Submitted:

29 March 2024

Posted:

01 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

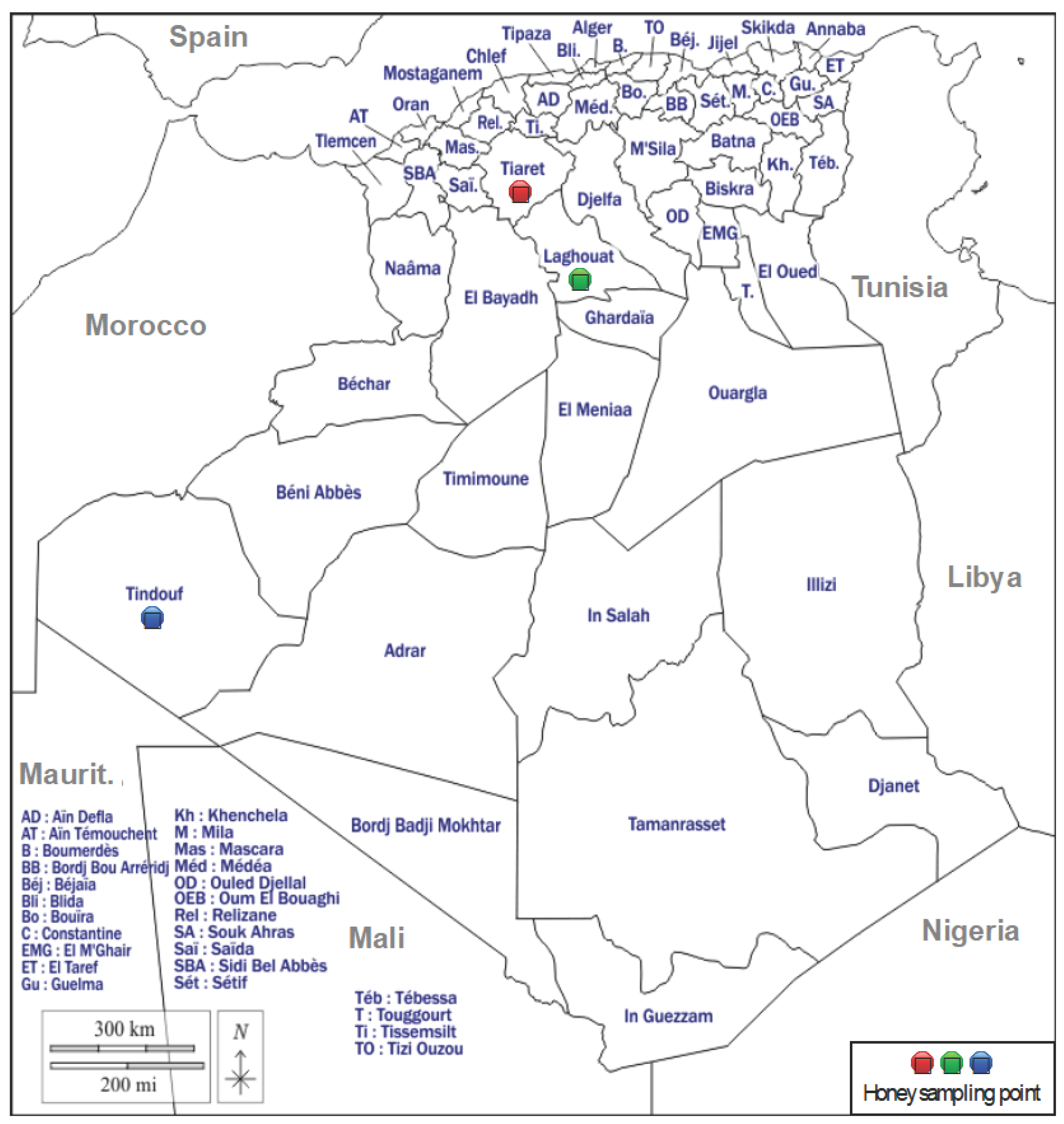

2.1. Honey Sample Collection

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Physicochemical Parameters

2.4. Pesticide, PCB, and PAH Residues

2.5. PAEs and NPPs Residues

2.6. BPs Residues

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Assessment of the Dietary Exposure to Contaminants

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters

| Moisture (%) |

TTS (°Brix) |

Conductivity (µS/cm) | pH | Free acidity (meq/Kg) | Combined acidity (meq/Kg) | Total acidity (meq/Kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | 14.51 ± 1.59a,b,c,d | 81.25 ± 1.30 | 490.65 ± 24.47a,b | 4.26 ± 0.07a,b | 46.67 ± 0.99a,e,f | 0.86 ± 0.03a | 47.54 ± 0.97a,d |

| ET | 14.39 ± 0.13a,b,c,d | 84.65 ± 1.32 | 468.55 ± 7.56a,b | 4.37 ± 0.09a,b | 29.54 ± 0.64b,c | 0.87 ± 0.02a | 30.31 ± 0.64b,e,c |

| EST | 14.15 ± 0.16a,b,c,d | 82.36 ± 1.58 | 326.94 ± 6.77a,c | 4.30 ± 0.02a,b | 41.84 ± 0.97a,d,e | 0.86 ± 0.02a | 42.71 ± 0.96a,c,d |

| ZLT | 13.66 ± 0.20a,b,c | 84.09 ± 1.30 | 525.79 ±7 .74a,b | 4.65 ± 0.07b,d | 26.37 ± 0.73b,c | 0.88 ± 0.03a | 27.25 ± 0.74b,e |

| BMT | 16.55 ± 0.13d | 82.22 ± 1.36 | 439.15 ± 5.55a,b,c | 4.40 ± 0.06a,b | 34.12 ± 0.75b,d | 4.18 ± 0.04b | 38.30 ± 0.71a,b |

| TEL | 16.15 ± 0.08a,b,d | 81.89 ± 1.43 | 565.43 ± 8.10b,e | 4.41 ± 0.04a,b | 38.09 ± 0.64a,b,d | 0.84 ± 0.02a | 38.93 ± 0.63a,b |

| EOL | 14.12 ± 0.76a,b,c | 83.65 ± 1.29 | 544.96 ± 187.42b | 4.50 ± 0.09b,f | 29.80 ± 7.23d | 2.12 ± 0.07c | 31.92 ± 7.16b,g |

| EGL | 12.51 ± 0.20c | 84.91 ± 1.61 | 471.05 ± 6.33a,b | 4.39 ± 0.10a,b,c | 42.11 ± 0.46a,d,e | 5.23 ± 0.03d | 47.34 ± 0.43a,d,f |

| ML | 14.03 ± 0.17b,c,d | 83.07 ± 1.47 | 428.21 ± 5.79a,b,c | 4.50 ± 0.11a,b | 31.27 ± 0.50b,d | 4.89 ± 0.03d | 36.16 ± 0.47b,c,f,g |

| ZL | 13.16 ± 0.54c | 84.53 ± 1.24 | 471.75 ± 44.76a,b | 4.86 ± 0.07b | 20.10 ± 2.26c | 2.85 ± 0.33e | 22.95 ± 2.57e |

| ED | 13.93 ± 0.12a,c | 83.19 ± 1.16 | 330.28 ± 5.03a,c | 3.97 ± 0.05a,c,e | 42.33 ± 0.60d,e | 2.57 ± 0.04e | 44.90 ± 0.60a,d,f |

| ESD | 15.34 ± 0.98a,b,d | 82.08 ± 1.91 | 241.48 ± 7.04c | 3.61 ± 0.43e | 30.73 ± 5.99b | 0.86 ± 0.02a | 31.58 ± 5.98b,g |

| EOD | 13.79 ±0.20a,c | 82.57 ± 1.02 | 337.07 ± 6.78a,c,e | 3.93 ± 0.04a,e | 52.96 ± 0.58e | 0.86 ± 0.01a | 53.82 ± 0.57d |

| PHD | 12.32 ± 0.09c | 81.97 ± 1.34 | 376.50 ± 9.07a,b,c | 4.08 ± 0.07a,d,e,f | 37.34 ± 0.52b,d,f | 1.74 ± 0.04f | 39.08 ± 0.55a,g |

| p-Value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

3.2. Pesticide, PCB, and PAH Residues

| Analyte (µg/Kg) |

Tiaret | Laghouat | Tindouf | p-Value | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | ET | EST | ZLT | BMT | TEL | EOL | EGL | ML | ZL | ED | ESD | EOD | PHD | ||||

| Bendiocarb | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.20 ±0 .02 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| Carbaryl | 0.94 ± 0.42a | 7.61 ± 0.61b,e | <LOQ | 1.39 ± 0.17a,d | 1.18 ± 0.13a,d | 0.62 ± 0.06a,d | 1.08 ± 1.14a | 9.46 ± 0.87b | 0.67 ±0.06a,d | 1.49 ± 0.92a,d | 15.81 ± 1.48c | 3.91 ± 4.25a,e | 6.20 ± 0.68b,d,e | 4.51 ± 0.47a,b | <0.01 | ||

| Furathiocarb | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 2.15 ± 0.27 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 2.35 ± 2.57 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.89 | ||

| Metalaxyl-M | 0.42 ± 0.10a,b,e | 0.31 ± 0.04b | 0.32 ± 0.02a,b | 0.63 ± 0.07c,e | 1.10 ± 0.09d,f | 0.78 ± 0.08c | 1.26 ± 0.13d | 0.84 ± 0.05c,f | 0.75 ± 0.08c | 0.46 ± 0.08a,b,e | 0.30 ± 0.03a,b | 0.34 ± 0.03a,b | 0.79 ± 0.08c | 0.27 ± 0.02a,b | <0.01 | ||

| Quintozen | <LOQ | 0.35 ± 0.04a | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 4.86 ± 0.57b | 0.37 ±0.03a | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| Methabenzthiazuron | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.27 ± 0.02 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.35 ± 0.36 | 0.82 ±0.08 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.06 | ||

| Propazine | 1.18 ± 1.28 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 1.93 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 1.28 ± 0.15 | <LOQ | 0.42 ± 0.04 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.30 ±0.29 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| Propyzamide | <LOQ | 0.12 ± 0.02 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| Simazide | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.69 ±0.05 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.31 ± 0.21 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.07 | ||

| Cyromazine | 103.60 ± 94.12a,d,c | 40.28 ± 4.37a,b,d | 16.16 ± 1.54a,b | 50.63 ± 4.48a,b,c | 163.58 ± 16.20c | 55.90 ± 5.48a,b,c | 123.08 ± 9.66c,d,f | 10.32 ± 1.33a,b | 58.38 ± 4.39a,b,c | 12.77 ± 14.02b,e | 0.30 ± 0.04b,e | 43.21 ± 16.24a,b,e,f | 6.48 ± 0.68a,e | 9.94 ± 0.92a,e | <0.01 | ||

| Pyriproxyfen | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 3.82 ±0.36 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| Alachlor | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.15 ±0.03a,c | 0.54 ±0.05a,b,c | 0.14 ± 0.02a | 0.58 ± 0.25c | 0.36 ± 0.03a,b,c | 0.76 ± 0.06b | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| Methidathion | <LOQ | 0.22 ± 0.03 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| Omethoate | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 4.82 ± 0.44a | <LOQ | 11.55 ± 12.64a,b | 13.52 ± 1.12a,b | <LOQ | <LOQ | 14.56 ± 1.34a,b | 2.87 ± 3.10a | 4.24 ± 0.38a | 27.54 ± 2.44b | <0.01 | ||

| Carbophenothion | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.43 ± 0.48 | 0.95 ± 0.09 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.11 | ||

| cis-Permethrin | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.48 ±0.03 | 0.29 ±0.29 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.44 ± 0.04 | <LOQ | 0.44 | ||

| Acenaphthylene | 0.25 ± 0.25a | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.20 ± 0.05a | 0.36 ± 0.36a,b | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.82 ± 0.08b | 0.22 ± 0.02a,b | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| Anthracene | <LOQ | 1.23 ± 0.19a,c | <LOQ | 0.38 ± 0.02b,d | 0.36 ± 0.03b,d | <LOQ | 0.23 ± 0.22b | 1.55 ± 0.17c | 0.53 ± 0.07b | <LOQ | 0.91 ± 0.09a,b | 0.28 ± 0.28b | 0.46 ± 0.04b,d | 0.48 ± 0.07b,d | <0.01 | ||

| Benzo[a]ntracene | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.24 ± 0.23 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 1.60 ± 1.40 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.04 | ||

| Chrysene | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.11 ± 0.09 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 7.39 ± 8.02 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.04 | ||

| Fluorene | 1.33 ± 1.45a | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.20 ± 0.01a | 1.44 ± 0.09a | 1.81 ± 0.14a | 0.35 ± 0.37a | 5.73 ± 0.93b | 1.56 ± 0.10a | <LOQ | 0.28 ± 0.04a | 0.17 ±0.16a | 0.30 ± 0.03a | 0.26 ± 0.03a | <0.01 | ||

| Phenantrene | <LOQ | 1.16 ± 0.14a | <LOQ | 0.22 ± 0.02b | 0.25 ± 0.03b | <LOQ | 0.30 ± 0.28b | 2.33 ± 0.39c | 0.40 ± 0.07b | <LOQ | 0.43 ±0.04b | 0.24 ± 0.24b | 0.29 ± 0.03b | 0.19 ± 0.02b | <0.01 | ||

| PCB 77 | <LOQ | 0.48 ± 0.04 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| PCB 126 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | <LOQ | 0.09 | ||

| PCB 138 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 1.59 ± 0.16 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| PCB 153 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.28 ± 0.05a | 4.67 ± 0.41b | 0.23 ± 0.03a | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| PCB 180 | 0.28 ± 0.05a,b | 0.37 ± 0.03a | 0.17 ± 0.02a,b | <LOQ | 0.25 ± 0.03a,b | 0.14 ± 0.01a,b | 0.36 ± 0.04a | 0.27 ± 0.02a,b | 0.22 ± 0.03a,b | 0.17 ± 0.04b | <LOQ | 0.13 ± 0.13b | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| PCB 189 | 0.29 ± 0.06a,b | 0.43 ± 0.04b | 0.17 ± 0.02a,c | <LOQ | 0.16 ± 0.01a,c | 0.12 ± 0.02c | 0.18 ± 0.02a,c | 0.16 ± 0.02a,c | 0.14 ± 0.01a,c | 0.14 ± 0.11c | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

3.3. Plasticizers and BPs

| Analyte (mg/Kg) |

Tiaret | Laghouat | Tindouf | p-Value | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | ET | EST | ZLT | BMT | TEL | EOL | EGL | ML | ZL | ED | ESD | EOD | PHD | ||||

| DEP | 0.014 ± 0.014 | <LOQ | 0.038 ± 0.012 | 0.023 ± 0.006 | 0.034 ± 0.013 | 0.026 ± 0.009 | 0.013 ± 0.013 | 0.021 ± 0.002 | <LOQ | 1.656 ± 1.808 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.02 | ||

| DPrp | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.016 ± 0.016 | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| DBP | 0.048 ± 0.006a | 0.073 ± 0.005b,c | 0.097 ± 0.007b | 0.038 ± 0.007a,c | 0.042 ± 0.006a,c | 0.037 ± 0.006a,c | 0.037 ± 0.005a | 0.041 ± 0.006a,c | <LOQ | 0.041 ± 0.006a | 0.048 ± 0.005a,c | 0.055 ± 0.014b,c | 0.037 ± 0.003a,c | 0.044 ± 0.004a,c | <0.01 | ||

| DiBP | 0.036 ± 0.005a | 0.070 ± 0.009a,c | 0.042 ± 0.006a,d | 0.040 ± 0.006a,d | 0.050 ± 0.007a,d | 0.039 ± 0.006a,d | 0.052 ± 0.010a,d | 0.063 ± 0.006c,d | 0.040 ± 0.008a,d | 0.058 ± 0.023a,d | 0.266 ± 0.032b | 0.175 ± 0.141b,c,d | 0.194 ± 0.021b,c,d | 0.232 ± 0.027b,c | <0.01 | ||

| BBP | <LOQ | 0.041 ± 0.006 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.115 ±0.019 | 0.020 ± 0.020 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| DPhP | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.070 ± 0.012 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | - | ||

| DEHP | 0.050 ± 0.009a | 0.118 ± 0.012b | 0.045 ± 0.007a | 0.051 ± 0.004a | 0.053 ± 0.007a | 0.058 ± 0.004a | 0.048 ± 0.008a | 0.073 ± 0.007a | 0.049 ± 0.009a | 0.065 ± 0.024a | 0.070 ± 0.005a | 0.058 ± 0.013a | 0.068 ± 0.004a | 0.073 ± 0.008a | <0.01 | ||

| DEA | 0.100 ± 0.108a,b | 0.175 ± 0.025b | <LOQ | 0.027 ± 0.005a,b | 0.047 ± 0.009a,b | <LOQ | 0.068 ± 0.037a,b | 0.033 ± 0.006a,b | 0.046 ± 0.008a,b | 0.013 ± 0.013a | <LOQ | 0.020 ± 0.021a | <LOQ | <LOQ | <0.01 | ||

| DEHT | 0.042 ± 0.012a | 0.128 ± 0.019a,b | 0.038 ± 0.009a,b | 0.048 ± 0.009a,b | 0.139 ± 0.015b | 0.103 ± 0.021a,b | 0.053 ± 0.018a,b | 0.144 ± 0.017a,b | 0.055 ± 0.012a,b | 0.102 ± 0.077a,b | 0.108 ± 0.008a,b | 0.076 ± 0.033a,b | 0.094 ± 0.013a,b | 0.089 ± 0.014a,b | <0.01 | ||

3.4. Dietary Exposure to Contaminants

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brar, D.S.; Pant, K.; Krishnan, R.; Kaur, S.; Rasane, P.; Nanda, V.; Saxena, S.; Gautam, S. A Comprehensive Review on Unethical Honey: Validation by Emerging Techniques. Food Control 2023, 145, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzo, S.; Mulè, F.; Amato, A. Honey and Obesity-Related Dysfunctions: A Summary on Health Benefits. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 82, 108401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bella, G.; Potortì, A.G.; Beltifa, A.; Ben Mansour, H.; Nava, V.; Lo Turco, V. Discrimination of Tunisian Honey by Mineral and Trace Element Chemometrics Profiling. Foods 2021, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kędzierska-Matysek, M.; Teter, A.; Skałecki, P.; Topyła, B.; Domaradzki, P.; Poleszak, E.; Florek, M. Residues of Pesticides and Heavy Metals in Polish Varietal Honey. Foods 2022, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.M.; Tran, L.; McKee, C.G.; Ortega Polo, R.; Newman, T.; Lansing, L.; Griffiths, J.S.; Bilodeau, G.J.; Rott, M.; Marta Guarna, M. Honey Bees as Biomonitors of Environmental Contaminants, Pathogens, and Climate Change. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 134, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panseri, S.; Bonerba, E.; Nobile, M.; Di Cesare, F.; Mosconi, G.; Cecati, F.; Arioli, F.; Tantillo, G.; Chiesa, L. Pesticides and Environmental Contaminants in Organic Honeys According to Their Different Productive Areas toward Food Safety Protection. Foods 2020, 9, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on Maximum Residue Levels of Pesticides in or on Food and Feed of Plant and Animal Origin and Amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC Text with EEA Relevance.; 2005; Vol. 070.

- Nagar, N.; Saxena, H.; Pathak, A.; Mishra, A.; Poluri, K.M. A Review on Structural Mechanisms of Protein-Persistent Organic Pollutant (POP) Interactions. Chemosphere 2023, 332, 138877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, O.M.L.; Basheer, A.A.; Khattab, R.A.; Ali, I. Health and Environmental Effects of Persistent Organic Pollutants. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 263, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockholm Convention on Peristent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Available online: https://chm.pops.int/theconvention/overview/textoftheconvention/tabid/2232/default.aspx (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Sampaio, G.R.; Guizellini, G.M.; da Silva, S.A.; de Almeida, A.P.; Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.C.; Rogero, M.M.; de Camargo, A.C.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Foods: Biological Effects, Legislation, Occurrence, Analytical Methods, and Strategies to Reduce Their Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, L.M.; Labella, G.F.; Giorgi, A.; Panseri, S.; Pavlovic, R.; Bonacci, S.; Arioli, F. The Occurrence of Pesticides and Persistent Organic Pollutants in Italian Organic Honeys from Different Productive Areas in Relation to Potential Environmental Pollution. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, M.; Di Bella, G.; Fede, M.R.; Lo Turco, V.; Potortì, A.G.; Rando, R.; Russo, M.T.; Dugo, G. Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Multi-Residual Analysis of Contaminants in Italian Honey Samples. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2017, 34, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Turco, V.; Di Bella, G.; Potortì, A.G.; Tropea, A.; Casale, E.K.; Fede, M.R.; Dugo, G. Determination of Plasticisers and BPA in Sicilian and Calabrian Nectar Honeys by Selected Ion Monitoring GC/MS. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2016, 33, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notardonato, I.; Passarella, S.; Ianiri, G.; Di Fiore, C.; Russo, M.V.; Avino, P. Analytical Method Development and Chemometric Approach for Evidencing Presence of Plasticizer Residues in Nectar Honey Samples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, G.; Jasrotia, A.; Raj, P.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, A.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S.; Kaur, R. Contamination of Water and Sediments of Harike Wetland with Phthalate Esters and Associated Risk Assessment. Water 2023, 15, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re-evaluation of the Risks to Public Health Related to the Presence of Bisphenol A (BPA) in Foodstuffs | EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/6857 (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Common EDCs and Where They Are Found. Available online: https://www.endocrine.org/topics/edc/what-edcs-are/common-edcs (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Metcalfe, C.D.; Bayen, S.; Desrosiers, M.; Muñoz, G.; Sauvé, S.; Yargeau, V. An Introduction to the Sources, Fate, Occurrence and Effects of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Released into the Environment. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homrani, M.; Escuredo, O.; Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Fatiha, D.; Mohammed, B.; Homrani, A.; Seijo, M.C. Botanical Origin, Pollen Profile, and Physicochemical Properties of Algerian Honey from Different Bioclimatic Areas. Foods 2020, 9, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamali̇, H.S.; Özkirim, A. Beekeeping Activities in Turkey and Algeria. Mellifera 2019, 19, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Guerzou, M.; Aouissi, H.A.; Guerzou, A.; Burlakovs, J.; Doumandji, S.; Krauklis, A.E. From the Beehives: Identification and Comparison of Physicochemical Properties of Algerian Honey. Resources 2021, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelmani, N.; Meddour, R. Phytoecology of the Atlas Pistachio (Pistacia Atlantica Sub Sp. Atlantica) in the Area of Laghouat (Algeria). Indian J. Ecol. 2023, 50, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Belkacem, N.; Maamar, B.; Berrabah, H.; Souddi, M.; Okkacha, H.; Nouar, A. Diversity and Floristic Composition of Djebel Nessara Region (Tiaret -Algeria). Biodivers. J. 2021, 12, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laallam, H.; Boughediri, L.; Bissati, S.; Menasria, T.; Mouzaoui, M.S.; Hadjadj, S.; Hammoudi, R.; Chenchouni, H. Modeling the Synergistic Antibacterial Effects of Honey Characteristics of Different Botanical Origins from the Sahara Desert of Algeria. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S.; Martin, P.; Lullmann, C. Harmonised Methods of the International Honey Commission. Swiss Bee Res. Cent. FAM Liebefeld 2002, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Massous, A.; Ouchbani, T.; Lo Turco, V.; Litrenta, F.; Nava, V.; Albergamo, A.; Potortì, A.G.; Di Bella, G. Monitoring Moroccan Honeys: Physicochemical Properties and Contamination Pattern. Foods 2023, 12, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotta, L.; Litrenta, F.; Lo Turco, V.; Potortì, A.G.; Lopreiato, V.; Nava, V.; Bionda, A.; Di Bella, G. Evaluation of Chemical Contaminants in Conventional and Unconventional Ragusana Provola Cheese. Foods 2022, 11, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potortì, A.G.; Litrenta, F.; Sgrò, B.; Di Bella, G.; Albergamo, A.; Ben Mansour, H.; Beltifa, A.; Benameur, Q.; Lo Turco, V. A Green Sample Preparation Method for the Determination of Bisphenols in Honeys. Green Anal. Chem. 2023, 5, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguebes, F.; Pat, L.; Ali, B.; Guerrero, A.; Córdova, A.V.; Abatal, M.; Garduza, J.P. Application of Multivariable Analysis and FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy to the Prediction of Properties in Campeche Honey. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016, 2016, e5427526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, M.E.; Pârvulescu, O.C.; Donise, A.C.; Dobre, T.; Stanciu, D.R. Characterization and Classification of Romanian Acacia Honey Based on Its Physicochemical Parameters and Chemometrics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council Directive 2001/110/EC of 20 December 2001 Relating to Honey; 2001; Vol. 010.

- Commission, C.A. Revised Codex Standard for Honey. Codex Stan 2001, 12, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M.; Ghildyal, R.; D’Cunha, N.M.; Gouws, C.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Naumovski, N. The Bioactive, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Physicochemical Properties of a Range of Commercially Available Australian Honeys. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, E.; Drużyńska, B.; Wołosiak, R. Determination of the Botanical Origin of Honeybee Honeys Based on the Analysis of Their Selected Physicochemical Parameters Coupled with Chemometric Assays. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliuc, D.; Dranca, F.; Ropciuc, S.; Oroian, M. Advanced Characterization of Monofloral Honeys from Romania. Agriculture 2022, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasaudi, S. The Antibacterial Activities of Honey. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliuc, D.; Oroian, M. Organic Acids and Physo-Chemical Parameters of Romanian Sunflower Honey. Food Environ. Saf. J. 2020, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorab, A.; Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Nakib, R.; Escuredo, O.; Haderbache, L.; Bekdouche, F.; Seijo, M.C. Sensorial, Melissopalynological and Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Honey from Babors Kabylia’s Region (Algeria). Foods 2021, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhloufi, C.; Ait Abderrahim, L.; Taibi, K. Characterization of Some Algerian Honeys Belonging to Different Botanical Origins Based on Their Physicochemical Properties. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Sci. 2021, 45, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.D.; Licata, P.; Potortì, A.G.; Crupi, R.; Nava, V.; Qada, B.; Rando, R.; Bartolomeo, G.; Dugo, G.; Turco, V.L. Mineral Content and Physico-Chemical Parameters of Honey from North Regions of Algeria. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 36, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 of 25 May 2011 Implementing Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards the List of Approved Active Substances Text with EEA Relevance; 2011; Vol. 153.

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 (Text with EEA Relevance). J Eur Union 2023, 119, 103–157.

- Bettiche, F.; Chaib, W.; Halfadji, A.; Mancer, H.; Bengouga, K.; Grunberger, O. The Human Health Problems of Authorized Agricultural Pesticides: The Algerian Case. Microb. Biosyst. 2021, 5, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebdoua, S.; Lazali, M.; Ounane, S.M.; Tellah, S.; Nabi, F.; Ounane, G. Evaluation of Pesticide Residues in Fruits and Vegetables from Algeria. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2017, 10, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaouar, Z.L.; Chefirat, B.; Saadi, R.; Djelad, S.; Rezk-Kallah, H. Pesticide Residues in Tomato Crops in Western Algeria. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2021, 14, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudani, N.; Belhamra, M.; Toumi, K. Pesticide Use and Risk Perceptions for Human Health and the Environment: A Case Study of Algerian Farmers. PONTE Int. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Murcia-Morales, M.; Heinzen, H.; Parrilla-Vázquez, P.; Gómez-Ramos, M. del M.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Presence and Distribution of Pesticides in Apicultural Products: A Critical Appraisal. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 146, 116506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfadji, A.; Touabet, A.; Portet-Koltalo, F.; Le Derf, F.; Merlet-Machour, N. Concentrations and Source Identification of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Agricultural, Urban/Residential, and Industrial Soils, East of Oran (Northwest Algeria). Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2019, 39, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panseri, S.; Catalano, A.; Giorgi, A.; Arioli, F.; Procopio, A.; Britti, D.; Chiesa, L.M. Occurrence of Pesticide Residues in Italian Honey from Different Areas in Relation to Its Potential Contamination Sources. Food Control 2014, 38, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarella, S.; Guerriero, E.; Quici, L.; Ianiri, G.; Cerasa, M.; Notardonato, I.; Protano, C.; Vitali, M.; Russo, M.V.; De Cristofaro, A.; et al. PAHs Presence and Source Apportionment in Honey Samples: Fingerprint Identification of Rural and Urban Contamination by Means of Chemometric Approach. Food Chem. 2022, 382, 132361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, M.F.; Esen, F. Concentration Levels and an Assessment of Human Health Risk of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Honey and Pollen. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 66913–66921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, C.; De Cristofaro, A.; Nuzzo, A.; Notardonato, I.; Ganassi, S.; Iafigliola, L.; Sardella, G.; Ciccone, M.; Nugnes, D.; Passarella, S.; et al. Biomonitoring of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Heavy Metals, and Plasticizers Residues: Role of Bees and Honey as Bioindicators of Environmental Contamination. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 44234–44250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/968 of 3 July 2020 Renewing the Approval of the Active Substance Pyriproxyfen in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market, and Amending the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 (Text with EEA Relevance); 2020; Vol. 213.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/617 of 5 May 2020 Renewing the Approval of the Active Substance Metalaxyl-M, and Restricting the Use of Seeds Treated with Plant Protection Products Containing It, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market, and Amending the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 (Text with EEA Relevance); 2020; Vol. 143.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/755 of 23 May 2018 Renewing the Approval of the Active Substance Propyzamide, as a Candidate for Substitution, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market, and Amending the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 (Text with EEA Relevance. ); 2018; Vol. 128.

- Conclusion regarding the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance carbaryl | EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/rn-80 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Report 2023: Pesticide Residues in Food: Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240090187 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Commission Directive 2009/77/EC of 1 July 2009 Amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC to Include Chlorsulfuron, Cyromazine, Dimethachlor, Etofenprox, Lufenuron, Penconazole, Tri-Allate and Triflusulfuron as Active Substances (Text with EEA Relevance); 2009.

- Review of the existing MRLs for N-methyl-carbamate insecticides | EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/3559 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Update of the Risk Assessment of Di-butylphthalate (DBP), Butyl-benzyl-phthalate (BBP), Bis(2-ethylhexyl)Phthalate (DEHP), Di-isononylphthalate (DINP) and Di-isodecylphthalate (DIDP) for Use in Food Contact Materials | EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/5838 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

| Code | N. of samples | Botanical origin | Geographical origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| MT | 6 | Multifloral | Tiaret |

| ET | 3 | Echinops | Tiaret |

| EST | 3 | Eruca sativa | Tiaret |

| ZLT | 3 | Ziziphus lotus | Tiaret |

| BMT | 3 | Bunium mauritanicum | Tiaret |

| TEL | 3 | Tamarix and Euphorbia orientalis | Laghouat |

| EOL | 6 | Euphorbia orientalis | Laghouat |

| EGL | 3 | Eucaliptus globulus | Laghouat |

| ML | 3 | Multifloral | Laghouat |

| ZL | 6 | Ziziphus lotus | Laghouat |

| ED | 3 | Echinops | Tindouf |

| ESD | 6 | Eruca sativa | Tindouf |

| EOD | 3 | Euphorbia orientalis | Tindouf |

| PHD | 3 | Peganum harmala | Tindouf |

| Total | 54 |

| Shimadzu GCMS-TQ8030 | Pesticides, PCBs and PAHs analysis | PAEs and NPPs analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Column | Supelco SLB-5ms (30 m x 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness of stationary phase) | |

| Carrier gas flow rate (He) | 0.50 mL/min | 0.65 mL/min |

| Program temperature | 60 °C for 1 min, 15 °C/min until 150 °C, 10 °C/min until 270 °C, 2°C/min until 300°C | 8°C/min until 190°C (5 min hold), 8°C/min until 240°C (5 min hold), 8°C/min until 315°C |

| Injector temperature | 250°C | |

| Injection volume | 1 µL | 1 µL |

| Injection mode | Splitless with 1:10 split ratio | Splitless with 1:15 split ratio |

| Ion source temperature | 230°C | 200 °C |

| Transferline temperature | 290°C | 250°C |

| Ionization mode | Electronic ionization (EI), 70 eV | |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Shimadzu UHPLC–MS/MS 8040 |

|---|---|

| Column | Phenomenex C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 𝜇m particle size) |

| Mobile phase | Water (A) and acetonitrile (B) |

| Elution gradient | 0 min, 20% B; 2 min, 40% B; 6 min, 90% B; 8 min, 20% B |

| Flow rate | 0.4 mL/min |

| Injection volume | 2 µL |

| Ionization mode | ESI negative, 10-40 eV |

| DL temperature | 250°C |

| CID gas | 230 KPa |

| Gas nebuliser | Nitrogen |

| Nitrogen flow | 3 L/min |

| Nitrogen pressure | 770 KPa |

| Collision gas | Argon |

| Algeria | Europe | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDImin | HQ | EDImax | HQ | EDImin | HQ | EDImax | HQ | ||

| Pesticides | |||||||||

| Bendiocarb* | 9.43 x 10-7 | <1 | 9.43 x 10-7 | <1 | 4.54 x 10-6 | <1 | 4.54 x 10-6 | <1 | |

| Carbaryl* | 2.92 x 10-6 | <1 | 7.45 x 10-5 | <1 | 1.41 x 10-5 | <1 | 3.59 x 10-4 | <1 | |

| Furathiocarb* | 1.01 x 10-5 | <1 | 1.10 x 10-5 | <1 | 4.88 x 10-5 | <1 | 5.32 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Metalaxyl-M* | 1.27 x 10-6 | <1 | 5.94 x 10-6 | <1 | 6.13 x 10-6 | <1 | 2.86 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Quintozen* | 1.65 x 10-6 | <1 | 2.29 x 10-5 | <1 | 7.95 x 10-6 | <1 | 1.10 x 10-4 | <1 | |

| Methabenzthiazuron* | 1.60 x 10-6 | <1 | 3.87 x 10-6 | <1 | 6.13 x 10-6 | <1 | 1.86 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Propazine* | 1.32 x 10-6 | <1 | 9.10 x 10-6 | <1 | 6.36 x 10-6 | <1 | 4.38 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Propyzamide* | 5.66 x 10-7 | <1 | 5.66 x 10-7 | <1 | 2.73 x 10-6 | <1 | 2.73 x 10-6 | <1 | |

| Simazide* | 1.37 x 10-6 | <1 | 3.25 x 10-6 | <1 | 6.59 x 10-6 | <1 | 1.57 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Cyromazine* | 1.41 x 10-6 | <1 | 7.71 x 10-4 | <1 | 6.81 x 10-6 | <1 | 3.72 x 10-3 | <1 | |

| Pyriproxyfen* | 1.80 x 10-5 | <1 | 1.80 x 10-5 | <1 | 8.68 x 10-5 | <1 | 8.68 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Alachlor* | 6.60 x 10-7 | <1 | 3.58 x 10-6 | <1 | 3.18 x 10-6 | <1 | 1.73 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Methidathion* | 1.04 x 10-6 | <1 | 1.04 x 10-6 | <1 | 5.00 x 10-6 | <1 | 5.00 x 10-6 | <1 | |

| Omethoate* | 1.34 x 10-5 | <1 | 1.30 x 10-4 | <1 | 6.45 x 10-5 | <1 | 6.26 x 10-4 | <1 | |

| Carbophenothion* | 2.03 x 10-6 | <1 | 4.48 x 10-6 | <1 | 9.77 x 10-6 | <1 | 2.16 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| cis-Permethrin* | 1.27 x 10-6 | <1 | 2.26 x 10-6 | <1 | 6.13 x 10-6 | <1 | 1.09 x 10-5 | <1 | |

| Plasticizers | |||||||||

| DEA** | 5.66 x 10-8 | - | 8.25 x 10-7 | - | 2.73 x 10-7 | - | 3.98 x 10-6 | - | |

| DEP** | 5.66 x 10-8 | <1 | 7.81 x 10-3 | <1 | 2.73 x 10-7 | <1 | 3.76 x 10-2 | <1 | |

| DPrp** | 7.07 x 10-8 | - | 7.07 x 10-8 | - | 3.41 x 10-7 | - | 3.41 x 10-7 | - | |

| DiBP** | 1.70 x 10-7 | - | 1.25 x 10-6 | - | 8.18 x 10-7 | - | 6.04 x 10-6 | - | |

| DBP** | 1.74 x 10-7 | <1 | 4.57 x 10-7 | <1 | 8.40 x 10-7 | <1 | 2.20 x 10-6 | <1 | |

| BBP** | 8.96 x 10-8 | - | 5.42 x 10-7 | - | 4.32 x 10-7 | - | 2.61 x 10-6 | - | |

| DEHP** | 2.12 x 10-7 | <1 | 5.56 x 10-7 | <1 | 1.02 x 10-6 | <1 | 2.68 x 10-6 | <1 | |

| DPhP** | 3.30 x 10-7 | - | 3.30 x 10-7 | - | 1.59 x 10-6 | - | 1.59 x 10-6 | - | |

| DEHT** | 1.79 x 10-7 | - | 6.79 x 10-7 | - | 8.63 x 10-7 | - | 3.27 x 10-6 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).