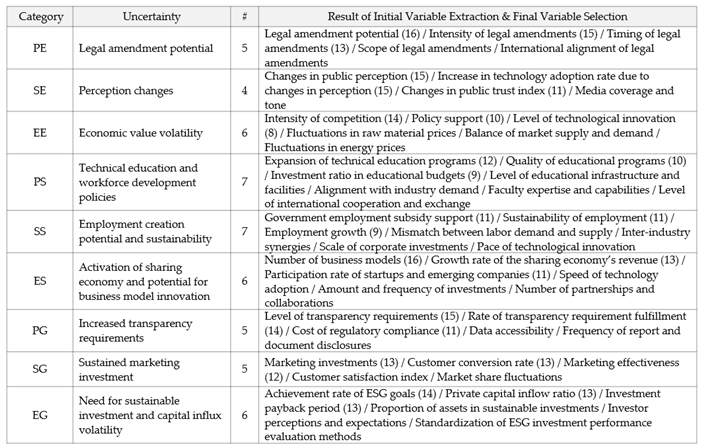

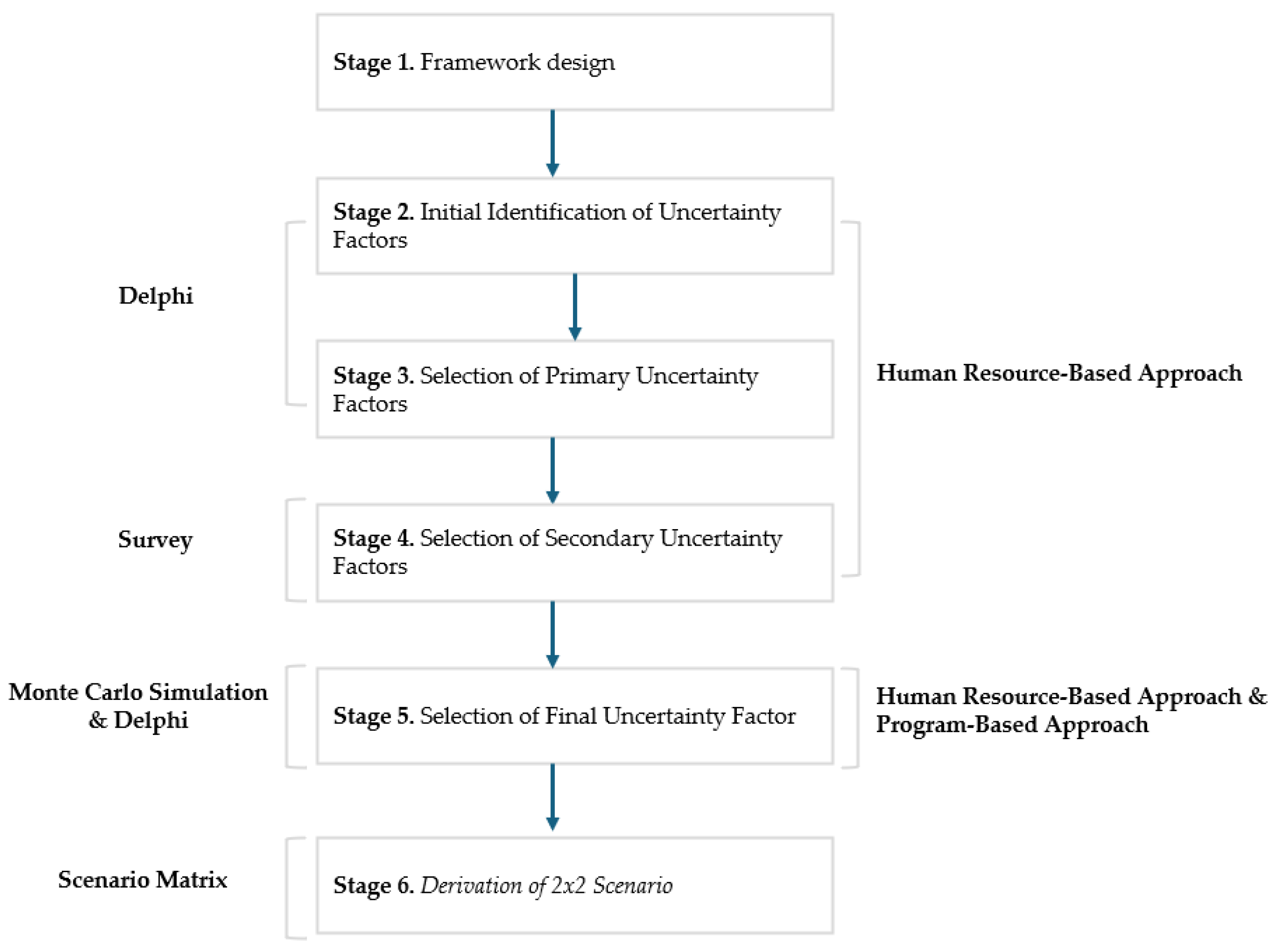

This study was conducted in stages following the research procedure illustrated in

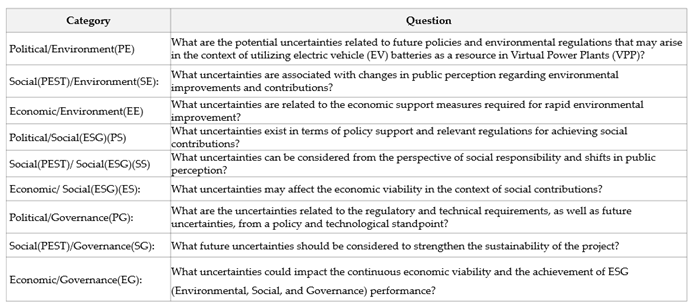

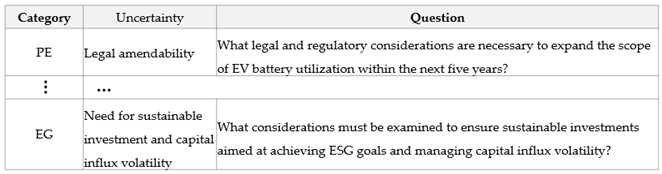

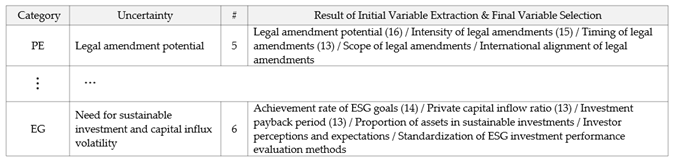

Figure 1. In the Framework Design phase, to comprehensively analyze the external environment influencing the integration of EV batteries into VPPs, a political, economic, social, and technological (PEST) analysis framework [

29] was combined with ESG factors, resulting in a PEST-ESG analytical approach [

30]. Subsequently, the range of the identified uncertainty factors was progressively narrowed down through three stages: initial selection, secondary refinement, and tertiary refinement, ultimately revealing three key uncertainties (two primary and one secondary) to construct a 2×2 scenario matrix. The purpose of this iterative three-step process was to enhance accuracy and reliability through repeated feedback, ensure consistency through expert consultations, and achieve a comprehensive evaluation by incorporating diverse perspectives [

31]. To systematically derive data on uncertainty factors, this study employed a combination of semi-structured interviews and the Delphi method [

32]. The initial interviews involved experts from the EV battery and VPP sectors, including legislative bodies, operational agencies, and industry practitioners, to gain in-depth insights and foundational data that facilitated the initial identification of uncertainty factors. Following this, a process of opinion consolidation and additional consensus-building was undertaken to select the primary uncertainty factors [

33,

34,

35,

36].

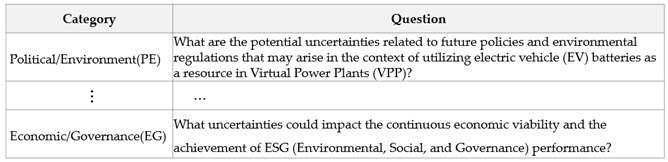

To derive generalizable results from the initially identified uncertainty factors, a survey utilizing a three-point scale (low, medium, high) was conducted [

36,

37,

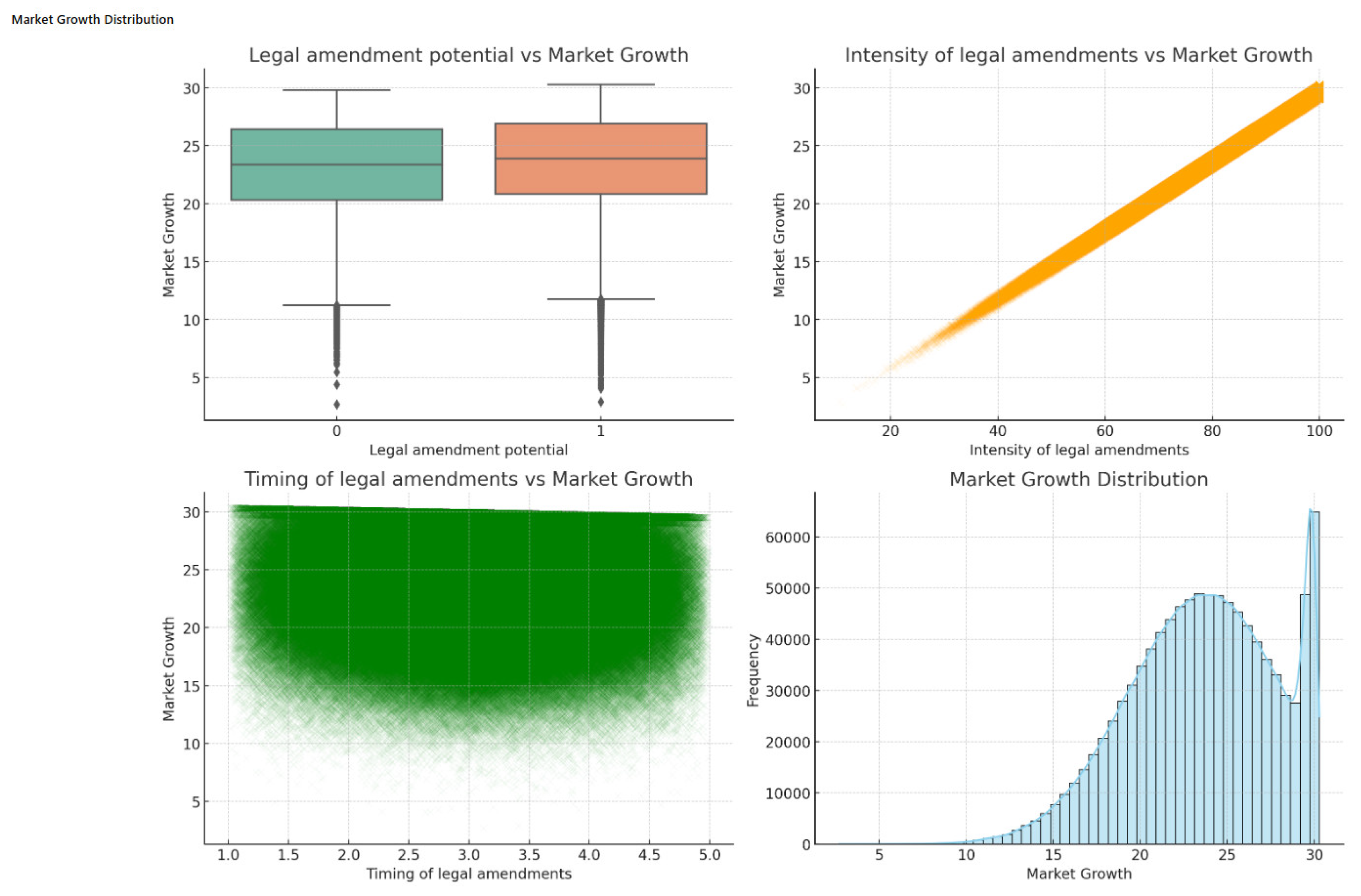

38]. The survey was extended to 50 relevant experts from the policy, technology, and market sectors, and incorporated the 17 experts who participated in the initial interviews to capture diverse perspectives and practical insights. To ensure that the respondents could answer without prior knowledge, definitions and background information regarding the uncertainty factors were provided. The survey responses were quantified to assess the relative ranking of each uncertainty factor, which informed the selection of key factors for the scenario design. The selected secondary uncertainty factors were subjected to probabilistic analysis using Monte Carlo simulations to complement the quantitative analysis of the findings. Following the research procedure, probability distributions (e.g., triangular, normal) were assigned to each uncertainty factor, and Python was used to perform 1,000,000 iterative simulations per factor to estimate the distribution of future outcomes [

39]. Notably, “market growth rate” was designated as the indicator (dependent variable) representing the degree of promotion of EV battery VPP resource utilization, and the impact of each uncertainty factor on this growth rate was assessed.

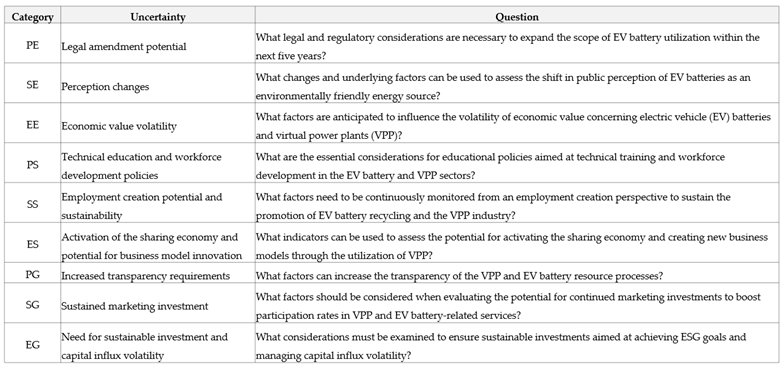

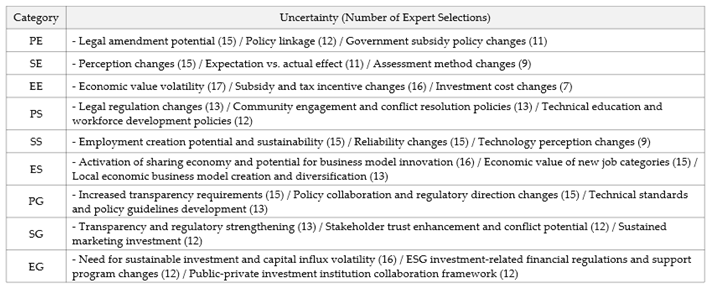

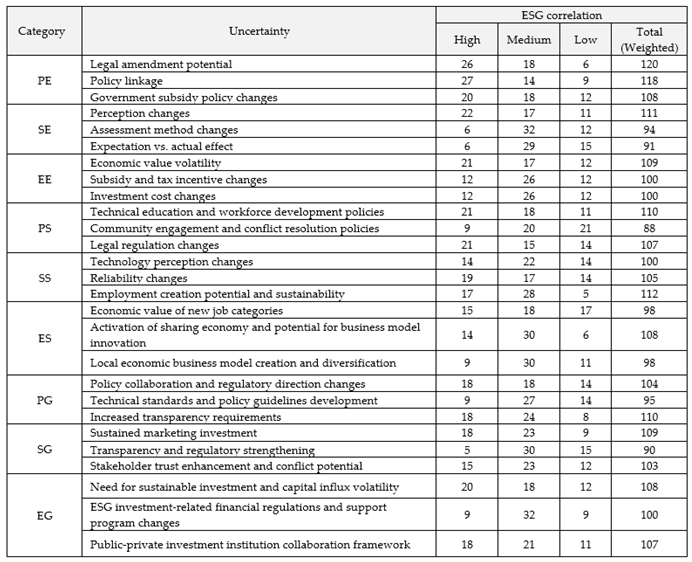

3.1.4. Stage 4: Selection of Secondary Uncertainty Factors

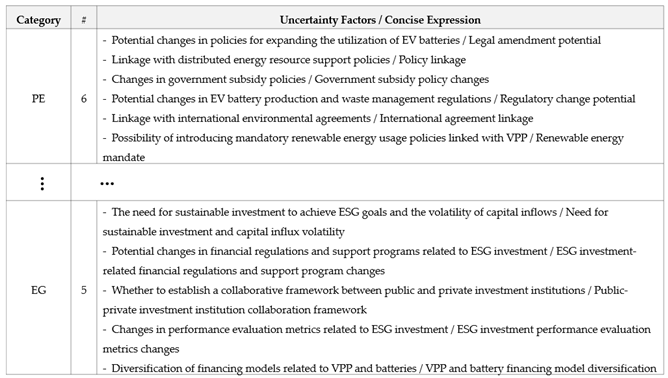

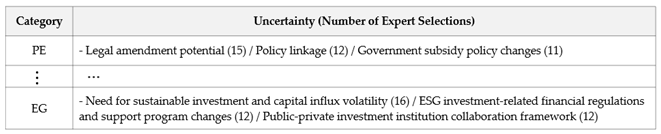

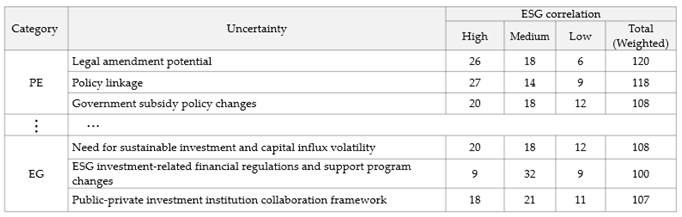

The second-stage selection of uncertainty factors aimed to systematically incorporate diverse perspectives and practical insights from the first-stage results to identify uncertainty factors for quantitative analysis using the Monte Carlo simulation technique. This phase was conducted considering that the uncertainty factors would be progressively refined in the subsequent stages. The survey was conducted from 4 October to 15 November 2024 and was structured using a combination of a three-point scale and open-ended questions [

36,

37]. In particular, because EV battery VPP resource utilization is expected to have significant impacts not only in economic and technological aspects, but also in the environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) domains, the second-stage uncertainty selection process included an assessment of the ESG relevance of each factor through a survey. Respondents evaluated the ESG relevance of each uncertainty factor by selecting “high,” “medium,” or “low,” and a three-point scale weighting was applied to the selected responses to ensure both efficiency and consistency in quantifying the scores of each uncertainty factor [

45]. Based on aggregated weighted scores, the factor with the highest total score in each domain was selected.

This ESG assessment approach enables a broader consideration of diverse perspectives such as environmental sustainability, social acceptance, and transparent governance. Consequently, this study contributes to a comprehensive review of the long-term sustainability of the energy industry, investment attraction, and policy and regulatory alignment. The survey was conducted with an “expanded expert group” of 50 professionals from various sectors including government agencies, public institutions, corporations, and academia. The group comprised four policymakers, two experts in policy formulation and regulatory operations, eight public institution representatives, 32 corporate professionals overseeing EV projects, and four energy research specialists. By leveraging their field experience and expertise, these experts conducted a multifaceted and in-depth evaluation of the uncertainty factors associated with EV battery VPP resource utilization. Ultimately, this approach provided highly relevant and reliable data, significantly enhancing the practical applicability and credibility of the study’s findings.

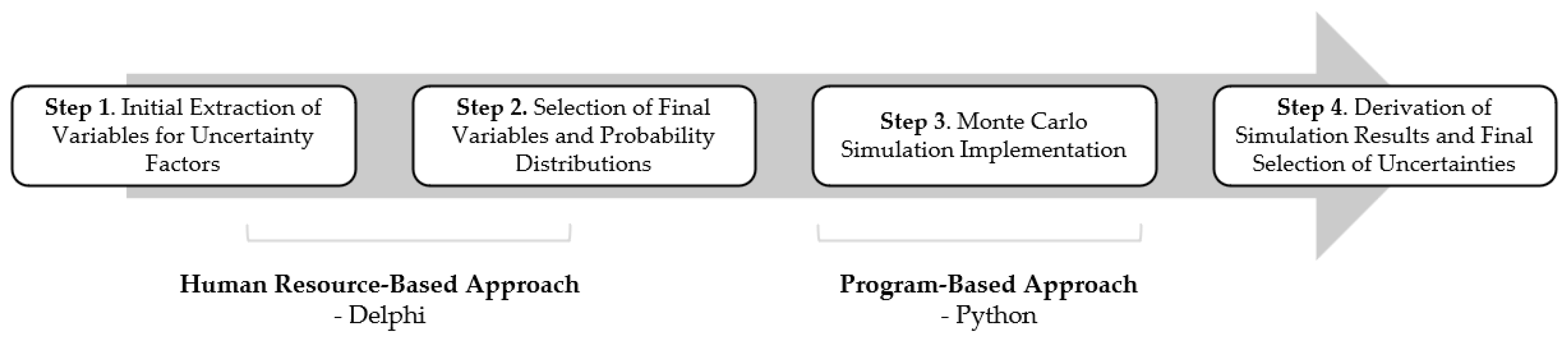

3.1.5. Stage 5: Selection of Final Uncertainty Factor

The final selection of uncertainty factors was based on the procedure outlined in

Figure 2, with a primary focus on identifying the key uncertainty factors necessary for deriving final scenarios [

40,

41].

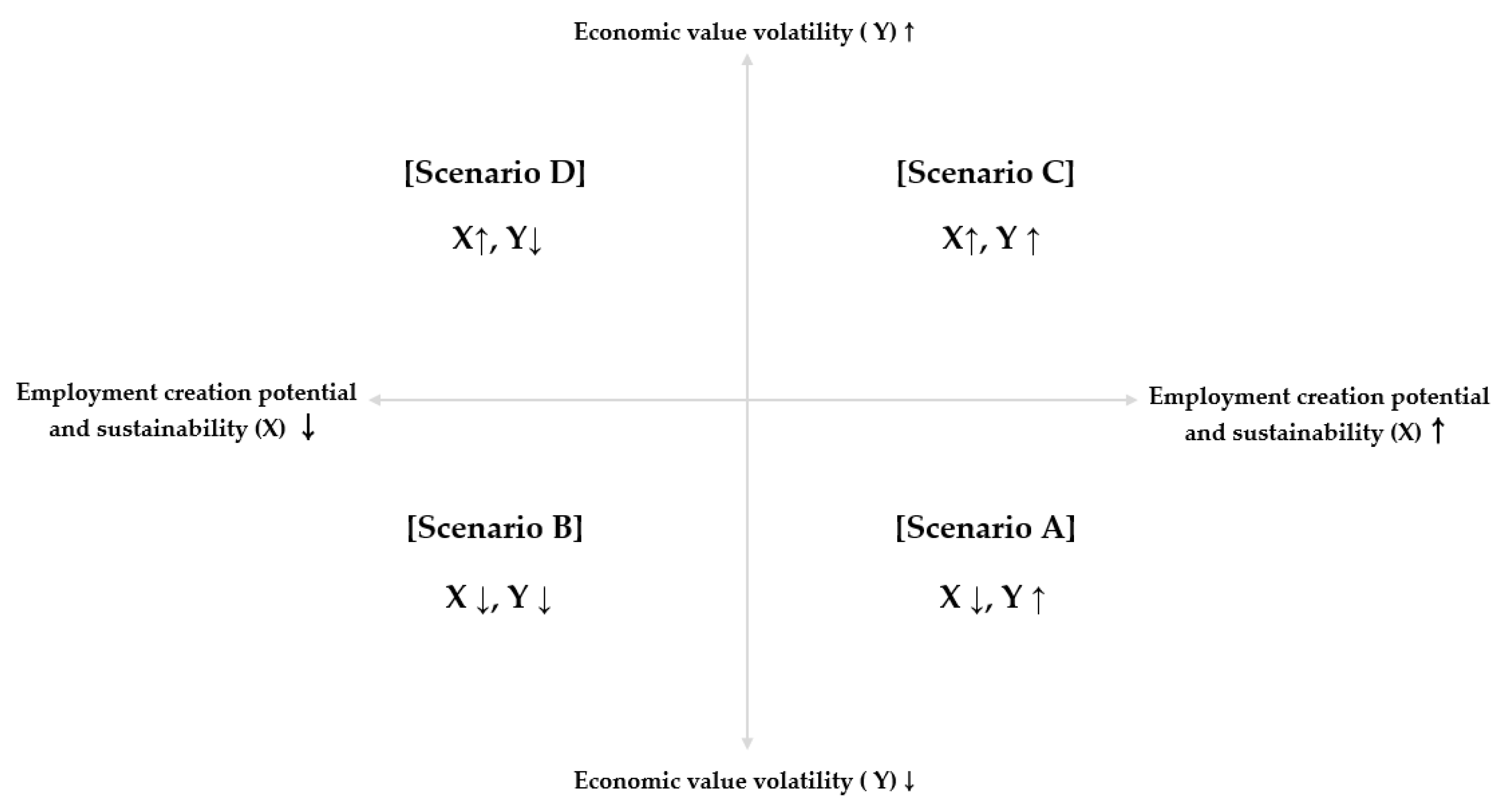

Traditional studies employing a 2×2 scenario matrix typically generate four outcome scenarios by combining the X- and Y-axis factors [

46]. However, this study aims to comprehensively consider the uncertainties across various ESG domains. Therefore, instead of relying solely on the X- and Y-axes, an additional sub-factor was incorporated, resulting in the selection of three key uncertainty factors. Specifically, a 2×2 matrix was constructed using two core uncertainty factors, whereas the remaining uncertainty factor was integrated as a subfactor within each scenario. This approach was designed to reduce strategic complexity while systematically analyzing the influence of additional variables [

47,

48].

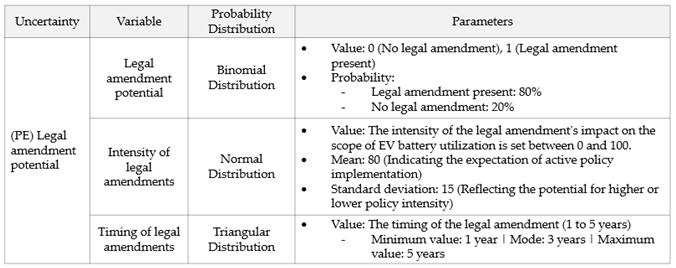

To derive the variables and probability distributions of the uncertainty factors consistently, the same optimal experts who participated in the “initial and first-round uncertainty factor selection” conducted multiple rounds of interviews [

31]. Through this process, the initial variables were identified, followed by a further exchange of opinions and a consensus-building process that led to the final selection of variables and probability distribution parameters. Subsequently, to conduct an objective data-driven probability analysis, a Monte Carlo simulation was performed using Python [

25]. By combining expert-based research with program-based analysis, this study addresses the limitations of traditional qualitative scenario planning and provides more specific and quantitative strategic analysis results.

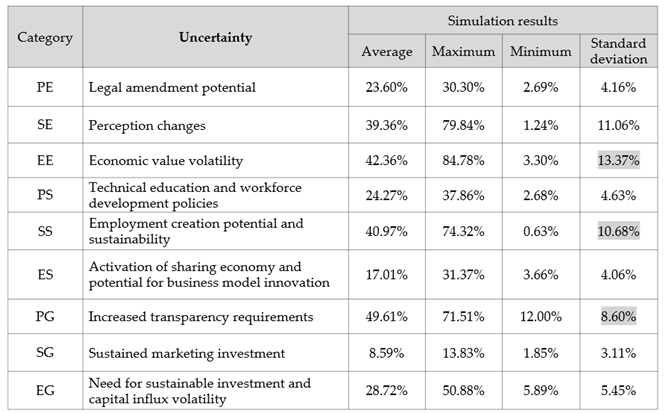

In this study, each uncertainty factor and variable, selected based on the collective intelligence of the expert group derived through multiple interviews, was considered a critical element influencing actual market growth and resource promotion. As their combination is deemed suitable for explaining overall market growth [

49], the market growth rate was set as the outcome variable in the simulation. A Python code was designed to extract the maximum, median, minimum, and standard deviation values of the market growth rate from the simulation results [

39]. Using this program, 1,000,000 simulation results were generated for each uncertainty factor, and the analysis identified the uncertainty factors with the largest standard deviation of the market growth rate, selecting one from each ESG domain. These factors were confirmed as final uncertainty factors [

41]. We selected high-uncertainty factors as “final uncertainties” because they are the most influential in scenario techniques and future prediction studies, with a high likelihood of significantly shaping future scenarios [

47]. The specific processes and detailed results for each stage are described in the following sections.

Step 1: Initial extraction of variables for uncertainty factors. This stage aims to derive the variable values necessary to execute the Monte Carlo simulation of the selected secondary uncertainty factors [

50]. Given the constraints in securing experts with high policy and technical expertise in the early stages of research and commercialization, a semi-structured interview method was adopted, as in the initial uncertainty identification stage, to enhance communication efficiency, facilitate consensus building, enable focused discussions, and derive in-depth conclusions through specialized expertise [

43,

44]. The experts involved in this process were the same as those who participated in the initial uncertainty identification stage. They engaged in flexible communication through various methods, including in-person meetings, video conferences, and phone interviews, to gather in-depth information regarding the questions outlined in

Table 2 [

33,

34]. The interviews were conducted from 18–30 November 2024, and the initial interview questions for variable extraction were structured to assess the impact of uncertainty factors on future outcomes. (See Appendix Table A2 for the full list of questions).

Step 2: Selection of final variables and probability distributions. In this study, we selected the final variables to enhance the depth of analysis and validity of the results by prioritizing and rigorously evaluating key variables, similar to the process used for selecting uncertainty factors. This approach considers that not all initially identified candidate variables hold equal importance [

44]. The initially derived variables undergo an additional consensus-building process to refine the selection and determine the final set of variables. This process minimizes the model complexity and unnecessary noise caused by excessive variable inclusion while ensuring a balanced approach that effectively captures the critical aspects of key uncertainties [

50]. Thus, the initially derived variables for each uncertainty factor were disclosed to the same group of experts, who were asked to reselect the variables they deemed to have significant external influence [

50]. For consistency with the first-stage uncertainty factor selection, “significant external influence” was defined as variables with the potential to induce widespread changes or cascading effects across the broader external environment, including political, economic, social, technological, and ESG dimensions. This multistage approach aligns with the objective of improving both research efficiency and analytical accuracy [

44].

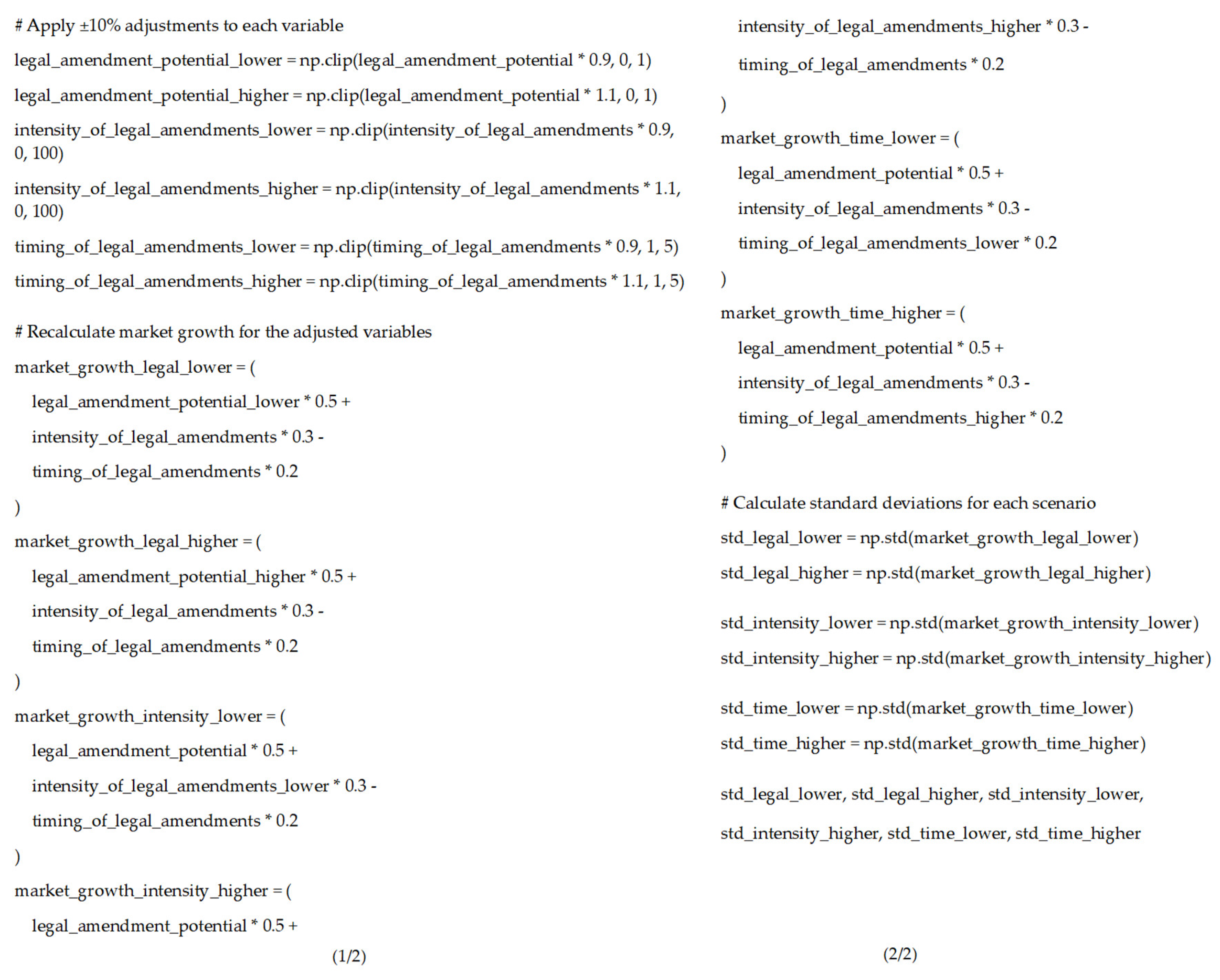

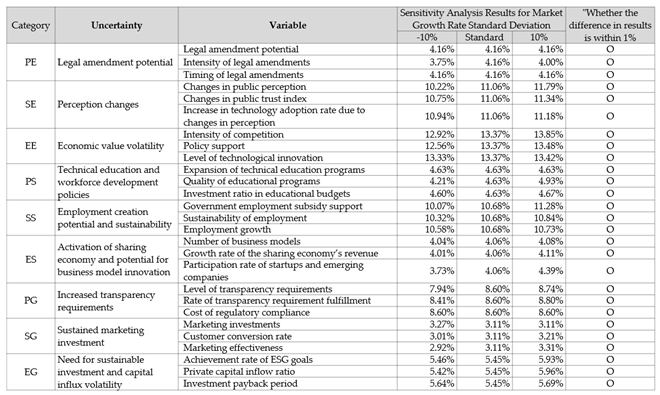

The procedure for selecting the probability distributions for each variable begins with a literature review and theoretical foundations, based on which the researcher predefines the target variables and their uncertainty ranges. Subsequently, we interviewed a group of optimal experts through semi-structured interviews to gather their opinions on the key parameter values. Subsequently, a consensus was reached, and feedback was incorporated to derive representative probability distributions using qualitative consensus techniques [

51,

52]. A sensitivity analysis was then performed to evaluate the impact of variable variability on the scenario outcomes. This process helps acquire additional data to reduce the uncertainty of key variables or improve the modeling process [

53,

54]. In this study, the key parameters (e.g., 70%) were adjusted within a ±10% range (e.g., 60%, 80%) for sensitivity evaluation [

55,

56]. This step plays a crucial role in assessing the impact of variable uncertainty on scenario outcomes and examining the influence of the probability distribution values on the overall simulation results [

50].

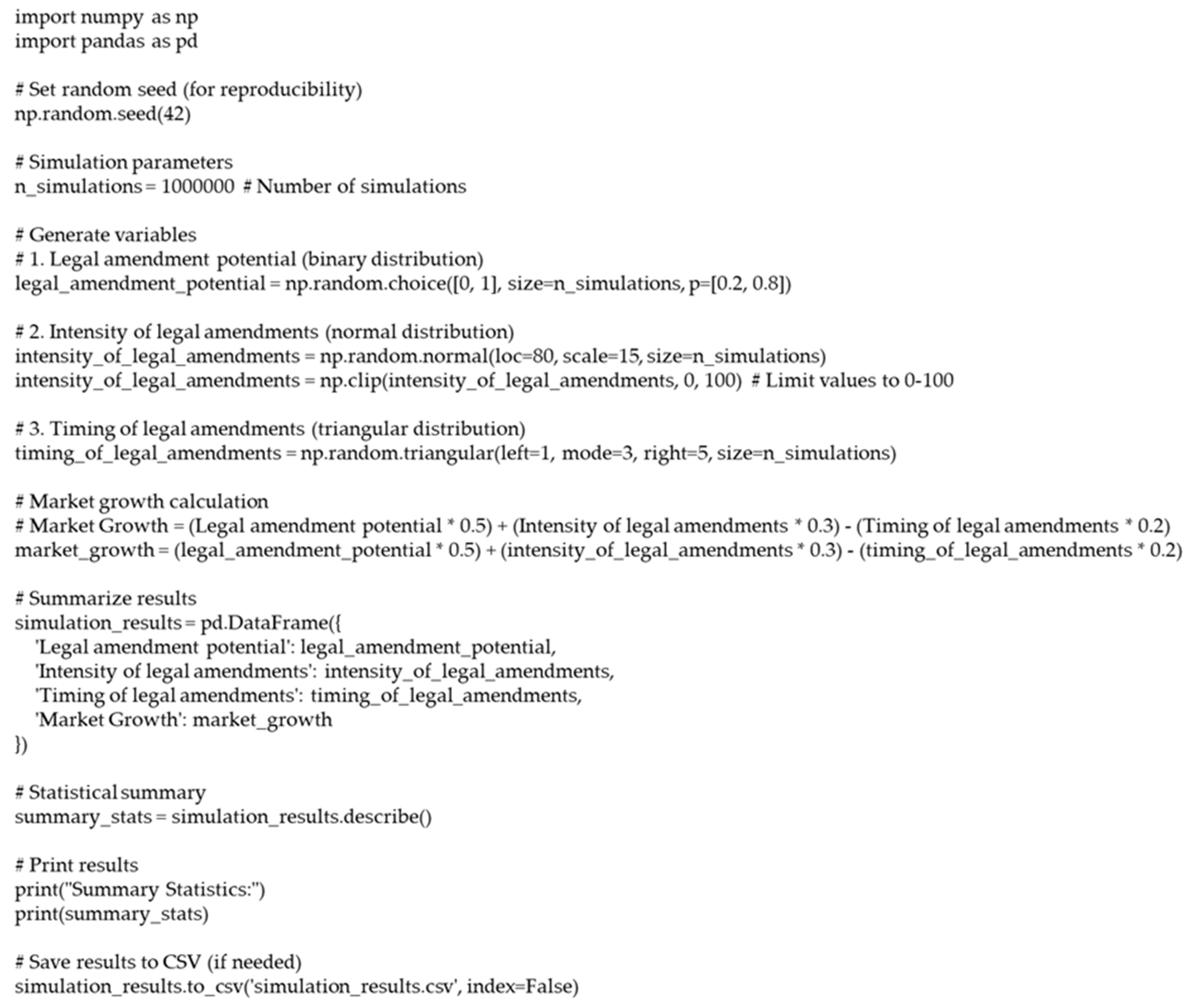

Step 3: Monte Carlo simulation implementation. Python is an open-source general-purpose programming language that enables the efficient and rapid implementation of complex Monte Carlo simulations by leveraging various scientific and numerical computation libraries, such as NumPy, SciPy, pandas, and matplotlib [

57]. The Monte Carlo simulation is a statistical technique that assesses model uncertainty by generating random numbers and simulating probability distributions. Python’s vectorized operations and random number generation capabilities are well-suited for such tasks, allowing for precise results [

25]. The following key components of the Python code were designed for this study:

Conducted 1,000,000 simulation iterations.

Fixed the random seed to ensure the reproducibility of results upon code execution.

Incorporated the final selected variables and probability distribution data based on prior consensus.

Utilized DataFrame.describe() to summarize descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, etc.) for each variable, and displayed the results using the print() function.

Step 4: Derivation of simulation results and final selection of uncertainties. In this stage, the results obtained from the Monte Carlo simulation were analyzed, and the final uncertainty factors were selected based on this analysis. The simulation results were evaluated by assessing the impact of each uncertainty factor on the market growth rate and analyzing their statistical characteristics, including standard deviation. The final uncertainty factors were primarily selected based on the factors with the highest standard deviations among the simulation results [

41]. Through this process, the most critical uncertainty elements in each ESG domain were identified.