Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Although marketing mix elements have been expanded to 7Ps in the literature, particularly within the contexts of service marketing and experiential marketing, the initial 4Ps represent the first and most tangible steps firms take in transitioning to green marketing, as well as their core strategic orientations. These four elements typically form the backbone of a green marketing strategy.

- Due to the focused nature of scale development, a 'practice culture' scale encompassing all 7Ps could have increased conceptual complexity and scale administration (dimensions/items) challenges, potentially weakening its practicality and statistical power. Therefore, focusing initially on the fundamental 4Ps was preferred to maintain methodological robustness.

- A lack of a valid and reliable scale measuring the practice culture of the basic 4Ps of green marketing was identified in the literature, and this study primarily aims to fill this gap. The measurement of the extended 7Ps (people, physical evidence, process) involves different dynamics and likely requires a separate study, hence it was excluded from the current scope.

- The current 4P-focused scale provides a foundational measurement instrument for the green marketing literature. This study can serve as a basis and starting point for future research that will examine the extended mix elements (people, physical evidence, process) or expand the scale.

- The primary aim of this study is to develop a scale through which SMEs can measure and evaluate their Green Marketing Mix (4P) practices. This study presents an instrument for the identification and evaluation of the Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture (GMMPC) among SMEs operating in different industry sectors. Thus, it aims to contribute to filling such a gap identified in the literature. The developed scale may provide the following benefits:

- It can offer detailed information about the current status of SMEs regarding their GMMPC and assist in making assessments; it can also provide data for determining businesses' green marketing strategies.

- It can enable comparative analyses among firms of different sizes operating in various industry sectors across different regions.

- It can play a supportive role in evaluating the effectiveness of green marketing practices and providing a scientific basis for research.

2. Green Marketing Mix

3. Method

4. Scale Development Study on Green Marketing Mix Practice Culture (GMMPC)

4.1. Study 1: Pre-Test Analysis

|

Panel Size |

Proportion Agreeing Essential |

CVR Critical Exact Values |

One-Sided pValue | Ncritical (Min. No. of Experts Required to Agree Item Essential) | Ncriticaly Calculated From CRITBINOM Function |

| 5 | 1 | 1.00 | .031 | 5 | 4 |

| 6 | 1 | 1.00 | .016 | 6 | 5 |

| 7 | 1 | 1.00 | .008 | 7 | 6 |

| 8 | .875 | .750 | .035 | 7 | 6 |

| 9 | .889 | .778 | .020 | 8 | 7 |

| 10 | .900 | .800 | .011 | 9 | 8 |

| 15 | .800 | .600 | .018 | 12 | 11 |

| 20 | .750 | .500 | .021 | 15 | 14 |

| 25 | .720 | .440 | .022 | 18 | 17 |

| 30 | .667 | .333 | .049 | 20 | 19 |

4.2. Study 2

5. Discussion and Conclusion

6. Theoretical Contribution

7. Managerial/Practical Implications

8. Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Statements | Expert opinions | ||

| Number of experts who said "Not Necessary” | Number of experts who said "should be corrected | Number of experts who said “Necessary” | ||

| 1 | We design products to save energy with reduced materials | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | Choosing packaging materials from biodegradable products is effective in increasing the sales of the enterprise. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 3 | With the green packaging approach, our materials are less damaged (such as breakage, deterioration) | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 4 | Green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 6 | Green packaging practices reduce costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 7 | We use recycled materials in our products. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 8 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 9 | We consider the environment when designing the product. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 10 | We use ecological green materials in production. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 11 | Our suppliers' products are recyclable | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 12 | We advertise our green products. | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| 13 | We use renewable energy sources in production | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 14 | Our company offers innovative green products to the market. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 15 | Green products provide our company with the opportunity to differentiate. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 16 | The raw materials we use are safe for the environment. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 17 | We try to use less material in packaging | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 18 | Our company produces environmentally friendly products | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 19 | Environment is the main criterion for supplier selection. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 20 | We support the green environmental components of the product. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 21 | A separate unit that monitors environmental costs has been established in our organization. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 22 | The use of recycled materials in the enterprise reduces costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 23 | Customers are willing to pay higher prices for green products. | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 24 | Our customers are willing to pay high prices for green products. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 25 | We take environmental factors into account in price policy. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 26 | We use local products to reduce transport costs. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 27 | Green packaging practices make our products lighter | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 28 | We cover the additional cost of an environmentally friendly product. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 29 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 30 | We encourage the use of e-commerce as it is more environmentally friendly. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 31 | The environmental damage of our distribution channel is minimized. | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 32 | We use electronic information systems in green transport. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 33 | Thanks to green transport, we use less fuel. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 34 | Thanks to green transport, we can reduce costs by saving time on the delivery route | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 35 | We monitor emissions from the distribution of the product. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 36 | The environmental aspect of our products is at the forefront in marketing. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 37 | Our environmentally friendly practices are updated on our website. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 38 | Our company chooses packaging materials from degradable products. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 39 | The profit margin has increased because of material reduction in the provision of services. | 6 | 0 | 4 |

| 40 | Our business uses the environmentally friendly green label. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 41 | The labels contain information on recycling. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 42 | We prevent the use of dangerous substances in packaging. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 43 | The amount of goods is minimized to increase delivery flexibility. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 44 | The warehouse of our company is organized environmentally friendly methods. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 45 | The use of environmentally friendly green labels is effective in increasing business sales. | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 46 | We choose cleaner transport systems | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 47 | We use green arguments in marketing communication. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 48 | Our marketing communication reflects the company's commitment to the environment. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 49 | Environmental claims in advertising are often met with criticism from the environment (competitors, consumer organizations, etc.). | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 50 | We support the green environmental components of the product. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 51 | Environmental labelling is an effective promotional tool for our company. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 52 | We inform consumers about environmental management in the company | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities on environmental issues. | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 54 | We use specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 55 | We prevent the use of hazardous substances in the packaging of the product | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 56 | We implement a paperless policy in our procurement as much as possible. | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 57 | We emphasize the image of "environmentally friendly business" in promotional activities | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 58 | Our company uses statements reflecting the reality of the product advertisements. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 59 | Our image as an environmentally friendly company gives us a competitive advantage. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 60 | We emphasize in our advertisements that our products are green. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 61 | The product packaging is colored green, which is identical to the environment. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 62 | Our product promotions include environmental protection activities. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 63 | We aim to minimize negative impacts on the environment throughout the product life cycle. | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 64 | The use of Information Technologies in the enterprise reduces distribution costs | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 65 | We make sure that recycled materials are used in production. | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 66 | The production process in our enterprise is based on ISO 14001 certification. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 67 | Customers want the company to produce green products. | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| 68 | When promoting products, we prefer digital communication as it is more environmentally friendly | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 69 | It is normal for green products to be priced slightly higher than other products. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 70 | We use environmentally friendly technologies in the production process | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 71 | We use recycled materials for packaging. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 72 | Our company tries to convince its customers to be environmentally conscious during direct sales. | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 73 | Our company tries to convince its customers to be environmentally sensitive during direct sales. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 74 | We utilize green vehicles in the distribution channel. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 75 | We can reduce our costs with green transport | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 76 | We design for remanufacturing so that waste can be recycled. | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 77 | The enterprise uses minimal packaging materials. | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| 78 | We use integrated transport systems in distribution | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 79 | Our business is trying to reduce the use of packaging. | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 80 | Producing green products increases costs | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 81 | The company co-operates with environmental groups to effectively promote a "green image" | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 82 | We minimize our waste in production | 0 | 1 | 9 |

References

- Papadas, K.-K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green Marketing Orientation: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Business Research 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.H.; Mehraj, D. Identifying the Factors of Internal Green Marketing: A Scale Development and Psychometric Evaluation Approach. International Journal of Manpower 2021, 43, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, A.; and Strutton, D. Marketing Mix Strategies for Closing the Gap between Green Consumers’ pro-Environmental Beliefs and Behaviors. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2014, 22, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; and Woolley, M. Green Marketing Messages and Consumers’ Purchase Intentions: Promoting Personal versus Environmental Benefits. Journal of Marketing Communications 2014, 20, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, B.J.; Soule, C.A.A. Green Demarketing in Advertisements: Comparing “Buy Green” and “Buy Less” Appeals in Product and Institutional Advertising Contexts. Journal of Advertising 2016, 45, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvi, M.S.; Önem, Ş. Impact of Variables in the UTAUT 2 Model on the Intention to Use a Fully Electric Car. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Skackauskiene, I.; Díaz-Meneses, G. Measuring Green Marketing: Scale Development and Validation. Energies 2022, 15, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, O.; Filiz, M. Yeşil Pazarlama Ölçeğinin Türkçe Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. ESAD 2023, 19, 425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcikova, D.; Krizanova, A.; Kliestikova, J.; Rypakova, M. Green Marketing as the Source of the Competitive Advantage of the Business. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.S.; Tiamiyu, M.F. Application of GREEN Scale to Understanding US Consumer Response to Green Marketing Communications. Psychology & Marketing 2018, 35, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the World through GREEN-Tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Yang, C.-H. Applying a Multiple Criteria Decision-Making Approach to Establishing Green Marketing Audit Criteria. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 210, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyadat, A.A.; Almuhana, M.; Al-Bataineh, T. The Role of Green Marketing Strategies for a Competitive Edge: A Case Study about Analysis of Leading Green Companies in Jordan. Business Strategy & Development 2024, 7, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. Green Marketing in B2B Organisations: An Empirical Analysis from the Natural-resource-based View of the Firm. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 2013, 28, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Dangwal, R.; Raina, S. Conceptualisation, Development and Validation of Green Marketing Orientation (GMO) of SMEs in India: A Case of Electric Sector. Journal of Global Responsibility 2014, 5, 312–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A. Facing the Backlash: Green Marketing and Strategic Reorientation in the 1990s. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2000, 8, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An Analysis of Definitions, Strategy Steps, and Tools through a Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Rosenberger, P.J. Reevaluating Green Marketing: A Strategic Approach. Business Horizons 2001, 44, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Towards Sustainability: The Third Age of Green Marketing. The Marketing Review 2001, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Kaur, G. Green Marketing: An Attitudinal and Behavioural Analysis of Indian Consumers. Global Business Review 2004, 5, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, A.; Bañegil, T.M. Green Marketing Philosophy: A Study of Spanish Firms with Ecolabels. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2006, 13, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, K.; Batubara, H.M.; Rosalina, R.; Evanita, S.; Friyatmi, F. Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Environmental Knowledge. Jurnal Apresiasi Ekonomi 2024, 12, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, T.O. Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2018, 5, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Prabhakar, G.; Luo, X.; Tseng, H.-T. Exploring Generation Z Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Green Products during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. e-Prime - Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2024, 8, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jave-Chire, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Guevara-Zavaleta, V. Footwear Industry’s Journey through Green Marketing Mix, Brand Value and Sustainability. Sustainable Futures 2025, 9, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdrolia, E.; Zarotiadis, G. A Comprehensive Review for Green Product Term: From Definition to Evaluation. Journal of Economic Surveys 2019, 33, 150–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-H.; Lin, G.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, P.-Z.; Su, Z.-C. Exploring the Effect of Starbucks’ Green Marketing on Consumers’ Purchase Decisions from Consumers’ Perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 56, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.R.; Costa, M.F. da; Maciel, R.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Wanderley, L.O. Consumer Antecedents towards Green Product Purchase Intentions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 313, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Reinventing Marketing to Manage the Environmental Imperative. Journal of Marketing 2011, 75, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, P.; Sivakoti Reddy, M. Analyzing the Effect of Product, Promotion and Decision Factors in Determining Green Purchase Intention: An Empirical Analysis. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation 2020, 24, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, M.; Baloran,Anna; Bagano,April; Tan,Ana; Athanasius,Sentot; and Retnawati, B. Green Marketing Practices and Issues: A Comparative Study of Selected Firms in Indonesia and Philippines. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 2021, 22, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, A.; Bandara, V.; Silva, A.; De Mel, D. Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Customers’ Green Purchasing Intention with Special Reference to Sri Lankan Supermarkets; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, Myth, Farce or Prophesy? Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthey, B.K. Impact of Green Marketing Practices on Consumer Purchase Intention and Buying Decision with Demographic Characteristics as Moderator. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2019, 6, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Garg, A.; Ram, S.; Gajpal, Y.; Zheng, C. Research Trends in Green Product for Environment: A Bibliometric Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukonza, C.; Swarts, I. The Influence of Green Marketing Strategies on Business Performance and Corporate Image in the Retail Sector. Business Strategy and the Environment 2020, 29, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Oh, J.; Park, J.-H.; Joo, C. Perceived Value and Adoption Intention for Electric Vehicles in Korea: Moderating Effects of Environmental Traits and Government Supports. Energy 2018, 159, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningtiyas, N.; Novianto, A.S. The Impact of Green Price, Green Promotion, and Green Place on the Economy of Communities in Tourism Areas through Environmental Sustainability Entering the New Normal. Quantitative Economics and Management Studies 2023, 4, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer Banzhaf, H. Green Price Indices. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2005, 49, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. Addressing Climate Change through Price and Non-Price Interventions. European Economic Review 2019, 119, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the Marketing Mix: Do Firms Do It and Does It Pay Off? J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Rethinking Marketing: Shifting to a Greener Paradigm. In Greener Marketing; Routledge, 1999 ISBN 978-1-351-28308-3.

- Trujillo, A.; Arroyo, P.; Carrete, L. Do Environmental Practices of Enterprises Constitute an Authentic Green Marketing Strategy? A Case Study from Mexico. International Journal of Business and Management 2014, 9, p175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önem, Ş.; Selvi, M.S. Scale Development on the Effect of Social Media Influencers on Purchase Intention. MAKU IIBFD 2024, 11, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B. The Impact of Green Marketing Mix Elements on Green Customer Based Brand Equity in an Emerging Market. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 2022, 15, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novela, S.; Novita; Hansopaheluwakan, S. Analysis of Green Marketing Mix Effect on Customer Satisfaction Using 7p Approach. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities 2018, 26, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Soelton, M.; Rohman, F.; Asih, D.; Saratian, E.T.P.; Wiguna, S.B. Green Marketing That Effect the Buying Intention Healthcare Products. European Journal of Business and Management 2020, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, S.O. Unveiling Willingness to Pay for Green Stadiums: Insights from a Choice Experiment. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 434, 139985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, Z. Willingness to Pay a Premium Price for Green Products: Does a Reference Group Matter? Environ Dev Sustain 2023, 25, 8699–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Wang, Y.; Hou, C.; Liu, B. Will the Public Pay for Green Products? Based on Analysis of the Influencing Factors for Chinese’s Public Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Green Products. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 61408–61422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, C.J.; Schijns, J.; Lambrechts, W.; Vijgen, S. Green Marketing as an Environmental Practice: The Impact on Green Satisfaction and Green Loyalty in a Business-to-Business Context. Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 30, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, T.; Kubeš, V.; Baran, D. Willingness to Pay for Eco-Friendly Furniture Based on Demographic Factors. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 250, 119466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meet, R.K.; Kundu, N.; Ahluwalia, I.S. Does Socio Demographic, Green Washing, and Marketing Mix Factors Influence Gen Z Purchase Intention towards Environmentally Friendly Packaged Drinks? Evidence from Emerging Economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 434, 140357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Seidu, A.S.; Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y.; Ahmed, A.S. Green Marketing Mix and Repurchase Intention: The Role of Green Knowledge. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 2024, 15, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yi, S. Pricing Policies of Green Supply Chain Considering Targeted Advertising and Product Green Degree in the Big Data Environment. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 164, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Yavari, M. Pricing Policies for a Dual-Channel Green Supply Chain under Demand Disruptions. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2019, 127, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Uchida, T.; Conrad, J.M. Price Premiums for Eco-Friendly Commodities: Are ‘Green’ Markets the Best Way to Protect Endangered Ecosystems? Environ Resource Econ 2005, 32, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford,Edwin R. ; and Hartman, C.L. Avoiding Green Marketing Myopia: Ways to Improve Consumer Appeal for Environmentally Preferable Products. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Yang, J. Is Green Place-Based Policy Effective in Mitigating Pollution? Firm-Level Evidence from China. Economic Analysis and Policy 2024, 83, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikiene, D.; Qadir, H.; Streimikis, J. Effect of Green Marketing Mix, Green Customer Value, and Attitude on Green Purchase Intention: Evidence from the USA. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 11473–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, T.; Ibrahim, S.; Hasaballah, A.H.; Bleady, A. The Influence of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention: The Mediation Role of Environmental Knowledge. International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research 2017, 8, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Akdemir, M.A.; Kara, A.U.; Sagbas, M.; Sahin, Y.; Topcuoglu, E. The Mediating Role of Green Innovation and Environmental Performance in the Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pu, X.; Li, Y. Green Manufacturing Strategy Considering Retailers’ Fairness Concerns. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavo, J.U.; Trento, L.R.; de Souza, M.; Pereira, G.M.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Borchardt, M.; Zvirtes, L. Green Marketing in Supermarkets: Conventional and Digitized Marketing Alternatives to Reduce Waste. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 296, 126531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majali, M.; Tarabieh, S. Effect of Internal Green Marketing Mix Elements on Customers’ Satisfaction in Jordan: Mu’tah University Students. Jordan Journal of Business Administration 2020, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-López, L.E.; Álamo-Vera, F.R.; Ballesteros-Rodríguez, J.L.; De Saá-Pérez, P. Socialization of Business Students in Ethical Issues: The Role of Individuals’ Attitude and Institutional Factors. The International Journal of Management Education 2020, 18, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, E.C.; Banterle, A.; Stranieri, S. Trust to Go Green: An Exploration of Consumer Intentions for Eco-Friendly Convenience Food. Ecological Economics 2018, 148, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, U.; Bentley, Y.; Pang, G. The Role of Collaboration in the UK Green Supply Chains: An Exploratory Study of the Perspectives of Suppliers, Logistics and Retailers. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 70, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhou, Y.; Bian, J.; Lai, K.K. Optimal Channel Structure for a Green Supply Chain with Consumer Green-Awareness Demand. Ann Oper Res 2023, 324, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaysoy, O.; Topcuoglu, E.; Ozgen-Cigdemli, A.O.; Kaygin, E.; Kosa, G.; Turan-Torun, B.; Kobanoglu, M.S.; Uygungil-Erdogan, S. The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Intention to Leave the Job. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1490203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav, R.; Bhalerao, V.; Deshmukh, A. Green Marketing: Greening the 4 Ps of Marketing. International Journal of Knowledge and Research in Management and E-Commerce 2015, 5, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.K.; Yazdanifard, R. The Concept of Green Marketing and Green Product Development on Consumer Buying Approach. Global Journal of Commerce & Management Perspective 2014, 3, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Arseculeratne, D.; Yazdanifard, R. How Green Marketing Can Create a Sustainable Competitive Advantage for a Business. International Business Research 2013, 7, p130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbes, C.; Beuthner, C.; Ramme, I. How Green Is Your Packaging—A Comparative International Study of Cues Consumers Use to Recognize Environmentally Friendly Packaging. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2020, 44, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Lei, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. The Influence of Green Packaging on Consumers’ Green Purchase Intention in the Context of Online-to-Offline Commerce. Journal of Systems and Information Technology 2021, 23, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.S.; Bait Ali Sulaiman, M.A.; Hasan Al-Kumaim, N.; Mahmood, A.; Abbas, M. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Consumer Behavior towards the Environment—A Study from the UAE. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonysamy, K.; Paulraj, G. Examining the Effects of Green Attitude on the Purchase Intention of Sustainable Packaging. Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research-DISCONTINUED 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Choudhary, S.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Panda, T.K. Do Altruistic and Egoistic Values Influence Consumers’ Attitudes and Purchase Intentions towards Eco-Friendly Packaged Products? An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2019, 50, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Noh, J.; Oh, Y.; Park, K.-S. Structural Relationships of a Firm’s Green Strategies for Environmental Performance: The Roles of Green Supply Chain Management and Green Marketing Innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 356, 131877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ Purchase Behaviour and Green Marketing: A Synthesis, Review and Agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.; Ali, N.A. The Impact of Green Marketing Strategy on the Firm’s Performance in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 172, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, W.; Xu, E.; Xu, X. Pricing and Green Promotion Decisions in a Retailer-Owned Dual-Channel Supply Chain with Multiple Manufacturers. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 2023, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.S. Green Marketing Strategies: How Do They Influence Consumer-Based Brand Equity? JGBA 2017, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Rahman, Md.S. Measuring the Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Green Purchasing Behavior: A Study on Bangladeshi Consumers. The Comilla University Journal of Business Studies 2018, 5, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. State of Green Marketing Research over 25 Years (1990-2014): Literature Survey and Classification. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2016, 34, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-H.; Malek, K.; Roberts, K.R. The Effectiveness of Green Advertising in the Convention Industry: An Application of a Dual Coding Approach and the Norm Activation Model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2019, 39, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, K.C.; Nguyen-Viet,Bang; and Phuong Vo, H. N. Toward Sustainable Development and Consumption: The Role of the Green Promotion Mix in Driving Green Brand Equity and Green Purchase Intention. Journal of Promotion Management 2023, 29, 824–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.; Gani, A.; Taufan, R.; Syahnur, H.; Basalamah, J. Green Marketing Practice In Purchasing Decision Home Care Product. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research 2020, 9, 893–896. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Su, W.; Hahn, J. How Green Transformational Leadership Affects Employee Individual Green Performance—A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, S.B.; Martínez, M.P.; Correa, C.M.; Moura-Leite, R.C.; Silva, D.D. Greenwashing Effect, Attitudes, and Beliefs in Green Consumption. RAUSP Management Journal 2019, 54, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-T.; Niu, H.-J. Green Consumption: Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Consciousness, Social Norms, and Purchasing Behavior. Business Strategy and the Environment 2018, 27, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S. “I Buy Green Products for My Benefits or Yours”: Understanding Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Green Products. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2021, 34, 1721–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.-M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective; John Wiley & Sons, 2012; ISBN 978-1-119-96619-7.

- Nguyen–Viet, B.; and Nguyen Anh, T. Green Marketing Functions: The Drivers of Brand Equity Creation in Vietnam. Journal of Promotion Management 2022, 28, 1055–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Sha, Y.; Ji, H.; Fan, J. What Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Green Packaging? Evidence from China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 141, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Masani, S.; Dasgupta, T. Packaging-Influenced-Purchase Decision Segment the Bottom of the Pyramid Consumer Marketplace? Evidence from West Bengal, India. Asia Pacific Management Review 2022, 27, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, R.; Altunışık, R.; Bayraktaroğlu, S.; Yıldırım, E. Research Methods in Social Sciences: SPSS Applications; 8th Edition.; Sakarya Publishing: Sakarya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, A.C.; Bush, R.F. Marketing Research; Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2005; ISBN 978-0-13-228035-8.

- OSTİM OSTİM Hakkında. Available online: https://www.ostim.org.tr/sizin-fabrikaniz-ostim (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Yazıcıoğlu, Y.; Erdoğan, S. SPSS Uygulamalı Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemleri; 4th ed.; Detay Yayıncılık: Ankara, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sekeran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, G.D. Determining Sample Size. Available online: https://www.gjimt.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2_Glenn-D.-Israel_Determining-Sample-Size.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Carpenter, S. Ten Steps in Scale Development and Reporting: A Guide for Researchers. Communication Methods and Measures 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeele, V.V.; Spiel, K.; Nacke, L.; Johnson, D.; Gerling, K. Development and Validation of the Player Experience Inventory: A Scale to Measure Player Experiences at the Level of Functional and Psychosocial Consequences. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2020, 135, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, J.; McGehee, N.; Knollenberg, W. Developing and Testing the Transformative Travel Experience Scale (TTES). Journal of Travel Research 2021, 60, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önem, Ş.; Selvi, M.S. General Attitude Scale for Social Media Influencers. MMI 2024, 15, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity. Personnel Psychology 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Gyimóthy, S. Too Afraid to Travel? Development of a Pandemic (COVID-19) Anxiety Travel Scale (PATS). Tourism Management 2021, 84, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, M.D.; Visvizi, A.; Chopdar, P.K.; Sarirete, A.; Alhalabi, W. Information Management in Smart Cities: Turning End Users’ Views into Multi-Item Scale Development, Validation, and Policy-Making Recommendations. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 56, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Chatterjee,Sheshadri; Dwivedi,Yogesh K. ; and Akter, S. Understanding Dark Side of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Integrated Business Analytics: Assessing Firm’s Operational Inefficiency and Competitiveness. European Journal of Information Systems 2022, 31, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: New Developments in Creating Objective Measuring Instruments. Psychol Assess 2019, 31, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Cai, R.; Gursoy, D. Developing and Validating a Service Robot Integration Willingness Scale. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2019, 80, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, C.W.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Seven edition.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, 2014; ISBN 978-1-292-02190-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck, R.; O’Dell, L.L. Applications of Standard Error Estimates in Unrestricted Factor Analysis: Significance Tests for Factor Loadings and Correlations. Psychological Bulletin 1994, 115, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Arizmendi, C.; Gates, K.M. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) Programs in R. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.L. A Rationale and Test for the Number of Factors in Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.-J.; Cheng, C.-P. Parallel Analysis with Unidimensional Binary Data. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2005, 65, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Elo, S.; Pölkki, T.; Miettunen, J.; Kyngäs, H. Testing and Verifying Nursing Theory by Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2011, 67, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottem, E. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the WPPSI for Language-Impaired Children. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2003, 44, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yaşlıoğlu, M.M. Sosyal Bilimlerde Faktör Analizi ve Geçerlilik: Keşfedici ve Doğrulayıcı Faktör Analizlerinin Kullanılması. İstanbul Üniversitesi İşletme Fakültesi Dergisi 2017, 46, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, T.A.; Worthington, R.L. Item Response Theory in Scale Development Research: A Critical Analysis. The Counseling Psychologist 2016, 44, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, D.; Bozman, C.; McPherson, M.; Valente, F.; Zhang, A. Information Entropy and Scale Development. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 2021, 9, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Miles, J.N.V.; Davies, M.N.O.; Walker, S. Coefficient Alpha: A Useful Indicator of Reliability? Personality and Individual Differences 2000, 28, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhadar, I.; Yang, Y.; Paek, I. Consequences of Ignoring Guessing Effects on Measurement Invariance Analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement 2021, 45, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.W.; and Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-P.; Lee, L.; Chou, C.J. Correlations among Product Development, Product Innovation, and Green Marketing in Healthcare Industry. RCIS 2024, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, D.; Cheng, S.; Shi, Y.; Ma, X. Analysis on the Path of Agricultural Scientific Research Institutes to Promote the Industrialization of Intellectual Property. Hubei Agricultural Sciences 2021, 60, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akude, D.N.; Akuma, J.K.; Kwaning, E.A.; Asiama, K.A. Green Marketing Practices and Sustainability Performance of Manufacturing Firms: Evidence from Emerging Markets. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology 2025, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-H.; Song, J. Effect of Eco-Friendly Management of Golf Clubs on Golfers’ Behavioral Intention to Return: Green Image, Perceived Quality as Meditator and Green Marketing as Moderator 2025.

| Item No | NE | CVR | Comment | Item No | NE | CVR | Comment |

| 1 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 42 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 2 | 1 | -0.80 | Eliminated | 43 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 3 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 44 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 4 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 45 | 6 | 0,20 | Eliminated |

| 5 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 46 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 6 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 47 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 7 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 48 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 8 | 2 | -0,60 | Eliminated | 49 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 9 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 50 | 8 | 0,60 | Eliminated |

| 10 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 51 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 11 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 52 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 12 | 7 | 0,40 | Eliminated | 53 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 13 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 54 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 14 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 55 | 4 | -0,20 | Eliminated |

| 15 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 56 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 16 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 57 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 17 | 8 | 0,60 | Eliminated | 58 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 18 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 59 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 19 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 60 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 20 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 61 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 21 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 62 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 22 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 63 | 7 | 0,40 | Eliminated |

| 23 | 5 | 0,00 | Eliminated | 64 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 24 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 65 | 8 | 0,60 | Eliminated |

| 25 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 66 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 26 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 67 | 4 | -0,20 | Eliminated |

| 27 | 8 | 0,60 | Eliminated | 68 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 28 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 69 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 29 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 70 | 5 | 0,00 | Eliminated |

| 30 | 8 | 0,60 | Eliminated | 71 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 31 | 7 | 0,40 | Eliminated | 72 | 5 | 0,00 | Eliminated |

| 32 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 73 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 33 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 74 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 34 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 75 | 6 | 0,20 | Eliminated |

| 35 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 76 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 36 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained | 77 | 2 | -0,60 | Eliminated |

| 37 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 78 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 38 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 79 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained |

| 39 | 4 | -0,20 | Eliminated | 80 | 7 | 0,40 | Eliminated |

| 40 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 81 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| 41 | 10 | 1,00 | Remained | 82 | 9 | 0,80 | Remained |

| Nu. | Items |

| 1 | We design products to save energy with reduced materials |

| 2 | We design for remanufacturing so that waste can be recycled. |

| 3 | With the green packaging approach, our materials are less damaged (such as breakage, deterioration) |

| 4 | Green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste |

| 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. |

| 6 | Green packaging practices reduce costs. |

| 7 | We use recycled materials in our products. |

| 8 | We use recycled materials for packaging. |

| 9 | We consider the environment when designing the product. |

| 10 | We use ecological green materials in production. |

| 11 | Our suppliers' products are recyclable |

| 12 | We minimize our waste in production |

| 13 | We use renewable energy sources in production |

| 14 | Our company offers innovative green products to the market. |

| 15 | Green products provide our company with the opportunity to differentiate. |

| 16 | The raw materials we use are safe for the environment. |

| 17 | The production process in our enterprise is based on ISO 14001 certification. |

| 18 | Our company produces environmentally friendly products |

| 19 | Environment is a key criterion for supplier selection. |

| 20 | We support the green environmental components of the product. |

| 21 | A separate unit monitoring environmental costs has been established in our organization. |

| 22 | The use of recycled materials in our business reduces costs. |

| 23 | It is normal for green products to be priced slightly higher than other products. |

| 24 | Our customers are willing to pay high prices for green products. |

| 25 | We take environmental factors into account in our price policy. |

| 26 | We use local products to reduce transportation costs. |

| 27 | The use of Information Technologies in the enterprise reduces distribution costs |

| 28 | We cover the additional cost of a green product. |

| 29 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. |

| 30 | Our company tries to persuade its customers to be environmentally conscious during direct sales. |

| 31 | We utilize green vehicles in the distribution channel. |

| 32 | We use electronic information systems in green transportation. |

| 33 | Thanks to green transport, we use less fuel. |

| 34 | Thanks to green transportation, we can reduce costs by saving time on the shipment route |

| 35 | We monitor emissions from the distribution of the product. |

| 36 | The environmental aspect of our products is at the forefront in marketing. |

| 37 | Our environmental practices are updated on our website. |

| 38 | Our company chooses packaging materials from degradable products. |

| 39 | Our business is trying to reduce the use of packaging. |

| 40 | Our business uses environmentally friendly green label. |

| 41 | The labels contain information on recycling. |

| 42 | We prevent the use of hazardous substances in packaging. |

| 43 | The amount of handling of goods is minimized to increase delivery flexibility. |

| 44 | The warehouse of our business is organized with environmentally friendly methods. |

| 45 | We use integrated transportation systems in distribution |

| 46 | We choose cleaner transportation systems |

| 47 | We use green arguments in marketing communication. |

| 48 | Our marketing communications reflect the company's commitment to the environment. |

| 49 | Environmental claims in advertising are often met with criticism from the environment (competitors, consumer organizations, etc.). |

| 50 | The company cooperates with environmental groups to effectively promote “green image" |

| 51 | Environmental labeling is an effective promotional tool for our company. |

| 52 | We inform consumers about environmental management in the company |

| 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities on environmental issues. |

| 54 | We use specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. |

| 55 | When promoting our products, we prefer digital communication as it is more environmentally friendly |

| 56 | We implement paperless policy in our procurement as much as possible. |

| 57 | We emphasize the image of "green business" in promotional activities |

| 58 | Our company uses factual statements in product advertisements. |

| 59 | Our image as an environmentally friendly company gives us a competitive advantage. |

| 60 | We emphasize in our advertisements that our products are green. |

| 61 | Green identical to the environment dominates the product packaging. |

| 62 | Our product promotions include environmental protection activities. |

| Variable | Group | n | % | Variable | Group | n | % |

| Sex | Female | 53 | 33.33 | Experience | Less than 5 years | 23 | 14.50 |

| Male | 106 | 66.67 | 6-10 years | 55 | 34.60 | ||

| Age | 30 and below | 43 | 27.00 | 11-15 years | 38 | 23.90 | |

| 31-40 years | 37 | 23.30 | 16-20 years | 22 | 13.80 | ||

| 41-50 years | 48 | 30.20 | 21 years and above | 21 | 13.20 | ||

| 51 and above | 31 | 19.50 | Position | Lower level manager | 39 | 24.50 | |

| Marital Status |

Married | 92 | 57.90 | Middle manager | 61 | 38.40 | |

| Single | 67 | 42.10 | Senior executive | 45 | 28.30 | ||

| Educational Level | High school and below | 21 | 13.20 | Boss (business owner) | 14 | 9.80 | |

| Associate degree | 34 | 21.40 | |||||

| Undergraduate | 71 | 44.60 | |||||

| Postgraduate | 33 | 20.80 | |||||

| Scale | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | Central Tendency Measurements | |||||||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Mean | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | |||

| GMMPC | 0,101 | 159 | 0,000 | 3,417 | 3,583 | -0,727 | 0,539 | ||

| Statements | Factor Load Value (SPSS) |

Cron. Alfa (α) |

PA Results | |||

| (Ncases: 159; Nvar: 12; Ndataset:100; Percent: 95; Brian Oc) | ||||||

| Raw Data | Means | Percently | ||||

| Dimension 1 | α= 0,869 | 6,147 | 1,473 | 1,584 | ||

| % of Variance: 46,564 ;Eigen-value: 6,147 | ||||||

| GMMPC 52 | We inform consumers about the environmental management within our company | 0,730 | ||||

| GMMPC 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities related to environmental issues. | 0,760 | ||||

| GMMPC 54 | We utilize specific environmental criteria for our suppliers | 0,820 | ||||

| GMMPC 57 | We emphasize the 'eco-friendly business' image in our promotional activities. | 0,645 | ||||

| GMMPC 60 | We highlight the green attributes of our products in our advertisements. | 0,601 | ||||

| Dimension 2 | α= 0,854 | 1,419 | 1,352 | 1,419 | ||

| % Of Variance: 8,940 ;Eigen-Value: 1,419 | ||||||

| GMMPC 3 | Our materials sustain less damage (such as breakage, spoilage) due to our green packaging approach | -0,666 | ||||

| GMMPC 4 | The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | -0,982 | ||||

| GMMPC 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | -0,704 | ||||

| Dimension 3 | α= 0,842 | 1,347 | 1,254 | 1,320 | ||

| % Of Variance: 5,325 ;Eigen-Value: 1,347 | ||||||

| GMMPC 31 | We utilize green vehicles in our distribution channel. | 0,764 | ||||

| GMMPC 33 | We use less fuel thanks to green transportation | 0,815 | ||||

| GMMPC 35 | We monitor emissions resulting from product distribution | 0,608 | ||||

| GMMPC 46 | We select cleaner transportation systems | 0,510 | ||||

| Extraction Method: Maximum Likelihood (ML) | ||||||

| Rotation Method: Direct Oblimin | ||||||

| KMO: 0,895; | ||||||

| Bartlett’s sphericity test; (χ2=1.033,152; df=66; p=,000) | ||||||

| Factors | No. of items | 1. Eigenvalue | 2. Eigenvalue |

3. Eigenvalue |

4. Eigenvalue |

Total Variance |

| GMMPC | 12 | 6,147 | 1,419 | 1,347 | 0,621 | 60,728 |

| Nu | Items |

| GMMPC 1 | We design products to save energy using reduced materials. |

| GMMPC 2 | We design for remanufacturing to facilitate waste recycling. |

| GMMPC 6 | Green packaging practices reduce our costs. |

| GMMPC 7 | We use recycled materials in our products. |

| GMMPC 8 | We use recycled materials for packaging. |

| GMMPC 9 | We consider the environment when designing products. |

| GMMPC 10 | We use ecological/green materials in production. |

| GMMPC 11 | Our suppliers' products are suitable for recycling. |

| GMMPC 12 | We minimize the amount of waste in our production processes. |

| GMMPC 13 | We use renewable energy sources in production. |

| GMMPC 14 | Our company offers innovative green products to the market. |

| GMMPC 15 | Green products provide our company with differentiation opportunities. |

| GMMPC 16 | The raw materials we use are safe for the environment. |

| GMMPC 17 | Our production process is based on the ISO 14001 certification. |

| GMMPC 18 | Our business produces environmentally friendly products. |

| GMMPC 19 | The environment is a key criterion in our supplier selection. |

| GMMPC 20 | We promote the green environmental components of the product. |

| GMMPC 21 | A separate unit has been established in our business to monitor environmental costs. |

| GMMPC 22 | Using recycled materials in our business reduces costs. |

| GMMPC 23 | It is normal for green products to be priced slightly higher than other products. |

| GMMPC 24 | Our customers accept paying higher prices for green products. |

| GMMPC 25 | We consider environmental factors in our pricing policy. |

| GMMPC 26 | We use local products to reduce transportation costs. |

| GMMPC 27 | The use of Information Technology (IT) in our business reduces distribution costs. |

| GMMPC 28 | We account for the additional cost of an environmentally friendly product. |

| GMMPC 29 | We consider environmental issues in distribution. |

| GMMPC 30 | Our company tries to persuade customers to be environmentally conscious during direct sales. |

| GMMPC 32 | We use electronic information systems in green transportation. |

| GMMPC 34 | Through green transportation, we can save time on shipment routes and reduce costs. |

| GMMPC 36 | The environmentally friendly aspect of our products is prominent in our marketing. |

| GMMPC 37 | Our environmentally friendly practices are updated on our website. |

| GMMPC 38 | Our business selects packaging materials from biodegradable products. |

| GMMPC 39 | Our business tries to reduce the use of packaging. |

| GMMPC 40 | Our business uses environmentally friendly green labels. |

| GMMPC 41 | Information regarding recycling is included on our labels. |

| GMMPC 42 | We avoid the use of hazardous materials in packaging. |

| GMMPC 43 | The quantity of goods handling is minimized to increase delivery flexibility. |

| GMMPC 44 | Our business's warehouse is organized using environmentally friendly methods. |

| GMMPC 45 | We use integrated transportation systems in distribution |

| GMMPC 47 | We use green arguments in our marketing communications. |

| GMMPC 48 | Our marketing communication reflects the company's commitment to the environment. |

| GMMPC 49 | Environmental claims in advertisements are often met with criticism from external parties (e.g., competitors, consumer organizations). |

| GMMPC 50 | The company collaborates with environmental groups to effectively promote its 'green image'. |

| GMMPC 51 | Environmental labeling is an effective promotional tool for our company. |

| GMMPC 55 | We prefer digital communication for promoting our products because it is more environmentally friendly. |

| GMMPC 56 | We implement a paperless policy in our procurement activities whenever possible. |

| GMMPC 58 | Our company uses truthful statements in its product advertisements. |

| GMMPC 59 | Our environmentally friendly company image provides us with a competitive advantage. |

| GMMPC 61 | The color green, synonymous with the environment, dominates our product packaging. |

| GMMPC 62 | Our product promotions include environmental protection activities. |

| No | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| 1 | GMMPC 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | GMMPC 4 | ,701** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | GMMPC 5 | ,579** | ,702** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | GMMPC 31 | ,407** | ,350** | ,379** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 5 | GMMPC 33 | ,326** | ,420** | ,340** | ,637** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 6 | GMMPC 35 | ,440** | ,402** | ,317** | ,529** | ,558** | 1 | |||||||||

| 7 | GMMPC 46 | ,466** | ,440** | ,362** | ,518** | ,560** | ,623** | 1 | ||||||||

| 8 | GMMPC 52 | ,319** | ,384** | ,374** | ,349** | ,321** | ,400** | ,450** | 1 | |||||||

| 9 | GMMPC 53 | ,445** | ,330** | ,344** | ,438** | ,403** | ,487** | ,530** | ,560** | 1 | ||||||

| 10 | GMMPC 54 | ,396** | ,429** | ,433** | ,414** | ,461** | ,472** | ,583** | ,600** | ,672** | 1 | |||||

| 11 | GMMPC 57 | ,399** | ,438** | ,494** | ,361** | ,416** | ,459** | ,460** | ,519** | ,490** | ,608** | 1 | ||||

| 12 | GMMPC 60 | ,451** | ,415** | ,490** | ,453** | ,425** | ,483** | ,528** | ,484** | ,557** | ,582** | ,626** | 1 | |||

| 13 | GMMPC 1st dimension |

,872** | ,909** | ,858** | ,431** | ,411** | ,441** | ,482** | ,407** | ,426** | ,476** | ,503** | ,514** | 1 | ||

| 14 | GMMPC 2nd dimension |

,499** | ,489** | ,424** | ,812** | ,830** | ,827** | ,824** | ,463** | ,566** | ,587** | ,516** | ,575** | ,537** | 1 | |

| 15 | GMMPC 3rd dimension |

,495** | ,492** | ,525** | ,497** | ,499** | ,567** | ,629** | ,787** | ,812** | ,856** | ,798** | ,795** | ,573** | ,667** | 1 |

| 16 | GMMPC | ,694** | ,700** | ,675** | ,680** | ,682** | ,722** | ,763** | ,674** | ,731** | ,775** | ,729** | ,753** | ,784** | ,865** | ,904** |

| X2(df) | p | RMSEA | CFI | GFI | SRMR | AVE | CR |

| 1.468 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.977 | 0.930 | 0.028 | 0.589 | 0.967 |

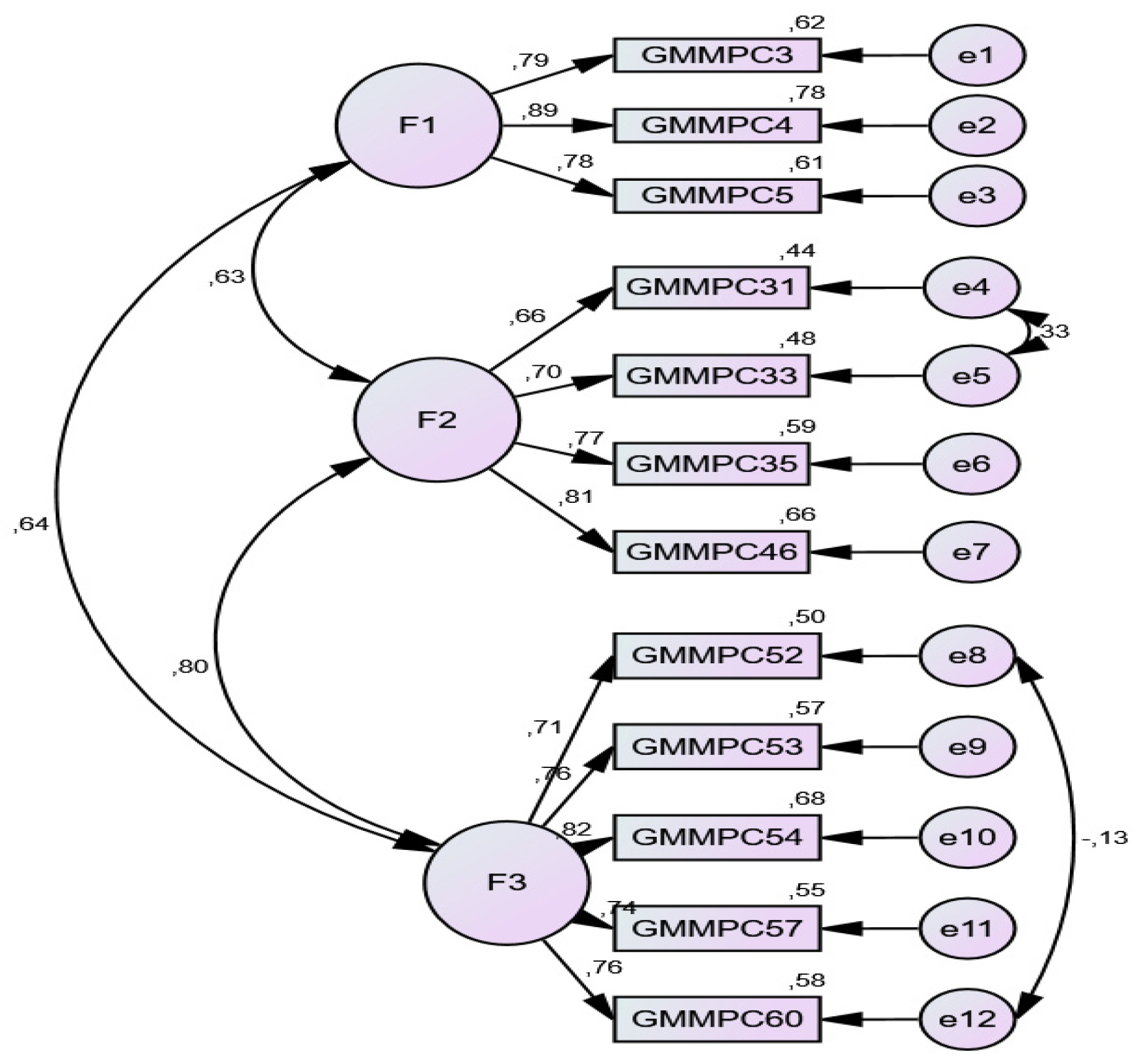

| Items | β1 | β2 | Ss | t | p | CR | AVE | ||

| Measurement Model | |||||||||

| GMMPC 3 | ← | 2 nd.dimension | 0,786 | 1,000 | 0,967 | 0,589 | |||

| GMMPC 4 | ← | 2nd.dimension | 0,886 | 1,053 | 0,095 | 11,123 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 5 | ← | 2 nd.dimension | 0,779 | 0,906 | 0,090 | 10,072 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 31 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,662 | 1,000 | |||||

| GMMPC 33 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,696 | 1,014 | 0,111 | 9,119 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 35 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,769 | 1,209 | 0,152 | 7,973 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 46 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,815 | 1,275 | 0,154 | 8,274 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 52 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,710 | 1,000 | |||||

| GMMPC 53 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,758 | 1,043 | 0,119 | 8,776 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 54 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,824 | 1,111 | 0,118 | 9,451 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 57 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,740 | 0,990 | 0,115 | 8,589 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 60 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,764 | 0,968 | 0,115 | 8,420 | <0,001 | ||

| Variable | Groups | F | % | Variable | Groups | F | % |

| Sex | Female | 163 | 42,1 | Use of Digital Marketing |

Yes | 295 | 76,2 |

| Male | 224 | 57,9 | No | 92 | 23,8 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Age | 30 and below | 94 | 24,3 | Importance of Digital Marketing | Low importance, | 33 | 8,5 |

| 31-40 years | 166 | 42,9 | Moderate importance | 89 | 23,0 | ||

| 41-50 years | 92 | 23,8 | High importance | 129 | 33,3 | ||

| 51 and above | 35 | 9,0 | Very high importance | 136 | 35,1 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Marital Status |

Married | 251 | 64,9 | Export | Yes | 232 | 59,9 |

| Single | 136 | 35,1 | No | 155 | 40,1 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Educational Level | High school and below | 49 | 12,7 | Existence of Carbon Offsetting System (e.g., tree planting | Yes | 149 | 38,5 |

| Associate Degree | 48 | 12,4 | No | 238 | 61,5 | ||

| Undergraduate | 203 | 52,5 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Postgraduate | 87 | 22,5 | Level of Knowledge Regarding Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) | Nothing | 62 | 16,0 | |

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Less | 104 | 26,9 | ||

| Position | Lower level manager | 84 | 21,7 | Middle | 142 | 36,7 | |

| Middle manager | 191 | 49,4 | More | 43 | 11,1 | ||

| Senior executive | 81 | 20,9 | Too much | 36 | 9,3 | ||

| Boss (business owner) | 31 | 8,0 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Expected Level of Impact of CBAM on the Business |

No impact | 58 | 15,0 | |

| Experience | Less than 5 years | 90 | 23,3 | Low impact | 73 | 18,9 | |

| 6-10 years | 93 | 24,0 | Moderate impact | 140 | 36,2 | ||

| 11-15 years | 94 | 24,3 | High impact | 78 | 20,2 | ||

| 16-20 years | 48 | 12,4 | Very high impact | 38 | 9,8 | ||

| 21 years and above | 62 | 16,0 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Reverse Logistics System |

Yes | 88 | 22,7 | |

| Length of Employment (at the company) | Between 1-5 years | 198 | 51,2 | No | 299 | 77,3 | |

| Between 6-10 years | 110 | 28,4 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Between 11-15 years | 40 | 10,3 | Use of Environmental Marks or Labels on Products | Yes | 215 | 55,6 | |

| Between 16-20 years | 13 | 3,4 | No | 172 | 44,4 | ||

| Between 21 years or more | 26 | 6,7 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Labels/Marks Used | CE | 78 | 20.2 | |

| Company's Years in Operation | Between 1-10 years | 144 | 37,2 | Recycling | 119 | 30.7 | |

| Between 11-20 years | 80 | 20,7 | Green Dot | 23 | 5.9 | ||

| Between 21-30 years | 77 | 19,9 | Eco-friendly, | 108 | 27.9 | ||

| Between 31-40 years | 27 | 7,0 | ÇEVKO, | 13 | 3,4 | ||

| Between 41 years | 59 | 15,2 | Ozone-friendly | 5 | 1.3 | ||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | Eco-label | 15 | 3.9 | ||

| Number of Employees | Between 100 employees or less | 217 | 56,1 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | |

| Between 101-200 employees | 54 | 14,0 | Expectation of an Increase in Personnel to be Employed for Green Jobs in the Future: | Yes | 283 | 73,1 | |

| Between 201-300 employees | 35 | 9,0 | No | 104 | 26,9 | ||

| Between 301-400 employees | 28 | 7,2 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | ||

| 401 employees or more | 53 | 13,7 | ISO 14001 Certification | Yes | 182 | 47,0 | |

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | No | 205 | 53,0 | ||

| Sector of Operation | IT/Technology Products | 94 | 24,3 | Total | 387 | 100,0 | |

| Food and Packaging Products | 100 | 25,8 | |||||

| Construction Products | 41 | 10,6 | |||||

| Machinery and Parts Manufacturing | 117 | 30,2 | |||||

| Medical, Optical, and Eyewear Manufacturing | 7 | 1,8 | |||||

| Defense Industry | 2 | ,5 | |||||

| Textile, Leather, and Leather Products | 10 | 2,6 | |||||

| Logistics | 6 | 1,6 | |||||

| Publishing House | 10 | 2,6 | |||||

| Total | 387 | 100,0 | |||||

| Sequence no. | Statements | 1-Strongly disagree | 2-Disagree |

3-Neither disagree nor agree |

4-Agree |

5-Strongly agree |

Mean | S.D. | |

| 1 | GMMPC 3- Our materials sustain less damage (such as breakage, spoilage) due to our green packaging approach. | f | 26 | 43 | 80 | 136 | 102 | 3,63 | 1,17 |

| % | 6,7 | 11,1 | 20,7 | 35,1 | 26,4 | ||||

| 2 | GMMPC 4- The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | f | 20 | 38 | 66 | 154 | 109 | 3,76 | 1,12 |

| % | 5,2 | 9,8 | 17,1 | 39,8 | 28,2 | ||||

| 3 | GMMPC 5- Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | f | 18 | 60 | 107 | 133 | 69 | 3,45 | 1,09 |

| % | 4,7 | 15,5 | 27,6 | 34,4 | 17,8 | ||||

| 4 | GMMPC 31- We utilize green vehicles in our distribution channel. | f | 29 | 77 | 122 | 88 | 71 | 3,25 | 1,18 |

| % | 7,5 | 19,9 | 31,5 | 22,7 | 18,3 | ||||

| 5 | GMMPC 33- We use less fuel thanks to green transportation. | f | 24 | 68 | 111 | 121 | 63 | 3,34 | 1,13 |

| % | 6,2 | 17,6 | 28,7 | 31,3 | 16,3 | ||||

| 6 | GMMPC 35- We monitor emissions resulting from product distribution. | f | 32 | 101 | 83 | 107 | 64 | 3,18 | 1,22 |

| % | 8,3 | 26,1 | 21,4 | 27,6 | 16,5 | ||||

| 7 | GMMPC 46- We select cleaner transportation systems. | f | 15 | 60 | 79 | 144 | 89 | 3,60 | 1,11 |

| % | 3,9 | 15,5 | 20,4 | 37,2 | 23,0 | ||||

| 8 | GMMPC 52- We inform consumers about the environmental management within our company. | f | 33 | 85 | 63 | 135 | 71 | 3,33 | 2,24 |

| % | 8,5 | 22,0 | 16,3 | 34,9 | 18,3 | ||||

| 9 | GMMPC 53- We participate in sponsorship activities related to environmental issues. | f | 21 | 69 | 69 | 138 | 90 | 3,53 | 1,18 |

| % | 5,4 | 17,8 | 17,8 | 35,7 | 23,3 | ||||

| 10 | GMMPC 54- We utilize specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | f | 26 | 54 | 60 | 162 | 85 | 3,58 | 1,17 |

| % | 6,7 | 14,0 | 15,5 | 41,9 | 22,0 | ||||

| 11 | GMMPC 57- We emphasize the 'eco-friendly business' image in our promotional activities. | f | 31 | 74 | 70 | 134 | 78 | 3,40 | 1,22 |

| % | 8,0 | 19,1 | 18,1 | 34,6 | 20,2 | ||||

| 12 | GMMPC 60- We highlight that our products are green in our advertisements. | f | 19 | 69 | 74 | 155 | 70 | 3,49 | 1,12 |

| % | 4,9 | 17,8 | 19,1 | 40,1 | 18,1 | ||||

| Scale and Sub-dimensions | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | Central Tendency Measurements | |||||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Mean | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| GMMPC | 0,083 | 387 | 0,000 | 3,461 | 3,583 | -0,512 | 0,026 |

| Items |

Factor Load value (SPSS) |

Cron. Alfa (α) |

PA Results | |||

| (Ncases: 387; Nvar: 12; Ndataset:100; Percent: 95; Brian Oc) | ||||||

| Raw Data | Means | Percently | ||||

| 1 st dimension | α= 0,855 | 6,132 | 1,297 | 1,346 | ||

| % of Variance: 47,755 ;Eigen-value: 6,132 | ||||||

| GMMPC 52 | We inform consumers about the environmental management within our company. | 0,819 | ||||

| GMMPC 53 | We participate in sponsorship activities related to environmental issues. | 0,726 | ||||

| GMMPC 54 | We utilize specific environmental criteria for our suppliers. | 0,847 | ||||

| GMMPC 57 | We emphasize the 'eco-friendly business' image in our promotional activities. | 0,648 | ||||

| GMMPC 60 | We highlight that our products are green in our advertisements. | 0,491 | ||||

| 2 nd dimension | α= 0,858 | 1,334 | 1,217 | 1,265 | ||

| % Of Variance: 8,450 ;Eigen-Value: 1,334 | ||||||

| GMMPC 3 | Our materials sustain less damage (such as breakage, spoilage) due to our green packaging approach. | -0,793 | ||||

| GMMPC 4 | The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste. | -0,946 | ||||

| GMMPC 5 | Green packaging practices make our products even lighter. | -0,690 | ||||

| 3 rd dimension | α= 0,876 | 1,208 | 1,158 | 1,200 | ||

| % Of Variance: 6,437 ;Eigen-Value: 1,208 | ||||||

| GMMPC 31 | We utilize green vehicles in our distribution channel. | 0,863 | ||||

| GMMPC 33 | We use less fuel thanks to green transportation. | 0,847 | ||||

| GMMPC 35 | We monitor emissions resulting from product distribution. | 0,611 | ||||

| GMMPC 46 | We select cleaner transportation systems. | 0,543 | ||||

| Extraction Method: Maximum Likelihood (ML) | ||||||

| Rotation Method: Direct Oblimin | ||||||

| KMO: 0,905; | ||||||

| Bartlett’s sphericity test; (χ2=2.620,395; df=66; p=,000) | ||||||

| X2(df) | p | RMSEA | CFI | GFI | SRMR | AVE | CR |

| 2.563 | 0.000 | 0.064 | 0.970 | 0.949 | 0.037 | 0.605 | 0.970 |

| Factors | No. of items | 1. Eigenvalue | 2. Eigenvalue |

3. Eigenvalue |

4. Eigenvalue |

Total Variance |

| GMMPC | 12 | 6,132 | 1,334 | 1,208 | 0,561 | 62,603 |

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| GMMPC 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| GMMPC 4 | ,743** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| GMMPC 5 | ,603** | ,641** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| GMMPC 31 | ,390** | ,324** | ,346** | 1 | |||||||||||

| GMMPC 33 | ,352** | ,367** | ,297** | ,704** | 1 | ||||||||||

| GMMPC 35 | ,419** | ,358** | ,291** | ,589** | ,573** | 1 | |||||||||

| GMMPC 46 | ,426** | ,372** | ,327** | ,562** | ,586** | ,601** | 1 | ||||||||

| GMMPC 52 | ,369** | ,384** | ,343** | ,326** | ,339** | ,406** | ,463** | 1 | |||||||

| GMMPC 53 | ,468** | ,375** | ,339** | ,455** | ,442** | ,503** | ,547** | ,599** | 1 | ||||||

| GMMPC 54 | ,464** | ,436** | ,427** | ,394** | ,395** | ,431** | ,509** | ,641** | ,682** | 1 | |||||

| GMMPC 57 | ,430** | ,420** | ,434** | ,408** | ,412** | ,432** | ,413** | ,599** | ,530** | ,635** | 1 | ||||

| GMMPC 60 | ,463** | ,378** | ,431** | ,468** | ,433** | ,494** | ,529** | ,493** | ,585** | ,540** | ,551** | 1 | |||

| GMMPC 1st dimension |

,894** | ,903** | ,844** | ,402** | ,385** | ,406** | ,427** | ,415** | ,449** | ,503** | ,486** | ,482** | 1 | ||

| GMMPC 2nd dimension |

,474** | ,424** | ,376** | ,853** | ,851** | ,831** | ,815** | ,457** | ,581** | ,515** | ,497** | ,574** | ,483** | 1 | |

| GMMPC 3 rd. dimension |

,535** | ,487** | ,482** | ,500** | ,493** | ,553** | ,600** | ,820** | ,829** | ,855** | ,815** | ,768** | ,570** | ,640** | 1 |

| GMMPC | ,713** | ,672** | ,634** | ,696** | ,687** | ,715** | ,738** | ,702** | ,764** | ,767** | ,736** | ,742** | ,765** | ,846** | ,907** |

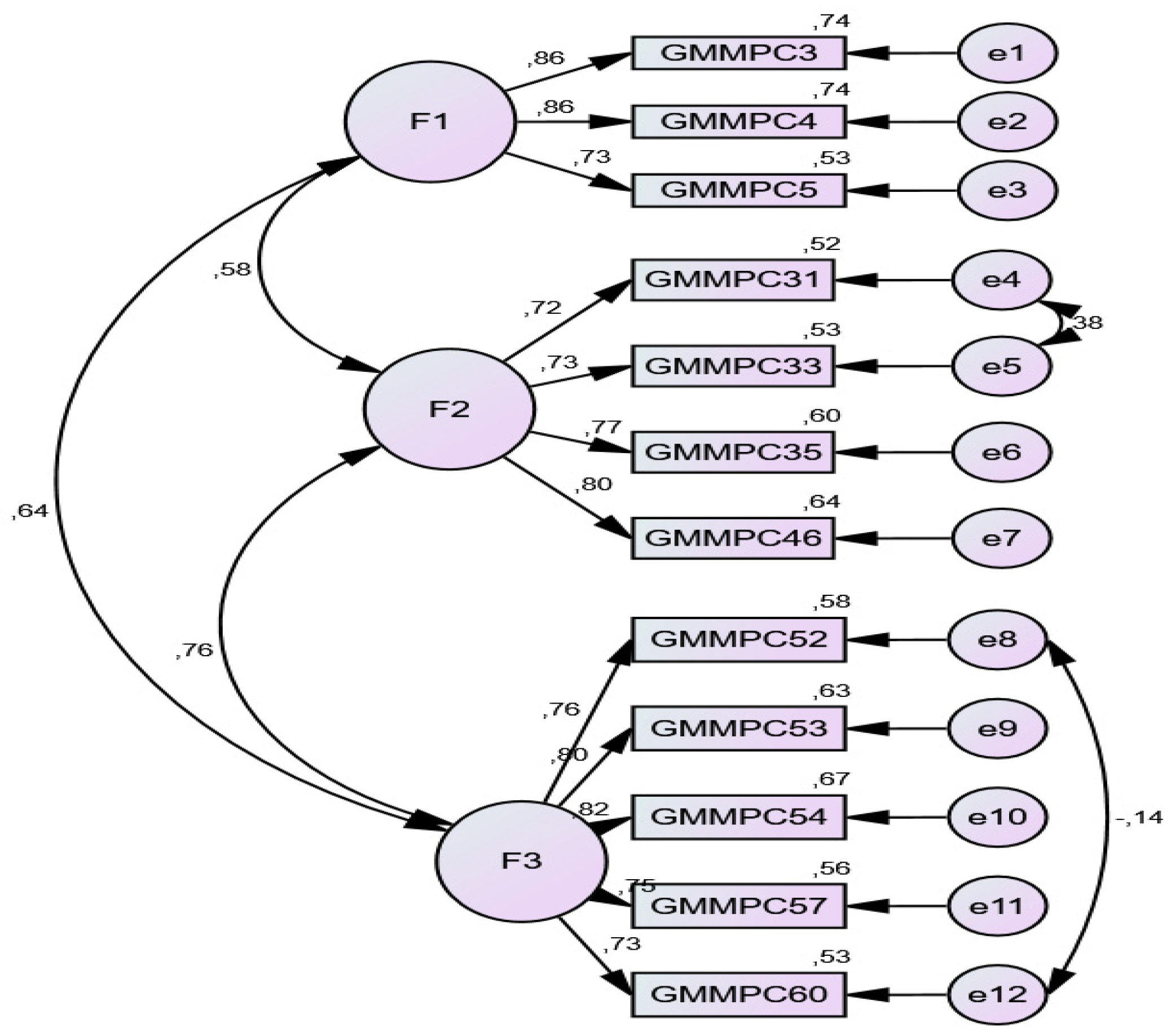

| Items | β1 | β2 | Ss | t | p | CR | AVE | ||

| Measurement model | |||||||||

| GMMPC 3 | ← | 2 nd.dimension | 0,860 | 1,000 | 0,970 | 0,605 | |||

| GMMPC 4 | ← | 2nd.dimension | 0,860 | 0,951 | 0,051 | 18,742 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 5 | ← | 2 nd.dimension | 0,728 | 0,785 | 0,050 | 15,642 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 31 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,723 | 1,000 | |||||

| GMMPC 33 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,725 | 0,957 | 0,057 | 16,705 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 35 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,774 | 1,108 | 0,082 | 13,590 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 46 | ← | 3 rd. dimension | 0,798 | 1,041 | 0,075 | 13,904 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 52 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,759 | 1,000 | |||||

| GMMPC 53 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,796 | 0,999 | 0,064 | 15,662 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 54 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,819 | 1,016 | 0,063 | 16,139 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 57 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,746 | 0,973 | 0,067 | 14,622 | <0,001 | ||

| GMMPC 60 | ← | 1 st dimension | 0,730 | 0,872 | 0,065 | 13,484 | <0,001 | ||

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | SRMR | CFI | RMSEA | ∆χ2 | ∆df | ∆CFI | p-value for ∆χ2 | |

| Grup1 | 71,927 | 49 | 1,468 | 0,028 | 0,977 | 0,054 | - | - | - | ||

| Grup2 | 125,574 | 49 | 2,563 | 0,037 | 0,970 | 0,064 | - | - | - | ||

|

Model 1: Configural |

197,501 | 98 | 2,015 | 0,037 | 0,972 | 0,043 | - | - | - | ||

| Model 2: Weak (Metric) | 202,34 | 107 | 1,891 | 0,036 | 0,973 | 0,04 | 4,839 | 9 | 0,001 | 0,024 | |

| Model 3: Scalar | 204,106 | 113 | 1,806 | 0,036 | 0,975 | 0,038 | 1,766 | 6 | 0,002 | 0,009 | |

| Model 4: Strong | 214,827 | 127 | 1,692 | 0,037 | 0,976 | 0,036 | 10,721 | 14 | 0,001 | 0,050 | |

|

Model 5: Partial (GMMPC 3-a1) |

198,481 | 99 | 2,005 | 0,037 | 0,972 | 0,043 | 16,346 | 28 | 0,004 | 0,082 | |

| ∆χ2: χ2 change (|χ2n- χ2n-1|); ∆df: df change (|dfn-dfn-1|); ∆χ2/df: χ2/df change (|χ2n/ dfn -| χ2n-1/ dfn-1); ∆CFI: CFI change (|CFIn- CFIn-1|); ∆CFI<0,01**; p-value for ∆χ2: χ2 significance value of change (p<0,05*) | |||||||||||

|

Factors (Sub-dimensions) |

GMMPC Scale items | Factor loading | |

|

1 st.dimension: Environmental publicity |

We inform consumers about the environmental management within our company | 0.819 | |

| We participate in sponsorship activities related to environmental issues. | 0.726 | ||

| We utilize specific environmental criteria for our suppliers | 0.847 | ||

| We emphasize the 'eco-friendly business' image in our promotional activities | 0.648 | ||

| We highlight that our products are green in our advertisements | 0.491 | ||

|

2 nd.dimension: Green Packaging |

Our materials sustain less damage (such as breakage, spoilage) due to our green packaging approach. | 0.793 | |

| The green packaging approach reduces our packaging waste | 0.946 | ||

| Green packaging practices make our products even lighter | 0.690 | ||

|

3 rd.dimension: Green Distribution |

We utilize green vehicles in our distribution channel | 0.863 | |

| We use less fuel thanks to green transportation | 0.847 | ||

| We monitor emissions resulting from product distribution | 0.611 | ||

| We select cleaner transportation systems | 0.543 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).