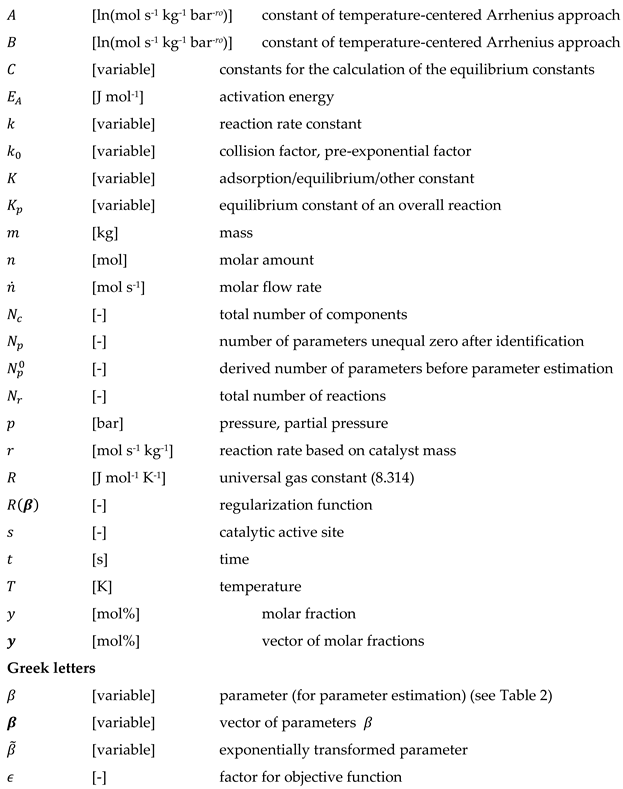

1. Introduction

Methanol is an important chemical building block, a potential hydrogen carrier and a fuel [

1]. Its industrial production started in the beginning of the 20

th century with different metal oxide catalysts. In the 1960’s more active copper containing catalysts could be established in the industry due to improved removal of sulfur containing compounds from the feed gases and reduced poisoning. This and the beneficial inclusion of CO

2 in the feed stream allowed for running the methanol synthesis process at lower pressures (from 200 bar to 50-100 bar) and temperatures (from 673 K to 503 K) [

2]. The typical catalyst consisting of Cu/ZnO/Al

2O

3 (CZA) established commercially in the mid of the 1960’s [

2,

3]. The reaction mechanism on such types of catalyst was investigated over decades. Questions regarding the carbon source (CO or CO

2), the number and character of active sites, the reaction mechanism and rate-determining steps were studied intensively [

2].

Recent work of the Christensen group and the Muhler group reveals that a methanol-assisted reaction pathway is of large importance [

3,

4]. Furthermore, Thrane et al. postulate that the major number of turnovers for the applied conditions in the industrial process is through this autocatalytic pathway [

4]. The Brilman group emphasizes in recent work the need to take the influence of methanol and water on the reaction mechanism into account [

5]. Our work is a contribution to that. To the best of our knowledge no formulation of a quantitative kinetic model taking this pathway into account is available in the literature until now.

The aim of this contribution is to derive a mechanistically based kinetic model for the methanol synthesis including a methanol-assisted autocatalytic reaction route exploiting recent findings in the literature and following a well-established derivation methodology [

6]. This model is parameterized utilizing a readily available data set [

7,

8] and compared with reduced model variants and several literature models.

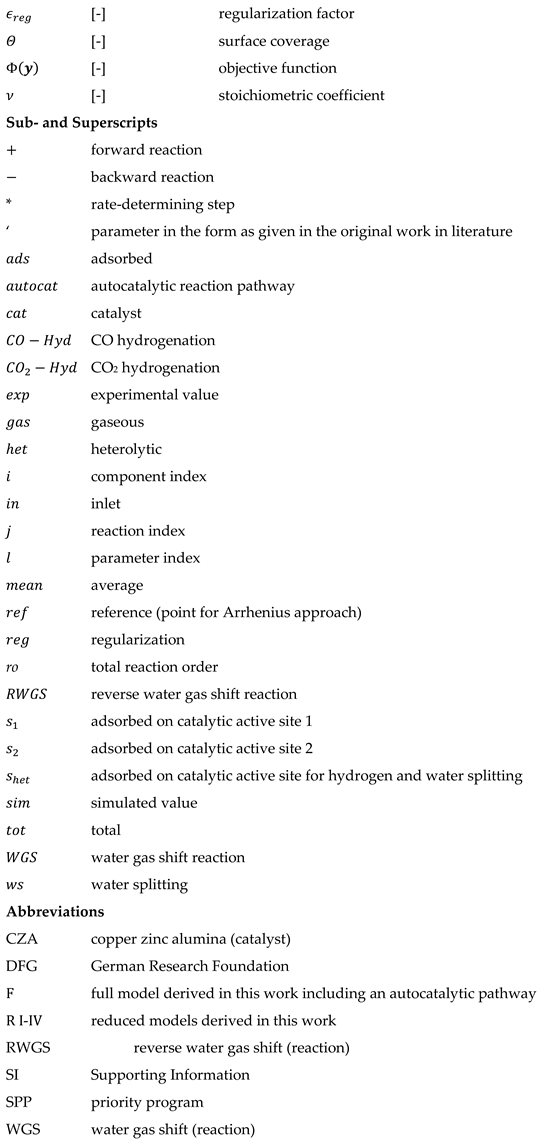

Conventionally, it is assumed that the CZA catalyst promotes the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide (CO), the hydrogenation of carbon dioxide (CO

2) and the (reverse) water gas shift reaction (WGS) as assumed by Graaf et al. [

9]. For kinetic modeling different simpler options based on neglecting one of the reactions can be found [

10,

11]. Depending on the feed composition and the reaction temperature the relevance of the three mentioned reactions differs [

12]. Feeds consisting despite minor impurities only of CO/H

2 as well as CO

2/H

2 can yield significant amounts of methanol [

7]. It is widely accepted that mixed feeds containing CO/CO

2/H

2 generate the most methanol and that the hydrogenation of CO

2 is at least dominant under industrial conditions for CZA catalysts [

13,

14,

15]. The presence of CO is beneficial because it removes inhibiting water via WGS reaction [

14,

15]. Some authors postulate that the direct hydrogenation of CO is not occurring at all on commercial CZA catalysts under relevant temperatures because no methanol formation was observed applying purified CO/H

2 feeds free of CO

2 and H

2O [

16,

17]. The authors of this contribution are not convinced that this claim is generally valid for all commercial CZA catalysts over the entire temperature range of industrial methanol synthesis. Several other authors consider the direct CO hydrogenation as relevant reaction pathway for at least specific conditions like low CO

2 contents in the feed [

14,

18] or at higher reaction temperatures [

12]. Thus, in this work, a direct CO hydrogenation is included in the analysis together with model versions neglecting this reaction. Additionally, we assume inspired by Schwiderowski et al. as a fourth reaction the methanol-assisted hydrogenation of CO

2 [

3]. The complete reaction network evaluated is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Kinetic Description and Model Derivation

Based on recent literature, elementary reaction steps and rate-determining steps are assumed. Rate approaches are derived for all four main reactions which are considered in the model. The reactor model which is used later on for parameter estimation is also introduced.

For simplicity, ideal gas conditions are assumed and partial pressures are used for the model formulation. The majority of the re-analyzed experiments (136 of 140) was conducted at 30 – 60 bar. The model accuracy at higher pressures could be still increased using fugacities. For the model derivation all reactive components are assumed to adsorb. An adsorption of inert nitrogen is neglected. Adsorption is regarded as an elementary reaction step and conventionally formulated as a forward reaction while the desorption of a component is formulated as backward reaction.

The focus of this contribution is not a consideration of the chemical nature of the active sites. This aspect is not required. Only the assignment which reaction and adsorption phenomena occur on which site is important for the derivation of the equations. Following de Oliveira Campos et al. and Seidel, three active catalytic sites are considered for adsorption and reaction [

18,

19,

20]. Site 1 (

) is metallic copper active for hydrogenation of CO and WGS. Site 2 (

) is a unspecified copper zinc species offering a contact area active for hydrogenation of CO

2 with and without methanol-assistance as well as for WGS. An additional site 3 (

) is active for adsorption and splitting of hydrogen and water.

2.1. Elementary Reaction Steps

For every reaction pathway a table summarizes the assumed elementary reaction steps, an ID for each step in the pathway, an equation for every step as well as the equation number (separate numbering with S) which regards the steps of all reaction pathways (

Table 1,

Table S1-S4 in the Supporting Information SI 1). The step which is treated as rate-determining is bold printed and marked with an asterisk*.

CO hydrogenation: Despite the low importance of the direct hydrogenation of CO for mixed CO/CO

2/H

2 feeds under industrial conditions, it is considered for some variants of the model and neglected for others which will be compared later. It is assumed to take place only on one site, which is the metallic copper (site 1) [

18,

19,

20]. A stepwise hydrogenation of CO is considered (see

Table S1) [

9,

14,

18,

19,

21]. A difference to most other kinetic models is the assumption that also methanol adsorbs as assumed by Vollbrecht [

7,

8,

22]. The rate-determining step (step A4 in

Table S1) was adopted from de Oliveira Campos et al. [

18,

19,

23].

CO2 hydrogenation without methanol-assistance: From the results of a reaction flow analysis de Oliveira Campos et al. drew the conclusion that the hydrogenation of CO

2 occurs mainly on site 2 (involving Zn) [

18]. Thus, in our contribution it is assumed that both the hydrogenation of CO

2 with and without methanol-assistance occur only on site 2. The hydrogenation of the intermediate formate HCOO* is assumed to be rate-determining (step B4 in

Table S2) [

3,

14,

21]. The elementary reaction steps of the CO

2 hydrogenation are in line with Studt et al. and de Oliveira Campos et al. supplemented by the methanol adsorption (see

Table S2) [

14,

18,

19,

20].

Water gas shift reaction: For the WGS reaction a carboxyl mechanism is considered occurring on both active sites 1 and 2 via the same elementary steps [

18,

19,

24]. The reaction of a carboxyl species COOH* with a hydroxy species OH* is considered to be rate-determining (step C5 / D5 in

Table S3 / S4). De Oliveira Campos et al. formulated the reaction as reverse WGS and considered this elementary step as rate-determining [

18,

19,

23]. Due to the assumption of a rate-determining step all other reactions are at quasi-equilibrium. Adapting this simplification, the same step is rate-determining in both directions. Thus, this step (C5 / D5) was chosen as rate-determining one for the WGS reaction on both active sites in the following. In contrast, Studt et al. postulate the water-splitting into OH* and H* to be rate-determining for the WGS (step C3 / D3 in

Table S3 / S4) [

24]. The elementary reaction steps of the WGS reaction were adopted from Studt et al. and de Oliveira Campos et al. (see

Table S3 and

Table S4) [

18,

19,

24].

Autocatalytic CO2 hydrogenation with methanol-assistance: Finally, the assumption of the elementary reaction steps of the methanol-assisted hydrogenation of CO

2 is based on the catalytic cycle postulated by Schwiderowski et al. [

3]. The formation of the intermediate methyl formate ester HCOOCH

3* (step E6 in

Table 1) is assumed to be rate-determining because it is the elementary step converting formate HCOO* which is the educt of the rate-determining step in the CO

2 hydrogenation without methanol-assistance. The reaction mechanism is summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. Reaction Rates

For every reaction the concept of a rate-determining step is applied for reasonable simplification. All other elementary steps are then assumed to be at quasi-equilibrium. Thus, the overall rate can be obtained by substitution of the unknown variables in the overall rate equation of the rate-determining step. This is shown exemplary for the new pathway of the autocatalytic hydrogenation of CO2 in this chapter. The derivations are summarized for all reactions in SI 2.

Starting from the brutto rate equation of the rate-determining step E6 (Equation (S24)) all adsorbed surface species

are replaced with the equations for the steps assumed to be at quasi-equilibrium (E1-5,E7-10) from

Table 1. The overall rate of the pathway equals the rate of the rate-determining step.

This inserting procedure is shown in more detail in the SI 2 and leads to Equation (2).

The backward rate coefficient

of the rate-determining step can be substituted with the help of the equilibrium constant of the step (Equation (3)).

After some rearrangements one obtains Equation (4).

Due to the mass action law, the equilibrium constant of the hydrogenation of CO

2 must be equal with and without methanol-assistance (Equation (5)).

Lumping constants together leads to the final rate equation (Equation (6)).

The rate equations of the other reactions (Equations (7-9)) were derived in a similar way using the assumptions summarized in chapter 2.1 (SI 2).

Studt et al. postulated that the rate of the WGS is similar on both active sites [

24]. Thus, for the sake of simplicity, we assumed that the rate constants of the WGS are equal for both active sites and can be represented by one rate constant

in this contribution. The equilibrium constants were calculated with empirical correlations taken from Graaf & Winkelman [

25] and summarized in SI 4. The temperature dependency of the reaction rates is handled applying a temperature-centered Arrhenius approach (Equation 10) [

26]. Every reaction rate constant consists of two parameters resulting in eight parameters for all reaction rate constants (

-

).

was used.

2.3. Surface Coverages

The reaction rates (Equations (6-9)) depend on the reactant partial pressures and the surface coverages of the free active sites. The latter can be calculated with the help of the balance equations of the active sites containing all adsorbing species and free sites (Equations (11-13)).

The surface coverages of all adsorbing species were substituted with the equations of the quasi-equilibrated elementary steps from

Table 1 and

Table S1-S4. The full derivation is shown in SI 3. After inserting, rearrangement and lumping constants together one obtains Equations (14-16).

In addition to the full model, reduced models were tested. One or two of the four reaction rates (Equations (6-9)) and the corresponding surface coverages of adsorbed species in the balances of the active sites (Equations (11-13)), forcing parameters

to be zero a priori, were neglected in these cases. Furthermore, literature models were refitted to the data set used in this study for comparison [

10,

27,

28]. The equations for these models can be found in the SI 6.

2.4. Reactor Model

The already published experimental data set used in this work was generated performing experiments with an isothermally and isobarically operated micro Berty reactor ensuring gradient-free conditions allowing an easy evaluation of kinetic data [

7]. The component balance of a perfectly mixed continuously stirred tank reactor (CSTR) is given in Equation (17). The total molar inlet flow rate

(respective the total volumetric flow rate) differs from the total outlet flow rate

due to the reduction in mole number through methanol synthesis.

According to Keßler & Kienle,

can be substituted with the help of the total material balance (summation over all species) leading to the following steady state component balance for each species [

29]. Ideal gas behavior was assumed. The mass of catalyst was 3.95 g.

This results in a system of six algebraic equations that can be summarized as Equation (19).

is the vector of mole fractions and

is the vector of parameters that have to be considered for the corresponding kinetic model.

3. Parameter Estimation Methodology

An experimental data set produced by Vollbrecht was used for the parameter estimation. A description of the experimental setup and the methods applied can be found in his doctoral thesis [

7]. The data set itself was also published by Seidel et al. [

8]. It consists of 140 isothermal, isobaric steady state experiments conducted in a kinetic micro Berty reactor filled with 3.95 g of a commercial CZA catalyst exploiting feeds with only CO, only CO

2 or both as carbon source yielding industrial relevant amounts of methanol (230-260 °C, 30-70 bar).

To identify the parameters of the kinetic model the following least squares optimization problem was implemented and solved in the programming language Julia [

30]:

The objective function

is defined in Equation (23) as quadratic normalized deviation of the mole fractions of the carbon species between the simulation and the experimental data.

The factor

ensures a reasonable residual even for experimental values of zero or close to zero. The simulated values are obtained in each step by solving the resulting system of algebraic equations by a Newton-Raphson method implemented in the package NonlinearSolve.jl (Equation (19)) [

31]. We assume that the algebraic equations have always a unique solution [

32]. Accordingly, the experimental data points were used as initial values for the mole fractions, resulting in a well-initialized state close to the actual solution. Furthermore, the adsorption constants and the parameters corresponding to the activation energies (

) must always be greater than zero. Therefore, these parameters were exponentially transformed to avoid negative values during the optimization (Equation (21)).

denotes the total number of derived parameters.

The function

is a regularization term and is introduced to obtain physical reasonable parameters and to increase their identifiability. For this purpose, the experiments were divided into subsets to estimate the parameters for the individual reactions separately in a first step and use these values later on as initial values and for a regularization of the parameters corresponding to the activation energies. First, all experiments without CO

2 in the feed were used to fit the direct CO hydrogenation. All other reactions were neglected in this case. Secondly, the data without CO in the inlet was utilized to estimate the initial parameters for the CO

2 hydrogenation without methanol-assistance and the WGS reaction while the rates of CO hydrogenation and autocatalytic pathway were set to zero. The autocatalytic hydrogenation of CO

2 with methanol-assistance was neglected in this step because the carbon-based yield of methanol is small (< 3%) compared to CO/CO

2 mixed feeds. After that, only the cases with both CO and CO

2 in the feed were considered for the identification of the initial parameters of the autocatalytic hydrogenation of CO

2 with methanol-assistance while the CO hydrogenation was neglected and the other reactions were regularized in this case. With this, reference values for all four activation energy related parameters were obtained which were used for their regularization in the final fit of all parameters with all experiments. In addition to that, we also add a term to minimize the remaining constants and to reduce the number of parameters resulting in the regularization function

(Equation (23)).

How strong the regularization influences the objective function in Equation (22) and thus the parameter estimation depends on the regularization factor

in Equation (23). In the following we used

. Details on this and the used values for

are summarized in SI 5. The optimization problem was solved with the Optimization.jl package [

33] by using direct solvers of Optim.jl. The minimum was obtained by repeatedly applying a particle swarm optimization (1000 iterations) to escape from local optima, and a Nelder Mead algorithm to finally converge to a minimum.

Discussion of Results

a) Parameter values

In the full model

, quantifying the rates of all four considered reactions, the methanol-assisted pathway is dominant for CO

2/H

2 and CO/CO

2/H

2 feeds. The simulated amount of methanol formed via the autocatalytic hydrogenation of CO

2 ranges from 83 to 99% of the total amount of methanol formed under the conditions evaluated. This is in accordance with the postulation of Thrane et al. that this pathway is of major importance [

4]. The direct hydrogenation of CO is negligible in the full model

for CO

2 containing feeds for the evaluated operating conditions. It is therefore unlikely that the consideration of this reaction strongly influences the parameter values identified for the other reactions. This is evident as the respective parameter values of the full model

and the reduced model

without CO hydrogenation are almost identical (see

Table 2). Vice versa, for the CO/H

2 feeds without measurable CO

2 or water in the reactor inlet, the direct CO hydrogenation reaction allows the description of methanol production in this case. Three further reduced models were tested neglecting (i) CO

2 hydrogenation without methanol-assistance (

), (ii) the autocatalytic CO

2 hydrogenation (

) or (iii) the autocatalytic pathway and direct CO hydrogenation (

). The parameters of the autocatalytic pathway are always similar when this pathway is considered (

,

,

) supporting the fact that it is dominating. The less important the other methanol producing reactions are the less they affect the estimates of the parameters of the autocatalytic CO

2 hydrogenation. Also the parameters of the WGS are similar in these cases (

,

,

) whether assuming CO hydrogenation, CO

2 hydrogenation without methanol-assistance or both to take place. When model

is further reduced to model

assuming that no direct hydrogenation of CO takes place the parameters of the WGS reaction change distinctly. Without the otherwise dominant autocatalytic pathway, the contribution of the CO hydrogenation is increased causing its neglect now to be more significant.

If the parameters of the re-parameterized Arrhenius equation (Equation (10)) are calculated back into reaction-specific activation energies, the values range from 57.9 kJ/mol to 210 kJ/mol for the considered models. The upper bound is very high occurring only for the direct CO hydrogenation when it is negligible causing the parameter to be not sensitive in this case (, ) and for the CO2 hydrogenation without methanol-assistance for the Vanden Bussche model. The latter observation is interesting because the refitted Nestler model assuming the same reactions with different equations was identified with much lower activation energies (respective , ). This shows how strong the parameter values are bond to the model equations and thus the mechanistic assumptions questioning the meaningfulness of comparisons with reported parameters in literature with different model assumptions. Despite the insignificant direct CO hydrogenation the highest activation energy for the models derived in this work was identified with 137 kJ/mol for the hydrogenation of CO2 without methanol-assistance in the full model being in a reasonable order of magnitude. The estimated activation energy of the autocatalytic reaction pathway is 115 kJ/mol for the full model .

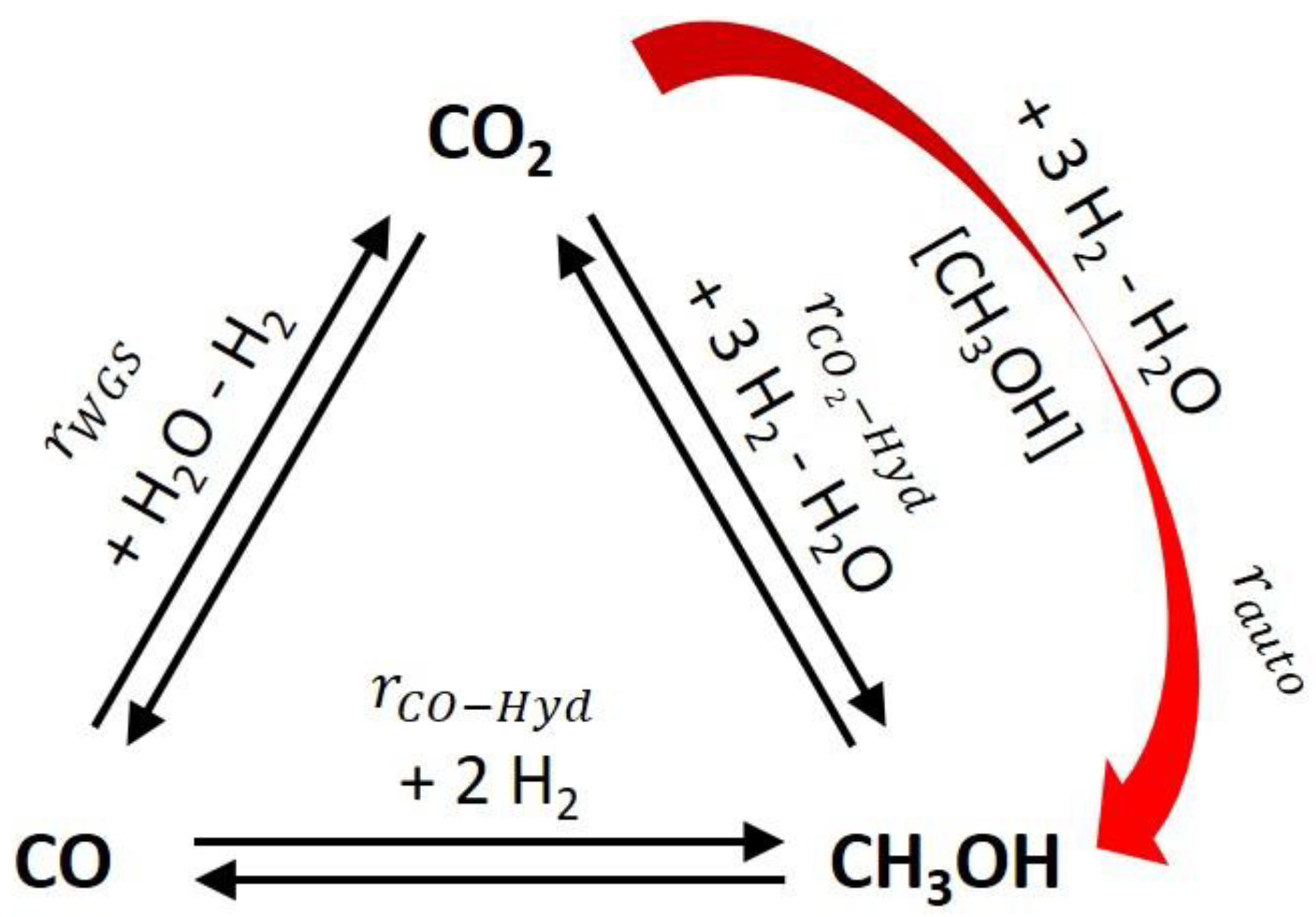

b) Residual and parity plots

All models fit the data rather well. Interestingly, the residual

is always smaller when the autocatalytic hydrogenation of CO

2 is considered (

,

,

), indicating that an autocatalytic behavior should be taken into account. It is also smaller compared to the refitted literature models of Vanden Bussche et al., Nestler et al., Seidel et al. and van Schagen et al. [

5,

10,

27,

28]. It needs to be mentioned that the models of Vanden Bussche et al., Nestler et al. and van Schagen et al. have at least one parameter less. Even though the full model

has four parameters more than the reduced model

, the residual

is almost the same. Since all models fit the reactor outlets for CO

2 containing feeds well (see

Figure 2) a rigorous final model discrimination may not be appropriate with the data basis analyzed.

Nevertheless, for the description of CO

2 containing feeds the reduced model

is recommended having a very good performance in terms of the residual

including the capability to account for the autocatalytic behavior of methanol synthesis, while the number of 10 parameters is not far from established literature models. Additionally, model

does not include a direct CO hydrogenation which is found to be at least insignificant for the industrial process [

5,

13,

14,

15]. The equations of the full model

and the reduced model

are summarized in compact manner in the

Appendix A usable with the parameters in

Table 2.

It is known that the morphology of the catalyst and thus the number of active sites changes under varying process conditions and strongly depends on the reduction potential of the reactants [

21,

34,

35]. Such dynamic changes of the active catalytic sites can be taken into account according to Seidel et al. to improve predictions for dynamic operation regimes [

8,

22,

28]. This extension is not the scope of this article.

(14 parameters), reduced model (10 parameters) and literature models for comparison utilizing CO2 containing feeds only.

5. Conclusions

A mechanistically based kinetic model for the heterogeneously catalyzed methanol synthesis on Cu/ZnO/Al

2O

3 catalysts was derived and parameterized in this work. A so far in available literature models not quantitatively included methanol-assisted autocatalytic reaction pathway was added to conventionally considered reaction pathways. The derived full model contains 14 parameters. Several reduced models can be obtained as special cases and were also evaluated by neglecting one or two of the methanol producing reactions. A reduced model with ten parameters (

), in which the direct CO hydrogenation is not taken into account, performs equally well as the full model

for CO

2 containing feeds. It was shown that the reduced model

is also competitive to literature models. The extension by an autocatalytic reaction pathway leads inherently to additional parameters. All models that incorporate this reaction pathway, i.e. the full model

and the reduced models

and

, provided a significantly lower residual compared to all other models which exclude this pathway (see Equation (22) and

Table 2). This result strongly supports that the consideration of an autocatalytic reaction pathway in kinetic modeling of heterogeneously catalyzed methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al

2O

3 catalysts appears to be very reasonable. Nevertheless, all investigated models fit the steady state data set exploited rather well. Thus, the analysis of a larger data base as well as results of dynamic experiments observing transient changes of the catalyst are necessary to validate this finding.