1. Introduction

Grafting is one of the most commonly used asexual reproduction methods in plants, involving the attachment of organs or tissues from one plant to another plant at an appropriate site, allowing the two to heal into a new plant. Grafting technology is widely used in the cultivation of vegetables, fruit trees, flowers, and forestry, as well as in research areas such as plant physiology, pathology, virology, and organogenesis[

1]. Additionally, it plays important roles in preserving germplasm resources, improving production efficiency, enhancing crop quality, controlling growth and development, and increasing stress resistance[

1]. Apple asexual propagation is almost exclusively done through grafting to enhance resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, there are often instances of plant death, wind breakage, and slow growth after grafting, which are mainly caused by differences in genetic background, grafting environment, and grafting techniques[

3], with genetic background differences being the most significant. It is generally believed that the closer the kinship between scion and rootstock, the stronger the grafting compatibility[

4].

The process of graft junction formation were usually divided into three stages[

37]: (1) After mechanical damage, the broken cell tissues at the graft interface of the rootstock and scion form an isolation layer, which is considered a universal response of plants to mechanical damage and is unrelated to graft compatibility[

5]. (2) The isolation layer gradually disappears as callus tissue forms and proliferates. Once the callus tissues from the scion and rootstock come into contact and merge, they form a callus tissue bridge that facilitates material exchange and cell-to-cell communication[

6] Plasmodesmata-associated genes were observed upregulated immediately after callus adhesion that may provide a link to symplasm establishment[

7]. Plasmodesmata is the basis for the further differentiation of the cambium into xylem and phloem and the reconnection of the vascular bundles[

8]. (3) The callus tissue re-differentiates into xylem and phloem and other conductive tissues, establishing a vascular bundle bridge between the scion and rootstock, enabling the exchange of water, inorganic salts, and macromolecules [

8].

Many studies on grafting healing processes and graft compatibility have already revealed the genes and metabolites involved in the transition from wound response to vascular reconnection between the rootstock and scion in Arabidopsis [

9]. Many species, such as grapevines[

10], lychee trees[

11], and hickory trees[

12], induce thousands of differentially expressed genes during grafting. Most graft induced genes are involved in wound response, hormone response, signal transduction, and cell wall synthesis[

13,

14]. Most of these differentially expressed genes are asymmetrically expressed between the rootstock and scion, with many of them being sugar-responsive genes, which may be related to the accumulation of starch above the graft union in the phloem tissue [

15]. The accumulation of sugars in the scion and the depletion of sugars in the rootstock can lead to asymmetric expression levels of sugar-induced genes such as ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (ApL3), dark inducible 6 (DIN6), glutamate dehydrogenase 1 (GDH1), and sugar transporter protein 1 (STP1). This asymmetric gene expression is a critical feature of grafting and tissue healing and may play an important role in vascular connections at the graft union[

15]. β-1,4-glucanase, encoded by the glycosyl hydrolase gene GH9B3, has been shown to be secreted into the extracellular region during the grafting process in tobacco, altering the cell wall structure to facilitate contact and signal exchange between rootstock and scion cells, enabling successful grafting between Nicotiana species and a diverse range of angiosperms[

16]. Sugar transporters SWEET15 and SWEET19 have been shown to activate cell-to-cell communication between scion and rootstock cells[

15]. Although the role of sugars in vascular formation is not fully established, sugars are known to promote cell division and expansion[

17], such as sucrose affecting the quantity of callus tissue on sieve plates and further promoting the formation of vascular bundles, indicating that the formation of phloem and xylem requires the presence of sugars[

18]. Adding 0.5% sucrose to the grafting medium can accelerate recovery after grafting and increase graft success rates[

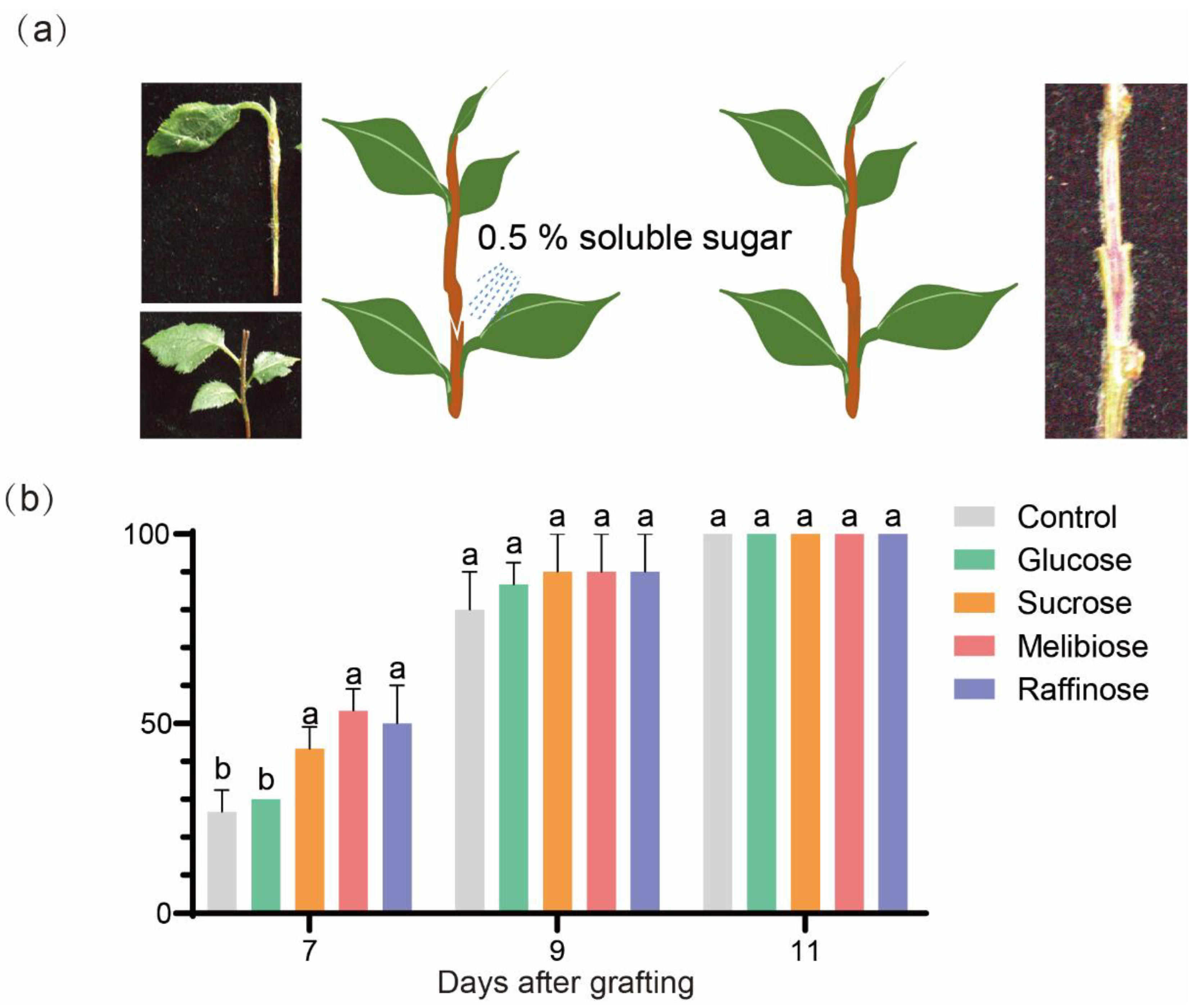

19].

In this study, Malus domestica (‘Hanfu’) homograft was performed to examine changes in gene expression and metabolite profiles during the whole process of graft junction formation in order to identify genes and metabolism involved in this process, highlighting genes and metabolites in different stages in order to construct transcriptional and metabolic regulation network in graft junction formation.

2. Results

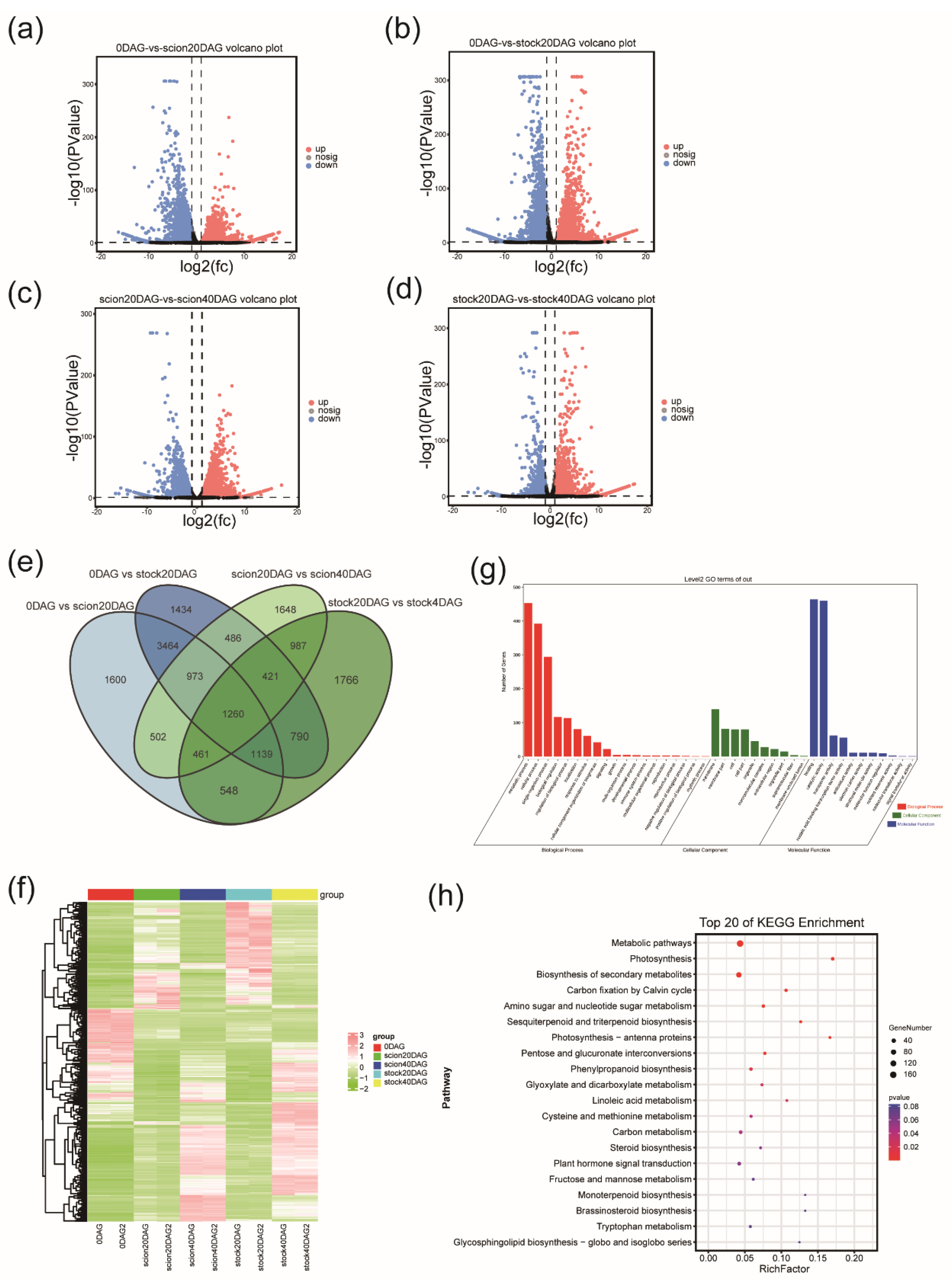

RNA Sequencing and Functional Annotation of DEGs

Samples were collected as described(

Figure S1). A total of 18 samples were tested in this analysis, and 90.16 Gb of data was obtained, and the percentage of Q30 bases was 95.25% or above. Rawdata obtained by sequencing were filtered, and clean reads obtained were compared to the reference sequence. Sequence alignment between CleanReads of each sample and the HFTH1 reference genome [

20] was performed using Histaq2. The matching rate of alignment ranged from 93.88% to 96.66%. After matching the sequenced reads to the reference genome and reconstructing transcripts, a total of 2,701 new genes were detected, of which 2,543 were functionally annotated.

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to visualize the transcriptome trend of the 18 samples analyzed. The first two principal components defined 28.2% and 20% of the variance among samples, respectively (

Figure 2a). PCA result showed great transcriptomic changes after grafting. In the PCA score plot, samples at 0 DAG with the lowest PC1 scores are distant from the other samples. The stock and the scion samples at 10 DAG and 20 DAG are distant apart, while they are close at 30 DAG and 40 DAG. These results indicate that there is a clear asymmetry in gene expression patterns between the rootstock and scion during the early stages of the grafting process, which involved callus tissue differentiation and proliferation, while gene expression patterns became similar in the later stages, which involved vascular reconnection.

Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

To gain further insight into the transcriptomic changes throughout grafting WGCNA was conducted to gain co-expression of genes. Six modules of genes were identified (

Figure 2b,c,

Table S1). The yellow module contained 476 genes which were highly expressed in the early stages (0-20 DAG) in the scion but relatively weakly expressed in the stock. The brown module had 2376 genes, which were more active in the stock in the early stage (0-20 DAG) of graft junction formation. The 4272 genes in the turquoise module were highly expressed in the late stage (20-40 DAG) of graft junction formation both in the scion and the stock. To further understand the roles of these genes, KEGG enrichment analyses were applied to the three modules.

The most enriched pathways in the yellow module included ‘Starch and sucrose metabolism’, ‘Tyrosine metabolism’, ‘Isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis’, and ‘Amino acid metabolism’, while the main enriched pathways in the brown module included ‘Spliceosome’, ‘RNA degradation’, ‘Oxidative phosphorylation’ and ‘Peroxisome’. The result again suggested that the scion and the stock cells around the graft junction differed greatly in transcriptome. The main enriched pathways in the turquoise module, with genes displaying an increasing expression pattern in both the stock and the scion, included ‘RNA transport’, ‘mRNA surveillance pathway’, ‘Purine metabolism’, ‘RNA degradation’, and ‘Proteasome’, suggesting activation of gene translation and error-correcting functions in translation during graft junction formation in both the stock and the scion(

Figure 2d-f).

3. Discussion

Scion vs Stock Asymmetry Response to Grafting is more Pronounced in Phase I

In previous studies, the rootstock and scion showed asymmetrical responses to grafting[

26]. Some plant hormones such as auxins, and transcription factor genes such as ANAC071 and RAP2.6L, exhibit significant differences between the rootstock and the scion[

27,

28]. Physiological indexes such as sugar contents and their change patterns in grafted grapefruit showed asymmetry between the scion and the stock[

29]. In our study, the asymmetrical response to grafting could be observed in callus formation, as callus formation occurs earlier in the scion. The transcriptome results also showed that there are more DEGs in the scions and the stock in phase I than in phase II. Significant differences in gene expression profile between the rootstock and the scion in phase I of graft healing. Those genes belonged to the brown and yellow modules in the WGCNA analysis results, and their expression patterns became more similar in Phase II. Both PCAs based on the transcriptome data and the metabolome data proved that asymmetry between the scion and the stock is more pronounced in phase I than phase II, suggesting such asymmetry disappears with the vascular reconnection between the two graft parts. Our findings are consistent with those reported by Melnyk et al. (2015) in Arabidopsis, suggesting that the observed phenomena are not limited to a single species[

25].

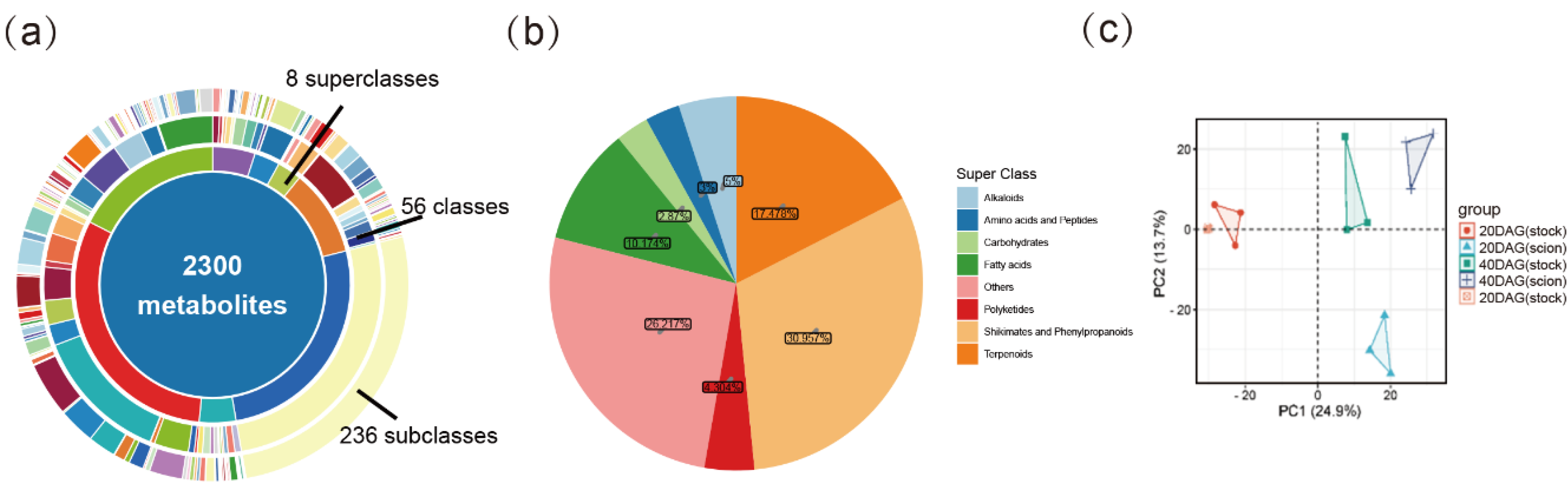

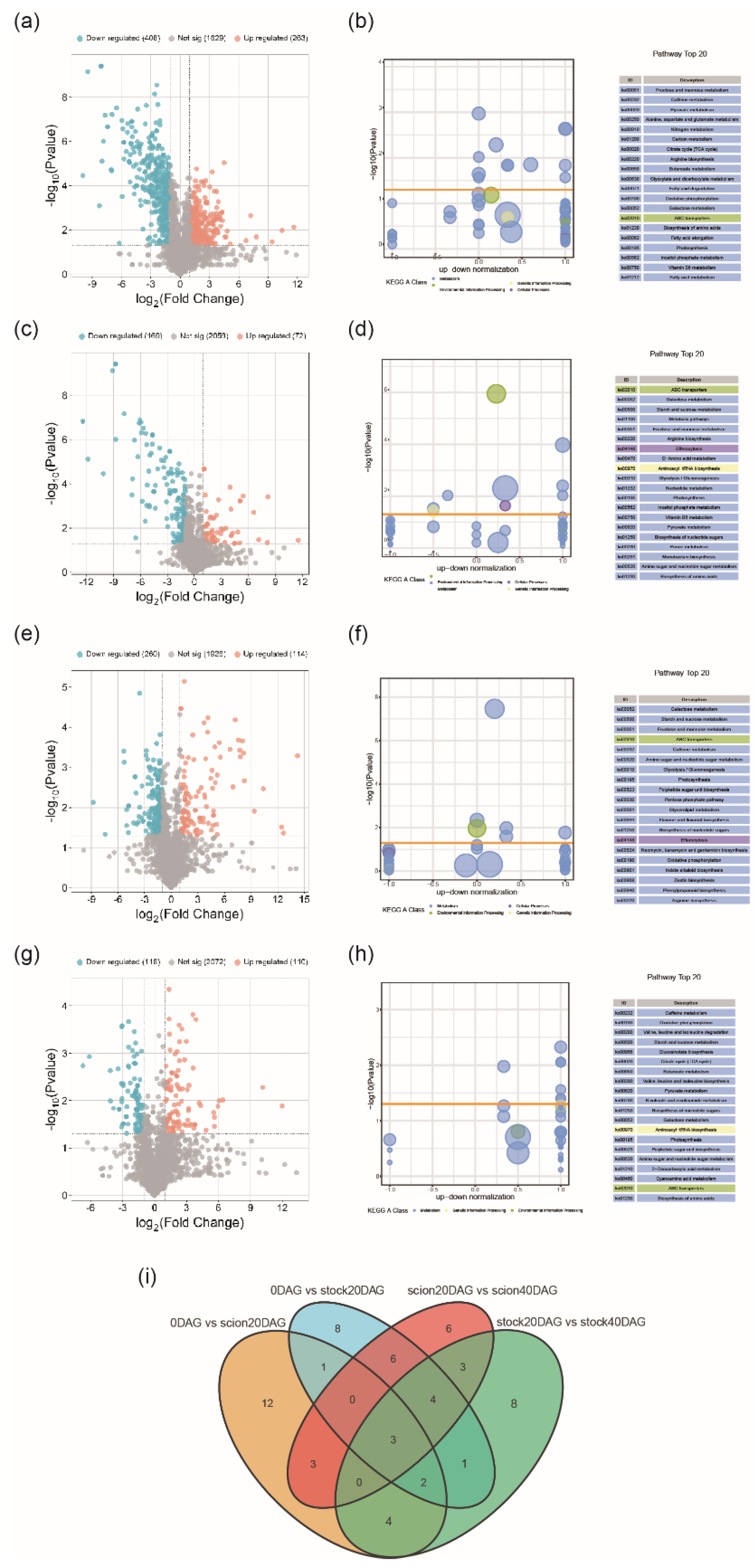

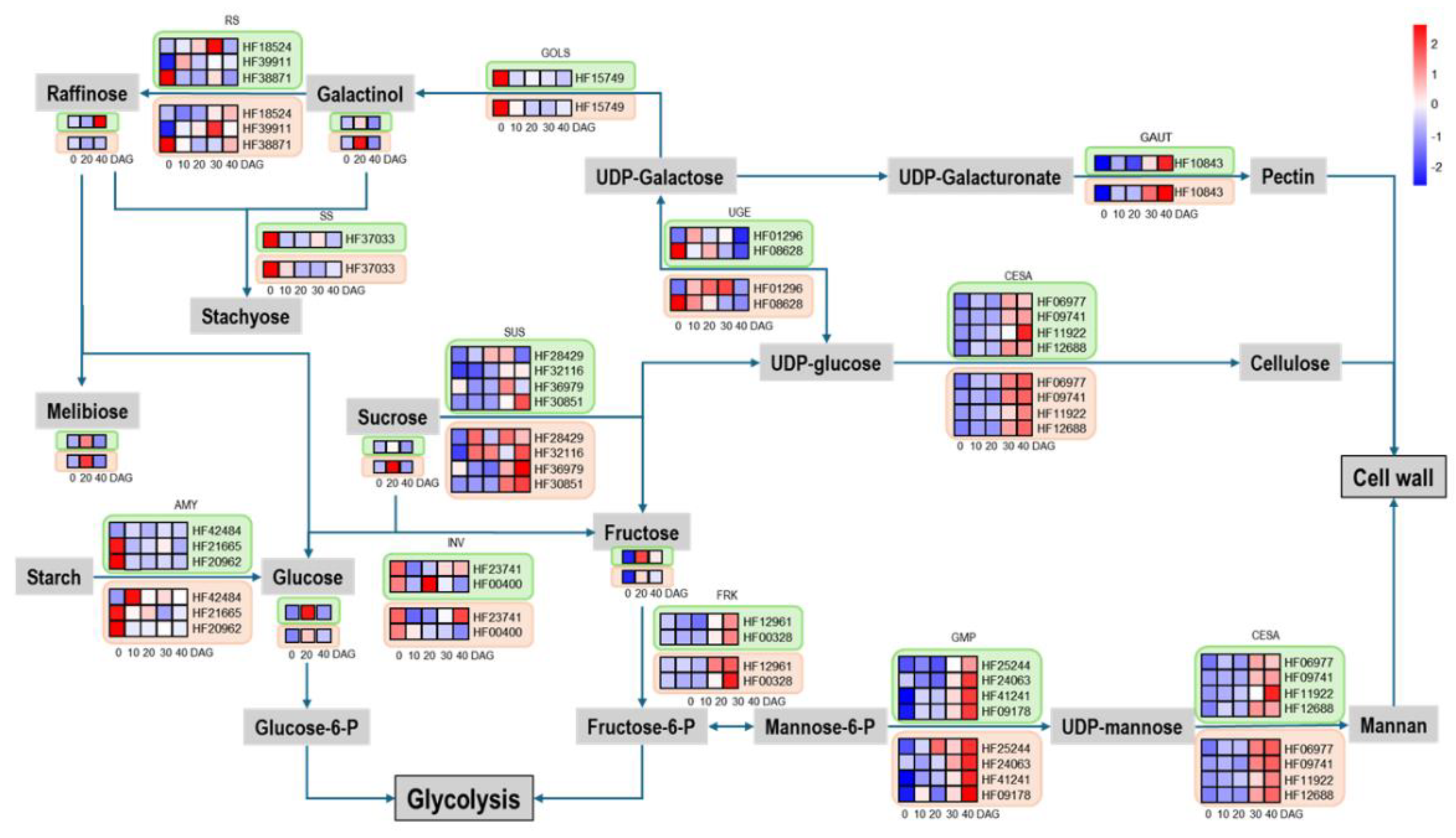

We selected DEGs and DEMs at three key time points (0, 20 and 40 DGA) for KEGG enrichment analysis. The results showed that these DEGs and DEMs were significantly enriched in sugar metabolic pathways. Considering that sugars, as important substrates in plant cell energy metabolism, are widely involved in cell growth and development, and can also serve as monomers to polymerize into cellulose, starch, and other macromolecules, participating in cell construction, the differences in sugar metabolism may be related to the asymmetric expression patterns of the rootstock and scion during the grafting process. We found that various sugars, including glucose, fructose, stachyose, and melibiose, were most abundant at 20DAG, the boundary between the early and late stages of graft healing, and significantly decreased after the vascular bundles were fully reconnected. Similarly, various sugar metabolic synthesis genes were highly expressed at 20DAG and then gradually decreased.

4. Materials and Methods

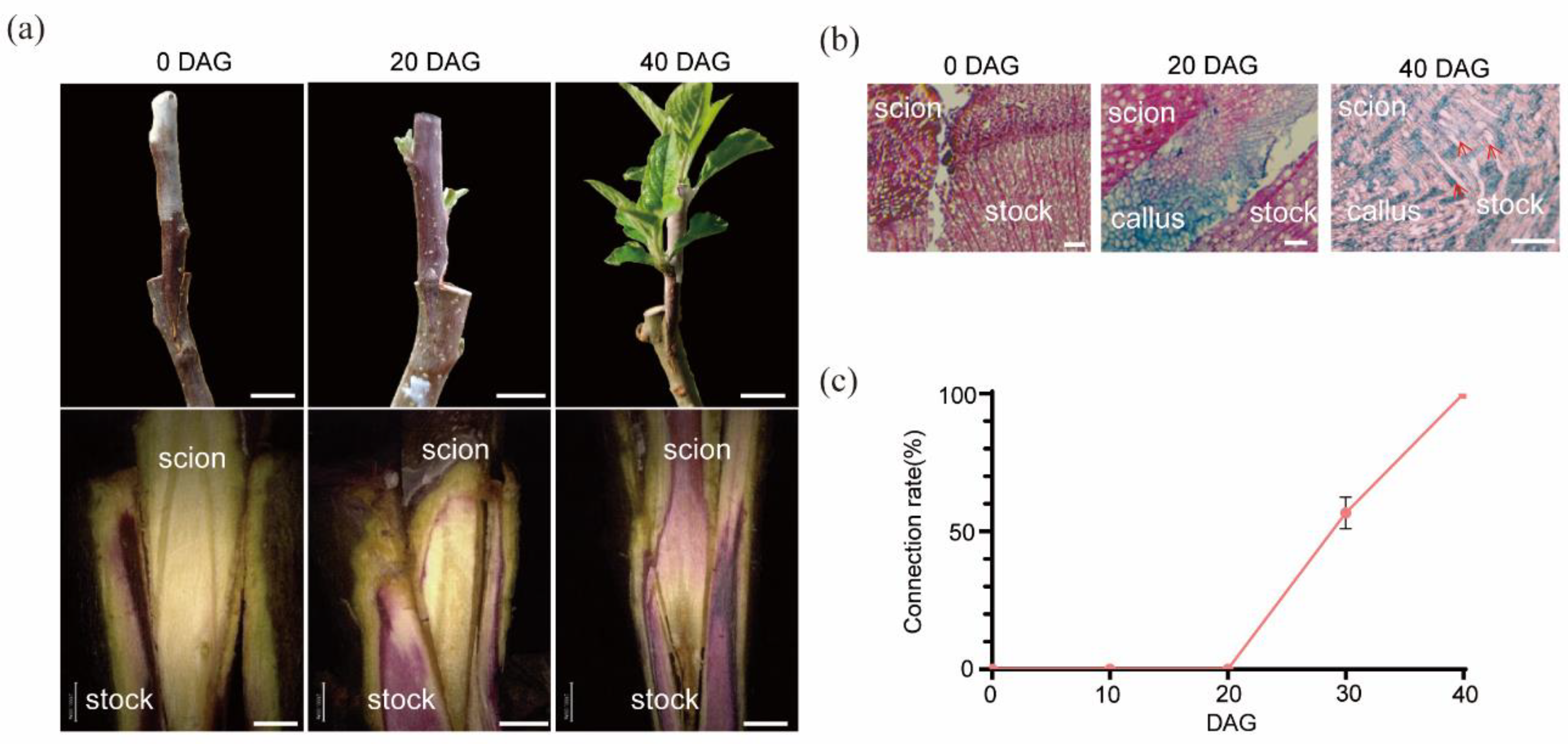

Plant Materials and Grafting Methods

For analysis of the mechanism involved in graft junction formation in apple (Malus domestica), homograft was conducted using 1-year-old plants of cultivar ’Hanfu’ (Malus domestica). These plants were cultivated in the experimental fields of China Agricultural University. Scions, with a stem diameter of approximately 1cm, from specific ‘Hanfu’ plants were grafted onto ‘Hanfu’ rootstocks a similar diameter. The homograft plants were generated using cleft grafting method on 20th March 2024. Graft junctions were randomly sampled at 0, 10, 20, 30 and 40 days after grafting (DAG) for further anatomic, transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses.

For the experiment with sugar treatments, ‘Hanfu’ in vitro seedlings with stem diameter larger than 3 mm, which had been cultivated on the root forming mediate (MS + 1.0 mg/L IBA + 6.5 g/L agar pH=5.8) for a month, were selected for micrografting using cleft grafting method. The grafted plants were incubated under a photoperiod of 16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness at a temperature of 25°C.

Transcriptome Sequencing and Analyses

To construct transcriptomic libraries, graft junction samples, consisting of 0.25 cm from grafting site of the stock seedling at 0 DAG, 0.25 cm from the scion and 0.25 cm from the stock at the rest sample times (

Figure S1) were collected and immediately frozen in the liquid nitrogen and quickly ground into powder using a grinder. Total RNA was extracted with an EASYspin Plant Total RNA Rapid Extraction kit (Biomed Company, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two biological replicates, each with ten randomly pooled 10 graft junctions, were used to build RNA-seq libraries. RNA quality was assessed using gel electrophoresis apparatus and nanodrop spectrophotometer. RNA with concentration of over 300 µg/mL, 28S rRNAs/18S rRNAs ratio of over 2, and RNA integrity number of over 6 were used to build the RNA-seq library. RNA sequencing was performed using the Illumina Hiseq4000 platform at Biomec Biotechnology, following standard protocols for library preparation and sequencing. The FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) was calculated using featureCounts[

39]. Differential expression analysis between groups was performed using DESeq2[

40]. DEGs for two-group were identified using pvalue(<0.05) and |Log2FC| (≥1.0). To gain further insights into the graft junction formation Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis and Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) analysis were constructed using Ggplot2 and WGCNA packages in R script.

RT–qPCR Validation

RT-qPCR was performed with the SYBR Green I Master kit (TIAN-GEN, Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used in this experiment were showed in Tablet S5. Apple actin gene was analyzed as an internal control using primer pair MdActin-F/MdActin-R. The qPCR procedure was conducted as follows: all reactions were incubated on 96-well plates at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 32 s, then 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 15 s. qPCR analysis was conducted in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA).

Exogenous Soluble Sugars Treatments on Grafted Plantlets

To test the effect of soluble sugars on graft healing, exogenous glucose, sucrose, raffinose or meliobiose solution at a concentration of 0.5% (W/V) was sprayed on the graft junction of the micro-grafted plants at 0 DAG. Three biological replicates, each with 10 grafted plantlets were used for every treatment. Vascular connection observation was carried out with acid fuchsin as mentioned above.

5. Conclusions

The graft junction formation process consists of two phases: Phase I (0-20 days) involves callus formation and proliferation, while Phase II (20-40 days) is characterized by vascular reconnection. During Phase I, a significant asymmetry is observed between the scion and the rootstock, which gradually diminishes as vascular reconnection progresses. Sugar metabolism plays a crucial role in the formation of the graft junction, especially in the accumulation of sugars during callus formation and their subsequent consumption following vascular reconnection. The application of exogenous sugars (such as sucrose, raffinose, and melibiose) can significantly promote the formation and healing of the graft junction, indicating that sugar supply is essential for successful grafting.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by W.T. Huang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by W.T. Huang and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Micrograft experiment performed by C Mao. Review and editing was performed by S. Y. Wang. Resources were prepared by L Xiang and X. Zhang. Ideology and manuscript polish were performed by F. Jiang and Y. Q. Cheng. The fund source was T Z. Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32302494) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1003102)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in this article. The

datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants and colleagues for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, Y., Kong, Q. S., Chen, F. & Bie, Z. L. (2014) The history, current status and future prospects of vegetable grafting in China. I Int. Symp . Veg. Grafting 1086, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Mudge, K., Janick, J., Scofield, S., Goldschmidt, E. E. (2009). A history of grafting. Horticultural Reviews, 35. 35, 437–493. [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, S., Pina, A., Fevereiro, P., Kragler, F. (2020). A phenotypic search on graft compatibility in grapevine. Agronomy, 10(5), 706. [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, E. E. (2014). Plant grafting: New mechanisms, evolutionary implications. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5(727), 727. [CrossRef]

- Gur A, Samish RM, Lifshitz E. (1968). Role of cyanogenic glycoside of quince in incompatibility between pear cultivars and quince rootstocks. Horticultural Research 8, 113–134.

- Kollmann R, Yang S, Glockmann C. (1985). Studies on graft unions. II. Continuous and half plasmodesmata in different regions of the graft interface. Protoplasma 126, 19–29.

- Kurotani KI, Notaguchi M. 2021. Cell-to-cell connection in plant grafting—Molecular insights into symplasmic reconstruction. Plant and Cell Physiology 62, 1362–1371. [CrossRef]

- Jeffree CE, Yeoman MM. (1983). Development of intercellular connections between opposing cells in a graft union. New Phytologist 93, 491–509. [CrossRef]

- Flaishman MA, Loginovsky K, Golobowich S, Lev-Yadun S. (2008). Arabidopsis thaliana as a model system for graft union development in homografts and heterografts. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 27, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Cookson SJ; et al. (2013) Graft union formation in grapevine induces transcriptional changes related to cell wall modification, wounding, hormone signalling, and secondary metabolism. J Exp Bot 64:2997–3008. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Zhao, J. , Hu, F. , Qin, Y. , Wang, X., Hu, G.(2017). Transcriptome changes between compatible and incompatible graft combination of litchi chinensis by digital gene expression profile. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3954. [CrossRef]

- Zheng BS; et al. (2010) cDNA-AFLP analysis of gene expression in hickory (Carya cathayensis) during graft process. Tree Physiol 30:297–303. [CrossRef]

- Thomas H, Van den Broeck L, Spurney R, Sozzani R, Frank M. (2021). Gene regulatory networks for compatible versus incompatible grafts identify a role for SlWOX4 during junction formation. The Plant Cell 34, 535–556. [CrossRef]

- Mazur E, Benková E, Friml J. (2016). Vasc cambium regeneration and vessel formation in wounded inflorescence stems of Arabidopsis. Scientific Reports 6, 33754. [CrossRef]

- Yin H, Yan B, Sun J, Jia P , Zhang Z, Yan X, Chai J, Ren Z, Zheng G, Liu H. (2012). Graft-union development: A delicate process that involves cell–cell communication between scion and stock for local auxin accumulation. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 4219–4232. [CrossRef]

- Notaguchi, M., Kurotani, K. I., Sato, Y., Tabata, R., Kawakatsu, Y., Okayasu,K.; et al. (2020). Cell-cell adhesion in plant grafting is facilitated by β-1,4-glucanases. Science 369, 698–702. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. & Kollmann, R. (1996). Vascular differentiation in the graft union of in-vitro grafts with different compatibility.—Structural and functional aspects. J. Plant Physiol. 147, 521–533. [CrossRef]

- Aloni, R. (1980). Role of auxin and sucrose in the differentiation of sieve and tracheary elements in plant tissue cultures. Planta 150, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Marsch-Martinez, N., Franken, J., Gonzalez-Aguilera, K.L., Folter, S., Angenent, G.C., Alvarez-Buylla, E.R. (2013). An efficient flat-surface collar-free grafting method for Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant Methods 9, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Hu J, Han X, Li J, Gao Y, Richards C M, Zhang C, Tian Y, Liu G, Gu H; et al. (2019). A high-quality apple genome assembly reveals the association of a retrotransposon and red fruit colour. Nat Commun 10, 1494. [CrossRef]

- Cookson, S., J., Clemente, Moreno, & M.; et al. (2014). Heterografting with nonself rootstocks induces genes involved in stress responses at the graft interface when compared with autografted controls. Journal of Experimental Botany. 65, 2473–2481. [CrossRef]

- Pina, A., and Errea, P. (2005). A review of new advances in mechanism of graft compatibility–incompatibility. Sci. Hortic. 106, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Pina A, Errea P, Martens HJ. (2012). Graft union formation and cell-to-cell communication via plasmodesmata in compatible and incompatible stem unions of Prunus spp. Scientia Horticulturae 143, 144–150. [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann R. (1989). Graft union development and symplastic phloem contact in the heterograft Cucumis sativus on Cucurbita ficifolia. Journal of Plant Physiology, 134(4), 427-440. [CrossRef]

- Melnyk CW, Schuster C, Leyser O, Meyerowitz E. (2015). A developmental framework for graft formation and vascular reconnection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol, 25 (10): 1306–1318. [CrossRef]

- Melnyk CW, Gabel A, Hardcastle TJ, Robinson S, Miyashima S, Grosse I, Meyerowitz EM. (2018). Transcriptome dynamics at Arabidopsis graft junctions reveal an intertissue recognition mechanism that activates vascular regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 115, E2447–E2456. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M. A. & Pickard, B. G. (1989). Auxin asymmetry during gravitropism by tomato hypocotyls. Plant Physiology, 89(2), 652-657. [CrossRef]

- Asahina M, Azuma K, Pitaksaringkarn W, Yamazaki T, Mitsuda N, Ohme-Takagi M, Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y, Okada K, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, Yokota T, Kamada H, Satoh S. (2011). Spatially selective hormonal control of RAP2.6L and ANAC071 transcription factors involved in tissue reunion in Arabidopsis. PNAS, 108 (38) 16128-16132. [CrossRef]

- Zhu TF, Wang Y, Su XL, Li X, Wang LC. (2022). Physiological characters in the stock and the scion during graft healing and their relation to graft compatibility in grapefruit. Jiangsu Agricultural Science, 50 (13) : 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Ruan YL (2013) . Regulation of cell division and expansion by sugar and auxin signaling. Front Plant Sci, 4: 163. [CrossRef]

- Lopes M A, Larkins B A. (1993). Endosperm origin, development, and function. The Plant Cell, 5(10): 1383-1399. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Hong J, Xia G, Huang Ji. (2009). Cytological observation on healing responses in grafting of Carya cathayensis. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 45(6): 34-38.

- Miao L, Li Q, Sun TS, Chai S, Wang CL, Bai LQ, Sun MT, Li YS, Qin X, Zhang ZH, Yu XC. (2021). Sugars promote graft union development in the heterograft of cucumber onto pumpkin. Hortic Res 8, 146, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Hoermayer L, Montesinos JC, Marhava P, Benková E, Yoshida S, Friml J. (2020). Wounding-induced changes in cellular pressure and localized auxin signalling spatially coordinate restorative divisions in roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Jun 30;117(26):15322-15331. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R., Karni, L., Aktas, H. & Edelstein, M. (2010). Hormonal signaling in rootstock-scion interactions. Sci. Hortic. 127, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Button J. (1978). The Effects of some Carbohydrates on the Growth and Organization of Citrus Ovular Callus. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenphysiologie, 88(1): 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Rasool A, Mansoor S, Bhat K M, Hassan G I, Baba T R, Alyemeni M N, Alsahli A A, El-Serehy H A, Paray B A, Ahmad P. (2020). Mechanisms Underlying Graft Union Formation and Rootstock Scion Interaction in Horticultural Plants. FRONTIERS IN PLANT SCIENCE, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li F, Wang XF. (2008). Advances in the Metabolism and Regulatory Key Enzymes of Raffinose Series Oligosaccharides in Plants. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica, 28(4): 8. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. (2014). featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics, 30, 923–930. [CrossRef]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Dillies, M.-A. (2016) SARTools: A DESeq2-and EdgeR-based R pipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-Seq data. PLoS ONE, 11, e0157022. [CrossRef]

- Westerhuis, J.A.; van Velzen, E.J.; Hoefsloot, H.C.; Smilde, A.K.(2010). Multivariate paired data analysis: Multilevel PLSDA versus OPLSDA. Metabolomics, 6, 119–128. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).