Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Intruduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Measurements of Plant Growth

2.3. Microscopic Observation of the Anatomical Structure

2.4. Quantification of ABA, IAA, ZR, GA3 and ETH

2.5. Assay of Enzyme Activity

2.6. Sugar Extract and Determination

2.7. Organic acid Extract and Determination

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survival Rate and Seedling Index of Watermelon Grafted onto Various Rootstocks

3.2. Optimal Seedling Ages for Watermelon Grafting onto ‘Heiniu’ Rootstock

| Treatment. | Scion Seedling Age (You Du) | Rootstock seedling age (Hei Niu) | Grafting combination |

| T1 | Cotyledon flattening (Six Days) | Cotyledon flattening (Five Days) | Cotyledon flattening / Cotyledon flattening |

| T2 | The first true leaf (Eight days) | Cotyledon flattening (Five Days) | The first true leaf / Cotyledon flattening |

| T3 | Two true leaf (Ten days) | Cotyledon flattening (Five Days) | Two true leaf / Cotyledon flattening |

| T4 | Cotyledon flattening (Six Days) | Two true leaf (Nine Days) | Cotyledon flattening / Two true leaf |

| T5 | The first true leaf (Eight days) | Two true leaf (Nine Days) | The first true leaf / Two true leaf |

| T6 | Two true leaf (Ten days) | Two true leaf (Nine Days) | Two true leaf / Two true leaf |

| CK | Cotyledon flattening (You Du) | Two true leaf (You Du) | Cotyledon flattening / Two true leaf |

3.3. The Anatomical Structures of Watermelon Graft Union

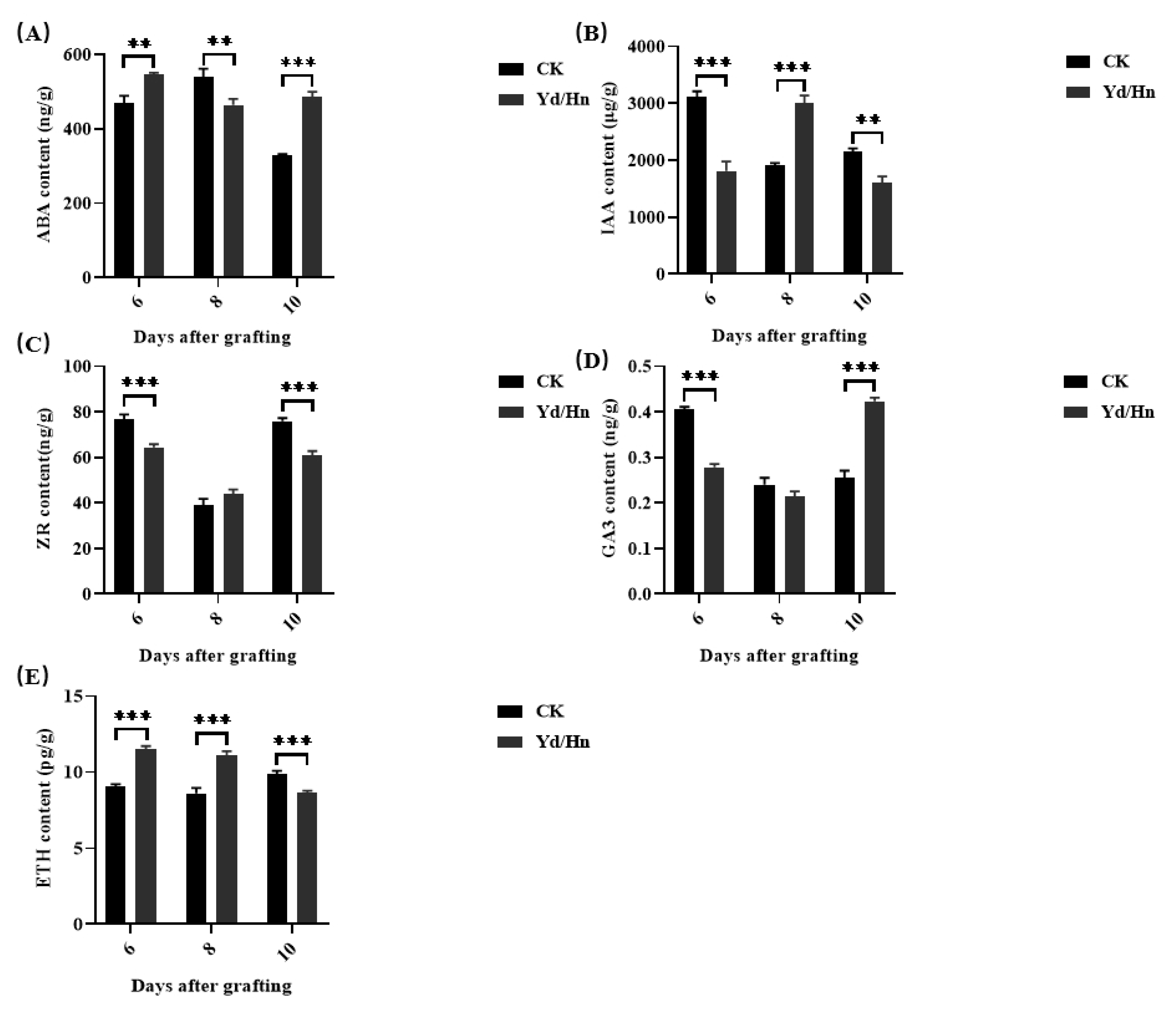

3.4. Measurement of Hormone Contents for Watermelon Graft Union During the Grafting Process

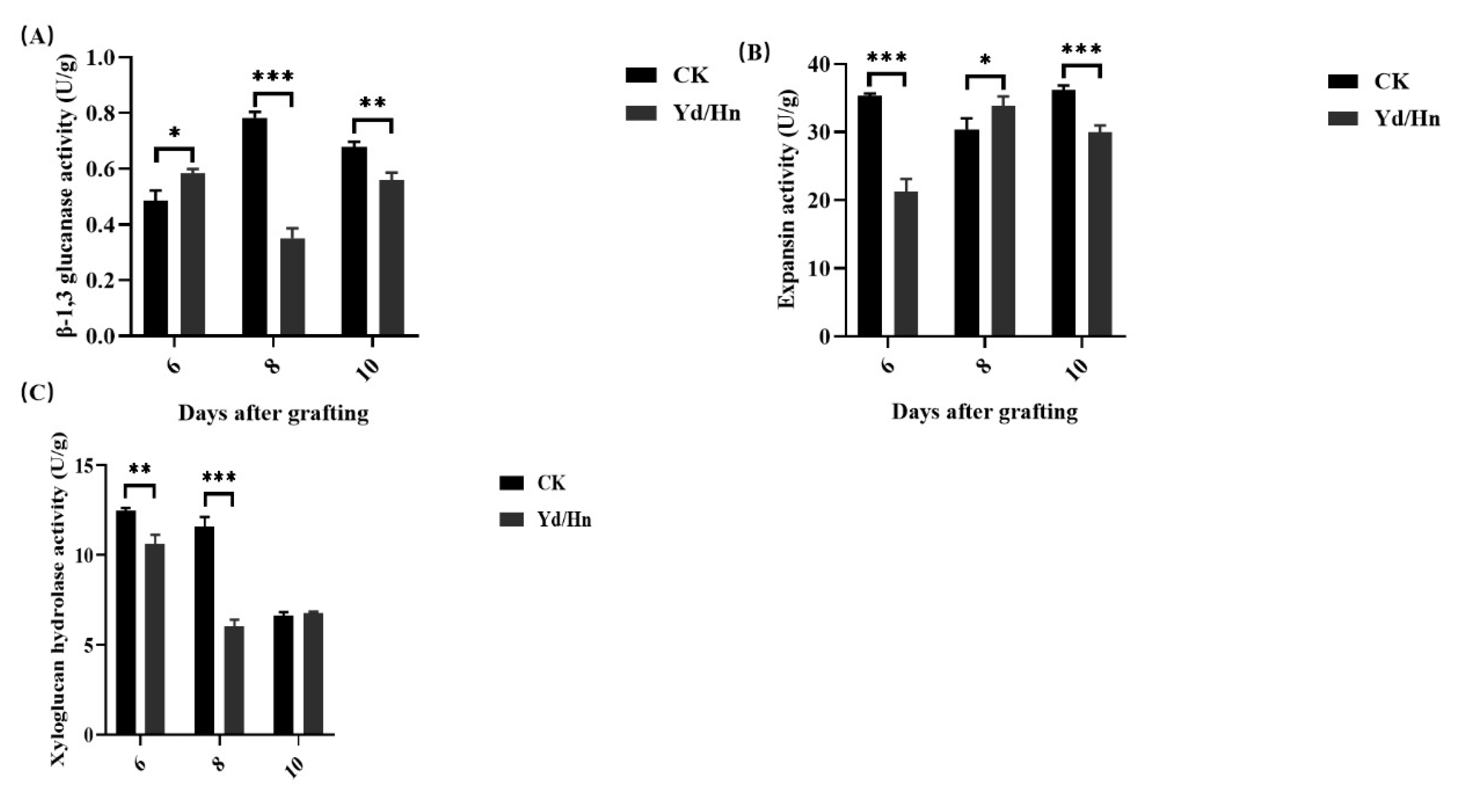

3.5. Measurement of Enzyme Activities of Watermelon Graft Union During the Grafting Process

3.6. Total Soluble Sugar and Titratable Acid Content in the Grafting Junction Among Watermelon Seedlings and Grafted Seedlings

4. Discussion

5. Conclutions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmidt-Jeffris, R. A., Coffey, J. L., Miller, G., & Farfan, M. A. (2021). Residual Activity of Acaricides for Controlling Spider Mites in Watermelon and Their Impacts on Resident Predatory Mites. Journal of Economic Entomology, 114(2), 818-827.

- Gimode, W., Bao, K., Fei, Z., & McGregor, C. (2021). QTL associated with gummy stem blight resistance in watermelon. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 134(2), 573-584.

- Gusmini, G., Rivera-Burgos, L. A., & Wehner, T. C. (2017). Inheritance of resistance to gummy stem blight in watermelon. HortScience, 52(11), 1477-1482.

- Bantis, F., & Koukounaras, A. (2023). Ascophyllum nodosum and Silicon-Based Biostimulants Differentially Affect the Physiology and Growth of Watermelon Transplants under Abiotic Stress Factors: The Case of Salinity. Plants, 12(3), 433.

- Ye, L., Zhao, X., Bao, E. C., Cao, K., & Zou, Z. R. (2019). Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Watermelon Growth, Elemental Uptake, Antioxidant, and Photosystem II Activities and Stress-Response Gene Expressions Under Salinity-Alkalinity Stresses. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 863.

- Nabwire, S., Wakholi, C., Faqeerzada, M. A., Arief, M. A. A., Kim, M. S., Baek, I., & Cho, B. K. (2022). Estimation of Cold Stress, Plant Age, and Number of Leaves in Watermelon Plants Using Image Analysis. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 847225.

- Ding, C. Q., Chen, C. T., Su, N., Lyu, W. H., Yang, J. H., Hu, Z. Y., & Zhang, M. F. (2021). Identification and characterization of a natural SNP variant in ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE gene associated with cold stress tolerance in watermelon. Plant Science, 304, 110735.

- Hamurcu, M., Khan, M. K., Pandey, A., Ozdemir, C., Avsaroglu, Z. Z., Elbasan, F., Omay, A. H., & Gezgin, S. (2020). Nitric oxide regulates watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) responses to drought stress. 3 Biotech, 10(11), 494.

- Li, H., Mo, Y. L., Cui, Q., Yang, X. Z., Guo, Y. L., Wei, C. H., Yang, J. Q., Zhang, Y., Ma, J. Q., & Zhang, X. (2019). Transcriptomic and physiological analyses reveal drought adaptation strategies in drought-tolerant and -susceptible watermelon genotypes. Plant Science, 278, 32-43.

- He, N., Umer, M. J., Yuan, P. L., Wang, W. W., Zhu, H. J., Zhao, S. J., Lu, X. Q., Xing, Y., Gong, C. S., Liu, W. G., & Sun, X. W. (2022). Expression dynamics of metabolites in diploid and triploid watermelon in response to flooding. PeerJ, 13814.

- He, N., Umer, M. J., Yuan, P., Wang, W. W., Zhu, H. J., Lu, X. Q., Xing, Y., Gong, C. S., Batool, R., Sun, X. W., & Liu, W. G. (2023). Physiological, biochemical, and metabolic changes in diploid and triploid watermelon leaves during flooding. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1108795.

- Yetisir, H., & Sari, N. (2003). Effect of different rootstocks on plant growth, yield, and quality of watermelon. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture, 43, 1269-1274.

- King, S. R., Davis, A. R., Liu, W. G., & Levi, A. (2008). Grafting for disease resistance. HortScience, 43, 1673-1676.

- Kousik, C. S., Mandal, M., & Hassell, R. (2018). Powdery mildew resistant rootstocks that impart tolerance to grafted susceptible watermelon scion seedlings. Plant Disease, 102(7), 1290-1298.

- Mahmud, I., Kousik, C., Hassell, R., Chowdhury, K., & Boroujerdi, A. F. (2015). NMR Spectroscopy Identifies Metabolites Translocated from Powdery Mildew Resistant Rootstocks to Susceptible Watermelon Scions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 63(36), 8083-8091.

- Huitrón-Ramírez, M. V., Huitrón-Ramírez, M. G., & Camacho-Ferre, F. (2009). Influence of grafted watermelon plant density on yield and quality in soil infested with Melon Necrotic Spot Virus. HortScience, 44(7), 1838-1841.

- Kousik, C. S., Donahoo, R. S., & Hassell, R. (2012). Resistance in watermelon rootstocks to crown rot caused by Phytophthora capsici. Crop Protection, 39, 18-25.

- Li, H., Guo, Y. L., Lan, Z. X., Xu, K., Chang, J. J., Ahammed, G. J., Ma, J. X., Wei, C. H., & Zhang, X. (2021). Methyl jasmonate mediates melatonin-induced cold tolerance of grafted watermelon plants. Horticulture Research, 8, 57.

- Guo, Y. L., Yan, J. Y., Su, Z. Z., Chang, J. J., Yang, J. Q., Wei, C. H., Zhang, Y., Ma, J. X., Zhang, X., & Li, H. (2021). Abscisic Acid Mediates Grafting-Induced Cold Tolerance of Watermelon via Interaction With Melatonin and Methyl Jasmonate. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 785317.

- Shin, Y. K., Bhandari, S. R., & Lee, J. G. (2021). Monitoring of salinity, temperature, and drought stress in grafted watermelon seedlings using chlorophyll fluorescence. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 786309.

- Bikdeloo, M., Colla, G., Rouphael, Y., Hassandokht, M. R., Soltani, F., Soltani, F., Salehi, R., Kumar, P., & Cardarelli, M. (2021). Morphological and Physio-Biochemical Responses of Watermelon Grafted onto Rootstocks of Wild Watermelon [Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad] and Commercial Interspecific Cucurbita Hybrid to Drought Stress. Horticulturae, 7, 359.

- Yang, Y. J., Yu, L., Wang, L. P., & Guo, S. R. (2015). Bottle gourd rootstock-grafting promotes photosynthesis by regulating the stomata and non-stomata performances in leaves of watermelon seedlings under NaCl stress. Journal of Plant Physiology, 186-187, 50-58.

- Yang, Y. J., Lu, X. M., Yan, B., Li, B., Sun, J., Guo, S. R., & Tezuka, T. (2013). Bottle gourd rootstock-grafting affects nitrogen metabolism in NaCl-stressed watermelon leaves and enhances short-term salt tolerance. Journal of Plant Physiology, 170, 653-661.

- Bidabadi, S. S., Abolghasemi, R., & Zheng, S. J. (2018). Grafting of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus cv. Mahbubi) onto different squash rootstocks as a means to minimize cadmium toxicity. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 20, 730-738.

- Nawaz, M. A., Chen, C., Shireen, F., Zheng, Z. H., Jiao, Y. Y., Sohail, H., Sohail, M., Imtiaz, M., Ali, M. A., Huang, Y., & Bie, Z. L. (2018). Improving vanadium stress tolerance of watermelon by grafting onto bottle gourd and pumpkin rootstock. Plant Growth Regulation, 85, 41-56.

- Yang, Y. J., Wang, L. P., Tian, J., Li, J., Sun, J., He, L. Z., Guo, S. R., & Tezuka, T. (2012). Proteomic study participating the enhancement of growth and salt tolerance of bottle gourd rootstock-grafted watermelon seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 58, 54-65.

- Fallik, E., Alkalai-Tuvia, S., Chalupowicz, D., Popovsky-Sarid, S., & Zaaroor-Presman, M. (2019). Relationships between rootstock-scion combinations and growing regions on watermelon fruit quality. Agronomy, 9, 536.

- Melnyk, C. W. (2017). Plant grafting: Insights into tissue regeneration. Regeneration, 4, 3-14.

- Peña-Cortés, H., Fisahn, J., & Willmitzer, L. (1995). Signals involved in wound-induced proteinase inhibitor II gene expression in tomato and potato plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 92, 4106-4113.

- Oh, S., Park, S., & Han, K.-H. (2003). Transcriptional regulation of secondary growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany, 54, 2709-2722.

- Melnyk, C. W., Schuster, C., Leyser, O., & Meyerowitz, E. M. (2015). A developmental framework for graft formation and vascular reconnection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Current Biology, 25(11), 1306-1318.

- Parkinson, M., & Yeoman, M. M. (1982). Graft formation in cultured, explanted internodes. New Phytologist, 91(3), 711-719.

- Matsuoka, K., Sugawara, E., Aoki, R., Takuma, K., Terao-Morita, M., Satoh, S., & Asahina, M. (2016). Differential cellular control by cotyledon-derived phytohormones involved in graft reunion of Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Plant and Cell Physiology, 57(10), 2620-2631.

- Notaguchi, M., Kurotani, K. I., Sato, Y., Tabata, R., Kawakatsu, Y., Okayasu, K., Sawai, Y., Okada, R., Asahina, M., Ichihashi, Y., Shirasu, K., Suzuki, T., Niwa, M., & Higashiyama, T. (2020). Cell-cell adhesion in plant grafting is facilitated by β-1,4-glucanases. Science, 369(6501), 698-702.

- Soteriou, G. A., Kyriacou, M. C., Siomos, A. S., & Gerasopoulos, D. (2014). Evolution of watermelon fruit physicochemical and phytochemical composition during ripening as affected by grafting. Food Chemistry, 165, 282-289.

- Huitrón, M. V., Díaz, M., Diánez, F., & Camacho, F. (2007). The effect of various rootstocks on triploid watermelon yield and quality. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment, 5(2), 344-348.

- Fredes, A., Roselló, S., Beltrán, J., Cebolla-Cornejo, J., Pérez-de-Castro, A., Gisbert, C., & Picó, M. B. (2017). Fruit quality assessment of watermelons grafted onto citron melon rootstock. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 97(9), 1646-1655.

- Çandır, E., Yetişir, H., Karaca, F., & Üstün, D. (2013). Phytochemical characteristics of grafted watermelon on different bottle gourds (Lagenaria siceraria) collected from the Mediterranean region of Turkey. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 37(3), 443-456.

- Fallik, E., & Ziv, C. (2020). How rootstock/scion combinations affect watermelon fruit quality after harvest? Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 100(7), 3275-3282.

- Liu, C. J., Lin, W. G., Feng, C. R., Wu, X. S., Fu, X. H., Xiong, M., Bie, Z. L., & Huang, Y. (2021). A new grafting method for watermelon to inhibit rootstock regrowth and enhance scion growth. Agriculture, 11(5), 812.

- Yang, J., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., Zhu, Q., & Wang, W. (2001). Hormonal changes in the grains of rice subjected to water stress during grain filling. Plant Physiology, 127(1), 315-323.

- Pan, X. Q., Welti, R., & Wang, X. M. (2010). Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Nature Protocols, 5(6), 986-992.

- Ritte, G., Steup, M., Kossmann, J., & Lloyd, J. R. (2003). Determination of the starch-phosphorylating enzyme activity in plant extracts. Planta, 216(3), 798-801.

- Bradford, M. M., & Williams, W. L. (1976). New, rapid, sensitive method for protein determination. Federation Proceedings, 35(3), 274.

- Lee, E. J., Yoo, K. S., Jifon, J., & Patil, B. S. (2009). Characterization of short-day onion cultivars of three pungency levels with flavor precursors, free amino acid, sulfur, and sugar contents. Journal of Food Science, 74(4), C475-C480.

- Devi, P., DeVetter, L., Kraft, M., Shrestha, S., & Miles, C. (2022). Micrographic View of Graft Union Formation Between Watermelon Scion and Squash Rootstock. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 878289.

- Reeves, G., Tripathi, A., Singh, P., Jones, M. R. W., Nanda, A. K., Musseau, C., Craze, M., Bowden, S., Walker, J. F., Bentley, A. R., Melnyk, C. W., & Hibberd, J. M. (2022). Monocotyledonous plants graft at the embryonic root-shoot interface. Nature, 602, 280-286.

- López-Galarza, S., Batista, A. S., Pérez, D. M., Miquel, A., Baixauli, C., Pascual, B., Maroto, J. V., & Guardiola, J. L. (2004). Effects of grafting and cytokinin-induced fruit setting on colour and sugar-content traits in glasshouse-grown triploid watermelon. Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology, 79(6), 971-976.

- Khah, M. K. (2011). Effect of grafting on growth, performance, and yield of aubergine (Solanum melongena L.) in greenhouse and open-field. International Journal of Plant Production, 5(3), 359-366.

- Rouphael, Y., Cardarelli, M., & Colla, G. (2008). Yield, mineral composition, water relations, and water use efficiency of grafted miniwatermelon plants under deficit irrigation. HortScience, 43(4), 730-736.

- Bikdeloo, M., Colla, G., Rouphael, Y., Hassandokht, M. R., Soltani, F., Salehi, R., Kumar, P., & Cardarelli, M. (2021). Morphological and Physio-Biochemical Responses of Watermelon Grafted onto Rootstocks of Wild Watermelon [Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad] and Commercial Interspecific Cucurbita Hybrid to Drought Stress. Horticulturae, 7(3), 359.

- Huang, Y., Zhao, L. Q., Kong, Q. S., Cheng, F., Niu, M. L., Xie, J. J., Muhammad, A. N., & Bie, Z. L. (2016). Comprehensive Mineral Nutrition Analysis of Watermelon Grafted onto Two Different Rootstocks. Horticultural Plant Journal, 2(1), 105-113.

- Greenwood, M. S., Day, M. E., & Schatz, J. (2010). Separating the effects of tree size and meristem maturation on shoot development of grafted scions of red spruce (Picea rubens Sarg.). Tree Physiology, 30(4), 459-468.

- Nguyen, V. H., & Yen, C. R. (2018). Rootstock age and grafting season affect graft success and plant growth of papaya (Carica papaya L.) in greenhouse. Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, 78(1), 59-67.

- Yeoman, M. M., Kilpatrick, D. C., Miedzybrodzka, M. B., & Gould, A. R. (1978). Cellular interaction during graft formation in plants, a recognition phenomenon? Symposium of the Society for Experimental Biology, 32, 139-160.

- Ermel, F. F., Poëssel, J. L., Faurobert, M., & Catesson, A. M. (1997). Early scion/stock junction in compatible and incompatible pear/pear and pear/quince grafts: A histo-cytological study. Annals of Botany, 79(6), 505-515.

- Yang, S. J. (1987). Observation on histological and cellular events of inter-specific grafting (Impatiens walleriana/Impatiens olivieri). Acta Agriculturae Universitatis Pekinensis, 13(2), 359-366.

- Aloni, R. (1987). Differentiation of vascular tissues. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 38, 179-204.

- Aloni, R. (2001). Foliar and Axial Aspects of Vascular Differentiation: Hypotheses and Evidence. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 20(1), 22-34.

- Hooijdonk, V., Woolley, D. J., Warrington, I. J., & Tustin, D. S. (2010). Initial alteration of scion architecture by dwarfing apple rootstocks may involve shoot-root-shoot signalling by auxin, gibberellin, and cytokinin. Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology, 85(1), 59-65.

- Köse, C., & Güleryüz, M. (2006). Effects of auxins and cytokinins on graft union of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) New Zealand. Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science, 34(2), 145-150.

- Cookson, S. J., Clemente Moreno, M. J., Hevin, C., Nyamba Mendome, L. Z., Delrot, S., Trossat-Magnin, C., & Ollat, N. (2013). Graft union formation in grapevine induces transcriptional changes related to cell wall modification, wounding, hormone signalling, and secondary metabolism. Journal of Experimental Botany, 64(7), 2997-3008.

- Yang, Y. J., Wang, L. P., Tian, J., Li, J., Sun, J., He, L. Z., Guo, S. R., & Tezuka, T. (2012). Proteomic study participating in the enhancement of growth and salt tolerance of bottle gourd rootstock-grafted watermelon seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 58, 54-65.

- Song, Y., Ling, N., Ma, J. H., Wang, J. C., Zhu, C., Raza, W., Shen, Y. F., Huang, Q. W., & Shen, Q. R. (2016). Grafting resulted in a distinct proteomic profile of watermelon root exudates relative to the un-grafted watermelon and the rootstock plant. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 35(4), 778-791.

- Zhu, Y. L., Hu, S. W., Min, J. H., Zhao, Y. T., Yu, H. Q., Irfan, M., & Xu, C.

- (2024). Transcriptomic analysis provides insight into the function of CmGH9B3, a key gene of β-1,4-glucanase, during the graft union healing of oriental melon scion grafted onto squash rootstock. Biotechnology Journal, 19(4), e2400006.

- Petropoulos, S. A., Khah, E. M., & Passam, H. C. (2012). Evaluation of rootstocks for watermelon grafting with reference to plant development, yield, and fruit quality. International Journal of Plant Production, 6(3), 481-492.

- Turhan, A., Ozman, N., Kuscu, H., Serbeci, M. S., & Seniz, V. (2012). Influence of rootstocks on yield and fruit characteristics and quality of watermelon. Horticultural Environment and Biotechnology, 53(3), 336-341.

- Davis, A. R., & Perkins-Veazie, P. (2005). Rootstock effects on plant vigor and watermelon fruit quality. Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report, 28-29, 39-42.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).