Introduction

Arsenic (As) is a metalloid, and excessive accumulation of arsenic in the human body can directly lead to health problems such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even cancer. (Wang et al., 2021). The primary routes of arsenic exposure include consumption of contaminated water and foods with high arsenic levels, posing health risks to over 150 million people globally (Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2012). Inorganic arsenic is predominantly found as usually arsenate (AsV) and arsenite (AsIII) in environmental matrices such as soil and water. Industrial activities such as mining, chemical metallurgy, and the extensive application of pesticides and herbicides have exacerbated the accumulation of arsenic in these matrices, thereby elevating the potential for crop yield reductions and severe health issues (Lomax et al., 2012; Tijo Joseph et al., 2015).

Rice, a staple food for approximately 3.5 billion people worldwide, is particularly susceptible to arsenic accumulation due to the solubility and toxicity of its inorganic forms in paddy soils. Under aerobic soil conditions, arsenate (AsV) prevails, while under anaerobic conditions, such as those found in flooded paddy fields, highly bioavailable arsenite (AsIII) dominates (Abedin et al., 2002; Islam S et al., 2017). These anaerobic conditions, coupled with the unique physiological traits of rice, facilitate the efficient uptake and sequestration of arsenite, making rice a significant source of inorganic arsenic intake in humans, with levels approximately ten times higher than in other grains (Zhang et al., 2022). Arsenic enters rice predominantly through aquaporins. Research indicates that OsLsi1 is crucial for the uptake of As(III), while OsLsi2 assists in its transfer to the xylem, facilitating arsenic accumulation within the plant (Zhao et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2008). Within rice, arsenic is primarily sequestered in vacuoles, a process mediated by glutathione (GSH) and phytochelatins (PCs), with OsABCC1 playing a key role in mitigating arsenic stress by transporting As-PC complexes into vacuoles. The disruption of OsABCC1 function results in heightened arsenic sensitivity (Song et al., 2008; Song et al., 2014). Conversely, the suppression of OsPCS1 and OsPCS2 genes decreases cadmium (Cd) and arsenic content, whereas overexpression of OsWNK9 and OsPRX38 enhances arsenic tolerance in rice (Kidwai et al., 2018; Manuka et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the intricate mechanisms underlying rice’s response to arsenic stress necessitate further exploration.

The plant Fruit-Weight-like (FWL) family, characterized by a cysteine-rich PLAC8 domain, includes several proteins known for their roles in regulating grain size and metal ion homeostasis. In maize, ZmCNR1 and ZmCNR2 regulate cob size, whereas in Arabidopsis, AtPCR1 enhances cadmium tolerance (Song et al., 2004). AtPCR2, another member of this family, functions as a zinc efflux transporter, essential for maintaining zinc balance under varying environmental conditions (Song et al., 2010). In rice, some FWL genes have been implicated in grain morphology and metal transport. For example, mutations in OsFWL4 reduced cadmium transport from roots to shoots, enhancing Cd tolerance, while the roles of OsFWL3, OsFWL6, and OsFWL7 in yeast Cd tolerance and the function of OsFWL8 remain less understood (Xiong et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2020). The gene OsFWL5/OsPCR1 has been demonstrated to positively affect grain weight and zinc content, while concurrently reducing cadmium accumulation in rice (Song et al., 2015). Additionally, TGW2 has been identified as a negative regulator of grain width in rice (Ruan et al., 2020). Despite these insights, the involvement of the FWL gene family in arsenic transport and response remains to be elucidated. In this study, through bioinformatics methods, we identified genes encoding FWL in rice (Oryza sativa L.) and analyzed their evolutionary relationships, gene structures, and promoter elements. Furthermore, we identified the expression level and physiological roles of OsFWL8 in arsenic stress and tolerance through overexpression and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation. Overall, this study broadens our understanding of the FWL gene family in rice and provides foundational insights for further investigations into their functions involved in abiotic stress response.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Arsenic Treatment

Japonica rice cultivar Nipponbare (wild-type, WT) and transgenic lines harboring either overexpressed (OE-OsFWL8) or knockout (Osfwl8) vectors against the Nipponbare background were utilized. Rice seeds were germinated for two days and then exposed to 25 µM As(III) for seven days. Additionally, uniformly grown 21-day-old WT and transgenic seedlings underwent a 3-day treatment with or without 40 µM As(III)(Huang M et al., 2024).

Vector Creation and Genetic Transformation

Gene-specific primers were designed to amplify the coding sequence (CDS) of

OsFWL8 from the Nipponbare genome, which was subsequently cloned into the

pCAMBIA1300-GFP vector to create the

35S::OsFWL8::GFP construct. The

Osfwl8 mutant line was developed using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. These vectors were then introduced into Nipponbare via agrobacterium-mediated transformation to produce the transgenic lines (Chunyan Li et al., 2024). Primer sequences used for are listed in

Table S2.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from rice samples using the Plant RNA Easy Fast Kit (TIANGEN, China). After DNase I treatment, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using Hifair III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (YEASEN, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using gene-specific primers (

Table S1) with Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (No Rox) (YEASEN, China) on a BIO-RAD CFX96 Real-Time PCR system (BIO-RAD, USA). The thermal profile included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec. OsUBQ5 (

LOC_Os01g22490) served as the internal control, and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCT method (Zhao et al., 2023). Primer sequences used for RT-PCR are listed in

Table S2.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v22.0. ANOVA and Tukey’s test assessed differences between treatments or samples, considering P-values < 0.05 as statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism v10.0(Zhao et al., 2023).

Identification of the FWL Gene Family

The FWL protein signature domain Hidden Markov Model was downloaded from the Pfam database (number: PF04749). Candidate genes were identified in the complete genome protein sequence of rice (

Oryza sativa) using HMMER v3.1 software, and

FWL gene family members were finalized by comparison with the Arabidopsis FWL family (Nie F et al., 2024). Basic information on members of the

FWL gene family in rice in

Table S1.

Phylogenetic Analysis of FWL Genes

FWL proteins were aligned using MAFFT, and unconserved sites and gaps were removed with trimAL. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using iqtree, exporting the Newick Tree file. The tree was visualized and enhanced using the iTOL website.

Analysis of FWL Gene Structures

FWL gene structure was analyzed using the GFF3/GTF file of Oryza sativa, with annotation information extracted and visualized using the Gene Structure View (Advanced) tool in TBtools. Conserved motifs were predicted using the MEME suite, and conserved domains were identified using the NCBI- Conserved Domain Database (CDD) database, with results visualized in TBtools (Bailey et al., 2015).

Results

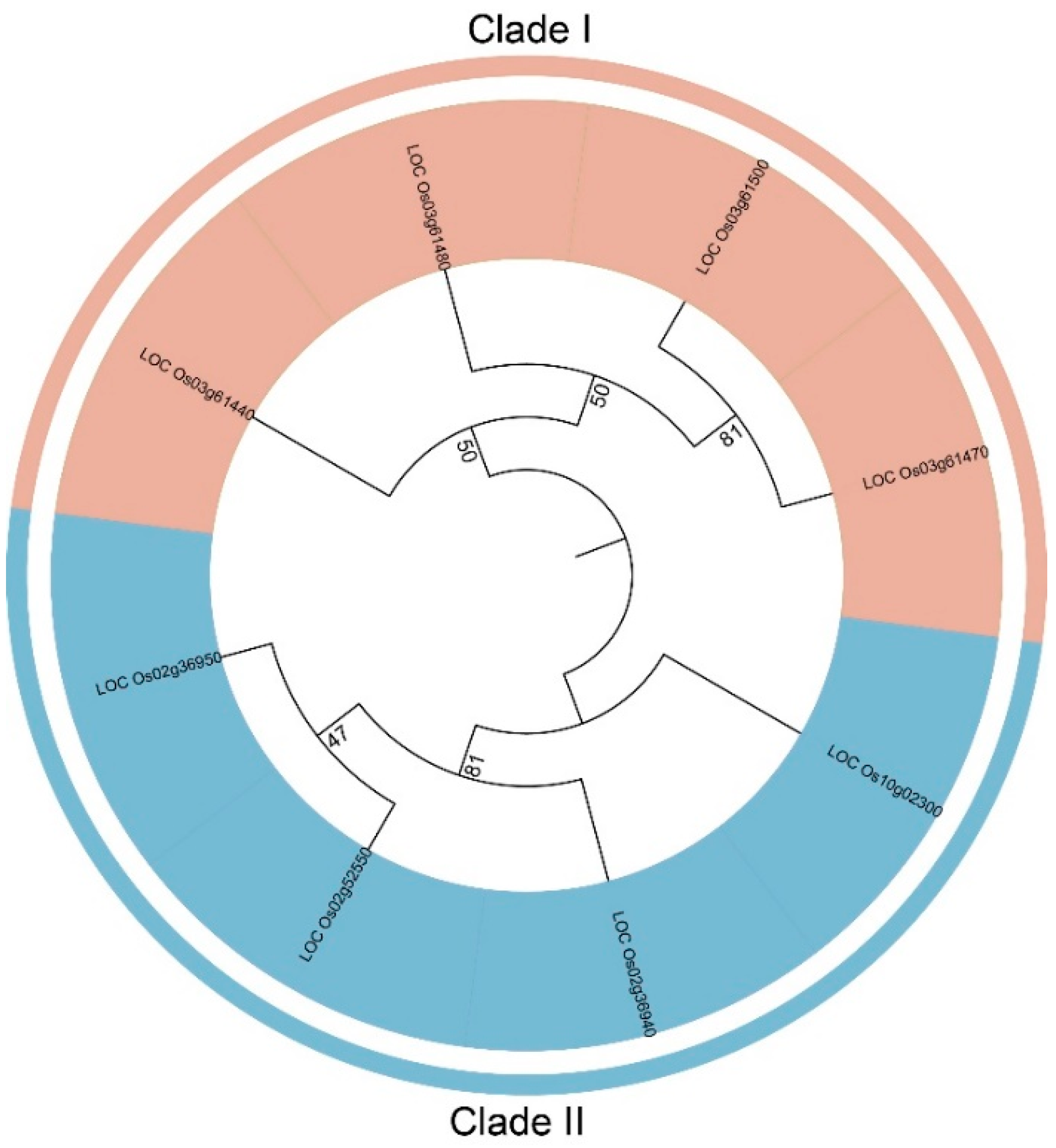

Identification and Evolutionary Analysis of FWL Genes

The Hidden Markov Model signature domain for FWL proteins was downloaded from the Pfam database (Accession: PF04749). Using HMMER v3.1 software, we searched for candidate

FWL genes in the complete genome protein sequence of

Oryza sativa and compared these with the

FWL family from

Arabidopsis thaliana (

Table S1). This analysis enabled the identification of

FWL family members in rice. To elucidate the evolutionary relationships among FWL proteins across species, we performed sequence alignments and constructed a phylogenetic tree of FWL proteins from rice (

Figure 1). Phylogenetic analysis divided the eight

FWL members from rice into two subgroups, each containing four members: Subgroup I includes

Os03g61440,

Os03g61480,

Os03g61500,

Os03g61470; Subgroup II includes

Os02g36950,

Os02g52550,

Os02g36940,

Os10g02300.

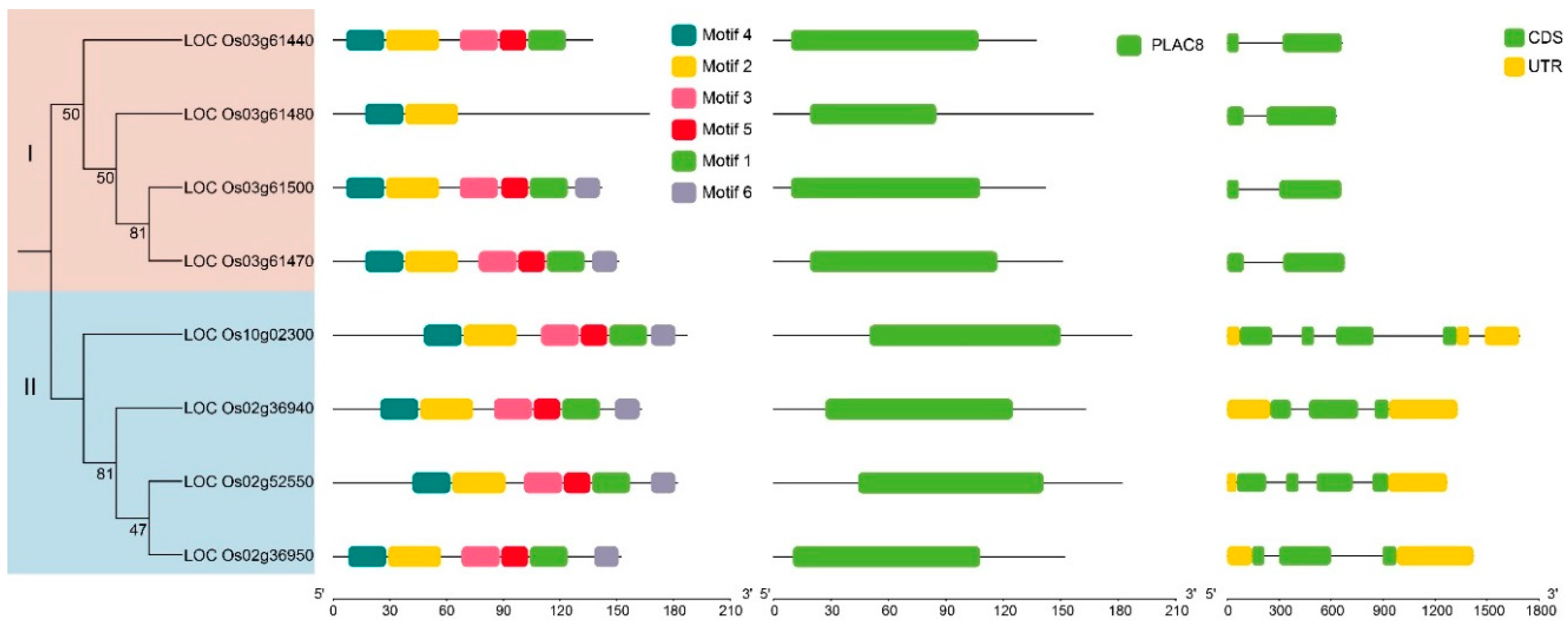

Analysis of Conserved Motifs, Domains, and Gene Structure of FWL

The gene structure and annotation details of the

FWL gene family in

Oryza sativa were analyzed with the General Feature Format version 3 (GFF3) / Gene Transfer Format (GTF) files format. The conserved motifs of FWL proteins were predicted using the MEME suite, and their domains were identified using the NCBI’s Conserved Domain Database (CDD) database (

Figure 2). Analysis revealed that

OsFWL genes contain between one and six motifs. Members of Subgroup II all possessed six motifs, whereas those in Subgroup I, such as

Os03g61440 and

Os03g61480, had only five and two motifs, respectively. Each

OsFWL gene contains 2-4 coding sequences (CDS); genes in Subgroup I have only 2 CDS while those in Subgroup II have 4 CDS. The genes in Subgroup II also have complete upstream and downstream regulatory regions (UTRs), unlike those in Subgroup I.

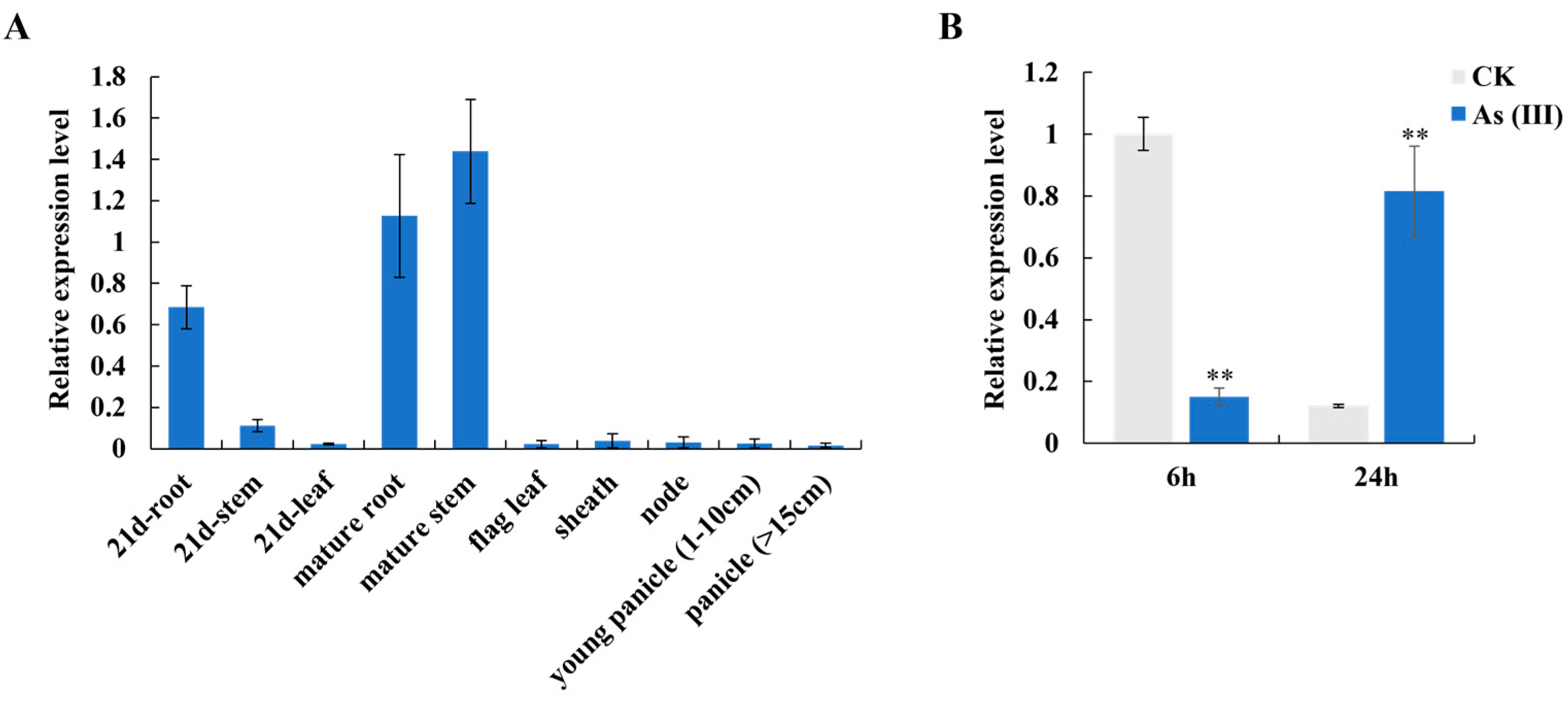

OsFWL8 as a Novel Gene in Response to Arsenic Stress in Rice

In order to investigate the function of

OsFWLs gene family in response to arsenic stress, we selected

OsFWL8, whose function has not been reported, as the object of further study. Real-time PCR analysis was employed to study the expression patterns of the

OsFWL8 gene in various rice tissues, using arsenic-tolerant japonica rice variety Nipperbare including roots, stems, leaves in the seedling stage, and roots, stems, flag leaves, leaf sheaths, nodes, young spikelets (1-10 cm), and spikes (>15 cm) at the booting stage. The expression of

OsFWL8 was predominantly observed in the roots and stems, particularly during the seedling and mature stages, where it was significantly higher compared to other tissues (

Figure 4A). To determine the response of the

OsFWL8 gene to arsenic stress, 21-day-old seedlings were transferred to a hydroponic solution containing 0 and 40 μM As(III). The expression levels of

OsFWL8 were measured after 6 and 24 hours of treatment. Results indicated that arsenic stress significantly influenced

OsFWL8 expression, which was initially suppressed at 6 hours post-treatment but significantly up-regulated with prolonged exposure, suggesting that

OsFWL8 may be involved in the regulatory pathways responding to As(III) stress (

Figure 4B).

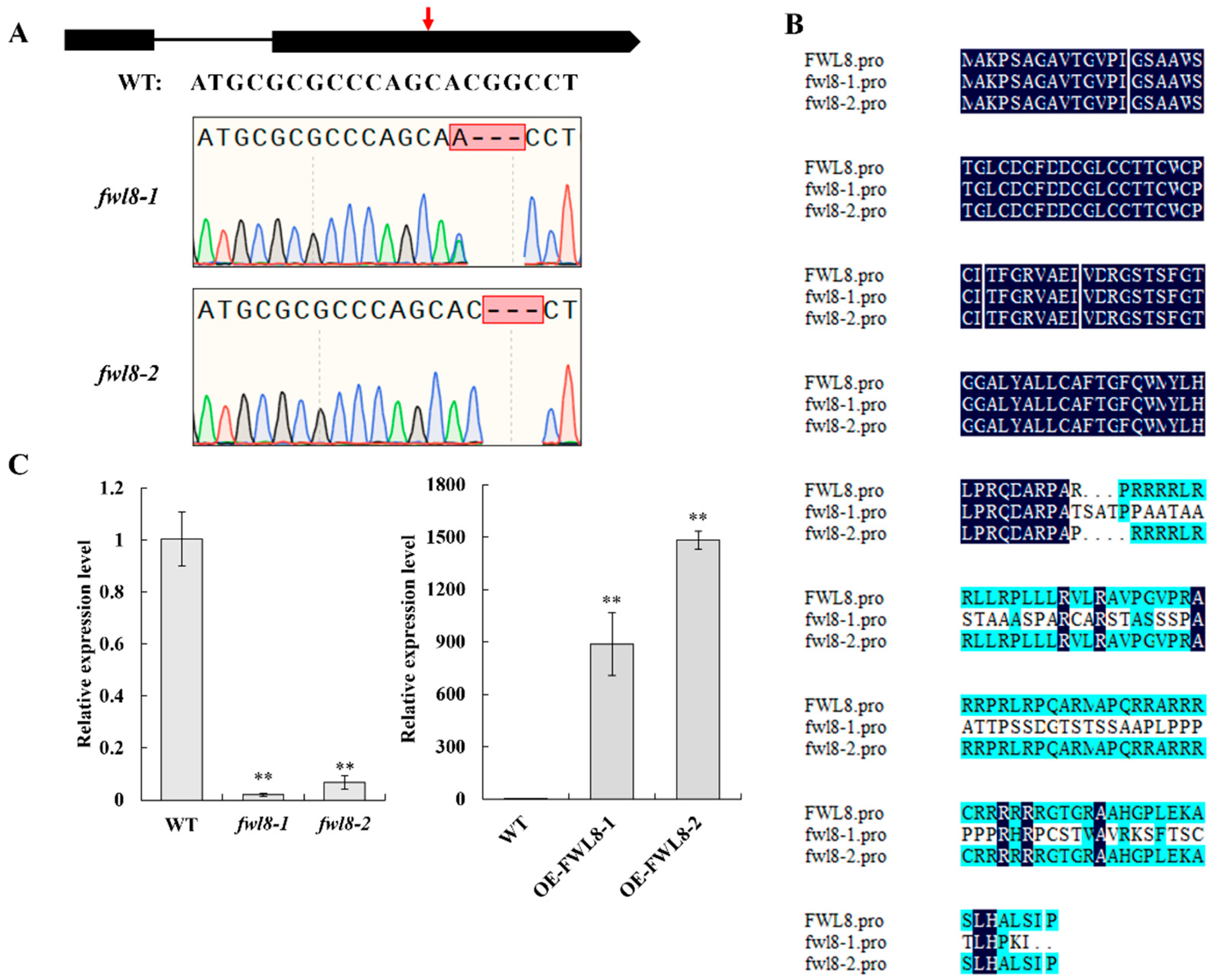

Identification of OsFWL8 Knockout and Overexpression Material

To elucidate the biological function of

OsFWL8, we employed CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. Primers targeting the exons of

OsFWL8 were designed, and gene editing was performed against the Nipponbare rice background. This resulted in the generation of two distinct homozygous

OsFWL8 knockout mutants, designated as

fwl8-1 and

fwl8-2. In

fwl8-1, a deletion of three bases and a single base substitution in the second exon resulted in a frameshift mutation, disrupting the normal protein translation sequence (

Figure 5A and B). The

fwl8-2 mutant exhibited a deletion of three bases (CGG) at the same position, leading to the omission of an arginine at the 90th amino acid position (

Figure 5A and B). Fluorescence quantification PCR revealed a significant reduction in the transcriptional levels of

OsFWL8 in both

fwl8-1 and

fwl8-2 seedlings compared to the wild type (

Figure 5C). Additionally, the

OsFWL8 coding sequence was cloned into the

pCAMBIA1300S vector, and the resulting overexpression transgenics, OE-

FWL8-1 and OE-

FWL8-2, were obtained using Nipponbare as the recipient background. Real-time PCR verification showed that

OsFWL8 expression in OE-

FWL8-1 and OE-

FWL8-2 transgenic plants was upregulated by 887-fold and 1482-fold, respectively, compared to the wild type (

Figure 5C).

Observation of Arsenic Tolerance in OsFWL8 Knockout and Overexpression Materials

To assess the impact of

OsFWL8 on arsenic tolerance in rice, 21-day-old seedlings of Nipponbare,

fwl8-2, OE-Os

FWL8-1, and OE-Os

FWL8-2 were cultivated in nutrient solutions containing 0 and 40 µM As(III) for 6 days, with each line having 12 biological replicates. Initially, new leaves in all lines exhibited inward rolling after one day, and by the second day, the leaves of Nipponbare and

fwl8-2 were partially unrolled while those of the transgenic lines remained tightly curled. After three days, the leaves of Nipponbare and

fwl8-2 returned to normal growth, whereas the old leaves of OE-

OsFWL8-1 remained curled and those of OE-

OsFWL8-2 were completely desiccated. By the sixth day, Nipponbare and

fwl8-2 showed healthy growth with only minor senescence at the leaf tips, whereas all plants in the OE-

OsFWL8-2 line were withered, and most of the OE-

OsFWL8-1 plants exhibited yellowing stems and only retained 1 to 2 new leaves (

Figure 6). Post-treatment weighing revealed that the fresh weight of Nipponbare and

fwl8-2 was reduced by only about 8% compared to controls, whereas the fresh weight of OE-

OsFWL8-1 and OE-

OsFWL8-2 decreased by approximately 30% and 56%, respectively. These results underscore the significant influence of

OsFWL8 expression levels on arsenic tolerance in rice, with overexpression rendering the rice highly susceptible to As(III), particularly in the OE-

OsFWL8-2 line. The differential response of

fwl8-2 to As(III) stress compared to Nipponbare suggests inherent tolerance in Nipponbare.

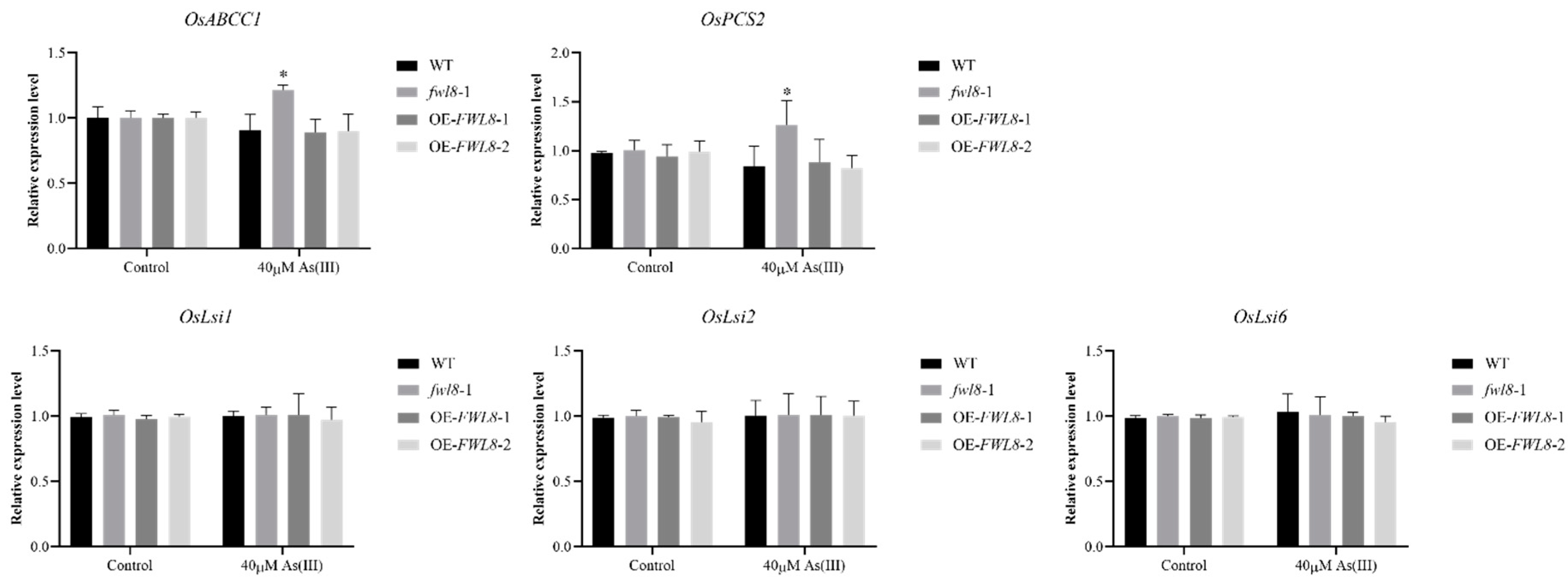

Rice will suffer from osmotic stress and excessive As transport when exposed to high As(III) concentrations. Therefore, we evaluated the relative expression levels of the key phytochelatin synthase-related gene (

OsPCS2) and arsenic transporter-related genes (

OsABCC1,

OsLsi1,

OsLsi2,

OsLsi6) in WT, OE-

OsFWL8 and

fwl8-1 seedlings under normal and arsenic treatment conditions by qRT-PCR (Guo et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024). The results showed that the expression levels of

OsABCC1 and

OsPCS2 were significant increased in mutants compared with wide type and OE-

OsFWL8 under arsenic stress, which also indicates involvement of

OsFWL8 in the arsenic response process (

Figure 7). Overall, these findings demonstrate that

OsFWL8 plays a crucial role in modulating arsenic tolerance in rice.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that the FWL gene family plays a critical role in plant growth, development, and stress resistance. However, research on the FWL gene family has predominantly focused on species other than rice, revealing significant gaps in our understanding of its functions in this important crop. For example, recent studies have shown that overexpression of the TaCNR2 gene in wheat, Arabidopsis thaliana, and rice enhances plant tolerance to cadmium (Cd), zinc (Zn), and manganese (Mn), while also reducing Cd accumulation in rice brown rice (Qiao et al., 2019). Additionally, SaPCR2 and BjPCR1 have been identified as efflux transporters involved in the tolerance to heavy metals like Cd and calcium (Ca²⁺), playing essential roles in ion homeostasis within plants (Song et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2020).

In rice, the FWL gene family consists of eight members, named OsFWL1 to OsFWL8. Most of these genes have been associated with grain weight and heavy metal transport. For instance, OsFWL1 and OsFWL3 negatively regulate grain width and weight (Xu et al., 2013; Ruan et al., 2020). OsFWL4, in particular, functions as a direct transporter, and mutations in this gene impair the transport of Cd from the roots to the shoots, thereby enhancing Cd tolerance. Other members of the FWL family, including OsFWL3, OsFWL6, and OsFWL7, have also been shown to increase yeast tolerance to Cd to varying extents, further emphasizing the potential of FWL genes in metal transport and stress tolerance (Xiong et al., 2018). OsFWL4 has recently been implicated in the negative regulation of rice yield, highlighting its potential as a valuable target for genetic manipulation to develop non-transgenic rice varieties that are both Cd-tolerant and high-yielding (Gao et al., 2020). Similarly, OsFWL5 has been identified as a key player in positively regulating grain weight, increasing Zn content in grains, and reducing Cd accumulation, thus contributing to improved grain quality (Song et al., 2015).

Despite these insights, the role of OsFWL8 in rice stress responses, particularly in relation to As tolerance, has remained unclear. Our study fills this gap by generating mutants and overexpression lines of OsFWL8 under various editing conditions. Through As(III) treatment, we found that overexpressed OsFWL8 lines were more sensitive to arsenic stress, whereas the knockout mutants exhibited enhanced tolerance. These findings suggest that OsFWL8 may play a crucial role in regulating arsenic transport and stress response in rice. Furthermore, our exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying OsFWL8-mediated arsenic transport provides new insights into the complex regulatory network of arsenic stress tolerance in rice, which could enrich our understanding of the broader arsenic transport mechanisms in plants.

In addition to its potential role in arsenic transport, the FWL gene family likely regulates grain shape and the transport of toxic metals, which could open new avenues for improving rice varieties. By manipulating OsFWL genes, it may be possible to create rice cultivars that not only exhibit increased yield but also enhanced tolerance to toxic metals like arsenic. These insights hold promise for the development of non-transgenic rice varieties that are both high-yielding and arsenic-resistant, providing a valuable resource for global food security and environmental sustainability.

Conclusion

In this study, we systematically identified and characterized eight genes encoding FWL proteins in rice, which were classified into two subgroups based on phylogenetic analysis. Each member of the FWL gene family contained 1 to 6 conserved motifs, and the promoter regions of these genes were found to harbor numerous stress-responsive elements, plant hormone-responsive elements, and growth/development-related elements. We observed that the expression of OsFWL8 was induced by As(III) treatment in 21-day-old rice seedlings, suggesting that this gene may play a role in regulating arsenic tolerance. The treatment results demonstrated that the overexpressed lines (OE-FWL8-1 and OE-FWL8-2) were more sensitive to arsenic stress compared to the wild type In contrast, the mutants exhibited enhanced tolerance to arsenic stress. These findings suggest that the FWL gene family plays a significant role in stress adaptation in rice. Overall, this study not only broadens our understanding of the FWL gene family in rice but also provides foundational insights for further investigations into their biological functions and mechanisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. Basic sequence information on members of the FWL gene family in rice and Arabidopsis; Table S2. Primer sequences used in this paper.

Author Contributions

QL and JZ conceived and designed research; MW, XFM, FN and XM performed the experiments and analyzed the data; XFM and LL contributed reagents and materials; JZ and MW completed the writing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32201697, 31972959) and Zhejiang A & F University (Grant No. 2021LFR008).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Abedin, M. J., Feldmann, J., & Meharg, A. A. (2002). Uptake kinetics of arsenic species in rice plants. Plant Physiol, 128(3), 1120-1128. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 39–49.

- Chunyan Li, Cheng Jiang, Xiangjian Pan, Yitao Qi, Wenjing Zhao, Hui Dong, Qingpo Liu, OsSAUR2, a small auxin-up RNA gene, is crucial for arsenic tolerance and accumulation in rice, Environmental and Experimental Botany, Volume 226, 2024, 105894, ISSN 0098-8472. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Li G, Sun H, Xu M, Wang H, Ji J, Wang D, Yuan C, Zhao X (2020) Targeted mutagenesis of the Rice FW 2.2-Like gene family using the CRISPR/Cas9 system reveals OsFWL4 as a regulator of tiller number and plant yield in Rice. Int J Mol Sci 21:809.

- Huang M, Liu Y, Bian Q, Zhao W, Zhao J, Liu Q. OsbHLH6, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, confers arsenic tolerance and root-to-shoot translocation in rice. Plant J. 2024;120(6):2485-2499.

- Islam, S., Rahman, M. M., Islam, M. R., & Naidu, R. (2017). Geographical variation and age-related dietary exposure to arsenic in rice from Bangladesh. Sci Total Environ, 601-602, 122-131. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T., Dubey, B., & McBean, E. A. (2015). Human health risk assessment from arsenic exposures in Bangladesh. Sci Total Environ, 527-528, 552-560. [CrossRef]

- Kidwai, M., Dhar, Y.V., Gautam, N., Tiwari, M., Ahmad, I.Z., Asif, M.H. & Chakrabarty, D. (2018) Oryza sativa class III peroxidase (OsPRX38) overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana reduces arsenic accumulation due to apoplastic lignification. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 362, 383–393. [CrossRef]

- Lomax, C., Liu, W. J., Wu, L., Xue, K., Xiong, J., Zhou, J., Zhao, F. J. (2012). Methylated arsenic species in plants originate from soil microorganisms. New Phytol, 193(3), 665-672. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Gao X, Zhao J, Zhang J, Chen S, Lu L (2020) Plant Cadmium Resistance 2 (SaPCR2) facilitates cadmium efflux in the roots of hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. Front Plant Sci 11: 568887. [CrossRef]

- Manuka, R., Saddhe, A.A., Srivastava, A.K., Kumar, K. & Penna, S. (2021) Overexpression of rice OsWNK9 promotes arsenite tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Journal of Biotechnology, 332, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Ma JF, Yamaji N, Mitani N, Xu XY, Su YH, Mcgrath SP, Zhao FJ (2008) Transporters of arsenite in rice and their role in arsenic accumulation in rice grain. PNAS 105: 9931-9935.

- Moreno-Jiménez, E., Esteban, E. & Peñalosa, J.M. (2012) The fate of arsenic in soil-plant systems. Reviews of Environmental Contamination & Toxicology, 215, 1–37.

- Nie F, Wang M, Liu L, Ma X, Zhao J. Genome-Wide Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis of the FK506 Binding Protein Family in Rice. Genes. 2024; 15(7):902. [CrossRef]

- Qiao K, Wang F, Liang S, Wang H, Hu Z, Chai T (2019) Improved Cd, Zn and Mn tolerance and reduced Cd accumulation in grains with wheat-based cell number regulator TaCNR2. Sci Rep 9: 870. [CrossRef]

- Ruan B, Shang L, Zhang B, Hu J, Wang Y, Lin H, Zhang A, Liu C, Peng Y, Zhu L, Ren D, Shen L, Dong G, Zhang G, Zeng D, Guo L, Qian Q, Gao Z (2020) Natural variation in the promoter of TGW2 determines grain width and weight in rice. New Phytol 227: 629-640.

- Song WY, Choi KS, Alexis de A, Martinoia E, Lee Y (2011) Brassica juncea plant cadmium resistance 1 protein (BjPCR1) facilitates the radial transport of calcium in the root. PNAS 108: 19808 19813. [CrossRef]

- Song WY, Choi KS, Kim DY, Geisler M, Park J, Vincenzetti V, Schellenberg M, Kim SH, Lim YP,.

- 2010; Noh EW, Lee Y, Martinoia E (2010) Arabidopsis PCR2 is a zinc exporter involved in both zinc.

- extrusion and long-distance zinc transport. Plant Cell 22: 2237-2252.

- Song WY, Lee HS, Jin SR, Ko D, Martinoia E, Lee Y, An G, Ahn SN (2015) Rice PCR1 influences grain weight and Zn accumulation in grains. Plant Cell Environ 38: 2327-2339.

- Song WY, Martinoia E, Lee J, Kim D, Kim DY, Vogt E, Shim D, Choi KS, Hwang I, Lee Y (2004) A novel family of cys-rich membrane proteins mediates cadmium resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 135: 1027-1039. [CrossRef]

- Song WY, Mendoza-Cozatl DG, Lee Y, Schroeder JI, Ahn SN, Lee HS, Wicker T, Martinoia E (2014) Phytochelatin-metal(loid) transport into vacuoles shows different substrate preferences in barley and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ 37: 1192-1201. [CrossRef]

- Song WY, Park J, Mendoza-Cozatl DG, Suter-Grotemeyer M, Shim D, Hortensteiner S, Geisler M, Weder B, Rea PA, Rentsch D, Schroeder JI, Lee Y, Martinoia E (2010) Arsenic tolerance in Arabidopsis is mediated by two ABCC-type phytochelatin transporters. PNAS 107: 21187-21192.

- Song WY, Yamaki T, Yamaji N, Ko D, Jung KH, Fujii-Kashino M, An G, Martinoia E, Lee Y, Ma JF (2014) A rice ABC transporter, OsABCC1, reduces arsenic accumulation in the grain. PNAS 111: 15699-15704. [CrossRef]

- Wang P.F., Yin N.Y., Cai X.L., Du H.L., Fu Y.Q., Geng Z.Q., Sultana S., Sun G.X., and Cui Y.S., 2021, Assessment of arsenic distribution, bioaccessibility and speciation in rice utilizing continuous extraction and in vitro digestion, Food Chemistry, 346: 128969.

- Xiong W, Wang P, Yan T, Cao B, Xu J, Liu D, Luo M (2018) The rice "fruit-weight 2.2-like" gene family member OsFWL4 is involved in the translocation of cadmium from roots to shoots. Planta 247: 1247-1260.

- Xu J, Xiong W, Cao B, Yan T, Luo T, Fan T, Luo M (2013) Molecular characterization and functional analysis of "fruit-weight 2.2-like" gene family in rice. Planta 238: 643-655.

- Yao Guo, Linlin Liu, Xinyu Shi, Peiyao Yu, Chen Zhang, and Qingpo Liu. Overexpression of the RAV Transcription Factor OsAAT1 Confers Enhanced Arsenic Tolerance by Modulating Auxin Hemostasis in Rice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2024 72 (44), 24576-24586. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Martinoia E, Lee Y (2018) Vacuolar transporters for cadmium and arsenic in plants and their applications in phytoremediation and crop development. Plant Cell Physiol 59: 1317-1325. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Nie, F.; Liu, Q. OsLPR5 Encoding Ferroxidase Positively Regulates the Tolerance to Salt Stress in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8115. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Liu J, Zheng F, et al. Comparative Analysis of Arsenic Transport and Tolerance Mechanisms: Evolution from Prokaryote to Higher Plants[J]. Cells, 2022, 11(17): 2741. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic Tree of FWLs Proteins in Rice. Using HMMER v3.1 software, candidate genes were searched for genome-wide protein sequences in rice (Oryza sativa) and the FWL gene family members were finalized by comparison with the FWL family of Arabidopsis. The tree shows two phylogenetic subfamilies (Clade I and Clade II) and color-coded.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic Tree of FWLs Proteins in Rice. Using HMMER v3.1 software, candidate genes were searched for genome-wide protein sequences in rice (Oryza sativa) and the FWL gene family members were finalized by comparison with the FWL family of Arabidopsis. The tree shows two phylogenetic subfamilies (Clade I and Clade II) and color-coded.

Figure 2.

Prediction of conservative motif (Left) and gene structure (Right) of OsFWLs Protein in Rice. The different conserved motifs predicted on the left are color-coded and positioned. The panel on the right labels the CDS region and UTR region for each gene.

Figure 2.

Prediction of conservative motif (Left) and gene structure (Right) of OsFWLs Protein in Rice. The different conserved motifs predicted on the left are color-coded and positioned. The panel on the right labels the CDS region and UTR region for each gene.

Figure 3.

Prediction of cis elements in the promoter of the OsFWL gene family in rice. Predictions were made through the analysis of potential cis-acting elements upstream of the ATG 1000 bp starting codon of the OsFWL gene translation in rice using PlantCARE. Classify and arrange all predicted cis-acting components: Abiotic and biotic stress (yellow), Phytohormone response (purple), Plant growth and development (green), Light responsive (blue). When counting the number of cis-acting elements for each category, the number of cis-acting elements for each category is marked on the right side.

Figure 3.

Prediction of cis elements in the promoter of the OsFWL gene family in rice. Predictions were made through the analysis of potential cis-acting elements upstream of the ATG 1000 bp starting codon of the OsFWL gene translation in rice using PlantCARE. Classify and arrange all predicted cis-acting components: Abiotic and biotic stress (yellow), Phytohormone response (purple), Plant growth and development (green), Light responsive (blue). When counting the number of cis-acting elements for each category, the number of cis-acting elements for each category is marked on the right side.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the expression pattern of OsFWL8 gene in rice. A. Expression of OsFWL8 in different tissues of rice; B. After treatment with 0, 40 μM As(III) for different times, changes in the expression of OsFWL8 in the roots of rice seedlings at 21 days. ** Indicates a significant difference at the P<0.01 level, each samples were subjected to three biological replicates.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the expression pattern of OsFWL8 gene in rice. A. Expression of OsFWL8 in different tissues of rice; B. After treatment with 0, 40 μM As(III) for different times, changes in the expression of OsFWL8 in the roots of rice seedlings at 21 days. ** Indicates a significant difference at the P<0.01 level, each samples were subjected to three biological replicates.

Figure 5.

OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression material identification. A. Editing sites of two OsFWL8 knockout mutants, fwl8-1 and fwl8-2, obtained using Crispr/Cas9 technology, with red arrows indicating mutation locations; B. Amino acid sequence alignment of OsFWL8 in wide type, fwl8-1 and fwl8-2; C. Real-time PCR was used to detect the expression levels of OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression material.

Figure 5.

OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression material identification. A. Editing sites of two OsFWL8 knockout mutants, fwl8-1 and fwl8-2, obtained using Crispr/Cas9 technology, with red arrows indicating mutation locations; B. Amino acid sequence alignment of OsFWL8 in wide type, fwl8-1 and fwl8-2; C. Real-time PCR was used to detect the expression levels of OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression material.

Figure 6.

Analysis of arsenic tolerance phenotype in OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression seedlings. The above picture is a phenotypic photograph of the treatment (Bar=10 cm), and the bottom picture is the statistical results of root length, shoot height and fresh weight of each plant. ** Indicates a significant difference at the P<0.01 level, each Samples were subjected to twelve biological replicates.

Figure 6.

Analysis of arsenic tolerance phenotype in OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression seedlings. The above picture is a phenotypic photograph of the treatment (Bar=10 cm), and the bottom picture is the statistical results of root length, shoot height and fresh weight of each plant. ** Indicates a significant difference at the P<0.01 level, each Samples were subjected to twelve biological replicates.

Figure 7.

Expression analysis of genes related to arsenic stress tolerance and arsenic transport in wide type, OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression seedlings with or without arsenic treatment. Each sample was subjected to three biological replicates. * Indicates a significant difference at the P<0.05 level, each Samples were subjected to three biological replicates.

Figure 7.

Expression analysis of genes related to arsenic stress tolerance and arsenic transport in wide type, OsFWL8 knockout and overexpression seedlings with or without arsenic treatment. Each sample was subjected to three biological replicates. * Indicates a significant difference at the P<0.05 level, each Samples were subjected to three biological replicates.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).