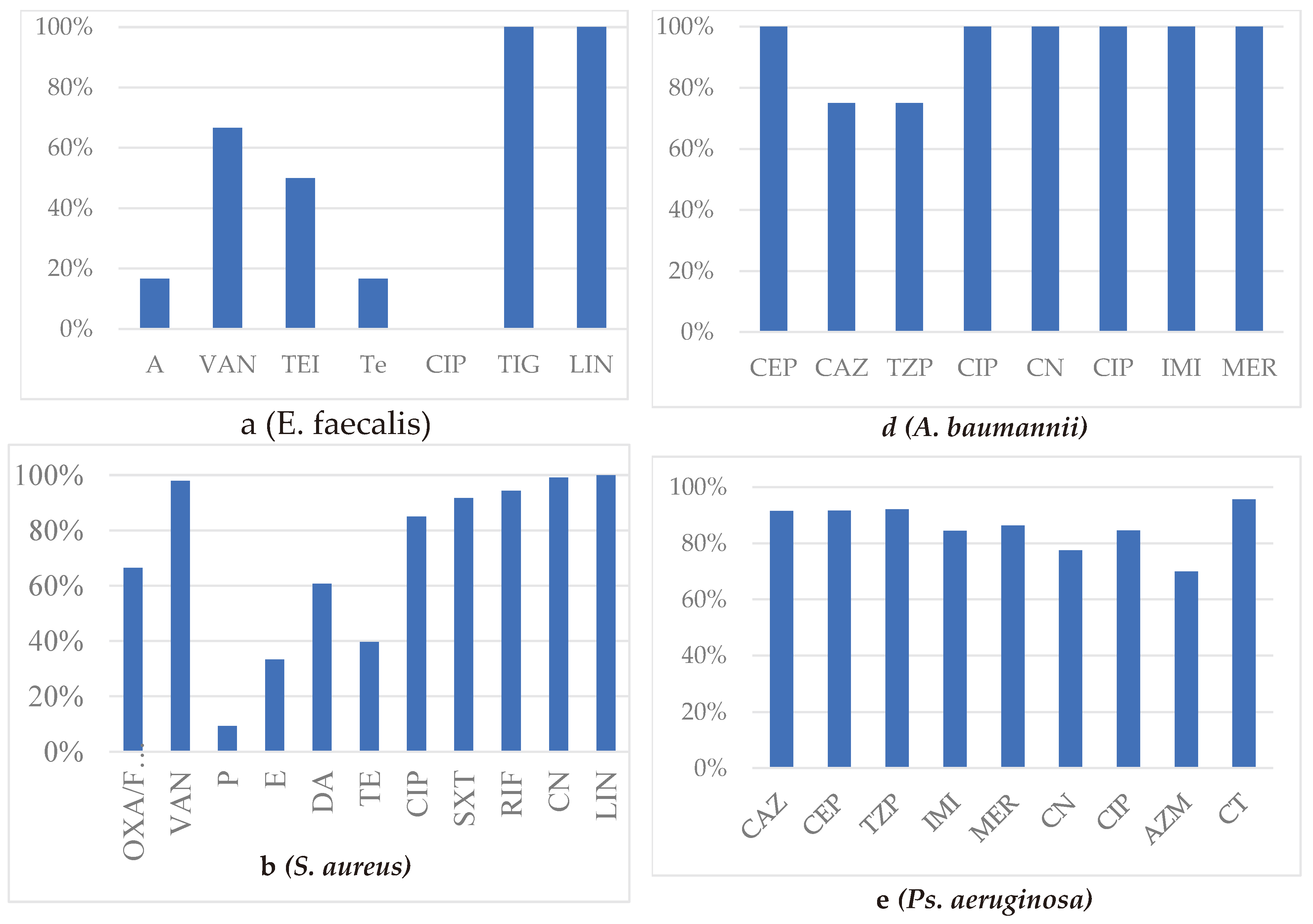

Enterococci were identified in 108 isolates with the following distribution: 50.9% E. faecalis, 6% E. faecium, and 43% unspecified Enterococcus spp. Overall, antibiotic susceptibility rates for enterococci strains were 21% for Tetracycline, 74.1% for Penicillin, 45.7% for Ciprofloxacin, 91.5% for Ampicillin, 100% for Linezolid, and 100% for Tigecycline.

E. faecium strains were found in urine cultures (3/6), blood cultures (2/6), and sputum (1/6), mostly from men (4/6), admitted to the ICU (3/6), pulmonology department (1/6), internal medicine (1/6), and urology (1/6). The susceptibility of

E. faecium was significantly lower than that of other enterococci, and none of the strains was sensitive to Ciprofloxacin. Among the six strains of E. faecium, one-third (2/6) exhibited resistance to Vancomycin and Teicoplanin, and half of the strains (3/6) were multidrug-resistant (MDR) (

Figure 1a).

2.2.2. Staphylococcus spp

A total of 128 staphylococcal strains were isolated and identified as follows: 71% S. aureus and 29% Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (Co-NS), represented by S. epidermidis (23), S. warneri (4), S. haemolyticus (3), S. hominis (2), S. lugdunesis (1), S. saprophyticus (1), and unspecified Co-NS (3).

Most S. aureus strains were identified in nasal or pharyngeal exudates (29.7%), purulent secretions (18.7%), and ear secretions (17.6%). Most samples were taken from patients in the Otorhinolaryngology (ENT) department, Intensive Care Unit, and Surgery departments (85.7%).

Staphylococci were more frequently isolated in males patients, with a lower proportion for S. aureus than other staphylococcal species.

The frequency of MRSA strains was 33.6%. The MDR rate for S. aureus was 44.5%, lower than CoNS, with an MDR rate of 59.45%. The lowest susceptibility of S. aureus was recorded for Penicillin at 9.4%, Erythromycin at 30%, Daptomycin at 60.1%, and Tetracycline at 39.6%. Susceptibility remained at 85% for CIP, 91.66% for SXT, 94.2% for RIF, and 99% for CN (

Figure 1b).

Table 1.

Distribution of the Bacterial Isolates in the Hospital's Departments.

Table 1.

Distribution of the Bacterial Isolates in the Hospital's Departments.

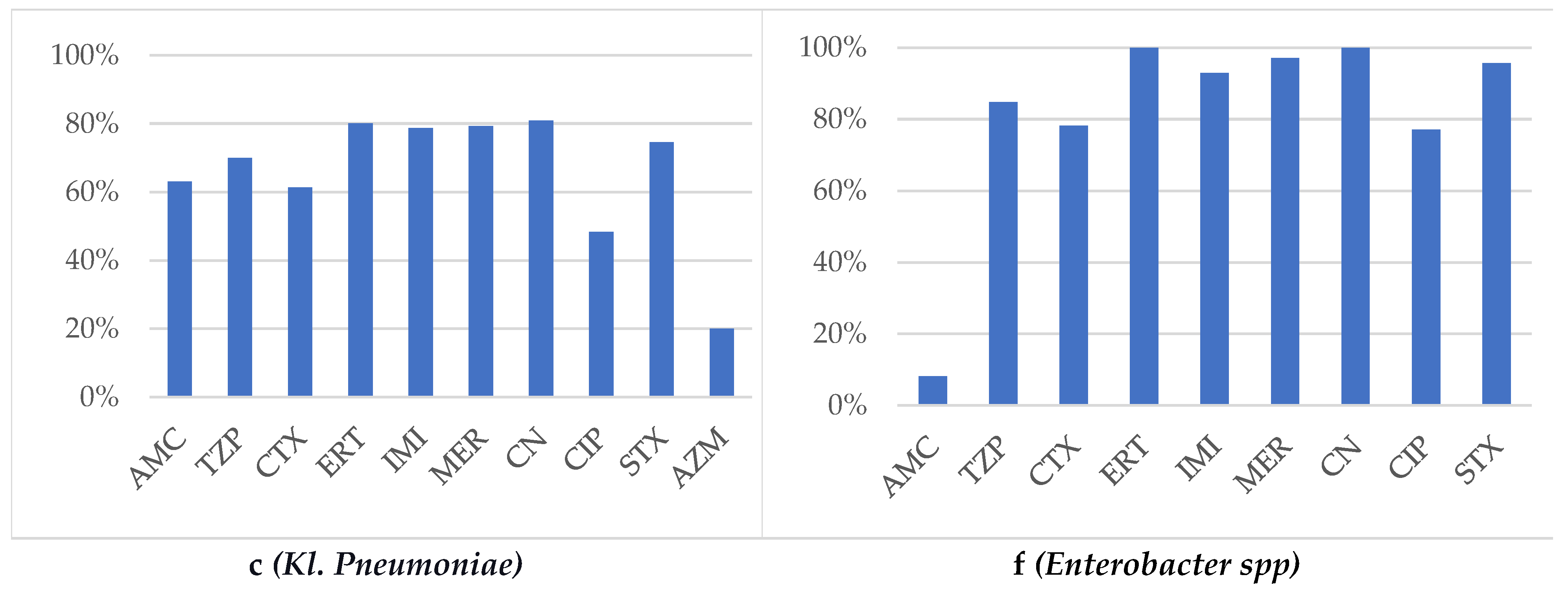

2.2.3. Klebsiella pneumoniae

A total of 182 Klebsiella spp strains were isolated, including 85.16% Kl. pneumoniae, 5.5% Kl. oxytoca, and 9.3% unspecified Kl. spp. Most of the cases (64.55%) were found in male patients, and most of the strains came from urine cultures (69%), sputum (9%), and purulent secretions (6%), mainly from the urology department (43.4%), intensive care (15.38%), pulmonology (9.3%), and internal medicine (9.3%).

The antibiotic susceptibility profile highlighted AMC 69.8%, CTX 64.1%, TZP 75%, CN 80.9%, CIP 48.3%, STX 76.1%. Resistance to Aztreonam was found in 80% of antibiograms, noting that only 25 strains were tested. The resistance rate to carbapenems in

Kl. pneumoniae strains was 21%, while MDR was found in 18.7% and XDR in 7.1% of the isolates (

Figure 1c).

2.2.4. Acinetobacter baumannii

Four strains of

Acinetobacter baumannii were isolated from sputum, urine, and pus from patients in the pulmonology, urology, and intensive care units, equally distributed between males and females (2:2). Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using the CMI method in all these cases, and no antimicrobial resistance was observed for any of the tested antibiotics. However, intermediary pattern for CAZ and TAZ has characterized one from the four strains (

Figure 1 d).

2.2.5. Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas strains were identified in samples taken from 72 patients, of which 71 were Ps. aeruginosa and one was Ps. putida. 60.56% of the patients were males. The main products from which Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated included urine (30.55%), ear secretion (23.6%), purulent secretions (15.27%), and sputum (6.9%), mainly from urology, ENT department, and intensive care units. The CBR rate is 15.5%, and the MDR rate is 6.8%. Among the 50 strains tested, resistance to Aztreonam (AZM) was 30%.

Resistance issues were also identified for CN 22.5%, CIP 15.5%, but susceptibility was maintained for CAZ 91.55%, CEP 91.66%, TZP 92.1%, and CT 95.56% (

Figure 1 e).

2.2.6. Enterobacter spp

Forty-eight strains of

Enterobacter spp were isolated (identified) and distributed as follows: 16.66% E. aerogenes, 50% E. cloacae, and 33.33% unspecified strains. The majority of strains were isolated from males patients (34/48), in urine cultures (25/48), sputum (7/48), wound swabs (6/48), and pus (5/48). They originated predominantly from the urology department (39.85%), ENT department (12.5%), ICU (10.41%), internal medicine (10.41%), pneumology (8.33%), surgery (3/48), and cardiology (2/48). Isolates were also found in the orthopedics, rheumatology, and diabetology departments. ESBL frequency was found to be 14.58% among isolates, and CBR was identified in 2.85% of strains and MDR in 4.16%. The most concerning antibiotic resistance issues were observed with beta-lactams, influencing the following susceptibility profiles: AMC 8.1%, CTX 78.2%, TZP 84.85%, CIP 77%, SMX 95.75%, CN 100% (

Figure 1f).

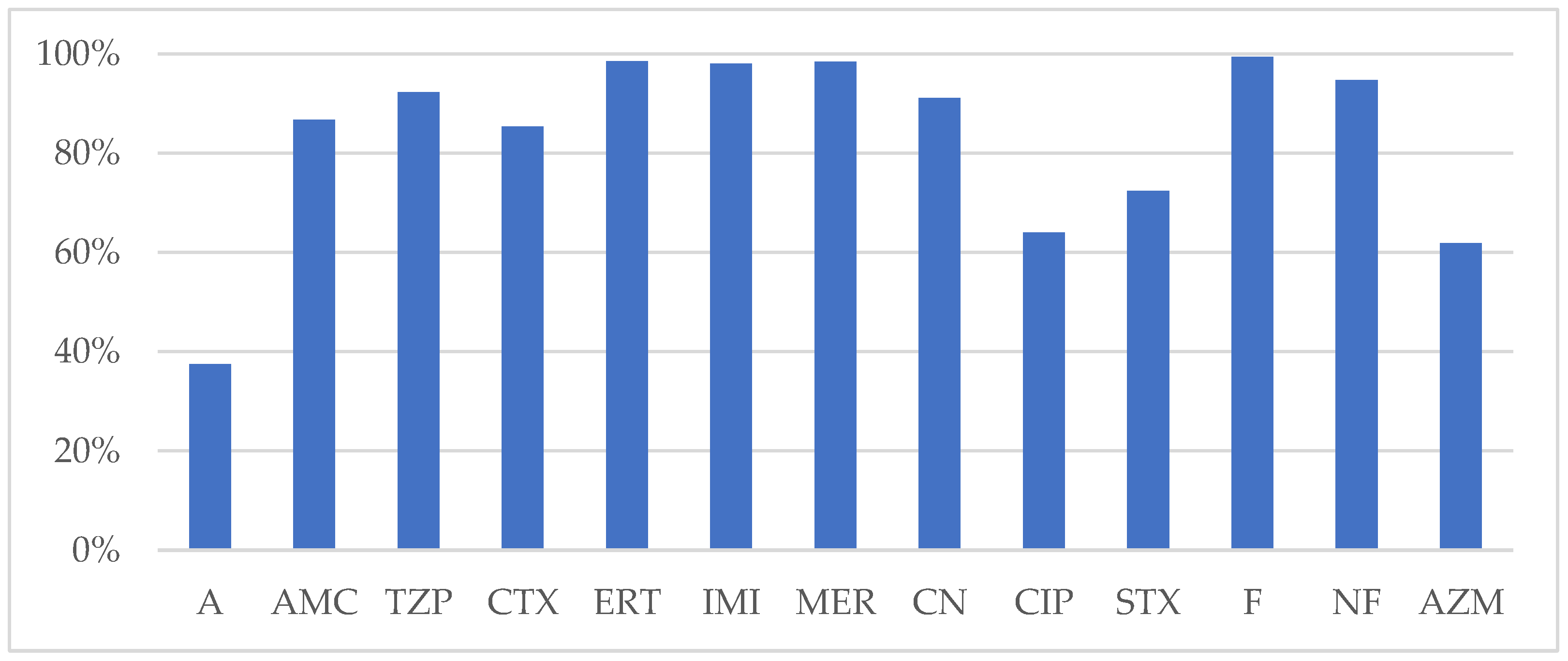

2.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of E. coli

A total of 479 strains of

E. coli were

isolated, with 61.8% from female patients and 89.5% originating from urine cultures

. E. coli strains were obtained from the following departments: urology 37.3%, internal medicine 20.6%, neurology 17.1%, ICU 5.8%, surgery 4.5%, and 14.7% from other departments. Identified antimicrobial resistance issues had frequencies of 15% MDR, 1.6% XDR, 2.6% CBR, and 7.5% ESBL. The lowest susceptibility was

found for AMP (37.5%), AZM (62%), CIP (64%), SXT (72.4%). Better susceptibility was reported for AMC (86.7%), CTX (85.4%), TZP (95.5%), CN (91.4%). Fosfomycin and Nitrofurantoin testing was limited to the

E. coli strains isolated from urine culture, that proved to be susceptible in 100% and 98.25%, respective (

Figure 2).

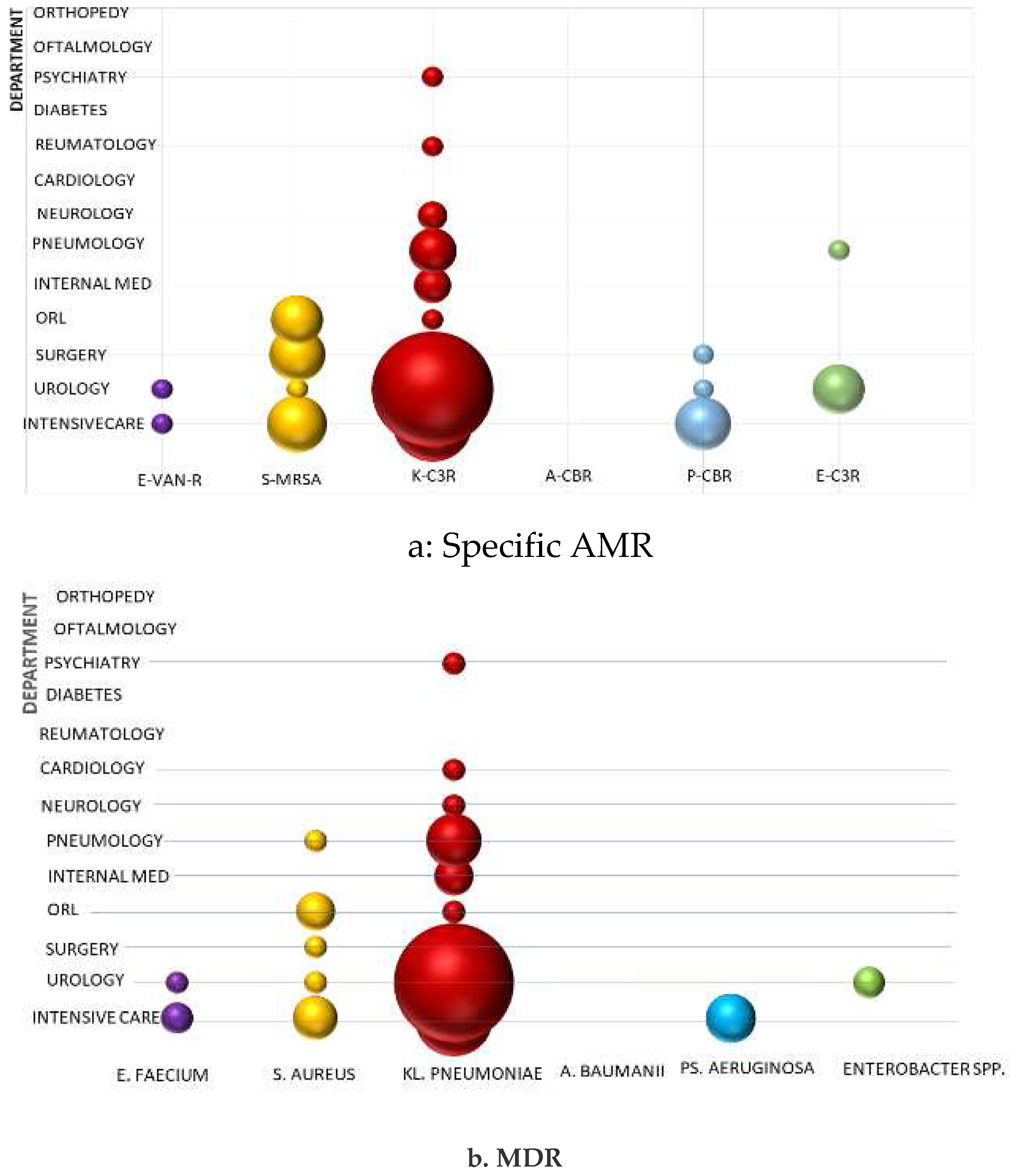

2.4. Spread of ESKAPE Pathogen Resistance in Hospital Wards

Antibiotic resistance issues among ESKAPE pathogens have variable frequency and impact, both regarding the microorganisms surveyed and within each ward, influenced by the characteristics of specific diseases to each specialty.

Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the most concerning public health problems worldwide but CBR has not been identified in any of the hospital's departments. All strains highlighted maintained sensitivity to carbapenems and other commonly tested antibiotics, but a single case was evidenced intermediary pattern, signalling decreasing susceptibility that requires vigilant epidemiological surveillance.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa - Carbapenem-resistant cases were found in isolated instances in the ICU, urology, and surgery departments without being considered a source for healthcare-associated infections. The urology department was the primary source for these isolates, but a sporadically case was also reported from the surgery department.

Enterobacter spp - Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (C3R) was found occasionally, only in the urology department, having the slightest impact among "critical" Gram-negative bacteria on antibiotic stewardship.

The "critical" pathogen

Klebsiella pneumoniae C3R is causing the most problems because it was most identified and is spreading the most in hospital wards. It mainly affects the urology department, then intensive care unit, pneumology, internal medicine, and neurology departments. Epidemiological unrelated cases have also been reported rarely from the ENT, rheumatology, and psychiatry departments (

Figure 3 a).

Among ESKAPE Gram-positive cocci, MRSA draws attention in the intensive care, surgery, and ENT departments, while only a single case was identified in urology. Vancomycin resistance in

Enterococcus faecium is reported in isolated cases in the intensive care and urology departments (

Figure 3 a).

Cumulative specific AMR from each bacterium of ESKAPE group (E. faecium Van-R, MRSA, Ps. Aeruginosa CBR, A. baumannii CBR, Kl. pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp- C3R) account 30.9% and MDR 21%. Multidrug resistance of S. aureus, Kl. pneumoniae and Ps. aeruginosa are highly associated with Methicillin Resistance (χ2 test: p < 0.001), C3R (χ2 test: p<0.001) and CBR (χ2 test: p<0.001), respective. Concerning E. faecium and Enterobacter spp, we found a small number of isolated of and MDR very few strains, that are not considered epidemiologically significant and are not included in the present statistical tests.

3. Discussion

The microbial burden identified in the analysed hospital is low, corresponding to an annual average of 1.95 bacterial strains per hospital bed. This could be explained given the hospital's multidisciplinary profile, which provide health care service mainly to community cases and has a short average stay. Moreover, the hospital low bacteriological charge could be explained by the reorganization of COVID-19 support wards and disturbed specific activities of specialized departments, additionally to the frequent difficulties in properly sampling bacteriological specimens from COVID-19 wards or the limited recommendations of bacteriological investigations, according to the protocols for diagnosing the viral pandemic infection. The challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic for Antibiotic Stewardship and for the activity of the Infection, Prevention and Control of Infections department in hospitals, were determined by the increase in the number of critical cases, a decrease in infection control vigilance, insufficient specialized staff resources, diminished access to microbiological investigations in favour of virological investigations, and the lack of diagnostic and treatment guidelines in the early stages of the pandemic infection [

1,

10,

11].

The WHO report on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance in the European Region highlighted a decrease in E. coli isolates in 2020 compared to previous years, attributed to reduced non-COVID-19 care activities and a decline in AMR surveillance vigilance [

11,

12]. Unlike other countries in the European Region that reported an increase in the frequency of commonly associated healthcare pathogens, such as

Acinetobacter baumannii and

Enterococcus faecium, these issues were not observed in our study. However, monitoring VAN-R enterococci remains a priority for AMR surveillance in our hospital, given the elevated regional prevalence of

Clostridioides difficile infections and the intensive use of oral vancomycin, exerting selective pressure on enteric bacteria [

13].

Like other European countries, resistance to carbapenems in

E. coli and

Enterobacter spp. remains low, below 3%, while the rates of C3R in our study exceed 14%, consistent with the European report [

1]. The complete susceptibility to Fosfomycin of urinal

E. coli isolates justifies the recommendation of this antibiotic in the initial antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated infections, preserving the β-lactam class.

Our study's carbapenem-resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CBR) rate was consistent with the European report (15.5% vs. 17.8%). However, it showed a higher resistance to aminoglycosides (22.5% vs. 9.4%) [

1]. Surprisingly, susceptibility to cephalosporins remained above 90%, maintaining them as a first-line therapeutic option for these infections.

Klebsiella pneumoniae demonstrated the highest frequency among "critical" pathogens but also exhibited the most concerning antibiotic resistance. Resistance rates exceeded 20% for all antibiotic classes, including carbapenems, reaching over 50% for quinolones. Furthermore, the emergence of hypervirulent strains, especially in association with CBR, is linked to antibiotic treatment failure and an elevated mortality rate. Monitoring these variants necessitates using advanced molecular techniques to identify virulence and resistance factors [

14].

Staphylococcus aureus ranks second in the frequency of pathogens with antibiotic resistance risk. The MRSA rate is among the highest in Europe, meaning over 33% of strains. The notably high rate of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains is mainly attributed to intensive community usage of penicillin, macrolides, and tetracyclines. Vancomycin and Linezolid are valuable options for first-line antibiotic treatment in severe invasive infections. Although not within the study's scope, we observed a higher MDR rate in

Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci (Co-N), which colonize the skin, mucous membranes, and environmental surfaces in the community and the hospital. This may contribute to the transmission of antibiotic resistance to Staphylococcus aureus species [

15].

Monitoring and analyzing antimicrobial resistance in the hospital setting are essential for identifying the risks associated with the emergence of "critical" strains and healthcare-associated transmission. Specific resistances within the ESKAPE group, as well as MDR within this group, were more frequently identified in males compared to E. coli, which predominantly originated from females. Both Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens and E. coli were predominantly associated with urinary tract infections in most cases. This observation could be considered in urology department for the risk evaluation in the first-line antibiotic treatment decision of urinary infections, together with predictive clinical scores, such as CarbaSCORE, Tumbarello score, Duke score or machine learning models [16, 17,18].

The AMR profile in the present analysis expresses the antibiotic use in community, additional to antibiotic prescription in the hospitals from our region. This is the first surveillance report of AMR in the Emergency Military Hospital "Dr. Aristide Serfioti" from Galati, developed to understand the local impact of COVID-19 on bacterial charge, diversity, frequency, and antibiotic resistance, for updating the regional antibiotic stewardship strategy. Revising the clinical protocols for diagnostic and treatment in each department, intensifying the bacteriological samples collection, improving the microbiological diagnostic techniques for AMR identification, including high technologies of molecular investigations and point of care antimicrobial resistance tests are highly interests for the near future stewardship. Systematic epidemiological monitorization and control of hospital environment, hand hygiene procedures stimulation, strictly assurance of safe medical procedures and continuing education are ongoing necessary components of the antibiotic stewardship program.

4. Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of the isolated bacterial strains was conducted in the Microbiology Laboratory of the Emergency Military Hospital " Dr. Aristide Serfioti" in Galati, derived from various biological samples obtained from hospitalized patients. The hospital is found in the Southeast region of Romania, on the eastern border of the European Union, and includes surgical departments (75 beds), medical departments (100 beds), and an intensive care unit (15 beds).

Escherichia coli and microorganisms in the ESKAPE group had their antibiotic susceptibility evaluated.

Escherichia coli was included in the analysis due to its frequent association with horizontal gene transfer of resistance genes from other

Enterobacterales, potentially reflecting the resistance profile of

Klebsiella pneumoniae or

Enterobacter spp, both of which are part of the ESKAPE group [

19].

The study was conducted from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2022. This timeframe coincides with the hospital focus on COVID-19 support, meaning that the hospital provided healthcare to COVID-19 patients, along withng healthcare assistance to general population, mostly emergencies.

4.1. Microbiological Bacterial Identification Procedures

According to current work procedures, bacterial isolation was performed by inoculating biological samples either "in sector" or "by exhaustion" on solid media, including Columbia blood agar, Chapman agar, and MacConkey agar (GRASO Biotech, Oxoid - Thermo Scientific, USA), followed by incubation for 24-48 hours at a temperature of 37°C. Biochemical identification of isolated bacterial strains was done through multi-testing and the automatic Vitek 2 Compact method (bioMérieux-l'Etoile).

4.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was conducted using either the classic disk diffusion method or the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method with the Vitek 2 Compact automated system, adhering to the current CLSI standards of the working period. The choice of the MIC testing method was contingent upon laboratory availability, the clinical severity of the patient, and the need for an urgent result, particularly in cases of multidrug-resistant bacteria or discrepancies found in the disk diffusion testing.

Depending on the isolated bacteria, specific sets of antibiotics were selected following the type of sample and the level of resistance exhibited by the bacterial strain. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) represents the lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits bacterial growth, expressed in μg/mL.

Bacterial strains underwent systematic testing with various antibiotics, including Penicillin's (P - penicillin-10 U, A- ampicillin-10µg), β-lactam combination agents (AMC- amoxicillin-clavulanate-20/10, TZP – piperacillin-tazobactam-100/10 µg), cephems (CXM- cefuroxime-30 µg; FOX - cefoxitin -30 µg, CTX- cefotaxime -30 µg, CAZ-ceftazidime, FEP-cefepime 30 µg), monobactams (AZM-aztreonam-30 µg), carbapenems (IMP-imipenem -10 µg, MEM- meropenem-10 µg, ERT-ertapenem-10 µg), fluoroquinolones (CIP- ciprofloxacin-5µg), macrolides (E-erythromycin- 15 µg), TE -tetracycline- 30 µg, lincosamides (DA-clindamicyn); ansamycins (RIF- rifampicine -5 µg), sulfamides (SXT – trimethoprim/suphamethoxazole - 25 µg), nitrofurans (NF-nitrofurantoin- 300µg), aminoglycoside (CN-gentamicin-10 µg), glycopeptides (VAN- vancomycin- 30µg) and oxazolidinones (LNZ-linezolid- 30 µg).

The disk diffusion testing method used Oxoid Antimicrobial Susceptibility Disks from Thermo Scientific, USA, and Mast Group Ltd from the U.K. For minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing, bioMérieux-l'Etoile products were employed. Only acquired antimicrobial resistance was taken into consideration, excluding intrinsic resistance.

Results of susceptibility for each antibiotic were expressed as resistant, intermediate, or sensitive, and interpretation was made by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) for the respective testing year [

20,

21,

22].

4.3. Quality Control

Quality control procedures incorporated the use of reference strains for both identification and antibiotic resistance testing. The reference strains included Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, ATCC 25923; E. coli ATCC 25922; Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Enterococcus casseliflavus ATCC 700327, Enterobacter hormaechei ATCC 700323, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia ATCC 176666.

4.4. Data Collection, Interpretation, and Statistical Analysis

After removing duplicates, the antibiotic susceptibility test results were input into the electronic database of the laboratory. Analysis of the antibiotic susceptibility profile facilitated the identification of significant resistance issues and risks posed for healthcare-associated infections in the hospital.

Microorganisms that have minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) above the standard cut-off levels are resistant to antibiotics. According to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), a microorganism classified as sensitive (S) indicates therapeutic success with standard antibiotic doses, intermediate (I) responds to therapy after exposure to higher antibiotic concentrations, and resistant (R) exhibits therapeutic failure even after elevated antibiotic concentrations [

23].

Multidrug resistance (MDR) defines non-susceptibility to at least one antibiotic from two or more classes, while maintaining susceptibility to at least one antibiotic from three or more categories. Extensive drug resistance (XDR) signifies non-susceptibility to at least one antibiotic from all categories but retains susceptibility to one or two categories. Pandrug resistance (PDR) characterizes non-susceptibility to all antimicrobial agents, emphasizing that bacterial isolates should be tested against all antimicrobial agents by the recommended standards [

24].

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL), is considered in the case of

Enterobacterales, bacteria resistant simultaneously to penicillins and cephalosporins [

25].

ESBL was detected using the double-disc synergy test (Cefotaxime–Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid) and the Vitek 2 Compact Software.

Aztreonam has not been available in Romania, but data on the susceptibility could base the recommendations of the local antimicrobial treatment protocols.

Carbapenem resistance (CBR) is defined as resistance to any carbapenems or the documentation of carbapenemase enzyme production, which inactivates carbapenems and other beta-lactam antibiotics [

26].

Methicillin resistance in

S. aureus (MRSA) is an oxacillin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of greater than or equal to 4 micrograms/mL. Cefoxitin disk diffusion was used to determine MRSA, and a test result less than 22 mm was considered resistant [

27].

Resistance of enterococci to Vancomycin (Van-R) is defined by intrinsic or acquired resistance in enterococci, often through the transfer of resistance plasmids, with VanA and vanB being the most well-known [

26]. Molecular tests for determining these genes were not available.

Statistical analysis of the data used version 19 of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Descriptive statistics tests were applied to determine frequency, incidence, and prevalence. The χ2 test was used for comparing categorical variables, considering a significance level of p<0.01.

Limits of the Study

Hemocultures accounted for only 1% of the total positive samples and 3.18% of them are categorised in ESKAPE group. Therefore, comparing the antimicrobial resistance profile resulting from our study with reference data reported by representative laboratories that monitor antibiotic resistance in epidemiological surveillance networks for invasive bacterial strains, has limited significance [

28]. This limitation in reporting resistance data is justified by the need to reduce variability determined by sampling and interpretation. Non-invasive isolates are subject to variability in clinical interpretation, which varies between regions and countries. The antibiotic consumption was not included in the present study but should be correlated with the antimicrobial resistance pattern of the hospital.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., C-M.V.; methodology, A-V.I, M.A., C-N.D.; software, I.D., C-S.S; validation, M.A., C-M. V. and A-V-I.; formal analysis, I.D..; C-N.D.; investigation, C-M.V., I.D.; resources, C-M.V. and C-S. S.; data curation, A-V.I.; C-N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C-M.V., C-S.S, A-V.I., I.D., C-N.D.; writing—review and editing, M.A.; visualization, C-S.S.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, C-M.V., M.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Emergency Military Hospital " Dr. Aristide Serfioti" in Galati. The study did not require ethical approval, as our retrospective study used laboratory management which regularly collected data from the databases. The consent for the use of personal data was given by each patient as a routine procedure of the hospital health care provision.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the research staff of “Dunarea de Jos” University” Galati for the financial support for the publishing of our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Distribution of Isolated Microbial Categories in the Hospital during the Pandemic Years.

Figure A1.

Distribution of Isolated Microbial Categories in the Hospital during the Pandemic Years.

Figure A2.

Distribution of Bacterial Isolates by Tested Biological Sample. Legend: UC- urine culture; Pu- pus; RS- respiratory secretions (sputum/bronchoalveolar lavage); OS- ear secretion; US- urethral secretion; HC- haemoculture; NF- nasal/ pharyngeal secretion; CC- coproculture.

Figure A2.

Distribution of Bacterial Isolates by Tested Biological Sample. Legend: UC- urine culture; Pu- pus; RS- respiratory secretions (sputum/bronchoalveolar lavage); OS- ear secretion; US- urethral secretion; HC- haemoculture; NF- nasal/ pharyngeal secretion; CC- coproculture.

References

- Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2023 - 2021 data. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and World Health Organization; 2023. available at http://apps.who.int/iris.

- O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations. The review on antimicrobial resistance. 2016. Available from http://amrreview.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf [Accessed June 11, 2023].

- Venkateswaran, P.; Vasudevan, S.; David, H.; Shaktivel, A.; Shanmugam, K.; Neelakantan, P.; Solomon, A. P. Revisiting ESKAPE Pathogens: virulence, resistance, and combating strategies focusing on quorum sensing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1159798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkő, R.; Gajdács, M.; Matuz, M.; Bodó, G.; Lázár, A.; Hajdú, E.; Papfalvi, E.; Hannauer, P.; Erdélyi, P.; Pető, Z. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of ESKAPE Pathogens Isolated in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Hungary: A 5-Year Retrospective Survey. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L. B. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J Infect Dis 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE pathogens in the environment: Antibiotic resistance status, community-acquired infection and risk to human health. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2022, 244, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S. H. The state of current research on COVID-19 and antibiotic use: global implications for antimicrobial resistance. J Health Popul Nutr 2023, 42, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (2023), Embracing a One Health Framework to Fight Antimicrobial Resistance, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Loyola-Cruz, M.; Gonzalez-Avila, L. U.; Martínez-Trejo, A.; Saldaña-Padilla, A.; Hernández-Cortez, C.; Bello-López, J. M.; Castro-Escarpulli, G. ESKAPE and Beyond: The Burden of Coinfections in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pathogens 2023, 12 (5). [CrossRef]

- National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. COVID-19: U.S. Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance, Special Report 2022; National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Micheli, G.; Sangiorgi, F.; Catania, F.; Chiuchiarelli, M.; Frondizi, F.; Taddei, E.; Murri, R. The Hidden Cost of COVID-19: Focus on Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe/European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2022 – 2020 data. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022.

- Iancu, A.-V.; Arbune, M.; Zaharia, E.-A.; Tutunaru, D.; Maftei, N.-M.; Peptine, L.-D.; Țocu, G.; Gurău, G. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of Enterococcus spp.: A Retrospective Study in Hospitals of Southeast Romania. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xie, M.; Liu, X.; Heng, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Chan, E. W.; Zhang, R.; Yang, G.; Chen, S. Molecular mechanisms underlying the high mortality of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae and its effective therapy development. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontjes, K. J.; Gibson, K. E.; Lansing, B. J.; Mody, L.; Cassone, M. Assessment of race and sex as risk factors for colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms in six nursing homes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020, 41, 1222–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teysseyre, L.; Ferdynus, C.; Miltgen, G.; Lair, T.; Aujoulat, T.; Lugagne, N.; Allou, N.; Allyn, J. Derivation and validation of a simple score to predict the presence of bacteria requiring carbapenem treatment in ICU-acquired bloodstream infection and pneumonia: CarbaSCORE. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. W.; Anderson, D. J.; May, D. B.; Drew, R. H. Utility of a clinical risk factor scoring model in predicting infection with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae on hospital admission. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013, 34, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chakraborty, T.; Doijad, S.; Falgenhauer, L.; Falgenhauer, J.; Goesmann, A.; Hauschild, A. C.; Schwengers, O.; Heider, D. Prediction of antimicrobial resistance based on whole-genome sequencing and machine learning. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, D. M. P.; Forde, B. M.; Kidd, T. J.; Harris, P. N. A.; Schembri, M. A.; Beatson, S. A.; Paterson, D. L.; Walker, M. J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 30th informational supplement, CLSI Document M100-S30, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Pa, USA, 2020. https://clsi.org/media/3481/m100ed30_sample.pdf.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 31th informational supplement, CLSI Document M100-S31, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Pa, USA, 2021. https://clsi.org/media/z2uhcbmv/m100ed31_sample.pdf.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 32th informational supplement, CLSI Document M100-S32, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Pa, USA, 2022. https://clsi.org/media/z2uhcbmv/m100ed31_sample.pdf.

- Kalpana, S.; Lin, W. Y.; Wang, Y. C.; Fu, Y.; Lakshmi, A.; Wang, H. Y. Antibiotic Resistance Diagnosis in ESKAPE Pathogens-A Review on Proteomic Perspective. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A. P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R. B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M. E.; Giske, C. G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J. F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America Antimicrobial-Resistant Treatment Guidance: Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023; Version 3.0. Available at https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/amr-guidance/. Accessed 12 AUG 2023.

- Sanchini, A. Recent Developments in Phenotypic and Molecular Diagnostic Methods for Antimicrobial Resistance Detection in. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, T.; Hailemariam, M. Prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus in Africa in one health approach: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe/European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2022 – 2020 data. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).