Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

09 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

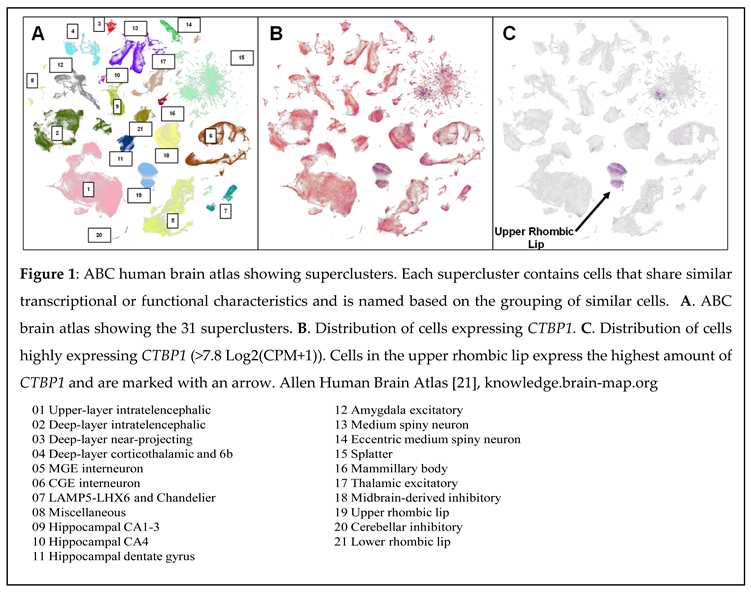

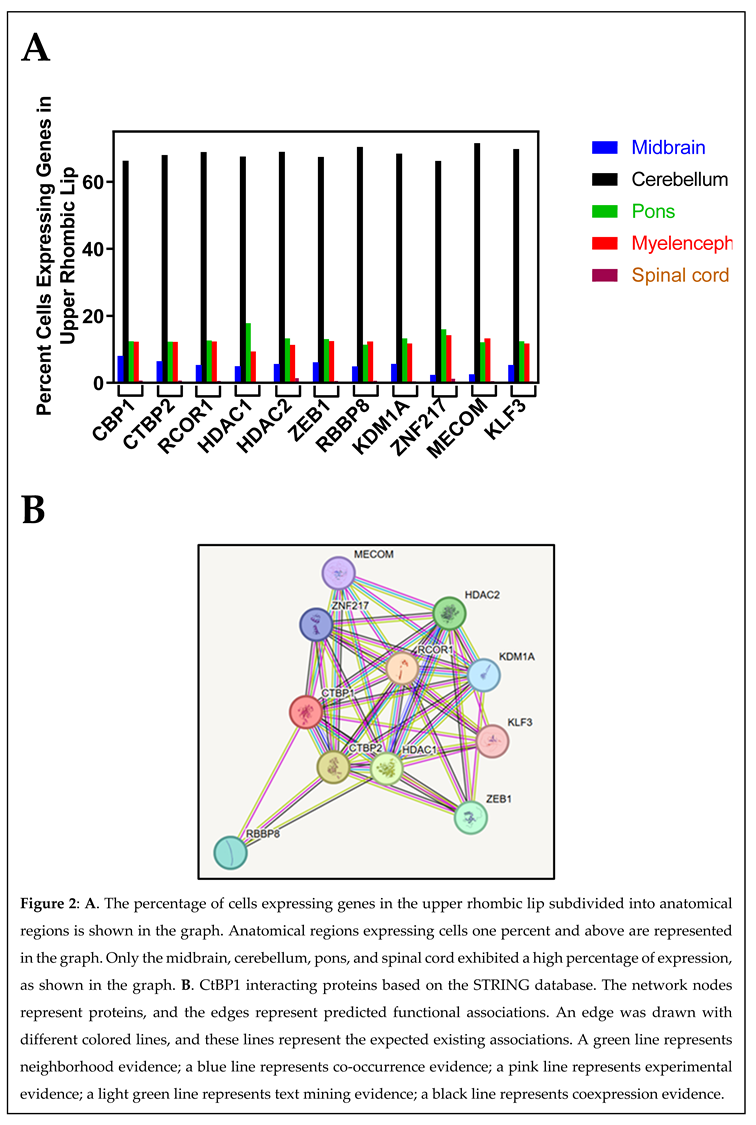

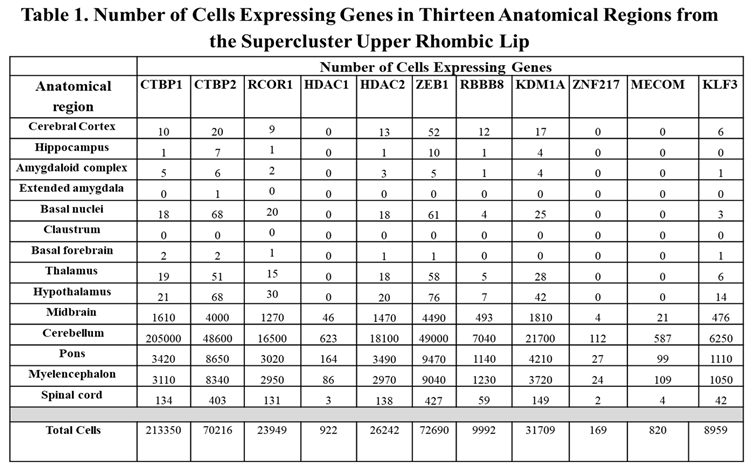

C-terminal binding proteins (CtBPs) dimerize and function predominantly as transcriptional corepressors by targeting various chromatin-modifying factors to promoter-bound repressors. Hypotonia, Ataxia, Developmental-Delay, and Tooth-Enamel Defects Syndrome (HADDTS) is a recently discovered neurodevelopmental disorder resulting from a heterozygous missense mutation in CTBP1. It is often associated with the early onset of profound cerebellar atrophy in patients. To understand CtBP1's role in brain function and the etiology of HADDTS, Allen Institute’s Allen Brain Cell (ABC) human brain atlas was used. Based on the ABC atlas, CTBP1 is highly expressed in the upper rhombic lip supercluster which gives rise to the majority of the cerebellar granule cells. The results correlate with the cerebellum related manifestations observed in HADDTS patients.

Keywords:

Role of CtBP

CtBP1 and HADDTS

ABC Atlas

Upper Rhombic Lip

CtBP1-Interacting Proteins

CTBP2

RCOR1

HDAC1 and HDCA2

ZEB1

RBBP8

KLF3

KDM1A

MECOM

ZNF217

CtBP1-Interacting Proteins and the Upper Rhombic Lip

Notes

Author Contributions

Acknowledgment

References

- Chinnadurai, G. CtBP, an unconventional transcriptional corepressor in development and oncogenesis. Mol Cell 2002, 9, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnadurai, G. Transcriptional regulation by C-terminal binding proteins. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2007, 39, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.; Imig, C.; Camacho, M.; Reinhold, A.; Guhathakurta, D.; Montenegro-Venegas, C.; Cousin, M. A.; Gundelfinger, E. D.; Rosenmund, C.; Cooper, B.; et al. CtBP1-Mediated Membrane Fission Contributes to Effective Recycling of Synaptic Vesicles. Cell Rep 2020, 30, 2444–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.; Singh, R. CtBP: A global regulator of balancing acts and homeostases. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2023, 1878, 188886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Hao, D.; Li, P.; Su, M.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.; Tai, L.; Lu, J.; et al. Metabolic modulation of CtBP dimeric status impacts the repression of DNA damage repair genes and the platinum sensitivity of ovarian cancer. Int J Biol Sci 2023, 19, 2081–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Sawada, J.; Sui, G.; Affar el, B.; Whetstine, J. R.; Lan, F.; Ogawa, H.; Luke, M. P.; Nakatani, Y. Coordinated histone modifications mediated by a CtBP co-repressor complex. Nature 2003, 422, 735–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambhani, C.; Chang, J. L.; Akey, D. L.; Cadigan, K. M. The oligomeric state of CtBP determines its role as a transcriptional co-activator and co-repressor of Wingless targets. EMBO J 2011, 30, 2031–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J. D.; Soriano, P. Overlapping and unique roles for C-terminal binding protein 1 (CtBP1) and CtBP2 during mouse development. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 5296–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, E.; Li, X.; Lewicki, J.; Neofytou, C.; Guerout, N.; Barnabe-Heider, F.; Hermanson, O. The corepressor CtBP2 is required for proper development of the mouse cerebral cortex. Mol Cell Neurosci 2020, 104, 103481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, C.; Lopes-Nunes, J.; Esteves, M.; Santos, T.; Vale, A.; Cristovao, A. C.; Ferreira, R.; Bernardino, L. CtBP Neuroprotective Role in Toxin-Based Parkinson's Disease Models: From Expression Pattern to Dopaminergic Survival. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 4246–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Hu, Y. CTBP1 Confers Protection for Hippocampal and Cortical Neurons in Rat Models of Alzheimer's Disease. Neuroimmunomodulation 2019, 26, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankiewicz, T. R.; Schroeder, E. K.; Kelsey, N. A.; Bouchard, R. J.; Linseman, D. A. C-terminal binding proteins are essential pro-survival factors that undergo caspase-dependent downregulation during neuronal apoptosis. Mol Cell Neurosci 2013, 56, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubler, D.; Rankovic, M.; Richter, K.; Lazarevic, V.; Altrock, W. D.; Fischer, K. D.; Gundelfinger, E. D.; Fejtova, A. Differential spatial expression and subcellular localization of CtBP family members in rodent brain. PloS one 2012, 7, e39710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Blevins, M.; Norris, D.; Zhao, R.; Huang, M. C-terminal binding proteins 1 and 2 in traumatic brain injury-induced inflammation and their inhibition as an approach for anti-inflammatory treatment. Int J Biol Sci 2020, 16, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Fekete, D. M.; Andrisani, O. M. CtBP2 downregulation during neural crest specification induces expression of Mitf and REST, resulting in melanocyte differentiation and sympathoadrenal lineage suppression. Mol Cell Biol 2011, 31, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D. B.; Cho, M. T.; Millan, F.; Yates, C.; Hannibal, M.; O'Connor, B.; Shinawi, M.; Connolly, A. M.; Waggoner, D.; Halbach, S.; et al. A recurrent de novo CTBP1 mutation is associated with developmental delay, hypotonia, ataxia, and tooth enamel defects. Neurogenetics 2016, 17, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D. B.; Subramanian, T.; Vijayalingam, S.; Ezekiel, U. R.; Donkervoort, S.; Yang, M. L.; Dubbs, H. A.; Ortiz-Gonzalez, X. R.; Lakhani, S.; Segal, D.; et al. A pathogenic CtBP1 missense mutation causes altered cofactor binding and transcriptional activity. Neurogenetics 2019, 20, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Baena, N.; Tejada-Moreno, J. A.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Villegas-Lanau, C. A. CTBP1 and CTBP2 mutations underpinning neurological disorders: a systematic review. Neurogenetics 2022, 23, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, E. W.; Alston, C. L.; Pyle, A.; He, L.; Falkous, G.; Naismith, K.; Chinnery, P. F.; McFarland, R.; Taylor, R. W. De novo CTBP1 variant is associated with decreased mitochondrial respiratory chain activities. Neurol Genet 2017, 3, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D. B.; Subramanian, T.; Vijayalingam, S.; Ezekiel, U. R.; Donkervoort, S.; Yang, M. L.; Dubbs, H. A.; Ortiz-Gonzalez, X. R.; Lakhani, S.; Segal, D.; et al. A pathogenic CtBP1 missense mutation causes altered cofactor binding and transcriptional activity. Neurogenetics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaldivar, A.; Krichmar, J. L. Allen Brain Atlas-Driven Visualizations: a web-based gene expression energy visualization tool. Front Neuroinform 2014, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo-Triana, C. A.; Leon, L. A.; Cardenas, F. P. Comparing the Expression of Genes Related to Serotonin (5-HT) in C57BL/6J Mice and Humans Based on Data Available at the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas and Allen Human Brain Atlas. Neurol Res Int 2017, 2017, 7138926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consalez, G. G.; Goldowitz, D.; Casoni, F.; Hawkes, R. Origins, Development, and Compartmentation of the Granule Cells of the Cerebellum. Front Neural Circuits 2020, 14, 611841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, K.; Chotiyanonta, J.; Wu, D.; Miller, M. I.; Mori, S.; Oishi, K.; Pediatric Imaging, N.; Genetics, S. Developmental trajectories of the human embryologic brain regions. Neurosci Lett 2019, 708, 134342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siletti K, et al, Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science 2023, 382, eadd7046. DOI:10.1126/science.add7046. [Dataset]. Available from https://assets.nemoarchive.org/dat- 5ie1mec.

- Vijayalingam, S.; Ezekiel, U. R.; Xu, F.; Subramanian, T.; Geerling, E.; Hoelscher, B.; San, K.; Ganapathy, A.; Pemberton, K.; Tycksen, E.; et al. Human iPSC-Derived Neuronal Cells From CTBP1-Mutated Patients Reveal Altered Expression of Neurodevelopmental Gene Networks. Frontiers in neuroscience 2020, 14, 562292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A. L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N. T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Dang, X.; Fan, J.; Song, T.; Li, Z.; Duan, N.; Zhang, W. The CtIP-CtBP1/2-HDAC1-AP1 transcriptional complex is required for the transrepression of DNA damage modulators in the pathogenesis of osteosarcoma. Translational oncology 2022, 21, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Wilson, D. M. , 3rd. The involvement of DNA-damage and -repair defects in neurological dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet 2008, 82, 539–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakula, A.; Nagar, S. E.; Sumru Bayin, N.; Christensen, J. B.; Stephen, D. N.; Reid, A. J.; Koche, R.; Joyner, A. L. An increase in reactive oxygen species underlies neonatal cerebellum repair. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Katyal, S.; Li, Y.; El-Khamisy, S. F.; Russell, H. R.; Caldecott, K. W.; McKinnon, P. J. The genesis of cerebellar interneurons and the prevention of neural DNA damage require XRCC1. Nat Neurosci 2009, 12, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monestime, C. M.; Taibi, A.; Gates, K. P.; Jiang, K.; Sirotkin, H. I. CoRest1 regulates neurogenesis in a stage-dependent manner. Dev Dyn 2019, 248, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macinkovic, I.; Theofel, I.; Hundertmark, T.; Kovac, K.; Awe, S.; Lenz, J.; Forne, I.; Lamp, B.; Nist, A.; Imhof, A.; et al. Distinct CoREST complexes act in a cell-type-specific manner. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 11649–11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wu, J.; Hu, X. L.; Yang, X.; Shen, Q. ZEB1 Represses Neural Differentiation and Cooperates with CTBP2 to Dynamically Regulate Cell Migration during Neocortex Development. Cell Rep 2019, 27, 2335–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D. L.; Apara, A.; Goldberg, J. L. Kruppel-like transcription factors in the nervous system: novel players in neurite outgrowth and axon regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci 2011, 47, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, B.; Ruitu, L.; Murn, J.; Hempel, K.; Ferrao, R.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, S.; Garcia, B. A.; Wu, H.; Wu, F.; et al. A specific LSD1/KDM1A isoform regulates neuronal differentiation through H3K9 demethylation. Mol Cell 2015, 57, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, M.; Katoh, M. Notch ligand, JAG1, is evolutionarily conserved target of canonical WNT signaling pathway in progenitor cells. International journal of molecular medicine 2006, 17, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leszczynski, P.; Smiech, M.; Parvanov, E.; Watanabe, C.; Mizutani, K. I.; Taniguchi, H. Emerging Roles of PRDM Factors in Stem Cells and Neuronal System: Cofactor Dependent Regulation of PRDM3/16 and FOG1/2 (Novel PRDM Factors). Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izutsu, K.; Kurokawa, M.; Imai, Y.; Maki, K.; Mitani, K.; Hirai, H. The corepressor CtBP interacts with Evi-1 to repress transforming growth factor beta signaling. Blood 2001, 97, 2815–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, K. G.; Nardini, M.; Verger, A.; Francescato, P.; Yaswen, P.; Corda, D.; Bolognesi, M.; Crossley, M. Specific recognition of ZNF217 and other zinc finger proteins at a surface groove of C-terminal binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol 2006, 26, 8159–8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banck, M. S.; Li, S.; Nishio, H.; Wang, C.; Beutler, A. S.; Walsh, M. J. The ZNF217 oncogene is a candidate organizer of repressive histone modifiers. Epigenetics : official journal of the DNA Methylation Society 2009, 4, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. A.; Donini, C. F.; Nguyen, N. T.; Lincet, H.; Vendrell, J. A. The dark side of ZNF217, a key regulator of tumorigenesis with powerful biomarker value. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 41566–41581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, N.; Matsuki, T.; Iwamoto, I.; Nishijo, T.; Noda, M.; Tabata, H.; Nakayama, A.; Nagata, K. I. Expression analyses of C-terminal-binding protein 1 (CtBP1) during mouse brain development. Dev Neurosci 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, H.; Faber, J.; Timmann, D.; Klockgether, T. Update cerebellum and cognition. J Neurol 2021, 268, 3921–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Li, H.; Du, B.; Dang, Q.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ding, G.; Lu, C.; Guo, T. The cerebellum and cognition: further evidence for its role in language control. Cereb Cortex 2022, 33, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova D, Dirks A, Montenegro-Venegas C, Schöne C, Altrock WD, Marini C, Frischknecht R, Schanze D, Zenker M, Gundelfinger ED, Fejtova A. Synaptic activity controls localization and function of CtBP1 via binding to Bassoon and Piccolo. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 1056–77. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).