1. Introduction

Hematopoiesis is the process of blood cell formation. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) sustain the blood system by generating blood cells of all lineages through multipotent progenitors [

1,

2]. During prenatal life, the hematopoietic system has two key roles: rapidly generating mature blood cells essential for fetal growth and development and establishing a reservoir of HSCs required for postnatal life. These cells have the ability to self-renew and differentiate into two types of multipotent cells: myeloid and lymphoid. Their division can produce either multipotent cells or differentiated unipotent stem cells, which further divide and differentiate into morphologically recognizable cells of a single lineage [

3,

4].

In postnatal life, hematopoiesis occurs exclusively in the bone marrow, but during prenatal development, it takes place at different anatomical sites across three waves [

5,

6].

The first wave begins extraembryonically, around day 7 of embryogenesis, in the yolk sac, generating primitive red blood cells, macrophages, and a few megakaryocytes. Blood islands form in the extraembryonic mesoderm, producing these primitive blood cells [

7]. The second wave, definitive hematopoiesis independent of HSCs, also starts in the yolk sac around day 8 of embryonic development. Lymphomyeloid progenitors and erythromyeloid progenitors migrate to the fetal liver, supporting embryonic survival during mid-gestation [

8]. The third wave, HSC-dependent hematopoiesis, occurs in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region, initially in the dorsal aorta and later in major arteries (vitelline and umbilical arteries) and the chorionic plate mesenchyme of the placenta. From these locations, HSCs migrate to temporary hematopoietic niches: the liver, placenta, spleen, and bone marrow [

9]. In 2005, researchers proposed that the placenta is not just a reservoir of HSCs derived from other locations but also a site of hematopoiesis [

10,

11].

The placenta, a temporary organ essential for normal fetal growth and development, is unique in consisting of tissues of dual origin—maternal and fetal. Its role is critical in fetal development, with numerous functions. Placental development begins around days 7–8 post-fertilization with the implantation of the blastocyst into the decidually transformed endometrium, influenced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E3 [

12].

It is hypothesized that the development of placental blood vessels parallels HSC development, as endothelial cells and HSCs share common progenitors. The hematopoietic microenvironment of the placenta is a dynamic and multifaceted niche that supports early blood cell development. It includes various cells, extracellular matrix components, growth factors, cytokines, and adhesion molecules, creating a specialized environment that enables HSC proliferation, differentiation, and maintenance during critical fetal development stages. This microenvironment promotes HSCs proliferation while preventing premature differentiation into various cell lineages [

13].

Hematopoietic stem cells exhibit morphological characteristics similar to small or medium-sized lymphocytes, with diameters of 7–8 µm. They possess a centrally located round nucleus surrounded by a cytoplasmic rim. Identification relies on surface-expressed markers, such as CD34 and CD117, which have been widely used for detecting hematopoietic stem cells [

4,

13].

HSC types in the placenta presents a challenge in distinguishing HSCs originating in the placenta from those arriving via circulation from other hematopoietic niches. Studies using Runx1-lacZ and Runx1+/− knockout mice, which lack cardiac activity and blood flow to the placenta, have identified CD41 immunoreactive HSC populations [

14].

CD34 is a transmembrane phosphoglycoprotein initially identified on HSCs and progenitor cells, including pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (PHSCs) and colony-forming units (CFU-GEMM). CD34 expression is almost universally associated with hematopoietic cells and is also found on endothelial cells and embryonic fibroblasts [

15,

16,

17].

CD117 (c-kit) is a class III tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptor for stem cell factor, encoded by the proto-oncogene c-kit. It identifies human HSC populations with high proliferation and self-renewal potential and is expressed on germ cells, melanocytes, mast cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal [

18,

19].

CD41 (integrin αIIb) is a heterodimeric integral membrane protein, a marker for early embryonic HSCs, also expressed on platelets and megakaryocytes [

20].

Using placentas post-delivery in regenerative medicine is a current trend due to their availability and the abundance of stem cells and growth factors they contain. While the placenta's role in hematopoiesis is established, the exact localization, distribution, and differentiation potential of HSCs isolated from the placenta remain incompletely defined. The study aims to determine the presence of hematopoietic stem cells in placentas of different gestational ages, their localization within the placenta, and their abundance using numerical areal density (NA), to evaluate the placenta as a suitable source for HSCs isolation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Placenta Sampling

The study was conducted in accordance with the latest revision of the Helsinki Declaration, with approval from the Ethics Committee (No: 18/4.167/21). Placental samples were collected at the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics and the Pathology Department of the University Clinical Center of the Republika Srpska (UCC RS). Placentas were sampled in all periods of gestation in the first, second and third trimesters (

Table 1). In the human population, pregnancy lasts 40 weeks and is divided into trimesters, the first lasting from 0-13 weeks of gestation, the second up to 14-27 weeks of gestation and the third trimester from 28 to 40 weeks of gestation. Placentas of the first trimester were sampled at the Department of Pathology of the RSC RS, as part of intratubal pregnancies that were referred for pathohistological verification after fallopian tube rupture. Already existing pathohistological paraffin molds from the departmen’s collection were used, and all parts of the placenta were preserved, and where there was no coagulum and inflammatory infiltrate that could interfere with the visualization and analysis of the placental tissue. Placentas of the second trimester were sampled after premature births within this gestation. Only samples without macroscopically visible deviations were included in the study. Placentas of the third trimester were sampled at the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics, after vaginal delivery. Our recent study clearly showed that both, maternal age and gestational age significantly affect placental morphology, so all samples were from healthy pregnant women under 35 years of age, with no chronic non-communicable diseases, infections, or smoking history in their medical records [

21].

2.2. Tissue Processing

Samples from ectopic pregnancies included the entire circumference of the fallopian tube. Second and third-trimester samples were 2x2 cm in size, covering the full thickness of the placenta from the chorionic to basal plate. After 48 hours of fixation in 4% formaldehyde, the samples were processed in a Leica TP1020 tissue processor, embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned into 4 µm slices, and stained using hematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemistry for CD34 (anti-CD34 monoclonal antibody, 1:100, Abcam), CD117 (c-Kit monoclonal antibody, 1:100, Invitrogen), and CD41 (rabbit polyclonal anti-CD41 antibody, 1:200, Invitrogen). Antigen retrieval was performed by heating in citrate buffer (pH 6) for 20 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Nonspecific background staining was blocked using UltraVision Block. Primary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes, and visualization was done using the HRP/DAB IHC detection system (Abcam). Counterstaining was performed with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Analyses were conducted using a Leica DM6000 microscope equipped with a Leica DFC310FX camera.

The intensity of immunoreactivity for CD34, CD117, and CD41 was semi-quantitatively graded as low (+), moderate (++), or high (+++).

2.3. Morphometric Analysis

In order to quantify CD34, CD117 and CD41 immunopositive hematopoetic cells, we determined their numerical areal density, average number of cells in 1 mm2 of tissue, (NA) with the ImageJ software (version 18.0). Numerical areal density represents the number of analyzed cells, CD34, CD117, and CD41 immunoreactive cells, relative to the surface area of the field of view. Numerical areal density was calculated using the formula NA = N/A, where N is number of analyzed imunoreactive cells cells (N), and A field of view area.

The number of examined fields of view (N) was determined using the formula N=(20×SD/X)

2, where SD is the standard deviation and X is the mean value of results obtained in a pilot study conducted on 20 fields of view (Kališnik M, 2002) [

21].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of the collected data was performed using the R 4.2.3 statistical software package.

Descriptive statistics were used to determine frequencies, measures of central tendency, measures of variability, and for graphical representation of the results.

The Chi-square test (χ2, Chi-square Test) was used to compare the frequencies of occurrence of categorical variables in independent samples.

The statistical analysis of numerical data and the selection of an appropriate test depended on the distribution of numerical data. Normality of distribution was determined based on skewness values (from -3 to +3 indicating normal distribution) and kurtosis values (from -1 to +1 indicating normal distribution), as well as the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Student's t-test (T-test for two independent samples) was used to compare the mean values of two independent samples with a normal distribution of numerical data. In cases of deviation from normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for two samples.

The homogeneity of variances for more than two groups was tested using Levene's test. After statistical analysis and the application of Levene's test, ANOVA (p > 0.05 from Levene's test) or the Kruskal-Wallis Test (p < 0.05 from Levene's test) was used. For comparing mean values of numerical data across more than two independent samples with a normal distribution of numerical data and p > 0.05 after Levene's test, ANOVA was applied. In contrast, the Kruskal-Wallis Test was used as a nonparametric test.

All results were considered statistically significant if p ≤ 0.05 and highly statistically significant if p < 0.001. In cases where highly statistically significant results were obtained, the level of statistical significance (<0.001) was reported.

3. Results

The differences in placental structure across various gestational periods are most pronounced in the composition of the chorionic villi. In first-trimester placentas, up to the 10th week of gestation, mesenchymal chorionic villi are the most abundant, along with a few immature intermediate villi. The number of immature intermediate villi increases after the 10th week of gestation. During the second trimester, mature intermediate villi dominate, while in the third trimester, both mature intermediate and terminal villi are present.

The mesenchymal type of villi consists of mesenchymal stroma with sparse blood vessels, whose lumen is not visible. The stroma is surrounded by two layers of trophoblastic cells: cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts. Immature intermediate villi contain numerous stromal channels within their stroma, formed by the merging of cytoplasmic extensions from stromal cells. Numerous blood vessels are observed within the stroma. On the surface of the villi, the syncytiotrophoblast layer is more pronounced, with individual cytotrophoblastic cells located beneath it. In intermediate and terminal villi, the number of blood vessels within the stroma increases, while only the syncytiotrophoblast is observed on the surface (

Figure 1).

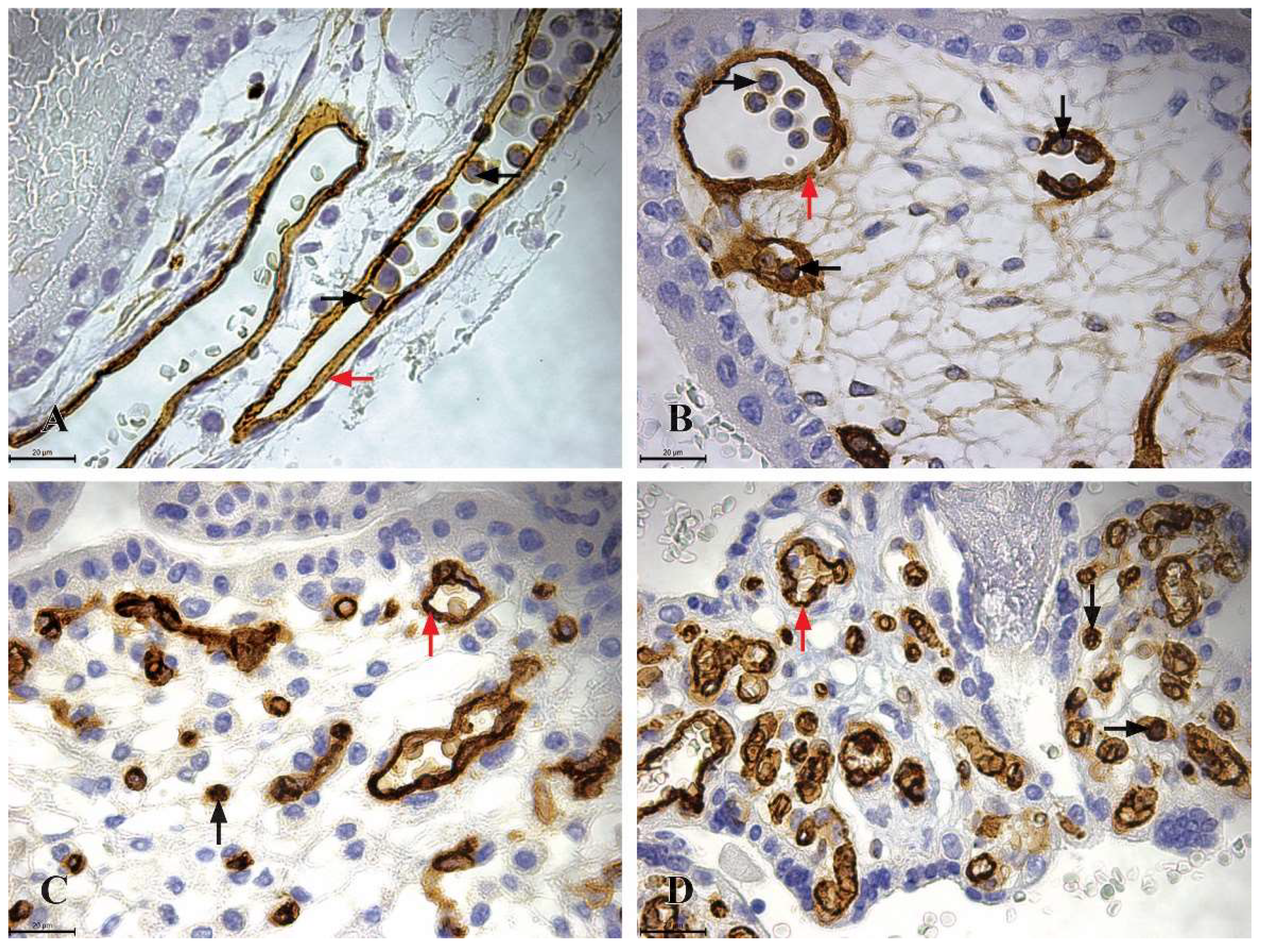

The CD34 immunoreactive cells are present in placentas across all trimesters, exhibiting consistent morphology throughout. These cells are approximately 7 µm in size, round in shape, with a centrally located round nucleus surrounded by a variable amount of cytoplasm. During the first trimester, highly immunoreactive CD34 hematopoietic stem cells (+++) are abundant, appearing as clusters within the lumen of blood vessels in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi. In the second trimester placenta samples the CD34 immunoreactive cells are observed within the mesenchyme of placental villi as individual cells. In the third trimester placenta samples the highly immunoreactive CD34 hematopoietic stem cells are located in the mesenchyme of villi and the chorionic plate. Hovewer, these cells are absent from the lumen of blood vessels (

Figure 2).

The mean numerical areal density data of CD34 immunoreactive HSCs at different gestational ages are shown in

Table 2. A significant difference in arithmetic means was observed between the second and third trimesters (p=0.01). However, no statistically significant difference was found between the arithmetic means of the first and second trimesters (p=0.6) or between the first and third trimesters (p=0.07).

Highly immunoreactive CD34 expression (+++) was also observed in endothelial cells of placental blood vessels (

Figure 2).

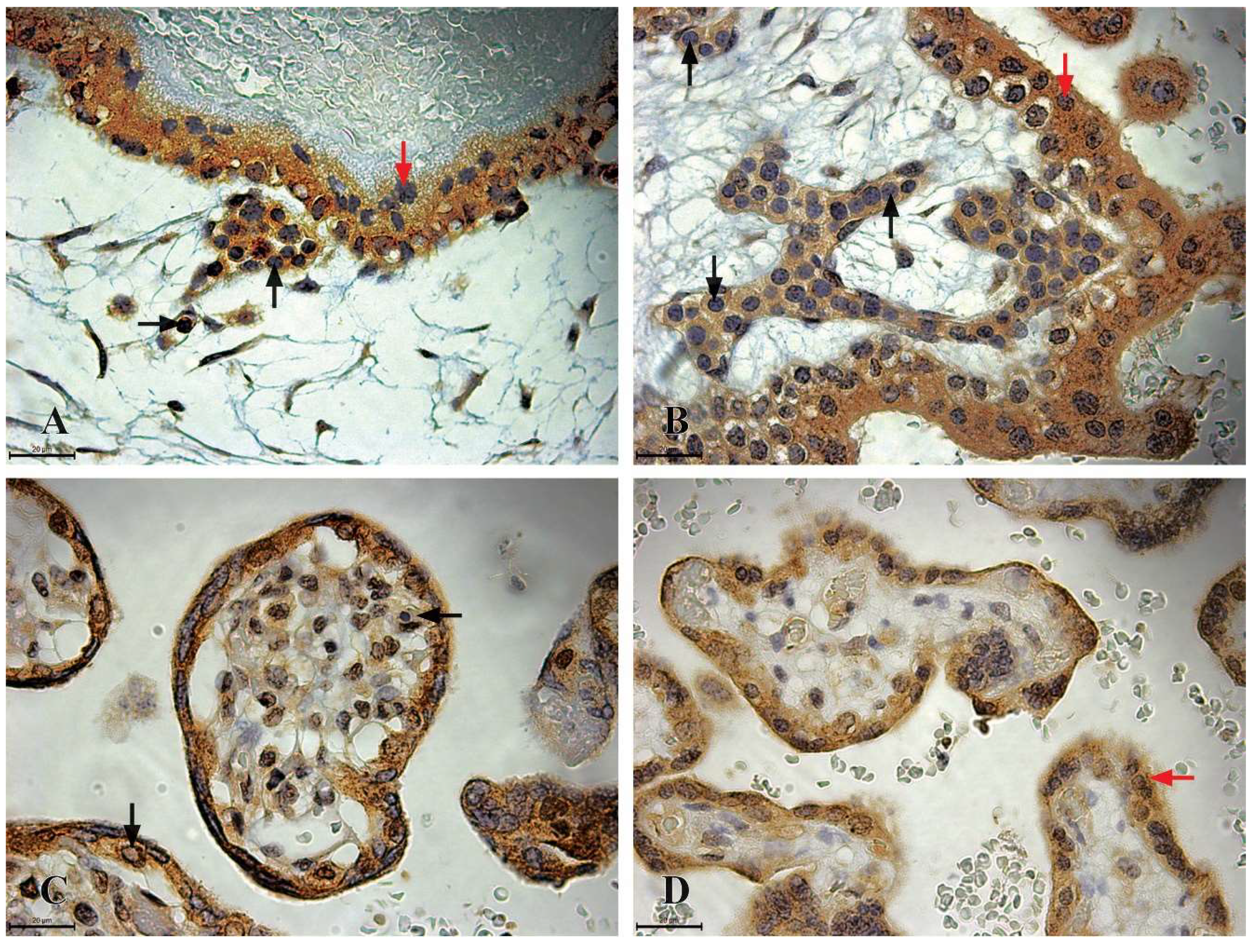

Highly immunoreactive CD117 cells (+++), morphologically resembling HSCs, are present in the placentas of the first and second trimesters. These cells, similar to CD34-positive cells, are approximately 7 µm in size, round in shape, with a centrally located round nucleus surrounded by a variable amount of cytoplasm (

Figure 4). In the first trimester placenta sample the highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs cells can be found in clusters within the lumen of blood vessels in the chorionic plate and villi, as well as individually within the mesenchyme of villi. In the second trimester these cells can be observed only within the mesenchyme of chorionic villi (

Figure 3).

Trophoblastic cells, including cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, express CD117 immunoreactivity in all trimesters, although its intensity decreases with advancing gestation. Cytotrophoblasts are uniform, cuboidal cells with a central nucleus and abundant cytoplasm. They exhibit high CD117 immunoreactivity (+++) in the first trimester but low reactivity (+) in the second and third trimesters. Syncytiotrophoblasts are irregularly shaped, variably sized cells. These show high CD117 immunoreactivity (+++) in the first and second trimesters, which decreases to moderate reactivity (++) in the third trimester (

Figure 3).

The mean numerical areal density data of CD117 immunoreactive HSCs at different gestational ages are shown in

Table 3. No significant statistical difference was found in the medians between the first and second trimesters (p>0.05).

CD41 immunoreactive cells first appear after the 11th week of gestation up to 22 weeks of gestation and they are localized exclusively within the mesenchyme of chorionic villi. These cells exhibit high immunoreactivity (+++) and share the same morphological features as CD34 and CD117-positive cells. In the second trimester the number of CD41 cells decreases while maintaining their first-trimester localization. In the third trimester placenta samples the CD41 immunoreactive cells are absent (

Figure 4).

The mean value of NA of two sample of CD41-positive HSCs was 54.1± 1,9 in the first trimester. The mean NA of four samples of the second trimester placentas was 49,6±8,7. Due to the sample size, a comparison for the values of NA CD41 immunoreactive cells was not conducted.

The mean values of N

A of CD34 immunoreactive cells are higher than those of Na CD117 immunoreactive cells, but the difference between the two groups is not statistically significant (p>0.05). In the second trimester, N

A values of CD34 immunoreactive cell values are higher than those of N

A CD117 and CD41 immunoreactive cells. The difference between the groups is statistically significant (p≤0.05) (

Table 4.).

4. Discussion

The placenta represents a rich source of hematopoietic stem cells with diverse profiles and phenotypes. Besides functioning as a temporary hematopoietic niche, it is also a primary site of HSC development during embryogenesisc [

23,

24]. HSCs are present in the placenta throughout the entire gestational period [

25]. Our study confirmed the presence of CD34 immunoreactive HSC populations throughout gestation, while CD117 immunoreactive cell populations were found between the 7th and 24th weeks of gestation, and CD41 immunoreactive cell populations were found only between the 11th and 22th weeks of gestation.

The CD34 immunoreactive cell population was the most abundant, reaching its peak during the second trimester. Similarly, the populations of CD117 and CD41 cells were most numerous in the second trimester, suggesting the migration of HSCs from the placenta to other hematopoietic niches by the end of this period.

After the 24th week of gestation, the presence of CD34 immunoreactive HSCs in the placenta decreases significantly, coinciding with the establishment of hematopoiesis in the fetal liver and bone marrow, which become the main hematopoietic sites during later gestation [

26]. During the first two trimesters, the placenta exhibits higher N

A of CD34 and CD117 cells compared to the fetal liver, whereas these values significantly increase in the liver after the 24th week of gestation. The advantages of using HSCs from the placenta for therapeutic purposes, as compared to traditional sources, are primarily rooted in their availability. Therefore, the discovery of a population of CD34 immunoreactive cells in term placentas is highly significant.

Although CD34 is a key marker for blood progenitor cells, it is also expressed by endothelial cells and embryonic fibroblasts. However, based on the morphology of the cells, their location, and the intensity of immunopositivity, it can be confidently concluded that these cells are the HSCs. Quantification of immunoreactive cells using flow cytometry often provides total concentrations of all CD34-expressing cells, including endothelial cells and fibroblasts, which may explain the discrepancy between our results and those of other studies [15, 27-29]. Earlier studies have emphasized that HSCs are restricted to the chorion and chorionic villi [

30]. However, we observed that in addition to being located in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi, populations of CD34 and CD117 immunoreactive cells were also present within blood vessels. We hypothesize that HSCs within the blood vessels are not primarily generated in the placenta but are transported there via blood from other hematopoietic niches. In contrast, cells localized in the mesenchyme of the placental villi likely originate in the placenta from hemangioblasts or mesenchymal progenitors. Supporting this is the finding that CD41 immunoreactive cells are exclusively present in the mesenchyme of chorionic villi, which was previously confirmed to be a marker of HSCs generated in the placenta [

14].

This dual origin of HSCs in the placenta may also explain the differences in N

A values for CD34 and CD117 populations. It is belived that CD117 immunoreactive cells originate from mesenchymal progenitors, while CD34 immunoreactive cells are derived from hemangioblasts [

31,

32]. Since the N

A values of CD34 immunoreactive cells are higher compared to the other populations studied, it can be concluded that placental HSCs are predominantly of hemangioblast origin. The labyrinthine vasculature, along with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are also part of the placental niche, provides the necessary conditions for HSC self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation. This is reflected in the higher abundance of HSCs in the mesenchyme compared to the lumen of blood vessels in the placenta [13, 33].

The majority of HSCs in blood vessels will differentiate into erythrocytes by the 14th week of gestation to ensure adequate oxygen supply to the growing fetus. The placenta is likely the primary site where erythrocyte maturation begins, including the loss of erythroblast nuclei under the influence of mesenchymal and Hofbauer cells [

34].

The results of our study indicate that, in addition to hematopoietic progenitors, trophoblast cells also exhibit CD117 immunoreactivity, with trophoblasts of the first-trimester placenta showing high levels of immunoreactivity. However, the intensity of immunoreactivity decreases as gestation progresses. Since CD117 is a marker for stem progenitor cells, these trophoblast cells possess a high capacity for proliferation and differentiation. Their numbers, as well as their ability to proliferate and differentiate, decrease as pregnancy advances [

34].

It is important to note that the identified HSCs in the placenta have the potential for proliferation, indicating that they are mature cells and can be used as transplants. Populations of CD34 and CD117 immunoreactive cells have the ability for multilineage and definitive differentiation [30, 36–38].

5. Conclusions

The placenta is a dynamic hematopoietic microenvironment that contains diverse populations of hematopoietic stem cells. Immunoreactive cells expressing CD34, CD117, and CD41 are present in various regions of the placenta throughout gestation, contributing significantly to hematopoiesis.

Since the term placenta is available after birth, it can serves as a valuable source of HSCs. Future research should focus on optimizing conditions for the clinical application of HSCs isolated from the placenta.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization S.J. and I.N.; methodology, S.J. and I.N.; software, S.J. and M.B.; validation, S.J., I.N. and R.S.; formal analysis, S.J.; investigation, S.J.; resources, S.J.; data curation, S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, I.N. and R.S.; visualization, V.LJ. and LJ.A.; supervision, I.N. and R.S.; project administration, R.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of this study was funded by grants for scientific projects (No. 451-03-65/2024-03/200113) provided by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the latest revision of the Helsinki Declaration, with approval from the Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka (No: 18/4.167/21).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings can be found within the manuscript

Acknowledgments

Part of this study was funded by grants for scientific projects (No. 451-03-65/2024-03/200113) provided by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thambyrajah, R.; Bigas, A. Notch Signaling in HSC Emergence: When, Why and How. Cells 2022, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Hong, S.H. Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Their Roles in Tissue Regeneration. Int J Stem Cells. 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gekas, C.; Rhodes, K.E.; Van Handel, B.; Chhabra, A.; Ueno, M.; Mikkola, H.K. Hematopoietic stem cell development in the placenta. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010, 54, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjos-Afonso, F.; Bonnet, D. Human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell hierarchy: How far are we with its delineation at the most primitive level? Blood 2023, 142, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Jardine, L.; Gottgens, B.; Teichmann, S.A.; Haniffa, M. Prenatal development of human immunity. Science 2020, 368, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, B.; Maillard, I. Fetal hematopoietic stem cells are making waves. Stem cell Investigation 2017, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, K.E.; Palis, J. Hematopoiesis in the yolk sac: More than meets the eye. Experimental hematology 2005, 33, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierzak, E.; Philipsen, S. Erythropoiesis: Development and differentiation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2013, 3, a011601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacaud, G.; Kouskoff, V. Hemangioblast, hemogenic endothelium, and primitive versus definitive hematopoiesis. Experimental hematology 2017, 49, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gekas, C.; Dieterlen-Lièvre, F.; Orkin, S.H.; Mikkola, H.K. The placenta is a niche for hematopoietic stem cells. Developmental cell 2005, 8, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, H.K.; Gekas, C.; Orkin, S.H.; Dieterlen-Lievre, F. Placenta as a site for hematopoietic stem cell development. Experimental hematology 2005, 33, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, O.W. Novel tissue interactions support the evolution of placentation. Journal of morphology 2021, 282, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo Portilho, N.; Pelajo-Machado, M. Mechanism of hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in mouse placenta. Placenta 2018, 69, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, K.E.; Gekas, C.; Wang, Y.; Lux, C.T.; Francis, C.S.; Chan, D.N.; Conway, S.; Orkin, S.H.; Yoder, M.C.; Mikkola, H.K. The emergence of hematopoietic stem cells is initiated in the placental vasculature in the absence of circulation. Cell stem cell 2008, 2, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, L.E.; Branch, M.J.; Dunphy, S.E.; Dua, H.S.; Hopkinson, A. Concise review: Evidence for CD34 as a common marker for diverse progenitors. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2014, 32, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, T.; Sun, X.; Lin, R.; He, Y.; Sun, K.; Han, J.; Yang, G.; Li, X.; et al. CD34+ cell-derived fibroblast-macrophage cross-talk drives limb ischemia recovery through the OSM-ANGPTL signaling axis. Science advances 2023, 9, eadd2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuSamra, D.B.; Aleisa, F.A.; Al-Amoodi, A.S.; Jalal Ahmed, H.M.; Chin, C.J.; Abuelela, A.F.; Bergam, P.; Sougrat, R.; Merzaban, J.S. Not just a marker: CD34 on human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells dominates vascular selectin binding along with CD44. Blood advances 2017, 1, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, L.; Sanfilippo, S.; Domenech, C.; Kasmi, N.; Petit, L.; Jacques, S.; Delezoide, A.L.; Guimiot, F.; Eladak, S.; Moison, D.; et al. CD117hi expression identifies a human fetal hematopoietic stem cell population with high proliferation and self-renewal potential. Haematologica 2020, 105, e43–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, L.; Ocqueteau, M.; Almeida, J.; Orfao, A.; San Miguel, J.F. Expression of the c-kit (CD117) molecule in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Leukemia & lymphoma.

- Hashimoto, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Shimoda, Y.; Huang, X.; Sakamoto, H.; Ogawa, M. Distinct hemogenic potential of endothelial cells and CD41+ cells in mouse embryos. Development, growth & differentiation 2007, 49, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Jovičić S, Ljubojević V, Barudžija M, Amidžić LJ, Škrbić, R.; Nikolić IR. Influence of advanced maternal age and gestational age on the morphology of human placenta. Scr Med. 2024 Nov-Dec;55, 727–734.

- Kališnik, M.; Eržen, I.; Smolej, V. [Foundations of stereology]. Ljubljana: Društvo za stereologijo in kvantitativno analizo slike (DSKAS); 2002. Slovenian.

- Mikkola, H.K.; Gekas, C.; Orkin, S.H.; Dieterlen-Lievre, F. Placenta as a site for hematopoietic stem cell development. Experimental hematology 2005, 33, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierzak, E.; Robin, C. Placenta as a source of hematopoietic stem cells. Trends in molecular medicine 2010, 16, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, C.; Bollerot, K.; Mendes, S.; Haak, E.; Crisan, M.; Cerisoli, F.; Lauw, I.; Kaimakis, P.; Jorna, R.; Vermeulen, M.; et al. Human placenta is a potent hematopoietic niche containing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells throughout development. Cell stem cell, 2009, 5, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladičić-Mašić, J.; Nikolić, I.; Todorović, V.; Jović, M.; Petrović, V.; Mašić, S.; Dukić, N.; Zečević, S. Numerical areal density of CD34 and CD117 immunoreactive hematopoietic cells in human fetal and embryonic liver. Biomedicinska Istraživanja 2019, 10, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, I.; Rustichelli, D.; Castiglia, S.; Gammaitoni, L.; Polo, A.; Pautasso, M.; Geuna, M.; Fagioli, F. Inter-laboratory method validation of CD34+ flow-cytometry assay: The experience of Turin Metropolitan Transplant Centre. EJIFCC 2023, 34, 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D.M.; Botting, R.A.; Stephenson, E.; Green, K.; Webb, S.; Jardine, L.; Emily, F.; Calderbank, E.F.; Polanski, K.; Goh, I.; et al. Decoding human fetal liver haematopoiesis. Nature 2019, 574, 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Notta F, Doulatov S, Laurenti E, Poeppl A, Jurisica, I.; Dick JE. Isolation of single human hematopoietic stem cells capable of long-term multilineage engraftment. Science 2011, 8;333, 218–221.

- Muench, M.O.; Kapidzic, M.; Gormley, M.; Gutierrez, A.G.; Ponder, K.L.; Fomin, M.E.; Beyer, A.I.; Stolp, H.; Qi, Z.; Fisher, S.J.; et al. The human chorion contains definitive hematopoietic stem cells from the fifteenth week of gestation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2017, 144, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai-Hernandez, P.; Pouget, C.; Eyal, S.; Svoboda, O.; Chacon, J.; Grimm, L.; Gjøen, T.; Traver, D. Dermomyotome-derived endothelial cells migrate to the dorsal aorta to support hematopoietic stem cell emergence. eLife 2023, 12, e58300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.; D’Souza, S.L.; Lynch-Kattman, M.; Schwantz, S.; Keller, G. Development of the hemangioblast defines the onset of hematopoiesis in human ES cell differentiation cultures. Blood 2007, 109, 2679–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sanchez, V.; Takata, N.; Yokomizo, T.; Yamanaka, Y.; Kataoka, H.; Hoppe, P.S.; Schroeder, T.; Nishikawa, S. (2014). Circulation-independent differentiation pathway from extraembryonic mesoderm toward hematopoietic stem cells via hemogenic angioblasts. Cell reports 2014, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Handel, B.; Prashad, S.L.; Hassanzadeh-Kiabi, N.; Huang, A.; Magnusson, M.; Atanassova, B.; Chen, A.; Hamalainen, E.I.; Mikkola, H.K. The first trimester human placenta is a site for terminal maturation of primitive erythroid cells. Blood 2010, 116, 3321–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Han, J.; Li, G.; Kwon, M.Y.; Jiang, J.; Emani, S.; Taglauer, E.S.; Park, J.A.; Choi, E.B.; Vodnala, M.; et al. Multipotency of mouse trophoblast stem cells. Stem cell research & therapy 2020, 11, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Serikov, V.; Hounshell, C.; Larkin, S.; Green, W.; Ikeda, H.; Walters, M.C.; Kuypers, F.A. Human term placenta as a source of hematopoietic cells. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, N.J.) 2009, 234, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czechowicz, A.; Palchaudhuri, R.; Scheck, A.; Hu, Y.; Hoggatt, J.; Saez, B.; Pang, W.W.; Mansour, M.K.; Tate, T.A.; Chan, Y.Y.; et al. Selective hematopoietic stem cell ablation using CD117-antibody-drug-conjugates enables safe and effective transplantation with immunity preservation. Nature communications 2019, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjos-Afonso, F.; Bonnet, D. Human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell hierarchy: How far are we with its delineation at the most primitive level? Blood 2023, 142, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Histological structure of chorionic villi in the human placenta (H&E staine, x200, scale bar 50 µm). A) The mesenchymal type of chorionic villi from first-trimester placentas (8th week of gestation), the villi are predominantly composed of mesenchymal connective tissue (marked with a star) and are encased by two distinct layers of trophoblastic cells (red arrow), no blood vessels are evident within the stroma; B) the intermediate type of chorionic villi from second-trimester placentas (23rd week of gestation), the stroma contains numerous stromal channels (indicated by a star) and blood vessels filled with erythrocytes (black arrow), these structures are surrounded by a single layer of trophoblastic cells (red arrow); C) terminal chorionic villi from third-trimester placentas (36th week of gestation), the stroma is densely vascularized, containing numerous blood vessels (black arrow), while the surface is covered by a continuous layer of syncytiotrophoblasts (red arrow).

Figure 1.

Histological structure of chorionic villi in the human placenta (H&E staine, x200, scale bar 50 µm). A) The mesenchymal type of chorionic villi from first-trimester placentas (8th week of gestation), the villi are predominantly composed of mesenchymal connective tissue (marked with a star) and are encased by two distinct layers of trophoblastic cells (red arrow), no blood vessels are evident within the stroma; B) the intermediate type of chorionic villi from second-trimester placentas (23rd week of gestation), the stroma contains numerous stromal channels (indicated by a star) and blood vessels filled with erythrocytes (black arrow), these structures are surrounded by a single layer of trophoblastic cells (red arrow); C) terminal chorionic villi from third-trimester placentas (36th week of gestation), the stroma is densely vascularized, containing numerous blood vessels (black arrow), while the surface is covered by a continuous layer of syncytiotrophoblasts (red arrow).

Figure 2.

CD34 Immunoreactivity in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi of human placentas from the first, second, and third trimesters (x630, scale bar 20 µm). A) Chorionic plate of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) are clustered within the lumen of blood vessels (black arrow), endothelial cells within the blood vessels of the chorionic plate exhibit strong CD34 immunoreactivity; B) chorionic villi of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), with highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) grouped in clusters within the lumen of blood vessels, C) chorionic villi of a second-trimester placenta (22nd week of gestation), highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) are located as individual cells in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow), endothelial cells also display strong CD34 immunoreactivity (red arrow); D) chorionic villi of a third-trimester placenta (36th week of gestation), highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) are present as individual cells in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow), while endothelial cells continue to exhibit strong CD34 immunoreactivity (red arrow).

Figure 2.

CD34 Immunoreactivity in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi of human placentas from the first, second, and third trimesters (x630, scale bar 20 µm). A) Chorionic plate of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) are clustered within the lumen of blood vessels (black arrow), endothelial cells within the blood vessels of the chorionic plate exhibit strong CD34 immunoreactivity; B) chorionic villi of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), with highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) grouped in clusters within the lumen of blood vessels, C) chorionic villi of a second-trimester placenta (22nd week of gestation), highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) are located as individual cells in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow), endothelial cells also display strong CD34 immunoreactivity (red arrow); D) chorionic villi of a third-trimester placenta (36th week of gestation), highly immunoreactive CD34 HSCs (+++) are present as individual cells in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow), while endothelial cells continue to exhibit strong CD34 immunoreactivity (red arrow).

Figure 3.

CD117 Immunoreactivity in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi of human placentas from the first, second, and third trimesters. A) The chorionic plate of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs (+++) are clustered within the lumen of blood vessels (black arrow), trophoblastic cells exhibit strong CD117 immunoreactivity (red arrow); B) the chorionic villi of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs (+++) completely fill the lumen of a blood vessel; C) the chorionic villi of a second-trimester placenta (22nd week of gestation), highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs (+++) are present as individual cells within the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow), trophoblastic cells also display strong CD117 immunoreactivity (red arrow); D) the chorionic villi of a third-trimester placenta (36th week of gestation), only trophoblastic cells demonstrate moderate CD117 immunoreactivity (++), indicated by the red arrow, while immunoreactive CD117 HSCs are absent.

Figure 3.

CD117 Immunoreactivity in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi of human placentas from the first, second, and third trimesters. A) The chorionic plate of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs (+++) are clustered within the lumen of blood vessels (black arrow), trophoblastic cells exhibit strong CD117 immunoreactivity (red arrow); B) the chorionic villi of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs (+++) completely fill the lumen of a blood vessel; C) the chorionic villi of a second-trimester placenta (22nd week of gestation), highly immunoreactive CD117 HSCs (+++) are present as individual cells within the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow), trophoblastic cells also display strong CD117 immunoreactivity (red arrow); D) the chorionic villi of a third-trimester placenta (36th week of gestation), only trophoblastic cells demonstrate moderate CD117 immunoreactivity (++), indicated by the red arrow, while immunoreactive CD117 HSCs are absent.

Figure 4.

CD41 Immunoreactivity in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi of human placentas from the first, second, and third trimesters. A) the chorionic plate of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD41 HSCs (+++) are observed as individual cells located in the mesenchymal connective tissue of the chorionic plate (black arrow); B) the chorionic villi of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), with highly immunoreactive CD41 HSCs (+++) observed as individual cells situated in the mesenchymal connective tissue; C) the chorionic villi of a second-trimester placenta (22nd week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD41 HSCs (+++) are located as individual cells in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow).

Figure 4.

CD41 Immunoreactivity in the chorionic plate and chorionic villi of human placentas from the first, second, and third trimesters. A) the chorionic plate of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD41 HSCs (+++) are observed as individual cells located in the mesenchymal connective tissue of the chorionic plate (black arrow); B) the chorionic villi of a first-trimester placenta (11th week of gestation), with highly immunoreactive CD41 HSCs (+++) observed as individual cells situated in the mesenchymal connective tissue; C) the chorionic villi of a second-trimester placenta (22nd week of gestation), where highly immunoreactive CD41 HSCs (+++) are located as individual cells in the mesenchyme of the chorionic villi (black arrow).

Table 1.

The number of samples included in the study, allocated to different groups based on trimesters of development and weeks of gestation.

Table 1.

The number of samples included in the study, allocated to different groups based on trimesters of development and weeks of gestation.

| Development Period |

Gestational Week |

No Placentas |

ΣNo |

| First Trimester |

7. |

2 |

10 |

| 8. |

2 |

| 9. |

3 |

| 10. |

1 |

| 11. |

2 |

| Second Trimester |

19. |

3 |

10 |

| 20. |

5 |

| 23. |

2 |

| Third Trimester |

28. |

1 |

10 |

| 35. |

1 |

| 36. |

5 |

| 37. |

3 |

Table 2.

The mean value and standard deviations of NA of CD34 immunoreactive HSCs in human placenta in three trimesters.

Table 2.

The mean value and standard deviations of NA of CD34 immunoreactive HSCs in human placenta in three trimesters.

| Development Period |

Mean |

SD |

P |

| First Trimester |

409.9 |

244.3 |

0.04* |

| Second Trimester |

462.5 |

174.8 |

| Third Trimester |

249.3 |

59.8 |

Table 3.

The mean value and standard deviations of NA of CD117 immunoreactive HSCs in human placenta in three trimesters.

Table 3.

The mean value and standard deviations of NA of CD117 immunoreactive HSCs in human placenta in three trimesters.

| Development Period |

Median |

IQR |

P |

| First Trimester |

222.2 |

118.2 |

0.18 |

| Second Trimester |

187.5 |

23.8 |

| Third trimester |

0 |

0 |

Table 4.

Differences in NA values among various types of HSCs during the first and second trimesters.

Table 4.

Differences in NA values among various types of HSCs during the first and second trimesters.

| |

First Trimester |

Second Trimester |

| HSCs |

Mean |

SD |

P |

Median |

IQR |

P |

| CD34 |

409.9 |

244.3 |

0.15 |

462.5 |

174.8 |

<0.001** |

| CD117 |

267.5 |

145.8 |

187.5 |

23.8 |

| CD41 |

- |

- |

45.8 |

6.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).