1. Introduction

Environmental pollution has increased in the current global scenario due to different toxicants discharged from industrial sectors such as textile, agriculture, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. The textile industry is the largest generator of dying effluents because of the high-water consumption during various processing operations such as bleaching, dyeing, printing, and stiffening. However, 20% of the dye is lost during the dying process due to poor levels of dye fixation to fiber [

1]. Dyeing effluents have a serious environmental impact because disposal of these effluents into the receiving water body causes damage to aquatic biota or humans by mutagenic and carcinogenic effects [

2]. Color has different negative effects when present in water, it alters the transparency and gas solubility of water effluents, interferes with the growth of living substances, and obstructs photosynthesis. Out of all types of dyes azo dyes are preferably used for dyeing in the textile industries due to their ability to form colloidal dispersion and having low solubility in water [

3]. Azo dyes are further classified as direct, acidic, basic, vat, disperse, and reactive dyes, etc [

4,

5]. Azo dyes are the largest class of dyes, with the greatest variety of colors containing sulfonate groups as substituents, and are called sulfonated azo dyes. Azo groups in conjugation with aromatic substituents or ionizable groups make a complex structure that leads to a huge expression of variation of colors in dyes [

6,

7]. Most industries, including textiles, pharmaceuticals, paper and pulp, etc., have been found to use reactive dyes most frequently. Reactive dyes are non-biodegradable and require new technologies for their removal from polluted water.

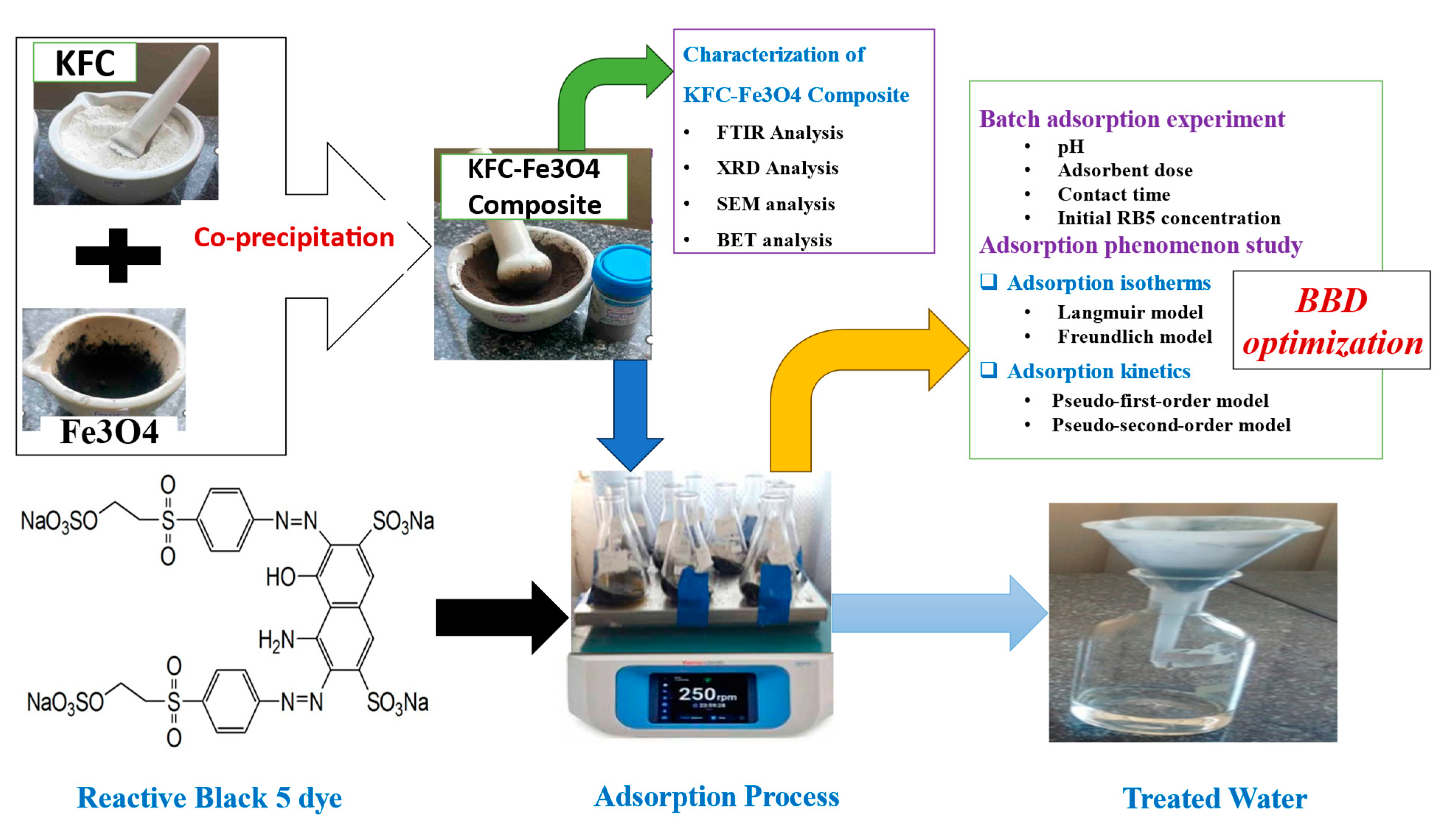

Reactive black 5 (CAS No. 17095-24-8) is a black powder categorized as an anionic azo dye due to the presence of an anionic functional group of =NaO

3S- with the molecular formula: C

26H

21N

5Na

4O

19S

6, molar mass: 991.82 g·mol

-1, density: 1.21 g/cm

3, solid, melting point >300

oC (573 K), and it is soluble in water, with a maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) of 597 nm. RB5 dye (

Figure 1) is a carcinogenic water-soluble azo dye that is widely used in textile industries, manufacturing printing paper, and research laboratories [

8]. RB5 is widely used in the textile industry for dyeing cotton, cellulosic fibers, wool, and nylon. It is also utilized in paper manufacturing and various research applications [

9]. Among the dyes, dyes have an “azo” functionalization category, as water-soluble dyes are the most problematic dyes [

10,

11]. Therefore, the treatment of wastewater containing dyestuff is very essential before discharge. Usually, a combination of different methods is needed to remove textile azo dyes. Adsorption is one of the crucial techniques in removing dyes from contaminated wastewater which is generally preferred to other ways, due to additional features such as fastness, simplicity, low cost, non-toxic, simple design, and high-efficiency performance [

1,

12]. The key factor in adsorption phenomena is to select an optimum adsorbent with the highest capacity as well as the fastest kinetics for pollution removal [

13,

14]. Different adsorbents are used to remove dyes, some of which include magnetic nanoparticles, natural adsorbents, activated carbon [

12], silica gel, sawdust, peat, ash, bentonite, and kaolin [

15]. Some study shows that adsorbents like activated carbon are efficient in removing a wide range of pollutants from water and wastewater however; it’s a costly adsorbent [

16]. As a result, there is a search for new, innovative, and cost-effective adsorbents for the purification of effluents containing dyes [

17,

18]. An adsorbent is considered cost-effective if it requires little processing, is abundant in nature, and is a by-product waste material resulting from an industry [

19].

Many researchers have studied clay minerals like kaolin [

15], red mud, natural and modified attapulgite clay [

20,

21], bentonite [

22] as a potential adsorbent for the removal of dyes from aqueous solution. Clay materials are those aluminosilicate minerals and their tetrahedral and octahedral layers are seen to incorporate different ions [

20]. They have typical characteristics of high specific surface area, high ion exchange capacity, chemical and mechanical stability, and layered structure, which make them good adsorbents. Additionally, the modified clay materials have more surface area and porosity which makes them effective [

23,

24,

25]. Kaolin [Al

2Si

2O

5(OH)

4] is a common phyllosilicate mineral belonging to a large general group known as the clays. The main constituent mineral in kaolin is kaolinite; kaolin may usually contain quartz, mica, and other less frequent minerals [

26]. Although kaolin is primarily used in the cement and construction industry, it can also be used as a raw material to produce alum (aluminum sulfate) [

18] and silica [

27].

For better adsorption, the clay should have a large surface area that activation i.e. chemical and physical activations can achieve. The chemical activation is conducted using an acid solution, while calcination (700°C) is applied for physical activation [

25]. The application of clay as an adsorbent has drawbacks i.e., it is difficult to separate the solid phase from the aqueous solution after the adsorption process. To solve this problem, combining clay with magnetic material could be chosen. The magnetic property that is produced by magnetic material was needed to facilitate the separation process between the clay and liquid phase using an external magnetic field after the adsorption process [

10,

28,

29]. As a type of magnetic material, iron oxide (Fe

3O

4) can be composed in clay [

26,

29]. It forms a ferromagnetic regularity with the highest magnetization saturation (Ms) value of 92 emu/g [

29]. Coprecipitation methods can conduct the synthesizing of magnetic composite material [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Magnetic nanoparticles have a couple of specific properties, such as the ease of synthesis of nanoparticles, large surface area, a superparamagnetic property that makes these particles respond to the external magnetic field and, in the absence of an external field, lose their magnetic properties; they don’t need the filtration process and centrifuge steps during the extraction process and the ability to extract large volumes of samples and removal of various organic and inorganic environmental pollutants [

7,

31]. Several investigations have been carried out to evaluate the magnetic composites' performance in water treatment by adsorption such as the adsorption of Cu(II) on magnetic starch-g-polyamide-doxime//Fe

3O

4 nanocomposites [

32], removal of crystal violet from aqueous solutions by adsorption on magnetic nanocomposite hydrogels and laponite RD [

34], removal of congo red dye by Fe

3O

4@MgAl-LDH composite [

28], removal of heavy metals by magnetic nano-Fe

3O

4-dioctyl phthalate [

21], etc.

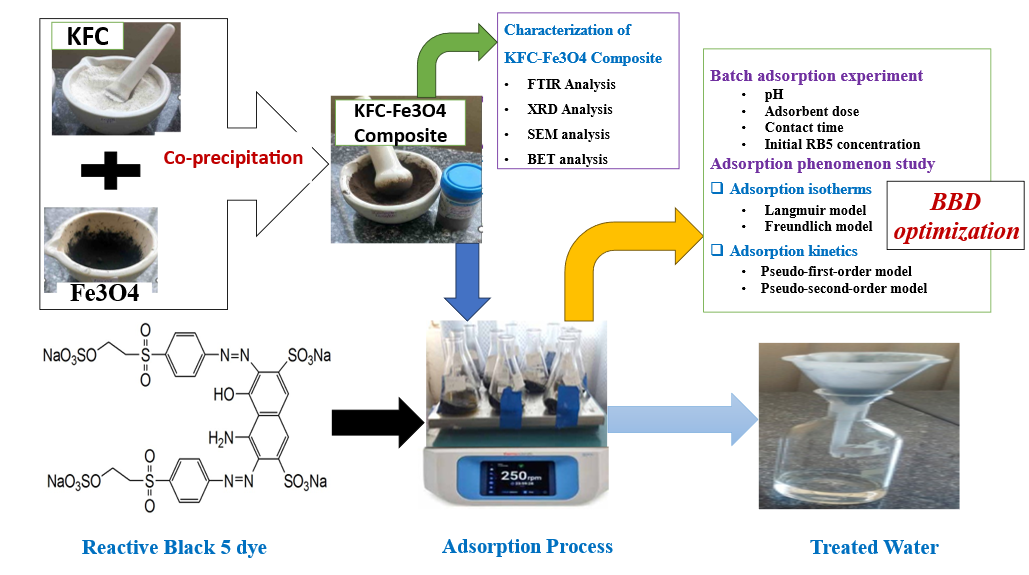

No research has been cited on applying KFC-Fe3O4 composite for RB5 dye removal from aqueous media. Thus, the current work aims to enhance the physicochemical characteristics of Kaolin filter cake (KFC) a residue of kaolin as an adsorbent, and to combine this with the extraordinary properties of nano iron oxide to produce a locally abundant and low-cost adsorbent with high adsorption capacity and readily separable for wastewater treatment. The KFC had similar chemical compositions compared to that of the kaolin. The only difference was the amount of the major components silica and alumina. To this end, activated KFC/Fe3O4 nanocomposite was synthesized by chemical co-precipitation method to test its feasibility as an adsorbent in the removal of RB5 dye from aqueous solutions. The adsorbent was characterized using Brunauer Emmett Teller ( BET ), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Batch experiments were used to evaluate the effect of adsorbent dose, pH, contact time, and initial concentration on the adsorption characteristics of nanocomposites was studied, and the experimental data obtained from the equilibrium studies were fitted to the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption models. In addition, the kinetics of the adsorption process was also studied. Factor parameters were optimized using Box-Behnken experimental design (BBD) in response surface methodology (RSM). Furthermore, the regeneration and reuse of adsorbent were evaluated. The research outcome would provide a low-cost magnetic-based nanocomposite to remove RB5 dye in an eco-friendly way and effectively. Hence, this work introduces adsorption for RB5 textile dye removal and provides a novel approach toward a reusable and easily separate magnetic adsorbent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Different mechanical size reduction equipment (jaw crusher, disk mill, sieves); and classical thermal equipment (Hot air oven and muffle furnace) were used for adsorbent preparation. Also, analytical equipment and glassware such as analytical balance, pH meter, centrifuge, hot plate with a magnetic stirrer, measuring cylinder, test tubes, and pipette were frequently used for batch adsorption experiments. Ferric chloride (FeCl3·6H2O, central lab, AASTU, Ethiopia), iron sulfate (FeSO4·7H2O central lab, AASTU, Ethiopia), and ammonia hydroxide solution (NH4OH) were used as starting materials. Reactive black 5(RB5) dye with MF: C26H21N5Na4O19S6, MW: 991.82 g· mol-1 was collected from KTSC (Kombolcha, Ethiopia) and used as received. Stock solutions (1 g L-1) of RB5 were prepared and the desired concentrations for adsorption experiments were obtained by diluting the stock solution with deionized water. The solution pH was attained by adding NaOH (0.01 mol/L) or HCl (0.01 mol/L). All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation and Activation of Kaolin Filter Cake (KFC)

Kaolin filter cake was collected from Awash Melkassa Chemical Factory, Ethiopia. KFC is the solid waste formed by the substances retained on a filter during the production process of Aluminum Sulphate from the raw material kaolin. The chemical factory has five main sections (suspension reaction and neutralization, filtration, evaporation, crystallization, and grinding). Among these sections, a solid waste filter cake was generated during the filtration unit operation. The solid of KFC waste was dried at 80 °C for 24 hours. After that, the KFC was crushed using a jaw crusher (BB50), and disk mill (Pulvisette 13), and sieved using standard sieves (ISO9001) with sizes of less than 0.075 mm. The adsorbents (raw powder and calcined) were prepared from the KFC. The Calcined adsorbent was prepared by treating filter cake kaolin at 700◦C for 2 hrs. in a muffle furnace (Nabertherm B180). Finally, the two adsorbents were packed in airtight plastic bags and stored in a safe environment.

2.3. Synthesis of KFC-Fe3O4 Nanocomposite

Co-precipitation is a simple and practical method of creating a magnetic composite from aqueous salt solutions by adding a base as a room-temperature precipitating agent. The primary benefit of the precipitation technique is the large-scale synthesis of nanoparticles. Using in situ chemical co-precipitation, a magnetic KFC-Fe3O4 nanocomposite was created using ferrous and ferric phosphate salts in an alkaline aqueous solution. The procedure involved dissolving 6.5 g of KFC, 8.4 g of FeCl3·6H2O, and 4.6 g of FeSO4·7H2O in 500 mL of distilled water, aggressively stirring with a mechanical stirrer on the hot plate, and heating the mixture to 80 ◦C for two hours. A 25 M NH4OH solution was added dropwise to the resultant mixture while agitated with a magnetic stirrer until the pH reached 10–11. After separating the black precipitate with a strong magnet and repeatedly rinsing it with deionized water, it was dried overnight at 80 °C in an oven. The nanocomposite was then dried for two hours at 80 °C after being cleaned with distilled water. After that, the dried magnetic nanocomposite was ground to a fine powder (0.075mm) using electrical grinder tools followed by calcination at 700 ◦C for 2 h under air atmosphere.

2.4. Characterization of Synthesized KFC-Fe3O4 NCs

Fourier-transform infrared (PerkinElmer 65 FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted to observe the functional groups, stretching vibrations, and absorption peaks present on the surface of nanocomposites. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM INSPECT F 50) analysis was performed to study the morphology of the KFC-Fe3O4 NCs. Furthermore, the crystalline property of the KFC-Fe3O4 NCs was characterized using X-ray powder diffraction ((XRD-X-ray tube cu40kv, 40 mA, Olympus BTXH). The specific surface area of the adsorbent was determined using the adsorption and desorption of the liquid nitrogen. The Bru-nauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method was applied for this specific surface area determination (Horiba Instrument Inc. SA-9600).

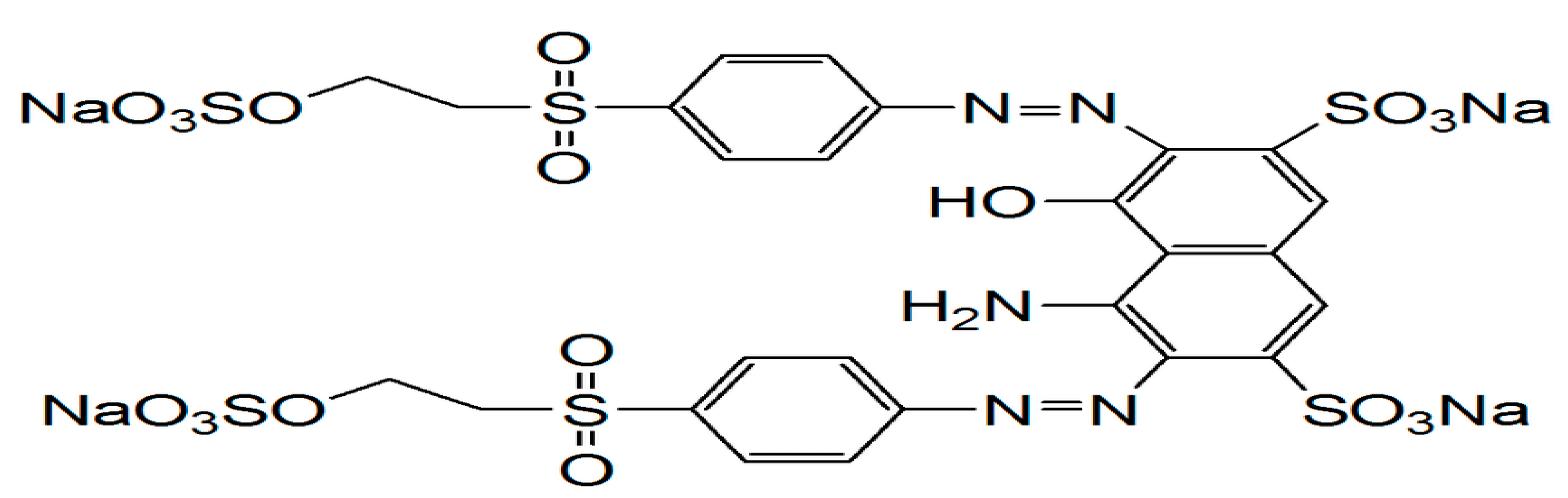

2.5. Point of Zero Charge (pHpzc)

The salt addition process measured the KFC-Fe3O4 NCs point of zero charge (pHpzc). To determine pHpzc, the pH was adjusted from 1–12 by adding 0.1 N NaOH and HCl. Then, 0.5 g of adsorbent was added to each solution and kept for 24 h with intermittent shaking. The final pH (pHf) of the solution was noted and the difference between the final and initial pH (change in pH) (

Y-axis) was plotted versus the initial pH (

X-axis). The intersection point of the curve yield was pHpzc [

28].

2.6. Batch Adsorption Experiment

All adsorption experiments were carried out in 1,000 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing both RB5 and KFC-Fe

3O

4 composite. The mixtures were continuously stirred (150 rpm) at room temperature in different time intervals (20–120 min). Then adsorbent was separated from the mixture solution by permanent magnet. The concentration of the RB5 in each sample was measured using a spectrophotometer ( UV-spectrophotometer (DR 5000) at 597 nm by a calibration curve [

35]. In order to study effects of various parameters, experiments were conducted at different amounts of pH (3 to 9), adsorbent (1.5 to 3.5 g), contact time (40 to 80 min.), and initial dye concentrations (30 to 100 mg/L). The removal efficiency and removed amount of dye by KFC-Fe

3O

4 composite were calculated by Equation (1) and (2), respectively.

where,

Co and

Ce were initial and equilibrium concentrations of RB5 dye in the solution (mg/L),

m was the adsorbent mass (g) used, and

V was the volume of the solution (L).

2.7. Experimental Design

For the optimization process, a Box-Behnken design (BBD) was used to determine the optimal operational conditions for RB5 dye removal by CKFC-Fe3O4 nanocomposite within 4 input parameters (pH, adsorbent dose, contact time, and initial dye concentration). The software Design Expert (13.0, StatEase, USA) was used to construct the adsorption study and statistically interpret the results [

36].

Table 1 illustrates 3 ranges (i.e.,-1, 0, and +1) of explored factors. The preliminary tests were used to determine the coded values of the parameters and the parameters to be employed in the adsorption optimization. The quadratic model employed for fitting the components (independent factors and RB5 removal) of the model is illustrated in Eq. (3).

where y is the response variable, bo is the intercept constant, 4 is the number of variables, ε the residual expressed as the difference between the calculated and experimental results, x

i and x

j are variables, b

ii the coefficient of quadratic parameters, and b

ij is the coefficient of the interacting parameters.

2.8. Adsorption Isotherm and Kinetic Models

Isotherm models show the equilibrium amount of adsorbate available in the solution and the amount of adsorbate available on the surface of the adsorbent. Langmuir and Freundlich are the most commonly used adsorption isotherms. Langmuir adsorption isotherm assumes that the adsorption occurs at specific homogenous sites and is the most suitable for monolayer adsorption [

37], while the Freundlich adsorption isotherm model assumes that the formation of multilayer and heterogeneous systems due to the non-uniform distribution of adsorption affinities and is not confined within the formation of monolayers [

11]. Equation (4) represents the linear form of Langmuir’s to determine the adsorption parameters.

where q

max represents the maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g) and KL (L/mg) is Langmuir’s isotherm constant, showing the binding affinity between dye and KFC.

Equation (5) represents the linear form of Freundlich’s isotherm

where, Kf is Freundlich’s constant and is used to measure the adsorption capacity, and 1/n is the adsorption intensity. The value of 1/n demonstrates the adsorption process is either favorable (0.1 < 1/n < 0.5) or unfavorable (1/n > 2).

The rate at which the adsorbate (RB5 dye) was adsorbed on the surface of the adsorbent (CKFC) was studied using kinetics models, namely pseudo-first-order and second-order kinetic models. These kinetics models show the adsorbent's efficacy, indicating how fast or slow it adsorbs the adsorbate.

The pseudo 1st order is represented in Eq. (10):

where qt represents the adsorption capacity (mg/g) at time t while K1 (min-1) is the equilibrium rate constant.

Pseudo 2

nd order is represented in Eq. (11):

where K2 (g mg

-1min

-1) is the equilibrium rate constant. The values of linear coefficient regression (R

2) were used to predict the most suited isotherm and kinetic model for the adsorption process [

35].

Figure 1.

The structural formula of the Reactive Black 5 dye (RB5).

Figure 1.

The structural formula of the Reactive Black 5 dye (RB5).

Figure 2.

Point of Zero charges for KFC-Fe3O4 nanocomposite.

Figure 2.

Point of Zero charges for KFC-Fe3O4 nanocomposite.

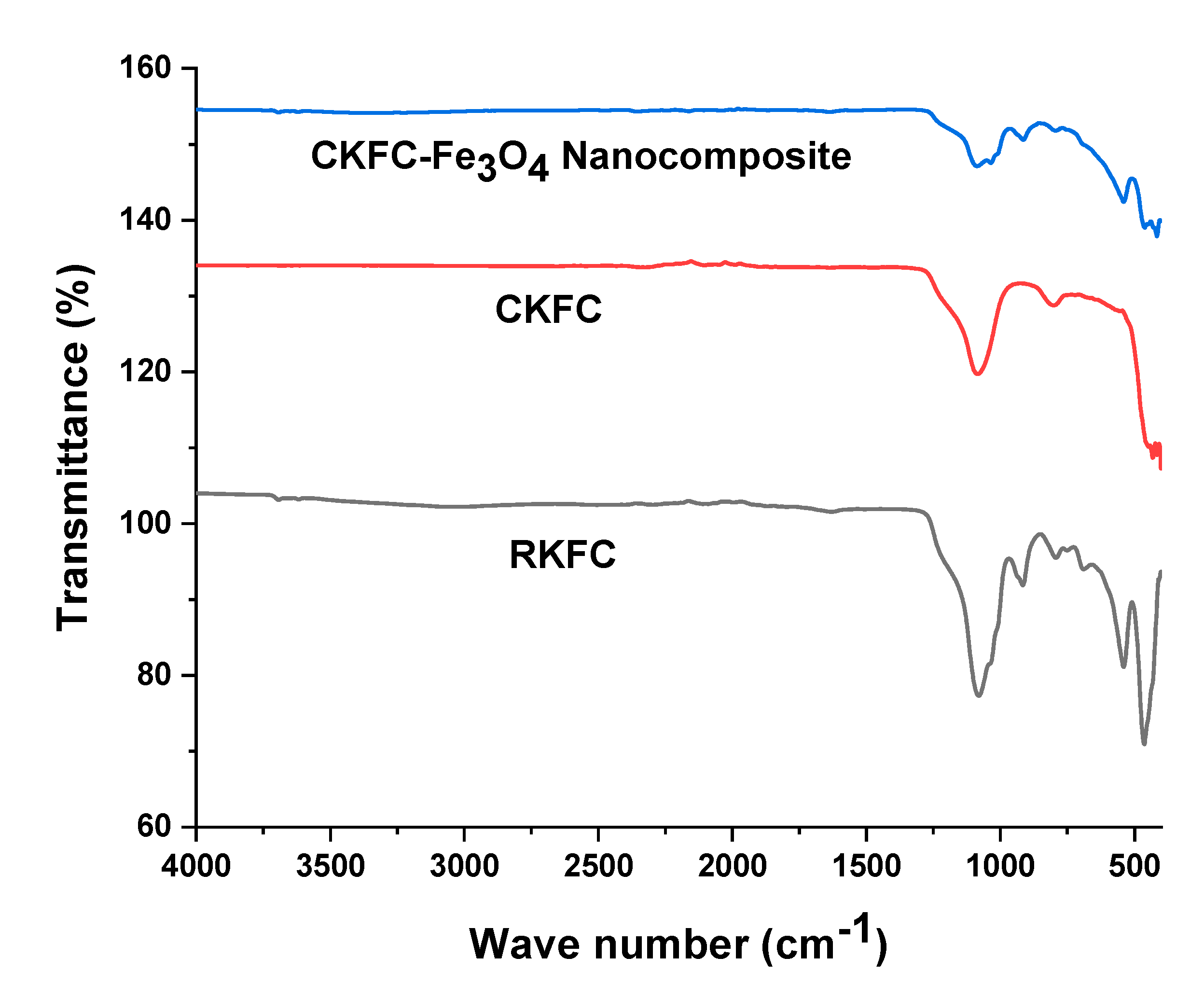

Figure 3.

FTIR analysis for KFC-Fe3O4 composite before and after adsorption.

Figure 3.

FTIR analysis for KFC-Fe3O4 composite before and after adsorption.

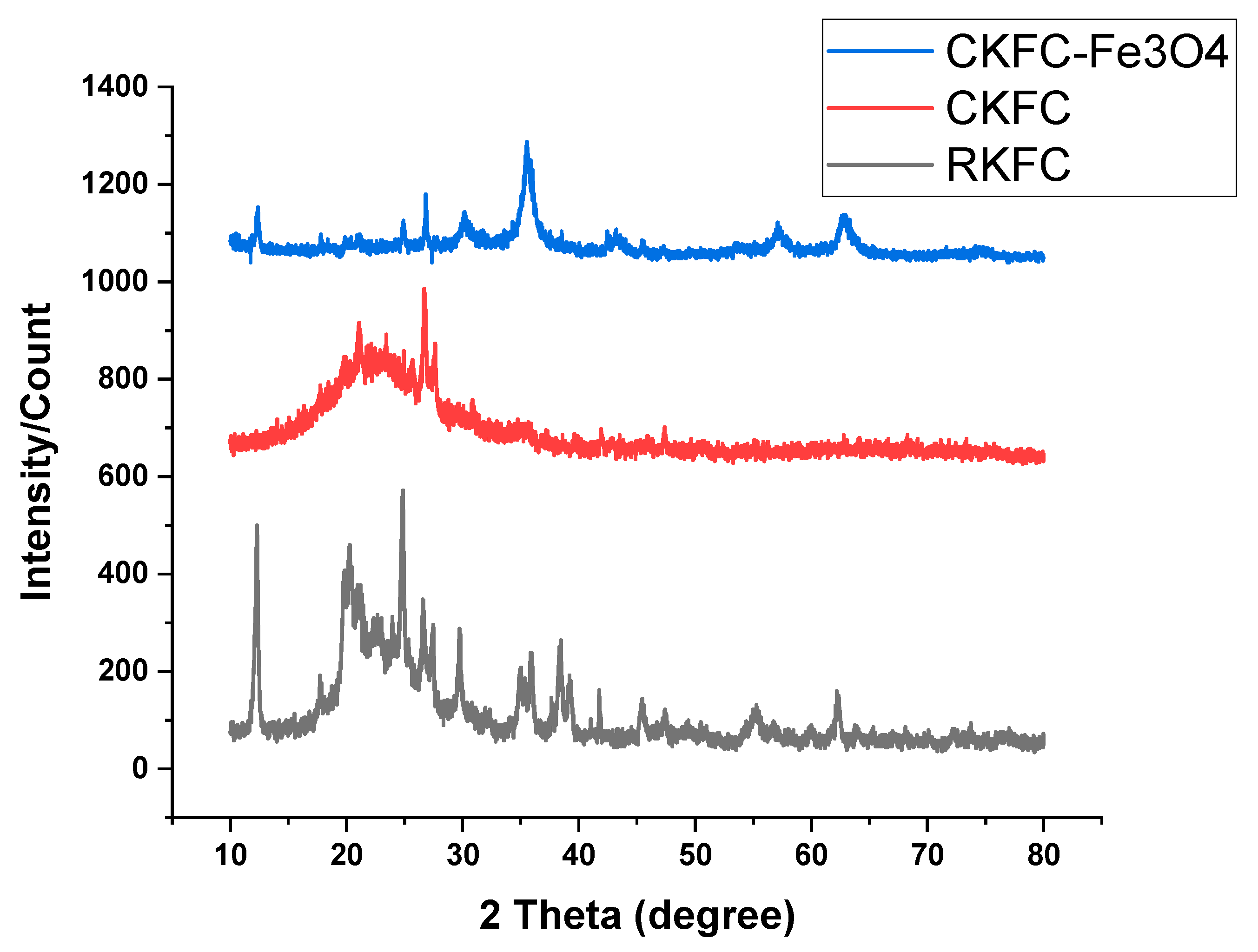

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction analysis for Raw, Calcined, and CKFC-Fe3O4 adsorbents.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction analysis for Raw, Calcined, and CKFC-Fe3O4 adsorbents.

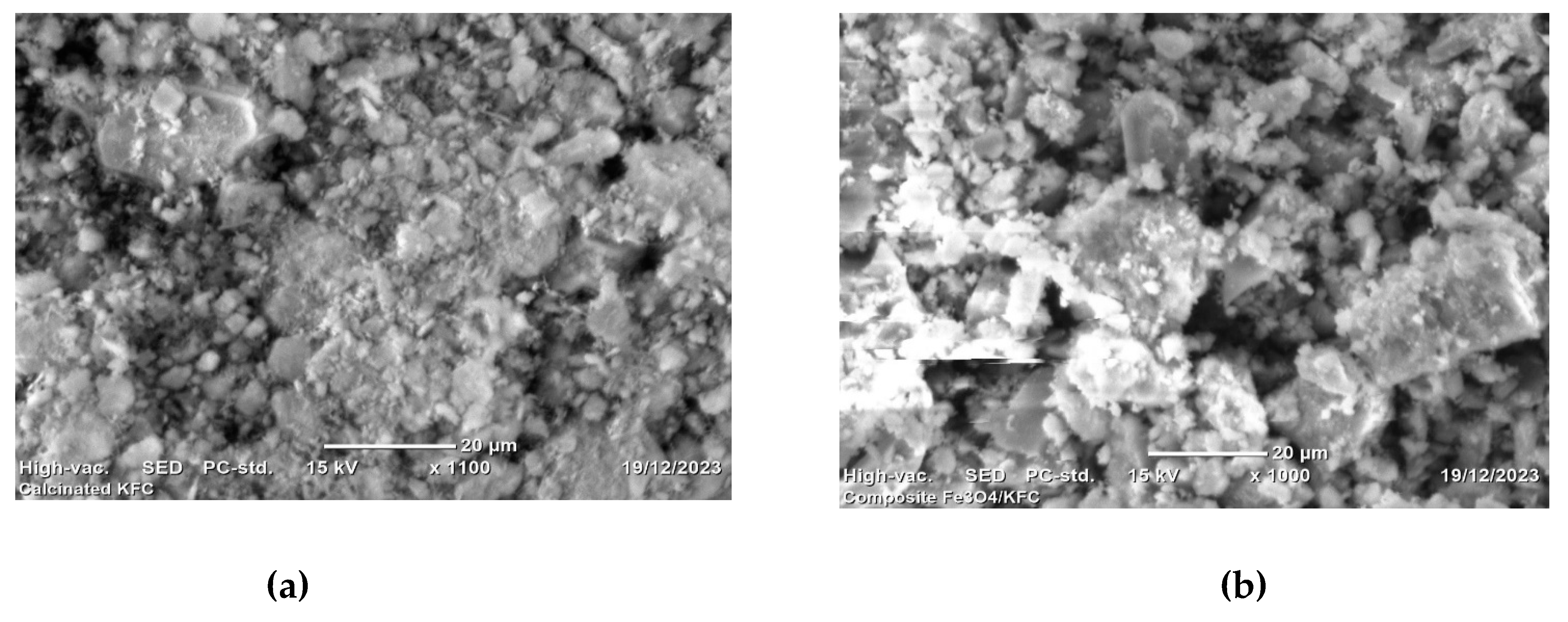

Figure 5.

SEM analysis of CKFC (a) and KFC-Fe3O4 composite (b).

Figure 5.

SEM analysis of CKFC (a) and KFC-Fe3O4 composite (b).

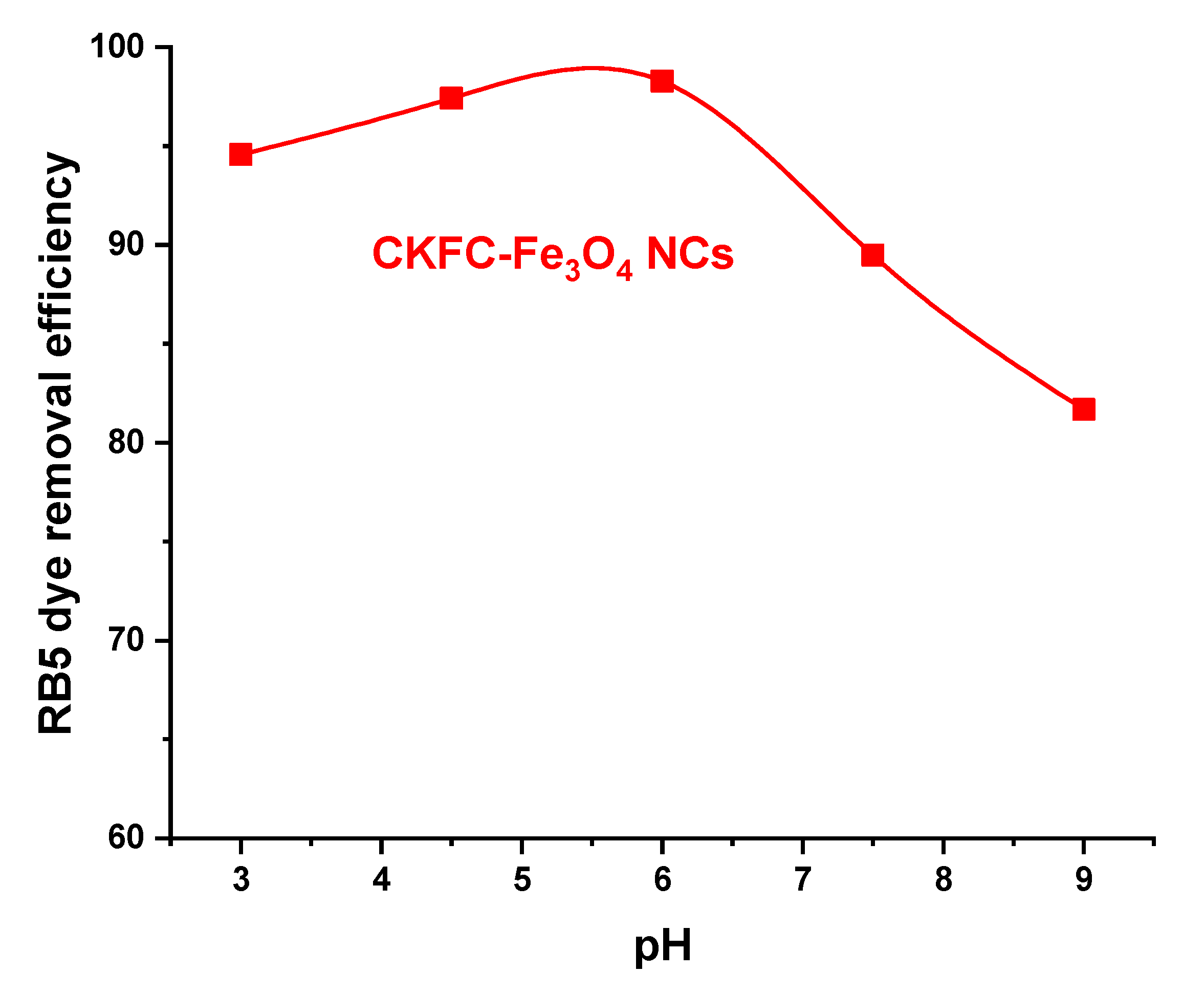

Figure 6.

Effect of pH on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

Figure 6.

Effect of pH on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

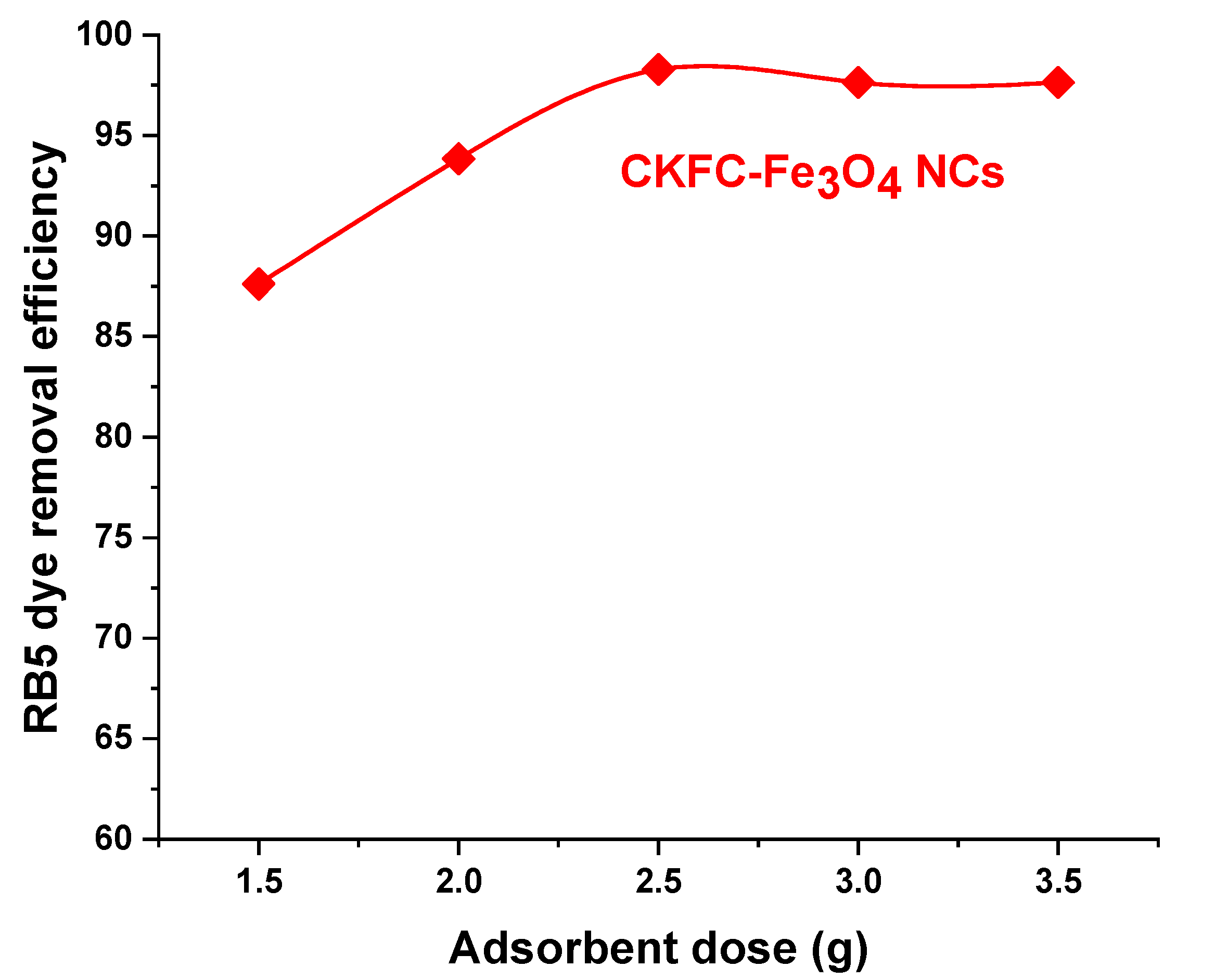

Figure 7.

Effect of adsorbent dose on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

Figure 7.

Effect of adsorbent dose on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

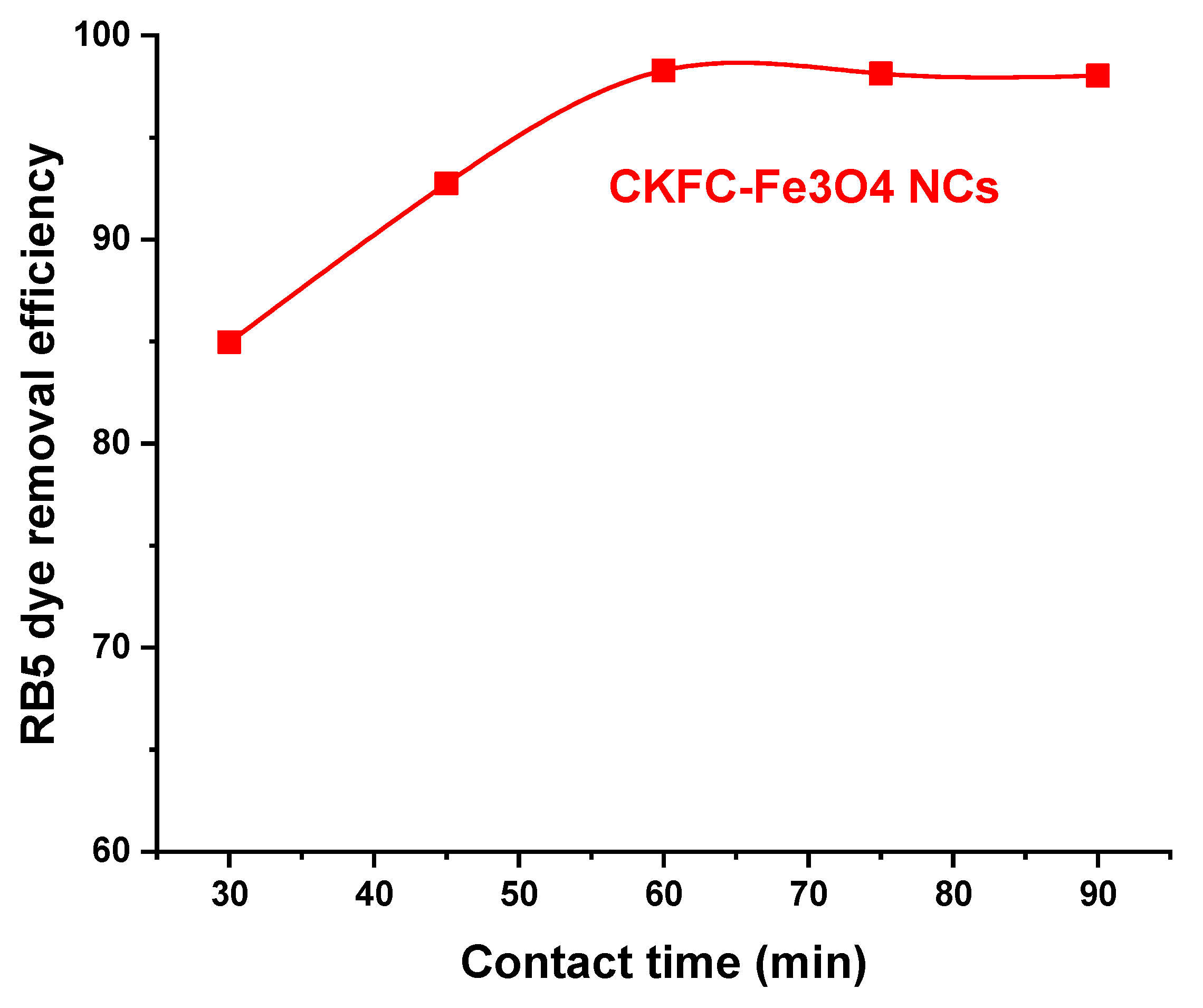

Figure 8.

Effect of contact time on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

Figure 8.

Effect of contact time on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

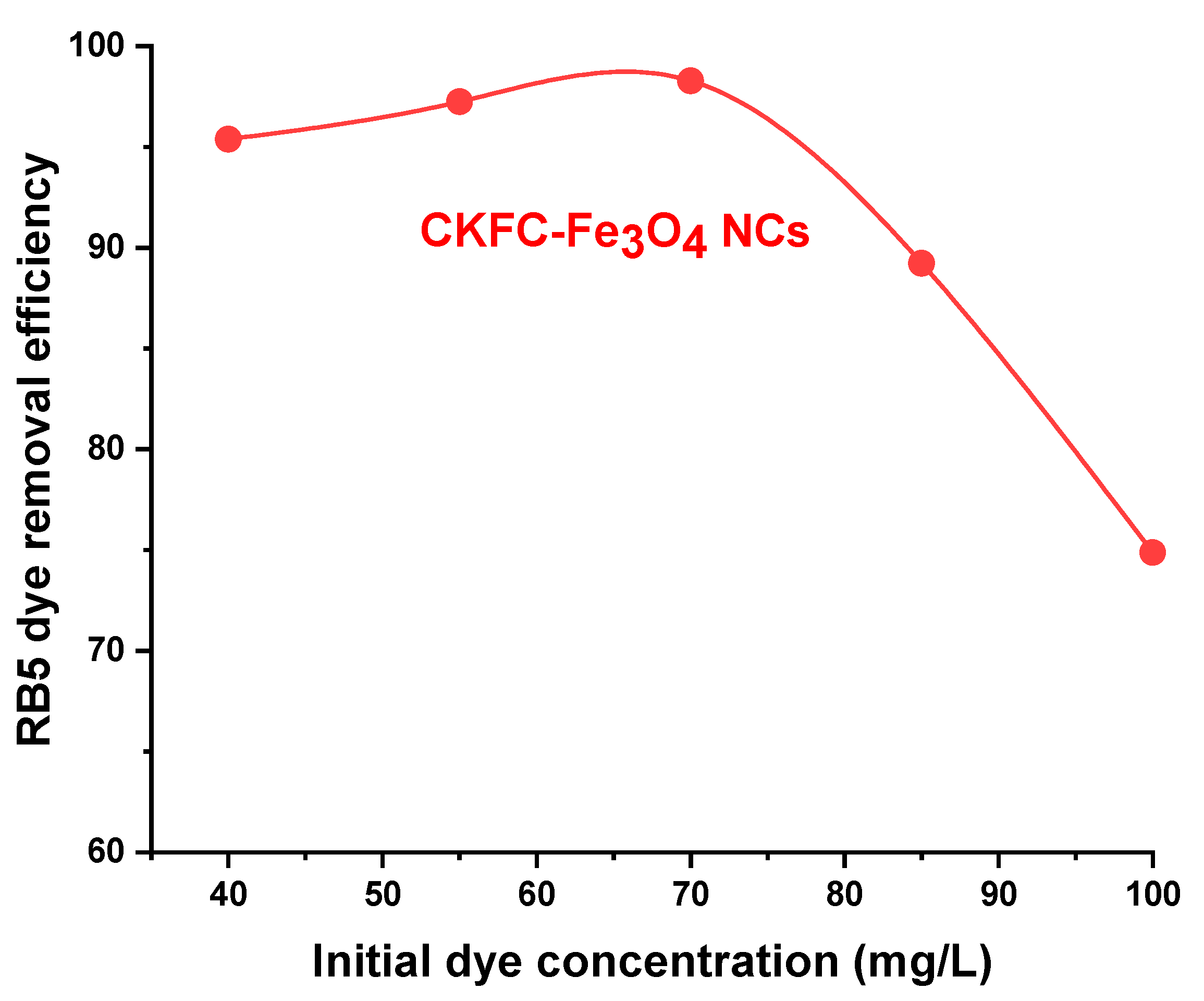

Figure 9.

Effect of initial dye concentration on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

Figure 9.

Effect of initial dye concentration on the percentage of RB5 dye removal.

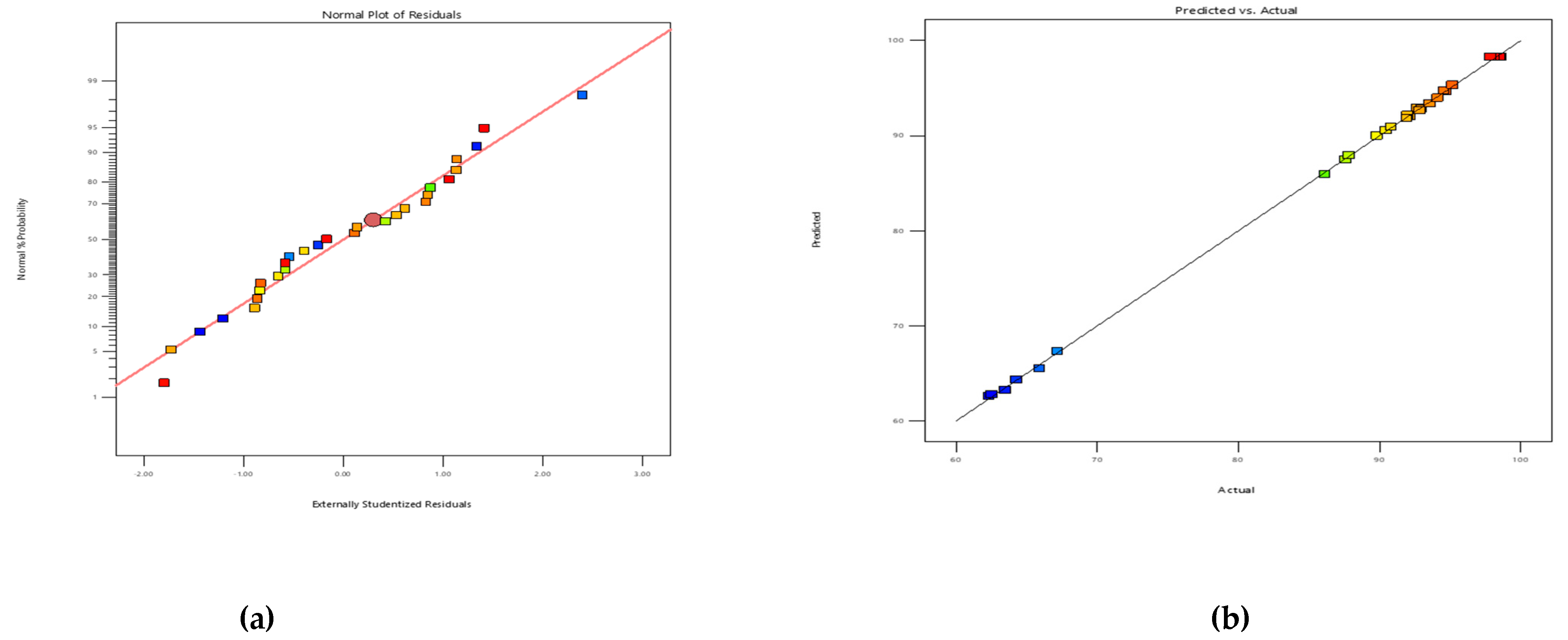

Figure 10.

(a) Normal probability plot, (b) Prediction vs. actual probability of RB5 removal percentage.

Figure 10.

(a) Normal probability plot, (b) Prediction vs. actual probability of RB5 removal percentage.

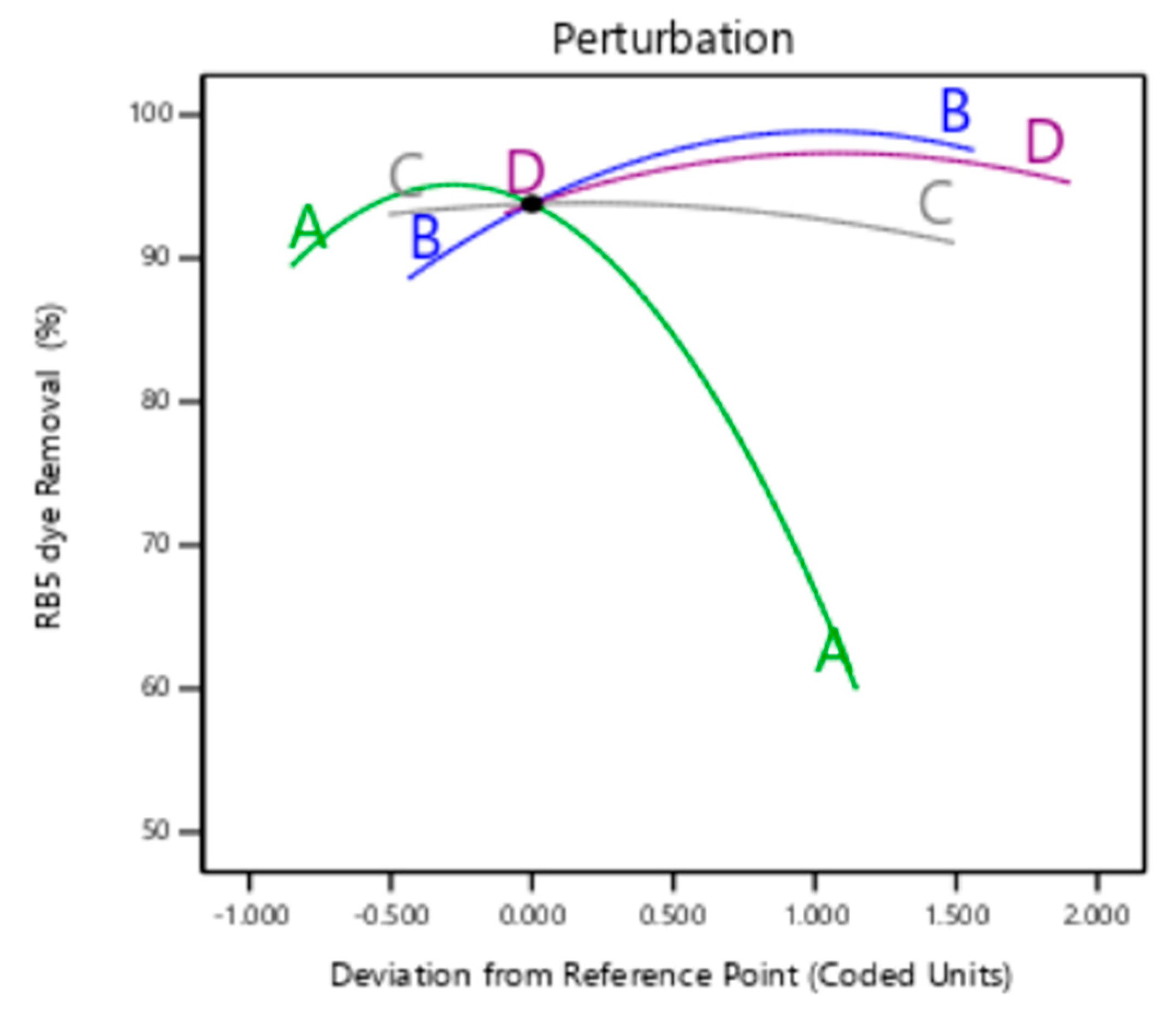

Figure 11.

Perturbation plot.

Figure 11.

Perturbation plot.

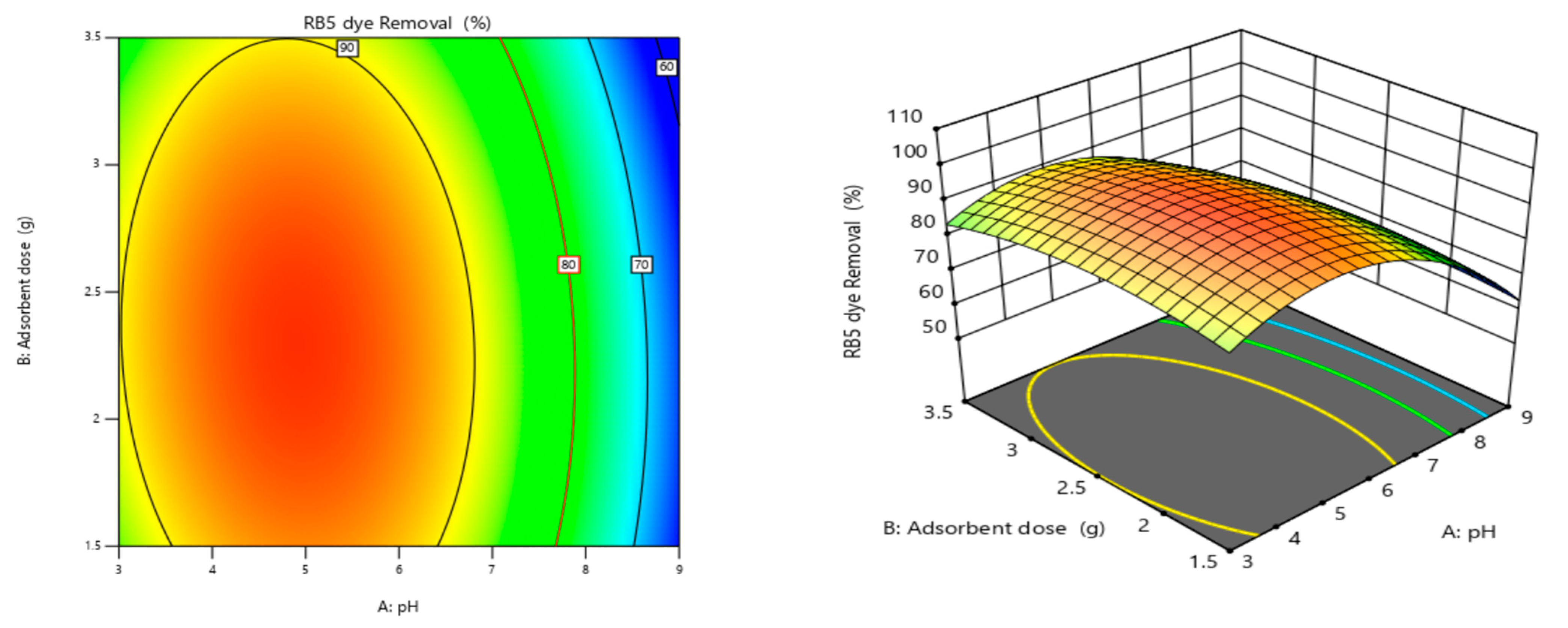

Figure 12.

Interaction effects of pH and adsorbent dose.

Figure 12.

Interaction effects of pH and adsorbent dose.

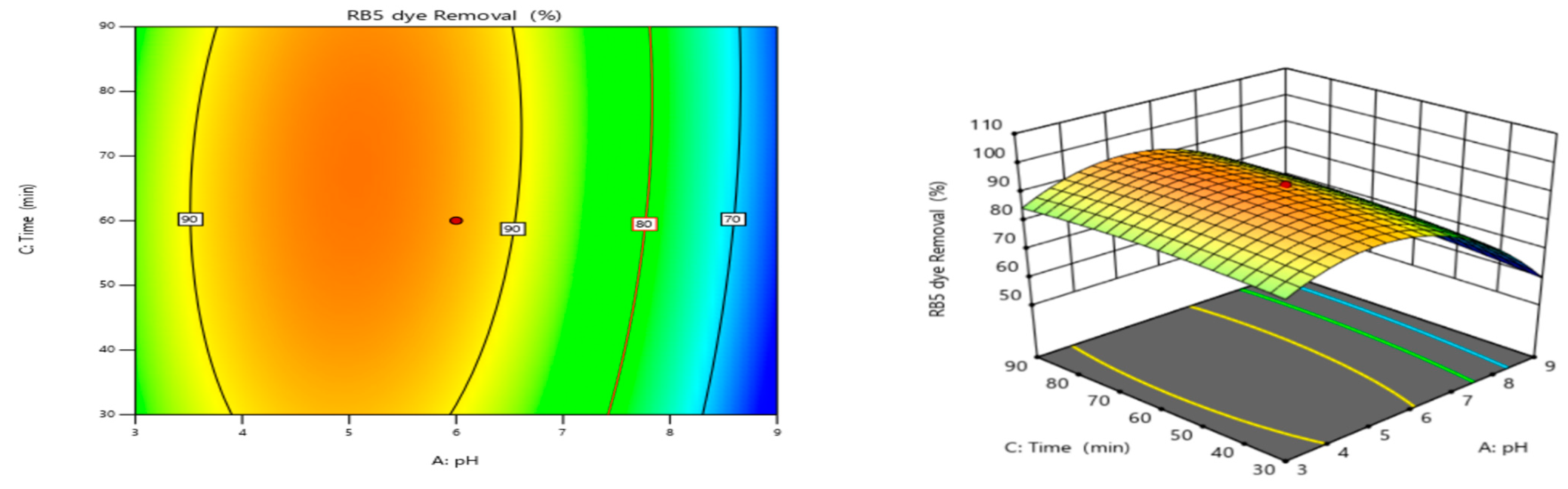

Figure 13.

Interaction effects of pH and contact time.

Figure 13.

Interaction effects of pH and contact time.

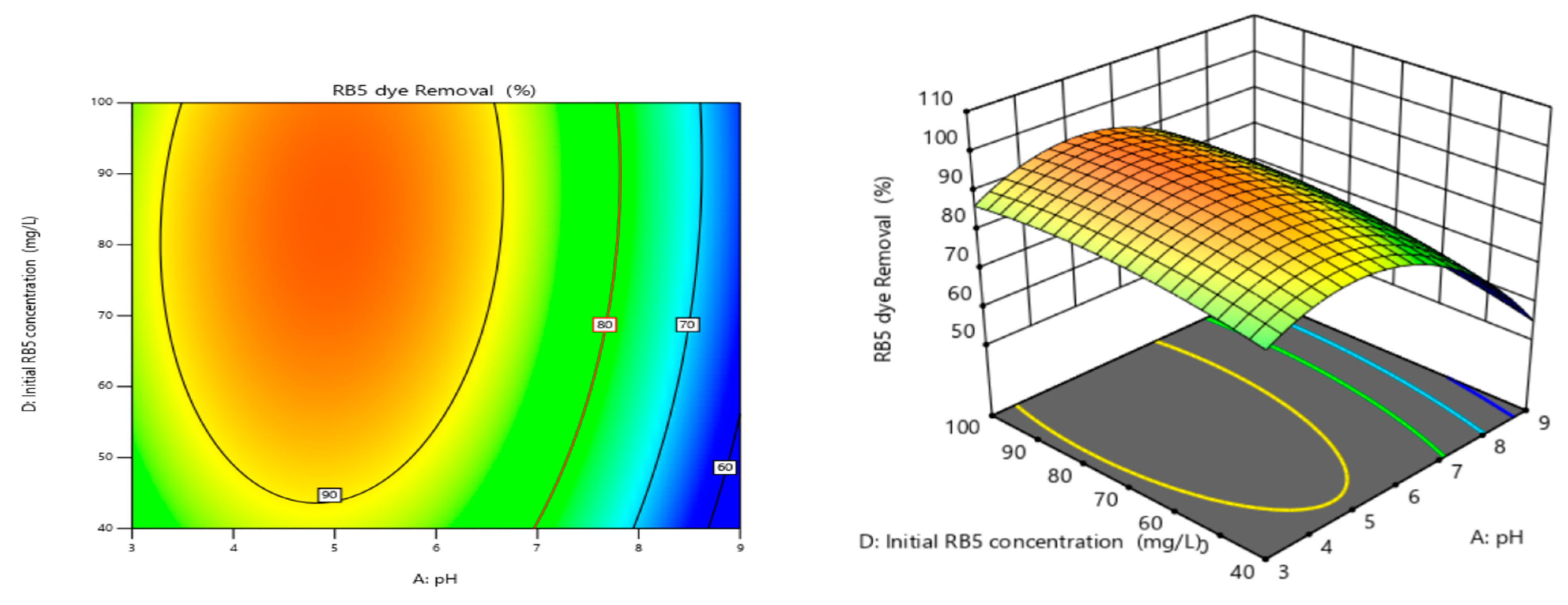

Figure 14.

Interaction effects of pH and initial RB5 concentration.

Figure 14.

Interaction effects of pH and initial RB5 concentration.

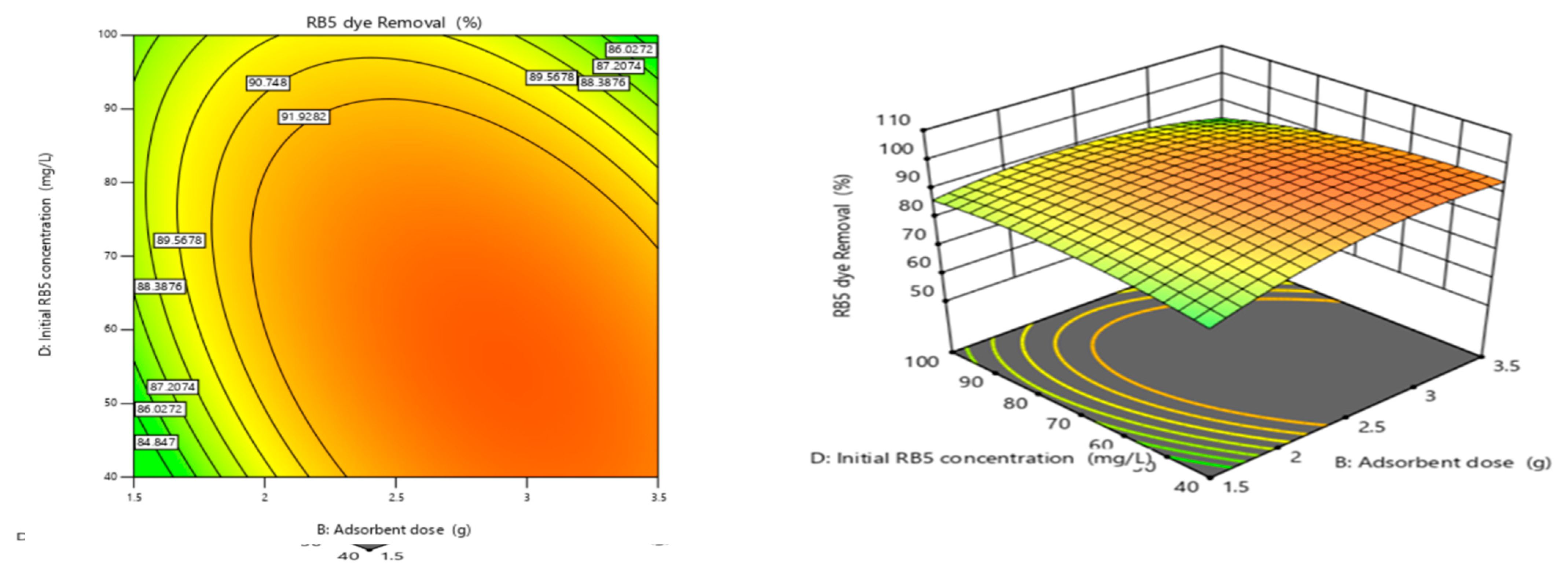

Figure 15.

Interaction effect of adsorbent dose and initial RB5 concentration.

Figure 15.

Interaction effect of adsorbent dose and initial RB5 concentration.

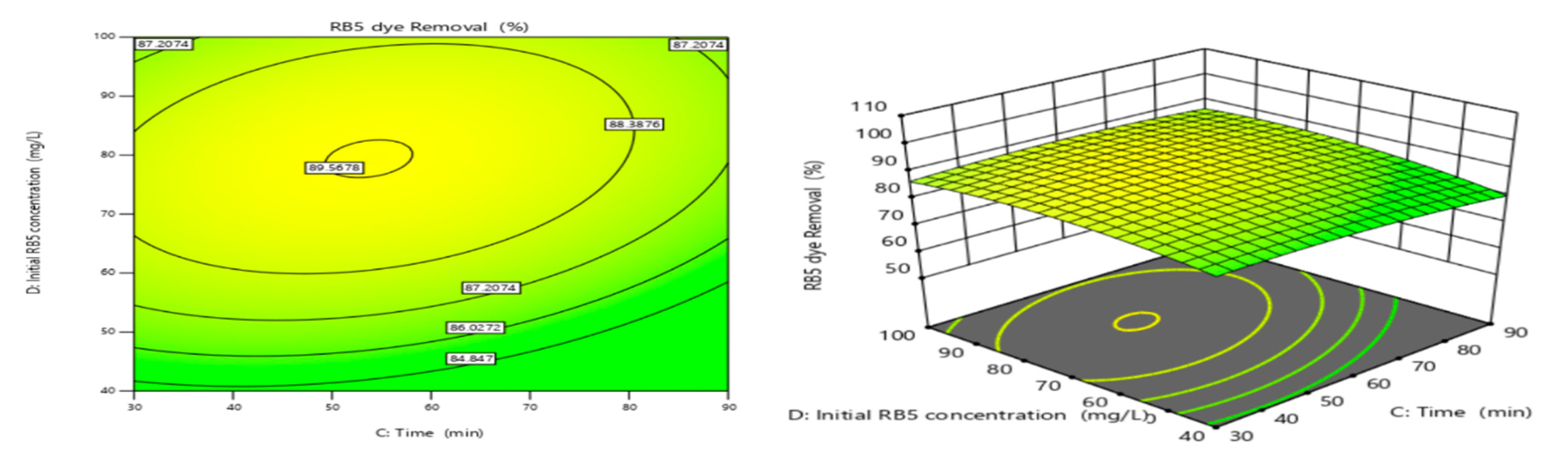

Figure 16.

Interaction effect of contact time and initial RB5 concentration.

Figure 16.

Interaction effect of contact time and initial RB5 concentration.

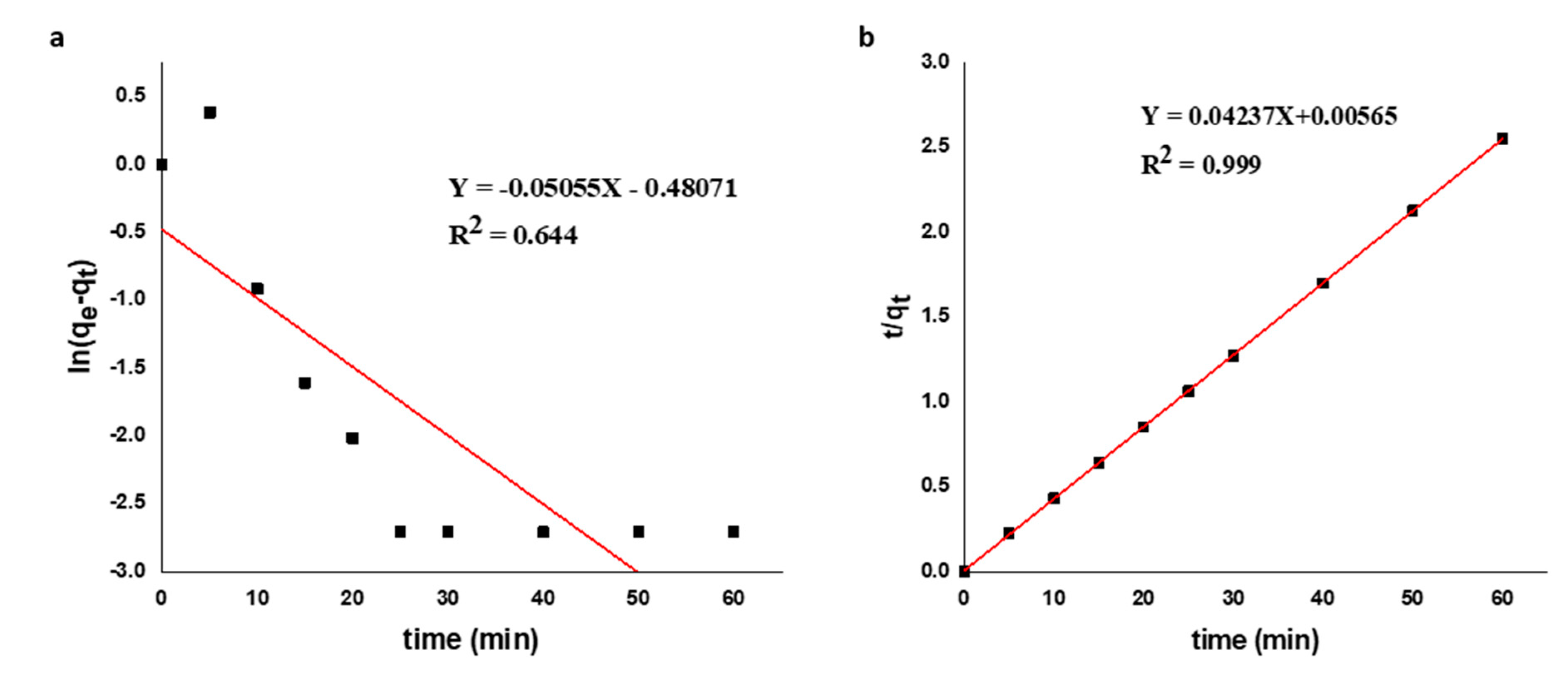

Figure 17.

The fitting of PFO (a) and PSO (b) kinetic models.

Figure 17.

The fitting of PFO (a) and PSO (b) kinetic models.

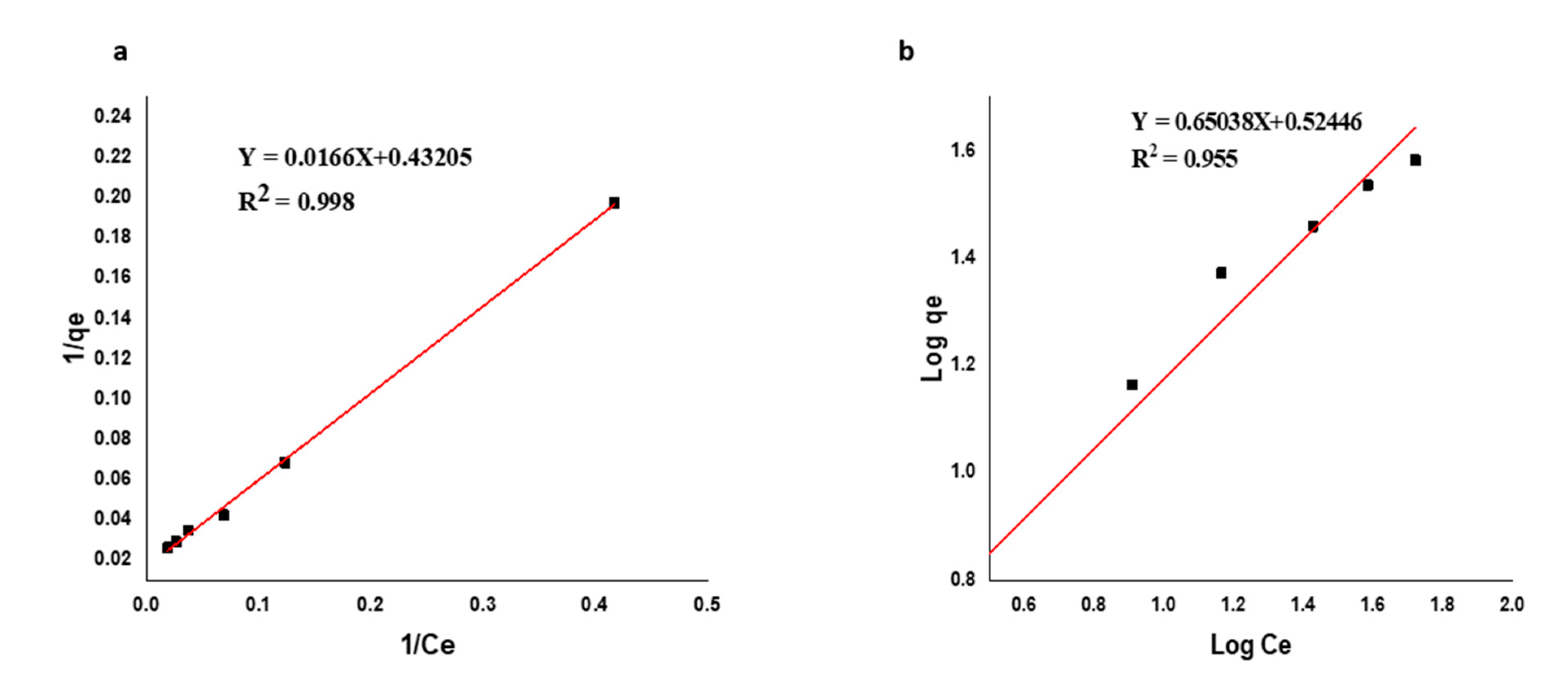

Figure 18.

Langmuir (a) and Freundlich’s (b) isotherms.

Figure 18.

Langmuir (a) and Freundlich’s (b) isotherms.

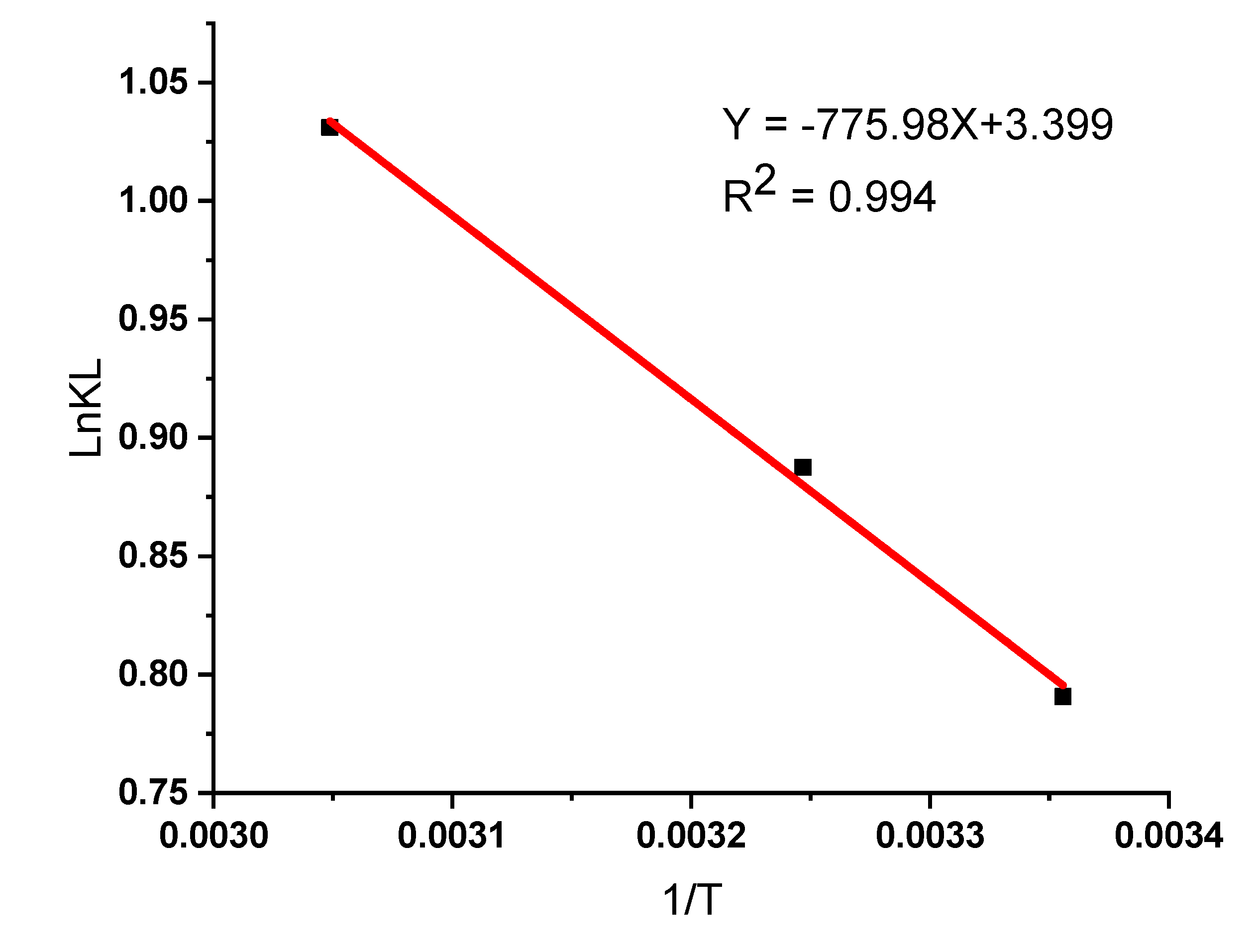

Figure 19.

Estimation of thermodynamic parameters for the Reactive Black 5 dye adsorption on the KFC-Fe3O4 composite.

Figure 19.

Estimation of thermodynamic parameters for the Reactive Black 5 dye adsorption on the KFC-Fe3O4 composite.

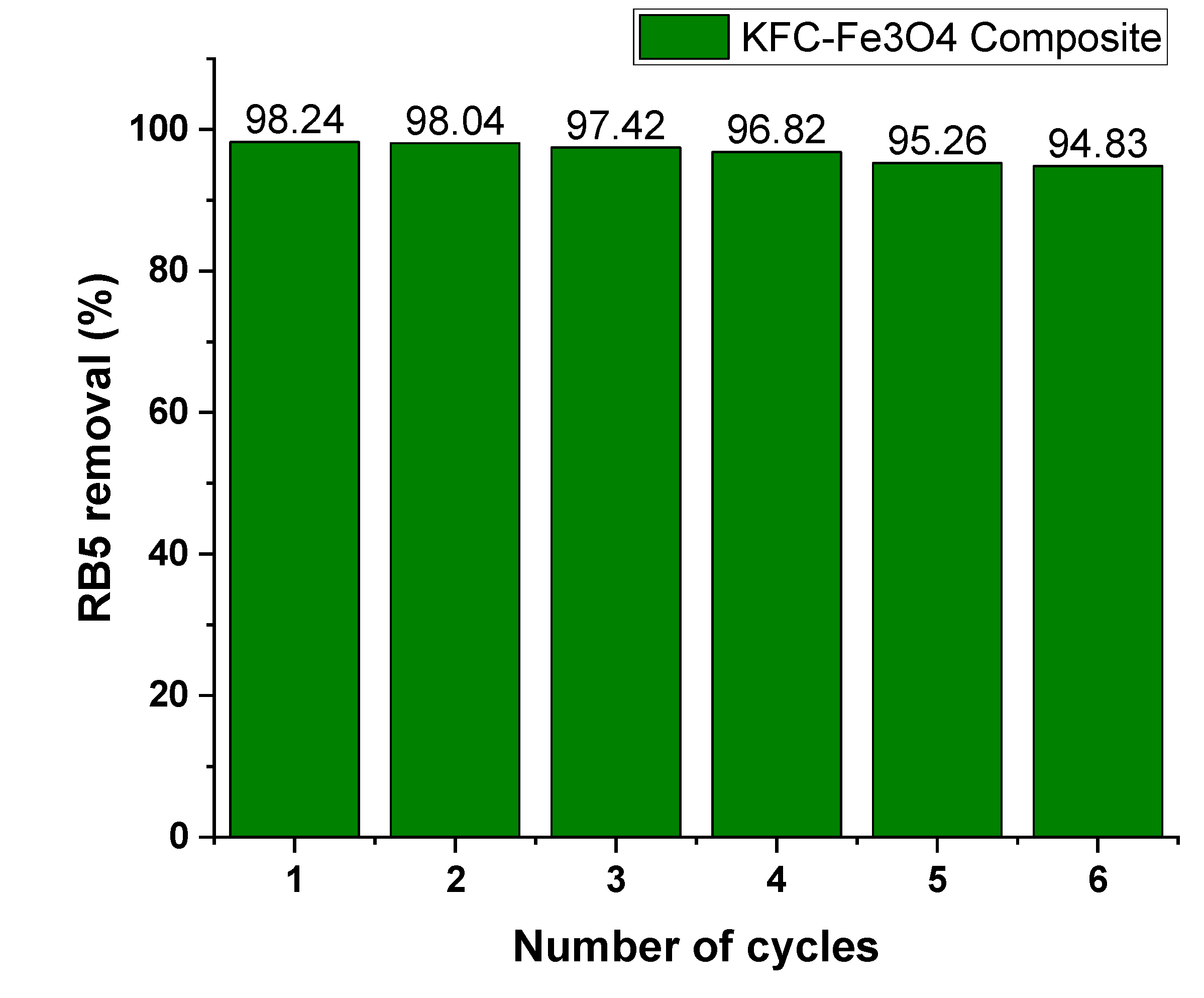

Figure 20.

RB5 removal (%) with KFC-Fe3O4 Adsorbent as a function of regeneration cycles.

Figure 20.

RB5 removal (%) with KFC-Fe3O4 Adsorbent as a function of regeneration cycles.

Table 1.

Codes and actual variables and their levels in BBD.

Table 1.

Codes and actual variables and their levels in BBD.

| Codes |

Variables |

Low (- 1) |

Center (0) |

High (+1) |

| A |

pH |

3 |

6 |

9 |

| B |

Adsorbent dose (g) |

1.5 |

2.5 |

3.5 |

| C |

Contact time (min) |

40 |

60 |

80 |

| D |

Initial dye concentration (mg/L) |

30 |

70 |

100 |

Table 2.

Experimental matrix based on BBD approach for designing experiments and corresponding quadratic model response .

Table 2.

Experimental matrix based on BBD approach for designing experiments and corresponding quadratic model response .

| Run |

A: pH |

B: Adsorbent dose (g) |

C: Time (min) |

D: Initial RB5 concentration (mg/l) |

RB5 Removal (%) |

Predicted RB5 Removal (%) |

| 1 |

6 |

3.5 |

30 |

70 |

92.97 |

92.81 |

| 2 |

3 |

3.5 |

60 |

70 |

92.13 |

92.01 |

| 3 |

6 |

1.5 |

60 |

40 |

86.12 |

85.95 |

| 4 |

9 |

2.5 |

30 |

70 |

64.26 |

64.31 |

| 5 |

6 |

2.5 |

60 |

70 |

98.56 |

98.28 |

| 6 |

6 |

3.5 |

90 |

70 |

93.56 |

93.35 |

| 7 |

6 |

2.5 |

90 |

100 |

94.58 |

94.74 |

| 8 |

6 |

1.5 |

90 |

70 |

90.82 |

90.90 |

| 9 |

3 |

1.5 |

60 |

70 |

87.58 |

87.50 |

| 10 |

9 |

2.5 |

60 |

100 |

65.89 |

65.50 |

| 11 |

6 |

1.5 |

30 |

70 |

90.45 |

90.58 |

| 12 |

6 |

2.5 |

60 |

70 |

98.13 |

98.28 |

| 13 |

3 |

2.5 |

60 |

40 |

92.64 |

92.94 |

| 14 |

9 |

1.5 |

60 |

70 |

62.31 |

62.57 |

| 15 |

3 |

2.5 |

30 |

70 |

94.12 |

93.96 |

| 16 |

6 |

2.5 |

30 |

40 |

94.68 |

94.66 |

| 17 |

6 |

1.5 |

60 |

100 |

92.85 |

92.64 |

| 18 |

9 |

2.5 |

90 |

70 |

67.19 |

67.29 |

| 19 |

6 |

3.5 |

60 |

40 |

95.17 |

95.33 |

| 20 |

3 |

2.5 |

60 |

100 |

89.82 |

89.98 |

| 21 |

9 |

2.5 |

60 |

40 |

63.47 |

63.23 |

| 22 |

6 |

2.5 |

60 |

70 |

98.24 |

98.28 |

| 23 |

3 |

2.5 |

90 |

70 |

91.94 |

91.84 |

| 24 |

6 |

2.5 |

30 |

100 |

91.97 |

92.14 |

| 25 |

6 |

2.5 |

90 |

40 |

92.94 |

92.91 |

| 26 |

6 |

2.5 |

60 |

70 |

97.85 |

98.28 |

| 27 |

9 |

3.5 |

60 |

70 |

62.52 |

62.74 |

| 28 |

6 |

3.5 |

60 |

100 |

87.84 |

87.95 |

| 29 |

6 |

2.5 |

60 |

70 |

98.64 |

98.28 |

Table 3.

ANOVA for Quadratic model.

Table 3.

ANOVA for Quadratic model.

| Source |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F-value |

p-value |

|

| Model |

4277.79 |

14 |

305.56 |

3593.69 |

< 0.0001 |

significant |

| A-pH |

2202.96 |

1 |

2202.96 |

25909.29 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| B-Adsorbent dose |

16.47 |

1 |

16.47 |

193.75 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| C-Time |

0.5547 |

1 |

0.5547 |

6.52 |

0.0229 |

|

| D-Initial RB5 concentration |

0.3571 |

1 |

0.3571 |

4.20 |

0.0597 |

|

| AB |

4.71 |

1 |

4.71 |

55.38 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| AC |

6.53 |

1 |

6.53 |

76.78 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| AD |

6.86 |

1 |

6.86 |

80.73 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| BC |

0.0121 |

1 |

0.0121 |

0.1423 |

0.7117 |

|

| BD |

49.42 |

1 |

49.42 |

581.25 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| CD |

4.73 |

1 |

4.73 |

55.64 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| A² |

1945.25 |

1 |

1945.25 |

22878.36 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| B² |

147.04 |

1 |

147.04 |

1729.36 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| C² |

16.94 |

1 |

16.94 |

199.26 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| D² |

60.54 |

1 |

60.54 |

711.96 |

< 0.0001 |

|

| Residual |

1.19 |

14 |

0.0850 |

|

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

0.7734 |

10 |

0.0773 |

0.7421 |

0.6814 |

not significant |

| Pure Error |

0.4169 |

4 |

0.1042 |

|

|

|

| Cor Total |

4278.98 |

28 |

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Results of sequential model sums of squares and model summary statistics RB5 removal efficiency.

Table 4.

Results of sequential model sums of squares and model summary statistics RB5 removal efficiency.

|

Source

|

Sum of Squares

|

df

|

Mean Square

|

F-value

|

p-value

|

|

|

Mean vs Total

|

2.206E+05 |

1 |

2.206E+05 |

|

|

|

|

Linear vs Mean

|

2220.34 |

4 |

555.09 |

6.47 |

0.0011 |

|

|

2FI vs Linear

|

72.26 |

6 |

12.04 |

0.1091 |

0.9942 |

|

|

Quadratic vs 2FI

|

1985.18 |

4 |

496.29 |

5836.99 |

< 0.0001 |

Suggested |

|

Cubic vs Quadratic

|

0.7129 |

8 |

0.0891 |

1.12 |

0.4580 |

Aliased |

|

Residual

|

0.4775 |

6 |

0.0796 |

|

|

|

|

Total

|

2.249E+05 |

29 |

7754.04 |

|

|

|

|

Model summary statistics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Source |

Std. Dev. |

R² |

Adjusted R² |

Predicted R² |

PRESS |

|

| Linear |

9.26 |

0.5189 |

0.4387 |

0.3169 |

2922.87 |

|

| 2FI |

10.50 |

0.5358 |

0.2779 |

-0.2191 |

5216.64 |

|

| Quadratic |

0.2916 |

0.9997 |

0.9994 |

0.9988 |

5.11 |

Suggested |

| Cubic |

0.2821 |

0.9999 |

0.9995 |

0.9978 |

9.37 |

Aliased |

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters for the RB5 adsorption.

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters for the RB5 adsorption.

| Order of reaction |

Parameters |

CKFC-Fe3O4 Composite |

RKFC |

| |

qe, exp (mg/gm) |

23.53 |

9.20 |

| Pseudo-first-order |

qe, cal (mg/g) |

0.51 |

0.85 |

| k1 (min-1) |

-7.60×10-4 |

-9.75×10-4 |

| R2 |

0.5448 |

0.6205 |

| Pseudo-second-order |

qe, cal (mg/g) |

23.60 |

9.32 |

| k2 (g mg-1min-1) |

0.32 |

0.17 |

| R2 |

0.9999 |

0.9996 |

Table 6.

Isotherm parameters for RB5 adsorption on CKFC.

Table 6.

Isotherm parameters for RB5 adsorption on CKFC.

| Type of isotherm |

Parameters |

RKFC |

CKFC-Fe3O4 Composite |

| Langmuir |

qmax (mg/g) |

60.04 |

92.84 |

| KL (L/mg) |

0.0147 |

0.0283 |

| RL |

0.5748 |

0.4138 |

| R2 |

0.9996 |

0.9998 |

| Freundlich |

Kf |

2.37 |

4.45 |

| 1/n |

0.5864 |

0.5300 |

| R2

|

0.9167 |

0.9250 |

Table 7.

Comparison of the adsorption capacity of CKFC towards RB5 dyes with different ACs.

Table 7.

Comparison of the adsorption capacity of CKFC towards RB5 dyes with different ACs.

| Adsorbents |

Dye |

qmax (mg/g) |

References |

| Residue from the aluminum industry |

RB5 |

0.98 |

[8] |

| NaOH-treated activated sludge |

RB5 |

118.2 |

[2] |

| Beneficiated Kaolin |

BY 28 |

1.896 |

[50] |

| Natural untreated clay |

BY 28 |

76.92 |

[20] |

| KFC-Fe3O4 Composite |

RB5 |

92.84 |

This Study |

Table 8.

Thermodynamic parameter for RB5 dye adsorption on the KFC-Fe3O4 composite.

Table 8.

Thermodynamic parameter for RB5 dye adsorption on the KFC-Fe3O4 composite.

| Adsorbent |

Temp(K) |

KL

|

ΔGo(KJmol-1) |

ΔHo(KJmol-1) |

ΔSo(KJmol-1) |

R2

|

| KFC-Fe3O4Composite |

298 |

2.205 |

-1.95908 |

6.4524 |

28.2632 |

0.9942 |

| 308 |

2.429 |

-2.27258 |

| 328 |

2.804 |

-2.81166 |