Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Physicochemical Analysis of CsANNs

2.2. Sequences Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis of ANNs

2.3. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structure of CsANNs

2.4. Chromosomal Location and Collinearity Analysis of CsANNs

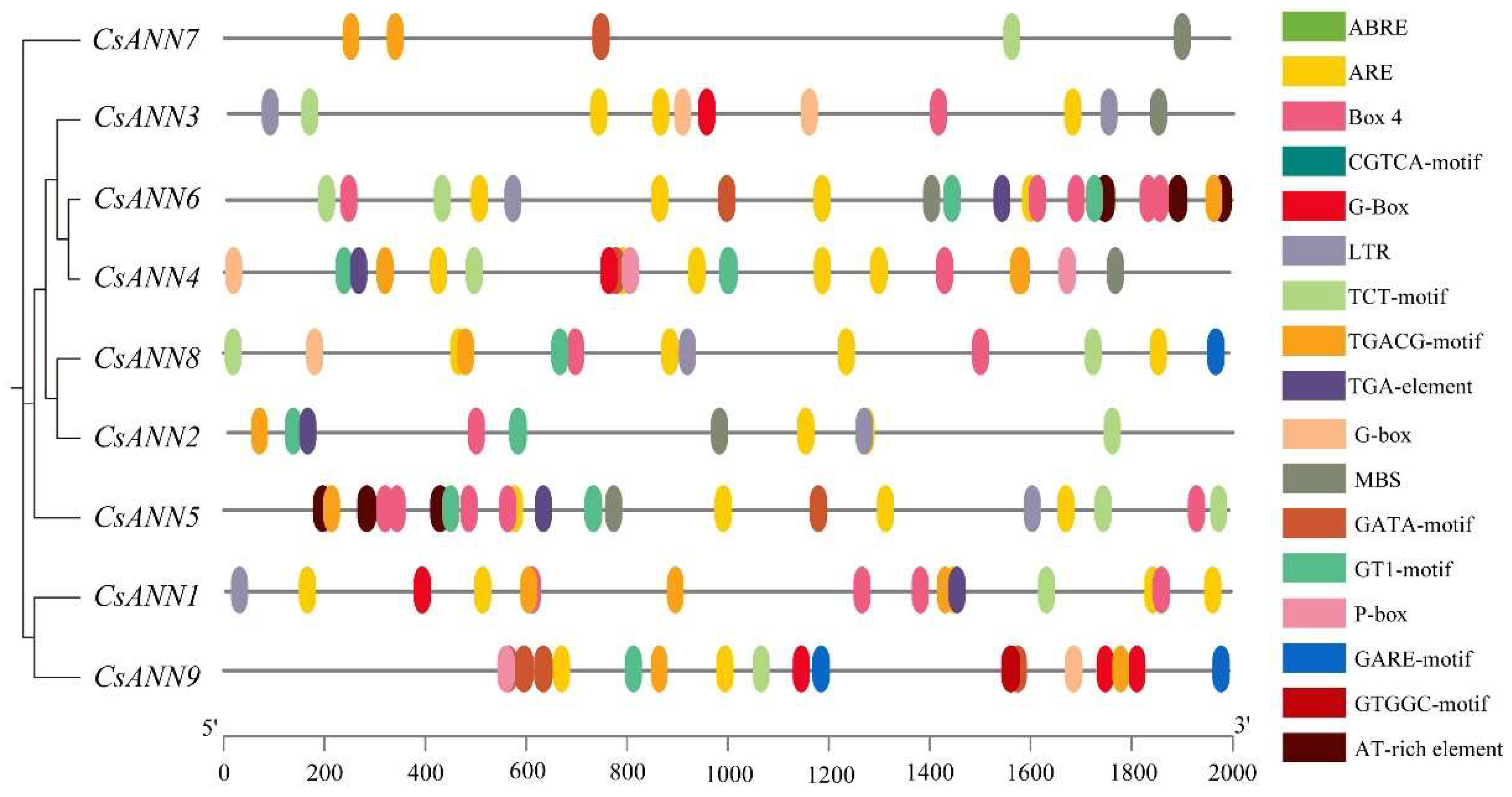

2.5. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in CsANN Promoters

2.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Profile of CsANNs

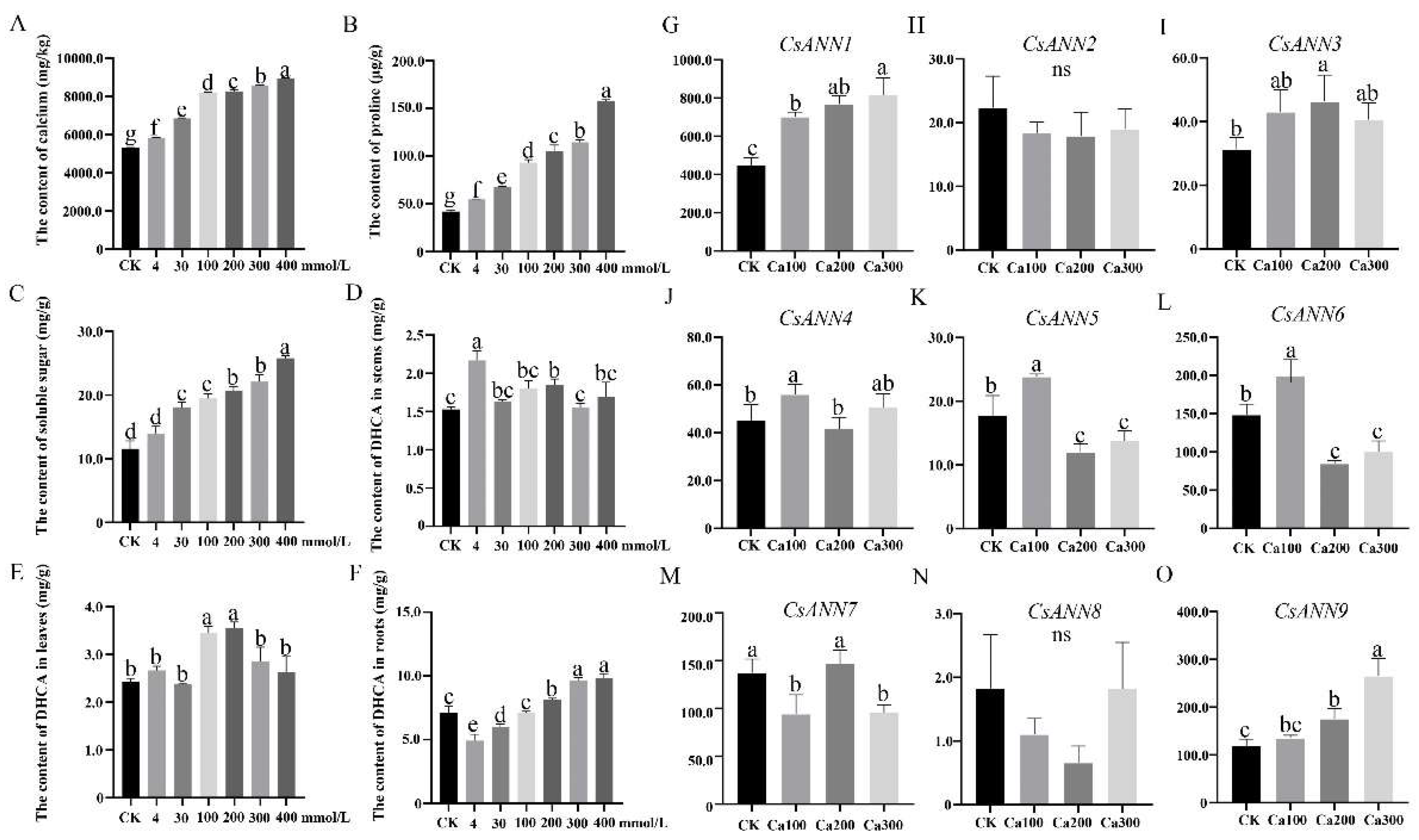

2.7. The Effects of Exogenous CaCl2 Treatments on C. saxicola Seedlings

2.8. CsANNs Correlated with DHCA Biosynthesis

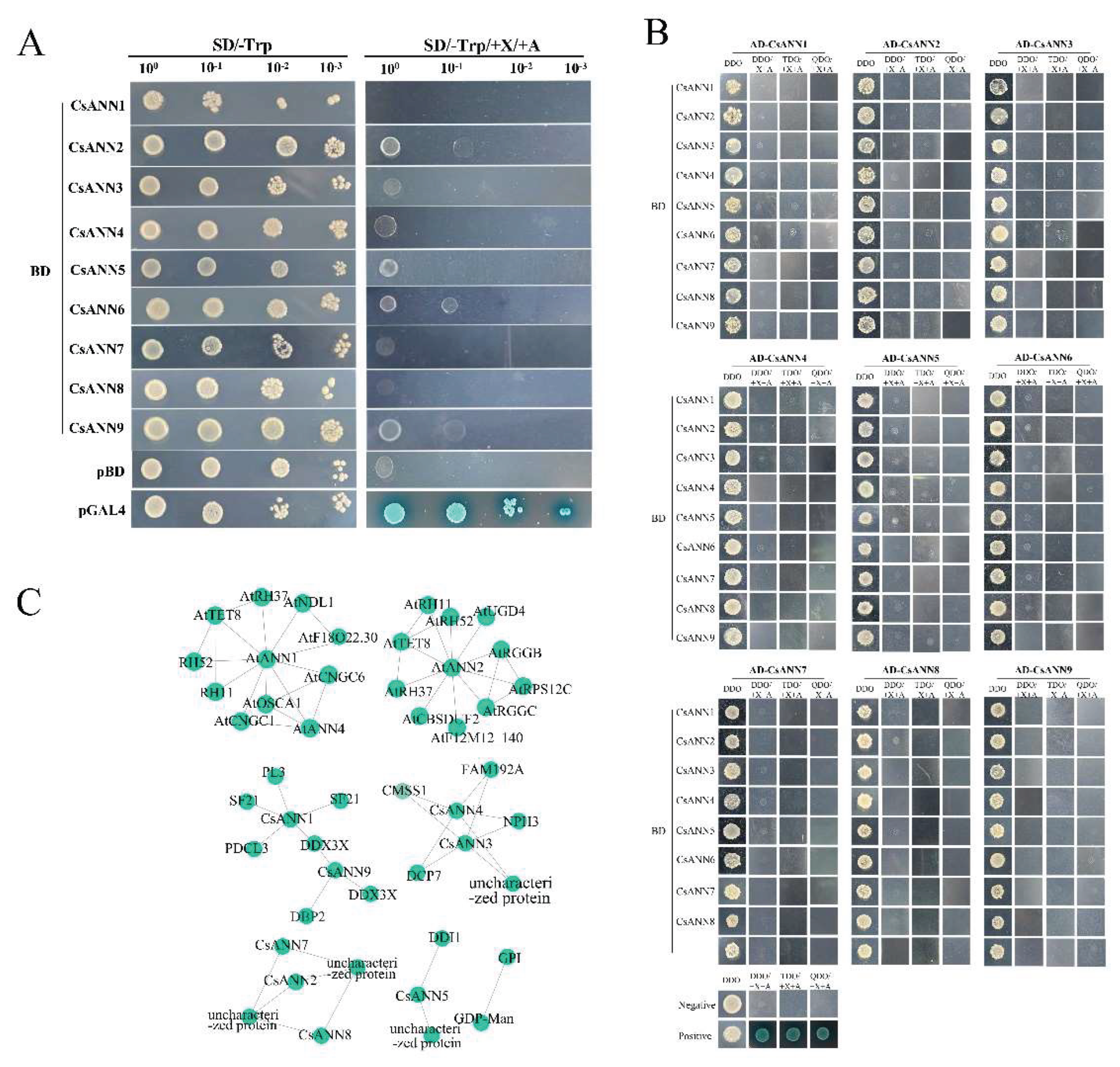

2.9. Yeast Two Hybrid Assay and Protein Interaction Networks of the CsANNs

3. Discussion

3.1. The Structure of CsANNs Were Conserved

3.2. CsANNs were Involved in the Biosynthesis of DHCA

3.3. CsANNs Might Play an Important Role in the Adaptability of C. saxicola to Karst Environment

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.2. Genome-Wide Identification of the CsANN Genes

4.3. Phylogenetic Relationship, Conserved Motif, and Gene Structure Analysis

4.4. Chromosomal Location, Collinearity, and Gene Duplication Analysis

4.5. Cis-Acting Elements, and Protein-Protein Interaction Analysis

4.6. Measurement of the BIAs Contents

4.7. CsANN Cloning

4.8. qRT-PCR Analysis

4.9. Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

4.10. Transient Overexpression of CsANN1 and CsANN9 in C. saxicola Leaves

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, G.; Lin, Z.; Bo, C.; Jia, Y.; Jiang, B.; Qi, Y.; Jun, L. The Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacology, Toxicity, and Applications of Corydalis Saxicola Bunting: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 822792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chao, T.; Hua, Z.; Jin, W.; Fang, W.; Yi, Y.M.; Xi, L.; Hong, Z.; Chun, Y.; Bang, C.; et al. Investigation of the Hepato-protective Effect of Corydalis Saxicola Bunting on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats by 1H-NMR-Based Metabonomics and Network Pharmacology Approaches. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 159, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yao, C.; Fan, W.; Shao, T.; Yi, F. Corydalis Saxicola Bunting: A Review of Its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhen, L.; Xiao, W.; Dan, H.; Sui, Z.; Min, L.; De, Y.; Dong, W.; Yi, W. Anti-Hepatitis B Virus Effects of Dehydrocheilanthifoline from Corydalis Saxicola. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2013, 41, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sun, N.L.; Zhang, W.D.; Li, H.L.; Lu, G.C.; Yuan, B.J.; Jiang, H.; She, J.H.; Zhang, C. Protective Effects of Dehy-drocavidine on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Acute Hepatotoxicity in Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, H.; Qin, M.; Tan, Y.J.; Ou, X.L.; Chen, X.Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.J.; Lei, M. RNA Editing Events and Expression Profiles of Mitochondrial Protein-Coding Genes in the Endemic and Endangered Medicinal Plant, Corydalis Saxicola. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1332460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Duan, Y.; Xie, H.T.; Tian, J. Challenges in Research and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicines. Institute of Pharmaceutical Research. Nanjing, China, 2007: 7102–8.

- Hui, L.; Wei, Z.; Chuan, Z.; Ting, H.; Run, L.; Jiang, H.; Hai, C. Comparative Analysis of the Chemical Profile of Wild and Cultivated Populations of Corydalis Saxicola by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Phytochem. Anal. 2007, 18, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Yan, W.; Yu, B.; Yan, R.; Xiao, X.; Fu, Z.; Hai, D. A Critical Review on Plant Annexin: Structure, Function, and Mechanism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 190, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, G.; Carl, C.; Stephen, M. Annexins: Linking Ca; Signalling to Membrane Dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, M.J.; Anuphon, L.; Neil, M.; Alex, W.; Colin, B.; H, B.N.; M, D.J. Annexins: Multifunctional Components of Growth and Adaptation. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna, P.; Aneta, K.; Ruud, D.; Marcin, G.; Michael, K.; Jean, L.; Slawomir, P.; René, B. A Putative Consensus Sequence for the Nucleotide-Binding Site of Annexin A6. Biochemistry. 2003, 42, 9137–9146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaela, T.; Hendrik, R.; Miroslav, O.; Nicola, M.; Miroslava, H.; Petr, D.; Jozef, Š.; Olga, Š. Advanced Microscopy Reveals Complex Developmental and Subcellular Localization Patterns of ANNEXIN 1 in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, G.; E, M.S. Annexins: From Structure to Function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 331–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, H.; J, P.; A, D.; R, S.; R, H. Annexin 24 from Capsicum Annuum X-Ray Structure and Biochemical Characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 8072–8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorota, P.; Greg, C.; Grazyna, G.; Janusz, D.; Krzysztof, F.; Araceli, C.; Bartlomiej, F.; Stanley, R.; Jacek, H. The Role of Annexin 1 in Drought Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1394–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, C.G.; A, S.; J, E.D.; J, R.S. Differential Expression of Members of the Annexin Multigene Family in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, W.; Ali, M.; Guo, L.; Yi, L.; Shi, L.; Chun, Y.; Yan, C.; Fei, Z.; Jian, Z. Genome-Wide Characterization and Abiotic Stresses Expression Analysis of Annexin Family Genes in Poplar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Qian, Z.; Ming, Z.; En, Z.; Yi, T.; Xue, Z.; Ji, S.; Yan, W. Induction of Annexin by Heavy Metals and Jasmonic Acid in Zea Mays. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2013, 13, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Ahmed, I.; Kirti, P.B. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Profiling of Annexins in Brassica Rapa and Their Phylogenetic Sequence Comparison with B. Juncea and A. Thaliana Annexins. Plant Gene 2015, 4, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jia, Y.; Liang, X.; Xiao, S.; Ji, W.; Yan, W.; Yi, M.; Yue, Z.; Li, L. Characterization of Annexin Gene Family and Func-tional Analysis of RsANN1a Involved in Heat Tolerance in Radish (Raphanus Sativus L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.S.; B, C.G.; T, A.B.; J, R.S.; B, K.P. Identification and Characterization of Annexin Gene Family in Rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.M.; Wei, X.K.; Liao, W.X.; Huang, L.H.; Zhang, H.; Liang, S.C.; Peng, H. Molecular Analysis of the Annexin Gene Family in Soybean. Biol. plant. 2013, 57, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, Y.; Pat, H.; Venkatesan, S. Analysis of the Female Gametophyte Transcriptome of Arabidopsis by Comparative Expression Profiling. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1853–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, A.; Barthakur, S.; Bushart, T.; Chou, S.; Morgan, R.; Fernandez, M.; Clark, G.; Roux, S. Expression Profiling of the Arabidopsis Annexin Gene Family during Germination, de-etiolation and Abiotic Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. (Issy-les-Moulineaux, Fr.) 2006, 44, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Guy, B.; Heidi, N.; Jeppe, E.; L, N.K.; Malene, J.; G, W.K. Patatins, Kunitz Protease Inhibitors and Other Major Proteins in Tuber of Potato Cv. Kuras. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 3569–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D, S.; N, R.; J, D.A.; J, J. Sulfolipid Is a Potential Candidate for Annexin Binding to the Outer Surface of Chloroplast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 272, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, G.; Kristin, K.; Anna, K.; Anja, B.; Julia, K. Towards the Proteome of Brassica Napus Phloem Sap. Proteomics 2006, 6, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tang, X.; Qin, Y.; He, Q.; Yi, Y.; Ji, Z. Karst Rocky Desertification Progress: Soil Calcium as a Possible Driving Force. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 649, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, L.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Zhi, R.; Feng, H.; Xin, T.; Zhi, X.; Fang, D.; Zuo, Y.; Guang, L.; et al. Genomic Mechanisms of Physiological and Morphological Adaptations of Limestone Langurs to Karst Habitats. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Hao, C.; Yi, Z.; Hannah, T.; Margaret, F.; Ye, H.; Rui, X. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magali, L.; Patrice, D.; Gert, T.; Kathleen, M.; Yves, M.; Peer, V.; Pierre, R.; Stephane, R. PlantCARE, a Database of Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements and a Portal to Tools for in Silico Analysis of Promoter Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Ren, F.; Gao, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, T.; Ma, X.; Pu, X.; Xin, T.; et al. The Genome of Corydalis Reveals the Evolution of Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Ranunculales. Plant J. 2022, 111, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Casadó, V.; Devi, L.A.; Filizola, M.; Jockers, R.; Lohse, M.J.; Milligan, G.; Pin, P.; Guitart, X. G Protein–Coupled Re-ceptor Oligomerization Revisited: Functional and Pharmacological Perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaux, M.; Séjalon, N.; Bécard, G.; Ané, M. Evolution of the Plant-Microbe Symbiotic “Toolkit”. Trends Plant Sci 2013, 18, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, K.; Clark, B.; Ayele, T.; Ashe, P.; Kirti, B. Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis of Annexin Superfamily in Plants. PLoS One 2012, 7, e47801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C, M.J.; M, C.K.; Anuphon, L.; M, D.J. Heme-Independent Soluble and Membrane-Associated Peroxidase Activity of a Zea Mays Annexin Preparation. Plant signaling behave. 2009, 4, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, G.K.; Dorota, K.; Jacek, H.; Rene, B.; Slawomir, P. Peroxidase Activity of Annexin 1 from Arabidopsis Thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 336, 868–875. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, H.; Li, L.; Sai, X.; Min, Y.; Pan, X.; Wei, L.; Yu, K.; Lu, H.; Mei, W.; Lun, Q.; et al. Comprehensive Analyses of the Annexin (ANN) Gene Family in Brassica Rapa, Brassica Oleracea and Brassica Napus Reveals Their Roles in Stress Response. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4295. [Google Scholar]

- Raina, I.; Javeria, E.; Sheng, G.; Teng, L.; Muhammad, I.; Zhi, Y.; Taotao, W. Overexpression of Annexin Gene AnnSp2, Enhances Drought and Salt Tolerance through Modulation of ABA Synthesis and Scavenging ROS in Tomato. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12087. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Shufen, L.; Shu, Y.; Like, W.; Wang, G. Retraction Note to: Overexpression of a Cotton Annexin Gene, GhAnn1, Enhances Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Cotton. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 98, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, D.; Hayashi, A.; Temi, Y.; Kan, N.; Tsuchiya, T. Biochemical and Immunohistochemical Characterization of Mimosa Annexin. Planta 2004, 219, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, C.; Wasserman, M. Isolation and Identification of Actin-Binding Proteins in Plasmodium Falciparum by Affinity Chromatography. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2000, 95, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, C.M.; Gant, S.J.; Bowles, D.J. Tomato Annexins P34 and P35 Bind to F-Actin and Display Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase Activity inhibited by Phospholipid Binding. Plant cell 1996, 8, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nien, H.; Mohd, Y.A.; An, W.; Asiah, O.; K, R.A.; Andreas, H. The Crystal Structure of Calcium-Bound Annexin Gh1 from Gossypium Hirsutum and Its Implications for Membrane Binding Mechanisms of Plant Annexins. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 18314–18322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Xuan, J.; Like, W.; Shu, L.; Shuang, W.; Chao, C.; Tian, Z.; Wang, G. A Cotton Annexin Affects Fiber Elongation and Secondary Cell Wall Biosynthesis Associated with Ca2+ Influx, ROS Homeostasis, and Actin Filament Reorganization. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1750–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, X.; Shen, M.; Feng, R.; Wei, Q. The Evolution, Variation and Expression Patterns of the Annexin Gene Family in the Maize Pan-Genome. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, K.; Xi, X.; Du, X.; Zou, X.; Ma, Y.; Song, Y.; Luo, C.; Wei, S. The Evolution, Expression Patterns, and Domes-tication Selection Analysis of the Annexin Gene Family in the Barley Pan-Genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A. The Alternative Genome. Sci. Am. 2005, 292, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Barmak, M.; Christopher, L. A Genomic View of Alternative Splicing. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffares, D.C.; Penkett, J.; Bähler, J. Rapidly Regulated Genes Are Intron Poor. Trends Genet. 2008, 24, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, R.S.; Walter, G. The Evolution of Spliceosomal Introns: Patterns, Puzzles and Progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranhão, C.; Pereira, G.; Collier, L.S.; Anjos, L.H.C.; Azevedo, A.C.; Souza, R. Pedogenesis in a Karst Environment in the Cerrado Biome, Northern Brazil. Geoderma 2020, 365, 114169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, G.M.; Lynch, V.J.; Kostman, T.A.; Goss, L.J.; Franceschi, V.R. The Role of Druse and Raphide Calcium Oxalate Crystals in Tissue Calcium Regulation in Pistia stratiotes Leaves. Plant Biol. (Berlin, Ger.) 2002, 4, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilarslan, H. Calcium Oxalate Crystals in Developing Seeds of Soybean. Ann. Bot. (Oxford, U. K.) 2001, 88, 243–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Deng, X.; Xiang, W. Calcium content and high calcium adaptation of plants in karst areas of southwestern Hunan, China. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 2991–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musetti, R.; Favali, M. Cytochemical localization of calcium and X-ray microanalysis of Catharanthus roseus L. infected with phytoplasmas. Micron 2003, 34, 387–393 [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanger, B.C. The movement of calcium in plants. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1979, 10, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poovaiah, B.W.; Reddy, A.S.N.; Leopold, A.C. Calcium messenger system in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1987, 6, 47–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhang, H. Marsdenia tenacissima genome reveals calcium adaptation and tenacissoside biosynthesis. Plant J. 2022, 113, 1146–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Effects of Rocky Desertification Stress on Oat (Avena sativa L.) Seed Germination and Seedling Growth in the Karst Areas of Southwest China. Plants 2024, 13, 3260–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, L.; Xuan, X.; Lu, G.; Jia, Z.; Chao, G.; Zhi, W.; Hong, L.; Xing, L.; Xiao, Y.; Na, Z.; et al. CsbZIP50 Binds to the G-Box/ABRE Motif in CsRD29A Promoter to Enhance Drought Tolerance in Cucumber. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Wen, D.; Tang, C.; Lai, S.; Yan, Y.; Du, C.; Zhang, Z. The Transcriptional Regulation of Arabidopsis ECT8 by ABA-Responsive Element Binding Transcription Factors in Response to ABA and Abiotic Stresses. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2025, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, H.; Wang, K.; Tang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Si, H. MYB Transcription Factors: Acting as Molecular Switches to Regulate Different Signaling Pathways to Modulate Plant Responses to Drought Stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Song, Q.; Miao, M.; Fan, T.; Tang, X. The 1R-MYB Transcription Factor SlMYB1L Modulates Drought Tol-erance via an ABA-Dependent Pathway in Tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 222, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, H. The bZIP transcription factor ATF1 regulates blue light and oxidative stress responses in Trichoderma guizhouense. mLife 2023, 2, 365–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Liu, L. The bZIP transcription factor PfZipA regulates secondary metabolism and oxidative stress response in the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis fici. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 81, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zha, W.; Liang, L.; Faso, O.E.; Wu, L.; Wang, S. The bZIP Transcription Factor AflRsmA Regulates Aflatoxin B1 Biosynthesis, Oxidative Stress Response and Sclerotium Formation in Aspergillus flavus. Toxins 2020, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, G.; N, F.; E, G.; E, M.; G, P.M. The ACA4 Gene of Arabidopsis Encodes a Vacuolar Membrane Calcium Pump That Improves Salt Tolerance in Yeast. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 1814–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yahaya, S.; Li, J.; Wu, F. Enigmatic Role of Auxin Response Factors in Plant Growth and Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1398818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Stéphanie, S.; Aurore, C. A downstream mediator in the growth repression limb of the jasmonate pathway. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2470–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazuko, Y.S.; Kazuo, S. Organization of Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements in Osmotic- and Cold-Stress-Responsive Promoters. Trends Plant. Sci. 2005, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, S.; C, S.; J, C.E. Gene Hunting with Hidden Markov Model Knockoffs. Biometrika 2019, 106, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorna, R.; Neil, R.; Gustavo, S.; Alexandre, A.; David, H.; Gregory, D.; Granger, S.; Robert, F. Genome Properties in 2019: A New Companion Database to InterPro for the Inference of Complete Functional Attributes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D564–D572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séverine, D.; Chiara, G.; Frédérique, L.; Heinz, S.; Vassilios, I.; Christine, D. Expasy, the Swiss Bioinformatics Resource Portal, as Designed by Its Users. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W216–W227. [Google Scholar]

- Ivica, L.; Leo, G.; J, D.N.; Tobias, D.; Joerg, S.; Richard, M.; Francesca, C.; R, C.R.; P, P.C.; Peer, B. Recent Improvements to the SMART Domain-Based Sequence Annotation Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.; Hong, S. Cell-PLoc: A Package of Web Servers for Predicting Subcellular Localization of Proteins in Various Organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.; Hong, S. Euk-mPLoc: A Fusion Classifier for Large-Scale Eukaryotic Protein Subcellular Location Prediction by Incorporating Multiple Sites. J. Proteome Res. 2007, 6, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, W.; Jim, P.; David, M.; Geoffrey, B. Jalview: Visualization and Analysis of Molecular Sequences, Alignments, and Structures. BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6, P28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Nastou, K.; Koutrouli, M.; Kirsch, R.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Hu, D.; Peluso, M.E.; Huang, Q.; Fang, T.; et al. The STRING Database in 2025: Protein Networks with Directionality of Regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- David, O.; John, M.; Jorge, B.; Alexander, P.; Barry, D. Cytoscape Automation: Empowering Workflow-Based Network Analysis. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Niu, S.; Lin, J.; Yang, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhuang, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of TCP Transcription Factors Responding to Multiple Stresses in Arachis Hypogaea L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Mu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, X.; Wilson, I.W.; Qi, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Mining of CULLIN E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Genes from Uncaria Rhynchophylla. Plants 2024, 13, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Lv, M.; Zeng, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liang, X.F. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization of the ORA (Olfactory Receptor Class A) Gene Family, and Potential Roles in Bile Acid and Pheromone Recognition in Mandarin Fish (Siniperca Chuatsi). Cells 2025, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Ya, W.; Xu, L.; Hui, P.; Dian, J.; Jia, W.; Can, J.; Kumar, S.S.; Jian, S.; Xin, L.; et al. An Integrated Multi-Omics Approach Reveals Polymethoxylated Flavonoid Biosynthesis in Citrus Reticulata cv. Chachiensis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).