Submitted:

13 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

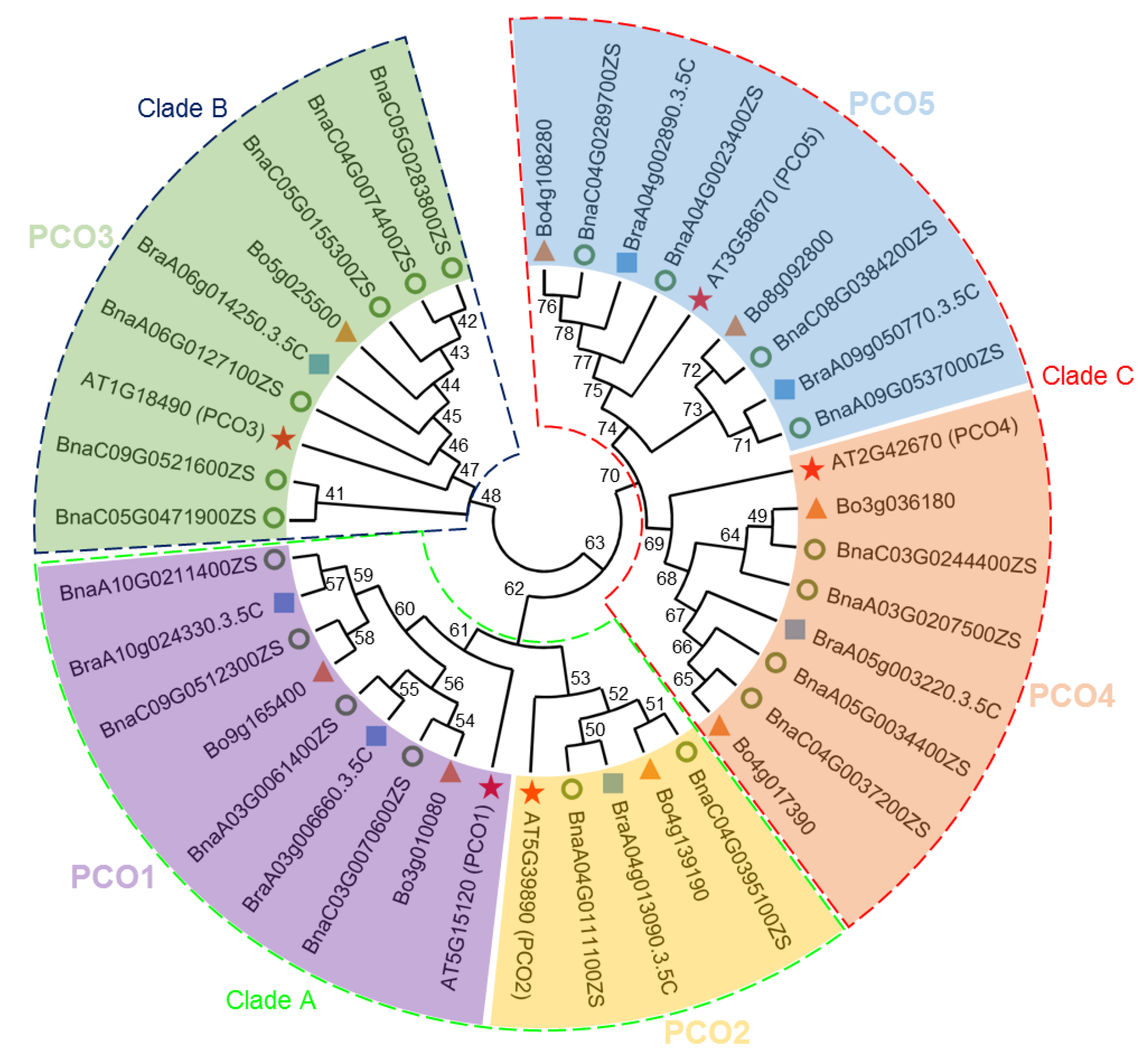

2.1. Identification and Classification of PCO Genes in B. napus, B. oleracea and B. rapa

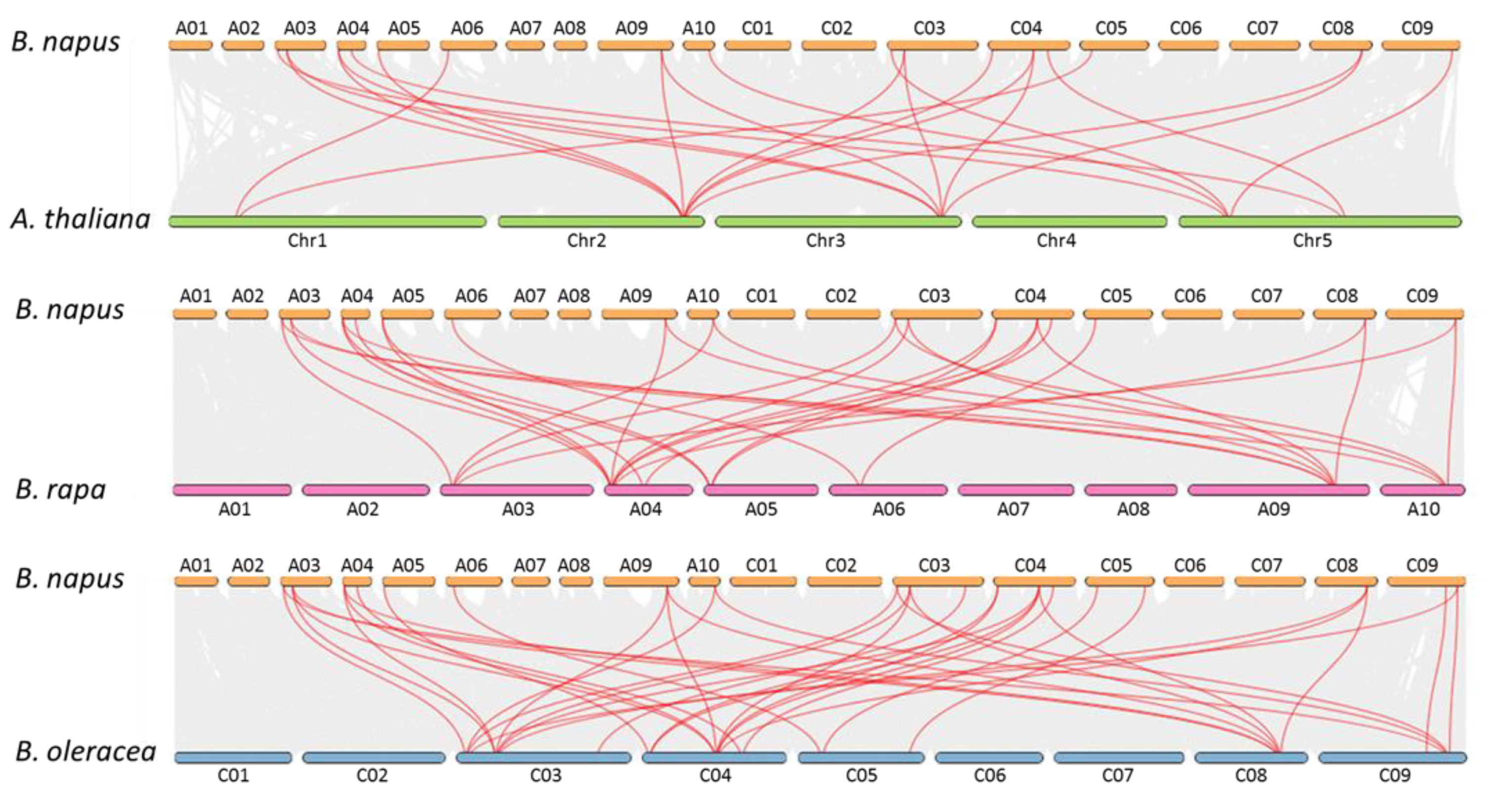

2.2. Chromosomal Distribution and Duplication of BnaPCOs

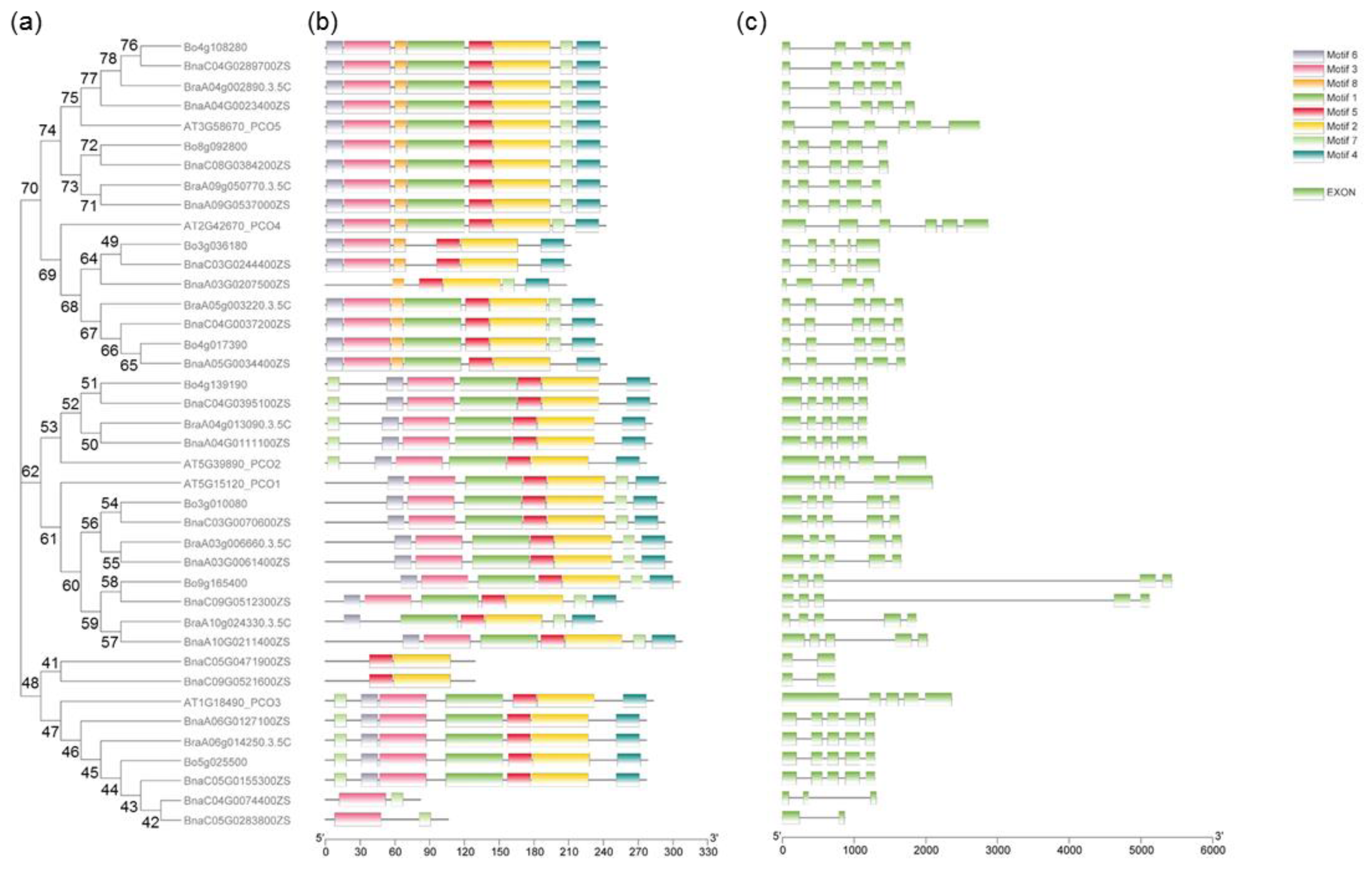

2.3. Gene Structures and Motif Analysis of PCOs in B. napus

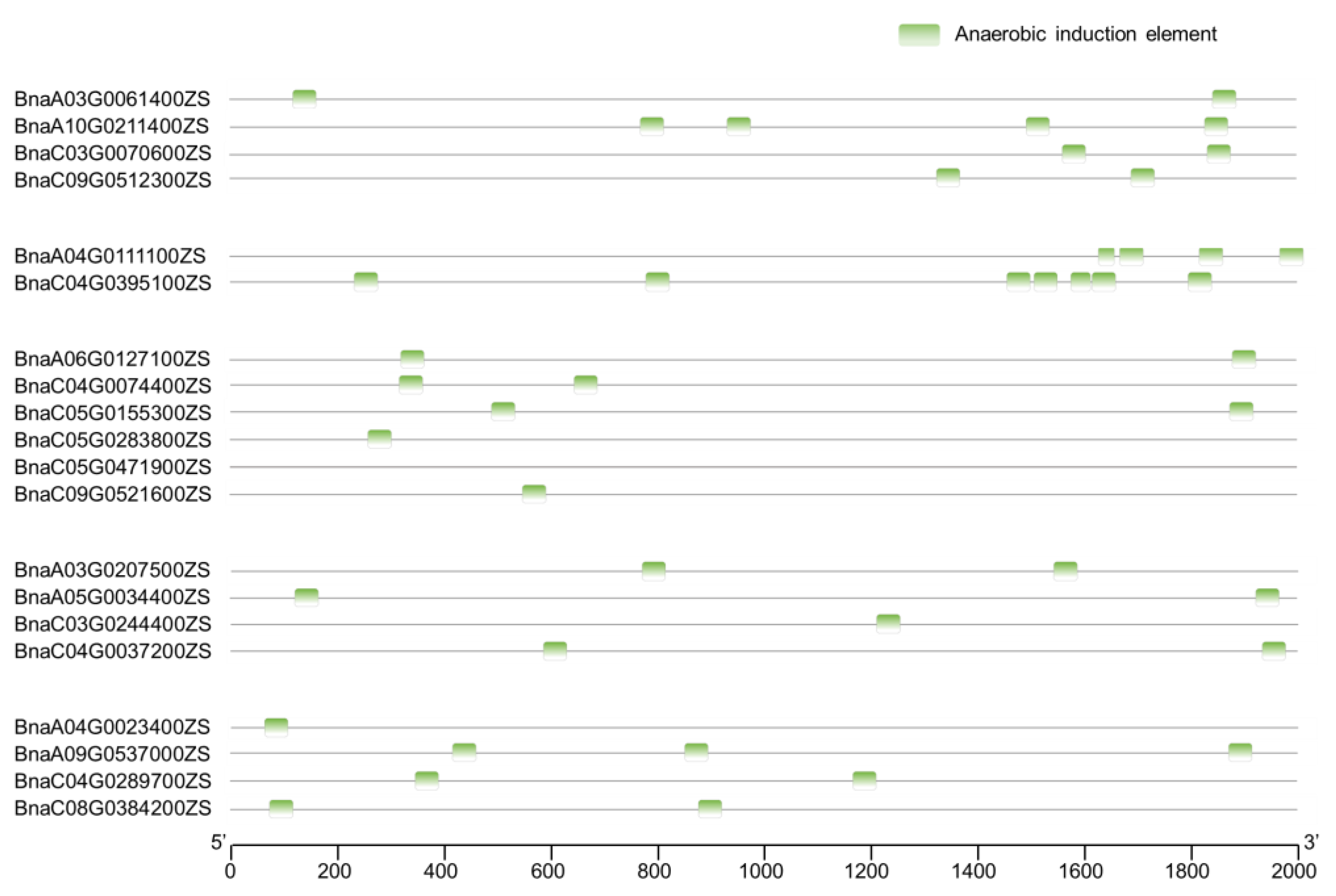

2.4. Cis-Element Analysis of BnaPCOs

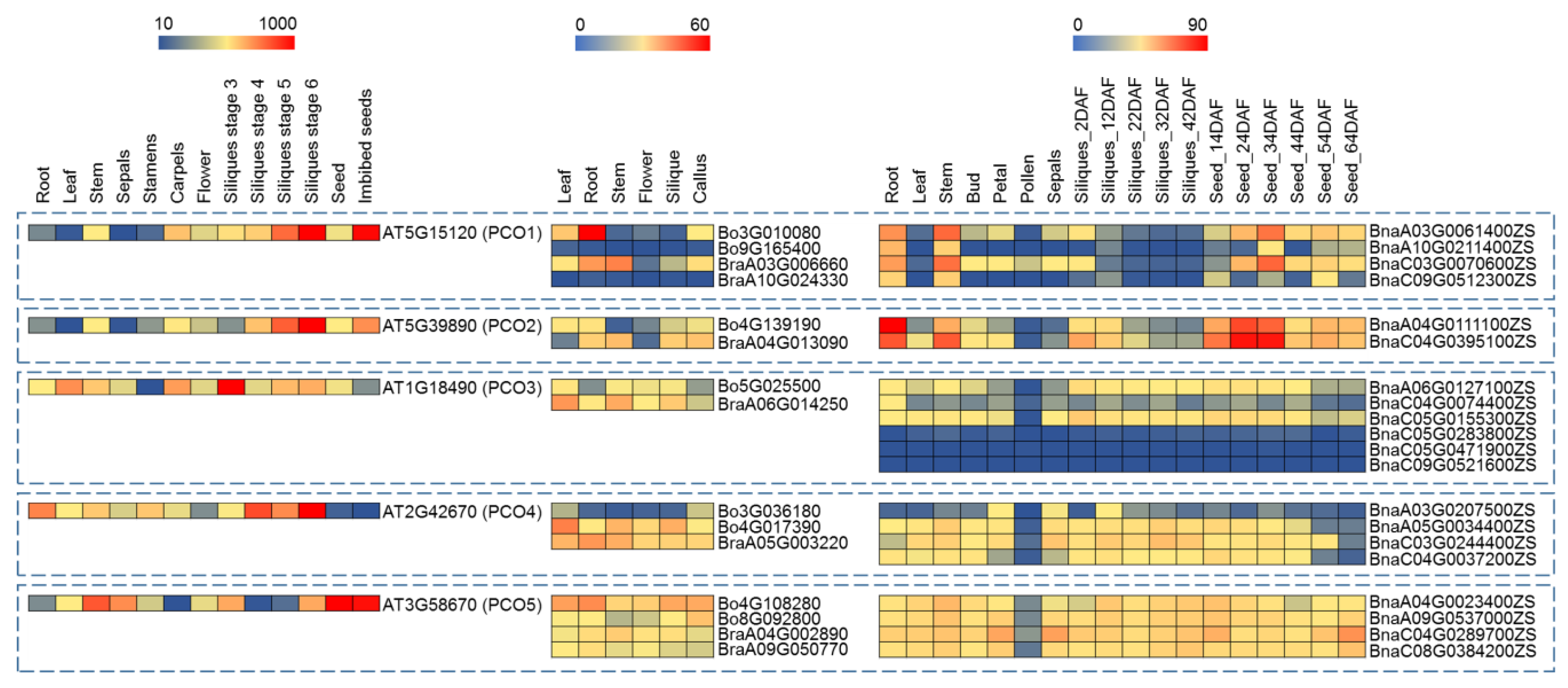

2.5. Expression Profiling of PCO Genes in Different Tissues

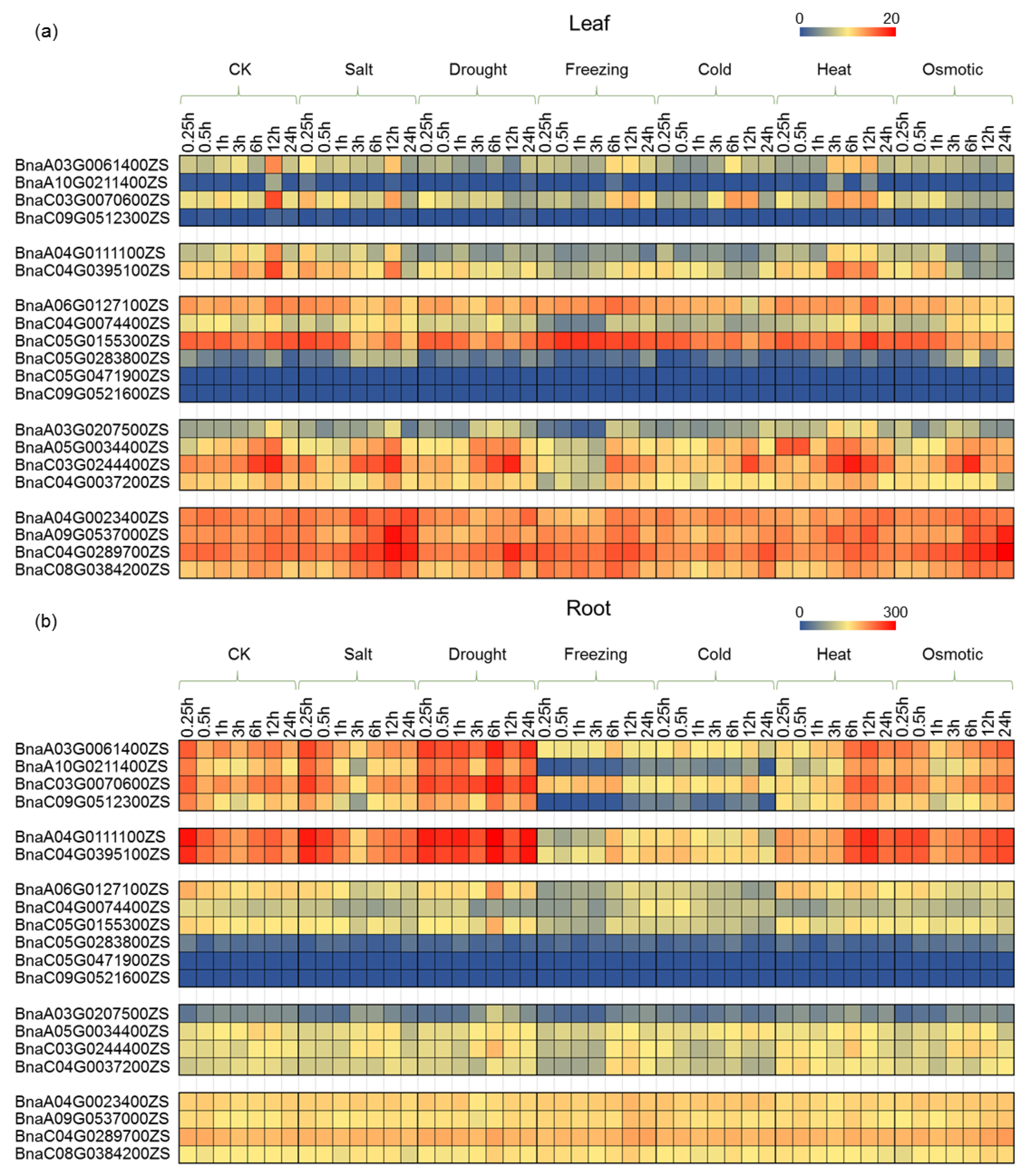

2.6. Expression Profiling of PCO Genes under Abiotic Stress Treatment

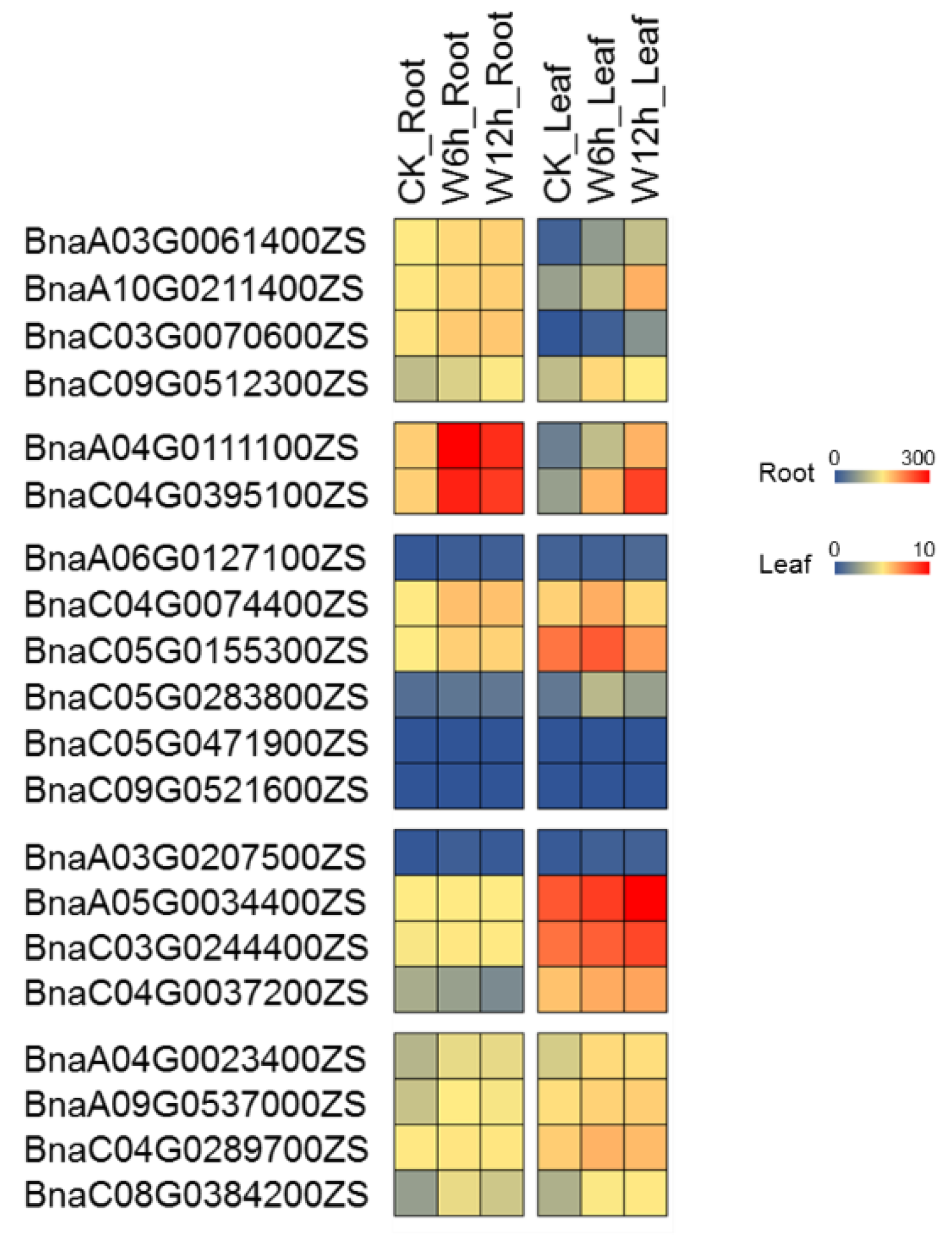

2.7. Expression Profiling of PCO Genes under Waterlogging Stress

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of the PCO Gene Family

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Chromosomal Locations

4.3. Analysis of Gene Structure, Motif Composition and Cis-element

4.4. Plant Materials and Treatments, Heat Map Analysis of the PCO Transcriptome Data

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibbs, D.J., H.M. Tedds, A.M. Labandera, M. Bailey, M.D. White, S. Hartman, C. Sprigg, S.L. Mogg, R. Osborne, C. Dambire, T. Boeckx, Z. Paling, L. Voesenek, E. Flashman, and M.J. Holdsworth, Oxygen-dependent proteolysis regulates the stability of angiosperm polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit VERNALIZATION 2. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 5438. [CrossRef]

- Weits, D.A., A.B. Kunkowska, N.C.W. Kamps, K.M.S. Portz, N.K. Packbier, Z. Nemec Venza, C. Gaillochet, J.U. Lohmann, O. Pedersen, J.T. van Dongen, and F. Licausi, An apical hypoxic niche sets the pace of shoot meristem activity. Nature, 2019. 569(7758): p. 714-717. [CrossRef]

- White, M.D., M. Klecker, R.J. Hopkinson, D.A. Weits, C. Mueller, C. Naumann, R. O’Neill, J. Wickens, J. Yang, J.C. Brooks-Bartlett, E.F. Garman, T.N. Grossmann, N. Dissmeyer, and E. Flashman, Plant cysteine oxidases are dioxygenases that directly enable arginyl transferase-catalysed arginylation of N-end rule targets. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 14690. [CrossRef]

- Weits, D.A., B. Giuntoli, M. Kosmacz, S. Parlanti, H.M. Hubberten, H. Riegler, R. Hoefgen, P. Perata, J.T. van Dongen, and F. Licausi, Plant cysteine oxidases control the oxygen-dependent branch of the N-end-rule pathway. Nat Commun, 2014. 5: p. 3425. [CrossRef]

- Licausi, F., J.T. van Dongen, B. Giuntoli, G. Novi, A. Santaniello, P. Geigenberger, and P. Perata, HRE1 and HRE2, two hypoxia-inducible ethylene response factors, affect anaerobic responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J, 2010. 62(2): p. 302-15. [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y., K. Nagai, S. Furukawa, X.J. Song, R. Kawano, H. Sakakibara, J. Wu, T. Matsumoto, A. Yoshimura, H. Kitano, M. Matsuoka, H. Mori, and M. Ashikari, The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature, 2009. 460(7258): p. 1026-30. [CrossRef]

- Hinz, M., I.W. Wilson, J. Yang, K. Buerstenbinder, D. Llewellyn, E.S. Dennis, M. Sauter, and R. Dolferus, Arabidopsis RAP2.2: an ethylene response transcription factor that is important for hypoxia survival. Plant Physiol, 2010. 153(2): p. 757-72.

- White, M.D., J. Kamps, S. East, L.J. Taylor Kearney, and E. Flashman, The plant cysteine oxidases from Arabidopsis thaliana are kinetically tailored to act as oxygen sensors. J Biol Chem, 2018. 293(30): p. 11786-11795. [CrossRef]

- White, M.D., L. Dalle Carbonare, M. Lavilla Puerta, S. Iacopino, M. Edwards, K. Dunne, E. Pires, C. Levy, M.A. McDonough, F. Licausi, and E. Flashman, Structures of Arabidopsis thaliana oxygen-sensing plant cysteine oxidases 4 and 5 enable targeted manipulation of their activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2020. 117(37): p. 23140-23147. [CrossRef]

- Masson, N., T.P. Keeley, B. Giuntoli, M.D. White, M.L. Puerta, P. Perata, R.J. Hopkinson, E. Flashman, F. Licausi, and P.J. Ratcliffe, Conserved N-terminal cysteine dioxygenases transduce responses to hypoxia in animals and plants. Science, 2019. 365(6448): p. 65-69. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Kearney, L.J., S. Madden, J. Wilson, W.K. Myers, D.M. Gunawardana, E. Pires, P. Holdship, A. Tumber, R.E.M. Rickaby, and E. Flashman, Plant cysteine oxidase oxygen-sensing function is conserved in early land plants and algae. ACS Bio Med Chem Au, 2022. 2(5): p. 521-528. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Kearney, L.J. and E. Flashman, Targeting plant cysteine oxidase activity for improved submergence tolerance. Plant J, 2022. 109(4): p. 779-788. [CrossRef]

- Dirr, A., D.M. Gunawardana, and E. Flashman, Kinetic measurements to investigate the oxygen-sensing properties of plant cysteine oxidases. Methods Mol Biol, 2023. 2648: p. 207-230.

- Chen, Z., Q. Guo, G. Wu, J. Wen, S. Liao, and C. Xu, Molecular basis for cysteine oxidation by plant cysteine oxidases from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Struct Biol, 2021. 213(1): p. 107663. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K., X. Xu, T. Fukao, P. Canlas, R. Maghirang-Rodriguez, S. Heuer, A.M. Ismail, J. Bailey-Serres, P.C. Ronald, and D.J. Mackill, Sub1A is an ethylene-response-factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature, 2006. 442(7103): p. 705-8. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F., J. Wu, and X. Wang, Genome triplication drove the diversification of Brassica plants. Hortic Res, 2014. 1: p. 14024. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., B. Chen, J. Zhao, F. Zhang, T. Xie, K. Xu, G. Gao, G. Yan, H. Li, L. Li, G. Ji, H. An, H. Li, Q. Huang, M. Zhang, J. Wu, W. Song, X. Zhang, Y. Luo, J. Chris Pires, J. Batley, S. Tian, and X. Wu, Genomic selection and genetic architecture of agronomic traits during modern rapeseed breeding. Nat Genet, 2022. 54(5): p. 694-704. [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, B., F. Denoeud, S. Liu, I.A. Parkin, H. Tang, X. Wang, J. Chiquet, H. Belcram, C. Tong, B. Samans, M. Correa, C. Da Silva, J. Just, C. Falentin, C.S. Koh, I. Le Clainche, M. Bernard, P. Bento, B. Noel, K. Labadie, A. Alberti, M. Charles, D. Arnaud, H. Guo, C. Daviaud, S. Alamery, K. Jabbari, M. Zhao, P.P. Edger, H. Chelaifa, D. Tack, G. Lassalle, I. Mestiri, N. Schnel, M.C. Le Paslier, G. Fan, V. Renault, P.E. Bayer, A.A. Golicz, S. Manoli, T.H. Lee, V.H. Thi, S. Chalabi, Q. Hu, C. Fan, R. Tollenaere, Y. Lu, C. Battail, J. Shen, C.H. Sidebottom, X. Wang, A. Canaguier, A. Chauveau, A. Berard, G. Deniot, M. Guan, Z. Liu, F. Sun, Y.P. Lim, E. Lyons, C.D. Town, I. Bancroft, X. Wang, J. Meng, J. Ma, J.C. Pires, G.J. King, D. Brunel, R. Delourme, M. Renard, J.M. Aury, K.L. Adams, J. Batley, R.J. Snowdon, J. Tost, D. Edwards, Y. Zhou, W. Hua, A.G. Sharpe, A.H. Paterson, C. Guan, and P. Wincker, Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science, 2014. 345(6199): p. 950-3. [CrossRef]

- Kayum, M.A., J.I. Park, U.K. Nath, M.K. Biswas, H.T. Kim, and I.S. Nou, Genome-wide expression profiling of aquaporin genes confer responses to abiotic and biotic stresses in Brassica rapa. BMC Plant Biol, 2017. 17(1): p. 23. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., J. Wu, W. Qi, J.A. Coulter, Y. Fang, X. Li, L. Liu, J. Jin, Z. Niu, J. Yue, and W. Sun, Screening and verification of reference genes for analysis of gene expression in winter rapeseed (Brassica rapa L.) under abiotic stress. PLoS One, 2020. 15(9): p. e0236577. [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., W. Long, L. Zeng, X. Ding, Y. Cheng, X. Zhang, and X. Zou, Melatonin-induced transcriptome variation of rapeseed seedlings under salt stress. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(21). [CrossRef]

- Tong, J., T.C. Walk, P. Han, L. Chen, X. Shen, Y. Li, C. Gu, L. Xie, X. Hu, X. Liao, and L. Qin, Genome-wide identification and analysis of high-affinity nitrate transporter 2 (NRT2) family genes in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) and their responses to various stresses. BMC Plant Biol, 2020. 20(1): p. 464. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Y. Han, S. Luo, X. Rong, H. Song, N. Jiang, C. Li, and L. Yang, Calcium peroxide alleviates the waterlogging stress of rapeseed by improving root growth status in a rice-rape rotation field. Front Plant Sci, 2022. 13: p. 1048227. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L., J. Johnson, C.E. Grant, and W.S. Noble, The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015. 43(W1): p. W39-49.

- Chen, C., H. Chen, Y. Zhang, H.R. Thomas, M.H. Frank, Y. He, and R. Xia, TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant, 2020. 13(8): p. 1194-1202. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., D.S. Favero, J. Qiu, E.H. Roalson, and M.M. Neff, Insights into the evolution and diversification of the AT-hook Motif Nuclear Localized gene family in land plants. BMC Plant Biol, 2014. 14: p. 266. [CrossRef]

- Maire, P., J. Wuarin, and U. Schibler, The role of cis-acting promoter elements in tissue-specific albumin gene expression. Science, 1989. 244(4902): p. 343-6. [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M., P. Dehais, G. Thijs, K. Marchal, Y. Moreau, Y. Van de Peer, P. Rouze, and S. Rombauts, PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res, 2002. 30(1): p. 325-7. [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.N., Y.F. Chiang-Hsieh, C.H. Chien, H.Q. Zheng, T.Y. Lee, N.Y. Wu, K.C. Tseng, P.F. Hou, and W.C. Chang, Delineation of condition specific Cis- and Trans-acting elements in plant promoters under various Endo- and exogenous stimuli. BMC Genomics, 2018. 19(Suppl 2): p. 85. [CrossRef]

- Mendiondo, G.M., D.J. Gibbs, M. Szurman-Zubrzycka, A. Korn, J. Marquez, I. Szarejko, M. Maluszynski, J. King, B. Axcell, K. Smart, F. Corbineau, and M.J. Holdsworth, Enhanced waterlogging tolerance in barley by manipulation of expression of the N-end rule pathway E3 ligase PROTEOLYSIS6. Plant Biotechnol J, 2016. 14(1): p. 40-50. [CrossRef]

- Klok, E.J., I.W. Wilson, D. Wilson, S.C. Chapman, R.M. Ewing, S.C. Somerville, W.J. Peacock, R. Dolferus, and E.S. Dennis, Expression profile analysis of the low-oxygen response in Arabidopsis root cultures. Plant Cell, 2002. 14(10): p. 2481-94. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. and Z.J. Chen, Genomic and expression plasticity of polyploidy. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2010. 13(2): p. 153-9. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., R. Wang, X. Wu, and J. Wang, Homoeolog expression bias and expression level dominance (ELD) in four tissues of natural allotetraploid Brassica napus. BMC Genomics, 2020. 21(1): p. 330. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, C.M. and J.J. Finer, Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements. Plant Sci, 2014. 217-218: p. 109-19. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., W. Wei, J.J. Tao, X. Lu, X.H. Bian, Y. Hu, T. Cheng, C.C. Yin, W.K. Zhang, S.Y. Chen, and J.S. Zhang, Nuclear factor Y subunit GmNFYA competes with GmHDA13 for interaction with GmFVE to positively regulate salt tolerance in soybean. Plant Biotechnol J, 2021. 19(11): p. 2362-2379. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., V. Dogra, R. Joshi, and S. Kumar, Stress-responsive cis-regulatory elements underline podophyllotoxin biosynthesis and better performance of Sinopodophyllum hexandrum under water deficit conditions. Front Plant Sci, 2021. 12: p. 751846. [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., W. Su, A. Gao, S.S. Mehmood, M.A. Hussain, W. Nie, Y. Lv, X. Zou, and X. Zhang, Catalase (CAT) Gene Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.): Genome-wide analysis, identification, and expression pattern in response to multiple hormones and abiotic stress conditions. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(8). [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.H., W. Li, C.F. Niu, W. Wei, Y. Hu, J.Q. Han, X. Lu, J.J. Tao, M. Jin, H. Qin, B. Zhou, W.K. Zhang, B. Ma, G.D. Wang, D.Y. Yu, Y.C. Lai, S.Y. Chen, and J.S. Zhang, A class B heat shock factor selected for during soybean domestication contributes to salt tolerance by promoting flavonoid biosynthesis. New Phytol, 2020. 225(1): p. 268-283. [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J., T. Fukao, D.J. Gibbs, M.J. Holdsworth, S.C. Lee, F. Licausi, P. Perata, L.A. Voesenek, and J.T. van Dongen, Making sense of low oxygen sensing. Trends Plant Sci, 2012. 17(3): p. 129-38. [CrossRef]

- Ambros, S., M. Kotewitsch, P.R. Wittig, B. Bammer, and A. Mustroph, Transcriptional response of two Brassica napus cultivars to short-term hypoxia in the root zone. Front Plant Sci, 2022. 13: p. 897673. [CrossRef]

- Hong, B., B. Zhou, Z. Peng, M. Yao, J. Wu, X. Wu, C. Guan, and M. Guan, Tissue-specific transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals the response mechanism of Brassica napus to waterlogging stress. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(7). [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., X. Chen, S. Zhang, J. Zhu, B. Tang, A. Wang, L. Dong, Z. Zhang, C. Yu, Y. Sun, L. Chi, H. Chen, S. Zhai, Y. Sun, L. Lan, X. Zhang, J. Xiao, Y. Bao, Y. Wang, Z. Zhang, and W. Zhao, The genome sequence archive family: toward explosive data growth and diverse data types. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics, 2021. 19(4): p. 578-583. [CrossRef]

- Members, C.-N. and Partners, Database resources of the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res, 2022. 50(D1): p. D27-D38. [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Nucleotide length (bp) | Amino acid | Molecular weight (KD) | PI | Genome location | Number of introns | Number of exons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCO1 | BnaA03G0061400ZS | 897 | 299 | 33.22 | 7.5 | ChrA03: 2,917,715-2,919,518 | 4 | 5 |

| BnaA10G0211400ZS | 924 | 308 | 34.18 | 8.01 | ChrA10: 22,378,464-22,380,486 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC03G0070600ZS | 879 | 293 | 32.75 | 7.77 | ChrC03: 3,619,461-3,621,089 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC09G0512300ZS | 771 | 257 | 28.66 | 5.91 | ChrC09: 61,478,635- 61,483,755 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo3G010080 | 876 | 292 | 32.62 | 7.52 | 3,923,348-3,924,992 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo9G165400 | 918 | 306 | 33.96 | 8.78 | 60,734,007-60,728,419 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA03G006660 | 897 | 299 | 33.3 | 7.5 | 2,874,949-2,876,803 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA10G024330 | 717 | 239 | 26.63 | 5.14 | 16,636,583-16,634,714 | 4 | 5 | |

| PCO2 | BnaA04G0111100ZS | 846 | 282 | 31.35 | 8.21 | ChrA04: 12,952,829- 12,954,006 | 4 | 5 |

| BnaC04G0395100ZS | 858 | 286 | 31.75 | 8.21 | ChrC04: 52,079,647- 52,080,830 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo4G139190 | 858 | 286 | 31.75 | 8.21 | 46,652,407-46,653,590 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA04G013090 | 846 | 282 | 31.34 | 8.02 | 9,741,294-9,742,752 | 4 | 5 | |

| PCO3 | BnaA06G0127100ZS | 831 | 277 | 30.61 | 5 | ChrA06: 7,448,257- 7,449,546 | 4 | 5 |

| BnaC04G0074400ZS | 246 | 82 | 8.65 | 4.39 | ChrC04: 6,512,883- 6,514,191 | 2 | 3 | |

| BnaC05G0155300ZS | 831 | 277 | 30.62 | 5.01 | ChrC05: 9,956,060-9,957,351 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC05G0283800ZS | 318 | 106 | 11.58 | 4.17 | ChrC05: 24,420,297-24,421,163 | 1 | 2 | |

| BnaC05G0471900ZS | 387 | 129 | 14.3 | 8.6 | ChrC05: 52,043,598- 52,044,332 | 1 | 2 | |

| BnaC09G0521600ZS | 387 | 129 | 14.23 | 8.37 | ChrC09: 62,173,896- 62,174,630 | 1 | 2 | |

| Bo5G025500 | 834 | 278 | 30.67 | 5.01 | 9,490,230-9,491,521 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA06G014250 | 831 | 277 | 30.55 | 4.89 | 7,467,637-7,469,108 | 4 | 5 | |

| PCO4 | BnaA03G0207500ZS | 624 | 208 | 23.51 | 6.5 | ChrA03: 10,842,878- 10,844,151 | 3 | 4 |

| BnaA05G0034400ZS | 729 | 243 | 27.11 | 6.03 | ChrA05: 1,925,460-1,927,173 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC03G0244400ZS | 636 | 212 | 23.54 | 8.04 | ChrC03: 14,957,859-14,959,210 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC04G0037200ZS | 717 | 239 | 26.81 | 6.42 | ChrC04: 3,448,037- 3,452,967 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo3G036180 | 636 | 212 | 23.53 | 8.04 | 15,839,677-15,841,028 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo4G017390 | 717 | 239 | 26.75 | 6.23 | 3,496,211-3,497,884 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA05G003220 | 717 | 239 | 26.72 | 6.42 | 1,719,860-1,722,377 | 4 | 5 | |

| PCO5 | BnaA04G0023400ZS | 729 | 243 | 27.23 | 6.84 | ChrA04: 1,525,382-1,527,222 | 4 | 5 |

| BnaA09G0537000ZS | 729 | 243 | 27.13 | 6.59 | ChrA09: 56,193,470-56,194,841 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC04G0289700ZS | 729 | 243 | 27.22 | 6.78 | ChrC04: 39,729,996- 39,732,404 | 4 | 5 | |

| BnaC08G0384200ZS | 729 | 243 | 27.2 | 6.5 | ChrC08: 44,790,558- 44,792,029 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo4G108280 | 729 | 243 | 27.22 | 6.78 | 34,730,028-34,731,729 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bo8G092800 | 729 | 243 | 27.2 | 6.5 | 41,444,747-41,446,184 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA04G002890 | 729 | 243 | 27.22 | 6.99 | 1,612,409-1,614,775 | 4 | 5 | |

| BraA09G050770 | 729 | 243 | 27.12 | 6.59 | 36,671,235-36,668,985 | 4 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).