Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

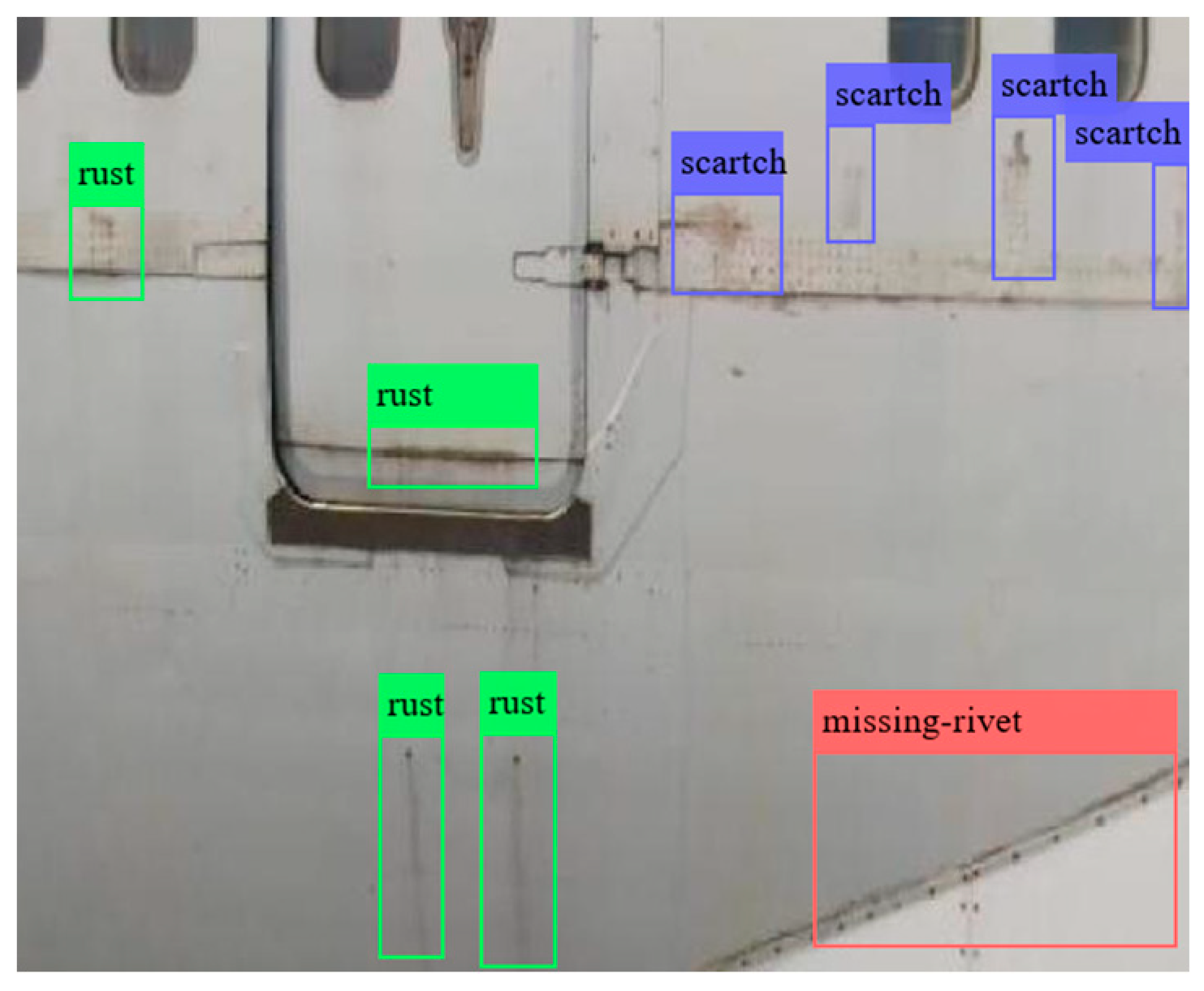

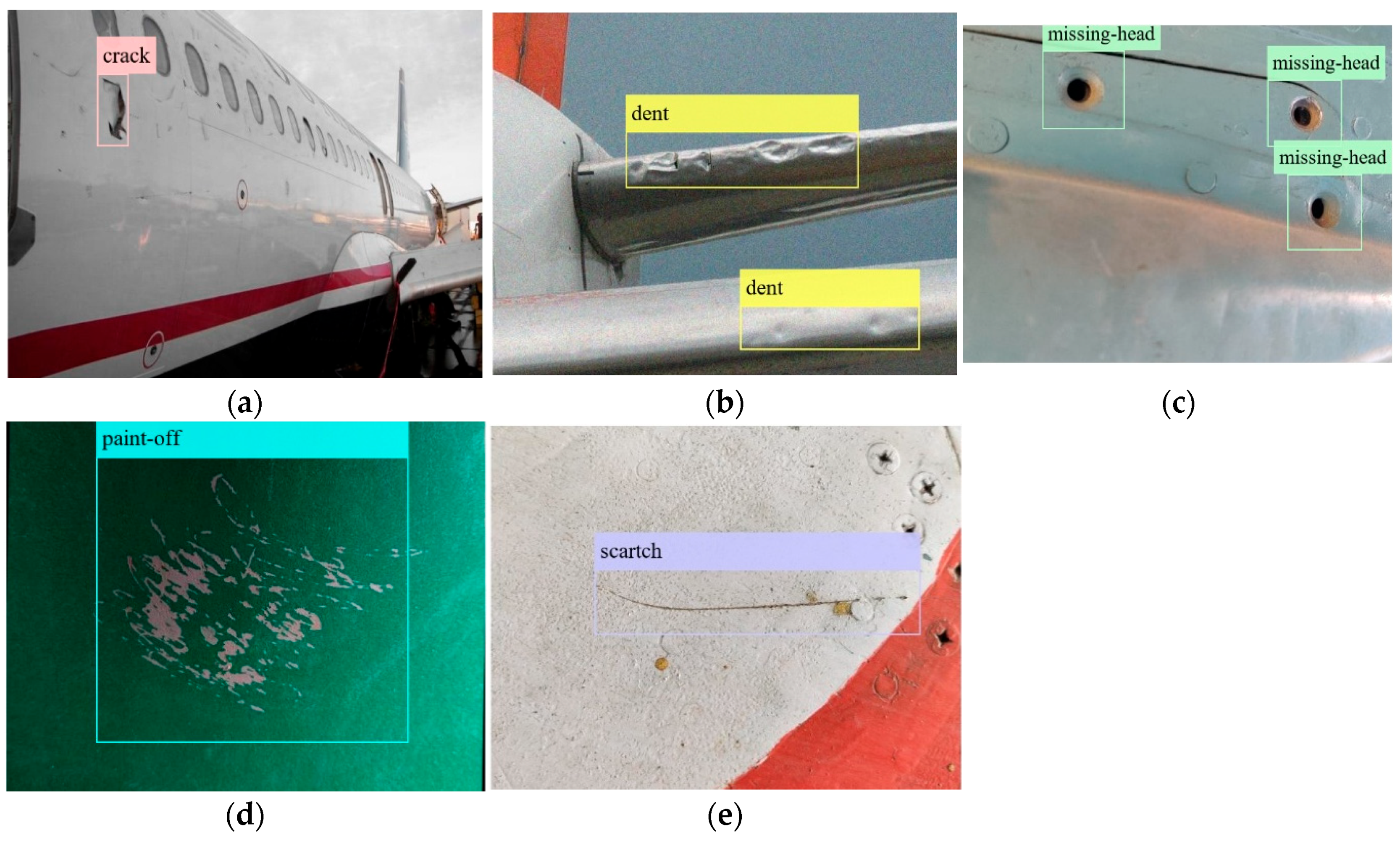

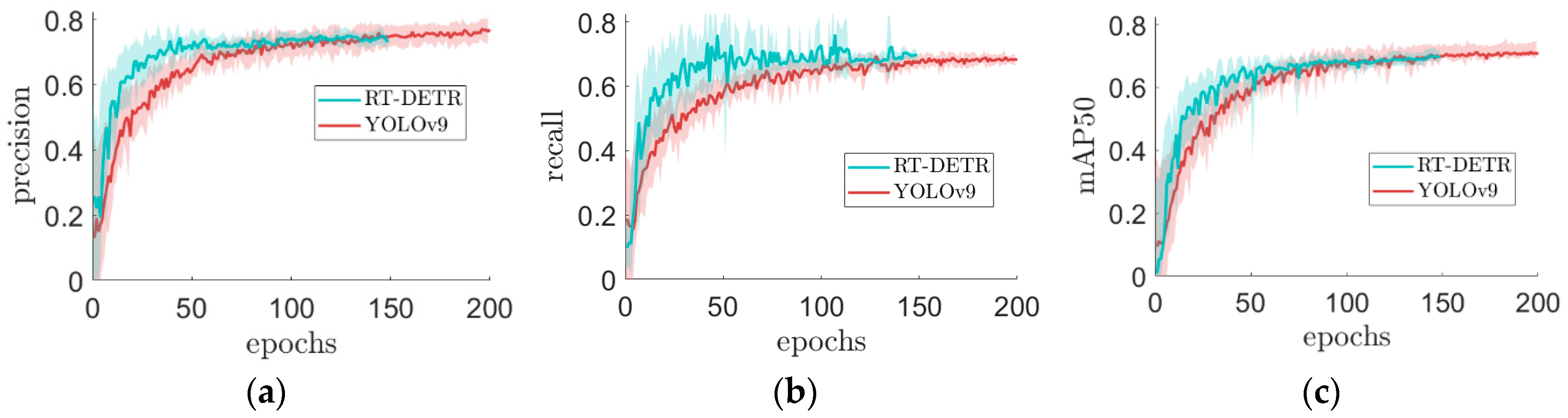

Aircraft skin surface defect detection is critical for aviation safety but is currently mostly reliant on manual or visual inspections. Recent advancements in computer vision offer opportunities for automation. This paper reviews the current state of computer vision algorithms and their application in aircraft defect detection, synthesizing insights from academic research (21 publications) and industry projects (18 initiatives). Beyond a detailed review, we experimentally evaluate the accuracy and feasibility of existing low-cost, easily deployable hardware (drone) and software solutions (computer vision algorithms). Specifically, real-world data were collected from an abandoned aircraft with visible defects using a drone to capture video footage, which was then processed with state-of-the-art computer vision models — YOLOv9 and RT-DETR. Both models achieved mAP50 scores of 0.70–0.75, with YOLOv9 demonstrating slightly better accuracy and inference speed, while RT-DETR exhibited faster training convergence. Additionally, a comparison between YOLOv5 and YOLOv9 revealed a 10% improvement in mAP50, highlighting the rapid advancements in computer vision in recent years. Lastly, we identify and discuss various alternative hardware solutions for data collection — in addition to drones, these include robotic platforms, climbing robots, and smart hangars — and discuss key challenges for their deployment, such as regulatory constraints, human-robot integration, and weather resilience. The fundamental contribution of this paper is to underscore the potential of computer vision for aircraft skin defect detection while emphasizing that further research is still required to address existing limitations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Thorough review of existing hardware and software solutions for aircraft defect detection: The investigation highlights significant growth in academic research on computer vision for aircraft defect detection. Notably, all academic references are dated from 2019 onward, with over half of the publications appearing in 2024. On the industry side, numerous projects have been publicly disclosed since 2014, with half launched during or after the COVID-19 pandemic. These projects span various regions and industry sectors, including airlines (e.g., EasyJet, Air France, KLM, Singapore Airlines, Delta Airlines, Lufthansa), aircraft manufacturers (e.g., Airbus, Boeing), and organizations in the field of aerospace, robotics and artificial intelligence (e.g., Rolls-Royce, MainBlades, Donecle, SR Technics, ST Engineering, Jet Aviation, HACARUS) as well as research institutes (A*STAR).

- 2.

- Collection of a new dataset of aircraft defects using a drone from an abandoned aircraft: Using an affordable and commercially available Parrot Bebop Quadcopter Drone (14-megapixel full HD 1080p, 180° field of view), we demonstrate that current readily available technology can achieve accurate aircraft defect detection. We validate this hypothesis by investigating a preserved Boeing 747 with defects located in Korat, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand. The collected dataset has been made publicly available (see here [12]) to support testing and benchmarking of future algorithms for aircraft defect detection. To the best of our knowledge, although several other studies have collected defect data from drone imagery [13,14,15,16,17,18], their datasets remain inaccessible due to confidentiality. Existing publicly available datasets primarily focus on defect-specific images (e.g., [19]), often emphasizing close-up views of defects rather than encompassing the entire aircraft (with and without defects) or accounting for variations in image quality caused by distance and angle. The lack of publicly available data is a frequently cited challenge in research papers on this topic [18,20].

- 3.

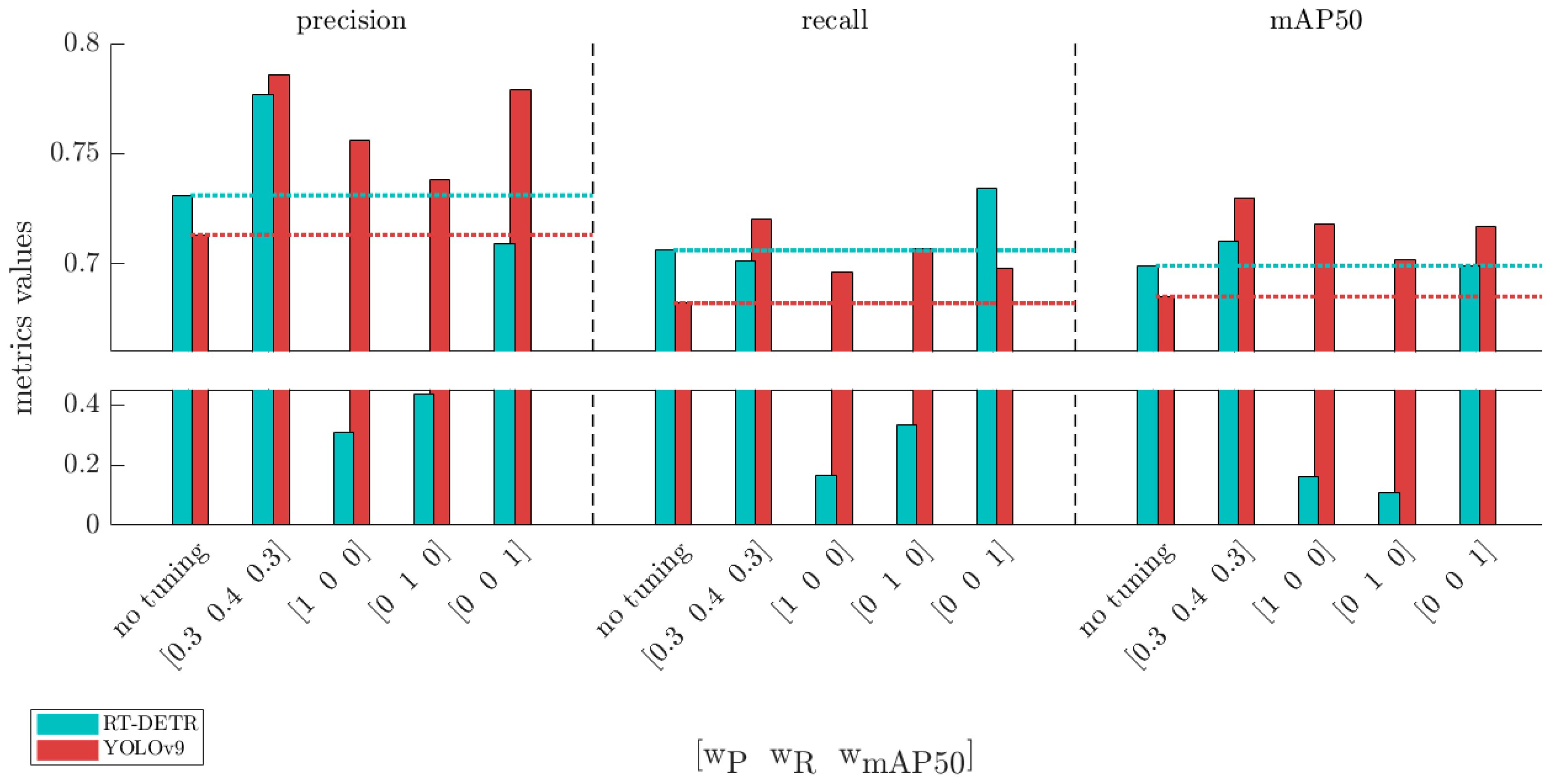

- Evaluation and Comparison of Leading Computer Vision Algorithms for Aircraft Defect Detection: This work tests and compares YOLOv9 and RT-DETR, two of the most accurate computer vision models (refer to [9]). Our implementation of these algorithms for aircraft defect detection contributes in two major ways: (i) it offers a benchmark analysis highlighting the relative strengths of these models. The results show comparable overall performance, with RT-DETR slightly outperforming YOLOv9 prior to hyperparameter tuning, whereas YOLOv9 achieves superior results post-tuning; (ii) we demonstrate the practicality of leveraging modern computer vision algorithms for real-world aircraft defect detection, achieving moderate accuracy even without extensive tuning: mAP50 scores range from 0.699 for RT-DETR to 0.685 for YOLOv9. Additionally, a comparison with the YOLOv5 Extra-Large (YOLOv5x) model [21], developed in 2020, reveals a 10% improvement in mAP50 with YOLOv9, emphasizing the rapid advancements in computer vision.

- 4.

- Hyperparameter tuning using Bayesian optimization: To avoid a myopic, single implementation of these algorithms, we applied hyperparameter tuning and analyzed its impact on performance metrics, particularly precision, recall, and mAP50. Our results show that tuning improves accuracy by 1.6% for RT-DETR and 6.6% for YOLOv9 across two datasets analysed — our drone-collected dataset [12] and a publicly available dataset [19]. We demonstrate that performance can be tailored to specific priorities by emphasizing different metrics during tuning. To encourage further research and facilitate refinement of the presented models, we have made our codes publicly available in [22].

- 5.

- Discussion of limitations and challenges in implementing computer vision for aircraft defect detection: Our findings highlight the potential of computer vision to enhance defect detection, particularly given the rapid evolution of computer vision algorithms. However, discussions with industry experts reveal significant challenges that remain. These include: (i) regulatory constraints that vary across countries, hindering the development of standardized solutions; (ii) the need for seamless human-robot collaboration, as automation is intended to complement rather than replace human inspectors; (iii) the necessity of achieving exceptionally high accuracy levels to meet stringent safety standards. Current mAP50 levels of 0.70–0.75 may still be insufficient due to safety reasons. These findings emphasize the promise of this technology while motivating continued advancements to overcome these challenges.

2. Research and Industry Survey

3. Data Collection

4. Methodology

4.1. RT-DETR

4.2. YOLOv9

4.3. Performance Metrics

4.4. Hyperparameter Tuning

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Performance Comparison

5.2. Accuracy Metrics Emphases During Tuning

6. Discussion

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs):

Advantages:

- Capable of reaching difficult areas, such as the upper fuselage and tail sections, without the need for scaffolding or lifts;

- Able to conduct inspections quickly, making them particularly useful for pre/post-flight inspections;

- Swarm of drones can make routine inspections inside hangars even faster;

- As suggested by our review of literature, drones have been already widely tested by both academia and industry;

- Relatively inexpensive. As shown through the experiment in this paper even inexpensive drones and cameras can already provide good levels of accuracy;

- Easily transferable between inspections. Can be deployed across multiple aprons/stands.

Limitations:

- UAV operations are subject to strict aviation regulations, which may limit their deployment in certain areas of the airport. Additionally, regulatory differences across airports pose challenges for developing standardized solutions;

- Drones may only be permitted for use inside hangars, reducing their utility for pre/post-flight inspections. Solutions like tethers attached to drones could address this, but may limit their range and effectiveness;

- May obstruct other maintenance activities, and therefore human-drone coordination requires planning;

- Battery life and payload capacity can restrict flight duration and the types of sensors that can be equipped;

- Planning 3D trajectories for drones around aircraft surfaces can be challenging, particularly when coordinating a swarm of drones.

Smart Hangars with High-Resolution Cameras:

Advantages:

- Less constrained by regulations as the system operates within a controlled environment and does not interfere with other operations;

- Easily integrates with human-led maintenance activities without obstructing ongoing tasks;

- Once installed, these systems provide reliable, consistent coverage without needing repositioning, and maintenance costs remain relatively low after the initial setup.

Limitations:

- Can only be used inside hangars limiting its use at pre/post flight inspections;

- Fixed cameras may struggle to capture certain parts of the aircraft, especially at specific angles. Additionally, the quality of images may be reduced compared to drones or robots that capture close-up visuals;

- The system is not transferable, requiring airports to dedicate specific hangars equipped with this technology and plan aircraft inspection schedules accordingly;

- Installation and integration of high-resolution camera systems involve substantial upfront investment.

Mobile Robot Platforms:

Advantages:

- Relatively inexpensive and easy to implement, as they can be adapted from technologies already used in other industries (e.g., infrastructure and industrial inspections, as reviewed in [85]);

- Easily transferable between inspections, can be deployed across multiple aprons/stands;

- Can accommodate a more diverse range of equipment (different cameras, sensors, etc) due to their greater payload capacity (not as constrained as drones or climbing robots).

Limitations:

- Cannot access elevated areas like the top of the fuselage or tail sections without additional equipment, such as extendable cameras;

- May obstruct other maintenance activities, requiring careful planning and coordination between human workers and the robotic platform, which can be more challenging compared to drones;

- Inspections using ground-based robots may take longer than drones or fixed cameras to cover the entire aircraft.

Climbing Robots:

Advantages:

- Capable of traversing complex geometries, these robots can inspect detailed areas of the aircraft, including the fuselage, wings, and tail sections, without the need for scaffolding or lifts;

- Since they adhere to the aircraft’s surface rather than flying freely like drones or moving on the ground like traditional robot platforms, climbing robots may face fewer regulatory constraints during operation;

- Their operation is less likely to obstruct other maintenance activities, especially during routine inspections;

- Easily transferable between inspection. Can be deployed across multiple aprons/stands.

Limitations:

- While effective for detailed examinations, these robots may require more time to inspect the entire aircraft surface, making them more suitable for scheduled maintenance rather than quick pre/post-flight checks;

- Adhesion mechanisms and technologies tailored for aircraft inspection can make climbing robots more expensive compared to other inspection tools;

- Regulatory Framework: The regulatory aspect is paramount, particularly given that aviation is a global industry. Automation of defect detection operations requires international coordination and recognition to ensure consistency across countries. Standardizing regulations would enable the development of solutions that are globally applicable rather than tailored to specific regional contexts. While the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) provides overarching safety management frameworks, such as Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) [86], these currently lack detailed guidance and regulations specific to automated aircraft defect detection.

- Human-Robot Interaction: The interaction between humans and robotic systems in defect detection remains undefined and requires research. The role of humans in the defect detection process, once these solutions are implemented, needs clarification. Should their role be passive, focused on analyzing feedback from these systems, or active, complementing the robots/drones detection search? Additionally, these systems may obstruct other critical operations, particularly during aircraft turnaround processes. Some work has already begun to explore this topic [87].

- Path Planning: Robust path planning mechanisms are needed to address two key objectives: minimizing interference with other operations and ensuring complete aircraft coverage with high-quality images within the limited time available. Research is already underway to tackle this challenge [88,89,90], but further advancements are crucial.

- Weather Resilience: Weather conditions may significantly impact automated defect detection, especially during pre- and post-flight inspections. Ensuring that automated solutions remain resilient and functional under adverse weather conditions is essential to prevent disruptions. This resilience must be investigated and integrated into future systems to ensure reliability across a wide range of environmental scenarios.

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAA, “Advisory Circular: Visual Inspection for Aircraft.” U.S. Department of Transportation, 1997.

- IMRBPB, “Clarification of Glossary Definitions for General Visual (GVI), Detailed (DET), and Special Detailed (SDI) Inspections.” 2011.

- R. Saltoğlu, N. Humaira, and G. İnalhan, “Aircraft Scheduled Airframe Maintenance and Downtime Integrated Cost Model,” Advances in Operations Research, vol. 2016, no. 1, p. 2576825, 2016.

- Y. Liu, J. Dong, Y. Li, X. Gong, and J. Wang, “A UAV-Based Aircraft Surface Defect Inspection System via External Constraints and Deep Learning,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 71, pp. 1–15, 2022.

- J. P. Sprong, X. Jiang, and H. Polinder, “Deployment of Prognostics to Optimize Aircraft Maintenance – A Literature Review,” Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 26–37, May 2020.

- U. Papa and S. Ponte, “Preliminary Design of An Unmanned Aircraft System for Aircraft General Visual Inspection,” Electronics, vol. 7, no. 12, 2018.

- Le Clainche, S.; Ferrer, E.; Gibson, S.; Cross, E.; Parente, A.; Vinuesa, R. Improving Aircraft Performance Using Machine Learning: A Review. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 108354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. A. Rodríguez, C. Lozano Tafur, P. F. Melo Daza, J. A. Villalba Vidales, and J. C. Daza Rincón, “Inspection of Aircrafts and Airports Using UAS: A Review,” Results in Engineering, vol. 22, p. 102330, 2024.

- COCO, “Object Detection on COCO test-dev.” https://paperswithcode.com/sota/object-detection-on-coco, 2023.

- C.-Y. Wang, I.-H. Yeh, and H.-Y. M. Liao, “YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13616, 2024.

- Y. Zhao et al., “DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08069, 2024.

- SUTD, “Aircraft AI Dataset,” Roboflow Universe. https://universe.roboflow.com/sutd-4mhea/aircraft-ai-dataset ; Roboflow, 2024.

- J. Miranda, J. Veith, S. Larnier, A. Herbulot, and M. Devy, “Machine Learning Approaches for Defect Classification on Aircraft Fuselage Images Aquired by An UAV,” in International conference on quality control by artificial vision, 2019, p. 1117208.

- T. Malekzadeh, M. Abdollahzadeh, H. Nejati, and N.-M. Cheung, “Aircraft Fuselage Defect Detection Using Deep Neural Networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.09213, 2020.

- D. Meng, W. Boer, X. Juan, A. N. Kasule, and Z. Hongfu, “Visual Inspection of Aircraft Skin: Automated Pixel-Level Defect Detection by Instance Segmentation,” Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 254–264, 2022.

- L. Connolly, J. Garland, D. O’Gorman, and E. F. Tobin, “Deep-Learning-Based Defect Detection for Light Aircraft With Unmanned Aircraft Systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 83876–83886, 2024.

- B. Huang, Y. Ding, G. Liu, G. Tian, and S. Wang, “ASD-YOLO: An Aircraft Surface Defects Detection Method Using Deformable Convolution and Attention Mechanism,” Measurement, vol. 238, p. 115300, 2024.

- Plastropoulos, K. Bardis, G. Yazigi, N. P. Avdelidis, and M. Droznika, “Aircraft Skin Machine Learning-Based Defect Detection and Size Estimation in Visual Inspections,” Technologies, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 158, 2024.

- Hangar, “Innovation Hangar v2 Dataset,” Roboflow Universe. https://universe.roboflow.com/innovation-hangar/innovation-hangar-v2/dataset/1 ; Roboflow, 2023.

- W. Zhang, J. Liu, Z. Yan, M. Zhao, X. Fu, and H. Zhu, “FC-YOLO: an aircraft skin defect detection algorithm based on multi-scale collaborative feature fusion,” Measurement Science and Technology, vol. 35, no. 11, p. 115405, 2024.

- G. Jocher, “Ultralytics YOLOv5.” https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5, 2020.

- Kurniawan, “Aircraft-Skin-Defect-Detection-YOLOv9-Vs.-RT-DETR.” https://github.com/cparyoto/Aircraft-Skin-Defect-Detection-YOLOv9-Vs.-RT-DETR, 2024.

- Z. Deyin, W. Penghui, T. Mingwei, C. Conghan, W. Li, and H. Wenxuan, “Investigation of Aircraft Surface Defects Detection Based on YOLO Neural Network,” in 2020 7th international conference on information science and control engineering (ICISCE), IEEE, 2020, pp. 781–785.

- Y. Li, Z. Han, H. Xu, L. Liu, X. Li, and K. Zhang, “YOLOv3-Lite: A Lightweight Crack Detection Network for Aircraft Structure Based on Depthwise Separable Convolutions,” Applied Sciences, vol. 9, no. 18, p. 3781, 2019.

- J. D. Maunder et al., “AI-based General Visual Inspection of Aircrafts Based on YOLOv5,” in 2023 IEEE canadian conference on electrical and computer engineering (CCECE), 2023, pp. 55–59.

- S. Pasupuleti, R. K, and V. M. Pattisapu, “Optimization of YOLOv8 for Defect Detection and Inspection in Aircraft Surface Maintenance using Enhanced Hyper Parameter Tuning,” in 2024 international conference on electrical electronics and computing technologies (ICEECT), 2024, pp. 1–6.

- H. Wang, L. Fu, and L. Wang, “Detection algorithm of aircraft skin defects based on improved YOLOv8n,” Signal, Image and Video Processing, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 3877–3891, 2024.

- Q. Ren and D. Wang, “Aircraft Surface Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8,” in 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE), IEEE, 2024, pp. 603–606.

- J. Zhao et al., “Biological Visual Attention Convolutional Neural Network for Aircraft Skin Defect Detection,” Measurement: Sensors, vol. 31, p. 100974, 2024.

- L. Chen, L. Zou, C. Fan, and Y. Liu, “Feature weighting network for aircraft engine defect detection,” International Journal of Wavelets, Multiresolution and Information Processing, vol. 18, no. 3, p. 2050012, 2020.

- Y. Abdulrahman, M. M. Eltoum, A. Ayyad, B. Moyo, and Y. Zweiri, “Aero-engine blade defect detection: A systematic review of deep learning models,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 53048–53061, 2023.

- Upadhyay, J. Li, S. King, and S. Addepalli, “A deep-learning-based approach for aircraft engine defect detection,” Machines, vol. 11, no. 2, p. 192, 2023.

- Y. Qu, C. Wang, Y. Xiao, J. Yu, X. Chen, and Y. Kong, “Optimization algorithm for surface defect detection of aircraft engine components based on YOLOv5,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 20, p. 11344, 2023.

- Niccolai, D. Caputo, L. Chieco, F. Grimaccia, and M. Mussetta, “Machine Learning-Based Detection Technique for NDT in Industrial Manufacturing,” Mathematics, vol. 9, no. 11, 2021.

- Shafi et al., “Deep learning-based real time defect detection for optimization of aircraft manufacturing and control performance,” Drones, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 31, 2023.

- Rosell et al., “Machine Learning-Based System to Automate Visual Inspection in Aerospace Engine Manufacturing,” in 2023 IEEE 28th international conference on emerging technologies and factory automation (ETFA), 2023, pp. 1–8.

- N. Prakash, D. Nieberl, M. Mayer, and A. Schuster, “Learning Defects from Aircraft NDT Data,” NDT & E International, vol. 138, p. 102885, 2023.

- J. Zhuge, W. Zhang, X. Zhan, K. Wang, Y. Wang, and J. Wu, “Image matching method based on improved harris algorithm for aircraft residual ice detection,” in 2017 4th international conference on information, cybernetics and computational social systems (ICCSS), IEEE, 2017, pp. 273–278.

- R. Wen, Y. Yao, Z. Li, Q. Liu, Y. Wang, and Y. Chen, “LESM-YOLO: An improved aircraft ducts defect detection model,” Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 24, no. 13, p. 4331, 2024.

- Jovančević, I. Viana, J.-J. Orteu, T. Sentenac, and S. Larnier, “Matching CAD model and image features for robot navigation and inspection of an aircraft,” in International conference on pattern recognition applications and methods, SCITEPRESS, 2016, pp. 359–366.

- J. R. Leiva, T. Villemot, G. Dangoumeau, M.-A. Bauda, and S. Larnier, “Automatic visual detection and verification of exterior aircraft elements,” in 2017 IEEE international workshop of electronics, control, measurement, signals and their application to mechatronics (ECMSM), IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–5.

- Ramalingam et al., “Visual Inspection of the Aircraft Surface Using a Teleoperated Reconfigurable Climbing Robot and Enhanced Deep Learning Technique,” International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, vol. 2019, no. 1, p. 5137139, 2019.

- Soufiane, D. Anıl, A. Ridwan, A. Reyhan, and S. Joselito, “Towards automated aircraft maintenance inspection. A use case of detecting aircraft dents using mask r-cnn,” A use case of detecting aircraft dents using Mask R-CNN, 2020.

- Doğru, S. Bouarfa, R. Arizar, and R. Aydoğan, “Using Convolutional Neural Networks to Automate Aircraft Maintenance Visual Inspection,” Aerospace, vol. 7, no. 12, p. 171, 2020.

- S. Merola, “Digital Optics and Machine Learning Algorithms for Aircraft Maintenance,” Materials research proceedings, 2024.

- N. Suvittawat and N. A. Ribeiro, “Aircraft Surface Defect Inspection System Using AI with UAVs,” in International conference on research in air transportation (ICRAT), 2024, pp. 1–4.

- H. Li, C. Wang, and Y. Liu, “Aircraft Skin Defect Detection Based on Fourier GAN for Data Augmentation ,” in 2024 international conference on advanced robotics and mechatronics (ICARM), IEEE, 2024, pp. 449–454.

- X. Zhang, J. Zhang, J. Chen, R. Guo, and J. Wu, “A Semisupervised Aircraft Fuselage Defect Detection Network With Dynamic Attention and Class-Aware Adaptive Pseudolabel Assignment,” IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 7, 2024.

- Air-Cobot Project, “Air-Cobot: Collaborative Mobile Robot for Aircraft Inspection.” Collaborative Project by Akka Technologies, Airbus Group,; Partners; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air-Cobot, 2013.

- P. Davies, “EasyJet Reveals Drone Inspection and 3D Printing Plans.” https://travelweekly.co.uk/articles/54445/easyjet-reveals-drone-inspection-and-3d-printing-plans; Travel Weekly, 2015.

- Donecle, “Automating Your Aircraft Inspections.” https://www.donecle.com/, 2015.

- MainBlades, “Aircraft Inspection Automation.” https://www.mainblades.com/, 2017.

- Airbus, “Airbus Launches Advanced Indoor Inspection Drone to Reduce Aircraft Inspection Times and Enhance Report Quality.” https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2018-04-airbus-launches-advanced-indoor-inspection-drone-to-reduce-aircraft, 2018.

- Rolls-Royce, “Rolls-Royce Demonstrates The Future of Engine Maintenance with Robots that can Crawl Inside Engines.” https://www.rolls-royce.com/media/press-releases/2018/17-07-2018-rr-demonstrates-the-future-%20of-engine-maintenance-with-robots.aspx, 2018.

- SR Technics, “Robots Driving Innovation at SR Technics.” https://www.srtechnics.com/news/press-releases-blog-social-media/2018/february-2018/robots-driving-innovation-at-sr-technics/, 2018.

- Ubisense, “Ubisense and MRO drone launch world’s first ‘smart hangar’ solution.” https://ubisense.com/ubisense-and-mro-drone-launch-worlds-first-smart-hangar-solution/, 2018.

- Airfrance, “In Motion AWACS: Drone Inspection.” https://www.afiklmem.com/en/robotics/drone-inspections, 2019.

- ST Engineering, “ST Engineering Receives First-ever Authorisation from CAAS to Perform Aircraft Inspection Using Drones.” https://www.stengg.com/en/newsroom/news-releases/st-engineering-receives-first-ever-authorisation-from-caas-to-perform-aircraft-inspection/, 2020.

- Kulisch, “Korean air develops drone swarm technology to inspect aircraft.” https://www.flyingmag.com/korean-air-develops-drone-swarm-technology-to-inspect-aircraft/, 2022.

- G. Aerospace, “GE aerospace service operators: Meet your ‘mini’ robot inspector companions.” https://www.geaerospace.com/news/press-releases/services/ge-aerospace-service-operators-meet-your-mini-robot-inspector-companions, 2023.

- A*STAR I^2R, “Smart Automated Aircraft Visual Inspection System (SAAVIS).” https://www.a-star.edu.sg/i2r/research/I2RTechs/research/i2r-techs-solutions/SAAVIS, 2023.

- Loi, “SIA Engineering Lifts Productivity as Latest Robots Help Inspect Aircraft Engines.” https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/sia-engineering-boosts-productivity-with-robots-inspecting-aircraft-engines-and-seat-tracks; The Straits times, May 2023.

- Jet Aviation, “AI Drone Inspections.” https://www.jetaviation.com/ai-drone-inspections/, 2023.

- Koplin, “Industry First: FAA Accepts Delta’s Plan to Use Drones for Maintenance Inspections.” https://news.delta.com/industry-first-faa-accepts-deltas-plan-use-drones-maintenance-inspections, 2024.

- Biesecker, “Boeing Expanding Effort to Autonomously Inspect Aircraft.” https://www.aviationtoday.com/2024/07/11/boeing-expanding-effort-to-autonomously-inspect-aircraft-july-28/; Aviation Today, 2024.

- Lufthansa Technik, “Aircraft Overhaul: Testing Future technologies.” https://www.lufthansa-technik.com/en/innovation-bay, 2024.

- Dwyer, J. Nelson, T. Hansen, et al., “Roboflow (Version 1.0).” https://roboflow.com, 2024.

- T.-Y. Lin et al., “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1405.0312, 2015.

- N. Carion, F. Massa, G. Synnaeve, N. Usunier, A. Kirillov, and S. Zagoruyko, “End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.12872, 2020.

- Khan et al., “A Survey of The Vision Transformers and Their CNN-Transformer Based Variants,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 2917–2970, 2023.

- Ultralytics, “Baidu’s RT-DETR: A Vision Transformer-Based Real-Time Object Detector.” https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/rtdetr/, 2024.

- J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick, and A. Farhadi, “You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.02640, 2015. U.

- Vijayakumar and S. Vairavasundaram, “YOLO-based Object Detection Models: A Review and its Applications,” Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2024.

- Wang et al., “YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14458, 2024.

- Jocher and J. Qiu, “Ultralytics YOLO11.” https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics/yolov11, 2024.

- Ultralytics, “YOLOv9: A Leap Forward in Object Detection Technology.” https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov9/, 2024.

- Ultralytics, “Performance Metrics Deep Dive.” https://docs.ultralytics.com/guides/yolo-performance-metrics/, 2024.

- P. Probst, A.-L. Boulesteix, and B. Bischl, “Tunability: Importance of Hyperparameters of Machine Learning Algorithms,” Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 20, no. 53, pp. 1–32, 2019.

- J. P. Weerts, A. Mueller, and J. Vanschoren, “Importance of Tuning Hyperparameters of Machine Learning Algorithms,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13616, 2020.

- F. Hutter, H. H. Hoos, and K. Leyton-Brown, “Sequential Model-Based Optimization for General Algorithm Configuration,” in Learning and Intelligent Optimization, C. A. Coello, Ed., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011, pp. 507–523.

- J. Snoek, H. Larochelle, and R. P. Adams, “Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, F. Pereira, C. J. Burges, L. Bottou, and K. Q. Weinberger, Eds., Curran Associates, Inc., 2012, pp. 1–9.

- Bischl, J. Richter, J. Bossek, D. Horn, J. Thomas, and M. Lang, “mlrMBO: A Modular Framework for Model-Based Optimization of Expensive Black-Box Functions,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.03373, 2018.

- T. Head, M. Kumar, H. Nahrstaedt, G. Louppe, and I. Shcherbatyi, “scikit-optimize/scikit-optimize.” https://github.com/scikit-optimize/scikit-optimize, 2020.

- National Supercomputer Center (NSCC) Singapore, “ASPIRE2A General QuickStart Guide.” https://help.nscc.sg/wp-content/uploads/ASPIRE2A-General-Quickstart-Guide.pdf, 2024.

- Lattanzi and G. Miller, “Review of robotic infrastructure inspection systems,” Journal of Infrastructure Systems, vol. 23, no. 3, p. 04017004, 2017.

- ICAO, “SARPs - standards and recommended practices.” https://www.icao.int/safety/safetymanagement/pages/sarps.aspx, 2024.

- F. Donadio, J. Frejaville, S. Larnier, and S. Vetault, “Human-robot collaboration to perform aircraft inspection in working environment,” in Proceedings of 5th international conference on machine control and guidance (MCG), 2016.

- Bircher et al., “Structural inspection path planning via iterative viewpoint resampling with application to aerial robotics,” in 2015 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2015, pp. 6423–6430.

- Y. Liu, J. Dong, Y. Li, X. Gong, and J. Wang, “A UAV-based aircraft surface defect inspection system via external constraints and deep learning,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 71, pp. 1–15, 2022.

- Y. Sun and O. Ma, “Drone-based automated exterior inspection of an aircraft using reinforcement learning technique,” in AIAA SCITECH 2023 forum, 2023, p. 0107.

| 1 | Additional inspections may be necessary if reports from pilots or sensor data indicate potential defects or anomalies during operation, or following severe events. |

| 2 | These intervals are general estimates and may vary based on factors such as pilot- or crew-reported issues, aircraft usage, age, and type. |

| 3 | B checks are typically performed every 800 to 1,500 flight hours (approximately 6 to 8 months), spanning 1 to 3 days of inspection. C checks occur every 3,000 to 6,000 flight hours (approximately 18 months to 2 years.) |

| 4 | Subsequently, [74] introduced YOLOv10, which reportedly achieves similar performance to YOLOv9 with 46% reduced latency and 25% fewer parameters. Additionally, in September 2024, [75] released YOLOv11 for public use, which improved the YOLO-series architecture and training methods for more versatile computer vision applications. |

| 5 | Description of the hyperparameters can be found in Ultralytics (2023). |

| References (Year) | Description |

|---|---|

| [42] (2019) |

Scope: Utilizing a reconfigurable climbing robot for aircraft surface defect detection. Data Source: RGB images taken by climbing robot. CV Algorithm: Enhanced SSD MobileNet. Focus: Detecting between aircraft stain and defect. |

| [13] (2019) |

Scope: Investigating defect classification on aircraft fuselage from UAV images. Data Source: Images taken using a drone. CV Algorithm: Combination of CNN and few-shot learning methods. Focus: Detecting paint defects, lightning burns, screw rashes, rivet rashes. |

| [24] (2019) |

Scope: Adapting YOLO3 for faster crack detection in aircraft structures. Data Source: Images from aviation company and industrial equipment. CV Algorithm: YOLOv3-Lite. Focus: Aircraft cracks. |

| [14] (2020) |

Scope: Developing a deep neural network (DNN) to detect aircraft defects. Data Source: Images taken using drone. CV Algorithm: AlexNet and VGG-F networks with a SURF feature extractor. Focus: Detecting fuselage defects (binary classification). |

| [43] (2020) |

Scope: Developing a Mask R-CNN to detect aircraft dents. Data Source: Images from publicly available sources and within the hangar. CV Algorithm: Mask R-CNN. Focus: Aircraft dents. |

| [44] (2020) |

Scope: Improving MASK R-CNN with augmentation techniques. Data Source: Images from publicly available sources and within the hangar. CV Algorithm: Pre-classifier in combination with MASK R-CNN. Focus: Wing images with and without aircraft dents. |

| [23] (2020) |

Scope: Applying and Comparing YOLOv3 with Faster-RCNN. Data Source: Self-collected dataset of aircraft defect images. CV Algorithm: YOLO Neural Network and Faster-RCNN. Focus: Detecting: skin crack, thread corrosion, skin peeling, skin deformation, and skin tear. |

| [15] (2022) |

Scope: Developing an improved mask scoring R-CNN. Data Source: Images taken using a drone. CV Algorithm: Mask Scoring R-CNN for instance segmentation with attention and feature fusion. Focus: Detecting paint falling and scratch. |

| [25] (2023) |

Scope: Examining the use of YOLOv5 to detect defects on aircraft surface. Data Source: Self-collected dataset of aircraft defect images. CV Algorithm: YOLOv5. Focus: Detecting: cracks, dent, missing screws, peeling, and corrosion. |

| [45] (2024) |

Scope: Exploring the use of CNNs for aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Images taken by drones and blimps. CV Algorithm: CNN. Focus: Detecting: missing rivet, corroded rivet. |

| [16] (2024) |

Scope: Exploring the use of YOLOv8 for aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Images taken using drone, phone, and camera. CV Algorithm: YOLOv8. Focus: Detecting: panel missing, rivets/screws damaged or missing. |

| [26] (2024) |

Scope: Inspecting hyperparameter tuning of YOLOv8 for aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of surface parts. CV Algorithm: YOLOv8 with MobileNet backbone and Bayesian optimization. Focus: Detecting: gap, microbridge, line collapse, bridge, rust, scratch, and dent. |

| [17] (2024) |

Scope: Proposing an improved YOLOv5-based model for aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Publicly available images and images captured using a drone. CV Algorithm: YOLO model with deformable convolution, attention mechanisms, and contextual enhancement. Focus: Detecting: crack, dent, missing rivet, peeled paint, scratch, missing caps, and lost tools. |

| [29] (2024) |

Scope: Proposing a bio-inspired CNN model for low-illumination aircraft skin defect detection. Data Source: Images taken by an airline. CV Algorithm: U-Net with residual blocks and attention mechanisms. Focus: Detecting image pixels with defects. |

| [46] (2024) |

Scope: Applying YOLOv8 to aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Images taken using a drone. CV Algorithm: YOLOv8. Focus: Detecting: rust, scratches, and missing rivets. |

| [18] (2024) |

Scope: Testing various deep learning architectures for aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Drone and handheld cameras used inside the hangar. CV Algorithm: Various CNN-based models with custom size-estimation. Focus: Detecting: dents, missing paint, screws, and scratches. |

| [20] (2024) |

Scope: Improving YOLOv7 for aircraft defect detection. Data Source: Images collected using a mobile platform camera and publicly available datasets. CV Algorithm: FC-YOLO with feature fusion strategies. Focus: Detecting: paint peel, cracks, deformation, and rivet damage. |

| [27] (2024) |

Scope: Improving YOLOv8n for detecting small aircraft defects. Data Source: Images collected using DJI OM 4 SE stabilizers paired with mobile cameras. CV Algorithm: Improved YOLOv8n with Shuffle Attention and BiFPN. Focus: Detecting: cracks, corrosion, and missing labels. |

| [47] (2024) |

Scope: Data augmentation using Fourier GAN to improve defect detection accuracy. Data Source: Drone-collected and synthetic images. CV Algorithm: Fourier GAN for data augmentation. Focus: Detecting: loose components, corrosion, and skin damage. |

| [28] (2024) |

Scope: Improving YOLOv8 for robust defect detection. Data Source: Publicly available images. CV Algorithm: YOLOv8 with CoTAttention and SPD-Conv modules. Focus: Detecting: cracks, dents, and rust. |

| [48] (2024) |

Scope: Developing DyDET, a lightweight semi-supervised aircraft defect detection framework. Data Source: Images collected using camera. CV Algorithm: DyDET with dynamic attention and adaptive pseudolabeling. Focus: Detecting: scratches, paint-peeling, rivet damage, and rust. |

| References (Year) | Description |

|---|---|

| [49] (2013) |

Scope: A French R&D project developing an autonomous wheeled robot capable of inspecting aircraft during maintenance operations. Solution Type: Robot Platform Offered Benefits: Enhances inspection reliability and repeatability; reduces inspection time and maintenance costs. |

| [50] (2015) |

Scope: EasyJet integrates drones for aircraft inspection and explores 3D printing to reduce maintenance costs and downtime. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Speeds up inspection; reduces dependency on external suppliers for parts. |

| [51] (2015) |

Scope: Automated visual inspections using autonomous drones with AI-powered software. Solution Type: swarm of drones Offered Benefits: Performs GVI, identifies lightning strikes, and provides close-up inspections more efficiently than manual processes. |

| [52] (2017) |

Scope: Mainblades offers automated drone inspections for aircraft maintenance. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Detects defects such as dents, cracks, and lightning strikes; reduces inspection time and improves consistency. |

| [53] (2018) |

Scope: Airbus uses autonomous drones equipped with high-resolution cameras to conduct visual inspections of aircraft surfaces. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Speeds up inspection (3 hours), enhances safety by reducing human exposure. |

| [54] (2018) |

Scope: Rolls-Royce demonstrated multiple robotic solutions, including SWARM robots for visual inspections, FLARE for repairs, and remote boreblending robots for maintenance tasks. Solution Type: Swarm of drones Offered Benefits: Enables inspections and repairs without removing the engine; reduces downtime and maintenance costs. |

| [55] (2018) |

Scope: Developed a robot to move on aircraft for inspection and deliver tools to difficult-to-access areas. Solution Type: Climbing Robot Offered Benefits: Tools can be delivered to engineers for improved maintenance efficiency. |

| [56] (2018) |

Scope: A collaboration between Ubisense and MRO Drone to create an automated aircraft inspection and tool management system. Solution Type: Smart Hangar Offered Benefits: Decreases Aircraft on Ground (AOG) time by up to 90%; enhances efficiency and productivity in maintenance operations. |

| [57] (2019) |

Scope: Developed automated drone inspection for exterior aircraft components on surfaces. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Reduce time and cost of aircraft maintenance. Can inspect both inside and outside of hangar. |

| [58] (2020) |

Scope: Received CAAS authorization to use drones for aircraft inspections, ensuring faster and safer processes. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Reduces inspection time; authorized for regulatory compliance. |

| [59] (2022) |

Scope: Korean Air’s development of a drone swarm system to inspect aircraft exteriors. Solution Type: Swarm of drones Offered Benefits: Reduces inspection time by up to 60%; improves safety and accuracy; minimizes aircraft downtime. |

| [60] (2023) |

Scope: GE Aerospace’s soft robotic inchworm designed for on-wing jet engine inspection and repair. Solution Type: Climbing Robot Offered Benefits: Enables minimally invasive inspections; reduces maintenance burden; provides access to hard-to-reach engine areas. |

| [61] (2023) |

Scope: A*STAR’s Smart Automated Aircraft Visual Inspection System (SAAVIS) uses robots and hybrid AI for defect detection on airframes. Solution Type: Smart Hangar Offered Benefits: Reduces inspection time and human errors; detects over 30 defect types. |

| [62] (2023) |

Scope: Employs robotic arms and AI to inspect aircraft engines and seat tracks, improving efficiency. Solution Type: Robot platform Offered Benefits: Saves over 780 man-hours annually; reduces staff fatigue and increases inspection accuracy. |

| [63] (2023) |

Scope: AI-powered drone inspections for a range of aircraft maintenance needs. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Conducts inspections for aircraft structure, paint quality, and pre-purchase evaluations. |

| [64] (2024) |

Scope: Delta is the first U.S. airline to use FAA-approved drones for maintenance inspections, improving speed and safety. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Speeds up inspection by 82%; reduces technician risk during inspections. |

| [65] (2024) |

Scope: Boeing uses small drones with AI-based damage detection software to automate exterior aircraft inspections. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Cuts inspection time by half, improves accuracy, and reduces costs. |

| [66] (2024) |

Scope: Tests drone-based inspections, 3D scanning, and exoskeletons for aircraft overhauls, aiming to streamline maintenance. Solution Type: Drones Offered Benefits: Speeds up maintenance, improves accuracy, and reduces costs. |

| no. | argument | values | no. | argument | values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | batch | 15 | hsv_h | ||

| 2 | lr0 | 16 | hsv_s | ||

| 3 | lrf | 17 | hsv_v | ||

| 4 | momentum | 18 | degrees | ||

| 5 | weight_decay | 19 | translate | ||

| 6 | warmup_epochs | 20 | scale | ||

| 7 | warmup_momentum | 21 | shear | ||

| 8 | warmup_bias_lr | 22 | perspective | ||

| 9 | box | 23 | flipud | ||

| 10 | cls | 24 | fliplr | ||

| 11 | dfl | 25 | bgr | ||

| 12 | pose | 26 | mosaic | ||

| 13 | kobj | 27 | mixup | ||

| 14 | nbs | 28 | copy_paste | ||

| 29 | erasing |

| models | before tuning | after tuning | ||||

| P | R | mAP50 | P | R | mAP50 | |

| RT-DETR | ||||||

| YOLOv9 | ||||||

| YOLOv5 | ||||||

| models | before tuning | after tuning | ||||

| P | R | mAP50 | P | R | mAP50 | |

| RT-DETR | ||||||

| YOLOv9 | ||||||

| From [19] | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).