Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

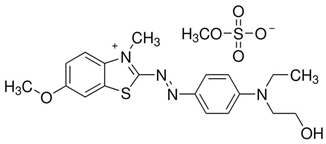

| Parameters | Characteristic |

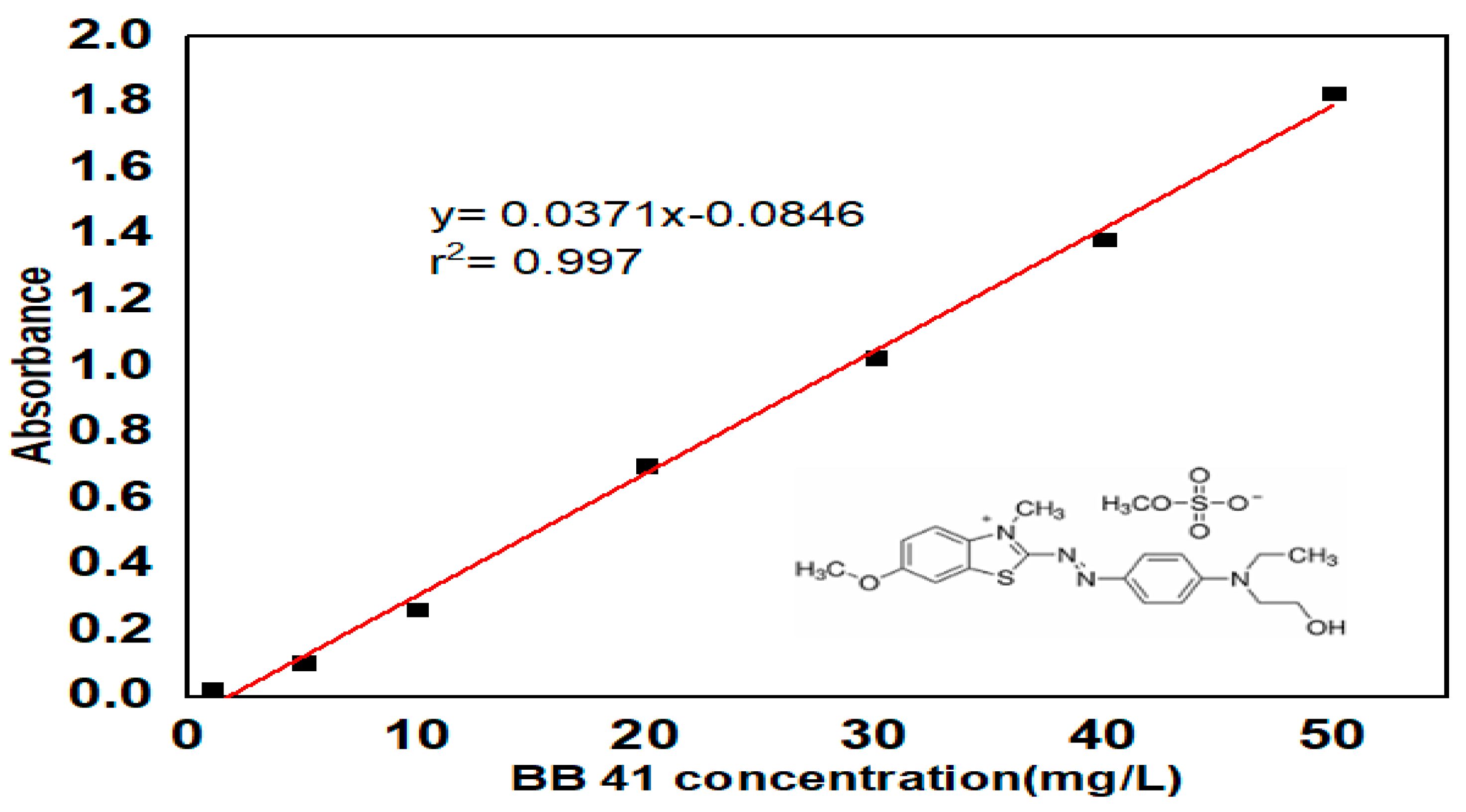

| Chemical name | Basic Blue 41 |

| Apparent color | Blue |

| Chemical formula | C20H26N4O6S2 |

| Molecular weight | 482.57 g-1 mol |

| λmax | 617 nm |

| Chemical structure |  |

2.2. Synthesis of Fe3O4-HTM Composite

2.3. Characterizations of -TM Composite

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

2.5. Experimental Design Using BBD

2.6. Real textile Wastewater Sample

2.7. Desorption and Regeneration Study

3. Result and Discussion

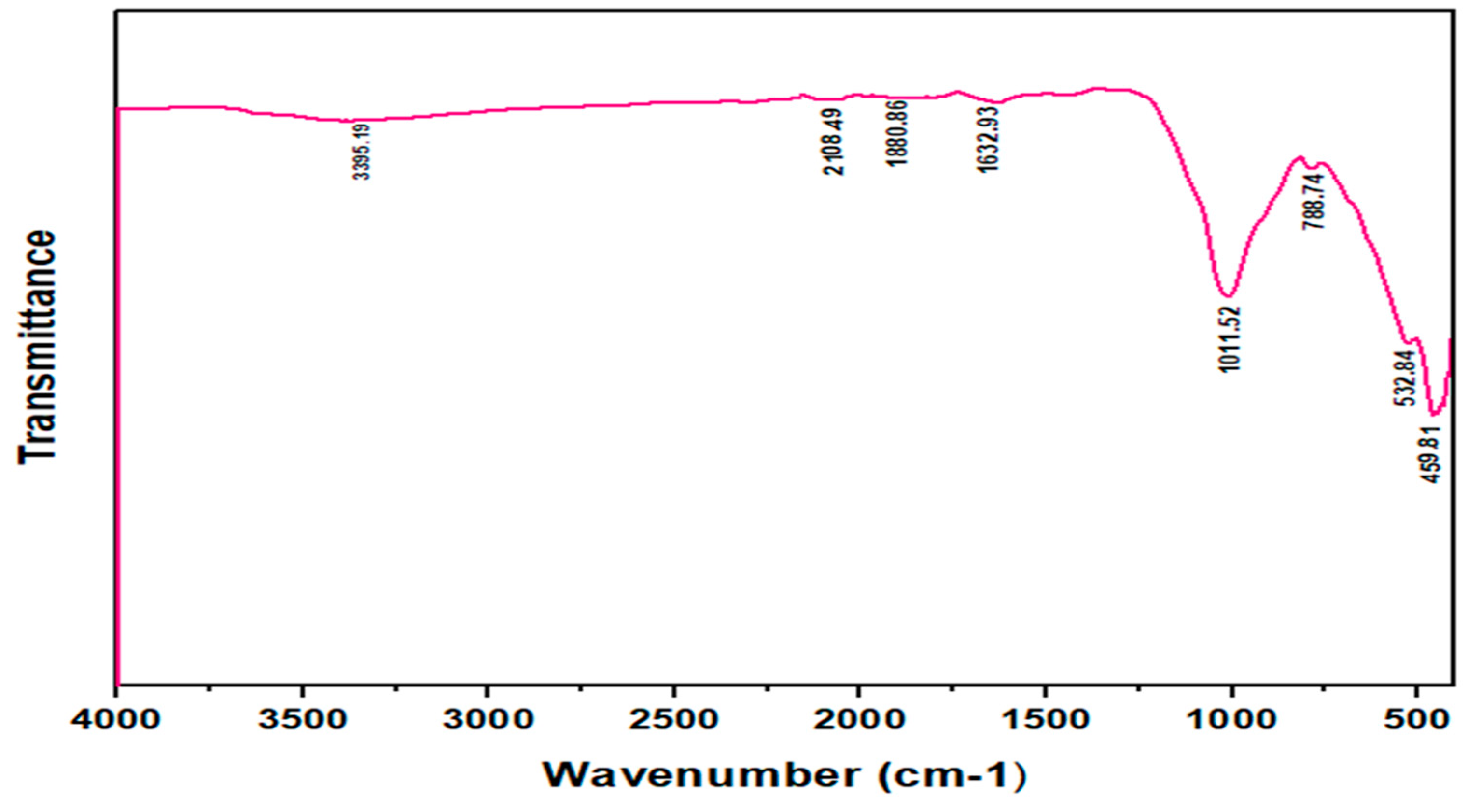

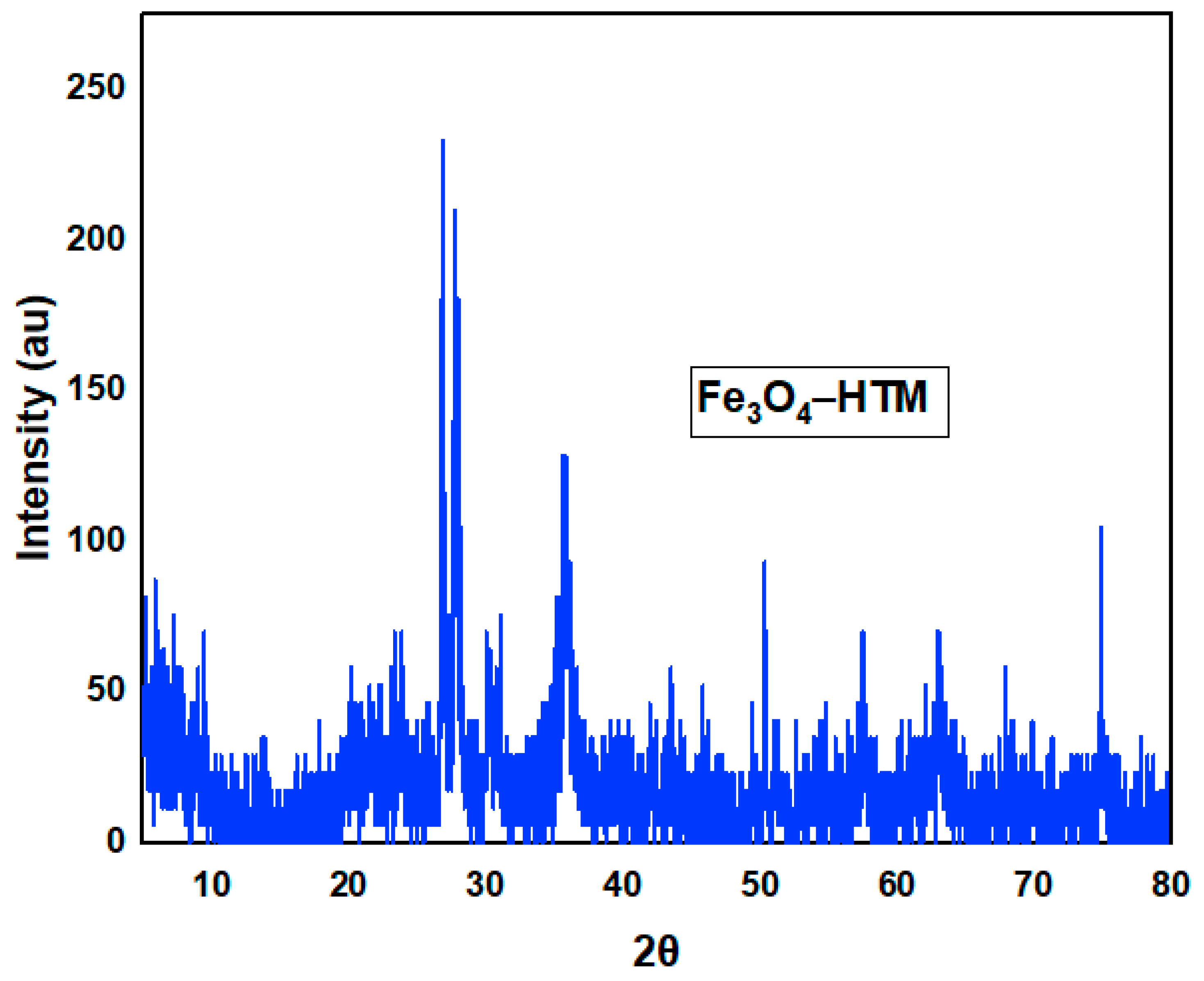

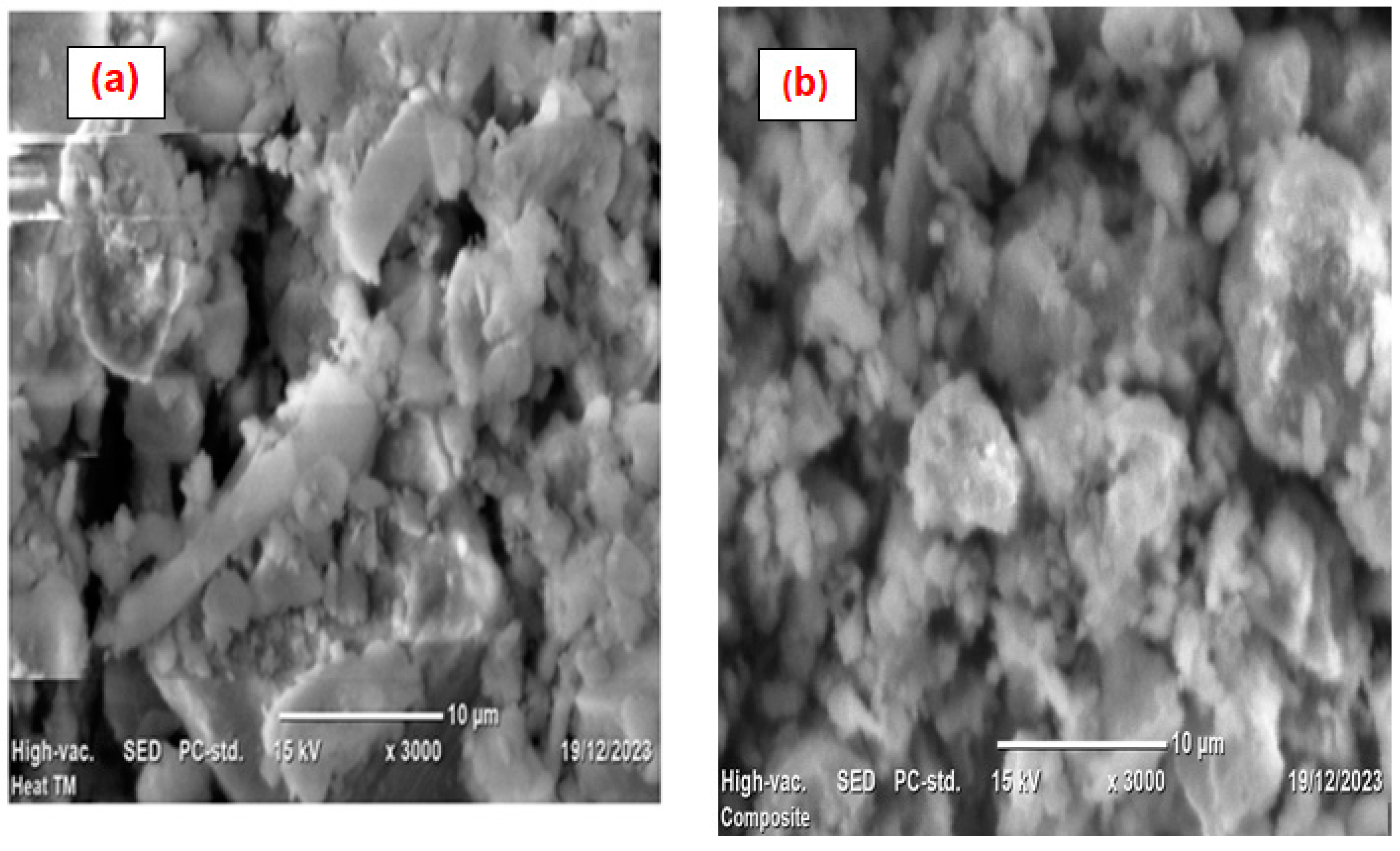

3.1. Characterization of ––HTM Composite

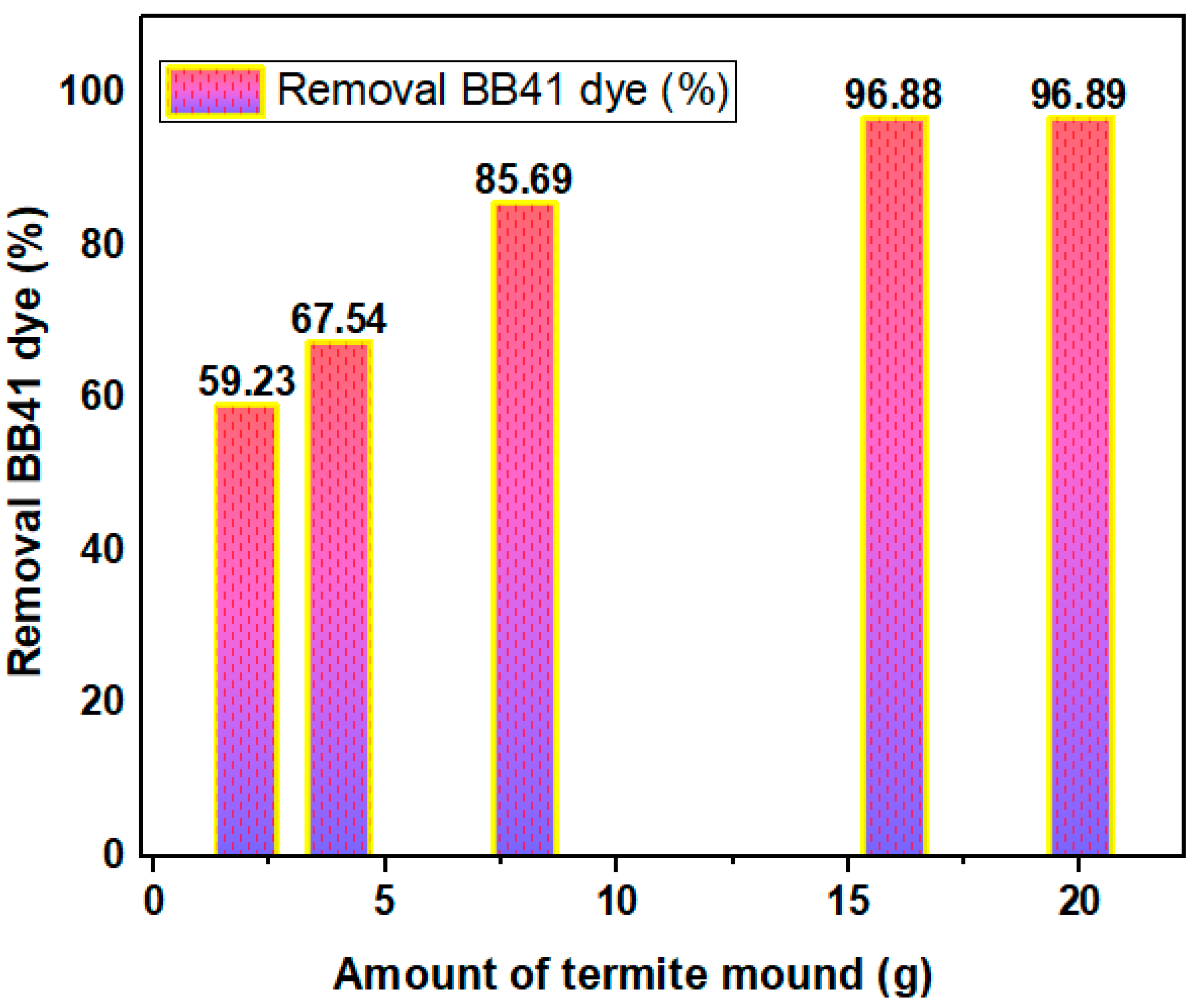

3.2. Effect of HTM Amount on Preparation of –HTM Composite

3.3. Magnetization Property

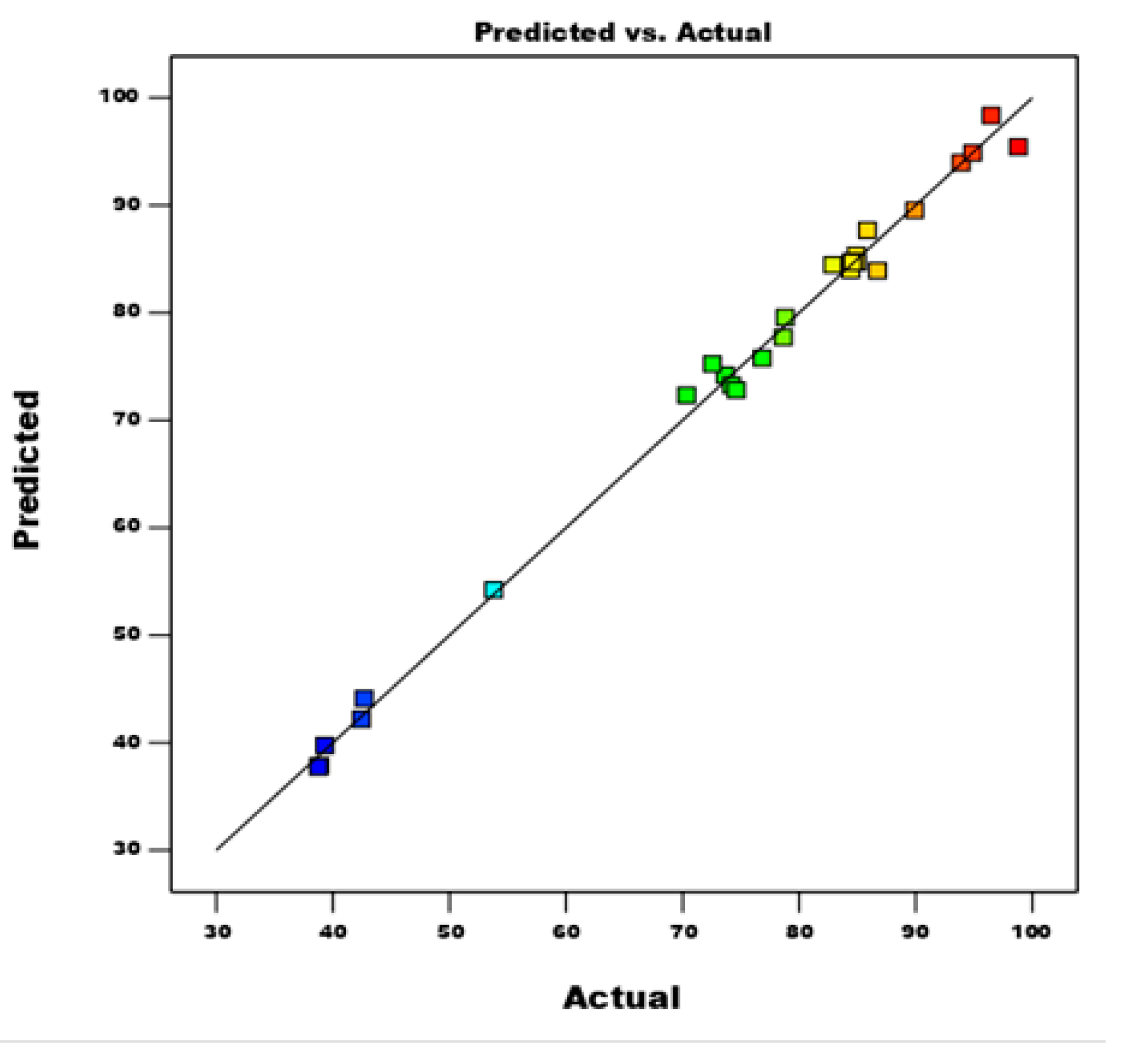

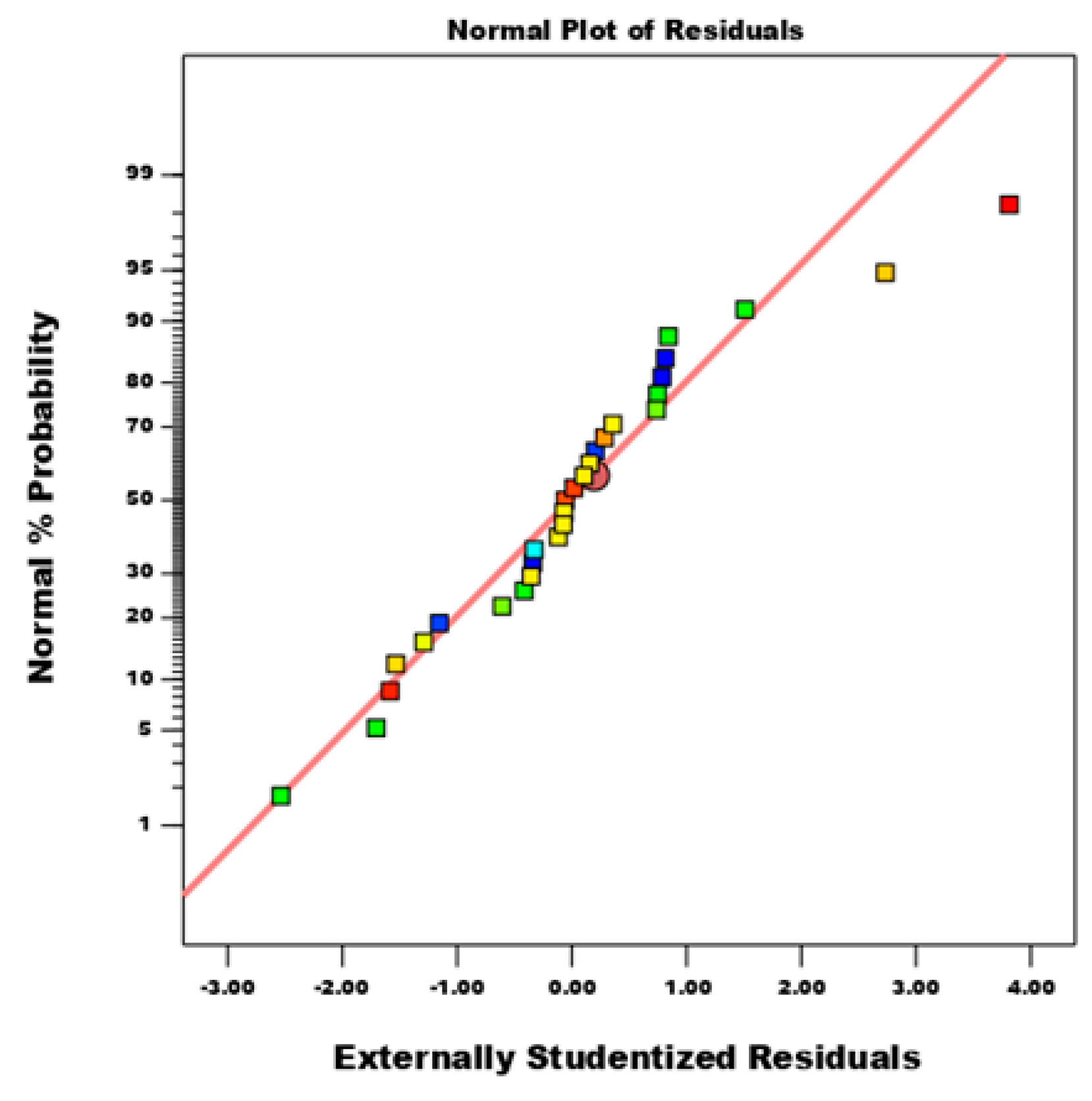

3.4. Development of BBD Model Equation and Statistical Analysis

3.4.1. Significance Level of Model Terms

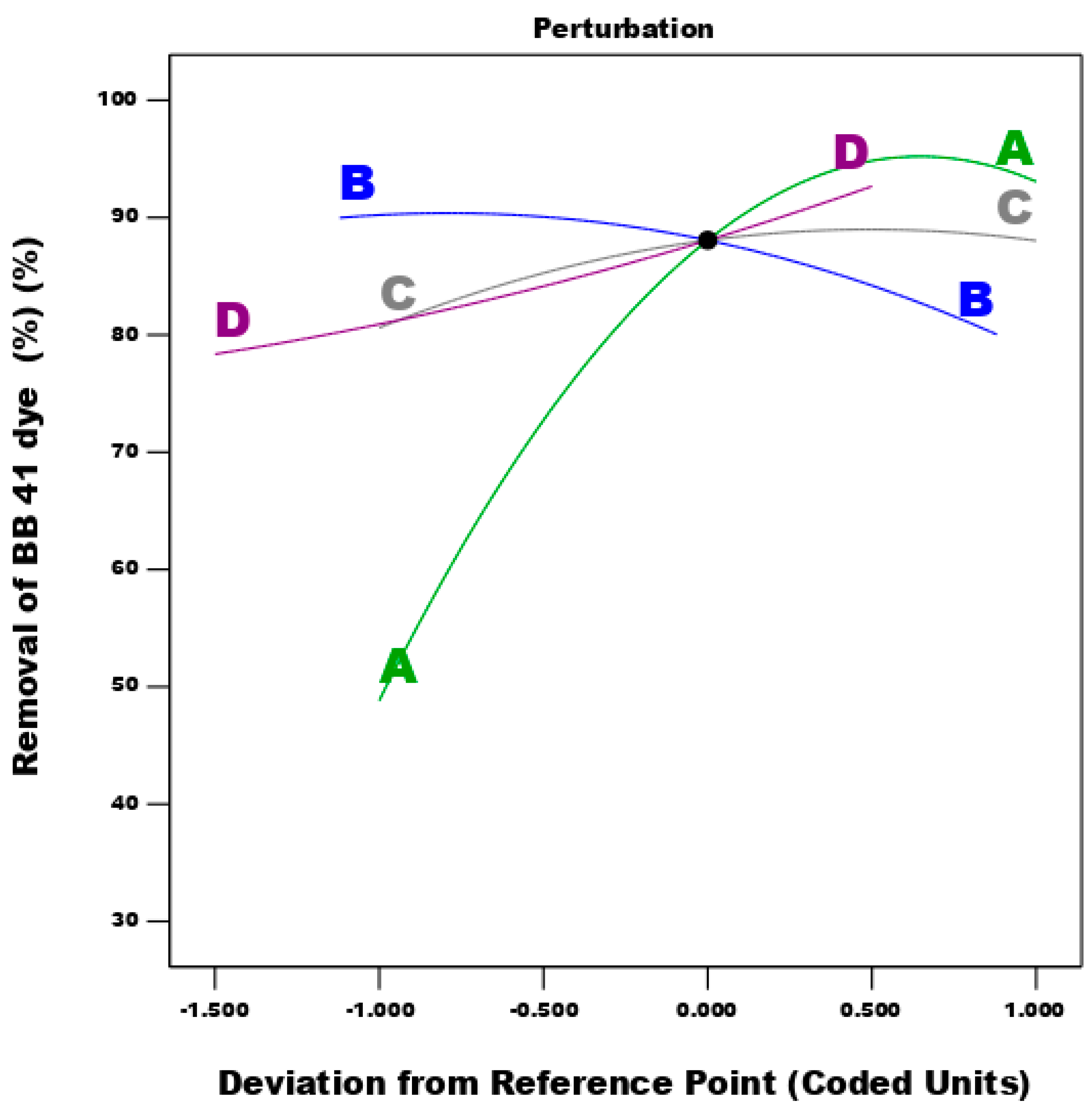

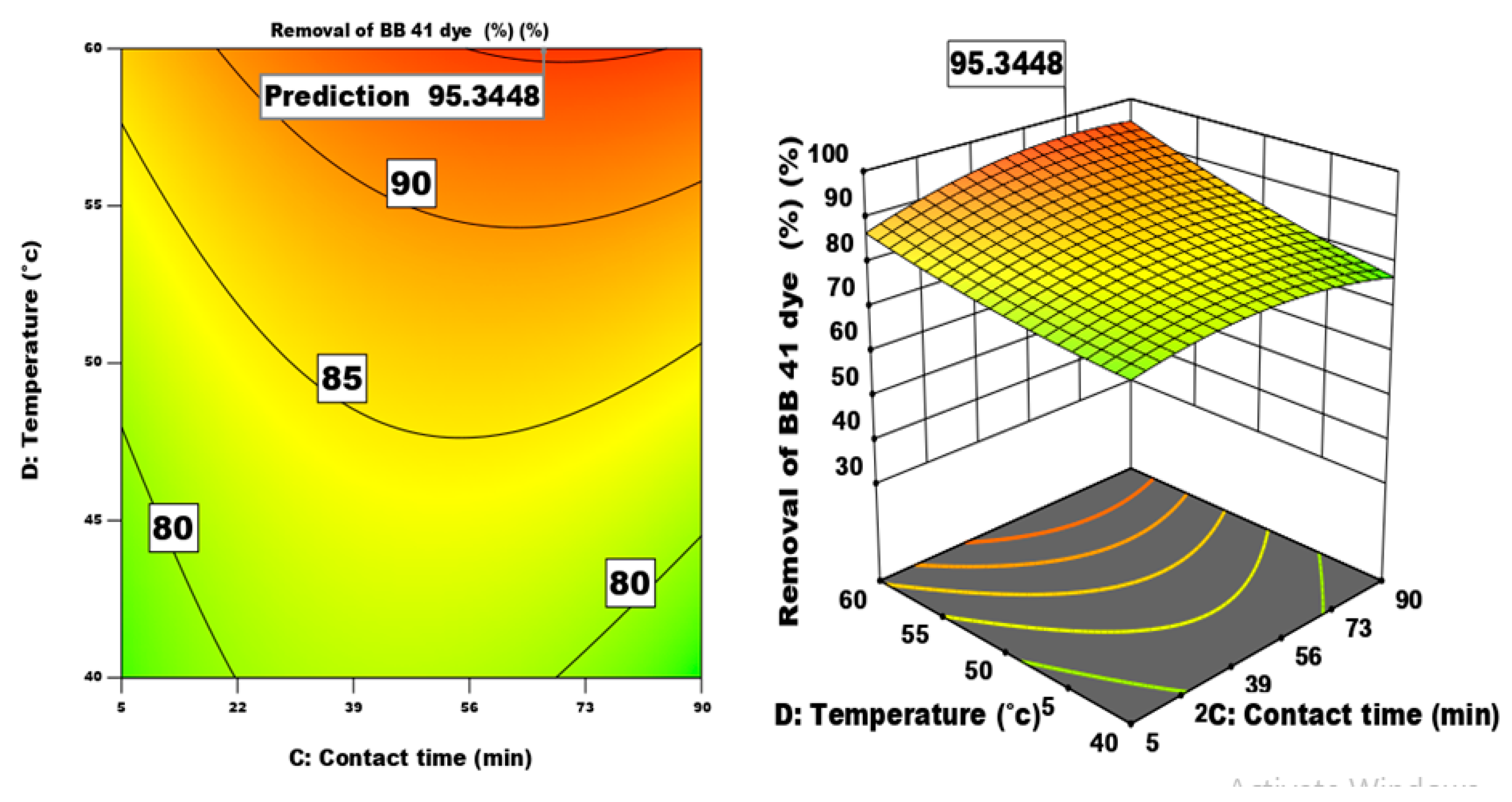

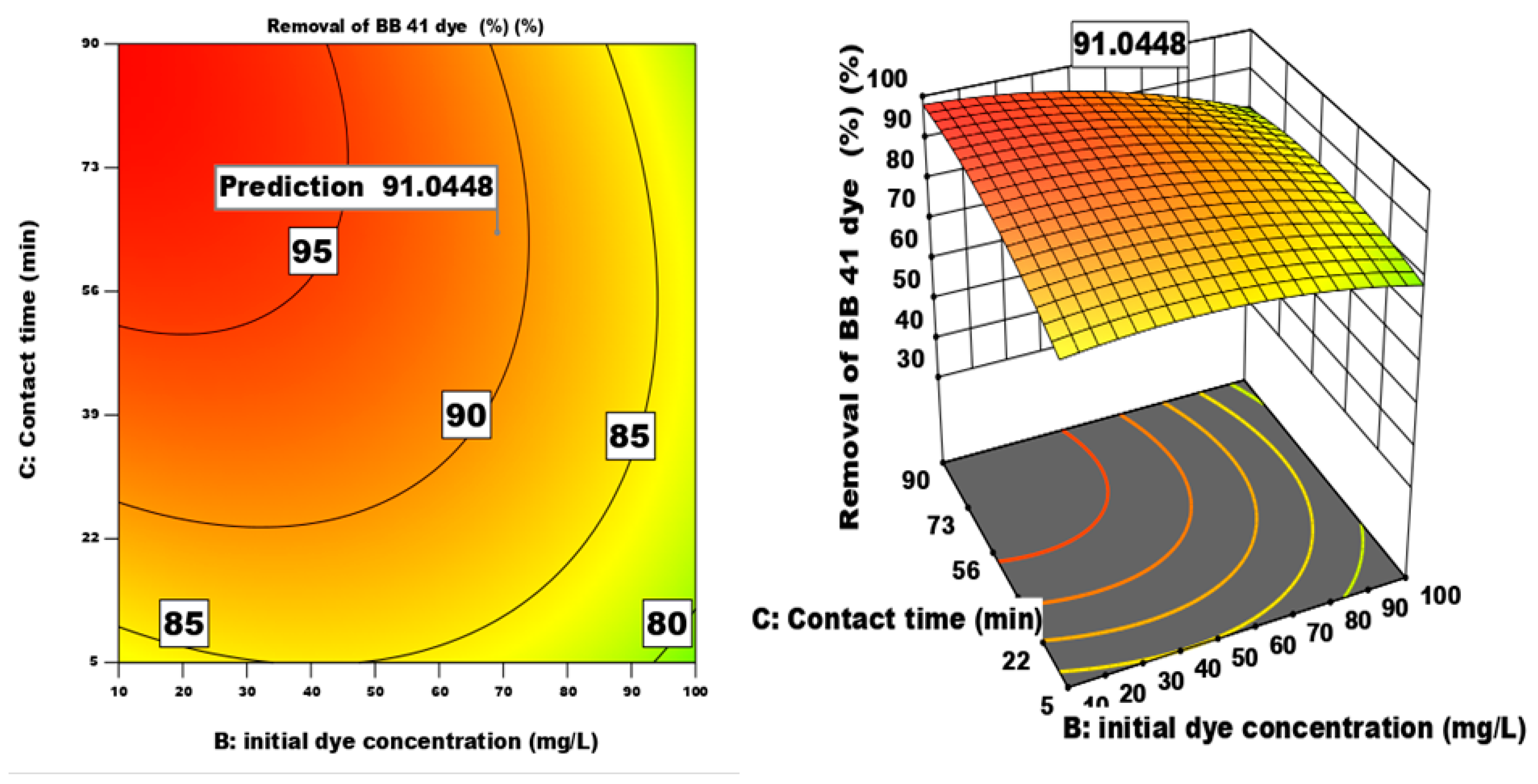

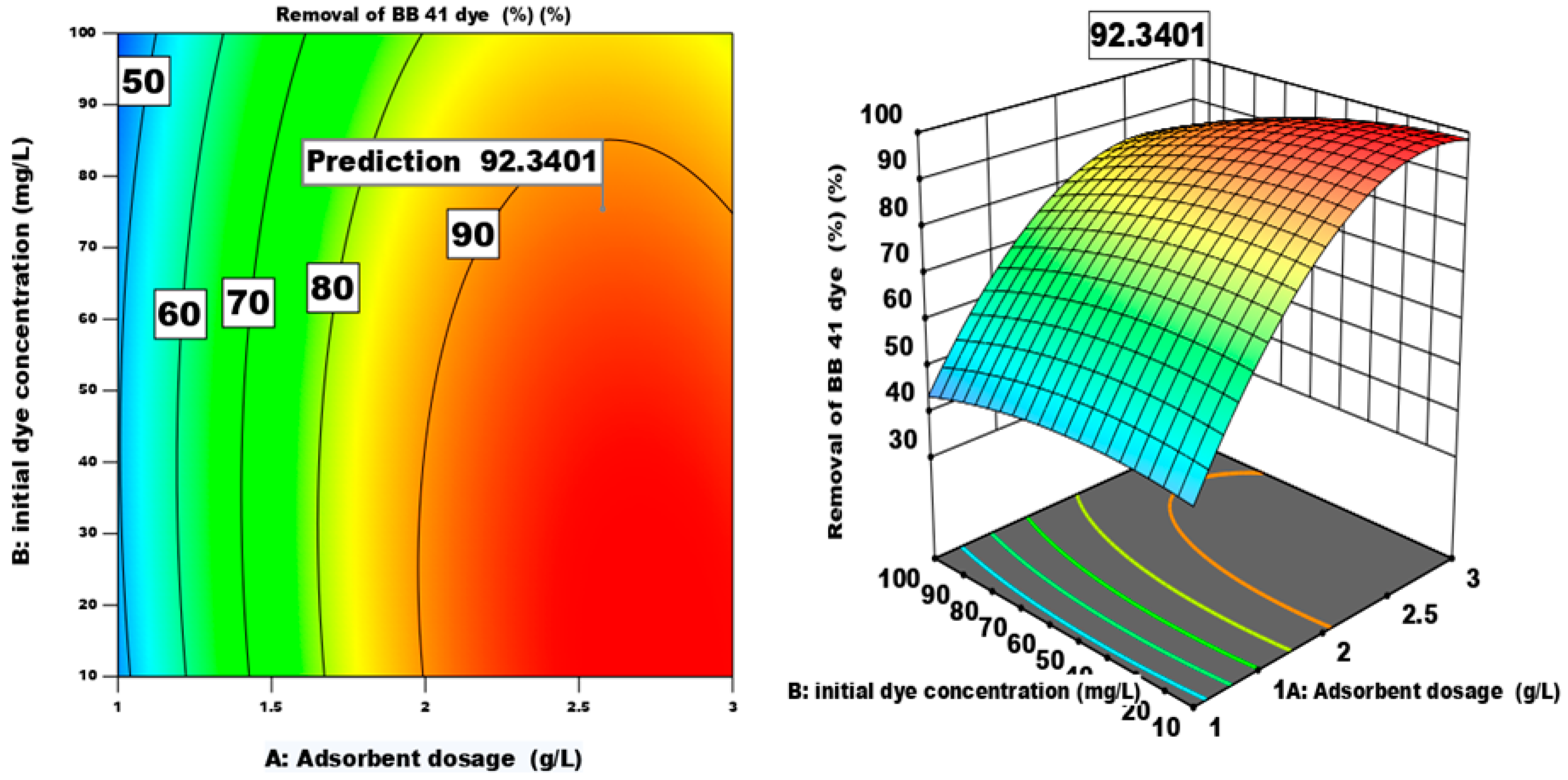

3.4.2. The Effect of of Different Factors and Their Interactions on the Process of Dye Adsorption

3.4.3. Process Parameters Optimization and Model Validation

3.5. Application in Real Textile Waste Water

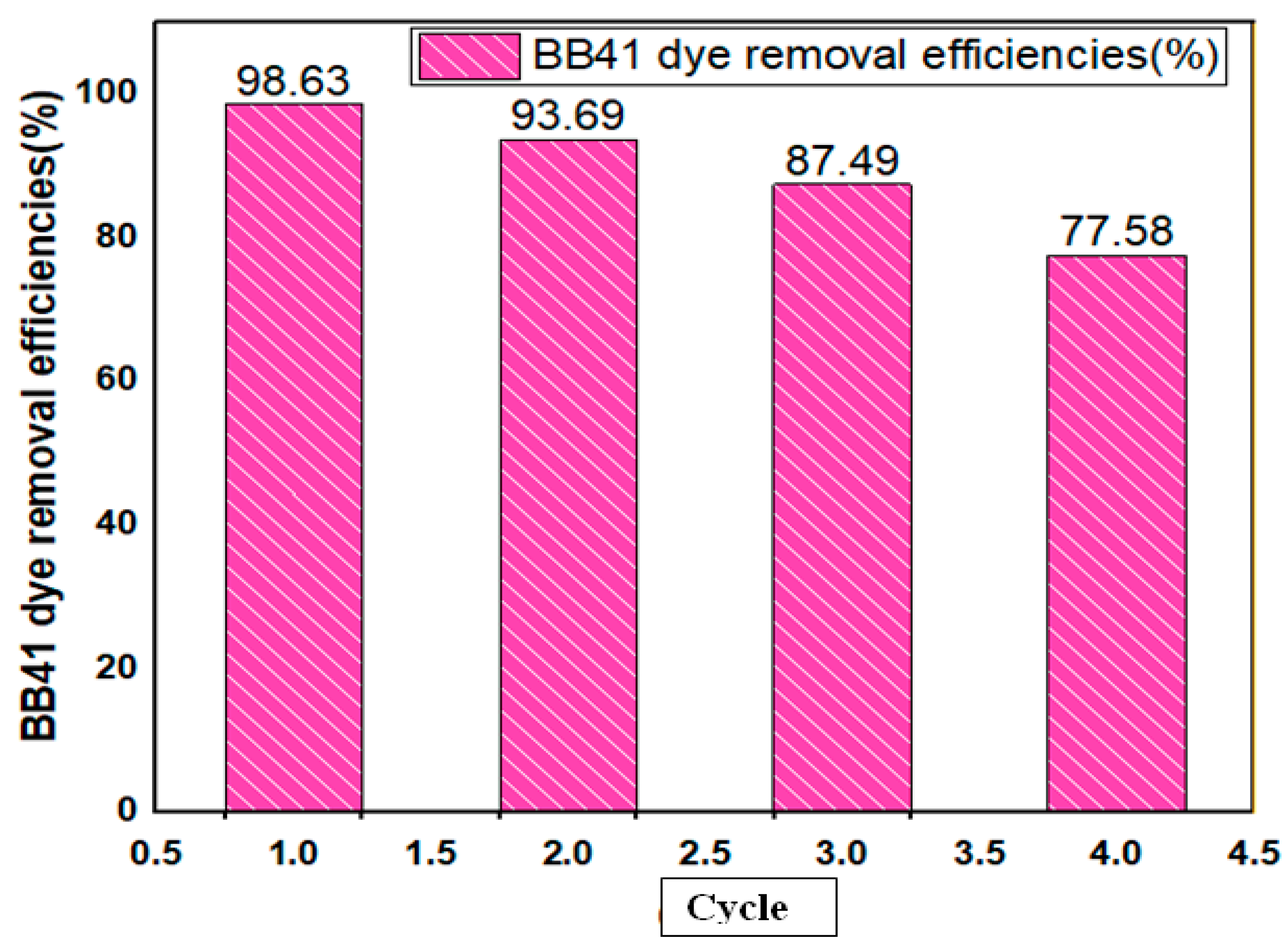

3.6. Reusability of Composite

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Recent Advances for Dyes Removal Using Novel Adsorbents: A Review. Environmental Pollution 2019, 252, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsami, S.; Mohamadizaniani, M.; Sarrafzadeh, M.-H.; Rene, E.R.; Firoozbahr, M. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Dye-Containing Wastewater from Textile Industries: Overview and Perspectives. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2020, 143, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, R.; Thirunavukkarasu, A.; Sathya, A.B.; Sivashankar, R. Magnetic Materials and Magnetic Separation of Dyes from Aqueous Solutions: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2021, 19, 1275–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashaye, T. The Physico-Chemical Studies of Wastewater in Hawassa Textile Industry. J Environ Anal Chem 2015, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, A.K.; Gebremedhin, S.; Ayele, B. Effects of Bahir Dar Textile Factory Effluents on the Water Quality of the Head Waters of Blue Nile River, Ethiopia. International Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellis, B.; Fávaro-Polonio, C.Z.; Pamphile, J.A.; Polonio, J.C. Effects of Textile Dyes on Health and the Environment and Bioremediation Potential of Living Organisms. Biotechnology Research and Innovation 2019, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, T.A.; Abdelrahman, M.S.; Rehan, M. Textile Dyeing Industry: Environmental Impacts and Remediation. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 3803–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Mu, B.; Yang, Y. Feasibility of Industrial-Scale Treatment of Dye Wastewater via Bio-Adsorption Technology. Bioresource Technology 2019, 277, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solayman, H.M.; Hossen, Md.A.; Abd Aziz, A.; Yahya, N.Y.; Leong, K.H.; Sim, L.C.; Monir, M.U.; Zoh, K.-D. Performance Evaluation of Dye Wastewater Treatment Technologies: A Review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 109610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.X.-H.; Low, L.W.; Teng, T.T.; Wong, Y.S. Combination and Hybridisation of Treatments in Dye Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2016, 4, 3618–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheresan, V.; Kansedo, J.; Lau, S.Y. Efficiency of Various Recent Wastewater Dye Removal Methods: A Review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2018, 6, 4676–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkadokula, N.Y.; Kola, A.K.; Naz, I.; Saroj, D. A Review on Advanced Physico-Chemical and Biological Textile Dye Wastewater Treatment Techniques. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2020, 19, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gisi, S.; Lofrano, G.; Grassi, M.; Notarnicola, M. Characteristics and Adsorption Capacities of Low-Cost Sorbents for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2016, 9, 10–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Iqbal, M.J.; Hussain, M. A State-of-the-Art Review on Wastewater Treatment Techniques: The Effectiveness of Adsorption Method. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 9050–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosavi, S.; Lai, C.W.; Gan, S.; Zamiri, G.; Akbarzadeh Pivehzhani, O.; Johan, M.R. Application of Efficient Magnetic Particles and Activated Carbon for Dye Removal from Wastewater. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20684–20697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, K.; Shezad, N.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Akhtar, F.; Jamil, F.; Shafique, S.; Park, Y.-K.; Hussain, M. A Review on Activated Carbon Modifications for the Treatment of Wastewater Containing Anionic Dyes. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. An Overview of Dye Removal via Activated Carbon Adsorption Process. Desalination and Water Treatment 2010, 19, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Yushin, G. Review of Nanostructured Carbon Materials for Electrochemical Capacitor Applications: Advantages and Limitations of Activated Carbon, Carbide-derived Carbon, Zeolite-templated Carbon, Carbon Aerogels, Carbon Nanotubes, Onion-like Carbon, and Graphene. WIREs Energy & Environment 2014, 3, 424–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fufa, F.; Alemayehu, E.; Lennartz, B. Sorptive Removal of Arsenate Using Termite Mound. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 132, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, A.S.; Azeez, T.M.; Babatunde, E.O. Titania-Termite Hill Composite as a Heterogeneous Catalyst: Preparation, Characterization, and Performance in Transesterification of Waste Frying Oil. International Journal of Chemical Reactor Engineering 2020, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apori, S.O.; Murongo, M.; Hanyabui, E.; Atiah, K.; Byalebeka, J. Potential of Termite Mounds and Its Surrounding Soils as Soil Amendments in Smallholder Farms in Central Uganda. BMC Res Notes 2020, 13, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fufa, F. Experimental Evaluation of Activated Termite Mound for Fluoride Adsorption. IOSR 2016, 10, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdus-Salam, N.; Itiola, A.D. Potential Application of Termite Mound for Adsorption and Removal of Pb(II) from Aqueous Solutions. J IRAN CHEM SOC 2012, 9, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, B.R.; Reis, J.O.M.; Rezende, E.I.P.; Mangrich, A.S.; Wisniewski, A.; Dick, D.P.; Romão, L.P.C. Application of Termite Nest for Adsorption of Cr(VI). Journal of Environmental Management 2013, 129, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fufa, F. Experimental Evaluation of Activated Termite Mound for Fluoride Adsorption. IOSR 2016, 10, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, A.S.; Bello, K.A.; Azeez, T.M. Photocatalytic Degradation of an Anionic Dye in Aqueous Solution by Visible Light Responsive Zinc Oxide-Termite Hill Composite. Reac Kinet Mech Cat 2020, 131, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shi, C.; Wang, L.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.-J. Rational Design, Synthesis, Adsorption Principles and Applications of Metal Oxide Adsorbents: A Review. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 4790–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, K.Q.; Barzinjy, A.A.; Hamad, S.M. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Preparation Methods, Functions, Adsorption and Coagulation/Flocculation in Wastewater Treatment. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 2022, 17, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Cong, H. Preparation, Surface Functionalization and Application of Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 281, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A.; Bogale, F.M.; Aragaw, B.A. Iron-Based Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment: A Review on Synthesis Methods, Applications, and Removal Mechanisms. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2021, 25, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhoo, A.; Sillanpää, M. Magnetic Nanoadsorbents for Micropollutant Removal in Real Water Treatment: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2021, 19, 4393–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, D.; Agrawal, D.C. Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles under Oxidizing Environment and Their Stabilization in Aqueous and Non-Aqueous Media. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2007, 308, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.C.; Bruns, R.E.; Ferreira, H.S.; Matos, G.D.; David, J.M.; Brandão, G.C.; Da Silva, E.G.P.; Portugal, L.A.; Dos Reis, P.S.; Souza, A.S.; et al. Box-Behnken Design: An Alternative for the Optimization of Analytical Methods. Analytica Chimica Acta 2007, 597, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayanda, O.S.; Odo, E.A.; Malomo, D.; Sodeinde, K.O.; Lawal, O.S.; Ebenezer, O.T.; Nelana, S.M.; Naidoo, E.B. Accelerated Decolorization of Congo Red by Powdered Termite Mound. CLEAN Soil Air Water 2017, 45, 1700537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Ahammed, M.M. Clay-Moringa Seedcake Composite for Removal of Cationic and Anionic Dyes. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C. Magnetic Mesoporous Clay Adsorbent: Preparation, Characterization and Adsorption Capacity for Atrazine. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2014, 194, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, T.; Toprak, M.S.; Baykal, A.; Kavas, H.; Köseoğlu, Y.; Aktaş, B. Synthesis of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles at 100°C and Its Magnetic Characterization. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2009, 472, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, T.; Munandar, A.; Mawaddah, N.; Syamsuddin Wisnubroto, M.; Siregar, P.M.S.B.N.; Palapa, N.R.; Lesbani, A.; Wibowo, Y.G. Synthesis and Characterization of Montmorillonite – Mixed Metal Oxide Composite and Its Adsorption Performance for Anionic and Cationic Dyes Removal. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2023, 147, 110231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.; Benamor, A. Magnetic Iron Oxide Kaolinite Nanocomposite for Effective Removal of Congo Red Dye: Adsorption, Kinetics, and Thermodynamics Studies. Water Conserv Sci Eng 2023, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmani, Y.; Mobarak, M.; Oukhrib, R.; Dehbi, A.; Mohsine, A.; Lamhasni, T.; Tahri, Y.; Ahlafi, H.; Abouarnadasse, S.; Lima, E.C.; et al. Adsorption of Phenol by a Moroccan Clay/ Hematite Composite: Experimental Studies and Statistical Physical Modeling. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 386, 122508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Aydin, M.E.; Beduk, F.; Ulvi, A. Removal of Antibiotics from Aqueous Solution by Using Magnetic Fe3O4/Red Mud-Nanoparticles. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 670, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.K.; Aggarwal, I.; Kumar, H.; Prasad, L.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, A.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Van Thuan, D.; Mishra, V. Magnetite Nanoparticles as Sorbents for Dye Removal: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2021, 19, 2487–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fufa, F.; Alemayehu, E.; Lennartz, B. Sorptive Removal of Arsenate Using Termite Mound. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 132, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Lu, D.; Gao, X. Optimization of Mixture Proportions by Statistical Experimental Design Using Response Surface Method - A Review. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 36, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, D.; Boyacı, İ.H. Modeling and Optimization I: Usability of Response Surface Methodology. Journal of Food Engineering 2007, 78, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, S.; Shojaei, S. Optimization of Process Conditions in Wastewater Degradation Process. In Soft Computing Techniques in Solid Waste and Wastewater Management; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 381–392. ISBN 978-0-12-824463-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zarezadeh-Mehrizi, M.; Badiei, A. Highly Efficient Removal of Basic Blue 41 with Nanoporous Silica. Water Resources and Industry 2014, 5, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbal, F. Adsorption of Basic Dyes from Aqueous Solution onto Pumice Powder. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2005, 286, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Santelli, R.E.; Oliveira, E.P.; Villar, L.S.; Escaleira, L.A. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) as a Tool for Optimization in Analytical Chemistry. Talanta 2008, 76, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Name | Units | -1 | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Dosage | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| B | Concentration | 10 | 55 | 100 | |

| C | Temperature | 40 | 50 | 60 | |

| D | Time | Min | 5 | 47.5 | 90 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Response 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run | A:–HTM dosage | B:initial BB 41 dye concentration | C:Contact time | D:Temperature | % BB 41 dye removal by –HTM | |

| min | ||||||

| Exp. | Pred. | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 100 | 5 | 50 | 74.21 | 73.27 |

| 2 | 2 | 55 | 90 | 40 | 76.83 | 75.77 |

| 3 | 1 | 55 | 47.5 | 60 | 53.8 | 54.22 |

| 4 | 2 | 10 | 90 | 50 | 85.86 | 87.68 |

| 5 | 3 | 55 | 5 | 50 | 86.72 | 83.91 |

| 6 | 2 | 55 | 47.5 | 50 | 84.57 | 84.70 |

| 7 | 2 | 100 | 47.5 | 60 | 84.43 | 83.97 |

| 8 | 2 | 55 | 47.5 | 50 | 84.98 | 84.70 |

| 9 | 2 | 100 | 90 | 50 | 74.6 | 72.80 |

| 10 | 2 | 10 | 47.5 | 60 | 98.81 | 95.43 |

| 11 | 1 | 55 | 5 | 50 | 38.78 | 37.76 |

| 12 | 3 | 10 | 47.5 | 50 | 93.89 | 93.96 |

| 13 | 1 | 10 | 47.5 | 50 | 42.46 | 42.20 |

| 14 | 2 | 55 | 47.5 | 50 | 84.58 | 84.70 |

| 15 | 2 | 55 | 5 | 40 | 73.67 | 74.20 |

| 16 | 2 | 55 | 47.5 | 50 | 84.49 | 84.70 |

| 17 | 3 | 55 | 47.5 | 40 | 84.89 | 85.35 |

| 18 | 2 | 100 | 47.5 | 40 | 70.35 | 72.34 |

| 19 | 3 | 100 | 47.5 | 50 | 78.8 | 79.57 |

| 20 | 1 | 55 | 47.5 | 40 | 38.87 | 37.88 |

| 21 | 2 | 55 | 47.5 | 50 | 84.89 | 84.70 |

| 22 | 2 | 10 | 47.5 | 40 | 78.65 | 77.72 |

| 23 | 1 | 55 | 90 | 50 | 42.69 | 44.11 |

| 24 | 2 | 55 | 90 | 60 | 94.89 | 94.87 |

| 25 | 3 | 55 | 47.5 | 60 | 96.48 | 98.35 |

| 26 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 50 | 72.56 | 75.23 |

| 27 | 2 | 55 | 5 | 60 | 82.89 | 84.46 |

| 28 | 1 | 100 | 47.5 | 50 | 39.31 | 39.75 |

| 29 | 3 | 55 | 90 | 50 | 89.91 | 89.54 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Model Sum of Squares | ||||||

| Mean vs Total | 1.636E+05 | 1 | 1.636E+05 | |||

| Linear vs Mean | 7258.40 | 4 | 1814.60 | 19.58 | < 0.0001 | |

| 2FI vs Linear | 109.00 | 6 | 18.17 | 0.1546 | 0.9856 | |

| Quadratic vs 2FI | 2063.16 | 4 | 515.79 | 139.27 | < 0.0001 | Suggested |

| Cubic vs Quadratic | 45.74 | 8 | 5.72 | 5.61 | 0.0249 | Aliased |

| Residual | 6.11 | 6 | 1.02 | |||

| Total | 1.730E+05 | 29 | 5966.78 | |||

| Source | Std. Dev. | R² | Adjusted R² | Predicted R² | PRESS | remark |

| Model Summary Statistics | ||||||

| Linear | 9.63 | 0.7655 | 0.7264 | 0.6565 | 3257.00 | |

| 2FI | 10.84 | 0.7770 | 0.6530 | 0.368 | 5984.52 | |

| Quadratic | 1.92 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 297.86 | Suggested |

| Cubic | 1.01 | 0.9994 | 0.9970 | 0.9100 | 853.41 | Aliased |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9430.56 | 14 | 673.61 | 181.88 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| A-Adsorbent dosage | 6292.00 | 1 | 6292.00 | 1698.92 | < 0.0001 | |

| B-initial dye concentration | 212.77 | 1 | 212.77 | 57.45 | < 0.0001 | |

| C-Contact time | 107.70 | 1 | 107.70 | 29.08 | < 0.0001 | |

| D-Temperature | 645.92 | 1 | 645.92 | 174.41 | < 0.0001 | |

| AB | 35.64 | 1 | 35.64 | 9.62 | 0.0078 | |

| AC | 0.1296 | 1 | 0.1296 | 0.0350 | 0.8543 | |

| AD | 2.79 | 1 | 2.79 | 0.7530 | 0.4001 | |

| BC | 41.67 | 1 | 41.67 | 11.25 | 0.0047 | |

| BD | 9.24 | 1 | 9.24 | 2.50 | 0.1365 | |

| CD | 19.54 | 1 | 19.54 | 5.28 | 0.0376 | |

| A² | 1902.02 | 1 | 1902.02 | 513.57 | < 0.0001 | |

| B² | 89.17 | 1 | 89.17 | 24.08 | 0.0002 | |

| C² | 91.10 | 1 | 91.10 | 24.60 | 0.0002 | |

| D² | 12.19 | 1 | 12.19 | 3.29 | 0.0911 | |

| Residual | 51.85 | 14 | 3.70 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 51.66 | 10 | 5.17 | 108.83 | 0.62 | insignificant |

| Pure Error | 0.1899 | 4 | 0.0475 | |||

| Cor Total | 9482.41 | 28 |

| Variables | Goal | Optimum value Fe3O4–HTM |

|---|---|---|

| Dosage | in range | 2.6 |

| Concentration | in range | 100 |

| Temperature | in range | 60 |

| Time (min) | in range | 47.5 |

| Removal efficiency predicted () | maximum | 99.34 |

| Removal efficiency experimental () | maximum | 98.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).