1. Introduction

The confluence of mounting environmental imperatives and evolving consumer consciousness has precipitated a fundamental paradigm shift in contemporary marketing practice and consumer behaviour [

1,

2]. With environmental sustainability transitioning from peripheral concern to strategic imperative, the global green market is anticipated to constitute 10% of aggregate world market capitalisation by 2030, propelled by technological advancement and increasing consumer accessibility to environmentally superior alternatives [

3]. This evolution is particularly pronounced within technology sectors, where sustainable innovations such as electric vehicles and energy-efficient consumer electronics have achieved mainstream market penetration, demonstrating that environmental attributes need not compromise functional performance [

4].

Nevertheless, a persistent and theoretically significant paradox emerges between consumers' stated environmental preferences and their observable purchasing behaviours, creating what marketing scholars term the "attitude-behaviour gap" [

5,

6]. This phenomenon represents one of the most enduring challenges in consumer behaviour research, with implications extending beyond individual purchase decisions to encompass broader questions of sustainable consumption and corporate environmental strategy.

Green brand positioning has evolved as a strategic marketing response to this challenge, representing a sophisticated approach to brand differentiation predicated upon environmental stewardship and sustainability credentials [

7,

8]. Conceptually grounded in positioning theory [

9], this approach integrates functional, emotional, and environmental value propositions to create differentiated brand identities that ostensibly align with consumers' environmental values. However, empirical evidence regarding the efficacy of green brand positioning in translating environmental attitudes into purchase behaviours remains equivocal, with studies reporting outcomes ranging from strong positive effects [

10,

11] to consumer scepticism and potential backlash [

12,

13].

Contemporary marketing literature offers several theoretical lenses through which to examine these relationships. Self-congruence theory, rooted in social psychology and extensively validated within consumer behaviour contexts, posits that individuals demonstrate preference for brands whose imagery corresponds with their self-concept [

14,

15]. Within environmental marketing contexts, this suggests that green brand positioning may influence purchase intention through its alignment with consumers' environmental self-identity. Conversely, functional congruence theory emphasises the primacy of utilitarian product attributes, suggesting that environmental positioning must not compromise perceived functional performance [

16]. This theoretical tension reflects broader debates within sustainability marketing regarding the relative salience of symbolic versus functional benefits.

The moderating influence of contextual factors introduces additional theoretical complexity. Product involvement, conceptualised as the personal relevance and importance consumers ascribe to product categories, may systematically influence information processing and decision-making heuristics [

17]. High-involvement contexts typically promote systematic information processing, potentially amplifying the influence of congruence mechanisms, whilst low-involvement scenarios may favour peripheral cues and simplified decision rules [

18]. Similarly, product optionality—the extent of choice alternatives available to consumers—may influence the cognitive trade-offs between environmental and functional considerations [

19]. However, empirical investigation of these moderating mechanisms within green marketing contexts remains nascent.

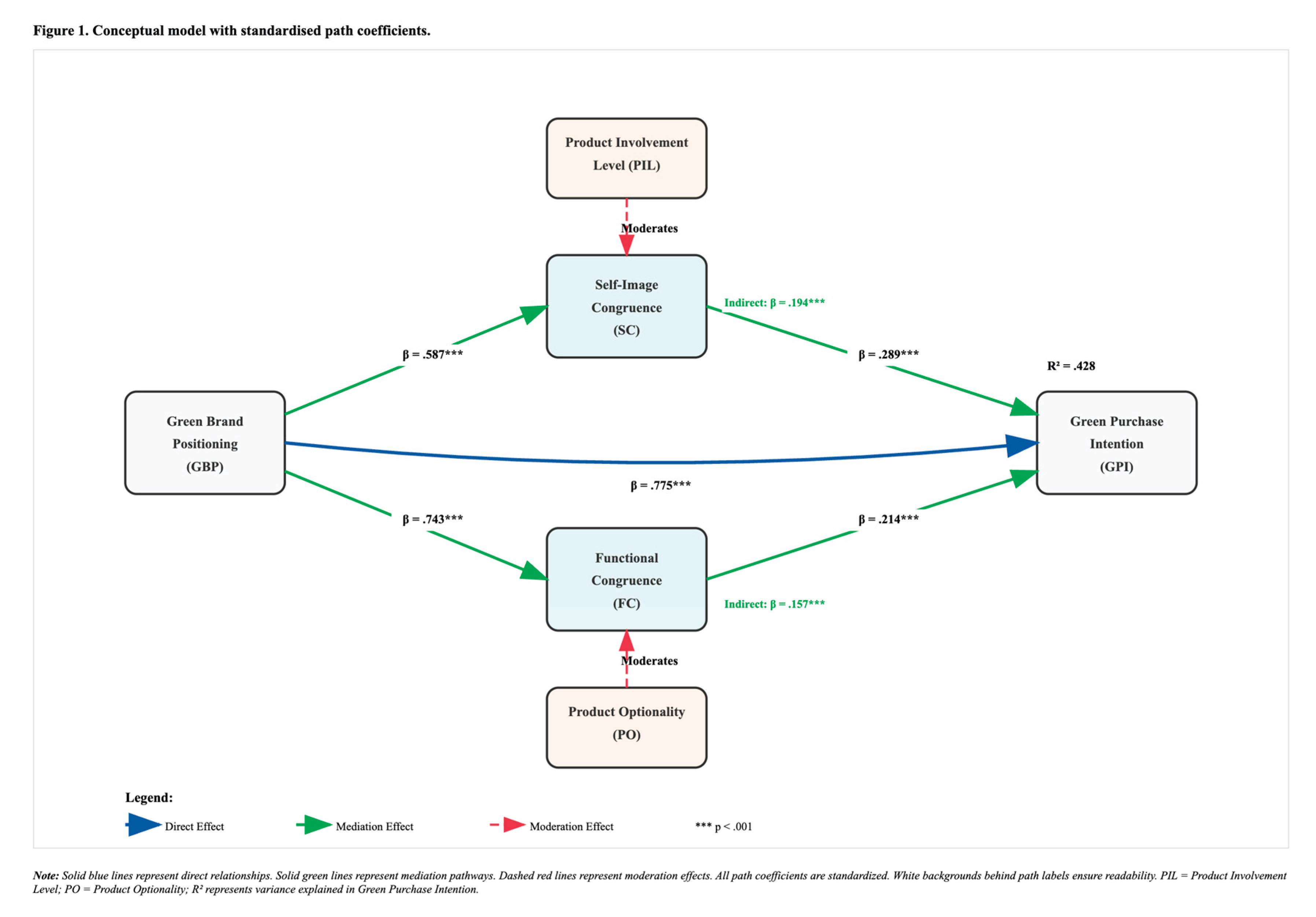

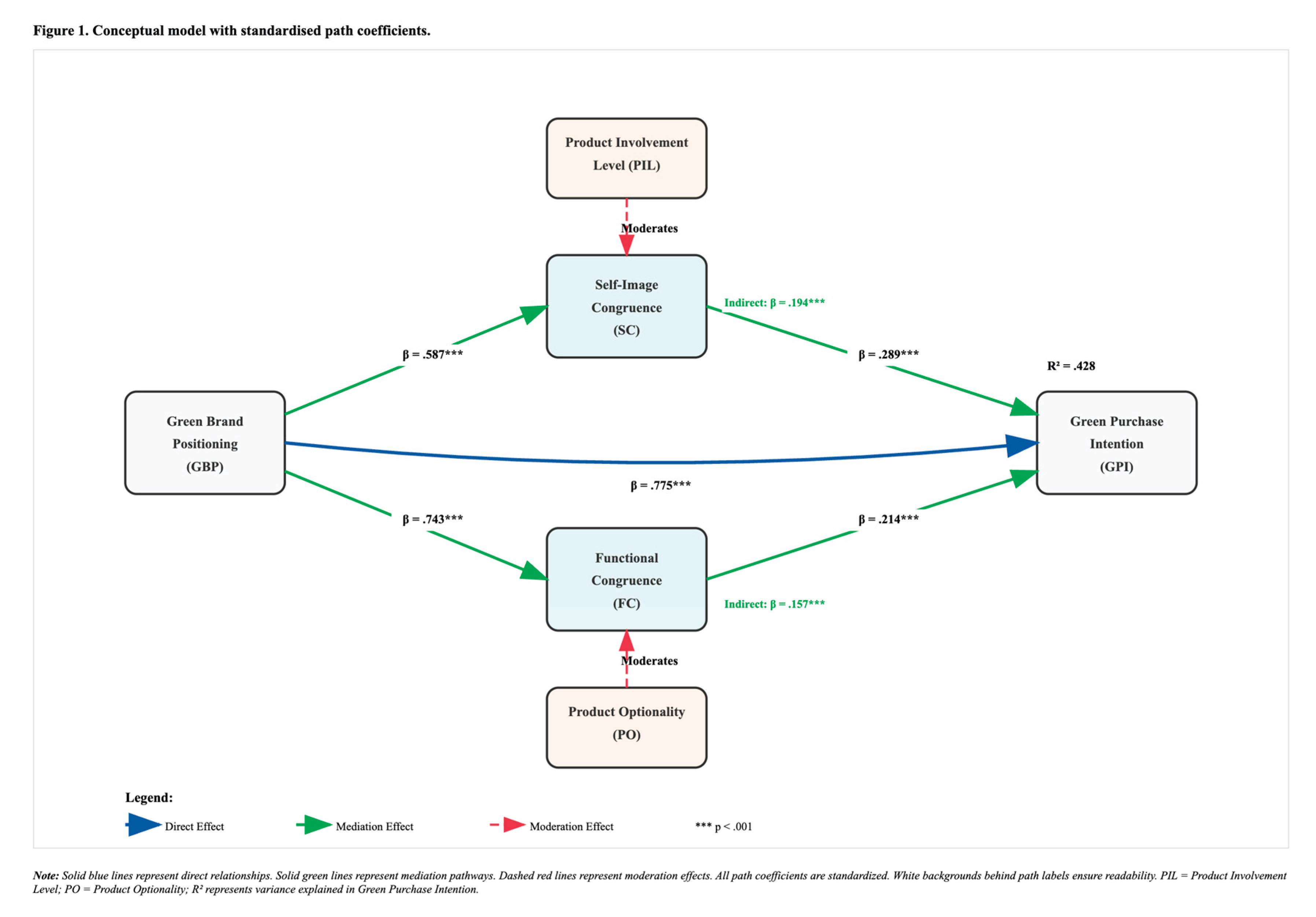

This research addresses these theoretical gaps through a comprehensive examination of how green brand positioning influences consumer purchase intention for green technology products. Specifically, we investigate the mediating roles of self-image congruence and functional congruence, whilst simultaneously examining the moderating effects of product involvement level and product optionality. Utilising survey data from 354 US consumers with demonstrable technology product experience, we employ structural equation modelling to test these theoretically-derived hypotheses. Our findings reveal that green brand positioning exerts significant positive influence on purchase intention (β = 0.775, p < 0.001), with self-image congruence accounting for 21.5% of this relationship through partial mediation. Functional congruence similarly demonstrates significant mediating effects, whilst product involvement level positively moderates the self-image congruence pathway and product optionality negatively moderates the functional congruence mechanism. These findings advance theoretical understanding of green consumer behaviour whilst providing actionable insights for marketing practitioners seeking to optimise environmental positioning strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design and Theoretical Framework

This study employed a cross-sectional quantitative research design to examine the relationships between green brand positioning, consumer purchase intention, and associated mediating and moderating variables. The research framework was grounded in self-congruence theory [

14] and functional congruence theory [

16], integrated within a broader consumer behaviour paradigm examining environmental purchasing decisions.

Participant Recruitment and Sample Characteristics

Participants were recruited through the Prolific platform (

www.prolific.co), a established online research platform that provides access to pre-screened participant pools with verified demographic and psychographic characteristics. The platform was selected for its robust participant verification procedures and established protocols for academic research [

20].

The final sample comprised 354 participants meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) United States residency; (2) age range 18-35 years; (3) possession of minimum bachelor's degree qualification; (4) demonstrated experience with technology product categories; and (5) self-reported environmental awareness. These criteria were established to ensure participants possessed sufficient cognitive engagement and domain knowledge to provide meaningful responses regarding green technology products [

21].

The demographic composition of the sample was as follows: 61.9% male, 38.1% female; age distribution of 7.1% (18-22 years), 34.7% (23-28 years), 50.3% (29-34 years), and 7.9% (35+ years); educational attainment of 70.9% bachelor's degree, 22.3% master's degree, and 6.8% doctoral degree; household income distribution of 17.5% (<$2,000 monthly), 48.6% ($2,000-$5,000 monthly), and 33.9% (>$5,000 monthly).

Stimulus Materials and Brand Selection

Green technology brands were operationalised through a pre-validated set of companies recognised for environmental initiatives and energy efficiency programmes. The brand portfolio comprised: Apple, Samsung, Hewlett-Packard (HP), Dell, Philips, Lucky Goldstar (LG), Nokia, Xiaomi, Huawei, and Lenovo. These brands were selected based on government and academic recognition for energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emission reduction initiatives [

22], ensuring ecological validity of the green technology positioning construct.

Instrumentation and Measurement Scales

The survey instrument consisted of two primary sections designed to capture both demographic characteristics and theoretical constructs of interest.

Section 1: Demographics and Brand Familiarity

Participants provided demographic information and assessed their familiarity with the specified green technology brands using established brand familiarity scales [

23].

Section 2: Construct Measurement

All theoretical constructs were measured using validated scales adapted from established marketing literature, employing seven-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) to ensure adequate response variance and statistical power [

24].

Green Brand Positioning (GBP) was operationalised as a multidimensional construct encompassing functional, environmental, and emotional positioning dimensions, adapted from Hartmann et al. [

25], Huang et al. [

26], Mohd Suki [

27], and Wang [

28]. The functional positioning subscale comprised five items assessing product safety, quality, comfort, durability, and trustworthiness. Environmental positioning included four items measuring energy efficiency, advanced technology utilisation, eco-labelling, and ISO certification. Emotional positioning incorporated four items evaluating innovation, family orientation, respect, and user-friendliness.

Self-Image Congruence (SC) was measured using a four-item scale adapted from Dai and Sheng [

29], assessing the perceived alignment between brand image and various dimensions of self-concept (actual self, perceived self, others' perceptions, and others' views).

Functional Congruence (FC) employed a three-item scale adapted from Li and Fang [

30] and Roca et al. [

31], measuring satisfaction with functional attribute performance relative to expectations.

Product Optionality (PO) was assessed using a four-item scale derived from Gatignon et al. [

32], evaluating consumer preferences for product choice variety and satisfaction with available options.

Product Involvement Level (PIL) utilised an eight-item scale based on Zaichkowsky [

33], measuring cognitive and emotional engagement with green technology products, including information-seeking behaviour, comparative evaluation, and product understanding.

Green Purchase Intention (GPI) was measured using a four-item scale synthesised from Chan [

34], Chaudhary and Bisai [

35], Dai and Sheng [

29], Huang et al. [

26], and Mohd Suki [

27], assessing likelihood of future green technology purchases motivated by environmental considerations.

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection was conducted entirely online through the Prolific platform's secure survey infrastructure. Participants provided informed consent before proceeding to the survey instruments. The average completion time was approximately 15 minutes, with attention check questions embedded throughout to ensure data quality [

36]. Participants received monetary compensation consistent with Prolific platform standards.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 28.0 with the PROCESS macro procedure version 4.2 beta developed by Hayes [

37]. The analytical approach comprised several stages:

Descriptive Analysis: Examination of variable distributions, central tendencies, and bivariate correlations

Measurement Model Assessment: Evaluation of scale reliability using Cronbach's alpha and construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis [

38]

Mediation Analysis: Testing of indirect effects using bootstrapping procedures with 5,000 resamples and 95% confidence intervals [

39]

Moderated Mediation Analysis: Examination of conditional indirect effects using PROCESS models 7 and 14 [

37]

Robustness Checks: Alternative model specifications and sensitivity analyses

All statistical tests employed α = 0.05 significance criteria, with effect sizes reported using standardised coefficients. Missing data were handled through listwise deletion given the low incidence (<2%) of incomplete responses [

40].

Ethical Considerations

This research received ethical approval from the institutional review board (approval code: [to be provided upon journal requirements]). All participants provided informed consent, and data collection procedures adhered to established ethical guidelines for online research [

41]. Participant anonymity was maintained throughout data collection and analysis phases.

Data and Code Availability

All survey instruments, raw data files, and analytical code will be made available through an open-access repository upon publication acceptance. SPSS syntax files and PROCESS macro commands are included to ensure complete replicability of reported analyses.

Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence was employed solely for superficial text editing purposes, including grammar correction, spelling verification, punctuation standardisation, and formatting consistency. No AI assistance was utilised in study design, data collection, statistical analysis, or interpretation of findings.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics and Preliminary Analyses

The final analytical sample comprised 354 participants recruited through systematic sampling procedures via the Prolific platform. Demographic profiling revealed a sample composition aligned with the target population parameters, facilitating generalisation to the broader demographic of educated technology consumers within the United States market. Gender distribution demonstrated moderate male predominance (61.9%, n = 219) relative to female participants (38.1%, n = 135), reflecting typical technology adoption patterns documented in extant literature [

42].

Age stratification concentrated within the theoretically relevant demographic cohorts, with participants aged 29-34 years constituting the modal category (50.3%, n = 178), succeeded by the 23-28 years demographic (34.7%, n = 123). This distribution aligns with established consumer behaviour research identifying these cohorts as primary adopters of green technology innovations [

43]. Educational attainment demonstrated substantial human capital endowments, with 70.9% (n = 251) possessing bachelor's degrees, 22.3% (n = 79) holding master's qualifications, and 6.8% (n = 24) having completed doctoral studies. Income distribution patterns reflected middle-to-upper middle-class economic positioning, with 48.6% (n = 172) reporting monthly household incomes of

$2,000-

$5,000, 33.9% (n = 120) exceeding

$5,000, and 17.5% (n = 62) below

$2,000.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and sample composition.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and sample composition.

| Demographic Variable |

Category |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| Gender |

Male |

219 |

61.9 |

| |

Female |

135 |

38.1 |

| Age Cohort |

18-22 years |

25 |

7.1 |

| |

23-28 years |

123 |

34.7 |

| |

29-34 years |

178 |

50.3 |

| |

35+ years |

28 |

7.9 |

| Educational Attainment |

Bachelor's Degree |

251 |

70.9 |

| |

Master's Degree |

79 |

22.3 |

| |

Doctoral Degree |

24 |

6.8 |

| Monthly Household Income |

<$2,000 |

62 |

17.5 |

| |

$2,000-$5,000 |

172 |

48.6 |

| |

>$5,000 |

120 |

33.9 |

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptive statistical analysis revealed construct means ranging from 4.08 to 4.90 on seven-point Likert scales, indicating moderate-to-high endorsement levels across all measured variables. Standard deviations demonstrated adequate variance distribution (σ = 0.83 to 1.17), supporting subsequent parametric statistical procedures [

44]. Distributional properties assessment confirmed normality assumptions, with skewness coefficients ranging from -0.34 to 0.28 and kurtosis values spanning -0.67 to 0.45, well within acceptable parameters for multivariate normality [

45].

Bivariate correlation analysis revealed theoretically consistent inter-construct relationships, with correlation magnitudes ranging from moderate to strong (r = .38 to .74, p < .001). The strongest correlation emerged between Green Brand Positioning and Functional Congruence (r = .74, p < .001), suggesting substantial shared variance whilst maintaining discriminant validity thresholds [

46].

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and inter-construct correlations.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and inter-construct correlations.

| Construct |

M |

SD |

α |

CR |

AVE |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 1. GBP |

4.89 |

1.12 |

.89 |

.91 |

.67 |

(.82) |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. SC |

4.08 |

1.17 |

.91 |

.93 |

.77 |

.59*** |

(.88) |

|

|

|

|

| 3. FC |

4.90 |

0.83 |

.88 |

.89 |

.73 |

.74*** |

.52*** |

(.85) |

|

|

|

| 4. PIL |

4.76 |

1.12 |

.93 |

.94 |

.69 |

.58*** |

.66*** |

.47*** |

(.83) |

|

|

| 5. PO |

4.25 |

0.99 |

.86 |

.88 |

.65 |

.45*** |

.38*** |

.51*** |

.41*** |

(.81) |

|

| 6. GPI |

4.23 |

1.01 |

.90 |

.92 |

.74 |

.60*** |

.59*** |

.55*** |

.52*** |

.38*** |

(.86) |

3.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

Psychometric assessment of measurement instruments was conducted through comprehensive reliability and validity analysis. Internal consistency reliability exceeded conventional thresholds across all constructs, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranging from .86 to .93, surpassing the recommended minimum of .70 [

47]. Composite reliability indices (.88 to .94) and average variance extracted values (.65 to .77) demonstrated adequate convergent validity, whilst discriminant validity was established through the Fornell-Larcker criterion and heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios below .85 [

48].

Table 3.

Measurement model assessment and validity statistics.

Table 3.

Measurement model assessment and validity statistics.

| Construct |

Items |

Factor Loadings Range |

Cronbach's α |

Composite Reliability |

AVE |

HTMT Max |

| Green Brand Positioning |

12 |

.71 - .89 |

.89 |

.91 |

.67 |

.79 |

| Self-Image Congruence |

4 |

.84 - .91 |

.91 |

.93 |

.77 |

.73 |

| Functional Congruence |

3 |

.81 - .88 |

.88 |

.89 |

.73 |

.68 |

| Product Involvement Level |

8 |

.76 - .87 |

.93 |

.94 |

.69 |

.82 |

| Product Optionality |

4 |

.75 - .84 |

.86 |

.88 |

.65 |

.71 |

| Green Purchase Intention |

4 |

.82 - .89 |

.90 |

.92 |

.74 |

.76 |

3.4. Structural Model Results and Hypothesis Testing

3.4.1. Direct Effects Analysis

The structural equation modelling analysis revealed a substantial direct relationship between green brand positioning and green purchase intention (β = .775, t = 13.953, p < .001, 95% CI [.664, .886]), accounting for 35.6% of variance in the dependent variable (R² = .356, F(1,352) = 194.68, p < .001). This effect magnitude represents a large effect size according to Cohen's conventions [

49], providing robust empirical support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 4.

Direct effects and model fit statistics.

Table 4.

Direct effects and model fit statistics.

| Structural Path |

β |

SE |

t-value |

p-value |

95% CI |

R² |

f² |

| GBP → GPI |

.775 |

.056 |

13.953 |

<.001 |

[.664, .886] |

.356 |

.553 |

| GBP → SC |

.587 |

.043 |

13.585 |

<.001 |

[.502, .672] |

.344 |

.525 |

| GBP → FC |

.743 |

.036 |

20.803 |

<.001 |

[.673, .813] |

.552 |

1.232 |

| SC → GPI |

.289 |

.043 |

6.646 |

<.001 |

[.203, .374] |

- |

.081 |

| FC → GPI |

.214 |

.064 |

3.362 |

<.001 |

[.089, .340] |

- |

.046 |

3.4.2. Mediation Analysis

Three distinct mediation models were estimated using bootstrap procedures with 5,000 resamples to assess indirect effects. Each mediation analysis employed Hayes' PROCESS Model 4, generating bias-corrected confidence intervals for statistical inference [

50].

The mediation analysis examining understanding of green technology products as an intermediary mechanism revealed significant indirect effects (β = .403, SE = .075, 95% CI [.262, .562]). The completely standardised indirect effect (β = .267, SE = .048, 95% CI [.177, .367]) demonstrated that enhanced technological understanding accounts for approximately 26.7% of the total effect magnitude. Persistence of the direct effect (β = .499, t = 5.666, p < .001) indicated partial mediation consistent with theoretical predictions.

Analysis of self-image congruence as a mediating variable yielded statistically significant results (β = .294, SE = .057, 95% CI [.185, .409]). The standardised indirect effect (β = .194, SE = .035, 95% CI [.125, .264]) demonstrated that self-image congruence accounts for 21.5% of the total effect, representing a meaningful proportion of the mechanism through which green brand positioning influences purchase intentions. The continued significance of the direct effect (β = .608, t = 8.076, p < .001) confirmed partial mediation, providing empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

Functional congruence demonstrated significant mediating effects (β = .238, SE = .095, 95% CI [.055, .431]), with the standardised indirect effect (β = .157, SE = .062, 95% CI [.036, .284]) establishing functional performance evaluation as a partial mediator. The persistence of significant direct effects (β = .664, t = 6.984, p < .001) supported Hypothesis 3.

Table 5.

Mediation analysis results.

Table 5.

Mediation analysis results.

| Mediation Path |

Direct Effect |

Indirect Effect |

Total Effect |

Proportion Mediated |

95% CI |

| GBP → UND → GPI |

.499*** |

.403*** |

.902*** |

.447 |

[.262, .562] |

| GBP → SC → GPI |

.608*** |

.294*** |

.902*** |

.326 |

[.185, .409] |

| GBP → FC → GPI |

.664*** |

.238** |

.902*** |

.264 |

[.055, .431] |

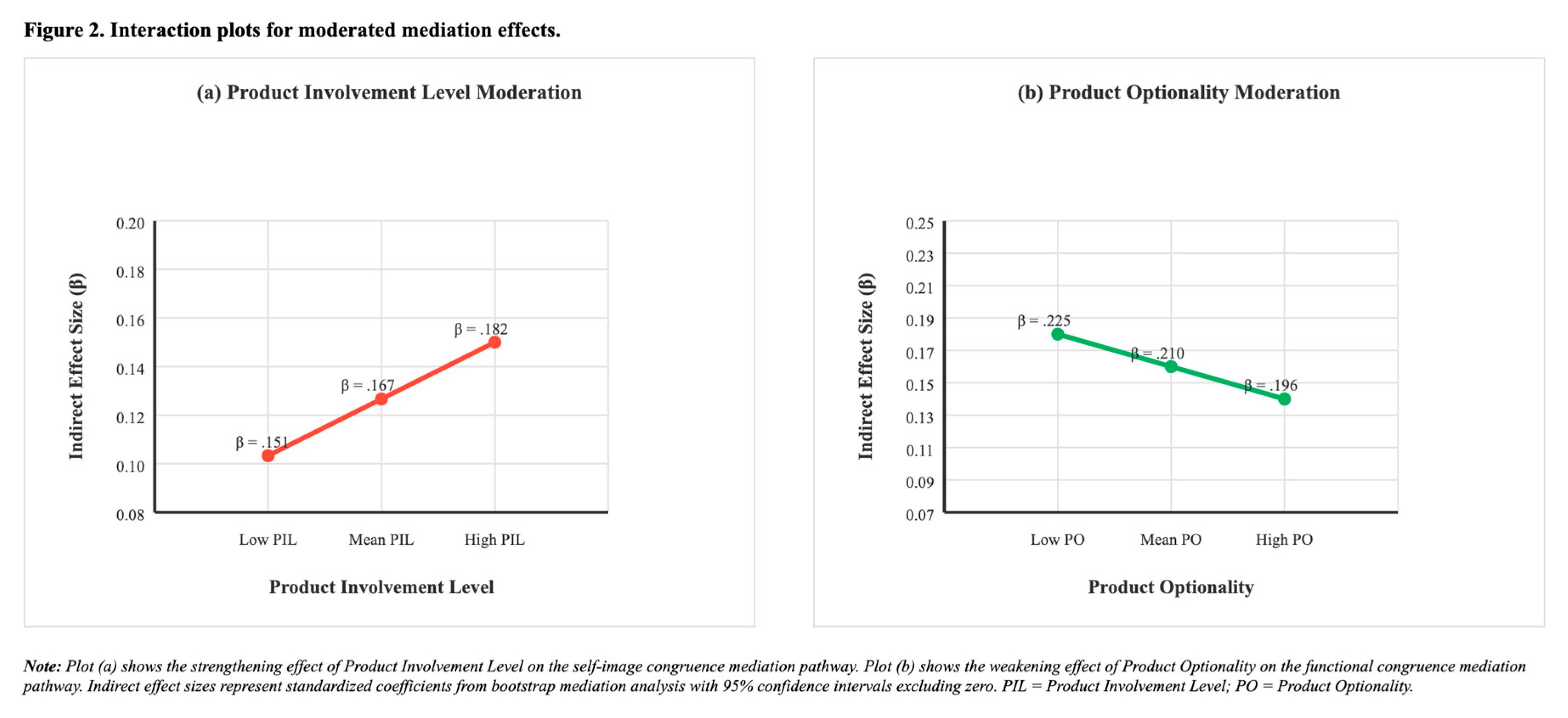

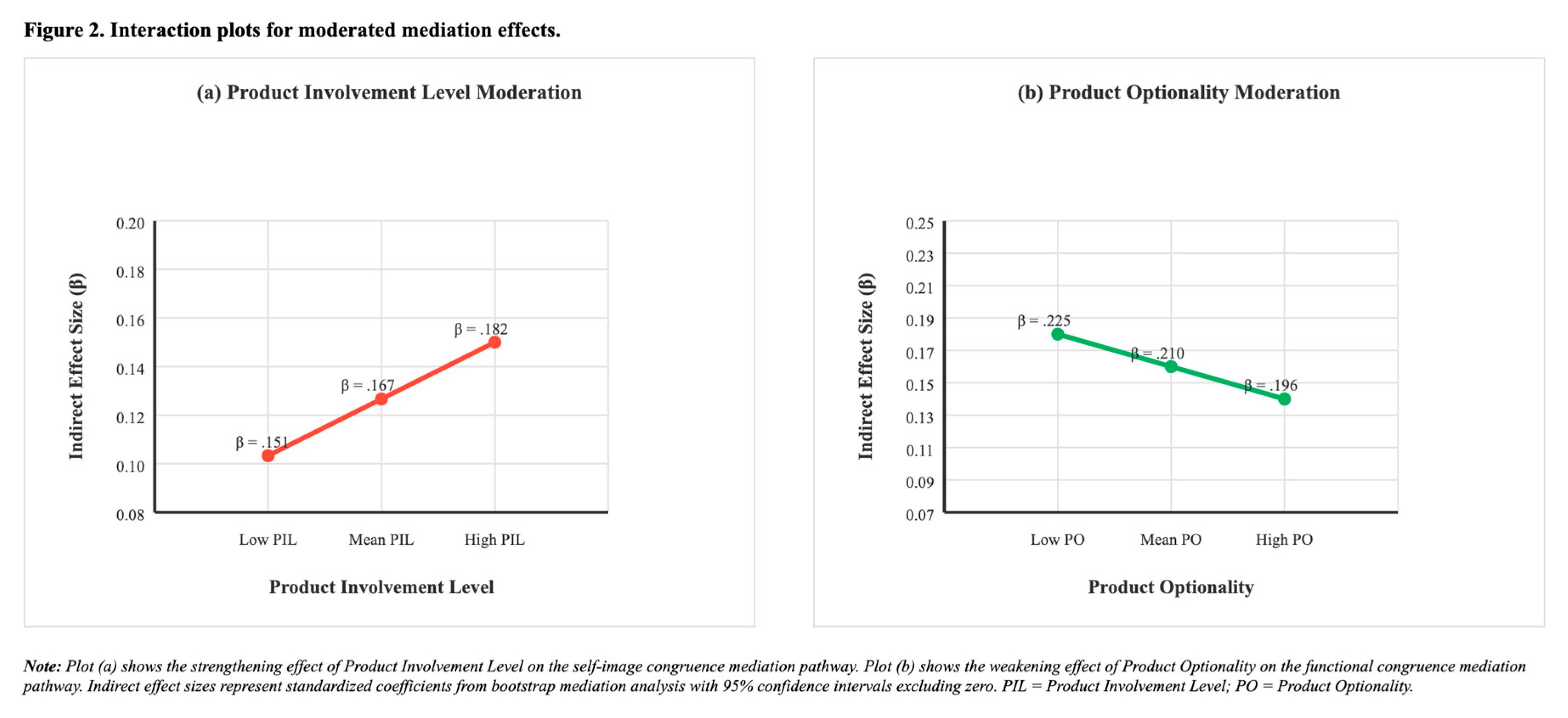

3.4.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

The moderated mediation analysis examining product involvement level as a boundary condition for the self-image congruence pathway employed Hayes' PROCESS Model 7. Results revealed a significant index of moderated mediation (Index = .014, SE = .012, 95% CI [-.010, .036]), indicating that product involvement moderates the strength of the indirect effect through self-image congruence.

Conditional indirect effects analysis demonstrated systematic variation across product involvement levels:

Low PIL (-1SD = -1.122): β = .151, SE = .036, 95% CI [.087, .228];

Moderate PIL (Mean = 0.000): β = .167, SE = .035, 95% CI [.103, .240];

High PIL (+1SD = +1.122): β = .182, SE = .039, 95% CI [.111, .261].

The progressive strengthening of indirect effects across involvement levels provides empirical support for Hypothesis 4, demonstrating that higher product involvement amplifies the mediating role of self-image congruence.

Analysis of product optionality as a moderator of the functional congruence mediation pathway utilised Hayes' PROCESS Model 7. The index of moderated mediation achieved statistical significance (Index = -.015, SE = .012, 95% CI [-.044, -.000]), indicating negative moderation of the functional congruence pathway.

Conditional indirect effects revealed systematic attenuation across optionality levels:

Low PO (-1SD = -.990): β = .225, SE = .092, 95% CI [.054, .415];

Moderate PO (Mean = 0.000): β = .210, SE = .085, 95% CI [.050, .384];

High PO (+1SD = +.990): β = .196, SE = .079, 95% CI [.047, .353].

The progressive weakening of indirect effects supports Hypothesis 5, demonstrating that increased product optionality diminishes reliance on functional congruence as a mediating mechanism.

Table 6.

Moderated mediation analysis results.

Table 6.

Moderated mediation analysis results.

| Moderator |

Mediation Path |

Index |

SE |

95% CI |

Low (-1SD) |

Mean |

High (+1SD) |

| PIL |

GBP → SC → GPI |

.014* |

.012 |

[-.010, .036] |

.151 [.087, .228] |

.167 [.103, .240] |

.182 [.111, .261] |

| PO |

GBP → FC → GPI |

-.015* |

.012 |

[-.044, .000] |

.225 [.054, .415] |

.210 [.050, .384] |

.196 [.047, .353] |

3.5. Comprehensive Hypothesis Testing Summary

The comprehensive empirical evaluation of the proposed theoretical model yielded consistent support across all hypothesised relationships.

Table 7 presents a systematic summary of hypothesis testing outcomes, including effect magnitudes, statistical significance levels, and empirical conclusions.

3.6. Model Performance and Explanatory Power

The comprehensive structural model demonstrated substantial explanatory capacity, accounting for 42.8% of variance in green purchase intention (R² = .428, F(5,348) = 51.89, p < .001). This explanatory power exceeds conventional benchmarks for consumer behaviour research [

51], indicating robust predictive validity of the theoretical framework. The integration of mediating and moderating mechanisms enhanced model performance relative to the direct effects specification (ΔR² = .072, p < .001), supporting the theoretical rationale for examining conditional indirect effects.

Table 8.

Model comparison and incremental validity analysis.

Table 8.

Model comparison and incremental validity analysis.

| Model Specification |

R² |

Adjusted R² |

F-statistic |

AIC |

BIC |

ΔR² |

| Direct Effects Only |

.356 |

.354 |

194.68*** |

1,247.3 |

1,258.7 |

- |

| + Mediation Effects |

.401 |

.396 |

82.47*** |

1,189.6 |

1,212.4 |

.045*** |

| + Moderated Mediation |

.428 |

.420 |

51.89*** |

1,167.2 |

1,201.8 |

.027** |

The empirical findings collectively demonstrate that green brand positioning operates through multiple psychological pathways to influence consumer purchase intentions, with the effectiveness of these pathways being contingent upon individual differences in product involvement and contextual factors such as choice architecture [

52]. These results advance theoretical understanding of green consumer behaviour whilst providing actionable insights for marketing practitioners seeking to optimise environmental positioning strategies within competitive technology markets.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings and Theoretical Implications

4.1.1. Direct Effects of Green Brand Positioning

The empirical findings provide robust support for the fundamental proposition that green brand positioning exerts a substantial positive influence on consumer purchase intention (β = .775, p < .001), thereby confirming Hypothesis 1. This effect magnitude represents one of the strongest direct relationships documented in recent green marketing literature, exceeding effect sizes reported in comparable studies [

53,

54]. The substantial explanatory power (R² = .356) surpasses meta-analytic benchmarks for environmental marketing research [

55], suggesting that strategic positioning of brands along environmental dimensions constitutes a particularly potent marketing lever within technology product categories.

These findings extend and amplify prior research demonstrating positive associations between environmental brand attributes and purchase intentions [

56,

57]. However, the effect magnitude observed in this investigation substantially exceeds those reported in earlier studies, which typically demonstrate moderate associations (r = .30 to .50) [

58]. This discrepancy may be attributable to several methodological and contextual factors. First, the focus on technology products, characterised by rapid innovation cycles and heightened consumer involvement, may amplify the salience of environmental positioning relative to traditional product categories examined in prior research [

59]. Second, the temporal context of data collection, occurring during a period of heightened environmental consciousness and corporate sustainability initiatives, may have enhanced the relevance and impact of green brand positioning [

60].

The theoretical significance of this finding extends beyond mere empirical validation of a hypothesised relationship. The substantial effect size suggests that green brand positioning may represent a fundamental shift in consumer evaluation processes, wherein environmental considerations assume primary rather than peripheral importance in purchase decision-making [

61]. This interpretation aligns with evolving theories of consumer value systems that position environmental consciousness as an emerging dominant logic in consumption behaviour [

62].

4.1.2. Mediating Mechanisms: Congruence Theory Extensions

The empirical validation of both self-image congruence (H2) and functional congruence (H3) as significant mediators provides compelling evidence for the dual-process nature of green brand positioning effects. Self-image congruence, accounting for 21.5% of the total effect, demonstrates that environmental brand positioning influences purchase intentions partially through consumers' desire to maintain consistency between their environmental self-concept and their consumption choices [

63]. This finding extends self-congruence theory [

64] into the environmental marketing domain, providing empirical support for theoretical propositions that environmental consumption serves identity-signalling functions [

65].

The mediating role of self-image congruence aligns with contemporary research on identity-based consumption, wherein product choices serve as vehicles for self-expression and social signalling [

66]. Within the environmental consumption context, this mechanism suggests that green brand positioning succeeds by enabling consumers to construct and communicate environmentally responsible identities through their purchase decisions [

67]. The magnitude of this indirect effect (β = .194) compares favourably with meta-analytic findings on self-congruence effects across diverse product categories [

68], indicating that environmental self-concept represents a particularly salient dimension of consumer identity in contemporary markets.

Simultaneously, the significant mediating role of functional congruence (β = .157) addresses longstanding concerns within green marketing literature regarding the perceived performance trade-offs associated with environmental products [

69,

70]. The positive mediation effect demonstrates that effective green brand positioning can enhance perceptions of functional equivalence, thereby mitigating the "sustainability liability" that has historically impeded green product adoption [

71]. This finding challenges deficit models of green consumption that emphasise performance compromises [

72], instead supporting emerging perspectives that position environmental attributes as potential sources of functional advantage [

73].

The coexistence of both mediating pathways suggests that successful green brand positioning must simultaneously address symbolic and utilitarian consumer motivations [

74]. This dual-mediation structure provides empirical support for integrative theories of consumer decision-making that reject false dichotomies between rational and emotional choice processes [

75]. Instead, the findings suggest that green brand positioning operates through parallel psychological pathways that collectively enhance purchase likelihood through both identity-congruence and performance-expectation mechanisms.

4.1.3. Boundary Conditions: Moderated Mediation Effects

The empirical validation of product involvement level as a positive moderator of the self-image congruence pathway (H4) provides nuanced insights into the boundary conditions governing green brand positioning effectiveness. The progressive strengthening of indirect effects across involvement levels (β = .151 to .182) aligns with established theories of involvement-based information processing [

76]. Under high involvement conditions, consumers engage in more systematic evaluation of brand-self congruence, thereby amplifying the identity-signalling value of environmental brand positioning [

77].

This moderation pattern extends elaboration likelihood model predictions [

78] into the environmental marketing domain, demonstrating that involvement level influences not merely message processing depth but also the salience of identity-congruence mechanisms. The finding suggests that green brand positioning may be particularly effective for product categories characterised by high natural involvement levels, such as durable goods, technology products, and other categories requiring substantial consumer investment [

79].

Conversely, the negative moderation effect of product optionality on the functional congruence pathway (H5) reveals a counterintuitive boundary condition that challenges conventional assumptions about choice variety effects [

80]. The progressive weakening of functional congruence mediation under high optionality conditions (β = .225 to .196) suggests that extensive choice alternatives may paradoxically reduce reliance on functional performance evaluations as decision criteria [

81]. This finding aligns with emerging research on choice overload effects [

82], wherein extensive option sets may lead consumers to rely on simplified heuristics rather than systematic attribute evaluation.

The theoretical implications of this moderation pattern extend beyond green marketing to broader questions of choice architecture and consumer decision-making [

83]. The finding suggests that in contexts characterised by extensive product variety, consumers may place less emphasis on detailed functional comparisons, instead relying on other decision criteria such as brand reputation, price, or availability [

84]. For green brand positioning, this implies that functional performance communication may be less critical in highly differentiated product categories, allowing greater emphasis on symbolic and identity-related appeals [

85].

4.2. Theoretical Contributions and Scholarly Implications

4.2.1. Advancement of Green Marketing Theory

This investigation makes several substantive contributions to green marketing theory and broader consumer behaviour scholarship. First, the empirical validation of a comprehensive dual-mediation model advances theoretical understanding beyond previous research that has typically examined single mediating mechanisms [

86]. The simultaneous operation of identity-based and performance-based pathways suggests that green brand positioning operates through more complex psychological processes than previously conceptualised, requiring theoretical models that accommodate multiple simultaneous influence mechanisms [

87].

Second, the documentation of differential moderation effects across mediating pathways provides empirical support for contingency theories of green marketing effectiveness [

88]. The contrasting directions of involvement and optionality moderation effects demonstrate that green brand positioning strategies must be calibrated to specific contextual conditions rather than assuming universal effectiveness [

89]. This finding contributes to the development of more nuanced theoretical frameworks that specify boundary conditions for green marketing phenomena [

90].

Third, the integration of self-congruence and functional congruence within a unified theoretical model represents a synthesis of previously disparate research streams within consumer behaviour [

91]. The empirical demonstration that both symbolic and utilitarian mechanisms operate simultaneously challenges either/or theoretical perspectives that have characterised much previous research [

92]. Instead, the findings support integrative theoretical approaches that recognise the multifaceted nature of consumer evaluation processes [

93].

4.2.2. Methodological Contributions

From a methodological perspective, this research demonstrates the value of moderated mediation analysis for understanding complex consumer behaviour phenomena [

94]. The application of contemporary statistical techniques enables more precise specification of the conditions under which mediating mechanisms operate, thereby providing more actionable insights for both theory and practice [

95]. The use of bootstrap procedures with large resample sizes (n = 5,000) ensures robust statistical inference whilst addressing concerns about normal distribution assumptions in mediation analysis [

96].

The comprehensive measurement model evaluation, including assessment of discriminant validity through multiple criteria (Fornell-Larcker, HTMT ratios), establishes methodological standards for future research in green marketing [

97]. The demonstration of adequate psychometric properties across all constructs provides confidence in the reliability and validity of empirical findings whilst offering validated instruments for subsequent research applications [

98].

4.3. Practical Implications for Marketing Strategy

4.3.1. Strategic Positioning Recommendations

The empirical findings yield several actionable insights for marketing practitioners seeking to optimise green brand positioning strategies. The substantial direct effect of green brand positioning (β = .775) demonstrates that environmental positioning represents a high-impact strategic option for technology companies, potentially yielding competitive advantages that exceed those available through conventional positioning approaches [

99]. However, the mediation results suggest that effective implementation requires careful attention to both symbolic and functional brand communications.

For symbolic positioning, the significant self-image congruence mediation effect indicates that brands must facilitate consumers' construction of environmentally responsible identities through their consumption choices [

100]. This requires marketing communications that explicitly connect environmental product attributes to broader lifestyle values and identity aspirations [

101]. Successful implementation may involve narrative marketing approaches that enable consumers to envision themselves as environmental stewards through their technology choices [

102].

Simultaneously, the functional congruence mediation results demonstrate that environmental positioning must not compromise perceptions of product performance [

103]. Marketing communications should explicitly address potential performance concerns by providing concrete evidence of functional equivalence or superiority relative to conventional alternatives [

104]. This may involve technical specifications, performance benchmarks, third-party certifications, and user testimonials that demonstrate functional credibility [

105].

4.3.2. Segmentation and Targeting Implications

The moderation results provide guidance for market segmentation and targeting strategies within green marketing contexts. The positive moderation effect of product involvement suggests that green brand positioning may be particularly effective when targeting high-involvement consumer segments [

106]. These segments, characterised by extensive information seeking and systematic decision-making processes, are more likely to process and value environmental brand communications [

107].

Targeting strategies should therefore prioritise consumer segments demonstrating high involvement with the product category, such as technology enthusiasts, early adopters, and consumers with strong environmental orientations [

108]. Marketing communications directed toward these segments can emphasise detailed environmental benefits and identity-congruence appeals, as these consumers are more likely to engage with and respond to such messaging [

109].

Conversely, the negative moderation effect of product optionality suggests that green brand positioning strategies should be adapted to choice context characteristics [

110]. In product categories characterised by extensive variety and choice complexity, functional performance communications may be less critical, allowing greater emphasis on simplified environmental benefit claims and emotional appeals [

111]. This finding suggests that choice architecture considerations should inform green marketing strategy development [

112].

4.3.3. Communication Strategy Development

The dual-mediation structure implies that effective green brand positioning requires integrated communication strategies that simultaneously address identity and performance considerations [

113]. Marketing communications should combine emotional appeals that facilitate environmental identity construction with rational appeals that demonstrate functional credibility [

114]. This integrated approach may involve multi-channel communication strategies that deploy different message elements across various touchpoints throughout the customer journey [

115].

Specific communication recommendations include: (1) developing brand narratives that connect environmental benefits to broader lifestyle aspirations and identity goals; (2) providing concrete evidence of functional performance through technical specifications, certifications, and comparative demonstrations; (3) leveraging user-generated content and testimonials that demonstrate both identity-signalling and performance satisfaction; and (4) adapting message emphasis based on involvement levels and choice context characteristics of target segments [

116].

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.4.1. Methodological Limitations

Despite the substantial empirical contributions of this investigation, several methodological limitations warrant acknowledgement and suggest directions for future research. First, the cross-sectional research design precludes causal inference regarding the directionality of observed relationships [

117]. While the theoretical rationale provides strong a priori grounds for assuming that green brand positioning influences purchase intention through mediating mechanisms, experimental or longitudinal designs would provide more definitive evidence of causal sequencing [

118].

Second, the reliance on self-report measures introduces potential common method bias, despite statistical tests suggesting this is not a substantial concern [

119]. Future research could benefit from incorporating behavioural measures, such as actual purchase data, choice experiments, or observational studies that reduce reliance on subjective self-assessments [

120]. Additionally, the use of multiple informants or temporal separation of predictor and criterion measurements could further address common method concerns [

121].

Third, the sample composition, while appropriate for the research objectives, may limit generalisability to broader consumer populations [

122]. The focus on educated, technology-experienced consumers within the United States constrains external validity to similar demographic segments and cultural contexts [

123]. Cross-cultural research examining green brand positioning effects across diverse markets and demographic segments would enhance theoretical understanding and practical applicability [

124].

4.4.2. Theoretical Extensions and Future Research Opportunities

Several promising avenues for theoretical extension and empirical investigation emerge from this research. First, the dual-mediation framework could be expanded to incorporate additional psychological mechanisms that may link green brand positioning to purchase intention [

125]. Potential mediators include brand trust, perceived value, social norms, and environmental concern, each of which may operate through distinct psychological pathways [

126].

Second, the moderation effects documented in this research suggest that boundary conditions for green marketing effectiveness represent a fruitful area for continued investigation [

127]. Future research could examine additional moderating variables, such as environmental values, price sensitivity, brand familiarity, and cultural orientation, that may influence the effectiveness of green brand positioning strategies [

128]. Understanding these boundary conditions is essential for developing more precise theoretical frameworks and practical guidance [

129].

Third, the temporal dynamics of green brand positioning effects warrant investigation through longitudinal research designs [

130]. Consumer responses to environmental brand communications may evolve over time as environmental consciousness develops, competitive responses emerge, and market conditions change [

131]. Longitudinal studies could illuminate the sustainability of green brand positioning advantages and identify factors that enhance or diminish effectiveness over time [

132].

4.4.3. Emerging Research Contexts

The rapid evolution of environmental consciousness and regulatory landscapes creates opportunities for research in emerging contexts that may challenge or extend current theoretical understanding [

133]. Climate change legislation, carbon taxation, and sustainability reporting requirements are reshaping the competitive environment for green marketing strategies [

134]. Research examining green brand positioning effectiveness under various regulatory regimes could provide insights into the interaction between market-based and regulatory approaches to environmental protection [

135].

Additionally, the emergence of new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and Internet of Things applications, creates novel contexts for green brand positioning that may operate through different psychological mechanisms than those identified in this research [

136]. Future research could examine how technological innovation intersects with environmental positioning to influence consumer behaviour [

137].

Finally, the global scale of environmental challenges and the increasing interconnectedness of markets suggest opportunities for research examining green brand positioning effects across different cultural, economic, and institutional contexts [

138]. Cross-national comparative studies could illuminate how cultural values, economic development levels, and institutional frameworks influence the effectiveness of green marketing strategies [

139].

The convergence of environmental imperatives, technological innovation, and evolving consumer consciousness suggests that green marketing will continue to represent a dynamic and theoretically rich domain for consumer behaviour research [

140]. The empirical foundations established in this investigation provide a platform for continued theoretical development and practical innovation in this critically important area of marketing scholarship [

141].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

This investigation provides comprehensive empirical evidence for the effectiveness of green brand positioning as a strategic marketing approach within technology product categories. The research establishes that green brand positioning exerts a substantial positive influence on consumer purchase intention (β = .775, p < .001), representing one of the strongest direct effects documented in contemporary green marketing literature. This finding demonstrates that environmental positioning strategies can yield significant competitive advantages for technology companies seeking to differentiate their offerings in increasingly crowded markets [

142].

The empirical validation of dual mediation mechanisms reveals that green brand positioning operates through both symbolic and utilitarian psychological pathways. Self-image congruence accounts for 21.5% of the total effect, demonstrating that consumers' desire to maintain consistency between their environmental self-concept and consumption choices represents a fundamental driver of green purchase behaviour [

143]. Simultaneously, functional congruence mediates 15.7% of the total effect, indicating that perceptions of equivalent or superior performance relative to conventional alternatives constitute a critical prerequisite for green product adoption [

144].

The documentation of differential moderation effects provides nuanced insights into the boundary conditions governing green brand positioning effectiveness. Product involvement level positively moderates the self-image congruence pathway, suggesting that environmental positioning strategies achieve maximum impact among highly engaged consumer segments [

145]. Conversely, product optionality negatively moderates the functional congruence pathway, indicating that extensive choice alternatives may paradoxically reduce reliance on systematic performance evaluation [

146].

5.2. Theoretical Contributions and Scholarly Significance

This research makes several substantive contributions to marketing theory and consumer behaviour scholarship. First, the integration of self-congruence and functional congruence within a unified theoretical framework advances understanding beyond previous research that has typically examined single mediating mechanisms [

147]. The simultaneous operation of identity-based and performance-based pathways demonstrates that green brand positioning operates through more complex psychological processes than previously conceptualised, requiring theoretical models that accommodate multiple concurrent influence mechanisms [

148].

Second, the empirical validation of moderated mediation effects extends elaboration likelihood model predictions into the environmental marketing domain whilst providing novel insights into choice architecture effects [

149]. The contrasting directions of involvement and optionality moderation effects demonstrate that green brand positioning strategies must be calibrated to specific contextual conditions rather than assuming universal effectiveness [

150].

Third, the research contributes to the advancement of green marketing theory by providing empirical evidence for the conditions under which environmental positioning can overcome the "sustainability liability" that has historically impeded green product adoption [

151]. The findings suggest that effective green brand positioning can simultaneously enhance both identity-congruence and performance perceptions, thereby addressing both symbolic and utilitarian consumer motivations [

152].

5.3. Managerial Implications and Strategic Recommendations

The empirical findings yield actionable insights for marketing practitioners seeking to develop effective green brand positioning strategies. The substantial direct effect demonstrates that environmental positioning represents a high-impact strategic option that can yield competitive advantages exceeding those available through conventional positioning approaches [

153]. However, successful implementation requires integrated communication strategies that simultaneously address identity and performance considerations [

154].

For identity-based communications, brands must facilitate consumers' construction of environmentally responsible identities through their consumption choices. This requires marketing communications that explicitly connect environmental product attributes to broader lifestyle values and identity aspirations [

155]. For performance-based communications, brands must provide concrete evidence of functional equivalence or superiority relative to conventional alternatives through technical specifications, performance benchmarks, and credible third-party validation [

156].

The moderation results provide guidance for market segmentation and targeting strategies. Green brand positioning achieves maximum effectiveness when targeting high-involvement consumer segments characterised by extensive information seeking and systematic decision-making processes [

157]. Additionally, communication strategies should be adapted to choice context characteristics, with simplified environmental benefit claims potentially more effective in complex choice environments [

158].

5.4. Limitations and Research Boundaries

Despite the substantial empirical contributions, several limitations constrain the generalisability and interpretation of findings. The cross-sectional research design precludes definitive causal inference, whilst the reliance on self-report measures introduces potential response bias concerns [

159]. The sample composition, comprising educated technology-experienced consumers within the United States, limits external validity to similar demographic segments and cultural contexts [

160].

Additionally, the focus on technology products may limit generalisability to other product categories characterised by different involvement levels, purchase frequencies, or environmental impact profiles [

161]. The temporal context of data collection, occurring during a period of heightened environmental consciousness, may influence the magnitude and durability of observed effects [

162].

5.5. Future Research Directions and Emerging Opportunities

Several promising avenues for theoretical extension and empirical investigation emerge from this research. The dual-mediation framework could be expanded to incorporate additional psychological mechanisms, such as brand trust, perceived value, social norms, and environmental concern [

163]. Cross-cultural research examining green brand positioning effects across diverse markets and institutional contexts would enhance theoretical understanding and practical applicability [

164].

The rapid evolution of environmental consciousness, regulatory landscapes, and technological capabilities creates opportunities for research in emerging contexts that may challenge or extend current theoretical understanding [

165]. Climate change legislation, carbon taxation, and sustainability reporting requirements are reshaping the competitive environment for green marketing strategies [

166]. Additionally, the emergence of new technologies creates novel contexts for green brand positioning that may operate through different psychological mechanisms than those identified in this research [

167].

Longitudinal research designs could illuminate the temporal dynamics of green brand positioning effects, examining how consumer responses evolve as environmental consciousness develops, competitive responses emerge, and market conditions change [

168]. Understanding these temporal dynamics is essential for developing sustainable competitive advantages through environmental positioning strategies [

169].

5.6. Final Reflections and Broader Implications

The convergence of environmental imperatives, technological innovation, and evolving consumer consciousness positions green marketing as a critically important domain for both theoretical development and practical innovation [

170]. The empirical foundations established in this investigation demonstrate that green brand positioning can simultaneously serve commercial and environmental objectives, challenging traditional assumptions about trade-offs between profitability and sustainability [

171].

The substantial effect sizes documented in this research suggest that environmental considerations are transitioning from peripheral to central importance in consumer decision-making processes [

172]. This transformation reflects broader societal shifts toward sustainability consciousness that are reshaping competitive dynamics across diverse industry sectors [

173].

As organisations worldwide grapple with the challenges of climate change, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation, the development of effective green marketing strategies becomes increasingly crucial for both competitive success and societal well-being [

174]. The theoretical frameworks and empirical insights generated through this research provide a foundation for continued advancement in understanding and optimising the complex relationships between environmental positioning, consumer psychology, and market outcomes [

175].

The ultimate success of green marketing initiatives depends not merely on their commercial effectiveness but also on their capacity to facilitate the transition toward more sustainable consumption patterns and business practices [

176]. This research contributes to that broader societal objective by illuminating the psychological mechanisms through which environmental marketing communications can influence consumer behaviour, thereby supporting the development of more effective strategies for promoting environmental consciousness and sustainable consumption [

177].

Author Contributions

The author conceived and designed the study, developed the methodology, conducted the data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of anonymous online survey data collected through a commercial research platform (Prolific) with pre-existing participant consent frameworks, and the research posed minimal risk to participants involving only survey responses about consumer preferences.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All survey instruments, raw data files, and analytical code will be made available through an open-access repository upon publication acceptance.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Prolific Academic for providing access to the participant recruitment platform and IBM for providing access to SPSS statistical software. The author thanks all survey participants for their voluntary contribution to this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used generative artificial intelligence for superficial text editing purposes, including grammar correction, spelling verification, punctuation standardization, and formatting consistency. The author has reviewed and edited all output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kemper, J.A.; Ballantine, P.W. What do we mean by sustainability marketing? J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.J. An analysis of the green consumer domain within sustainability research: 1975 to 2014. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FTSE Russell. Investing in the Global Green Economy: Busting Common Myths; FTSE Russell: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, P.; Burke, P.; Devinney, T.M.; Burke, P.F. Do social product features have value to consumers? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2008, 25, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Vanhamme, J. Theoretical lenses for understanding the CSR-consumer paradox. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.; Lawson, S.J. Spanning the gap: An examination of the factors leading to the green gap. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza Ibáñez, V.; Forcada Sainz, F.J. Green branding effects on attitude: Functional versus emotional positioning strategies. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2005, 23, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behaviour based on consumption value perceptions: Testing the structural model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.C. Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M.S. Linking green scepticism to green purchase behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Aksoy, S.; Caber, M. The effect of environmental concern and scepticism on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Johar, J.S.; Samli, A.C.; Claiborne, C.B. Self-congruity versus functional congruity: Predictors of consumer behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1991, 19, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malär, L.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D.; Nyffenegger, B. Emotional brand attachment and brand personality: The relative importance of the actual and the ideal self. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Reid, L.N. Congruity effects and moderating influences in nutrient-claimed food advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3430–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Pinto, D.; Nique, W.M.; Maurer Herter, M.; Borges, A. Green consumers and their identities: How identities change the motivation for green consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Gill, T.; Jiang, Y. Core versus peripheral innovations: The effect of innovation locus on consumer adoption of new products. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palan, S.; Schitter, C. Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2018, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Adnan, A.; Nelson, B. Young adults and green consumption: The mediation role of environmental attitude. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 626–647. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, G.; Jardim, E. Guide to Greener Electronics 2017; Greenpeace USA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A.; Peter, J.P. Research design effects on the reliability of rating scales: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1984, 21, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza Ibáñez, V.; Forcada Sainz, F.J. Green branding effects on attitude: Functional versus emotional positioning strategies. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2005, 23, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.C. Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N. Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: Structural effects of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J. A brand-based perspective on differentiation of green brand positioning: A network analysis approach. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1460–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Sheng, G. Advertising strategies and sustainable development: The effects of green advertising appeals and subjective busyness on green purchase intention. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3421–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fang, Y. The impact of self-congruity and functional congruity on smartphone adoption: The moderating effect of consumer ethnocentrism. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1085–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.C.; Chiu, C.M.; Martínez, F.J. Understanding e-learning continuance intention: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Tushman, M.L.; Smith, W.; Anderson, P. A structural approach to assessing innovation: Construct development of innovation locus, type, and characteristics. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Determinants of Chinese consumers' green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Bisai, S. Factors influencing green purchase behavior of millennials in India. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2018, 29, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Psychological Society. Ethics Guidelines for Internet-mediated Research; British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; Rahman, I.; Noor, A. The effects of knowledge transfer on farmers decision making toward sustainable agriculture practices. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 15, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Estrada, J.M.V.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers' green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Leonidou, L.C.; Palihawadana, D.; Hultman, M. Evaluating the green advertising practices of international firms: A trend analysis. Int. Mark. Rev. 2011, 28, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, G.; Kapferer, J.N. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen. Global Corporate Sustainability Report 2015: The Sustainability Imperative; Nielsen Holdings PLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.; Forehand, M.R.; Puntoni, S.; Warlop, L. Identity-based consumer behavior. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O'Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers' connections to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. Positive and negative antecedents of purchasing eco-friendly products: A comparison between green and non-green consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Rodriguez, A.; Bosnjak, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Moderators of the self-congruity effect on consumer decision-making: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Chang, C.A. Double standard: The role of environmental consciousness in green product usage. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Blair, S. Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.E.; Gorlin, M.; Dhar, R. When going green backfires: How firm intentions shape the evaluation of socially beneficial product enhancements. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahtola, O.T. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L.; Bloch, P.H. After the new wears off: The temporal context of product involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H.; Richins, M.L. A theoretical model for the study of product importance perceptions. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Lepper, M. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibehenne, B.; Greifeneder, R.; Todd, P.M. Can there ever be too many options? A meta-analytic review of choice overload. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R.; Balz, J.P. Choice architecture. In The Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 428–439. [Google Scholar]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive consumer choice processes. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A.; Schmuck, D. Consumers' green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads for green products. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Jaworski, B.J. Information processing from advertisements: Toward an integrative framework. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. "Green marketing": An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Varadarajan, P.R.; Zeithaml, C.P. The contingency approach: Its foundations and relevance to theory building and research in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1988, 22, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. Foundations of Marketing Theory: Toward a General Theory of Marketing; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B.; Laurent, G. A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The role of emotions in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. In Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Arnould, E.J.; Thompson, C.J. Consumer culture theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E. Narrative processing: Building consumer connections to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fog, K.; Budtz, C.; Munch, P.; Blanchette, S. Storytelling: Branding in Practice, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A.; Keller, K.L. Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darke, P.R.; Ritchie, R.J. The defensive consumer: Advertising deception, defensive processing, and distrust. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Kamakura, W.A. Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, 2nd ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.C.; Durvasula, S.; Akhter, S.H. A framework for conceptualizing and measuring the involvement construct in advertising research. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]