1. Introduction

As a lightweight aircraft with no requirement for human pilots, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have the advantages of low cost, strong robustness, and commercial availability [

1]. UAVs equipped with various types of sensors have many applications, such as fire detection, weather monitoring, emergency search and rescue, logistics transmission, precision agriculture, target tracking, etc. In recent years, more and more research has focused on using UAVs equipped with high-resolution cameras to collect image data from target areas by taking photos or videos, which is called data collection tasks [

2]. Owing to their high maneuverability and high-altitude communication advantages, UAVs are increasingly being used in data collection tasks, especially in search and rescue, surveillance, and the Internet of Things [

3,

4,

5].

UAV-enabled data collection mainly focuses on the monitoring of disaster-affected areas in emergency scenarios[

6,

7]. Earthquakes or heavy rainfall often cause geological disasters such as landslides, ground subsidence, and debris flows, causing huge property losses and casualties. In order to collect information about the degree of disaster, the scope of impact, and disaster trends in the affected area, data collection can be achieved by taking image data of the affected area through UAVs. However, due to the special nature of the data collection task, the UAV needs to cover as many target areas as possible in a limited time, while it needs to minimize flight distance and energy consumption at the same time. This requires comprehensive consideration of task scheduling [

8,

9] and resource allocation [

10,

11] two issues, and make effective trade-offs. Therefore, it is necessary to plan UAV trajectories and resource allocation. Besides, in emergency scenarios, the environment is often dynamically changing. For example, the priority of ground targets in disaster-affected areas will change dynamically. During the task execution process, priority information will change through new information monitored by satellites or manual modifications by relevant personnel. Traditional optimization algorithms are often difficult to solve such problems, and reinforcement learning methods are one of the effective ways to solve such dynamic programming problems. It is of great significance and value to study the application of reinforcement learning methods in task planning for UAV data collection tasks.

The main problem that needs to be solved in the UAV data collection task is to optimize its trajectory planning and resource allocation under the condition of limited UAV battery capacity to effectively complete the task. However, (1) most of the current research on UAV data collection tasks is to optimize the UAV’s trajectory under the condition of limited UAV energy or limited working time [

12,

13], ignoring the problem of resource allocation (computing resources and communication resources) during the task process, and rarely considering the limited cache space of the UAV, as well as the UAV having certain on-board processing capabilities, which can process data both on-board and transmit data to ground processing nodes for processing; (2) Most of the existing studies focus on using optimization methods to complete the solution of trajectory planning and resource allocation under fixed target distribution [

14]. When the target distribution changes, it needs to be recalculated.

Reinforcement learning, as an algorithm based on trial-and-error learning, can adaptively optimize UAV trajectory planning and resource allocation in a dynamic environment. Evolutionary algorithms, genetic algorithms, and other optimization methods based on natural evolution and genetic mechanisms also have good adaptability and robustness, widely used in UAV data collection tasks.

To solve these issues, we proposed a novel hierarchical deep reinforcement learning based task scheduling and resource allocation method (HDRL-TSRAM) for UAV data collection applications, which achieves hierarchical modeling of UAV data collection task scenarios, fully considering the processes of UAV flight, communication, calculation, data collection, etc., and designs appropriate reward functions to improve the efficiency of UAV collection. Firstly, the scenario modeling of UAV data collection tasks is introduced, followed by a detailed introduction of the principles and frameworks of the lower-layer resource allocation algorithm and the upper-layer task scheduling algorithm. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed HDRL-TSRAM is verified through rich comparative experimental results. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose a two-layer hierarchical task scheduling and resource allocation scheme for the UAV data collection task, where the amount of the collected data, as well as UAV energy consumption, is jointly minimized by training the target allocation, trajectories, communication power, and CPU frequency of the UAV in a decentralized manner.

In the lower layer, we design the PPO based algorithm to optimize the continuous actions, where the Lin-Kernighan-Helsgaun method is utilized to obtain the optimal trajectory as the given input of the lower layer network (LLN).

In the upper layer, we leverage the DQN based algorithm to optimize the discrete actions with the assistance of the nested well-trained LLN, which gives rapid feedback on global rewards and accelerates the training process of the upper layer network.

Extensive experiments are implemented to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed two-layer HDRL-TSRAM framework, which achieves superior performance compared with several baseline methods.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section II provides the related work. Section III introduces the system model and problem formulation. Section IV presents the proposed HDRL-TSRAM framework. Simulation experiments and result analysis are demonstrated in Section V. Section VI concludes this paper.

Table 1.

The Structure of This Paper

Table 1.

The Structure of This Paper

| Section |

Content |

| 1 |

Introduction |

| 2 |

Related works |

| 3 |

System model |

| 4 |

Hierarchical DRL method |

| 5 |

Experimental results and analysis |

| 6 |

Discussion |

| 7 |

Conclusions |

2. Related Work

This section discusses the related work about UAV data collection from the perspective of two popular methods: 1) scenarios of the UAV data collection and 2) the corresponding approaches.

2.1. Scenarios of the UAV Data Collection

In the context of the Internet of Things, UAVs complete data collection by data transmission with ground sensors. The focus of current research is how to use the limited energy of UAVs to collect more data [

5]. The main research directions are data collection mode and UAV trajectory planning.

The data collection mode of UAVs includes hover mode, flight mode, and hybrid mode. Hover mode refers to the UAV hovering above the data collection point for a period of time to collect data. In [

15], the entire area is divided into several sub-regions, and the UAV collects data from sensors by hovering above these sub-regions. The advantage of the hover mode is that it can provide relatively stable data transmission, but the disadvantage is that it has relatively high energy consumption. Flight mode refers to the UAV slowing down and collecting ground sensor data while flying through the data collection point until it flies out of the communication range of the sensor. In flight mode, data can be collected while moving, and the data collection task can be completed quickly. In general, the shortest flight time is usually selected as the objective function in flight mode, to minimize the flight time of the UAV during data collection. In [

16] and [

17], the horizontal distance at which sensors can upload data to UAVs, the speed of UAVs, and the transmission power of sensors are jointly optimized. The hybrid mode combines the characteristics of both hover mode and flight mode. The UAV collects data by hovering above the data collection point, and can still collect data until it leaves the communication range of the sensor before flying to the next collection point. The energy consumption and flight time in hybrid mode are smaller than those in hover mode, but larger than those in flight mode. The hybrid mode can dynamically adjust the data collection mode according to the energy consumption of the UAV. Due to limited communication equipment and UAV batteries, Zhu [

18] proposed a hybrid hover point selection algorithm to select UAV hover points with minimum power consumption for machine type communication devices.

UAV trajectory planning refers to the calculation of the best trajectory for a UAV from its starting point to its destination under specific conditions [

19]. UAV trajectory planning has a crucial impact on the performance of data acquisition. There are various objectives for trajectory planning, such as the shortest trajectory, shortest flight time, and lowest energy consumption for the UAV [

20,

21,

22]. The high maneuverability and flexible deployment of UAVs bring challenges to trajectory planning. Additionally, given that UAVs have limited energy and radio resources, UAV trajectory planning is often combined with resource allocation to effectively optimize resource utilization [

23,

24]. Therefore, due to the large decision space, the complexity of jointly optimizing trajectory planning and resource allocation is very high.

In monitoring scenarios, UAVs complete data collection by taking photos or videos. For example, in emergency scenarios, UAVs equipped with cameras can be deployed in disaster-affected areas to take photos of the affected areas, providing valuable information for rescue decision-making [

25]. UAVs can also be dispatched to fully cover the interested area for 3D terrain reconstruction [

26] or to cover the ball and players in a football field for live streaming [

27]. The current focus of research is on minimizing energy consumption during the UAV data collection process under energy-limited conditions, with the main research direction being UAV trajectory planning.

Most current research focuses on minimizing UAV energy consumption. Jiating Qian [

26] studied the problem of deploying UAVs to fully cover the interested area for 3D terrain reconstruction, with the objective of minimizing the UAV’s energy consumption. Additionally, 3D rotation matrix methods are crucial for accurately aligning and transforming sensor data during terrain reconstruction. These methods use a 3×3 orthogonal matrix to represent the rotation of the UAV relative to a global coordinate system, ensuring that measurements from different orientations are consistently mapped onto the terrain model. This transformation not only aids in precise 3D feature alignment but also enhances the robustness of the reconstruction process in dynamic and uneven terrains. The authors [

28] investigated task security offloading and data caching optimization strategies in scenarios with multiple interfering devices. With the goal of minimizing the total energy consumption, the UAV trajectories, transmission power, task offloading scheduling strategies, and caching decisions was jointly optimized. An iterative algorithm named CDSFS which is based on the coordinate descent, successive convex approximation, and flow shop scheduling is proposed to solve the optimization problem. Other studies focus on minimizing redundant information in collected data. For example, Liang [

2] proposed an estimation method for redundant information in images, and used a polynomial approximation algorithm to plan UAV trajectories to minimize redundant information. In reference [

29], the author established a UAV swarm task scheduling optimization model after considering constraints such as target threat range, priority of reconnaissance and interference tasks, interference task time, and UAV energy consumption and modeled the anti-interference capability of the target as a threat range. Then, a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm based on distance in the solution space and a dynamic parent selection strategy (DPSNSGA-II) was proposed to solve UAV resource scheduling optimization problem. The diversity of the population is increased and the situation of falling into local optima is reduced by improving the parent individual selection strategy, mutation strategy, and elite solution retention mechanism.

2.2. Corresponding Approaches

UAV task scheduling and resource allocation algorithms can be divided into graph theory-based and optimization method-based. Among them, deep reinforcement learning-based method belongs to a type of optimization based methods.

The trajectory planning algorithms based on graph theory include Voronoi diagram algorithm, Probabilistic Roadmap (PRM) algorithm, Hilbert curve algorithm, etc. This kind of method converts the geographical space where the UAV performs the task into a graph and searches for the path between the source and destination, with the optimization objectives generally being maximum data acquisition, minimum data acquisition time, minimum energy consumption, etc. Voronoi diagram, also known as Thiessen polygons or Dirichlet tessellation, is a set of polygons formed by connecting the perpendicular bisectors of two adjacent points, where these points are obstacles [

30]. The Probabilistic Roadmap (PRM) consists of sample points and collision-free straight-line edges [

31]. The trajectory search algorithm based on PRM comprises two stages: learning and query. In the learning stage, the PRM constructs an undirected graph through sampling and collision detection. In the query stage, the PRM applies the shortest path algorithm to find the flight trajectory of the UAV. This method uses relatively few random sampling points to find a solution, and as the number of sampling points increases, the probability of finding a trajectory tends to 1. The Hilbert curve plays an important role in image processing, multi-dimensional data indexing, and other fields. It is a space-filling curve that maps from one-dimensional space to two-dimensional space [

32].

In the trajectory planning and resource allocation problems in UAV data collection missions, optimization-based algorithms include Dynamic Programming (DP), Branch and Bound (BB), and Successive Convex Approximation (SCA). These algorithms can find the optimal or sub-optimal solution to the problem. However, for some non-deterministic polynomial hard (NP-hard) problems that can be reduced to non-deterministic polynomial problems (NP) in polynomial time complexity, the time complexity is exponential, making it very difficult to solve. When the decision space is large, heuristic methods can be applied to find feasible solutions. The dynamic programming algorithm is a nonlinear optimization method proposed by Bellman. Dynamic programming transforms a multi-stage decision problem into a series of single-stage decision problems [

33]. The optimal trajectory and resource allocation decisions can be obtained through recursive iteration, with the objective function generally being to minimize the UAV data collection time or minimize the average Age of Information (AOI). In [

20], a UAV-enabled data collection system with a rotary-wing UAV and multiple ground nodes (GNs) was studied. By establishing the data collection problem as a dynamic optimization problem subject to state constraints, in which both of the decision variables and constraints are infinite-dimensional in nature, coordinating and optimizing the transmission power of GNs and the trajectory of drones, the average transmission data rate is maximized. The branch and bound algorithm is a search and iterative method [

34]. Branch and bound continuously iteratively decomposes the given problem into subproblems. The decomposition of subproblems is called branching, and the bounding of subproblems’ objective functions is called bounding. To collect data from as many sensors as possible, Samir [

35] proposed a high-complexity branch, reduction, and bounding (BRB) algorithm to find the global optimal solution for relatively small-scale scenarios. Then, they developed an effective solution algorithm based on successive convex approximation to obtain results for larger networks. They also proposed an extended algorithm that further minimizes the UAV’s flight distance when the initial and final positions of the UAV are known a priori. Extensive simulations and analysis demonstrate the superiority of the algorithm, and benchmark tests are conducted based on distance and deadline metrics for two greedy algorithms. The Successive Convex Approximation (SCA) algorithm transforms the original non-convex optimization problem into a series of convex optimization problems that can be solved effectively. SCA iteratively solves a series of convex optimization problems similar to the original problem [

36]. When the final convergence condition is satisfied, the solution can be approximated as the solution to the original problem. The objective function is generally to minimize UAV energy consumption, maximize UAV data collection volume, maximize throughput, etc. Yunxin Xu [

37] established a full-duplex UAV-assisted mobile edge computing communication system model to address potential ground eavesdropping risks in UAV-assisted computation offloading tasks.. To address the non-convex optimization problem within the model, a SCA algorithm is employed for simplification and decomposition. User scheduling, power allocation, and UAV trajectory design subproblems are solved through an alternating iteration method. In [

38], UAV trajectory control and channel assignment for UAV-based wireless networks with wireless backhauling was studied to maximize the sum rate achieved by ground users while satisfying their data demand where spectrum reuse and co-channel interference management are considered. To tackle the underlying non-convex mixed-integer nonlinear optimization problem, the alternating optimization approach is uesd to optimize the channel assignment and UAV trajectory control until convergence. Moreover, an efficient heuristic algorithm was proposed to solve the channel assignment sub-problem and SCA is used to solve the non-convex UAV trajectory control sub-problem.

Reinforcement learning methods fit the mapping between states and optimal actions through interaction with the environment, ultimately obtaining the optimal policy and maximizing cumulative rewards. The training data for supervised learning is usually independent, while reinforcement learning methods deal with sequential decision-making problems, where training data in the sequence are dependent and non-independent. Reinforcement learning is often applied to UAV obstacle avoidance and trajectory planning. Nguyen [

39] designed a UAV-assisted IoT data collection system using reinforcement learning-based training methods to optimize UAV trajectories and throughput within a specific coverage area. Fu [

40] studied the application of UAVs with wireless charging capabilities in data collection tasks, proposing a reinforcement learning-based approach for UAV-enabled sensor data collection from distributed sensors in a physical environment. They divided the physical environment into multiple grids, where the hovering positions of the UAV and the wireless charging locations are at the center of each grid. Each grid has a designated hovering position and a wireless charger at the center of each grid can provide wireless charging to the UAV. They formulated the data collection problem as a Markov decision process and used Q-learning to find the optimal strategy. A cruise control method based on the deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm is proposed to optimize UAV heading and flight speed, as well as the selection strategy for data collection targets from ground sensors [

41]. This approach prevents ground sensor buffer overflows and packet loss during communication. Oubbati [

42] studied multi-UAV data collection tasks in IoT scenarios where UAVs provide energy to ground IoT devices through wireless energy transfer. They proposed a multi-agent reinforcement learning approach that divides UAVs into data collection teams and wireless charging teams to optimize the trajectories of both groups, aiming to minimize AoI, maximize IoT device throughput, and minimize UAV energy utilization.

Table 2.

Comparison of existing methods

Table 2.

Comparison of existing methods

| References |

Method |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| [39] |

Reinforcement learning-based training methods |

Practicality enhanced by grid-based path planning and autonomous UAV decision-making |

Limited by assumptions on user mobility |

| [40] |

Q-learning |

Focuses on energy efficiency, extending UAV operation time with wireless charging |

Limited adaptability to dynamic environments |

| [41] |

Deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) |

Significant reduction in data packet loss with continuous action space optimization |

High computational complexity and resource demands |

| [42] |

A multi-agent reinforcement learning approach |

Significant improvements in reducing AoI, increasing throughput, and energy efficiency |

High complexity and resource consumption |

2.3. Comparative Analysis of UAV Task Scheduling and Resource Allocation Models

Numerous extant methodologies, such as QEDU, TD3-OHT, and SCP, have made preliminary contributions to the domain of UAV task scheduling and resource allocation. However, these approaches still exhibit significant limitations when addressing critical issues such as dynamic adaptability, resource optimization, and energy efficiency. Although the QEDU and TD3-OHT models have achieved certain advancements in flight trajectory optimization and resource allocation, their primary drawback lies in their inability to adapt to dynamic environmental changes. Particularly in multi-task scenarios, these models fail to achieve an optimal balance between scheduling efficiency and energy consumption. On the other hand, while the SCP model has optimized task scheduling and resource allocation, it inadequately considers UAV energy efficiency and real-time decision-making, resulting in suboptimal performance during dynamic task execution. In contrast, the HDRL-TSRAM model overcomes these limitations by introducing a hierarchical deep reinforcement learning framework. Firstly, our model effectively decouples task scheduling and resource allocation through hierarchical processing. The lower-level network focuses on optimizing continuous actions, such as flight trajectories, communication power, and computational resources, while the upper-level network handles discrete actions, such as target assignment. This hierarchical design significantly enhances the system’s flexibility and real-time decision-making capabilities. Secondly, by integrating PPO and DQN algorithms, the fully trained lower-level network provides rapid global feedback to the upper-level network, thereby accelerating the training process and improving the adaptability and convergence of the policy. Through experimental validation, we have demonstrated that HDRL-TSRAM outperforms traditional benchmark methods in terms of data collection efficiency and UAV energy consumption, showcasing its greater potential and superiority for practical applications.

Table 3.

Comparison of Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning Models for UAVs.

Table 3.

Comparison of Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning Models for UAVs.

| Model |

Hierarchical RL |

Resource Allocation |

Energy Efficiency |

Dynamic Adaptability |

Real-time Decision |

| QEDU |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

| TD3-OHT |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

| SCP |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

| MADRL |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| DTDE |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

| HDRL-TSRAM |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

3. System model

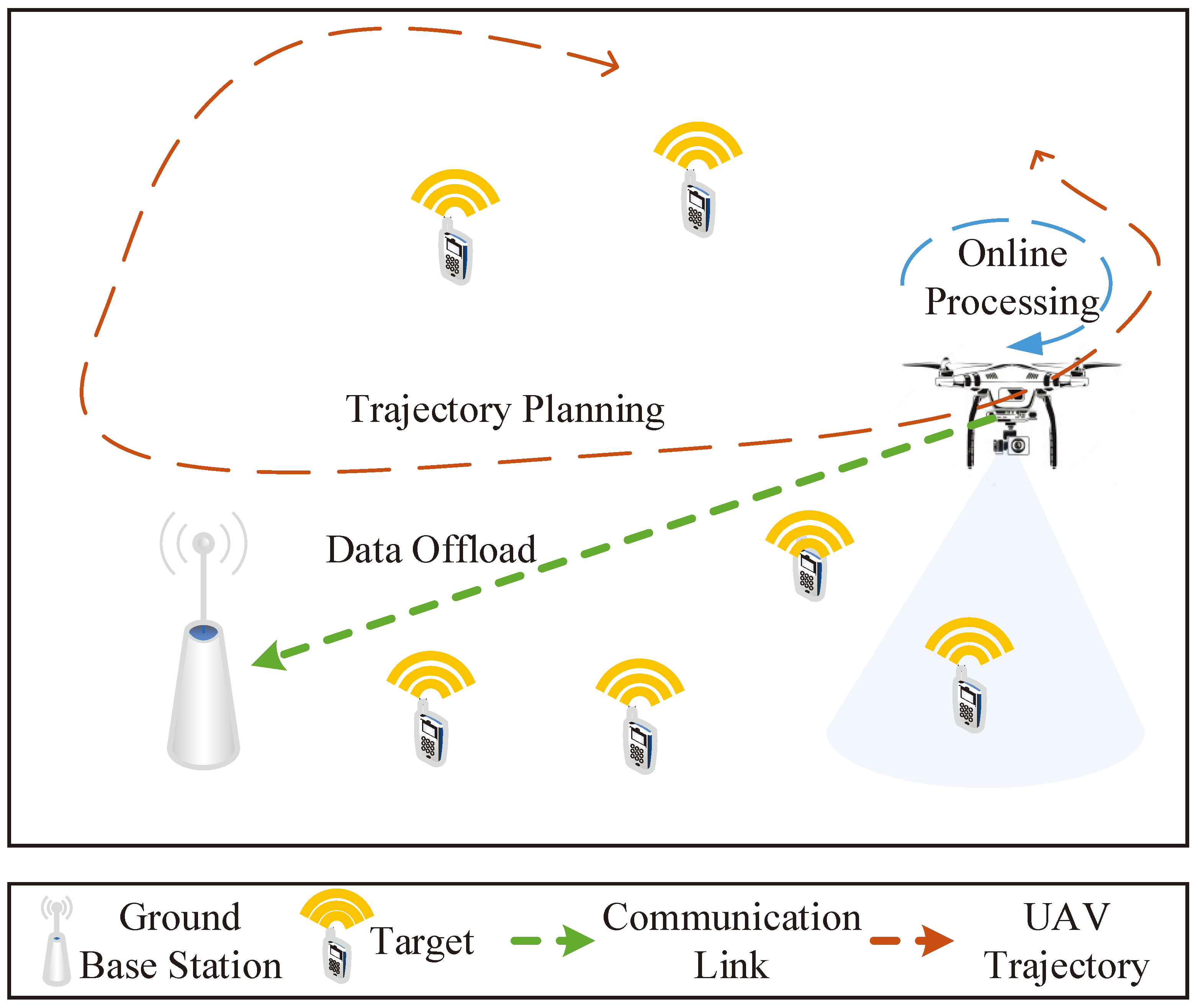

As shown in

Figure 1, the task scenario involves a UAV, a ground base station(GBS), and

M ground targets, which are denoted as

. The UAV collects high-definition images or video data of the targets through high-resolution cameras within a fixed area. Due to the limited storage space, UAV needs to process the data onboard or transmit it to the GBS for further processing during data collection. Additionally, the battery energy of UAV is restricted, which will support various activities such as aerial flight, hovering, onboard data processing, and data transmission. Therefore, efficient task scheduling and resource allocation are necessary to optimize the energy consumption and the size of data collection.

Table 4.

The Simulation Parameters

Table 4.

The Simulation Parameters

| Parameters |

Meaning |

Parameters |

Meaning |

| n |

Time slot |

|

Main frequency |

|

Flight time |

|

Dynamic transition matrix |

|

Collection time |

M |

Number of ground targets |

|

Flight power |

B |

Allocated communication bandwidth |

|

Hovering power |

|

Power of the random noise |

|

Distance |

|

Offloading data transmission |

|

Transmission power |

|

Effective conversion rate of UAV |

|

Energy consumption |

|

Prioritization matrix |

| C |

Number of CPU cycles |

|

Energy consumption penalty coefficient |

For ease of representation, the task time T is divided into N slots, and the duration of each slot should be sufficient to complete one data collection. Each slot consists of the flight time and the collection time , the former one depends on the flight distance, and the later one is fixed, thus the divided time slots vary in size.

Assuming that the maximum horizontal coverage radius of the UAV is

, the UAV can capture high-definition images of the target nodes within such a range. To conveniently denote the data collection relationship between the UAV and the target within any slot

n, This paper introduces a binary pointer as follows

where

indicates that the data of target

m will be collected at slot

n; otherwise,

. It should be noted that only the first collection result is valid when the same target is collected multiple times. In addition, the UAV can only collect data when the remaining cache is enough to complete one data collection. Hence, several constraints exist during the collection process as follows

where

represents the horizontal distance between the UAV and the ground target

m during time slot

n,

is the remaining cache of the UAV, and

is the amount of the collected data, which is fixed. The formula

2 indicates that only targets within the coverage range of the UAV can be collected data, formula

3 indicates that data collection for a target is only valid for the first time. Besides, a binary pointer is introduced to describe whether the UAV performs data collection tasks during time slot

n, which is denoted as follows

Considering that the energy consumption of the UAV is a key indicator for the data collection task, the corresponding models are built to measure the value quantitatively, which consists of the flight model, the communication model, and the computation as well as the cache model.

3.1. Flight Model

Similar to prior studies, this article adopts a 3-D Cartesian coordinate system to model the stereoscopic space [

43] of the data collection task. The UAV is assumed to move at the fixed heights

H, and the coordinates of UAV at time slot

n is denoted by

. The velocity of the UAV at time slot

n is assumed as

, and remains constant while ignoring the acceleration and deceleration processes, then the flight time

is given by

Besides, the UAV keeps hovering during the collection. Thus the flight energy consumption at each slot can be given as the following equation:

where

and

are the flight time and hovering time of the UAV at slot

n, respectively.

and

are the flight power and hovering power, which are fixed as constant.

3.2. Communication Model

During the collection, the UAV can offload the data to the GBS to alleviate the pressure of online processing. To simulate the communication process between the UAV and the GBS, an air-ground communication channel model is established, which can be regarded as a line-of-sight channel, since the obstruction is generally less in the air. The offloading data transmission rate can be expressed as

where

B is the allocated communication bandwidth, which is fixed. The frequency-division duplex is adopted for the uplink channel between UAV and targets as well as the downlink channel between UAV and GBS to avoid co-frequency interference.

is the received power at 1m position with a transmission power of 1W,

is the transmission power of the UAV at time slot

n,

is the relative distance between UAV and GBS,

is the power of the random noise. Therefore, the size of the offloaded data can be expressed as

It is worth noting that the UAV only transmits the data while hovering in the air, and the energy consumption for the communication between UAV and GBS can be formulated as

3.3. UAV Computation Model

Assuming that the main frequency of the UAV CPU at time slot

n is

when the UAV performs online processing on the cached data, and the energy consumption for computation is expressed as

where

is the effective conversion rate of UAV during online processing, and the amount of data processed online can be described as follows based on most existing research

where

C is the number of CPU cycles per input bit of the data to be processed.

3.4. Optimization Model

Taking into account the above models comprehensively, the optimization model of the UAV task scheduling and resource allocation for data collection application is established. We select the weighted sum of the total amount of information collected and the total energy consumption of the UAV as the optimization object. Among them, the priority of ground targets dynamically changes, and the information content of different priority targets varies. We model the change process of target priority as a Markov process, the target priority at the next slot is only related to the one at the current slot, which can be expressed as

where

is the prioritization matrix of ground targets at time slot

n,

is the dynamic transition matrix of target priority. The optimization objective is to maximize the amount of the collected data while reducing the energy consumption of UAV, and the final optimization model is formulated as follows

where

is the energy consumption penalty coefficient,

is the total energy consumption of UAV at slot

n,

is the amount of the collected data at time slot

n, which can be described as

is the set of the targets within the coverage range,

is the priority of target

m, and

means that target

m is first detected by UAV, otherwise

.

As for the constraints, limited the UAV trajectory, is the maximum flying distance of UAV within one time slot. is the coverage limitation, considering that the flight altitude of the UAV is fixed, the coverage range of the UAV is unchanged, and the target is believed to be within the UAV field of view when the relative distance is less than the coverage range. is the first-valid limitation. means that the total energy consumption of the UAV should be under the budget . is the causal constraint, which means that the amount of the online processed data and the offload data at time slot n can not exceed the amount of the data cached on the UAV. indicates that data collection cannot be performed when the remaining cache space is insufficient, is the maximum cache space of the UAV.

4. Hierarchical DRL Method

The deep reinforcement learning (DRL) approach utilizes the Markov decision process (MDP) to make decisions in a given environment. The MDP is described by four tuples [, , , ]. is the possible states of the agent in time slot n; is the available actions; is the reward when the agent interacts with the environment, which is given by: , and is the state in next time slot under . The object of the DRL method is to learn a policy to maximize the long-term reward.

Although DRL methods can learn strategies through interaction with the environment and fit the mapping relationship from state to action through neural networks, the large-scale distribution of ground targets leads to explosive growth in their state combination space. It is difficult to learn the mapping from all states to the optimal action through interaction with the environment. Besides, the proposed problem (P1) is mixed, where the task scheduling is a discrete action while the resource allocation is a continuous one the training of the mixed problem is under-explored in existing research.

To address the above issues, the layered decoupling idea is introduced into the DRL methodology, and a hierarchical DRL based task scheduling and resource allocation method is proposed, aiming to optimize the trajectory, transmission power, as well as CPU main frequency of the UAV jointly under random and large-scale targets distribution.

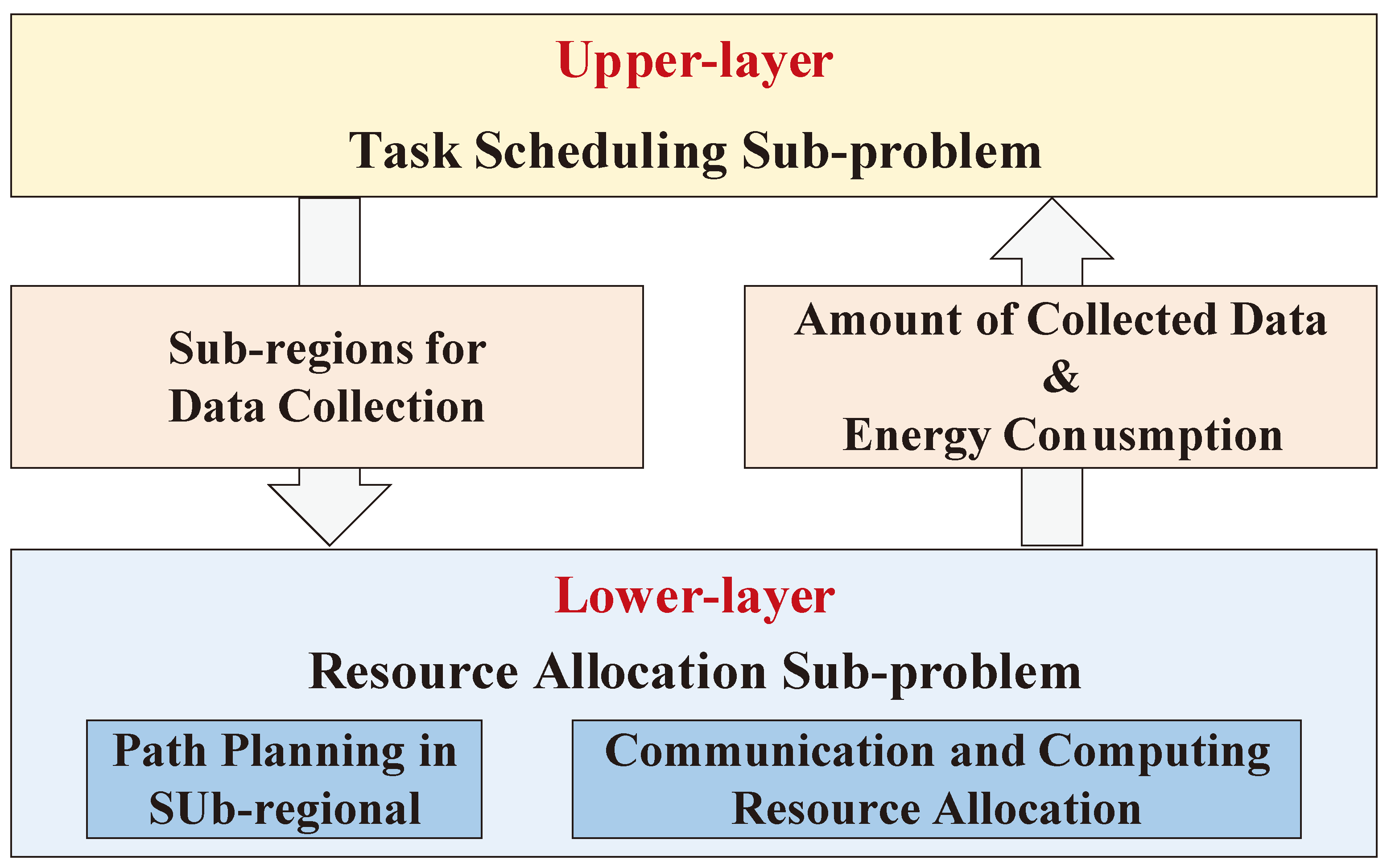

HDRL-TSRAM divides the original problem (P1) into the lower-layer subproblem and upper-layer subproblem and establishes the corresponding environment respectively. The former is responsible for resource allocation, and the latter is responsible for task scheduling. The algorithm complexity can be reduced by cutting down the range of the state space. The framework of the proposed HDRL-TSRAM is shown in

Figure 2, the target region is divided into a certain number of equally sized sub-regions, and the dynamic changes in target priority within the sub-regions can be approximately ignored. Therefore, the lower-layer can use the shortest path principle (traveling salesman problem, TSP) to plan the trajectory of UAV in the sub-region, while optimizing their corresponding communication and computing resources. At the upper layer, only the order of access to each sub-region needs to be optimized, that is, task scheduling. After layering, different types of DRL methods (value-based and policy-based) can be used to train the upper-layer and lower-layer decision networks, reducing the overall algorithm complexity.

4.1. Lower-layer Network

With the variables

and the relative constraints from (P1), the optimization problem of the lower layer is formulated as follows:

where

i is the number of sub-region,

is the set of task times for UAV in sub-region

i.

It is worth noting that the lower-layer considers the path planning problem as a TSP, thus the flight time can be calculated by solving for the shortest flight path

where

is the shortest path for the UAV to access all targets in the sub-region

i,

v is the UAV cruise speed in the sub-region

i. Set the number of targets in the sub-region

i to

, the collection time is fixed at

, and the total flight energy consumption in sub-region

i can be expressed as

The energy consumption for communication and computation is the same as the ones in (P1).

4.1.1. LKH-based UAV Trajectory Planning Algorithm

TSP is a classic combinatorial optimization problem, whose goal is to find the shortest path given a set of cities and their distance relationship, so that the traveling salesman starts from one city, visits all other cities exactly once, and finally returns to the starting city. Therefore, the shortest UAV trajectory planning problem within the sub-regions can be regarded as a TSP for solving.

The Lin-Kernighan-Helsgaun (LKH) method is considered one of the most effective heuristic algorithms to solve TSP, and the scale of the targets is small in the sub-regions after dividing, thus the solution can be quickly and effectively obtained. The LKH algorithm is developed from the Lin Kernighan (LK) heuristic algorithm. The LK algorithm adopts a local search strategy called 2-opt exchange, which continuously exchanges edges in the path to reduce the total path length. On this basis, the LKH algorithm has introduced some improvements and extensions, making the algorithm have better performance in solving large-scale TSP. The initial position of UAV is set in the center of the sub-region, we use the LKH algorithm to obtain the shortest path for the UAV to access all targets from the center of the current sub-region, the detail is shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1: LKH based UAV Trajectory Planning Method |

- 1:

for episode=1,…,10000 do

- 2:

Generating an initial solution using greedy algorithms. - 3:

Using k-opt exchange for local search strategy to form new paths. - 4:

Adopting a backtracking strategy to record historical optimal solutions during the search process. - 5:

end for - 6:

Output the historical optimal solutions. |

In step 2, the initial solution may not be the optimal solution, but it can serve as the starting point for optimization. In step 3, k-opt exchange refers to attempting to disconnect k edges and reconnect them based on the current solution. In step 4, the LKH algorithm adopts a backtracking strategy to avoid getting stuck in local optima and backtracks to the historical optimal solution under certain conditions to escape the trap of local optima. In addition, the LKH algorithm also introduces a branch and bound strategy, which determines whether to search for sub-problems by predicting their lower bounds to reduce search space and improve solution efficiency.

Algorithm 1 has a time complexity of , where 10000 represents the number of iterations, k is the number of k-opt exchanges in the local search step, and n is the number of nodes in the UAV trajectory. This complexity arises from the combination of the greedy initialization, the k-opt local search, and the backtracking strategy used to track historical optimal solutions.

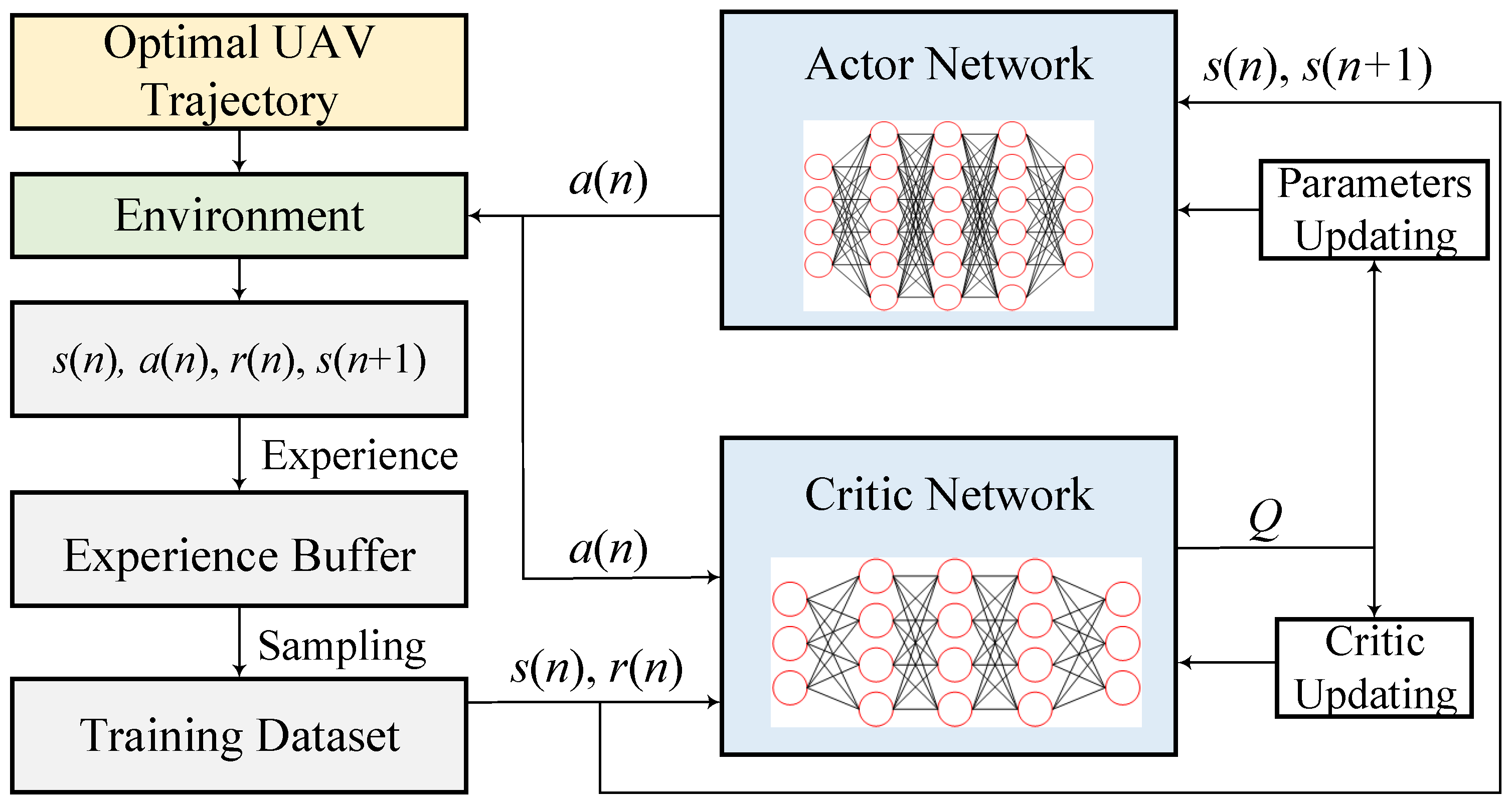

4.1.2. DRL-based UAV Resource Allocation Algorithm

With the optimal trajectory, the lower-layer network (LLN) utilizes the DRL method to optimize the communication and computation resource of UAV, which correspond to UAV CPU main frequency and UAV transmission power respectively. Considering that both the variables above are continuous, the policy-based proximal policy optimization (PPO) is used to train the lower-layer network.

PPO is based on the Actor-Critic framework, which combines policy gradient and function approximation. The Actor provides an action while the Critic evaluates the value of the selected action. Then the Actor will update its parameters according to the feedback of the Critic. The training objective of the Actor is to generate action with the maximal Q value, while that of the Critic is to estimate the Q value accurately.

We define the state space, action space, and reward function for the LLN in our scenario as follows:

1)

State: The state space

consists of the remaining UAV battery energy, the remaining UAV cache, the relative distance between UAV and GBS, the remaining task time, and the target number in current sub-region, which is formulated as:

where

is the remaining task time, and the initial values of the remaining UAV battery energy

and the remaining UAV cache

are set randomly to cover all situations as much as possible, which is formulated as follows

where

and

is the minimum energy and cache that can ensure the progress of the task.

2)

Action:

is a set of actions for UAV at time slot

n, which consists of the UAV CPU main frequency and the UAV transmission power.

is expressed as

3)

Reward:

is a set of rewards obtained at time slot

n, which is formulated as

where

is the total amount of data processed within slot

n, including the amount of data processed online and the amount of data offloaded to GBS.

The training framework of the lower-layer is shown in

Figure 3, the actor network generates action and interacts with the environment according to the current status and policy

, and the generated four tuples will be stored in the experience buffer, where LLN samples data from to form the training dataset. The buffer model in this study represents a finite-capacity queue that temporarily stores incoming data packets during jamming attacks, enabling controlled transmission and mitigating delays, and it supports evaluating network performance under adversarial conditions. The estimated value of the advantage function for each sample is calculated by the following equation:

where

is the Q value of the state-action

, and

is the value of state

.

The loss function of the actor network varies in forms, the objective function of cropping or the objective function of confidence domain for example. the latter is utilized to update the parameters of the policy, and the loss function is defined as follows

where

is the parameters of actor network, the clip function restricts the gradient update amplitude through cropping,

represents the probability ratio of the current policy to the past policy selection action

, which is formulated as

The time difference approach is utilized to define the loss function of the critic network

where

is the parameters of the critic network,

is the total discount reward, and the training process of LLN is shown in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2: PPO based Training Scheme for Lower-layer network |

- 1:

Initial the netowrk parameter and . - 2:

Initialize the experience buffer. - 3:

for episode=1,…,10000 do

- 4:

Setup the environment and select an initial state . - 5:

for n=1,…,N do

- 6:

Generate an action . - 7:

Execute and calculate the using Eq.( 22). - 8:

Update the state . - 9:

Store the experience . - 10:

if The experience buffer is filled then

- 11:

Sample mini-batch from experience buffer. - 12:

Update the parameters of the critic network using Eq.( 26). - 13:

Update the parameters of the actor network using Eq.( 24). - 14:

end if

- 15:

end for

- 16:

end for |

4.2. Upper-layer Network

With the variables

and the relative constraints from (P1), the optimization problem of the upper layer is formulated as follows:

where

is the task schedule instruction for sub-region

i,

means that UAV performs data collection task in sub-region

i,

I is the total number of sub-region. C2 is the cache constraint for the upper layer to avoid partial collection data loss caused by cache overflow,

is the amount of the cached data in UAV after the

i-th data collection,

is the amount of collected data in the

i-th data collection. C3 is the energy constraint for the upper layer,

is the energy consumption for the

i-th data collection, which can be expressed as:

where

is the energy consumption for the flight from

st sub-region to

i-th sub-region,

is the relative distance between the two sub-region.

is the energy consumption for the communication and computation in sub-region

i, which can be obtained from the lower layer.

In the upper layer, it is not necessary to consider the resource allocation of UAV, as the resource allocation strategy is utilized as a known quantity to plan the overall service order of the UAV between sub regions. The ultimate subjective function is to maximize the overall data collection volume while minimizing the total energy consumption.

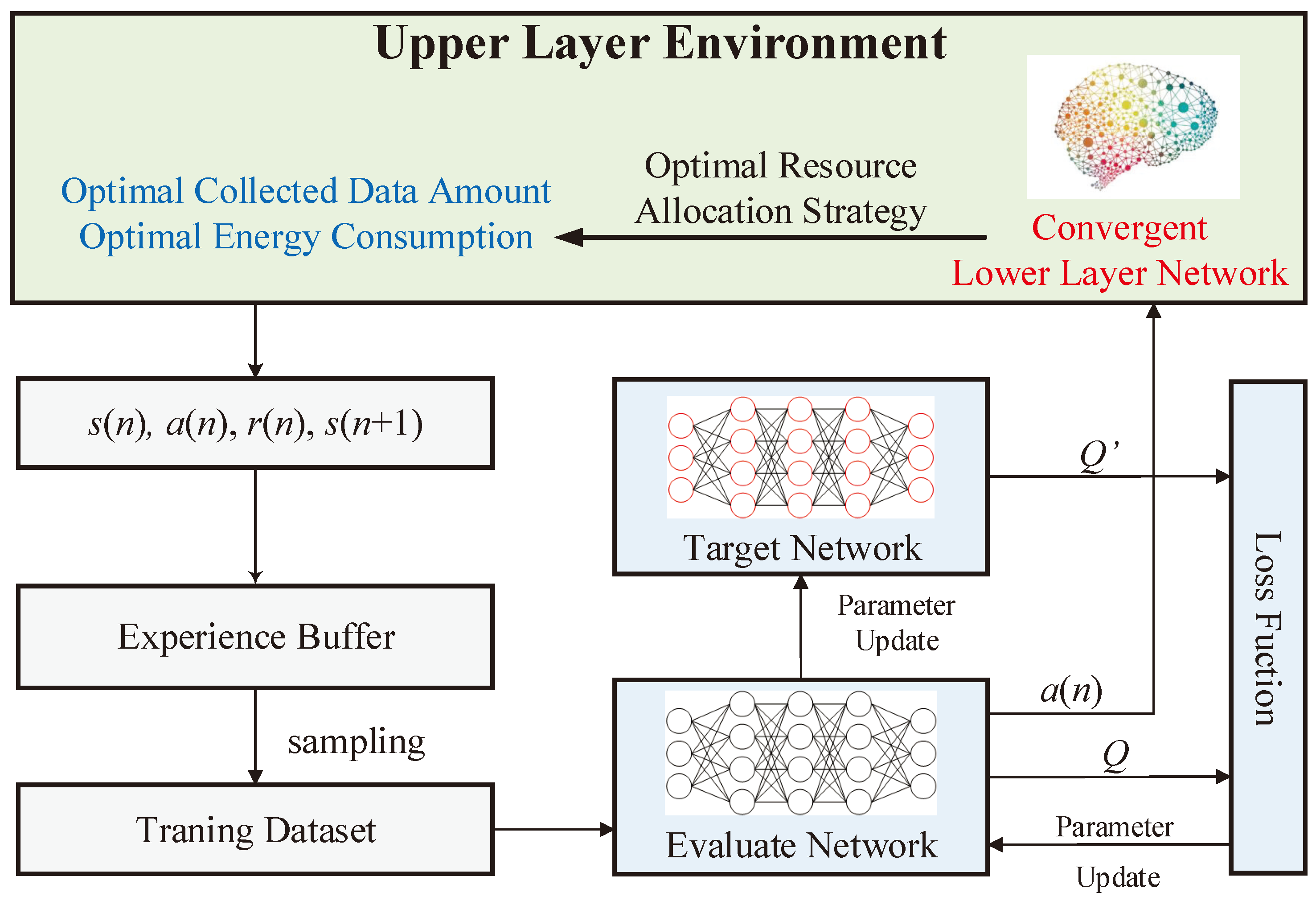

Considering that the optimization variable is discrete, the value-based deep Q-learning (DQN) is used to train the upper-layer network (ULN). DQN utilizes a deep neural network (DNN) to estimate the Q-value and avoids the limitation of the traditional Q table. For a given state, the Q value of the selected action is calculated by the DNN. Besides, DQN designs two DNNs to prevent overfitting: the Evaluation Network and the Target Network, which share the same structure but with different parameters. The former network updates the parameters continuously, while the parameters of the latter are temporarily fixed to disrupt the correlation between samples. The state space, action space, and reward for the ULN are defined in the following.

1)

State: The state space

consists of the remaining UAV battery energy, the remaining UAV cache, the relative distance between UAV and GBS, The number of targets in each sub region that have not collected data, sub-region number of the UAV currently located, and the priority of targets within each sub region, which is formulated as:

where

is the prioritization matrix of the ground targets in sub-region

i, which will be updated at regular intervals, and its change model is also modeled as a Markov process.

2)

Action:

is a set of actions for UAV, which consists of the sub-region number for the next data collection.

is expressed as

3)

Reward:

is a set of rewards obtained at

i-th sub-region selection, which is formulated as

The framework of the upper layer training method is shown in

Figure 4. The ULN also consists of an evaluation network and a target network. The evaluation network generates an action first, which is:

where

is the parameters of the evaluate network. The action is sent to the upper-layer environment, which is the convergent LLN. Once the ULN generates the sub-region allocation, the environment of the upper layer utilizes the convergent LLN to obtain the optimal resource allocation strategy in real time. With the assistance of LLN, the reward of the upper layer

can be calculated with Eq.(

31), the form of nesting the LLN in the upper layer accelerates the convergence speed of upper layer training. Same with the training process of the lower layer, the experience

is sent to the buffer, and the target Q-value is calculated as follows:

where

is the parameters of the target network. When the experience buffer is filled, the evaluation network selects a mini-batch of samples to update its parameters as follows:

where

is the learning rate. The parameters of the target network are also updated by the soft updating method:

The training strategy for the ULN is summarized as Algorithm 3.

|

Algorithm 3: Training strategy for the ULN |

- 1:

Initialize the evaluate network . - 2:

Initialize the target network with parameters . - 3:

Initialize the experience buffer . - 4:

for episode=1,…,10000 do

- 5:

Setup the environment and reset the initial state . - 6:

for i=1,…,I do

- 7:

Choose an action using Eq.( 32). - 8:

Execute and calculate the using Eq.( 31). - 9:

Update the state . - 10:

Store the experience . - 11:

if The experience buffer is filled then

- 12:

Sample mini-batch from the experience buffer randomly. - 13:

Calculate the target Q-value using Eq.( 33). - 14:

Update the parameters of the evaluate network using Eq.( 34). - 15:

Update the corresponding parameters of the target network using Eq.( 35). - 16:

end if

- 17:

end for

- 18:

end for |

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1. Experimental Setup

Our experiments utilized a custom simulation environment based on the PyTorch framework. The initial position of the GBS is [0,0], the initial position of the UAV is [100, 100], and the coordinate of ground targets is randomly generated. The initial priority of ground targets is divided into four levels, with the highest being level IV and the lowest being level I. Level I targets account for about 35%, while level II and III targets account for about 25% and level IV targets account for about 15% respectively. The priority of targets will dynamically change. The priority dynamic transfer matrix is shown in

Table 5, and the information content of each priority level target is shown in

Table 6. Our design is intended to ensure the stochastic nature of target priorities, thereby simulating the variability and uncertainty of diverse targets at distinct time points. We have conducted multiple rounds of experiments to ensure the reproducibility of the results. We are confident that these experiments effectively validate the stability and reliability of the algorithm.

The task scenario is a size of 1000×1000m square area with 20-100 randomly distributed ground targets. The UAV flies at a constant speed of 20m/s. It takes 10 seconds to collect ground target image data, and the task time is 30 seconds when there is no target. The maximum calculation frequency of the UAV is 10GHz, and the amount of data collected in a single data acquisition is 5GB. The maximum data transmission power is 100W, the communication bandwidth is 20MHz, the flight power is 110W, the aerial hovering power is 80W, the UAV battery energy is 2000kJ, and the flight altitude is 100m.

In the lower layer, the PPO based LLN is compared with the soft actor-critic (SAC) and the genetic algorithm (GA), and the corresponding parameter is shown in

Table 7.

5.2. Numerical Results

5.2.1. Experimental Verification of Lower Layer Network

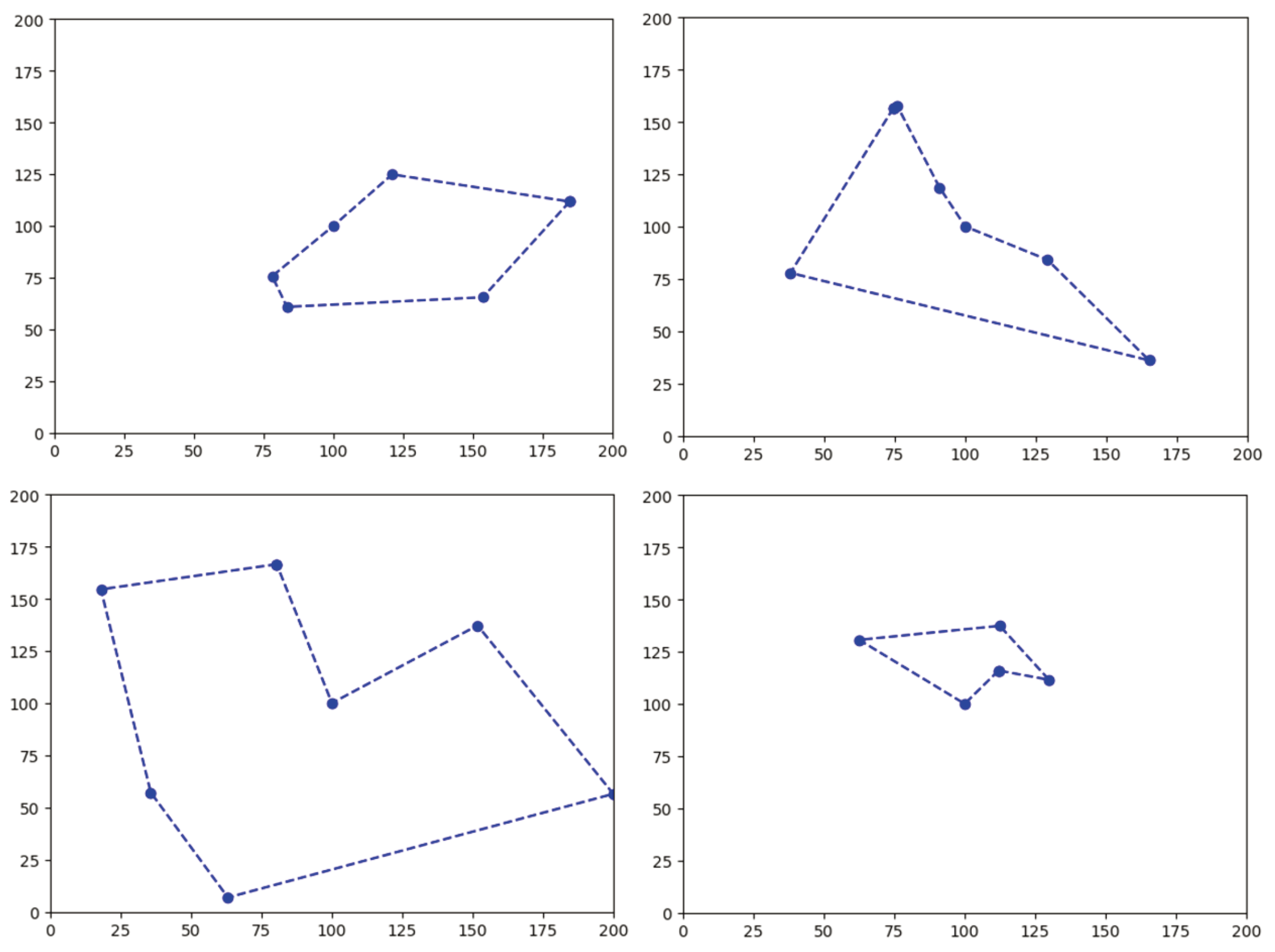

The underlying UAV trajectory planned by the LKH algorithm is shown in

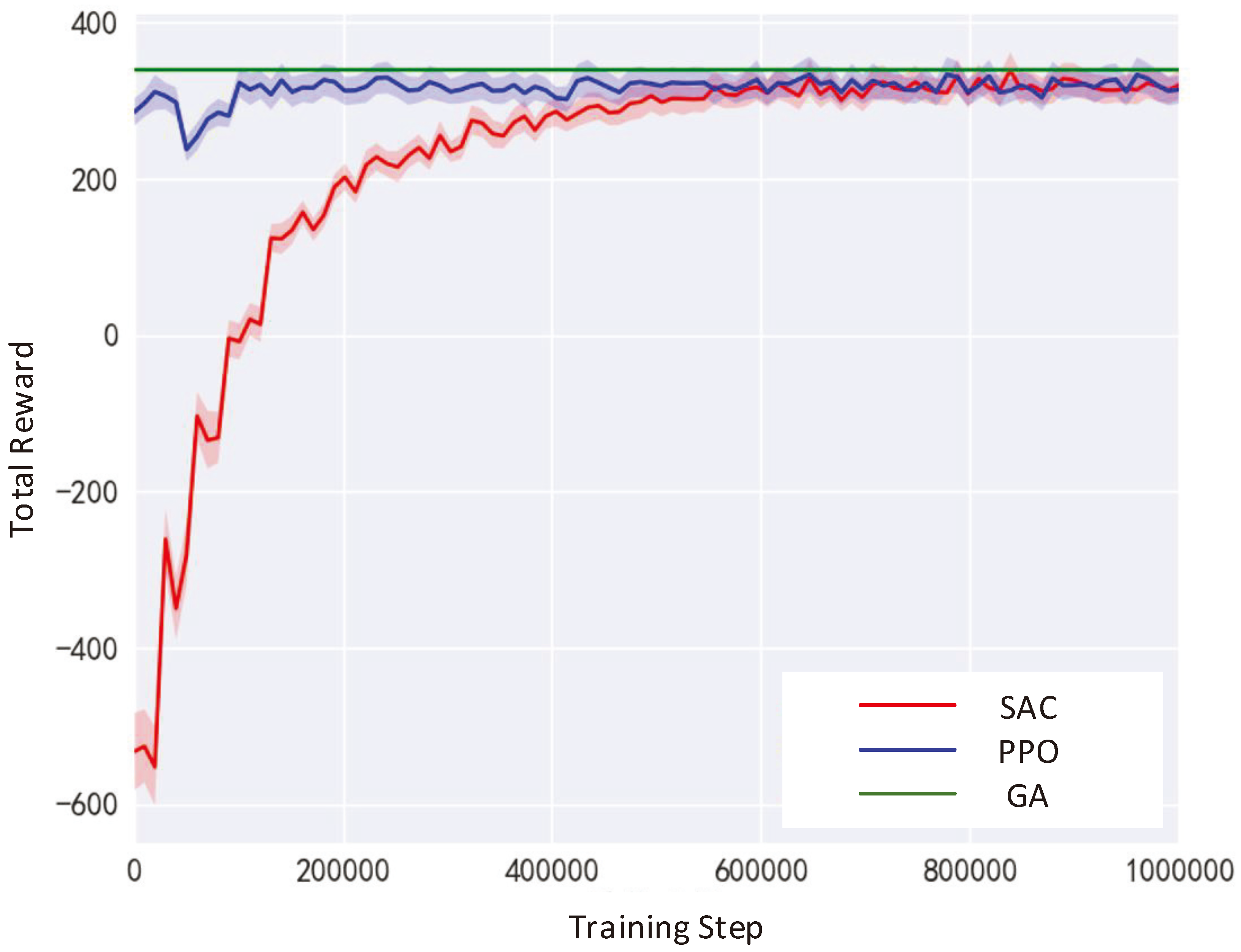

Figure 5, which is the shortest trajectory for the UAV to traverse all ground targets in the sub region starting from the center of the sub region and then return to the center of the sub region. The average total reward for the SAC, PPO, and GA in the lower layer is 338.6, 338.3, and 340.5, respectively. The average total reward for the SAC is similar to PPO, slightly lower than that of the GA, However, the SAC algorithm and PPO algorithm can complete the allocation of UAV resources with any initial cache and battery energy after completing the training process, while the GA needs to recalculate in each new scenario.

Figure 6 shows the curve graph of the reward obtained by SAC and PPO as a function of the number of training steps. The average total reward after the convergence of the two algorithms is similar. However, PPO has higher data utilization and faster convergence compared to SAC, and converges faster with less empirical data. GA needs to recalculate and optimize in each scenario.

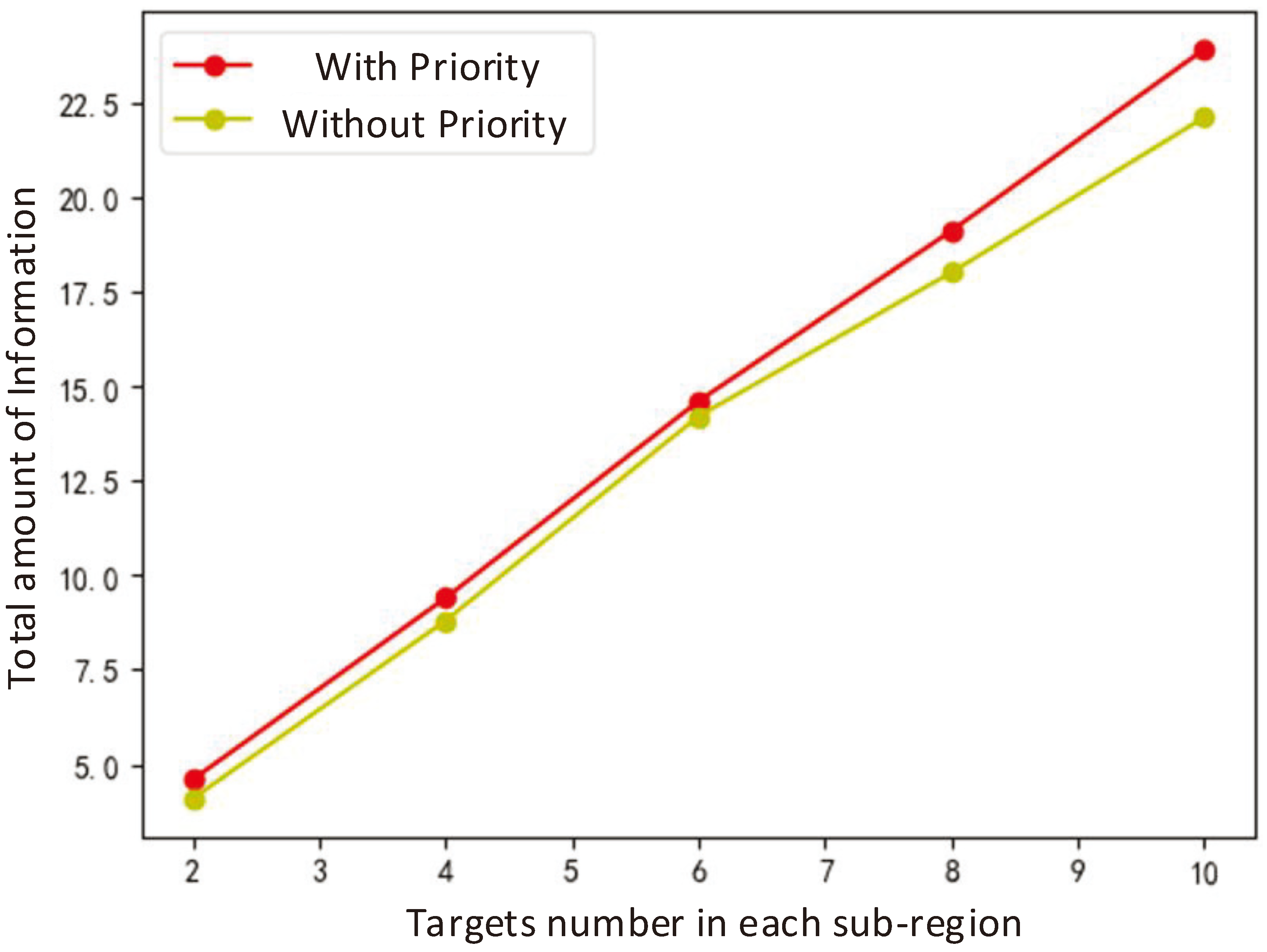

To verify the rationality of using the shortest path algorithm for trajectory planning and reinforcement learning algorithm to optimize resource allocation without priority changes in the lower layer, experiments were conducted under the conditions of target numbers 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 in sub-regions. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 7, and the performance difference between the two algorithms is within 5%.

5.2.2. Experimental Verification of Upper Layer Network

The validation scenario for the upper layer algorithm is a size of 1000m×1000m square area, which is divided into a 5×5 grid, and each grid is a 200m×200m sub-region, which is with a certain number of distributed targets. The upper layer utilizes DQN to train the UAV task scheduling strategy with the assistance of the resource allocation strategy trained in the lower layer. DQN series of algorithms are the most commonly used deep reinforcement learning algorithms for solving discrete action spaces.

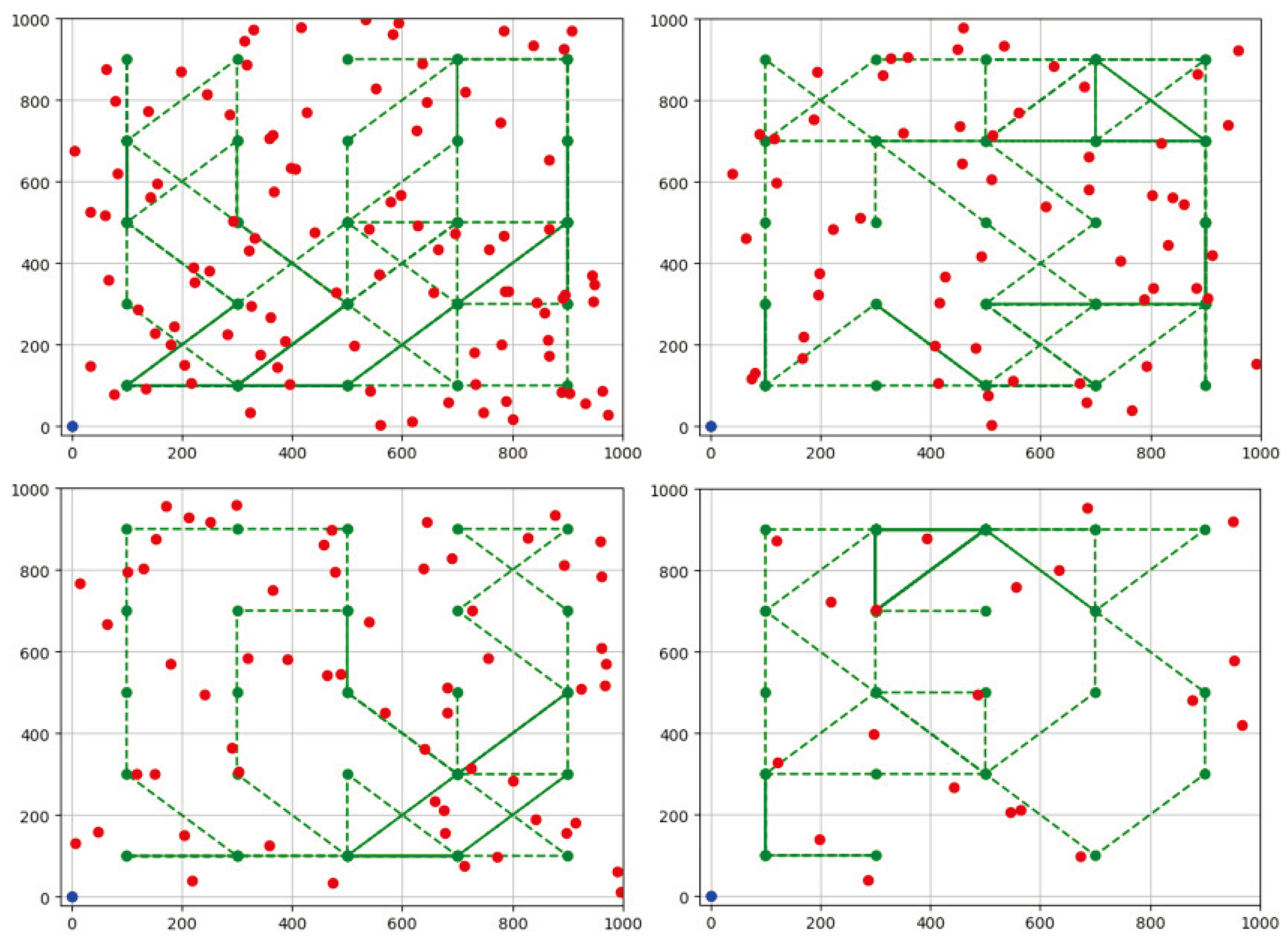

The top-level trajectory planning results of the UAV are shown in

Figure 8. The red dots represent the distribution of ground targets, the green dots and green dashed lines represent the UAV’s position and trajectory, and the purple dots represent the ground processing units. To reduce the complexity of algorithm solving, (1) in the trajectory planning process of this chapter, it is assumed that the dwell time in each sub-region is the total time for completing data collection for all targets and rounding up the data collection time [

44]. If there are no targets present or all target data has been collected, data processing is carried out in that sub-region for a duration of 30 seconds; (2) The optional action space for UAV in flight decision-making is to fly to the nearest 9 sub regions, including the current sub region. If there are targets in the target sub region that have not been collected data, the data will be processed simultaneously during data collection. If there are too many targets in the selected sub region and the current remaining cache is insufficient, they will stay in the current sub region; (3) Allocate an average of 30 seconds for data collection of each ground target, and after exceeding the total time, the data collection task ends.

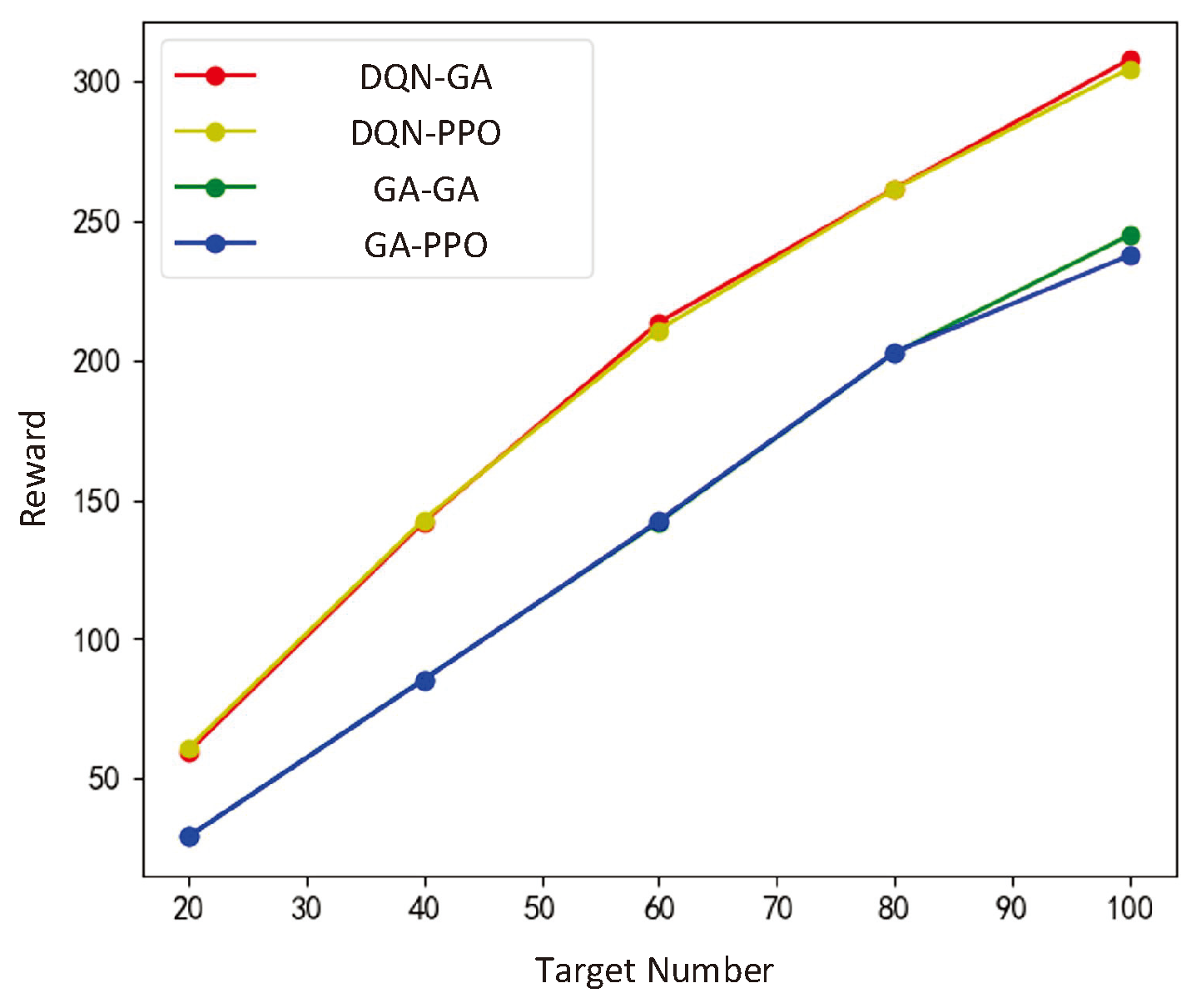

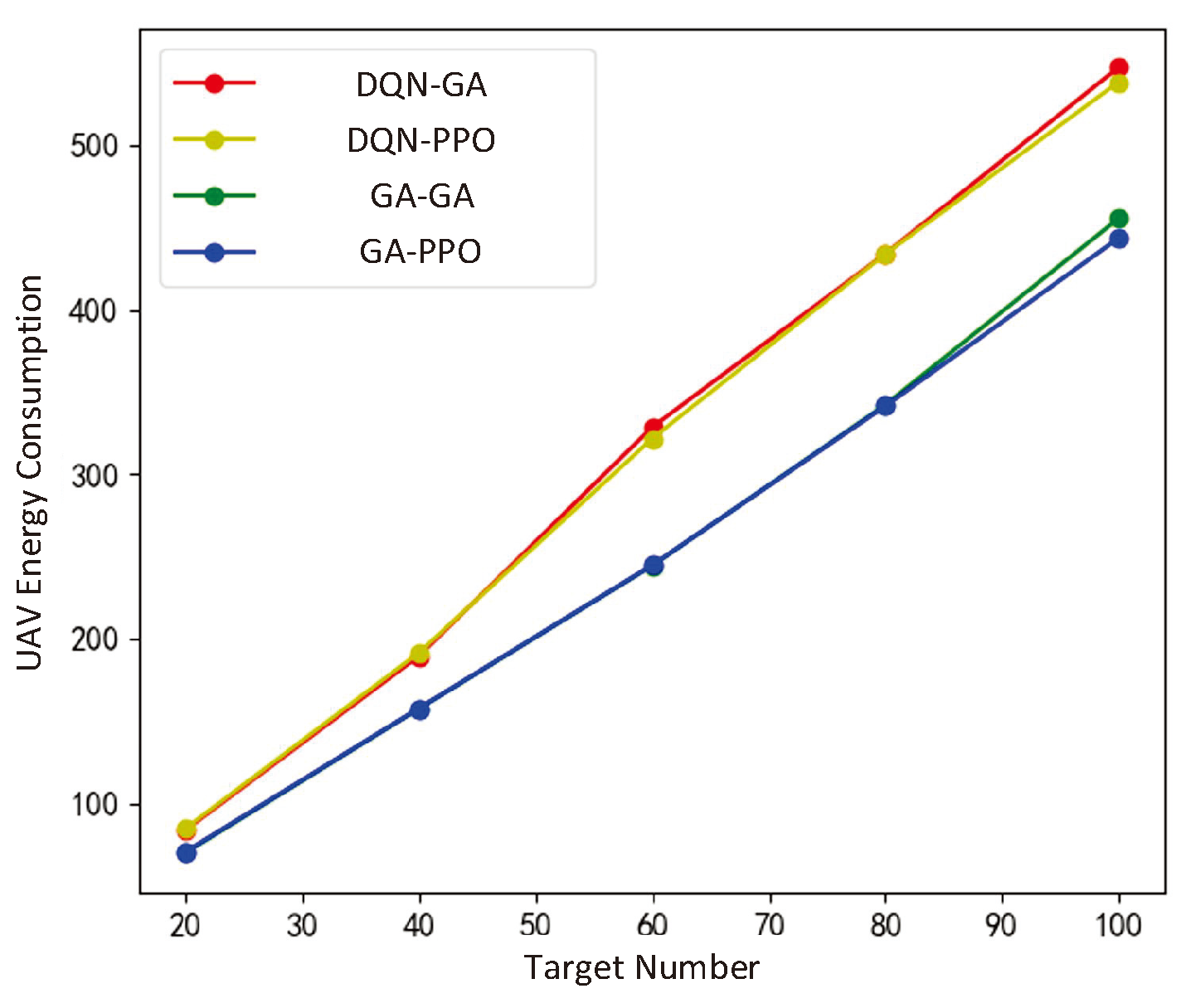

This section randomly generated a large amount of target distribution data for algorithm training, which met the constraint that the total number of targets should not exceed 100 and the number of targets in a single sub-region should not exceed 10. Then, tests were conducted on the 4 combinations, which is GA in the lower layer-GA in the upper layer, DQN in the lower layer-GA in the upper layer, GA in the lower layer+PPO in the upper layer, DQN in the lower layer-PPO in the upper layer. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 9 to

Figure 10. Reward, UAV energy consumption, and information collection are key indicators for evaluating algorithm performance. The reward is dimensionless, reflecting the overall effectiveness of the task scheduling algorithm; UAV energy consumption is measured in watt-hours (Wh), indicating the total energy expended by the UAV to complete tasks; and the amount of information collected is quantified in gigabytes (GB), representing the total volume of effective information gathered during task scheduling.

When the storage space of the UAV is 128GB and the number of ground targets is 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100, the optimization results of each algorithm are shown in

Figure 9. The impact of PPO and GA in the lower layer on the upper layer is almost the same. Any algorithm used in the lower layer can achieve the same performance, while PPO has a longer training time compared to GA. However, after training, decisions can be made directly after reaching any sub-region without resolving.

The proposed DQN-based ULN achieved UAV task scheduling under random target distribution. When faced with constrained target distribution, it can traverse various sub regions to complete data collection. Moreover, compared to GA, the average total reward per round is higher, up to 65% higher than the genetic algorithm. It outperforms in data collection for ground targets, but the corresponding energy consumption increases by 20% -30% compared to GA. The trend of the total information collected is the same as the trend of the total reward, DQN is superior to GA. In addition, DQN can handle various ground target distributions that satisfy assumptions once trained, while GA needs to recalculate when encountering new ground target distributions.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning-based Task Scheduling and Resource Allocation Method (HDRL-TSRAM) for UAV-enabled data collection applications, addressing the critical challenges of optimizing energy efficiency and adaptability in dynamic environments. By decoupling the complex joint optimization problem into a two-layer hierarchical framework, our approach significantly advances the state of the art: the lower layer employs a Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)-based algorithm to optimize continuous actions (trajectory, communication power, CPU frequency), while the upper layer utilizes a Deep Q-Network (DQN) strategy for discrete task scheduling, effectively reducing computational complexity and enabling efficient training in large-scale scenarios. A key innovation lies in integrating the Lin-Kernighan-Helsgaun (LKH) heuristic with DRL, where LKH solves the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) for local trajectory planning within sub-regions, and DRL dynamically adapts to global resource constraints and environmental changes, achieving 65% higher data collection efficiency and 20–30% lower energy consumption compared to baseline methods like genetic algorithms (GA) and standalone SAC. Unlike static optimization approaches requiring recalibration for environmental shifts, our framework inherently adapts to dynamic target priorities modeled via Markov processes, with a nested training architecture that accelerates convergence by leveraging pre-trained lower-layer networks for rapid reward feedback. Furthermore, we holistically integrate energy models for flight, communication, and computation—often overlooked in prior work—to balance data collection volume and energy efficiency, crucial for mission-critical applications like disaster monitoring. Practical implications include real-world deployment in scenarios such as post-earthquake reconnaissance, where UAVs autonomously prioritize high-impact areas while conserving energy. Despite these advancements, future work should address limitations such as predefined priority transition assumptions and simplified maneuverability models, while extending the framework to multi-UAV systems for large-scale surveillance. Overall, HDRL-TSRAM sets a new benchmark for UAV task scheduling, bridging theoretical optimization with real-world applicability through scalability, adaptability, and energy-conscious design.

7. Discussion

While this study has yielded notable advancements in the trajectory planning and resource allocation for UAV data collection missions, there remain several avenues for improvement: (1)The dynamic characteristics of the environment considered in this work pertain solely to the dynamic changes in the priority of ground targets. However, in real-world scenarios, such dynamic characteristics may not be predetermined. Consequently, the development of models to capture the dynamic priority of targets in unknown environments remains an open research question; (2)Beisdes, this study has primarily emphasized the efficacy of the algorithms employed. The environmental modeling for UAV data collection tasks is relatively rudimentary, encompassing models such as the channel, cache, computation, and UAV maneuverability models. The cache model fails to account for the correlation of onboard data, while the UAV maneuverability model neglects acceleration, deceleration, and turning maneuvers. Thus, further research is warranted to enhance the sophistication of environmental modeling.

References

- Hanscom, A.; Bedford, M. Unmanned aircraft system (uas) service demand 2015-2035. Literature review and projections of future usage 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, W.; Liang, W.; Peng, J.; Jia, X.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L. Nonredundant information collection in rescue applications via an energy-constrained UAV. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 6, 2945–2958. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Nguyen, C.V.; Do, H.T.; Hua, H.T.; Tran, T.A.; Nguyen, A.D.; Ala, G.; Viola, F. Uav-assisted data collection in wireless sensor networks: A comprehensive survey. Electronics 2021, 10, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Schmeink, A. Joint User Scheduling and UAV Trajectory Design on Completion Time Minimization for UAV-Aided Data Collection. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, N.; Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Meng, Z.; Wu, H.; Feng, Z. UAV-assisted data collection for internet of things: A survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 15460–15483. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K. Emerging UAV technology for disaster detection, mitigation, response, and preparedness. Electronics 2022, 39, 905–955. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Li, D.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, S. Joint speed and bandwidth optimized strategy of UAV-assisted data collection in post-disaster areas. In Proceedings of the 2022 20th Mediterranean Communication and Computer Networking Conference (MedComNet). IEEE; 2022; pp. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Song, X.; Cao, J.; Qiu,W. Providing aerial MEC service in areas without infrastructure: A tethered-UAV-based energy-efficient task scheduling framework. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 25223–25236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Ghosal, A.; Conti, M. Dynamic Super Round-Based Distributed Task Scheduling for UAV Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022, 22, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Cheng, Y.; Lei, X.; Peng, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, S. Resource allocation in UAV-assisted networks: A clustering-aided reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 71, 12088–12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wu, Q.; Hu, R.Q. Resource allocation and trajectory design for miso uav-assisted mec networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 71, 4933–4948. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Ding, Y.; Cao, M.; Wu, M.; Lu, W. and Nallanathan, A. Energy Efficiency Optimization of RIS-Assisted UAV Search-Based Cognitive Communication in Complex Obstacle Avoidance Environments. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology.

- Wang, Z.; Wen, J.; He, J.; Yu, L. and Li, Z. Resource and Trajectory Optimization for Secure Enhancement in IRS-Assisted UAV-MEC Systems. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking.

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J. and Zhao, L. Joint Trajectory Optimization and Resource Allocation in UAV-MEC Systems: A Lyapunov-Assisted DRL Approach. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing.

- Shen, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, N.; Cui, Y.; Cheng, X. and Mu, X. Joint Clustering and 3-D UAV Deployment for Delay-Aware UAV-Enabled MTC Data Collection Networks. IEEE Sensors Letters 2024, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Chang, T.H.; Shen, C.; Chen, X. Aviation time minimization of UAV for data collection from energy constrained sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Chang, T.H.; Shen, C.; Chen, X. Flight time minimization of UAV for data collection over wireless sensor networks. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2018, 36, 1942–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Xu, X.; Han, S. Energy-efficient UAV trajectory planning for data collection and computation in mMTC networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Zhang, X.; She, Y.; LI, B. and Zhang, Q. Trajectory Planning for UAV Swarm Tracking Moving Target Based on an Improved Model Predictive Control Fusion Algorithm. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Rong, Y.; Zeng, Y. and Zhang, R. Joint Optimization of Transmit Power and Trajectory for UAV-Enabled Data Collection With Dynamic Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Dai, C.; Yi, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, X. and Zhu, K. A Learning-Based Stochastic Game for Energy Efficient Optimization of UAV Trajectory and Task Offloading in Space/Aerial Edge Computing. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, B. and Li, L. Dynamic Trajectory Planning for Multi-UAV Multi-Mission Operations Using a Hybrid Strategy. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, X. and Cai, H. In Joint Trajectory and Resource Allocation Optimization for UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the 2024 16th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (2024 WCSP). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1068–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P.; Wu, X.; Ding, R.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Z. and Zhou, H. Joint Resource Allocation and UAV Trajectory Design for D2D-Assisted Energy-Efficient Air–Ground Integrated Caching Network. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 17558–17571. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.; Ahmad, A.; Alwarafy, A.; Shah, M.; Lakas, A. and Azeem, M. Efficient Resource Allocation and UAV Deployment in STAR-RIS and UAV-Relay Assisted Public Safety Networks for Video Transmission. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Yan, Y.; Gao, F.; Ge, B.; Wei, M.; Shangguan, B. and He, G. C3DGS: Compressing 3D Gaussian Model for Surface Reconstruction of Large-Scale Scenes Based on Multiview UAV Images. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2025, 18, 4396–4409. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao, E.; Veiga-López, F.; Miguel González-deSantos, L. and González-Jorge, H. Enhancing UAV Classification With Synthetic Data: GMM LiDAR Simulator for Aerial Surveillance Applications. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 26960–26970. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Kuang, Z.; Huang, Z. and Lin, S. Security Offloading Scheduling and Caching Optimization Algorithm in UAV Edge Computing. IEEE Systems Journal 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Li, K.; Xiong, X. and Lin, Y. Heterogeneous UAV Resource Scheduling for Dynamic Time Sensitive Target Detection and Interference. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X. The UAV dynamic path planning algorithm research based on Voronoi diagram. In Proceedings of the The 26th chinese control and decision conference (2014 ccdc). IEEE; 2014; pp. 1069–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Planning, P.R. On the Probabilistic Foundations of Probabilistic Roadmap Planning. Proceedings of the Robotics Research: Results of the 12th International Symposium ISRR. Springer Science and Business Media. 2007; Vol. 28, p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Four alternative patterns of the Hilbert curve. Applied mathematics and computation 2004, 147, 741–752. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrane, A.; BRAHAM, A.C.; Cherki, B. UAV path planning based on dynamic programming algorithm on photogrammetric 654 DEMs. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J.; Sukhatme, G.S. Branch and bound for informative path planning. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation. IEEE; 2012; pp. 2147–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Samir, M.; Sharafeddine, S.; Assi, C.; Nguyen, T. and Ghrayeb, A. UAV trajectory planning for data collection from time-constrained IoT devices. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2019, 19, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Babu, P.; Palomar, D.P. Majorization-minimization algorithms in signal processing, communications, and machine learning. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2016, 65, 794–816. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Que, X. and Lu, D. In Trajectory Design and Resource Allocation for UAV-Assisted Computation Offloading. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Aided Education (2024 ICISCAE), IEEE; 2024; pp. 963–967. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.; and Ajib, W. and Zhu, W. In Joint UAV Trajectory Control and Channel Assignment for UAV-Based Networks with Wireless Backhauling. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring), IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K.K.; Duong, T.Q.; Do-Duy, T.; Claussen, H.; Hanzo, L. 3D UAV trajectory and data collection optimisation via deep 666 reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2022, 70, 2358–2371. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Tang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Gu, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, M. Energy-efficient UAV-enabled data collection via wireless charging: A reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 10209–10219. [Google Scholar]

- Kurunathan, H.; Li, K.; Ni, W.; Tovar, E.; Dressler, F. Deep reinforcement learning for persistent cruise control in UAV-aided data collection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 46th Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN). IEEE; 2021; pp. 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Oubbati, O.S.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Lim, H.; Rachedi, A.; Lakas, A. Synchronizing UAV teams for timely data collection and energy transfer by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 71, 6682–6697. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.; Li, H.; Cai, W.; Zhong, Y. and Zhang, X. Phase Sensitivity-Based Fringe Angle Optimization in Telecentric Fringe Projection Profilometry. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Xu, G.; Song, Z.; Cheng, Y. and Niyato, D. Performance Analysis of Random 3D mmWave-Assisted UAV Communication System. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 73, 19169–19185. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).