Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

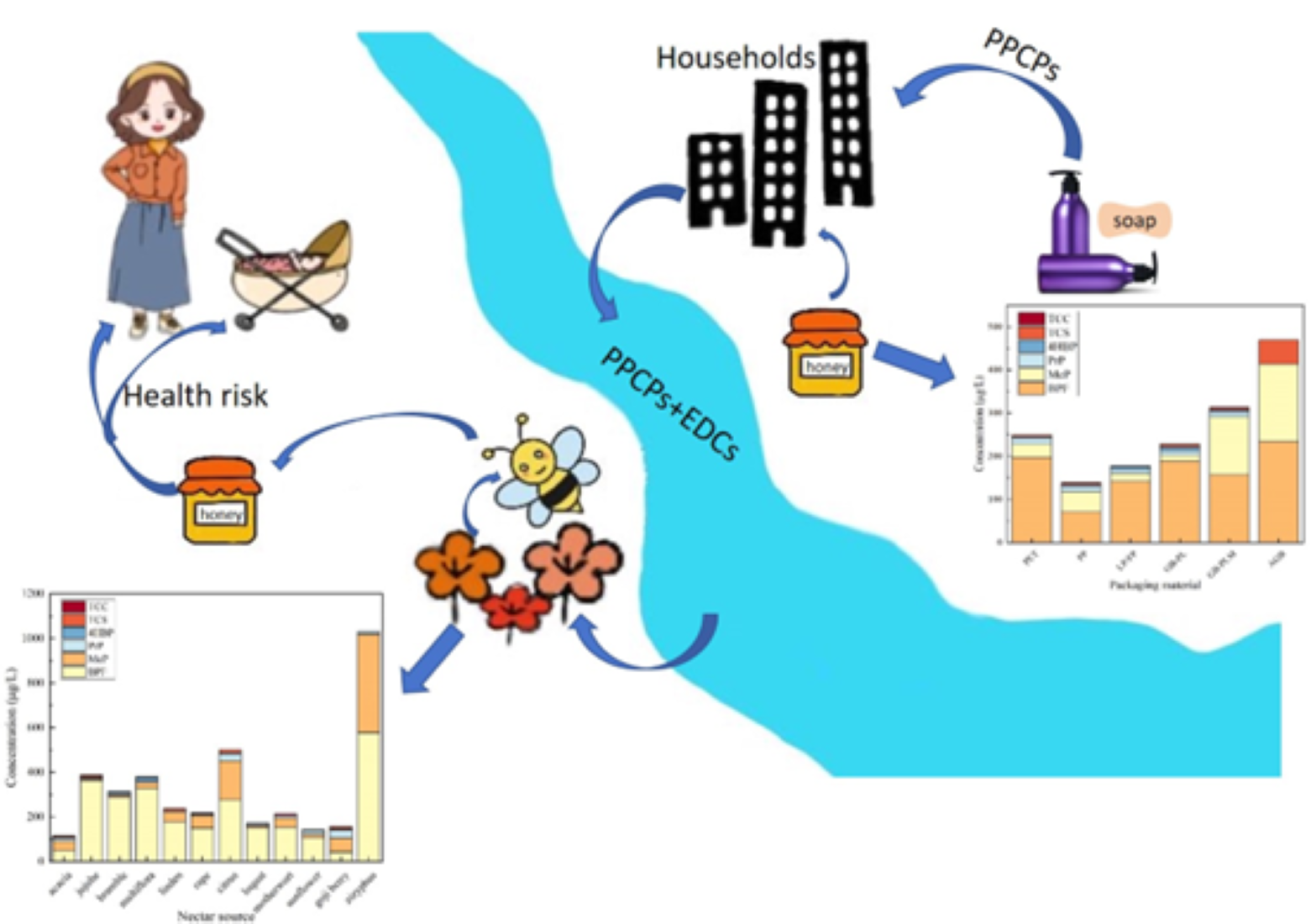

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

2.2. Samples Collection and Preparation

2.3. Instrumentation

2.4. DLLME Procedure

2.5. Calculations and Data Processing

3. Results and Discussion

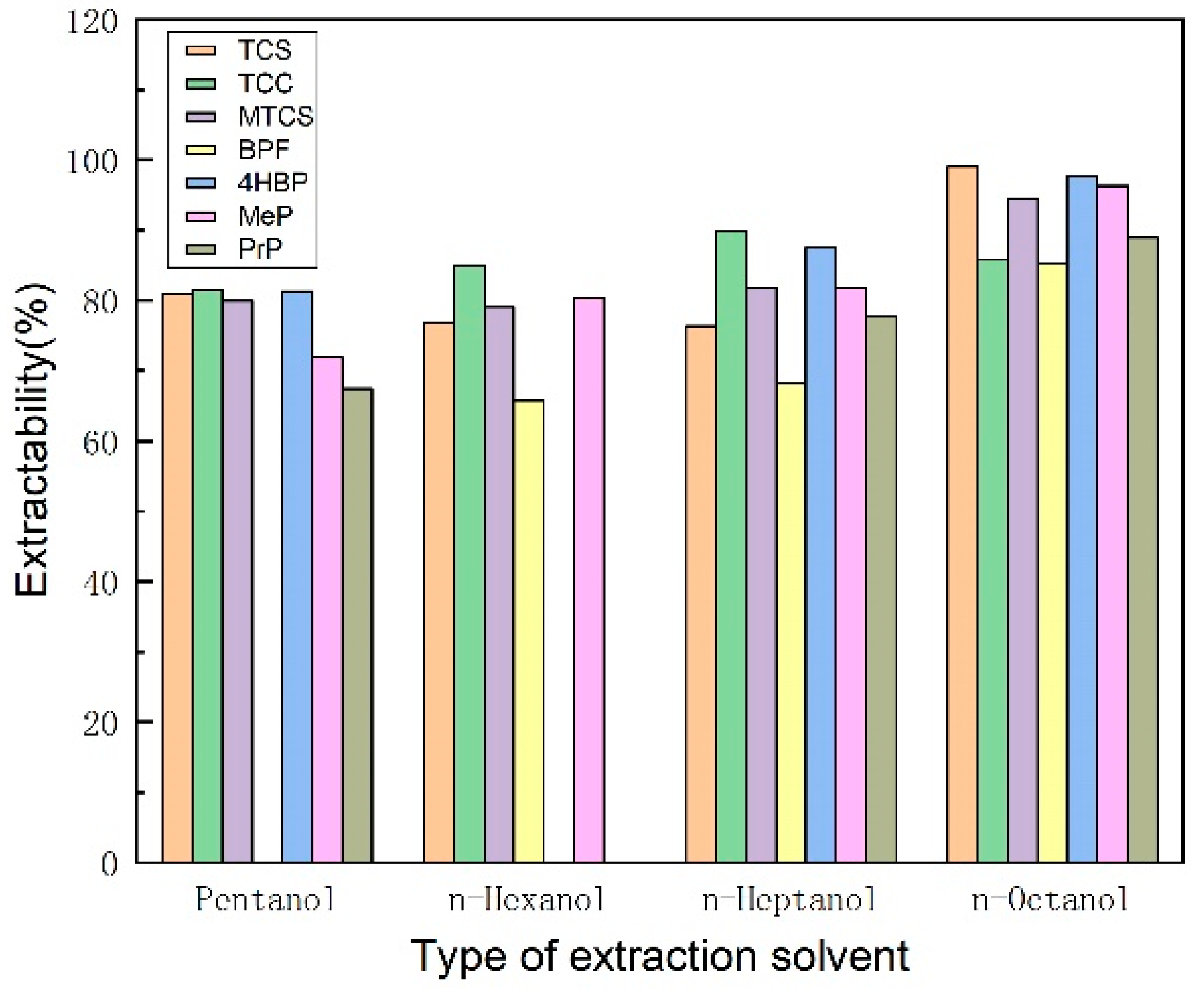

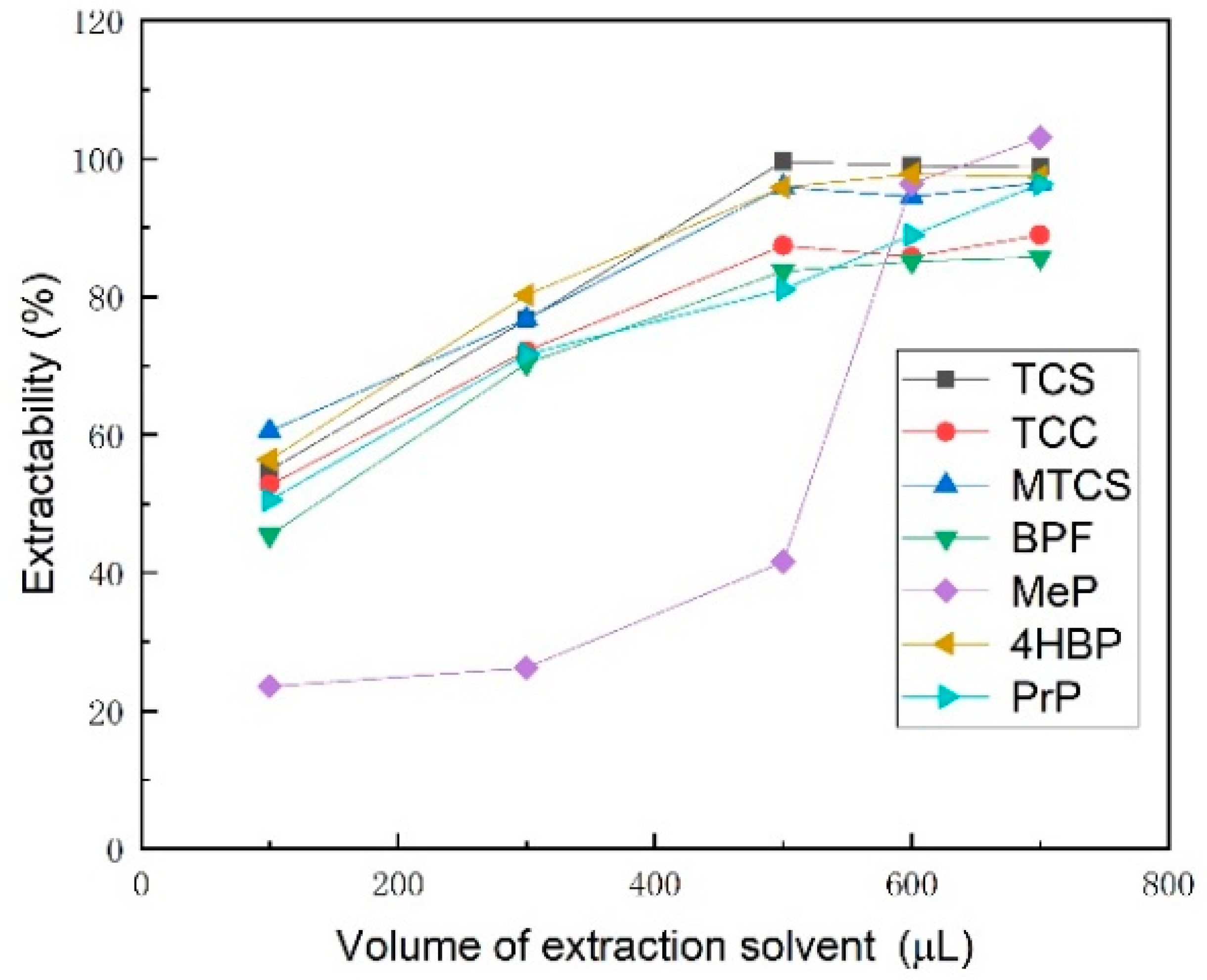

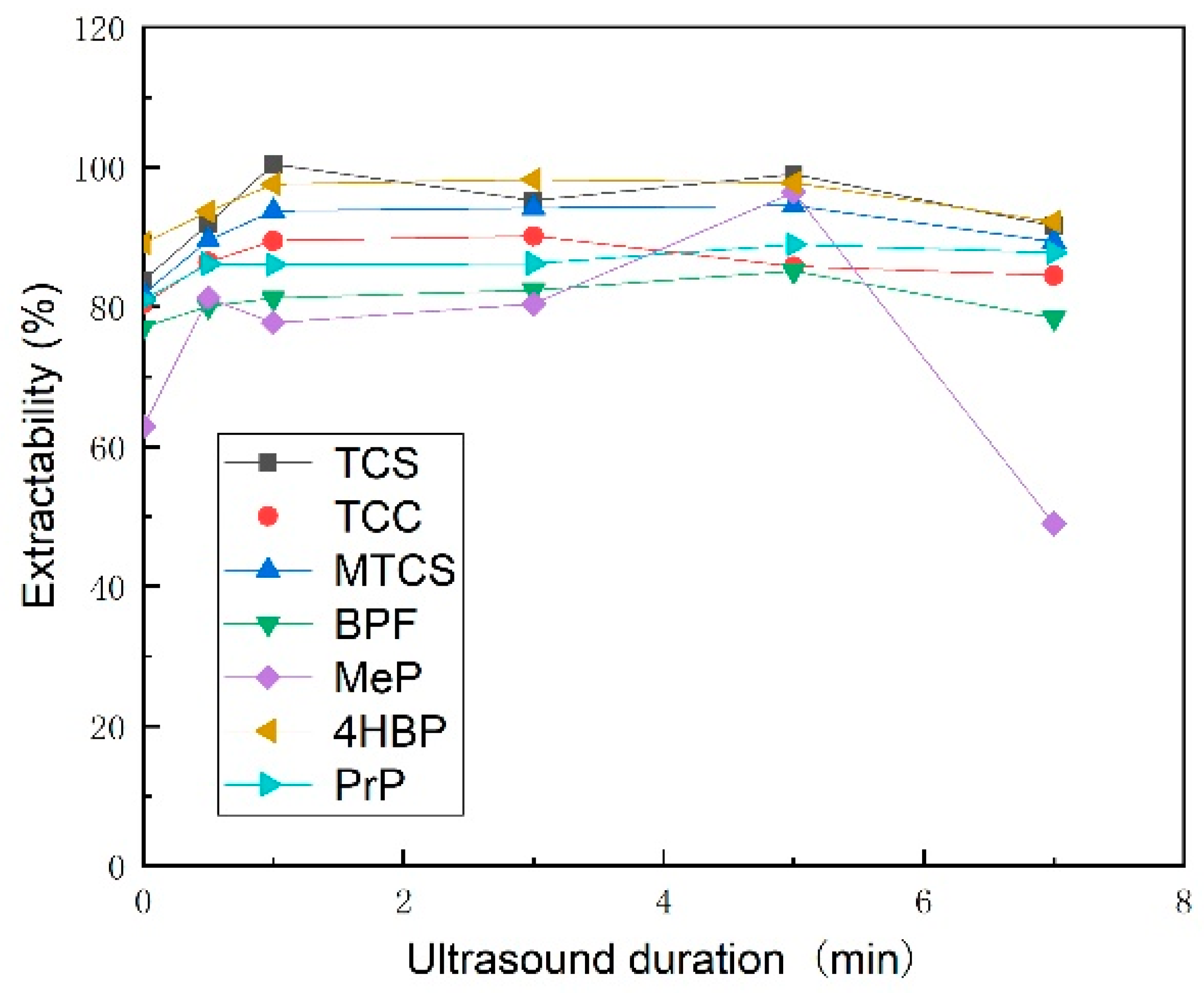

3.1. Optimization of DLLME Operation Parameters

3.1.1. Selection of Extractant Type and Dosage

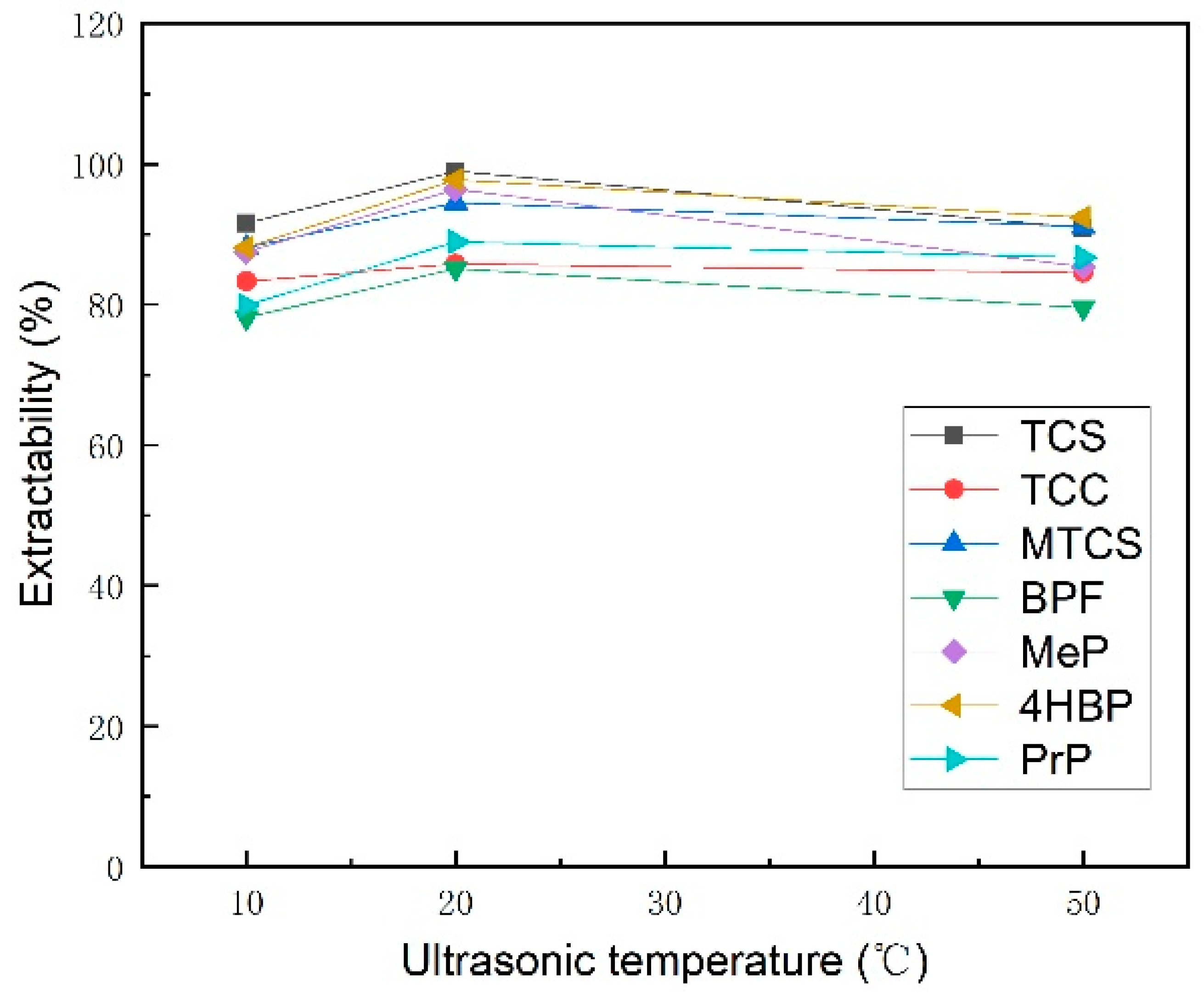

3.1.2. Selection of Extraction Time and Extraction Temperature

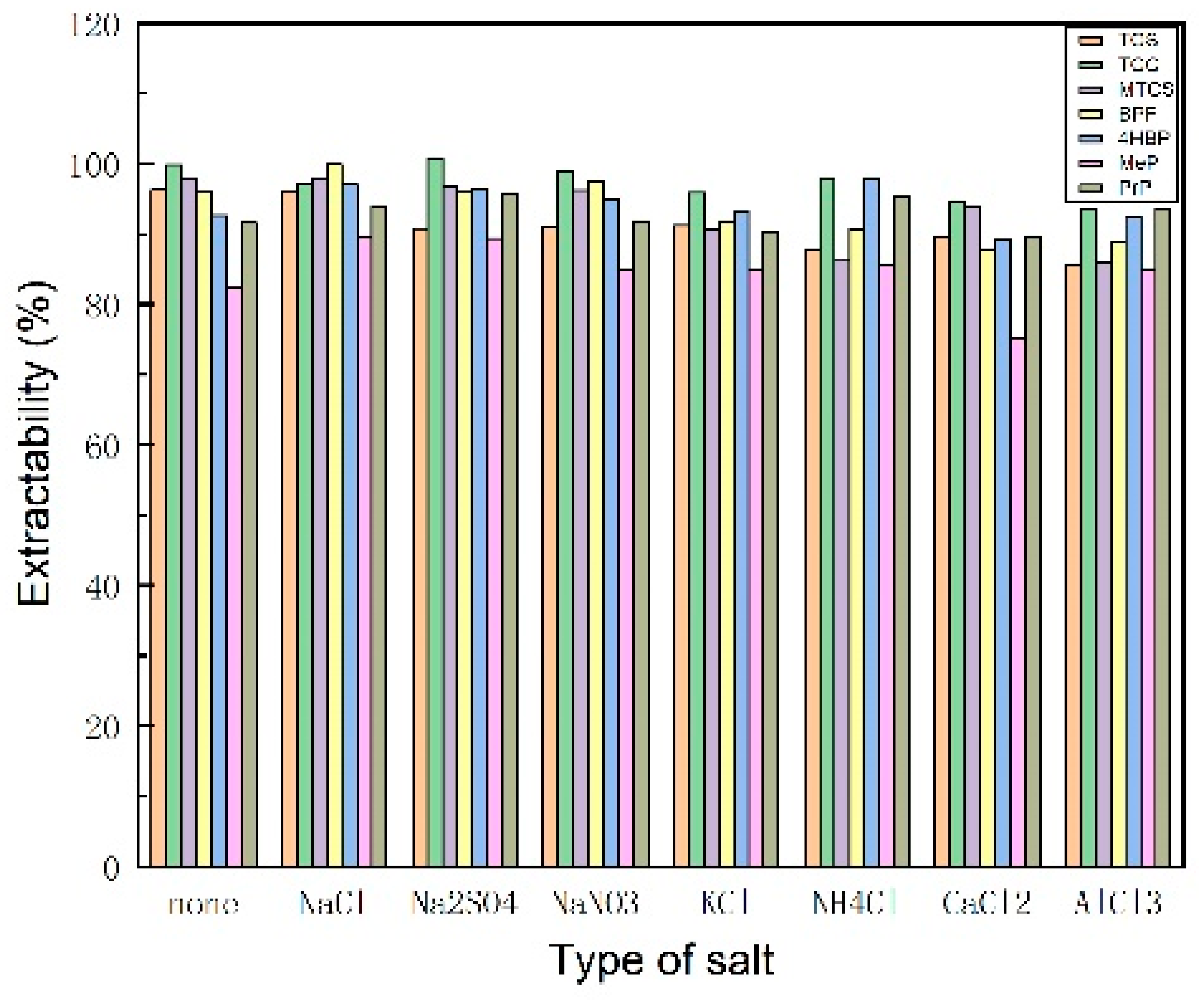

3.1.3. Selection of Inorganic Salt Type and Dosage

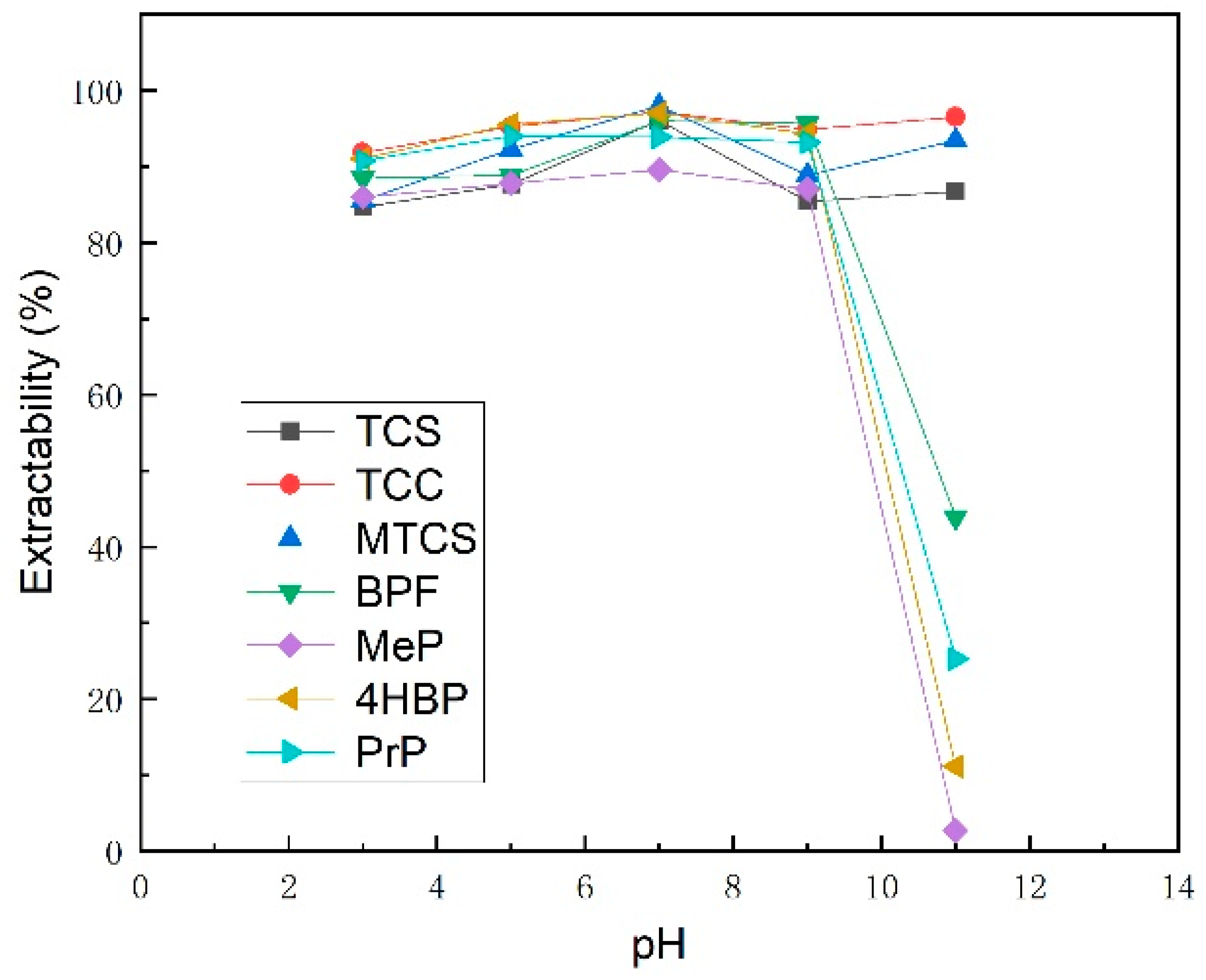

3.1.4. pH

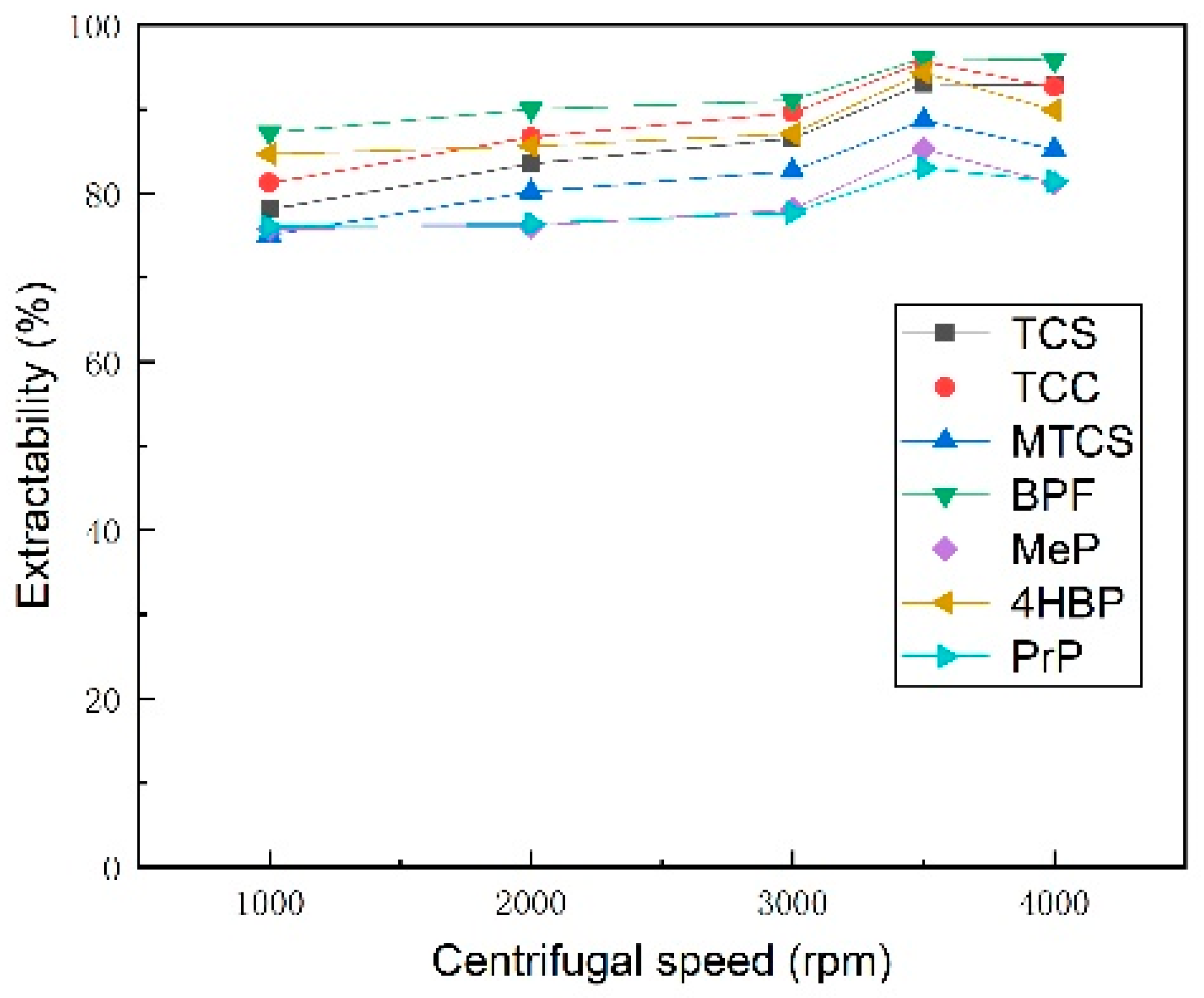

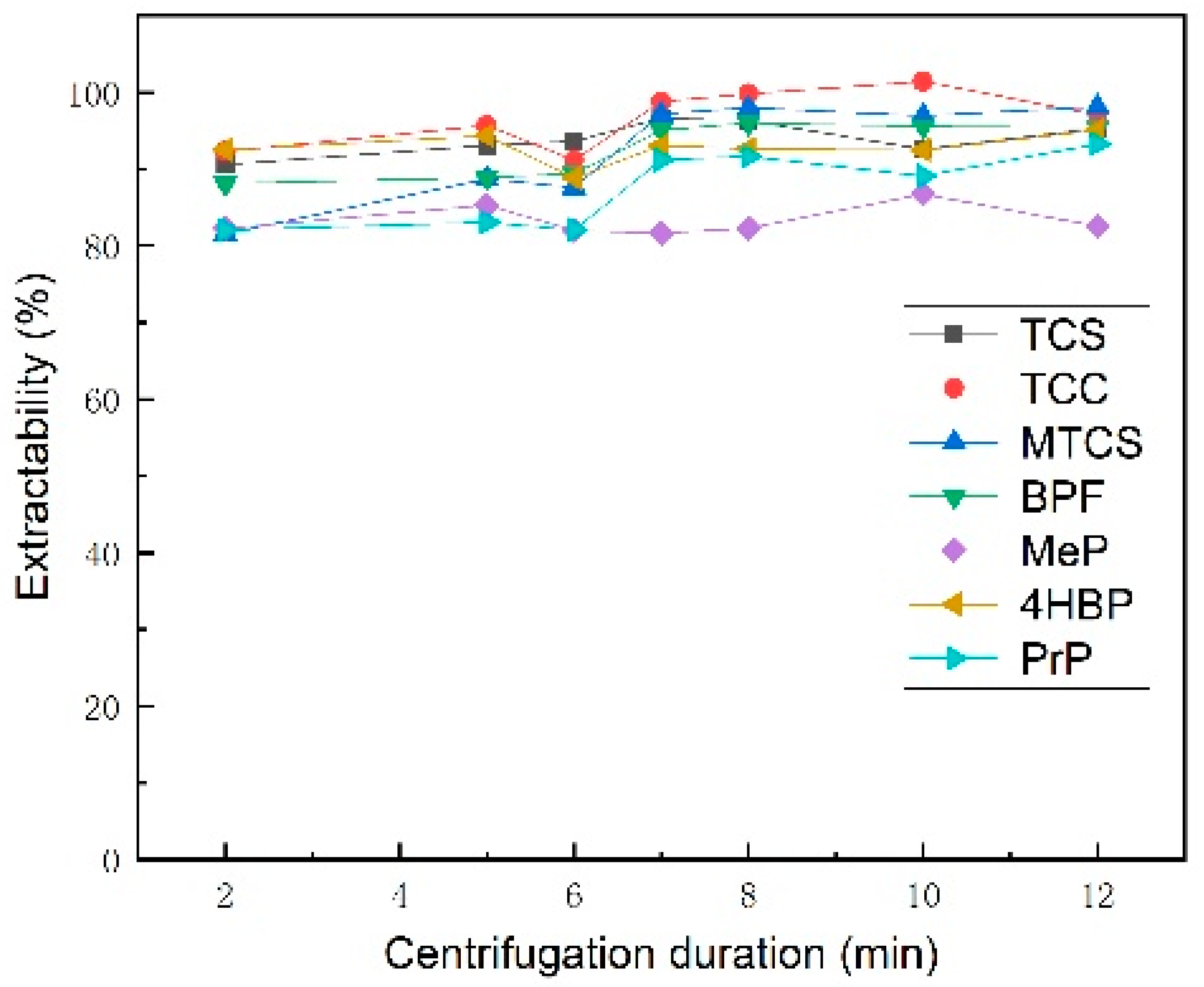

3.1.5. Selection of Centrifugal Speed and Duration

3.2. Method Validation

3.3. Real Sample Analysis

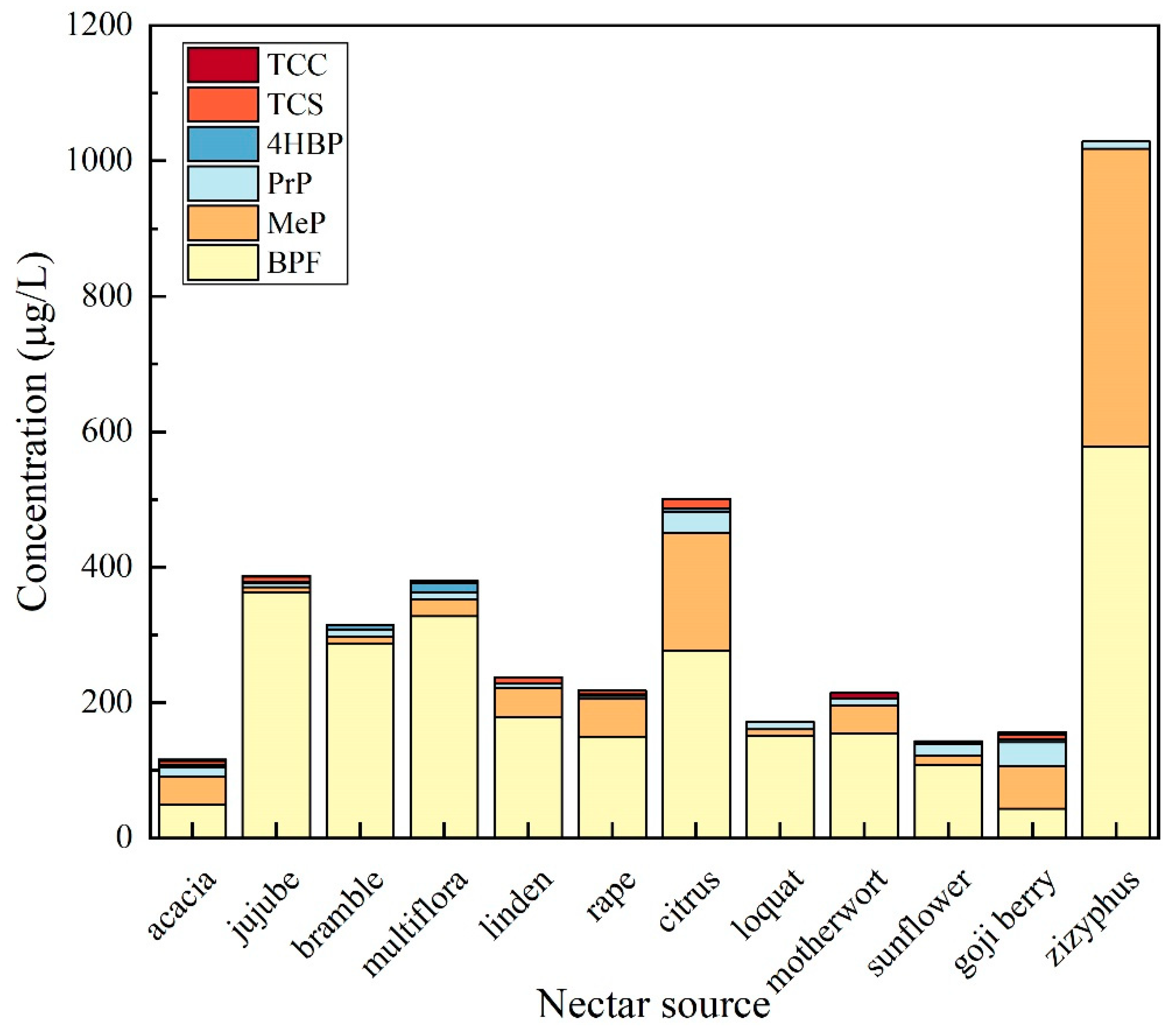

3.3.1. Analysis of the Distribution of EDCs in Honey from Different Nectar Sources

| Nectar source | Detection rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| 4HBP | acacia honey | 22.22(2/9) | ND-50.62 |

| jujube honey | 25(1/4) | ND-<LOQ | |

| vitex honey | 33.33(1/3) | ND-172.3 | |

| linden flower | 0(0/4) | ND | |

| rape flower honey | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| citrus honey | 33.33(1/3) | ND-94.43 | |

| loquat honey | 0(0/1) | ND | |

| multifloral honey | 69.23(9/13) | ND-294.9 | |

| sunflower honey | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| motherwort honey | 0(0/1) | ND | |

| wolfberry honey | 50(1/2) | ND-<LOQ | |

| milk vetch honey | 0(0/1) | ND |

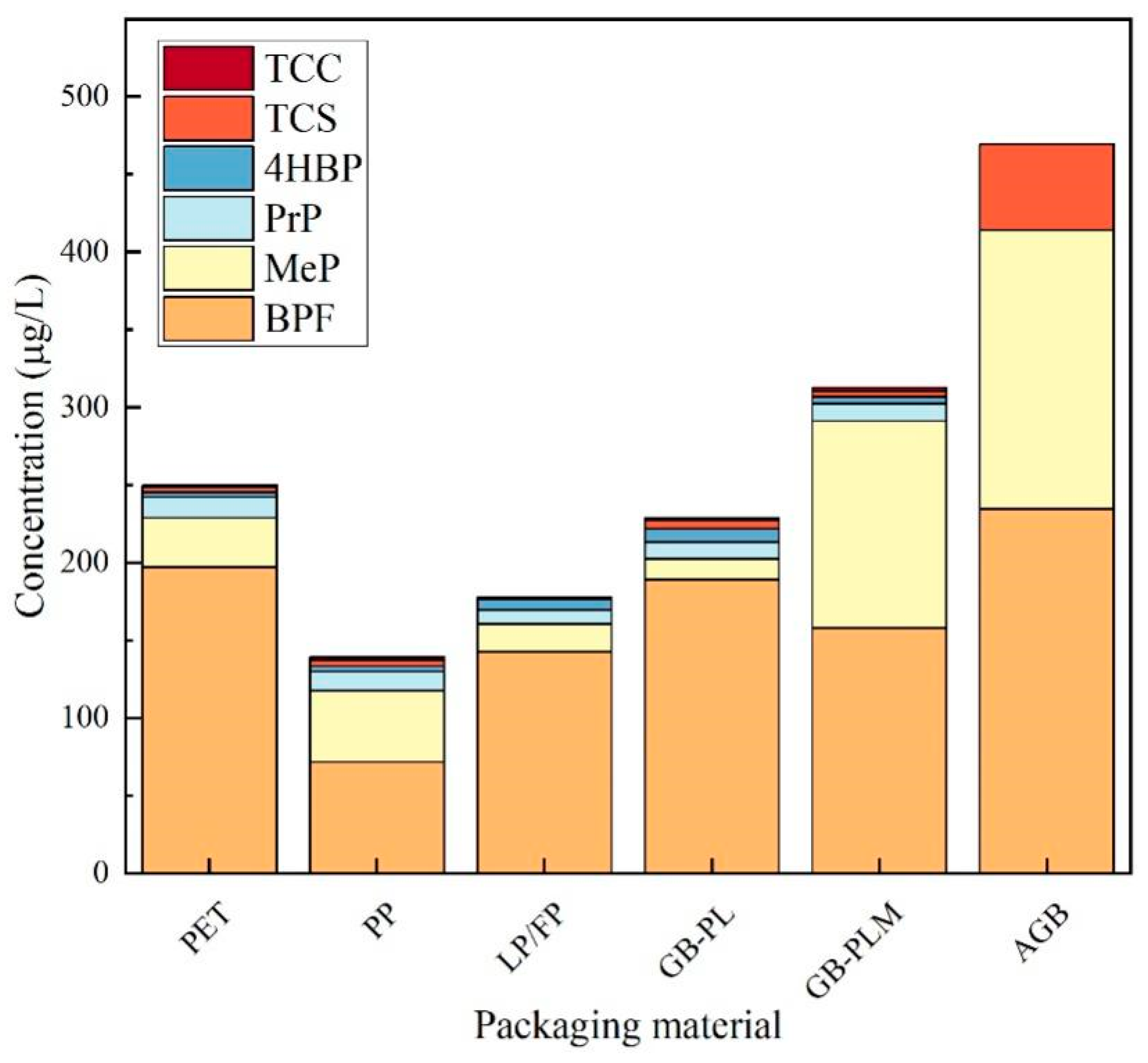

3.3.2. Analysis of Honey Contamination by EDCs in Packaging Made of Different Materials

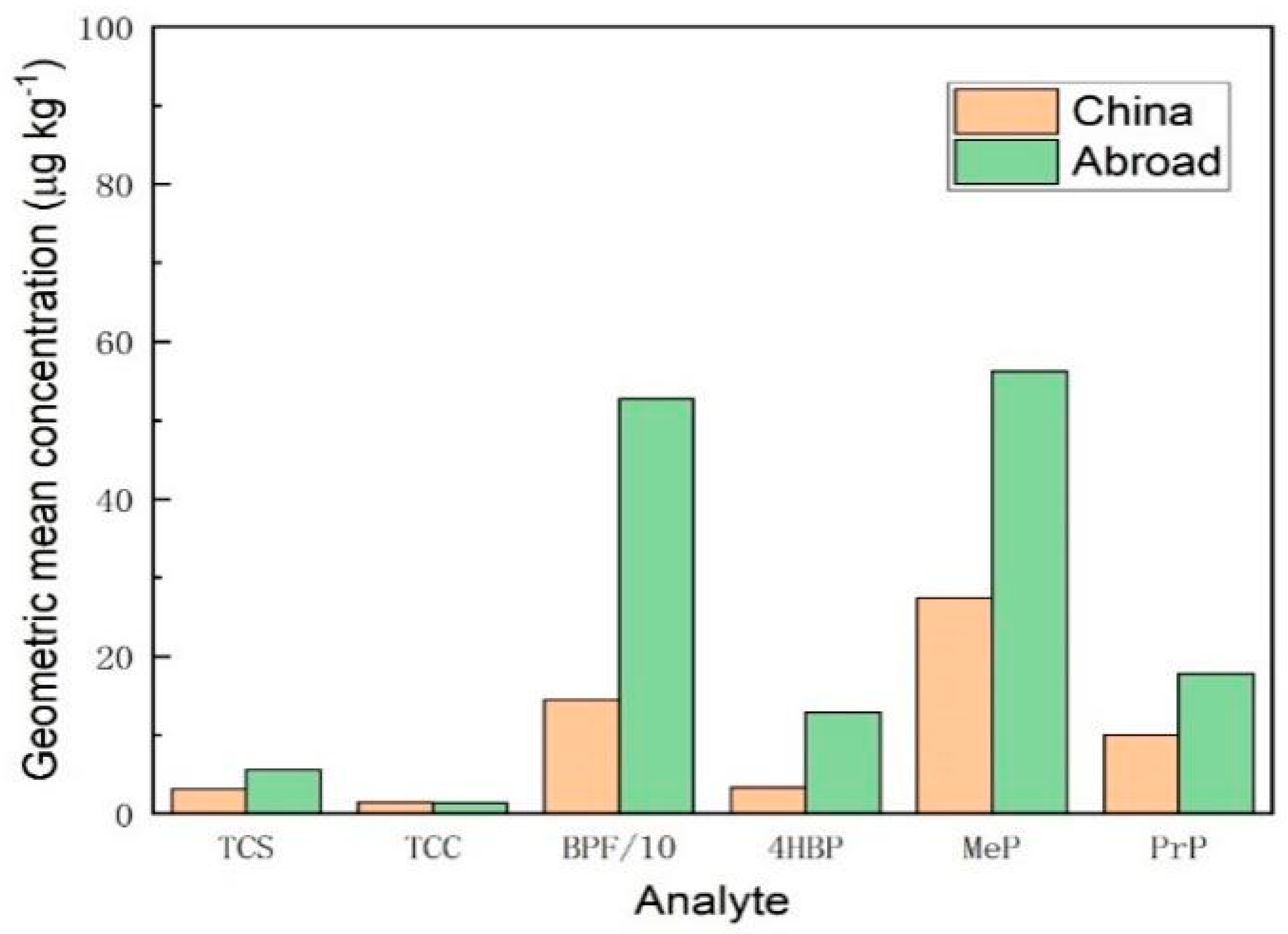

3.3.3. Comparison of Contamination of Honey at Home and Abroad

3.4. Daily Intake and Health Risk Assessment

3.4.1. Daily Intake and Health Risk Assessment for Adults

3.4.2. Daily Intake and Health Risk Assessment for Infants

4. Conclusions

References

- SCOGNAMIGLIO V, ANTONACCI A, PATROLECCO L, et al. Analytical tools monitoring endocrine disrupting chemicals [J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2016, 80: 555-67.

- DE COSTER S, VAN LAREBEKE N. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: associated disorders and mechanisms of action [J]. J Environ Public Health, 2012, 2012: 713696.

- AZZOUZ A, KAILASA S K, KUMAR P, et al. Advances in functional nanomaterial-based electrochemical techniques for screening of endocrine disrupting chemicals in various sample matrices [J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2019, 113: 256-79.

- BOCATO M Z, CESILA C A, LATARO B F, et al. A fast-multiclass method for the determination of 21 endocrine disruptors in human urine by using vortex-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (VADLLME) and LC-MS/MS [J]. Environ Res, 2020, 189: 109883.

- GEE R H, CHARLES A, TAYLOR N, et al. Oestrogenic and androgenic activity of triclosan in breast cancer cells [J]. J Appl Toxicol, 2008, 28(1): 78-91.

- FANG J L, STINGLEY R L, BELAND F A, et al. Occurrence, efficacy, metabolism, and toxicity of triclosan [J]. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev, 2010, 28(3): 147-71.

- GEER L A, PYCKE B F G, WAXENBAUM J, et al. Association of birth outcomes with fetal exposure to parabens, triclosan and triclocarban in an immigrant population in Brooklyn, New York [J]. J Hazard Mater, 2017, 323(Pt A): 177-83.

- HIGASHIHARA N, SHIRAISHI K, MIYATA K, et al. Subacute oral toxicity study of bisphenol F based on the draft protocol for the “Enhanced OECD Test Guideline no. 407” [J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2007, 81(12): 825-32.

- ROCHESTER J R, BOLDEN A L. Bisphenol S and F: A Systematic Review and Comparison of the Hormonal Activity of Bisphenol A Substitutes [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2015, 123(7): 643-50.

- LEE S, LIU X, TAKEDA S, et al. Genotoxic potentials and related mechanisms of bisphenol A and other bisphenol compounds: A comparison study employing chicken DT40 cells [J]. Chemosphere, 2013, 93(2): 434-40.

- SONI M G, CARABIN I G, BURDOCK G A. Safety assessment of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) [J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 2005, 43(7): 985-1015.

- WITORSCH R J, THOMAS J A. Personal care products and endocrine disruption: A critical review of the literature [J]. Crit Rev Toxicol, 2010, 40 Suppl 3: 1-30.

- VO T T, YOO Y M, CHOI K C, et al. Potential estrogenic effect(s) of parabens at the prepubertal stage of a postnatal female rat model [J]. Reprod Toxicol, 2010, 29(3): 306-16.

- CHEN J, AHN K C, GEE N A, et al. Antiandrogenic properties of parabens and other phenolic containing small molecules in personal care products [J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2007, 221(3): 278-84.

- SHARIATIFAR N, DADGAR M, FAKHRI Y, et al. Levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in milk and milk powder samples and their likely risk assessment in Iranian population [J]. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2020, 85.

- WANG X, WANG M, WANG X, et al. A novel naphthalene carboxylic acid-based ionic liquid mixed disperser combined with ultrasonic-enhanced in-situ metathesis reaction for preconcentration of triclosan and methyltriclosan in milk and eggs [J]. Ultrason Sonochem, 2018, 47: 57-67.

- YAO L, LV Y Z, ZHANG L J, et al. Determination of 24 personal care products in fish bile using hybrid solvent precipitation and dispersive solid phase extraction cleanup with ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. J Chromatogr A, 2018, 1551: 29-40.

- WU H, WU L H, WANG F, et al. Several environmental endocrine disruptors in beverages from South China: occurrence and human exposure [J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2019, 26(6): 5873-84.

- ZAPATA N I, PEñUELA G A. Modified QuEChERS/UPLC-MS/MS method to monitor triclosan, ibuprofen, and diclofenac in fish Pseudoplatystoma magdaleniatum [J]. Food Analytical Methods, 2021, 14(6): 1289-304.

- GENTILI A, MARCHESE S, PERRET D. MS techniques for analyzing phenols, their metabolites and transformation products of environmental interest [J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2008, 27(10): 888-903.

- MANAV Ö G, DINç-ZOR Ş, ALPDOĞAN G. Optimization of a modified QuEChERS method by means of experimental design for multiresidue determination of pesticides in milk and dairy products by GC–MS [J]. Microchemical Journal, 2019, 144: 124-9.

- BEMRAH N, JEAN J, RIVIERE G, et al. Assessment of dietary exposure to bisphenol A in the French population with a special focus on risk characterisation for pregnant French women [J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 2014, 72: 90-7.

- HAN L, MATARRITA J, SAPOZHNIKOVA Y, et al. Evaluation of a recent product to remove lipids and other matrix co-extractives in the analysis of pesticide residues and environmental contaminants in foods [J]. J Chromatogr A, 2016, 1449: 17-29.

- FISHER M, MACPHERSON S, BRAUN J M, et al. Paraben Concentrations in Maternal Urine and Breast Milk and Its Association with Personal Care Product Use [J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2017, 51(7): 4009-17.

- MADEJ K, KALENIK T K, PIEKOSZEWSKI W. Sample preparation and determination of pesticides in fat-containing foods [J]. Food Chem, 2018, 269: 527-41.

- YANG Y, LU L, ZHANG J, et al. Simultaneous determination of seven bisphenols in environmental water and solid samples by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry [J]. J Chromatogr A, 2014, 1328: 26-34.

- AZZOUZ A, RASCON A J, BALLESTEROS E. Simultaneous determination of parabens, alkylphenols, phenylphenols, bisphenol A and triclosan in human urine, blood and breast milk by continuous solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2016, 119: 16-26.

- SHAMSIPUR M, YAZDANFAR N, GHAMBARIAN M. Combination of solid-phase extraction with dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction followed by GC-MS for determination of pesticide residues from water, milk, honey and fruit juice [J]. Food Chem, 2016, 204: 289-97.

- CHIRANI M R, KOWSARI E, TEYMOURIAN T, et al. Environmental impact of increased soap consumption during COVID-19 pandemic: Biodegradable soap production and sustainable packaging [J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 796.

- SIDOR A, RZYMSKI P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland [J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(6).

- ZHANG Y Q, LI H, WU H H, et al. The 5th national survey on the physical growth and development of children in the nine cities of China: Anthropometric measurements of Chinese children under 7 years in 2015 [J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2017, 163(3): 497-509.

- ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY. Human health risk assessment protocol, chapter 7:characterizing risk and hazard. US EPA archive document [J].

- Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) related to para hydroxybenzoates (E 214-219) [J]. EFSA Journal, 2004, 2(9).

- MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. Incoporation of human equivalent dose calculations into derivation of oral reference doses. MDH Health Risk Assessment Methods [J].

- ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY. Recommendations for and documentation of biological values for use in risk assessment [J]. 2011.

- HEALTH M D O. Toxicological summary for triclosan. Human health-based water guidance table [J]. 2015.

- HEALTH M D O. Toxicological summary for triclocarban. Human health-based water guidance table [J]. 2013.

- CHEN M L, CHEN C H, HUANG Y F, et al. Cumulative Dietary Risk Assessment of Benzophenone-Type Photoinitiators from Packaged Foodstuffs [J]. Foods, 2022, 11(2).

- BOBERG J, TAXVIG C, CHRISTIANSEN S, et al. Possible endocrine disrupting effects of parabens and their metabolites [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2010, 30(2): 301-12.

- LEMINI C, R J, M A E A V, et al. In vivo and in vitro estrogen bioactivities of alkyl parabens [J]. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 2003, 19: 69-79.

- WEI F, MORTIMER M, CHENG H, et al. Parabens as chemicals of emerging concern in the environment and humans: A review [J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 778.

- BEREKETOGLU C, PRADHAN A. Comparative transcriptional analysis of methylparaben and propylparaben in zebrafish [J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2019, 671: 129-39.

- LI M, ZHOU S, WU Y, et al. Prenatal exposure to propylparaben at human-relevant doses accelerates ovarian aging in adult mice [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 285.

- <312.pdf> [J].

- TAN J, KUANG H, WANG C, et al. Human exposure and health risk assessment of an increasingly used antibacterial alternative in personal care products: Chloroxylenol [J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 786.

- FREIRE C, MOLINA-MOLINA J-M, IRIBARNE-DURáN L M, et al. Concentrations of bisphenol A and parabens in socks for infants and young children in Spain and their hormone-like activities [J]. Environ Int, 2019, 127: 592-600.

| Analyte | TCS | TCC | MTCS | BPF | 4HBP | MeP | PrP | |

| Linear range (μg L-1) | 200-1500 | 25-500 | 500-3000 | 200-3000 | 50-1000 | 10-2000 | 50-1000 | |

| Correlation coefficient R2 |

0.9995 |

0.9996 |

0.9991 |

0.9996 |

0.9994 |

0.9999 |

0.9994 |

|

| Limit of detection (μg L-1) |

55 |

8 |

127 |

43 |

15 |

10 |

11 |

|

| Limit of quantification (μg L-1) |

184 |

25 |

422 |

143 |

50 |

36 |

38 |

|

| Standard recovery(%) | Low spiked level |

96.82 |

98.90 |

90.02 |

89.70 |

99.52 |

98.27 |

98.99 |

| Mean spiked level |

100.4 |

98.31 |

97.59 |

95.81 |

95.77 |

94.44 |

100.7 |

|

| High spiked level |

100.2 |

102.2 |

95.98 |

98.48 |

100.0 |

97.54 |

94.11 |

|

| Relative standard deviation(n=9)(%) |

1.7-2.2 |

1.3-2.8 |

1.1-2.7 |

1.4-3.2 |

1.8-3.9 |

1.3-3.4 |

1.2-2.4 |

|

| Inter-day variability(n=6)(%) |

0.8 |

1.5 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

1.6 |

|

| intra-day variability(n=6)(%) |

1.2 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

| Nectar source | Detection rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

|

TCS |

acacia honey | 44.44 | NDa-<LOQb |

| jujube honey | 50 | ND-<LOQ | |

| vitex honey | 0 | ND | |

| linden flower | 50 | ND-144.6 | |

| rape flower honey | 33.33 | ND-121 | |

| citrus honey | 66.67 | ND-<LOQ | |

| loquat honey | 0 | ND | |

| multifloral honey | 15.38 | ND-<LOQ | |

| sunflower honey | 0 | ND | |

| motherwort honey | 0 | ND | |

| wolfberry honey | 50 | ND-<LOQ | |

| milk vetch honey | 0 | ND |

| Nectar source | Detection rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| TCC | acacia honey | 33.33(3/9) | ND-<LOQ |

| jujube honey | 25(1/4) | ND-<LOQ | |

| vitex honey | 0(0/3) | ND | |

| linden flower | 0(0/4) | ND | |

| rape flower honey | 0(0/3) | ND | |

| citrus honey | 0(0/3) | ND | |

| loquat honey | 0(0/1) | ND | |

| multifloral honey | 15.38(2/13) | ND-<LOQ | |

| sunflower honey | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| motherwort honey | 100(1/1) | <LOQ | |

| wolfberry honey | 50(1/2) | ND-<LOQ | |

| milk vetch honey | 0(0/1) | ND |

| Nectar source | Detection rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| BPF | acacia honey | 88.89(8/9) | ND-612.5 |

| jujube honey | 100(4/4) | 232.1-642.4 | |

| vitex honey | 100(3/3) | 224.7-415.2 | |

| linden flower | 100(4/4) | <LOQ-593.7 | |

| rape flower honey | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-297.9 | |

| citrus honey | 100(3/3) | 190.7-376.7 | |

| loquat honey | 100(1/1) | 150.8 | |

| multifloral honey | 100(13/13) | <LOQ-1193 | |

| sunflower honey | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-189 | |

| motherwort honey | 100(1/1) | 154.6 | |

| wolfberry honey | 100(2/2) | <LOQ | |

| milk vetch honey | 100(1/1) | 578.2 |

| Nectar source | Detection rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| MeP | acacia honey | 100(9/9) | <LOQ-176.9 |

| jujube honey | 50(2/4) | ND-64.86 | |

| vitex honey | 100(3/3) | <LOQ | |

| linden flower | 75(3/4) | ND-249.7 | |

| rape flower honey | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-149.5 | |

| citrus honey | 100(3/3) | 89.65-299.2 | |

| loquat honey | 100(1/1) | <LOQ | |

| multifloral honey | 69.23(9/13) | ND-320.9 | |

| sunflower honey | 66.67(2/3) | ND-70.02 | |

| motherwort honey | 100(1/1) | 40.52 | |

| wolfberry honey | 100(2/2) | 54.34-72.19 | |

| milk vetch honey | 100(1/1) | 439.5 | |

| PrP | acacia honey | 100(9/9) | <LOQ-109.3 |

| jujube honey | 75(3/4) | ND-<LOQ | |

| vitex honey | 33.33(1/3) | <LOQ | |

| linden flower | 75(3/4) | ND-<LOQ | |

| rape flower honey | 66.67(2/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| citrus honey | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-56.86 | |

| loquat honey | 100(1/1) | <LOQ | |

| multifloral honey | 69.23(9/13) | ND-136.7 | |

| sunflower honey | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-39.42 | |

| motherwort honey | 100(1/1) | <LOQ | |

| wolfberry honey | 100(2/2) | <LOQ-120.3 | |

| milk vetch honey | 100(1/1) | <LOQ |

| Packaging material | Detetion rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| TCS | PET | 28.57(8/28) | ND-144.6 |

| PP | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| laminated polymer/foil pouches | 0(0/5) | ND | |

| glass bottles with plastic lids | 42.86(3/7) | ND-<LOQ | |

| glass bottles with polymer lined metal lids | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| all-glass bottle | 100(1/1) | <LOQ | |

| TCC | PET | 17.86(5/28) | ND-<LOQ |

| PP | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| laminated polymer/foil pouches | 20(1/5) | ND-<LOQ | |

| glass bottles with plastic lids | 14.28(1/7) | ND-<LOQ | |

| glass bottles with polymer lined metal lids | 33.33(1/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| all-glass bottle | 0(0/1) | ND |

| Packaging material | Detetion rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| BPF | PET | 96.43(27/28) | ND-1193 |

| PP | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-199.3 | |

| laminated polymer/foil pouches | 100(5/5) | <LOQ-580.4 | |

| glass bottles with plastic lids | 100(7/7) | ND-612.5 | |

| glass bottles with polymer lined metal lids | 100(3/3) | <LOQ-479.8 | |

| all-glass bottle | 100(1/1) | 234.5 |

| Packaging material | Detetion rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| 4HBP | PET | 32.14(9/28) | ND-172.3 |

| PP | 33.33(1/3) | ND-50.62 | |

| laminated polymer/foil pouches | 40(2/5) | ND-294.9 | |

| glass bottles with plastic lids | 57.14(4/7) | ND-72.37 | |

| glass bottles with polymer lined metal lids | 33.33(1/3) | ND-94.43 | |

| all-glass bottle | 0(0/1) | ND |

| Packaging material | Detetion rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | |

| MeP | PET | 82.14(23/28) | ND-439.5 |

| PP | 100(3/3) | 37.2-61.3 | |

| laminated polymer/foil pouches | 80(4/5) | ND-320.9 | |

| glass bottles with plastic lids | 71.43(5/7) | ND-176.9 | |

| glass bottles with polymer lined metal lids | 100(3/3) | 64.86-299.2 | |

| all-glass bottle | 100(1/1) | 179.8 | |

| PrP | PET | 85.71(24/28) | ND-136.7 |

| PP | 66.67(2/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| laminated polymer/foil pouches | 80(4/5) | ND-45.12 | |

| glass bottles with plastic lids | 71.42(5/7) | ND-109.3 | |

| glass bottles with polymer lined metal lids | 100(3/3) | ND-<LOQ | |

| all-glass bottle | 0(0/1) | ND |

| Place of origin | EDCs | Detetion rate(%) | Range(μg/kg) | Geometric mean concentration(μg/kg) |

| China | TCS | 27.5(11/40) | ND-144.6 | 3.14 |

| TCC | 20.0(8/40) | ND-<LOQ | 1.44 | |

| MTCS | 0(0/40) | ND | ND | |

| BPF | 97.5(39/40) | ND-642.4 | 144.9 | |

| 4HBP | 32.5(13/40) | ND-294.9 | 3.32 | |

| MeP | 82.5(33/40) | ND-439.5 | 27.39 | |

| PrP | 85.0(34/40) | ND-120.3 | 10 | |

| Abroad | TCS | 42.86(3/7) | ND-<LOQ | 5.57 |

| TCC | 14.28(1/7) | ND-<LOQ | 1.34 | |

| MTCS | 0(0/7) | ND | ND | |

| BPF | 100(7/7) | 187.6-1193 | 527.1 | |

| 4HBP | 57.14(4/7) | ND-99.32 | 12.89 | |

| MeP | 85.71(6/7) | ND-320.9 | 56.19 | |

| PrP | 57.14(4/7) | ND-136.7 | 17.80 |

| EDCs | Maximum detectable concentration(μg/kg) |

RfD (ng/kg bw/d) |

EDI (ng/kg bw/d) |

HQ | Reference measurementsa and uncertainty factors |

| TCS | 144.6 | 1.3×104 | 28.92 | 2.2×10-3 | HED derived from mature rats: 4.0 × 106 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBUb) |

| TCC | 8 | 1.3×104 | 1.60 | 1.2×10-4 | HED derived from mature rats: 4.0 × 106 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBUb) |

| BPF | 1193 | 1.1×104 | 238.6 | 2.2×10-2 | HED derived from mature rats: 3.2 × 106 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBUb) |

| 4HBP | 294.9 | 5.3×104 | 58.98 | 1.1×10-3 | HED derived from mature rats: 1.6 × 107 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBUb) |

| MeP | 439.5 | 1.0×107 | 87.90 | 8.79×10-6 | EDI: 1.0 × 107 ng/kg bw/day for total MeP and EtP |

| PrP | 136.7 | 1.77×102 | 27.34 | 0.15 | HED derived from immature mice: 5.3 × 105 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBUb) × 10 (for adults) |

| EDCs | Intake(ng/kg bw/day) | RfD | Reference measurementsa and uncertainty factors | |||||

| 0-1month | 1-4months | 4-6months | 6-12months | 12-24months | 24-36months | |||

| TCS | 290.4 | 186.1 | 166.4 | 140.9 | 111.4 | 93.71 | 1.3×103 | HED derived from mature rats: 4.0 × 106 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBUb) × 10 (for infants) |

| TCC | 16.06 | 10.30 | 9.2 | 7.80 | 6.16 | 5.18 | 1.3×103 | HED derived from mature rats: 4.0 × 106 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBU) × 10 (for infants) |

| BPF | 2395.6 | 1535.4 | 1372.8 | 1162.8 | 919.1 | 773.2 | 1.1×103 | HED derived from mature rats: 3.2 × 106 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBU) × 10 (for infants) |

| 4HBP | 592.2 | 379.5 | 339.4 | 287.4 | 227.2 | 191.1 | 5.3×103 | HED derived from mature rats: 1.6 × 107 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBU) × 10 (for infants) |

| MeP | 882.5 | 565.6 | 505.8 | 428.4 | 338.6 | 284.8 | 1×106 | EDI: 1.0 × 107 ng/kg bw/day for total MeP and EtP Uncertainty factor for infants:10 |

| PrP | 274.5 | 175.9 | 157.3 | 133.2 | 105.3 | 88.59 | 1.8×103 | HED derived from immature mice: 5.3 × 105 ng/kg bw/day Uncertainty factor for infants: 3 (inter-) × 10 (intraspecies) × 10 (DBU) |

| EDCs | HQ | |||||

| 0-1month | 1-4months | 4-6months | 6-12months | 12-24months | 24-36months | |

| TCS | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.085 | 0.072 |

| TCC | 1.2×10-2 | 7.9×10-3 | 7.1×10-3 | 6×10-3 | 4.7×10-3 | 4.0×10-3 |

| BPF | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.84 | 0.70 |

| 4HBP | 0.11 | 7.2×10-2 | 6.4×10-2 | 5.4×10-2 | 4.3×10-2 | 3.6×10-2 |

| MeP | 8.8×10-4 | 5.6×10-4 | 5.0×10-4 | 4.3×10-4 | 3.4×10-4 | 2.8×10-4 |

| PrP | 0.15 | 0.1 | 8.7×10-2 | 7.4×10-2 | 5.8×10-2 | 4.9×10-2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).