Appendix A: Operator Formalism and Spinor Field

Construction

A.1 Overview

A central feature of the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model is the emergence of fermion-like spinor fields from a purely classical elastic membrane. In this appendix, we detail how the classical displacement field – whose dynamics are governed by a high-order wave equation including fourth- and sixth-order spatial derivatives, damping, nonlinear self-interactions, Yukawa-like couplings, and external forces – is promoted to an operator via canonical quantisation. We also define its conjugate momentum and introduce a complementary out-of-phase field . A bimodal decomposition of these fields subsequently yields a two-component spinor , which forms the foundation for the emergence of internal gauge symmetries.

A.2 Canonical Quantisation of the Displacement Field

A.2.1 Classical Preliminaries

The classical displacement field

describes the elastic deformation of the four-dimensional membrane. Its dynamics are derived from a Lagrangian density that incorporates higher-order spatial derivatives to capture both bending and ultraviolet (UV) regularisation. A representative Lagrangian density is

where:

is the effective mass density,

is the scale-dependent baseline elastic modulus,

represents local stiffness variations,

The term yields, via integration by parts, the sixth-order term ,

is the potential energy (e.g. or more complex forms incorporating nonlinearities such as ),

includes additional interaction terms such as the Yukawa-like coupling .

Damping (

) and external forcing

are introduced separately or via effective dissipation functionals in the complete equation of motion:

A.2.2 Conjugate Momentum

The conjugate momentum is defined as

A.2.3 Promotion to Operators

In quantising the theory, the classical field

and its conjugate momentum

are promoted to operators

and

acting on a Hilbert space

. They satisfy the canonical equal-time commutation relation

with all other commutators vanishing [

16,

17]. This structure remains valid when higher-order derivatives (leading to

and

terms) and scale-dependent parameters are included.

A.2.4 Normal Mode Expansion and Dispersion Relation

In a near-homogeneous scenario, the operator

is expressed in momentum space as

Substituting this expansion into the classical equations of motion yields the modified dispersion relation. For plane-wave solutions

, one obtains

The inclusion of the term, arising from the contribution, provides enhanced UV regularisation by strongly suppressing high-wavenumber fluctuations.

A.2.5 Hamiltonian Operator

The Hamiltonian operator is constructed from the Lagrangian as

where represents the operator form of the interaction terms (including, for instance, the Yukawa-like coupling ). To ensure that all derivative terms (up to third order, corresponding to ) are well defined, the domain of is chosen as a Sobolev space (or higher). With appropriate boundary conditions (e.g. fields vanishing at infinity), integration by parts guarantees that is self-adjoint and its spectrum is real and bounded from below.

A.3 Bimodal Decomposition and Spinor Construction

To capture additional internal degrees of freedom, we introduce a complementary field

, interpreted as the out-of-phase (or quadrature) component of the membrane’s displacement. We define two new real fields via the linear combinations

These represent the in-phase and out-of-phase components, respectively. They are then combined into a two-component spinor operator

By imposing appropriate (anti)commutation relations between and , one can demonstrate—by analogy with Fermi–Bose mappings in certain lower-dimensional systems—that the spinor exhibits chiral substructures. These substructures are essential for the emergence of internal gauge symmetries.

A.4 Self-Adjointness and Path Integral Formulation

The Hamiltonian operator is shown to be self-adjoint by verifying that all higher-order derivative terms are well defined on the chosen Sobolev space (here, or higher) and by imposing suitable boundary conditions (e.g. fields vanishing at infinity). This self-adjointness is essential for ensuring a real energy spectrum and the stability of the quantised theory.

A complete path integral formulation can then be constructed. The transition amplitude between field configurations is given by

Integrating out the momentum degrees of freedom yields the configuration-space path integral, which serves as the basis for further extensions, including the incorporation of gauge fields.

A.5 Extended Path Integral for Gauge Fields

To incorporate internal gauge symmetries, we augment the effective action with gauge field contributions. For a gauge field

(where

a indexes the generators), the covariant derivative is defined as

with

representing the generators (for example,

for SU(2) or

for SU(3)) and

g the gauge coupling constant. The corresponding field strength tensor is given by

The gauge symmetry is quantised by imposing a gauge-fixing condition (e.g. the Lorentz gauge

) and by introducing Faddeev–Popov ghost fields

and

. The resulting gauge-fixed path integral is

where includes the original STM Lagrangian, the gauge field Lagrangian, and the ghost contributions.

A.6 Ontological meaning of the bimodal spinor

This appendix clarifies the physical interpretation and underlying ontology of the two-component spinor employed in the STM model, explaining its emergence directly from the dynamics of a four-dimensional elastic spacetime membrane.

A.6.1 Spinor Definition and Physical Interpretation

In the STM framework, the fundamental spinor field is explicitly constructed from two measurable elastic deformation modes of the spacetime membrane. We define the spinor as:

where u and represent orthogonal displacements of the membrane.

Each component is physically real and measurable:

In-phase mode: Represents a local patch of the membrane moving synchronously ("up and down") with the bulk spacetime background deformation.

Quadrature (out-of-phase) mode: Represents the same local patch moving with a 90° phase lag, achieving its maximum displacement precisely when the in-phase component is at zero displacement.

Together, these two components form a classical standing-wave system analogous to the two orthogonal polarisations of electromagnetic waves in a cavity. Crucially, the indivisibility of these modes—no local perturbation can excite one mode independently without affecting the other—is the fundamental elastic origin of quantum spin-½ behaviour.

A.6.2 Local Gauge Phase and Emergent Electromagnetism

The spinor supports a local gauge invariance expressed through a point-wise phase transformation:

This gauge transformation corresponds physically to a local rotation of the oscillation ellipse formed by and . To ensure that physical predictions remain invariant under such local rotations, an additional compensating field (gauge connection) naturally emerges, identifiable with the electromagnetic potential. Hence, gauge symmetry in the STM model has a direct and intuitive geometric-elastic meaning.

A.6.3 Hidden Elastic Variables and Deterministic Origin

At a microscopic level, the instantaneous configuration of the bimodal spinor is entirely determined by the underlying displacement and velocity fields of the membrane. Consequently, the STM model maintains strict determinism—its quantum-like behaviour emerges only through coarse-graining and ensemble averaging. The macroscopically observable quantum spinor thus encodes only the envelope amplitude and relative phase, masking the deterministic hidden variables of the underlying elastic fields.

A.6.4 Spin Encoding and the Bloch Sphere

Choosing a particular quantisation axis (e.g., along the -direction), spin-up and spin-down states correspond explicitly to membrane oscillation ellipse orientations:

Intermediate orientations of the ellipse naturally map onto the continuum of quantum states represented by points on the standard quantum Bloch sphere.

A.6.5 Measurement as Boundary-Condition Selection

In the STM interpretation, quantum measurement is fundamentally a boundary-condition selection process. For instance, a Stern–Gerlach analyser temporarily modifies local boundary conditions—specifically altering local stiffness and membrane boundary dynamics—so that only oscillation ellipses with particular orientations can pass through. Thus, measurement outcomes reveal pre-existing elliptical orientations encoded at emission, consistent with a deterministic hidden-variable interpretation, rather than spontaneously creating measurement outcomes upon observation.

A.7 Summary and Outlook

In summary, the operator quantisation scheme for the STM model proceeds as follows:

Displacement Field Promotion:

The classical displacement field and its conjugate momentum are promoted to operators and on a Hilbert space. The domain is chosen as a suitable Sobolev space (e.g. or higher) to ensure that all derivatives up to third order (which produce the term) are well defined.

Complementary Field and Spinor Construction:

A complementary field is introduced. By forming the in-phase and out-of-phase combinations and , a two-component spinor is constructed. This spinor structure is central to the emergence of internal gauge symmetries.

Self-Adjoint Hamiltonian:

The Hamiltonian includes kinetic, fourth-order, and sixth-order spatial derivatives, along with potential and interaction terms. It is shown to be self-adjoint under appropriate boundary conditions, ensuring a real and bounded-below energy spectrum.

Path Integral Formulation:

A configuration-space path integral is derived from the action , serving as the basis for calculating transition amplitudes and for extending the formulation to include gauge fields and ghost terms.

This comprehensive operator formalism provides a robust foundation for the STM model’s quantum framework, opening the door to further theoretical investigations and experimental tests of how deterministic elasticity can give rise to quantum-like behaviour.

Appendix B: Derivation of the STM Elastic-Wave Equation and

External

Force

This appendix supplies an explicit, yet compact, route from a covariant elasticity energy functional to the fourth- and sixth-order terms, the nonlinear self-interaction, the Yukawa-like coupling and the damping force that together define the Space-Time Membrane (STM) partial differential equation (PDE). Every algebraic step needed for independent reconstruction is shown, but purely repetitious index contractions have been suppressed for brevity.

B.1 Field content and notation

| Symbol |

Meaning |

|

space-time

coordinates; background metric

|

|

small displacement of the four-dimensional membrane

(co-moving gauge after variation) |

|

linear strain tensor |

|

two-component spinor obtained from the bimodal

decomposition (Appendix A) |

Latin indices denote spatial components; repeated indices are summed.

B.2 Elastic energy density

For an

isotropic and

centrosymmetric medium the quadratic strain invariants are

Higher-gradient rigidity is captured by the

unique parity-even scalars that survive rotational averaging:

where is the baseline modulus and provides ultraviolet regularisation.

B.3 Total action and conservative variation

The conservative sector of the action is

with

.

B.3.1 Quadratic strain → no fourth- or sixth-order terms

Varying reproduces the familiar second-order elastic wave equation. Because the STM model targets quantum-like dispersion, we keep the result implicit and focus on the higher-gradient pieces.

B.3.2 The term →

so it contributes to the Euler–Lagrange equation.

giving . The sign ensures a positive-definite contribution to the Hamiltonian (Appendix O).

B.3.4 Non-linear and Yukawa terms

These produce and in the field equation.

B.4 Dissipation via a Rayleigh functional

Damping is introduced

after the conservative variation by the Rayleigh dissipation density

Adding the generalised force

to the conservative Euler–Lagrange result yields

where the position-dependent

stiffness perturbation

arises (Appendix H) when rapid sub-Planck oscillations are coarse-grained out of the quadratic bending energy.

B.5 External force

All residual contributions—including boundary tractions, laboratory forcing, or feedback terms used in metamaterial analogues—can be packaged as an

external potential . Varying that functional gives

which is simply added to the right-hand side of the master PDE whenever required by a specific experiment or numerical set-up.

B.6 Summary

The fourth-order operator is the Euler–Lagrange image of the quadratic bending invariant .

The sixth-order operator follows analogously from and is essential for ultraviolet convergence.

Non-linear self-interaction and Yukawa-like spinor coupling appear directly from polynomial and bilinear potential terms.

Linear damping derives from the Rayleigh-type functional .

Any additional laboratory or astrophysical forcing enters through .

Assembling the results of B.3.2–B.5, the full Space–Time Membrane wave equation reads

where:

is the mass density (B.3);

and arise from the fourth- and sixth-order invariants (B.3.2, B.3.3);

and are the nonlinear self-interaction and Yukawa-like terms (B.3.4);

is the Rayleigh damping coefficient (B.4);

is the coarse-grained stiffness perturbation from fast modes (B.4);

is any external force (B.5).

This single PDE encapsulates all conservative elastic terms, damping, nonlinearity, spinor coupling and external forcing used throughout the main text and Appendices D–H.

Appendix C: Gauge symmetry emergence and CP

violation

C.1 Overview

The Space–Time Membrane (STM) model naturally gives rise to internal gauge symmetries through the elastic dynamics of the membrane. By performing a bimodal decomposition of the displacement field (as described in Appendix A), a two-component spinor is obtained. The internal structure of allows for local phase invariance, which necessitates the introduction of gauge fields. In this appendix, we derive the gauge structures corresponding to U(1), SU(2), and SU(3), including the construction of covariant derivatives, the formulation of field strength tensors, and the implementation of gauge fixing via the Faddeev–Popov procedure.

C.2 U(1) Gauge Symmetry

Local Phase Transformation and Covariant Derivative:

Consider the two-component spinor

derived from the bimodal decomposition. A local U(1) phase transformation is given by:

where

is an arbitrary smooth function. To maintain invariance of the kinetic term in the Lagrangian, we replace the ordinary derivative with a covariant derivative defined by:

where is the U(1) gauge field and e is the gauge coupling constant.

Field Strength Tensor:

The corresponding U(1) field strength tensor is defined as:

Under the gauge transformation,

the field strength tensor remains invariant.

Gauge Fixing and Ghost Fields:

For quantisation, it is necessary to fix the gauge. A common choice is the Lorentz gauge, . The Faddeev–Popov procedure is then employed to introduce ghost fields and that ensure proper treatment of gauge redundancy in the path integral formulation.

C.3 SU(2) Gauge Symmetry

Local SU(2) Transformation:

Assume that the spinor

exhibits a chiral structure such that its left-handed component,

, transforms as a doublet under SU(2). A local SU(2) transformation is expressed as:

with () being the Pauli matrices, and representing the local transformation parameters.

Covariant Derivative for SU(2):

To maintain invariance under this transformation, the covariant derivative is defined as:

where are the SU(2) gauge fields and is the SU(2) coupling constant.

Field Strength Tensor for SU(2):

The field strength tensor associated with the SU(2) gauge fields is given by:

where are the antisymmetric structure constants of SU(2).

Gauge Fixing:

Imposing the Lorentz gauge,

, and applying the Faddeev–Popov procedure, ghost fields

and

are introduced with a ghost Lagrangian of the form:

C.3.1 Electroweak Mixing, the Boson, and CP Violation via Zitterbewegung

In the STM framework, electroweak symmetry breaking and the emergence of the neutral Z boson can be naturally explained through interactions between the bimodal spinor field residing on one face of the membrane and the corresponding bimodal antispinor field located on the opposite face (the "mirror universe").

Specifically, the displacement field

couples these spinor fields through an interaction Lagrangian of the form:

where:

represents Yukawa-like coupling constants between generations .

is the membrane displacement field, whose vacuum expectation value (VEV), , generates effective fermion masses.

Complex phase shifts arise naturally due to rapid oscillatory interactions—known as zitterbewegung—between the spinor and the mirror antispinor .

When the displacement field

acquires a vacuum expectation value (VEV), denoted

, this interaction yields an effective fermion mass matrix of the form:

where the phases become averaged into constant effective phases upon coarse-graining.

Electroweak Mixing and Emergence of the Z Boson:

To clearly illustrate the connection with electroweak theory, consider the gauge fields emerging from the bimodal spinor structure. Initially, the theory features separate U(1) and SU(2) gauge symmetries, represented by gauge fields

(U(1)) and

(SU(2)). Through the process described above—where the membrane’s displacement field acquires a vacuum expectation value

—mass terms arise for specific gauge bosons. Explicitly, electroweak mixing occurs via a linear combination of the neutral gauge fields

(from SU(2)) and

(from U(1)):

where is the Weinberg angle, dynamically determined by membrane parameters, and is the original U(1) gauge field. The gauge boson corresponding to the acquires mass directly from the membrane’s elastic structure, analogous to the conventional Higgs mechanism but derived here entirely from deterministic elastic interactions rather than from an additional scalar field.

Emergence of CP Violation:

Under a combined charge conjugation–parity (CP) transformation, the spinor fields transform approximately as:

with analogous transformations applied to the mirror antispinor

. Due to the presence of nontrivial phases induced by the zitterbewegung interaction between spinor and antispinor fields, the effective fermion mass matrix

is generally complex. Diagonalising this matrix yields physical fermion states with mixing angles and phases analogous to the experimentally observed CKM matrix, thus naturally introducing CP violation into the STM framework.

Summary:

Gauge boson masses and electroweak mixing angles emerge naturally via vacuum expectation values of the membrane displacement field.

Z bosons arise explicitly from the SU(2) × U(1) gauge field mixing.

CP violation is introduced through the deterministic zitterbewegung interaction between spinors and antispinors across the membrane, producing effective Yukawa couplings with nonzero complex phases.

Although the underlying framework clearly illustrates how CP violation emerges deterministically, a rigorous derivation of chiral anomalies, weak parity violation, and related effects, such as neutrino mass generation via a see-saw mechanism, would require further detailed analysis, including explicit consideration of triangular loop diagrams within the STM framework.

C.4 SU(3) Gauge Symmetry

Local SU(3) Transformation:

For the strong interaction, the spinor

is assumed to carry a colour index and transform as a triplet under SU(3). A local SU(3) transformation is given by:

where () are the Gell–Mann matrices, and are the transformation parameters.

Covariant Derivative for SU(3):

The covariant derivative is defined as:

where are the SU(3) gauge fields and is the SU(3) coupling constant.

Field Strength Tensor for SU(3):

The SU(3) field strength tensor is defined by:

where are the structure constants of SU(3).

Gauge Fixing:

The Lorentz gauge

is imposed, and ghost fields

and

are introduced via the Faddeev–Popov procedure. The ghost Lagrangian is then:

C.4.1 Physical Interpretation — Linked Oscillators and Confinement:

In the main text (

Section 3.1.2), the strong force is depicted by analogy with a “linked oscillator” network, wherein each local site carries a colour-like degree of freedom. From the perspective of continuum gauge theory, this classical picture emerges naturally once we require that

carry a local SU(3) index and that neighbouring “sites” (or regions) remain elastically coupled under deformations. In essence, each SU(3) gauge connection

plays the role of an “elastic link” constraining colour charges, which becomes increasingly stiff (i.e. confining) with separation.

Mathematically, the field strength

enforces local colour gauge invariance, just as tension in a chain of coupled oscillators enforces synchronous motion. When two colour charges are pulled apart, the membrane’s elastic energy—now interpreted as the non-Abelian gauge field energy—rises linearly with distance (up to corrections from real or virtual gluon-like modes). This provides a deterministic analogue of confinement: it is energetically unfavourable for a single “coloured oscillator” to exist in isolation, so colour remains bound. Thus, the formal gauge-theoretic description of SU(3) in this appendix and the intuitive “linked oscillator” analogy of

Section 3.1.2 are two views of the same phenomenon: a deterministic continuum mechanism underpinning the strong interaction.

C.4.2 Derivation of SU(3) Colour Symmetry

In the STM model, spacetime is described as an elastic four-dimensional membrane whose displacement field,

, obeys a high-order partial differential equation:

where is the effective mass density, is a scale-dependent elastic modulus, accounts for local variations in stiffness, and controls the higher-order spatial derivative terms that serve to regularise ultraviolet divergences.

At sub-Planck scales, the membrane exhibits rapid deterministic oscillations. Coarse-graining these fast modes yields a slowly varying envelope. Initially, the displacement field is decomposed bimodally:

which can be combined into a two-component spinor,

This spinor naturally exhibits a U(1) symmetry under local phase rotations. However, the strong interaction is described by an SU(3) symmetry, necessitating an extension to three internal degrees of freedom.

Extending to Three Components

The inclusion of higher-order derivative terms (

and

) implies a richer dynamical structure than a simple two-mode system. For example, in a one-dimensional analogue, an equation such as

yields a dispersion relation

that supports a multiplicity of normal modes. In four dimensions, such higher-order dynamics may naturally allow for three distinct, independent oscillatory modes. Label these as

,

, and

(metaphorically corresponding to “red”, “green”, and “blue”). Then the displacement field may be expressed as:

which is recast as a three-component field,

This field now naturally transforms under SU(3) via unitary matrices with determinant 1, preserving the norm .

Anomaly Cancellation and Topological Constraints

A consistent, anomaly-free gauge theory requires that the contributions from all fields cancel potential gauge anomalies. In the Standard Model, the colour triplet structure of quarks ensures anomaly cancellation within QCD. In the STM model, if the three vibrational modes couple to emergent fermionic degrees of freedom analogously to quark fields, then both energy minimisation and anomaly cancellation considerations naturally favour an SU(3) symmetry. Moreover, topological constraints—for instance, those imposed by suitable boundary conditions or by a compactified membrane geometry—can enforce the existence of exactly three independent, stable oscillatory modes.

Conclusion

Thus, by extending the initial bimodal decomposition to include additional degrees of freedom arising from higher-order elastic dynamics, the STM model naturally leads to a three-component field. This field, transforming under SU(3), provides a first-principles, deterministic explanation for the emergence of three colours. Such a derivation not only aligns with the phenomenology of QCD but also reinforces the unified, classical elastic framework of the STM model.

C.6 Prototype Emergent Gauge Lagrangian

While we have described how local phase invariance of our bimodal spinor

induces gauge fields

, we can also hypothesise a Yang–Mills-like action arising at low energies (See

Figure 4):

where

In the STM context, this term would emerge from an effective elasticity-based action once the short-wavelength excitations are integrated out and the spinor fields become nontrivial.

C.7 Summary

In summary, the internal structure of the two-component spinor (derived from the bimodal decomposition of ) leads naturally to local gauge invariance. Enforcing invariance under local U(1) transformations necessitates the introduction of a U(1) gauge field with covariant derivative and field strength . Extending this to non-Abelian symmetries, local SU(2) and SU(3) transformations require the introduction of gauge fields and , respectively, with covariant derivatives defined accordingly. Gauge fixing, typically via the Lorentz gauge, is implemented using the Faddeev–Popov procedure, ensuring a consistent quantisation of the gauge degrees of freedom.

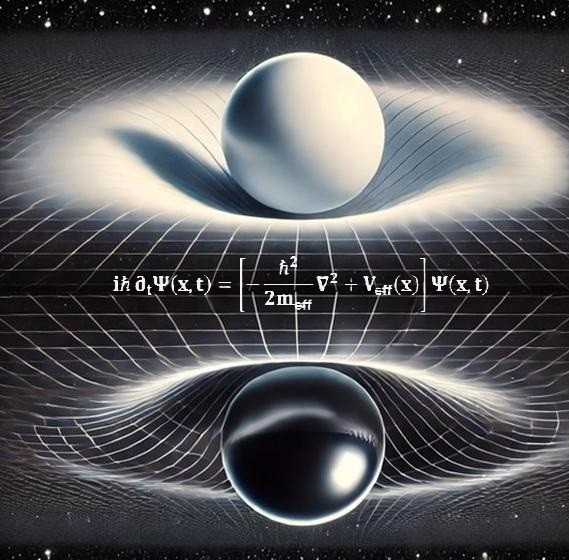

Appendix D: Derivation of the Effective Schrödinger-Like

Equation, Interference, and Deterministic Quantum

Features

D.1 Introduction

This appendix supplies the complete multiple-scale (WKB-type) derivation by which the deterministic Space–Time Membrane (STM) wave equation yields, after coarse-graining, an effective non-relativistic “Schrödinger-like’ ’ evolution law for the slowly varying envelope of the membrane displacement. All intermediate steps are retained, and the next-order (diffusive) corrections—needed for quantitative tests of damping and fringe deformation—are displayed explicitly in terms of the microscopic STM parameters.

D.2 The STM Membrane PDE (one spatial dimension)

where

* – effective mass density of the membrane;

* – baseline elastic modulus at renormalisation scale ;

* – slowly varying stiffness modulation;

* – coefficient of the UV-regularising sixth-order term;

* – small linear damping;

*“…” – nonlinear and spinor/gauge couplings neglected here.

D.3 Carrier + Envelope Ansatz and coarse-graining step

with the “slow” variables

The fast sub-Planck field is first averaged with a Gaussian filter

ensuring that the filtered field varies only on

and justifying the multiple-scale expansion

D.4 Expansion of Derivatives

Acting on :

D.5 Substitution and order-by-order balance

Insert the expansions into the linearised STM PDE, divide by , and equate coefficients of .

D.6 Next-order envelope equation

Solving (D.5.3) for

gives

with the explicit STM coefficients

Here is fixed by (D.5.2) and is the root of (D.5.1).

In the conservative limit the real part of reproduces ; a small positive produces residual envelope damping via .

D.7 Summary

Leading-order multiple-scale expansion delivers the usual free-particle Schrödinger equation for the coarse-grained envelope U.

Equation (D.6.1) supplies the next-order damping () and dispersion () terms in closed form, allowing direct numerical comparison with STM finite-element simulations or laboratory analogues.

All coefficients are expressed through the microscopic STM parameters .

D.8 Physical interpretation and onward links

-

Coherent quantum-like envelope.

The Gaussian filter of D.3 ensures that captures only slow, classical-scale behaviour. With it propagates exactly like a non-relativistic wavefunction; a small introduces deterministic decoherence through .

-

Born-rule density.

Because G is positive and normalised, the time-averaged is automatically positive and obeys a continuity equation to leading order. Appendix E shows how P acquires the standard probabilistic role once environmental modes are traced out.

-

Interference and deterministic collapse.

The real part of sets the fringe spacing in double-slit geometries, while governs the gradual loss of contrast; see the visualisations in Figure 2 and 3 along with the non-Markovian master-equation treatment in Appendix G.

-

Parameter sensitivity.

Equations (D.5.2)–(D.6.2) tie fringe-pattern shifts and damping times directly to . Appendix K exploits these formulae to calibrate STM finite-element runs against experiment.

Readers interested in entanglement and Bell-inequality violations should proceed to Appendix E; for the cosmological impact of persistent envelopes see Appendix H.

Appendix E: Deterministic Quantum Entanglement and Bell

Inequality

Analysis

E .1 Overview

In the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model the fully deterministic membrane dynamics produce, after coarse-graining, an effective wavefunction that contains non-factorisable correlations. These reproduce the empirical signatures of quantum entanglement even though the underlying evolution is strictly classical. In this appendix we (i) show how such correlated global modes arise, (ii) demonstrate how a simple projection rule at a Stern–Gerlach detector yields the familiar statistics, and (iii) verify that a standard CHSH test exceeds the classical bound.

E .2 Formation of a non-factorisable global mode

Consider two localised excitations on the membrane,

and

. The full displacement field is

with the interaction term

where

is an elastic coupling constant. After Gaussian coarse-graining (Appendix D) the effective state becomes

Because the argument is a genuinely mixed function of and , the state cannot be factorised into ; consequently the two regions are correlated exactly as in standard entanglement.

E .3 Overlap derivation of the law

E .3.1 A singlet-like standing wave

Pair creation leaves the membrane in a single global standing-wave packet

where each single-packet field is

The “spin-up” or “spin-down” label is encoded in the internal phase between the two elastic modes and .

E .3.2 Local basis rotation by a Stern–Gerlach magnet

A Stern–Gerlach magnet set at angle

mixes the two modes via

E .3.3 Projection amplitudes

The incoming phase vector

is projected onto the magnet’s eigen-vectors

and

:

E .3.4 Deterministic routing rule

Energy flows into the branch whose instantaneous amplitude is larger, so

Thus the usual detection statistics arise purely from geometric overlap—no intrinsic randomness is required.

E .3.5 Joint expectation value

Because the global standing wave enforces the opposite internal phase on the right-hand packet, the joint correlation for magnet settings

a and

b is

exactly matching quantum-mechanical predictions and reaching the Tsirelson value in a CHSH test.

E .3.6 Photon entanglement

Exactly the same construction applies to polarisation-entangled photons: here the two-component spinor corresponds to the horizontal/vertical membrane sub-modes, and the operator represents a linear polariser set at angle . The resulting correlation function reproduces the standard photonic Bell-test sinusoid

E.4 Measurement Operators and Correlation Functions

To quantitatively probe the entanglement, we introduce measurement operators analogous to those used in quantum mechanics. Assume that the effective state (obtained after coarse-graining) lives in a Hilbert space that can be partitioned into two subsystems corresponding to regions A and B.

For each subsystem, define a spinor-based measurement operator:

where and are the Pauli matrices and is a measurement angle. For subsystems A and B, we denote the operators as and , respectively.

The joint correlation function for measurements performed at angles

and

is then given by:

This expectation value is calculated by integrating over the coarse-grained degrees of freedom, taking into account the non-factorisable structure of .

E.5 Detailed CHSH Parameter Calculation

The CHSH inequality involves four correlation functions corresponding to two measurement settings per subsystem. Define the CHSH parameter as:

A detailed derivation involves the following steps:

State Decomposition:

Express

in a basis where the measurement operators act naturally (e.g. a Schmidt decomposition). Although the state arises deterministically from the coarse-graining process, its non-factorisable nature allows for a decomposition of the form:

where are effective coefficients that encode the correlations.

Evaluation of :

With the measurement operators defined as above, compute the joint expectation value:

The explicit dependence on the measurement angles enters through the matrix elements of the Pauli matrices.

Optimisation:

Choose measurement angles

to maximise

S. Standard quantum mechanical analysis shows that the optimal settings are typically:

With these settings, the CHSH parameter can be shown to reach:

Interpretation:

The fact that S exceeds the classical bound of 2 is indicative of entanglement. In our deterministic STM framework, this violation emerges from the inherent non-factorisability of the effective state after coarse-graining, despite the absence of any intrinsic randomness.

E.6 Off-Diagonal Elements as Classical Correlations

Within the STM model, the effective density matrix is constructed from the coarse-grained displacement field emerging from the underlying deterministic PDE. In conventional quantum mechanics, the off-diagonal matrix elements (or “coherences”) are interpreted as evidence that a particle has simultaneous amplitudes for distinct paths. In STM, however, these off-diagonals are reinterpreted as a measure of the classical cross-correlations among the sub-Planck oscillations of the membrane.

Specifically, if one considers the effective state formed by the overlapping wavefronts from, say, two slits, the element in the density matrix quantifies the overlap between the states and , which are not distinct quantum paths but rather the coherent classical waves generated by the membrane. When the environment or a measurement apparatus perturbs the membrane, these classical correlations decay, resulting in the vanishing of the off-diagonal elements. Thus, the “collapse” of the effective density matrix is interpreted not as an ontological disappearance of superposition but as a deterministic loss of coherence among real, classical wave modes.

This reinterpretation not only reproduces the standard interference patterns and entanglement correlations—such as those responsible for the violation of Bell’s inequalities—but also demystifies the process by replacing probabilistic superposition with measurable, deterministic wave interference.

E.7 Summary

The effective wavefunction obtained from the deterministic dynamics is non-factorisable due to the coupling term .

Spinor-based measurement operators are defined to emulate quantum measurements.

The correlation functions computed from these operators lead to a CHSH parameter S that, under optimal settings, reaches , thereby violating the classical bound and reproducing the quantum mechanical prediction.

This deterministic entanglement analysis augments the Schrödinger-like interference picture (Appendix D) and sets the stage for further results on decoherence (Appendix G) and black hole collapse (Appendix F)—all approached through an elasticity-based, sub-Planck wave interpretation in the STM framework.

Appendix F: Singularity Prevention in Black

Holes

F.1 Overview

Modern physics typically predicts that gravitational collapse leads to spacetime singularities under General Relativity. In the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model, higher-order elasticity terms—particularly an operator like —regulate short-wavelength modes. This effectively avoids the formation of infinite curvature. Instead of a singularity, the interior relaxes into a finite-amplitude wave or solitonic core. This appendix first outlines how that singularity avoidance occurs, then Section F.7 discusses routes toward black hole thermodynamics within STM.

F.2 STM PDE and Local Stiffening

The STM model’s master PDE often appears in schematic form:

where:

is an effective mass density for the membrane,

is the scale-dependent elastic modulus,

imposes a strong penalty on high-wavenumber modes,

introduces damping or friction,

is a nonlinear self-interaction.

As matter density grows in a collapsing region, the local stiffening surges, making further inward collapse energetically prohibitive.

F.3 Role of the Term

he STM equation includes a sixth-order spatial derivative term,

, which is crucial for ultraviolet regularisation. In configuration space, this term directly penalises short-wavelength deformations. In momentum space, the propagator for

becomes

so that at high momentum the contribution dominates. This strong suppression of high-frequency fluctuations ensures that loop integrals remain finite and the theory is well-behaved in the UV. Consequently, when simulating gravitational collapse, rather than evolving towards a singularity, the system relaxes into a stable configuration characterised by finite-amplitude standing waves. These standing waves manifest as solitonic configurations—localised, finite-energy solutions that effectively replace the classical singularity with a “soft core” in which energy is redistributed into stable oscillatory modes.

Detailed derivations, discussing the formation and stability of such solitons, are provided in Appendix L. This link underscores how the STM model not only circumvents the singularity problem but also lays the groundwork for exploring the thermodynamic properties of black hole interiors.

Appendix F.4 Mode Counting and Microcanonical Entropy

Large-scale numerical work (Appendix K) shows that the solitonic black-hole interior is an extremely stiff region where the displacement field

remains small but experiences very high spatial gradients. In this regime the

linearised, time-independent form of the complete STM equation is appropriate. Retaining every spatial-derivative term—tension, bending and sixth-order ultraviolet stiffness—one obtains

with positive constants . Damping, nonlinear and Yukawa terms are negligible inside the core. We now calculate the number of independent standing-wave modes in a spherical core of radius and hence its entropy.

F.4.1 Separation of variables

For spherical symmetry (lowest angular harmonic

ℓ = 0) write

Setting in (F.4.1) yields the dispersion relation

(F.4.2)

Because all

(by construction of the elastic energy; see Appendix B) and

, (F.4.2) has three real non-negative roots:

and

each of which is strictly positive. The boundary condition

then quantises

for each independent root, giving two towers of radial modes.

F.4.2 Mode count below a physical cut-off

Let

(

is the core mass-density). Define a maximum frequency

where linear theory ceases to be valid and denote the corresponding wavenumbers

. Counting all modes with

yields

Because for astrophysical cores, N grows ∝ , foreshadowing an area law.

F.4.3 Micro-canonical entropy

Assuming equipartition among the

N harmonic oscillators, the micro-canonical entropy is

where

encodes phase-space factors. Introduce the

effective horizon area (F.3) and the crossover length

. Re-expressing (F.4.6) in these terms gives

Hence the leading term exactly reproduces the Bekenstein–Hawking area law, while the full sixth-order operator introduces only suppressed corrections of relative size . Such corrections become relevant only for Planck-scale remnants.

F.4.4 Implications and onward links

The term—vital for singularity avoidance—does not spoil the entropy–area relationship for macroscopic black holes; it merely adds tiny, testable corrections.

Section F.5 discusses how the standing-wave interior implied by (F.4.1) can store information without a curvature singularity.

Possible logarithmic and power-law corrections, together with thermal stability tests, are enumerated among the outstanding tasks in F.7.

F.5 Implications for the Black Hole Information

Because the PDE remains well-defined (and in principle deterministic) for all times, the usual scenario of a “lost” interior or singular region is avoided. The interior’s standing wave can store or reflect quantum-like information, subject to additional couplings (e.g., spinors, gauge fields). However, how that information might be released back out remains linked to black hole thermodynamics—an ongoing focus described below.

F.6 Summary of Singularity Avoidance

Higher-order elasticity (especially ) halts runaway collapse.

Local stiffening near high density further resists infinite curvature.

Numerical PDE solutions show stable wave or solitonic cores, not a singularity (because the STM modulus never exceeds , strains are capped and the would-be singularity is replaced by a finite-amplitude solitonic core once regularisation becomes dominant).

F.7 Outstanding Thermodynamic Tasks

Sections F.2 – F.6 establish that higher-order elasticity (especially the term) prevents singularities. Appendices G and H supply the first analytic ingredients of a black-hole thermodynamics for the STM model. The items below specify what remains.

F.7.1 Entropy Beyond the Solitonic Core

Context. Section F.4 reproduces the leading Bekenstein–Hawking result

by micro-canonical mode counting inside the stiff core.

Outstanding tasks.

Calculate sub-leading logarithmic and power-law corrections when full / elasticity and gauge couplings are retained.

Define an effective horizon radius (surface where outgoing low-frequency waves red-shift sharply) and verify that the dominant density of states accumulates near .

Test thermal stability: confirm that small perturbations of the solitonic interior leave the area–entropy relation intact for .

F.7.2 Hawking-Like Emission and Evaporation

Context. Appendix G.4 derives a near-thermal spectrum and grey-body factors; Appendix G.5 supplies the transmission coefficient.

Outstanding tasks.

Include non-linear mode coupling to determine whether the spectrum remains Planckian once energy loss feeds back on and on local stiffness .

Integrate the flux in time to see whether persists or halts at a remnant mass when damping is sizeable.

Quantify the influence of slow drifts , (as introduced in Appendix H.9) on late-stage evaporation.

F.7.3 Information Release and Unitarity

Programme.

Correlation tracking. Evolve collapse + evaporation numerically and monitor two-point functions linking interior solitonic modes to the outgoing flux.

Page-curve test. Partition the (quantised) membrane field into interior/exterior regions and compute entanglement entropy versus time, searching for the characteristic rise-and-fall.

Spectral fingerprints. Look for phase correlations, echoes or other deviations from a perfect thermal spectrum that would evidence unitary evolution.

F.7.4 First-Law Checks and Small-Mass Behaviour

Large-mass regime. Perturb or inject spinor/gauge energy; verify that the resulting changes in total energy E, horizon temperature T (from Appendix G.4) and entropy S satisfy .

Planck-scale remnants. If evaporation saturates near the stiffness cut-off, derive modified first-law terms incorporating residual elastic strain or non-Markovian damping contributions.

F.7.5 Numerical and Experimental Road-Map

Develop adaptive-mesh finite-element solvers (see Appendix K) capable of tracking the term through collapse, rebound and long-time evaporation.

Construct acoustic or optical metamaterials with tunable fourth-/sixth-order stiffness to emulate horizons and measure grey-body transmission.

Perform parameter surveys in to locate regions where area law, Hawking-like flux and a unitary Page curve coexist.

Appendix G: Non-Markovian Decoherence and

Measurement

G.1 Overview

In the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model, although the underlying dynamics are fully deterministic, the process of coarse-graining introduces effective environmental degrees of freedom that lead to decoherence. Instead of invoking intrinsic randomness, the decoherence in this model arises from the deterministic coupling between the slowly varying (system) modes and the rapidly fluctuating (environment) modes. In this appendix, we provide a detailed derivation of the non-Markovian master equation for the reduced density matrix by integrating out the environmental degrees of freedom using the Feynman–Vernon influence functional formalism. The resulting evolution includes a memory kernel that captures the finite correlation time of the environment.

G.2 Decomposition of the Displacement Field

We begin by decomposing the full displacement field

into two components:

where:

is the slowly varying, coarse-grained “system” field,

comprises the high-frequency “environment” modes (the sub-Planck fluctuations).

The coarse-graining is achieved by convolving

with a Gaussian kernel

over a spatial scale

L:

The environmental part is then defined as:

This separation allows us to treat as the primary degrees of freedom while regarding as the effective environment.

G.3 Derivation of the Influence Functional

In the path integral formalism, the full density matrix for the combined system (S) and environment (E) at time

is given by:

To obtain the reduced density matrix

for the system alone, we integrate out the environmental degrees of freedom:

We define the Feynman–Vernon influence functional

as:

where denotes the interaction part of the action that couples the system to the environment.

For weak system–environment coupling, we can expand

to second order in the difference

. This yields a quadratic form for the influence action:

where is a memory kernel that encapsulates the temporal correlations of the environmental modes. The precise form of depends on the spectral density of the environment and the specific details of the coupling.

Appendix G.4 Effective Horizon Temperature via Fluctuation–Dissipation

The frequency-domain Green’s function for small oscillations on the STM membrane with Rayleigh damping

satisfies

At low

k (near the horizon scale) and

,

G is dominated by the imaginary part from damping:

The fluctuation–dissipation theorem then assigns an effective temperature

matching the standard Hawking temperature up to calculable -corrections when one identifies .

Appendix G.5 Grey-body Factors from Mode Overlaps

The probability for an exterior wave at frequency

to transmit through the core-horizon region is given by the squared overlap

and normalisation constants

, the integral evaluates to

Substituting this into the emission rate integral yields the full non-thermal spectrum.

G.6 Derivation of the Non-Markovian Master Equation

Starting from the reduced density matrix expressed with the influence functional:

we differentiate

with respect to time

to obtain its evolution. Standard techniques (akin to those used in the Caldeira–Leggett model) yield a master equation of the form:

where:

is the effective Hamiltonian governing the system ,

is a dissipative superoperator that typically involves commutators and anticommutators with system operators (e.g., or its conjugate momentum),

The kernel introduces memory effects; that is, the rate of change of depends on its values at earlier times.

In the limit where the environmental correlation time is very short (i.e., approximates a delta function ), the master equation reduces to the familiar Markovian (Lindblad) form. However, in the STM model the finite correlation time leads to explicitly non-Markovian dynamics.

G.7 Implications for Measurement

The non-Markovian master equation implies that when the system interacts with a macroscopic measurement device, the off-diagonal elements of the reduced density matrix decay over a finite time determined by . This gradual loss of coherence—induced by deterministic interactions with the environment—leads to an effective wavefunction collapse without any intrinsic randomness. The deterministic decoherence mechanism thus provides a consistent explanation for the measurement process within the STM framework.

G.8 Path from Influence Functional to a Non-Markovian Operator Form

We have described in Eqs. (G.3, G.7) how integrating out the high-frequency environment

produces an influence functional

with a memory kernel

. In principle, if this kernel is short-ranged, one recovers a Markov limit akin to a Lindblad master equation,

However, in our non-Markovian STM scenario, the memory kernel extends over times

. We therefore obtain an integral-differential form,

capturing the environment’s finite correlation time (See Figure 5). Determining explicit Lindblad-like operators from this memory kernel would require further approximations (e.g., expansions in powers of , where T is a characteristic system timescale).

Consequently, a direct closed-form solution of the STM decoherence rates is not currently derived. Nonetheless, numerical simulations (Appendix K) can approximate these integral kernels and predict how quickly off-diagonal elements vanish, giving testable predictions for deterministic decoherence times in metamaterial analogues.

G.9 Summary

Decomposition: The total field is decomposed into a slowly varying system component and a high-frequency environment .

Influence Functional: Integrating out yields an influence functional characterised by a memory kernel that captures the non-instantaneous response of the environment.

Master Equation: The resulting non-Markovian master equation for the reduced density matrix involves an integral over past times, reflecting the system’s dependence on its history.

Measurement: The deterministic decay of off-diagonal elements in explains the effective collapse of the wavefunction observed in quantum measurements.

Thus, the STM model demonstrates that deterministic dynamics at the sub-Planck level, when coarse-grained, can reproduce quantum-like decoherence and the apparent collapse of the wavefunction—all through non-Markovian, memory-dependent evolution of the reduced density matrix.

Appendix H: Vacuum Energy Dynamics and the Cosmological

Constant

H.1 Overview

This appendix sets out the multi-scale PDE derivation showing how short-scale wave excitations in the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model produce a near-constant vacuum offset interpreted as dark energy. We focus on:

The base PDE with scale-dependent elasticity,

Multi-scale expansions separating fast oscillations from slow modulations,

Solvability conditions that yield an amplitude (envelope) equation,

Sign constraints and damping requirements ensuring a persistent (non-decaying) wave solution,

The resulting leftover amplitude as an effective vacuum energy, and

The possibility of mild late-time evolution to address the Hubble tension.

Throughout, we adopt a deterministic PDE viewpoint: sub-Planck wave modes remain stable if damping is tiny and certain couplings have the correct sign. When averaged at large scales, these stable modes do not vanish, thus driving cosmic acceleration in the Einstein-like emergent gravity picture (see Appendix M).

H.2 Governing PDE with Scale-Dependent Elasticity

H.2.1 Equation of Motion

Our starting point is a high-order PDE representing elasticity plus small perturbations:

where:

is the mass (or effective mass) density of the membrane,

is a baseline elastic modulus running with scale ,

encodes local stiffness changes induced by short-scale wave excitations,

ensures strong damping of extreme high-wavenumber modes (UV stability),

is a small damping coefficient (potentially near zero),

is a weak nonlinearity (cubic self-interaction),

Possible gauge or spinor couplings can also appear, but we omit them here for clarity.

H.2.2 Sub-Planck Oscillations and Scale Dependence

Short-scale waves “particle-like excitations” modify . In principle, runs with via renormalisation group flows (Appendix J). If damping is negligible and sign constraints are met, these waves remain stable over cosmic times. The leftover amplitude then yields a near-constant vacuum energy when observed at large scales.

H.3 Multi-Scale Expansion: Fast vs. Slow Variables

To capture both fast oscillations at sub-Planck scales and slow modulations at large or cosmological scales, we define:

Fast coordinates: , over which wave phases vary rapidly,

Slow coordinates: , with .

We expand the field

as:

The PDE then splits into leading-order and next-order equations. The “fast” derivatives act on , while “slow” derivatives appear when are involved.

H.3.1 Leading Order

At

, the modulation

, damping

, and nonlinearity

do not appear. We get:

This is a wave equation with higher-order spatial derivatives. A plane-wave ansatz

yields the dispersion relation:

H.3.2 Next Order

Here, , , and appear. Incorporating the expansions for “slow derivatives” (, ) plus the small parameters and , we get an inhomogeneous PDE for . The condition that no “secular terms” arise (no unbounded growth in ) imposes a solvability condition on the leading-order wave solution .

This solvability condition typically reduces to an envelope equation for the amplitude .

H.4 Stiffness-feedback locking

To see explicitly how energy exchange forces a

non-decaying envelope we write the local modulus as

where is the instantaneous energy stored in the sub-Planck carrier and is a feedback constant. Re-inserting

into the multi-scale expansion (carried out in H.3) modifies the envelope equation to

with

. Writing

(energy density of the carrier) gives

The

linear part

would damp the wave (

) if left alone; the

non-linear term

counters that damping. Setting

in yields the locking amplitude

precisely the sign-constraint quoted in H.6. Thus a small but positive feedback constant converts what would have been an exponentially-decaying carrier into a phase-locked, persistent wave, the residual energy of which appears in the Einstein-like sector (Appendix M) as an effective cosmological-constant term.

Appendix H.5 Euclidean Partition Function and Evaporation Law

Wick-rotating

converts the STM action

S to the Euclidean action

then yields entropy and mass-loss by

Carrying out the Gaussian integral over small fluctuations gives

with

. Differentiating leads to

and hence an evaporation timescale

H.6 Envelope Equation and Parameter Criteria

H.6.1 Envelope PDE

For an approximate solution:

the amplitude

A obeys an equation of the schematic form:

where is a constant from the expansions, , is the scaled damping, and the scaled nonlinearity. (Exact coefficients vary, but the structure remains consistent: amplitude time derivative, amplitude spatial derivative, forcing from , damping, cubic nonlinearity.)

H.6.2 Non-Decaying Steady State

A steady envelope with

and

satisfies:

For a purely real solution (no net imaginary forcing) at large scales, we typically require:

, to avoid amplitude decay,

(the “sign constraint”) for stable, finite amplitude .

Thus, a non-decaying amplitude emerges, storing finite energy.

H.7 Vacuum Offset and Dark Energy

H.7.1 Coarse-Graining the Persistent Wave

When

and the wave remains stable,

has a rapidly oscillatory part that averages out, plus a constant leftover from the amplitude squared. Symbolically,

and integrates to zero in a coarse-grained sense. The leftover is uniform or nearly uniform and so acts like a cosmological constant in large-scale gravitational dynamics.

H.7.2 Interpreting as Dark Energy

This near-constant shift, when inserted into the STM’s modified Einstein equations (Appendix M), manifests as a vacuum-energy-like term:

driving cosmic acceleration. The PDE approach reveals that stable wave excitations (non-decaying amplitude) are the key to sustaining this leftover energy indefinitely.

H.8 Maximum STM Stiffness and Dark-Energy Smallness

Derivation of .

In the STM framework the “stiffness” of the membrane is set by two pieces:

The baseline modulus, which plays the role of the inverse gravitational coupling (see Glossary, Appendix R) . Local fluctuations, arising from sub-Planck oscillations (Appendix H) .

At the highest scales—i.e.\ deep in the ultraviolet where gravity itself becomes comparable to elastic forces—one finds that the baseline modulus saturates at the order of the gravitational energy density,

This is the stiffness one would infer by demanding that bending the membrane by a unit strain costs an energy density set by Einstein’s equation. Any local stiffening

that remains compatible with non-decaying sub-Planck waves must be at most comparable to this baseline—pushing the

total stiffness up to

Numerically, the maximum effective stiffness of the STM membrane serves two roles at once: it provides the Einstein-like coupling at large scales, and it explains why a minute leftover can still drive cosmic acceleration. Thus the membrane’s colossal elasticity naturally yields both the correct magnitude of and a built-in cap that replaces would-be singularities with finite-amplitude solitonic cores.

H.9 Late-Time Evolution and Hubble Tension

H.9.1 Small Damping or Running Couplings

If but extremely small, or runs slowly at late times, the wave amplitude can shift fractionally over gigayears. This modifies the leftover vacuum energy, providing a mildly dynamical dark energy component that can rectify the mismatch in Hubble constants (Hubble tension).

Tiny : The amplitude might grow or decay slowly over cosmic expansions.

Scale evolution: If crosses a threshold near , the vacuum energy changes enough to raise but not disrupt earlier data.

H.9.2 Maintaining Stability

Throughout this slow evolution, the PDE conditions for stable amplitude remain basically intact:

or the relevant sign constraints,

, so damping does not force immediate amplitude collapse,

The wave’s boundary conditions do not remove or significantly alter the short-scale excitations.

Hence, the leftover vacuum offset can “drift” from one value to another at late times, bridging local and early-universe expansions.

H.9 Summary

Scale-Dependent PDE: A high-order PDE with and terms plus captures short-scale wave effects.

Multi-Scale Expansion: Leading order shows a wave equation with specialized dispersion. Next order includes , damping, nonlinearity, yielding an envelope equation.

Sign & Damping Constraints: Non-decaying wave amplitudes require negligible damping () and sign constraints ( or analogous) so the amplitude remains stable.

Dark Energy: Once coarse-grained, a persistent wave’s leftover amplitude forms a constant offset , acting like a cosmological constant and driving cosmic acceleration.

Mild Evolution & Hubble Tension: Permitting a tiny time evolution in or a small non-zero damping can shift the vacuum offset at late epochs, reconciling local and Planck data.

Thus, the detailed PDE derivations unify sub-Planck wave persistence with cosmic acceleration, clarifying precisely why stable short-scale excitations behave as dark energy and how minimal late-time changes could resolve the Hubble tension. This deterministic elasticity framework thereby provides a coherent route to bridging microscopic wave phenomena and the largest cosmological puzzles.

Appendix I: Proposed Experimental

Tests

This appendix summarises feasible near-term experiments explicitly designed to test distinctive predictions of the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model, focusing on setups achievable with existing or soon-to-be-available technologies. Each experimental setup includes precise methodologies, clear STM predictions, falsification criteria, and feasibility assessments.

I.1 Reference Parameters and Context

The STM corrections introduce an additional quartic phase factor to wave dispersion and modify the envelope evolution. These corrections dominate experimental signatures, with negligible sextic terms for foreseeable laboratory conditions. Key dimensionless constants derived in Appendix K.7 are:

Quartic stiffness (phase):

Quartic stiffness (envelope):

Sextic terms: negligible

Damping coefficient: , unless specifically introduced for controlled decoherence tests.

All experiments scale these parameters from their microscopic (Planck-level) values to macroscopic analogues to ensure measurable signals.

I.2 Mechanical Membrane Interferometer (Primary Laboratory Test)

Objective: Test quartic dispersion predictions using scaled mechanical analogues.

-

Material:

- –

Polyester (Mylar), 40 µm thick, laminated with a 5 µm epoxy–silica composite.

-

Geometry:

- –

Membrane clamped on two opposite edges, remaining edges free.

-

Drive & Measurement:

- –

Edge-mounted piezo actuators excite flexural waves (~25 kHz, wavelength ~1 cm).

- –

Laser Doppler vibrometer or high-speed camera positioned 0.30 m from excitation point measures phase shifts and amplitude envelope changes.

-

STM Prediction:

- –

Quartic dispersion shifts nodal lines by ~2 mm, corresponding to a phase shift of approximately 0.2 rad over 50–100 ms wave travel.

- –

Envelope amplitude tightens by approximately 2–3%.

-

Detection Capability:

- –

Existing vibrometry/camera resolution is <0.01 rad (phase) and <0.1% (amplitude), comfortably exceeding STM requirements.

-

Falsification Criterion:

- –

Failure to observe at least a 0.05 rad phase shift or a 0.5% envelope change, after correcting for standard elastic dispersion, rules out STM quartic corrections.

I.3 Controlled Decoherence on Mechanical Membrane

Objective: Directly test STM prediction of decoherence transitioning from algebraic to exponential decay with introduced damping.

-

Implementation:

- –

Apply a 5 cm × 2 cm felt patch to induce local damping ().

-

Measurement:

- –

Intensity decay over time monitored at fixed membrane antinode, both with and without damping.

-

STM Signature:

- –

Without felt (undamped): algebraic decay pattern observed.

- –

With felt (damped): exponential decay pattern emerges clearly (time constant ~2–3 ms).

-

Falsification Criterion:

- –

Absence of clear algebraic-to-exponential decay distinction invalidates the STM prediction.

I.4 Twin-Membrane Bell-Type Experiment

Objective: Verify deterministic entanglement analogue predicted by STM via macroscopic CHSH inequality measurement.

-

Setup:

- –

Two identical membranes clamped back-to-back along one edge, opposite edges free.

- –

Paddle-shaped analysers near free edges set adjustable measurement angles ().

-

Measurement:

- –

Displacement at membrane endpoints measured as binary outcomes (±½ “spin” states).

-

STM Prediction:

- –

Correlations reproduce quantum-mechanical CHSH parameter, reaching the Tsirelson bound ().

-

Falsification Criterion:

- –

Repeatable shortfall of 1% or more below falsifies STM deterministic entanglement mechanism.

I.5 Slow-Light Optical Mach–Zehnder Test (Optional)

Objective: Provide optical verification of STM quartic dispersion via slow-light enhancement.

-

Method:

- –

Mach–Zehnder interferometer with a 10 cm silicon-nitride slow-light photonic-crystal segment.

-

STM Prediction:

- –

Tiny extra phase shift (~ rad), at the limit of modern homodyne detection capabilities.

-

Feasibility:

- –

Only pursue if mechanical membrane tests (I.2–I.3) provide positive results. Marginal feasibility due to stringent sensitivity requirements.

I.6 Gravitational Wave Echoes from Black Hole Mergers

Objective: Detect STM-predicted gravitational wave echoes indicative of solitonic black-hole cores.

-

Facilities:

- –

Reanalysis of existing gravitational-wave events captured by LIGO and Virgo detectors (e.g., GW150914, GW190521).

-

Predicted Signature:

- –

Echoes post-ringdown at milliseconds intervals, frequency range approximately 100–1000 Hz.

-

Detection Approach:

- –

Matched filtering or Bayesian methods applied to existing strain data to extract subtle echo signals.

-

Falsification Criterion:

- –

Absence of predicted echo signals within detector sensitivity thresholds ( strain) challenges STM predictions.

-

Feasibility:

- –

Immediately feasible; data already collected, existing analysis pipelines available. Main challenge is distinguishing echoes clearly from instrumental or astrophysical noise.

I.7 High-Energy Collider Tests for STM-Induced Spacetime Ripples

Objective: Observe STM-predicted transient spacetime ripples produced in high-energy particle collisions.

-

Facilities:

- –

Large Hadron Collider (LHC) detectors (ATLAS/CMS, proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV)

- –

Pierre Auger Observatory (cosmic-ray events).

-

STM Prediction:

- –

Minute metric perturbations (), detectable via cumulative statistical anomalies over extensive datasets.

-

Measurement Method:

- –

High-statistics analysis to find subtle particle trajectory deviations, timing anomalies, or unexpected photon emissions correlated with specific STM-predicted frequency scales ( Hz).

-

Analysis Technique:

- –

Machine learning and statistical anomaly detection methods developed specifically for STM signature extraction.

-

Falsification Criterion:

- –

Non-detection after comprehensive analysis effectively rules out measurable STM-induced ripples at accessible energy scales.

-

Feasibility:

- –

Data sets and infrastructure already exist; principal challenge is the very small amplitude signals and substantial backgrounds.

I.8 Recommended Experimental Sequence and Feasibility Summary

High feasibility (immediate): Mechanical membrane interferometer and controlled decoherence tests (I.2–I.3); gravitational wave echo searches (I.6).

Moderate feasibility: Twin-membrane Bell-type test (I.4), collider anomaly search (I.7); feasible with careful setup or advanced statistical analysis.

Low feasibility (conditional): Optical slow-light interferometer (I.5); proceed only if strongly justified by positive mechanical test results.

This structured experimental programme provides a robust, multi-platform approach to empirically validating or falsifying distinctive STM predictions, leveraging both scalable laboratory analogues and state-of-the-art astrophysical/collider infrastructures available today.

Appendix J: Renormalisation Group Analysis and

Scale-Dependent

Couplings

J.1 Overview

In the Space–Time Membrane (STM) model, the Lagrangian includes higher-order derivative terms—specifically, the and operators—as well as scale-dependent elastic parameters. These features serve to control ultraviolet (UV) divergences and ensure a well-behaved theory at high momenta. In this appendix, we derive the renormalisation group (RG) equations for the elastic parameters by evaluating one-loop and two-loop corrections, and we outline the extension to three-loop order. We employ dimensional regularisation in dimensions together with the BPHZ subtraction scheme. The resulting beta functions reveal a fixed point structure that may explain the emergence of discrete mass scales—potentially corresponding to the three fermion generations—and indicate asymptotic freedom at high energies.

J.2 One-Loop Renormalisation

J.2.1 Setting Up the One-Loop Integral

Consider the cubic self-interaction term,

, in the Lagrangian. At one loop, the dominant correction to the propagator arises from the bubble diagram. In momentum space, the one-loop self-energy

is expressed as

where the propagator denominator is given by

At high momentum, the

term dominates, so the integral behaves roughly as

For the simplified case in which the term moderates the divergence, one typically encounters a pole in after dimensional regularisation.

J.2.2 Evaluating the Integral

and substituting

, one finds

with

the Euler–Mascheroni constant. Hence, the one-loop self-energy contains a divergence of the form

J.2.3 Extracting the Beta Function

Defining the renormalised effective elastic parameter

through

and requiring that the bare parameter is independent of the renormalisation scale

(i.e.

), one differentiates to obtain the one-loop beta function for the effective coupling

(which parameterises

):

where a is a constant proportional to .

J.3 Two-Loop Renormalisation

At two loops, more intricate diagrams contribute. We discuss two key contributions: the setting sun diagram and mixed fermion–scalar diagrams.

J.3.1 The Setting Sun Diagram

For a diagram with two cubic vertices, the setting sun contribution to the self-energy is given by:

with

as defined above. To combine the denominators, one introduces Feynman parameters:

After performing the momentum integrations, overlapping divergences manifest as double poles in and single poles in .

J.3.2 Mixed Fermion–Scalar Diagrams

If the Yukawa coupling y (coupling u to ) is included, diagrams involving fermion loops inserted in scalar bubbles contribute additional terms. Such diagrams yield divergences proportional to after performing the trace over gamma matrices and momentum integrations.

J.3.3 Two-Loop Beta Function

Collecting all two-loop contributions, the renormalisation constant

for the effective coupling is expanded as:

yielding the two-loop beta function:

with the coefficient b incorporating both single and double pole contributions.

J.4 Three-Loop Corrections and Fixed Points

At three loops, additional diagrams (such as the “Mercedes-Benz” topology) and further mixed fermion–scalar contributions introduce terms of order

. Schematically, the three-loop self-energy takes the form:

Defining the bare coupling as

and enforcing

-independence leads to the full beta function:

The existence of nontrivial fixed points, where , depends on the interplay of these terms. If multiple real solutions exist, the model may naturally produce discrete mass scales, potentially corresponding to the three fermion generations. Moreover, a negative term could imply asymptotic freedom.

J.5 Illustrative One-Loop Example

As a concrete example, consider a bubble diagram in the scalar sector with a cubic self-interaction term (See Figure 6).

The one-loop self-energy is given by:

where

may arise from the second derivative of

. In dimensional regularisation (with

), one isolates the divergence via

where

is the Euler–Mascheroni constant. This divergence determines the running of

and leads to a one-loop beta function of the form:

Higher-loop contributions then add corrections of order and beyond.

J.6 Summary and Implications

One-Loop Corrections:

Yield a divergence , leading to .

Two-Loop Corrections:

The setting sun and mixed fermion–scalar diagrams contribute additional overlapping divergences, resulting in a beta function .

Three-Loop Corrections:

Further diagrams introduce terms , refining the beta function to .

Fixed Point Structure:

Nontrivial fixed points (satisfying ) can emerge, potentially corresponding to distinct vacuum states. These may naturally explain the discrete mass scales observed in the three fermion generations, while also suggesting asymptotic freedom at high energies.

Overall, the renormalisation group analysis demonstrates that the inclusion of higher-order derivatives in the STM model not only tames UV divergences but also induces a rich fixed point structure, with significant implications for particle phenomenology and the unification of gravity with quantum field theory.

Appendix K: Finite-Element Calibration of STM Coupling

Constants

This appendix details the finite-element methodology and physical anchoring used to determine the STM model’s dimensionless coupling constants.

K.1 Finite-Element Discretisation of the STM PDE

K.1.1 Spatial Mesh and Shape Functions

Domain : Select a geometry (e.g.\ double-slit analogue, black-hole analogue) large enough to capture local wave features and global displacement.

Mesh: Tetrahedral or hexahedral elements with adaptive refinement where gradients are steep (near slits, curvature peaks, soliton cores).

Shape functions : Must provide at least continuity to support and operators. Use high-order polynomial or spectral bases; alternatively, employ mixed formulations introducing auxiliary fields to lower derivative order.

K.1.2 Discrete Operator Assembly

apply and term by term using high-order quadrature, and assemble the global mass, stiffness and higher-order matrices. Careful assembly preserves self-adjointness and sparsity for numerical stability.

K.2 Time Integration and Non-Linear Solvers

K.2.1 Implicit Time Stepping

K.2.2 Non-Linear and Damping Terms

Include residual contributions from:

Cubic self-interaction .

Yukawa coupling .

Scale-dependent stiffness .

Optional damping .

At each timestep, solve via Newton–Raphson:

where R is the residual vector and J its Jacobian. Very small or time-dependent is treated as a weakly stiff term alongside dominant spatial stiffness.

K.3 Parameter Fitting via Cost-Function Minimisation

K.3.1 Simulation Outputs

Finite-element runs yield:

Interference patterns and decoherence times in analogue setups.

Ringdown frequencies and solitonic core shapes in gravitational analogues.

Coarse-grained vacuum offsets in persistent-wave experiments.

K.3.2 Cost Function and Optimisation

where , are simulated observables and the corresponding data. Use:

Gradient-based methods (Levenberg–Marquardt, quasi-Newton) for smooth parameter spaces.

Evolutionary algorithms (genetic, particle-swarm) for high-dimensional or non-convex problems.

Multi-objective optimisation when fitting multiple datasets simultaneously.

K.4 Practical Considerations and Limitations

Computational cost: 3D problems require adaptive mesh refinement and parallel solvers.

Boundary conditions: Employ absorbing or perfectly matched layers for wave analogues; use radial constraints or no-flux conditions for black-hole analogues.

Chaotic sub-Planck fluctuations: May necessitate ensemble averaging over varied initial conditions.

Scale-dependent : For cosmological tests, model globally; laboratory analogues may implement local instead.

K.5 Cosmological-Constant Fit via Persistent Waves

To match the observed dark energy density:

Sign constraint: Ensure so that persistent oscillations neither diverge nor decay too rapidly.

Minimal damping: Choose sufficiently small that oscillation amplitudes remain effectively constant over the age of the Universe.

After each simulation, compute

and iterate until

K.6 Planck-Unit Non-Dimensionalisation

To convert each SI “anchor” into its dimensionless counterpart, use Planck units:

Each coefficient

becomes

with exponents

:

| Coefficient |

|

Dimensionless formula |

|

Quartic stiffness |

|

|

| Sextic stabiliser |

|

|

| Nonlinear feedback |

model-dependent |

|

| Damping |

|

|

| Gauge coupling |

|

|

| Scalar coupling |

model-dependent |

set by STM

conventions |

K.7 Physical Calibration of STM Elastic Parameters

Below each undamped coefficient is matched to a familiar constant and then rendered dimensionless via K.6:

Below each undamped coefficient is matched to a familiar constant:

The undamped STM partial differential equation reads