1. Introduction

In Latvia and globally, one of the enduring challenges in the medical field has been the development of various pathologies related to pregnancy, maternal health, and newborns. Pregnancy is a unique immunological state where the maternal immune system exhibits tolerance towards the fetus. While immune suppression is critical for a successful pregnancy, maintaining immunological balance and appropriate cytokine levels is essential for both maternal and fetal health. Any imbalance in this delicate system can lead to pregnancy complications or loss [

1].

Regrettably, the rates of successful pregnancies and births are declining, with multiple possible causes and explanations. This has raised questions about how maternal health and placental function might influence child health and whether there is a link between these factors. The placenta serves as a vital connection between the fetus and the uterine wall, acting as a specialized, temporary organ essential for fetal development [

2]. Like other organs, the placenta undergoes vulnerable periods during which pathological changes, such as inflammation, are common. This highlights the roles of various cytokines: pro-inflammatory, regulatory, and anti-inflammatory within the placenta.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines primarily include interleukin-1α (IL-1α), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-7 (IL-7), and interleukin-8 (IL-8), while anti-inflammatory cytokines include interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-10 (IL-10). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is considered a regulatory cytokine.

IL-1 is a potent, multifunctional peptide that regulates immune responses and is produced by cells such as monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. There are two IL-1 forms, IL-1α and IL-1β, which are distinct peptides encoded by separate genes yet share similar biological activities [

3]. IL-1β is elevated in the plasma of preeclamptic women, while IL-1α remains largely undetected in maternal circulation. Both IL-1α and IL-1β bind to IL-1 receptor 1 (IL-1R1), complexing with IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RacP) to trigger inflammatory signaling [

4].

IL-2, a glycoprotein, is crucial for T-cell mediated immunity, produced by T-lymphocytes upon antigen or mitogen stimulation, necessary for the proliferation of activated T cells. Women with spontaneous abortions show higher levels of IL-2 receptor-positive cells than those with normal pregnancies, indicating that increased macrophage activity might enhance IL-1 production and IL-2 receptor expression [

5]. Some studies suggest IL-2 may play a role in preeclampsia as it has been detected in decidual cells of women with preeclampsia, unlike in normal pregnancies [

6].

IL-4, another glycoprotein, acts as an immuno-modulator, promoting humoral immunity while downregulating cellular immune responses. In non-pregnant tissues, IL-4 suppresses inflammatory processes, however, its role in intrauterine tissues remains less clear. IL-4 has been found in cytotrophoblasts, decidua, and both maternal and fetal endothelial cells, and it stimulates pro-inflammatory mediators in human amnion cells, potentially linking it to conditions like preterm labor and preeclampsia [

7].

IL-6, a powerful mediator, is produced by human trophoblasts and various immune cells. It plays roles in immune response regulation, hematopoiesis, and inflammation, and affects vascular wall functions, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production, and TNF-receptor shedding [

8]. IL-6 and TNF-α increase vascular permeability and induce apoptosis in trophoblastic cells, heightening inflammatory responses in maternal tissues and possibly contributing to preeclampsia [

9]. While IL-6 levels rise during pregnancy, research is limited on how IL-6 changes over the course of placental development.

IL-7, a cytokine essential for T-cell maturation, is known for its role in pro-inflammatory processes, although its specific role in placentation and early pregnancy remains less understood. IL-7 helps regulate Th-17 cell proliferation, and recent data indicate higher Th17 cell levels in cases of spontaneous abortion and preeclampsia, suggesting their influence in inflammatory responses at embryonic implantation [

10].

IL-8, a chemokine that attracts and activates neutrophils, is produced by various cells, including fibroblasts, macrophages, and uterine tissues. Its presence in uterine tissues, such as the placenta and cervix, hints at its involvement in labor initiation [

11].

IL-10, initially named cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (CSIF), suppresses the activity of inflammatory T-helper 1 cells. Though initially identified as a Th-2 product, IL-10 is now known to be produced by a wide range of cell types. Studies have linked disruptions in IL-10 balance to vascular system dysfunction and preeclampsia [

12,

13].

While current data on cytokines' roles in placental physiology and pathology provide valuable insights, further research is needed. Although some functions of various cytokines have been elucidated in relation to placental disease, little is known about cytokine fluctuations during different stages of placental development. This study therefore aims to explore the expression and distribution of pro-inflammatory, regulatory, and anti-inflammatory cytokines at various stages of placental maturation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

We performed a cross-sectional descriptive study of selected cases. We used the placental material of 15 eligible participants from pregnant women at three gestational ages - the 28th, 31st and 40th week of pregnancy. The material was obtained from the archive of the Institute of Anatomy and Anthropology of Riga Stradins University, earlier collected in the Riga Maternity Hospital (from 2005-2010). All patients provided written informed consent form for participating in the study and allowing the publication of study data. This consent form was given by pregnant women after a full explanation of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Riga Stradins University (12 March 2003).

2.2. Characteristics of Selected Patients

Fifteen pregnant women were taking part in the study, aged between 20 and 39 years old. Six out of fifteen pregnant women had their first pregnancy (Graviditas), three patients had their second pregnancy, two patients had their third pregnancy, three patients had their fourth pregnancy, and one patient had her sixth pregnancy. Ten out of fifteen women had their first labor (Partus), for four women it was the second labor and for one woman it was already the third labor. Participants and their placental samples were divided into groups, based on categories of preterm birth (a week of gestation at the delivery), according to World Health Organization [

14]:

Full-term infants – GA between 37 weeks and 41 week and 6 days;

Late preterm infants – GA between 34 weeks and 36 weeks and 6 days;

Moderate preterm infants – GA between 32 weeks and 33 weeks and 6 days;

Very preterm infants – GA < 32 weeks;

Extremely preterm infants – GA < 28 weeks.

Abbreviations: GA – gestational age.

Based on the classification mentioned above, three groups were performed: a study group of 5 cases with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), a study group of 5 cases with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week) and a study group of 5 cases with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week) with various outcomes, however, a common feature for all 15 cases was a distress acuta.

All the detailed information about the pregnant women and their delivery problems is displayed in the

Table 1.

2.3. Sample Collection

After the labor, study materials were immediately taken from the fifteen chosen maternal placentas through all the layers of the placental tissues from three places - central near the umbilical cord attachment and two peripheral ones. The cut-out material did not exceed 2,2 cm in diameter and 2,2 mm in thickness. The fixation was performed to strengthen and stabilise the structures. The duration of the tissue fixation in 10% buffered formalin is 2 hours at room temperature and 2-4 hours in the thermostat at 39-41 C degrees. The fixing compound used by our laboratory was the Stefanini's solution - formaldehyde, buffer and picric acid, followed by the washing with thyrode. Right after materials were taken to the Institute of Anatomy and Anthropology at Riga Stradins University to continue the processing.

2.4. Routine Staining

After the fixation, the material dehydration treatment was performed - a tissue dewatering process using ethanol at various concentrations (70-96), followed by a tissue sample infiltration with paraffin. The insertion of the tissue samples into paraffin was performed by a special technology and the amount of paraffin was regulated by a dispenser. Further, tissues were cut with a Leica microtome. The cuts were 3 to 5 mkm thick and were proceeded for the deparafinization with the paraffin solvent xylene (5-15 minutes) and the rehydration with ethanol (96-70) for 3-3 minutes. The staining with hematoxylin took 1-10 minutes and the staining with eosin 30 seconds - 1 minute. This was followed by a carboxylic acid - xylene - clarification for 1-2 minutes (xylene 1:3). The staining was completed by covering the samples with the coverslip.

2.5. Immunohistochemical (IHC) Analysis

We used standard streptavidin and biotin immunostaining methods to preparate the placental tissue samples for the IHC analysis [

15]. Detection of seven different interleukins was performed:

IL-1 α (orb308737, polyclonal, working dilution 1:100, Biorbyt LTD, Cambridge, UK);

IL-2 (ab92381, monoclonal, working dilution 1:250, Abcam, Cambridge, UK);

IL-4 (orb10908, polyclonal, working dilution 1:100, Biorbyt LTD, Cambridge, UK);

IL-6 (ab216492, polyclonal, working dilution 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK);

IL-7 (orb13506, polyclonal, working dilution 1:100, Biorbyt LTD, Cambridge, UK);

IL-8 (orb39299, polyclonal, working dilution 1:100, Biorbyt LTD, Cambridge, UK);

IL-10 (ab134742, monoclonal, working dilution 1:50, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

An antibody diluent (code-938B-05, Cell MarqueTM, Rocklin, CA, USA) was used to dilute the antibodies for the needed immunostaining concentration. For the further actions HiDef Detection™ HRP Polymer System was used. Tissue samples were cut approximately for 3 microns and were completely dried. Deparaffinization and rehydration of the tissue sections was perfored, followed by the application of the primary antibody according to manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Next, sections were rinsed with the IHC wash buffer and the application of the HiDef Detection™ Amplifier (code 954D-31, Cell MarqueTM, Rocklin, CA, USA) for 10 minutes at room temperature was performed and then rinsed again with the IHC wash buffer. This was followed by applying the HiDef DetectionTM HRP Polymer Detector (code-954D-32, Cell MarqueTM, Rocklin, CA, USA) for 10 minutes at room temperature and rinsing with IHC wash buffer. Lastly, the application of the HRP-compatible chromogen according to manufacturer’s recommendations was performed and the sections were rinsed with distilled or deionized water. The samples were counterstained and coversliped and ready for the further analysis.

2.6. Assessment of Local Tissue Defense Factor Quantity

The samples were analyzed by two independent morphologists. We used the semi-quantitative counting method and light microscopy method to get the relative number of IL-1α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8 and IL-10 positive structures of the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages and endothelium in the placental tissue sample slides. We used the identifiers summarized in the

Table 2 to evaluate the positively stained structures from the visual field [

16,

17].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis for the study groups was performed after using the semi-quantitative counting method to get the relative quantity data of the studied cytokines. The IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software version 29.0. (Armonk, NY, IBM Corp., USA) was used to process and analyze the statistical data. To describe each parameter, median value was used.

To vertically compare each interleukin positivity in the structures of the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages and endothelium in placentas of different ages, the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test was performed and analyzed, since the semi-quantitative counting method provided us with the ordinal data. A p-value < 0.05 was noted and analyzed as statistically significant for the statistical assessment of the tests and further processing of the results.

The nonparametric statistically significant correlations separately between each interleukin positivity and separately between different structures (the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages and endothelium), as well as between the structures of each placenta and each interleukin, were obtained using the Spearman’s rank correlation and correlation coefficient [

18]. The Spearman’s rho provided us with the information about the connection between different cytokines, different placental structures and how changes in one interleukin positivity affect or relate to another across the four structures mentioned above.

To evaluate the strength of the correlation, Spearman’s rho (rs) values were categorized as follows: rs = 0.00–0.24 indicated a very weak correlation, rs = 0.25–0.49 represented a weak correlation, rs = 0.50–0.74 signified a strong correlation, and rs = 0.75–1.00 indicated a very strong correlation.

3. Results

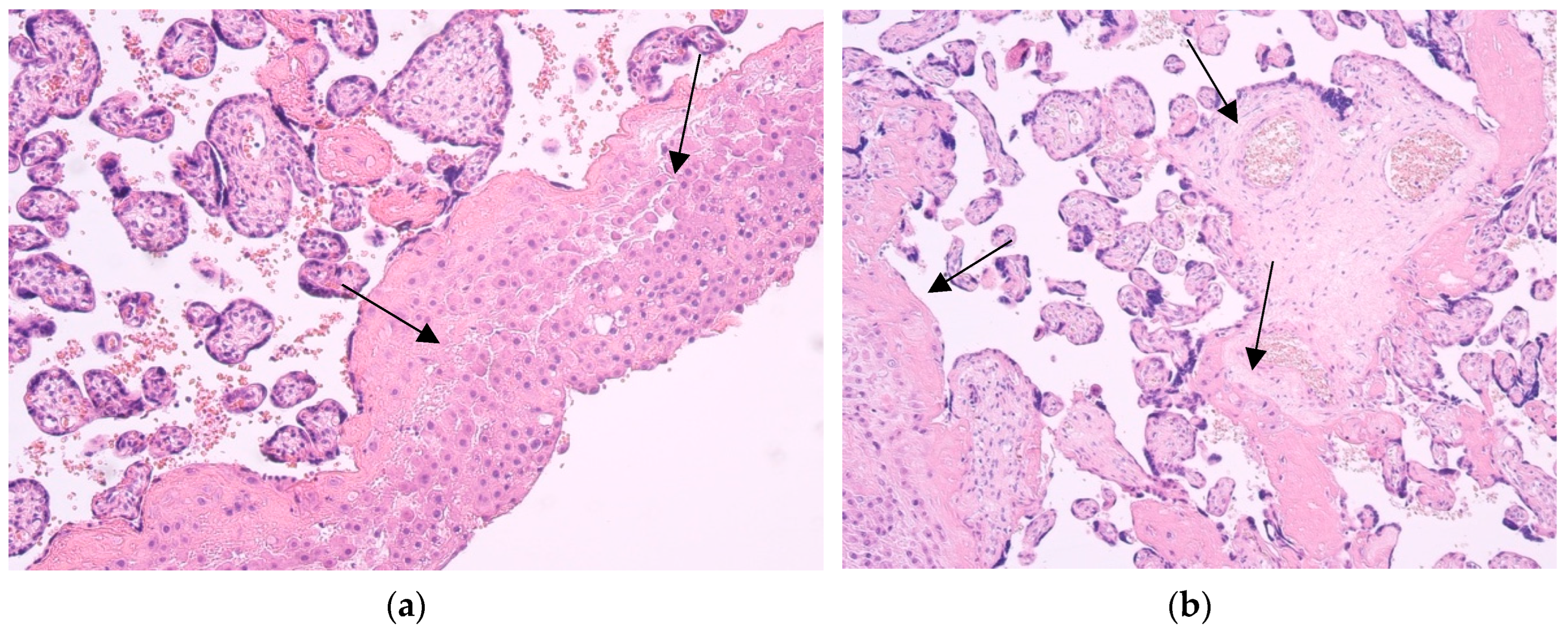

3.1. Routine Staining

The samples showed practically similar changes and features of placental structures - a lot of fibrinoid deposits and huge infiltration of the macrophages, also known as Hofbauer cells. All placentas corresponded to transitional stages and showed signs of aging. In some cases, lymphocyte infiltration and obliterated blood vessels were observed (

Figure 1).

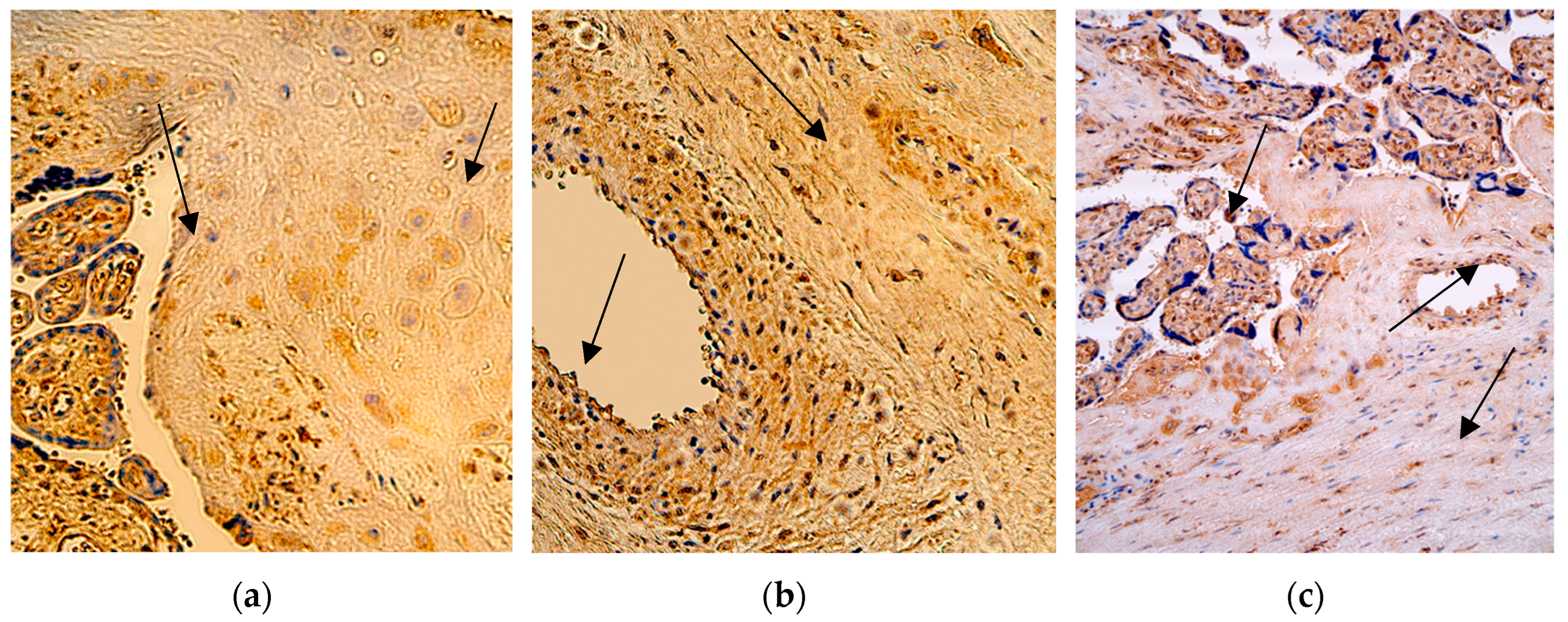

3.2. IL-1α IMH

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-1α positive cells in the cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm was numerous (+++), with fluctuation from moderate to abundant in the cytotrophoblast, and from moderate to numerous in the mesoderm. The number of positive macrophages was also numerous (+++), but with fluctuation from none to abundant. The median quantity of the IL-1α positive structures in the endothelium was moderate (++), with fluctuation from few to numerous positive structures.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-1α positive macrophages and cells in the extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium was numerous (+++), with small fluctuations from moderate to abundant, but for the cytotrophoblast it was moderate (++), with the same fluctuations from moderate to abundant.

In the last group with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-1α positive structures in the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium was numerous (+++) like in two other groups, with minimal fluctuations, but the median value of the macrophages was only few positive ones in the visual field (+), with fluctuation from none in one case to numerous positive cells in other cases (

Figure 2 and

Table 3).

A comparison of the IL-1α positive cytotrophoblast (p = 0,721), extraembryonic mesoderm (p = 0,534), macrophages (p = 0,141) and endothelium (p = 0,393) across all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated no statistically significant differences between the different time placentas.

3.3. IL-2 IMH

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-2 positive macrophages and cells in the extraembryonic mesoderm, endothelium and cytotrophoblast was numerous (+++), with fluctuations from occasional to numerous in the extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium, from none to numerous macrophages and from moderate to abundant in the cytotrophoblast.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-2 positive structures in the extraembryonic mesoderm, cytotrophoblast and endothelium was lower than in the first group – it was moderate (++), with fluctuation from few to numerous in the cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm, and from occasional to numerous in the endothelium. The number of positive macrophages was the highest – it was abundant (++++), with fluctuations from few positive ones.

In the last group with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-2 positive cells in the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and positive for factor macrophages was the lowest (+) in all three groups, with fluctuations from only occasional positive structures to even abundant in one case of five, but in the endothelium the median positive cells were even lower – only occasional (0/+), with small fluctuation in one case to moderate numbers (++) (

Figure 3 and

Table 3).

A comparison of the IL-2 positive extraembryonic mesoderm (p = 0,074), macrophages (p = 0,208) and endothelium cells (p = 0,100) across all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated no statistically significant differences between the different time placentas, but a statistically significant difference in the structures of the positive cytotrophoblast (p = 0,014) between 28 weeks and 40 weeks of gestation (

Table 4).

3.4. IL-7 IMH

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-7 positive extraembryonic mesoderm, cytotrophoblast and endothelium cells was occasional (0/+), but the number of positive macrophages was higher – moderate (++), with fluctuation from occasional to numerous.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-7 positive structures in the extraembryonic mesoderm, cytotrophoblast and IL-7 positive macrophages was higher than in the extremely preterm group of infants, - moderate (++), with fluctuation from none to numerous, but in the endothelium it was only few positive cells, without notable fluctuations.

In the full-term group of infants (the 40th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-7 positive cells in the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium was similar - 0/+, defined as occasional occurrence with minimal fluctuations, but the median value of macrophages was a little bit higher and showed few positive cells in the visual field, with fluctuation from occasional (0/+) to numerous (+++) (

Figure 4 and

Table 5).

A comparison of the IL-7 positive cytotrophoblast (p = 0,459), extraembryonic mesoderm (p = 0,060), macrophages (p = 0,730) and endothelium cells (p = 0,593) across all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated no statistically significant differences between the different time placentas.

3.5. IL-8 IMH

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-8 positive structures in the samples varied from few ones (+) in the endothelium to numerous (+++) in the cytotrophoblast, with fluctuation from few to numerous, but in the extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium – from few to moderate (++), and demonstrated from occasional to numerous macrophages.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-8 positive cells in the extraembryonic mesoderm was the highest from all analysed structures, and reached numerous numbers (+++), with fluctuation from few to abundant, on the other hand - the median quantity of the positive macrophages, endothelium and cytotrophoblastic cells was moderate (++), with fluctuations from moderate to numerous in the cytotrophoblast, from occasional to numerous macrophages, and from few to numerous in the placental endothelium.

In the last group with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-8 positive structures in the cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm was moderate (++), with minimal fluctuations, and in the endothelium and for macrophages it was lower – only few positive cells in the visual field (+), with fluctuation from none (0) to numerous (+++) (

Figure 5 and

Table 5).

A comparison of the IL-8 positive cytotrophoblast (p = 0,383), extraembryonic mesoderm (p = 0,142), macrophages (p = 0,732), and endothelium cells (p = 0,378) between the all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated no statistically significant differences between the different time placentas.

3.6. IL-4 IMH

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast, macrophages and endothelium cells was 0 or none, with fluctuation to occasional occurrence (0/+). In the extraembryonic mesoderm the median value reached the occasional occurrence of positive cells, with fluctuation from none.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-4 positive structures also was none (0) in the cytotrophoblast and endothelium, with small fluctuations, but positive macrophages and extraembryonic mesodermal cells reached the occasional occurrence (0/+), with the same fluctuations in the cytotrophoblast and endothelium.

In the last group with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-4 positive cells of the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium was also of occasional occurrence (0/+) like in two other groups, with fluctuation from none (0) to few positive structures (+), and for macrophages the median value reached few positive cells in the visual field (+) (

Figure 6 and

Table 6).

A comparison of the IL-4 positive endothelium cells (

p = 0,024) and macrophages (

p = 0,027) across all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated a statistically significant difference between 40 weeks and 28 weeks of delivery, and also no statistically significant differences between the positive structures of the cytotrophoblast (

p = 0,131) and extraembryonic mesoderm (

p = 0,158) (

Table 7).

3.7. IL-10 IMH

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), IL-10 was not observed at all.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-10 positive cells also was none (0) in the cytotrophoblast and endothelium, with small fluctuation to occasional occurrence, but the positive macrophages and extraembryonic mesodermal cells reached the occasional occurrence (0/+), with the same fluctuations in the cytotrophoblast and endothelium.

In the last group with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week), there was no positive cells of the IL-10 in the cytotrophoblast, endothelium, and not any positive macrophage was detected, but in the extraembryonic mesoderm the median value reached occasional occurrence (0/+), with minimal fluctuation from none (0) in two cases (

Figure 7 and

Table 6).

A comparison of the IL-10 positive cytotrophoblast (p = 0,280), extraembryonic mesoderm (p = 0,097), macrophages (p = 0,131) and endothelium cells (p = 0,280) across all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated no statistically significant differences.

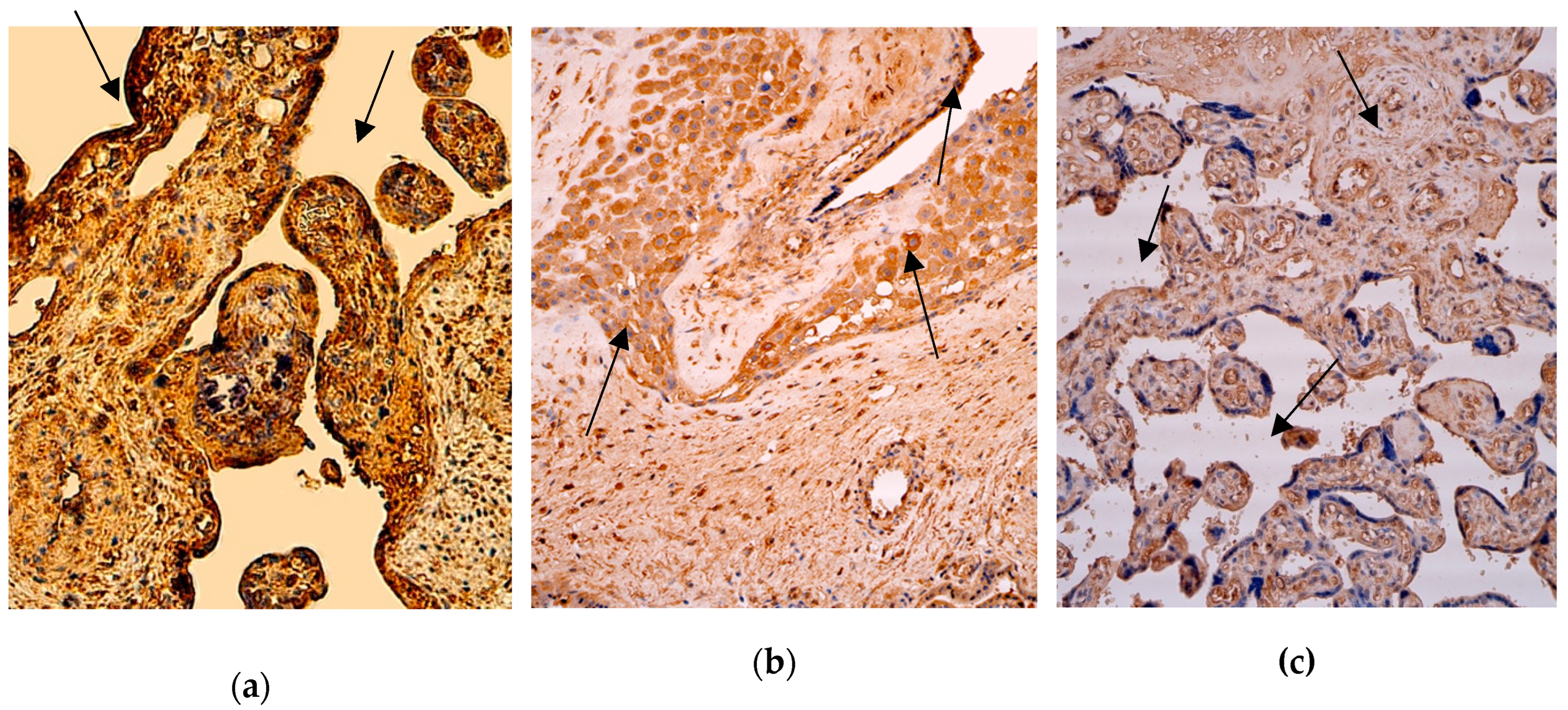

3.8. IL-6 IMH

Commonly, the median values of the IL-6 in all three groups reached higher numbers than for the other factors.

In the group with extremely preterm infants (the 28th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-6 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium cells was few (+), with fluctuations from none to moderate in the endothelium, from occasional to few in the extraembryonic mesoderm, and from occasional to numerous in the cytotrophoblast. The number of macrophages was moderate (++), with fluctuation from occasional to moderate.

In the group with very preterm infants (the 31st delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-6 positive extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium cells was few, with fluctuation from occasional to moderate. On the other hand - the number of positive macrophages and cytotrophoblastic cells was moderate (++), with fluctuations from occasional to moderate for the cytotrophoblast, and from few to abundant (++++) for macrophages in one case.

In the last group with full-term infants (the 40th delivery week), the median quantity of the IL-6 positive cells varied from occasional (0/+) in the cytotrophoblast to moderate (++) macrophages, with fluctuation from none (0) to abundant (++++). The median values in the extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium were few positive ones (++), with fluctuation from occasional to moderate (

Figure 8 and

Table 6).

A comparison of the IL-6 positive cytotrophoblast (p = 0,423), extraembryonic mesoderm (p = 0,534), macrophages (p = 0,732), and endothelium cells (p = 0,453) across all three patient groups with different delivery weeks using the Independent-Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test illustrated no statistically significant differences.

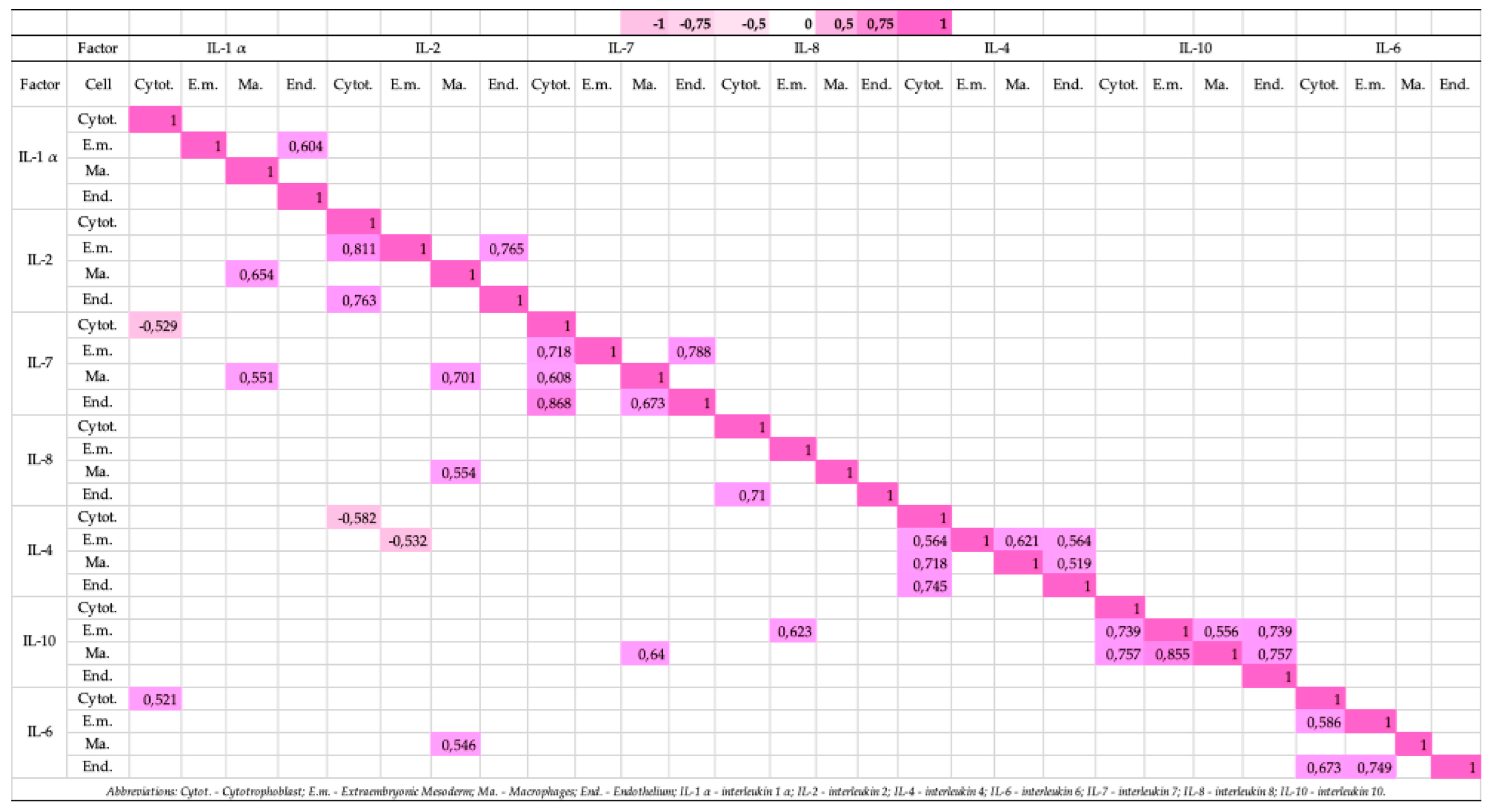

3.9. Correlations of the Studied Cytokines in the Cytotrophoblast, Extraembryonic Mesoderm, Macrophages and Endothelium Structures of Placental Distress Acuta Affected Patient Groups with Different Delivery Weeks (Figure 9)

Strong positive correlations were detected:

between the IL-6 and IL-1 α positive cytotrophoblast (rs = 0.521, p = 0.046);

between the IL-10 and IL-8 positive extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.623, p = 0.013);

between the IL-2 and IL-1 α (rs = 0.654, p = 0.008), the IL-7 and IL-1 α (rs = 0.551, p = 0.033), the IL-7 and IL-2 (rs = 0.701, p = 0.004), the IL-8 and IL-2 (rs = 0.554, p = 0.032), the IL-6 and IL-2 (rs = 0.546, p = 0.035), and the IL-10 and IL-7 positive macrophages (rs = 0.640, p = 0.010);

between the IL-1 α positive endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.604, p = 0.017);

between the IL-7 positive cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.718, p = 0.003), and the cytotrophoblast and macrophages (rs = 0.608, p = 0.016), and the endothelium and macrophages (rs = 0.673, p = 0.006);

between the IL-8 positive cytotrophoblast and endothelium (rs = 0.710, p = 0.003);

between the IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.564, p = 0.029), the cytotrophoblast and macrophages (rs = 0.718, p = 0.003), the endothelium and cytotrophoblast (rs = 0.745, p = 0.001), the macrophages and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.621, p = 0.013), the endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.564, p = 0.029), and the endothelium and macrophages (rs = 0.519, p = 0.047);

between the IL-10 positive cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.739, p = 0.002), the endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm (rs = 0.739, p = 0.002), the macrophages and extraembryonic mesoderm (rs = 0.556, p = 0.031);

between the IL-6 positive cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.586, p = 0.022), the cytotrophoblast and endothelium (rs = 0.673, p = 0.006), and the endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm (rs = 0.749, p = 0.001).

Strong negative correlations were detected:

between the IL-7 and IL-1 α positive cytotrophoblast (rs = -0.529, p = 0.043);

between the IL-2 and IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast (rs = -0.582, p = 0.023), and positive extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = -0.532, p = 0.041).

Very strong positive correlations were observed:

between the IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.811, p = 0.000), the cytotrophoblast and endothelium (rs = 0.763, p = 0.001), and the endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.765, p = 0.001);

between the IL-7 positive endothelium and cytotrophoblast (rs = 0.868, p = 0.000), the endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.788, p = 0.000);

between the IL-10 positive cytotrophoblast and macrophages (rs = 0.757, p = 0.001), the macrophages and extraembryonic mesoderm cells (rs = 0.855, p = 0.000), and the endothelium and macrophages (rs = 0.757, p = 0.001).

Figure 9.

Correlation Matrix of Significant Cytokine Relationships.

Figure 9.

Correlation Matrix of Significant Cytokine Relationships.

4. Discussion

Notable increase of the pro-inflammatory IL-1α, IL-2 and IL-8 positive structures was noted in the 28 weeks old patient samples, with the decrease in the 40 weeks old placentas. All placental structures of patient samples presented significant decrease or even no activity of the anti-inflammatory IL-4 and IL-10 across different delivery weeks.

In our study, IL-1α demonstrated a significant and predominant increase within the endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm of placental samples across all three delivery weeks. This finding suggests that IL-1α likely plays a central role in driving inflammation in placentas affected by

distress acuta, irrespective of gestational age. By binding to the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R), IL-1α not only propagates its own inflammatory signaling but also stimulates the production of additional inflammatory mediators. Previous studies highlight that IL-1 was the first cytokine identified as a contributor to preterm labor associated with inflammation [

19]. Supporting this notion, evidence shows that IL-1α is produced by the human decidua in response to bacterial stimuli and can induce prostaglandin production in the amnion and decidua. Elevated IL-1α concentrations and activity have also been observed in the amniotic fluid of women experiencing preterm labor and infections [

19,

20,

21]. These observations align with our findings, underscoring the pivotal role of IL-1α in placental inflammation in

distress acuta. In comparing preterm delivery groups, it is important to note that both forms of IL-1, α and β, have the potential to stimulate myometrial contractions [

22]. IL-1α, known for its upregulation by diverse inflammatory stimuli, remains bioactive without requiring proteolytic processing [

4]. Earlier reports indicate that exposing human placental explants to hypoxic conditions results in increased production of tumor necrosis factor alfa (TNFα) and IL-1α [

23], suggesting that localized ischemia or hypoxia stemming from inadequate uterine vascular remodeling can intensify placental cytokine release. Consequently, sterile or infectious insults leading to cell damage release bioactive IL-1α, which signals through IL-1R to activate inflammatory pathways. IL-1R, expressed across a variety of cell types, triggers downstream activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). This activation promotes pro-inflammatory mediators such as cyclooxygenase type-2 (COX-2), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which in turn amplify the inflammatory cascade initiated by IL-1α release [

24]. The interaction and colocalization of IL-1 and IL-1R in normal and inflamed placentas suggest a delicate balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators, influencing both parturition and acute inflammation pathogenesis. Furthermore, IL-1α has been implicated in human parturition mechanisms during infection, with its production by the trophoblast observed during early pregnancy and at term, showing a gradual decline over gestation [

25].

In our study, the

number of IL-2 positive structures gradually decreased from the 28th delivery week to the 40th delivery week, indicating that placentas from earlier delivery weeks exhibit heightened susceptibility to this cytokine. An exception was noted in the 31st week, with an increase in IL-2-positive macrophages. We speculate that Hofbauer cells, due to their phagocytic and secretory functions and IL-2 receptor sensitivity, may significantly contribute to inflammation in

distress acuta placentas. Interestingly, contrary to our findings, some studies report that IL-2 does not enhance interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) secretion by cultured decidual macrophages, though it synergistically stimulates IFN-γ release in decidual large granular lymphocytes [

26]. Other research supports the presence of molecules sharing antigenic properties with IL-2 in the human trophoblast [

27], suggesting a regulatory role for IL-2 in local immune responses and inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface [

28]. Higher IL-2 concentrations have been observed in the second and third trimesters, as well as in cases of preterm labor without chorioamnionitis, supporting our results [

29]. Additionally, IL-2's role in promoting T lymphocyte proliferation may enhance the placenta's immunomodulatory efficiency. Some authors have detected IL-2 receptors and IL-2 on extraembryonic membranes using recombinant IL-2, with findings indicating cross-reactivity in placentas post-spontaneous abortion [

30]. Finally, IL-2 is recognized as a potent stimulator of decidual natural killer (NK) cell proliferation, implicating its involvement in intrauterine inflammation progression [

31]. However, its role in vivo remains ambiguous, as IL-2 has not been identified during implantation or within the non-pregnant endometrium [

32].

In our study, the number of IL-7 positive structures was lower compared to other pro-inflammatory cytokines analyzed. Interestingly, across all three gestational periods, IL-7 expression was primarily localized to Hofbauer cells. Human peripheral blood monocytes stimulated by IL-7 are known to produce inflammatory mediators such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 beta (MIP-1β), highlighting its role in inflammatory immune responses [

33]. However, this role is not as evident in the placenta. Previous research investigating decidual IL-7 expression in cases of spontaneous and recurrent spontaneous abortions found IL-7-positive cells in the decidua of recurrent spontaneous abortion patients, while the specific trophoblast marker, human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G), did not indicate IL-7 expression [

34]. These findings suggest that IL-7 may not be a key cytokine in driving

distress acuta syndrome. Conversely, other studies have observed stronger IL-7 immunohistochemical staining in extravillous trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts of placentas from patients with gestational diabetes mellitus compared to healthy placentas. This increased expression may support low-grade inflammation and alter placental differentiation processes [

35]. Despite these observations, in our study, IL-7 expression was consistent across groups and did not exhibit features of inflammation or cytokine imbalance. IL-7 has also been reported to enhance human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) expression, aiding trophoblast invasion [

36]. Furthermore, reduced IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) expression in endometrial stromal cells of recurrent spontaneous abortion patients has been linked to disruptions in IL-7/IL-7R signaling, which could impair trophoblast invasion [

37]. These findings may explain the relatively low activity of IL-7 observed in our cases.

In our study, the number of IL-8 positive structures did not increase with aging of the placenta. This could be attributed to the heightened sensitivity of younger placentas to internal and external inflammatory triggers, even though in

distress acuta these triggers persist regardless of gestational age. It is also important to consider that deliveries at 28 weeks are categorized as premature, indicating the possible involvement of risk factors such as infections, uterine anomalies, gynecological and obstetric history, or stress. The high activity of IL-8 observed in both preterm and term placental samples may be linked to its role in host defense mechanisms. IL-8 induces rapid neutrophil recruitment and activation, enhancing responses to bacterial infections and inflammation. Placental and decidual cells are known to increase IL-8 secretion in response to IL-1 and TNF-α [

38]. Notably, trophoblast cells, identified as IL-8 producers, showed the highest positive structure numbers in the cytotrophoblast in our study. This aligns with prior research indicating that IL-8 production is constitutive in trophoblasts and macrophage-like cells, peaking in the second trimester and term placentas [

39]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that term placentas produce IL-8, primarily localized around perivascular areas of the villi, with increased production following spontaneous labor [

40]. This supports the hypothesis that IL-8 contributes to the initiation of parturition by recruiting and activating neutrophils at the placental site.

In our study, the activity of IL-4 was mostly absent in preterm placental structures, with only a few exceptions. This could be attributed to the dominance of pro-inflammatory cytokines, as previously mentioned, which may suppress the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-4 during the onset of inflammation. Conversely, term placental samples showed higher levels of IL-4 positivity. These findings align with prior studies demonstrating increased IL-4 and IL-10 production in normal pregnancies, while reduced levels of these cytokines were characteristic of pathological pregnancies, distinguishing them from healthy ones [

41]. Additionally, the research has associated low IL-4 levels with elevated natural killer (NK) cell activity in women with recurrent spontaneous abortions and preeclampsia [

42,

43]. In IL-4-deficient mice, researchers have noted altered splenic immune cell subsets, heightened pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, placental inflammation, hypertension, and endothelial dysfunction [

44]. Notably, earlier studies identified IL-4 activity in the endothelium, macrophages, and cytotrophoblastic cells of the placenta [

45,

46], suggesting that IL-4 exhibits more pronounced activity in specific cell types and functions as a protective agent. However, research analyzing cytokine and growth factor dynamics in pregnancies with and without preeclampsia reported no significant differences in IL-4 levels between the groups [

47], indicating that this cytokine may not play a pivotal role in certain pathological processes.

In our study, the number of IL-10 positive structures was immensely decreased, and the activity was observed very rarely in the visual fields of both preterm and term placental samples, and in the term placentae even greater. Interestingly, higher fluctuations in IL-10 activity were noted in the extraembryonic mesoderm and Hofbauer cells. Previous research has reported reduced IL-10 levels in placental tissues associated with chorioamnionitis-related preterm labor and term labor, compared to second-trimester placental samples obtained from elective terminations [

48]. These findings corroborate our observations of decreased IL-10 activity in cases linked to inflammatory processes. Existing data further shows that IL-10 levels in first- and second-trimester placental tissues are significantly higher compared to third-trimester tissues, suggesting an intrinsic downregulation of IL-10 at term as part of the preparation for labor, which is accompanied by an inflammatory milieu [

49]. This observation is consistent with our findings. Additionally, studies have highlighted the critical role of IL-10 at the maternal-fetal interface, as placental and decidual tissue from first trimester missed abortions demonstrated reduced IL-10 production compared to control tissues from elective terminations [

50]. Interestingly, increased IL-10 expression has been noted in term placentas of women with preeclampsia [

51], reflecting its divergent activity in different pathological conditions. IL-10 production is significantly reduced in term placentas not in labor compared to those from the first and second trimesters, indicating that its downregulation is a physiological event that promotes an inflammatory environment necessary for labor onset [

52]. This decreased expression can be interpreted as a normal physiological finding. Furthermore, IL-10 deficiency in the immune compartment is expected to compromise placental development. Numerous studies have linked IL-10 deficiency to adverse pregnancy outcomes, as placental explants from women experiencing preterm labor showed poor IL-10 production compared to controls from normal pregnancies [

48]. These findings may also be applicable to our cases of

distress acuta syndrome and spontaneous delivery.

In our study, the activity of IL-6 stayed equal in the extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages and endothelium cells across all three gestational weeks with some individual variations. This finding underscores the significance of IL-6 in placental function across different gestational ages. Other studies similarly highlight its importance, as IL-6 concentrations are known to rise in human amniotic fluid, vaginal fluid, cervical fluid, maternal circulation, and fetal tissues in response to feto-placental infections [

53]. Clinical and experimental evidence strongly supports the activation and upregulation of IL-6 signaling in multiple placental compartments during intrauterine inflammation. Notably, amnion mesenchymal cells and decidua stromal cells serve as primary sources of IL-6 during such inflammation, contributing to preterm labor [

54]. Pearson correlation analysis has also shown a positive correlation between IL-6 expression levels and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a common complication in premature infants [

52]. Interestingly, some studies suggest that chorioamnionitis does not significantly impact the immunohistochemical expression of IL-6 in the placental membranes of women with late preterm deliveries, regardless of clinical presentation [

55]. This reflects the complexity of IL-6’s role, as it can function both as a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine. This dual functionality depends on the type of receptor it activates (soluble or transmembrane) and the associated signaling pathways [

56]. IL-6 is naturally produced by human trophoblasts and serves as a potent mediator of various functions, including vascular wall regulation, stimulation of trophoblast growth, invasion, and differentiation, as well as the modulation of placental hormone production and involvement in angiogenesis [

8]. These roles highlight IL-6’s importance in maintaining placental function and pregnancy, suggesting that its response may not significantly vary across acute, sub-acute, or chronic pathological conditions.

Both positive and negative correlations were identified and described earlier across studied cytokines in different placental structures, including cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages, and endothelium. It is noteworthy to note that correlations do not necessarily imply causation, so the results of our study should not be interpreted as automatically establishing a meaningful relationship between these cytokines. Nevertheless, we can suggest the potential and possible synergistic and antagonistic interactions.

In the cytotrophoblast:

IL-7 and IL-1α. A strong negative correlation suggests that higher IL-7 levels are associated with lower IL-1α levels and vice versa, that indicates a possible regulatory interaction where pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines balance each other;

IL-2 and IL-4. A strong negative correlation also suggests a balancing mechanism between IL-2 and IL-4, which may imply a reduction in anti-inflammatory response as IL-2 increases.

In the extraembryonic mesoderm:

- 3.

IL-6 and IL-1α. A strong positive correlation indicates that these pro-inflammatory cytokines increase simultaneously, suggesting potential inflammation activation in this structure;

- 4.

IL-2 and IL-4. A strong negative correlation again implies a balancing mechanism between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines;

- 5.

IL-10 and IL-8. A strong positive correlation suggests concurrent increases of these cytokines, possibly as a response to limit inflammation, where IL-10 might counterbalance the inflammatory effects of IL-8.

In macrophages:

- 6.

IL-2 and IL-1α. A strong positive correlation suggests synergy between these pro-inflammatory cytokines, potentially promoting a more active immune response;

- 7.

IL-7 and IL-1α. A strong positive correlation indicates simultaneous expression of both inflammatory regulators;

- 8.

IL-7 and IL-2. A strong positive correlation suggests joint action, possibly activating cell regeneration and immune response;

- 9.

IL-8 and IL-2, IL-6 and IL-2, IL-10 and IL-7. These strong positive correlations indicate a complex cytokine interaction likely connected to active anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory responses within macrophages.

In the endothelium:

- 10.

No significant correlations were found between the studied cytokines in the endothelium, suggesting that this structure may not play an active role in inflammatory regulation in our studied cases.

Inter-structure cross-correlations:

- 11.

Strong and very strong correlations of the IL-1α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-4, and IL-10 between the cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm cells, endothelium, and macrophages point to relationships between regional inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses across different cells and tissue areas. Such correlations may reveal systemic and localized regulatory mechanisms essential for maintaining homeostasis during fetal development.

We suggest that these correlations represent a complex regulatory network of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines during pregnancy. Correlations between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines indicate a need to balance inflammation in fetal tissues to prevent excessive inflammatory responses that could negatively impact delivery outcomes and fetal development as well.

It is noteworthy to mention that our study’s limitation could be that we did not perform control samples, despite that they provide reliable and comparable results, allowing researchers to interpret whether observed changes are related to the factor under study rather than external circumstances or chance. However, due to the ethical considerations, controls were not presented. Another limitation of our study, but also a possible future investigation could be using some other analyzing techniques, such as Western Blot and ELISA, that could detect specific protein molecules from among a mixture of proteins, including all the proteins associated with a particular structure or cell type of placentae, and determine specific cytokine concentrations. Additionally, it would certainly be useful to investigate the genes regulating and responsible for the expression of the studied cytokines in placental tissues.

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the 28th and 40th delivery week patient tissue samples. (a) Note the maternal part of placenta with abundance of Hofbauer cells (arrows). 100x; (b) Note fibrinoid deposits and practically unchanged placental structures (arrows). 100x.

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the 28th and 40th delivery week patient tissue samples. (a) Note the maternal part of placenta with abundance of Hofbauer cells (arrows). 100x; (b) Note fibrinoid deposits and practically unchanged placental structures (arrows). 100x.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-1α positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic cells and moderate positive Hofbauer cells (arrows) in the villi of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-1α IMH, 200x; (b) Numerous IL-1α positive extraembryonic mesoderm and blood vessel cells (arrows) of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-1α IMH, 200x; (c) Moderate IL-1α positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm cells and endothelium structures of the 40 weeks old placenta (arrows). IL-1α IMH, 200x.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-1α positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic cells and moderate positive Hofbauer cells (arrows) in the villi of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-1α IMH, 200x; (b) Numerous IL-1α positive extraembryonic mesoderm and blood vessel cells (arrows) of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-1α IMH, 200x; (c) Moderate IL-1α positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm cells and endothelium structures of the 40 weeks old placenta (arrows). IL-1α IMH, 200x.

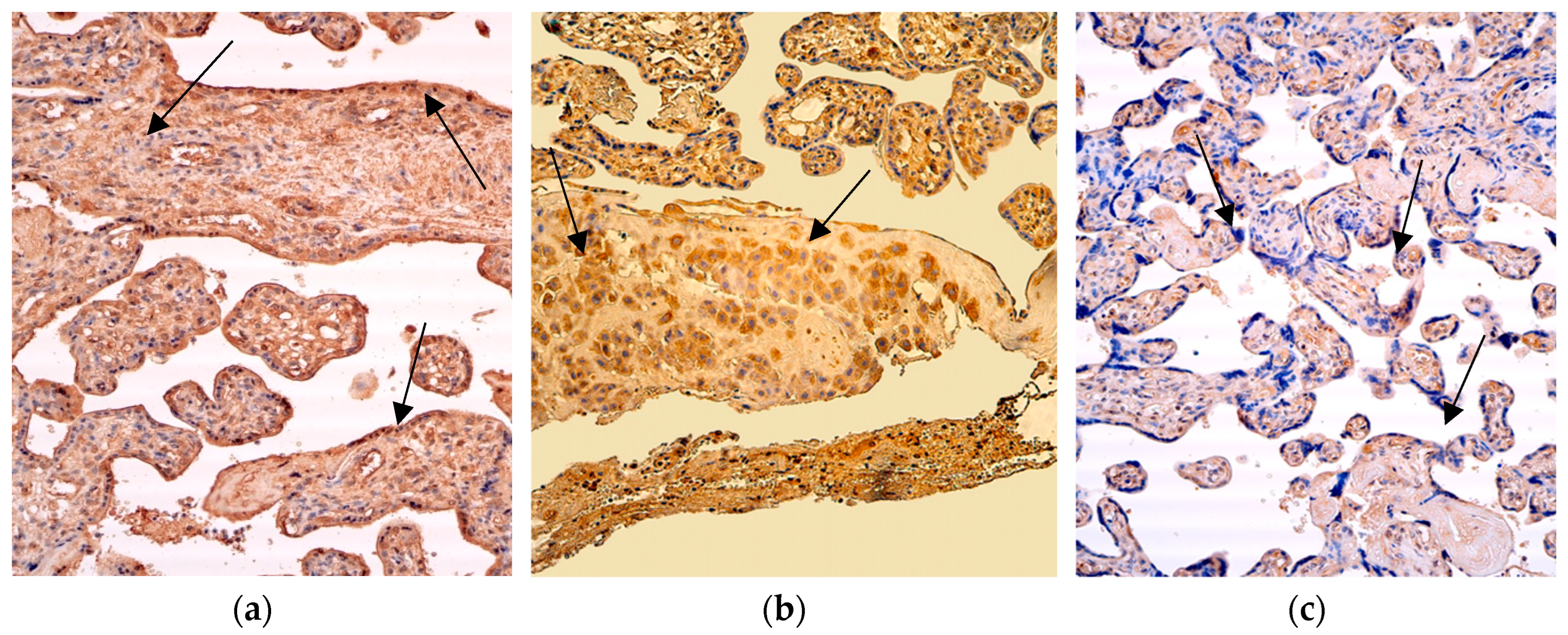

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-2 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic and endothelium cells (arrows) and moderate positive Hofbauer cells in the villi of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-2 IMH, 200x; (b) Abundance of macrophages and numerous IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast (arrows), endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-2 IMH, 200x; (c) Moderate IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm cells and endothelium structures (arrows) in the villi of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-2 IMH, 200x.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-2 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic and endothelium cells (arrows) and moderate positive Hofbauer cells in the villi of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-2 IMH, 200x; (b) Abundance of macrophages and numerous IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast (arrows), endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-2 IMH, 200x; (c) Moderate IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm cells and endothelium structures (arrows) in the villi of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-2 IMH, 200x.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-7 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Occasional occurrence of the IL-7 positive extraembryonic mesoderm cells and macrophages (arrows) in the visual field of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-7 IMH, 200x; (b) Moderate occurrence of the IL-7 positive extraembryonic mesoderm cells, cytotrophoblast and macrophages (arrows) in the visual field of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-7 IMH, 200x; (c) Few positive structures of the cytotrophoblast (arrows) and occasional occurrence of the extraembryonic mesoderm cells and endothelium positive structures of the IL-7 in the visual field of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-7 IMH, 200x.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-7 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Occasional occurrence of the IL-7 positive extraembryonic mesoderm cells and macrophages (arrows) in the visual field of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-7 IMH, 200x; (b) Moderate occurrence of the IL-7 positive extraembryonic mesoderm cells, cytotrophoblast and macrophages (arrows) in the visual field of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-7 IMH, 200x; (c) Few positive structures of the cytotrophoblast (arrows) and occasional occurrence of the extraembryonic mesoderm cells and endothelium positive structures of the IL-7 in the visual field of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-7 IMH, 200x.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-8 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive structures of the IL-8 in the visual field of the cytotrophoblast and macrophages (arrows) of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-8 IMH, 200x; (b) numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic, extraembryonic mesoderm, endothelium cells (arrows) and moderate positive Hofbauer cells in the villi of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-8 IMH, 200x; (c) moderate occurrence of the IL-8 positive structures in the visual field of the cytotrophoblast and extraembyonic mesoderm (arrows) of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-8 IMH, 200x.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-8 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive structures of the IL-8 in the visual field of the cytotrophoblast and macrophages (arrows) of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-8 IMH, 200x; (b) numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic, extraembryonic mesoderm, endothelium cells (arrows) and moderate positive Hofbauer cells in the villi of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-8 IMH, 200x; (c) moderate occurrence of the IL-8 positive structures in the visual field of the cytotrophoblast and extraembyonic mesoderm (arrows) of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-8 IMH, 200x.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-4 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) No IL-4 positive structures (arrows), except some occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm cells of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-4 IMH, 200x; (b) occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm and Hofbauer cells, and no IL-4 positive cytotrophoblastic and endothelium cells (arrows) in the villi of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-4 IMH, 200x; (c) few positive macrophages (arrows) and occasional IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast, endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-4 IMH, 200x.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-4 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) No IL-4 positive structures (arrows), except some occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm cells of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-4 IMH, 200x; (b) occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm and Hofbauer cells, and no IL-4 positive cytotrophoblastic and endothelium cells (arrows) in the villi of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-4 IMH, 200x; (c) few positive macrophages (arrows) and occasional IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast, endothelium and extraembryonic mesoderm cells of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-4 IMH, 200x.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-10 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) No IL-10 positive structures of the 28 weeks old placenta (arrows). IL-10 IMH, 200x; (b) occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm and Hofbauer cells (arrows) in the villi of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-10 IMH, 200x; (c) no IL-10 positive cytotrophoblast, macrophages, endothelium, and occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm cells (arrows) of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-10 IMH, 200x.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-10 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) No IL-10 positive structures of the 28 weeks old placenta (arrows). IL-10 IMH, 200x; (b) occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm and Hofbauer cells (arrows) in the villi of the 31 weeks old placenta. IL-10 IMH, 200x; (c) no IL-10 positive cytotrophoblast, macrophages, endothelium, and occasional positive for factor extraembryonic mesoderm cells (arrows) of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-10 IMH, 200x.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-6 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic and extraembryonic cells (arrows) and moderate positive Hofbauer and endothelium cells in the villi of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-6 IMH, 200x; (b) abundance of the IL-6 positive macrophages in the visual field of the 31 weeks old placenta (arrows). IL-6, IMH, 200x; (c) occasional occurrence of the IL-6 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium cells (arrows) in the villi of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-6 IMH, 200x.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemistry of the IL-6 positive structures in the patient tissue samples. (a) Numerous positive for factor cytotrophoblastic and extraembryonic cells (arrows) and moderate positive Hofbauer and endothelium cells in the villi of the 28 weeks old placenta. IL-6 IMH, 200x; (b) abundance of the IL-6 positive macrophages in the visual field of the 31 weeks old placenta (arrows). IL-6, IMH, 200x; (c) occasional occurrence of the IL-6 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and endothelium cells (arrows) in the villi of the 40 weeks old placenta. IL-6 IMH, 200x.

Table 1.

Info about the patients.

Table 1.

Info about the patients.

| No. |

Female age |

Graviditas |

Partus |

Delivery weeks/problems |

| 7. |

36 |

I |

I |

28, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 14. |

20 |

I |

I |

28, Fetus premature pathology, distress acuta |

| 19. |

31 |

II |

II |

28, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 20. |

26 |

I |

I |

28, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 24. |

36 |

II |

I |

28, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 22. |

36 |

II |

II |

31, Partum premature operationis, distress acuta |

| 23. |

39 |

VI |

II |

31, Partum premature operationis, distress acuta |

| 26. |

36 |

I |

I |

31, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 32. |

28 |

IV |

I |

31, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 33. |

28 |

IV |

I |

31, Spontaneous preterm delivery, distress acuta |

| 2. |

39 |

IV |

II |

40, Partus mature, distress acuta |

| 9. |

27 |

III |

III |

40, Partus mature, distress acuta |

| 10. |

23 |

I |

I |

40, Partus mature, distress acuta |

| 13. |

31 |

III |

I |

40, Partus mature operationis, distress acuta |

| 16. |

22 |

I |

I |

40, Partus mature, distress acuta |

Table 2.

The semi-quantitative counting method and the explanation of the identifiers.

Table 2.

The semi-quantitative counting method and the explanation of the identifiers.

| Identifier used |

Explanation |

| 0 |

No staining in the visual field (0) |

| 0/+ |

Occasional occurrence of positive structures in the visual field (0,5) |

| + |

Few positive structures in the visual field (1) |

| ++ |

Moderate occurrence of positive structures in the visual field (2) |

| +++ |

Numerous positive structures in the visual field (3) |

| ++++ |

Abundant staining in the visual field (4) |

Table 3.

Semi-quantitative data analysis of the IL-1α and IL-2 cytokines.

Table 3.

Semi-quantitative data analysis of the IL-1α and IL-2 cytokines.

| Factor |

IL-1 alpha |

IL-2 |

| Tissue |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

| Patients |

28 weeks |

| 7. |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

| 14. |

++ |

++ |

0 |

+ |

++ |

+/0 |

+++ |

+/0 |

| 19. |

++++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

| 20. |

++++ |

+++ |

++++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

| 24. |

+++ |

+++ |

0 |

++ |

++++ |

+++ |

0 |

++ |

| Median value |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

| |

31 weeks |

| 22. |

++++ |

+++ |

++++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++++ |

++ |

| 32. |

++ |

++++ |

+++ |

++++ |

++ |

++ |

++++ |

+++ |

| 23. |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

| 26. |

+++ |

+++ |

++++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

++++ |

+++ |

| 33. |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/0 |

| Median value |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

++++ |

++ |

| |

40 weeks |

| 9. |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

++++ |

++ |

| 2. |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

+/0 |

+/0 |

| 10. |

+++ |

+++ |

0 |

+++ |

+/0 |

+ |

+++ |

+/0 |

| 13. |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| 16. |

+++ |

++++ |

+ |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

+/0 |

+/0 |

| Median value |

+++ |

+++ |

+ |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+/0 |

Table 4.

Comparison of the IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages, and endothelium cells between patient groups with different delivery weeks.

Table 4.

Comparison of the IL-2 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages, and endothelium cells between patient groups with different delivery weeks.

| Pairwise Comparisons of the IL-2 positive structures in the cytotrophoblast across three delivery weeks |

|---|

| Samples |

Test Statistic |

Std. Error |

Std. Test Statistic |

Sig. |

Adj. Sig. a |

| 40weeks-31weeks |

4,700 |

2,726 |

1,724 |

0,085 |

0,254 |

| 40weeks-28weeks |

7,900 |

2,726 |

2,899 |

0,004 |

0,011 |

| 31weeks-28weeks |

3,200 |

2,726 |

1,174 |

0,240 |

0,721 |

Table 5.

Semi-quantitative data analysis of the IL-7 and IL-8 cytokines.

Table 5.

Semi-quantitative data analysis of the IL-7 and IL-8 cytokines.

| Factor |

IL-7 |

IL-8 |

| Tissue |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

| Patients |

28 weeks |

| 7. |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

| 14. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

++ |

+/0 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| 19. |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

| 20. |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

+/0 |

+++ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

| 24. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

+++ |

++ |

+/0 |

++ |

| Median value |

+/0 |

+/0 |

++ |

+/0 |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

| |

31 weeks |

| 22. |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+ |

++ |

++++ |

++ |

+ |

| 32. |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

| 23. |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

+++ |

+++ |

+/0 |

++ |

| 26. |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

+/0 |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

| 33. |

+/0 |

+ |

0 |

0 |

++ |

+ |

+++ |

+ |

| Median value |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

| |

40 weeks |

| 9. |

+ |

+/0 |

+++ |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

| 2. |

++ |

+ |

+/0 |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

+/0 |

+ |

| 10. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+ |

0 |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

| 13. |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

+/0 |

+ |

+++ |

0 |

+ |

| 16. |

+/0 |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

++ |

++ |

+ |

+ |

| Median value |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+ |

+/0 |

++ |

++ |

+ |

+ |

Table 6.

Semi-quantitative data analysis of the IL-4, IL-10 and IL-6 cytokines.

Table 6.

Semi-quantitative data analysis of the IL-4, IL-10 and IL-6 cytokines.

| Factor |

IL-4 |

IL-10 |

IL-6 |

| Tissue |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

Cytot. |

E.m. |

Ma. |

End. |

| Patients |

28 weeks |

| 7. |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+ |

0 |

| 14. |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

++ |

+/0 |

| 19. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

++ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

| 20. |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| 24. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

| Median value |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

| |

31 weeks |

| 22. |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

++ |

+/0 |

| 32. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+ |

0 |

++ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

| 23. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

++ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| 26. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

++ |

++ |

++++ |

+ |

| 33. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

+/0 |

| Median value |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

++ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

| |

40 weeks |

| 9. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+ |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+++ |

+/0 |

| 2. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+ |

+/0 |

+ |

| 10. |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

++++ |

++ |

| 13. |

0 |

+/0 |

+ |

0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

| 16. |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

| Median value |

+/0 |

+/0 |

+ |

+/0 |

0 |

+/0 |

0 |

0 |

+/0 |

+ |

++ |

+ |

Table 7.

Comparison of the IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages, and endothelium cells between patient groups with different delivery weeks.

Table 7.

Comparison of the IL-4 positive cytotrophoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm, macrophages, and endothelium cells between patient groups with different delivery weeks.

| Pairwise Comparisons of the IL-4 positive macrophages across three delivery weeks |

|---|

| Samples |

Test Statistic |

Std. Error |

Std. Test Statistic |

Sig. |

Adj. Sig. a |

| 40weeks-31weeks |

-3,600 |

2,569 |

-1,401 |

0,161 |

0,483 |

| 40weeks-28weeks |

-6,900 |

2,569 |

-2,686 |

0,007 |

0,022 |

| 31weeks-28weeks |

-3,300 |

2,569 |

-1,285 |

0,199 |

0,597 |

| Pairwise Comparisons of the IL-4 positive structures in the endothelium across three delivery weeks |

| 28weeks-31weeks |

-1,400 |

2,345 |

-0,597 |

0,551 |

1,000 |

| 28weeks-40weeks |

-6,100 |

2,345 |

-2,601 |

0,009 |

0,028 |

| 31weeks-40weeks |

-4,700 |

2,345 |

-2,004 |

0,045 |

0,135 |