Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study examines the relationship between perceived authenticity, green consumerism, and behavioral intention within the context of heritage restaurants in Hail, Saudi Arabia. By integrating Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT) and the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) framework, the research explores how authenticity perceptions influence both cultural and gastronomic experiences and contribute to sustainable consumption behavior. The study also investigates the moderating role of consumer knowledge in enhancing green consumerism and its subsequent impact on behavioral intention to dine at heritage restaurants. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study first conducted content analysis on online reviews to identify key attributes that shape authenticity perceptions. Subsequently, a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was applied to survey data collected from 417 patrons of heritage restaurants in Hail. The findings confirm that perceived authenticity significantly enhances consumers' cultural and gastronomic experiences, which in turn fosters green consumerism and strengthens behavioral intention to visit authentic restaurants. Furthermore, green consumerism acts as a key mediator between authenticity, cultural experiences, and purchase intention. Consumer knowledge further moderates this relationship, amplifying the positive effect of green consumerism on behavioral intention. The study contributes to the growing literature on sustainable gastronomy tourism by demonstrating the crucial interplay between authenticity, sustainability, and consumer knowledge in the heritage restaurant sector. It also offers practical recommendations for restaurant managers, policymakers, and tourism marketers to enhance the authentic dining experience while promoting environmentally responsible behavior. By fostering awareness of cultural and environmental values, heritage restaurants can play a pivotal role in advancing sustainable tourism development in Hail and beyond.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Authentic Gastronomic Experience

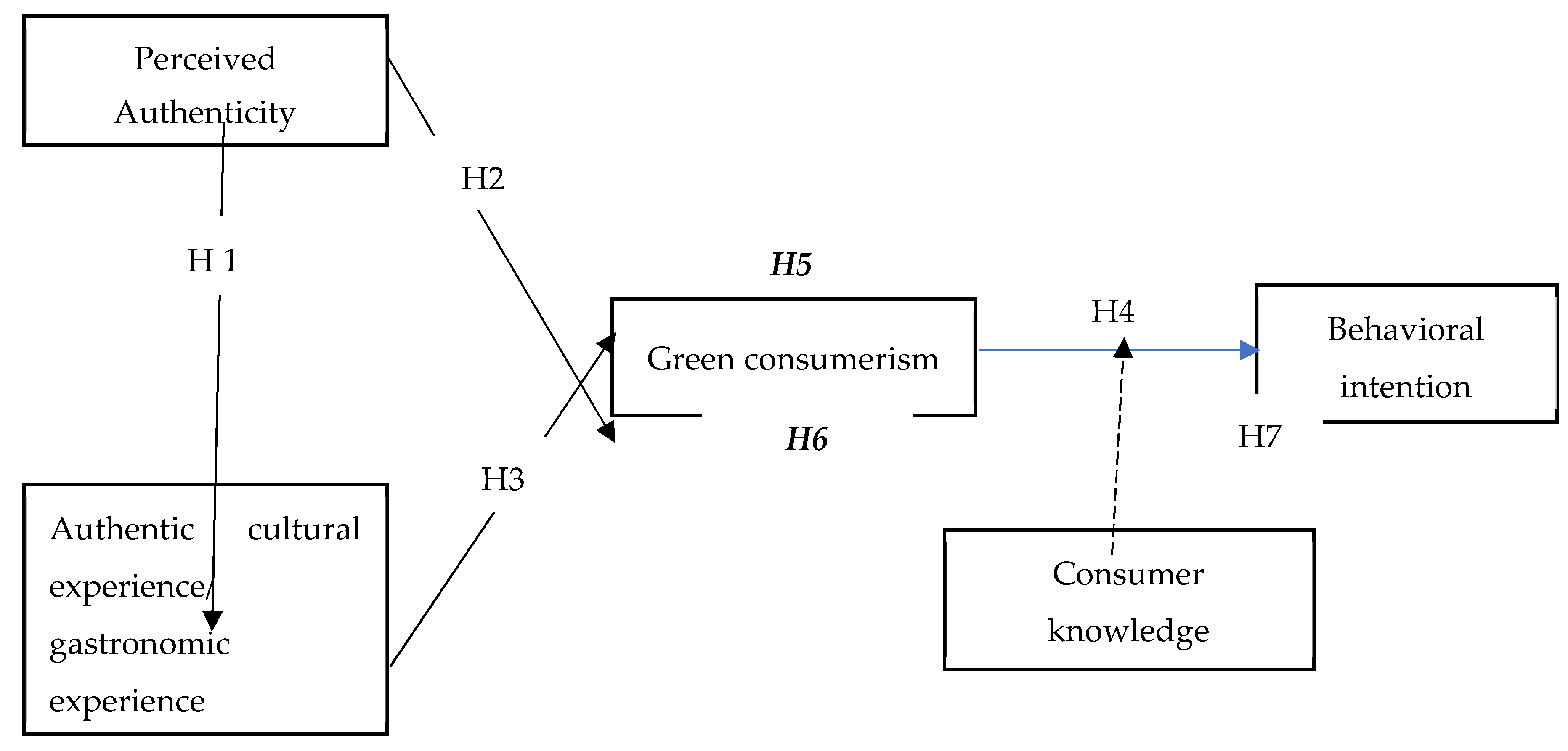

2.3. Development of Hypotheses

2.3.1. Authenticity

2.3.2. Effect of Perceived Authenticity on Consumers’ Authentic Gastronomic and Cultural Experiences

2.3.3. Green Consumerism

- <b>H4:

- Green consumerism positively influences behavioral intention to eat at authentic restaurants in Hail, Saudi Arabia.

2.3.4. Consumer Knowledge

3. Research Design

3.1. Methods

3.2. The Study Case: Authentic Restaurants in Hail

4. Study 1: Exploring Key Attributes of Authentic Restaurants

4.1. Research Process

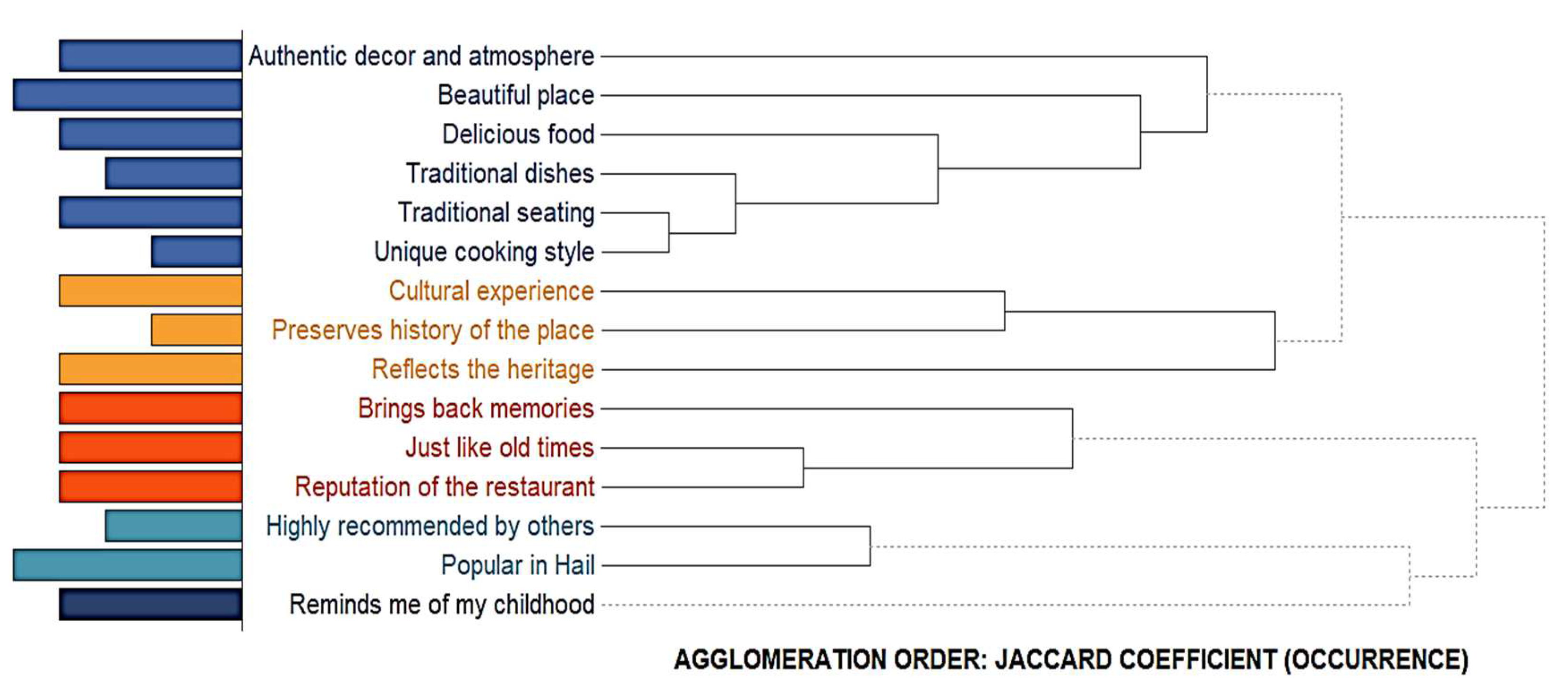

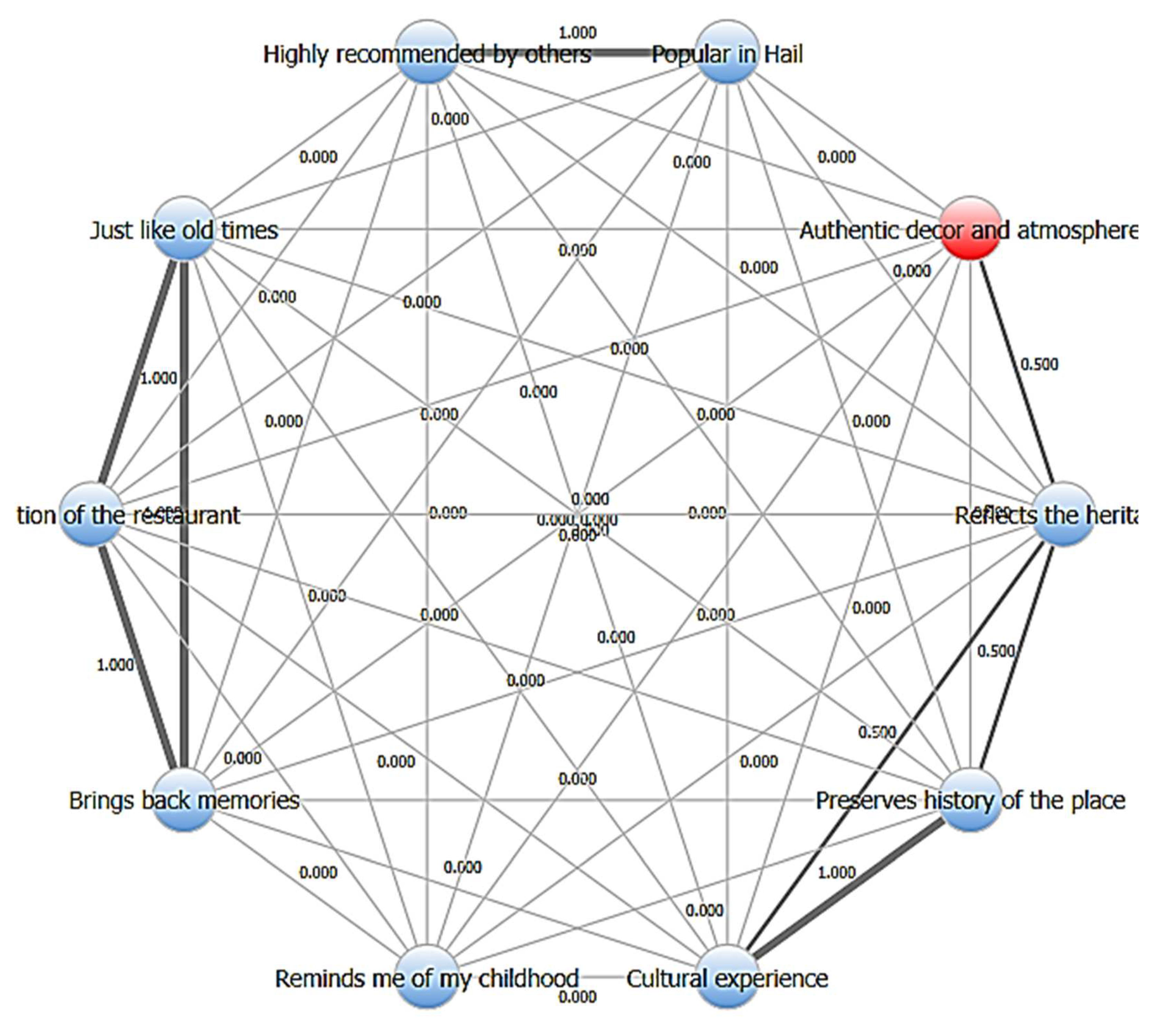

4.2. Coding Customer Reviews

4.3. Results and Discussion

5. Study 2: Influencing Factors of the Key Attributes and Their Impact on Customer Purchasing Intentions

5.1. Questionnaire Design

5.2. Data Collection

5.3. Data Analysis

5.3.1. Measurement Model Analysis

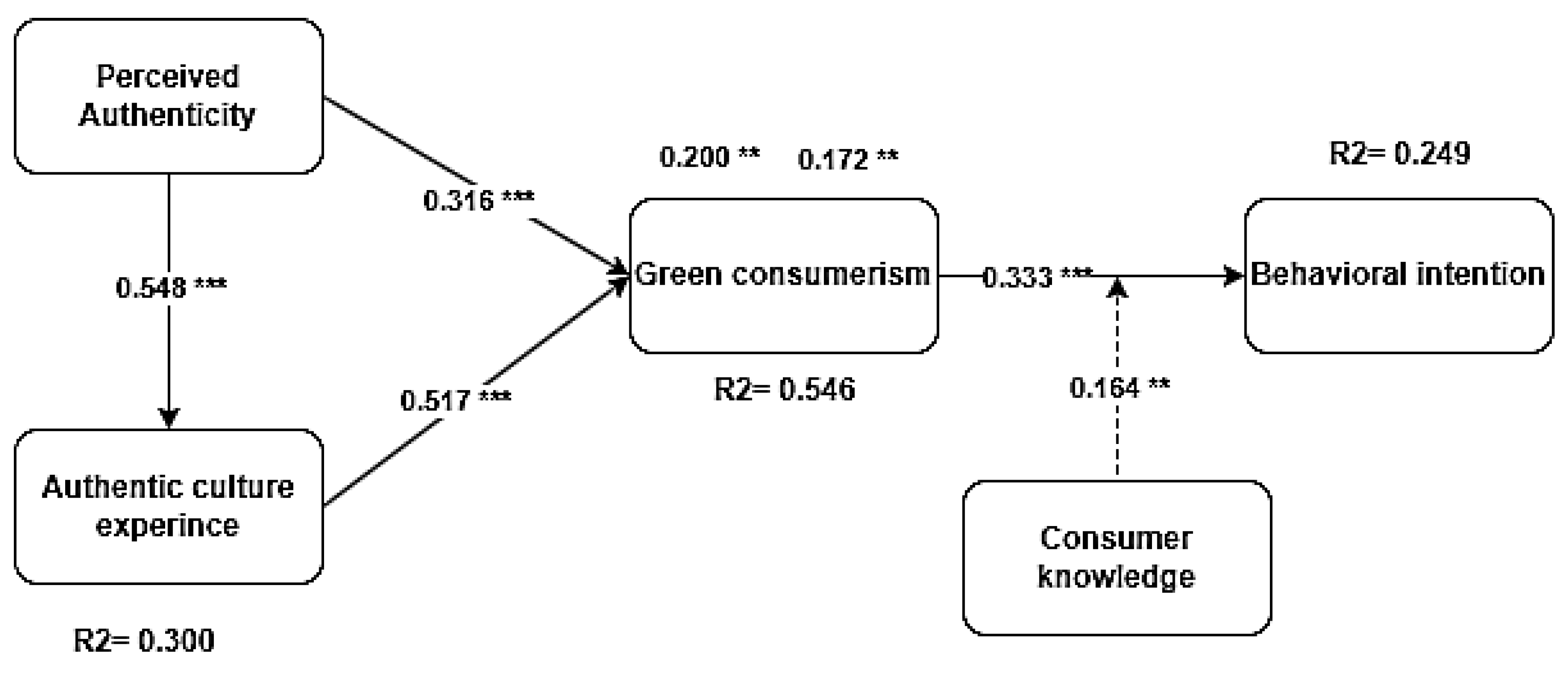

5.3.2. Structural Equation Model and Hypotheses Analysis

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitation and Future Research

References

- Xu, J.; Song, H.; Prayag, G. Using Authenticity Cues to Increase Repurchase Intention in Restaurants: Should the Focus Be on Ability or Morality? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lee, T.J.; Hyun, S.S. How Does a Global Coffeehouse Chain Operate Strategically in a Traditional Tea-Drinking Country? The Influence of Brand Authenticity and Self-Enhancement. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Carroll, G.R.; Kovács, B. Disambiguating Authenticity: Interpretations of Value and Appeal. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0179187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, R.; Hou, B. Perceived Authenticity of Traditional Branded Restaurants (China): Impacts on Perceived Quality, Perceived Value, and Behavioural Intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2950–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Song, H.; Youn, H. The Chain of Effects from Authenticity Cues to Purchase Intention: The Role of Emotions and Restaurant Image. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Song, H. The Influence of Perceived Credibility on Purchase Intention via Competence and Authenticity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, P.; Békési, D.; Gorton, M.; Popp, J.; Lengyel, P. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Traditional Food Products. Food Policy 2016, 61, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; DiPietro, R.B.; Levitt, J.A. The Role of Authenticity in Mainstream Ethnic Restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1035–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uggioni, P.L.; Proença, R.P. da C.; Zeni, L.A.Z.R. Assessment of Gastronomic Heritage Quality in Traditional Restaurants. Rev. De. Nutr. 2010, 23, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, I.; Paswan, A.K.; Guzman, F. Beyond the Shadow of a Doubt: The Effect of Consumer Knowledge on Restaurant Evaluation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Phan, B. Van; Kim, J.-H. The Congruity between Social Factors and Theme of Ethnic Restaurant: Its Impact on Customer’s Perceived Authenticity and Behavioural Intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Arcodia, C.; Novais, M.A.; Kralj, A. What We Know and Do Not Know about Authenticity in Dining Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Lee, K. AUTHENTICITY IN ETHNIC RESTAURANTS: INVESTIGATING THE ROLES OF ETHNOCENTRISM AND XENOCENTRISM. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 28, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hanks, L. Online Reviews: The Effect of Cosmopolitanism, Incidental Similarity, and Dispersion on Consumer Attitudes toward Ethnic Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 68, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Kim, J.-H. Effects of History, Location and Size of Ethnic Enclaves and Ethnic Restaurants on Authentic Cultural Gastronomic Experiences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3332–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S. (Shawn); Ha, J.; Park, K. Effects of Ethnic Authenticity: Investigating Korean Restaurant Customers in the U.S. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Lu, C.Y. Authenticity Perceptions, Brand Equity and Brand Choice Intention: The Case of Ethnic Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Hong, J.-H. The Effects of Contexts on Consumer Emotions and Acceptance of a Domestic Food and an Unfamiliar Ethnic Food: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between Chinese and Korean Consumers. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A. Theories of Emotion Causation: A Review. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 625–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, I.J.; Spindel, M.S.; Jose, P.E. Appraisals of Emotion-Eliciting Events: Testing a Theory of Discrete Emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation: Oxford University Press on Demand.[Google Scholar]. 1991.

- Hosany, S. Appraisal Determinants of Tourist Emotional Responses. J. Travel. Res. 2012, 51, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Li, J. (Justin) The Influence of Contemporary Negative Political Relations on Ethnic Dining Choices. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 644–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.; Kim, S. Role of Emotions in Fine Dining Restaurant Online Reviews: The Applications of Semantic Network Analysis and a Machine Learning Algorithm. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 23, 875–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Ouyang, Z. (Chris); Lu, L.; Zou, R. Drinking “Green”: What Drives Organic Wine Consumption in an Emerging Wine Market. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Roldán, J.L. The Role of Authenticity, Experience Quality, Emotions, and Satisfaction in a Cultural Heritage Destination. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, K.; Schoenmueller, V.; Bruhn, M. Authenticity in Branding—Exploring Antecedents and Consequences of Brand Authenticity. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K.P. Influences of Environmental and Hedonic Motivations on Intention to Purchase Green Products: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emekci, S. Green Consumption Behaviours of Consumers within the Scope of TPB. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, M. Does Haze Pollution Promote the Consumption of Energy-Saving Appliances in China? An Empirical Study Based on Norm Activation Model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Sadiq, M.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Green Apparel Buying Behaviour: A Stimulus–Organism–Behaviour–Consequence (SOBC) Perspective on Sustainability-oriented Consumption in Japan. Bus. Strategy Env. 2021, 30, 3589–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Saengon, P.; Alganad, A.M.N.; Chongcharoen, D.; Farrukh, M. Consumer Green Behaviour: An Approach towards Environmental Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Chandani, K.; Gilal, R.G.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, W.G.; Channa, N.A. Towards a New Model for Green Consumer Behaviour: A Self-determination Theory Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Theory of Green Purchase Behavior (TGPB): A New Theory for Sustainable Consumption of Green Hotel and Green Restaurant Products. Bus. Strategy Env. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Kunjuraman, V. Tourists’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels: Building on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. J. Tour. Futures 2024, 10, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A.; Otterbring, T. The Dark Side of Going Green: Dark Triad Traits Predict Organic Consumption through Virtue Signaling, Status Signaling, and Praise from Others. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, C.; Nazli, M.; Aydin, E.; Haque, A.U. The Effect of Environmental Concern on Conscious Green Consumption of Post-Millennials: The Moderating Role of Greenwashing Perceptions. Young Consum. 2021, 22, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology. Mass. Inst. Technol. 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-Organism-Response Reconsidered: An Evolutionary Step in Modeling (Consumer) Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.S.; Hampson, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Consumer Confidence and Green Purchase Intention: An Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, E.Q.; Ip, R.; Wang, K. How Does Rural Tourism Experience Affect Green Consumption in Terms of Memorable Rural-Based Tourism Experiences, Connectedness to Nature and Environmental Awareness? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Sithipolvanichgul, J.; Asmi, F.; Anwar, M.A.; Dhir, A. Drivers of Green Apparel Consumption: Digging a Little Deeper into Green Apparel Buying Intentions. Bus. Strategy Env. 2023, 32, 3997–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, F. The Influence Mechanism of Green Advertising on Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Energy-Saving Products: Based on the S-O-R Model. JUSTC 2023, 53, 0802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badu-Baiden, F.; Kim, S. (Sam); Xiao, H.; Kim, J. Understanding Tourists’ Memorable Local Food Experiences and Their Consequences: The Moderating Role of Food Destination, Neophobia and Previous Tasting Experience. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1515–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gálvez, J.C.; Torres-Matovelle, P.; Molina-Molina, G.; González Santa Cruz, F. Gastronomic Clusters in an Ecuadorian Tourist Destination: The Case of the Province of Manabí. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3917–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Mattila, A.S. The Impact of Servicescape Cues on Consumer Prepurchase Authenticity Assessment and Patronage Intentions to Ethnic Restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 346–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Phan, B. Van; Kim, J.-H. The Congruity between Social Factors and Theme of Ethnic Restaurant: Its Impact on Customer’s Perceived Authenticity and Behavioural Intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What Is Food Tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M. Coordination in Inter-Network Co-Opetitition: Evidence from the Tourism Sector. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 53, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Song, H.; Youn, H. The Chain of Effects from Authenticity Cues to Purchase Intention: The Role of Emotions and Restaurant Image. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.; Chatzopoulou, E.; Gorton, M. Perceptions of Localness and Authenticity Regarding Restaurant Choice in Tourism Settings. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappannelli, G.; Cappannelli, S.C. Authenticity: Simple Strategies for Greater Meaning and Purpose at Work and at Home; Emmis Books, 2004; ISBN 1578601487.

- Fine, G.A. Crafting Authenticity: The Validation of Identity in Self-Taught Art. Theory Soc. 2003, 32, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Schoenmüller, V.; Schäfer, D.; Heinrich, D. Brand Authenticity: Towards a Deeper Understanding of Its Conceptualization and Measurement. Adv. Consum. Res. 2012, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, N. Brand Authentication: Creating and Maintaining Brand Auras. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Lu, C.Y. Authenticity Perceptions, Brand Equity and Brand Choice Intention: The Case of Ethnic Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal *, T.; Hill, S. Developing a Framework for Indicators of Authenticity: The Place and Space of Cultural and Heritage Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 9, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, K.; Martinec, R. Consumer Perceptions of Iconicity and Indexicality and Their Influence on Assessments of Authentic Market Offerings. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Mattila, A.S. The Impact of Servicescape Cues on Consumer Prepurchase Authenticity Assessment and Patronage Intentions to Ethnic Restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 346–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Clifford, C. Authenticity and Festival Foodservice Experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansouri, M.; Verkerk, R.; Fogliano, V.; Luning, P.A. The Heritage Food Concept and Its Authenticity Risk Factors—Validation by Culinary Professionals. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 28, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Lamb, D. Extraordinary or Ordinary? Food Tourism Motivations of Japanese Domestic Noodle Tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S. (Shawn); Ha, J. The Influence of Cultural Experience: Emotions in Relation to Authenticity at Ethnic Restaurants. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2015, 18, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Björk, P.; Piramanayagam, S. Domestic Tourists and Local Food Consumption: Motivations, Positive Emotions and Savouring Processes. Ann. Leis. Res. 2023, 26, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A Consumer-Based Model of Authenticity: An Oxymoron or the Foundation of Cultural Heritage Marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Belyaeva, V. The Effect of Authenticity Orientation on Existential Authenticity and Postvisitation Intended Behavior. J. Travel. Res. 2021, 60, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Arcodia, C.; Abreu Novais, M.; Kralj, A.; Phan, T.C. Exploring the Multi-Dimensionality of Authenticity in Dining Experiences Using Online Reviews. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, J.; Frommeyer, B.; Koch, J.; Gerdt, S.; Schewe, G. Voluntary Carbon Offsetting and Consumer Choices for Environmentally Critical Products—An Experimental Study. Bus. Strategy Env. 2021, 30, 3009–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizomyliotis, I.; Poulis, A.; Konstantoulaki, K.; Giovanis, A. Sustaining Brand Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Green Consumption Values. Bus. Strategy Env. 2021, 30, 3025–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, R.; Shapoval, V.; Murphy, K.S. Measuring Generation Y Consumers’ Perceptions of Green Practices at Starbucks: An IPA Analysis. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal-directed Behaviours: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer Behavior and Environmental Sustainability in Tourism and Hospitality: A Review of Theories, Concepts, and Latest Research. Sustain. Consum. Behav. Environ. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Wen, J. Effects of COVID-19 on Hotel Marketing and Management: A Perspective Article. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Moon, H.; Hyun, S.S. Uncovering the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Consumption for Green Hotels and Green Restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 1581–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Guix, M.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G.; Molenkamp, N. Millennials’ Willingness to Pay for Green Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Moon, H.; Hyun, S.S. Uncovering the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Consumption for Green Hotels and Green Restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 1581–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-R.; Chiu, T.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Huang, W.-S. Generation Y’s Revisit Intention and Price Premium for Lifestyle Hotels: Brand Love as the Mediator. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2020, 21, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. Motivations behind Consumers’ Organic Menu Choices: The Role of Environmental Concern, Social Value, and Health Consciousness. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. (Shawn) Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Green Practices at Restaurants? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Umashankar, V.; Choi, G.; Parsa, H.G. A Comparative Study of Consumers’ Green Practice Orientation in India and the United States: A Study from the Restaurant Industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2008, 11, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergelsberg, E.L.P.; MacLeod, C.; Mullan, B.; Rudaizky, D.; Allom, V.; Houben, K.; Lipp, O.V. Food Healthiness versus Tastiness: Contrasting Their Impact on More and Less Successful Healthy Shoppers within a Virtual Food Shopping Task. Appetite 2019, 133, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanova, B.; Vauclair, C.-M.; Kervyn, N.; Schumann, S.; Wood, R.; Klein, O. Savouring Morality. Moral Satisfaction Renders Food of Ethical Origin Subjectively Tastier. Appetite 2015, 91, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, J.; Kim, M.-J.; Ryu, K. Does Perceived Restaurant Food Healthiness Matter? Its Influence on Value, Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in Restaurant Operations in South Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Moon, H.; Hyun, S.S. Uncovering the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Consumption for Green Hotels and Green Restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 1581–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. The Effects of Hotel Green Business Practices on Consumers’ Loyalty Intentions: An Expanded Multidimensional Service Model in the Upscale Segment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3787–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Berbekova, A.; Uysal, M.; Wang, J. Emotional Solidarity and Co-Creation of Experience as Determinants of Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory Perspective. J. Travel. Res. 2024, 63, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the World through GREEN-tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Mattila, A.S. The Impact of Servicescape Cues on Consumer Prepurchase Authenticity Assessment and Patronage Intentions to Ethnic Restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 346–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Bala, H. Bridging the Qualitative-Quantitative Divide: Guidelines for Conducting Mixed Methods Research in Information Systems. MIS Q. 2013, 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Almansouri, M.; Verkerk, R.; Fogliano, V.; Luning, P.A. The Heritage Food Concept and Its Authenticity Risk Factors—Validation by Culinary Professionals. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 28, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage publications, 2018; ISBN 1506395678.

- Fathy, E.A.; Salem, I.E.; Zidan, H.A.K.Y.; Abdien, M.K. From Plate to Post: How Foodstagramming Enriches Tourist Satisfaction and Creates Memorable Experiences in Culinary Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Kooli, C.; Alqasa, K.M.A.; Afaneh, J.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fayyad, S. Resilience for Sustainability: The Synergistic Role of Green Human Resources Management, Circular Economy, and Green Organizational Culture in the Hotel Industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoulides, G.A. Modern Methods for Business Research; Quantitative Methodology Series; Taylor & Francis, 1998; ISBN 9781135684129.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge, 2013; ISBN 9781134742707.

| Category | Codes |

| Environment Authenticity (EA) | “Beautiful place” “Traditional seating” “Authentic decor and atmosphere” |

| Food Authenticity (FA) | “Delicious food” “Traditional dishes” “Unique cooking style” |

| Historical and Cultural Value (HC) | “Reflects the heritage” “Cultural experience” “Preserves history of the place” |

| Nostalgia (NOS) | “Reminds me of my childhood” “Just like old times” “Brings back memories” |

| Brand Value (BV) | “Reputation of the restaurant” “Highly recommended by others” “Popular in Hail” |

| Variables | Items | Loadings | AVE | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite reliability | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Authenticity | EA1 | 0.645 | 0.535 | 0.960 | 0.963 | 2.245 |

| EA2 | 0.642 | 4.204 | ||||

| EA3 | 0.652 | 4.215 | ||||

| EA4 | 0.701 | 4.402 | ||||

| EA5 | 0.731 | 4.370 | ||||

| FA1 | 0.749 | 3.081 | ||||

| FA2 | 0.782 | 4.038 | ||||

| FA3 | 0.734 | 3.649 | ||||

| FA4 | 0.766 | 3.370 | ||||

| FA5 | 0.783 | 3.012 | ||||

| HC1 | 0.720 | 2.360 | ||||

| HC2 | 0.787 | 2.836 | ||||

| HC3 | 0.763 | 2.747 | ||||

| HC4 | 0.773 | 2.944 | ||||

| NOS1 | 0.776 | 3.714 | ||||

| NOS2 | 0.705 | 2.486 | ||||

| NOS3 | 0.750 | 3.220 | ||||

| NOS4 | 0.704 | 2.889 | ||||

| BV1 | 0.768 | 3.036 | ||||

| BV2 | 0.707 | 2.500 | ||||

| BV3 | 0.733 | 2.986 | ||||

| BV4 | 0.715 | 2.918 | ||||

| BV5 | 0.711 | 2.896 | ||||

| Green consumerism | GCON1 | 0.814 | 0.679 | 0.882 | 0.913 | 2.236 |

| GCON2 | 0.835 | 2.326 | ||||

| GCON3 | 0.830 | 2.378 | ||||

| GCON4 | 0.864 | 2.719 | ||||

| GCON5 | 0.774 | 1.872 | ||||

| Authentic cultural experience/ gastronomic experience | GASE1 | 0.840 | 0.737 | 0.881 | 0.918 | 2.102 |

| GASE2 | 0.850 | 2.266 | ||||

| GASE3 | 0.890 | 2.804 | ||||

| GASE4 | 0.853 | 2.330 | ||||

| Consumer knowledge | KNOW1 | 0.760 | 0.585 | 0.771 | 0.849 | 1.385 |

| KNOW2 | 0.846 | 1.626 | ||||

| KNOW3 | 0.741 | 1.611 | ||||

| KNOW4 | 0.704 | 1.622 | ||||

| Behavioral intention | INT1 | 0.895 | 0.818 | 0.889 | 0.818 | 2.574 |

| INT1 | 0.914 | 2.598 | ||||

| INT1 | 0.904 | 2.594 |

| Authentic cultural experience/ gastronomic experience | Behavioral intention | Consumer knowledge | Green consumerism | Perceived Authenticity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic cultural experience/ gastronomic experience | 0.858 | ||||

| Behavioral intention | 0.523 | 0.905 | |||

| Consumer knowledge | 0.179 | 0.274 | 0.765 | ||

| Green consumerism | 0.690 | 0.423 | 0.146 | 0.824 | |

| Perceived Authenticity | 0.548 | 0.355 | 0.133 | 0.600 | 0.732 |

| Structural Path | Beta | T Statistics | P Values | F2 | Results | 2.5 % | 97.5 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | |||||||

| Perceived Authenticity→ Authentic cultural experience/ gastronomic experience | 0.548 | 8.034 | 0.000 | 0.429 | H1, Support | 0.409 | 0.671 |

| Perceived Authenticity → Green consumerism | 0.316 | 4.166 | 0.000 | 0.154 | H2, Support | 0.177 | 0.477 |

| Authentic cultural experience/ gastronomic experience → Green consumerism | 0.517 | 6.788 | 0.000 | 0.411 | H3, Support | 0.355 | 0.657 |

| Green consumerism → Behavioral intention | 0.333 | 4.632 | 0.000 | 0.127 | H4, Support | 0.190 | 0.458 |

| Indirect Effect | |||||||

| Perceived Authenticity → Green consumerism → Behavioral intention | 0.200 | 3.161 | 0.002 | H5, Support | 0.048 | 0.184 | |

| Authentic cultural experience/ gastronomic experience→ Green consumerism → Behavioral intention | 0.172 | 2.974 | 0.003 | H6, Support | 0.073 | 0.303 | |

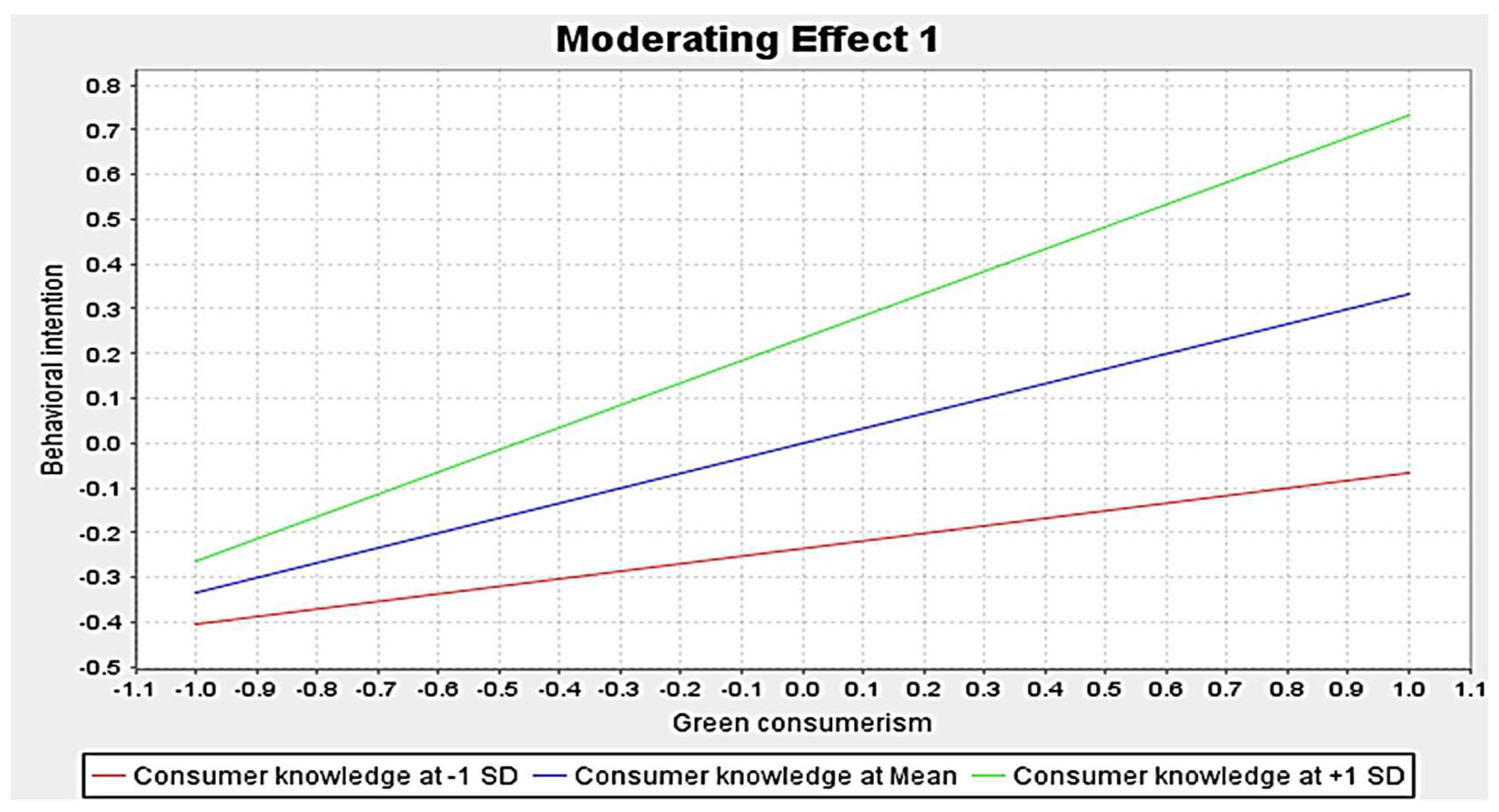

| Moderating Paths | |||||||

|

Green consumerism × Consumer knowledge → Behavioral intention |

0.146 | 2.31 | 0.019 | H7, Support | 0.040 | 0.304 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).